Abstract

Structural colours, which arise from nanostructures, are pervasive in nature and play a pivotal role in numerous modern applications. Traditional approaches usually deviate from the concept of Schrödinger’s pixels and thus have restricted performance in colour gamut and chiaroscuro presentation. Here, we harness the interactions between optical modes to achieve an unprecedented structural colour using SiO2-Si3N4 stacked metasurfaces. The mode interactions produce a high-reflection band formed by two Fano resonances with near-unity reflectance and sharp edges. The destructive interference between the tails of resonances and multiple reflections at the interfaces effectively suppresses the background reflection, creating an almost ideal stopband. Consequently, nearly perfect Schrödinger colours have been experimentally realized across almost the entire visible spectrum, setting a new colour gamut record of 1.06 times Rec.2020. By introducing local size deviation, higher-order diffraction emerges and the colour brightness has also been continuously adjusted for direct chiaroscuro presentation for the first time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the Diamond Perfection of Wisdom Sutra, the Buddha told Subhuti that “Everything with form is illusory; if all forms are viewed from their essence, the Tathagata will be perceived.”1 Colour is one prominent example. In appearance, it carries the main information and makes our world colourful. Essentially, different brilliant colours are closely related to light-matter interactions such as the inherent absorption, radiation, dispersion of materials, and wavefront changes in micro- or nano-structures2,3,4,5. The latter, also known as structural colour, was first discovered by Robert Hooke in 1665 and has been explored for centuries to explain the amazing colours of nature, e.g., birds, butterflies, beetles and even marbled berries6,7,8,9. With the advancement of nanofabrication technology, the colours of artificial nanostructures have been developed rapidly10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. Compared with its counterparts, nanostructures can produce bright and vivid colours without additional energy consumption, so it is very attractive and promising in many practical applications such as anti-counterfeiting, display and many other fields19,20,21,22,23,24.

From an application perspective, highly saturated red, green, and blue colours are crucial, depending on the reflectivity and colour gamut of the nanostructures. Over the past decade, great efforts have been made in this regard. By replacing the metallic nanostructures with loss-free dielectric ones, the brightness of the structural colour has been significantly improved25,26,27,28,29. Meanwhile, the structural colour gamut has been further expanded by using stacked dielectric multilayer nanostructures or refractive index matching layers30,31,32. Despite the progress, the state-of-the-art colour gamut is still well below the Rec.2020 standard (0.68- and 0.97-times Rec.2020)30,31. This is because the optical response of conventional nanostructure deviates from Erwin Schrödinger’s considerations33, i.e., residual reflection in the stopband and the slow transition between passband and stopband greatly degrade the colour presentation34,35. While polarization-crossed resonance can solve the background problem, their transitions are still not sharp enough and an additional polarizer is required36,37. Very recently, Dong et al. ingeniously tackled this problem and realized the first Schrödinger red pixel by utilizing quasi-bound states in the continuum and the absorption of Si at short wavelengths38. However, their approach exhibited limited performance in the green and blue spectral regions due to the inherent short-wavelength absorption of Si, which consequently restricted the achievable colour gamut of the architecture. Although bound states in the continuum (BIC) employing lossless dielectric materials can also achieve the requisite passband, the fundamental realization of Schrödinger colour across the entire visible spectrum remains elusive due to limitations imposed by the requirement for zero reflectance outside the passband29. At the same time, a mechanism to directly control colour brightness is still missing so far. Here, we report a universal mechanism for constructing Schrödinger colours across the entire visible spectrum using lossless dielectrics. Record-breaking colour gamut (106% of Rec.2020) and chiaroscuro presentation with direct brightness manipulation have been experimentally demonstrated.

Results

The working principle of all-dielectric Schrödinger colours

According to Schrödinger’s consideration, an ideal colour pixel should have the following three elements: near-unity reflectance in the desired spectral range, zero reflectance outside, and abrupt transitions between them33. In general, high reflection band and sharp edges can be obtained by adjusting the resonances in the nanostructure39,40. Broadband zero-reflection spectroscopy, however, remains a severe challenge, especially for the lossless dielectrics without the assistance of external polarizer41,42. Although anti-reflection coatings have been successfully achieved with transparent materials, their performance usually degrades when the refractive index increases43,44. Crucially, conventional designs, such as thin-layer stacks, graded-index nanostructures, and random nanostructures, are incompatible with the three requirements for high-brightness structural colours43,45.

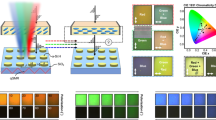

In this research, we combine thin layer stacking and patterned nanostructures into a metasurface to achieve the desired Schrödinger colour (Fig. 1a). In the vertical direction, four layers of ITO, SiO2, Si3N4 and SiO2 are stacked sequentially on a glass substrate. Their thicknesses are h1 = 13 nm, h2 = 54 nm, h3 = 256 nm, h4 = 110 nm, respectively. In the transverse plane, a hexagonal lattice array of dielectric nanopillars is patterned in top two SiO2 and Si3N4 layers. Each nanopillar has an elliptical-shaped cross-section with major and minor axis lengths of a and b. The lattice size is p = 381 nm. A gradient descent algorithm as integrated with FDTD simulation package to design and optimize the geometric parameters of the metasurfaces has been developed and used to optimize the geometry toward achieving the CIE plot rim at three corners. Two cost functions, the distance on the CIE diagram from the achieved structural colour coordinate to the target Schrödinger colour position of the CIE plot and the maximized “CIE x or y coordinate” are used in optimization. The target colours positions correspond to a monochromatic light source with a full width at half maximum of 20 nm at wavelengths of 460 nm, 520 nm, and 620 nm in CIE plot. These two cost functions toggle from one to the other to avoid the optimization to be stuck at a local minimum. The detailed optimization methods and procedures are described in Supplementary Fig. 1. One example with a = 350 nm and b = 220 nm is depicted in Fig. 1b. Moreover, the resonance wavelength can be tuned across the entire visible region by scaling the period and geometric dimensions with a scaling factor S, which is set to S = 1in the example provided. A high reflection band with near unity reflectance and a FWHM of 20 nm can be seen at ~515 nm. As the incident wavelength deviates from the high-reflection region, the reflectance drops sharply to below 1% and remains so over almost the entire visible spectrum (the response shown in Fig. 1b corresponds to the orange solid line in Fig. 1c, both representing simulation reflection of the same structure). All such phenomena match the requirements of Schrödinger pixel very well. The corresponding coordinates in the CIE 1931 chromaticity diagram are thus very close to the ideal Schrödinger green (inset in Fig. 1b, with details of the CIE coordinates for blue and red provided in Supplementary Fig. 2), and this is the first time that a Schrödinger pixel can be realized using transparent materials.

a Schematic diagram of the metasurface-based structural colours. Top inset shows the in-plane structures and size parameters. The tilt-view image of the nanopillar is shown in bottom inset. Dimensions within the plane are scaled proportionally with a parameter S to realize different colours. The thicknesses in all-simulation are fixed at h1 = 13 nm, h2 = 54 nm, h3 = 256 nm and h4 = 110 nm. b Numerically calculated x-polarized reflection spectrum of the metasurface. Inset shows the corresponding coordinates in CIE 1931 chromaticity diagram. An ideal Schrödinger pixel is also presented for a direct comparison. c Mode decomposition of the reflection spectrum. Two resonances at 508 nm and 520 nm and a weak uncoupled field caused by the interfaces are involved. d The relative phase differences between two modes and the uncoupled fields. e–h shows the vectorial sum of decomposed fields at 450 nm, 508 nm, 520 nm, and 600 nm, respectively. Insets in (f) and (g) are the corresponding Fano shapes induced by the interaction between two modes.

To understand the formation of the nearly ideal Schrödinger colour, we decomposed the resonances in Fig. 1b and explored their respective contributions. In principle, the reflection spectra contain two parts, i.e., the radiation of the resonances and the reflection at interfaces. The latter one is strongly dependent on the thickness of each layer and their effective refractive indices (different from a uniform film). To produce high-purity colour, it is essential to suppress the reflection at non-resonant wavelengths. The decomposed spectra are plot in Fig. 1c. Two eigenmodes at 508 nm and 520 nm of the nanostructure in the visible region are crucial for constructing high reflection bands (see field distributions in Supplementary Fig. 3). These resonant states are leaky eigenmodes (guided-mode resonances) supported by the high-index Si₃N₄ layer and periodically coupled to free space. These discrete modes possess complex eigenfrequencies and finite radiative lifetimes, producing Fano-type interference with the non-resonant background. The excitation of a given resonant state depends on polarization: it can only be excited when the polarization of the incident light is non-orthogonal to the time-reversed radiation polarization of that state. Such resonant and polarization-selective behaviours are well established in dielectric nanoresonators and guided-mode metasurfaces25,26,27,28,29,39,40,41,46,47. Returning to the spectral construction, the constructed reflection spectrum (dashed green line in Fig. 1c) fits the two reflection peaks well, but the non-resonant reflectance is still much higher than the numerical simulation (orange solid line) within the spectral range from 475 nm to 625 nm, strongly spoiling the colour performances. This is because the contribution of multiple reflections of light at the interface, that is not coupled to resonances, has not been included by two eigenmodes. The solid blue line in Fig. 1c shows the reflection spectrum of the uncoupled field obtained by mode decomposition. Similar to the eigenmodes, it also has much higher reflectance than the simulation at non-resonant wavelengths. Consequently, the phases of different components play a vital role here. As depicted in Fig. 1d, the phase difference between the two eigenmodes and the uncoupled field ranges from 90 to 270 degrees over almost the entire visible region. Then the destructive interference between them effectively suppresses the reflection outside the high reflection band. Such interference can be clearly seen from the vectorial superposition in Fig. 1e, h, where the amplitude of the total reflection is greatly reduced to ~ 6.6 and 3.5 by the destructive interference between mode-1 and uncoupled fields. In the high reflection band, the interaction mainly occurs between two eigenmodes and produces total field more than an order of magnitude higher (Fig. 1f, g). Such interaction forms two Fano resonances in opposite directions, resulting in high reflectance and sharp edges simultaneously (insets in Fig. 1f, g). To further elucidate the spatial origin of the radiated fields presented in Fig. 1e–h, we note that the electric field components are derived from the backward radiation of both the resonant and uncoupled modes, evaluated on a reference plane (S₁) situated above the metasurface (see Supplementary Note 18 for details). The radiated field of the extended state is calculated by spatially integrating the electric field over S₁, \({{{\bf{E}}}}^{\left({\mbox{rad}}\right)}\left(\omega \right)=\frac{1}{{S}_{1}}{\int }_{{S}_{1}}{{\bf{E}}}\left(\vec{r};\omega \right){d}^{2}{{\bf{r}}}\), and so are the resonant states’ radiation field \({{{\bf{E}}}}^{\left({\mbox{rad}}\right)}\left(\omega \right)\) and the uncoupled field’s radiation \({{{\bf{E}}}}_{0}^{\left({\mbox{rad}}\right)}\left(\omega \right)\). Under x‑polarized illumination, only resonant states emitting x‑polarized radiation are excited. Then only the x‑component of the backward field, \({E}_{x}^{\left({\mbox{rad}}\right)}\left(\omega \right)={{\sum }_{n}E}_{\left(n,x\right)}^{\left({\mbox{rad}}\right)}\left(\omega \right)+{E}_{\left(0,{x}\right)}^{\left({\mbox{rad}}\right)}\left(\omega \right)\), is considered.

With the above analysis, we know that the coupling between different modes and their interaction with multiple reflections at the interfaces build the Schrödinger colour. Since no material absorption is used to suppress the stopband reflectance in Fig. 1, the mechanism of Schrödinger colour can be generalized and extended to other colours as well. By increasing the scaling parameter S from 0.8 to 1.2, the reflection spectra are optimized. The numerically calculated reflection spectra with x-polarization are summarized in Fig. 2a. To meet the needs of multi-colour monolithic manufacturing, here the thicknesses of layers in all samples are the same as Fig. 1. Although the wavelength of the high reflection band increases with the scaling parameter, near-zero reflection bands and sharp edges have been produced in all metasurfaces. As a consequence, our mechanism can achieve nearly ideal Schrödinger pixels in almost the entire visible light region. The spectra of different samples are plotted as dots in CIE1931 chromaticity diagram (Fig. 2b). The colour performances of our metasurfaces have been improved close to the boundary. For a direct comparison, Rec.2020, a standard for ultrahigh-definition television (UHDTV) since 2012 has also been plotted as dashed triangle in Fig. 2b. The colour gamut of our Schrödinger pixels is almost 120% of Rec. 2020, which is a new record of structural colour.

a The simulated reflection spectra of different metasurfaces. The scaling parameter of from top to bottom are S = 0.80, 0.85, 0.95, 1.00, 1.05, 1.10, and 1.20. All the other parameters are the same Fig. 1. b The corresponding colour coordinates in CIE 1931 chromaticity diagram. The dashed triangle represents Rec. 2020 for UHDTV. c Unit cell of metasurface with size deviation Δr introduced to the central nanopillar. d Numerically calculated reflection spectra as a function of Δr.

Considering the elliptical-shaped cross-section of the nanopillar, the reflection spectra and the corresponding structural colours exhibit polarization dependence. For y-polarized incident light, the reflection spectrum shows a redshift of the primary resonance. At the same time, the emergence of an additional peak at shorter wavelengths (as depicted in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4) will reduces the colour saturation compared to the x-polarized case, though relatively bright structural colours are still achievable. Such polarization dependence can be utilized to realize versatile colours in one metasurface, which is essential for many practical applications such as sensing36,48. One example is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 5. For x-polarized incident light, the colour can be continuously and directly tuned from 514 nm to 568 nm by rotating the axis of each meta-atom without the aid of an external polarizer.

More intriguingly, the proposed structural colours also hold the potential for chiaroscuro presentation, which is another challenge for colour nanoimprinting. Such a function is typically realized by cross-polarized resonances, but with the assistance of an external polarizer. Our Schrödinger colour can be completely different and provide a way to directly manipulate the colour brightness. As depicted in Fig. 2c, a size deviation parameter Δr can be locally introduced to one nanopillar. In this case, the hexagonal lattice changes to a rectangular supercell and higher-order diffraction thus occurs (see Supplementary Note 7 for details). Such diffractions take away some of the energy and reduce the brightness of the structural colours. Figure 2d summarizes the reflection spectra of our metasurface as a function of size perturbation when a single, global Δr is applied across the entire lattice. With the increase of Δr from 0 to 100 nm, the reflectance gradually decreases and nearly vanishes at Δr~100 nm. Meanwhile, the corresponding resonant wavelengths experience a slight blueshift relative to their initial positions due to the reduction in effective refractive index. Nevertheless, this shift can be readily compensated for by adjusting parameters such as the S or the minor axis b, thereby maintaining the resonance wavelength at the desired position. This controllable adjustment of brightness with stable hue well satisfies the requirements for direct chiaroscuro presentation (As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 18).

Experimental demonstration of all-dielectric Schrödinger colours

The designed metasurfaces have been experimentally fabricated on a 13 nm ITO-coated glass substrate with a combined process of plasma enhanced chemical vapour deposition (PECVD), electron-beam (E-beam) evaporation, E-beam lithography, lift-off and inductively coupled plasma reactive ion etching (ICP-RIE, see details in Methods and Supplementary Fig. 8). Left column of Fig. 3a shows the top-view scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the metasurfaces with different scaling parameters. The hexagonal lattice, elliptical atom, and the detailed size parameters follow the numerical design very well. For metasurfaces made of stacked different materials, a key technical challenge is to achieve vertical and smooth sidewalls. In our research, a two-step dry etching recipe has been developed. The top SiO2 layer is etched with a mixture of CHF3 (25 sccm) and Ar (30 sccm). This is a physical etching-dominated process that can effectively minimize undercutting under the mask. Then the Si3N4 layer is chemically etched with O2 (4 sccm) and CHF3 (37 sccm). During this process, a fluorocarbon polymer film is produced to passivate and protect the sidewalls of SiO2 and Si3N4. Meanwhile, the etching depth can be precisely controlled by the etching speed of 3 nm/s. The tilt-view SEM images of the metasurfaces are shown as right column of Fig. 3a. It is easy to see that the sidewalls are straight and smooth with an angle of 86o. No obvious undercutting and roughness can be observed. This is completely different from conventional stacked metasurfaces30 and thus high-performance structural colours can be expected.

a Top-view and tile-view SEM images of SiO2-Si3N4 stacked metasurfaces with scaling parameters from top to bottom of S = 0.80, 0.85, 0.95, 1.00, 1.05, 1.10, and 1.20. All the other parameters are the same Fig. 1. b Experimentally recorded reflection spectra of the metasurfaces with different Schrödinger pixels. Insets are their corresponding bright-field microscope images. c Locations of all experimentally recorded Schrödinger pixels in CIE 1931 chromaticity diagram. Rec. 2020 for UHDTV is also plotted for a direct comparison. d Experimentally recorded spectra of red (top), green (middle), and blue (bottom) Schrödinger pixels as a function of size deviation parameter Δr. e Th experimentally recorded structural colours under a bright field microscope. Here 117 samples with different scaling parameters and size deviation parameters are fabricated to show different colour (horizontal axis) and brightness (vertical axis). The colour images have been cropped and arranged on a black background.

The characteristics of the metasurfaces are optically characterized with a home-built brightfield optical microscope (see Methods). With an x-polarized incident light, the reflection spectra have been directly recorded without using an additional polarizer (Fig. 3b). Some samples in Fig. 3b exhibit only a single resonance mode, which we attribute to minor fabrication deviations. Nevertheless, this does not compromise the colour saturation, as confirmed by the results shown in Supplementary Fig. 15. For the case of S = 1, two reflection peaks can be clearly seen at 504.21 nm and 512.79 nm, respectively (Panel-IV in Fig. 3b). The maximal reflectance is as high as 85% and the FWHM is only 16.25 nm. Most importantly, the background reflectance at undesired wavelengths remains below 1% from 418.25 nm to even 800 nm (Supplementary Fig. 9). All these experimental observations are consistent with the numerical design very well. Slight difference in peak wavelengths arises from size deviations in nanofabrication. As a result, a bright and vivid green colour can be directly obtained in the bright field microscope image (inset). The corresponding location is marked as a star in CIE1931 chromaticity diagram (Fig. 3c), which is beyond the UHDTV triangle and very close to the ideal Schrödinger green colour. As a consequence, we know that high performance structural colour has been experimentally achieved using transparent materials.

Then the performances of all metasurfaces with different scaling parameters have been characterized. With the increase of scaling parameter from 0.8 to 1.2, the resonant wavelength continuously shifts from 462.94 nm to 630.18 nm, covering the colours from blue to red very well (Fig. 3b). The maximal reflectance gradually increases from 79.36% at blue colour to 89.20% at red colour. And the FWHM of the high-reflection band in all metasurfaces varies between 8.89 nm and 16.27 nm. The averaged FWHM and peak reflectance are thus around 83% and 13.39 nm, respectively. Meanwhile, we find that the reflectance at non-resonant wavelengths of all metasurfaces are well below 1% in almost entire visible spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 9). Thus, nearly ideal different Schrödinger colours have been experimentally realized at many different wavelengths (insets in Fig. 3b).

Figure 3c summarizes the colour performances of 18 samples in CIE1931 chromaticity diagram. All colours are distributed near the boundaries of the CIE1931 map, and the blue and green are well beyond the Rec.2020 area. As consequence, the colour gamut of our Schrödinger colours is about 106% of Rec. 2020. This is the first time that artificial structural colour has surpassed the performance of UHDTV in experiment. The FWHM, average reflectance, and colour gamut of all bright-field structural colours in literatures are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 10 for a direct comparison with our experimental results. It is apparent that our Schrödinger colour has obvious advantages in these indicators. Based on a similar process, we have fabricated 126 SiO2-Si3N4 stacked metasurfaces with smaller intervals of scaling parameters and experimentally recorded their colour performances. The corresponding results are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 11. Vivid rainbow colours are directly presented, indicating the potentials of stacked metasurfaces in full-colour printing. With all the above results, we can now confirm that our mode interaction mechanism can enhance the reflection of the designed wavelength and suppress the reflection of the non-resonant wavelength, thus producing nearly ideal Schrödinger colours in almost the entire visible spectrum. The corresponding reflection spectra and colour performances in CIE1931 chromaticity diagram of all above samples with y-polarized incident light were also recorded and plotted in Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12. All the experimental results are perfectly consistent with the simulation too.

Similar to the numerical simulation, the potential of our structural colours in direct chiaroscuro presentation has also been investigated. Figure 3d shows red, green, and blue pixels with different size deviation parameters integrated across entire lattices. As Δr increases, the reflectance decreases by more than an order of magnitude, while the resonant wavelengths show a slight blueshift. This shift can be readily compensated by adjusting parameters such as the S or the minor axis b, thereby preserving a consistent hue. This possibility has been experimentally verified by fabricating 117 samples with different scaling parameters S and size deviation parameters Δr. The recorded colours are summarized in Fig. 3e. We can see that S and Δr determine the colour and its brightness respectively. All colours can be adjusted gradually from bright to near-dark by tuning Δr. We emphasize that no additional polarizer is employed in our scheme. Although the reflectance cannot be reduced to absolute zero—unlike in polarization-based extinction methods—the measured reflectance of our optimized low-reflection state is suppressed below 3% at the resonance and below 1% in off-resonant bands (see Supplementary Fig. 17 for details), which is sufficiently dark for high-contrast display applications. The key advantage of our approach lies in its direct control of brightness via structural tuning, which significantly simplifies the device architecture and improves optical efficiency compared to polarizer-dependent systems.

High-performance colour printings

Compared with Ref. 38, the nearly ideal structural colours arise from the mode interactions instead of the BIC. As a consequence, it doesn’t require an infinite size in at least one dimension and thus is applicable to small pixels. To verify this possibility, we have fabricated a series of metasurfaces with different pixel sizes and characterized their colour properties. All the results are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 13. We can see that the designed structural colours and the corresponding reflection spectra can still be well preserved with the reduction of pixel size from 8 μm of 3 μm. This information, associated with the colour and brightness control, enables the generation of high-quality colourful images with the near ideal Schrödinger pixels.

To demonstrate high-resolution colour printing, we designed a monochrome sketch (the original design is shown in Supplementary Fig. 21a) as a grayscale pattern. In experiment, structural colours with 70 precisely controlled brightness steps (with size deviations) have been realized to mimick the intensity variations (see bottom insets in Fig. 4(a)) and construct the designed Sketch. The total size of the sample is 1 mm × 1 mm, containing ~ 7,864,320 nanopillars. Figure 4a shows the bright-field microscope image of the sample under the illumination of a white-light source. While no additional polarizer is used, we can see that the designed image has been successfully reproduced by our metasurface pixels. The enlarged figure of the sample is measured by a 100× objective lens and shown as top-inset in Fig. 4a. Both the brightness variation and the detailed features match the design very well, clearly demonstrating the capability of our metasurface colour pixel in direct chiaroscuro presentation.

a Bright-field microscope image of the Sketch composed of metasurfaces with different pixel sizes and structural parameters. Bottom insets show the SEM images of supercell and the corresponding structural colours. The scale bar is 500 nm. Top inset is the high-resolution image recorded by a 100 × objective lens. b Bright-field microscope of CAT image composed of stacked metasurfaces with variations in both colour and brightness. Insets show the detailed information.

By simultaneously tuning the scaling parameter and size deviation, the Si3N4-SiO2 stacked metasurface can also be employed to construct a colourful image with fine brightness differences. For the case of Schrödinger colours, we designed an image of CAT (the original design is provided in Supplementary Fig. 21b), and constructed it with ~ 80,771,452 Si3N4-SiO2 stacked nanopillars. Under the illumination of white-light source, the bright-field image of the sample is almost identical to the design (Fig. 4b). With a 100× objective lens, the detailed variations in both colours and brightness of the enlarged starry night have been reproduced too (insets in Fig. 4b). Since no extra polarizer has been utilized in our experiments, we can confirm now that this new approach can be an all-in-one solution for high-performance colour nanoprinting.

Discussion

In summary, we have proposed and experimentally demonstrated a new mechanism to construct high quality Schrödinger colours using transparent materials. We reveal that mode interactions in stacked nanostructures can effectively enhance the reflectance of resonant modes and suppress reflections in non-resonant spectral regions, allowing nearly all Schrödinger colour requirements to be satisfied. This mechanism does not require the use of material absorption and the BIC resonance, and can be generalized to the entire visible light spectrum as well as small pixel sizes. By introducing a size deviation to break the in-plane symmetry of the lattice, we controllably excite higher-order diffraction, which redistributes optical energy from the 0th order to other diffraction channels, thereby enabling direct tuning of the colour brightness. In addition, a CMOS-compatible nanofabrication process for high-quality SiO2-Si3N4 stacked metasurfaces has been developed and optimized. As a consequence, we have experimentally fabricated high-quality stacked metasurfaces with simultaneous improvements in colour gamut, average reflectance, and FWHM to record-breaking values. This research presents a key step to improve the characteristics of structural colours and advance their applications in high-performance optical displays.

Methods

Numerical simulation

The simulations of the reflectance spectrum for the metasurface is based on periodic boundary conditions under plane wave illumination. The simulation the commercial finite element method (FEM) software COMSOL Multiphysics and Lumerical FDTD Solutions for simulation. Perfectly matched layers are applied in the transmission and reflection directions to absorb the outgoing waves. The refractive index of all materials is taken from the experimental result by ellipsometer. A Python code is used to calculate the xy coordinates, which are plotted in the International Commission on Illumination (CIE) 1931 chromaticity diagram (Supplementary Fig. 14). The resonance contributions are analyzed with the mode decomposition (see Supplementary Note 4).

Sample fabrication

The SiO2-Si3N4 stacked metasurfaces are fabricated with a combined process of plasma-enhanced chemical vapour deposition (PECVD), electron-beam (E-beam) evaporation, E-beam lithography, lift-off and inductively coupled plasma reactive ion etching (ICP-RIE). Briefly, amorphous multi-layer SiO2 /Si3N4/ SiO2 films were grown onto the 13 nm ITO-coated glass using the PECVD method. After that, 120-nm-thick PMMA A2 was spin-coated onto the sample surface, followed by EBL and lift-off processes. The thicknesses of ITO, SiO2 Si3N4, and SiO2 are measured by a spectroscopic ellipsometer and the fitting result is 13 nm, 54 nm, 256 nm and 110 nm. The Cr pattern after lift-off is used as hard mask for SiO2 and Si3N4 etching. A new etching method is developed to etch SiO2 and Si3N4 to ensure that the nanostructures have a very good verticality. The detailed fabrication process is described in Supplementary Note 8 with corresponding process parameters.

Optical measurement

The metasurfaces are placed onto an optical microscope (ZEISS, Axio Scope AI) stage associated with a home-made optical setup to control the polarization. The reflection spectrum is recorded with a spectrometer under the ×5 objective lens (NA = 0.12).

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Code availability

The code that supports the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Pine, R. The diamond sutra: The perfection of wisdom (Counterpoint, 2001).

Kumar, K. et al. Printing colour at the optical diffraction limit. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 557–561 (2012).

Ee, H.-S., Kang, J.-H., Brongersma, M. L. & Seo, M.-K. Shape-dependent light scattering properties of subwavelength silicon nanoblocks. Nano Lett. 15, 1759–1765 (2015).

Sun, S. et al. All-dielectric full-color printing with tio2 metasurfaces. ACS Nano 11, 4445–4452 (2017).

Li, K. et al. Facile full-color printing with a single transparent ink. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh1992 (2021).

Stavenga, D. G., Leertouwer, H. L. & Wilts, B. D. Coloration principles of nymphaline butterflies – thin films, melanin, ommochromes and wing scale stacking. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 2171–2180 (2014).

Kinoshita, S., Yoshioka, S. & Miyazaki, J. Physics of structural colors. Rep. Prog. Phys. 71, 076401 (2008).

Parnell, A. J. et al. Spatially modulated structural colour in bird feathers. Sci. Rep. 5, 18317 (2015).

Vignolini, S. et al. Pointillist structural color in pollia fruit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109, 15712–15715 (2012).

Tan, S. J. et al. Plasmonic color palettes for photorealistic printing with aluminum nanostructures. Nano Lett. 14, 4023–4029 (2014).

Dong, Z. et al. Printing beyond srgb color gamut by mimicking silicon nanostructures in free-space. Nano Lett. 17, 7620–7628 (2017).

Wiecha, P. R. et al. Evolutionary multi-objective optimization of colour pixels based on dielectric nanoantennas. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 163–169 (2017).

Daqiqeh Rezaei, S. et al. Nanophotonic structural colors. ACS Photonics 8, 18–33 (2021).

Duan, X., Kamin, S. & Liu, N. Dynamic plasmonic colour display. Nat. Commun. 8, 14606 (2017).

Xu, T., Wu, Y.-K., Luo, X. & Guo, L. J. Plasmonic nanoresonators for high-resolution colour filtering and spectral imaging. Nat. Commun. 1, 59 (2010).

Shaltout, A. M., Kim, J., Boltasseva, A., Shalaev, V. M. & Kildishev, A. V. Ultrathin and multicolour optical cavities with embedded metasurfaces. Nat. Commun. 9, 2673 (2018).

Hentschel, M. et al. Dielectric mie voids: Confining light in air. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 3 (2023).

Zhuang, Z.-P. et al. Overcoming intrinsic dispersion locking for achieving spatio-spectral selectivity with misaligned bilayer metagratings. eLight 5, 13 (2025).

Leitis, A. et al. Angle-multiplexed all-dielectric metasurfaces for broadband molecular fingerprint retrieval. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw2871 (2019).

Joo, W.-J. et al. Metasurface-driven OLED displays beyond 10,000 pixels per inch. Science 370, 459–463 (2020).

Meng, J., Cadusch, J. J. & Crozier, K. B. Detector-only spectrometer based on structurally colored silicon nanowires and a reconstruction algorithm. Nano Lett. 20, 320–328 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Coloured vortex beams with incoherent white light illumination. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 264–272 (2023).

Li, R. et al. Dynamic high-capacity structural-color encryption via inkjet printing and image recognition. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2404706 (2024).

Chen, B. et al. Sic diffractive waveguides for augmented reality: Single-layer, full-color, rainbow-artifact-free display with vision correction. eLight 5, 21 (2025).

Evlyukhin, A. B. et al. Demonstration of magnetic dipole resonances of dielectric nanospheres in the visible region. Nano Lett. 12, 3749–3755 (2012).

Cao, L., Fan, P., Barnard, E. S., Brown, A. M. & Brongersma, M. L. Tuning the color of silicon nanostructures. Nano Lett. 10, 2649–2654 (2010).

Zhang, C. et al. Stretchable all-dielectric metasurfaces with polarization-insensitive and full-spectrum response. ACS Nano 14, 1418–1426 (2020).

Proust, J., Bedu, F., Gallas, B., Ozerov, I. & Bonod, N. All-dielectric colored metasurfaces with silicon mie resonators. ACS Nano 10, 7761–7767 (2016).

Zheng, H. et al. All-dielectric structural coloration empowered by bound states in the continuum. Nanophotonics 13, 4327–4335 (2024).

Yang, B. et al. Ultrahighly saturated structural colors enhanced by multipolar-modulated metasurfaces. Nano Lett. 19, 4221–4228 (2019).

Yang, W. et al. All-dielectric metasurface for high-performance structural color. Nat. Commun. 11, 1864 (2020).

Yan, Z. et al. Floating solid-state thin films with dynamic structural colour. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 795–801 (2021).

Schrödinger, E. Theorie der pigmente von größter leuchtkraft. Ann. Phys. 367, 603–622 (1920).

Lim, K. T. P., Liu, H., Liu, Y. & Yang, J. K. W. Holographic colour prints for enhanced optical security by combined phase and amplitude control. Nat. Commun. 10, 25 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. Optical fireworks based on multifocal three-dimensional color prints. ACS Nano 15, 10185–10193 (2021).

Song, M. et al. Versatile full-colour nanopainting enabled by a pixelated plasmonic metasurface. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 71–78 (2023).

Bao, Y. et al. Full-colour nanoprint-hologram synchronous metasurface with arbitrary hue-saturation-brightness control. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 95 (2019).

Dong, Z. et al. Schrödinger’s red pixel by quasi-bound-states-in-the-continuum. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm4512 (2022).

Tittl, A. et al. Imaging-based molecular barcoding with pixelated dielectric metasurfaces. Science 360, 1105–1109 (2018).

Jin, J. et al. Topologically enabled ultrahigh-q guided resonances robust to out-of-plane scattering. Nature 574, 501–504 (2019).

Jung, C. et al. Near-zero reflection of all-dielectric structural coloration enabling polarization-sensitive optical encryption with enhanced switchability. Nanophotonics 10, 919–926 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Slanted TiO2 metagratings for large-angle, high-efficiency anomalous refraction in the visible. Laser Photonics Rev. 17, 2200712 (2023).

Spinelli, P., Verschuuren, M. A. & Polman, A. Broadband omnidirectional antireflection coating based on subwavelength surface Mie resonators. Nat. Commun. 3, 692 (2012).

Kim, K.-H. & Park, Q. H. Perfect anti-reflection from first principles. Sci. Rep. 3, 1062 (2013).

Hiller, J. A., Mendelsohn, J. D. & Rubner, M. F. Reversibly erasable nanoporous anti-reflection coatings from polyelectrolyte multilayers. Nat. Mater. 1, 59–63 (2002).

Fan, S. & Joannopoulos, J. D. Analysis of guided resonances in photonic crystal slabs. Phys. Rev. B 65, 235112 (2002).

Wang, S. S. & Magnusson, R. Theory and applications of guided-mode resonance filters. Appl. Opt. 32, 2606–2613 (1993).

Badloe, T. et al. Liquid crystal-powered mie resonators for electrically tunable photorealistic color gradients and dark blacks. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 118 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant nos. 2021YFA1400802 and 2022YFA1404700), National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 62125501,12025402, 12334016, 62335005 12261131500, and 92250302), New Cornerstone Science Foundation through XPLORER PRIZE, Shenzhen Fundamental Research Project (grant nos. JCYJ20220818102218040, JCYJ20241202123729038, and JCYJ20241202123719025), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. 2022FRFK01013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.X. and Q.S. conceived the idea and supervised the research. Y.L., C.Z., Q.L., Y.Z., J.H., and X.S. fabricated the metasurfaces. Y.L. and K.D. performed the optical characterizations. Y.L., J.Y. and Z.L. did the numerical calculations. Y.L., K.L. and C.Q. did the data analysis. All the authors discussed the contents and prepared the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yeong Hwan Ko, Diana C. Skigin, and Ting Xu for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Yin, J., Zhang, C. et al. All-dielectric Schrödinger colours across the visible spectrum. Nat Commun 17, 275 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66990-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-66990-4