Abstract

The array of neural network training techniques that invoke optimization but rely on ad hoc modification for validity suggests that optimization-based training is misguided. Shortcomings of optimization-based training are brought to strong relief by overfitting, where naive optimization produces spurious outcomes. Here, we introduce simmering, a physics-based method that trains neural networks to generate “good enough” weights and biases, paradoxically outperforming leading optimization-based approaches. Instead of optimizing, simmering systematically samples non-optimal weights and biases to generate an ensemble that provides sufficient representations of the underlying phenomenon. Simmering corrects neural networks that are overfit by optimization, and produces more generalizable predictions if deployed from the outset compared to other overfitting mitigation methods. Our results question optimization as a paradigm for training transformers, and feedforward and convolutional neural networks. We leverage information-geometric arguments to point to the existence of classes of sufficient-training algorithms that do not take optimization as their starting point.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although neural networks’ universal estimation capability1,2,3,4 allows them to represent many complex data relationships5, that capability makes training generalizable networks challenging. The over-parameterization that supports the universal capabilities of neural networks nonetheless gives key advantages over other estimators in settings where complex data produce a training loss landscape that is non-convex and has many local minima6,7. Yet noise in training data can misdirect the parameter estimation process towards an overspecified representation that accurately respects idiosyncrasies in training data, but that severely limits generalizability8,9,10. This accuracy-generalizability discord is exacerbated by optimization-based training methods, which are overly effective at exploiting universal estimation capacity to achieve minimized-loss representations of training data.

The danger of combining the excessive expressiveness of a neural network and discrepant data with optimization is brought to particular relief by overfitting11,12,13,14,15. Overfit neural networks are inevitable when an over-parameterized architecture is combined with an efficient optimization algorithm6 (e.g., Adam16). Optimization yields high-complexity networks that generalize poorly because optimization-based training cannot distinguish between the ground truth and the noise in the data during training. Even in large- and augmented-data regimes, with correspondingly advanced architectures such as ResNet17 and Transformers18, modern networks can memorize noise or random labels with negligible training error while still exhibiting poor generalization,19 indicating that overfitting is a fundamental learning challenge that transcends dataset and model size19,20,21. Attempts to mitigate overfitting, e.g., early stopping22, bagging23, boosting24, dropout21, all account for data uncertainty by incorporating deviations from empirical error minimization into training. However, the effectiveness of most overfitting mitigation techniques relies on the data distribution satisfying specific assumptions12, and is thus problem dependent. Nonetheless, the success of avoiding overfitting via increased training loss12 suggests that more generalizable representations of ground truth are near-optimal rather than optimal11. Thus, training paradigms that are founded on an alternate premise, e.g., sufficiency rather than optimality, could produce non-overfit, generalizable estimators while still benefiting from the expressive capacity of neural networks.

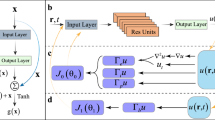

Here, we demonstrate that simmering, an example of a sufficient-training algorithm, can improve on optimization-based training. Using examples of regression and classification problems with feedforward and convolutional neural networks, we deploy Simmering to retrofit, or reduce overfitting, in networks that are overfit via conventional implementations of Adam16. We also show ab initio simmering, without an optimized initial condition, outperforms optimized models with either early stopping or dropout in learning the CIFAR-10 dataset25 with ConvNet26. In addition, given fixed, equivalent learning rates, simmering achieves a higher accuracy in language translation27 with a Transformer18 than early stopping or dropout in less than half as many training epochs. Moreover, ab initio simmering yields ensemble prediction distributions that provide additional insight into the unseen data distribution. Our approach leverages Nosé-Hoover chain thermostats from molecular dynamics28 to treat network weights and biases as particles imbued with auxiliary, finite-temperature dynamics and forces generated by backpropagation29. The finite-temperature dynamics act as a minimally biased model of the data noise that systematically prevents the network parameters from settling at an optimum.

Our results indicate that simmering is a viable approach to prevent the overfitting that is inherent in optimization-based training. To understand why simmering works, we use information geometry arguments30 to show that simmering is but one of a family of sufficient-training algorithms that improve on optimization-based training by leveraging filtration in a way that exploits generic features of loss function landscapes. Our implementation of simmering, a filter-based neural network training method, is available open source at Ref. 31. Within the general class of sufficient learning algorithms, information theoretic arguments indicate that simmering is one of a family of filter-based algorithms that make minimally-biased assumptions about the form of deviation from ground truth present in the training data. This opens the door to statistical-physics-based sufficient-training approaches, e.g., by leveraging other molecular dynamics algorithms.

Results

Sufficient training by simmering

Existing, optimization-based training algorithms that work to mitigate overfitting are engineered to avoid optimizing the empirical error because optimized sets of weights and biases do not reproduce ground truth in generic problems. The fact that generalizable representations of ground truth do not optimize the empirical error suggests the need to systematically explore non-optimal configurations. Exploring non-optimal configurations in generic problems, where it is not known a priori how training data depart from ground truth, motivates generating minimally biased deviations from optimality. Information theory suggests32 employing a generating function that is the Pareto-Laplace transform30 of the training loss

where x is the set of neural network parameters (weights and biases), \(\overrightarrow{x}=(\overrightarrow{w},\overrightarrow{b})\), N is the total number of neural network parameters, \(L(x,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) is the loss function evaluated over the training data \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}\), and β is the Laplace transform variable. Z is a generating function for sufficiently trained networks, and generates networks that minimize training loss in the limit β → ∞.

We use Eq. (1) to generate sufficiently trained networks algorithmically by identifying \(Z(\beta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) as a partition function in statistical mechanics30. The training algorithm (see “Methods”) treats \(Z(\beta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) as the thermal, configuration space integral of a system of classical particles representing the weights and biases of the network, with each particle’s 1D motion driven by an interaction potential energy determined by the training loss. In this representation we take T = 1/β as the system temperature. Without loss of generality, we lift this configuration space to a phase space by augmenting each weight and bias with an auxiliary, canonically conjugate momentum and a canonical, non-relativistic kinetic energy. These momenta and kinetic energy impart the system with auxiliary dynamics.

This dynamical approach entails gradient forces on weights and biases that can be computed via backpropagation. We thermalize the dynamics to reproduce the distribution Eq. (1). We operationalize the thermalization via numerical integration of the equations of motion of the neural network coupled to a Nosé-Hoover chain thermostat, which we implement (see Supplementary Methods) by symplectic integration33,34. For portability, and to facilitate use for problems beyond those we study in detail below, we implement the algorithm in Python and model the neural network in TensorFlow35, leveraging TensorFlow’s autodifferentiation to compute the gradient forces that drive training dynamics. An open-source implementation of our approach is available at Ref. 31.

Equation (1) serves as a generating function for sufficiently trained networks for finite β = 1/T. The key to obtaining sufficient training in the dynamical approach we use here is to maintain the auxiliary dynamics at a small but finite temperature, or simmer, so that the network systematically explores near-optimal configurations of weights and biases. These near-optimal configurations need not individually improve the network accuracy for test data because they belong to ensembles of networks, and various methods36,37 can be applied to the ensembles to extract more generalizable representations. We give general arguments in “Methods” that this supremacy of sufficient training over optimal training is a generic feature of the family of methods we introduce here.

To facilitate comparison between sufficient- and optimal training methods, we first deploy simmering to reduce overfitting in networks overfit by Adam. Figure 1a gives an example of this retrofitting procedure in the case of a standard curve fitting problem. Figure 1b shows a set of training and test data that are generated by adding noise to a sinusoidal signal (green line). With these training data, we train the parameters of a fully connected feedforward network using Adam. Figure 1a shows the evolution of the loss, with a clear divergence of the training and test loss during the Adam training stage. Figure 1b shows that the Adam-generated fit discernibly deviates from the true signal.

Optimization-based training produces discrepancies in performance on training vs. test data (c.f. light blue and dark blue MSE curves, panel (a)) that manifest in discrepancies between model fits and underlying relationships (c.f. dark blue and green curves, respectively, in panel (b)). We apply simmering to retrofit the overfit network by gradually increasing temperature (c.f. gray lines in panel (a)), which reduces overfitting (panel (c)) before producing an ensemble of networks that yield model predictions that are nearly indistinguishable from the underlying data distribution (c.f. dark magenta and green curves, panel (d)). Analogous applications of simmering can be employed to retrofit classification problems (panel (e)) and regression problems (panel (f)). Panel (e) shows prediction accuracy for image classification (MNIST), event classification (HIGGS), and species classification (IRIS). Panel f shows fit quality (squared residual, R2) for regression problems including the sinusoidal fit shown in detail in panels a-d, as well as single (S) and multivariate regression (M) of automotive mileage data (AUTO-MPG). In all cases, simmering reduces the overfitting produced by Adam (indicated by black arrows).

To correct this deviation, we apply simmering, taking the overfit, Adam-generated network as the initial condition. We introduce step-wise increases in temperature (gray line, Fig. 1a) from T = 0 to T = 0.05 (taking T to be measured in units of loss). Simmering generates ensembles of sufficiently trained networks at finite T which we then aggregate to construct a retrofitted representation of the underlying signal. Figure 1c shows that simmering has reduced the discrepancies that were present between the Adam-produced fit and the original signal. Figure 1d shows that a simmering-generated ensemble of sufficiently trained networks at T = 0.05 generates an aggregated fit that is virtually indistinguishable from the original sinusoidal signal.

We carried out an analogous retrofitting procedure on a set of similar problems. Figure 1e shows retrofitting results for classification problems, where, in all tested cases, applying simmering to retrofit overfit networks results in improved classification accuracy on test data. Figure 1f shows results for the application of simmering to retrofit regression problems, where simmering reduces the residual of the fit for test data compared with overfit, Adam-produced networks.

Ab initio sufficient training

Figure 1 demonstrated several applications of simmering to retrofit networks that are susceptible to overfitting by conventional, optimization-based training. These results raise the question of whether optimization-based training is necessary or whether ab initio implementations of sufficient training could avoid overfitting without any need for an optimized initial condition.

Figure 2 shows results from sufficiently trained neural networks in which simmering was deployed from the outset, without the need for optimization. Figure 2a shows results for classification, and Fig. 2b shows results for regression. It is important to note that because simmering yields an ensemble of networks, like other ensemble learning approaches37, it can be used to generate prediction uncertainty estimates that mitigate the artificial precision that arises from singular, optimization-generated solutions. These uncertainty estimates are shown in Fig. 2c–f. A key advantage of simmering is that, by exploring the maximum entropy distribution of weights and biases, it makes minimally biased assumptions about the training data error distribution and thus yields a minimally biased prediction uncertainty estimate.

Ensembles of models sampled at finite temperature yield smooth decision boundaries (white lines in panel (a)) and average predictions (dark magenta curve in panel (b)) that are not skewed by noisy training data (star, triangle and square black markers in panel (a), and round black markers in panel (b)). Test data (star, triangle and square gray markers in panel a, and round gray markers in panel (b)) are overlayed to show how the ensemble predictions (decision boundaries and average curve in panels (a, b), respectively) generalize to unseen data. The background in panel a is shaded using a weighted average of the ensemble votes for each class at each point in the feature space, showing regions of confident ensemble prediction (regions of bright purple, teal, or orange in panel (a)) vs. uncertain prediction (intermediate colored regions in panel (a)). Analogously, panel b shows the density of predicted curves (transparent magenta curves in panel b) around the ensemble average (dark magenta curve in panel (b)). For classification problems, panels c and d show the ensemble’s decision-making confidence at different points in the data feature space via the proportion of ensemble votes for each class (c.f. panels (c, d) correspond to pink markers labeled (c, d) on panel (a)). For regression problems, we can compare the distributions of sampled predictions with the ensemble average at different input values (c.f. pink solution distribution and dark magenta point on panels (e, f), sampled at two different inputs indicated in panel (b)) and assess how the data noise distribution affects predictions throughout the feature space. Ab initio sufficient training produces correspondingly sufficiently descriptive predictions alongside insight into the ensemble prediction process that is inaccessible with a singular, optimized model.

Employing a minimally biased model of training data error allows ab initio simmering to outperform other commonly used overfitting avoidance methods in two different learning tasks: image classification with a convolutional neural network and language translation with a Transformer. Figure 3 shows that, for both learning tasks, ab initio simmering achieves a higher test data accuracy than standard implementations of early stopping and dropout. Consistent with ensemble learning approaches, ab initio simmering outperforms singular optimized models treated with early stopping (rectangular maroon marker vs. round green markers in Figure 3). For CIFAR-10, given an equal training time of 20 epochs, ab initio simmering also outperforms two other ensemble learning methods: ensembled early stopping, an ensemble of independently optimized neural networks, and dropout, an ensemble of simultaneously-trained thinned neural networks. We find that simmering yields a test accuracy of over 82% in 20 epochs, whereas no other method exceeded 76% test accuracy on the same basis. In addition to yielding the most accurate ensemble predictions, we find that the simmering ensemble yields the most pronounced improvement in accuracy after ensemble aggregation, despite its ensemble members having similar accuracies to those of the early stopped ensemble. This difference in ensembling effectiveness indicates that the simmering ensemble, consisting of sufficient rather than optimal representations, uniquely ensures generalizable aggregate predictions. In Supplementary Information, we also present examples of prediction uncertainty analysis on CIFAR-10 images, analogous to Fig. 2c, d, that display the difference in ensemble prediction distribution between the three overfitting mitigation methods in Fig. 3a.

Simmering’s ensemble prediction (rectangular marker) achieves both the highest accuracy and the most significant ensembling improvement (rectangular marker vs. round markers), with the latter indicating that the advantage of simmering extends beyond just ensembling. In contrast, the early stopped ensemble accuracy (rectangular marker) does not exceed that of its ensemble members (round markers) for both training tasks. For the CIFAR-10 dataset, we employed the ConvNet architecture26, and all non-simmering cases were learned via stochastic gradient descent. The early stopping ensemble consists of 100 independently optimized early stopped models, with an average training duration of 14.56 epochs. Dropout and ab initio simmering each trained for 20 epochs, and the models corresponding to the last 2000 weight updates contributed to the simmering ensemble. We used dropout’s inference mode prediction as its ensemble prediction,38 and aggregated the early stopping and simmering ensembles via majority voting. For the translation task, we trained a reduced version (described in Supplementary Methods) of the Transformer architecture presented in Ref. 18 with a pre-trained BERT tokenizer,35 and assessed accuracy via teacher-forced token prediction accuracy. We fixed the learning rate for all cases, and trained non-simmering cases with the Adam optimizer.16 The early stopping ensemble consists of 10 independently trained models, with an average training time of 53.1 epochs, aggregated with majority voting. We optimized a model with dropout for 60 epochs and used its inference mode as its ensemble prediction. Accuracy convergence curves for both training tasks are shown in Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, and additional comparison implementation information is detailed in Supplementary Methods. The simmering ensemble exceeded the test accuracy of all other cases after only 21 training epochs, with a majority-voted ensemble prediction from 200 models sampled during the last epoch. For equivalent training time, ab initio simmering produces more accurate predictions than other ensembled overfitting mitigation techniques on the CIFAR-10 dataset. However, simmering can both accelerate training and exceed the accuracy of other overfitting techniques on a natural language processing task.

For the translation problem, Simmering outperforms all three overfitting mitigation methods with a shorter training time. Using fixed, equivalent learning rates, simmering exceeded the accuracy of both dropout and ensembled early stopping in a small fraction of the training time (21 epochs for simmering, versus 60 epochs for dropout and an average of 53.1 epochs for ensembled early stopping). As for CIFAR-10, Simmering had both the most accurate ensemble prediction and the most significant ensembling improvement.

These comparisons highlight the role of simmering’s distinct minimally-biased ensemble generation in efficiently producing generalizable predictions.

Discussion

The simmering method we presented above demonstrates that sufficient training consistently generates more generalizable networks than optimization-based training in classification, regression and natural language processing. To understand why, it is useful to characterize how neural network architecture and data noise affect the geometric structure of the loss landscape, and how optimization and simmering treat this geometric structure in pursuit of generalizable neural networks.

In “Methods”, we give a detailed argument that the neural network over-parameterization that drives both universal estimation and overfitting produces families of parameter combinations with near-equivalent or equivalent training loss. An optimization algorithm can effectively locate any one of the redundant minimized training loss parameter combinations. However, the training loss landscape geometry is defined by data that generically deviates from ground truth, so the optimized parameters will always lie some distance in parameter space from those that describe the underlying phenomenon.

This fact means that optimization-based training is doomed to fail (in terms of generalizability) any time it works (in terms of approaching optimality).

The inevitable failure of optimization in training generalizable networks in this setting is perhaps unexpected when compared to its success in conventional parameter estimation in, e.g., regression. However, the superficial similarity between conventional statistical model parameters and neural network parameters is misleading. Optimization is effective in conventional parameter estimation where models are constructed via ansatzes based on a priori knowledge about the form of the behaviors they aim to describe. This construction results in models with a small number of relevant parameters. In contrast, the architecture of neural networks derives the capacity to universally represent complex phenomena from its flexibility. Neural networks are constructed specifically to include more parameters than are expected to be needed to represent a given phenomenon, and the functional form of the network elements (e.g., activation functions) need not be related to the functional form of the underlying phenomenon. From another perspective, conventional models anticipate behavior, whereas neural networks generate emergent behaviors39. This difference between how conventional models and neural networks are parametrized and behave, i.e., anticipated versus emergent behavior, is instrumental in determining how the parameters ought to be estimated. Optimization performs poorly when training neural networks because training must contend with emergence.

Because, famously, “more is different”39, it should not be surprising that neural networks necessitate training approaches that differ from those of conventional statistics. The sufficient training approach we proposed here draws inspiration from approaches that have been successfully used to explore and reproduce emergent behaviors in a broad range of physical systems. Indeed, via our sufficient training implementation, we are able to identify features of emergent phenomena that parallel behaviors seen in other systems, particularly as encoded via a spectrum of modes in parameter space. From an information geometry perspective40,41,42, the families of near-equivalent training-loss networks exist along sloppy modes in the parameter space, which can be identified by the spectrum of an appropriate Fisher information metric40. Simmering exploits this geometric feature by parametrically reshaping the geometry of the loss landscape via a Pareto-Laplace transform30 controlled by a temperature parameter T = 1/β. In Methods, we show that T effectively reduces the distance in parameter space between optimal and near-optimal parameter sets. By reducing these distances, simmering explores parameters away from the minimal training-loss features formed by dataset idiosyncrasies. Past work43,44 has shown that powerful model reduction techniques can be constructed by leveraging the spectrum of the model’s Fisher information metric on parameter space. Simmering traverses the loss landscape along sloppy directions, collecting a minimally biased ensemble of models that can then be aggregated to average away the effect of sloppy directions and, in turn, the effect of over-parameterization. The degree of effective reduction is modulated by the same temperature parameter T. Therefore, one can start with an arbitrarily over-parameterized network and aggregate the ensemble collected during sufficient training to produce a sufficiently simple model that captures the phenomenon of interest without overspecification.

Methods

Sufficient training is a class of approaches that addresses the generalizability limitations of optimal training by systematically sampling neural network parameters with near-optimal loss. Sufficient training samples ensembles of near-optimal neural networks from the maximum entropy distribution32, which makes a minimally biased assumption about the deviation from ground truth present in the training data. This minimally biased ensemble can then be aggregated to produce generalizable predictions37. Starting from entropy maximization, we show how sufficient training generically uses the geometry of the loss landscape to deviate from optimal training loss during sampling, and how this deviation is controlled by the temperature T. For additional information about our notation, see Supplementary Methods.

A neural network’s training loss landscape is specified by its parameters x, training dataset \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}\), and loss function evaluated over the training data, \(L({{{\bf{x}}}},{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) where we will drop the vector notation on x hereafter. The neural network parameters x are distributed according to the probability density \(p(x| {{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) that maximizes the entropy

where β = 1/T is a Lagrange multiplier that enforces the moment constraint, and \(\lambda=\ln Z\) is a Lagrange multiplier that enforces the normalization of \(p(x| {{{\mathcal{D}}}})\). The \(p(x| {{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) value that maximizes Eq. (2) is

where \(Z(\beta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) is the partition function we are familiar with from statistical physics,

describing the partition of probabilities of states (parameter sets), weighted by their training loss value. We can thus also interpret Eq. (4) as the Pareto-Laplace transform30 of the loss, with β controlling the severity of penalization of high-loss parameter sets (recovering only the optimal solution in the limit β → ∞). Sampling states (parameter sets) from the canonical ensemble (Eq. (3)), or approximating the integral in Eq. (4), yields an ensemble of individually non-optimal parameter sets (corresponding to an ensemble of models) that can be used for uncertainty analysis and ensemble prediction.

The Pareto-Laplace filter provides one of many possible mechanisms for generating ensembles of models at non-minimal loss. However, the ensemble generated by this filter makes minimally biased assumptions about the noise distribution in the data, and is thus advantageous in settings where additional information is not available about the ground truth. When other information about the ground truth is available (e.g., the physics of the data), an extension of the current approach via physics-informed neural networks45 is likely to provide minimally biased sufficient-training methods as well.

Information geometric framing

To facilitate analysis of the partition function defined in Eq. (4), we define a set of collective variables \(\theta ({{{\bf{x}}}},{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) (for which we will drop the vector notation) that are a function of the neural network parameters and the training data. We can rewrite Eq. (4) in terms of the collective coordinates θ by first inserting the identity operator

and then rewriting Eq. (5) only in terms of θ

where

The effective free energy, \(F(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\), specifies the probability density \(p(\theta | {{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) of sampling a particular value of θ. Up to an overall constant,

and this probability can be computed via the mean-value theorem

where \(\Omega (\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) is the volume of the n-dimensional hypersurface of x along which \(\theta (x,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) is constant, \( < \cdot > \) denotes the mean on that surface (also called an ensemble average), and L is evaluated over the training dataset \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}\). Typically, we refer to \(\Omega (\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) it in terms of the entropy \(S(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) (reparameterized Eq. (2)) through the relation \(S=\ln \Omega\). Additionally, since θ is a set of collective variables, we can assume that \({e}^{-\beta L(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})}\) it is slowly varying over \(\Omega (\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) such that \( < {e}^{-\beta L} > \approx {e}^{-\beta < L > }\). Therefore, taking \(L(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) as the loss from the ensemble average in Eq. (9) and replacing T = 1/β, we get the relation for the free energy \(F(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\)

The most probable θ values (and thereby, the most probable neural network parameter combinations) are those that maximize \(p(\theta | {{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) (Eq. (8)) and thus minimize \(F(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) (Eq. (10)). In the T → 0 limit, we recover optimization, where minimizing \(F(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) minimizes the loss \(L(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\). However, at any finite temperature T > 0, the free energy-minimizing θ does not minimize \(L(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) (or \(L(x,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\)) because an entropic force \(-T{\partial }_{\theta }S(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) continuously drives θ away from minimal loss. This entropic drive away from minimal loss is generic because there are generally more ways for a system (e.g., a neural network) to have non-minimal loss than minimal loss (neural networks that do not exhibit this property could be trivially trained by randomly selecting weights and biases). This entropic force is key to the effectiveness of sufficient training – by incorporating finite-temperature dynamics into parameter updates, entropic forces systematically and continuously drive the learning trajectory away from loss-minimizing and subsequently overfit parameters.

The collective coordinate representation of F also allows us to more clearly see how β filters the loss landscape during sampling, via techniques from information geometry41. In practice, this filtration occurs automatically and generically.

To do this analysis, consider the Fisher information metric (FIM), which is defined as

For the present purposes, Eq. (11) can be computed in physics terms as a generalized susceptibility according to

where Z is defined in Eq. (6). The FIM has been interpreted in the work of Ref. 41 as an object that can be used to identify key order parameters that describe data–model relationships. Ref. 41 showed that the spectrum of gμν yielded sloppy modes that describe parameters that are loosely constrained by data, as well as stiff modes that are highly constrained. This mode classification provides a useful lens for interpreting the following analysis of the effect of temperature on the probability distribution of \(F(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) (and subsequently, the neural network parameters sampled) in the context of the Pareto-Laplace filter (Eqs. (4–10)).

Consider the parameter space near a free energy minimum such that ∂θF = 0. For simplicity, take the minimum at θ = 0 (which we can do without loss of generality by making a coordinate transformation). Taylor-expanding the FIM (Eq. (12)) near the minimum yields

and

For sufficiently large β (or low T = 1/β), these expressions can be integrated using a saddle point approximation, which yields

The FIM describes the relative proximity of θ to the free energy minimum θ = 0 in parameter space as a function of β = 1/T. The squared displacement ds2 between θ and θ = 0 is

where λj are the eigenvalues of the Hessian of \(F(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) that describe the curvature of F along different modes in parameter space. Distances (Eq. (16)) in a finite-temperature system diverge for small T, except along directions corresponding to sloppy modes for which the corresponding eigenvalues λj → 0. Simmering and other sufficient training implementations exploit this effect of temperature on distances in parameter space to systematically sample families of loss-equivalent networks located along these sloppy modes. In Supplementary Fig. 3, we provide a comparison of the learning trajectory of simmering with that of Adam for the noisy sine problem in Fig. 1a. This trajectory visualization shows that simmering identifies and travels along sloppy modes in parameter space, whereas Adam traverses the space perpendicular to loss function contour lines.

This information geometric framing presented here also motivates the effectiveness of both ab initio simmering and retrofitting at reducing overfitting in a neural network. The effect of T on the Hessian of \(F(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) (shown in Eq. (16)) is analogous to the effect of the regularization strength parameter, typically denoted λ, on the eigenvalues of the Hessian of the training loss when using L2-norm regularization.46 Using finite-temperature parameter sampling, both ab initio simmering and retrofitting rescale distances in parameter space in the same manner as L2-norm regularization, which has already been shown to reduce overfitting46.

Prediction uncertainty quantification with simmering

Since sufficient training identifies a distribution of parameter sets (and thus, a distribution of predictions) at a given β = 1/T, simmering and other implementations of sufficient training can be used for prediction uncertainty quantification.

In a generic supervised learning task, we aim to learn the ground truth based on a training dataset \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}={\{{z}_{i},{t}_{i}\}}_{i=1}^{M}\) comprised of a set of measured inputs {z1, z2, . . . , zM} and targets {t1, t2, . . . , tM}. We use a neural network to model our estimation of ground truth \(y({z}^{{\prime} };\overrightarrow{\theta })\) dependent on an unseen input \({z}^{{\prime} }\) and collective coordinates \(\theta ({{{\bf{x}}}},{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) (where we will drop the vector notation as in the information-geometric framing). The probability density of predicting a target value \({t}^{{\prime} }\) based on an unseen input \({z}^{{\prime} }\) is

According to Bayes’ rule, the posterior distribution \(p(\theta | {{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) in Eq. (17) is

where p(θ∣D) is the canonical distribution of θ at β = 1/T = 147. If we generalize the Bayesian posterior distribution equation for a general T, we recover the probability distribution from Eqs. (8, 9), with \(F(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) defined in Eq. (10). Thus, this prediction uncertainty quantification can be thought of as a generalization of that of Bayesian inference. Comparison between Eq. (8) and Eq. (18) identifies \(S(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) as the regularizer on the collective coordinates θ, and the temperature T as the regularization strength.

As in the information-geometric framing presented, we consider the region of the parameter space near a free energy minimum, and for convenience, this minimum occurs at θ = 0. We can expand \(F(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) near this minimum as

using Eq. (15) to relate \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}F(\theta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})}{\partial {\theta }_{\alpha }\partial {\theta }_{\gamma }}\) to \({g}_{\alpha \gamma }(\beta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) for large β (small T). Using Eqs. (8) and (19), we can rewrite \(p({t}^{{\prime} }| {z}^{{\prime} },{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) as

Eq. (20) shows that for a generic training dataset \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}\), simmering reduces distances in parameter space, allowing for sampling of near-optimal θ values that can elucidate features of \(p({t}^{{\prime} }| {z}^{{\prime} },\theta )\).

In the particular case where the training data targets have additive Gaussian noise \(\epsilon \sim {{{\mathcal{N}}}}(0,{\sigma }_{t}^{2})\), and we choose mean-squared error (MSE) as the loss function, the prediction uncertainty distribution is structurally similar to that of Bayesian inference with noise injection, but generalized to any β = 1/T. However, this equivalence between noise injection and sufficient training is a special case; in general, sufficient training does not assume a form for the noise distribution. Given this training data, target noise distribution, and loss function choice, \(p({t}^{{\prime} }| {z}^{{\prime} },\theta )\) becomes

Then, we can expand \(y({z}^{{\prime} };\theta )\) around the free energy-minimizing θ = 0 as

Using Eq. (21) and the Taylor expansion of \(y({z}^{{\prime} };\theta )\) in Eq. (22), we can evaluate Eq. (20) to be

where \({\sigma }^{2}={\sigma }_{t}^{2}+{\left.{g}_{\alpha \gamma }{(\beta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})}^{-1}\right\vert }_{\theta=0}{\left.\frac{\partial y({z}^{{\prime} };\theta )}{\partial {\theta }_{\alpha }}\right\vert }_{\theta=0}{\left.\frac{\partial y({z}^{{\prime} };\theta )}{\partial {\theta }_{\gamma }}\right\vert }_{\theta=0}\). In noise injection48,49, β is not a parameter, but is implicitly set to 147. However, in sufficient training, the variance equation generalizes to any positive non-zero inverse temperature β. The variance σ2 of the prediction uncertainty distribution has two terms: the variance introduced by uncertainty in data target measurements, \({\sigma }_{t}^{2}\), and a variance-like quantity defined by the sensitivity of the free energy and the model predictions to changes in θ. The overall effect of temperature on the second variance term is to reduce the FIM, gαγ, thereby increasing the second variance term contribution, but the exact way in which changing \({g}_{\alpha \gamma }(\beta,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) affects ∂θy is problem-dependent.

Parameter sampling mechanics

The probability density in Eq. (3) describes the distribution of states of a mechanical system in thermal equilibrium with a heat bath. There exist many thermostat algorithms in molecular dynamics28 that control the temperature of a system in order to simulate thermal equilibrium and sample from this distribution of states. Thus, if we model our neural network parameters as a system of particles, we can use existing constant-temperature simulation methods to generate canonical ensembles of parameters (corresponding to ensembles of models).

To employ molecular dynamics techniques in a neural network problem, we treat the neural network parameters as a system of one-dimensional particles in an interaction potential. The magnitude of each weight and bias defines the position of each particle in the physical system, and the loss function acts as the system potential. The negative gradient of the training loss function acts as a force on the system of particles that pushes them towards a minimum of the loss function. If we also define a conjugate momentum for each particle, we can integrate the equations of motion for the physical system and iteratively generate sets of weights and biases. In the absence of other forces, this integration would yield a set of weights and biases that predict with increasing accuracy on the training data, and as such is analogous to the result of any traditional momentum gradient-descent training algorithm. Generically, a thermostat algorithm adds another force on the particles of the system to simulate particle interactions with a heat bath (a thermal noise source).

Nosé-Hoover chain thermostat

A thermostat, in a molecular dynamics context, is an algorithm that controls the temperature of a physical system28. In simmering, we use a Nosé-Hoover chain (NHC) thermostat, but other thermostats can also be employed to achieve constant-temperature conditions in other implementations of sufficient training. The NHC thermostat samples from the canonical ensemble by introducing an interaction between the neural network parameters and a chain of massive virtual particles.28 The first particle in the chain exchanges energy with the system of neural network parameters, and the rest of the chain only interacts with their neighboring chain particles. Each virtual particle has a position and a conjugate momentum that are computed iteratively along with those of the system of real particles.

Given a set of N neural network parameters, we define a set of positions x = {xi}, associated momenta {pi} and masses {mi}. Using this set of quantities, we can model a system of one-dimensional particles in a potential defined by a loss function \(L(x,{{{\mathcal{D}}}})\) that depends on the neural network parameter positions (weights and biases) x and the training dataset \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}\). This physical system is also interacting with an NHC of length NNHC, where each chain particle also has its own mass Qk, position sk and momentum pk. Henceforth, the neural network parameters will be referred to as the real particles, to contrast with the virtual particles of the NHC.

The particles’ equations of motion are derived from the NHC Hamiltonian50,51. For simplicity of notation, we will henceforth set mi = 1, Qk = 1 ∀ i, k and describe the equations of motion in terms of the positions and velocities, rather than the positions and momenta. The real particles’ positions evolve according to33

where the i subscript denotes real particle quantities, and the sk subscript denotes a quantity affiliated with the kth virtual particle. The \({v}_{{s}_{1}}(t){v}_{i}(t)\) term from the NHC in Eq. (25) distinguishes simmering from gradient-based optimization. For example, in momentum gradient descent, Eq. (25) would have \({v}_{{s}_{1}}(t)=\,{\mbox{const}}\,\).52 In contrast, \({v}_{{s}_{1}}(t)\) in NHC dynamics can take on both positive and negative values over time.

The virtual particle dynamics are given by

with the accelerations for all particles \({a}_{i}(t),{a}_{{s}_{1}}(t),{a}_{{s}_{k}}(t)\) defined as

The acceleration of the real particles in Eq. (29) is proportional to the negative gradient of the loss with respect to the weights and biases in the neural network.

Given Eqs. (24–31), the trajectories of the real and virtual particles, and thus the evolution of neural network weights and biases over training time, can be determined via numerical integration. Further details on implementation and model architecture are given in Supplementary Methods.

Data availability

No data were generated in the course of this investigation.

Code availability

Code for implementing simmering is available open source at Ref. 31.

References

Hornik, K., Stinchcombe, M. & White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 2, 359–366 (1989).

Cybenko, G. Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function. Math. Control Signals Syst. 2, 303–314 (1989).

Lu, Z., Pu, H., Wang, F., Hu, Z. & Wang, L. The Expressive Power of Neural Networks: A View from the Width. In Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (eds Guyon et al.) Vol. 30 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017).

Guliyev, N. J. & Ismailov, V. E. On the approximation by single hidden-layer feedforward neural networks with fixed weights. Neural Netw. 98, 296–304 (2018).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Livni, R., Shalev-Shwartz, S. & Shamir, O. On the computational efficiency of training neural networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (eds Ghahramani, Z., Welling, M., Cortes, C., Lawrence, N. & Weinberger, K.Q.) Vol. 27 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2014).

Wei, C., Lee, J. D., Liu, Q. & Ma, T. Regularization Matters: Generalization and Optimization of Neural Nets v.s. their Induced Kernel. In Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (eds Wallach, H. et al.) Vol. 32 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2019).

Mehrabi, N., Morstatter, F., Saxena, N., Lerman, K. & Galstyan, A. A survey on bias and fairness in machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 54, 1–35 (2022).

Frenay, B. & Verleysen, M. Classification in the presence of label noise: a survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learning Syst. 25, 845–869 (2014).

Torralba, A. & Efros, A. A. Unbiased look at dataset bias. In CVPR 2011, 1521–1528 (IEEE, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2011).

Ruder, S. An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1609.04747 (2017).

Ghojogh, B. & Crowley, M. The Theory Behind Overfitting, Cross Validation, Regularization, Bagging, and Boosting: Tutorial. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1905.12787 (2023).

Hawkins, D. M. The problem of overfitting. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 44, 1–12 (2004).

Bilbao, I. & Bilbao, J. Overfitting problem and the over-training in the era of data: Particularly for artificial neural networks. In 2017 Eighth International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Information Systems (ICICIS), 173–177 (2017).

Ying, X. An overview of overfitting and its solutions. In J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1168, 022022 (IOP Publishing, 2019).

Kingma, D. P. & Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1609.04747 (2017).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 770–778 (Las Vegas, Nevada, United States, 2016).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (eds Guyon, I. et al.) Vol. 30 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2017).

Zhang, C., Bengio, S., Hardt, M., Recht, B. & Vinyals, O. Understanding deep learning requires rethinking generalization. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1611.03530 (2017).

Belkin, M., Hsu, D., Ma, S. & Mandal, S. Reconciling modern machine-learning practice and the classical bias–variance trade-off. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 15849–15854 (2019).

Srivastava, N., Hinton, G., Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 1929–1958 (2014).

Prechelt, L. Early Stopping - But When? In Goos, G., Hartmanis, J., Van Leeuwen, J., Orr, G. B. & Müller, K.-R. (eds.) Neural Networks: Tricks of the Trade, 1524, 55–69 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1998).

Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Mach Learn 24, 123–140 (1996).

Freund, Y. & Schapire, R. E. Experiments with a new boosting algorithm. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML’ 96, 148–156 (Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996).

Krizhevsky, A. & Hinton, G. Learning Multiple Layers of Features from Tiny Images. Technical Report, (University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada 2009).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. Vol. 25 (eds Pereira, F., Burges, C., Bottou, L. & Weinberger, K.) Vol. 25 (Curran Associates, Inc., 2012).

Ye, Q., Devandra, S., Matthieu, F., Sarguna, P. & Graham, N. When and why are pre-trained word embeddings useful for Neural Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies Vol. 2, 529–535 (Association for Computational Linguistics, New Orleans, Louisiana, United States, 2018).

Frenkel, D. & Smit, B.Understanding Molecular Simulation: From Algorithms to Applications. (Academic Press, San Diego, 1996).

Rumelhart, D. E., Hinton, G. E. & Williams, R. J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 323, 533–536 (1986).

Aliahmadi, H., Perez, R. & van Anders, G. Transforming design spaces using Pareto-Laplace filters. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.00631 (2024).

Babayan, I., Aliahmadi, H. & van Anders, G. Simmering: sufficient training of neural networks in Python. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17737731 (2025).

Jaynes, E. T. Information theory and statistical mechanics. Phys. Rev. 106, 620–630 (1957).

Jang, S. & Voth, G. A. Simple reversible molecular dynamics algorithms for Nosé–Hoover chain dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 107, 9514–9526 (1997).

Yamamoto, T. Comment on “Comment on ‘Simple reversible molecular dynamics algorithms for Nosé-Hoover chain dynamics’ ” [J. Chem. Phys. 110, 3623 (1999)]. J Chem Phys 124, 217101 (2006).

Martín Abadi et al. TensorFlow: large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous systems. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1603.04467 (2015).

Polikar, R. Ensemble Learning. In Zhang, C. & Ma, Y. (eds.) Ensemble Machine Learning, 1–34 (Springer New York, New York, NY, 2012).

Dietterich, T. G. Ensemble methods in machine learning. In International Workshop on Multiple Classifier Systems, 1–15 (Springer, 2000).

Hara, K., Saitoh, D. & Shouno, H. Analysis of dropout learning regarded as ensemble learning. In International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, 72–79 (Springer, 2016).

Anderson, P. W. More is different. Science 177, 393–396 (1972).

Transtrum, M. K., Machta, B. B. & Sethna, J. P. Geometry of nonlinear least squares with applications to sloppy models and optimization. Phys. Rev. E 83, 036701 (2011).

Quinn, K. N., Clement, C. B., De Bernardis, F., Niemack, M. D. & Sethna, J. P. Visualizing probabilistic models and data with intensive principal component analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 13762–13767 (2019).

Quinn, K. N., Abbott, M. C., Transtrum, M. K., Machta, B. B. & Sethna, J. P. Information geometry for multiparameter models: New perspectives on the origin of simplicity. Rep. Prog. Phys. 86, 035901 (2022).

Transtrum, M. K. Manifold boundaries give “gray-box” approximations of complex models. Preprint at arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1605.08705 (2016).

Mattingly, H. H., Transtrum, M. K., Abbott, M. C. & Machta, B. B. Maximizing the information learned from finite data selects a simple model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 1760–1765 (2018).

Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P. & Karniadakis, G. Physics-informed neural networks: a deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 378, 686–707 (2019).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning. Springer Series in Statistics (Springer New York, New York, NY, 2009).

Neal, R. M. Probabilistic inference using Markov chain Monte Carlo methods. Tech. Rep. CRGTR-TR-93-1, Department of Computer Science, (University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 1993).

Matsuoka, K. Noise injection into inputs in back-propagation learning. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 22, 436–440 (1992).

Wright, W. Bayesian approach to neural-network modeling with input uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 10, 1261–1270 (1999).

Martyna, G. J., Tuckerman, M. E., Tobias, D. J. & Klein, M. L. Explicit reversible integrators for extended systems dynamics. Mol. Phys. 87, 1117–1157 (1996).

Tuckerman, M., Berne, B. J. & Martyna, G. J. Reversible multiple time scale molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 97, 1990–2001 (1992).

França, G., Sulam, J., Robinson, D. & Vidal, R. Conformal symplectic and relativistic optimization. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 16916–16926 (2020).

Acknowledgments

We thank C.X. Du, A.A. Klishin, M. Spellings, and J. Wammes for discussions and P. Chitnelawong, K. Huneau, and M. Sheahan for collaboration at an early stage of this work. We acknowledge the support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) grants RGPIN-2019-05655 (GvA) and DGECR-2019-00469 (GvA). IB acknowledges the support of the NSERC USRA program, a Canada Graduate Scholarship, an Ontario Graduate Scholarship, and the Vector Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.B., H.A., and G.v.A. designed the research. I.B. contributed original code and data. I.B., H.A., and G.v.A. analyzed results. I.B., H.A., and G.v.A. wrote the paper. G.v.A. initiated and supervised research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Babayan, I., Aliahmadi, H. & van Anders, G. Sufficient is better than optimal for training neural networks. Nat Commun 17, 271 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66983-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66983-3