Abstract

All-day monitoring of ozone and its precursors is crucial for understanding the chemical processes driving ozone pollution and improving urban air quality. Previously, the absence of cost-effective instruments with high temporal resolution, wide coverage, and fine spatial detail made comprehensive simultaneous observations of ozone and its precursors impossible, limiting our ability to study complex atmospheric chemical changes at night. Our study addresses this challenge by combining computed tomography and Differential optical absorption spectroscopy algorithms to achieve high-spatial-resolution, multi-constituent detection throughout the day. We tested multiple Light emitting diodes with varying wavelengths to enhance cost-effectiveness and incorporated high-precision tracking technology to enable accurate signal return from a drone-carried reflector array. Here, we show an affordable instrument that provides rapid response, precise spatial details, and extensive coverage for all-day detection of ozone and key precursors like formaldehyde and nitrogen dioxide, offering valuable insights into ozone pollution dynamics and aiding pollution source identification.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chemical and physical processes in the atmosphere contribute equally to air pollution, regardless of the time of day. Nighttime atmospheric inversion significantly impedes pollutant dispersion and removal1, exacerbating air pollution and enhancing nighttime chemical reactions in the troposphere, potentially affecting the air quality the following day2. Recent studies have indicated the growing contribution of nighttime chemical processes to air pollution in China3. Notably, nighttime reactions involving ozone and secondary organic aerosols play a critical role in shaping the air pollution levels on the following day2,3. Risks associated with daytime atmospheric photochemical reactions are increasingly recognized as common occurrences4,5,6. In particular, tropospheric ozone pollution is linked to cardiovascular diseases, premature deaths7,8, and reduced crop yields9,10, which can negatively affect society and the economy. It disrupts the ability of bees and other pollinators to locate and pollinate flowers11, leading to the collapse of terrestrial ecosystems12, which can also disrupt photosynthesis, diminish the capacity of terrestrial ecosystems to sequester atmospheric carbon, contribute to global warming13,14, and lead to extreme weather events and economic losses. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of daily physicochemical changes in polluted air is vital for enhancing air quality.

Ozone formation is a complex process that involves multiple precursors and weather conditions, and is closely tied to the quantities and ratios of volatile organic compounds and nitrogen oxides. To analyze the full-day physicochemical changes in tropospheric ozone pollution, instruments capable of observing ozone and its precursors with high temporal resolution over a broad area and at a low cost are required15. Currently, all-day atmospheric monitoring technology is primarily ground-based, including the tower- and balloon-based platforms. Although tower-mounted and atmospheric lidar systems partially address the lack of vertical monitoring16,17, they suffer from low timeliness18, limited multi-gas observation capabilities, and high costs19. This results in substantial limitations in the analysis of ozone precursors from a wide range of sources, including a wide variety of species with short lifespans. Satellite and airborne remote sensing offer extensive spatial coverage; however, they typically provide coarse resolutions and have notable limitations in terms of temporal resolution20,21. Furthermore, these instruments have a very limited capacity to monitor short-term emergencies, which further restricts real-time environmental assessments and the provision of actionable information to decision-makers22. Finally, despite their high accuracy, traditional point-based measurement methods often have a limited range, leading to an inadequate spatial representation of the results23. The instrument presented in this study utilizes hyperspectral remote sensing24,25 and precision optical path calibration technology from accurate visual tracking system26, so that the observation signal can be accurately returned from the reflector array carried by the drone one kilometer away, using the mobility of the drone, to overcome the problem of high spatial resolution and large-scale observation. It addresses the limitations of existing remote sensing technologies, such as the high cost and low efficiency associated with monitoring a limited number of species, and improves upon the spatial representation issues associated with point sampling methods. By integrating medical imaging27 with computer tomography, the instrument overcomes the challenges of limited measurement range and slow response times at high spatial resolutions. The multi-band Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) is selected and combined, to replacing traditional, costly light sources, such as xenon and deuterium lamps, thereby significantly reducing costs without compromising performance. Additionally, the instrument enables the simultaneous measurement of various ozone precursors, including different volatile organic compounds, through the wavelength coupling of LEDs with different central wavelengths, demonstrating robust flexibility. The result is a hyperspectral remote sensing instrument that offers an extensive observation range19, all-day coverage, high accuracy28, strong timeliness, high spatial resolution, flexibility, convenience, and low cost. Compared to similar instruments, this method overcomes the limitations of traditional multi-axis Differential Optical Absorption Spectroscopy (DOAS), which are restricted to daytime observations, and LP-DOAS, which can only measure components along fixed optical paths29. The instrument exhibits high sensitivity to spatial gradients in pollutant concentrations, and its measurements provide superior spatial detail compared with that of chemical models and airborne and satellite platforms.

Here, we show an instrument that achieves comprehensive horizontal distribution detection of trace components, such as O3, active nitrogen, and volatile organic compounds, offering insights into ozone pollution mechanisms and facilitating precise pollution source identification. The instrument also enhances nighttime observation capabilities, contributing to the advancement of China’s comprehensive atmospheric remote sensing monitoring system and supporting the strategic initiatives of “Beautiful China” and “Reduction of Pollution and Carbon Emissions” with robust scientific and technological backing.

Results

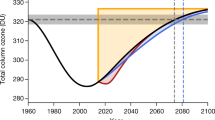

The development of the Atmospheric Pollutants Hyperspectral Computational Tomography Imaging System (AHCTIS) faced several technical hurdles: (1) the need for high-power, selectable-wavelength light sources that maintain stable waveforms; (2) the requirement for the ground-based light source to accurately track the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle(UAV)’s angular reflector array in real-time and reliably reflect spectral signals back to the ground station; (3) the necessity for high-precision reconstruction of the horizontal distribution of trace gases; (4) the challenge of detecting low concentrations of tropospheric ozone and its precursors, which are further complicated by cross-absorption interference, such as BrO, CS2, SO2, and OCIO (as shown in Figs. 1b1).

a is a schematic diagram of the optical part of the instrument. Light from LEDs of varying wavelengths is initially emitted and subsequently coupled into a Y-type fiber following fiber welding. The light exits the Y-type fiber and is directed into a Newtonian reflecting telescope. The light is ultimately channeled into a spectrometer for analysis. In the figure, (A), (B), and (C) illustrate the end face connections between the fiber and its coupling; b1 describes the absorption cross sections of some gases that may be encountered in the detection. b2 shows a spectral representation of the coupling processes for multiple LEDs, with the curves (A), (B), and (C) corresponding to the spectral data from the optical fiber end faces illustrated in (A), (B), and (C) of Fig. 1a.

Instrumentation

By utilizing LED light sources with various central wavelengths tailored to the characteristic absorption bands of the target gases, our system enhances the detection capabilities beyond those of traditional instruments that rely on deuterium or xenon lamps. The spectral shape of these conventional light sources results in poor signal-to-noise ratios, which limits the performance of gas detection at specific bands.

In this study, we employed a fused-fiber technique to couple multiple wavelengths from LEDs. We selected fibers of appropriate diameters based on specific detection needs, preventing insufficient signal-to-noise ratios in certain bands owing to power disparities among LEDs and avoiding detector saturation in others. The core diameters of the incident and exit ends of our fused fiber, as depicted in Fig. 1, are 600 um and 1000 um, respectively. Given the typical 15 nm crest width of a single LED, we matched the light source to the absorption cross-sections of various detection components to optimize performance. To detect O3, NO2, and HCHO simultaneously, whose effective detection bands are 300–320, 350–400, and 300–360 nm, respectively, we chose four LEDs with central wavelengths of 310, 325, 340, and 365 nm. As illustrated in Fig. 1a), the coupling process involves four fiber cores corresponding to the selected LEDs, a single large-diameter fiber that evenly combines the emitted light, and a fiber end with six cores to ensure sufficient optical power at the output (The physical diagram see Supplementary Fig. 17). This configuration ensured that the spectrometer could detect spectral signals with an adequate signal-to-noise ratio. The captured spectral signal is transmitted to the spectrometer via a yellow core, as shown in Fig. 1a). The outgoing and reflected light from the angular reflector arrays (For specific dimensions, see Supplementary Fig. 15), depicted in purple in Fig. 1a), completes the optical path. An illustrative example of the system’s measured signal, along with the corresponding concentration calculation methodology, is provided in Supplementary Methods. 4. We retrieve ozone over 302–318 nm, nitrogen dioxide over 368–383 nm, and formaldehyde over 331–348 nm. The species included in the model were chosen primarily on the basis of those known to be emitted in the target scene, supplemented by additional cross-sections of gases commonly present in the atmosphere. We can use the same inversion configuration to calculate multiple gases, but there is no guarantee that the results will be optimal for each gas. Detailed retrieval configurations are provided in the Supplementary Table 7-10.

To facilitate extensive, multi-component, and continuous observations, the AHCTIS system was equipped with both aerial and ground components, as detailed in the Supplementary Fig. 1. The UAV component of the AHCTIS is equipped with an angular reflector array. The design enables the ground instrument to receive spectral signals carrying the concentration information of various pollutants, as illustrated in Fig. 2 (For measurement details, see supplementary Methods. 4). During operation, the AHCTIS UAV followed a predetermined flight path, with the ground station adjusting its orientation to track the movement of the UAV. This process allows real-time signal return, enabling the calculation of the pollutant gas column concentration between the UAV and ground station. The splitter in Fig. 2a is pivotal for maintaining the stability of the observation system, ensuring that mechanical movement during tracking does not compromise the calibration. Further details of the tracking principles are provided in the Methods section.

The instrument calculates the directional difference from the UAV using its onboard GPS, providing a coarse tracking signal (The physical diagram see Supplementary Fig. 10). a is a schematic diagram of the principle of the precisely aligned optical path. Fine adjustments are made using a dichroic beamsplitter to align the tracking and gas detection optical paths on the same axis (See Supplementary Methods.7). If the UAV deviates from the center of the instrument’s view, a control algorithm adjusts a two-dimensional rotating platform to realign it, ensuring continuous acquisition of spectral data that includes the absorption characteristics of the target gases. Ultimately, the concentration data of the target gases are derived and analyzed at the control terminal, providing detailed insights into the gas composition. b is an enlarged view of the internal details of AHCTIS.

Instrument accuracy verification

To verify the accuracy and stability of AHCTIS, we selected two accurate calibration and verification methods. First, the sensitivity and accuracy of the instrument were verified using a laboratory calibration method of a satellite sensor to observe pollution gases with known concentrations (See Supplementary Methods.5). In this study, two gases, NO2 and HCHO, with known gradient concentrations were measured, and the observed values were in good agreement with the real values (a1 and a2 in Fig. 3). The average values of the measurement errors in the three concentration observation experiments of NO2 and HCHO were 4.99% and 4.92%, respectively. This included the error of the gas distribution instrument (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for specific parameters) in the output gas ratio. We then verified the long-term stability and accuracy of AHCTIS. The AHCTIS was set up in the University of Science and Technology of China (see Supplementary Fig. 3 for the specific position), and the length of the observation optical path was approximately 800 m. The observed atmospheric components were NO2 and O3. The NO2 concentration measured by the AHCTIS was compared with the measurement results of ICAD, a point-type nitrogen oxide measuring instrument (see Supplementary Fig. 4 for specific parameters). The results showed that the NO2 concentration observed by the AHCTIS was consistent with the time variation trend of the NO2 concentration observed by the ICAD. The maximum values of AHCTIS and ICAD during the observation period were 30.74 μg/m3 and 29.54 μg/m3 respectively, and the standard deviation was 2.16 μg/m3. The coefficient of determination was 0.945 (Fig. 3b1–b2). The O3 concentration measured by the instrument was consistent with the time variation trend of the O3 measurement results of Thermo, a point ozone-measuring instrument (see Supplementary Fig. 5 for specific parameters). The mean absolute deviation is 9.29 μg/m3, and the correlation can reach 0.863 (Fig. 3c1–c2). There are two possible reasons for this this large deviation. First is the Thermo instrument for ozone observation came from the CNEMC site (location in Supplementary Fig. 3), which is approximately 2 km from the AHCTIS observation site. The second reason may be that ozone will invade from the stratosphere to the troposphere30, which means that the vertical distribution of ozone will be different, and during our observation period, in addition to the horizontal space distance, the height is also different, the height of the CNEMC is about the height of the five-story building, and the position of our instrument observation point is at the height of the 13th floor. The instruments of the CNEMC are unable to capture the ozone concentration at higher spatial locations, so the observation data will produce a certain bias. (The observation locations are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, and the validation data is presented in Supplementary Fig. 12). The main reason for the lack of long-term observations and comparisons of HCHO in this study was the lack of long-term monitoring data of HCHO using point-based instruments. The measurement method for the instrument’s detection limit is shown in Supplementary Methods.1. The detection limits of AHCTIS for O3, HCHO, and NO2 (at a 5 km optical path) were 1.61 μg (0.8 ppbv), 1.72 μg (1.3 ppbv), and 0.33 μg (0.2 ppbv), respectively.

a1, a2 are the standard gas verification results of NO2 and HCHO, respectively. We established three distinct concentration levels for HCHO and NO2 using a gas blending device, achieving observed values that closely matched the intended levels. Figures (b1) and (b2) compare and correlate the long-term NO2 observation data between the AHCTIS and iterative cavity-enhanced DOAS (ICAD) systems, both positioned at the same monitoring site. Figures (c1) and (c2) present a similar analysis for O3, comparing long-term observation data between the AHCTIS and Thermo instruments. The O3 data for Thermo were obtained from the China National Environmental Monitoring Centre (CNEMC) monitoring station, situated less than 2 km from the AHCTIS instrument in a direct line. The information of the instruments used in the verification experiment is shown in the Supplementary Table 2-6.

Results of various field observation modes

As shown in Fig. 4, the AHCTIS has the following three observation functions: 1. Fast sector scanning, used to quickly determine the high-concentration orientation of O3 and its precursors. 2. Rapid imaging of the emission source pollutant plume for imaging emission plume concentration, quantification of emission flux, and assessment of the diffusion trend of O3 precursors. 3. Horizontal Computed Tomography (CT) imaging observations of O3 and its precursors with high spatial resolution used to determine the high-value area of O3 and its precursors and locate the pollution outlet. The spatial resolution of observation is better than 40 m × 40 m (See Supplementary Methods.6). To test the performance of the instrument under the aforementioned observation modes: In fast-sector scanning mode, the observation point of the ground remote sensing instrument and the flight path of the UAV are shown in Figs. 4a1, and the scanning results are shown in Figs. 4a2. NO2 with an average concentration of more than 36.0 μg/m3 and 27.2 μg/m3 are observed in the directions of true north and east by north, respectively, corresponding to the emission directions of the sewage treatment plant and the waste incineration plant. The flight path of the UAV in fast imaging mode of the emission-source pollutant plume is shown in Figs. 4b1, and the imaging results are shown in Figs. 4b2. The highest concentration of the NO2 in the observed plume is 29.0 μg/m3, and the emission flux of NO2 during the observation period is approximately 27.1 ± 16.4 kg/h. Plumes are potential sources of pollution that affect urban air quality. The flight path of the UAV and the position of the ground remote sensing instrument in the high spatial resolution horizontal CT imaging observation mode are shown in Figs. 4c1, and the observation results are shown in Figs. 4c2. The highest NO2 concentration in the industrial park is 137.0 μg/m3, which is consistent with the thermal power plant outlet31, and the emission source is accurately located.

a1 is the UAV adopts an arc flight scheme. The ground-based remote sensing instrument and the UAV perform multi-directional scans to identify the position of and the spread from significant emission sources. The UAV’s trajectory is marked by a yellow arrow, with potential emission sources indicated by white boxes. a2 is the corresponding observation result. It can be seen that the azimuth of the high pollution value matches the azimuth of the pollution source. b1 The UAV follows a meandering path at the emission outlet, collecting spectral data in conjunction with the ground-based remote sensing instrument. The yellow arrow denotes the UAV’s flight route, with the outlet’s location marked by a white box. b2 is the observation result under the observation mode of (b1), the imaging reveals a distinct NO2 emission plume. c1 A single UAV navigates the industrial park’s perimeter, with the AHCTIS positioned at points A and B to collect spectral data successively, enabling precise horizontal monitoring to pinpoint the emission source. The yellow arrow signifies the UAV’s flight path, with potential emission sources highlighted by white boxes. c2 is the observation result under the observation mode of (c1), the horizontal distribution observations of NO2 within the industrial park successfully identify the location of NO2 emissions.

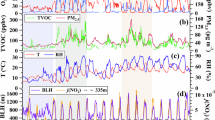

All-day horizontal CT imaging results

To establish the day and night monitoring capabilities of the AHCTIS for ozone and its precursors, we performed all-day observations of NO2, HCHO, and O3 near the facility, as depicted in Fig. 4c1. Figure 5 panels (a1), (b1), and (c1) present the horizontal distribution data for O3, NO2, and HCHO, respectively, captured at 3 PM on March 7, 2024. Similarly, Fig. 5a2, b2, and c2 display the distribution data for the same pollutants at 8 PM on March 8, 2024. The observations were made under calm and stable weather conditions. The target industrial area includes thermal power plants to the south and west and a chemical plant to the east. Our findings indicate that concentrations of O3, NO2, and HCHO near the chemical plant remained relatively stable over the diurnal period, peaking at 96.1, 147.2, and 29.1 μg/m3, respectively. In proximity to the thermal power plant, the concentrations of O3, NO2, and HCHO were lower during the day and higher at night. The peak concentrations of O3, NO2, and HCHO observed during daytime and nighttime were 84.6 and 99.0 μg/m³, 133.3 and 146.2 μg/m³, and 27.1 and 29.5 μg/m³, respectively. This discrepancy is likely attributable to the nocturnal peak in urban electricity demand, which subsequently leads to an increased operational load for thermal power plants during nighttime hours31. The diurnal measurement data facilitated the precise identification of NO2 and HCHO emission sources. This information is instrumental for regulatory authorities in pinpointing instances of corporate over-emissions and clandestine nocturnal discharges, thereby enabling the targeted enforcement of pollution control measures.

The observation range of Fig. 5 is the same as that of Fig. 4 (c1), for AHCTIS, the signal-to-noise ratio is similar during the day and night. Panels (a1), (b1), and (c1) of Fig. 5 display the horizontal distribution of O3, NO2, and HCHO observed at 3 PM on March 7, 2024. Panels (a2), (b2), and (c2) illustrate the horizontal distribution of O3, NO2, and HCHO observed at 8 PM on March 8, 2024. Potential pollution sources are indicated by white text annotations.

Comparative verification of pollution levels based on mobile vehicle observation

To ascertain the precision of the spatial distribution of the pollutant concentrations, we employed mobile vehicle observations in conjunction with synchronous navigational surveys within the area depicted in Fig. 6a. The comparison and verification processes were conducted under consistently clear and stable weather conditions. For details on the data processing methodology for mobile vehicle observations, a reference is provided in Supplementary Methods.2, which outlines the techniques for mobile DOAS. Figure 6b–d show the horizontal imaging and navigation observation results for O3, NO2, and HCHO, respectively. These findings indicate a strong concordance between the horizontal imaging and navigation observation results. The coefficient of determination for the spatial distributions of O3, NO2, and HCHO derived from both observational methods were 0.76, 0.76, and 0.70, respectively. This confirmed the reliability of the horizontal imaging of the AHCTIS system for spatial distribution analysis to a significant degree.

a shows the position of the instrument during the comparison experiment. b, c, and d illustrate the concentration distributions of O3, NO2, and HCHO, respectively, with crosses indicating the pollutant concentration values measured by mobile observation vehicles. e1, e2, and e3 are the comparison and verification of the observation results of NO2, O3 and HCHO by ACHTIC and the observation results of the mobile DOAS, respectively.

Discussion

Uncertainty in CT imaging of contaminated gas levels

We analyzed the uncertainties in the imaging results, focusing on their relation with the actual detection optical path. Consistent column concentration results do not guarantee identical spatial distribution outcomes owing to variations in the optical path. To ensure the optical path accuracy, we used a high-precision GPS module for accuracy verification. The GPS module was tested by navigating a defined area measuring 105 m in length and 60 m in width. The resulting data and measured error distributions are shown in Fig. 7a1 and 7a2, respectively. The deviations were predominantly under 0.20 m, with a maximum of less than 0.40 m. The optical path error is thus controllable at the decimeter scale, resulting in a final measurement error ratio of approximately 0.1% relative to an optical path spanning hundreds of meters, rendering the impact on the calculation results negligible, not to mention in the actual measurement, the optical path at the kilometer level.

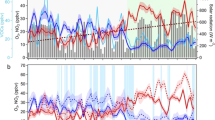

a1 shows the comparison between the trajectory recorded by high-precision GPS and the actual trajectory. a2 depicts the deviation distribution between the trajectory recorded by high-precision GPS flight and the actual trajectory, and the error is in the order of decimeters. b1 illustrates the time sequence diagram of the deviation from the center of the field observed by the instrument during the tracking process, and the deviation must be ±0.1° to ensure the normal operation of the instrument. b2 displays the temperature control effect, showing that the light source temperature is controlled within the range of ±0.1°C fluctuation. c1 refers to the wavelength drift caused by the change of the light source with the change of temperature. c2, c3, and c4 show the influence of different degrees of deviation between the actual temperature of the light source and the set temperature (25°C) on the fitting effect of spectral analysis. Using NO2 as an example, it can be seen that the greater the temperature deviation, the worse the fitting effect. d1 and d2 present a similar analysis for NO2 between the AHCTIS and Thermo instruments, comparison of NO2 observation data over a 40-h period, including moderate rain and light fog. The NO2 data for Thermo were obtained from the CNEMC monitoring station, situated less than 2 km from the AHCTIS instrument in a direct line. e1, e2 present a similar analysis for O3 between the AHCTIS and Thermo instruments, comparison of O3 observation data over a 40-h period, including moderate rain and light fog. The O3 data for Thermo were obtained from the CNEMC monitoring station, situated less than 2 km from the AHCTIS instrument in a direct line.

Instrument performance index evaluation

First, we addressed the uncertainties associated with the observational outcomes of the instrument. Evidence from Fig. 3a1 and 3(a2) indicates that the accuracy of the concentrations was better than 10%, which confirms the instrument’s reliability. Two primary factors contribute to instrument uncertainty: the temperature stability of the light source and the choice of spectral fitting band. The stability of the light source is shown in Fig. 7c1. Temperature variations exceeding 5 °C visibly altered the light source spectrum’s crest and shape. The nonlinear relation between this change and temperature is depicted in Fig. 7c2–c4, potentially amplifying the inversion fitting errors, with extreme cases showing errors of an order of magnitude greater than the measurements. Constant temperature control was implemented in this study to maintain the light source stability throughout the observations. The temperature fluctuations were managed using a closed-loop semiconductor cooling system and a Negative Temperature Coefficient (NTC) thermistor. Figure 7b2 demonstrates that operating the light source at 25.0 ± 0.1°C is crucial for minimizing spectral inversion uncertainties arising from temperature variations. The selection of the spectral fitting band must be carefully aligned with the gas absorption peak and the light source’s intensity peak to ensure a robust signal-to-noise ratio and minimal fitting residuals. For a detailed analysis of the impact of residual size on the reliability of the results, refer to Supplementary Methods.3. The stability of the LEDs’ spectrum over time see Supplementary Fig. 9. Based on the 40-h observation under rainy weather in Fig. 7e1 and the ozone observation data in Fig. 3c1, we speculate that a higher water vapor content in the air will promote the formation of ozone. Meanwhile, ozone invasion in the stratosphere will further increase the surface ozone level, thereby exacerbating ozone pollution during the observation period.

Limitations of instrument use

Because the instrument in this paper is an optical remote sensing instrument, the signal-to-noise ratio of the measured signal will directly affect the performance of the instrument, and even determine whether the instrument can be used normally. In practical use, the environmental condition that will affect the signal-to-noise ratio is the atmospheric visibility. We conducted a 40-h observation experiment with moderate rain and light fog. The observation results show that the instrument can work properly when the atmospheric visibility is more than twice the distance from the instrument to the reflector array. Compared with the O3 and NO2 observed at nearby CNEMC, it was found that the trend of concentration change was consistent, and the coefficient of determination was 0.773 and 0.748 (in Fig. 7d2 and e2), respectively, which did not decrease compared with the sunny observation period. When the atmospheric visibility is lower than the distance from the instrument to the reflector array, the instrument will not receive light from the reflector and will not work properly. Therefore, from the perspective of engineering application, we suggest that the instrument should be used when the atmospheric visibility is higher than twice the distance from the instrument to the mirror array.

Analysis of instrument cost-effectiveness

We will evaluate the instrument comprehensively from three aspects: economic cost, observation time cost, and observation range. This instrument is suitable for detecting the horizontal distribution of pollutants and precise source tracking in a regional range, filling the scale gap between satellites and ground monitoring.

Currently, there are three methods for tracing the horizontal distribution of pollutants: 1. Satellite remote sensing, 2. Vehicle-mounted mobile sampling observation, and 3. Using drones to carry small sampling instruments for observation.

First, comparing AHCTIS with satellite remote sensing. Taking TROPOMI as an example, it is carried on the Sentinel-5 Precursor satellite. The official estimates only specify the total cost of Sentinel-5 Precursor as about 720 million euros, without detailing the specific cost of TROPOMI. Typically, scientific instruments account for 30–50% of the total satellite cost, suggesting TROPOMI’s cost is around 240 million euros. In contrast, AHCTIS costs only 30,000 euros. Regarding time cost, TROPOMI can only observe during daylight, while our instrument operates continuously throughout the day.

Next, comparing AHCTIS with vehicle-mounted mobile sampling observation. Mobile sampling observation typically uses mass spectrometers, with the most common models priced at approximately 800,000 euros. While they can operate round-the-clock, they are restricted to following road networks, providing concentration distributions only along roads. If high values are detected on a route, pinpointing the exact emission source remains impossible.

Finally, comparing AHCTIS with drone-based sampling. Drones face payload limitations, restricting them to low-accuracy sensors which are easily affected by the airflow generated by the UAV’s propellers. Additionally, UAVs have limited flight range due to battery constraints. For example, to achieve the two-dimensional horizontal distribution of pollutants demonstrated in this paper, a drone carrying point-type sensors would require at least 14 kilometers of flight distance. Current civilian UAV systems struggle to meet this requirement.

Methods

The AHCTIS measurement principle is as follows:

In the formula, \({I}_{0}(\lambda )\) is the light intensity before passing through the medium, \(I(\lambda,L)\) is the light intensity after passing through the medium, \(\lambda\) is the wavelength, \(L\) is the path length of the light through the medium, which is twice the distance between the light source and the angular mirror, \({\sigma }_{{{{\rm{j}}}}}(\lambda,p,T)\) is the absorption cross section of polluted gas related to wavelength, pressure and temperature, \(j\) is the number index of pollution gas components in the medium, \({\varepsilon }_{R}(\lambda )\) is the influence of Rayleigh scattering on light, \({\varepsilon }_{M}(\lambda )\) is the influence of Mie scattering on light, \(A(\lambda )\) is the combined effect of the instrument’s characteristics and solar radiation (direct and scattered) during the daytime, used here as a correction factor. In actual observation, the instrument only needs to measure \(I(\lambda,L)\) and \({I}_{0}(\lambda )\) 32.

According to this principle, various fixed-point observation instruments have been invented. The advantages of AHCTIS in this study are mainly reflected in that it can detect ozone and its precursors (HCHO, NO2) in stereo at the same time throughout the entire period, has high timeliness (0.5 h), high spatial resolution (≤40 m×40 m), and a large observation range.

AHCTIS high precision and stable tracking observation method

To enhance the precision of ground-based remote sensing for tracking UAV-mounted angular reflector arrays, dichroic splitters, and high-resolution cameras were employed. The two-dimensional rotating platform was equipped with a high-precision equatorial instrument, the details of which are provided in Supplementary Table 1. This design ensures accurate UAV tracking while mitigating the potential system instability that could arise from improper parameter settings in the two-stage tracking mechanism (See Supplementary Methods. 7).

To ensure operational stability and swift response in the ground-based remote sensing of UAVs, this study positioned the receiving and transmitting ends of the optical fiber at slightly defocused locations33 and employed a PID visual tracking algorithm:

In the formula, \({y}_{d}(x)\) is the position of the UAV in the field of view at the current moment, \({y}_{d}^{{\prime} }(x)\) is the speed of the UAV in the field of view at the current moment, \(y(x)\) is the position of the UAV in the system at the last moment, and \(y^{\prime}(x)\) is the speed of the UAV in the field of view at the last moment. \(e(x)\) is the deviation between the current and expected positions, \(e^{\prime}(x)\) is the rate of change of the UAV’s moving speed in the field of view, and \(F(x)\) is an intermediate quantity fed back to the two-dimensional rotating platform control speed. \(B\) is the speed that is finally fed back to the two-dimensional rotating platform, \({K}_{p}\), \({K}_{i}\), \({K}_{d}\), \(a\), and \(b\) are all parameters adjusted according to the system state. The previous section introduces only the control algorithm process of one dimension; the control algorithm of the second dimension is the same. After setting the parameters reasonably, the Proportion Integration Differentiation (PID) visual tracking algorithm not only ensures the stability of the system but also achieves a rapid response to ensure the timeliness of instrument observation. The tracking effect is shown in Fig. 7b. As long as the angle deviation is within ±0.01°, the tracking accuracy of the AHCTIS UAV end can be achieved.

Atmospheric horizontal CT remote sensing reconstruction theory

This approach successfully adapts medical CT scanning algorithms for atmospheric monitoring. During the AHCTIS observations, the UAV was not required to traverse the industrial park, as shown in Fig. 4c1. This scheme can not only fundamentally avoid accidents caused by drones crashing into the factory but also achieve horizontal grid image formation with high spatial resolution to achieve accurate traceability of pollutant emission sources. The schematic diagram of the CT algorithm is shown in Fig. 8.

It is a schematic diagram of atmospheric CT remote sensing reconstruction theory: The ground-based remote sensing instruments positioned at points \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) must consistently target the UAV’s moving angular reflector array. The UAV does not need to fly over the measured area, but only needs to fly around the measured area to obtain the distribution results of pollutant concentration levels in the measured area. The blue arrow in the diagram indicates the UAV’s flight trajectory.

\({P}_{\alpha K}\) is the column concentration on the \(K-th\) observation light path of the observation point \(\alpha\), and \({P}_{\alpha K}=T\cdot {\sum }_{y=0}^{n}{\sum }_{x=0}^{m}{L}_{K(x,y)}\cdot {C}_{\alpha K(x,y)}\). \({P}_{\beta J}\) is the column concentration of the \(J-th\) observation at observation point \(\beta\), \({P}_{\beta J}=T\cdot {\sum }_{y=0}^{n}{\sum }_{x=0}^{m}{L}_{J(x,y)}\cdot {C}_{\beta J(x,y)}\), where \(T\) is the conversion factor from column concentration to absolute concentration, \({L}_{K(x,y)}\) represents the length of the \(K-th\) observation light path of the \(\alpha\) observation point when it passes through the grid point \((x,y)\), similarly to the definition of \({L}_{J(x,y)}\); \({C}_{\alpha K(x,y)}\) is the volume concentration of pollutant gas within the line segment, similarly to the definition of \({C}_{\beta J(x,y)}\). The true volume concentration in the range of lattice points \((x,y)\) is defined here as \(S(x,y)\), assuming that the concentration in the range of lattice sites is diffusively uniform.

It follows that the observed column concentration is proportional to \(S(x,y)\)\(.\) There is a mapping relation between them, and the optimal estimation algorithm can be used to obtain

\(D\) is a differential operator, for example \(DS\) take the first-order or second-order derivative of the two-dimensional function \(S(x,y)\) to filter out some strange values, and \(\gamma\) is a weighting factor that primarily limits the severity of the change in concentration in space. For example, near a high concentration emission point, in a relatively stable state, it is unlikely that a concentration of 0 will occur in the range of tens of meters.

To quantify the interaction between each grid point and its surrounding grid points, we assumed that the pollutants detected at the grid points conformed to the Gaussian diffusion model under statically stable weather conditions34. Theoretically, the grid can be subdivided indefinitely; however, considering the influence of the AHCTIS data acquisition rate and UAV endurance time, the size of the grid in this study was approximately 40 m x 40 m, and the observation range was 800 m x 680 m.

Data availability

The main manuscript and supplementary materials data that support the findings of this study are available in zenodo with the link(https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17155624). Source Data is available as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The main manuscript and supplementary materials code that support the findings of this study are available in zenodo with the link (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17155624).

References

Anonymous. Night-time clues to pollution. Nature Geoscience 16, 193–193 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-023-01157-8 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Increased night-time oxidation over China despite widespread decrease across the globe. Nat. Geosci. 16, 217–223 (2023).

Pan, R. et al. Investigation into the nocturnal ozone in a typical industrial city in North China Plain, China. Environ.Pollut. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2024.124627 (2024).

Xue, L. et al. Oxidative capacity and radical chemistry in the polluted atmosphere of Hong Kong and Pearl River Delta region: analysis of a severe photochemical smog episode. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 9891–9903. (2016).

Liu, Z. et al. Summertime photochemistry during CAREBeijing-2007: ROx budgets and O3 formation. Atmos Chem Phys 12, 7737–7752 (2012).

Pinto, D. M., Blande, J. D., Souza, S. R., Nerg, A. M. & Holopainen, J. K. Plant volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in ozone (O3) polluted atmospheres: the ecological effects. J. Chem. Ecol. 36, 22–34 (2010).

Silva, R. A. et al. Future global mortality from changes in air pollution attributable to climate change (vol 7, pg 647, 2017). Nat. Clim. Change 7, 845–845 (2017).

Liu, S. et al. Long-term exposure to ozone and cardiovascular mortality in a large Chinese cohort. Environ. Int 165, 107280 (2022).

Tai, A. P. K., Martin, M. V. & Heald, C. L. Threat to future global food security from climate change and ozone air pollution. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 817–821 (2014).

He, L. et al. Marked impacts of pollution mitigation on crop yields in China. Earth’s Future https://doi.org/10.1029/2022ef002936 (2022).

Pennisi, E. At night, pollution keeps pollinating insects from smelling the flowers. Science 383, 578 (2024).

Goumenaki, E., Gonzalez-Fernandez, I. & Barnes, J. D. Ozone uptake at night is more damaging to plants than equivalent day-time flux. Planta 253, 75 (2021).

Sitch, S., Cox, P. M., Collins, W. J. & Huntingford, C. Indirect radiative forcing of climate change through ozone effects on the land-carbon sink. Nature 448, 791–794 (2007).

Ainsworth, E. A., Yendrek, C. R., Sitch, S., Collins, W. J. & Emberson, L. D. The effects of tropospheric ozone on net primary productivity and implications for climate change. Annu Rev. Plant Biol. 63, 637–661 (2012).

Sun, Y. et al. Atmospheric environment monitoring technology and equipment in China: a review and outlook. J. Environ. Sci. (China) 123, 41–53 (2023).

Chen, B. et al. Origin of non-spherical particles in the boundary layer over Beijing, China: based on balloon-borne observations. Environ. Geochem Health 37, 791–800 (2015).

Tevlin, A. G. et al. Tall tower vertical profiles and diurnal trends of ammonia in the Colorado front range. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017jd026534 (2017).

Graham, B. et al. Organic compounds present in the natural Amazonian aerosol: characterization by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. https://doi.org/10.1029/2003jd003990 (2003).

Reshi, A. R., Pichuka, S. & Tripathi, A. Applications of Sentinel-5P TROPOMI Satellite Sensor: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 24, 20312–20321 (2024).

Acharya, B. S. et al. Unmanned aerial vehicles in hydrology and water management: applications, challenges, and perspectives. Water Resour. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021wr029925 (2021).

Tack, F. et al. Intercomparison of four airborne imaging DOAS systems for tropospheric NO2 mapping – the AROMAPEX campaign. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 12, 211–236 (2019).

Yang, J. et al. The role of satellite remote sensing in climate change studies. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 875–883 (2013).

Nasse, J.-M. et al. Recent improvements of long-path DOAS measurements: impact on accuracy and stability of short-term and automated long-term observations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 12, 4149–4169 (2019).

Lee, J. S., Kim, Y. J., Kuk, B., Geyer, A. & Platt, U. Simultaneous measurements of atmospheric pollutants and visibility with a Long-Path DOAS system in urban areas. Environ. Monit. Assess. 104, 281–293 (2005).

Lin, J. et al. Hyperspectral imaging technique supports dynamic emission inventory of coal-fired power plants in China. Sci. Bull. (Beijing) 68, 1248–1251 (2023).

Liu, H. Y. et al. Optical-Relayed Entanglement Distribution Using Drones as Mobile Nodes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 020503 (2021).

Gemmeke, H. & Ruiter, N. V. 3D ultrasound computer tomography for medical imaging. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Section A 580, 1057–1065 (2007).

Lee, B. H. et al. An iodide-adduct high-resolution time-of-flight chemical-ionization mass spectrometer: application to atmospheric inorganic and organic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 6309–6317 (2014).

Gao, S. et al. Study on the measurement of isoprene by differential optical absorption spectroscopy. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 14, 2649–2657 (2021).

Zhu F et al. The impact of stratosphere-to-troposphere transport associated with the Northeast China cold vortex on surface ozone concentrations in Eastern China, J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. https://doi.org/10.1175/JAMC-D-24-0027.1 (2024).

Sigauke, C., Verster, A. & Chikobvu, D. Extreme daily increases in peak electricity demand: Tail-quantile estimation. Energy Policy 53, 90–96 (2013).

Lee, J., Kim, K. H., Kim, Y. J. & Lee, J. Application of a long-path differential optical absorption spectrometer (LP-DOAS) on the measurements of NO2, SO2, O3, and HNO2 in Gwangju, Korea. J. Environ. Manag. 86, 750–759 (2008).

Merten, A., Tschritter, J. & Platt, U. Design of differential optical absorption spectroscopy long-path telescopes based on fiber optics. Appl Opt. 50, 738–754 (2011).

Deolmi, G. & Marcuzzi, F. A parabolic inverse convection–diffusion–reaction problem solved using space–time localization and adaptivity. Appl. Math. Comput. 219, 8435–8454 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42225504), the President’s Foundation of Hefei Institutes of Physical Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences (YZJJQY202401, BJPY2024B09).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WM wrote and completed the manuscript and participated in all the experimental work described in the paper. CX and CL provided ideas for the experiments and offered detailed guidance on the paper. WW participated in most of the experiments described in the paper and assisted in obtaining a large amount of data from instrument observations. QZ, ZW, and YY participated in the experiments for data comparison and validation and assisted in obtaining the data for comparison and verification.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Hiroaki Kuze and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, W., Xing, C., Wang, W. et al. Ozone pollution monitoring using a full-time hyperspectral tomography system for multiple air pollutants. Nat Commun 17, 245 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66944-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66944-w