Abstract

Ethylene-based crystalline copolymers are important materials across broad applications. However, precise control over their primary structures remains a critical challenge in advancing functional materials, limited by the intrinsic reactivity difference between ethylene and comonomers. In this work, we report the development of a light-driven organocatalyzed reversible-deactivation radical copolymerization to access well-defined ethylene-chlorotrifluoroethylene copolymer (ECTFE) under mild conditions (<5 atm, 25 °C). The rational design of a three-armed phenothiazine catalyst in combination with a fluorinated dithiocarbamate furnishes good chain-growth control in the photoredox-mediated copolymerization, yielding ECTFE of excellent alternating sequence with minimized chain defects, which resulted in high crystallinity and superior melting points (up to 263.8 °C). Importantly, the obtained ECTFE exhibits outstanding chain-end activity/fidelity, enabling chain-extension (co)polymerization to access a variety of unprecedented ECTFE-based block copolymers upon visible-light exposure, which has successfully integrated rigid and soft blocks in single chains. The ease of synthesizing such block copolymers creates a versatile and convenient platform to largely tune mechanical properties, affording polymeric materials spanning from thermoplastics to elastomers via structural tailoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reversible-deactivation radical polymerizations (RDRPs) are powerful tools to synthesize polymers of tailored chain length, various functional groups, and well-defined sequences1. Ethylene, as the cornerstone monomer in polymer industries, remains central in the development of high-performance materials. Copolymerization of ethylene can not only retain the essential crystalline property of polyethylene (PE) but also integrate the versatile functionalities of comonomers2,3. Despite the promise, RDRP of ethylene and comonomers remains challenging due to the fundamental difference in their reactivities. Among RDRPs, cobalt-mediated radical polymerization (CMRP)4, iodine transfer polymerization (ITP)5, and reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization6 present attractive avenues to tailor ethylene copolymers, with a comonomer scope encompassing vinyl esters, vinyl amides, acrylonitrile, carbon monoxide, and others. However, the copolymerizations of ethylene and polar comonomers disrupt crystalline domains of polyethylene7, which could decline crystallinity or cause amorphous behavior that compromises mechanical behavior. Furthermore, while polyolefin-polar block copolymers that covalently link rigid and soft chains are of great interest in largely modulating properties of thermoplastics and elastomers8,9, preparation of block sequences from ethylene copolymers-based macroinitiators via RDRPs has afforded blocks with limited rigid/soft chain difference4,5,6,10,11,12, with the incorporation of similar functional groups (e.g., esters). Amorphous polymers (e.g., polymethyl methacrylate) have been examined as macro-initiators in chain-extension polymerization of ethylene via RAFT process13. Until now, combinations of different polymerizations, such as coordination-insertion polymerization and radical polymerization, have been demanded to merge compositionally varied blocks in ethylene copolymers14,15,16,17,18; no unified strategy could enable both the controlled radical copolymerization of ethylene and chain-extensions copolymerization to distinct blocks (e.g., fluoroalkene and vinyl ether) via a single method.

Ethylene-fluoroalkene copolymerizations could provide copolymers of strong crystallinity and high melting point with the incorporation of fluorocarbon characteristics19, as demonstrated by a variety of commercial products, such as ethylene-chlorotrifluoroethylene copolymer (ECTFE, Halar®) and ethylene-tetrafluoroethylene copolymer (ETFE, Tefzel®), which offer crucial applications in scenarios necessitating exceptional resistance to harsh environments (e.g., ozone, chlorine, pH = 1-14), low permeability, and outstanding thermal stability20,21,22. However, free radical copolymerization of ethylene and fluoroalkene, the conventional synthetic approach, demands high pressures (e.g., 30-1000 atm) at elevated temperatures (e.g., 70-300 °C), resulting in poorly controlled chain length and chemical structure23,24. Moreover, the ethylene-fluoroalkene copolymers lack terminal activity in chain-extension polymerization, leading to a scarcity of block structures that could integrate rigid/soft chain properties. Specifically, reversible-deactivation process yields ethylene-X and fluoroalkene-X connections in termini, with X representing the chain-end group (e.g., chain-transfer agent, CTA). The ethylene-X linkage shows poor reactivity of re-activation in the (co)polymerizations of ethylene25 and fluoroalkenes26, restricting radical formation for further chain-growth. Meanwhile, propagating radicals ending with fluoroalkene units are highly prone to irreversible chain transfer to solvent and polymer, yielding dead chains of low molar masses despite trials to optimize CTAs and catalysts27,28.

Beyond RDRP of ethylene, photoredox catalysis has stimulated the development of controlled (co)polymerization of diverse monomers29,30,31,32, metal-free RDRPs33,34,35, spatiotemporally regulated techniques (e.g., surface modification, 3D printing)36,37 and high-throughput polymerizations38,39. However, the integration of photoredox chemistry and RDRP in ethylene copolymerization has not been realized to our knowledge. We envisioned that a combined design of photocatalyst (PC) and CTA could promote reversible-deactivation control in the ethylene-fluoroalkene copolymerization. By systematically manipulating their redox properties33, excited PC* of sufficient reducing ability coupled with CTA of a matchable redox potential is possible to facilitate re-activation of dormant species with an ethylene-CTA linkage, despite the proven difficulties of generating radicals from RCH2-X (X = CTA25,26, I40, Co4,41) chain-ends under mild conditions.

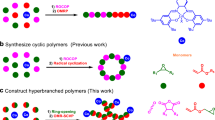

In this work, we developed a photoredox-mediated RDRP of ethylene and CTFE for the first time by leveraging a highly reductive triple-armed organic PC and a semi-fluorinated dithiocarbamate, which enabled the preparation of well-defined ethylene-CTFE copolymer under visible-light-driven, metal-free, low-pressure conditions (Fig. 1). The obtained ECTFE displays excellent alternating incorporation of ethylene and CTFE units, exhibiting outstanding crystallinity and high melting points, superior to those of various commercial polymers. Notably, this synthetic breakthrough furnishes ECTFE with outstanding chain-end activity for chain-extension (co)polymerization, yielding ECTFE-polar block copolymers that remain arduous by previous polymerization techniques. The facile combination of rigid ECTFE with soft blocks via controlled radical polymerization/chain-extension could facilitate materials design with tunable mechanical properties from thermoplastics to elastomers by tailoring chain structures.

Results and discussion

Explorations of copolymerization conditions

Inspired by recent developments in photoredox-mediated RDRPs, we envisioned that extending the conjugated structures and increasing heterocycles could be useful to improve properties of photoredox catalysts33,42, and it would be convenient to link photoredox heterocycles onto different cores via cross-coupling reactions. At the outset of this study, we synthesized a series of phenothiazine (PTZ) substituted compounds by using triphenylamine (PC1), biphenyl (PC2), naphthalene (PC3) and diphenyl ether (PC4) as bridging units, respectively (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Figs. 1-15). While the enhanced reducing ability could promote the oxidative quenching of PC* with CTA, the improved light adsorption and lifetimes could facilitate the photo-induced electron transfer (PET) in a PET-RAFT process29. In comparison to 10-phenylphenothiazine (Eθ(PC•+/PC*) = −2.00 V versus SCE in dichloromethane, DCM) employed by multiple groups in photopolymerization studies43,44,45,46, the PTZ-armed compounds (PC1-PC4) exhibited stronger photo-excited reducing ability (Eθ(PC•+/PC*) = −2.17 V to −2.22 V versus SCE in DCM, Supplementary Fig. 16, Supplementary Table 1), higher molar absorptivity in the visible-light region (8837-13,965 M-1 cm-1 versus < 100 M-1 cm-1 at 410 nm, Supplementary Figs. 17-18), and longer fluorescence lifetimes (5.68-6.36 ns versus 3.02 ns, Supplementary Fig. 19). In addition, cyclic voltammetry confirmed the highly reversible oxidation behavior of the PTZ-armed PC (Supplementary Fig. 20), suggesting good stability of PC•+ in a redox process.

Then, we examined the ethylene-CTFE copolymerization in the presence of CTAs (Fig. 2b), PCs, and carbonate solvents by exposing glass thick-walled tubes to visible-light irradiation (white LED light). The pressure was maintained below 5 atm during our condition optimization, in contrast to the much higher pressure typically required for free radical polymerizations of ethylene and/or CTFE47. While the extremely poor solubility of fluoropolymers has precluded characterization in size exclusion chromatography (SEC), 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene was adopted as an eluent in high-temperature SEC at 160 °C to characterize molar masses (Mn) and dispersities (Đ).

When CTAs from 1 to 3 (peak potentials, Ep = −2.36 V to −2.05 V versus SCE, Fig. 2c) were employed, the reactions yielded copolymers of high dispersities (Đ = 1.78-2.12, entry 1 in Table 1), which could be attributed to their insufficient reactivity to oxidize PC1*, thus hampering the cleavage of CTAs to form active carbon radicals. The polymerizations with more oxidative CTAs from 4 to 7 (Ep = −1.90 V to −1.61 V versus SCE, entries 2-5 in Table 1, Supplementary Figs. 21-23, and Supplementary Table 2) afforded polymers of Đ < 1.60. The adoption of CTAs 4 and 6 yielded more than 0.8 g of products, suggesting higher reaction efficiencies than those using N,N-diphenyl (CTA 5) and N-phenyl-N-pyridyl (CTA 7) substituted agents. When CTAs 8 and 9 with Ep > −1.55 V versus SCE (entry 6 in Table 1 and Supplementary Figs. 24-26) were examined, the reactions gave poor yields (<0.3 g), presumably due to the mismatched redox potentials between CTAs and PC*, which led to CTA decomposition.

Motivated by the promising results obtained with CTA 6 (Đ = 1.43, 0.98 g), we replaced the electron-deficient pyridyl with 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl to give CTAs 10-12 (Supplementary Figs. 27-38). Because PC1* exhibits excessively strong reducing ability for CTA 6 (−2.22 V versus −1.62 V), we thought that CTAs 10-12 of slightly lower oxidative potentials could be more suitable to interact with PC1*. Among the three compounds (entries 7-9 in Table 1), the polymerization with CTA 10 (Ep = −1.74 V versus SCE) yielded ECTFE of the lowest dispersity (Đ = 1.29, Mn = 14.1 kDa) with good reaction activity relative to catalyst loading and exposure time (2.43 × 105 g molpc-1 h-1, Supplementary Eq. 1). Given the use of two gaseous monomers under low pressure, the efficiency of this room-temperature copolymerization is remarkable and could be further improved by optimizing photoreaction techniques. Among the tested CTAs, the employment of CTA 10 afforded ECTFE of the highest melting point (Tm = 220.6 °C) and crystallinity (χc = 65.6%) as determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, Supplementary Fig. 47).

When the copolymerizations were probed at initial ratios of [ethylene]/[CTFE] = 2/1 (entry 10) and 1/2 (entry 11) with PC1 and CTA 10, polymers of Mn = 12.0 and 13.8 kDa were obtained without losing control over dispersities (Đ < 1.35). Replacing PC1 with catalysts from PC2 to PC4 afforded 0.88-1.28 g of polymers with Đ = 1.33-1.45 (entry 12). The resulting lower melting points (Tm = 204.3-208.2 °C) and decreased crystallinity ( χc = 38.5-46.9%) could relate to the declined molar masses (Mn = 9.6-11.2 kDa). Further variations of PCs and solvents resulted in increased dispersities and/or decreased crystallinity (Supplementary Tables 3-5). We further prepared 1H,1H,2H,2H-nonafluorohexyl (nC4F9CH2CH2-) substituted dithiocarbamate CTA 13 (Supplementary Figs. 39-42) as an analogue of the ethylene-CTA linkage of dormant chain. This compound exhibits a potential (Ep = −1.83 V versus SCE, Supplementary Fig. 43) more positive than that of PC1* (Eθ(PC•+/PC*) = −2.22 V versus SCE), supporting that the ethylene-CTA connection could be re-activated in the photo-induced reduction by PC1*33.

Investigations on copolymerization process

Next, we probed the copolymerization process under optimized conditions of PC1 and CTA 10 at [ethylene]/[CTFE]/[CTA] = 300/300/1 using white LED light irradiation. Inspired by previous studies on ethylene polymerization48,49,50,51, the relationship of Mn versus yield of ECTFE polymer was analyzed (Fig. 3a). Molar masses of polymers increased along with yields, suggesting that the chain length grew continuously without dramatically forming new chains. Throughout the process, dispersities were maintained in a range of Đ = 1.21-1.43, which is particularly good for ethylene/CTFE-based (co)polymerization. The poor solubility of ECTFE caused aggregation during polymerization, which hampered the chain-ends from participating in the chain-growth control, particularly for longer chains52. Consequently, higher dispersities were observed for ECTFE of higher molar masses. The copolymerization process is apparently different from conventional free radical polymerizations that yield polymers without control over molar mass and normally provide higher dispersities during propagation53. SEC profiles of the obtained polymers are unimodal and symmetric without discernible shoulder peaks (Fig. 3b), supporting the presence of chain-growth regulation.

Characterizations of ethylene-CTFE copolymer

To study the chemical structure of obtained copolymers, we analyzed nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of ECTFE prepared at [ethylene]/[CTFE] = 1/1 (P1, Mn = 9.6 kDa, Mn,MALLs = 7.9 kDa, Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 10). Proton resonances corresponding to Ha, Hb, and Hd from N-methyl-N-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl, Hc from ethyl ester, were clearly detected in 1H NMR (blue line in Fig. 4b), in sharp contrast to a commercial ethylene-CTFE copolymer (Halar®, black line) that showed the absence of signals from substituents from CTA. The integration areas (e.g., Hd versus Hc) indicate an almost equal amount of dithiocarbamate and ethyl groups in the chain, supporting the good chain-end fidelity. In ethylene-CTFE copolymers, proton signals of ethylene units can be classified into four subgroups depending on the chemical environments, including He1 (2.26-2.80 ppm), He2 (1.95-2.26 ppm), He3 (1.46-1.85 ppm), and He4 (1.00-1.45 ppm). While the detection of He3 and He4 validated the existence of homo-propagation segments of PE in Halar®, such signals were dramatically weakened in P1, accompanied by increased signals (e.g., He1) corresponding to methylene groups vicinal to CTFE units. In 19F NMR spectrum, signals at −106.5 ppm and −129.7 ppm further evidenced the presence of homo-propagation segments of PCTFE in Halar® (black line in Fig. 4c). In contrast, a clean 19F NMR spectrum was observed for P1, with Fa from ‒CF3 in CTA, Fb (‒CF2‒) and Fc (‒CFCl‒) from CTFE repeating units. 1H and 19F NMR results indicate that homo-propagation of ethylene and CTFE was successfully minimized via the organocatalyzed copolymerization. While conventional high-temperature radical polymerizations have caused PE branching in ECTFE (0.80-1.10 ppm in 1H NMR, Supplementary Fig. 62), which could decrease crystallinity, such branching was not obviously detected in this mild polymerization (Supplementary Figs. 55, 57 and 59). On this basis, we prepared ECTFE copolymers at [ethylene]/[CTFE] = 1/4 (P2, Supplementary Fig. 57) and 4/1 (P3, Supplementary Fig. 59), and calculated the fractions of alternating units (ethylene-alt-CTFE) in copolymers (Falt, Supplementary Eq. 5) by analyzing the characteristic proton signals of ethylene units in 1H NMR. The obtained ECTFE exhibits Falt = 97.1% in P1, 99.2% in P2 and 88.3% in P3, much higher than that of Halar® (Falt = 79.8%, Supplementary Table 9), demonstrating the superior sequence control in the photoredox-mediated copolymerization.

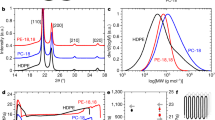

a Chemical structure of P1. b 1H NMR spectra and c 19F NMR spectra of P1 (blue line) and Halar® (black line) with C2D2Cl4 at 120 °C. d MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of ethylene-trifluoroethylene copolymer prepared by reducing ECTFE. e XRD patterns of P5, Halar®, PE and PCTFE. Insets are 2D-WAXD patterns of P5 and Halar®.

Furthermore, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectroscopy was utilized to analyze the obtained copolymer. Although this technique has been massively employed to characterize absolute molecular weights of polymers, no example has been reported for ECTFE, probably owing to the difficulty in charging and vaporizing this non-polar and high-melting-point fluoropolymer. During the MALDI-TOF characterization, we found that the chlorine substituents in ECTFE were highly prone to fragmentation (Supplementary Fig. 65). To circumvent this issue, we employed [(CH3)3Si]3SiH to reduce ECTFE before the measurement, which converted ECTFE completely into ethylene-trifluoroethylene copolymer P4 (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 66). The MALDI-TOF spectrum of P4 exhibited one set of peaks separated by Δmass = 110.03, close to the total molecular weight of an ethylene-trifluoroethylene unit, further evidencing the outstanding alternating sequence of the original ECTFE.

In order to probe the influence of macromolecular structure on crystalline behavior, copolymers were further characterized by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) and 2D wide-angle X-ray diffraction (2D-WAXD). ECTFE P5 (Mn = 35.1 kDa) was prepared to compare with Halar® of a similar molar mass (Mn = 36.8 kDa). XRD patterns of P5 (blue line in Fig. 4e) revealed two peaks at 2θ = 18.10° and 38.68°, corresponding to the lattice planes of (100) and (200), respectively. In contrast, the peak of (100) plane of Halar® (black line) shifted to 2θ = 17.92°, suggesting a larger lattice spacing (d = 4.95 Å versus 4.89 Å) as estimated by Bragg’s equation. The sharp XRD signal of P5 at 2θ = 18.10° is well aligned with its narrow diffraction halo detected in 2D-WAXD (inset in Fig. 4e), different from the diffuse scattering observed with Halar®. Based on Gaussian fitting, the shoulder peak at about 21.70° and the broad peak ranging from 30.85° to 37.46° (black line) support the probable existence of PE (green line) and PCTFE (yellow line) segments in Halar®, agreeing with NMR results (Supplementary Figs. 62-64). By fitting the XRD patterns, the full width at half maximum (FWHM, 1.29° versus 1.79°) demonstrates that the grain size in P5 (13.02 nm) is larger than that in Halar® (9.38 nm) according to Scherrer’s formula, which is consistent with the WAXS results (Supplementary Fig. 72). The above characterization results support that the defective alternating sequence in commercial Halar® affects the crystal interplanar spacing and crystal periodicity, resulting in crystallographic defects. In comparison, the well-defined structure of P5 allows increased long-range order in chain folding to furnish enhanced diffraction intensity and increased crystalline grain size.

Then, we compared Tm and χc of different polymers by DSC (Supplementary Table 13). Utilizing our synthetic method, compared to P5 with χc = 69.9% and Tm = 235.1 °C, the ECTFE of a higher molar mass (Mn = 123.5 kDa) provides χc = 71.2% and Tm = 263.8 °C, demonstrating the potential of tuning melting point by tailoring the chain length while maintaining high crystallinity. Comparatively, commercial ethylene-CTFE copolymers afforded Tm = 213.9 °C (χc = 24.5%) at Mn = 36.8 kDa, and Tm = 244.4 °C (χc = 43.2%) at Mn = 135.8 kDa, and exhibited an additional Tm = 105.9 °C attributable to PE segments (Supplementary Fig. 74). Furthermore, the results of our copolymers are superior than those of a variety of commercial polymers, such as PEs (Tm = 109.9-136.6 °C, χc = 39.5-52.6%), polyethylene oxide (PEO, Tm = 57.8-62.9 °C, χc = 55.9-64.1%) and ethylene-propylene copolymer (EP, Tm = 82.1-101.0 °C, χc = 34.0-53.0%) under identical measurement conditions. Leveraging the unique characteristics of fluorocarbons, ECTFEs prepared by this method are promising to explore materials resistant to solvents, deformation and corrosive environments at elevated temperatures.

Synthesis of block copolymers

To demonstrate the synthetic advantage, we prepared ECTFE P6a (Mn = 4.1 kDa, Đ = 1.24) as a macroinitiator and conducted chain-extension polymerizations with different comonomers to prepare block copolymers under visible-light irradiation using PC1 (Fig. 5a). When CTFE was combined with vinyl acetate (VAc) or isobutyl vinyl ether (iBVE), we gained copolymers of ECTFE-b-P(CTFE-co-VAc) (P7, Mn = 20.0 kDa, Đ = 1.35) and ECTFE-b-P(CTFE-co-iBVE) (P8, Mn = 31.2 kDa, Đ = 1.46) with binary units in both blocks. Alternatively, the adoption of only VAc furnished ECTFE-b-PVAc (P9, Mn = 17.8 kDa, Đ = 1.50) with homopolymer as the second block. During the chain-extension experiments, SEC profiles of block copolymers underwent clear shifts to lower retention times without detecting shoulder peaks or tailing (Fig. 5b). After hydrolyzing VAc units into vinyl alcohol (VA), an amphiphilic copolymer of ECTFE-b-PVA (P10, Mn = 16.9 kDa, Đ = 1.49, Supplementary Fig. 75) was prepared from P9, illustrating the attractive potential of post-modification.

a Synthesis of ECTFE-based block copolymers via chain-extension polymerization and post-modification reaction (In SEC characterizations, P6a-P9 were analyzed with 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene (160 °C), P10 was analyzed with N,N-dimethylformamide (25 °C)). b SEC profiles of ECTFE P6a and block copolymers (P7-P9). c DOSY NMR spectra of ECTFE P6a, and block copolymers (CDCl3 and DMSO-d6). d DSC curves of copolymers from P6a to P10.

Diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) NMR confirmed the formation of block copolymers of P7-P10 (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Figs. 77-80), which exhibited diffusion coefficients different from P6a (2.95 × 10-10 m2 s-1), supporting the successful covalent linkage of the second blocks to the macroinitiator. Variations of chemical compositions in block copolymers (P7-P9) and complete hydrolysis into P10 were evidenced by NMR spectra (Supplementary Figs. 81-84). In DSC measurements (Fig. 5d), all block copolymers exhibited melting points originating from ECTFE (P6a, Tm = 208.7 °C), as well as glass transition temperatures (Tg) caused by the second blocks. For example, ECTFE-b-P(CTFE-co-VAc) P7 shows Tg = 62.6 °C and Tm = 205.9 °C, and ECTFE-b-PVA P10 displays Tg = 85.2 °C and Tm = 201.7 °C. Taken together, the successful synthesis of block copolymers not only validates the outstanding chain-end activity/fidelity in our approach but also furnishes unprecedented semi-crystalline polymers with covalently linked polar and non-polar blocks, which is informative to materials innovation.

Investigations on mechanical properties of block copolymers

We conducted tensile tests to probe the mechanical properties of the obtained block copolymers. As shown in Fig. 6a, P7 exhibited thermoplastic behavior, featuring tensile strength of 13.9 ± 0.3 MPa and Young’s modulus of 175.1 ± 0.6 MPa, along with a strain hardening phenomenon at increased tensile strain. The replacement of P(CTFE-co-VAc) block in P7 with P(CTFE-co-iBVE) reduced the tensile strength of P8 (9.2 ± 0.2 MPa), significantly increased elongation at break (545 ± 12% versus 186 ± 10%) and tensile toughness (34.9 ± 0.3 versus 21.8 ± 0.2 MJ m-3), supporting the tunability of mechanical stiffness by varying the second block. Then, two ECTFE-b-P(CTFE-co-iBVE) copolymers (P11 of Mn = 86.9 kDa, P12 of Mn = 106.7 kDa, Supplementary Fig. 85) were prepared by chain-extensions from ECTFE (P6b, Mn = 8.9 kDa) to introduce different lengths of soft blocks. Both P11 and P12 exhibited outstanding extensibility, with elongation at break reaching 792 ± 15% and 1246 ± 22%, respectively, suggesting elastomeric behavior without showing a yield point in the stress-strain curves (Supplementary Table 14). We further examined the elastic recovery of P11 and P12 at 300% strain with ten elongation cycles, which afforded maximum recoveries of 83.6% for P11 and 69.5% for P12 (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 86).

Subsequently, seven cycles of loading-unloading tensile tests were applied to P12 step by step up to higher strains. In Fig. 6c, hysteresis behavior persisted throughout the measurement, where the residual strain at zero stress increased with cycles, and stress at a fixed strain decreased in each subsequent curve. The cyclic tensile tests at strains of 100%, 200%, 400% and 600% (Fig. 6d) showed that unrecovered strains continuously accumulated after the first cycle, suggesting the occurrence of a permanent structural change during the initial cycle. Such behavior could be consistent with plastic deformation and energy loss during stretching. Additionally, the linear structure of block copolymers and good thermal stability facilitated the recovery of destroyed P12 via melting processing (Fig. 6e), without apparent deterioration in the mechanical performance (Supplementary Fig. 87). Collectively, the tensile tests demonstrate that both thermoplastics and elastomers could be successfully obtained by tailoring composition and block length in the copolymers, which has not been realized in ethylene-fluoroalkene copolymers before.

In this work, a photoredox-mediated ethylene-CTFE copolymerization was developed to realize controlled synthesis of highly crystalline polymers, enabling facile preparation of ECTFE with outstanding alternating sequence under mild conditions through the rational design of PCs and CTAs. The enhanced periodicity of repeating units endowed ECTFE with a long-range ordered structure and reduced crystallographic defects, bringing increased crystallinity and melting point. Notably, this method has yielded ECTFE with high chain-end fidelity/activity, allowing chain-extension and post-modification to access ECTFE-polar block copolymers that remain difficult to synthesize by other means. The ease of accessing such block copolymers offers the feasibility to tune mechanical properties, largely spanning from thermoplastics to elastomers. Given the practical applications of ethylene-fluoroalkene copolymers across different industries, we expect that the enhanced and tunable properties of block copolymers create improved opportunities to develop high-performance materials.

Methods

Characterization methods

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy

NMR and DOSY NMR spectra were collected with Avance NEO Bruker spectrometers (400 MHz, 600 MHz). High-temperature NMR spectra were tested on an Avance III HD Bruker spectrometer (500 MHz) with C2D2Cl4 at 120 °C.

High temperature size-exclusion chromatography (HT-SEC)

Molecular weights and molecular weight distributions of ECTFE polymers were determined by an Agilent 1260 Infinity II HT SEC chromatograph equipped with six Agilent PL gel Olexis columns operating at 160 °C using 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene (TCB) as a solvent. The system was calibrated with a polystyrene standard.

Cyclic voltammetry (CV)

CV measurements were recorded on a CHI660E electrochemical workstation using a three-electrode cell (saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as a reference electrode, glassy carbon as a working electrode, Pt wire as a counter electrode), and nBu4NBF4 as an electrolyte.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

DSC characterizations were performed on a DSC 250 thermal analysis system (TA Instrument) with a heating or cooling rate of 10 °C/min under N2. Glass transition temperature (Tg) and melting temperature (Tm) were obtained from the second heating scan.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

XRD analysis of ECTFE powder was conducted using an X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku Smatlab 9 KW) equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm). The measurements were performed over a 2θ range of 10-70° with a step size of 0.02° at room temperature. Two-dimensional wide-angle X-ray diffraction (2D WAXD) patterns were recorded by the same instrument operated at 45 kV voltage with 200 mA current.

General procedure for the copolymerization

A 25 mL glass thick-walled Schlenk tube charged with CTA, PC (Supplementary Tables 3-6) and 3 mL anhydrous DEC/DMC (v/v = 2/1) was cooled at −50 °C under N2. Chlorotrifluoroethylene (CTFE, 3.50 g) was bubbled into the tube. After cooling for 5 min, ethylene gas was added to the tube at a constant flow rate (1 g/min) with cooling by liquid nitrogen, with the amount estimated according to the collection time. The tube was carefully deoxygenated with three freeze-pump-thaw cycles under N2. Then, the tube was sealed and kept in front of a white LED bulb at room temperature for copolymerization, and was blown with compressed air to avoid heating.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Corrigan, N. et al. Reversible-deactivation radical polymerization (controlled/living radical polymerization): from discovery to materials design and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 111, 101311 (2020).

Chen, Z. & Brookhart, M. Exploring ethylene/polar vinyl monomer copolymerizations using Ni and Pd α-diimine catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 1831–1839 (2018).

Chen, C. Designing catalysts for olefin polymerization and copolymerization: beyond electronic and steric tuning. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 6–14 (2018).

Kermagoret, A., Debuigne, A., Jérôme, C. & Detrembleur, C. Precision design of ethylene- and polar-monomer-based copolymers by organometallic-mediated radical polymerization. Nat. Chem. 6, 179–187 (2014).

Wolpers, A. et al. Iodine-transfer polymerization (ITP) of ethylene and copolymerization with vinyl acetate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 19304–19310 (2020).

Wolpers, A., Baffie, F., Monteil, V. & D’Agosto, F. Statistical and block copolymers of ethylene and vinyl acetate via reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer polymerization. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 42, 2100270 (2021).

Franssen, N. M. G., Reek, J. N. H. & de Bruin, B. Synthesis of functional ‘polyolefins’: state of the art and remaining challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 5809–5832 (2013).

Keyes, A. et al. Olefins and vinyl polar monomers: bridging the gap for next generation materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 12370–12391 (2019).

Dau, H. et al. Linear block copolymer synthesis. Chem. Rev. 122, 14471–14553 (2022).

Demarteau, J. et al. Functional polyethylene (PE) and PE-based block copolymers by organometallic-mediated radical polymerization. Macromolecules 52, 9053–9063 (2019).

Zeng, T.-Y., Xia, L., Zhang, Z., Hong, C.-Y. & You, Y.-Z. Dithiocarbamate-mediated controlled copolymerization of ethylene with cyclic ketene acetals towards polyethylene-based degradable copolymers. Polym. Chem. 12, 165–171 (2021).

Baffie, F., Lansalot, M., Monteil, V. & D’Agosto, F. Telechelic polyethylene, poly(ethylene-co-vinyl acetate) and triblock copolymers based on ethylene and vinyl acetate by iodine transfer polymerization. Polym. Chem. 13, 2469–2476 (2022).

Bergerbit, C. et al. Synthesis of PMMA-based block copolymers by consecutive irreversible and reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer polymerizations. Polym. Chem. 10, 6630–6640 (2019).

Dau, H. et al. Dual polymerization pathway for polyolefin-polar block copolymer synthesis via MILRad: mechanism and scope. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 21469–21483 (2020).

Keyes, A., Dau, H., Matyjaszewski, K. & Harth, E. Tandem living insertion and controlled radical polymerization for polyolefin–polyvinyl block copolymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202112742 (2022).

Zhao, Y., Jung, J. & Nozaki, K. One-pot synthesis of polyethylene-based block copolymers via a dual polymerization pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 18832–18837 (2021).

Kay, C. J. et al. Polyolefin-polar block copolymers from versatile new macromonomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 13921–13934 (2018).

Ciftci, M., Norsic, S., Boisson, C., D’Agosto, F. & Yagci, Y. Synthesis of block copolymers based on polyethylene by thermally induced controlled radical polymerization using Mn2(CO)10. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 216, 958–963 (2015).

Boschet, F. & Ameduri, B. (Co)polymers of chlorotrifluoroethylene: synthesis, properties, and applications. Chem. Rev. 114, 927–980 (2014).

Bertasa, A. M. in Encyclopedia of Membranes (eds Drioli E. & Giorno L.) 904-905 (Springer, 2016).

Liu, Z. et al. Creating ultrahigh and long-persistent triboelectric charge density on weak polar polymer via quenching polarization. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2302164 (2023).

Gong, X. et al. Extending the calendar life of fiber lithium-ion batteries to 200 days with ultra-high barrier polymer tubes. Adv. Mater. 36, 2409910 (2024).

Stanitis, G. in Modern Fluoropolymers: High Performance Polymers for Diverse Applications (ed Scheirs, J.) 525–539 (Wiley, 1997).

Sibilia, J. P., Roldan, L. G. & Chandrasekaran, S. Structure of ethylene–chlorotrifluoroethylene copolymers. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Phys. 10, 549–563 (1972).

Wolpers, A., Bergerbit, C., Ebeling, B., D’Agosto, F. & Monteil, V. Aromatic xanthates and dithiocarbamates for the polymerization of ethylene through reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 14295–14302 (2019).

Guerre, M. et al. Deeper insight into the MADIX polymerization of vinylidene fluoride. Macromolecules 48, 7810–7822 (2015).

Puts, G., Venner, V., Ameduri, B. & Crouse, P. Conventional and RAFT copolymerization of tetrafluoroethylene with isobutyl vinyl ether. Macromolecules 51, 6724–6739 (2018).

Guerre, M. et al. Synthesis of PEVE-b-P(CTFE-alt-EVE) block copolymers by sequential cationic and radical RAFT polymerization. Polym. Chem. 9, 352–361 (2018).

Lee, Y., Boyer, C. & Kwon, M. S. Photocontrolled RAFT polymerization: past, present, and future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 3035–3097 (2023).

Sifri, R. J., Ma, Y. & Fors, B. P. Photoredox catalysis in photocontrolled cationic polymerizations of vinyl ethers. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 1960–1971 (2022).

Lu, P., Kensy, V. K., Tritt, R. L., Seidenkranz, D. T. & Boydston, A. J. Metal-free ring-opening metathesis polymerization: from concept to creation. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 2325–2335 (2020).

Chen, K., Guo, X. & Chen, M. Controlled radical copolymerization toward well-defined fluoropolymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310636 (2023).

Wu, C. et al. Rational design of photocatalysts for controlled polymerization: effect of structures on photocatalytic activities. Chem. Rev. 122, 5476–5518 (2022).

Theriot, J. C. et al. Organocatalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization driven by visible light. Science 352, 1082–1086 (2016).

Singh, V. K. et al. Highly efficient organic photocatalysts discovered via a computer-aided-design strategy for visible-light-driven atom transfer radical polymerization. Nat. Catal. 1, 794–804 (2018).

Lee, K., Corrigan, N. & Boyer, C. Rapid high-resolution 3D printing and surface functionalization via type I photoinitiated RAFT polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 8839–8850 (2021).

Jung, K. et al. Designing with light: advanced 2D, 3D, and 4D materials. Adv. Mater. 32, 1903850 (2020).

Hu, X. et al. Red-light-driven atom transfer radical polymerization for high-throughput polymer synthesis in open air. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 24315–24327 (2023).

Oliver, S., Zhao, L., Gormley, A. J., Chapman, R. & Boyer, C. Living in the fast lane—high throughput controlled/living radical polymerization. Macromolecules 52, 3–23 (2019).

Boyer, C., Valade, D., Sauguet, L., Ameduri, B. & Boutevin, B. Iodine transfer polymerization (ITP) of vinylidene fluoride (VDF). Influence of the defect of VDF chaining on the control of ITP. Macromolecules 38, 10353–10362 (2005).

Bryaskova, R. et al. Copolymerization of vinyl acetate with 1-octene and ethylene by cobalt-mediated radical polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 45, 2532–2542 (2007).

Corbin, D. A. & Miyake, G. M. Photoinduced organocatalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization (O-ATRP): precision polymer synthesis using organic photoredox catalysis. Chem. Rev. 122, 1830–1874 (2022).

Gong, H., Zhao, Y., Shen, X., Lin, J. & Chen, M. Organocatalyzed photo-controlled radical polymerization of semi-fluorinated (meth)acrylates driven by visible light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 333–337 (2018).

Treat, N. J. et al. Metal-free atom transfer radical polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 16096–16101 (2014).

Chen, M., MacLeod, M. J. & Johnson, J. A. Visible-light-controlled living radical polymerization from a trithiocarbonate iniferter mediated by an organic photoredox catalyst. ACS Macro Lett. 4, 566–569 (2015).

Pan, X. et al. Mechanism of photoinduced metal-free atom transfer radical polymerization: experimental and computational studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2411–2425 (2016).

Beuermann, S. & Buback, M. in High Pressure Molecular Science (eds Winter R. & Jonas J.) 331–367 (Springer, 1999).

Long, B. K., Eagan, J. M., Mulzer, M. & Coates, G. W. Semi-crystalline polar polyethylene: ester-functionalized linear polyolefins enabled by a functional-group-tolerant, cationic nickel catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 7106–7110 (2016).

Dommanget, C., D’Agosto, F. & Monteil, V. Polymerization of ethylene through reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 6683–6686 (2014).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Controlled radical polymerization of ethylene using organotellurium compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 305–309 (2018).

Eagan, J. M. et al. Combining polyethylene and polypropylene: enhanced performance with PE/iPP multiblock polymers. Science 355, 814–816 (2017).

Baffie, F., Sinniger, L., Lansalot, M., Monteil, V. & D’Agosto, F. From radical to reversible-deactivation radical polymerization of ethylene. Prog. Polym. Sci. 162, 101932 (2025).

Liu, S. The future of free radical polymerizations. Chem. Mater. 36, 1779–1780 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by NSFC (nos. 22425103 and 22171051 to M.C.), the Shanghai Pilot Program for Basic Research-Fudan University 21TQ1400100 (no. 21TQ007 to M.C.), and the State Key Laboratory of Molecular Engineering of Polymers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.X. and M.C. conceived the idea and experiment. M.X., Q.C., K.C., and X.G. conducted synthesis and characterization. M.X. and S.H. analyzed data. M.X. and M.C. wrote the manuscript and Supplementary Information. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, M., Chen, Q., Han, S. et al. Photoredox-controlled alternating copolymerization enables highly crystalline structures and block copolymers from thermoplastic to elastomer. Nat Commun 17, 265 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66962-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66962-8