Abstract

Infection with human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) can result in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma and HTLV-1 associated-myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis. The Gag polyprotein – the major structural protein – is crucial for driving virus particle assembly, with the capsid (CA) domain as the key determinant for Gag multimerization. Here, we characterize the immature CA lattice from immature virus particles by using cryo-electron microscopy and tomography (cryo-EM/ET). We report resolving the immature CA lattice to 3.4 Å resolution by single particle analysis (SPA). Our reconstruction reveals that the lattice is stabilized through a trimeric NTD inter-hexamer interface and a dimeric CTD inter-hexamer interface. Further analysis by cryo-ET reveals clear heterogeneity, notably the varying lattice curvatures and the varying distances from the CA layer to the membrane. Intriguingly, inositol hexakisphosphate (IP6) is dispensable for HTLV-1 immature particle assembly and proper immature lattice formation. These observations provide deeper insights into the molecular basis of HTLV-1 immature particle morphology as well as aid in revealing therapeutic targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is the prototypical deltaretrovirus, and is the causative agent of an adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL) and HTLV associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis (HAM/TSP)1,2. About 2–6% individuals living with HTLV-1 will develop either disease3,4. Currently, there are no approved therapeutics to prevent or treat the infection. Like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), HTLV-1 encodes the Gag structural polyprotein that is required for viral assembly5. The HTLV-1 Gag contains a matrix (MA), capsid (CA), and nucleocapsid (NC) domain. The MA domain is critical for targeting Gag to the plasma membrane, CA is required for Gag oligomerization by forming the immature CA lattice, and NC packages the single-stranded RNA viral genome6,7,8. Unlike HIV, the HTLV-1 Gag polyprotein does not contain the spacer peptide regions (SP1 and SP2) or the p6 domain.

The structure of CA proteins among several retroviruses has been studied, revealing a highly conserved tertiary structure despite a divergence in the amino acid sequence. The CA tertiary structure consists of two separate domains—a N-terminal domain (NTD) and a C-terminal domain (CTD), connected via a flexible linker9,10,11,12,13. Structural analysis of the immature HIV type 1 (HIV-1) lattice identified a wine-glass morphology, where the CA-NTD represents the cup of the glass and the CA-CTD and SP1 represent the stem11,12. The HIV-1 CA-NTD supports the hexameric lattice via a trimer interface from helix 2 and a dimer interface from helix 1, while helix 9 forms the dimer interface in the CA-CTD12. Similar arrangements for the immature lattice have been noted with HIV type 2 (HIV-2)14, equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV)15, murine leukemia virus (MLV)9, and human endogenous retrovirus K (HERV-K)16. These immature lattice structures also contain a ring of 6 helices on the C-terminal tail of CA or through a spacer peptide region, termed the 6-helix bundle (6HB)9,15,16. The HIV-1 6HB functions to stabilize the hexamer of the Gag lattice, can bind to the cofactor inositol hexakisphosphate (IP6), and serves as the binding site of HIV-1 maturation inhibitors11,14,15,17. Structural characterization of immature retroviral Gag lattices has largely relied on the use of cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET)9,11,15,16,18 rather than single particle analysis (SPA) due to difficulties from the geometry of the lattice, the proximity to the membrane, and dampened lattice signal from other viral components. In situ single particle analysis of purified virus particles allows for improved resolution compared to cryo-ET and provides relevant structural information that may not be present from analysis of in vitro assemblies (e.g., presence of cellular co-factors)19.

Previous studies have indicated that HTLV-1 immature particles possess unique morphological features compared to that of retroviruses in other genera, implying that deltaretroviruses are distinct in regards to immature particle morphology. HTLV-1 immature particles often contain an incomplete Gag lattice with portions of the lattice deviating from the curvature of the viral membrane and appear to have a flattened lattice20,21. However, to date, a thorough analysis of the immature HTLV-1 lattice curvature has not been conducted, and it remains an open question if these observations are artifacts of two-dimensional imaging. It has been established that the primary driver for HIV-1 assembly is the CA-CTD and SP1, while the HIV-1 CA-NTD is dispensable for immature lattice formation22,23. In contrast, previous studies with HTLV-1 have indicated the opposite—i.e., the CA-NTD is required for proper lattice formation while mutations in the CA-CTD led to limited effects on immature lattice formation24,25,26,27. HTLV-1 CA-CTD is not completely dispensable for immature particle production, as has been observed with the HIV-1 CA-NTD6,25. Recent subtomogram averaging of HTLV-1-like particles and in vitro assembled helical tubes showed the CA-NTD forms the majority of the intra-hexamer and inter-hexamer interfaces, while the CA-CTD forms an inter-hexamer dimer interface and supplies no intra-hexamer interactions18. However, only the CA-NTD was resolved to high resolution from the in vitro assemblies, whereas the resolution in the CA-CTD was limited due to flexibility. Improving the resolution in the CA-CTD is critical for better understanding its role in HTLV-1 immature particle assembly, as is validating the in vitro CA-NTD structure in situ.

Depletion of IP6 from virus-producing cells drastically decreases viral infectivity for many lentiviruses28,29. Packaging of IP6 into the immature Gag lattice of HIV-1 particles is coordinated through electrostatic interactions between the highly negatively charged IP6 molecule and two lysine rings formed by K158 and K227 (based upon CA numbering)28,30,31. Upon virus maturation, IP6 binds to the central pore of the hexamer in the CA-NTD at the R18 and K25 rings32,33. IP6 promotes proper infectivity by strongly stabilizing the mature HIV-1 core and allowing for efficient reverse transcription32,34. The functional conservation of IP6 in virus assembly and maturation among retroviral genera has not been fully explored. Recently, it was shown that MLV, a gammaretrovirus, packages IP6 into the immature lattice, albeit at lower levels than HIV-1. However, unlike HIV-1, MLV infectivity was more sensitive to IP6 depletion in the target cell rather than the virus-producing cell29,35. To date, there is currently no knowledge regarding the role of IP6 in deltaretrovirus particle assembly and maturation. Such information can provide insights into the evolutionary conservation of IP6 in the viral life cycle among retroviral genera.

In this study, we investigated HTLV-1 immature particle morphology through a combination of cryo-electron microscopy and tomography (cryo-EM/ET) to generate a reconstruction of the assembled immature lattice. The structure of the CA region in the Gag lattice was determined to 3.4 Å resolution using SPA, the highest resolution of HTLV-1 immature particles to date, highlighting SPA as a powerful tool for immature CA lattice determination. Tomography of HTLV-1 particles highlighted the morphological heterogeneity, corroborating previously observed phenotypes from two-dimensional analysis of HTLV-1 particles20,21. Furthermore, improved resolution in the CA-CTD and structure-guided mutagenesis studies allow for identification of residues in the CA-CTD dimer interface that have a critical role for particle assembly. Intriguingly, IP6 is found to be dispensable for immature particle production, despite IP6 enhancing HTLV-1 CA assembly in vitro and a weak unidentified density in the CA-NTD hexamer pore. Overall, our observations provide a clear structural basis for previous reports on the pleomorphic morphology of the HTLV-1 immature Gag lattice, further expand the understanding of these phenotypes, and provide evidence implicating that IP6 has a limited role in driving HTLV-1 immature particle assembly.

Results

Cryo-EM reconstruction of the immature HTLV-1 Gag lattice

A SPA reconstruction of the HTLV-1 immature CA lattice was generated from purified HTLV-1 particles by co-expressing only the HTLV-1 structural proteins, Gag and envelope, in HEK293T cells (Fig. 1). As no HTLV-1 protease is present in the system, the Gag lattice in particles is trapped in their immature lattice morphology, and no mature cores are generated. A comparable methodology for SPA has been recently utilized for analysis of the immature Gag lattice of HIV-214. Particle picking was expanded to include all lattice regions below the viral membrane, rather than just the lattice regions tangent to the viral particle (Fig. 1a). This greatly enhanced the number of particles included in the reconstruction and increased the diversity of views of the lattice (Supplementary Fig. 1d), which improved the quality and resolution of the reconstruction. The reconstruction was generated by using six-fold symmetry centered on the central capsid hexamer and reached a global resolution of 3.4 Å (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Local resolution calculations revealed higher resolution in the CA-NTD compared to the CA-CTD, implicating flexibility in the CA-CTD (Fig. 1d). A 3DFlex refinement36 of the reconstruction depicts the flexibility in the CA-CTD relative to the CA-NTD that is caused by the varying curvatures in the immature lattice (Supplementary Movie 1). The resolution obtained allowed for the generation of a model of the in situ immature HTLV-1 CA lattice, comprising residues W15 to P207 (CA numbering) (Fig. 1e, f). At low resolution and low contour, a faint spherical density is observed in the central pore of the CA-NTD hexamer (Supplementary Fig. 1e–g).

a Representative HTLV-1 immature particles. Shown are two representative HTLV-1 immature particles from the cryo-EM dataset, where the red circles represent a simplified model of the particle picking scheme, highlighting all regions of the Gag lattice used in the reconstruction. Scale bar, 50 nm. b Single particle reconstruction. Shown is the top view of the single particle lattice reconstruction for HTLV-1 Gag. The map was locally sharpened using deepEMhancer57. c Side view of the immature Gag lattice. The CA-NTD and CA-CTD are colored as blue and gold, respectively. d Local resolution estimates. Shown is a cross-section through the central CA hexamer. The density is colored by the local resolution estimate. e Annotated side views of the modeled HTLV-1 CA regions. Shown is a modeled region of a CA monomer with annotated helices. The CA-NTD and CA-CTD are colored in blue and gold, respectively. f Helix model fitting into the cryo-EM density. Shown is helix 4, highlighting the agreement of the fitted model into the density.

Morphology of the HTLV-1 immature Gag lattice

The SPA cryo-EM reconstruction revealed the CA region of the Gag lattice was the best resolved Gag subdomain. The matrix and nucleocapsid had densities visible at low resolution within the CA reconstruction but were unable to be modeled (Supplementary Fig. 1e). The CA monomers consist of distinct CA-NTD and CA-CTD domains, connected through a flexible linker, like other described immature retroviral capsids9,12,15,16. Similar to these other retroviral lattices, the hexamer lattice is supported by a three-fold interface in the CA-NTD and a two-fold interface in the CA-CTD (Fig. 2b, d). However, the HTLV-1 Gag lattice does not adopt the typical wine-glass morphology that has been described for the other retroviral immature Gag lattices (Supplementary Movie 2). Rather, the CA-NTD forms a tight pore at the center of the hexamer, adopting a conformation similar to that of the CA-NTD seen in mature retroviral CA lattices (Supplementary Fig. 3a-f)37,38. The root mean square deviation of the backbone for the best aligned monomer within the central hexamer between the immature HTLV-1 CA-NTD and the mature bovine leukemia virus (BLV) or mature HIV-1 CA-NTD is 1.23 Å and 5.22 Å, respectively. For the HTLV-1 immature lattice, the CA-NTD provides most of the inter-hexamer and intra-hexamer interactions (Fig. 2). The CA-NTD trimerizes with a three-fold symmetric interface; one monomer from the central hexamer forms contacts with two other CA-NTD molecules, each from adjacent hexamers. This three-fold interface is composed of three copies of helix 4 packed together with helix 5, adding further interactions (Fig. 2b, c). The CA-CTD dimerizes with a two-fold symmetric interface with an adjacent hexamer’s CA-CTD, involving intermolecular contacts from residues on a 310-helix, helix 8, and helix 9 (Fig. 2d–h). Interestingly, there is no significant interface and limited intermolecular contacts between CA-CTD molecules within the same hexamer. Further, no analogous 6HB structure was resolved beyond the CTD (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 1e). Overall, the architecture of the immature Gag CA lattice from SPA agrees with recent tomography approaches using HTLV-1-like particles18.

a Top view of the immature lattice. The density of the CA-NTD in the central hexamer is colored blue; the CA-CTD is colored gold. b Fitting of the CA-NTD from seven hexamers. The blue dashed box highlights the CA-NTD trimer inter-hexamer interface. c Detailed view of the CA-NTD trimer interface boxed in (b), showing the helix 4 and helix 5 interactions. d Fitting of the CA-CTD from seven hexamers. The gold dashed box highlights the dimer inter-hexamer interface. e Shown is a detailed top view of the CA-CTD dimer inter-hexamer interface boxed in (c), highlighting the interactions between the 310 helix, helix 8, and helix 9. f Detailed view of (e), highlighting the hydrophobic pocket formed from amino acid residues W133, I168, and L172. g Rotated view of (e), highlighting the interactions between helix 8 and helix 9. h Detailed view of (g), highlighting the interactions between residues S171, Y174, S175, K179, Q182, and Q186 on helix 8 and 9. The dashed lines represent predicted hydrogen bonds. i A representative immunoblot from three-independent experiments of immature particle production from mutations at residues highlighted in (f) and (h). Particle production was measured via Gag released into the cell culture supernatant. j Immunoblot quantification of (i) representing virus release efficiency. Quantification was from the three-independent replicates, and the significance was determined relative to WT by using an unpaired two-sided t-test. **, P < 0.001; *, P < 0.05. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). The exact p values are: W133A < 0.0001, I168A < 0.0001, L172A = 0.0099, Y174A = 0.0026, S175A < 0.0001, Q182A = 0.023.

Mutations in the CTD dimer interface are detrimental to particle production

Interactions between the CA-NTD trimer interface have been previously well described for the HTLV-1 immature Gag lattice18,24. However, flexibility in the CA-CTD has prevented high-resolution determination of the CA-CTD dimer interface. Furthermore, little is known regarding the role of the CA-CTD dimer interface in immature particle production. The total interface area between adjacent CA-CTD molecules is 1166 Å2. The orientation of the CA-CTD monomers reveals that the main interfaces consist of a 310-helix that interacts with helix 8 of the adjacent CA-CTD monomer, symmetric helix 8-helix 8 interactions, and symmetric helix 9-helix 9 interactions (Fig. 2e–h). The improved resolution in the CA-CTD region allowed for structure-guided alanine mutagenesis to probe specific residues important for maintaining this interface and to better understand the role of the CA-CTD in HTLV-1 assembly. Briefly, WT or mutated HTLV-1 Gag was co-transfected with HTLV-1 envelope into HEK293T cells. The assembly efficiency of the mutant was compared to WT by measuring the amount of virus released into the viral supernatant via an anti-HTLV-1 p24 immunoblot (Fig. 2i). Full length Gag is expected at 47 kDa, however, smaller bands are commonly seen from HTLV-1 Gag particles18,39, likely due to non-specific cleavage from host proteases as the HTLV-1 protease is not present in these experiments. Mutation of W133 (310-helix) and I168 (helix 8) severely decreased particle production, while mutation of L172 (helix 8) decreased particle production two-fold (Fig. 2i, j). These observations suggest a hydrophobic pocket forms between the 310-helix and the top of helix 8, analogous to the hydrophobic pocket in the HIV-1 CA-CTD11 (Fig. 2e, f). Further down along helix 8, mutation of S175 drastically diminished particle production while mutation of Y174 resulted in a two-fold reduction in immature particle production (Fig. 2i, j). Asymmetric copies of S175 form a network of hydrogen bonds with the backbone carbonyl of S175 and the hydroxyl of S171 on the adjacent CA monomer (Fig. 2h). Symmetric copies of Y174 on helix 8 (Fig. 2h) appear to form π-π stacking interactions to help stabilize the interface, as the Y174A mutation resulted in a two-fold reduction in immature particle production (Fig. 2i, j). The Q182A (helix 9) mutation resulted in greater than a two-fold reduction in particle production (Fig. 2i, j). Q182 appears to form hydrogen bonds with residues Y174 and Q186 on the adjacent monomer (Fig. 2h).

Other noted residues that are not included in the shown immunoblot and quantification (Fig. 2h–j) include S171 (helix 8), K179 (helix 9), and Q186 (helix 9). As previously mentioned, residue S171 is part of the extensive hydrogen bonding network with S175, supplying S171-S171 and S171-S175 interactions (Fig. 2h). Residue K179 is predicted to form hydrogen bonding to the backbone carbonyl of residue Q186 (Fig. 2h). Lastly, Q186 is predicted to form hydrogen bonding with the adjacent Q186 or Q182 residues (Fig. 2h). However, mutation at these residues did not significantly reduce particle production (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Cryo-ET reveals incomplete and heterogeneous immature Gag lattice morphologies

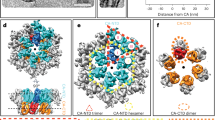

Previously, we observed HTLV-1 particles with a heterogeneous and incomplete Gag lattice based on transmission electron microscopy20,21. Specifically, it was noted that regions of the Gag lattice had varying curvatures within the same particle and often had flattened patches. Furthermore, these flattened regions were found to coincide with larger gaps between the viral membrane and the CA region of the Gag lattice20,21. To better understand these features of the HTLV-1 lattice in three-dimensions, we utilized cryo-ET to map individual CA hexamer positions within the Gag lattice (Fig. 3a–e). Iterative rounds of particle alignment and symmetry expansion were conducted to determine accurate hexamer positions, poorly aligned particles were removed after each round. The iterative approach provides us with good confidence that the gaps noted in the lattice are real. Based on the derived coordinates and angles of the CA hexamers, the local mean curvature was estimated based on neighboring hexamers. As expected, the local curvature estimates varied significantly, even within the same virus particle, with radii ranging from 28 nm to 75 nm (Fig. 3c, e). The average distance between individual hexamers to the membrane was determined to be 16.3 ± 2.49 nm. Measurements were conducted from the top of the CA-NTD to the outer layer of the viral membrane. The distribution was slightly skewed to the right, likely representing the patches of lattice that visibly appear further from the membrane (Fig. 3f). The identification of lattice positions allowed for a 7.9 Å resolution determination via subtomogram averaging (Figs. 3g and S1b). The subtomogram averaging reconstruction is similar to that of the SPA reconstruction (Fig. 3g), providing confidence in the accuracy of the curvature and the distance analysis.

a Two-dimensional tomogram z-slices. Shown is a two-dimensional z-slice of different particles from three tomograms (z-slice, 6.81 nm). Scale bar, 50 nm. b Gag CA domain hexamer model. Shown is a model of Gag CA domain hexamers present in the tomogram in (a). The colors are based on the cross-correlation score for each hexamer to the reference map. c Local curvature estimates. The mean local curvature estimates of each individual hexamer from (b) are indicated. The color of each hexamer represents the mean local curvature of the CA lattice in that region. Red represents a higher curvature while blue represents less curvature. d Rotated view cross-correlation. Shown is the rotated view of (b) with the cross-correlation indicated. e Rotated view of local curvature. Shown is the rotated view of (c) with the local curvature indicated. f CA to membrane measurements. The histogram shows the distance from the top of the CA-NTD to the outer edge of the membrane for each identified hexamer location. The average distance was 16.3 ± 2.49 nm, n = 4515. g Subtomogram averaging reconstruction. The top and side view of the subtomogram averaging reconstruction at 7.9 Å resolution. The CA-NTD is shown in blue, and the CA-CTD is shown in gold.

IP6 is dispensable for immature HTLV-1 particle production and lattice formation

As noted, a faint spherical density was observed in the central pore of the CA-NTD hexamer, which is a similar location to the binding site of IP6 in the mature HIV-1 lattice (Fig. 4a). The density disappears following map sharpening and is only present in lowpass filtered maps at low contour (Figs. 4a and S1e–g). The density is weak compared to the CA protein regions (Supplementary Fig. 1f, g) and to the IP6 density seen in other retroviral immature CA reconstructions from cell derived immature particles11,14. However, the density is present in adjacent hexamers off the symmetry axis, implying that it is not an artifact from the imposed C6 symmetry (Fig. 4a). Similarly, the density is present in a non-symmetric reconstruction and varies at different hexamer center positions, suggesting not every hexamer binding site is occupied by the density or there is flexibility in the location (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Given the density is near a ring of lysines, K18, and the established role for IP6 as an important co-factor for lentiviral particle assembly, we performed a molecular dynamics simulation of HTLV-1 in the presence of IP6 to better understand the capacity of HTLV-1 to interact with IP6 (Fig. 4b). Interestingly, we observed IP6 can be highly coordinated by R13 and K18 (Fig. 4b). Residue R13 had not been previously modeled from our reconstruction (Fig. 1e). To test the ability of HTLV-1 CA to utilize IP6 or other polyanions for assembly, we used an in vitro assembly assay of purified HTLV-1 CA39. IP6 and mellitic acid greatly enhanced CA assembly, as noted by the increasing proportion of CA in the pellet fraction at increasing concentrations of the polyanion (Fig. 4c). The CA protein in the pellet fraction was confirmed to form ordered assemblies via negative stain transmission electron microscopy, by either forming helical tubes with the addition of IP6 or crystal sheets with addition of mellitic acid (Fig. 4e). The proportion of CA in the pellet fraction did not increase with the addition of sodium phosphate or dNTPs, suggesting they are unable to stimulate HTLV-1 CA assembly in vitro (Fig. 4c). Mutagenesis of R13 and K18 was conducted to test their predicted role in coordinating IP6. Indeed, the amount of CA recovered in the pellet was greatly diminished for the R13A and K18A single mutations compared to WT and required higher concentration of IP6 (Fig. 4d). The R13A and K18A single mutants maintained their ability to assemble into ordered helical tubes, but only at 250 µM IP6 (Fig. 4e). Mutation of both R13A/K18A resulted in no CA recovered in the pellet for all IP6 concentrations tested (Fig. 4d). Furthermore, no ordered assemblies were seen for R13A/K18A via negative stain at 250 µM IP6, suggesting a loss of binding (Fig. 4e).

a Top view of the central hexamer model fitted into a lower resolution and unsharpened density. The red boxes highlight the small density present at the center of each hexamer. b Molecular dynamics simulation of HTLV-1 CA coordinating IP6. Six copies of R13 and K18 in the CA-NTD can coordinate IP6. The central pore density from (a) is shown for the placement of IP6 in the simulation. c, d In vitro HTLV-1 CA assembly assay. Shown are SDS-PAGE analysis of purified HTLV-1 CA after the addition of IP6 or different polyanion at varying concentrations to WT CA or predicted IP6 binding mutants. The gels are representative from three-independent experiments e Negative stain TEM. Shown are representative negative stain TEM micrographs from one replicate of the resuspended pellet from the corresponding polyanion type, polyanion concentration, and HTLV-1 CA type from (c) to (d). Scale bar, 200 nm. f Immunoblot analysis of immature particle production. Cell culture supernatants from cells producing immature HTLV-1 or HIV-1 particles were analyzed by immunoblot, shown is one representative blot from three-independent experiments. Particle production was compared between WT 293T and IP6-depleted cells. g Quantification of the immunoblot analysis from (f) was done from three-independent replicates, and the significance was determined using an unpaired two-sided t-test by comparing particle production from the IP6-depleted cells to that from WT cells for each virus. *, P < 0.001. The error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). The exact p-values are: HIV-1 IPPK KO = 0.0005 and HIV-1 IPMK KO < 0.0001. h Immature particle morphology. Cryo-EM micrographs of immature HTLV-1 particles purified from IPPK KO cells that were co-transfected with the expression plasmid encoding the MINPP1 phosphatase. Scale bar, 100 nm. Micrographs are representative images from one purification.

The heterogeneity of the helical tubes, specifically their preference to form multiple layers and aggregate together (Fig. 4e), prevented structure determination to validate the binding site of IP6. A low resolution subtomogram averaging reconstruction was conducted on a CA A94K mutation that preferentially formed microcrystals with addition of 250 µM IP6 (Supplementary Fig. 5). A strong density is apparent at the center of the CA-NTD pore, consistent with the predicted IP6 binding site (Supplementary Fig. 5c). The immature CA-NTD structure can fit well into this reconstruction, providing evidence that the in vitro assemblies form the immature lattice and that IP6 can bind to the immature structure (Supplementary Fig. 5c).

Given the role of IP6 in the HIV-1 life cycle, the ability of IP6 to enhance HTLV-1 CA assembly in vitro, and the small density in the reconstruction, experiments were conducted to test if IP6 has a role in HTLV-1 immature particle assembly. To do this, a previously reported 293T cell line with knockout of either inositol pentakisphosphate 2-kinase (IPPK KO) or inositol polyphosphate kinase (IPMK KO) was used to produce particles28,29. IPPK is responsible for converting IP5 to IP6, while IPMK is responsible for converting IP4 to IP5 and IP5 to IP6. Transient overexpression of the multiple inositol polyphosphate 1 (MINPP1)—which converts IP6 to IP5, IP5 to IP4, and IP4 to IP3— enhances IP6 and IP5 depletion in both IPPK and IPMK KO cells40. HTLV-1 Gag and envelope were co-transfected with an empty vector into the WT control 293T cells or co-transfected with MINPP1 into either the IPPK or the IPMK KO cell lines. Co-transfection of the KO cell lines with HIV-1 Gag and envelope was selected to use as a control, based upon reports that IP6 depletion decreased immature particle production28,29,40. As expected, there was a reduction in HIV-1 immature particle production in both the IPPK KO and IPMK KO cells overexpressing MINPP1 compared to that of WT control 293T cells, measured by the amount of p24 capsid protein released into the cell culture supernatant (Fig. 4f, g). Intriguingly, there was no significant difference in the immature HTLV-1 particle production between the 293T WT cells and the IPPK KO and IPMK KO cells transiently overexpressing MINPP1 (Fig. 4f, g). This observation provides evidence in support of the conclusion that IP6 is not required for immature HTLV-1 particle assembly. To confirm whether HTLV-1 particles produced in IP6-depleted cells formed a WT particle morphology, particles were purified from IPPK KO cells overexpressing MINPP1 and then analyzed by cryo-EM (Fig. 4h). Analysis of particle morphology revealed a WT Gag lattice with no morphological defects, providing further support of the conclusion that IP6 depletion does not impact HTLV-1 particle assembly or Gag lattice morphology.

Discussion

Comparative analysis of the HTLV-1 and HIV-1 immature lattice architectures can provide insights into the molecular determinants for their morphological differences. Despite the large organizational differences in the HTLV-1 and HIV-1 lattice, the tertiary structures are well conserved, with the lattice structure being composed of a three-fold interface in the CA-NTD and a two-fold interface in the CA-CTD11,14,15. However, HIV-1 and other lentiviruses are predominantly stabilized via a hydrophobic inter-hexamer CA-CTD dimer interface and strong intra-hexamer interactions via the 6HB11,14,15. HIV-1 also contains both intra- and inter-hexamer interactions within the CA-NTD11. Unlike HIV-1, HTLV-1 lacks a 6HB, and there are no intra-hexamer CA-CTD interactions (Figs. 1c and 2d), resulting in the hexamer only being stabilized via the CA-NTD (Fig. 2b). The HTLV-1 CA-NTD organization mimics the organization seen in the mature CA structure (Supplementary Fig. 3a–f), where the CA-NTD is the only domain stabilizing the hexamer structure41. During the HIV-1 lifecycle, IP6 has an important role in stabilizing the immature and mature hexamer structures by neutralizing the strong positive charge in the central pore28,30,31,32,33,40. IP6 is packaged in the 6HB of the immature HIV-1 lattice (K158 and K227), then shifts to the central pore of the CA-NTD following maturation (K18 and K25)30,32,33. Given that the HTLV-1 immature lattice lacks a 6HB and the immature CA-NTD functions like a mature CA-NTD, any packaging of IP6 in the immature HTLV-1 lattice would likely be coordinated by amino acid residues in the CA-NTD to stabilize the hexamer structure.

IP6 has been shown to be critical for lentiviral assembly, maturation, and infectivity30,31,32,33,34,40. Surprisingly, depletion of IP6 in cells did not impact HTLV-1 immature particle assembly and lattice morphology, despite both the presence of a small density at the center of the CA hexamer as well as the ability of IP6 to significantly enhance assembly of purified HTLV-1 CA in vitro (Fig. 4). It is interesting to note that immature particles produced by MLV, a gammaretrovirus, package less IP6 than HIV-135. However, IP6 was found to be critical for MLV core stabilization, proper reverse transcription during infection, and was more sensitive to IP6 levels in target cells than in virus-producing cells. These observations were hypothesized to be due to the mature MLV core partially disassembling in the cytosol, which would result in the release of any packaged IP635. Given HTLV-1 has a polyhedral mature core rather than a fullerene cone42, it is possible that HTLV-1 may also be more reliant on IP6 from the target cell rather than the virus-producing cell, resulting in lower levels of IP6 being packaged in the immature particles. This would help explain the weak density in the reconstruction and the HTLV-1 immature lattice being more adaptable to the depletion of cellular IP6 compared to that of HIV-1, while still maintaining IP6 sensitivity in vitro. Therefore, while we have shown that IP6 is not essential for HTLV-1 immature particle production and lattice formation, a potential role of IP6 or another polyanion in maturation and infectious particle production remains an open question. Further studies are therefore warranted to understand the role of IP6 in virus maturation and infectious particle production.

One outstanding question that remains is why IP6 has such a strong effect on CA assembly in vitro but is not required for immature particle assembly and release. One possible explanation for this may involve the role of NC in promoting HTLV-1 Gag oligomerization. Previous in vitro assembly studies of HTLV-1 CA helical tubes were done in the absence of IP6, but in the presence of NC and nucleic acid18. In the absence of nucleic acid binding to NC to promote assembly, HTLV-1 CA may require higher levels of IP6 to nucleate assembly.

The combination of high-resolution SPA and tomographic mapping of the HTLV-1 immature lattice provides an explanation for the striking heterogeneity observed in the immature lattice. The large variations seen in the local curvature from the tomographic analysis (Fig. 3c, e) along with previous reports of flattened regions of the lattice21 are likely a functional consequence of the HTLV-1 immature lattice having only intra-hexamer interactions in the CA-NTD and not the CA-CTD. The SPA flexible refinement depicts the CA-NTD acting as a hinge point, with the CA-CTD dimers being free to move independently of each other based upon on the local curvature of the lattice (Supplementary Movie 1). More discontinuity in the lattice, compared to that of other immature retroviral lattices9,14,43, is likely required in order to accommodate these large variations in local curvature in the absence of CA pentamers. However, understanding the varying distances between the viral membrane and CA lattice requires further investigation. A potential explanation for varying distance measurements could be a consequence of the unstructured regions of the HTLV-1 MA domain of Gag. While both the HTLV-1 and HIV-1 MA domain are similar in size (130 and 132 amino acids, respectively), the HIV-1 MA has a helical structure until residue K11444, while the helical structure of the HTLV-1 MA ends at residue Q9145. Therefore, the longer unstructured C-terminal tail of the HTLV-1 MA protein domain relative to the HIV-1 MA may accommodate both the exaggerated and heterogeneous distance between the viral membrane and the CA lattice.

Previous mutational and structural studies have implicated that the HTLV-1 immature Gag lattice is stabilized by the CA-NTD, in contrast from that of other retroviruses that are predominantly stabilized by the CA-CTD18,24,26,27. Our structural model provides insights that help to explain the results from previous chimeric Gag studies, which indicated that the HIV-1 CA-NTD could not functionally replace the HTLV-1 CA-NTD and the HTLV-1 CA-CTD could not replace the HIV-1 CA-CTD25. The observations support the conclusion that without strong intra-hexamer interactions from the HTLV-1 CA-NTD, the HTLV-1 CA-CTD can only form dimers and not progress to higher-ordered CA assemblies. Despite this, the HTLV-1 CA-CTD is not dispensable for immature particle production25 as demonstrated by our targeted mutagenesis of the CA-CTD dimer interface (Fig. 2d–j). Analysis of the HIV-1 Gag lattice implies that the lattice grows from Gag dimers46. If the HTLV-1 lattice is assembled in a similar manner, this would provide important evidence that the CA-CTD dimer interface is more important for initial lattice formation by Gag dimerization rather than stabilizing the lattice. However, more intensive investigation is needed to fully understand the role of the HTLV-1 CA-CTD in assembly of the HTLV-1 immature lattice, which will be aided by the high-resolution model generated of the CA-CTD dimer interface in the present study.

Comparative analysis between the immature and mature CA structures can provide important insights into the process of virus maturation. The organization of the HTLV-1 immature lattice, specifically the lack of a 6HB and the immature CA-NTD adopting a mature-like conformation, implies that HTLV-1 may undergo a distinct maturation process. The mature-like organization of the CA-NTD may be an indication that it undergoes little structural re-organization during maturation, which is in stark contrast to the large CA-NTD structural alterations during HIV-1 maturation. Some rearrangement of the HTLV-1 CA-NTD would be required as the immature NTD-NTD interactions would interfere with the NTD-CTD interactions observed in other mature lattices9,38,41,47. Additionally, the HTLV-1 immature CA-CTD dimer interface has a distinct orientation from that of the mature BLV CA-CTD dimer interface observed in the crystal structure38 (Supplementary Fig. 3g-i). It is important to note that the HIV-1 6HB is critical for stabilizing the immature lattice and is the target of maturation inhibitors11,48,49,50. In the absence of a 6HB, it is unclear what prevents the immature HTLV-1 CA-CTD dimer interface from rearranging into the conformation observed in the mature BLV CA crystal structure. Directly below the HTLV-1 CA-CTD density, a faint density is observed that likely corresponds to the NC protein (Supplementary Fig. 1d). Interactions between the HTLV-1 CA-CTD and NC or a slightly ordered NC arrangement may help to keep the CA-CTD in the observed immature conformation.

Recent tomographic analysis of immature HTLV-1 particles determined structures of the CA-NTD to 5.9 Å resolution and the CA-CTD to 6.2 Å resolution18. Furthermore, a structure of the CA-NTD was determined to 3.4 Å from in vitro assembled helical tubes, but the CA-CTD was unable to be resolved to high-resolution18. Importantly, our use of SPA with immature HTLV-1 particles allowed for an improved resolution to 3.4 Å globally, with local resolution of 3.2–3.4 Å in the CA-NTD and local resolution of 3.4–4 Å in the CA-CTD (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1a). This represents the highest resolution reported to date for the CA-CTD and helps provide a structural basis for how the flexibility results in either the curved or flattened lattice morphologies. The improved resolution in the CA-CTD has also confirmed the role for the CA-CTD in immature particle assembly, along with the identification of residues critical for stabilizing the dimer interface. Taken together, these observations advance our knowledge of the pleomorphic nature of HTLV-1 particle morphology as well as aid in revealing therapeutic targets.

Methods

Immature viral particle production and purification

An expression plasmid encoding the HTLV-1 Gag gene (HTLV-1 Gag pN3 vector) was co-transfected with an expression plasmid for the HTLV-1 envelope gene into HEK293T/17 cells (ATCC - CRL 3216) using GenJet Ver. II (SignaGen Laboratories, MD). The transfection ratio was at a 10:1 mass of the Gag:envelope expression plasmids. The supernatant was collected 48 h post-transfection, spun at 1000 RCF for 5 min., then passed through at 0.22 µm filter. The particles were purified following a previously described protocol14. Briefly, supernatant was pelleted over an 8% (v/v) Optiprep cushion in STE buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA). The sample was spun at 111,338 RCF for 100 min. in a 50.2 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter, CA). The resulting pellet was resuspended in STE and loaded over a 10, 20, 30% (v/v) OptiPrep gradient for 3 h at 191,986 RCF in a SW55 Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter, CA). A band between the 20 and 30% (v/v) steps in the gradient was extracted and pelleted with a 1 h spin at 151,693 RCF and resuspended STE.

Immature virus particle production, western blot, and quantification

To create the HTLV-1 CA-CTD site-directed mutants, mutations were engineered into the HTLV-1 Gag pN3 vector by using the Gibson Assembly® protocol (New England Biolabs, MA). Mutant or WT HTLV-1 or HIV-1 Gag expression plasmids were co-transfected with the corresponding HTLV-1 or HIV-1 envelope expression plasmids at a mass ratio of 10:1 (gag:env expression plasmids) into a single 10 cm plate of either WT HEK293T/17 (ATCC - CRL 3216), IPPK, or IPMK cells. For the IP6 depletion assay, a MINPP1 expression or empty vector was co-transfected with the Gag:Env expression plasmids. The IPPK and IPMK KO cells, along with the MINPP1 expression vector, were kindly provided by Dr. Eric O. Freed (NCI-Frederick). The supernatant was collected 48 h post transfection, spun at 1000 RCF for 5 min. and filtered through a 0.22 µm filter. Virus particles were pelleted over an 8% (v/v) OptiPrep cushion in STE buffer at 111,338 RCF for 100 min. in a 50.2Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter, CA). The pellet was resuspended in STE buffer, then pelleted once more at 16,000 RCF for 1 h and resuspended in 20 µL STE. The transfected HEK293T/17 cells were collected and lysed with CelLyticMTM (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) with the addition of a protease inhibitor cocktail (cOmpleteTM Proease Inhibitor Cocktail, Sigma-Aldrich, MO). The lysate was incubated at 4 °C on a rocking platform and then centrifuged for 30 min at 16,000 RCF. The supernatant and lysate were run on an SDS-PAGE gel for 45 min. and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for 1 h at 100 v. Membranes were blocked overnight with 5% milk (w/v) in TBST. Blots were incubated with 1:2000 anti-HTLV-1 p24 antibody (6G9, Santa Cruz) or anti-HIV-1 p24 antibody (24-4, Santa Cruz), washed 5x for 3 min. each in TBST, then incubated with 1:2000 anti-mouse IgG StarBrightTM Blue 700 (Bio-Rad, CA). Lysate loading was normalized to GAPDH by addition of 1:1000 anti-gapdh hFABTM rhodamine (Bio-Rad, CA). HTLV-1 p24 signal in the lysate and supernatant was quantified with Fiji ImageJ gel analysis. The supernatant signal was double normalized to the lysate p24 and GAPDH signal.

HTLV-1 CA purification

The HTLV-1 CA protein (Gag amino acids 132–349) was purified using the protocol previously described39. Mutations were engineered into the vector using the Gibson Assembly® protocol (New England Biolabs, MA). Briefly, transformed BL21 cells were grown overnight at 37 °C in ZY auto-induction media. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in lysis buffer (250 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, pH 8) and stored at −80 °C until used. The resuspended cells were lysed by the addition of 10 mg of lysozyme and incubated on ice for 30 min. The lysate was sonicated for three, 10-min cycles at 40% amplitude (QSONICA, Q500). The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 RCF for 30 min, and the supernatant was added to equilibrated NI-NTA beads (Ni Sepharose High Performance, Cytiva, MA). The lysate supernatant was incubated overnight at 4 °C on a rocking platform. Unbound lysate was allowed to flow through the Ni-NTA beads. The beads were washed with 30 mL of lysate buffer followed by 30 mL of wash buffer 2 (250 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 25 mM imidazole, pH 8). The bound protein was eluted by addition of 5 mL elution buffer (250 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 500 mM imidazole, pH 8). The eluted protein was dialyzed overnight at 4 °C in cleavage buffer (250 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 1 mM DTT, pH 8) and the 6xHis SUMO tag was cleaved by addition of house made Ulp1 protease. The cleaved protein was run over a Ni column (HisTrap HP 1 mL, Cytiva, MA) to separate the 6xHis SUMO tag from the HTLV-1 CA. Fractions containing the purified CA protein were concentrated to 10 mg/mL and flash frozen until use.

HTLV-1 CA in vitro assembly

Purified protein was diluted to 100 μM and dialyzed (PierceTM Slide A Lyzer ® Mini Dialysis Units, Thermo Fisher, MA) into assembly buffer (50 mM NaCl, 50 mM MES, pH 6.5) overnight at 4 °C. Following dialysis, different concentrations of polyanions were added (IP6, mellitic acid, dNTP, or sodium phosphate) to initiate assembly. The protein was incubated at room temperature for 2 h and then spun at 10,000 RCF for 10 min to separate the assembled CA from the soluble CA. For the SDS-PAGE analysis, an aliquot was taken prior to centrifugation to serve as the total input. The pellet was resuspended in fresh assembly buffer with the corresponding polyanion.

Negative stain transmission electron microscopy

Carbon support film on square copper grids (CF300-CU-50, Electron Microscopy Sciences) was glow discharged for 30 s at 10 mA, and 3 μL of fresh HTLV-1 CA assemblies were applied. The grids were incubated for 2 min, blotted, washed 3 times in 2% uranyl acetate, blotted, incubated for 2 min. in 2% uranyl acetate, and blotted once more. Grids were imaged at 120 keV in a FEI Tecnai Spirit Bio-Twin transmission electron microscope.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) preparation

Quantifoil® R 2/1 200 mesh TEM grids were glow-discharged for 30 s at 10 mA. Frozen grids were prepared in a Leica EM GP2 automatic plunge freezer with 3.5 µL of concentrated sample. The sample was blotted at a range of different times with Whatman 1 filter paper (CAT #1001-070 Cytiva, MA) and plunged into liquid ethane. Ice and sample quality were screened on a FEI TF30 transmission electron microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR).

HTLV-1 single particle analysis data collection and image reconstruction

Movies were collected at the National Cancer Institute Cryo-EM Facility at the Frederick National Laboratory on a Thermo Fisher Titan Krios and Gatan K2 camera (Supplementary Table 1). Movies were motion corrected and binned by 2 (1.32 Å/pixel) using RELION-4.0 implementation of MotionCor251. Contrast transfer function (CTF) information was determined using CTFFIND452. All processing was conducted using RELION-4.053,54 and RELION-5.055. See (Supplementary Fig. 2) for a detailed schematic of the processing pipeline. An initial subset of particles was picked from a randomly selected 50 micrographs. The extracted particles were subjected to 2D class averaging, and good classes were saved. The saved classes were used for Topaz auto-picking56, resulting in 2.5 million particles. Particles were extracted with a box size of 128 pixels, corresponding to 338 Å. The following particle list was aligned with C6 symmetry to an initial reference generated from the cryo-ET and subtomogram averaging procedure (Fig. 3g). Successive rounds of RELION-4.0 3D classification with image alignment resulted in a final particle set of 140,020. Two rounds of CTF correction were implemented in RELION-4.0 (anisotropic magnification, beamtilt, and per-particle defocus estimates), followed by 3D auto-refine. Next, two rounds of Bayesian polishing were conducted in RELION-4.0 along with new per-particle defocus estimates and a new 3D auto-refine. Finally, a 3D auto-refine in RELION-5.055 with blush regularization followed by a final Bayesian polishing step and per-particle defocus estimate resulted in the 3.4 Å reconstruction map. Finally, the map was locally sharpened using the highRes model from DeepEMhancer57.

Real-space refinement of HTLV-1 Gag CA model based upon the cryo-EM density map

A specialized cryo-EM real-space refinement protocol was developed for the present work (Supplementary Fig. 6). First, we derived de-novo structures of the HTLV-1 Gag131-344 (HTLV-1 CA1-214)58 using alphaColab59,60. The alphaColab predicted CA-NTD, and obtained CA-CTD dimer18 were docked separately into the cryo-EM density map (Supplementary Fig. 7a) using ChimeraX61. Then, a model containing a CA hexamer and its immediate neighbors was achieved by rigid body docking of the model derived in the previous step (Supplementary Fig. 7b). Later, the CA-N terminus, CA-C terminus, and flexible linker were regenerated by homology modeling using Rosetta (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d)62,63,64,65. Local rebuilding procedures were performed using CartesianSampler in Rosetta to improve the quality of the model fitted to the density. Next, the model was iteratively refined by applying FastRelax66,67,68 protocol to the residues with low local-cross correlation (LCC), and poor MolProbity69,70,71,72 score utilizing supervised and unsupervised protein refinement tools, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 7e). A neutralized-solvated system, containing 18 HTLV-1 CA monomers, ions, and water molecules, was achieved following the procedure described in Perilla et al.73. A symmetrical MDFF simulation, followed by minimization with conjugate gradient algorithm were performed using NAMD3.0.174,75.

A separate model without IP6 was further refined by docking three CA monomers into the three-fold hexamer interface of the HTLV-1 CA lattice. One round of Phenix Real Space Refine was performed, followed by manual inspection and adjustments in the UCSF ChimeraX61 plugin ISOLDE76. This was followed by a final round of Phenix Real Space Refine.

Fitting of the resulting models to the cryo-EM density was examined quantitatively by calculating the local cross correlation between the simulated density of the model and the cryo-EM density map, and separately by calculating the per-atom Q-score (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. 9).

Tomography data collection, tomogram reconstruction, and subtomogram averaging

Samples were mixed with 10 nm gold beads prior to plunge freezing. The tilt series were collected at the National Cancer Institute Cryo-EM Facility at the Frederick National Laboratory on a Titan Krios using a K3 camera with a pixel size of 1.42 Å (Supplementary Table 2). Frames were motion corrected using MotionCor251. Tomogram reconstruction was performed in IMOD77, and CTF corrected using outputs from CTFFIND452. Reconstructed tomograms were imported to Dynamo78, and hexamer positions were identified following the described protocol for HIV-1 Gag lattice reconstruction79. Briefly, viral particles were estimated using a dipole model, and a coordinate was placed every ~300 Å. An initial reference was generated directly from 4x binned extracted subtomograms (64 pixel, 363 Å3) using orientations based on the spherical model. Subtomograms from one tomogram were aligned to the reference, and the six-fold (C6) symmetry of the central hexamer was manually determined. The entire subtomogram set was refined against the symmetrized reference using C6 symmetry. Following alignment, hexamer positions were filtered per tomogram based on the cross-correlation value in the Dynamo table file. New hexamer positions were added using symmetry expansion based on the parameters of the lattice. Iterations of particle refinement, particle filtering, and symmetry expansion were conducted until there was no improvement in the particle locations. A custom MATLAB program was made to determine the principal local Gag curvatures and to determine the distance from the capsid layer to the membrane outer surface. Cross-correlation filtered coordinates were imported into RELION-4.054 for subtomogram averaging. Briefly, the imported coordinates were used to make an ab-initio model from 4x binned pseudo-subtomograms (64 pixel, 363 Å3) and used as a reference for an initial refinement. A 3D classification was performed with alignment, and the good classes were kept for refinement at 2x binning (128 pixels, 363 Å3) and finally 1x binning (256 pixels, 363 Å3).

Statistical analysis

Western blot quantification was performed by using Fiji ImageJ. Band intensity values were averaged, and the standard error of the mean was determined. Significance and p values were determined by using the calculated average and standard error of the mean using an unpaired two-sided t-test.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The cryo-EM maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) under accession codes EMD-48796 for the SPA reconstruction and EMD-48795 for the StA reconstruction. The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession codes 9N0W and 9N92 for the MDFF refined model with IP6 present. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code for analyzing local capsid curvature and capsid to membrane distances from subtomogram averaging has been uploaded to Zenodo [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17359858].

References

Yoshida, M., Miyoshi, I. & Hinuma, Y. Isolation and characterization of retrovirus from cell lines of human adult T-cell leukemia and its implication in the disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79, 2031–2035 (1982).

Popovic, M. et al. Isolation and transmission of human retrovirus (human T-cell leukemia virus). Science 219, 856–859 (1983).

Murphy, E. L. et al. Sexual transmission of human T-lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-I). Ann. Intern Med. 111, 555–560 (1989).

Kaplan, J. E. et al. The risk of development of HTLV-I-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis among persons infected with HTLV-I. J. Acquir Immune Defic. Syndr. 3, 1096–1101 (1990).

Zhang, W., Cao, S., Martin, J. L., Mueller, J. D. & Mansky, L. M. Morphology and ultrastructure of retrovirus particles. AIMS Biophys. 2, 343–369 (2015).

Gamble, T. R. et al. Structure of the carboxyl-terminal dimerization domain of the HIV-1 capsid protein. Science 278, 849–853 (1997).

Inlora, J., Collins, D. R., Trubin, M. E., Chung, J. Y. & Ono, A. Membrane binding and subcellular localization of retroviral Gag proteins are differentially regulated by MA interactions with phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate and RNA. mBio 5, e02202 (2014).

Kafaie, J., Song, R., Abrahamyan, L., Mouland, A. J. & Laughrea, M. Mapping of nucleocapsid residues important for HIV-1 genomic RNA dimerization and packaging. Virology 375, 592–610 (2008).

Qu, K. et al. Structure and architecture of immature and mature murine leukemia virus capsids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E11751–E11760 (2018).

Schur, F. K., Dick, R. A., Hagen, W. J., Vogt, V. M. & Briggs, J. A. The structure of immature virus-like Rous sarcoma virus gag particles reveals a structural role for the p10 domain in assembly. J. Virol. 89, 10294–10302 (2015).

Schur, F. K. et al. An atomic model of HIV-1 capsid-SP1 reveals structures regulating assembly and maturation. Science 353, 506–508 (2016).

Schur, F. K. et al. Structure of the immature HIV-1 capsid in intact virus particles at 8.8 A resolution. Nature 517, 505–508 (2015).

Khorasanizadeh, S., Campos-Olivas, R., Clark, C. A. & Summers, M. F. Sequence-specific 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift assignment and secondary structure of the HTLV-I capsid protein. J. Biomol. NMR 14, 199–200 (1999).

Talledge, N. et al. HIV-2 immature particle morphology provides insights into gag lattice stability and virus maturation. J. Mol. Biol. 435, 168143 (2023).

Dick, R. A. et al. Structures of immature EIAV Gag lattices reveal a conserved role for IP6 in lentivirus assembly. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008277 (2020).

Krebs, A. S. et al. Molecular architecture and conservation of an immature human endogenous retrovirus. Nat. Commun. 14, 5149 (2023).

Bester, S. M. et al. Structural and mechanistic bases for a potent HIV-1 capsid inhibitor. Science 370, 360–364 (2020).

Obr, M. et al. Distinct stabilization of the human T cell leukemia virus type 1 immature Gag lattice. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 32, 268–276 (2024).

Stacey, J. C. V. et al. The conserved HIV-1 spacer peptide 2 triggers matrix lattice maturation. Nature 640, 258–264 (2025).

Martin, J. L., Cao, S., Maldonado, J. O., Zhang, W. & Mansky, L. M. Distinct particle morphologies revealed through comparative parallel analyses of retrovirus-like particles. J. Virol. 90, 8074–8084 (2016).

Maldonado, J. O., Cao, S., Zhang, W., & Mansky, L. M. Distinct morphology of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1-like particles. Viruses 8, 132 (2016).

Accola, M. A., Strack, B. & Gottlinger, H. G. Efficient particle production by minimal Gag constructs which retain the carboxy-terminal domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 capsid-p2 and a late assembly domain. J. Virol. 74, 5395–5402 (2000).

Wagner, J. M. et al. Crystal structure of an HIV assembly and maturation switch. Elife 5, e17063 (2016).

Martin, J. L. et al. Critical role of the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 capsid N-terminal domain for gag-gag interactions and virus particle assembly. J. Virol. 92, e00333–18 (2018).

Martin, J. L. et al. Disparate contributions of human retrovirus capsid subdomains to gag-gag oligomerization, virus morphology, and particle biogenesis. J. Virol. 91, e00298–17 (2017).

Rayne, F., Bouamr, F., Lalanne, J. & Mamoun, R. Z. The NH2-terminal domain of the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 capsid protein is involved in particle formation. J. Virol. 75, 5277–5287 (2001).

Cornilescu, C. C., Bouamr, F., Yao, X., Carter, C. & Tjandra, N. Structural analysis of the N-terminal domain of the human T-cell leukemia virus capsid protein. J. Mol. Biol. 306, 783–797 (2001).

Mallery, D. L. et al. Cellular IP(6) levels limit HIV production while viruses that cannot efficiently package IP(6) are attenuated for infection and replication. Cell Rep. 29, 3983–3996.e3984 (2019).

Ricana, C. L., Lyddon, T. D., Dick, R. A. & Johnson, M. C. Primate lentiviruses require Inositol hexakisphosphate (IP6) or inositol pentakisphosphate (IP5) for the production of viral particles. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008646 (2020).

Dick, R. A. et al. Inositol phosphates are assembly co-factors for HIV-1. Nature 560, 509–512 (2018).

Mallery, D. L. et al. A stable immature lattice packages IP(6) for HIV capsid maturation. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe4716 (2021).

Mallery, D. L. et al. IP6 is an HIV pocket factor that prevents capsid collapse and promotes DNA synthesis. Elife 7, e35335 (2018).

Renner, N. et al. A lysine ring in HIV capsid pores coordinates IP6 to drive mature capsid assembly. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009164 (2021).

Christensen, D. E., Ganser-Pornillos, B. K., Johnson, J. S., Pornillos, O. & Sundquist, W. I. Reconstitution and visualization of HIV-1 capsid-dependent replication and integration in vitro. Science 370, eabc8420 (2020).

Biswas, B. et al. Essential functions of inositol hexakisphosphate (IP6) in murine leukemia virus replication. mBio 15, e0115824 (2024).

Punjani, A. & Fleet, D. J. 3DFlex: determining structure and motion of flexible proteins from cryo-EM. Nat. Methods 20, 860–870 (2023).

Pornillos, O., Ganser-Pornillos, B. K. & Yeager, M. Atomic-level modelling of the HIV capsid. Nature 469, 424–427 (2011).

Obal, G. et al. STRUCTURAL VIROLOGY. Conformational plasticity of a native retroviral capsid revealed by X-ray crystallography. Science 349, 95–98 (2015).

Yang, H., Arndt, W. G., Zhang, W. & Mansky, L. M. Determinants in the HTLV-1 capsid major homology region that are critical for virus particle assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 436, 168851 (2024).

Renner, N. et al. HIV-1 is dependent on its immature lattice to recruit IP6 for mature capsid assembly. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 30, 370–382 (2023).

Zhao, G. et al. Mature HIV-1 capsid structure by cryo-electron microscopy and all-atom molecular dynamics. Nature 497, 643–646 (2013).

Cao, S., Maldonado, J. O., Grigsby, I. F., Mansky, L. M. & Zhang, W. Analysis of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 particles by using cryo-electron tomography. J. Virol. 89, 2430–2435 (2015).

Briggs, J. A. et al. Structure and assembly of immature HIV. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 11090–11095 (2009).

Qu, K. et al. Maturation of the matrix and viral membrane of HIV-1. Science 373, 700–704 (2021).

Herrmann, D. et al. Structural insights into the mechanism of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 gag targeting to the plasma membrane for assembly. J. Mol. Biol. 433, 167161 (2021).

Tan, A., Pak, A. J., Morado, D. R., Voth, G. A., Briggs, J. A. G. Immature HIV-1 assembles from Gag dimers leaving partial hexamers at lattice edges as potential substrates for proteolytic maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2020054118 (2021).

Obr, M. et al. Structure of the mature Rous sarcoma virus lattice reveals a role for IP6 in the formation of the capsid hexamer. Nat. Commun. 12, 3226 (2021).

Mendonca, L. et al. CryoET structures of immature HIV Gag reveal six-helix bundle. Commun. Biol. 4, 481 (2021).

Purdy, M. D. et al. MicroED structures of HIV-1 Gag CTD-SP1 reveal binding interactions with the maturation inhibitor bevirimat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 13258–13263 (2018).

Sarkar, S. et al. Structural basis of HIV-1 maturation inhibitor binding and activity. Nat. Commun. 14, 1237 (2023).

Zheng, S. Q. et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017).

Rohou, A. & Grigorieff, N. CTFFIND4: fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 192, 216–221 (2015).

Kimanius, D., Dong, L., Sharov, G., Nakane, T. & Scheres, S. H. W. New tools for automated cryo-EM single-particle analysis in RELION-4.0. Biochem. J. 478, 4169–4185 (2021).

Zivanov, J. et al. A Bayesian approach to single-particle electron cryo-tomography in RELION-4.0. Elife 11, e83724 (2022).

Kimanius, D. et al. Data-driven regularization lowers the size barrier of cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 21, 1216–1221 (2024).

Bepler, T., Kelley, K., Noble, A. J. & Berger, B. Topaz-Denoise: general deep denoising models for cryoEM and cryoET. Nat. Commun. 11, 5208 (2020).

Sanchez-Garcia, R. et al. DeepEMhancer: a deep learning solution for cryo-EM volume post-processing. Commun. Biol. 4, 874 (2021).

Rayne, F., Kajava, A. V., Lalanne, J. & Mamoun, R. Z. In vivo homodimerisation of HTLV-1 Gag and MA gives clues to the retroviral capsid and TM envelope protein arrangement. J. Mol. Biol. 343, 903–916 (2004).

Mirdita, M. et al. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 19, 679–682 (2022).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Meng, E. C. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 32, e4792 (2023).

Rohl, C. A., Strauss, C. E., Misura, K. M. & Baker, D. Protein structure prediction using Rosetta. Methods Enzymol. 383, 66–93 (2004).

Loquet, A. et al. Atomic model of the type III secretion system needle. Nature 486, 276–279 (2012).

Demers, J. P. et al. High-resolution structure of the Shigella type-III secretion needle by solid-state NMR and cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Commun. 5, 4976 (2014).

Fleishman, S. J. et al. RosettaScripts: a scripting language interface to the Rosetta macromolecular modeling suite. PLoS ONE 6, e20161 (2011).

Tyka, M. D. et al. Alternate states of proteins revealed by detailed energy landscape mapping. J. Mol. Biol. 405, 607–618 (2011).

Khatib, F. et al. Algorithm discovery by protein folding game players. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 18949–18953 (2011).

Maguire, J. B. et al. Perturbing the energy landscape for improved packing during computational protein design. Proteins 89, 436–449 (2021).

Davis, I. W. et al. MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W375–W383 (2007).

Davis, I. W., Murray, L. W., Richardson, J. S. & Richardson, D. C. MOLPROBITY: structure validation and all-atom contact analysis for nucleic acids and their complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W615–W619 (2004).

Chen, V. B. et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 12–21 (2010).

Williams, C. J. et al. MolProbity: more and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 27, 293–315 (2018).

Perilla, J. R. et al. CryoEM structure refinement by integrating NMR chemical shifts with molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 121, 3853–3863 (2017).

Phillips, J. C. et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802 (2005).

Phillips, J. C. et al. Scalable molecular dynamics on CPU and GPU architectures with NAMD. J. Chem. Phys. 153, 044130 (2020).

Croll, T. I. ISOLDE: a physically realistic environment for model building into low-resolution electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr. D. Struct. Biol. 74, 519–530 (2018).

Kremer, J. R., Mastronarde, D. N. & McIntosh, J. R. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J. Struct. Biol. 116, 71–76 (1996).

Castano-Diez, D., Kudryashev, M., Arheit, M. & Stahlberg, H. Dynamo: a flexible, user-friendly development tool for subtomogram averaging of cryo-EM data in high-performance computing environments. J. Struct. Biol. 178, 139–151 (2012).

Scaramuzza, S. & Castano-Diez, D. Step-by-step guide to efficient subtomogram averaging of virus-like particles with Dynamo. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001318 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH grants R01 GM151775 and R21 DE032878 (to L.M.M. and W.Z.) and the University of Minnesota Masonic Cancer Center (to L.M.M.). W.G.A. was supported by NIH grants T32 AI083196 (Minnesota Training Program in Virology) and F31 AI184673. A portion of the TEM analysis was conducted at the Characterization Facility, College of Science & Engineering, University of Minnesota, which receives partial support from NSF through the MRSEC (Award Number DMR-2011401) and the NNCI (Award Number ECCS-2025124) programs. This research was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute Cryo-EM Facility at the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research under contract 75N91019D00024. We thank Thomas Klose at the Purdue University Midwest Cryo-EM Consortium (U24GM116789) for data collection of the HTLV-1 CA A94K crystal sheets. N.T. was supported by NIH grants T32DA007097 and F32AI150351. N.T. was also supported by American Cancer Society Postdoctoral Fellowship PF-21-189-01-MPC (N.T.). Work in the J.R.P. lab was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01AI178846 (J.R.P.) and U54AI170791 (J.R.P.). We also thank Juan S. Rey and Sruthi Sudhakar for their critical review and comments of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This work was conceptualized by W.G.A., W.Z., and L.M.M. The immature HTLV-1 particles for single particle analysis and subtomogram averaging were prepared by N.T. and W.G.A. Single particle and tomography image processing was conducted by W.G.A. and W.Z. The program for determining lattice curvature and distance measurements was written by G.Y. Modeling, building, refinement, and interpretation were conducted by A.R., J.R.P., B.C., and W.G.A. Molecular dynamics was run and analyzed by A.R. and J.R.P. HTLV-1 mutagenesis and immature particle production were conducted by W.G.A. and H.Y. IP6 assembly assay and negative stain imaging were conducted by W.G.A. The manuscript draft was written by W.G.A., W.Z., and L.M.M. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Z. Hong Zhou, who co-reviewed with Xian Xia, Stefan Oliver, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arndt, W.G., Ramezani, A., Talledge, N. et al. High-resolution analysis of the human T-cell leukemia virus capsid protein reveals insights into immature particle morphology. Nat Commun 17, 444 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67129-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67129-1