Abstract

Inorganic electrolytes dominate all-solid-state batteries (ASSBs), but face critical limitations, including interfacial instability, complex manufacturing, and challenges in operating under commercially viable conditions. Here, we present a transformative approach using zwitterionic dry polymer electrolytes (ZPEs) designed via a conflicting entropy strategy to enable scalable energy-dense ASSBs. Guided by Flory–Huggins theory, liquid-state zwitterionic monomers exhibit higher mixing entropy with Li salts compared to conventional long-chain polymers, forming homogeneous monomer/salt mixtures with enhanced intermolecular electrostatic interactions to promote salt dissociation. In situ polymerization of these mixtures yields directionally aligned ion channels decoupled from the polymer backbone, characterized by reduced conformational entropy, allowing rapid Li⁺ migration via an ion-hopping mechanism under ambient conditions. The ZPEs are seamlessly incorporated as a solid catholyte into pre-fabricated high-areal-capacity (10.0 mAh cm⁻²) LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 positive electrodes, ensuring compatibility with existing cell manufacturing processes and has the potential to reduce production complexity and cost. Paired with thin Li-metal negative electrodes (N/P (negative-to-positive electrode capacity) ratio = 1.0), pouch-type ASSB full cells demonstrate a specific energy and energy density of 516 Wh kg−1 and 1329 Wh L−1 (excluding the pouch packaging) and stable cycle life at practical operating conditions (25 °C and 0.5 MPa) in such a constrained cell configuration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growing demand for high-performance all-solid-state batteries (ASSBs) underscores the urgent need for advanced solid ion conductors with high ionic conductivity, stable electrode interfaces, and scalable manufacturing compatibility1,2. Previous studies on solid Li+ conductors have mostly focused on inorganic electrolytes such as sulfides and oxides3,4. However, despite their solid-state nature, high ionic conductivity, and ideal Li+ transference number (tLi+), the inorganic electrolytes still face persistent challenges, including interfacial and grain-boundary resistances, mechanical stiffness, and propensity for dendrite growth through interparticle voids5. Furthermore, their complex manufacturing processability and inability to operate under commercially viable conditions pose formidable challenges, due to the high-pressure/high-temperature requirements6,7.

Polymer electrolytes, on the other hand, offer advantages such as mechanical compliance, intimate interfacial contact with electrodes, and ease of preparation8. A critical challenge in the development of polymer electrolytes for ASSBs lies in their low ionic conductivity and inadequately structured Li⁺ transport channels9,10. Conventional strategies have typically focused on enhancing ion transport by lowering the glass transition temperature (Tg) and increasing free volume8,9,10. Numerous approaches have been implemented to overcome these limitations of polymer electrolytes, focusing on synthesis and engineering of new polymer structures11, functional additives12, and polymer-in-salt electrolytes13,14.

Although these approaches have led to improvement in ionic conductivity11,12,13,14, challenges persist with respect to the limited salt solubility, insufficient dissociation capability, random/reticulated ionic conduction pathways, and electrochemical destabilization caused by residual solvents. In addition, the thick layers of the polymer electrolytes lead to loss of cell energy density and inferior rate performance. Overcoming these challenges requires an innovative approach that goes beyond traditional polymer electrolyte design, leveraging the strategic engineering of molecular chemistry, intermolecular interactions, and microstructural architectures.

Here, we present a transformative approach to scalable energy-dense ASSBs by introducing a class of zwitterionic dry polymer electrolytes (ZPEs) designed via a conflicting entropy strategy. The ZPE exhibits enhanced electrochemical performance and manufacturing compatibility, comparable to current benchmarks under commercially viable conditions and fulfilling critical requirements for practical energy storage applications. The conflicting entropy design (Fig. 1) synergistically integrates the enhanced Li salt dissociation via increased mixing entropy with the formation of aligned ion channels decoupled from the polymer backbones via reduced conformational entropy.

Unlike conventional long-chain polymers that require processing solvents, liquid-state zwitterionic monomers were mixed directly with Li salts without the use of processing solvents. Guided by the Flory-Huggins theory15, the zwitterionic monomers increased mixing entropy with Li salts, resulting in homogeneous liquid mixtures (referred to ZPE precursors). Consequently, intermolecular electrostatic interaction between the zwitterionic monomers and Li salts was enhanced, promoting the salt dissociation. Subsequent in situ thermal polymerization transformed the ZPE precursors into molecularly assembled zwitterionic units, forming directionally aligned ion channels decoupled from the polymer backbones. This molecularly assembled architecture, characterized by reduced conformational entropy and nanoscale ordering, contrasts with conventional solid polymer electrolytes that rely on coupled ion–polymer interactions and polymer segmental motion. Notably, this design embodies a nonconventional yet increasingly recognized paradigm, in which molecular ordering and self-assembled structures can enhance ion conductivity by enabling decoupled, fast-ion transport pathways. This concept is supported by recent advances in the polymer electrolyte field, which highlight molecular ordering and nanophase alignment as effective strategies to enhance ion conductivity16,17. In this context, the ZPE proposed in this study leverages the self-assembly of zwitterionic moieties to construct aligned ion-conduction pathways. This approach provides a rational design framework for advanced polymer electrolytes beyond the limits of conventional systems. Consequently, the resulting ZPE facilitates rapid Li⁺ migration via an ion-hopping mechanism under ambient conditions.

The ZPE was seamlessly incorporated as a solid catholyte into a pre-fabricated high-areal-capacity (10.0 mAh cm–2) LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (NCM811) positive electrodes, demonstrating scalable manufacturing compatibility with existing Li-ion battery (LIB) technologies while avoiding additional complexities. The ZPE catholyte-containing positive electrode was paired with a Li-metal negative electrode (10.0 mAh cm–2, N/P (negative-to-positive electrode capacity) ratio = 1.0) to fabricate a pouch-type ASSB full cell. The resulting full cell exhibited a specific energy and energy density of 516 Wh kg−1 and 1329 Wh L−1 (excluding the pouch packaging) and stable cycling performance under this constrained cell configuration at practical operating conditions (25 °C and 0.5 MPa).

Results

Increased entropy of mixing: enhancing Li salt dissociation

As a zwitterionic monomer (denoted as ZM), 3-(N-(perfluoroalkylsulfonyl)propryl)−1-undecylacrylate-pyrrolidinium was synthesized (Supplementary Fig. 1). To identify the most suitable Li salt for achieving high ionic conductivity in the resulting ZPEs, a total of eight representative anions (SO₄²⁻, Cl⁻, Br⁻, BF₄⁻, PF₆⁻, FSI⁻, TFSI⁻, and BETI⁻) were systematically evaluated through theoretical and experimental evaluations (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). Specifically, electrostatic potential (ESP) mapping was performed to assess charge delocalization characteristics of each anion, which provides insights into the expected Li⁺–anion interaction strength. In parallel, the surface area-to-volume (SA/V) ratio was calculated as a descriptor of ionic interaction efficiency: smaller anions generally exhibit higher SA/V ratios, indicating stronger coulombic binding to Li⁺. Among the anions examined, BETI⁻ (bis(pentafluoroethanesulfonyl)imide), possessing the lowest SA/V ratio (1.27) and a highly delocalized charge distribution, was predicted to exhibit the weakest electrostatic interaction with Li⁺. Furthermore, BETI⁻ showed the lowest calculated Li⁺ dissociation energy (119.81 kcal mol⁻¹), confirming its enhanced dissociation capability. Experimentally, BETI⁻ delivered the highest ionic conductivity (3.8 × 10⁻4 S cm⁻1 at 25 °C) among the tested salts, further validating its effectiveness in promoting salt dissociation and compatibility with the zwitterionic matrix. These theoretical and experimental results support the selection of BETI⁻ as the optimal anion for enhancing ionic conductivity in ZPEs. The liquid-state ZM was mixed with the LiBETI in the absence of any processing solvents, followed by in situ thermal polymerization at 120 °C to obtain the solid-state ZPE (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 4). The thermal stability of the resulting ZPE was evaluated via thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), as presented in Supplementary Fig. 5. The material exhibited negligible weight loss up to 300 °C, indicating its high thermal robustness. Moreover, the absence of mass loss suggests that the ZPE is free of residual volatile components and unreacted monomers. The optimal composition ratio of the ZM/LiBETI was determined to be 1.0/1.5 (mol/mol) based on the ionic conductivity analysis at various temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 6). Increasing the LiBETI concentration beyond this ratio led to a decline in ionic conductivity, revealing a non-monotonic trend arising from the interplay of multiple physicochemical factors. At elevated LiBETI concentrations, saturation of zwitterionic coordination sites promotes the formation of ionic aggregates or salt-rich nanodomains, reducing the population of mobile Li-ions and disrupting percolating conduction pathways. When the salt content exceeds its solubility limit within the polymer matrix, crystallite formation and nanoscale structural inhomogeneities may also occur, further impeding long-range ion transport13,14. This behavior is further corroborated by the molar ionic conductivity (sm = σ/c) observed in Supplementary Fig. 6b, which is consistent with previous reports18,19 on solvent-free polymer electrolytes exhibiting distinct ion transport regimes depending on salt concentration.

The beneficial effect of the ZM on the mixing efficiency with LiBETI was investigated. For comparative analysis, a zwitterionic polymer (denoted as ZP) was selected as a control sample due to its identical chemical structure to the ZM, with the only difference being the molecular weight, which significantly affects the mixing entropy as predicted by the Flory-Huggins theory15. The ZP was prepared by the thermal polymerization of the ZM (Supplementary Fig. 7). The resulting ZP was then dissolved in DMF solvent and then mixed with LiBETI in the same composition ratio as the aforementioned ZM/LiBETI. The Gibbs free energies of mixing \(\Delta ({G}_{{{\rm{Mix}}}})\) of two mixtures are determined by both enthalpic (\(\Delta {H}_{{{\rm{Mix}}}}\)) and entropic (\(\Delta {S}_{{{\rm{Mix}}}}\)) contributions to mixing, as described in Eq. (1);

It is known that the overall enthalpy of polymer systems can increase with molecular weight mainly due to chain entanglement and bulk-phase interactions20,21. In this study, our focus was placed not on the macroscopic enthalpy of the entire polymer network, but rather on the local enthalpic interactions between Li⁺ and the zwitterionic moiety at the level of individual repeating units. This approach is consistent with previous reports22,23, which reported that enthalpic contribution relevant to ion coordination is determined by the chemical structure of the repeating unit.

Since the enthalpic contribution is similar for each system, the entropic contribution dominates the Gibbs free energy of mixing. To estimate the entropic contribution to mixing, the energy of mixing (\(\Delta {E}_{{{\rm{Mix}}}}\)) for the two mixtures were calculated using an Eq. (2) based on the Flory–Huggins theory24;

where \(\Delta {E}_{{{\rm{Mix}}}}\) represents the energy of mixing, \(\varPhi\) denotes the volume fraction, \({E}_{{{\rm{coh}}}}\), is the cohesive energy, and \(V\) is the molar volume. The cohesive energy refers to the energy required to overcome all intermolecular forces within a pure substance, separating its molecules to infinite distance. It serves as a measure of the internal cohesion of a material and provides insight into the strength of intermolecular interactions. In polymer–salt systems, cohesive energy is commonly used to estimate mixing energy, which represents the net energetic change upon mixing two species and serves as an indicator of their thermodynamic miscibility25,26. In this study, the mixing energy was calculated by subtracting the sum of the cohesive energies of the individual components (ZM, ZP, and LiBETI) from the cohesive energies of their mixtures. A more negative mixing energy indicates stronger intermolecular interactions and thus greater thermodynamic compatibility between the components. The ZM/LiBETI showed a more negative mixing energy (–7.50 \(\times\) 107 J m–3) compared to the ZP/LiBETI (–6.38 \(\times\) 107 J m–3), indicating the thermodynamic preference for achieving a uniform mixture (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 8a). To further elucidate the structural difference between the ZM/LiBETI and ZP/LiBETI, their free volume ratios (=free volume/total volume) were compared (Supplementary Fig. 8b). When a uniform distribution between the components is possible, the free volume ratio decreases because the components can be packed closely together without aggregation27. The free volume ratio was observed to be 13% for the ZM/LiBETI and 26% for the ZP/LiBETI. This significant reduction in the free volume in the ZM/LiBETI verifies the uniform distribution of dissociated LiBETI.

a Free energy of mixing (ΔEMix) of ZM/LiBETI (vs. ZP/LiBETI (control sample)) estimated using DFT calculation. b, c BF-STEM image (b) and linear scanning EDS (N element originated from the ZPE) mapping images (c) of the ZPE (vs. ZP/LiBETI), where the inset is a cross-sectional FE-SEM image of ZPE. d LSCM surface topography images of the ZPE (vs. ZP/LiBETI). e XRD profiles of the ZPE (vs. ZP/LiBETI). f Ionic conductivity of the ZPE (vs. ZP/LiBETI) at 25 °C. g Fraction of the Li+ CN in the ZPE (vs. ZP/LiBETI). h MSD analysis and DLi+ of the ZPE (vs. ZP/LiBETI).

To verify this theoretical comparison, we examined morphologies of the ZPE (obtained after in situ polymerization of the ZM/LiBETI) and ZP/LiBETI. The bright-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (BF-STEM) images revealed that the ZPE showed a homogeneous dispersion state, whereas the ZP/LiBETI suffered from random and local aggregation (Fig. 2b). In addition, the energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis revealed the uniform distribution of N element throughout the entire region of the ZPE compared to the ZP/LiBETI (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 9). This improved dispersion state of the ZPE was confirmed by conducting laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) analysis that can map the surface roughness. The ZP/LiBETI showed a large height deviation, indicating the nonuniform dispersion of the electrolyte components (Fig. 2d). In contrast, the height deviation of the ZPE was negligible over the wide range of the scanned area. This result demonstrates the viable role of the ZM in regulating the dispersion state in the ZPE. To evaluate the degree of LiBETI dissociation in the ZPE, X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were conducted. While the XRD pattern of the ZPE exhibits no discernible crystalline reflections (Fig. 2e), the ZP/LiBETI sample displays distinct diffraction peaks at 23.1°, 32.6°, and 40.0° (Supplementary Fig. 10), indicating that LiBETI is not fully dissociated and retains multiple crystalline domains within the polymer matrix. These results collectively underscore the efficiency of ZM in promoting the uniform dispersion and enhanced dissociation of LiBETI in the ZPE.

Based on this structural understanding of the ZPE, its ionic transport properties were compared with those of the ZP/LiBETI. The ZPE showed higher ionic conductivity (σ = 0.38 mS cm–1) compared to the ZP/LiBETI (\(\sigma\) = 0.12 mS cm–1; Fig. 2f). This improved ionic conductivity of the ZPE was theoretically elucidated through molecular dynamics (MD) simulation (Supplementary Fig. 11). The coordination number (CN) of the Li+−BETI– complex (originating from the LiBETI) in ZPE decreased by 17.7% and the CN of the Li+−TFSI– complex (from the ZPE) increased by 147.8% compared to those of the ZP/LiBETI. This finding suggests the enhanced dissociation of LiBETI, followed by a more favorable Li+ coordination with the TFSI– of the zwitterionic unit in the ZPE.

A detailed analysis of the CN of the Li+−TFSI– complex was conducted (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 12). The ZPE showed a larger proportion of higher CN (>2), whereas the lower CN (=1) was predominantly observed in the ZP/LiBETI, underscoring the promoted salt dissociation enabled by the zwitterionic unit. Furthermore, the mean square displacement (MSD) analysis revealed a higher Li+ diffusion coefficient (DLi+ = 23.0 Å2 μs–1) for the ZPE compared to that of the ZP/LiBETI (8.9 Å2 μs–1) (Fig. 2h). This result suggests that the ions in the ZPE may migrate by a different conduction mechanism compared to those of traditional long-chain polymer-based solid electrolytes, which will be discussed in detail in the following sections. Meanwhile, the ZPE showed nonflammability when subjected to a flame test (Supplementary Movie 1), highlighting its potential role in enhancing the safety of the resulting ASSBs.

Molecular design of anionic group in zwitterionic units

The anionic group of the zwitterionic unit in the ZPE was rationally designed, with a focus on optimizing the intermolecular interaction of anionic group−Li+. In addition to the TFSI– described above, sulfonate (SO3–) was selected as a control system (Supplementary Fig. 13) by considering its electrostatic potential (ESP) and highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) energy level values for comparative analysis. The chemical structures of the anionic groups in the zwitterionic units, as well as their ESP values estimated from the DFT calculation, are shown in Fig. 3a. The absolute ESP value of TFSI– was lower than that of SO3–. This result indicates that TFSI– might have a weaker electrostatic attraction with Li+ (dissociated from the LiBETI salt), which was theoretically verified by calculating the intermolecular interaction energies of anion−Li+ (Fig. 3b).

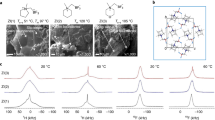

a Chemical structure (top) and MESP (bottom) of the ZMs with different anions (SO3– and TFSI–). The blue and red represent the electron-rich and electron-deficient regions, respectively. b Ion-ion interaction energies between the ZMs with different anions (SO3– and TFSI–) and Li+. c Snapshots showing the configuration and distance (Å) between Li+ and anionic moiety of the ZPE. Atoms are colored differently according to the element type: carbon (gray), nitrogen (blue), sulfur (yellow), hydrogen (white), oxygen (red), and fluorine (sky blue), respectively. d RDF analysis of ZM(TFSI−) (vs. ZM(SO3−))−Li+ in the ZPE. e, f WAXS (e) and solid-state 7Li NMR spectra (f) of the ZPE(TFSI–) (vs. ZPE(SO3–)). The inset shows the inversion-recovery plots obtained from the solid-state 7Li NMR analysis. g Li+ conductivity (\(\sigma\)Li+) as a function of temperature and activation energy (Ea) of the ZPE(TFSI–) (vs. ZPE(SO3–)).

In addition, the intermolecular distances between the anionic groups and Li+ were quantified using MD simulation (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 14). The TFSI–, owing to its bulkier size which facilitates charge delocalization, showed a longer intermolecular distance from Li+ compared to the SO3–. This structure analysis was correlated with the radial distribution function (RDF) between Li+ and the anionic moiety of ZM (Fig. 3d). The RDF of Li+ was examined as a function of intermolecular distance. For the ZM(TFSI–), the dominant peak position of the RDF was located at a longer distance compared to the ZM(SO3–), indicating that the Li+ could weakly interact with the ZM(TFSI–). This theoretical elucidation of the ZPEs was verified by analyzing wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) profiles (Fig. 3e). The experimental distances (q) between the anionic group−Li+ were measured to be 3.8 (TFSI–) and 3.0 Å (SO3–), respectively. This result is consistent with the theoretical calculation, indicating that the TFSI– of the zwitterionic unit interacts weakly with Li+ compared to the SO3–.

The local chemical environment of Li+ was investigated using 7Li nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Fig. 3f). Compared to the ZPE with SO3– (denoted as ZPE(SO3–)), the ZPE with TFSI– (ZPE(TFSI–)) showed a narrower width (indicating the faster mobility of free Li+) and downshift (revealing the enhanced dissociation of LiBETI) of the singlet 7Li peak28,29. This result was verified by conducting the inversion-recovery measurement (inset of Fig. 3f)28,29. A smaller T1 value (0.66 s) was observed for the ZPE(TFSI–) compared to the ZPE(SO3–) (0.84 s), indicating the accelerated Li+ mobility. This faster Li+ conduction of the ZPE(TFSI–) was confirmed by analyzing its ionic conduction behavior as a function of temperature (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Fig. 15, and Supplementary Table 1). Specifically, the ZPE(TFSI⁻) exhibited σ of 0.38 mS cm⁻1 and tLi⁺ of 0.78, resulting in σLi⁺ of 0.30 mS cm⁻1 at 25 °C. In contrast, the ZPE(SO₃⁻) exhibited σ of 0.08 mS cm⁻1 and tLi⁺ of 0.63, yielding a σLi⁺ of 0.05 mS cm⁻1 at 25 °C. These results demonstrate that the ZPE(TFSI⁻) supports more efficient Li⁺ transport than the ZPE(SO₃⁻).

Meanwhile, the ZPE(TFSI⁻) exhibited a wider electrochemical stability window, with an oxidation onset potential of approximately 4.93 V vs. Li/Li⁺, compared to the ZPE(SO₃⁻), which showed an onset potential of ~4.72 V, as determined by linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) using a carbon working electrode30 (Supplementary Fig. 16a). Although the absolute difference is ~0.2 V, this enhancement is meaningful for enabling stable operation with high-voltage positive electrode materials. Additionally, the leakage current of the cell with the ZPE(TFSI⁻) was lower than that of ZPE(SO₃⁻) over the whole range of charge voltages examined herein (Supplementary Fig. 16b), verifying its enhanced oxidative resilience. This improved electrochemical stability of ZPE(TFSI⁻) was also corroborated by DFT calculations showing a substantially lower HOMO energy level for ZM(TFSI⁻) (–6.48 eV) than for ZM(SO₃⁻) (–4.74 eV), indicating a greater resistance to oxidative degradation (Supplementary Fig. 16c and Supplementary Data 7, 8).

Reduced conformational entropy: facilitating Li+ migration

The molecular assembly of zwitterionic units occurs during the in situ thermal polymerization of the homogeneous, liquid-state precursor comprising ZM and LiBETI. The bulky and charge-delocalized nature of BETI⁻ leads to weak coordination with Li⁺, thereby facilitating salt dissociation and promoting uniform Li⁺ dispersion that supports a percolated ionic network within the zwitterionic matrix. Upon thermal polymerization at 120 °C, electrostatic interactions between adjacent zwitterionic units reduce their conformational freedom, which in turn promotes anisotropic molecular packing and the formation of directionally aligned ion channels that are decoupled from the polymer backbone. These ordered ion-conducting pathways, which are absent in the unpolymerized precursor state, enable rapid Li⁺ migration via an ion-hopping mechanism. The directionally aligned ion channels formed in the ZPE are characterized by reduced conformational entropy. The conformational entropy change of the ZPE was quantified using an Eq. (3), where \(\Delta {S}_{{{\rm{conf}}}}\) represents the conformational entropy change, \({k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}\) is the Boltzmann constant, \(R\) is the end-to-end distance of the configuration in the simulated system, \(N\) and \({b}_{0}\) are the number and size of the monomers31:

The ZP/LiBETI demonstrated a higher positive conformational entropy change (60.6 \(\times\) 10−23 J K–1), whereas the ZPE exhibited a negative conformational entropy change (−9.9 \(\times\) 10−23 J K–1) (Fig. 4a). The calculation details are provided in Supplementary Table 2. It is known that the reduction in the \(\Delta {S}_{{{\rm{conf}}}}\) of polymer electrolytes is attributed to the increased structural rigidity, which limits the conformational disorder of the polymer chains32,33. Therefore, the negative value of \(\Delta {S}_{{{\rm{conf}}}}\) in the ZPE is likely due to the formation of the ordered, aligned ion channels. It is expected that the orientation of ion channels restricts the conformational freedom of the polymer chains, reducing the end-to-end distance and limiting the number of possible configurations. In comparison, the ZP/LiBETI showed an increase in the \(\Delta {S}_{{{\rm{conf}}}}\), associated with the aggregation behavior, which is consistent with the inhomogeneous dispersion state shown in Fig. 2a–d.

a Calculated conformational entropy changes of the ZPE (vs. ZP/LiBETI). b C K-edge NEXAFS spectra of the ZPE at various X-ray incident angles (θ = 90o, 70o, and 45o, respectively). c HR-TEM image with the corresponding FFT pattern of the ZPE. d Ordered phase of the ZPE (vs ZP/LiBETI). e 7Li{19F} HETCOR MAS NMR spectra of the ZPE. f Walden plot of the ZPE (vs. previously reported electrolytes). g Comparison in the Li+ conductivity between the ZPE and previously reported solvent-free solid polymer electrolytes.

To verify this theoretical elucidation of the ZPE, the near edge X-ray absorption fine structure (NEXAFS) spectra of the ZPE were measured at the X-ray incident angles (θ = 90o, 70o, and 45o, respectively) under electric field. The ZPE exhibited a significant angular dependence at 288.3 and 293.2 eV, indicating an anisotropic feature in the electronic structure of the ZPE (Fig. 4b). It is known that the difference in the IC–C/IC–H intensity ratios between various angles in the NEXAFS spectra increases as the degree of ion channel alignment becomes more pronounced34. The ZP/LiBETI showed the IC–C/IC–H intensity ratios of 0.87 (at 45°) and 0.71 (at 90°) (Supplementary Fig. 17a), yielding an intensity difference (\(\Delta\)I) of 0.16 (Supplementary Fig. 17b). In contrast, the ZPE showed an ∆I of 0.39, with IC–C/IC–H intensity ratios of 0.93 at 45° and 0.54 at 90°, approximately twice that of the ZP/LiBETI. This result indicates that although the ZP/LiBETI shows some degree of alignment under an electric field, it is less pronounced compared to the ZPE, underscoring the enhanced ability of the zwitterionic units in the ZPE to form highly aligned ion channels. Meanwhile, another control sample consisting of polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA)/LiBETI, devoid of zwitterionic units, showed no significant angular variation (Supplementary Fig. 17c), revealing that neutral monomers, such as PEGDA, do not form aligned channels even under the same conditions. Furthermore, PEGDA/LiBETI exhibited a very low ionic conductivity of 3.1 × 10⁻5 S cm⁻1 at 25 °C (Supplementary Fig. 18), underscoring its limited ion transport capability compared to the zwitterion-based system. These results demonstrate that the zwitterionic units of the ZPE could be molecularly assembled to form directionally aligned ion channels (Supplementary Fig. 17d).

This distinctive ion channel structure of the ZPE was further elucidated by conducting high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) and the corresponding fast-Fourier-transform (FFT) pattern analysis. The coexistence of both ordered and amorphous regions was observed in the ZPE (Fig. 4c). In addition, the crystallinity, defined as the ratio of ordered region across the whole sample volume in the ZPE and ZP/LiBETI, was quantitatively analyzed from 13C longitudinal relaxation time (T1) measured by cross-polarization (CP)-T1 method (Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20)35. Based on the assumption that the alignment and ordering of the side chains contribute to the formation of the ordered phase in the ZPE, the variation in intensity of the 13C{1H} CP magic angle spinning (MAS) NMR signal from the side chains was used to calculate the crystallinity. The ordered phase in the ZPE was estimated to be 54%, which was higher than that (16%) of a ZP/LiBETI and that (26%) of the crystallinity16 of the previously reported semi-crystalline solid electrolyte (Fig. 4d). This result confirms the presence of a significant fraction of ordered phase in the ZPE.

The Li+ conduction mechanism of the ZPE was investigated using 2D 7Li{19F} heteronuclear correlation (HETCOR) NMR analysis (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 21). The HETCOR NMR technique is known to reveal spatial correlations between species that are close in space (<0.5–1 nm), thereby shedding light on the association/dissociation and interaction between ionic species36. In the ZPE, two Li+ environments could be identified as follows: (i) Li−BETI, indicating the non-dissociated Li salt, and (ii) Li+−TFSI−, where Li+ is dissociated from LiBETI and interacts with the TFSI− end group of the ZPE. No correlation signal was observed between Li+ and −CF2−, whereas a correlation peak between Li+ and −CF3 group was detected. Given that the BETI− is composed of −CF2− and −CF3 groups, and the ZPE end group contains only −CF3 terminal, the detection of the correlation peak with −CF3 group signifies that Li+ dissociates from LiBETI and interacts with TFSI−, which is the side chain terminal of the ZPE.

To investigate the Li+ conduction mechanism of the ZPE, we measured the translational Li+ migration using pulsed field gradient NMR (PFG NMR) spectroscopy. By applying additional magnetic field gradients, molecules and ions were spatially encoded, allowing their positions after a diffusion time (Δ) to be decoded. The resulting NMR signal intensities were attenuated as a function of both diffusion time and field gradient. The diffusion coefficients (D) were extracted by fitting the signal decay to the Stejskal and Tanner Eq. (4)37:

where I is the observed intensity at given gradient strength, I0 is the intensity without a gradient, γ is the gyromagnetic ratio of the nuclei, δ is the gradient pulse length, and Δ is the diffusion time. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 22a, the signal attenuation curve of the ZPE did not follow a single exponential decay function, suggesting that Li+ dynamics occurred in a multiphase system with different diffusivities. Thus, the logarithmic signal intensity was analyzed as a multi-component system (Supplementary Fig. 22b), which revealed two distinct environments for Li+ conduction in the ZPE. Corresponding diffusion coefficients for each environment were extracted, with the fast Li+ attributed to the ordered phase (Dordered = 1.1×10⁻11 m2 s⁻1) and the sluggish Li+ to the amorphous phase (Damorphous = 9.1 × 10⁻13 m2 s⁻1) of the ZPE. Meanwhile, the 7Li NMR spectra of the ZP/LiBETI chosen as a control sample (Supplementary Fig. 23) revealed that the diffusivity of this system could not be measured due to the short T2 relaxation time and slow 7Li diffusion motion.

To corroborate the Li+ conduction phenomena of the ZPE, we calculated the DLi+ from MSD analysis (Supplementary Fig. 24). The average DLi+ in the ordered phase was estimated to be 183.3 Å2 μs–1, which is significantly higher than the DLi+ (23.0 Å2 μs–1) in the amorphous phase. This theoretical analysis demonstrates that the enhanced Li+ conduction can be achieved in the ordered phase with the aligned and decoupled ion channels. It is known that ordered ion channels of electrolytes are favorable for improving ionic conductivity due to the shortened tortuous paths16.

This unusual Li+ conduction behavior of the ZPE was further elucidated using the Walden plot (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 25), which is used to identify the relationship between the molar ionic conductivity (Λ) and the structural relaxation time (τg) of electrolytes38. For reference, the data38 of LiClO4-doped polyethylene oxide (PEO), dilute aqueous LiCl, and superionic ceramic (AgI)0.5-(AgPO3)0.5 electrolytes were also provided. Both the LiClO4-doped PEO and the dilute aqueous LiCl electrolyte showed typical Walden behavior with a linear slope of 1. In contrast, the Walden plot for the ZPE significantly exceeded the slope of 1, which is similar to the result of the superionic (AgI)0.5-(AgPO3)0.5 electrolyte based on an ion-hopping mechanism. This result suggests that Li+ conduction in the ZPE follows an ion-hopping mechanism via a similar mechanism through its aligned and decoupled ion channels. This ion transport behavior of the ZPE differs from those of conventional polymer electrolytes, which have random and intertwined ion channels that are strongly associated with the segmental motion of polymer chains.

Driven by this favorable ion transport behavior (enabled by the coupled effect of the high Li+ dissociation and aligned ion channels that are decoupled from the polymer backbones), the ZPE exhibited high Li+ conductivities (0.30 and 0.88 mS cm–1 at 25 and 60 °C, respectively), far exceeding those of previously reported solvent-free solid polymer and composite electrolytes (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Table 3)13,16,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52.

Enabling scalable high-energy-density ASSB full cells

The critical current density (CCD) represents the threshold current at which short-circuiting occurs due to dendritic Li propagation, thus reflecting the interfacial stability between Li metal negative electrode and electrolytes28. Supplementary Fig. 26 shows Li plating/stripping profiles of the ZPE and ZP/LiBETI as a function of current density, in which the applied current density was increased from 0.1 to 2.5 mA cm−2 with a step increase of 0.1 mA cm−2 h−1 (0.5 h stripping and 0.5 h plating). The ZPE showed a higher CCD (2.4 mA cm−2 ± 0.04) than the ZP/LiBETI (1.2 mA cm−2 ± 0.06). The electrochemical sustainability of the ZPE in contact with the Li-metal negative electrode was investigated using a Li | |Li symmetric cell at a current density of 0.2 mA cm–2 and a capacity of 0.2 mAh cm–2 (Fig. 5a). The ZPE exhibited enhanced Li plating/stripping cyclability compared to the control sample (ZP/LiBETI). Furthermore, even at a higher current density of 1.0 mA cm−2, the ZPE still exhibited the stable Li plating/stripping cycling behavior (Supplementary Fig. 27). This result was verified by analyzing the structural change of the Li-metal negative electrode after the cycling test (200 h). A dense and uniform surface morphology was observed on the cycled Li-metal negative electrode assembled with the ZPE, whereas the control sample showed random and needle-like Li dendrites (Supplementary Fig. 28). The cycled Li-metal negative electrode with the ZPE showed the formation of a thin and uniform solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer (~9 nm), while those with ZP/LiBETI showed a thick SEI layer (~20 nm) (Supplementary Fig. 29). In addition, the SEI layers were further analyzed using X-ray photoelectron microscopy (XPS) analysis on the Li||Li symmetric cell with the ZP/LiBETI to investigate the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layers. The XPS analysis of the cycled Li-metal anodes showed distinct differences in the composition and distribution of the SEI layers between ZPE and ZP/LiBETI. Since the elements and composition ratios of the ZPE were identical to those of the ZP/LiBETI, the difference in the SEI could be attributed to the enhanced dissociation of Li salts and the formation of directionally aligned and decoupled ion channels due to the molecular assembly of zwitterionic units in the ZPE. The cycled Li-metal negative electrode with the ZP/LiBETI exhibited a large content of organic elements (as indicated by the presence of C and O) (Supplementary Figs. 30 and 31). In contrast, the cycled Li-metal negative electrode with the ZPE showed a high content of inorganic elements over a wide range of etching time, accompanied by the formation of LiF-rich components. It is known that the LiF-rich SEI layer can mitigate undesirable interfacial side reactions with electrolytes, thus beneficially contributing to the cycle life53,54.

a Voltage profiles of the Li||Li symmetric cells with ZPE (vs. ZP/LiBETI) at a current density of 0.2 mA cm−2 and a capacity of 0.2 mAh cm−2. b LEIS area scan images of the cycled Cu foils assembled with ZPE (vs. ZP/LiBETI) in the asymmetric Cu||Li symmetric cells after 20 cycles. c Rate capability of the Li‖NCM811 (areal capacity = 2.5 mAh cm–2) cells with ZPE (vs. ZP/LiBETI), in which the discharge current densities were varied from 0.25 mA cm−2 (=0.1 C) to 2.0 mA cm−2 (=5.0 C) at a fixed charge current density of 0.25 mA cm−2. d–f Charge/discharge profiles of the ASSBs (n-ZPE as an ion-conducting separator and ZPE as a solid catholyte) with different positive electrodes (areal capacity = 4.0 mAh cm–2): Li‖NCM811 (d), Li‖LFP (e), and Li‖LLO (f) at a charge/discharge current density of 0.4 mA cm−2/0.4 mA cm−2 at 25 °C.

In addition, the local electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (LEIS) analysis29,55, which can quantitatively assess the uniformity of ionic topology, was performed (Fig. 5b). After the cycling test of the asymmetric Li | |Cu cells, the cycled Cu foil (after 20 cycles) assembled with ZPE exhibited uniform distribution of Rl,ct with a low average value of 231.4 Ω cm2 over its entire surface, whereas the control sample (ZP/LiBETI) showed a nonuniform distribution of Rl,ct with a high average value of 551.2 Ω cm2. This comparative analysis demonstrates the electrochemical viability of the ZPE in facilitating redox homogeneity at the Li-metal negative electrode interface. Owing to the enhanced ion transport kinetics of the ZPE described above, the cell with the ZPE achieved a higher discharge rate capability compared to the cell with the control sample (Fig. 5c).

To enable the development of scalable high-energy-density ASSB full cells, the ZPE was incorporated into an aramid nonwoven (thickness ~18 µm, porosity ~86%) to produce a mechanically robust, nonwoven-embedded ZPE (n-ZPE, thickness ~30 µm). The obtained n-ZPE showed Li+ conductivity (σ = 0.21 mS cm−1 at 25 °C, Supplementary Fig. 32), which was marginally different from that of the pristine ZPE (σ = 0.30 mS cm−1), indicating that the incorporation of the nonwoven support does not significantly compromise intrinsic ion transport. It should be noted that the Li+ conductance, rather than the Li+ conductivity, has a more pronounced impact on the electrochemical performance of practical ASSB full cells. Compared to the thick (100 μm) ZPE (Li+ conductance ~77.8 mS), the thin (30 μm) n-ZPE exhibited higher Li+ conductance (~182.3 mS, in Supplementary Fig. 33 and Supplementary Table 4), due to its reduced thickness. Notably, the Li+ conductance of n-ZPE also surpasses that of a 600 μm-thick inorganic Li₆PS₅Cl pellet (~45.8 mS), further underscoring its effectiveness in enhancing cell performance, particularly under high current densities. We also note that some early-stage electrochemical measurements (e.g., critical current density and rate tests in Fig. 5a–c) were conducted using the pristine ZPE to validate its electrochemical viability as an ion conductor. Meanwhile, the full-cell performance (Fig. 5d–f) was evaluated using n-ZPE to highlight its enhanced mechanical robustness and practical applicability in scalable ASSB full cells. The n-ZPE was assembled with a Li-metal negative electrode and a NCM811 positive electrode (areal capacity = 4.0 mAh cm–2) to fabricate an ASSB full cell. A cyclic voltammogram (CV) of the cell revealed the stable and reversible intercalation and deintercalation of Li+ into the NCM811 positive electrode (Supplementary Fig. 34). Subsequently, to explore its application versatility, the n-ZPE was paired with various positive electrode materials. The cells with the NCM811, LiFePO4 (LFP), and Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 (Li-rich layered oxide, LLO) showed normal charge/discharge profiles (NCM811: 199.3 mAh g–1, LFP: 148.3 mAh g–1, and LLO: 248.7 mAh g–1, respectively, Fig. 5d–f) and stable cycle retention (NCM811: 87.0% after 500 cycles, LFP: 86.8% after 1000 cycles, and LLO: 84.5% after 200 cycles, respectively, Supplementary Fig. 35). This result demonstrates the versatility of the n-ZPE and its potential as a platform solid electrolyte compatible with different positive electrode materials.

The introduction of high areal-capacity electrodes is essential for the development of high-energy-density full cells. However, most previously reported polymer electrolyte-based ASSB cells have been limited to the use of the low areal-capacity electrodes, thus failing to achieve high energy densities. To overcome this problem, first, we fabricated a high areal-capacity NCM811 positive electrode using a conventional slurry-cast method and then incorporated the ZPE in the pre-fabricated positive electrode as a solid catholyte, as shown in Fig. 6a. The liquid-state ZPE precursor, comprising ZM and LiBETI without any processing solvents, was incorporated into the pores of the pre-fabricated NCM811 positive electrode (15 × 15 (cm × cm)). Through in situ thermal polymerization (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 36), the precursor was transformed into a solid ZPE. This process demonstrates compatibility with existing LIB manufacturing processes, eliminating the need for additional infrastructure and reducing production complexity and cost.

a Fabrication of the ZPE (solid catholyte)-embedded positive electrode via infiltration of the ZPE precursor followed by in situ thermal polymerization. b Cross-sectional SEM images of the control PEO electrolyte (left) and ZPE-embedded NCM811 positive electrode (middle) with an EDS mapping image of N element (right). c Pore size distribution of the ZPE (vs. control PEO electrolyte)-embedded NCM811 positive electrode. d Charge/discharge profiles of the coin-type cell (Li-metal negative electrode||ZPE-embedded NCM811 positive electrode (areal capacity = 10.0 mAh cm–2) at a voltage range of 3.0–4.4 V and charge/discharge current density of 1.0 mA cm−2/1.0 mA cm−2. The cell performance was measured at 25 °C (ZPE) and 60 °C (ZPE and control PEO electrolyte), respectively. e Performance comparison of the ZPE (blue line) and the control PEO electrolyte (gray line). In the hexagon, the systems with higher overall performance were plotted on outermost. f Efficiency of capacity utilization (measured specific capacity of positive electrode materials/theoretical specific capacity of cathode materials) as a function of areal capacity (ZPE vs. control PEO electrolyte and previously reported polymer electrolytes). g Cycling performance of the pouch-type cell (Li-metal negative electrode||ZPE-embedded NCM811 positive electrode (areal capacity = 10.0 mAh cm–2), N/P ratio = 1.0) at charge/discharge current density of 1.0 mA cm−2/1.0 mA cm−2 and voltage range of 3.0–4.4 V. The cell performance was measured at 25 °C and 0.5 MPa. h Comparison of the ZPE and the previously reported polymer electrolytes in terms of four parameters: specific capacity of positive electrode materials (x-axis), areal capacity (y-axis), operating temperature (heatmap), and specific energy (diameter). The gray dashed lines represent the mass loading of the positive electrode materials. The number assigned to each circle corresponds to the serial number in Supplementary Table 7.

As a control sample for comparative analysis, a PEO/LiBETI solid electrolyte with the same composition ratio as the ZPE was prepared by dissolving the components in DMF. This control PEO solution was then incorporated into the pre-fabricated NCM811 positive electrode. However, unlike the ZPE precursor, which successfully filled the positive electrode pores, the control PEO solution failed to achieve full penetration (Fig. 6b, c). This difference is attributed to the disparity in viscosities between the two systems (123.8 cP for the ZPE precursor vs. 541.1 cP for the PEO solution; Supplementary Fig. 37). Meanwhile, to investigate whether extended infiltration time could improve pore penetration, the contact time for the control PEO solution was prolonged up to 12 h. Nevertheless, the control PEO solution still failed to fully infiltrate the porous positive electrode. During the extended exposure, the DMF solvent gradually evaporated, resulting in a substantial increase in the viscosity of the remaining PEO-rich solution. This not only hindered further infiltration but also led to the formation of a surface film that blocked access to deeper pores. In contrast, the ZPE precursor is a solvent-free liquid that remains stable over time. This allows for more uniform infiltration into the positive electrode pores. Moreover, the ZPE precursor does not require a solvent-drying step as it does not contain any processing solvents. In comparison, for the solidification of the control PEO electrolyte solution, its processing solvent needs to be removed after infiltration. Consequently, the ZPE precursor achieved comprehensive and intimate contact with the positive electrode active materials compared to the control PEO electrolyte solution.

Owing to these advantageous effects, the resulting ZPE (obtained from the in situ polymerization of the ZPE precursor) enabled the positive electrode to exhibit the higher specific capacity (approaching the theoretical specific capacity ( ~210.0 mAh gNCM811–1)29,55 of NCM811) at 60 oC compared to the positive electrode with the control PEO electrolyte (Fig. 6d). Moreover, the ZPE-containing positive electrode showed almost full utilization of the theoretical specific capacity even at a room temperature. The comparative performance of the ZPE over the control PEO electrolyte is delineated in Fig. 6e, with a focus on their electrochemical performance and manufacturing processability.

Such a favorable utilization of NCM811 in the ZPE-containing composite positive electrode was underscored by making a comparison with the previously reported polymer electrolytes as a function of the areal-mass-loading (Fig. 6f and Supplementary Table 5)13,46,47,51,52,53,54,55,56,57. Many previous works did not utilize high areal-mass-loading electrodes and showed the poor utilization of positive electrode materials in the composite positive electrode, revealing their limitation in achieving high-energy-density ASSB full cells. In contrast, the ZPE-containing composite positive electrode exhibited almost full capacity even at a higher mass loading value of 52 mg cm–2.

To evaluate the practical applicability, a pouch-type ASSB full cell was assembled using the n-ZPE as the ion-conducting separator and the ZPE as the solid catholyte (Supplementary Fig. 38). The pouch-type ASSB full cell, which incorporated an ZPE-embedded NCM811 positive electrode (4.0 mAh cm−2, comparable to those55,58 of commercial Li-ion battery positive electrode), exhibited stable capacity retention with cycling (85.4% after 200 cycles) at a high current density of 4.0 mA cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 39). Furthermore, a ZPE-containing NCM811 composite positive electrode with a higher capacity of 10.0 mAh cm–2 was fabricated and evaluated under a more constrained cell configuration (N/P ratio = 1.0). X-ray computed tomography (CT) analysis of the assembled full cell revealed the compact stacking of its component layers, ensuring seamless interfacial integration (Supplementary Fig. 40a). Under commercially viable operating conditions (25 oC and 0.5 MPa), the full cell exhibited a specific energy and energy density of 516 Wh kg−1 and 1329 Wh L−1 (excluding the pouch packaging, see Supplementary Table 6 for the calculation details) (Supplementary Fig. 40b). To address a concern on the long-term electrochemical stability of the ZPE in the NCM811 positive electrode, the cycled pouch-type ASSB full cell was disassembled after 150 cycles and the cycled Li-metal negative electrode was replaced with a fresh one. The reassembled ASSB full cell recovered its initial capacity (Fig. 6g), indicating that the capacity fading of the ASSB full cell is not due to the ZPE but mainly attributed to the degradation of the Li-metal negative electrode, which was consistent with the previously reported results54,58. Future work will focus on developing advanced Li-metal negative electrode capable of stable operation at higher current densities and optimizing cell engineering to achieve high-energy-density Li-metal full cells with robust cycle life.

A post-mortem analysis of the cycled NCM811 positive electrode with the ZPE was conducted using XPS depth profiles as a function of etching time. The CEI formed on the ZPE-containing NCM811 positive electrode exhibited a high content of inorganic elements (such as Li and F) over a broad range of etching time (Supplementary Fig. 41). It is known that the inorganic-rich CEI layer tends to suppress undesired interfacial side reactions with electrolytes54. To provide additional evidence, the structural stability of the cycled ZPE-embedded NCM811 positive electrode was characterized using high-resolution TEM (HR-TEM) and high-angle annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) analysis (Supplementary Fig. 42). For the cycled ZPE-embedded NCM811 positive electrode, the initial layered structure (R3̅m phase) was stably maintained in the bulk region (indicated by Region #1), while an NiO rock-salt structure (Fm3̅m phase) was observed in the thin outermost (~6 nm) region (Region #2).

To highlight the improved cell performance, the ZPE and previously reported solid electrolytes (including inorganic and polymeric) were compared (Fig. 6h and Supplementary Tables 5 and 7)6,51,56,59,60,61,62,63,64,65. Most of the previous solid electrolytes reported the energy densities under relatively mild measurement conditions, such as low specific capacities and areal-capacities (<160 mAh g–1 and <2.0 mAh cm−2), low utilization of electrode active materials (<90%), besides the need for high pressures and elevated temperatures. Consequently, their practical applications for ASSBs are lagging significantly behind, although some considerable progress in material chemistry and structural design for the solid electrolytes have been reported. In contrast, the pouch-type ASSB full cells with the ZPE exhibited high energy densities ( > 500 Wh kgcell−1) while fulfilling the requirements of high specific capacities and high areal capacities under practical operating conditions (25 oC and 0.5 MPa). This comparative analysis demonstrates the enhanced performance of the ZPE as a promising solid electrolyte for scalable high-energy-density ASSB full cells, indicating its potential applicability beyond conventional systems. Furthermore, its versatile design can be extended to other emerging systems based on post-Li chemistries.

Discussion

In summary, we have demonstrated the ZPE designed via a conflicting entropy strategy, enabling scalable energy-dense ASSBs that exceeded current benchmarks in manufacturing compatibility and electrochemical performance under commercially viable conditions. The ZPE precursor, composed of liquid-state zwitterionic monomers and Li salts, exhibited increased mixing entropy, facilitating Li salt dissociation. Subsequent in situ thermal polymerization formed directionally aligned ion channels decoupled from the polymer backbones, characterized by reduced conformational entropy. This synergistic design enabled the ZPE to exhibit fast Li⁺ conduction via an ion-hopping mechanism under ambient conditions. The ZPE was seamlessly embedded as a solid catholyte in the pre-fabricated high areal-capacity (10.0 mAh cm–2) NCM811 positive electrode, demonstrating good compatibility with existing LIB cell manufacturing processes. The resulting pouch-type ASSB full cell (Li-metal negative electrode||ZPE-containing NCM811 composite positive electrode, N/P ratio = 1.0) achieved a specific energy and energy density of 516 Wh kg−1 and 1329 Wh L−1 (excluding the pouch packaging) and stable cycle life under practical operating conditions (25 oC and 0.5 MPa). This cell performance demonstrates higher performance than previously reported ASSBs based on prevalent inorganic and polymer electrolytes, which have been limited by low areal-capacity electrodes and the need for high-pressure/high-temperature operation. By bridging the gap between laboratory innovation and industrial scalability, this ZPE design holds promise as a transformative platform over current state-of-the-art solid electrolytes, paving the way for the commercialization of high-energy, sustainable ASSBs.

Methods

Materials

Lithium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide (LiBETI) ( ≥ 99.9%), polyethylene oxide (PEO) (Mv = 600,000) and benzoyl peroxide (BPO) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI) (≥99.9%, LGES) was used as-received. Acryloyl chloride (>98%) and 1,3-propanesultone were purchased from TCI and used as received. Acetonitrile (MeCN) was dried over anhydrous K2CO3 and then distilled over CaH2. Deuterated NMR solvents were purchased from BK instrument (S. Korea) and used as received. All other chemicals and solvents were used as received.

Synthesis of the ZM(TFSI−) and ZM(SO3 −)

Potassium (3-chloropropylsulfonylperfluoroalkylsulfonyl)imide.

Synthetic procedures were performed following the previous reports. Trifluoromethanesulfonamide (5.000 g, 33.54 mmol) and K₂CO₃ (5.563 g, 40.25 mmol) were dissolved in H₂O (50 mL) and reacted at room temperature for 24 h. After the reaction was complete, the solvent was removed, and the residue was dissolved in acetone, filtered to remove the precipitate. The filtrate was concentrated by removing the solvent and then dried in a vacuum oven to obtain a white solid (5.458 g, 87%).

N-(11-hydroxyundecyl)pyrrolidine. Synthetic procedures were performed following the previous reports. To synthesize N-(11-hydroxyundecyl)pyrrolidine, pyrrolidine (2.123 g, 29.85 mmol), NaOH aqueous solution (50 wt.%, 2.388 g, 29.85 mmol), and 11-bromo-1-undecanol (5.000 g, 19.90 mmol) were combined in tetrahydrofuran (THF, 50 mL) and heated under reflux for 24 h. Upon completion, the mixture was cooled to room temperature, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was extracted three times with dichloromethane and water, and the collected organic phase was subsequently washed with deionized water and dried over anhydrous MgSO4. After filtration, the crude product was purified by brief silica-gel chromatography using THF as the eluent, yielding a white solid (4.516 g, 94%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C): δ 1.12 (m, 14H), 1.30 (m, 4H), 1.54 (m, 4H), 2.19 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 2.26 (s, 4H), 3.30 (t, J = 7 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3, 23 °C): δ 20, 23, 25, 26.4–27.0, 30. Potassium (3-chloropropylsulfonylperfluoroalkylsulfonyl)imide and N-(11-hydroxyundecyl)pyrrolidine were prepared as described in literature66,67.

N-(3-[1-(11-hydroxyundecyl)pyrrolidinium]propyl)sulfonyl)trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (OH-TFSI). A solution of potassium (3-chloropropylsulfonylperfluoroalkylsulfonyl)imide (5.00 g, 0.0152 mol) and N-(11-hydroxyundecyl)pyrrolidine (11.0 g, 0.0110 mol) in MeCN (30 mL) was refluxed for 50 h. After filtration, the filtrate solution was concentrated using a rotary evaporator, after which the residue was extracted three times with dichloromethane/water. The combined organic layer was washed with water and then dried over MgSO4. After the drying agent was filtered off, the filtrate solution was concentrated and then dried in a vacuum oven to obtain a white solid product (6.88 g, 91%). HR-MS (ESI): m/z 495.2165 ([M + H]+, calculated for C15H31N2O2 495.2174, error 1.82 ppm), 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, 23 oC): δ 1.25 (m, 14H), 1.39 (m, 2H), 1.64 (m, 2H), 2.04 (m, 6H), 3.08 (t, J = 7, 2H), 3.21 (m, 2H), 3.36 (m, 4H), 3.47 (m, 4H), 4.34 (t, J = 5, 1H). N-(3-[1-(11-acryloyloxyudecyl)pyrrolidinium]propyl)sulfonyl(trifluoromethanesulfonyl) imide (Ac-TFSI). A solution of OH-TFSI (4.00 g, 0.00809 mol), K2CO3 (4.47 g, 0.0324 mol) and acryloyl chloride (2.20 g, 0.0243 mol) in MeCN (15 mL) was stirred at 25 °C for 24 h under N2, after which the mixture was filtered. After filtration, the filtrate solution was concentrated using a rotary evaporator. After completion of the reaction, the residue was extracted three times with dichloromethane and water. The collected organic phase was rinsed with deionized water and dehydrated over anhydrous MgSO4. After the drying agent was filtered off, the filtrate solution was concentrated and dried in a vacuum oven to obtain a clear yellow liquid product (3.85 g, 87%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6, 23 oC): δ 1.26 (m, 14H), 1.59 (m, 2H), 1.64 (m, 2H), 2.04 (m, 6H), 3.08 (t, J = 7, 2H), 3.21 (m, 2H), 3.36 (m, 2H), 3.47 (m, 4H), 4.09 (t, J = 6.5, 2H), 5.93 (dd, 3J = 10, 2J = 1.4, 1H), 6.16 (dd, 3J = 16, 3J = 10, 1H), 6.31 (dd, 3J = 16, 2J = 1.4, 1H).

1-hydroxyundecyl-1-(propyl-3-sulfonate) pyrrolidinium (OH-SO3). A solution of 1,3-propanesultone (1.20 g, 0.00982 mol) and N-(11-hydroxyundecyl)pyrrolidine (4.74 g, 0.0196 mol) in MeCN (30 mL) was refluxed for 50 h and then filtered. After filtration, the filtrate solution was concentrated on a rotary evaporator. After completion of the reaction, the residue was extracted three times with dichloromethane and water. The collected organic phase was rinsed with deionized water and dehydrated over anhydrous MgSO4. After the drying agent was filtered off, the filtrate solution was concentrated and dried in a vacuum oven to obtain a white solid product (2.75 g, 77%). HR-MS (ESI): m/z 364.2509 ([M + H]+, calculated for C15H31N2O2 364.2522 error 3.57 ppm), 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O, 23 oC): δ 1.25 (m, 10H), 1.31 (m, 4H), 1.49 (m, 2H), 1.64 (m, 4H), 1.82 (m, 4H), 2.09 (m, 2H), 2.93 (t, J = 7, 2H), 3.25 (m, 2H), 3.33 (m, 4H), 3.41 (m, 2H), 3.54 (t, J = 6.5, 2H).

1-(11-acryloyloxyudecyl)−1-(propyl-3-sulfonate) pyrrolidinium (Ac-SO3). A solution of OH-SO3 (2.39 g, 0.00658 mol), K2CO3 (3.64 g, 0.0263 mol) and acryloyl chloride (1.79 g, 0.0197 mol) in MeCN (15 mL) was stirred at 25 °C for 24 h under N2 and then filtered. After filtration, the filtrate solution was concentrated on a rotary evaporator. After completion of the reaction, the residue was extracted three times with dichloromethane and water. The collected organic phase was rinsed with deionized water and dehydrated over anhydrous MgSO4. After the drying agent was filtered off, the filtrate solution was concentrated and dried in a vacuum oven to obtain a clear yellow liquid product (3.27 g, 91%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3, 23 oC): δ 1.26 (m, 10H), 1.33 (m, 4H), 1.66 (m, 4H), 2.11 (m, 2H), 2.21 (m, 2H), 2.38 (m, 2H), 2.98 (m, 2H), 3.22 (m, 2H), 3.60 (m, 4H), 3.75 (m, 2H), 4.14 (t, J = 7, 2H), 5.82 (dd, 3J = 10, 2J = 1.4, 1H), 6.11 (dd, 3J = 16, 3J = 10, 1H), 6.39 (dd, 3J = 16, 2J = 1.4, 1H).

Structural and physicochemical characterizations

Solid-state NMR experiments were performed on a Bruker NEO 600 spectrometer equipped with a 3.2 mm double resonance magic angle spinning (MAS) probe (DS101, at KBSI Metropolitan Seoul Center). The polymer film samples were cut into small pieces of approximately 1 mm in diameter and were packed into the 3.2 mm ZrO2 rotors. The 13C{1H} cross polarization (CP)-MAS spectra were acquired using ramped polarization transfer at an operating frequency of 150.88 MHz for 13C and 599.98 MHz for 1H. The experimental conditions were 1H 90°pulse length of 3.25 µs, contact time of 2 ms, and the repetition delay of 5 s. A MAS frequency of 17 kHz and Spinal-64 decoupling were used during acquisition. To characterize the crystalline and amorphous phases, 13C longitudinal relaxation times (T1) were measured using the CP−T1 pulse sequence35,68,69. Logarithmic signal intensity was plotted as a function of the variable time delay (t). When the experimental data deviated from a single exponential decay, the results were analyzed using a least-squares fitting approach with multiple components having distinct T1 values. The slope obtained from the fitting corresponds to −1/T1 for each phase, while the intercept reflects the mass fraction of polymer in each phase. The 2D 7Li{19F} HETCOR MAS NMR spectra were acquired using ramped polarization transfer at an operating frequency of 233.17 MHz for 7Li and 564.48 MHz for 19F with π-pulse decoupling during the acquisition. A 19F 90°pulse length of 3.30 µs, contact time of 2−8 ms, and a repetition delay of 3 s and MAS frequency of 16 kHz were used. For the sensitive detection, 256 increments were recorded in t1 using the States-TPPI method for phase-sensitive detection. Temperature calibrations performed with Pb(NO3)2 indicate that the real sample temperature was higher than the displayed temperature by 40 − 60 °C. All the experiments were performed under cooling-gas flow to set the temperature to the real temperature of 25 °C. Chemical shifts are referenced to tetramethylsilane (TMS) at 0 ppm, ammonium trifluoroacetate (ATF) at −72 ppm, adamantane at 38.4 ppm and 1 M lithium chloride aq. solution at 0 ppm for 1H, 19F, 13C, and 7Li, respectively.

To evaluate the Li+ diffusivity in the polymer, the PFG NMR measurements were performed on a Bruker Avance Neo 400 spectrometer, equipped with Diff50 high strength gradient probe (DS110 at KBSI Metropolitan Seoul Center). The ZPE was prepared as a film under an electric field and then cut into approximately 0.2 cm by 3 cm strips. Six layers of ZPE strips were stacked and placed inside in a 5 mm (o.d.) NMR tube. The self-diffusion coefficients from Li+ were determined from the echo signal attenuation of the 7Li NMR spectra. The stimulated echo pulse sequence (π/2 − π/2 − π/2), in which the magnetization returns along the z-axis during the time intervals between the second and third radio frequency pulses, was used to allow a relatively rather long diffusion time with reduced limitation of short T2 relaxation time. The gradient strength (g) was varied in 64 equal steps up to the maximum gradient strength of 28 T m−1. Multiple diffusion experiments with different diffusion times were performed to check whether the polymer electrolytes exhibited normal diffusion behavior. For the 7Li measurements, the diffusion time (Δ) of 30−70 ms and the gradient pulse length (δ) of 2.5 ms were used. All measurements were carried out at 25 °C.

The surface morphology and roughness of the solid polymer electrolyte membranes were characterized using a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSCM, Olympus OLS5000) equipped with a 405 nm semiconductor laser. Surface topography images were acquired in non-contact mode under ambient conditions, and measurements were performed at three different regions for each sample to ensure statistical reliability. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) measurements were conducted on a TA Instruments Q600 analyzer under a nitrogen atmosphere. The samples were heated from 30 to 600 °C at a heating rate of 5 °C min−1. The surface and cross-sectional morphologies of the electrodes were characterized by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, S-4800, Hitachi) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, JSM 6400, JEOL) operated at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. The microstructures were examined by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM, JEM-ARM200F “NEO ARM,” JEOL) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, JED-2300T (Dual), JEOL) at the Yonsei Center for Research Facilities, Yonsei University. HR-TEM and scanning TEM (STEM) analyses were performed at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were collected using a Rigaku MiniFlex600 diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). For the XRD analysis, XRD cells containing samples were mounted on an XRD diffractometer and measured at 40 kV and 15 mA. Synchrotron-based X-ray diffraction experiments were performed using an X-ray energy of 11.564 keV at the 6D UNIST-PAL beamline of the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory in Korea. Near edge x-ray absorption fine structure (NEXAFS) measurement in the total-electron-yield mode were conducted at the 4D PES beamline (base pressure: 2.5 × 10–10 Torr), at the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (PAL) in the Republic of Korea. The polarization ratio of this beamline was 0.8.

The chemical species formed on the cycled Li-metal anodes were analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ThermoFisher) with focused monochromatized Al Kα radiation. Based on the binding energy of C peak (248.8 eV), the XPS data were fitted and analyzed by Avantage software. To minimize air exposure and electron-beam-induced damage during observation of the SEI on Li, cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) was performed on a Glacios microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operated at 200 kV. A Li-deposited TEM grid (200-mesh Cu, lacey carbon film; deposition at 1.0 mA cm−2 for 1.0 mAh cm−2) was sealed in a microtube (Eppendorf) within an argon-filled glovebox, rapidly transferred, and immediately quenched in liquid nitrogen. The cryo-frozen grids were then mounted onto a cryo-autoloader (Glacios) under fully cryogenic conditions and subsequently introduced into the TEM chamber for analysis.

The pore size distribution was investigated using mercury intrusion porosimetry (Auto Pore IV 9520 (Micromeritics)). A penetrometer with a total volume of 3 mL and stem volume of 0.4 mL was loaded with 0.38 g of the etched SSIC. The mercury intrusion volume was obtained in the pressure range of 0.1 − 60000 psia. The pore radius was estimated from the pressure (P) by the Washburn equation70:

where a contact angle (\(\theta\)) is 130° and mercury surface tension (\(\gamma\)) is 485 dyn cm−1. The internal structure of the pouch-type cell was characterized using X-ray microtomography (Xradia 520 Versa, Carl Zeiss Inc.). During tomography, 993 projection images were acquired by utilizing the × 4 optical magnifications.

Preparation of the ZPE(TFSI–)

First, LiBETI and the as-synthesized ZPE(TFSI–) were dried at 120 °C under vacuum overnight. The ZPE(TFSI–) precursor was composed of LiBETI and ZM(TFSI–) (incorporating 1 wt.% BPO as a thermal-initiator) without any processing solvents, and the composition ratio of LiBETI/ZM(TFSI–) was 1/1 (mol/mol). The obtained LiBETI/ZM(TFSI–) mixture was subjected to ultrasonication (for 0.5 h), followed by mixing (for 6 h) at 80 °C to obtain a good dispersion state. Subsequently, the mixtures were filled in a home-made polypropylene mold and then thermally cured at 120 °C for 3 h, producing a self-standing ZPE(TFSI–) films. As a control sample for the comparative analysis, a PEO-based polymer electrolyte precursor (LiTFSI/PEO) was dissolved in N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and stirred continuously for 6 h, and the composition ratio of EO/Li was 1/1.5 (mol/mol). Thereafter, the resulting LiTFSI/PEO mixtures were ultrasonicated for 0.5 h and then poured into a home-made polypropylene mold. The DMF was dried in an oven at 80 °C for 12 h prior to use to remove residual solvent. To rigorously prevent moisture contamination, all synthesis, handling, polymerization, and storage procedures were strictly conducted in an argon-filled glovebox (oxygen and water were less than 0.1 ppm).

Fabrication of the electrodes and ASSB full cells

The positive electrode slurries were prepared with a composition of LiFePO4 (LFP, LG energy solution)/carbon black (CB)/ polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) = 90/5/5 (w/w/w), LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (NCM811, LG energy solution)/CB/binder (PVDF/trimethylolpropane triacrylate (TMPTA)/1-vinyl-3-allylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (VAI-TFSI) = 3/0.7/1.3 (w/w/w)) = 92/3/5 (w/w/w)71, and over- Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 (LLO, LG energy solution)/CB/PVDF = 92/4/4 (w/w/w)). For the positive electrode, PVDF was solely used as the binder after dissolution in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, Aldrich) for 12 h. The concentration of the binder solution was standardized as 10 wt.%. The casted positive electrode slurry was vacuum-dried at 120 °C for 12 h, followed by calendaring at 60 °C. This procedure was repeatedly conducted to reach the designed areal-mass-loading value. The positive electrodes were fabricated by casting a slurry mixture on an Al current collector. Thereafter, the casted positive electrode slurry was vacuum-dried at 80 °C for 12 h and followed by calendaring at 120 °C. The areal mass loading of active materials in the casted positive electrode was ~52.0 mg cm−2. As a practical approach to achieve high-energy-density ASSB full cells, the ZPE was integrated with an aramid nonwoven porous substrate acting as a mechanically compliant scaffold (thickness ~18 μm, porosity ~86%, average pore size ~110 µm, Dupont Inc.)70. The introduction of nonwoven scaffold improved the thickness of the ZPE (~30 µm; Fig. 6g). In the full cell, a thin Li-metal foil (Honjo Metal Co., Ltd., thickness 50 µm) was used as the anode. The pouch-type cell (23 × 21 mm2) comprising a Li-metal negative electrode (10.0 mAh cm⁻2) and a ZPE-embedded NCM811 positive electrode (10.0 mAh cm⁻2) was sealed in an aluminum pouch film within a dry room (dew point: −60 °C). Its electrochemical performance was evaluated at 25 °C under a constant stack pressure of 500 kPa.

Electrochemical characterization

The ionic conductivity of the electrodes was estimated using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis at a frequency range from 10–2 to 106 Hz and an applied amplitude of 10 mV using a potentiostat (VSP classic, Bio-Logic). Impedance spectra were recorded over a temperature range of 20–60 °C. The ionic conductivity (σ) was calculated using the relation:

where L is the pellet thickness, R is the bulk resistance obtained from the Nyquist plot, and A is the electrode–electrolyte contact area. The activation energy (Eₐ) for ionic transport was extracted from the Arrhenius relation based on the temperature-dependent conductivity. The electrochemical stability windows of the electrolytes were evaluated by LSV analysis at a scan rate of 0.1 mV s−1, in which a carbon electrode was used as the working electrode. The electrochemical floating test, in which cells (Li-metal negative electrode | |NCM811 positive electrode in the presence of ZPE) were charged to 4.7 V and then held at 4.75 and 4.8 V for 10 h while the current was being monitored, was investigated. The Cu foil assembled with ZPE was subjected to Li plating/stripping for 20 cycles at a current density of 0.2 mA cm−2 with an areal capacity of 0.2 mAh cm−2. The localized EIS (LEIS) area scans were conducted using a scanning probe workstation (M470, Biologic) at a fixed frequency of 50 Hz and an applied amplitude of 100 mV at 10 μm intervals. A microscale probe served as the counter electrode, and impedance measurements were performed for both the ZPE and the control sample (ZP/LiBETI). The Li⁺ transference number (tLi⁺) was determined by potentiostatic polarization, applying DC bias to a Li⁺ non-blocking symmetric cell and recording EIS spectra before and after polarization. The tLi⁺ value was calculated as follows70:

where ΔV is the applied potential, I₀ and R₀ are the initial current and resistance, and Io and Ro are the steady-state current and resistance after polarization, respectively. EIS fitting method on an electrochemical system was conducted on an equivalent electrical circuit consisting of common passive components (such as resistances and capacitances) and other more complicated (referred to as distributed) elements connected together using a potentiostat software (VSP classic, Bio-Logic) to simulate the impedance data on a model circuit.

The electrochemical stability windows were tested using cells (Li|ZPE | C65) at a sweep rate of 0.1 mV s−1. The electrochemical floating test was performed on Li‖NCM811 cells employing ZPE as the electrolyte. Each cell was charged to 4.7 V at a low current density (C/15), followed by a constant-voltage hold at 4.75 and 4.8 V for 10 h while monitoring the current response. Cyclic voltammetry measurements were carried out using 2032-type coin cells composed of a Li-metal negative electrode (Honjo Metal Co., Ltd., thickness = 100 μm) and an NCM811 positive electrode (thickness = 90 μm, areal-mass-loading = 21 mg cm⁻2). The scans were performed at a sweep rate of 0.1 mV s⁻1 within the potential range of 3.0–4.25 V (vs. Li/Li⁺). The Li-metal negative electrode cycle test was conducted using Li||Li symmetric cells at a current density of 1.0 mA cm−2 and an areal capacity of 1.0 mAh cm−2 at 25 °C. The charge/discharge performance of the cells was investigated using a cycle tester (PNE Solution).

Calculation of energy densities

The energy densities of the cells were estimated based on the weight and volume of ZPE-embedded NCM811 positive electrode (including an Al current collector), Li-metal negative electrode (including a Cu current collector), and ZPE in the cell. Calculation details for the energy densities are described in Supplementary Tables 6 and 7.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations

All density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the DMol3 program72,73. The B3LYP hybrid functional was adopted for the electrostatic potential (ESP) and orbital calculation74,75. The interaction energies were computed within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional76. Spin-polarized calculations were carried out at the DNP 4.4 level, incorporating all-electron relativistic effects in the core treatment. The self-consistent field (SCF) convergence threshold was set to 1.0 × 10⁻6 eV atom⁻1. For geometry optimization, convergence criteria were defined as 1.0 × 10⁻5 Ha for energy, 0.002 Ha Å⁻1 for force, and 0.005 Å for displacement.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

We performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulation for LiBETI with ZM(TFSI–) or ZP(TFSI–) to investigate the effect of the mixing property77 and Li+ dissociation degree with the in situ and ex situ environment. In model systems, ZM(TFSI–) or ZP(TFSI–) with LiBETI was packed to mimic the in situ and ex situ environment (Supplementary Data 1–4). In addition, the MD simulation was conducted to determine the ZM with a high Li+ transport behavior among the ZMs with different anions (SO3– and TFSI–). For this, the bulk system with the same ratio as experimental molar ratio (i.e., ZM(TFSI–) or ZM(SO3–) unit/LiBETI =1/1.5 (mol/mol)) was modeled (Supplementary Data 5, 6). Initially, all systems were subjected to NPT ensemble to equilibrate the systems for 1 ns. Subsequently, the equilibrated systems were simulated for 5 ns under the NVT ensemble at 25 °C. All the valence and non-bonded interactions were described based on COMPASSII forcefield78. The temperature control was performed using Nose-Hoover Langevin (NHL thermostat and pressure control was performed using Berendsen barostat79,80.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper, its Supplementary Information, and Supplementary Data files. The initial and final configurations for the MD simulations, as well as the optimized configurations for the DFT calculations, are included in Supplementary Data 1–8. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Xu, K. Nonaqueous liquid electrolytes for lithium-based rechargeable batteries. Chem. Rev. 104, 4303–4418 (2004).

Zhao, Q., Stalin, S. & Zhao, C.-Z. Designing solid-state electrolytes for safe, energy-dense batteries. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 229–252 (2020).

Kamaya, N. et al. A lithium superionic conductor. Nat. Mater. 10, 682–686 (2011).

Kato, Y. et al. High-power all-solid-state batteries using sulfide superionic conductors. Nat. Energy 1, 16030 (2016).

Banerjee, A. et al. Interfaces and interphases in all-solid-state batteries with inorganic solid electrolytes. Chem. Rev. 120, 6878–6933 (2020).

Lee, Y. G. et al. High-energy long-cycling all-solid-state lithium metal batteries enabled by silver–carbon composite anodes. Nat. Energy 5, 299–308 (2020).

Janek, J. & Zeier, W. G. Challenges in speeding up solid-state battery development. Nat. Energy 8, 230–240 (2023).

Armand, M. B. Polymer electrolytes. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 16, 245 (1986).

Dong, T. et al. A multifunctional polymer electrolyte enables ultra-long cycle-life in a high-voltage lithium metal battery. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 1197 (2018).

Xia, S. et al. Practical challenges and future perspectives of all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries. Chem 5, 753 (2019).

Huang, Y.-F. et al. A relaxor ferroelectric polymer with an ultrahigh dielectric constant largely promotes the dissociation of lithium salts to achieve high ionic conductivity. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 6021–6029 (2021).

Shi, P. et al. A dielectric electrolyte composite with high lithium-ion conductivity for high-voltage solid-state lithium metal batteries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 602–610 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Poly (ionic liquid)s-in-salt electrolytes with co-coordination-assisted lithium-ion transport for safe batteries. Joule 3, 2687–2702 (2019).

Chen, F., Wang, X., Armand, M. & Forsyth, M. Cationic polymer-in-salt electrolytes for fast metal ion conduction and solid-state battery applications. Nat. Mater. 21, 1175–1182 (2022).

Flory, P. J. Thermodynamics of high polymer solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 10, 51–61 (1942).

Jones, S. D. et al. Design of polymeric zwitterionic solid electrolytes with superionic lithium transport. ACS Cent. Sci. 8, 169–175 (2022).

Jones, S. D. et al. Decoupling ion transport and matrix dynamics to make high performance solid polymer electrolytes. ACS Polym. Au 2, 430–448 (2022).

Ferry, A. et al. The molar conductivity behavior in polymer electrolytes at low salt concentrations; a Raman study of poly(propylene glycol) complexed with LiCF3SO3. Electrochim. Acta 40, 2369–2373 (1995).

Bishop, A. G. et al. Ion association and molar conductivity in polyether electrolytes. Electrochim. Acta 43, 1453–1457 (1998).

McKenzie, I. et al. A β-NMR study of the depth, temperature, and molecular-weight dependence of secondary dynamics in polystyrene: Entropy–enthalpy compensation and dynamic gradients near the free surface. J. Chem. Phys. 156, 084903 (2022).

Sánchez-Soto, P. et al. Effect of molecular mass on the melting temperature, enthalpy and entropy of hydroxy-terminated PEO. J. Therm. Anal. Cal. 67, 189–197 (2002).

Kim, S. C. et al. High-entropy electrolytes for practical lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 814–826 (2023).