Abstract

On-chip whispering-gallery-mode cavities enable versatile bosonic wave manipulation but typically rely on near-field evanescent coupling. Here we experimentally demonstrate broadband far-field phonon coupling in a valley metamaterial cavity integrated with a Dirac-cone waveguide—termed a “Dirac strip”. The far-field coupling is confirmed by transmission spectroscopy and spatiotemporal field mapping over distances up to approximately five wavelengths, enabling multiplexed, distance-robust coupling pathways that overcome near-field limitations. By combining near-field and far-field cavities on the same substrate, we achieve amplification and control of non-Hermitian dynamics through loss and distance modulation of sympathetic resonances, directly resolved via piezo-laser interferometry. This work establishes a scalable phononic platform for far-field coupling and paves the way for parallel topological wave processors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Whispering gallery modes (WGMs), characterized by continuous reflections along curved cavity interfaces1, have become foundational elements in waveguide-cavity coupling systems with broad utility across acoustics2, elastodynamics3, optics4, and electronics5. These modes enable key functionalities including low-threshold lasing6, enhanced sensing7, and critical coupling – where dissipative loss (Γ) equals radiative loss (γ)8. The pursuit of advanced on-chip coupling schemes has garnered considerable interest in scalable information processing3,4,5,8.

Recent advances in enhancing waveguide-cavity coupling have exploited non-Hermitian physics in waveguide-cavity systems through deliberate modulation of external loss and gain. This approach enables phenomena such as exceptional points9,10 that yield nonlinear dynamics11, nonreciprocal transmission12, and spectral flows13,14. Non-Hermitian systems are non-conservative and characterized by energy exchange15,16, encompassing three situations: loss only, gain only, or both. Concurrently, topological metamaterials have transformed continuum waveguide and cavity design, giving rise to topological edge states (TESs)17,18, topological whispering gallery modes (TWGMs)19,20,21, and corner states22,23. These bosonic wave counterparts encode topological protection and synthesized chirality24,25, liberating cavity designs from perfect circular geometries26,27. Valley-phononic TWGMs can exhibit Hermitian20 or non-Hermitian behaviour through unit cell-level modulation of gain and loss26.

Despite these advances, achieving far-field coupling remains a fundamental challenge in waveguide-cavity systems28. All approaches for coupling in such systems to date rely on evanescent near-fields, which intrinsically confine energy transfer to sub-wavelength distances. Far-field coupling schemes, by contrast, if achievable would enable unprecedented spatial flexibility for on-chip integration, full utilization of wave degrees of freedom, and direct observation of inter-cavity dynamics in multi-resonator architectures. Yet their construction has not been possible owing to the absence of broadband, robust, and distance-insensitive coupling mechanisms.

In this work, we experimentally demonstrate broadband, robust waveguide-cavity far-field coupling. This is achieved through topological phonon interactions in on-chip valley waveguide-cavity systems using a Dirac-cone waveguide strip (a ‘Dirac strip’), which enables long-distance coupling beyond conventional near-field limits and markedly improves coupling efficiency. This topological channel mediates enhanced waveguide-cavity coupling through the broadband and robust features of valley metamaterials. By co-locating near- and far-field cavities, we observe sympathetic resonances—simultaneous resonance in both cavities at a single frequency—and reveal non-Hermitian dynamics modulated by material loss and inter-cavity distance.

Results

Valley metamaterial circuits: three configurations

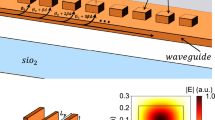

Three valley metamaterial circuits are investigated in this work (Fig. 1a). Sample 1 is a far-field cavity (FFC) waveguide circuit composed of triangular pillars, with side length sl = 500 μm and height hp = 292 μm (see Fig. 1b). Samples 2 and 3 correspond to the near-field cavity (NFC) waveguide circuit and dual-cavity waveguide circuit, respectively, with sl = 526 μm and hp = 289 μm. All samples share the same lattice constant a = 641 μm and wafer thickness et = 525 μm, with geometrical parameters detailed in Supplementary Table 1. The rhombus-shaped cavities have side length 7a, and the waveguides span 38a horizontally. Rightward terminal boundaries are oblique to suppress reflections. The Dirac strips maintain a 3a width horizontally, extending vertically 7 layers for FFC structures and 3 layers for NFC structures. In dual-cavity configurations, the Dirac strips of NFC and FFC are positioned with a 7a (center-to-center) horizontal separation. Simplified models of the three samples are shown in Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3.

a Experimental samples for the (1) FFC-waveguide, (2) NFC-waveguide, and (3) dual-cavity waveguide circuits. The crystallographic directions [100] and [001] of silicon are aligned with the x- and z-axes, respectively. b (top) PnC plate, (middle) unit cell, and (bottom) Brillouin Zone taken from Sample 1. Geometrical parameters include lattice constant a, pillar side length sl, pillar height hp, silicon wafer thickness et, and substrate thickness es = et - hp. Topological phases are controlled by tuning the rotation angles θ of the triangular pillars. c, d Band structures of the unit cell for θ = 0° (top panels) and θ = ±20° (bottom panels) are shown for Sample 1 in (c) and Samples 2 and 3 in (d). The color scale indicates the ratio of |uz| to the total displacement |ut| in the unit cell, defined by \({\eta }_{z}=\int |{u}_{z}|dV/\int |{u}_{t}|dV\). Insets show unit cell schemes and a zoom-in of the dispersion for θ = 0°.

We fabricated valley phononic crystal (PnC) plates by etching arrays of triangular pillars in a honeycomb lattice (see Methods). Dirac cones appear at the K point of the Brillouin zone for θ = 0° (Fig. 1c, d, upper panels), while material anisotropy introduces a minor band gap (insets). Rotating the pillars to θ = 20° (phase A) and θ = –20° (phase B) generates broad band gaps for antisymmetric plate waves (Fig. 1c, d, lower panels), with slight frequency shifts of the Dirac cones between Sample 1 and Samples 2–3.

The unit cell of triangular pillars possesses C3v symmetry when θ equals zero, and topological phase transitions are induced by changing the rotation angle θ to break this symmetry. These valley PnCs support the topological states reported previously24,29. We adopt this classic paradigm and fabricate all three samples on silicon wafers to explore novel mechanisms of wave propagation.

Single far-field waveguide-cavity phonon system

Our first on-chip waveguide-cavity phonon system integrates an FFC coupled to a straight waveguide via a Dirac strip (Fig. 2a), to enable the observation of far-field coupling. PnCs A and B exhibit opposite topological phases (Supplementary Fig. 4), and their interface supports topological edge states (TESs, Supplementary Fig. 5) and topological whispering gallery modes (TWGMs, Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 6).

a Optical micrograph of the on-chip far-field cavity (FFC) connected to straight waveguide via a Dirac strip (D = 7 × 0.866a, highlighted in yellow). Adjacent topologically distinct phononic crystals (PnCs) A and B define interfaces (red lines), along which blue arrows indicate the incident wave path. b Top: uz distributions for TWGM1-TWGM4 when hp = 292 μm. Bottom: TWGM eigenfrequencies as a function of the pillar height hp with sl = 500 μm. The colour map represents the ratio of |uz| to the total displacement |ut| in the supercell. c Computed map of normalized |uz| at the waveguide outlet (left) and cavity bottom edge (right), plotted against frequency and cavity-waveguide distance (i.e., the Dirac strip length) D, with the Dirac strip shown in (a). Left inset (shown in (a)): field distribution showing enhanced coupling at 1.93 MHz (D = 10 × 0.866a). d As (c) but with a PnC-A domain instead of the Dirac strip. Right inset (shown in (a)): map of uz at 1.93 MHz for D = 10 × 0.866a, in the undercoupled state.

The cavity eigenfrequencies result from embedding PnC-B within a PnC-A domain (Fig. 2b). Within the antisymmetric plate wave band gap, four TWGMs (TWGM1-TWGM4) are identified (black solid lines), exhibiting a decrease in frequency with increasing hp. For the experimental sample (hp = 292 μm), the TWGM1 at 1.798 MHz couples to bulk modes, evidenced by uz field leakage beyond the cavity. In contrast, TWGM2 (1.842 MHz), TWGM3 (1.93 MHz) and TWGM4 (1.98 MHz) remain confined within the band gap of both PnCs A and B, with uz distributions localized along the cavity path.

To characterize the far-field phonon coupling, we show in Fig. 2c computed maps of normalized |uz| at the waveguide outlet (left panel) and cavity edge (right panel) plotted versus frequency and cavity-waveguide distance D, using a model matching the experimental sample in Fig. 2a. With the Dirac strip (θ = 0°) bridging the cavity and waveguide, four outlet |uz| minima (D1-D4) emerge and shift toward the TWGM1-TWGM4 eigenfrequencies as D increases, whereas four cavity |uz| maxima (P1-P4) simultaneously develop, confirming TWGMs generation. These TWGMs enable enhanced coupling at large D—e.g., outlet D3 = 0.27 at D = 10 × 0.866a and 1.93 MHz (see the left inset in Fig. 2a, corresponding to Fig. 2c). By comparison, Fig. 2d shows Dirac-strip-free counterparts—in which the Dirac strip is replaced by a PnC-A domain—where only minima D2-D3 persist (D1/D4 absent). These minima vanish rapidly with increasing D owing to diminished amplitude of TWGM2-TWGM3, yielding poor energy transfer (e.g., at D = 10 × 0.866a and 1.93 MHz, see the right inset in Fig. 2a, corresponding to Fig. 2d).

This enhanced far-field coupling depends on the cavity dissipation loss Γ, radiation loss γ, and resonance ω0 (Supplementary Fig. 2). The transmission coefficient \(T=|1-\frac{\gamma }{i\left(\omega -{\omega }_{0}\right)+\Gamma+\gamma }|\) reaches a minimum value \({T}_{\min }=\frac{\Gamma }{\Gamma+\gamma }\). With the Dirac strip (Supplementary Fig. 7), the effect of the value of γ dominates over that of Γ even at large D, amplifying far-field coupling. This enhancement stems from the Dirac strip’s topological protection and broadband properties30,31. The modeled antisymmetric bulk-wave branches emerge with wave energy confined to the Dirac strip, whereas their frequency ranges occupy the eigenfrequencies of TWGM1, TWGM3 and TWGM4 (Supplementary Fig. 8). These guided bulk-wave branches are modulated by strip pillar rotation. For example, at strip pillar angle θ = 10°, these bulk-wave branches occupy exclusively the TWGM4 frequency, directly shaping the D1-D4 and P1-P4 |uz| versus θ profiles (Supplementary Fig. 8).

In situ time-resolved observations are performed by spatially mapping uz over the waveguide-cavity circuit (see Methods). Normalized |uz| is measured at representative positions: Pure PnC (i.e., unmodified PnC), FFC, Inlet, and Outlet (Fig. 2a). As shown in Fig. 3a, the FFC |uz | (blue curve) exhibits peaks P1-P4 at 1.808, 1.867, 1.937 and 1.976 MHz, corresponding to the calculated frequencies of TWGM1-TWGM4. Compared to the Pure PnC case (gray background), the outlet |uz | (red curve) shows distinct minima at D3 ≈ 0.32 (1.937 MHz) and D4 ≈ 0.30 (1.976 MHz).

a Normalized |uz| measured at locations on the sample as marked in Fig. 2a (Pure PnC, FFC, Inlet, Outlet), excited by a pulsed source centered at fc = 1.8 MHz. FFC spectrum (blue curve) shows peaks P1-P4 at 1.808, 1.867, 1.937 and 1.976 MHz, respectively. b Measured |uz| distributions at frequencies corresponding to P2-P4, together with the in-plane wave flux (bold arrows). Lines outline the waveguide, cavity path, and truncated terminal. c Simulated spectra showing FFC peaks P1-P4 (blue) and outlet dips D1-D4 (red) at 1.794, 1.843, 1.929 and 1.976 MHz. Insets show zoomed-in views of the outlet |uz| at D2-D4: numerical data are shown by the dotted lines, and theoretical results by the red solid lines. d Simulated uz distributions at frequencies corresponding to P2-P4 with in-plane energy flux (bold arrows).

The |uz| field maps confirm incident wave coupling from waveguide to cavity (Fig. 3b). Minimal energy reaches the truncated outlet at frequencies corresponding to D3/D4 owing to TWGM3/TWGM4 excitation, whereas partial wave leakage at D2 prevents outlet dip observation. The map of |uz| at D1 is shown in Supplementary Fig. 9, with generation of TWGM1 and bulk waves in the Pure PnC. The time-resolved uz map reveals anticlockwise circulation along the cavity path (Supplementary Movie S1).

Figure 3c, d show numerical counterparts to Fig. 3a, b. In Fig. 3c, FFC |uz | (blue curve) exhibits peaks P1-P4 consistent with experimental results (<0.024 MHz frequency shift). Outlet |uz | (red curve) shows dips D1-D4 from TWGM1-TWGM4 generation, visualized via uz distributions in Fig. 3d. Distance D = 3.9–4.5λ (relative to TES wavelengths at frequencies corresponding to TWGM2-TWGM4) confirms a remarkable far-field coupling. The anticlockwise energy flow is revealed in Fig. 3d, matching experimental Supplementary Movie S1. The TWGM1 generation at P1/D1 is perturbed by bulk waves in the Pure PnC, and the experimental perturbation by bulk waves at P1/D1 is verified, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9.

Via dynamical equations (see Methods), Fig. 3c inset displays zoomed-in numerical (dashed) and theoretical (solid) outlet |uz| profiles at D2-D4. Radiative loss γ exceeds dissipative loss Γ (the overcoupled regime) for all TWGMs owing to Dirac-strip enhancement. Material loss (α = 0.0025) moderately affects D3/D4 coupling (Supplementary Fig. 9) but significantly weakens D1/D2, whereas cavity peak frequencies (P1-P4) remain stable. Besides material loss and the influence of bulk waves, the experiment also encounters the effects of backward scattering32 (arising from cavity corners20) and boundary effects at the metamaterial–silicon interface, whereas the input waves are limited in number and pulse power (see Methods). These factors can prevent waves from fully propagating along the ring path as in idealized simulations. While the full demonstration of wave fields relies on simulations, experiments remain essential to reveal the functional capabilities of the waveguide circuits, serving as a foundation for future applications. Far-field phonon coupling enables long-distance cavity energy localization and unlocks functionalities in complex systems, such as dual-cavity configurations.

Another near-field system demonstrates the near-field coupling. A single NFC-waveguide circuit (D = 3×0.866a, Supplementary Fig. 10) produces dip D3 from TWGM3. Experimentally, we position the NFC above the Dirac-strip-bridged waveguide. Despite geometric variations compared to the FFC system, D3/P3 persist in experiment/simulation (Supplementary Fig. 11) regardless of cavity position. TWGM frequencies shift with change in sl and hp, but the robustness of D3 confirms the existence of stable coupling. Crucially, NFC exhibits a 10 kHz frequency shift from D3 (1.955 MHz) to P3 (1.965 MHz) — unobserved in the FFC systems.

Dual-cavity waveguide system

Our final waveguide-cavity phonon system integrates both FFC and NFC, bridged to a shared waveguide via two Dirac strips (Fig. 4a). The cavities are positioned on opposite sides to prevent direct cavity-to-cavity coupling. With parameters matching the single NFC circuit parameters, we measure uz to obtain |uz| at key positions (Fig. 4a). Focusing on TWGM3 which generates transmission dips in individual cavities, the top panel of Fig. 4b shows peak values in |uz| of 0.66 (NFC) and 0.34 (FFC) at 1.956 MHz (the FFC TWGM3 frequency), and corresponding values of 0.53 (NFC) and 0.47 (FFC) at 1.973 MHz (the NFC TWGM3 frequency). This confirms sympathetic resonances33 at each TWGM3 frequency—i.e., both cavities are resonating simultaneously—validated by the |uz| field maps (middle/bottom panels in Fig. 4b). Wave energy is thus exchanged between cavities. The time-resolved uz map (Supplementary Movie S2) reveals clockwise circulation in the upper cavity and anticlockwise circulation in the lower cavity.

a Optical micrograph of the dual-cavity waveguide phonon system with near-field cavity (NFC, D = 3 × 0.866a) and far-field cavity (FFC, D = 7 × 0.866a) coupled to the same waveguide via Dirac strips. The inter-cavity distance L = 7a. b Top: Measured normalized |uz| at the Pure PnC, NFC, FFC, and Outlet positions, excited by a circular pulsed source centered at fc = 1.9 MHz. Bottom: |uz| distributions at 1.956 MHz (PF3) and 1.973 MHz (PN3). (F/N denotes FFC/NFC; i is the peak/dip index.) The thin lines mark waveguide boundaries and cavity paths. c, d Simulated spectra corresponding to (b) obtained with material loss α = 0 (c) and α = 0.0025 (d).

In the top panel of Fig. 4b, the outlet |uz| shows a dip DF3 at 1.956 MHz. Isolated FFC measurements confirm that the DF3 dip originates from the resonance of the TWGM3 in the FFC, whereas resonance hybridization in the dual-cavity system additionally couples DF3 to the TWGM3 in the NFC. This overlap explains why DF3 ≈ 0.29 here—slightly lower than DF3 ≈ 0.32 in the single FFC systems (simulation: 0.22 vs. 0.26). Energy concentrates primarily in the NFC (Fig. 4b bottom panel), which exhibits broad-spectrum |uz| profiles in Supplementary Fig. 12. The computed fields at 1.955 MHz (DF3, top panel in Fig. 4c) reveal a strong FFC uz (bottom panel), differing slightly from Fig. 4b. Introducing material loss α (Fig. 4d top panel), peaks PF3 (1.955 MHz) and PN3 (1.966 MHz) persist (Fig. 4d middle/bottom). Supplementary Figs. 13–14 show displacements versus α, which display peaks in |uz | (PN1-PN4/PF1-PF4) decreasing with α, whereas dips like DF2/DF4 exhibit V-shaped profiles with distinct minima.

Besides material loss, bulk waves are visible beyond the cavities in the wave field of Fig. 4b. As with the FFC circuit, experimental characterization of the full wave field along the ring paths is limited by our ultrasonic pulses of finite duration and power. Simulations capture the ideal wave-field behaviour, whereas experiments remain essential to reveal the main factors influencing wave propagation.

Space-controlled sympathetic resonances

We now modulate inter-cavity coupling by adjusting the horizontal distance L from −7a to 16a, probing how sympathetic resonance affects transmission dips. The simulated normalized |uz| at three positions is displayed in Fig. 5a: waveguide Outlet (left), NFC (middle), and FFC (right), without material loss. Four bright bars labeled PN1-PN4 emerge in the NFC panel, whereas four bars PF1-PF4 appear in the FFC panel. Frequencies for PN1-PN4 and PF1-PF4 match their isolated cavity counterparts.

a Computed normalized |uz| plotted against frequency and inter-cavity distance L at (left) the Outlet, (middle) the upper edge of the NFC, and (right) the bottom edge of the FFC (positions as in Fig. 4a). Positive L indicates NFC is to the left of FFC; negative L < 0 indicates NFC to the right of FFC. b Three plots of normalized |uz| vs. L extracted from DF2 to DF4 in (a), compared with theoretical results calculated from \({D}_{{Fj}}{\prime} \times {P}_{{Fj}}{\prime} /{P}_{{Fj}}{\prime\prime} \left(1+{P}_{{FNj}}{\prime\prime} \right)\).

Energy exchange between cavities is evidenced by weak bright bars in the NFC at the frequencies corresponding to PF1-PF4 (e.g., dashed lines at PF2/PF3) and in the FFC at the frequencies corresponding to PN1-PN4. The outlet panel shows dark bars (DF1-DF4, DN4) corresponding to resonances (PF1-PF4, PN4).

We now analyze the dual-cavity energy exchange mechanism using governing equations of motion. Let \({P}_{{Fj}}{\prime}\) denote FFC peaks and \({D}_{{Fj}}{\prime}\) denote outlet dips for the single cavity circuit and \({P}_{{Fj}}{\prime} {\prime}\) and \({D}_{{Fj}}{\prime} {\prime}\) denote the analogous quantities for the dual-cavity circuit (j = 1,2,3,4). Without material losses, the outlet dips in the dual-cavity circuit are given by \({D}_{{Fj}}{\prime} {\prime}={D}_{{Fj}}{\prime} \times {P}_{{Fj}}{\prime} /{P}_{{Fj}}{\prime} {\prime} \left(1+{P}_{{FNj}}{\prime} {\prime} \right)\) (see theory). According to this formula, theoretically predicted results (square markers) for DF2-DF4 are consistent with direct simulations (solid lines) from the dual-cavity model (Fig. 5b). Relevant results for DF1 appear in Supplementary Fig. 15.

In the expression for \({D}_{{Fj}}{\prime} {\prime}\), the term \({P}_{{FNj}}{\prime} {\prime}\) (\(j=1,2,3,4\)) in the denominator refers to the inter-cavity coupling, and serves to reduce the value of \({D}_{{Fj}}{\prime} .\) This system therefore cannot be expressed in terms of the linear overlap of two individual cavities. When L is close to 0, the value of \({P}_{{Fj}}{\prime} {\prime}\) is markedly reduced, e.g., for PF1-PF3, which leads to a large value of \({D}_{{Fj}}{\prime} {\prime}\) for DF1-DF3, so that critical coupling no longer occurs. Enhanced transmission is not the sole outcome in dual-cavity systems; alternative configurations exist, such as double-sided pillars that broaden plate wave band gaps34. Here, the small value of \({P}_{{Fj}}{\prime} {\prime}\) when L\(\approx 0\) relates to valley PnC properties, such as valley-selected routing paths24.

The discovery of energy exchange between dual cavities is not only crucial for the emergence of non-Hermitian phenomena, but also underpins sympathetic resonance at shared frequencies. Such non-Hermitian behaviour is vital for high-performance sensing and information processing.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have presented an experimental realization of a far-field phonon coupling circuit by means of a Dirac-strip valley metamaterial. The Dirac strip acts as a broadband, direction-selective transport channel whose linear Dirac dispersion suppresses lateral energy spreading and maintains phase coherence over multiple wavelengths. Unlike the background PnCs used here—which support two-dimensional, laterally spreading wave propagation without directional confinement—the Dirac strip provides a quasi-one-dimensional pathway that efficiently channels cavity radiation toward the waveguide and back. This simultaneously achieves robustness, spectral multiplexing, and distance-insensitive waveguide-cavity energy transfer in an on-chip configuration. In addition, by integrating dual cavities in both the near and far fields, we establish deterministic control over non-Hermitian dynamics through material loss and spatial separation, experimentally observing sympathetic resonances.

In the single-cavity waveguide system, adjusting the length of the Dirac strip optimizes the far-field phonon coupling. In the dual-cavity waveguide system, the simultaneous excitation of both cavities produces a pronounced outlet dip compared to the single-cavity system. Furthermore, tuning the inter-cavity distance allows modulation of energy exchange between the dual cavities. The demonstration of far-field coupling over distances up to ~5λ resolves the fundamental challenge of broadband coupling at multiwavelength distances—with direct implications for continuum-mechanical systems requiring spatial decoupling, quantum platforms demanding protected state transfer, photonics, and scalable phononic processors. Furthermore, our platform enables unprecedented pathways for nonlinear wave dynamics33, analogs of quantum many-body phenomena35, and topological wave engineering36,37, directly addressing the escalating need for multi-physical control in integrated wave technologies.

Methods

Experimental methods

The phononic crystal samples were fabricated on 525 μm-thick silicon wafers using lithography and dry etching techniques. During lithography, a 6 μm photoresist layer was applied as an etching mask to protect unpatterned regions, followed by silicon etching in an LPX-ICP system using a BOSCH process to achieve vertical sidewalls. The BOSCH process alternated between passivation and etching steps, with parameters detailed in Supplementary Table 2. Pillar height control was achieved by timing the etching duration based on pre-calibrated silicon etch rates, and final geometries were optically verified.

For all samples (Fig. 1), the wave propagation was characterized using the piezo-laser ultrasonics for in-situ time-resolved measurement of out-of-plane displacement (Supplementary Fig. 1). The displacement uz was monitored across a 41a × 29a rectangular region encompassing cavities and waveguides, with spatial sampling intervals of 641 μm (a) along x and 555 μm (0.866a) along y. Time-resolved data enabled derivation of average amplitude at the Inlet, Outlet, FFC, NFC, and Pure PnC regions (Figs. 3a and 4b, Supplementary Figs. 11a and 12a). In addition, we carried out spatial field mapping of |uz| at the resonant frequencies (Figs. 3b and 4b, Supplementary Figs. 9d, 11b and 12b).

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, the experimental setup comprised a Polytec OFV 2570 laser Doppler vibrometer (LDV), a high-speed camera, a RIGOL DG1032z signal generator, a power amplifier, and a Tektronix DPO4102B-L oscilloscope. Silicon samples were mounted on a supporting plate with a spatial positioning precision of ~5 μm. A 5 mm × 1 mm PZT disk was bonded to the back surface of the waveguide inlet using conductive adhesive. A seven-cycle sinusoidal burst signal centered at frequency fc was generated, amplified, and delivered to the PZT transducer. The number of cycles in the burst was limited to facilitate identification of the incident wave packet as it propagated through the valley metamaterial phononic circuits. The LDV measured the out-of-plane displacement (uz) within target regions, while the high-speed camera recorded the laser beam position and enabled spatial point selection.

To enhance experimental accuracy, several measures were taken. The input signal power was amplified by ~37 dB to generate strong ultrasonic pulses without damaging the silicon wafer. At each spatial point, 512 scans were averaged to reduce white noise. The sampling frequency was set to fs = 100 MHz, more than 47 times the target frequency fc (1.7–2.1 MHz). At each spatial point, signals were recorded with 105 data points, corresponding to >1700 periods of 1/fc. This allowed fine spectral filtering near fc with a frequency resolution of ~0.001 MHz. By repeating these procedures, we obtained the amplitude of the out-of-plane displacement across the target region, enabling separation of neighboring TWGMs and dips. These procedures also allowed us to reconstruct animations and spatial segments of wave displacement within the region of interest.

Numerical calculations

We adopt the finite-element method to calculate dispersion in our silicon phononic crystal plates. Elastic constants are taken as C₁₁ = 165.6 GPa, C₁₂ = 63.9 GPa, C₄₄ = 79.5 GPa, and mass density 2.331 g/cm³38, with silicon assumed to exhibit near-isotropic behaviour. Unit cell dispersion is computed for rotation angles θ = 0° and ±20° (Fig. 1c, d).

For topological edge states (TESs), a sandwiched supercell (Supplementary Fig. 5a) comprising 12-layer PnC-B (top), 12-layer PnC-A (middle), and 12-layer PnC-B (bottom) is constructed. Periodic boundary conditions are applied to the supercell B-A-B along the x-direction, whereas continuity conditions are applied along the y-direction. The results for dispersion (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c) include the displacement ratio \(\int |{u}_{z}{|dV}/\int |{u}_{t}{|dV}\) at each frequency, where uz and ut denote out-of-plane and total displacements.

Topological whispering gallery modes (TWGMs) are analyzed using a rhombus cavity supercell (side length 7a) positioned between the inner PnC-B and outer PnC-A (Supplementary Fig. 6a). Periodic boundary conditions are applied to three pairs of parallel sides of the hexagonal supercell, yielding the corresponding eigenfrequencies and displacement fields (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. 6b, c).

Wave propagation simulations for NFC-waveguide, FFC-waveguide (Fig. 2a), and dual-cavity structures (Fig. 4a) replicate experimental dimensions (Fig. 1a). Perfectly matched layers (PMLs) absorb boundary reflections. A circular source applies unit z-axis force over a 2.5 mm radius at the waveguide inlet. Transmission spectra (Figs. 3c and 4c, d, Supplementary Figs. 9a, 11c, 12c and 13) are based on the average |uz| over 5a segments at Inlet, Outlet, FFC, NFC, and unpatterned PnC regions.

In single cavity-waveguide models (Fig. 2a), the Dirac strip length D varies from 1 to 12 layers in 1-layer increments. Frequency- and distance-resolved |uz| maps (Fig. 2c) are generated from average values over 5a segments at the Outlet and FFC. Control simulations replacing Dirac strips with PnC-A appear in Fig. 2d. For dual-cavity models (Fig. 4a), the inter-cavity distance L sweeps from −7a to 16a in steps of a, producing frequency-distance |uz| maps at the Outlet, NFC, and FFC (Fig. 5a).

Theory of the waveguide-cavity dynamics

Single-cavity waveguide system

The waveguide-cavity coupling can be understood from the theoretical model shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. The cavity lies either above or below the waveguide. From theory39,40, the incident wave S+ gives rise to a cavity response \({\tilde{a}}_{c}={a}_{c}{e}^{i\omega t}\). Γ and γ are the dissipative and radiative losses of the cavity, respectively.

The governing equation can be expressed as40,41,42

where ω0 = 2πf0 represents the resonant frequency of the cavity. Silicon can be considered to be close to an isotropic material, so, in contrast to previous work20, material anisotropy is ignored in this equation.

The derivative of \({\tilde{a}}_{c}={a}_{c}{e}^{i\omega t}\) is given by

When the amplitude remains constant, dac/dt = 0, yielding

Substituting Eq. (3) into Eq. (1) yields

The relationship between the input wave and the output wave S- can be written as

Combining Eqs. (4) and (5), the transmission coefficient of the system can be expressed in the form

According to Eq. (6), one obtains

where Tmin is the minimum value around ω0, and Δω represents the angular frequency corresponding to the full width at half of Tmin. These two parameters can be obtained from the numerically calculated spectrum. The substitution of Tmin and Δω into Eq. (7) yields the dissipative loss Γ and radiation loss γ. Then, by use of Eq. (6), one can plot the fitted transmission profile around ω0. Critical coupling occurs when Γ = γ, whereas Γ < γ (or Γ > γ) indicates over- (or under-) coupling.

Dual-cavity waveguide system

The theoretical model of the dual-cavity waveguide system is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3. Each cavity includes dissipative loss Γj and radiative loss γj (j = F, N). Since the two cavities are inserted on separate sides of the waveguide, direct cavity-to-cavity coupling is prohibited. The quantity φ is the accumulated phase difference along the waveguide path.

For an incident wave S+, the governing equation for the two-cavity system (\({\tilde{a}}_{N}={a}_{N}{e}^{i\omega t}\) and \({\tilde{a}}_{F}={a}_{F}{e}^{i\omega t}\)) can be written as43,44

where ωN and ωF are the resonance frequencies of the near- and far-field cavities, respectively. Direct cavity-to-cavity coupling is ignored. On the right-hand side of Eq. (8), the 2nd term includes two contributions: one from the coupling between the upper cavity (aN) and the incoming waves, the other from the radiated field from the lower cavity (aF). Equation (9) can be understood in a similar way.

The transmission coefficient for the system is given by

By fitting the simulated transmission profile, we can obtain parameters including Γj and γj (j = F, N). Substituting them into Eqs. (8) and (9) yields \({\tilde{a}}_{N}\) and \({\tilde{a}}_{F}\). One can then plot the theoretically fitted profile of transmission from Eq. (10).

When ω = ωF,

Specifically,

where the DFj” is the outlet dip in the dual-cavity circuit.

Combining Eqs. (8) and (9), the amplitudes for the NFC and FFC are given by

where PFj” refers to the amplitude peak for the FFC (ω = ωF) in the dual-cavity circuit.

As a comparison, consider again the single FFC-waveguide model and set ω = ω0 = ωF. According to Eqs. (4) and (6), the outlet dip DFj’ and the FFC peak PFj’ can be derived as follows:

Combining Eqs. (12), (14), (15) and (16),

If the two cavities possess different resonance frequencies (ωN ≠ ωF), then when ω = ωF,

and the term \(i(\omega -{\omega }_{N})+{\Gamma }_{N}+{\gamma }_{N}\) can be seen to contain extra terms compared to \({\Gamma }_{F}+{\gamma }_{F}\):

One can rewrite Eq. (17) as

and similarly for Eq. (20):

where

Finally, the outlet dip in the dual-cavity circuit can be expressed as

Based on Eq. (12), the outlet dip is governed by Γj and γj (j = F, N). Equation (23) shows that the inter-cavity coupling affects the outlet dip DFj”, which can be seen in the term (1 + PFNj”).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Rayleigh, L. The problem of the whispering gallery. Philos. Mag. 20, 1001–1004 (1910).

Xu, X. et al. Acoustofluidic tweezers via ring resonance. Sci. Adv. 10, eads2654 (2024).

Mezil, S. et al. Active chiral control of GHz acoustic whispering-gallery modes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 144103 (2017).

Armani, D. K., Kippenberg, T. J., Spillane, S. M. & Vahala, K. J. Ultra-high-Q toroid microcavity on a chip. Nature 421, 922–925 (2003).

Henke, J. et al. Integrated photonics enables continuous-beam electron phase modulation. Nature 600, 653–658 (2021).

Bahari, B. et al. Nonreciprocal lasing in topological cavities of arbitrary geometries. Science 358, 636–640 (2017).

Wang, Y., Zeng, S., Humbert, G. & Ho, H. P. Microfluidic whispering gallery mode optical sensors for biological applications. Laser Photonics Rev. 14, 2000135 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. High-efficiency and broadband on-chip electro-optic frequency comb generators. Nat. Photonics 16, 679–685 (2022).

Chen, W., Kaya, O. S., Zhao, G., Wiersig, J. & Yang, L. Exceptional points enhance sensing in an optical microcavity. Nature 548, 192–196 (2017).

Miri, M. & Alù, A. Exceptional points in optics and photonics. Science 363, eaar7709 (2019).

Peng, B. et al. Loss-induced suppression and revival of lasing. Science 346, 328–332 (2014).

Li, A. et al. Exceptional points and non-Hermitian photonics at the nanoscale. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 706–720 (2023).

Patil, Y. S. S. et al. Measuring the knot of non-Hermitian degeneracies and non-commuting braids. Nature 607, 271–275 (2022).

Parto, M., Leefmans, C., Williams, J., Nori, F. & Marandi, A. Non-Abelian effects in dissipative photonic topological lattices. Nat. Commun. 14, 1440 (2023).

Bergholtz, E. J., Budich, J. C. & Kunst, F. K. Exceptional topology of non-Hermitian systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 01505 (2021).

El-Ganainy, R. et al. Non-Hermitian physics and PT symmetry. Nat. Phys. 14, 11–19 (2018).

Parappurath, N., Alpeggiani, F., Kuipers, L. & Verhagen, E. Direct observation of topological edge states in silicon photonic crystals: spin, dispersion, and chiral routing. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaw4137 (2020).

Barik, S., Karasahin, A., Flower, C. & Cai, T. A topological quantum optics interface. Science 359, 666–668 (2018).

Yu, S. et al. Critical couplings in topological-insulator waveguide-resonator systems observed in elastic waves. Natl Sci. Rev. 8, nwaa262 (2021).

Hatanaka, D. et al. Valley pseudospin polarized evanescent coupling between microwave ring resonator and waveguide in phononic topological insulators. Nano Lett. 24, 5570–5577 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. Parity-frequency-space elastic spin control of wave routing in topological phononic circuits. Adv. Sci. 11, 2404839 (2024).

Li, J., Deng, C., Zhang, K., Lu, Q. & Yang, H. Higher-order topological states in dual-band valley sonic crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 123, 253101 (2023).

Wu, X. et al. Topological corner modes induced by Dirac vortices in arbitrary geometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 226802 (2021).

Yan, M. et al. On-chip valley topological materials for elastic wave manipulation. Nat. Mater. 17, 993–998 (2018).

Zhang, Q. et al. Gigahertz topological valley Hall effect in nanoelectromechanical phononic crystals. Nat. Electron. 5, 157–163 (2022).

Hu, B. et al. Non-Hermitian topological whispering gallery. Nature 597, 655–659 (2021).

Zeng, Y. et al. Electrically pumped topological laser with valley edge modes. Nature 578, 246–250 (2020).

Jia, R. et al. On-chip active supercoupled topological cavity. Adv. Mater. 37, 2419261 (2025).

Zhao, J. et al. Elastic valley spin controlled chiral coupling in topological valley phononic crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 275501 (2022).

Wang, M. et al. Valley-locked waveguide transport in acoustic heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 11, 3000 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Lu, M. & Chen, Y. Observation of free-boundary-induced chiral anomaly bulk states in elastic twisted kagome metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 086302 (2024).

Rosiek, C. A. et al. Observation of strong backscattering in valley-Hall photonic topological interface modes. Nat. Photonics 17, 386–392 (2023).

Shim, S., Imboden, M. & Mohanty, P. Synchronized oscillation in coupled nanomechanical oscillators. Science 316, 95–99 (2007).

Badreddine, A. M. & Oudich, M. Enlargement of a locally resonant sonic band gap by using double-sides stubbed phononic plates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 123506 (2012).

Liška, V. et al. PT-like phase transition and limit cycle oscillations in non-reciprocally coupled optomechanical oscillators levitated in vacuum. Nat. Phys. 20, 1622–1628 (2024).

Lu, X., McClung, A. & Srinivasan, K. High-Q slow light and its localization in a photonic crystal microring. Nat. Photonics 16, 66–71 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Tunable topological charge vortex microlaser. Science 368, 760–763 (2020).

Zhao, J., Bonello, B. & Boyko, O. Focusing of the lowest-order antisymmetric Lamb mode behind a gradient-index acoustic metalens with local resonators. Phys. Rev. B 93, 174306 (2016).

Righini, G. C. et al. Whispering gallery mode microresonators: Fundamentals and applications. La Riv. del. Nuovo Cim. 34, 435–488 (2011).

Yariv, A. Critical coupling and its control in optical waveguide-ring resonator systems. IEEE Photonics Tech. Lett. 14, 483–485 (2002).

Yariv, A. Universal relations for coupling of optical powerbetweenmicroresonators and dielectric waveguides. Electron. Lett. 36, 321–322 (2000).

Haus, H. A. Waves and Fields in Optoelectronics Vol. 464 (Prentice Hall, 1984).

Tan, W., Sun, Y., Wang, Z. & Chen, H. Manipulating electromagnetic responses of metal wires at the deep subwavelength scale via both near- and far-field couplings. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 091107 (2014).

Kekatpure, R. D., Barnard, E. S., Cai, W. & Brongersma, M. L. Phase-coupled plasmon-induced transparency. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 243902 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 12172256, 12302115, 12272269, 11972257, 52027816). It was also supported by Shanghai Leading Talent Program of Eastern Talent Plan. J. Z. would like to acknowledge Dr. Haoyun Tu’s help with the experiment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yao H., Weitao Y. and Jinfeng Z. designed the sample structures. Qi W. and Jia Z. fabricated the experimental samples. Yao H. performed the experimental measurements, carried out the numerical simulations, analyzed and visualized all data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Weitao Y. and Jinfeng Z. helped check the simulation results. Weitao Y., Yao H., Zhiwei G. and Jinfeng Z. derived the theory. Jinfeng Z. conceived the idea, designed the experimental setups and analyzed the initial experimental data. Yuxuan Z. and Yongdong P. assisted in the experiments. Yueting Z., Zheng Z. and Oliver B. Wright helped in the derivation of the theory. Jinfeng. Z., Weitao Y., Yueting Z., Yongdong P. and Zhiwei G. conceived the project. Oliver B. Wright constructed the final version of the manuscript. All the authors contributed to discussions, interpretation of the data, and the writing process.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Y., Yuan, W., Guo, Z. et al. Far-field phonon coupling in valley metamaterial circuits. Nat Commun 17, 422 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67108-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67108-6