Abstract

Although polylactic acid is a promising biodegradable plastic, its slow degradation under natural conditions, microplastic formation, and CO2 emissions during decomposition undermine its sustainability. Photoreforming offers a promising strategy for polylactic acid conversion; however, current methods suffer from sluggish kinetics and low selectivity. Here, we design a Ni single-atom catalyst anchored on CdS (Ni/CdS) to enable alkali-free photoreforming of real polylactic acid plastic waste under mild conditions. Ni single atom sites facilitate sequential cleavage of α-OH and Cα-H bonds, enabling efficient H2 evolution and significantly improving the yield and selectivity of polylactic acid conversion to H2 and pyruvic acid, achieving an apparent quantum efficiency of 46%. Furthermore, we successfully scaled up the synthesis of Ni/CdS and implemented a square-meter-scale reaction system, demonstrating stable outdoor photoreforming of real polylactic acid plastic waste under sunlight. This work paves a promising pathway for solar-driven upcycling of polylactic acid plastic waste.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To date, over 8 billion tons of plastic have been produced worldwide, with more than 80% either landfilled or released into the natural environment, posing a severe threat to ecosystems and human health1,2,3. Biodegradable plastics have emerged as a promising solution to this issue, leading to a surge in their production in recent years. Among them, polylactic acid (PLA) is considered a promising alternative to conventional petroleum-based plastics, accounting for up to 67% of the total production of biodegradable plastics4,5,6. However, the degradation rate of PLA under natural conditions remains below expectations, and the incomplete degradation of PLA will generate microplastics with environmental hazards7,8,9. Furthermore, the degradation process of PLA releases substantial amounts of CO2, exacerbating carbon resource wastage and significantly increasing its carbon footprint, thereby undermining its sustainability as an environmentally friendly material10,11. Therefore, it is imperative to develop an efficient PLA recycling strategy to convert PLA waste into high-value chemicals or renewable resources, promoting its sustainable development and circular utilization.

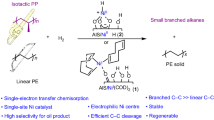

Photoreforming of PLA is regarded as an environmentally friendly and sustainable strategy that enables the conversion of polylactic acid plastic waste into hydrogen and other valuable small-molecule products under mild conditions, thereby facilitating resource recycling and reducing environmental burdens12,13,14. For instance, the hydrolysis and photocatalytic dehydrogenation of PLA to generate H2 and pyruvic acid represent an economically valuable upcycling pathway, which involves the sequential cleavage of the α-OH and Cα-H bonds in pre-treated PLA15. However, the practical application of PLA photoreforming faces several challenges. First, the photoreforming process of PLA suffers from sluggish kinetics due to charge recombination and slow surface reactions in conventional photocatalysts. Second, the lack of specific recognition and activation sites for the α-OH and Cα-H bonds in lactic acid leads to unsatisfactory pyruvic acid selectivity16. Additionally, reported PLA photoreforming strategies require alkaline-assisted pre-hydrolysis, which increases costs and complicates product separation17,18. As a classic photocatalyst, cadmium sulfide (CdS) exhibits excellent optical properties and a favorable band structure, making it a promising candidate for PLA photoreforming under alkali-free conditions19,20,21. However, pristine CdS lacks the necessary activation sites for α-OH and Cα-H bond cleavage and hydrogen evolution, preventing the effective extraction of α-OH and Cα-H from pre-treated PLA to release hydrogen and produce pyruvic acid. Therefore, constructing α-OH/Cα-H activation and H2 evolution sites on the CdS surface holds great potential for achieving efficient PLA photoreforming into pyruvic acid and hydrogen.

In this study, we construct stable sulfur-anchored Ni single atoms on the CdS surface (denoted as Ni/CdS) to facilitate localized enrichment of photogenerated charges and selective activation of pre-treated PLA. Ultrafast spectroscopy confirms that atomic-level Ni sites can rapidly extract photogenerated electrons from CdS and effectively suppress charge recombination. Combining in situ characterization and theoretical calculations, we demonstrate that Ni sites can promote the adsorption of lactic acid molecules in pre-treated PLA via α-OH coordination, enabling sequential dehydrogenation via oxygen-centered and carbon-centered radicals, thereby achieving single selective pyruvic acid production on Ni/CdS. Based on the developed Ni/CdS photocatalyst, we establish an alkali-free photoreforming route for real PLA plastics under solar irradiation. The real PLA plastic is first subjected to photothermal pretreatment to promote hydrolysis. In the pre-treated PLA solution, Ni/CdS achieves H2 and pyruvic acid yields of 3.93 and 3.66 mmol g−1 h−1, respectively. We integrate the entire system into a continuous-flow process and construct a flat-panel reactor, enabling long-term stable solar-driven conversion of pre-treated PLA into H₂ and pyruvic acid with apparent quantum efficiency of 25.9% and 24.2%, respectively.

Results

Synthesis and characterizations of Ni/CdS photocatalyst

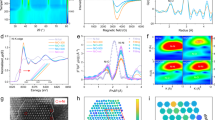

To achieve an efficient PLA photoreforming process, high-uniform CdS nanocrystals were synthesized by controlling the hydrolysis of thioacetamide (TAA), and then isolated Ni sites were anchored onto their surfaces via a facile impregnation-calcination process. As depicted in Fig. 1a, the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of Ni/CdS exhibits only the characteristic diffraction peaks of CdS, suggesting the absence of detectable Ni species aggregation22. A weak additional peak was observed in the XRD pattern, which may be associated with local lattice distortion. Given the limitations of XRD in detecting non-periodic structural changes, EPR measurements performed under liquid nitrogen were further confirmed, revealing defect-related signals (Supplementary Fig. S1). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) confirmed the uniform particle size distribution of the synthesized Ni/CdS nanocrystals (Supplementary Fig. S2). After Ni loading, the particle size of the synthesized sample shows negligible change. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed the excellent crystallinity of Ni/CdS (Supplementary Fig. S3), with a lattice spacing of 0.317 nm corresponding to the (101) lattice plane of CdS in the same PDF card as the XRD results. Moreover, no morphological changes were observed after the incorporation of Ni single atoms (Supplementary Fig. S3), further confirming the absence of Ni aggregation. To further examine the atomic structure and Ni atom distribution in the Ni/CdS sample, high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) with atomic resolution was performed. As shown in Fig. 1b, STEM imaging confirms the precise alignment of the (101) plane of the sample, with no detectable Ni-related particles or clusters23. However, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) mapping reveals that Cd, S, and Ni elements are uniformly distributed throughout the sample (Fig. 1c). This confirms that Ni is homogeneously dispersed on the CdS surface in the form of isolated single atoms. The real weight ratio of Ni was recorded with ICP-OES and the result is shown in Supplementary Table S1.

a XRD spectra of prepared samples. b HADDF-STEM and c EDS mapping image of Ni/CdS. d Ni K-edge XANES spectrum and the oxidation state of Ni/CdS, Ni foil, Ni(OH)2 and NiOOH. e Fourier transform (FT) magnitudes of the experimental Ni K-edge EXAFS spectra of NiO, Ni-foil and Ni/CdS, Ni foil and NiS. f Experimental and best-fitted EXAFS spectra in K space for Ni/CdS. g Experimental and best-fitted EXAFS spectra in R space for Ni/CdS. h Wavelet transform simulation for the k3-weighted EXAFS signals for Ni/CdS, Ni foil and NiS.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed to determine the chemical state of Ni species. Compared with CdS, the Cd and S peaks in Ni/CdS exhibited a blue shift (Supplementary Fig. S4), indicating that Ni loading induced electronic redistribution, attracting more electrons toward the Ni atoms24,25,26. The Ni K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectrum of Ni/CdS displayed a distinct profile compared to Ni foil, Ni(OH)2, and NiOOH, confirming the unique local environment of the Ni species (Fig. 1d). The oxidation state of Ni species was further qualitatively determined and is shown in the inset. Linear fitting of the first derivative of χμ(E) confirmed that the valence state of Ni in Ni/CdS is ~+2.5. Extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analysis was conducted to investigate the coordination environment of the Ni species. As shown in Fig. 1e, the Fourier-transformed EXAFS spectrum of Ni/CdS exhibited a single primary peak at 1.6 Å, corresponding to the first coordination shell of Ni, which closely overlaps with the Ni-S peak of NiS. In contrast to Ni foil and NiS references, no Ni-Ni or Ni-S-Ni bonds were detected in Ni/CdS, ruling out the presence of Ni-related particles or clusters and further confirming that the Ni atoms are isolated and coordinated with S atoms from CdS. To gain deeper insights into the local structure, EXAFS spectra in both R-space and K-space, along with their corresponding fitting curves, were analyzed, revealing the coordination shell of atomically dispersed Ni centers in the Ni/CdS sample (Fig. 1f, g). The Ni-S bond length in Ni/CdS was determined to be 2.23 Å, shorter than that in Ni foil. The fitted coordination number of Ni was found to be 4, identical to the coordination number of Cd on the catalyst surface (Supplementary Table S2), suggesting that Ni single atoms substitute Cd atoms in the CdS lattice. Furthermore, wavelet transform (WT) analysis was employed to further confirm the coordination environment of Ni atoms (Fig. 1h). The maximum intensity at 4.2 and 4.9 Å−1 corresponded to Ni-S coordination, while the intensity maximum at 6.7 Å−1 was characteristic of Ni-Ni coordination in Ni foil. Collectively, these results provide strong evidence for the atomic dispersion of Ni species in the catalytic system27,28,29. The ICP-OES results of the solution after the impregnation process are presented in Supplementary Table S3. It is clearly observed that Cd was partially substituted by Ni during the impregnation, indicating successful incorporation of Ni into the CdS lattice. The particle size and BET surface area exhibit unchanged after loading Ni (Supplementary Fig. S5), which also indicates that no Ni particle was agglomerated during the synthesized process.

Photoreforming activity

First, PLA plastic powder was subjected to photothermal pre-hydrolysis in pure water, utilizing concentrated solar energy as the direct energy source without the involvement of alkali or catalytic additives (Fig. 2f). SEC analysis in DMF (Supplementary Fig. S6) did not detect the existence of the short PLA chain (oligomer), which confirmed that all PLA has been converted to Lactic acid (LA). Subsequently, the photocatalytic reforming performance of the designed catalyst was evaluated in the pre-hydrolysis PLA aqueous solution after photothermal pretreatment. As shown in Fig. 2a, pristine CdS exhibited only limited photocatalytic reforming activity toward pre-hydrolysis PLA, whereas the reaction rate significantly increased upon the incorporation of atomically dispersed Ni. The pre-hydrolysis PLA reforming rate followed a volcano-type trend with increasing Ni loading, reaching its maximum at a Ni content of 0.79%. Under these conditions, the hydrogen and pyruvic acid production rates were 3.93 mmol g−1 h−1 and 3.66 mmol g−1 h−1, respectively, with a near-complete pre-hydrolysis PLA conversion (Supplementary Fig. S7). Figure 2b and Supplementary Fig. S8 presents the 1H NMR spectra of the liquid samples before and after the reaction, confirming the complete degradation of lactic acid and the formation of pyruvic acid, with benzoic acid used as an internal standard30,31. Specifically, a weak peak corresponding to an impurity generated during the partially hydrolysis of PLA is observed. Apart from this, only two minor peaks which are attributed to trace impurities formed during the degradation process are detected. The low intensity and limited number of these peaks suggest that the quantity of such byproducts is low and below the threshold for reliable quantification. Therefore, their impact on the overall reaction pathway and product distribution can be considered negligible. The observed photocatalytic performance indicates a highly selective process governed by a single, well-defined reaction route, unlike previously reported pathways that may have elaborated coupled by-products4. The developed Ni/CdS catalyst demonstrated a high and competitive solar energy conversion efficiency, as the result shown in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table S6. Moreover, the catalyst exhibited high stability, with no noticeable decline in catalytic activity after six consecutive cycles (Fig. 2d). Post-reaction characterization, including XRD, SEM, and TEM analyses, revealed that the structural and morphological features of Ni/CdS remained nearly identical to those of the fresh sample (Supplementary Figs. S9–11), further confirming its robustness and durability. The content of solution after reaction was also characterized (Supplementary Table S6), with 0.16% weight loss of CdS, indicates that catalyst remains stable in the reaction solution.

a PLA photoreforming performance of CdS and Ni/CdS with differenc Ni content. Error bars indicate the standard deviations and obtained by 3 times test. The photocatalytic reaction was conducted under illumination from a Xe lamp (Perfect Light, Beijing) equipped with an AM 1.5 G filter, with a light intensity of 150 mW·cm−2. The reaction solution consisted of 30 mg of catalyst dispersed in 30 mL of a 10% pre-hydrolyzed PLA solution. b 1H NMR spectra of the reaction solution before and after photoreforming in a specific test. c Quantum efficiency of Ni/CdS under the irradiation of different wavelength obtained by one-time test. d Stability of Ni/CdS under 6th cycling test.

Charge carrier separation kinetics

After confirming the high efficiency of Ni/CdS in pre-treated PLA photoreforming, a series of characterizations were conducted to elucidate the behavior of photogenerated electrons, thereby gaining deeper insights into the reaction mechanism and understanding the factors contributing to the enhanced photocatalytic performance. The light absorption capability of the samples was evaluated using UV-vis diffuse reflection spectra (Supplementary Fig. S12a). Both Ni/CdS and pristine CdS exhibited similar absorption edges at about 520 nm, indicating that the incorporation of Ni sites had minimal impact on the band gap (Supplementary Fig. S12b). The band structure was determined based on XPS analysis in combination with the optical band gap. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S13, the valence band maximum (VBM) was estimated by extrapolating the leading edge of the XPS valence band spectrum, yielding a value of 0.67 eV and 0.66 eV for CdS and Ni/CdS. The band gap of CdS and Ni/CdS, obtained from UV-vis spectroscopy, were calculated to be 2.28 eV and 2.24 eV. Accordingly, the conduction band minimum (CBM) was derived using the equation CBM = VBM - Eg, resulting in a value of −1.61 eV and −1.58 eV. However, the Ni/CdS sample displayed a significantly enhanced absorption beyond 520 nm, suggesting an increase in light-harvesting ability with Ni loading. Photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy was performed to investigate the effect of Ni incorporation on charge separation32. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S14, Ni/CdS exhibited a markedly reduced PL intensity compared to pristine CdS, indicating an enhanced charge separation efficiency. Further electrochemical measurements revealed that under illumination, Ni/CdS exhibited significantly lower impedance, facilitating the separation and transport of photogenerated charge carriers (Supplementary Fig. S15a). Additionally, transient photocurrent response measurements demonstrated that the incorporation of Ni led to an increased photocurrent intensity in CdS, highlighting a substantial improvement in the charge transfer efficiency (Supplementary Fig. S15b)33,34.

Transient absorption spectroscopy (TAS) was conducted to further elucidate the impact of Ni incorporation on charge transfer dynamics. As shown in Fig. 3a–d, both CdS and Ni/CdS exhibit a sharp positive peak at 500 nm and a broad peak at 650 nm, corresponding to excited-state absorption (ESA) and stimulated emission (SE), respectively35. The intensities of both peaks are higher in the Ni/CdS spectrum than in the CdS spectrum, indicating a greater degree of electronic excitation in the Ni/CdS system. The ESA peak at ~500 nm is primarily attributed to the absorption of excited electrons in the conduction band of CdS. However, in the Ni/CdS system, this peak may also be influenced by electron transfer dynamics at the CdS/Ni interface. Figure 3e, f presents the fitted time-dependent decay curves at 500 nm, where the average fitted decay times for CdS and Ni/CdS are 126 ps and 106 ps, respectively. The decay time represents the lifetime of the secondary excited electrons in the conduction band. The reduced decay time of Ni/CdS corresponds to an accelerated electron transfer from the CdS conduction band to the Ni orbitals, leading to more rapid consumption of excited electrons. To further validate this observation, Supplementary Fig. S16 presents the fitted decay curves for the SE peak at 650 nm. In the catalytic system, the SE signal can be attributed to the radiative recombination of excited electrons within the CdS conduction band or Ni sites, providing insights into the electron annihilation process. The fitted decay time of Ni/CdS (69.5 ps) is longer than that of CdS (59.8 ps), suggesting extended electron dynamics, which may result from reduced charge recombination in CdS or enhanced electron retention at the Ni sites. Additionally, an extra charge transfer component can be fitted into the Ni/CdS spectrum, corresponding to electron transfer from CdS to Ni, which aligns well with the XPS results. Thus, these findings demonstrate that Ni sites facilitate efficient photogenerated charge separation, forming electron-rich regions that extend carrier lifetimes and further enhance photocatalytic performance36,37,38.

Reaction mechanism

To gain deeper insights into the reaction mechanism and pathway, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted. First, the influence of Ni sites on the band structure was investigated (Fig. 4a). Compared with pristine CdS (Supplementary Fig. S17), impurity states associated with Ni appeared near the conduction band minimum of Ni/CdS, indicating that Ni can act as an electron-enrichment center for photogenerated electrons. Figure 4b presents the computed electron localization function, which reveals that the introduction of Ni induces localized charge rearrangement, leading to charge accumulation at the Ni sites. Additionally, three-dimensional charge density and planar-averaged charge density differences were calculated. As shown in Fig. 4c, charge redistribution occurs at the Ni sites, which facilitates the separation of photogenerated charge carriers. This redistribution induces localized positively and negatively charged regions on the catalyst surface, forming the reduction and oxidation reaction sites, respectively. Figure 4d presents the adsorption energies of lactic acid at different sites on CdS and Ni/CdS, the detailed absorption site model is shown in Supplementary Fig. S18. The introduction of Ni significantly enhances the adsorption of lactic acid, with the most favorable adsorption site located at the S atom adjacent to Ni.

a Calculated band structure of Ni/CdS. b Electronic localization functions of CdS (top) and Ni/CdS (down). c The differential charge density and the corresponding average charge density along the z axis of Ni/CdS. d Calculated adsorption energy of lactic acid on CdS and Ni/CdS. e In situ DRIFTS of PLA photoreforming over Ni/CdS, where red arrow indicates to the hydroxyl on carboxyl and green arrow indicates to the hydroxyl on α-carbon. In situ EPR of PLA photoreforming over f CdS and g Ni/CdS. h Gibbs free energy HER processes over CdS and Ni/CdS. i Calculated energy profiles of different reaction processes for PLA photoreforming over CdS and Ni/CdS. j Reaction scheme of pre-hydrolysis PLA conforming.

In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (in-situ DRIFTS) (Supplementary Fig. S19) and in situ electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurements were performed to confirm the photocatalytic reforming pathway of lactic acid on Ni/CdS, to complement the theoretical analysis with experimental verification resulted from the limitations of DFT in describing the catalytic environment. As shown in Fig. 4e, as the reaction progresses, deprotonation occurs at the hydroxyl group on the α-carbon of lactic acid, indicating the gradual consumption of the hydroxyl group and the formation of ·RO radicals39. Furthermore, the EPR spectra of CdS (Fig. 4f) exhibits a distinct sextet peaks signal, which are associated with ·RO radicals and hydroxyl group according to simulation. However, in the spectra of Ni/CdS (Fig. 4g), the signal intensity of carbon-centered radicals is significantly reduced, and the hydroxyl-related signals vanish40,41. In the DRIFTS spectra, the consumption of hydroxyl groups-associated with the formation of O-centered radicals-can be clearly observed. Furthermore, the in-situ EPR spectra of Ni/CdS show a suppression of carbon-centered radical signals and the disappearance of hydroxyl-related peaks. Since hydroxyl groups only give rise to O-centered radicals, and based on literature reports that O-centered radicals have intrinsically weak EPR signals, their absence in the spectra is expected and reasonable. Different with the reported references4, the quenching of hydroxyl radicals and the suppression of carbon-centered radicals were clearly observed in this study. Based on the above analysis, DFT simulations were employed to model the photocatalytic reforming process of lactic acid on CdS and Ni/CdS. As illustrated in Fig. 4h, lactic acid undergoes deprotonation in two steps, with each step releasing a proton (H+) to form an intermediate and the final product, pyruvic acid. Since the first deprotonation step is site-dependent, two different intermediates may be generated: ·R radicals formed by α-carbon deprotonation and ·RO radicals formed by hydroxyl deprotonation at the α-carbon42,43,44. Energy optimization results indicate that lactic acid photocatalytic reforming on Ni sites follows a sequential pathway: hydroxyl deprotonation occurs first to generate ·RO radicals, followed by α-carbon deprotonation to yield pyruvic acid. This conclusion aligns well with the observations from in situ DRIFTS and in situ EPR measurements. More importantly, the introduction of Ni significantly reduces the energy barrier of the rate-determining step, effectively promoting lactic acid dehydrogenation. Specifically in our research, experimental results, supported by theoretical calculations, demonstrate that the reaction in this system follows a single pathway: lactic acid is first converted into an oxygen-centered radical intermediate, which then undergoes further transformation to yield pyruvic acid. Additionally, the Gibbs free energy for hydrogen evolution was calculated to assess the ability of lactic acid to generate hydrogen after dehydrogenation. As shown in Fig. 4i, the Gibbs free energy for hydrogen evolution on Ni/CdS is 0.46 eV, which is significantly lower than that of CdS (0.66 eV), confirming the higher hydrogen evolution efficiency of Ni/CdS. These findings collectively demonstrate that Ni sites facilitate the stepwise dehydrogenation of lactic acid, enabling its reforming into hydrogen and pyruvic acid (Fig. 4j)45,46,47. Lactic acid is first adsorbed on the catalyst surface, where the incorporation of single-atom Ni induces electron redistribution and enhances electron enrichment. This site-specific distribution enables the dehydrogenation of the α-carbon and the hydroxyl group to proceed separately and directionally. The enriched electrons facilitate proton reduction and promote hydrogen evolution. Moreover, the promoted hydroxyl dehydrogenation balances the reaction between the two sites, thereby suppressing undesired coupling side reactions (Supplementary Fig. S20).

Expanded outdoor PLA light reforming

Based on the excellent photocatalytic pre-treated PLA reforming performance of Ni/CdS, we further explored the scalability of the reaction beyond laboratory conditions toward practical applications. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, we integrated the photothermal pre-hydrolysis of real PLA plastic waste with photocatalytic upcycling, enabling the collection of high-purity H2 and an aqueous pyruvic acid solution through gas-liquid separation. The long-term performance of Ni/CdS photoreforming of pre-treated PLA was evaluated in a continuous flow reactor (Fig. 5b)48,49. During the 12-day outdoor operation, the reactor continuously produced hydrogen and pyruvic acid. Although the absolute daily yields fluctuated due to variations in sunlight intensity, hydrogen and pyruvic acid were consistently generated in an ~1:1 molar ratio (Fig. 5c). This result highlights the excellent stability and selectivity of the developed Ni/CdS photocatalyst under real-world conditions. After the reaction, we examined the stability of the catalyst loading, confirming that no significant detachment of Ni/CdS occurred (Supplementary Fig. S21). Overall, we have demonstrated a complete process utilizing our Ni/CdS catalyst for the photocatalytic reforming of pre-treated PLA plastic waste into high-value H2 and pyruvic acid.

Discussion

In this work, we successfully synthesized a Ni single-atom catalyst supported on CdS and demonstrated its effectiveness in the photocatalytic hydrogen production from PLA waste plastic. The atomically dispersed Ni sites act as efficient electron trapping centers, facilitating charge separation and transport, prolonging electron lifetimes, and thereby enhancing the overall photocatalytic performance. Compared with previously reported systems, the isolated Ni single-atom sites enable the directional desorption of protons. This well-defined desorption site not only promotes the formation of oxygen-centered radical intermediates, but also guides the reaction along a specific and energetically favorable pathway. The resulting structural uniformity suppresses undesired side reactions, thereby improving both the selectivity and efficiency of the catalytic process. As a result, the hydrogen production efficiency using pre-treated PLA waste plastic reached 3.93 mmol g−1 h−1, while the conversion rate of pyruvic acid achieved 99%. This study presents a rational strategy for tuning surface adsorption energy via single-atom modification, thereby stabilizing lower-energy intermediates and enhancing overall photocatalytic efficiency. Moreover, our findings establish a promising framework for the industrial application of photocatalytic waste plastic degradation, contributing to sustainable hydrogen production and environmental remediation.

Methods

Chemicals

Cd(CH3COO)2 is purchased from BLD Pharm (99.99%). TAA is purchased from Aldrich (98%). Poly-lactic acid was purchased from Amazon (AKH® Premium). NiCl2 was purchased from Aldrich (99.99%).

Synthesize of CdS

CdS was synthesized via a hydrothermal method. First, a specific amount of cadmium acetate (Cd(CH3COO)2) was dissolved in deionized (DI) water, followed by the addition of thioacetamide (TAA) at twice the molar ratio. The solution was then magnetically stirred for 30 min before being transferred to an oven and maintained at 160 °C for 12 h. After the reaction, the CdS precipitate was thoroughly washed with DI water and subsequently dried in an oven at 60 °C overnight.

Synthesize of Ni/CdS

Ni/CdS was synthesized using an impregnation method. First, a specific amount of CdS was dispersed in ethanol. Once uniformly dispersed, a calculated amount of NiCl2 was added to the solution. The mixture was then magnetically stirred for 2 h to ensure the uniform dispersion of NiCl2. After stirring, the solution was transferred to an oven and dried at 60 °C overnight. The resulting dried powder was subsequently placed in a muffle furnace and calcined at 300 °C for 3 h to stabilize the Ni atoms.

Photocatalytic experiment

The poly-lactic acid straw was firstly hydrothermal treated to get the liquid solvent for further degradation. Firstly, 3 g of poly-lactic acid straw was cut into pieces, following the addition of 30 mL DI water. Then the mixture was transferred to Teflon reactor and heated to 150 °C and kept for 10 h. The treated poly-lactic acid solution will be employed as the sacrificial reagent for the following photocatalytic reaction. The hydrolysis process using solar light is the same as it in lab, but using concentrated sunlight as the heating resources.

Photocatalysis reaction was performed using the reactor from Perfect light, Beijing (PLR MFPR-1). Xenon lamp equipped with a AM 1.5 filter was used as light resources (Microsolar300, Perfect light, Beijing). 30 mg of catalyst was mixed with 30 mL of pretreated poly-lactic acid solution and transferred to the reactor (PLR MFPR-1, Perfect light, Beijing). Prior to the reaction, argon gas was continuously introduced into the reactor to eliminate dissolved air. Following this, argon was supplied to regulate the reactor pressure at 30 kPa, ensuring a controlled reaction environment. During the reaction, the concentration of hydrogen was automatically recorded every 1 h. A Gas Chromatograph(GC 9790 plus, Fuli Co.) equipped with a TCD detector was used to record the amount of produced hydrogen.

Characterization

X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) was recorded on a Bruker D8 advanced diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation. High-Angle Annular Dark Field-Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (HAADF-STEM) image and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) mapping image were recorded on the Titan Cs-probe (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) image was obtained in Titan ST (Thermo Fisher Scientific) X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) was obtained on the Thermo SCIENTIFIC ESCALAB Xi+. Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS) and X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES) were obtained at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. The fs-TA measurements were performed on a Helios pump-probe system (Ultrafast Systems LLC) combined with an amplified femtosecond laser system (Coherent). Opticalg parametric amplifier (TOPAS-800-fs) provided a 450 nm pump pulse, which was excited by a Ti: sapphire regenerative amplifier (Legend Elite-1K-HE; 800 nm), 35 fs, 7 mJ/pulse, 1 kHz) and seeded with a mode-locked Ti: sapphire laser system (Micra 5) and an Nd: YLF laser (EvolutIon 30) pumped. In-situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (in-situ DRIFTS) was recorded on a Nicolet 6700 IR spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a Harrick Praying Mantis DRIFTS gas cell. Additional lamp was attached to provide light resources. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was obtained in a electron microscope (eSEM, Quattro, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Ultraviolet-Visible Spectroscopy (UV-vis) spectrum was obtained in a UV/vis/NIR spectrophotometer (Lambda 950, PerkinElmer). Photoluminescence (PL) spectra was obtained in Carry Eclipse (Agilent Technologies). Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) and photocurrent spectrum were obtained in an electrochemical analyzer (CHI660E, CH Instruments), equipped with a xenon lamp (CHF-XM-250W, Perfect Light Beijing). 1H analysis was performed using a Bruker AVQ 500 MHz nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometer at 25 °C, with deuterated DMSO as the solvent and benzoic acid as an internal standard. The number average molecular weight (Mn) and dispersity (Đ) of the polymers were determined using an Agilent dual detector (RI and UV-visible) size exclusion chromatography (SEC) system calibrated with poly (ethylene glycol) standards.

In-situ DRIFTS

In-situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) was performed using a Nicolet 6700 IR spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The catalyst was pre-wetted with lactic acid using a sprayer. During the reaction, argon gas was continuously introduced into the test cell. To ensure humidification, it was first bubbled through deionized (DI) water, allowing trace water vapor to simulate photocatalytic conditions. Prior to the test, background data were collected. Once the reaction commenced, illumination was initiated, and signals were recorded at two-minute intervals. The collected signals were subsequently baseline-corrected by subtracting the initial reference data. To prevent interference from hydroxyl signals in water, water vapor was continuously introduced during the test to maintain saturation, ensuring that only hydroxyl groups from lactic acid were analyzed.

In-situ EPR

The EPR test was performed in ELEXSYS E500 (Bruker). The center field was set to 3512 G; the sweep width was 199.8 G; the microwave power was 10.2 mW with a power attenuation of 13.0 dB; the microwave frequency was 9.853533 GHz; the sweep time was 40 s; and the modulation amplitude was 4.000 G. The software utilized for EPR fitting is the SpinFit Module in Bruker’s Xepr software, with the least squares method. The knowledge to distinguish the radical is from the references16,50.

Catalyst coating for panel reactor

A specific amount of catalyst was dispersed in an ethanol solution with the aid of ultrasonication. The resulting catalyst dispersion was then transferred into a spray gun (W-101, Iwasaki). Using high-pressure nitrogen gas, the spray gun atomized the dispersion and evenly sprayed it onto the non-woven fabric. Once the fabric was fully coated, it was dried before applying additional layers. This process was repeated multiple times to ensure uniform and effective catalyst loading on the non-woven fabric.

The prepared catalysts were labeled as Ni/CdS-0.2, Ni/CdS-0.79, and Ni/CdS-1.25, corresponding to different weight ratios of Ni to CdS.

Data availability

All the data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Uekert, T., Kasap, H. & Reisner, E. Photoreforming of nonrecyclable plastic waste over a carbon nitride/nickel phosphide catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 15201–15210 (2019).

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R. & Law, K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700782 (2017).

Miao, Y. et al. Photothermal recycling of waste polyolefin plastics into liquid fuels with high selectivity under solvent-free conditions. Nat. Commun. 14, 4242 (2023).

Miao, Y., Zhao, Y., Gao, J., Wang, J. & Zhang, T. Direct photoreforming of real-world polylactic acid plastics into highly selective value-added pyruvic acid under visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 4842–4850 (2024).

Tian, S. et al. Catalytic amination of polylactic acid to alanine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 16358–16363 (2021).

Mi, R. et al. Solvent-free heterogeneous catalytic hydrogenation of polyesters to diols. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 135, e202304219 (2023).

Ali, W., Ali, H., Gillani, S., Zinck, P. & Souissi, S. Polylactic acid synthesis, biodegradability, conversion to microplastics and toxicity: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 21, 1761–1786 (2023).

Lian, Y. et al. Effects of polyethylene and polylactic acid microplastics on plant growth and bacterial community in the soil. J. Hazard Mater. 435, 129057 (2022).

Gong, X. et al. Photoreforming of plastic waste poly (ethylene terephthalate) via in-situ derived CN-CNTs-NiMo hybrids. Appl Catal. B-Environ. 307, 121143 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Gao, W., Mo, A., Jiang, J. & He, D. Degradation of polylactic acid/polybutylene adipate films in different ratios and the response of bacterial community in soil environments. Environ. Pollut. 313, 120167 (2022).

Jia, H., Zhang, M., Weng, Y. & Li, C. Degradation of polylactic acid/polybutylene adipate-co-terephthalate by coculture of pseudomonas mendocina and actinomucor elegans. J. Hazard Mater. 403, 123679 (2021).

Ma, Z. et al. An electron transfer mediated mechanism for efficient photoreforming of waste plastics using a Ni3S4/ZnCdS heterojunction. Adv. Mater. 37, 2416581 (2025).

Zhang, S. et al. Boosted photoreforming of plastic waste via defect-rich NiPS3 nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6410–6419 (2023).

Uekert, T., Kuehnel, M. F., Wakerley, D. W. & Reisner, E. Plastic waste as a feedstock for solar-driven H2 generation. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 2853–2857 (2018).

Guo, Y. et al. Reinforced interfacial Cd-Se bond coupling photocatalytic hydrogen evolution with pyruvic acid synthesis. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2401285 (2024).

Tang, Y. et al. Simultaneous and efficient utilization of photogenerated electrons and holes: a case of single-atom Pd-anchored CdS twins. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 7882–7894 (2024).

Ma, C., Li, J., Qiu, J., Wang, M. & Xu, P. Recovery of pyruvic acid from biotransformation solutions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 70, 308–314 (2006).

Wadekar, S. S., Wang, Y., Lokare, O. R. & Vidic, R. D. Influence of chemical cleaning on physicochemical characteristics and ion rejection by thin film composite nanofiltration membranes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 10166–10176 (2019).

Zhou, P. et al. Partially reduced Pd single atoms on CdS nanorods enable photocatalytic reforming of ethanol into high value-added multicarbon compound. Chem 7, 1033–1049 (2021).

Han, G. et al. Visible-light-driven valorization of biomass intermediates integrated with H2 production catalyzed by ultrathin Ni/CdS nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 15584–15587 (2017).

Cheng, L., Xiang, Q., Liao, Y. & Zhang, H. CdS-based photocatalysts. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 1362–1391 (2018).

Han, S., Hu, L., Gao, N., Al-Ghamdi, A. A. & Fang, X. Efficient self-assembly synthesis of uniform CdS spherical nanoparticles-Au nanoparticles hybrids with enhanced photoactivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 3725–3733 (2014).

Huang, X., Jones, T., Fan, H. & Willinger, M. G. Atomic-scale observation of irradiation-Induced surface oxidation by in situ transmission electron microscopy. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 3, 1600751 (2016).

Sendeku, M. G. et al. Deciphering in-situ surface reconstruction in two-dimensional CdPS3 nanosheets for efficient biomass hydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 15, 5174 (2024).

Zhang, Z., Wang, M., Zhou, H. & Wang, F. Surface sulfate ion on CdS catalyst enhances syngas generation from biopolyols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 6533–6541 (2021).

Wang, F. et al. Ordered macroporous carbonous frameworks implanted with CdS quantum dots for efficient photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Adv. Mater. 33, 2102690 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Developing Ni single-atom sites in carbon nitride for efficient photocatalytic H2O2 production. Nat. Commun. 14, 7115 (2023).

Zheng, T. et al. Large-scale and highly selective CO2 electrocatalytic reduction on nickel single-atom catalyst. Joule 3, 265–278 (2019).

Yang, J. et al. In situ thermal atomization to convert supported nickel nanoparticles into surface-bound nickel single-atom catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 14095–14100 (2018).

Liu, C. X. et al. Photocatalytic upgrading of polylactic acid waste into alanine under mild conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401255 (2024).

Teng, K.-X., Niu, L.-Y. & Yang, Q.-Z. Supramolecular photosensitizer enables oxygen-independent generation of hydroxyl radicals for photodynamic therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 4081–4087 (2023).

Li, K. et al. Highly efficient photocatalytic H2O2 production in microdroplets: accelerated charge separation and transfer at interfaces. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 1135–1145 (2023).

Wu, M. et al. Photocatalytic oxidative coupling of methane to ethane using CO2 as a soft oxidant over the Au/TiO2-Vo nanosheets. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202414814 (2025).

Zhang, C. et al. Piezo-photocatalysis over metal-organic frameworks: promoting photocatalytic activity by piezoelectric effect. Adv. Mater. 33, 2106308 (2021).

Long, H. et al. Fine-tuning d-p hybridization in Ni-Bx cocatalyst for enhanced photocatalytic H2 production. Nat. Commun. 16, 946 (2025).

Zhou, Q., Guo, Y. & Zhu, Y. Photocatalytic sacrificial H2 evolution dominated by micropore-confined exciton transfer in hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks. Nat. Catal. 6, 574–584 (2023).

Ruan, X. et al. Cd single atom as an electron mediator in an S-scheme heterojunction for artificial photosynthesis of H2O2. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2405478 (2025).

Li, R. et al. S-Scheme g-C3N4/CdS heterostructures grafting single Pd atoms for ultrafast charge transport and efficient visible-light-driven H2 evolution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2402797 (2024).

Bie, C. et al. A bifunctional CdS/MoO2/MoS2 catalyst enhances photocatalytic H2 evolution and pyruvic acid synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 134, e202212045 (2022).

Xian, C. et al. High nitrile yields of aerobic ammoxidation of alcohols achieved by generating ·O2–and Br· radicals over iron-modified TiO2 photocatalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 23321–23331 (2022).

Zhu, Z. et al. Chemically bonded α-Fe2O3/Bi4MO8Cl dot-on-plate Z-scheme junction with strong internal electric field for selective photo-oxidation of aromatic alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202203519 (2022).

Xiang, Y. et al. One-pot photothermal upcycling of polylactic acid to hydrogen and pyruvic acid. Chin. J. Catal. 59, 149–158 (2024).

Cai, W. et al. Bifunctional CdS-MoO2 catalysts for selective oxidation of lactic acid coupled with photocatalytic H2 production. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 675, 836–847 (2024).

Liang, E. et al. 1T/2H-MoS2/CdS heterojunction for the co-production of lactic acid photoreforming to hydrogen and value-added chemicals. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 12, 114287 (2024).

Chen, C. et al. Supported Au single atoms and nanoparticles on MoS2 for highly selective CO2-to-CH3COOH photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 15, 7825 (2024).

Su, D. et al. Atomically dispersed Ni in cadmium-zinc sulfide quantum dots for high-performance visible-light photocatalytic hydrogen production. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz8447 (2020).

Kang, Y. et al. Mesoporous amorphous non-noble metals as versatile substrates for high loading and uniform dispersion of Pt-group single atoms. Sci. Adv. 10, eado2442 (2024).

Nishiyama, H. et al. Photocatalytic solar hydrogen production from water on a 100-m2 scale. Nature 598, 304–307 (2021).

Fu, H. et al. A scalable solar-driven photocatalytic system for separated H2 and O2 production from water. Nat. Commun. 16, 990 (2025).

Wang, J. et al. Dihydroxyacetone valorization with high atom efficiency via controlling radical oxidation pathways over natural mineral-inspired catalyst. Nat. Commun. 12, 6840 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology and the Center of Excellence for Renewable Energy and Storage Technologies under award number 5937, and the KAUST Supercomputing Laboratory under project K10175.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.H., C.F. and H.Z. constructed and planned the whole project. M.H. and J.A. carried out the synthesis of the samples and photocatalysis test. G.S.A., K.R. and H.S.A. carried out outdoor testing. S.Z. carried out the XANES and EXAFS characterizations. M.H. performed the HRTEM and high-resolution HAADF STEM imaging. V. L. carried out SEC traces. N.H., V.L., D.L. and W.L.L. helped to discuss the reaction mechanism and M.H. and C.F. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, M., Feng, C., Alharbi, J. et al. Isolated Ni atoms enable alkali-free photoreforming of waste polylactic acid plastic. Nat Commun 17, 347 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67050-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67050-7