Abstract

Quantum simulation enables studies of open-system dynamics in non-perturbative regimes by programming electronic, vibrational, and environmental interactions on comparable energy scales. Trapped ions offer this capability, combining spins, phonons, and tunable dissipation on one platform. We demonstrate an open-system quantum simulation of charge and exciton transfer in a multi-mode linear vibronic coupling model. Using tailored spin-phonon interactions with reservoir engineering, we emulate a system with two dissipative vibrational modes coupled to donor and acceptor sites and track its non-equilibrium dynamics. We continuously tune the system from the charge transfer regime to the vibrationally assisted exciton transfer regime and find that degenerate modes enhance transfer rates at large energy gaps, while non-degenerate modes activate pathways that reduce the energy-gap dependence. Thus, the presence of one additional vibration introduces interfering pathways and reshapes non-perturbative excitation transfer. Our results establish a scalable, hardware-efficient route to simulate vibronic processes with engineered environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Molecular vibrations drive a wide range of phenomena in charge and energy transfer in complex chemical and biological systems. Understanding these processes requires modeling the interactions among the electronic, spin, and vibrational degrees of freedom, which cannot be treated independently, especially when the Born-Oppenheimer (BO) approximation breaks down. Although the BO approximation is the cornerstone of structural chemistry, it fails in cases where nuclear and electronic motions become strongly coupled, as occurs in nitrogen fixation and photosynthesis. The fully simultaneous quantum treatment of electrons and vibrations is still a daunting task for existing numerical methods1,2,3,4,5.

Quantum rate phenomena generally require a model that accounts for both fast, intramolecular vibrational modes and slower, environment-mediated modes. Linear vibronic coupling models (LVCMs) offer the simplest framework for describing such systems by assuming that electronic states couple to multiple vibrational modes only in a linear fashion6,7,8. LVCMs have been widely used to model many complex processes, including singlet fission, triplet–triplet annihilation, and charge transfer in organic photovoltaics9,10,11.

The high degree of control and tunability of programmable quantum platforms, such as trapped ions8, superconducting qubits12, and photonic devices13, potentially provides an alternative approach to large-scale classical computations for studying condensed-phase chemical dynamics through direct quantum simulation. In particular, trapped-ion analog and analog-digital simulators have already realized a variety of chemical dynamics with fully programmable system parameters and accurate time-resolved features14,15,16,17,18. With engineered reservoirs on their native spin and bosonic degrees of freedom, trapped-ion systems have also been recently used to study non-equilibrium quantum reaction dynamics19,20,21,22,23.

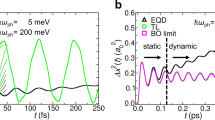

In this work, we present the first trapped-ion simulation in which unitary spin-phonon couplings and mode-selective dissipation via cooling are independently programmed, enabling real-time open-system emulation of excitation transfer dynamics in a two-mode LVCM. Emulating spin-phonon systems with multiple bosonic modes, combined with environment engineering, represents an important step toward realizing models of molecular systems in which multiple intramolecular (fast) modes coexist with long-wavelength, low-frequency environment-mediated modes; both of which play crucial roles in excitation-energy transfer24,25. Here, by using both ground-state and optical qubits, we achieve simultaneous control over mode frequencies, vibronic couplings, and dissipation rates. We characterize the low-temperature transfer rate across a wide parameter range, highlighting the roles of mode degeneracy and vibronic coupling strength. We focus on two transfer regimes (see Fig. 1a): charge transfer (CT) and vibrationally assisted exciton transfer (VAET), which correspond to strong and weak vibronic coupling, respectively. The distinction is made based on the differing phenomenological effects of the vibronic coupling on typical excitation and charge transfer processes6,26. When the vibrational modes are strongly coupled to the electronic states of the system, they reshape the potential energy landscape and actively influence the charge transfer reaction27. By contrast, weak couplings between the vibrational and electronic degrees of freedom primarily allow phonons to assist coherence between the electronic eigenstates28. We note that charge transfer can also occur in the weak vibronic coupling regime29. However, in this study, we use this term to refer specifically to the strong vibronic coupling regime, with which it is more commonly associated.

a Schematic diagram illustrating two regimes of transfer dynamics, defined by vibronic coupling strengths. In the VAET regime, the harmonic oscillators are weakly coupled to the donor-acceptor electronic system, whereas the strong vibronic couplings in the CT regime introduce significant displacements, resulting in distinct two-dimensional potential energy surfaces for the donor (red) and acceptor (blue) states. The electronic coupling opens a 2V avoided crossing between these surfaces. For clarity, we show only the y2 = 0 cut across the two-dimensional potential energy surfaces, with the vibrational levels associated with the fast (ω1) and slow (ω2) modes, represented by their wavefunctions and horizontal lines, respectively. In both regimes, the vibrational modes undergo dissipation, represented by the wiggly arrows. b Top (dashed panel): Illustration of a first-order VAET process at zero temperature, where weak vibronic coupling coherently drives transitions between the eigenstates of the electronically coupled system via a single-excitation exchange with a vibrational mode (see Section IIIB of the Supplementary Information). Specifically, when energy is released from the higher-energy eigenstate, the vibrational mode gains a phonon excitation, which subsequently dissipates into the environment. Bottom (dashed panel): Constructively interfering transfer pathways underlying the second-order VAET process, which bridges the energy gap of \(\sqrt{\Delta {E}^{2}+{(2V)}^{2}}={\omega }_{1}+{\omega }_{2}\). Each dashed line denotes two virtual states: one with \(| {e}_{+}\left.\right\rangle\) and one with \(| {e}_{-}\left.\right\rangle\). c Top: Two-dimensional energy landscape in the CT regime, with coordinates defined by the two vibrational modes. The orange and purple surfaces correspond to the system’s upper and lower adiabatic surfaces under strong electronic coupling, respectively. Bottom: Contour plot of the lower adiabatic surface, with the green arrow indicating the direction of charge transfer along the effective reaction coordinate.

Results

The minimal multi-mode LVCM considers two vibrational modes and is described by the following Hamiltonian (ℏ = 1)30:

where σx,z are the Pauli operators acting on the donor and acceptor electronic sites, \(| D\left.\right\rangle \equiv {| \uparrow \left.\right\rangle }_{z}\) and \(| A\left.\right\rangle \equiv {| \downarrow \left.\right\rangle }_{z}\), with an energy difference ΔE and an electronic coupling strength V. For ΔE > 0, the Hamiltonian describes an exothermic reaction when the excitation is transferred from the donor site to the acceptor site. Each harmonic oscillator i with a vibrational energy ωi is associated with creation (\({a}_{i}^{{{\dagger}} }\)) and annihilation (ai) operators, and it is linearly coupled to the electronic sites at a rate gi.

In this model, the CT regime is realized when the vibronic coupling is comparable to or larger than the harmonic frequency (gi ≳ ωi, also known as strong coupling in quantum optics), which is characteristic of many situations involving charge motion in chemical and biological reactions, ranging from redox catalysis to solvent-induced electronic delocalization27,31,32,33. The donor and acceptor electronic sites in this regime are described by uncoupled two-dimensional potential energy surfaces with respect to the (y1, y2) spatial coordinates, where \({y}_{i}={y}_{i0}({a}_{i}+{a}_{i}^{{{\dagger}} })/2\) with \({y}_{i0}=\sqrt{1/2m{\omega }_{i}}\) and m being the particle mass. The electronic coupling V mixes the two potential energy surfaces by opening an avoided crossing with a gap of 2V at their intersection. A strong vibronic coupling (gi ≳ ωi) distorts the energy landscape by inducing a displacement of gi/ωi between the donor and acceptor potential energy surfaces along yi, providing the electronic coupling with a dependence on the overlaps of the displaced oscillator states20,27,34. During CT, the donor population undergoes crossing of the energy barrier along an effective reaction coordinate, roughly defined by the axis y1 + y2 in the degenerate case. The total reorganization energy of the system is defined as \(\lambda={\sum }_{i}{\lambda }_{i}\equiv {\sum }_{i}{g}_{i}^{2}/{\omega }_{i}\), which is the energy required to displace the wave packet on an uncoupled potential energy surface by the distances of ∣g1/ω1∣ and ∣g2/ω2∣ along the y1 and y2 axes, respectively. When the electronic coupling is small (V ≈ 0), the reorganization energy λ and energy difference between the two surfaces ΔE determine the classical activation energy, defined by U = (ΔE+λ)2/4λ20,27.

Within the CT regime, there exist two electronic coupling regimes: the strictly nonadiabatic (or perturbative) regime with ∣V∣ < λi/4 and the strongly adiabatic (or non-perturbative) regime with ∣V∣ ~ λi/420,27,35. In the former, Fermi’s golden rule, where we treat the electronic coupling as a perturbation to the uncoupled donor-acceptor system, predicts that transfer dynamics occur when the quantized vibronic energy levels of the donor and acceptor surfaces match, resulting in transfer rate resonances at:

with ℓ1 and ℓ2 being integers (see Section IIIA of the Supplementary Information). On the other hand, at larger electronic coupling (∣V∣ ~ λi/4), the avoided crossing becomes appreciable, leading to the hybridization of the two-dimensional donor and acceptor potential energy surfaces into upper and lower adiabatic energy surfaces (see Fig. 1c). This results in delocalized eigenstates that are superpositions of donor and acceptor vibronic states20,27. In this regime, Fermi’s golden rule no longer applies, which provides strong motivation to study these transfer conditions experimentally.

Conversely, weak vibronic coupling (gi ≪ ωi) is more characteristic of VAET, as occurs between pigments in light-harvesting compounds and their reaction centers14. In this regime, excitation transfer between donor and acceptor sites with an energy separation ΔE is enabled by the electronic coupling term Vσx, resulting in two eigenenergies of the total electronic system that differ by \(\sqrt{\Delta {E}^{2}+{(2V)}^{2}}\). Unlike in the CT regime, where strong vibronic couplings displace the donor and acceptor energy surfaces and thereby define the vibronic states that participate in excitation transfer, the couplings between the electronic system and the vibrational modes in the VAET regime are weak. From Fermi’s golden rule, these weak couplings perturbatively facilitate quantized energy exchange between the oscillators and the electronically coupled excitation sites themselves, leading to transfer resonances at:

with ℓ1 and ℓ2 being integers. At resonance, the combined vibrational energy ℓ1ω1 + ℓ2ω2 provided by the two modes exactly bridges the electronic energy gap, thereby assisting the transfer14,21,28 (see Section IIIB of the Supplementary Information).

In most realistic chemical situations, the interaction between the donor-acceptor vibronic system and the external environment causes the vibrational modes to undergo incoherent dissipation. Thus, the full Hamiltonian, Htotal = H + Hb + Hsb, also includes the bath degrees of freedom Hb, described by a large collection of continuous harmonic oscillators, as well as a linear coupling between the bath and the system’s vibrational modes, given by Hsb. The correlations of the environment and their influence on the system can be characterized by a continuous spectral density function J(ω). It is worth noting that the system contains both the electronic sites and the vibrational modes in Eq. (1). On the other hand, J(ω) does not represent the vibrational modes themselves, but rather the environment that causes them to dissipate. Under the assumptions of an Ohmic environment27,36 and vibrational dissipation rates that are weaker than the vibrational and thermal energies (γi ≪ ωi, γi ≪ kBTi)37, the dissipative dynamics of the system can be effectively described by a Lindblad master equation:

where \({{{{\mathcal{L}}}}}_{c}[\rho ]=c\rho {c}^{{{\dagger}} }-\frac{1}{2}\{{c}^{{{\dagger}} }c,\rho \}\), and \({\bar{n}}_{i}\) is the average thermal phonon number that describes the temperature of the environment for each vibrational mode ωi with \({k}_{B}{T}_{i}\approx {\omega }_{i}/\log (1+1/{\bar{n}}_{i})\). The vibrational excitations continuously evolve to equilibrate with the bath at a rate γi, leading to an irreversible population transfer from the donor site to the acceptor site20,27.

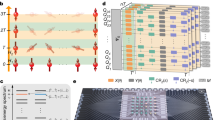

To experimentally realize the multi-mode LVCM, we use a dual-species chain of one 171Yb+ ion and one 172Yb+ ion trapped in a linear Paul trap20. We encode the electronic degrees of freedom in the two hyperfine clock states of the 171Yb+ ground-state qubit, \({| }^{2}{S}_{1/2},F=1,{m}_{F}=0\left.\right\rangle \equiv {| \uparrow \left.\right\rangle }_{z}\) and \({| }^{2}{S}_{1/2},F=0,{m}_{F}=0\left.\right\rangle \equiv {| \downarrow \left.\right\rangle }_{z}\) with the frequency splitting of ωhf = 2π × 12.642 GHz (see Fig. 2a). In this work, we use the two radial out-of-phase modes (also referred to as tilt modes), each along an orthogonal radial principal trap axis, to represent ω1 and ω2 (see “Methods”).

a Experimental setup for studying open-system LVCM dynamics with two vibrational modes using a 171Yb+ -172Yb+ ion chain, whose motional degrees of freedom are shared (represented by the connecting spring). Insets: simplified level schemes for 171Yb+ and 172Yb+ qubits. Stimulated Raman transitions on the 171Yb+ ground-state qubit with 355 nm beams (purple) are used to engineer the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1). The optical qubit of 172Yb+ is addressed with a 435.5 nm beam (light blue) and a 935 nm repumper beam (red line in the 172Yb+ inset) for sympathetic cooling. b Experimental sequence used to measure the time-resolved evolution of the excitation at the donor electronic site (see “Methods” for details).

Our experiment is performed in a driven rotating frame, where we use two π/2 pulses to map the z spin basis in Eq. (1) onto the y basis. This method allows us to use the ion-light interactions between the 171Yb+ qubit and the 355 nm Raman laser tones to independently engineer individual terms of the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) with precise control. Two laser tones resonant with the qubit frequency generate the single-qubit operations (Vσx and (ΔE/2) σz terms), while two other laser tone pairs at frequencies ±μi = ±(ωtilt,i + δi) from the qubit resonance realize the vibronic coupling and harmonic terms in Eq. (1). Here, δi is the detuning from its respective radial tilt mode at frequency ωtilt,i, which determines the vibrational energy ωi through δi ≡ −ωi20,38.

The engineered dissipation of the vibrational modes is realized by driving the narrow transitions from the ground-state manifold \(| g\left.\right\rangle \equiv {| }^{2}{S}_{1/2}\left.\right\rangle\) to the optical metastable-state manifold \(| o\left.\right\rangle \equiv {| }^{2}{D}_{3/2}\left.\right\rangle\) of the 172Yb+ ion, detuned by−ωtilt,i from resonance, using a total of four laser tones to address all the involved Zeeman sub-levels. Together with a 935 nm repumper beam to optically reset the electronic excitation to the ground states, this results in sympathetic cooling on both radial tilt modes of the chain with independently tunable dissipation rates. This is equivalent to generating a structured bath of continuous harmonic oscillators with two Lorentzian spectral densities centered at ω1 and ω2, with full widths at half maximum γ1 and γ2, respectively21,37 (see Section IV of the Supplementary Information). In this setup, all the system parameters, including the bath properties, are determined by the frequency and power of the laser tones used to generate the corresponding ion-light interactions. Therefore, they can be precisely tuned and independently calibrated20, with the magnitudes of the system parameters used in our study being much larger than the decoherence rates caused by experimental imperfections (see Section II of the Supplementary Information). The experimental sequence is discussed in “Methods” and summarized in Fig. 2b.

In this work, we focus on the non-perturbative quantum regime27, where the electronic coupling strength is strong (∣V∣ ~ λi/4), and the bath temperatures are low (\({\bar{n}}_{i} \sim 0.1\)–0.2, see “Methods”). We compare the excitation transfer behaviors of the two-mode systems with those of their single-mode counterparts, which have been experimentally realized on trapped-ion simulators in refs. 14,20,21 to various extents. In the following, we characterize the transfer dynamics by measuring the inverse lifetime of the donor population, PD = (〈σz〉 + 1)/2, which is described by refs. 20,27,34,35:

This choice accounts for both the rate of dynamical equilibration and the steady-state population, which is analogous to the transfer efficiency, crucial for studying energy conversion in chemical processes.

Charge transfer (CT)

We first study non-perturbative CT with gi ~ ωi in two different cases: degenerate (ω1 = ω2 ≡ ω) and non-degenerate (ω1 > ω2), where the Fermi’s golden rule analysis breaks down. In the degenerate case, we observe in Fig. 3a that, in the two-mode model, the exothermic region characterized by monotonically increasing transfer rates with respect to the energy offset ΔE, caused by both the broadening effect of strong electronic coupling to off-resonant states and by the dissipation rates that limit the transfer rates (∣V∣ > γi)20,27, extends to a higher energy gap, ΔE ≈ 4ω, compared to its single-mode counterpart (ΔE ≈ 3ω). This extension can be attributed to the larger number of state configurations available when two vibrational modes (two dimensions) are present, rather than just one (one dimension). We note that it is not possible to adjust the Hamiltonian parameters of a single-mode model to reproduce this observation.

a Transfer rate spectrum of degenerate CT (ω1 = ω2 ≡ ω) with (V, g1, γ1, g2, γ2) = (0.200, 1.200, 0.036, 1.100, 0.040)ω. Red circles represent experimental data with error bars estimated via bootstrapping (see “Methods”). The solid red curve shows the transfer rate calculated from Eq. (4), using the definition in Eq. (5) and including spin decoherence (γz = 0.001ω) and motional dephasing of both modes (γim = 0.016ω, with i = 1, 2). The blue curve shows the numerical result for the single-mode CT case, where ω2 = g2 = γ2 = γ2m = 0. b, c Experimental and numerical donor population evolution PD(t) versus energy gap ΔE and the number of vibrational oscillations ωt/2π, using the same parameters as in the red circles and solid red curve in (a), respectively. Here, the detunings from the two tilt modes for encoding the degenerate vibrational energies are both set to δ1 = δ2 = −2π × 5 kHz. d, e, f Same layout as in (a), (b), and (c) for the non-degenerate CT case (ω1 > ω2) with (V, g1, γ1, ω2, γz, γim) = (0.138, 1.029, 0.023, 0.375, 0.001, 0.010)ω1 and (g2, γ2) = (0.993, 0.027)ω2, respectively. The characteristic timescale is defined by the fast vibrational frequency ω1. In this case, the detuning from the inner (outer) tilt mode, which encodes the fast (slow) vibrational energy, is set to δ1 = −2π × 8 kHz (δ2 = −2π × 3 kHz).

Moreover, we remark that resonant peaks at ΔE ≈ ℓω, with ℓ being an integer, appear when the energy difference is sufficiently high (ΔE ≳ 5ω). Under this energy gap condition, the initially localized donor state has significant overlaps with the eigenstates of the upper hybridized surface, leading to population trapping, as explained in refs. 20,27. At these resonant peaks, the trapped population is released from the upper hybridized surface to the lower hybridized surface during the evolution. Owing to the large energy offset and the increased number of state configurations in the two-mode degenerate case (relative to the single-mode case), the steady states of these resonant transfers exhibit greater overlaps with the acceptor states, as shown in Fig. 3b, c, where the final donor populations, \({P}_{D}({t}_{{{{\rm{sim}}}}})\), are closer to zero than the steady-state populations of the single-mode counterpart (see Supplementary Fig. 7b). This results in enhanced transfer rates at large energy gaps ΔE ≳ 5ω, compared to the single-mode case.

Conversely, when ω1 > ω2, the donor-acceptor energy landscape supports highly delocalized states along y2, as the system lies deeply in the adiabatic regime (∣V∣ > λ2/4)20,27. This introduces multiple states delocalized along the y2 direction, in addition to the existing delocalization along y1 provided by the fast vibrational mode levels. Together, these enable additional transfer channels among the highly delocalized two-dimensional vibronic states across the donor-acceptor energy gap. Thus, the transfer process in the non-degenerate case is less sensitive to the donor-acceptor energy offset, making it more robust to variations in this parameter. Due to our experimental resolution (see Section II of the Supplementary Information), we cannot resolve the resonances associated with these transfer channels and instead observe a smooth transfer rate curve in Fig. 3d. In addition, unlike the degenerate case, the transfer rates at the resonances with large ΔE are not evidently enhanced relative to those of the single-mode system. We emphasize that the non-degenerate two-mode spectrum observed in Fig. 3d cannot be obtained by tuning the parameters of a single-mode model.

Transitioning to VAET

To verify that the additional transfer pathways, provided by the slow vibrational mode, are responsible for the smooth transfer profile shown in Fig. 3d for the non-degenerate CT case, we decrease the electronic coupling strength and the vibronic coupling strength to the slow vibrational mode in Fig. 4a-c (see Section VII of the Supplementary Information for more details on VAET-CT crossover). Choosing a weaker electronic coupling (∣V∣ < λ1/4) while maintaining strong vibronic coupling to the fast mode (g1 > ω1) places the system closer to the nonadiabatic CT regime along the fast mode direction. In this case, the donor and acceptor populations remain localized on their respective potential energy surfaces along y1, and resonant excitation transfers occur between well-defined donor and acceptor vibronic states at ΔE ≈ ℓ1ω1, with ℓ1 being an integer20,27 (the one-dimensional case of Eq. (2)). In the single-mode scenario, where only y1 is considered, this results in the manifestation of the vibrational mode structure in the transfer rate spectrum (solid blue curve in Fig. 4a). Therefore, choosing a weaker electronic coupling allows us to distinguish the influences of the two vibrational degrees of freedom on the transfer dynamics when the second vibrational mode is involved. At the same time, lesser vibronic coupling to the slow mode reduces the distortion of the potential energy surfaces along y2, making the transfer processes involving the slow mode to enter the VAET regime and introducing additional transfer rate resonances energetically enabled by the slow mode.

a Transfer rate spectrum for (V, g1, γ1, ω2) = (0.063, 1.288, 0.015, 0.375)ω1 and (g2, γ2) = (0.607, 0.067)ω2. Red circles represent experimental data with error bars estimated via bootstrapping (see “Methods”). The solid red curve shows the transfer rate calculated from Eq. (4), using the definition in Eq. (5) and including spin decoherence (γz = 0.001ω1) and motional dephasing of both modes (γim = 0.010ω1, with i = 1, 2). The blue curve shows the numerical result for the single-mode case, where ω2 = g2 = γ2 = γ2m = 0. Downward green arrows indicate nonadiabatic CT along y1, assisted by single-phonon exchange with the slow mode via VAET. b, c Experimental and numerical donor population evolution PD(t) versus energy gap ΔE and the number of vibrational oscillations of the fast mode ω1t/2π, using the same parameters as in the red circles and solid red curve in (a), respectively. Here, the detuning from the inner (outer) tilt mode, which encodes the fast (slow) vibrational energy, is set to δ1 = −2π × 8 kHz (δ2 = −2π × 3 kHz).

As shown by the resolved resonances in Fig. 4a, the additional peaks around the nonadiabatic transfer resonances of the fast mode, which coincide with the single-mode spectrum (solid blue curve), are induced by the second mode and located at \(\Delta E\approx \sqrt{{({\ell }_{1}{\omega }_{1}+{\ell }_{2}{\omega }_{2})}^{2}-{(2V)}^{2}}\approx {\ell }_{1}{\omega }_{1}+{\ell }_{2}{\omega }_{2}\), where the ℓ2ω2 contribution comes from the VAET process bridging the energy gap between vibronic states defined by the fast mode (see the discussion of the VAET regime below). The processes associated with ℓ2 = 1 dominate and are more clearly observable because of the perturbative nature of VAET. With either a larger electronic coupling strength V or a stronger vibronic coupling strength to the slow mode g2, the additional resonances caused by the presence of the slow mode broaden and merge with the fast-mode transfer resonances into a smooth spectrum, as shown, for example, in Fig. 3d. This highlights the crucial role of the simultaneous presence of fast and slow vibrational modes in reducing the CT dependence on the donor-acceptor energy gap through the additional transfer pathways.

Vibrationally Assisted Exciton Transfer (VAET)

Unlike in the CT regime, where strong vibronic coupling distorts the donor-acceptor potential energy landscape that defines the vibronic eigenstates of the system, in the VAET regime (gi ≪ ωi), the vibrational modes are weakly coupled to the electronic degree of freedom and therefore only act as facilitators of the exothermic transfer, where units of vibrational energy are exchanged with the electronic sites during the excitation transfer at specific ΔE resonances, given by Eq. (3) (see Fig. 5)28. Here, we also consider systems in the non-perturbative regime, characterized by strong electronic coupling (∣V∣ ~ λi/4). For the vibrationally degenerate case (ω1 = ω2 ≡ ω), shown in Fig. 5a, the transfer rate of the first resonance in the two-mode model is not enhanced compared to the single-mode case because only a single phonon from either degenerate mode can contribute to the transfer process at a time. In fact, the transfer rate becomes slightly slower due to the additional broadening from the dissipation of the second mode. On the contrary, at \(\Delta E\approx \sqrt{{(2\omega )}^{2}-{(2V)}^{2}}\), VAET processes in which the total vibrational energy of 2ω is supplied by a linear combination of the energy quanta from the two degenerate modes (2ω1 = 2ω2 = ω1 + ω2) interfere constructively. This leads to enhanced transfer rates compared to the single-mode case, where only the process involving a vibrational energy input of 2ω1 can assist the transfer.

a Transfer rate spectrum of degenerate VAET (ω1 = ω2 ≡ ω) with (V, g1, γ1, g2, γ2) = (0.200, 0.200, 0.045, 0.220, 0.018)ω. Red circles represent experimental data with error bars estimated via bootstrapping (see “Methods”). The solid red curve shows the transfer rate calculated from Eq. (4), using the definition in Eq. (5) and including spin decoherence (γz = 0.001ω) and motional dephasing of both modes (γim = 0.008ω, with i = 1, 2). The blue curve shows the numerical result of the single-mode VAET case, where ω2 = g2 = γ2 = γ2m = 0. b Experimental and numerical donor population evolution PD(t) versus the number of vibrational oscillations ωt/2π, using the same parameters as in the red circles and solid red curve in (a), respectively. Here, the detunings from the two tilt modes for encoding the degenerate vibrational energies are both set to δ1 = δ2 = − 2π × 10 kHz. c, d The same layout as in (a) and (b) for the non-degenerate VAET case (ω1 > ω2) with (V, g1, γ1, ω2, γz, γim) = (0.167, 0.275, 0.028, 0.667, 0.001, 0.007)ω1 and (g2, γ2) = (0.263, 0.019)ω2. The characteristic timescale is defined by the fast vibrational frequency ω1. In this case, the detuning from the inner (outer) tilt mode, which encodes the fast (slow) vibrational energy, is set to δ1 = −2π × 12 kHz (δ2 = −2π × 8 kHz). The red triangle, orange pentagon, green square, and blue circle markers correspond to ΔE = {1.00, 1.20, 1.50, 1.95}ω in the degenerate case and ΔE = {0.75, 0.92, 1.42, 1.60}ω1 in the non-degenerate case, respectively (marked by colored boxes in (a) and (c)). Near each resonant peak in the rate spectra, we label the total vibrational energy involved in the transfer.

In the non-degenerate case (ω1 > ω2), the second-order processes occur at different donor-acceptor energy offsets, and their corresponding transfer resonances can be resolved experimentally (see Fig. 5c). As such, the presence of the slow mode does not affect the transfer rates at the resonances involving ω1 and 2ω1 energy inputs. This is because, when we choose ω1/ω2 to be non-integer, there exists no non-trivial resonance involving an energy input of ℓ2ω2 from the slow mode, where ℓ1ω1 + ℓ2ω2 = ℓω1. However, additional resonances emerge instead from processes involving energy inputs given by linear combinations of the two non-degenerate vibrational energies. In Fig. 5c, we observe three additional resonances beyond the two existing resonances provided by the fast vibrational mode for the two-mode case. These peaks correspond to the processes involving vibrational energy inputs of ω2, 2ω2, and ω1 + ω2.

It is worth noting that, in both cases of mode degeneracy, the second-order processes associated with a vibrational energy contribution of ω1 + ω2 consist of two sets of coherent pathways (one phonon from the fast mode, then another from the slow mode, and vice versa) that interfere constructively (see Fig. 1b). This coherent addition of the two rate amplitudes leads to an approximate two-fold enhancement of the peak at ΔE ≈ 1.63ω1 in Fig. 5c with respect to the neighboring peaks at ΔE ≈ 1.29ω1 and ΔE ≈ 1.97ω1 that are associated with the second-order processes involving 2ω2 and 2ω1 energy inputs, respectively (see Section V of the Supplementary Information). This observation suggests that approximately half of the enhancement at ΔE ≈ 1.95ω in the two-mode degenerate case with respect to the single-mode case is attributed to the ω1 + ω2 pathways (see Section V of the Supplementary Information). While constructive interference of the two vibrational modes requires full coherent control over both degrees of freedom, our results also demonstrate that this coherent enhancement remains resilient in the presence of dissipation.

Discussion

In this work, we leverage the remarkable tunability of the trapped-ion platform to experimentally realize an open two-mode LVCM in two phenomenologically distinct regimes associated with CT and VAET, as well as their crossover. We simultaneously apply twelve carefully calibrated laser tones to independently control the coherent evolution of the qubit and the damping rates of two bosonic modes in a multi-species ion system. We observe enhanced transfer rates arising from the presence of the second mode across all vibronic coupling regimes, regardless of mode degeneracy, and point out their differences and similarities. We also attribute these enhancements to coherent effects in the transfer pathways, which persist even in the presence of dissipation. Furthermore, our conclusions can be extended to LVCM systems with more than two vibrational modes, where the same qualitative features identified in our findings remain (see Section VI of the Supplementary Information). This observation also highlights the necessity of considering anharmonicity in quantum dynamics models, where quantum scrambling can occur at resonances, transitioning coherent quantum behavior into chaotic dynamics39.

The experimental toolbox we deploy in this work is intrinsically scalable, as the same ion-laser couplings and sympathetic cooling techniques used to realize a two-mode, two-site LVCM can be extended to many vibrational modes and electronic sites without introducing additional physical overhead. In trapped-ion hardware, it is possible to include more molecular sites, as each extra qubit ion supplies a fully controllable two-level system that can encode a chromophore or charge-transfer center. Each additional qubit ion or coolant ion also adds three collective bosonic modes, which can be directly used for reservoir engineering by tailoring the spectrum of sympathetic-cooling lasers, without the need for digitization40. An arbitrary subset of these modes can then be endowed with individually programmable frequencies, coupling strengths, and dissipation rates, allowing the simulation of dissipative chemical dynamics in complex solvent environments41,42. Employing multiple engineered bosonic modes also enables the experimental realization of spin-boson models with tunable spectral densities, formed by a linear superposition of Lorentzian components21,37,43, crucial for exploring phenomena related to non-Markovian dynamics44, such as coherence trapping45,46,47,48, and dissipative quantum state engineering49.

State-of-the-art trapped-ion quantum computing hardware already employs ion crystals with tens of ions while retaining individual ion control50,51. Therefore, scaling up the analog trapped-ion simulator presented here to a few tens of qubits and engineered bosonic modes is within reach. In the current experiment, for example, the number of qubits and engineered bosonic modes is limited by purely technical factors, such as the ion chain vacuum lifetime and the available laser power. Trapped-ion systems also provide tunable long-range spin-spin couplings and high-fidelity entangled state generation via Molmer-Sorensen interactions52, which can be used to mimic long-range electronic couplings in Frenkel-exciton models53 and to study the role of delocalization in exciton transfer6,35,54.

This work establishes a clear, hardware-efficient roadmap for scalable trapped-ion analog platforms to investigate a wide range of open-system spin-boson models with multiple electronic configurations and vibrational modes, paving the way for the simulation of singlet fission processes55,56, electron-phonon propagation in condensed matter physics57, and realistic photochemical and bioenergetic processes54. In particular, we show how trapped ions enable the simulation of these models in the intermediate coupling regime, with the reorganization energy and electronic coupling strength being of the same order, which can be challenging for existing classical methods6,8,58.

Methods

Experimental setup

The experimental system used for this study is thoroughly described in ref. 20, where the dynamics of the single-mode LVCM in the CT regime are realized with four Raman 355 nm and two 435.5 nm laser tones. In this work, we include two additional tones to each beam to generate the terms associated with the second vibrational mode, resulting in a total of ten laser tones on the 355 nm and 435.5 nm lasers, over which we have full control of both amplitudes and frequencies. We also use the collective modes of the two-ion chain along both radial directions of the trap, specifically the y and z tilt modes (ωtilt,y ≡ ωtilt,1 = 2π ×3.151 MHz and ωtilt,z ≡ ωtilt,2 = 2π × 3.740 MHz), to encode the vibrational degrees of freedom in the two-mode LVCM Hamiltonian. The unused radial collective modes are the center-of-mass modes with ωcom,y ≡ ωcom,1 = 2π × 3.318 MHz and ωcom,z ≡ ωcom,2 = 2π × 3.882 MHz. Since the frequency separations among the available radial collective modes are set to be sufficiently large (Δωtrap,j ≳2π × 140 kHz), undesired off-resonant spin-phonon interactions, which are proportional to gj/(μi − ωtrap,j), can be neglected23,52. Here, μi is the 355 nm laser frequency detuning from the qubit resonance, used to generate the spin-dependent force on the target radial tilt mode i, and ωtrap,j is the relevant collective radial frequency considered for the off-resonant spin-phonon drive (j ≠ i).

Experimental sequence

The experimental sequence (see Fig. 2b) begins with Doppler cooling and Raman-resolved sideband cooling on all four collective radial modes of the chain, which results in an initial phonon population of both radial tilt modes, \({\bar{n}}_{0,i} \sim 0.1\)–0.2, which is set to match the independently measured \({\bar{n}}_{i}\). We then apply a π/2 pulse to map the z qubit basis to the y basis and two consecutive displacement operations via the spin-dependent optical force to prepare the system in the donor vibronic state, \(| D\left.\right\rangle \left\langle \right.D| \otimes {\rho }_{1-}\otimes {\rho }_{2-}\), where \({\rho }_{i-}={\sum }_{{n}_{i}}{e}^{-{n}_{i}{\omega }_{i}/{k}_{B}{T}_{i}}| {n}_{i-}\left.\right\rangle \left\langle \right.{n}_{i-}|\) represents a thermal state with temperature \({k}_{B}{T}_{i}\approx {\omega }_{i}/\log (1+1/{\bar{n}}_{i})\), and \(| {n}_{i\pm }\left.\right\rangle={{{\mathcal{D}}}}(\pm {g}_{i}/2{\omega }_{i})| {n}_{i}\left.\right\rangle\) are displaced Fock states associated with vibrational mode i. For simulating the open-system LVCM dynamics described by Eq. (4), we simultaneously apply the six 355 nm, four 435.5 nm, and two 935 nm laser tones. After evolving the system for time \({t}_{{{{\rm{sim}}}}}\), we apply another π/2 pulse to map the quantum state in the y basis back to the z qubit basis and measure the probability of the system being in the donor state PD = (〈σz〉 + 1)/2 via state-dependent fluorescence.

Transfer rate data analysis

We experimentally simulate the LVCM dynamics from t = 0 ms to \(t={t}_{{{{\rm{sim}}}}}\), where the finite simulation time \({t}_{{{{\rm{sim}}}}}\) ranges from 2 to 8 ms, corresponding to 24–65 vibrational cycles of the fast mode (defined by ω1t/2π), within which the system undergoing the first transfer resonance reaches equilibrium. Since Eq. (5) defines the transfer rate in the limit of \({t}_{{{{\rm{sim}}}}}\to \infty\), an offset correction is required when applying it to finite-time dynamics. Particularly, in the case of a strictly localized donor population, \({P}_{D}(t)={{{\rm{constant}}}}\), Eq. (5) still yields a non-zero transfer rate of \({k}_{T}=\frac{2}{{t}_{{{{\rm{sim}}}}}}\), which approaches zero only as \({t}_{{{{\rm{sim}}}}}\to \infty\). Therefore, we need to remove the undesired background from the finite-time evaluation of the non-zero steady-state donor population in the transfer rate calculations, as follows20,35:

We note that this background correction does not alter the characteristic features of the transfer rate spectra. By interpolating the donor population probability PD(t) for both the experimental and numerical data using the same time steps and applying the modified formula above, we obtain the transfer rates of the dynamics reported in the main text. As in ref. 20, we also use a resampling (bootstrapping) procedure at each time step of the PD(t) measurements to estimate the uncertainties of the extracted transfer rates. For each time step, we treat the experimental error as the standard deviation of a normal distribution centered at the measured mean value, from which the resampled datasets are drawn. We then use the standard deviation of the transfer rates calculated from the resampled datasets as the uncertainty associated with the reported rates.

Data availability

Source data for all main text figures are available in ref. 59. Any other data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

References

Behrman, E. C., Jongeward, G. A. & Wolynes, P. G. A monte carlo approach for the real time dynamics of tunneling systems in condensed phases. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 6277–6281 (1983).

Tanimura, Y. & Wolynes, P. G. The interplay of tunneling, resonance, and dissipation in quantum barrier crossing: a numerical study. J. Chem. Phys. 96, 8485–8496 (1992).

Kundu, S. & Makri, N. Intramolecular vibrations in excitation energy transfer: Insights from real-time path integral calculations. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 73, 349–375 (2022).

Scholes, G. D. et al. The quantum information science challenge for chemistry. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 16, 1376–1396 (2025).

Zhang, C., Kundu, S., Makri, N., Gruebele, M. & Wolynes, P. G. Quantum information scrambling and chemical reactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 121, e2321668121 (2024).

Fassioli, F., Dinshaw, R., Arpin, P. C. & Scholes, G. D. Photosynthetic light harvesting: excitons and coherence. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20130901 (2014).

Bakulin, A. A. et al. Mode-selective vibrational modulation of charge transport in organic electronic devices. Nat. Commun. 6, 7880 (2015).

Kang, M. et al. Seeking a quantum advantage with trapped-ion quantum simulations of condensed-phase chemical dynamics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 8, 340–358 (2024).

Johnson, A., Levinger, N., Kliner, D., Tominaga, K. & Barbara, P. Ultrafast experiments on the role of vibrational modes in electron transfer. Pure Appl. Chem. 64, 8 (1992).

Rather, S., Fu, B., Kudisch, B. & Scholes, G. Interplay of vibrational wavepackets during an ultrafast electron transfer reaction. Nat. Chem. 13, 70–76 (2020).

Arsenault, E. A., Schile, A. J., Limmer, D. T. & Fleming, G. R. Vibronic coupling in energy transfer dynamics and two-dimensional electronic–vibrational spectra. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 054201 (2021).

Dutta, R. et al. Simulating chemistry on bosonic quantum devices. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 20, 6426–6441 (2024).

Sparrow, C. et al. Simulating the vibrational quantum dynamics of molecules using photonics. Nature 557, 660–667 (2018).

Gorman, D. J. et al. Engineering vibrationally assisted energy transfer in a trapped-ion quantum simulator. Phys. Rev. X 8, 011038 (2018).

Valahu, C. H. et al. Direct observation of geometric-phase interference in dynamics around a conical intersection. Nat. Chem. 15, 1503–1508 (2023).

Whitlow, J. et al. Quantum simulation of conical intersections using trapped ions. Nat. Chem. 15, 1509–1514 (2023).

MacDonell, R. et al. Predicting molecular vibronic spectra using time-domain analog quantum simulation. Chem. Sci. 14, 9439–9451 (2023).

Sun, K. et al. Quantum simulation of polarized light-induced electron transfer with a trapped-ion qutrit system. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 6071–6077 (2023).

Maier, C. et al. Environment-assisted quantum transport in a 10-qubit network. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 050501 (2019).

So, V. et al. Trapped-ion quantum simulation of electron transfer models with tunable dissipation. Sci. Adv. 10, eads8011 (2024).

Sun, K. et al. Quantum simulation of spin-boson models with structured bath. Nat. Commun. 16, 4042 (2025).

Navickas, T. et al. Experimental quantum simulation of chemical dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc.147, 23566–23573 (2025).

Pagano, G., Adamczyk, W. & So, V. Fundamentals of trapped ions and quantum simulation of chemical dynamics. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.20412 (2025).

Renger, T., Madjet, M. E.-A., Schmidt am Busch, M., Adolphs, J. & Müh, F. Structure-based modeling of energy transfer in photosynthesis. Photosynth. Res. 116, 367–388 (2013).

Lorenzoni, N. et al. Full microscopic simulations uncover persistent quantum effects in primary photosynthesis. Sci. Adv. 11, eady6751 (2025).

Chen, L., Shenai, P., Zheng, F., Somoza, A. & Zhao, Y. Optimal energy transfer in light-harvesting systems. Molecules 20, 15224–15272 (2015).

Schlawin, F., Gessner, M., Buchleitner, A., Schätz, T. & Skourtis, S. S. Continuously parametrized quantum simulation of molecular electron-transfer reactions. PRX Quantum 2, 010314 (2021).

Li, Z.-Z., Ko, L., Yang, Z., Sarovar, M. & Whaley, K. B. Unraveling excitation energy transfer assisted by collective behaviors of vibrations. N. J. Phys. 23, 073012 (2021).

Matyushov, D. V. Reorganization energy of electron transfer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 7589–7610 (2023).

Onuchic, J. N. Effect of friction on electron transfer: the two reaction coordinate case. J. Chem. Phys. 86, 3925–3943 (1987).

Barbara, P. F., Meyer, T. J. & Ratner, M. A. Contemporary issues in electron transfer research. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 13148–13168 (1996).

Barthel, E. R., Martini, I. B. & Schwartz, B. J. How does the solvent control electron transfer? experimental and theoretical studies of the simplest charge transfer reaction. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 12230–12241 (2001).

Hsu, C.-P. Reorganization energies and spectral densities for electron transfer problems in charge transport materials. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 21630–21641 (2020).

Skourtis, S. S., Da Silva, A. J. R., Bialek, W. & Onuchic, J. N. New look at the primary charge separation in bacterial photosynthesis. J. Phys. Chem. 96, 8034–8041 (1992).

Fallas Padilla, D. et al. Delocalized excitation transfer in open quantum systems with long-range interactions. PRX Quantum 6, 040301 (2025).

Garg, A., Onuchic, J. N. & Ambegaokar, V. Effect of friction on electron transfer in biomolecules. J. Chem. Phys. 83, 4491–4503 (1985).

Lemmer, A. et al. A trapped-ion simulator for spin-boson models with structured environments. N. J. Phys. 20, 073002 (2018).

Schneider, C., Porras, D. & Schaetz, T. Experimental quantum simulations of many-body physics with trapped ions. Rep. Prog. Phys. 75, 024401 (2012).

Zhang, C., Gruebele, M., Logan, D. E. & Wolynes, P. G. Surface crossing and energy flow in many-dimensional quantum systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 120, e2221690120 (2023).

Macridin, A., Spentzouris, P., Amundson, J. & Harnik, R. Digital quantum computation of fermion-boson interacting systems. Phys. Rev. A 98, 042312 (2018).

Plenio, M. B., Almeida, J. & Huelga, S. F. Origin of long-lived oscillations in 2d-spectra of a quantum vibronic model: electronic versus vibrational coherence. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 235102 (2013).

Tiwari, V., Peters, W. K. & Jonas, D. M. Electronic resonance with anticorrelated pigment vibrations drives photosynthetic energy transfer outside the adiabatic framework. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 1203–1208 (2013).

Leggett, A. J. et al. Dynamics of the dissipative two-state system. Rev. Mod. Phys. 59, 1–85 (1987).

Debecker, B., Martin, J. & Damanet, F. Controlling matter phases beyond Markov. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 140403 (2024).

Huelga, S. F., Rivas, A. & Plenio, M. B. Non-markovianity-assisted steady state entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 160402 (2012).

Addis, C., Brebner, G., Haikka, P. & Maniscalco, S. Coherence trapping and information backflow in dephasing qubits. Phys. Rev. A 89, 024101 (2014).

Kamar, N. A., Paz, D. A. & Maghrebi, M. F. Spin-boson model under dephasing: Markovian versus non-Markovian dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 110, 075126 (2024).

Jiao, L., Pu, H. & An, J.-H. Protecting spin squeezing from decoherence. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.05016 (2025).

Zhu, M., So, V., Pagano, G. & Pu, H. Dissipation-assisted steady-state entanglement engineering based on electron transfer models. Phys. Rev. A 112, 012617 (2025).

Foss-Feig, M., Pagano, G., Potter, A. C. & Yao, N. Y. Progress in trapped-ion quantum simulation. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 16, 145–172 (2024).

Mueller, N., Wang, T., Katz, O., Davoudi, Z. & Cetina, M. Quantum computing universal thermalization dynamics in a (2+1) d lattice gauge theory. Nat. Commun. 16, 5492 (2024).

Monroe, C. et al. Programmable quantum simulations of spin systems with trapped ions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025001 (2021).

Jang, S. J. & Mennucci, B. Delocalized excitons in natural light-harvesting complexes. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 035003 (2018).

Sneyd, A. J. et al. Efficient energy transport in an organic semiconductor mediated by transient exciton delocalization. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh4232 (2021).

Collins, M. I., Campaioli, F., Tayebjee, M. J. Y., Cole, J. H. & McCamey, D. R. Quintet formation, exchange fluctuations, and the role of stochastic resonance in singlet fission. Commun. Phys. 6, 64 (2023).

Campaioli, F., Pagano, A., Jaschke, D. & Montangero, S. Optimization of ultrafast singlet fission in one-dimensional rings towards unit efficiency. PRX Energy 3, 043003 (2024).

Knörzer, J., Shi, T., Demler, E. & Cirac, J. I. Spin-Holstein models in trapped-ion systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 120404 (2022).

Somoza, A. D., Marty, O., Lim, J., Huelga, S. F. & Plenio, M. B. Dissipation-assisted matrix product factorization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 100502 (2019).

So, V. Dataset for: quantum simulation of charge and exciton transfer in multi-mode models using engineered reservoirs. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17539557.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Diego Fallas Padilla for careful reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions. This work was supported in part by the NOTS cluster operated by Rice University’s Center for Research Computing (CRC). G.P. acknowledges support from the Welch Foundation Award (grant no. C-2154), the Office of Naval Research Young Investigator Program (grant no. N00014-22-1-2282), the NSF CAREER Award (grant no. PHY-2144910), and the Office of Naval Research (grant no. N00014-23-1-2665 and N00014-24-1-2593). We acknowledge that this material is based on work supported by the U.S Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Nuclear Physics under the Early Career Award (grant no. DE-SC0023806). The isotopes used in this research were supplied by the US Department of Energy Isotope Program, managed by the Office of Isotope R&D and Production. H.P. acknowledges support from the NSF (grant no. PHY-2513089) and the Welch Foundation (grant no. C-1669). Work at the Center for Theoretical Biological Physics was supported by the NSF (grant no. PHY-2019745). J.N.O. was also supported by the NSF (grant no. PHY-2210291). P.G.W. was also supported by the D.R. Bullard-Welch Chair at Rice University (grant no. C-0016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.S., M.D.S., A.M., G.T., R.Z., and G.P. contributed to the experimental design, construction, data collection, and analysis of this experiment. V.S., M.Z., H.P., J.N.O., P.G.W., and G.P. contributed to the paper’s conceptualization and supporting theory and numerics. All authors contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

R.Z. is a cofounder and chief executive officer of TAMOS Inc. G.P. is a cofounder and chief scientist of TAMOS Inc. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

So, V., Duraisamy Suganthi, M., Zhu, M. et al. Quantum simulation of charge and exciton transfer in multi-mode models using engineered reservoirs. Nat Commun 17, 438 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67116-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67116-6