Abstract

Highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOM) play a crucial role in the formation and growth of atmospheric particles, thereby influencing air quality and climate. A comprehensive understanding of HOM formation, particularly an accurate quantification of their yields, is essential to constrain the climate and health impacts of aerosols. Previous studies often reported constant HOM yields as averages, overlooking nuanced changes. Here we revisit several experimental datasets and demonstrate that HOM yields from single volatile organic compounds (VOCs) can vary by more than a factor of 3, depending on numerous parameters affecting peroxy radicals (RO2) autoxidation. Additionally, we propose a concept of RO2 oxidation fraction, which provides a unified explanation for variations in the HOM yields. Our findings indicate that applying the laboratory-derived HOM yields to the interpretation of ambient data may lead to substantial biases, especially when VOC and oxidant concentrations in the laboratory were higher than those in the real atmosphere.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

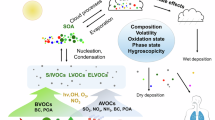

Atmospheric aerosols degrade air quality1, threaten human health2,3,4, and influence climate5. Highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOM), first identified as low-volatility products of monoterpene oxidation in a boreal forest6, are now known to form from a wide variety of precursors, including isoprene7,8,9, sesquiterpenes10,11, aromatics12,13,14 and anthropogenic alkenes15,16. These compounds play a pivotal role in the formation of aerosol particles. HOM can participate in particle nucleation17,18,19,20, dominate particle growth21,22,23, and drive the formation of secondary organic aerosol (SOA)24,25,26, a major component of global fine particles27,28,29. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of HOM production, especially their yields and volatilities, is crucial for an accurate evaluation of the budget of global fine particles.

The atmospheric discovery of HOM6, together with the further demonstration of their crucial impact on aerosol formation in various environments24,26,30,31,32, has led to rapidly growing interest in understanding the HOM formation mechanism. In general, HOM formation proceeds through three consecutive steps that are tightly associated with the fate of peroxy radicals (RO2), including:

Step 1, the oxidation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that produce first-generation RO2;

Step 2, the autoxidation of RO2 that produces HOM-RO2 with higher numbers of oxygen atoms in the molecules;

Step 3, the termination of HOM-RO2 chain propagation through uni- or bi-molecular reactions that form closed-shell products, i.e., HOM.

While the above description refers to RO2 formed directly from parent VOCs (e.g., monoterpenes) as examples of first RO2, the same processes can also involve RO2 formed from multi-generation oxidation products. Early studies implicitly assumed that the HOM yields were pre-determined at Step 1 by the initial distribution of first-generation RO2. More specifically, it was assumed some first-generation RO2 were structurally favorable for potent autoxidation (i.e., with unity HOM yield), while other (and the majority of) RO2 could not autoxidize due to the lack of loosely bonded H atom or strong steric hindrance (i.e., with zero HOM yield). The overall HOM yields could then be expressed as a linear combination of the two extremes. With such a presumption, constant HOM yields, derived through a linear regression between HOM production rate and VOC oxidation rate in laboratory experiments, have been reported for certain combinations of VOC precursors and oxidants10,13,16,17,26,33,34. It should be noted that such an assumption was only made under a certain temperature, since it has been well recognized that the RO2 autoxidation is strongly temperature-dependent. For instance, it has been measured that the atmospheric concentrations of α-pinene HOM yields decrease with a decreasing temperature from 6.2 % at 298 K to 0.7 % at 223 K20.

More recently, the reaction kinetics of HOM formation have been extensively studied using laboratory experiments and computational methods, which revealed strong structure-activity relations in RO2 autoxidation and HOM formation10,16,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. It has been shown that the efficiency of autoxidation is strongly enhanced by the activating function groups (e.g., –OH, –OOH, =O) added to the carbon from which the H is being abstracted44, and suppressed by the steric hindrance of rigid transition state geometry (e.g., C3 and C4 rings)45. More importantly, it has been calculated that the first-order reaction coefficient of effective RO2 autoxidation, for monoterpene, mostly ranges in the order of 0.01 – 1 s−1 under typical atmospheric temperatures46, equivalent to a bi-molecular reaction rate with 2 ppt – 2 ppb of NO or HO2 (assuming k = 2 × 10−11 cm3 s−1)47 or 0.2 ppt – 20 ppb of RO2 (assuming kRO2 = 1 − 100 × 10−12 cm3 s−1)48. This means that RO2 autoxidation and bi-molecular reactions are occurring at comparable rates under atmospheric or atmosphere-relevant laboratory conditions. In light of this, the HOM yields ought to vary even under the same chemical system when concentrations of reacting species and/or oxidants are changing. However, such variations have seldom been recognized and reported in previous studies.

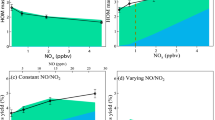

To our best knowledge, only a handful of studies have raised the concerns of the inconsistency in the HOM yields between experiment observations and theoretical expectations. Molteni et al.49 demonstrated that the production of C10-HOM species is non-uniform and non-linear in an ozone + monoterpene system. The addition of isoprene50,51,52 and sesquiterpene53 in monoterpene system can also change the yield of accretion HOM products (i.e., HOM dimers). In addition, a varying HOM yield has been shown in the monoterpene + NOx system, Shen et al.54 and Pye et al.55 found that HOM yields were significantly lower under high NO conditions compared to low NO. Building on these, Nie et al.56 demonstrated a non-monotonic response, with a maximal HOM yield observed at low but non-zero NO concentrations. Furthermore, increasing HO2 concentrations have been shown to suppress the formation of HOM-accretion products and alter the functionalization of HOM monomers, favoring hydroperoxide over carbonyl groups57. While HOM formation has been observed under different chemical settings, existing models such as Master Chemical Mechanism (MCM), Peroxy Radical Autoxidation Mechanism (PRAM)58 and the recently proposed automated alkoxy/peroxy radical autoxidation mechanism framework (autoAPRAM-fw)59 have also begun to provide detailed descriptions of HOM formation processes. However, there still lacks a unified and intuitive parameter that can capture the main factors controlling HOM yields across diverse conditions. Here, we first revisit experimental data from the CLOUD chamber and complement this analysis with additional data from other chambers and flow reactors. We point out that the variation in the HOM yields can be easily overlooked when using the linear-regression method (see Fig. 1a), where the yield is derived as the slope of the linear fit. Instead, the nuanced changes in the HOM yield can be clearly observed when calculated independently for each steady state condition. We further introduce a parameter, the oxidation fraction of RO2, which characterizes the potential of RO2 autoxidation and provides a unified description of the HOM yields for different chemical systems. At last, we highlight the importance of considering RO2 oxidation fraction in future HOM-formation experiments to ensure the representation of the real atmosphere.

a The common method as the dependence of HOM formation rates (PHOM) on monoterpene oxidation rate (MTreact), and (b) the new method as the dependence of the HOM yields on α-pinene oxidation rate, in which the HOM yields are calculated as the ratio of the HOM production rate over the α-pinene oxidation rate for each steady-state stage. Symbol types denote data from Ehn et al.26, Jokinen et al.33, Kirkby et al.17, Simon et al.20, and another α-pinene oxidation experiments conducted in CLOUD chamber. HOM are defined by NO ≥ 7 for this study, while for previous experiments, the HOM definitions follow those used in the original references. The data points are color-coded by experimental temperatures. Details about these experiments are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The grey dashed lines in (a) show different HOM yields and the lines in (b) are plotted to guide the eyes.

Results and discussion

Re-examination of the HOM yield from monoterpene oxidation

First, we revisit HOM data sets of α-pinene oxidation in the absence of NOx conducted in multiple laboratory facilities (see Methods). In these experiments, α-pinene was oxidized by O3 and OH, where OH was produced either by the reaction between α-pinene and O326,33 or additionally by the photolysis of O317,20. Details of the experimental conditions are listed in Supplementary Table 1. In Fig. 1a, we plot the production rate of HOM (PHOM) as a function of the monoterpene oxidation rates (MTreact), with the slope denoting the HOM yield. Besides a clear increasing trend in PHOM alongside the increase of MTreact, the slope decreases toward high MTreact, suggesting a decreasing tendency of the HOM yield. In previous studies, the HOM yields have often been obtained as the slope of a linear fit between PHOM and MTreact determined for multiple steady-state stages, which only reflected an average HOM yield of the multiple stages in the experiment but ignored the subtle variation. To better reveal the variation in the HOM yield, we calculate the HOM yield (i.e., PHOM/MTreact) of each steady-state stage and plot it against MTreact. As shown in Fig. 1b, the HOM yields decrease considerably at high MTreact. For instance, the HOM yields decrease approximately from 10% to 6% in the experiment conducted by Ehn et al., where a 7% average HOM yield has been reported26.

In Fig. 1, we also observe notable systematic differences in the HOM yields and their decreasing tendencies between experimental datasets. This could be attributed to a few factors. First, these experiments were conducted at different temperatures, which greatly affects the RO2 autoxidation. Second, the relative abundance of O3 and OH were not the same in these experiments. O3-initiated α-pinene oxidation is known to have a higher HOM yield compared to the OH-initiated oxidation17,26,60. Third, the definition of HOM in these studies is not consistent. Specifically, HOM were either defined as all species measured with a NO3-CIMS in some studies17,20, or by the mass-to-charge ratio between 280 and 620 Th33. It should be clarified that HOM is defined by the number of oxygen atoms (NO) ≥ 7 in this study, despite that NO ≥ 6 has been suggested as a more appropriate criterion from a theoretical aspect26,61. This practical choice aligns with our use of NO3-CIMS, which has good sensitivity for HOM with seven or more oxygen atoms62. Last but not least, measurement uncertainty, which has been reported as ~±50%, also contributes to the systematic differences of the HOM yields17,26.

Mechanistic understanding of the varying yield

Next, we investigate the fundamental mechanism of the varying yield based on a proof-of-concept experiment. This experiment was conducted in the CLOUD chamber at 278 K. The configuration of CLOUD chamber facilities is provided in our previous works and the detailed experimental settings are described in Methods. Briefly, the concentration of α-pinene was changed stepwise from 30 ppt to 1050 ppt, covering the typical monoterpene concentration in the atmosphere (Supplementary Fig. 1). We calculate the HOM yields at these monoterpene concentrations under steady state (see Methods). As shown in Fig. 2a, the HOM yields decrease by >60%, from 2.7% to 1.0%, when the α-pinene concentration increases from 30 ppt to 1050 ppt, corresponding to an α-pinene oxidation rate of 1.20 × 105 cm−3s−1 to 3.97 × 106 cm−3s−1 (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Meanwhile, we simulate HOM formation in the experiment by employing the Aerosol Dynamics gas- and particle-phase chemistry model for laboratory CHAMber studies (ADCHAM)63. This model integrates the comprehensive Peroxy Radical Autoxidation Mechanism (PRAM) and Master Chemical Mechanism (MCMv3.3.1), and also incorporates HOM deposition on chamber walls and condensation/evaporation on particle surfaces63. Details of the model setups are provided in Methods. The model performance is verified by the reasonable agreement with experimental observations for the concentrations of both hydroxyl radicals (OH) and different HOM species at different α-pinene concentrations (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Although some deviations exist between simulated and observed concentrations, the model captures the overall HOM distribution well, with coefficients of determination (R2) exceeding 0.7 across different conditions.

a The relative contribution of various chemical and physical processes to the fate of p-HOM-RO2 and its lifetime, (b)HOM monomer yield, and (c) HOM dimer yield as the function of α-pinene oxidation rate (as well as α-pinene concentration). Bars and blue dots indicate measured and simulated values, respectively. Colored segments within the bars reflect the volatility classification of observed HOMs, including ULVOC (ultra-low-volatility organic compounds), ELVOC (extremely-low-volatility organic compounds), LVOC (low-volatility organic compounds), and SVOC (semi-volatile organic compounds), determined using the volatility basis set model20 with temperature dependence considered88,89. The propagated uncertainty of the HOM yields varies within 20 % in simulations.

This level of agreement enables us to quantify the fate of RO2 on a quasi-molecular level and further investigate the fundamental reasons why the HOM yield varies as a function of the α-pinene oxidation rate. To aid the illustration, we classify RO2 into a few categories according to their roles in HOM formation. First, RO2 containing at least 7 oxygen atoms are termed HOM-RO2. They are the direct precursors of HOM through termination reactions, and thus the HOM yields are directly associated with the formation of HOM-RO2. Second, in light of a recent study by Iyer et al.37, only a small fraction of initial RO2 can autoxidize and potentially become HOM-RO2. This type of RO2 is termed potential HOM-RO2 (p-HOM-RO2). In our model, the fractions of first-generation p-HOM-RO2 are set as 1.12% and 9% of the total initial RO2 for OH-initiated and O3-initiated α-pinene oxidation, respectively (Supplementary Table 4). The fraction of p-HOM-RO2 becoming HOM-RO2 is regulated by the competition between autoxidation and termination. Third, the rest of the initial RO2, incapable of autoxidation, is termed non-HOM-RO2. They solely act as a reaction partner of p-HOM-RO2 and HOM-RO2 through RO2 cross-reactions. The schematics describing the relationship and roles of these different RO2 categories are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. A similar consideration has been incorporated in the R2D-VBS model developed by Schervish and Donahue64,65,66 and the CRI-HOM model by Weber et al.67.

As illustrated above, the fate of p-HOM-RO2 determines the overall HOM yield. Therefore, we quantify the probability of p-HOM-RO2 undergoing autoxidation versus termination reactions in the experiment using the ADCHAM model by calculating the contribution of various chemical and physical processes of p-HOM-RO2 as a function of α-pinene concentration. As shown in Fig. 2a, along with the increase in α-pinene oxidation rate (achieved by increasing α-pinene concentration while maintaining constant O3 and OH concentrations), the relative contribution of RO2 cross-reactions progressively increases, while that of RO2 autoxidation gradually decreases. This is because the rates of RO2 cross-reactions are proportional to the square of the total RO2 concentration, while the rate of RO2 autoxidation is linearly proportional to the p-HOM-RO2. From another perspective, the substantial enhancement of RO2 cross-reactions reduces the lifetime of p-HOM-RO2, thereby lowering its probability of undergoing autoxidation. This results in a significant reduction in the formation of HOM-RO2 and eventually in the HOM yield.

If all bi-molecular termination reactions of p-HOM-RO2 (with other RO2 and HO2) strictly stop the radical propagation, a reduction in p-HOM-RO2 lifetime by 83% should cause a reduction in the HOM yield by the same fraction. However, we only observe a decline in the HOM yield by 62%. This reduction is attributed to the formation of alkoxy radicals (RO) via bimolecular termination pathways47. RO can also undergo fast intra-molecular H-shift followed by O2 addition, referred to as “RO autoxidation” hereafter. The RO autoxidation mechanism is kinetically possible and needs to be invoked to explain HOM distribution in previous studies39,49,56.The branching ratios of RO formation channels are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

In accordance with the formation mechanism, HOM of different types (i.e., monomers and dimers) show notably different responses to the VOC oxidation rate. HOM monomers, mostly classified as low-volatility organic compounds (LVOC, 10−4.5 μg/m3 ≤ C* ≤ 10−0.5 μg/m3), are responsible for the growth of nanoparticles22. Differently, HOM dimers are mostly ultra-low volatility organic compounds (ULVOC, C* < 10−8.5 μg/m3) and extremely low volatility organic compounds (ELVOC, 10−4.5 μg/m3 < C* ≤ 10−8.5 μg/m3) that can be important for particle nucleation18. Therefore, capturing their responses is crucial for the model prediction of new particle formation. As shown by both the observation and model simulation, HOM monomers (NC ≤ 10 and NO ≥ 7) are direct products of HOM-RO2, and thus, the yields of HOM monomers largely follow the change of HOM-RO2, showing a monotonically decreasing trend (Fig. 2b). Differently, HOM dimers (NC > 10 and NO ≥ 7), as referred to in this work, are accretion products of the cross-reactions of two monoterpene-derived RO2 (RO2 + R’O2 → ROOR’ + O2). Reactions between all types of RO2 may form HOM dimers, as long as the two parent RO2 together contain 9 or more oxygen atoms. Consequently, the yield of HOM dimers increases with α-pinene concentration until the step of 400 ppt α-pinene, due to enhanced RO2 cross reactions that directly form dimers. At higher concentration, the yield gradually declines as the autoxidation of p-HOM-RO2 is increasingly outcompeted by terminating reactions, particularly RO2 cross reactions involving species with fewer oxygens (Fig. 2c).

A framework quantifying the HOM yield

As discussed above, the HOM yield is essentially affected by both the yield of first p-HOM-RO2 (γp-HOM-RO2) and the probability that the formed p-HOM-RO2 undergoes further oxidation to become HOM-RO2. The former is pre-determined by the chemical system (the type of VOC and oxidant), while the latter depends on the competition between the oxidation and loss processes of p-HOM-RO2. To quantitatively describe this competition, we introduce a normalized parameter, the oxidation fraction of p-HOM-RO2 (OFp-HOM-RO2), defined as oxidation/(oxidation + loss) (see Methods). This parameter ranges from 0 to 1, reflecting the probability that p-HOM-RO2 proceed to form HOM-RO2 rather than being removed by loss processes. In this formulation, oxidation includes both RO2 and RO autoxidation pathways, whereas loss encompasses condensation onto chamber and aerosol surfaces, as well as bimolecular reactions with RO2, NOx, and HO2. Conceptually, OFp-HOM-RO2 is analogous to the survival probability widely used in new particle formation studies, which describes the fraction of nascent particles that can grow rather than be lost to coagulation22,68.

We examine the relationships of γp-HOM-RO2, OFp-HOM-RO2, with the HOM yields among 5 experimental settings (and 23 steady-state conditions), covering different monoterpene types (α-pinene and Δ−3-carene) and concentrations, and various NOx conditions. The O3 concentration was kept nearly constant at ~40 ppb across these experiments, as detailed in Supplementary Table 2. Supplementary Fig. 5a shows the relationship between γp-HOM-RO2 and the HOM yields. Within each experimental setting, the change in γp-HOM-RO2 is mainly driven by the varying relative contribution of different oxidants, i.e., O3, OH, and NO3. For instance, when NOx is involved in experiments, an elevated NOx level translates into greater contribution by NO3-initiated oxidation and larger γp-HOM-RO2 (see Supplementary Table 4). In most NOx-involved experiments, HOM yields increase with γp-HOM-RO2, except in the “pure NO2” experiments, where an opposite dependence is observed. This indicates that γp-HOM-RO2 is not the sole factor determining the HOM yield. For any given γp-HOM-RO2, a higher HOM yield is generally observed at greater OFp-HOM-RO2. This is exemplified by the experiments without NOx, where γp-HOM-RO2 remains relatively constant at ~0.06 (filled circles in Supplementary Fig. 5a), while the HOM yield increases from ~1% to ~2.6% as OFp-HOM-RO2 rises from ~0.2 to ~0.7. To further illustrate this relationship, Supplementary Fig. 5b shows the HOM yield as a function of OFp-HOM-RO2 across all conditions. While both γp-HOM-RO2 and OFp-HOM-RO2 contribute to the variability in HOM yields, the relatively small variation in γp-HOM-RO2 across the dataset makes its effect less evident, yet it still plays a meaningful role in shaping HOM formation. Therefore, we additionally examine the product of γp-HOM-RO2 and OFp-HOM-RO2, which captures the combined effect of formation efficiency and availability of the precursor, and yields the strong correlation with HOM yield (Fig. 3). To conclude, γp-HOM-RO2 and OFp-HOM-RO2 determine the HOM yield synergistically. The former represents a theoretical upper bound of the HOM yield; the latter regulates the fraction of p-HOM-RO2 that can eventually form HOM.

Square, Down Triangle, Rhombus, Left Triangle, and Circle denote data from CLOUD experiments of varying NO (Exp 1), pure NO2 (Exp 2), constant NO/NO2 with 1200 ppt monoterpene (Exp 3), constant NO/NO2 with 300 ppt monoterpene (Exp 4) and NOx-free conditions (Exp 5), respectively. Note that the monoterpene used in the NOx-involved experiments was a mixture of α-pinene and Δ−3-carene with a volume mixing ratio of 2:1. The monoterpene used in the NOx-free experiment was pure α-pinene. The propagated error of the HOM yields varies within 10 % among different experiments. A significant monotonic correlation is observed, with Kendall’s tau τ = 0.747 (p < 0.01), accounting for small sample size and potential non-linearity.

We have shown in Fig. 1b that the dependence of the HOM yields on α-pinene oxidation rates seems to vary at different temperatures. Although a quantitative understanding of this phenomenon requires future studies on the exact temperature effects on the kinetics of RO2/RO autoxidation, the parameter OFp-HOM-RO2 helps to explain it qualitatively. High temperature enhances RO2 autoxidation20,69 without significantly affecting the bi-molecular termination reactions. Thus, greater OFp-HOM-RO2 can be expected in higher-temperature experiments, leading to higher HOM yields, e.g., those reported by Ehn et al.26. Conversely, when RO2 autoxidation is substantially suppressed at low temperatures, the RO2 termination could always outcompete the autoxidation even at low α-pinene oxidation rates, explaining the stable and low HOM yields reported by Simon et al.20.

Although this framework has been evaluated under monoterpene oxidation conditions, it is theoretically applicable to broader VOC systems. In more complex environments, additional RO2 radicals (e.g., CH3O2) can compete with autoxidation by enhancing the loss of p-HOM-RO2, thereby lowering HOM yields. Since these radicals act in the same way as the non-HOM-RO2 already considered, their influence should be inherently captured by the unified parameter as long as they are represented in the model. Another remaining challenge is that the role of RO2 formed from multi-generation products is not explicitly considered. This omission is minor for monoterpenes, where HOM formation is dominated by the rapid autoxidation of first-generation RO2, but it becomes important in systems such as isoprene and aromatics where multi-generation chemistry contributes substantially. In such cases, the framework could be extended by treating first-generation products, i.e., OVOCs, as separate precursors and reapplying the same formulation, though this extension is required further validation under more complex and representative conditions.

Summary and atmospheric implications

In summary, we revisit HOM datasets obtained from various laboratory experiments and show that the HOM yield is varying instead of staying constant, consistent with the dynamic nature of the HOM formation process. We further perform robust, near-explicit gas-phase chemistry model simulations, which enable us to investigate the fate and roles of different types of RO2 regarding HOM formation. We demonstrate that the varying HOM yields are caused by the complex interaction between different types of RO2 (non-HOM-RO2, p-HOM-RO2, and HOM-RO2), HO2, and NOx, which modulates the competition between the autoxidation and loss of p-HOM-RO2 under different experimental conditions. Based on this insight, we develop a parameter that characterizes the probability of p-HOM-RO2 becoming HOM-RO2, providing a unified quantification of the HOM yield.

Our findings indicate that the majority of previous laboratory studies regarding HOM formation (also very likely SOA formation) are not representative of the real atmosphere. This can be seen from two aspects. First, it is a common practice to use high VOC oxidation rates (i.e., either high VOC concentration, high oxidant concentration, or both) in most previous laboratory experiments to overcome the limitation of instrumental detection and lab-specific loss processes. Taking α-pinene oxidation experiments as an example, the typical atmospheric concentration of α-pinene ranges from a few to a few hundred ppt70,71,72,73,74 corresponding to an oxidation rate of about 106 – 107 cm−3s−1 at around 40 ppb of O3 and 5 × 106 cm−3 of OH. However, most earlier laboratory experiments were conducted with an α-pinene oxidation rate 1 – 3 orders of magnitude higher than in the atmosphere (Fig. 4a). Second, NO levels in laboratory studies often deviate from those in the real atmosphere. While NO is a key modulator of RO2 fate by competing with autoxidation through RO2 + NO reaction, its levels in earlier chamber experiments were often either zero or above 100 ppt. In contrast, NO concentrations in forested or remote environments generally lie between 1–100 ppt. Only a few advanced chamber setups, such as CLOUD and JPAC (Jülich Plant Atmosphere Chamber facility), have operated within this atmospherically relevant NO range.

a Summarizes the distributions of monoterpene reaction rates (MTreact) measured in chamber experiments (pink background), flow reactors (blue background), and field observations. The box whiskers and edges are 10%, 25%, 75%, and 90% percentiles from left to right, with the red line and blue dots indicating median and mean values. b Shows the simulated HOM yields from monoterpene ozonolysis at 278 K, together with laboratory data (blue-bordered markers denote CLOUD and JPAC measurements, while borderless markers correspond to other studies). The grey shaded regions indicate typical atmospheric ranges of NO concentrations and monoterpene oxidation rates, and the grey dots represent ambient observations from the SMEAR II station in Finland90. The grey dashed line indicates the convex polygonal boundary of the grey points. The dashed line in (b) indicate non-detectable levels of NO, NOx-free environment. Details of the previous laboratory studies26,35,56,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105 involved in the figure are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

To evaluate how these deviations may affect HOM yields, Fig. 4b maps HOM yield as a function of MTreact and NO concentration. These two variables jointly represent key aspects of the radical environment. MTreact reflects the RO2 production flux from monoterpene oxidation, setting the baseline abundance of p-HOM-RO2 and the competition for its loss, and NO directly shifts the balance between RO2 oxidation and termination. This MTreact–NO space has been widely used in laboratory studies and provides a physically meaningful and practically accessible framework for cross-comparison. Our analysis indicates that monoterpene HOM yields range from about 2% to 5% in typical atmospheric conditions, whereas it is far below 1 % in most laboratory reactors - except for specialized setups like the CLOUD and JPAC chambers. Since HOM parameterization in large-scale models is informed by laboratory studies, biased HOM yields due to inappropriate experimental settings limit our ability to evaluate the global HOM budget. This highlights the need to align experimental conditions closely with atmospheric conditions to obtain accurate HOM yields.

Nevertheless, this simplified representation cannot account for additional influences such as HO2, NOx, and RO2 from other parent VOCs. To address this, our framework proposes a unified parameter that integrates both the initial production of RO2 and its subsequent oxidation fraction, providing a meaningful metric for HOM formation under diverse radical environments. Although the present analysis does not directly apply this parameter due to the lack of constrained radical measurements, future studies with more complete radical budgets will allow its broader implementation. Very recently, Kenagy et al.75. proposed a four-dimensional framework that characterizes the fate of RO2 by evaluating the relative contribution of different bi-molecular reactions. Our framework describes RO2 from a different angle by characterizing the potential of autoxidation. These two compatible frameworks can be used in conjunction to provide a more comprehensive understanding of RO2 reactions and overall probability of HOM formation.

Beyond unifying RO2 chemistry at the mechanistic level, the variability in HOM yields exerts pronounced influences on particle number concentrations and mass, linking gas-phase chemistry to particle formation. Following the parameterization of Lehtipalo et al.18, the nucleation rate depends linearly on HOM dimer, which increases by approximately two orders of magnitude before decreasing by about 10%. Under the same conditions, assuming complete condensation of LVOCs and lower-volatility vapors, SOA mass yields decrease by up to ~60% (see Fig. 2). This contrast highlights that HOM yield variability has significant impact on both particle number and mass.

In addition to the HOM yield, the actual oxidation pathway of p-HOM-RO2 can notably influence the functionality of HOM. For instance, at low RO2 loss rates (e.g., low MTreact and low NO concentration), the RO2 autoxidation is the major pathway of p-HOM-RO2 oxidation, resulting in more hydroperoxyl (R-OOH) groups in HOM; conversely, at high RO2 loss rates, RO autoxidation is a more feasible way of p-HOM-RO2 oxidation, leading to more hydroxyl (R-OH) groups in HOM. When SOA is formed through the gas-to-particle conversion of HOM, distinctions of the functionality will propagate in SOA, affecting the chemical and physical properties of aerosols, which may further modify the impacts of aerosols on the environment and human health. For instance, the hygroscopicity of aerosols is greatly influenced by the abundance of R-OH groups in the hydrophobic aliphatic chain76, which is crucial for their ability to act as cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) and alter rainfall duration and intensity77. The particle volatility is also substantially affected by their functional groups. A single R-OOH group can reduce the vapor pressure by ~250-fold, whereas the addition of R-OH group reduces the vapor pressure by about 160-fold78. Moreover, R-OOH groups are key reactive oxygen species in particles that greatly contribute to aerosol toxicity79,80. The functional groups also significantly influence the viscosity of aerosols. The carboxylic acids (-COOH) and R-OH groups increase the viscosity more than other functional groups, with sensitivity rising in compounds that are highly functionalized compounds or at lower temperatures81.

Methods

Data source

The data source for this study are derived from a variety of experiments conducted under different conditions, selected based on specific criteria. To be included in this study, an experiment must involve α-pinene oxidation, employ Nitrate-CIMS for detection and provide information on α-pinene concentration or their reaction rate. The experiments are divided into two categories: flow reactor and chamber experiments.

The Jokinen’s experiment was conducted in a flow tube with α-pinene ranging from 0.09 to 173.95 ppb and O3 concentrations from 23.9 to 25.5 ppb33. Additionally, several chamber experiments were conducted under varying conditions. The experiment conducted by Ehn et al. was carried out at Jülich Plant Atmosphere Chamber facility (JPAC)26 with a temperature of 289 K, relative humidity of 63 %, α-pinene concentrations of 1–30 ppb and O3 concentrations of 12−86 ppb. Kirkby et al.17 conducted experiments in CLOUD chamber (Cosmics Leaving OUtdoor Droplets) at 38% relative humidity, 278 K, with α-pinene concentrations of 70−440 ppt, O3 at 21−35 ppb with UV levels ranging from 0% to 100%. Simon et al.20 also employed the CLOUD chamber at 5 different temperatures, with α-pinene concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1 ppb and O3 levels varying between 30 and 40 ppb.

The primary data in this study were obtained from additional experiments conducted in the CLOUD chamber. In these experiments, pure α-pinene was gradually increased from 0 to ~1 ppb, with steady state concentrations of 30 ppt, 70 ppt, 180 ppt, 400 ppt, 850 ppt, and 1050 ppt. O3 was directly injected into the chamber, while OH was produced both from the ozonolysis of monoterpene and by the photolysis of ozone. The concentrations of O3 and OH were kept stable during each experiment (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The loss of HOM was mainly due to the chamber wall loss and loss onto particle surfaces, whereas the loss by dilution was negligible (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Additionally, it should be noted that the definition of HOM employed in this study differs from these experiments, where HOM were defined based on specific spectral ranges in NO3-CIMS. However, in this study, we define as HOM containing at least 7 oxygen atoms, which are assumed to be sufficiently sensitive in NO3-CIMS. Monoterpene was measured using a proton transfer reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometer (PTR3)82, while SO2 and O3 were measured using Thermo Scientific gas monitors (model 42i for SO2 and model 49i for O3).The dilution loss rate was within 1-2 × 10−4 s−1 17, 20, corresponding to a residence time of ~120 min.

Calculation of the HOM yields

HOM is formed through a series of reactions initiated by the oxidation of precursor VOCs. In this study, the oxidants involved are O3 and OH. OH concentration in CLOUD chamber was calculated using the following equation:

Where kloss represents the loss rate of sulfuric acid due to condensation onto aerosol particles (condensation sink) and to the chamber wall (wall loss); kSO2+OH is the reaction rate constant between OH and SO2 at 278 K, which was set at 1.2 × 10−12 cm3s−1 83. Under steady-state conditions, the production rate of HOM is equivalent to its loss rate. Therefore, the HOM yields can be expressed as

The wall and condensational losses for HOM were calculated. For wall losses, the molecules detected by Nitrate-CIMS84,85 usually have a very low saturation vapor pressure, leading to the assumption that they undergo irreversible losses upon contact with the surface. We adopted the method of Simon et al.20 to calculate: the diffusion coefficients Di for each HOMi are approximated with the expression:

where Mi (g mol−1) is the mass of the molecule. The wall loss rate inside the CLOUD chamber at each temperature is determined from the following expression:

where Cwall is an empirical parameter and set to 0.0075 cm−1 s−0.5 at 5 °C in this study.

ADCHAM model

We use the Aerosol Dynamics gas- and particle-phase chemistry model for laboratory CHAMber studies (ADCHAM)63 with a detailed gas-phase kinetic code that combines peroxy radical autoxidation mechanism (PRAM) and MCMv3.3.1 using the Kinetic PreProcessor (KPP)86. As described by Roldin et al.58, like most current model frameworks for modelling HOM formation64,67, by assigning specific molar yields for the formation of the first p-HOM-RO2 that initiates the autoxidation chain, PRAM further explicitly described how autoxidation proceeds through successive intramolecular H shift and O2 addition. Autoxidation can be terminated by a bimolecular reaction in which the formed RO2 reacts with NOx, HO2 and other RO2.

In our model, the rate constants for RO2 + NOx and RO2 + HO2 reactions are adopted directly from the MCMv3.3.1, using the structure-independent rate constants. For the RO2 + HO2 reaction, the product formed is always a closed-shell molecule with a hydroperoxide functional group (-OOH) replacing the peroxy group (-OO · ).

For RO2 + RO2 reactions, which can lead to either alkoxyl radicals (RO · ), closed-shell monomers, or dimers, we follow the structure-dependent treatment described in the PRAM framework. Given the large number of RO2 in the mechanism, assigning individual rate constants for all possible RO2–RO2 combinations is computationally impractical. To address this, we adopt a hybrid approach:

RO2 + RO2 reactions leading to RO and closed-shell monomer products are treated using a simplified “RO2 pool” scheme. All RO2 radicals are assumed to react collectively, and the total rate of RO2 cross-reactions for a given species is approximated as a pseudo-unimolecular reaction with a rate coefficient of k × Σ[RO2], where Σ[RO2] is the sum of all RO2 concentrations. This ensures computational efficiency while retaining a representation of overall termination by RO2–RO2 interactions.

RO2 + RO2 reactions forming HOM dimers are treated explicitly as bimolecular reactions between selected RO2 types. We differentiate between p-HOM-RO2 (capable of autoxidation) and non-HOM-RO2 (those that do not autoxidize). p-HOM-RO2, due to their high oxygen content, are assigned faster dimerization rates. Non-HOM-RO2, while typically more abundant, are assumed to promote accretion with slower rates. This treatment captures key differences in dimer formation potential between RO2 subtypes while maintaining model simplicity.

The rate constants for RO2 + RO2 reactions are further scaled based on the oxygen content of the reacting species. RO2 with lower oxygenation are assigned lower rate constants, while those with higher oxygen content are given higher rates, consistent with their increased reactivity toward dimer formation. Specifically, rate constants for RO2 + RO2 reactions leading to closed-shell monomers range from 1 × 10−12 to 1 × 10−11 cm3s−1, while those leading to HOM dimers span 8 × 10−15 to 8 × 10−13 cm3s−1 depending on the oxygen content of the reacting RO2. Detailed assignments of reaction pathways, branching ratios, and rate constants are summarized in Supplementary Table 4.

Calculation of the p-HOM-RO2 yields (γp-HOM-RO2)

The p-HOM-RO2 yields are determined by the type of VOCs and oxidants. In this study, α-pinene was used as the only VOC precursor and the oxidants involved were O3 and OH. However, in the NOx experiments, not only the effect of NO3 as oxidant was introduced, but also a mixture of 2:1 α-pinene and Δ−3-carene comprised the VOC precursors. We therefore calculated the average yields for these different conditions based on VOC and oxidant concentrations, defined as the ratio of the first p-HOM-RO2 yields to the monoterpene reaction rate:

where k is the rate constant for the reaction of the VOC with the oxidant, which is the same as in Master Chemical Mechanism version 3.3.1 (MCMv3.3.1, http://mcm.leeds.ac.uk/MCM/). γMT, oxidant denotes the first p-HOM-RO2 yield for different monoterpenes and oxidants, deriving from a combination of literature-based mechanistic insights and adjustments to more accurately replicate the observed HOM concentrations:

For α-pinene + O3, we adopt a first p-HOM-RO2 yield of 9%, following the theoretical considerations of Iyer et al.37. In their study, α-pinene ozonolysis is assumed to form four Criegee intermediates with roughly equal likelihood (~25%), but only one of them efficiently forms RB1-RO2 capable for autoxidation (with a branching ratio of ~89%), leading to a maximum yield of ~22%. In a lower-limit scenario (~12% branching ratio), this value decreases to ~3%. Given the large uncertainty in these branching ratios (3–22%), we chose 9% as a representative value that falls within the physically reasonable interval and provides good agreement with observed HOM concentrations. For the same consideration, we use a γp₋HOM₋RO2 of 1.12%, corresponding to the upper limit of reported HOM yields in α-pinene + OH system (~0.44% by Jokinen et al.33, 1.1% by Shen et al.54 and 1.2% by kirkby et al.17).

Calculation of the oxidation fraction of p-HOM-RO2 (OFp-HOM-RO2)

To characterize the competition between oxidation and termination processes of autoxidation-capable RO2 radicals (p-HOM-RO2), we define a metric, the Oxidation Fraction (OFp-HOM-RO2), as

The oxidation rate pertains to the rate at which p-HOM-RO2 (defined as RO2 species are capable of autoxidation and contains fewer than 7 O atoms) becomes HOM-RO2 ( ≥ 7 O atoms):

Autoxidation pathway

A H-shift followed by O2 addition adds two O atoms per step. Thus, p-HOM-RO2 with at least 5 O atoms can reach the HOM-RO2 threshold via one autoxidation step.

RO pathway

RO radicals formed via RO2 + RO2 or RO2 + NO reactions can undergo rapid isomerization followed by O2 addition, contributing one O atom. Therefore, p-HOM-RO2 with 6 O atoms can become HOM-RO2 through this route.

The contribution from RO pathway can be calculated using the following equation:

where \({\gamma }_{{{RO}}_{2}-{RO}}\) and \({\gamma }_{{NO}-{RO}}\) denote the branching ratios of RO that eventually form new RO2 from RO2-RO2/NO reactions, respectively. These parameters, like the reaction rate constants, are determined by the property of the precursor p-HOM-RO2.

The loss rate of p-HOM-RO2 encompasses influences from surfaces losses to chamber walls and particles and chemical loss through termination reactions with other RO2, NOx and HO2. For condensation sinks and wall losses, we apply the same calculation method for p-HOM-RO2 as for closed-shell molecules. Reactions of RO2 with HO2 and NO2 are all treated as termination. As for the reaction of RO2 with NO/RO2, all of reactions are termination except for the portion (\({\gamma }_{{{RO}}_{2}-{RO}}\) and \({\gamma }_{{NO}-{RO}}\)) that produces RO.

In this calculation, the p-HOM-RO2 pool is treated as an integrated whole. The numerator in Eq.6 represents the total rate at which p-HOM-RO2 are converted into HOM-RO2 (i.e., RO2 with ≥7 O atoms) through autoxidation or RO pathways. The denominator includes all processes that remove p-HOM-RO2 from this pool, including both oxidation and termination reactions. Importantly, internal transformations within the p-HOM-RO2 pool (e.g., oxygen addition that does not lead to HOM-RO2 formation) are not considered, as they do not reflect a net transition out of the p-HOM-RO2 category. This approach allows us to assess the net competition between oxidation and loss for the whole p-HOM-RO2 pool.

Data availability

All datasets supporting the figures in this study are publicly accessible via Figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30146215.v187.

References

Li, Z. Q. et al. Aerosol and boundary-layer interactions and impact on air quality. Natl. Sci. Rev. 4, 810–833 (2017).

Harrison, R. M. & Yin, J. X. Particulate matter in the atmosphere: which particle properties are important for its effects on health?. Sci. Total Environ. 249, 85–101 (2000).

Lin, P. & Yu, J. Z. Generation of reactive oxygen species mediated by humic-like substances in atmospheric aerosols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 10362–10368 (2011).

Daellenbach, K. R. et al. Sources of particulate-matter air pollution and its oxidative potential in Europe. Nature 587, 414–419 (2020).

Andreae, M. O., Jones, C. D. & Cox, P. M. Strong present-day aerosol cooling implies a hot future. Nature 435, 1187–1190 (2005).

Ehn, M. et al. Composition and temporal behavior of ambient ions in the boreal forest. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 8513–8530 (2010).

Zhao, D. F. et al. Highly oxygenated organic molecule (HOM) formation in the isoprene oxidation by NO3 radical. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 9681–9704 (2021).

Wang, S. N., Riva, M., Yan, C., Ehn, M. & Wang, L. M. Primary formation of highly oxidized multifunctional products in the oh-initiated oxidation of isoprene: a combined theoretical and experimental study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 12255–12264 (2018).

Berndt, T., Hoffmann, E. H., Tilgner, A. & Herrmann, H. Highly oxidized products from the atmospheric reaction of hydroxyl radicals with isoprene. Nat. Commun. 16, 12 (2025).

Richters, S., Herrmann, H. & Berndt, T. Highly oxidized RO2 radicals and consecutive products from the ozonolysis of three sesquiterpenes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 2354–2362 (2016).

Richters, S., Herrmann, H. & Berndt, T. Different pathways of the formation of highly oxidized multifunctional organic compounds (HOMs) from the gas-phase ozonolysis of β-caryophyllene. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 9831–9845 (2016).

Garmash, O. et al. Multi-generation OH oxidation as a source for highly oxygenated organic molecules from aromatics. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 515–537 (2020).

Molteni, U. et al. Formation of highly oxygenated organic molecules from aromatic compounds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 1909–1921 (2018).

Wang, M. Y. et al. Photo-oxidation of aromatic hydrocarbons produces low-volatility organic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 7911–7921 (2020).

Rissanen, M. Anthropogenic Volatile Organic Compound (AVOC) Autoxidation as a Source of Highly Oxygenated Organic Molecules (HOM). J. Phys. Chem. A 125, 9027–9039 (2021).

Berndt, T. et al. Gas-phase ozonolysis of cycloalkenes: formation of highly oxidized RO2 radicals and their reactions with NO, NO2, SO2, and Other RO2 radicals. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 10336–10348 (2015).

Kirkby, J. et al. Ion-induced nucleation of pure biogenic particles. Nature 533, 521–526 (2016).

Lehtipalo, K. et al. Multicomponent new particle formation from sulfuric acid, ammonia, and biogenic vapors. Sci. Adv. 4, 9 (2018).

Riccobono, F. et al. Oxidation products of biogenic emissions contribute to nucleation of atmospheric particles. Science 344, 717–721 (2014).

Simon, M. et al. Molecular understanding of new-particle formation from alpha-pinene between -50 and +25 °C. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 9183–9207 (2020).

Stolzenburg, D. et al. Rapid growth of organic aerosol nanoparticles over a wide tropospheric temperature range. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9122–9127 (2018).

Trostl, J. et al. The role of low-volatility organic compounds in initial particle growth in the atmosphere. Nature 533, 527–531 (2016).

Yan, C. et al. Size-dependent influence of NOx on the growth rates of organic aerosol particles. Sci. Adv. 6, 9 (2020).

Nie, W. et al. Secondary organic aerosol formed by condensing anthropogenic vapours over China’s megacities. Nat. Geosci. 15, 255–261 (2022).

Liu, Y. L. et al. Exploring condensable organic vapors and their co-occurrence with PM2.5 and O3 in winter in Eastern China. Environ. Sci. Atmos. 3, 282–297 (2023).

Ehn, M. et al. A large source of low-volatility secondary organic aerosol. Nature 506, 476–479 (2014).

Jimenez, J. L. et al. Evolution of organic aerosols in the atmosphere. Science 326, 1525–1529 (2009).

Hallquist, M. et al. The formation, properties and impact of secondary organic aerosol: current and emerging issues. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 5155–5236 (2009).

Wang, G. H. et al. High loadings and source strengths of organic aerosols in China. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL027624 (2006).

Kulmala, M. et al. Direct observations of atmospheric aerosol nucleation. Science 339, 943–946 (2013).

Lee, A. K. Y. et al. Substantial secondary organic aerosol formation in a coniferous forest: observations of both day- and nighttime chemistry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 6721–6733 (2016).

Yan, C. et al. The synergistic role of sulfuric acid, bases, and oxidized organics governing new-particle formation in beijing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, 12 (2021).

Jokinen, T. et al. Production of extremely low volatile organic compounds from biogenic emissions: Measured yields and atmospheric implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7123–7128 (2015).

Rissanen, M. P. et al. The formation of highly oxidized multifunctional products in the ozonolysis of cyclohexene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 15596–15606 (2014).

Zhao, Y., Thornton, J. A. & Pye, H. O. T. Quantitative constraints on autoxidation and dimer formation from direct probing of monoterpene-derived peroxy radical chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 12142–12147 (2018).

Jokinen, T. et al. Rapid autoxidation forms highly oxidized RO2 radicals in the atmosphere. Angew. Chem.-Int Ed. 53, 14596–14600 (2014).

Iyer, S. et al. Molecular mechanism for rapid autoxidation in α-pinene ozonolysis. Nat. Commun. 12, 6 (2021).

Pasik, D. et al. Gas-phase oxidation of atmospherically relevant unsaturated hydrocarbons by acyl peroxy radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 13427–13437 (2024).

Mentel, T. F. et al. Formation of highly oxidized multifunctional compounds: autoxidation of peroxy radicals formed in the ozonolysis of alkenes - deduced from structure-product relationships. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 6745–6765 (2015).

Rissanen, M. P. et al. Effects of chemical complexity on the autoxidation mechanisms of endocyclic alkene ozonolysis products: from methylcyclohexenes toward understanding alpha-pinene. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 4633–4650 (2015).

Jorgensen, S. et al. Rapid hydrogen shift scrambling in hydroperoxy-substituted organic peroxy radicals. J. Phys. Chem. A 120, 266–275 (2016).

Crounse, J. D., Nielsen, L. B., Jorgensen, S., Kjaergaard, H. G. & Wennberg, P. O. Autoxidation of organic compounds in the atmosphere. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 3513–3520 (2013).

Knap, H. C. & Jorgensen, S. Rapid hydrogen shift reactions in acyl peroxy radicals. J. Phys. Chem. A 121, 1470–1479 (2017).

Jakobsen, O. tkjaerR. V., Tram, H. H. & Kjaergaard, C. M. HG. Calculated hydrogen shift rate constants in substituted alkyl peroxy radicals. J. Phys. Chem. A 122, 8665–8673 (2018).

Kurten, T. et al. Alkoxy radical bond scissions explain the anomalously low secondary organic aerosol and organonitrate yields from alpha-pinene + NO3. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 2826–2834 (2017).

Praske, E. et al. Atmospheric autoxidation is increasingly important in urban and suburban North America. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 64–69 (2018).

Orlando, J. J. & Tyndall, G. S. Laboratory studies of organic peroxy radical chemistry: an overview with emphasis on recent issues of atmospheric significance. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 6294–6317 (2012).

Berndt, T. et al. Accretion Product Formation from Self- and Cross-Reactions of RO2 Radicals in the Atmosphere. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl. 57, 3820–3824 (2018).

Molteni, U. et al. Formation of highly oxygenated organic molecules from α-pinene ozonolysis: chemical characteristics, mechanism, and kinetic model development. ACS Earth Space Chem. 3, 873–883 (2019).

Heinritzi, M. et al. Molecular understanding of the suppression of new-particle formation by isoprene. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 11809–11821 (2020).

McFiggans, G. et al. Secondary organic aerosol reduced by mixture of atmospheric vapours. Nature 565, 587–593 (2019).

Berndt, T. et al. Accretion product formation from ozonolysis and OH radical reaction of α-pinene: mechanistic insight and the influence of isoprene and ethylene. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 11069–11077 (2018).

Dada, L. et al. Role of sesquiterpenes in biogenic new particle formation. Sci. Adv. 9, eadi5297 (2023).

Shen, H. R. et al. Unexpected significance of a minor reaction pathway in daytime formation of biogenic highly oxygenated organic compounds. Sci. Adv. 8, eabp8702 (2022).

Pye, H. O. T. et al. Anthropogenic enhancements to production of highly oxygenated molecules from autoxidation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 6641–6646 (2019).

Nie, W. et al. NO at low concentration can enhance the formation of highly oxygenated biogenic molecules in the atmosphere. Nat. Commun. 14, 3347 (2023).

Baker, Y. et al. Impact of HO2/RO2 ratio on highly oxygenated α-pinene photooxidation products and secondary organic aerosol formation potential. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 4789–4807 (2024).

Roldin, P. et al. The role of highly oxygenated organic molecules in the Boreal aerosol-cloud-climate system. Nat. Commun. 10, 15 (2019).

Pichelstorfer, L. et al. Towards automated inclusion of autoxidation chemistry in models: from precursors to atmospheric implications. Environ. Sci.Atmos. 4, 879–896 (2024).

Berndt, T. et al. Hydroxyl radical-induced formation of highly oxidized organic compounds. Nat. Commun. 7, 13677 (2016).

Bianchi, F. et al. Highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOM) from gas-phase autoxidation involving peroxy radicals: a key contributor to atmospheric aerosol. Chem. Rev. 119, 3472–3509 (2019).

Riva, M. et al. Evaluating the performance of five different chemical ionization techniques for detecting gaseous oxygenated organic species. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 12, 2403–2421 (2019).

Roldin, P. et al. Modelling non-equilibrium secondary organic aerosol formation and evaporation with the aerosol dynamics, gas- and particle-phase chemistry kinetic multilayer model ADCHAM. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 7953–7993 (2014).

Schervish, M. & Donahue, N. M. Peroxy radical chemistry and the volatility basis set. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 1183–1199 (2020).

Schervish, M. & Donahue, N. M. Peroxy radical kinetics and new particle formation. Environ. Sci. Atmos. 1, 79–92 (2021).

Zhao, B. et al. Impact of Urban Pollution on Organic-Mediated New-Particle Formation and Particle Number Concentration in the Amazon Rainforest. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 4357–4367 (2021).

Weber, J. et al. CRI-HOM: A novel chemical mechanism for simulating highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOMs) in global chemistry-aerosol-climate models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 10889–10910 (2020).

Cai, R. et al. Survival probability of new atmospheric particles: closure between theory and measurements from 1.4 to 100 nm. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 14571–14587 (2022).

Quelever, L. L. J. et al. Effect of temperature on the formation of highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOMs) from alpha-pinene ozonolysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 7609–7625 (2019).

Cheng, X. et al. Atmospheric isoprene and monoterpenes in a typical urban area of Beijing: Pollution characterization, chemical reactivity and source identification. J. Environ. Sci. 71, 150–167 (2018).

Noe, S. M. & Huve, K. Niinemets u, Copolovici L. Seasonal variation in vertical volatile compounds air concentrations within a remote hemiboreal mixed forest. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 3909–3926 (2012).

Saxton, J. E. et al. Isoprene and monoterpene measurements in a secondary forest in northern Benin. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7, 4095–4106 (2007).

Yu, J. Z. et al. Observation of gaseous and particulate products of monoterpene oxidation in forest atmospheres. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 1145–1148 (1999).

Zannoni, N. et al. Surprising chiral composition changes over the amazon rainforest with height, time and season. Commun. Earth Environ. 1, 11 (2020).

Kenagy, H. S., Heald, C. L., Tahsini, N., Goss, M. B. & Kroll, J. H. Can we achieve atmospheric chemical environments in the laboratory? an integrated model-measurement approach to chamber SOA studies. Sci. Adv. 10, 09–13 (2024).

Suda, S. R. et al. Influence of functional groups on organic aerosol cloud condensation nucleus activity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 10182–10190 (2014).

Kawecki, S. & Steiner, A. L. The influence of aerosol hygroscopicity on precipitation intensity during a mesoscale convective event. J. Geophys Res-Atmos. 123, 424–442 (2018).

Pankow, J. F. & Asher, W. E. SIMPOL.1: a simple group contribution method for predicting vapor pressures and enthalpies of vaporization of multifunctional organic compounds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 2773–2796 (2008).

Wei, J. L. et al. Superoxide formation from aqueous reactions of biogenic secondary organic aerosols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 260–270 (2021).

Zhang, Z. H. et al. Are reactive oxygen species (ROS) a suitable metric to predict toxicity of carbonaceous aerosol particles?. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 1793–1809 (2022).

Rothfuss, N. E. & Petters, M. D. Influence of functional groups on the viscosity of organic aerosol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 271–279 (2017).

Breitenlechner, M. et al. PTR3: An Instrument for Studying the Lifecycle of Reactive Organic Carbon in the Atmosphere. Anal. Chem. 89, 5825–5832 (2017).

Long, B., Bao, J. L. & Truhlar, D. G. Reaction of SO2 with OH in the atmosphere. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 8091–8100 (2017).

Junninen, H. et al. A high-resolution mass spectrometer to measure atmospheric ion composition. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 3, 1039–1053 (2010).

Ehn, M. et al. Gas phase formation of extremely oxidized pinene reaction products in chamber and ambient air. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 5113–5127 (2012).

Damian, V., Sandu, A., Damian, M., Potra, F. & Carmichael, G. R. The kinetic preprocessor KPP - a software environment for solving chemical kinetics. Comput Chem. Eng. 26, 1567–1579 (2002).

Nie W. A mechanistic understanding of the varying yields of highly oxygenated organic molecules. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30146215.v1 (2025).

Donahue, N. M., Epstein, S. A., Pandis, S. N. & Robinson, A. L. A two-dimensional volatility basis set: 1. organic-aerosol mixing thermodynamics. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 3303–3318 (2011).

Epstein, S. A., Riipinen, I. & Donahue, N. M. A semiempirical correlation between enthalpy of vaporization and saturation concentration for organic aerosol. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 743–748 (2010).

Huang, W. et al. Measurement report: Molecular composition and volatility of gaseous organic compounds in a boreal forest – from volatile organic compounds to highly oxygenated organic molecules. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 8961–8977 (2021).

Bates, K. H., Burke, G. J. P., Cope, J. D. & Nguyen, T. B. Secondary organic aerosol and organic nitrogen yields from the nitrate radical (NO3) oxidation of alpha-pinene from various RO2 fates. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 22, 1467–1482 (2022).

Zhao, J. et al. A combined gas- and particle-phase analysis of highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOMs) from α-pinene ozonolysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 3707–3730 (2023).

Perakyla, O. et al. Experimental investigation into the volatilities of highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOMs). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 649–669 (2020).

Zhang, X. et al. Formation and evolution of molecular products in alpha-pinene secondary organic aerosol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 14168–14173 (2015).

Qi, L., Nakao, S. & Cocker, D. R. Aging of secondary organic aerosol from alpha-pinene ozonolysis: Roles of hydroxyl and nitrate radicals. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 62, 1359–1369 (2012).

Pathak, R. K., Stanier, C. O., Donahue, N. M. & Pandis, S. N. Ozonolysis of alpha-pinene at atmospherically relevant concentrations: Temperature dependence of aerosol mass fractions (yields). J. Geophys Res-Atmos. 112, 8 (2007).

Saathoff, H. et al. Temperature dependence of yields of secondary organic aerosols from the ozonolysis of alpha-pinene and limonene. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 1551–1577 (2009).

Zhao, D. F. et al. Secondary organic aerosol formation from hydroxyl radical oxidation and ozonolysis of monoterpenes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 991–1012 (2015).

Kristensen, K. et al. Dimers in alpha-pinene secondary organic aerosol: effect of hydroxyl radical, ozone, relative humidity and aerosol acidity. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 4201–4218 (2014).

Henry, K. M., Lohaus, T. & Donahue, N. M. Organic aerosol yields from alpha-pinene oxidation: bridging the gap between first-generation yields and aging chemistry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 12347–12354 (2012).

Pommer, L., Fick, J., Andersson, B. & Nilsson, C. The influence of O3, relative humidity, NO and NO2 on the oxidation of α-pinene and Δ3-carene. J. Atmos. Chem. 48, 173–189 (2004).

Jonsson, Å, Hallquist, M. & Ljungström, E. The effect of temperature and water on secondary organic aerosol formation from ozonolysis of limonene, Δ3-carene and α-pinene. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 6541–6549 (2008).

Bell, D. M. et al. Effect of OH scavengers on the chemical composition of α-pinene secondary organic aerosol. Environ. Sci. Atmos. 3, 115–123 (2023).

Jensen, L. N. et al. Temperature and volatile organic compound concentrations as controlling factors for chemical composition of α-pinene-derived secondary organic aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 11545–11562 (2021).

Kristensen, K. et al. High-molecular weight dimer esters are major products in aerosols from α-pinene ozonolysis and the boreal forest. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 3, 280–285 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank CERN-CLOUD for providing experimental data. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) project (42220104006), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3706302), the Jiangsu Province Outstanding Youth Fund (BK20240067), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20231513), the Jiangsu Provincial Collaborative Innovation Center of Climate Change and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, the Swedish Research Council VR (project no. 2019-05006), Swedish Research Council FORMAS (project no. 2018-01745), US National Science Foundation (CHE-2336463).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.N. and C.Y. designed the study. L.Y performed model simulations and analyzed the data. W.N., C.Y., M.E, Y.L., P.R., X.Q., V.M.K., N.M.D., D.W., M.K. and A.D. are acknowledged for valuable discussions. L.Y., W.N. and C.Y. wrote the manuscript. M.E., V.M.K. and N.M.D. contributed to editing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing Interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Simon O’Meara and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, L., Nie, W., Yan, C. et al. A mechanistic understanding of the varying yields of highly oxygenated organic molecules. Nat Commun 17, 302 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67007-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67007-w