Abstract

The development of covalent organic frameworks (COFs) that integrate robust chemical stability with efficient charge carrier dynamics remains a critical challenge for photocatalytic applications. Herein, we present a self-locking strategy to synthesize amide-like isoquinolone-linked COFs (IQO-COFs). By leveraging ortho-vinyl aromatic aldehyde and aromatic amine precursors, a tandem process involving thermal 6π-electrocyclization of imine intermediates and Cu(OAc)₂-catalyzed aerobic oxidation enables the irreversible formation of rigid, conjugated isoquinolone linkages. Four crystalline IQO-COFs are constructed with high conversion efficiency and gram-scale feasibility. Locking amide into isoquinolone synergizes enhanced π-electron delocalization with structural rigidity, significantly suppressing exciton recombination and boosting photogenerated charge separation. As a result, IQO-COFs achieve high photocatalytic performance in single-electron transfer (SET)-driven reactions, including the dehalogenation of α-bromoacetophenone and the decarboxylative Minisci reaction under harsh conditions, outperforming amide-linked counterparts. This work establishes a versatile platform to engineer COFs with tailored stability and electronic properties, unlocking new potential for high-performance photocatalytic systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since Yaghi et al.’s 2005 discovery1, covalent organic frameworks (COFs) have fascinated scientists with their precise, modular, and porous crystalline structures2,3. These networks have found applications across various fields, including catalysis4,5,6,7, optoelectronics8,9,10,11, enzyme encapsulation12,13,14, separation15,16,17,18, and energy conversion and storage19,20. A critical challenge, however, lies in balancing structural stability with efficient charge carrier dynamics—a prerequisite for photocatalysis where rapid exciton recombination often limits performance21. Over the past decade, exploring novel linkages proved to be an efficient strategy to enrich the scope of COFs with customized features22. For instance, more stable vinylene linkages address instability and limited π-conjugation in imine-linked COFs23,24,25. However, achieving robust COFs with reversible linkages remains challenging due to limited building block variety.

The irreversible conversion of imine-linked COFs into aromatic heterocycles (e.g., benzothiazole26,27,28, quinoline29,30,31,32, benzoxazole33,34,35, indazole36) represented one powerful strategy to stabilize frameworks while amplifying π-conjugation. Such modifications create rigid, conjugated backbones that suppress non-radiative recombination pathways, as evidenced by extended exciton lifetimes37,38. However, the exploration of COFs in challenging photocatalytic organic transformations involving single-electron transfer (SET) processes, such as carbon-centered radical generation, remains scarce39. Recent studies suggest that amide-linked COFs (Am-COFs) may offer unique advantages in such reactions40,41. For instance, Am-COFs have shown enhanced activity in the dehalogenation of α-bromoacetophenone via SET-mediated carbon radical intermediates42,43, likely due to their electron-deficient amide motifs facilitating substrate activation. Despite these advances, the application of Am-COFs in complex photocatalytic SET-driven reactions, especially under harsh conditions, remains limited, possibly due to their inherently reduced π-conjugation compared to aromatic heterocycle-linked COFs, which has led to reduced research focus in this area. This dichotomy highlights a critical gap: few linkages simultaneously integrate the structural features of amides with the delocalized electronic networks of aromatic heterocycles—a synergy that could unlock outstanding photocatalytic efficiency.

Herein, we address this challenge by introducing isoquinolone—a rigid, conjugated heterocycle with amide-like motifs—as a linkage for COF construction. Leveraging a self-locking mechanism via intramolecular 6π-electrocyclization of o-vinyl imines, we synthesize four highly crystalline isoquinolone-linked COFs (IQO-COFs) with gram-scale feasibility. Compared to conventional Am-COFs, the isoquinolone linkage synergizes enhanced π-delocalization (via planar aromatic stacking) with improved chemical stability, akin to the charge-separated exciton stabilization observed in donor-acceptor COF architectures. This functionality greatly suppresses exciton recombination. Consequently, IQO-COFs exhibit exceptional photocatalytic performance in the SET-mediated reaction, including dehalogenation of α-bromoacetophenone and the challenging Minisci reaction. Our work establishes a generalizable strategy to engineer COF linkages that harmonize electronic delocalization and stability, offering new avenues for designing high-performance photocatalytic frameworks.

Results

The synthesis of isoquinolone in this one-pot tandem reaction starts with the formation of imine, and then the thermal 6π-electrocyclization of imine and pre-anchored vinyl groups affords 1,2-dihydropyridine-linked intermediate, followed by the Cu(OAc)2-catalyzed aerobic oxidation (Fig. 1a)44. Firstly, the synthetic conditions for the model compound 2-phenylisoquinolin-1(2H)-one, involving 2-vinylbenzaldehyde and aniline as starting materials, were optimized. To identify suitable conditions for COFs synthesis, we systematically optimized the reaction system in the presence of 2 equivalents of Cu(OAc)2. Initially, the conventional dehydrating agent MgSO4 for facilitating reversible imine bond formation was substituted with HOAc, with the solvent of DMSO replaced by o-dichlorobenzene (o-DCB). This modification yielded the target product with satisfactory yield. Mechanistic analysis of reported protocols suggests that the excess Cu(OAc)2 requirement originates from its gradual depletion through CuO formation during the reaction. Notably, the presence of HOAc in our optimized conditions may facilitate the regeneration of Cu(OAc)2, potentially reducing the need for excess catalyst. To further investigate this, we systematically lowered the Cu(OAc)2 loading and found that when 0.21 mmol of aldehyde and 0.22 mmol of amine were reacted in 2 mL of o-DCB with 0.2 equivalents of Cu(OAc)₂ under an oxygen atmosphere at 150 °C for 12 h, the target product was obtained in 92% yield—significantly higher than the reported yield of 74%. This optimized protocol provides a robust foundation for the subsequent one-pot synthesis of isoquinolone-bridged COFs.

Encouraged by these findings, we endeavored to synthesize the IQO-COF-1 directly from the building blocks 2,5-divinylterephthalaldehyde (CHO–1) and 1,3,5-Tris(4-aminophenyl)benzene (NH2–1) via the one-pot tandem strategy. To mitigate the potential entangling effects associated with the concerted multi-step transformations on the crystallinity of IQO-COF-1, the reaction conditions were thoroughly screened (Supplementary Table 1). Ultimately, the highly crystalline IQO-COF-1 was successfully constructed using o-DCB as the solvent, with Cu(OAc)2 serving as a catalyst in the presence of HOAc under an aerobic atmosphere at 150 °C for a duration of 3 days. For comparative analysis, we successfully prepared high-crystallinity Im-COF-1a as a reference material via the interfacial polymerization (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 2), which circumvents the thermal 6π-electrocyclization of the ortho-vinyl imine linkages typically observed under conventional solvothermal conditions (Supplementary Fig. 4).

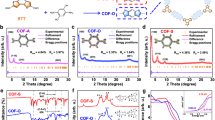

The formation of IQO-COF-1 was initially assessed through Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR, Fig. 2a). In comparison with the corresponding Im-COF-1a, two distinct peaks emerged at 1652 cm−1 and 1626 cm−1 in IQO-COF-1, which were attributed to the stretching vibration modes of the newly formed C = O and C = C bonds of isoquinolone, respectively. Similar variations were observed when comparing small molecules in the model reaction (Supplementary Fig. 5). Simultaneously, a new peak at 1370 cm−1 may be attributed to the C–H bending vibration. The chemical structures were further analyzed by solid-state cross-polarization magic angle spinning (CP-MAS) 13C NMR spectroscopy (Fig. 2b). The 13C isotopically enriched monomer 2,5-divinylterephthalaldehyde was first synthesized to ensure the reliability of the NMR result, and then the 13C-labeled Im-COF-1a and IQO-COF-1 were afforded. The characteristic peak for 13C = O carbon at 161.5 ppm in IQO-COF-1 was observed, while the peak for imine carbon at 156.8 ppm in Im-COF-1a completely disappeared, further confirming the high conversion efficiency. The state of nitrogen was monitored through high-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Fig. 2c), revealing a higher binding energy shift from 398.8 eV to 399.5 eV as imine was converted into isoquinolone. Satisfactorily, the general applicability of this synthetic strategy was validated by synthesizing IQO-COF-2, IQO-COF-3, and IQO-COF-4 (Supplementary Table 3), which were also characterized through FT-IR and XPS measurements (Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 7). Meanwhile, the gram-scale reaction demonstrated the feasibility for the synthesis of IQO-COF-1 without compromising crystallinity and conversion efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 8).

a FT-IR spectra of Im-COF-1a and IQO-COF-1, b Solid-state CP-MAS 13C NMR spectra of 13C-isotope enriched Im-COF-1a and IQO-COF-1. c High resolution N 1 s XPS spectra of Im-COF-1a and IQO-COF-1. d, e Experimental, Pawley-refined and simulated eclipsed AA stacking PXRD patterns of IQO-COF-1 and IQO-COF-2. f N2 sorption isotherms at 77 K of Im-COF-1a and IQO-COF-1 (inset: pore size distribution). g, h HR-TEM image of IQO-COF-1 and IQO-COF-2 (inset: enlargement of selected area and the FFT patterns). i PXRD patterns of as-prepared IQO-COF-1 after being subjected to different harsh chemical conditions. TFA, trifluoroacetic acid.

The PXRD analysis of IQO-COF-1 exhibited a prominent peak at 2.89°, along with additional peaks at 4.99° and 5.69°, corresponding to the (100), (110), and (200) facets, respectively (Fig. 2d). The experimental pattern closely aligned with the simulated model based on the eclipsed AA-type stacking mode. Pawley refinement resulted in optimized unit cell parameters of a = b = 35.13 Å, c = 3.45 Å, α = β = 90°, γ = 120°, with residuals Rwp = 4.30% and Rp = 3.28%. In comparison to the original Im-COF-1a with the peak of (100) facet at 2.77°, it is inevitable that the self-locking of imine linkages leads to a slight reduction in the pore size of the framework (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Meanwhile, the PXRD analysis of IQO-COF-2 showed a prominent peak at 2.45°, with an additional peak at 4.68°, corresponding to the (100) and (200) facets, respectively (Fig. 2e), indicating the replacement of the CHO–1 by CHO–2 enlarge the pore size of the framework. The experimental pattern also matched well with the simulated model based on the eclipsed AA-type stacking mode. Similar highly ordered structures were confirmed for the other two as-synthesized IQO-COFs and their corresponding Im-COFs through PXRD measurements (Supplementary Fig. 9, Supplementary Fig. 10).

Subsequently, the permanent porosities and specific surface areas of Im-COF-1a and IQO-COF-1 were further investigated using N₂ adsorption–desorption isotherms at 77 K (Fig. 2f). Both COFs displayed Type IV isotherms, characteristic of mesoporous structures, with rapid nitrogen uptake at low relative pressures (P/P₀ < 0.15) followed by a gradual adsorption increase at higher pressures. The nearly reversible isotherms and minimal hysteresis loops observed for both COFs are indicative of highly ordered frameworks with narrow pore size distributions (< 4 nm)45. Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis revealed distinct surface areas of 1040 m2 g−1 for Im-COF-1a and 690 m2 g−1 for IQO-COF-1. Pore size distributions, calculated via non-local density functional theory (NLDFT), further confirmed mesoporous features, with Im-COF-1a exhibiting a dominant pore size of 2.8 nm, while IQO-COF-1 showed a slightly smaller pore size centered at 2.3 nm. Notably, similar trends were observed across three additional pairs of COFs: imine-COFs consistently exhibited higher surface areas and larger pore size distributions compared to their IQO-COF counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 11). The reduction in surface area of IQO-COFs likely stems from differences in synthesis methods, coupled with framework mass increase, pore size contraction, and partial structural collapse during the conversion process46.

The highly organized and crystalline architectures of IQO-COF-1 were meticulously elucidated through HRTEM (Fig. 2g). The accompanying Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) pattern displayed a distinct first-order characteristic diffraction ring precisely aligning with the (100) lattice periodicity, measured at 0.87 nm−1. The uniform inter-channel distance of 2.3 nm along the (100) facet was consistent with the outcome of pore size distribution calculations, which closely matched the simulated AA stacking model. At the same time, we clearly captured the hexagonal pores with a diameter of 2.9 nm in the designed IQO-COF-2, which were formed by the aligned monolayers in the AA stacking model (Fig. 2h). Furthermore, IQO-COF-3 and IQO-COF-4 were characterized using HRTEM, and their (100) facets were also consistent with the pore sizes obtained from NLDFT fitting (Supplementary Fig. 12). SEM images unveiled that Im-COFs and IQO-COFs exhibited different morphologies, which may be attributed to the different crystallization processes (Supplementary Fig. 13).

In contrast to amide- and imine-linked counterparts, IQO-COFs should demonstrate exceptional framework robustness. To validate this advantage, IQO-COF-1 was rigorously tested against Im-COF-1 and Am-COF-1 (structural details in Supplementary Fig. 2)42 under prolonged exposure (48 h) to extreme chemical environments, including acidic media (10 M HCl and trifluoroacetic acid at 60 °C), alkaline media (10 M NaOH at 60 °C), and reductive media (NaBH4/MeOH). PXRD and FT-IR analysis demonstrated that IQO-COF-1 maintained full crystallinity and chemical integrity (Fig. 2i, Supplementary Fig. 14). The high stability of IQO-COFs might enable them to be applied to photocatalytic transformation under harsh conditions. Furthermore, the improved stability of IQO-COF-1 was also demonstrated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) in comparison to the imine-linked and amide-linked counterparts (Supplementary Fig. 15).

The photoelectric properties of COFs modulated by linkage engineering were systematically investigated through solid-state UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV-vis DRS). As depicted in Fig. 3a, the introduction of a vinyl bridge into Am-COF-1 led to a noticeable enhancement in light absorption ability, likely due to the extended π electron delocalization within the isoquinolone unit of IQO-COF-1. Mott-Schottky analysis confirmed that all three COFs exhibited characteristic n-type semiconductor behavior, as indicated by the positive slopes of their plots (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 16). The optical band gaps (Eg), derived from Tauc plots, were determined to be 2.58 eV for Im-COF-1, 2.37 eV for Am-COF-1, and 1.90 eV for IQO-COF-1. Corresponding conduction band potentials (Ecb), calculated from flat-band potentials (Efb), were −1.43 V, −1.11 V, and −0.90 V versus the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE), respectively. These results, summarized in the energy band diagram (Fig. 3c), highlight the markedly reduced band gap and more favorable band alignment of IQO-COF-1, suggesting its strong potential for photocatalytic conversion applications.

a UV-vis DRS spectra of IQO-COF-1, Am-COF-1 and Im-COF-1 (inset shows the corresponding Tauc plots). b Mott-Schottky plots of IQO-COF-1. c Energy band structure diagram. d Transient photocurrents under visible light irradiation. e EIS Nyquist plots. f Lifetime analysis by TCSPC of IQO-COF-1, Am-COF-1 and Im-COF-1. g 2D transient absorption surface plots of IQO-COF-1. h fs-TA spectra of IQO-COF-1. i Normalized decay kinetics probed at the maximum transient absorption signal of different COFs. NHE, normal hydrogen electrode.

For a thorough evaluation of IQO-COFs’ photocatalytic potential in organic transformations, comprehensive photoelectrochemical characterization was carried out with comparative assessments using both imine- and amide-linked counterparts. The intensity of the transient photocurrent response revealed distinct differences among the Im-COF-1, Am-COF-1, and IQO-COF-1 (Fig. 3d). Notably, IQO-COF-1 exhibited the highest photocurrent intensity, indicating its exceptional photoinduced electron separation and transport efficiency. This trend was further corroborated by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, where IQO-COF-1 exhibited the smallest semicircle radius in Nyquist plots, indicative of its minimized charge transfer resistance (Fig. 3e). Meanwhile, time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) was utilized to quantify the fluorescence lifetimes. The decay profiles were fitted via a double exponential model, yielding average fluorescence lifetimes of 2.67, 3.00, and 3.68 ns for Im-COF-1, Am-COF-1, and IQO-COF-1, respectively (Fig. 3f). The prolonged lifetime observed in IQO-COF-1 demonstrates the effectiveness of isoquinolone linkage engineering in suppressing charge carrier recombination.

Femtosecond transient absorption spectroscopy (fs-TAS) was further employed to probe the ultrafast dynamics of photoexcited charge carriers (Fig. 3g–i, Supplementary Fig. 17)47. All samples exhibited predominant excited-state absorption signals in the 600–700 nm range with relatively weak ground-state bleaching. Kinetic fitting of the transient profiles identified two characteristic lifetimes: τ₁, corresponding to charge diffusion within the lattice, and τ₂, associated with electron–hole recombination. Im-COF-1 showed the fastest charge generation and rapid recombination (τ₁ = 0.25 ps, τ₂ = 9.9 ps), whereas Am-COF-1 displayed slower generation but a moderately longer lifetime (τ₁ = 2.45 ps, τ₂ = 32.6 ps). IQO-COF-1 exhibited intermediate generation kinetics (τ₁ = 1.25 ps) but a markedly prolonged recombination lifetime (τ₂ = 89.8 ps)—about 9 × longer than Im-COF-1 and nearly 3 × longer than Am-COF-1—providing direct kinetic evidence of its significantly enhanced charge-separation capability48. To further visualize the spatial aspects of charge separation, in situ Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) measurements were carried out under illumination. IQO-COF-1 displayed a pronounced negative surface potential shift of 78.1 mV, compared with 37.0 mV for Im-COF-1 and 56.4 mV for Am-COF-1, indicating more substantial surface electron accumulation and more efficient electron–hole dissociation (Supplementary Fig. 18). These complementary results collectively demonstrate that the isoquinolone linkage not only prolongs carrier lifetimes but also facilitates spatial charge separation, thereby underpinning the enhanced photocatalytic performance of IQO-COF-1. The collective evidence establishes a robust structure-function relationship, positioning IQO-COF-1 as an advanced photocatalytic platform where precisely engineered connectivity motifs dictate both quantum efficiency and operational stability.

Building upon our previous discovery that Am-COFs outperform Im-COFs in photogenerating carbon radical intermediates—a critical step in SET-driven dehalogenation—we sought to determine whether structural optimization of the Am-COF could further enhance this capability42. Guided by the improved π-electron delocalization and photoelectronic properties demonstrated for the newly designed IQO-COFs, we systematically evaluated their photocatalytic performance using α-bromoacetophenone dehalogenation as a benchmark reaction. Strikingly, IQO-COF-1 achieved a 96% yield of acetophenone (1) under irradiation (Fig. 4a), surpassing both Am-COF-1 (69%) and Im-COF-1 (61%). Furthermore, the enhanced photocatalytic activity of IQO-COFs proves to be generalizable by the comparison of IQO-COF-2, IQO-COF-3 and IQO-COF-4 with their corresponding Im-COFs in the same reaction (Supplementary Table 4). Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectroscopy was employed to detect carbon radical species generated during the reaction (Fig. 4b). Using N-tert-butyl-α-phenylnitrone (PBN) as a spin trap for phenyl ketone radicals, IQO-COF-1 exhibited stronger characteristic signals than Am-COF-1 after 4 min of irradiation, while Im-COF-1 showed the weakest signals. These results clearly confirm that IQO-COFs possess higher SET efficiency compared to both Am-COFs and Im-COFs. Based on previous studies and our experimental findings, the plausible mechanism for the IQO-COF-1-catalyzed debromination of α-bromoacetophenone is proposed (Supplementary Fig. 19). Additionally, IQO-COF-1 demonstrated a broad substrate scope, efficiently dehalogenating various α-bromoacetophenones with electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups (2–13) and even 2-bromomalonate (14), achieving high yields in all cases. The chemical and long-range ordered structure of the recycled IQO-COF-1 were further confirmed by FT-IR and PXRD measurements (Supplementary Fig. 20).

a Catalytic efficiency and compatibility studies. b EPR spectra of PBN-radical adduct generated after being irradiated for 4 min during the reaction (from top to bottom: Im-COF-1, Am-COF-1 and IQO-COF-1). Reaction condition: α-bromoacetophenone (0.4 mmol), Hantzsch ester (0.44 mmol), K2CO3 (0.8 mmol), COFs (5 mg), DMF (1 mL), 18 W blue LEDs (460-465 nm), 1 h under nitrogen atmosphere, isolated yield. DMF, N,N-dimethylformamide.

Inspired by the demonstrated efficiency of IQO-COFs with a robust framework in carbon radical generation via the SET process, we further explored their potential in the more challenging decarboxylative Minisci reaction—a mechanistically relevant reaction requiring critical carbon radical intermediates, and this powerful strategy for functionalizing heteroarenes typically requires acidic and strongly oxidizing conditions and often relies on precious metal catalysts or costly homogeneous photocatalysts49,50. After constant attempts, we found that IQO-COF-1 could efficiently catalyze the decarboxylative coupling of cyclohexylcarboxylic acid and isoquinoline under 420 nm light in the presence of ammonium persulfate at room temperature, achieving a remarkable 95% yield (Fig. 5a). In contrast, Am-COF-1 and Im-COF-1 showed significantly lower yields, once again highlighting the higher performance of IQO-COFs. The IQO-COF-2, IQO-COF-3, and IQO-COF-4 were also able to drive the reaction, but with slightly reduced efficiency. Remarkably, the heterogeneous photocatalyst IQO-COF-1 achieved catalytic efficiency comparable to that of the homogeneous photocatalyst 4-CzIPN and higher than that of the iridium-based photocatalyst in this transformation. Since the synthesis of IQO-COFs involves Cu(OAc)2, we first examined the possible presence of copper residues by ICP-OES, revealing only 0.43 wt% residual Cu after rigorous multi-step purification (Supplementary Table 5, NH4OH/HCl/HOAc/H2O2 washing). To exclude any catalytic contribution from these traces in IQO-COF-1, we adopted several complementary strategies. First, we synthesized metal-free analogs via one-step and two-step post-synthetic modification, affording IQO-COF-1a (partially converted) and IQO-COF-1b (fully converted), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 21, Supplementary Fig. 22). While IQO-COF-1a displayed relatively lower photocatalytic efficiency, IQO-COF-1b exhibited performance comparable to IQO-COF-1, clearly indicating that residual Cu does not account for the observed activity. In addition, control experiments with externally added Cu(OAc)2 showed that excess copper in fact suppressed the reaction (Supplementary Table 6). Collectively, these results demonstrate that the improved activity of IQO-COF-1 arises from the intrinsic isoquinolone linkages rather than metallic residues. Notably, both post-synthetic routes led to a loss of crystallinity, which further highlights the advantage of our one-pot strategy in constructing highly crystalline, ultrastable, and efficient IQO-COFs.

a Photocatalyst comparison. b Control experiments. c Solvent screening. d Recyclability test. e, f PXRD and FT-IR characterization before and after the reaction. Standard reaction conditions: isoquinoline (0.2 mmol), cyclohexylcarboxylic acid (0.6 mmol), (NH4)2S2O8 (0.4 mmol), COFs (5 mg), DMSO/H2O (2 mL/1 mL), 6 W 420 nm LEDs, 12 h under nitrogen atmosphere, GC (gas chromatography) yield using dodecane as the internal standard. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; DMF, N,N-dimethylformamide.

Solvent screening revealed that a DMSO/H2O (2:1) binary mixture was optimal, likely due to its favorable miscibility with the reactants (Fig. 5c). Control experiments underscored the critical role of (NH4)2S2O8, light irradiation, and IQO-COF-1 in the reaction (Fig. 5b). For instance, replacing (NH4)2S2O8 with oxygen as the oxidant resulted in negligible product formation, while changing the light wavelength from 420 nm to 460 nm reduced the yield to 72%. A key advantage of heterogeneous catalytic systems is their recyclability. IQO-COF-1 could be easily recovered by filtration and reused for five consecutive cycles without any loss of activity, maintaining a 93% yield of product 15 in the fifth cycle (Fig. 5d). Post-catalysis characterization by PXRD and FT-IR confirmed the structural integrity of IQO-COF-1, demonstrating its remarkable stability under acidic and strongly oxidizing conditions (Fig. 5e, f).

The decarboxylative Minisci reaction catalyzed by IQO-COF-1 was evaluated for its substrate compatibility and functional group tolerance (Fig. 6). Isoquinolines bearing bromine, nitro, and ester underwent the reaction smoothly, affording the desired products in moderate to high yields (16–19). Both 4-substituted and 2-substituted quinolines were also compatible, with alkylation occurring selectively at the most electron-deficient sites (20–24). Quinoxaline and phenanthridine proved to be viable substrates, delivering products in satisfactory yields (25, 26). 4-Phenylpyridine was alkylated successfully but furnished a mixture of mono- and dialkylated products (27). The reaction exhibited broad applicability to secondary carboxylic acids, including both cyclic and acyclic variants (28–38). In contrast, primary carboxylic acid showed reduced efficiency, likely due to the instability of its radical intermediate (39). Among tertiary carboxylic acids, rigid structures outperformed flexible ones, suggesting that steric hindrance plays a critical role in determining reactivity (40–43). Phenoxyacetic acid and 1,4-benzodioxane-2-carboxylic acid also participated, yielding products at 83% and 49%, respectively (44, 45).

To probe the reaction mechanism, a radical trapping experiment was performed using (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl (TEMPO) (Fig. 7a). The complete suppression of product formation and the detection of a cyclohexyl-TEMPO adduct by GC-MS confirmed a radical pathway. The reaction’s insensitivity to anthracene, a triplet-state quencher, ruled out energy transfer as a key process51. The addition of ferrocene (a hole scavenger) or K2Cr2O7 (an electron scavenger) completely suppressed the reaction, underscoring the essential roles of both electrons and holes in the photocatalytic reaction. Meanwhile, light-on/off experiments revealed that the reaction yield continued to increase in the dark, consistent with a radical chain process (Supplementary Fig. 23).

a Control experiments. b In situ DRIFTS of IQO-COF-1 in photocatalytic SET reduction of (NH4)2S2O8. c Plausible mechanism. d DFT calculations (The suffix p implies that the simplified monomer alternative to COF was used for modeling, with calculated levels wB97XD/def2-TZVP/SMD// wB97XD/ def2-SVP/SMD). TEMPO, 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-yl)oxyl; SET, single-electron transfer; LUMO, lowest unoccupied molecular orbital; HOMO, highest occupied molecular orbital.

In situ Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFTS) analysis was then conducted to directly monitor the activation of ammonium persulfate under photocatalytic conditions with IQO-COF-1 (Fig. 7b). Upon visible-light irradiation, the enhanced positive band at 1068 cm−1 can be attributed to the S–O stretching vibrations of SO42- 52, indicating the continuous decomposition of persulfate accompanied by the gradual generation of sulfate ions. A plausible mechanistic pathway was then proposed based on these observations and previous reports (Fig. 7c)53,54. Under light irradiation, IQO-COF-1 generates electron-hole pairs. The conduction band reduces ammonium persulfate via a SET process, producing sulfate radical A (SO4•−), which abstracts a hydrogen atom from carboxylic acid to form carboxyl radical B. The intermediate B decarboxylates to generate alkyl radical C, which subsequently attacks protonated heteroarene D. The resulting radical cation E can undergo rearomatization to afford the product F via two distinct pathways: (i) oxidation by photogenerated holes followed by proton elimination, or (ii) oxidation by persulfate with subsequent proton loss.

The enhanced photocatalytic activity of IQO-COF-1, compared to Im-COF-1 and Am-COF-1, can be attributed to its narrowed band gap, extended lifetime, high charge carrier mobility, efficient charge separation, and exceptional stability. To further elucidate the underlying factors, the density functional theory (DFT) calculations were carried out to accurately evaluate the photoinduced electron transfer properties of COF materials. Drawing on the previous options55, the typical COF models contain repeating portions where the edges of the interceptor unit are surrounded by hydrogen atoms (Fig. 7d). The computational results revealed that IQO-COF-1(p) exhibits optimal electron transfer kinetics, demonstrating the lowest Marcus energy barrier (24.7 kJ/mol, equivalent to 5.9 kcal/mol). Meanwhile, it also possesses the calculated highest HOMO orbital energy (−0.271 eV) and the lowest LUMO orbital energy (−0.007 eV) among the Im-COF-1(p), Am-COF-1(p), and IQO-COF-1(p). Based on the same computational approach, the Marcus energy barriers for IQO-COF-2(p), IQO-COF-3(p), and IQO-COF-4(p) were calculated to be 6.9, 7.3, and 7.1 kcal/mol, respectively. This trend matches well with the observed experimental activities (Fig. 7d). To validate the rationality of the COF models, we first compared the UV–vis spectra of three representative model compounds (imine (M1), amide (M2), and isoquinolone (M3)), followed by complementary molecular dynamics simulations and theoretical predictions for both the model compounds and COF fragments (Supplementary Fig. 24, Supplementary Fig. 25). Both isoquinolone (M3) and IQO-COF-1(p) exhibited the most pronounced visible-light absorption, and the simulated spectra agreed well with experimental observations. These results further confirm that amide-containing molecules have a stronger propensity to adopt highly conjugated, coplanar conformations with reduced rotational freedom compared to imine analogs. Taken together, these multiscale computational insights highlight the exceptional visible-light-driven electron-transfer capability of IQO-COF-1.

Discussion

In summary, we successfully utilized a self-locking strategy to create the novel amide-like isoquinolone-linked COFs from o-vinyl aromatic aldehyde and aromatic amines, and the key step involves the 6π-electrocyclization and subsequent copper-mediated aerobic oxidation after reversible imine bridge formation. Gram-scale reactions also proved feasible. The incorporation of vinyl into the amide-linked COFs enhanced chemical stability and π-electron delocalization in IQO-COFs, resulting in enhanced SET-mediated debromination of α-bromoacetophenone derivatives and Minisci alkylation. This methodology significantly expands the library of COFs with novel linkages.

Methods

Reagents

Unless otherwise noted, all the chemicals and reagents were purchased in analytical purity from commercial suppliers and used directly without further purification. 3,3’-divinyl-[1,1’-biphenyl]-4,4’-dicarbaldehyde (CHO–2) and Am-COF-1 were synthesized according to reported procedures42. Isotopically enriched 13C-labeled terephthalaldehyde was synthesized following a reported method56.

General procedure for synthesis of Im-COFs

In a 250 mL beaker, aromatic amine monomer NH2–1 (28 mg, 0.08 mmol) and aldehyde monomer CHO–1 (22 mg, 0.12 mmol) were dissolved in CH2Cl2 (15 mL) under ambient conditions. A biphasic system was established by slow addition of aqueous HOAc (1 M, 25 mL) along the beaker wall. The reaction mixture was maintained undisturbed at 25 °C for 72 h to allow interfacial growth of crystalline COFs. Upon completion of the reaction, the resulting crystalline solid was isolated via centrifugation and subjected to sequential solvent washing with THF and MeOH until the eluents exhibited optical transparency. After vacuum drying at 60 °C for 12 h, the target Im-COF-1a was obtained as a yellow powder (43 mg, 87% yield). This synthetic protocol was successfully extended to three additional imine-linked COF analogs (Im-COF-2a to Im-COF-4a) through systematic monomer substitution, with detailed stoichiometric parameters and characterization data compiled in Supplementary Table 2.

General procedure for synthesis of IQO-COFs

A 10 mL Schlenk tube was charged with aromatic diamine NH2–1 (21 mg, 0.06 mmol), aldehyde monomer CHO–1 (19 mg, 0.09 mmol), HOAc (0.05 mL), Cu(OAc)2 (5 mg, 0.03 mmol), and anhydrous o-DCB (2 mL). The heterogeneous mixture was homogenized by sonication and subsequently subjected to solvothermal polymerization at 150 °C under an O2 atmosphere for 72 h to promote oxidative cross-coupling. After cooling to ambient temperature, the precipitated crystalline material was isolated via centrifugation and sequentially purified by Soxhlet extraction with THF, ammonium hydroxide, deionized water and MeOH until the supernatant reached optical neutrality. The resulting dark brown powder was dried under vacuum conditions (80 °C, 24 h), yielding IQO-COF-1 (37 mg, 96%). Three structural analogs (IQO-COF-2 to IQO-COF-4) were synthesized under identical conditions through systematic variation of building block stoichiometry, with full synthetic details provided in Supplementary Table 3. Some samples were further subjected to supercritical CO2 treatment to enhance their physicochemical properties.

Gram-scale synthesis of IQO-COF-1

Following the typical procedure, NH2–1 (633 mg, 1.80 mmol), CHO–1 (504 mg, 2.70 mmol), HOAc (1.5 mL), Cu(OAc)2 (138 mg, 0.76 mmol), and o-Dichlorobenzene (60 mL) were combined in a 250 mL flask. The reaction was allowed to proceed for an extended duration of 5 days. Ultimately, 1036.8 mg of IQO-COF-1 was obtained, yielding 97%.

Materials characterization

Liquid-state 1H, 13C, and 19F NMR spectra were recorded at room temperature on a Bruker Avance 600 MHz (1H), 151 MHz (13C), and 564 MHz (19F) spectrometer (Bruker, Germany). High-resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were recorded on a Bruker Apex II mass spectrometer using electrospray ionization. FT-IR spectra were acquired on a Nicolet 6700 spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) equipped with an ATR cell. Solid-state 13C CP/MAS NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance III HD 400 spectrometer (Bruker, Germany). XPS measurements were performed on a Thermo ESCALAB 250 spectrometer using non-monochromatic Al Kα X-rays as the excitation source, and the C 1 s line at 284.8 eV was used as the reference. HR-TEM images were obtained on a JEM-2100F instrument at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. SEM images were obtained on a Hitachi SU 8010 instrument. PXRD analysis was conducted on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation. The specific BET surface area and pore size distribution were measured using a Micrometrics ASAP 2040 instrument at 77 K. Thermal stability was investigated by TGA on a DZ-STA200 analyzer under N2 atmosphere from 303 to 1073 K at a heating rate of 10 K min−1. The Cu content in IQO-COF-1 was determined by ICP-OES on an Agilent 5110 instrument (replicates: 2). UV-Vis absorption spectra were acquired using a SHIMADZU UV-1800 spectrophotometer, equipped with a deuterium lamp (L6380) and a silicon photodiode array detector, in a 1 cm path length quartz cuvette. The topographic images and KPFM surface potential were measured using an atomic force microscope (Bruker Multimode 8 D).

Photoelectrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements were performed on the CHI660E workstation (Chenhua Instruments, China), and the standard three-electrode system included a platinum plate as the counter electrode, an Ag/AgCl electrode as the reference electrode, and a working electrode. The working electrode was prepared as follows: 15 mg of sample was thoroughly mixed with 200 μL isopropanol containing 5% Nafion, and the resulting suspension was carefully loaded on the ITO glass substrate (10 × 25 × 1.1 mm) and dried at 60 °C under vacuum for 1 h. For Mott-Schottky tests, the perturbation was 5 mV with frequencies of 1000, 2000, and 3000 Hz.

Femtosecond TAS analysis

Femtosecond TAS were recorded on a Helios spectrometer (Ultrafast Systems LLC) using a regenerative amplified Ti:sapphire laser system (Coherent, 800 nm, 85 fs, 1 kHz). The 400 nm pump pulse was generated by frequency doubling of the fundamental beam in a BBO crystal, and the probe white-light continuum was produced by focusing a small fraction of the 800 nm beam into a sapphire window. The delay between the pump and probe pulses was controlled by a motorized delay stage, and the signal was recorded at 1 kHz with synchronized chopping at 500 Hz. The instrument response function (IRF) was approximately 120 fs.

In situ DRIFTS test

In situ DRIFTS measurements were performed on a Thermo Fisher iS50 spectrometer equipped with a liquid nitrogen-cooled MCT detector and a custom-designed reaction cell. A gold-coated silicon optical prism was used to enhance surface sensitivity. Spectra were collected over the range of 4000–400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 32 scans per spectrum.

EPR measurement

The generation of phenyl ketone radicals was determined by EPR, which was recorded on a JES-FA200 spectrometer under visible light irradiation using PBN as the spin trapper.

Computational methods

Conformational searches were performed with xtb with the GFN0-xTB method57. To limit the number of conformers, an energy window of 5.0 kcal/mol relative to the minimum was utilized and mirror image conformations were not retained to avoid conformer duplication. Subsequent DFT optimization was performed with Gaussian 16, Rev. A0358. Unless specified otherwise, geometry optimizations were computed with default convergence thresholds and without symmetry constraints. All structures were optimized in the gas phase with the wB97XD59 density functional. The def2-SVP60,61 basis set was employed on all atoms. Frequency analysis was performed at the same level of theory as the geometry optimization to confirm that the optimized structures are local minima or transition states, and to gain the thermal correction to the Gibbs free energy. Single-point energy calculations were conducted on the basis of optimized structures at the wB97XD/def2-TZVP62 level. The solvent effects were taken into account in all calculations by employing the SMD63 (solvent = DMSO) solvation model. The HOMO orbital isosurfaces of molecules are drawn with Multiwfn64 and VMD software65.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Information of this article. All data are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Cote, A. P. et al. Porous, crystalline, covalent organic frameworks. Science 310, 1166–1170 (2005).

Diercks, C. S. et al. The atom, the molecule, and the covalent organic framework. Science 355, eaal1585 (2017).

Geng, K. et al. Covalent Organic Frameworks: Design, Synthesis, and Functions. Chem. Rev. 120, 8814–8933 (2020).

Haug, W. K. et al. A nickel-doped dehydrobenzannulene-based two-dimensional covalent organic framework for the reductive cleavage of inert Aryl C–S bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5521–5525 (2020).

Guo, M. et al. Dual microenvironment modulation of Pd nanoparticles in covalent organic frameworks for semihydrogenation of alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202305212 (2023).

Sasmal, H. S. et al. Heterogeneous C–H functionalization in water via porous covalent organic framework nanofilms: a case of catalytic sphere transmutation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 8426–8436 (2021).

Pang, H. et al. Embedding hydrogen atom transfer moieties in covalent organic frameworks for efficient photocatalytic C–H functionalization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313520 (2023).

Xue, R. et al. Recent progress of covalent organic frameworks applied in electrochemical sensors. ACS Sens. 8, 2124–2148 (2023).

Evans, A. M. et al. High-sensitivity acoustic molecular sensors based on large-area, spray-coated 2D covalent organic frameworks. Adv. Mater. 32, e2004205 (2020).

Das, G. et al. Fluorescence turns on amine detection in a cationic covalent organic framework. Nat. Commun. 13, 3904 (2022).

Evans, A. M. et al. Seeded growth of single-crystal two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Science 361, 52–57 (2018).

Liu, H. et al. Reticular synthesis of highly crystalline three-dimensional mesoporous covalent-organic frameworks for lipase inclusion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 23227–23237 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Harnessing self-repairing and crystallization processes for effective enzyme encapsulation in covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 13469–13475 (2023).

Kumar Mahato, A. et al. Covalent organic framework cladding on peptide-amphiphile-based biomimetic catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 12793–12801 (2023).

Kong, Y. et al. Manipulation of cationic group density in covalent organic framework membranes for efficient anion transport. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27984–27992 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Covalent organic framework membranes for efficient separation of monovalent cations. Nat. Commun. 13, 7123 (2022).

Lyu, H. et al. Covalent organic frameworks for carbon dioxide capture from air. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 12989–12995 (2022).

Meng, Q. W. et al. Guanidinium-based covalent organic framework membrane for single-acid recovery. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh0207 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. An integrated solid-state lithium-oxygen battery with a highly stable anionic covalent organic framework electrolyte. Chem 9, 394–410 (2023).

Mahato, M. et al. Polysulfonated covalent organic framework as active electrode host for mobile cation guests in an electrochemical soft actuator. Sci. Adv. 9, eadk9752 (2023).

Nath, I. et al. Mesoporous acridinium-based covalent organic framework for long-lived charge-separated exciton mediated photocatalytic [4 + 2] annulation. Adv. Mater. 37, 2413060 (2025).

Xu, S. et al. Vinylene-linked two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks: synthesis and functions. Acc. Mater. Res. 2, 252–265 (2021).

Bi, S. et al. Vinylene-bridged two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks via Knoevenagel condensation of tricyanomesitylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 11893–11900 (2020).

Jin, E. Q. et al. Two-dimensional sp2 carbon-conjugated covalent organic frameworks. Science 357, 673–676 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. Vinylene-linked 2D conjugated covalent organic frameworks by Wittig reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202209762 (2022).

Wang, K. et al. Synthesis of stable thiazole-linked covalent organic frameworks via a multicomponent reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 11131–11138 (2020).

Waller, P. J. et al. Conversion of imine to oxazole and thiazole linkages in covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 9099–9103 (2018).

Haase, F. et al. Topochemical conversion of an imine into a thiazole-linked covalent organic framework, enabling real structure analysis. Nat. Commun. 9, 2600 (2018).

Pang, H. et al. One-pot cascade construction of nonsubstituted quinoline-bridged covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Sci. 14, 1543–1550 (2023).

Li, X. T. et al. Construction of covalent organic frameworks via three-component one-pot Strecker and Povarov reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 6521–6526 (2020).

Ren, X. R. et al. Constructing stable chromenoquinoline-based covalent organic frameworks via intramolecular Povarov reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 2488–2494 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Facile transformation of imine covalent organic frameworks into ultrastable crystalline porous aromatic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 9, 2998 (2018).

Seo, J. M. et al. Conductive and ultrastable covalent organic framework/carbon hybrid as an ideal electrocatalytic platform. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 19973–19980 (2022).

Wei, P. F. et al. Benzoxazole-linked ultrastable covalent organic frameworks for photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4623–4631 (2018).

Pyles, D. A. et al. Mechanistic investigations into the cyclization and crystallization of benzobisoxazole-linked two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Sci. 9, 6417–6423 (2018).

Yang, S. et al. Covalent organic frameworks with irreversible linkages via reductive cyclization of imines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 9827–9835 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Robust links in photoactive covalent organic frameworks enable effective photocatalytic reactions under harsh conditions. Nat. Commun. 15, 1267 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Tuning local charge distribution in multicomponent covalent organic frameworks for dramatically enhanced photocatalytic uranium extraction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202303129 (2023).

López-Magano, A. et al. Recent advances in the use of covalent organic frameworks as heterogeneous photocatalysts in organic synthesis. Adv. Mater. 35, e2209475 (2023).

Zhou, Z. B. et al. A facile, efficient, and general synthetic method to amide-linked covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 1138–1143 (2022).

Waller, P. J. et al. Chemical conversion of linkages in covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 15519–15522 (2016).

Wang, W. Q. et al. Construction of amide-linked covalent organic frameworks by n-heterocyclic carbene-mediated selective oxidation for photocatalytic dehalogenation. Chem. Mater. 35, 7154–7163 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. 2D covalent organic frameworks for photosynthesis of α-trifluoromethylated ketones from aromatic alkenes. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 310, 121335 (2022).

Lee, J. et al. Tandem reaction approaches to isoquinolones from 2-vinylbenzaldehydes and anilines via imine formation-6π-electrocyclization-aerobic oxidation sequence. Org. Lett. 22, 474–478 (2020).

Krause, S. et al. Towards general network architecture design criteria for negative gas adsorption transitions in ultraporous frameworks. Nat. Commun. 10, 3632 (2019).

Das, P. et al. Integrating bifunctionality and chemical stability in covalent organic frameworks via one-pot multicomponent reactions for solar-driven H2O2 production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 2975–2984 (2023).

Pan, Q. et al. Ultrafast charge transfer dynamics in 2D covalent organic frameworks/Re-complex hybrid photocatalyst. Nat. Commun. 13, 845 (2022).

Qu, J. D. et al. Engineering covalent organic frameworks for photocatalytic overall water vapor splitting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202502821 (2025).

Proctor, R. S. J. et al. Recent advances in Minisci-type reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13666–13699 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. Photocatalyzed Minisci-type reactions for late-stage functionalization of pharmaceutically relevant compounds. Green. Chem. 26, 3595–3626 (2024).

Tian, H. et al. Cross-dehydrogenative coupling of strong C(sp3)–H with N-heteroarenes through visible-light-induced energy transfer. Org. Lett. 22, 7709–7715 (2020).

Dong, X. et al. Monodispersed CuFe2O4 nanoparticles anchored on natural kaolinite as a highly efficient peroxymonosulfate catalyst for bisphenol A degradation. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 253, 206–217 (2019).

Garza-Sanchez, R. A. et al. Visible light-mediated direct decarboxylative C–H functionalization of heteroarenes. ACS Catal. 7, 4057–4061 (2017).

Basak, A. et al. Covalent organic frameworks as porous pigments for photocatalytic metal-free C–H borylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 7592–7599 (2023).

Younas, M. et al. A rational design of covalent organic framework supported single-atom catalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction: a DFT study. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 51, 758–773 (2024).

Zhu, Y. et al. Sequential oxidation/cyclization of readily available imine linkages to access benzoxazole-linked covalent organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202319909 (2024).

Bannwarth, C. et al. Extended tight-binding quantum chemistry methods. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 11, e1493 (2021).

Frisch M. J. et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01, Gaussian, Inc. (Wallingford, CT, 2019).

Chai, J. D. et al. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom-atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 6615–6620 (2008).

Treutler, O. et al. Efficient molecular numerical integration schemes. J. Chem. Phys. 102, 346–354 (1995).

Weigend, F. et al. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7, 3297–3305 (2005).

Zheng, J. et al. Minimally augmented Karlsruhe basis sets. Theor. Chem. Acc. 128, 295–305 (2011).

Marenich, A. V. et al. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 6378–6396 (2009).

Lu, T. et al. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Humphrey, W. et al. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996).

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22475078 to Y.G.X., 22301091 to W.M.C.) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2662024HXPY003 to W.M.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.M.C. and Y.G.X. conceptualized the research framework and supervised the project. W.Q.W. and X.D.Z. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed data, and validated results. W.S., Y.Q.Z., and D.K.H. conducted part of the material characterizations. W.Q.W. carried out DFT calculations and computational modeling. The manuscript was drafted by W.Q.W., X.D.Z., W.M.C. and Y.G.X., with critical revisions from all co-authors. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, W., Zhao, X., Su, W. et al. Ultrastable amide-like isoquinolone-linked covalent organic frameworks for accelerated photocatalytic single-electron transfer transformation. Nat Commun 17, 370 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67058-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67058-z