Abstract

The development of superconducting quantum processors relies on understanding and mitigating decoherence in superconducting qubits. Piezoelectric coupling contributes to decoherence by mediating energy exchange between microwave photons and acoustic phonons. Although bulk centrosymmetric materials like silicon and sapphire are non-piezoelectric and commonly used as qubit substrates, the lack of centrosymmetry at interfaces may induce piezoelectric losses. This effect was predicted decades ago but never experimentally observed in superconducting devices. Here, we report interface piezoelectricity at aluminum-silicon junctions and demonstrate it as a significant loss channel in superconducting devices. Using aluminum interdigital transducers on silicon, we observe piezoelectric transduction from room to millikelvin temperatures, with an effective electromechanical coupling factor K2 ≈ (3 ± 0.4) × 10−5%, comparable to weakly piezoelectric substrates. Modeling shows this mechanism limits qubit quality factors to Q ~ 104 − 108, depending on surface participation and mode matching. These findings reveal interface piezoelectricity as a major dissipation channel and highlight the need for heterostructure and phononic engineering in next-generation superconducting qubits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The decoherence of superconducting qubits is attributed primarily to material imperfections1. Among these imperfections, decoherence induced by two-level systems—material imperfections with discrete energy levels—poses the most significant limitation for state-of-the-art superconducting qubits2,3. When a superconducting qubit couples to two-level systems, the latter act as electromechanical transducers, causing energy exchange between the microwave photons and acoustic phonons4,5. However, acoustic phonon radiation is not solely caused by two-level systems. Superconducting qubits fabricated on piezoelectric substrates or coupled to piezoelectric transducers can also dissipate through electromechanical transduction and phonon radiation6. This loss channel is generally considered irrelevant because superconducting quantum circuits are often fabricated on centrosymmetric substrate materials, such as silicon and sapphire, where piezoelectricity is nominally absent in the bulk. However, the defects and interfaces of these materials often result in deviations from their ideal bulk properties7,8. In particular, piezoelectricity can arise at the interfaces even when the bulk materials are not inherently piezoelectric8. Electromechanical transduction based on charge-transfer-induced Coulomb forces has been demonstrated by intentionally breaking centrosymmetry, such as by introducing impurities9,10,11,12 or by driving a current13 in non-piezoelectric materials. However, electromechanical transduction could, in principle, exist without introducing these perturbations and could potentially be present in high-quality superconductor-substrate interfaces used in superconducting qubits.

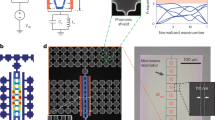

Here, we characterize the piezoelectric transduction in a widely used heterostructure for superconducting qubit fabrication: the aluminum-silicon junction. Crystalline silicon can exhibit complex interface behaviors. First, the distinct environments of atoms near the surfaces can induce surface lattice relaxation or reconstruction14,15,16,17 (Fig. 1a). Theory predicts that lattice relaxation can induce surface piezoelectricity on the sapphire (0001) surface8,18,19, and a similar effect is expected on silicon surfaces. Second, the aluminum film alters the electronic structure of silicon near the interface, generating metal-induced gap states20,21,22. As undoped silicon has a higher work function than aluminum23,24, free electrons transfer from aluminum to silicon so that the heterostructure reaches electrochemical equilibrium while maintaining the continuity of the vacuum energy level across the junction25 (Fig. 1b). Similar to lattice relaxation, the charge transfer leads to an electric dipole at the interface, which can contribute to a piezoelectric response. Both mechanisms can induce piezoelectric interface loss in superconducting qubits by resulting in phonon radiation (Fig. 1c).

a Schematic of the 1 × 2 surface reconstruction of silicon (100) surface. Blue spheres: bulk silicon atoms. Red spheres: surface silicon atoms with unpaired bonds (gray). b Schematic of the energy band diagram at the aluminum-silicon interface and the formation of interface dipoles. The green region indicates the interface electronic states induced by aluminum. EC and EV are the energy of the silicon conduction and valence band edges, EF is the Fermi energy, and ECNP is the charge neutrality point of the silicon interface states. c Interface piezoelectricity induced phonon loss in superconducting qubits. d Experiment setup. Aluminum IDTs fabricated on silicon transmit and receive surface acoustic waves. e Microwave transmission coefficient ∣S21∣ as a function of driving frequency measured for devices with different separation distance d on Sample A (Supplementary Fig. 1a). f Time-domain ∣S21∣ as a function of delay time t. The black arrows indicate the onset time of surface acoustic wave transmission (ts). Inset: Δt = ts − tc as a function of d. Here, ts (tc) is the onset of transmission mediated by the surface acoustic waves (capacitive crosstalk). Dashed line: Linear fit d = v ⋅ Δt gives the silicon surface wave velocity v = 5063 m/s. g Time-gated ∣S21∣ as a function frequency for devices with different d. Inset: Time-gated ∣S21∣ at the electromechanical resonance as a function of d. Dashed line: fit. All measurements are conducted at room temperature.

RESULTS

Piezoelectric transduction at aluminum-silicon interfaces

To study the interface piezoelectricity at aluminum-silicon interfaces, we designed and fabricated aluminum interdigital transducers (IDT) with a finger pitch of 1.05 μm on an undoped silicon (100) substrate. The IDTs electromechanically transduce phonons in a surface acoustic wave (SAW) delay-line configuration (Fig. 1d). We use a split-finger design26 to suppress the internal acoustic reflection of the SAW due to mass loading (Supplementary Fig. 1h). Two mechanisms contribute to the microwave transmission. The first is the capacitive crosstalk between the transmitter and receiver IDTs. The second, which occurs only in the presence of interface piezoelectricity, is the transduction between microwaves and SAWs.

Figure 1e shows the transmission coefficient measured at room temperature on devices with various separation distances d between the IDTs (Sample A, Supplementary Fig. 1a). We observe oscillations of the transmission coefficient on top of the smooth background around the IDT resonance of f = 4.55 GHz. The differing background levels of S21 among the traces arise from variations in the crosstalk levels between devices. (Supplementary Fig. 2) The oscillation results from the interference between the slow-propagating surface acoustic waves and the capacitive crosstalk27. To give a more direct demonstration of the piezoelectric transduction, we convert the data to the time domain by performing a Fourier transform, as shown in Fig. 1f. This gives an approximate impulse response of the device. For all devices, the transmission coefficient peaks at t = tc = 2.5 ns, which is the microwave propagation delay and is insensitive to d. Remarkably, a second peak appears after a longer delay time ts. Unlike tc, ts is proportional to d. Fitting the data by the relation d = v ⋅ (ts − tc) gives v ≈ 5063 m/s (Inset of Fig. 1f), close to the 4920 m/s—the literature reported speed of surface acoustic waves on silicon (100) surface without electrical or mechanical loads28.

To quantitatively study the piezoelectric transduction and SAW propagation, we apply a rectangular filter in the time domain around ts (or “time gating”) and transfer it back to the frequency domain. This procedure removes the contribution from capacitive crosstalk and restores the resonance peak in the frequency-domain response29, as shown in Fig. 1g. The transmission coefficient at resonance (S21,0) decreases with d, which can be attributed to the propagation loss of SAW. The relation between the S21,0 and d can be fit to an exponential function ∣S21,0∣ = Ae−d/2l with fitting parameters A = 1.96 × 10−6 and l = 0.6 mm. The latter corresponds to the decay length of SAW at room temperature. The origin of the propagation loss can arise from various mechanisms, including phonon scattering (Akhiezer damping30), bulk radiation, and diffraction. The observed exponential behavior and the suppression of loss at low temperatures suggest that Akhiezer damping is likely the dominant mechanism, although further experiments are required to reach a definitive conclusion.

We performed the same measurement on devices fabricated with different methods (See Methods section for details) and observed piezoelectric transduction on all six samples studied (Supplementary Fig. 4). These findings indicate that interface piezoelectricity is robust against fabrication process variations and the presence of native silicon oxide at the aluminum-silicon interface. In the superconducting qubit research community, a common approach to evaluate the quality of superconducting film-substrate heterostructures is by measuring the quality factor of superconducting microwave resonators fabricated on these heterostructures. In our study, we fabricated superconducting resonators using the same heterostructures employed in Samples F and G. (Supplementary Fig. 5a and ref. 31). The superconducting resonators etched from the same aluminum-silicon heterostructure revealed internal quality factors of Qi ≈ 106 at the single-photon level (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c). These results demonstrate that the heterojunctions used in this study are of comparable quality to those utilized in high-performance superconducting circuits.

Interface piezoelectricity at millikelvin temperatures

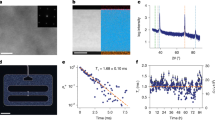

Superconducting qubits operate at cryogenic temperatures, where deviations in electronic and structural properties can influence the piezoelectric response of aluminum-silicon heterostructures. To study the cryogenic response, we fabricated SAW transducers and packaged them for microwave transmission measurements in a dilution refrigerator (Sample B, Supplementary Fig. 1b). Figure 2a shows the microwave transmission coefficient measured at T = 30 mK. By applying time-gating to remove the contribution of capacitive crosstalk (which is stronger due to the sample geometry and measurement setup), a clear electromechanical resonance peak is resolved, with the resonance transmission coefficient ∣S21,0∣ ≈ −99 dB. Varying the excitation power by four orders of magnitude does not change S21,0 (Fig. 2b). The lack of power dependence distinguishes the observed electromechanical transduction from electrostriction and two-level system response, which are nonlinear. The linear interface piezoelectric surface losses observed here also provide an experimental method to distinguish surface piezoelectric and surface two-level system losses in superconducting devices.

a Orange: Measured transmission coefficient at T = 30 mK as a function of frequency on Sample B. Purple: Time-gated transmission coefficient calculated from the orange trace. b, The time-gated transmission coefficient as a function of frequency f with different excitation powers on Sample B at T = 20 mK. c, The time-gated transmission coefficient ratio between Samples B and Sample D (Supplementary Fig. 1d) at the electromechanical resonance as a function of temperature. Gray dashed line indicates the superconducting transition temperature of aluminum.

The measured ∣S21∣max value allows us to use an analytical model32 to calculate the effective electromechanical coupling coefficient K2, the conversion efficiency between electrical and mechanical domains, for the aluminum-silicon IDT (See27 for more details).

Here, f0 is the resonant frequency. Cg = 318 fF is the transducer capacitance. N = 50 is the number of finger periods. Z0 = 50 Ω is the reference impedance. ζ = 1.0836 and γ = 1.414 are geometric factors, and L is the propagation loss of SAW. The Akhiezer damping-induced propagation loss is expected to be negligible at millikelvin temperatures due to the lack of thermal phonons. We confirmed this by cryogenic distance-dependent transmission coefficient measurements on Sample C (Supplementary Fig. 1c), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. We find that ∣S21,0∣ is not sensitive to the separation distance d, and therefore L ≈ 1 at low temperatures. From the results above, we obtain K2 ~ 3 × 10−5% as the effective electromechanical coupling coefficient for aluminum on silicon IDTs. This value is comparable to weakly piezoelectric substrates such as 4H-SiC29. The observed electromechanical coupling strength can lead to a significant surface loss channel for superconducting qubits. We analyze the impact on qubits in a later section.

We study the temperature dependence of the transduction efficiency by comparing the microwave transmission coefficient of the aluminum-on-silicon transducers with a control device (Sample D, Supplementary Fig. 1d). This approach allows us to reduce calibration uncertainties due to resistive losses above the superconducting transition of aluminum. The control device has the same geometry except that the electromechanical transduction is mediated by a 200-nm piezoelectric aluminum nitride film (Supplementary Fig. 8b). Since the piezoelectric response of aluminum nitride has a weak temperature dependence33, the ratio of the microwave transmission coefficients at the electromechanical resonance, \(\Delta | {S}_{21,0}|=| {S}_{21,0}^{{{{\rm{Si}}}}}| /| {S}_{21,0}^{{{{\rm{AlN}}}}}|\) approximates the temperature dependence of the electromechanical transduction at the aluminum-silicon interface. (See Supplementary Fig. 8 for details of the aluminum nitride film and additional data.) As shown in Fig. 2c, Δ∣S21∣ exhibits a non-monotonic dependence on temperature. The variation is less than 6 dB within the experimental temperature range and corresponds to a <50% change in the effective piezoelectric coefficient. These measurements demonstrate that interface piezoelectricity also has a weak temperature dependence. An interesting observation is that Δ∣S21∣ shows a sharp increase as the temperature drops below T = 1.2 K, coinciding with the superconducting transition temperature of aluminum (Fig. 2d). This suggests a potential link between interface piezoelectricity and aluminum’s superconducting transition, though the mechanism remains unclear.

Possible microscopic mechanisms of interface piezoelectricity

As previously discussed, both the surface lattice relaxation and work function mismatch-induced interlayer charge transfer can induce electromechanical transduction. In the latter case, the charge on the silicon side can either exist as thermally activated space charges or be hosted by metal-induced gap states. Depending on the fabrication process, the silicon surface can exhibit different terminations, and a thin layer of silicon oxide may be present on the silicon surface exposed to air. Although this complexity will not affect the symmetry argument (inversion symmetry breaks at material interfaces regardless of the detailed interface configuration), it complicates the microscopic mechanisms of the piezoelectric response.

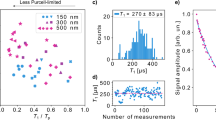

To gain further insights into the microscopic origins, we study how the transduction depends on silicon surface preparation methods and a DC bias between the aluminum IDT and silicon substrate, as shown in Fig. 3a. We apply a DC bias voltage to an aluminum electrode on the backside of the substrate while keeping the signal and ground electrodes of the IDTs at DC ground. The aluminum back electrode covers the majority of the substrate area and makes ohmic contact to the silicon substrate with a sintering process. (See Methods) We investigate two samples with identical geometry, but one has the native oxide removed by hydrofluoric acid (Sample E, Supplementary Fig. 1e) before the aluminum deposition. Without the bias voltage, the two samples show nearly identical transduction efficiency (Fig. 3b). The presence of the oxide and its thickness may affect the lattice structure near the interface, and therefore, affect the piezoelectric response8. By contrast, the built-in electrical potential across the Al/Si junction is primarily set by the work-function mismatch of the two bulk materials in the thin-oxide regime, so the piezoelectric response arising from interface charge transfer is expected to be less sensitive to whether a native oxide is present. In addition, the finite-element analysis discussed later indicates the piezoelectric transduction observed here is significantly stronger than the prediction in ref. 8. The lack of dependence of the transduction efficiency on the presence of native oxide and the larger transduction efficiency suggest that lattice relaxation is probably not the dominant contributor to interface piezoelectricity.

a Schematics of the bias-dependent measurement. Top: measurement wiring. Bottom: cross-section of the device. (Also see Supplementary Fig. 12a). b Zero-bias time-gated microwave transmission coefficient measured on Samples A and E at room temperature. c Time-gated transmission coefficient ∣S21∣ as a function of frequency f and bias voltage VSi − VAl measured on Sample A. The separation distance between the IDTs is d = 1323 μm. d Linecut of the data in panel c at the resonant frequency. e Same as c, measured on Sample E (Supplementary Fig. 1e), where native oxide is removed. f Linecut of the data in panel e at the resonant frequency.

When a bias voltage is applied, Sample A, with the native oxide present, shows enhanced piezoelectric transduction when VSi > VAl and suppressed transduction when VSi < VAl (Fig. 3c, d). This response is consistent with the interface charge transfer picture, as the charge distribution depends on both the work function mismatch and an external electrical potential difference. Furthermore, we used the finite-element method to simulate the charge distribution near an ideal aluminum-silicon junction in response to a bias voltage (Supplementary Fig. 9). The resulting polarity aligns with the experimental results. Interestingly, Sample E, with native oxide removed, does not show a bias-dependence (Fig. 3e, f). A possible explanation is that the electrical potential drop across the accumulation layer near the interface is too low to alter the interface charge distribution when no oxide is present. This observation indicates that the charge that contributes to the piezoelectric response is likely from the surface states of silicon, which are concentrated near the aluminum-silicon interface, instead of thermally activated bulk charges. This is further supported by the temperature dependence of the piezoelectric response. The distribution of the thermally activated space charge is sensitive to temperature34. Since we observed a weak temperature dependence (Fig. 2c), the space charge is less likely to be the dominant mechanism. Considering all the observations, the interface charge transfer between aluminum and the metal-induced gap states in silicon is likely the primary contributor to interface piezoelectricity, although further investigation is required for a definitive conclusion.

Impact on superconducting qubits

Despite the uncertainties in the microscopic mechanism, the experimentally observed interface piezoelectricity will constitute a loss channel for superconducting qubits on silicon.

Here, we adopt the circuit model shown in Fig. 4a to estimate the impact of interface piezoelectricity on the lifetime of superconducting qubits35. The lossless transmon qubit is characterized by its junction inductance LJ and shunt capacitance Cg. Similar to modeling an antenna with an effective radiation impedance, we use the acoustic radiation admittance Ya to describe the conversion of the qubit electrical energy into acoustic radiation, i.e., the piezoelectric loss. For the IDTs used in the experiment, Ya can be directly obtained from the effective piezoelectric coupling coefficient K227. We use the experimentally observed Ya in the IDT geometry to calculate the quality factor of a transmon qubit with a shunt capacitor identical to the IDTs used in the experiment (Fig. 4b). The result is shown in Fig. 4c. At the electromechanical resonance, the piezoelectric loss-limited quality factor of the qubit is \({Q}_{\,{{\rm{piezo}}}}^{{{\rm{IDT}}}\,}\approx 7\times 1{0}^{4}\), indicating a significant loss channel.

a A circuit model of the transmon qubit with interface piezoelectric loss. Electromechanical transduction is modeled by an acoustic radiation admittance \({Y}_{a}^{q}(\omega )\), where ω = 2πf is the angular velocity. b Schematic of a transmon with an interdigital capacitor. Phonons are radiated as surface acoustic waves near resonance. c The calculated quality factor of a transmon qubit with an interdigital shunt capacitor identical to the IDTs used in the experiment near the electromechanical resonance. d A schematic of the transmon qubit with a coplanar shunt capacitor. e Simulated spatial distribution of the mechanical energy density within the silicon substrate. The coplanar capacitor is driven at frequency f = 4.5 GHz, with the total electrostatic energy equal to that of one microwave photon at f = 4.5 GHz. The scale bar represents 50 μm. The positions of the two aluminum electrodes are indicated, though not drawn to scale in the vertical direction. f A schematic of the transmon qubit with a parallel-plate shunt capacitor. g Same as e, for the parallel-plate capacitor. Scale bar represents 5 μm.

Next, we study the interface piezoelectric loss for more commonly used transmon qubit capacitor geometries shown in Fig. 4d, f. The loss rate induced by interface piezoelectricity in these transmon qubits can differ from the IDT geometry of Fig. 4b due to different surface participation (See Supplementary Fig. 11) and electromechanical mode matching. We use finite-element analysis to estimate interface piezoelectric losses in transmon qubits with 125-fF shunting capacitors with concentric coplanar (“planar”, Fig. 4d) and parallel-plate (PPC, Fig. 4f) geometries. The axial symmetry is used to simplify the simulation while keeping the footprint comparable to a typical transmon qubit36. The dimensions of the two geometries are shown in Supplementary Fig. 10.

Finite-element analysis requires defining a piezoelectric region within the silicon substrate with a fixed thickness and piezoelectric coupling coefficient. However, our SAW experiment only determines K2. This effective lumped parameter depends on the distributions of electromagnetic and mechanical fields, as well as the properties and thickness of the piezoelectric material. The same value of K2 can arise from different combinations of an effective piezoelectric film with thickness h and the piezoelectric coupling coefficient e33.

To simulate the qubit loss in different capacitor geometries, we need to know the effective piezoelectric film properties (h, e33). We use finite-element analysis to find combinations of (h, e33) that give the experimentally observed K227 in an IDT (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d). Next, we use these (h, e33) combinations to calculate the qubit loss in different capacitor geometries. Figure 4e, g show the radiated mechanical energy density distribution under the qubit capacitors for h = 10 nm and e33 = 0.67 C/m2 in the planar and PPC geometries. The interface piezoelectricity-limited quality factors for the planar and parallel plate capacitor are \({Q}_{\,{{\rm{piezo}}}}^{{{\rm{planar}}}\,}\approx 6\times 1{0}^{7}\) and \({Q}_{\,{{\rm{piezo}}}}^{{{\rm{PPC}}}\,}\approx 7\times 1{0}^{4}\), respectively. The large difference between \({Q}_{{{{\rm{piezo}}}}}^{\,{{\rm{planar}}}\,}\) and \({Q}_{\,{{\rm{piezo}}}}^{{{\rm{PPC}}}\,}\) arises from their different interface participation ratios. We repeat the same Qpiezo calculations with several different (h, e33) combinations that match the experimentally observed K2 (Supplementary Fig. 10d). At fq = 4.5 GHz, similar Qpiezo values are found in the range of \({Q}_{\,{{\rm{piezo}}}}^{{{\rm{planar}}}\,}\approx 1-5\times 1{0}^{7}\) and \({Q}_{\,{{\rm{piezo}}}}^{{{\rm{PPC}}}\,}\approx 2-6\times 1{0}^{4}\) for the two geometries. We find a small decrease of Qpiezo for (h, e33) combinations with large h and smaller e33. This observation is consistent with improved piezoelectric mode matching between the electric and strain fields away from the top surface, which is a strain node. We note that these simulations provide only a rough estimate of the impact of interface piezoelectricity on the performance of superconducting qubits. In addition to the choice of the effective piezoelectric layer thickness, the effective electromechanical coupling coefficient K2 can vary depending on the specific acoustic modes. However, this variation is typically within the same order of magnitude37 and does not significantly affect the overall order-of-magnitude estimation.

DISCUSSION

These results establish interface piezoelectricity as a newly identified loss channel for superconducting qubits. State-of-the-art superconducting qubits on silicon have recently achieved quality factors of Q ≈ 7.7 × 106 38. Our predicted interface piezoelectric surface loss limit of \({Q}_{\,{{\rm{piezo}}}}^{{{\rm{planar}}}\,}\approx 6\times 1{0}^{7}\) is already close to the state-of-the-art values. These suggest that interface piezoelectric surface losses could already be significant in state-of-the-art superconducting qubits. In addition, unlike TLS losses, the piezoelectric loss is a linear effect and does not decrease at high power. This may explain the saturated high-power quality factors of resonators38, including our results shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

The qubit loss induced by interface piezoelectricity originates from the heterostructure material properties of the qubits rather than material disorders such as defects or amorphous interfaces. As such, even high-quality metal-substrate interfaces will suffer from this loss mechanism. Therefore, delicate engineering at the device level is essential to mitigate this loss mechanism. These might include shielding qubits from the resonant phonon bath using phononic metamaterials39,40, and interface charge transfer engineering by choosing different qubit heterostructures.

On the positive side, the observed reasonably strong and process-insensitive transduction opens up the possibility of realizing electromechanical quantum transduction with the interface piezoelectricity. Current approaches for electromechanical transduction require either piezoelectric materials41,42 or static charge induced by an externally applied voltage43,44, which increases device fabrication and biasing complexity and noise. Utilizing interface piezoelectricity may eliminate both problems, allowing high-performance electromechanical quantum transducers to be fabricated using a relatively simple and industrially compatible process. Finally, metal-oxide-semiconductor structures could also enhance the charge transfer and transduction strength using large biases for classical transducer and filter applications.

METHODS

Sample Fabrication

Samples A, B, C, E, F, and G (Supplementary Fig. 1) were fabricated on float-zone intrinsic (100) silicon substrates with room temperature resistivity > 104Ω cm. The aluminum films, unless noted otherwise, are deposited on the (100) surface of an undoped silicon substrate. Sample D was fabricated on substrates obtained from Kyma Technologies, which have a 200 nm aluminum nitride film on float-zone intrinsic (111) silicon wafers with room temperature resistivity > 104Ω cm.

Sample A was fabricated by first depositing a 100-nm aluminum film on the backside of the silicon chip using an electron beam evaporator. The chip was subsequently annealed at 420 °C in a forming gas atmosphere to create Ohmic aluminum-silicon contacts. Finally, the IDTs were formed by depositing a 50 nm aluminum film on the front side of the chip with an electron-beam-lithography-defined mask in an electron beam evaporator, followed by a lift-off process. The chip was exposed to an oxygen plasma before the aluminum deposition to clean the aluminum-silicon interface.

Samples B and C were fabricated following a two-step lift-off process. The IDTs were first formed following the same process for Sample A. The coplanar waveguides were then formed by depositing a 100 nm aluminum film on the chip with a photolithography-defined mask in an electron beam evaporator, followed by a lift-off process. The sample was wire-bonded to a printed circuit board for cryogenic measurements.

Sample D was fabricated following the same process as Sample A on the aluminum nitride substrate.

Sample E was fabricated following a lift-off process similar to that for Sample A. The difference is that the sample was dipped in a 10:1 buffered hydrofluoric acid solution for 16s to remove the surface oxide after the oxygen plasma treatment.

Sample F was fabricated using an etch process. The substrate was first extensively cleaned with piranha solution, diluted hydrochloric acid solution, and 25:1 hydrofluoric acid solution. A 50 nm aluminum film was then deposited using a DC magnetron sputtering system. Finally, the IDTs were formed by electron beam lithography and a plasma etch.

Sample G was fabricated following a two-step etch process. The substrate cleaning and aluminum deposition process was identical to those for Sample F. Afterwards, electron beam lithography and chlorine-based plasma etch (first etch step) were performed to form the IDT fingers and other fine features. Finally, photolithography and a tetramethylammonium hydroxide-based wet etch (second etch step) were performed to form the coarse feature, including the waveguide.

The information of Sample A-G is summarized in Supplementary Table. 1.

The microwave resonator was fabricated with an etch process. After the substrate cleaning and aluminum deposition process identical to those for Sample F, the coplanar waveguide and the microwave resonator were formed by photolithography and a wet etch.

Measurement

Room temperature measurements were performed using a radio-frequency probe station and a vector network analyzer (VNA). The microwave power delivered to the end of the probes was 15 dBm. The bias-dependence measurements were performed using radio-frequency bias tees. The DC bias voltage was applied using a source meter. The cryogenic measurements were performed in a dilution refrigerator. The power delivered to the wire bonding pads of the devices was −29 dBm unless otherwise indicated. A high-electron-mobility transistor (HEMT) is used to amplify the transmitted signal, while circulators are used to isolate the reflection from the HEMT to the device (See Supplementary Fig. 12b). The power-dependent quality factor of the microwave resonator was obtained by measuring the transmission coefficient of the device in a dilution refrigerator using a VNA. The details are described in ref. 31.

Data processing

All microwave measurements were performed using continuous-wave excitation. The time-domain responses in Fig. 1f and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 7b were obtained by applying an inverse fast Fourier transform to the complex S21 spectra, with a Hamming window applied to suppress spectral leakage.

To extract the time-gated S21, the inverse fast Fourier transform was first performed without windowing. The peak corresponding to SAW-mediated transmission was identified, and a temporal bandpass filter was applied to retain only the signal within a window centered on this peak, setting the remainder to zero. A subsequent fast Fourier transform yielded the time-gated S21 in the frequency domain. The gating procedure is illustrated schematically in Supplementary Fig. 3a. Although the size of the time window is a free parameter, the results, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3b, c, are largely insensitive to the exact window width provided that the SAW-mediated peak is fully included and the capacitive crosstalk peak is excluded.

Data availability

The data generated in this study have been deposited in Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/records/17620739.

References

Siddiqi, I. Engineering high-coherence superconducting qubits. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 875–891 (2021).

Anderson, P. W., Halperin, B. I. & Varma, cM. Anomalous low-temperature thermal properties of glasses and spin glasses. Philos. Mag. A J. Theor. Exp. Appl. Phys. 25, 1–9 (1972).

Phillips, W. A. Two-level states in glasses. Rep. Prog. Phys. 50, 1657 (1987).

Ioffe, L. B., Geshkenbein, V. B., Helm, C. & Blatter, G. Decoherence in superconducting quantum bits by phonon radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 057001 (2004).

Chenu, A., Shiau, S.-Y. & Combescot, M. Two-level system coupled to phonons: full analytical solution. Phys. Rev. B 99, 014302 (2019).

Jain, V. et al. Acoustic radiation from a superconducting qubit: from spontaneous emission to Rabi oscillations. Phys. Rev. Appl. 20, 014018 (2023).

Turiansky, M. E. & Van de Walle, C. G. Dielectric loss due to charged-defect acoustic phonon emission. APL Quantum 1, 026114 (2024).

Georgescu, A. B. & Ismail-Beigi, S. Surface piezoelectricity of (0001) sapphire. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 064065 (2019).

Hwang, E. & Bhave, S. A. Transduction of high-frequency micromechanical resonators using depletion forces in p-n diodes. IEEE Trans. Electron Dev. 58, 2770–2776 (2011).

Kanygin, M., Joy, A. P. & Bahreyni, B. Localized mechanical actuation using pn junctions. Sci. Rep. 9, 14885 (2019).

Ransley, J. H. T., Durkan, C. & Seshia, A. A. A depletion layer actuator. In Proc. TRANSDUCERS 2007-2007 International Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems Conference, 1393–1396 (IEEE, 2007).

Yang, M.-M. et al. Piezoelectric and pyroelectric effects induced by interface polar symmetry. Nature 584, 377–381 (2020).

Park, D.-S. et al. Induced giant piezoelectricity in centrosymmetric oxides. Science 375, 653–657 (2022).

Gupta, R. P. Lattice relaxation at a metal surface. Phys. Rev. B 23, 6265–6270 (1981).

Lee, Y. J., Kim, S., Hwang, C.-S., Lee, C. & Hwang, C. Reconstruction on si(100) surfaces. Phys. Rev. B 50, 11204–11207 (1994).

Kern, R. & Müller, P. Elastic relaxation of coherent epitaxial deposits. Surf. Sci. 392, 103–133 (1997).

Ramstad, A., Brocks, G. & Kelly, P. J. Theoretical study of the si(100) surface reconstruction. Phys. Rev. B 51, 14504–14523 (1995).

Shen, S. & Hu, S. A theory of flexoelectricity with surface effect for elastic dielectrics. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 58, 665–677 (2010).

Dai, S., Gharbi, M., Sharma, P. & Park, H. S. Surface piezoelectricity: size effects in nanostructures and the emergence of piezoelectricity in non-piezoelectric materials. J. Appl. Phys. 110, 104305 (2011).

Heine, V. Theory of surface states. Phys. Rev. 138, A1689–A1696 (1965).

Louie, S. G. & Cohen, M. L. Self-consistent pseudopotential calculation for a metal-semiconductor interface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 35, 866–869 (1975).

Louie, S. G. & Cohen, M. L. Electronic structure of a metal-semiconductor interface. Phys. Rev. B 13, 2461–2469 (1976).

Allen, F. G. & Gobeli, G. W. Work function, photoelectric threshold, and surface states of atomically clean silicon. Phys. Rev. 127, 150–158 (1962).

CRC Handbook. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 88th edn (CRC Press, 2007).

Grundmann, M. The Physics of Semiconductors: An Introduction Including Nanophysics and Applications. Graduate Texts in Physics, 3rd edn (Springer International Publishing AG, 2016).

Bristol, T., Jones, W., Snow, P. & Smith, W. Applications of double electrodes in acoustic surface wave device design. In Proc. 1972 Ultrasonics Symposium, 343–345 (IEEE, 1972).

See Supplemental Materials.

Tarasenko, A., Čtvrtlík, R. & Kudělka, R. Theoretical and experimental revision of surface acoustic waves on the (100) plane of silicon. Sci. Rep. 11, 2845 (2021).

Yu, P. L. & Bhave, S. A. Acoustic delay lines to measure piezoelectricity in 4h silicon carbide. In Proc. Joint Conference of the European Frequency and Time Forum and IEEE International Frequency Control Symposium (EFTF/IFCS), 139–142 (IEEE, 2017).

Li, D. & Cahill, D. G. Attenuation of 7 GHz surface acoustic waves on silicon. Phys. Rev. B 94, 104306 (2016).

Zhang, Z.-H. et al. Acceptor-induced bulk dielectric loss in superconducting circuits on silicon. Phys. Rev. X 14, 041022 (2016).

Datta, S. Surface Acoustic Wave Devices (Prentice-Hall, 1986).

Kano, K. et al. Temperature dependence of piezoelectric properties of sputtered aluminum nitride on silicon substrate. IEEJ Trans. Sens. Micromach. 126, 158–163 (2006).

Heiman, F. P. & Warfield, G. Space charge capacitance of an intrinsic semiconductor film. J. Appl. Phys. 36, 3206–3211 (1965).

Kim, J., Grisso, B. L., Kim, J. K., Ha, D. S. & Inman, D. J. Electrical modeling of piezoelectric ceramics for analysis and evaluation of sensory systems. In Proc. IEEE Sensors Applications Symposium 122–127 (IEEE, 2008).

Krantz, P. et al. A quantum engineer’s guide to superconducting qubits. Appl. Phys. Rev. 6, 021318 (2019).

Han, X., Zou, C.-L. & Tang, H. X. Multimode strong coupling in superconducting cavity piezoelectromechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 123603 (2016).

Tuokkola, M. et al. Methods to achieve near-millisecond energy relaxation and dephasing times for a superconducting transmon qubit. Nat. Commun. 16, 5421 (2025).

Chen, M., Owens, J. C., Putterman, H., Schäfer, M. & Painter, O. Phonon engineering of atomic-scale defects in superconducting quantum circuits (2023). Sci. Adv. 10, eado6240 (2024).

Odeh, M. et al. Non-Markovian dynamics of a superconducting qubit in a phononic bandgap. Nat. Phys. 21, 406–411 (2025).

Mirhosseini, M., Sipahigil, A., Kalaee, M. & Painter, O. Superconducting qubit to optical photon transduction. Nature 588, 599–603 (2020).

Meesala, S. et al. Non-classical microwave-optical photon pair generation with a chip-scale transducer. Nat. Phys. 20, 871–877 (2024).

Bozkurt, A. et al. A quantum electromechanical interface for long-lived phonons. Nat. Phys. 19, 1326–1332 (2023).

Zhao, H., Chen, W. D., Kejriwal, A. & Mirhosseini, M. Quantum-enabled continuous microwave-to-optics frequency conversion (2024). Nat. Nanotechnol. 20, 602–608 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Rohin Tangirala for experimental assistance, Francois Leonard for fruitful discussions, as well as Robert Schoelkopf and Srujan Meesala for valuable feedback on the manuscript. This work was primarily funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division under Contract No. DE-AC02-05-CH11231 within the Phonon Control for Next-Generation Superconducting Systems and Sensors program (KCAS23) for device design, modeling, measurements, imaging, and theory. Additional support was provided by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the Office of Naval Research under Grant No. FA9550-23-1- 0333 (device fabrication and lithography development), by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231 within the Quantum Coherent Systems Program KCAS26 (supporting microwave resonator measurements), and an unrestricted gift from Google (transducer characterization). The devices used in this work were fabricated at UC Berkeley’s Marvell Nanofabrication Laboratory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S. conceived and supervised the work. H.Z., K.G., and S.J. fabricated the devices with assistance from S.A.. M.O. Z.Z., H.Z., and K.G. built the measurement instruments. H.Z. and S.J. performed the measurements. H.Z., K.Y., and A.S. analyzed the data. E.L., H.Z., K.Y., and S.G. performed theoretical modeling and simulations. H.Z. and A.S. wrote the manuscript with the input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Tobias Junginger and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, H., Li, E., Godeneli, K. et al. Observation of interface piezoelectricity in superconducting devices on silicon. Nat Commun 17, 377 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67066-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67066-z