Abstract

On 26th September 2022, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission actively impacted the small moon Dimorphos of the Didymos-Dimorphos binary asteroid system. The impact caused a variation of about 33 minutes in its orbital period around Didymos and demonstrated the feasibility of moving an asteroid in space. As part of an international observing campaign devoted to its physical characterization, in this work we investigate the visible spectral properties of the Didymos-Dimorphos system soon after the impact. Rotationally-resolved spectra have been obtained 25 days after the impact and two months later. Geometric investigations have been performed to look for the source region corresponding to each spectrum. Here we show an overall agreement with pre-impact spectra and S-type classification despite subtle variations emerging, possibly correlated with mutual events. Furthermore a small long term color evolution from October to December spectra tentatively interpreted as related to dust cloud grain size effects or alternatively attributed to an uneven deposition of freshly exposed material from the impact on Didymos.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Didymos-Dimorphos system is a Potentially Hazardous Asteroid and the target of the NASA/Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART)1 and ESA/HERA2 space missions as part of an international planetary defense collaboration (Asteroid Impact & Deflection Assessment). The NASA DART successfully impacted the small moon Dimorphos of the Didymos-Dimorphos binary system on 26th September 2022, causing a decrease of its orbital period around Didymos of 33 ± 1 min.3. The spectral properties of this system are still debated, although the coordinated observing campaigns during the last apparitions in 2003, 2019, and 2021 have improved our knowledge of the system4,5,6,7.

(65803) Didymos was originally classified as an Xk-type asteroid4, based on visible spectroscopy. Some years later, de Leon et al.5,6 revised the classification using NIR data and classified it as an S-type, then confirmed by Dunn et al.7, who also discussed its consistency with ordinary chondrites and an affinity with L/LL-type meteorites. Further investigations in the NIR reported a 1.9 μm band shallower than the typical silicate band8, which deserves additional investigation. Visible observations at different rotational phases prior to the DART impact have provided evidence of a small spectral variability9. Those have been tentatively interpreted as possible heterogeneous surface composition of Didymos, even though different observational conditions might affect those preliminary results. Nonetheless, a complete pre-impact surface coverage investigation is missing.

Although a different composition of Dimorphos with respect to the primary is not expected from current understanding of the formation of small binary systems10, small variations might, in principle, alter the spectral characterization of the system when mutual events occur9. However, assuming a similar albedo and composition, the contribution of Dimorphos before the impact by DART was estimated as only 4-5% of the reflected light from the system11, so the overall pre-impact spectrum should be dominated by light from Didymos alone.

Nevertheless, the rotationally resolved spectroscopy is a powerful tool to investigate possible variegations and inhomogeneities throughout the surface in the case of a single non-active object (e.g., ref. 12). Unlike usual spectroscopy, based on the analysis of a single spectrum, rotationally resolved spectroscopy involves collecting multiple spectra over a time span that covers the entire rotation period of the target. This approach makes it possible to monitor any change in the spectral properties as the object rotates, potentially revealing surface heterogeneities. Similarly, in the case of a binary system as the one discussed here, it is a valuable method even though it is complicated by the instantaneous geometry of the binary system, in particular, the mutual events that should be taken into account, and, in this case, by the presence of a well-recognized ejecta cloud in post-impact data 13,14,15.

In this work, we investigate rotationally resolved spectra of Didymos and Dimorphos system starting from about one month up to three months after the DART impact, which result mainly consistent with pre-impact spectra but highlighting subtle spectral variations and a small long-term color evolution from October to December. Here we show that the subtle small term variations are possibly correlated with mutual events and that the long-term color variation could be interpreted as related to the evolution of the dust cloud and to grain size effects or alternatively to an uneven deposition of freshly exposed material from the impact on Didymos.

Results

As part of a wide international observing campaign to monitor the system prior and after the DART impact, we performed rotationally resolved observations of Didymos in the visible range from 500 to 900 nm, using the 1.80-m telescope located in Asiago (VI), Italy, on 18th October 2022, less than one month after the impact, and in the nights of 26th and 27th December 2022. Additionally, we observed Didymos in the visible spectral range using the Large Binocular Telescope (LBT) situated on Mt. Graham in southeastern Arizona on 18th October 2022 with the MODS instrument. Furthermore, three spectra acquired at 10.4-m Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC) obtained on 19th October 2022 are included in the analysis. All the observational details for the 23 spectra are reported in Table 1.

With this observing strategy, during the 1st night in Asiago, we covered almost one (1.65 h = 73%) rotational period of Didymos (2.26 h) and during the first observing night in December, we covered more than two rotations (5.43 h = 2 rotations + 0.9 h).

Because spectra were acquired at different epochs with relatively short exposure times, it was possible to combine the instantaneous geometry of the system to derive mutual events and surface coverage map for each spectrum.

The data have been acquired orienting the slit along the parallactic angle to reduce the effects of the differential atmospheric refraction that is important when observing targets at high zenith distances. The data have been reduced using the IRAF astronomical package following standard reduction procedures as described in “Methods”.

The six spectra obtained in October (Fig. 1), covering almost one full rotation of the primary, despite being slightly noisy due to low altitude of the objects during the observations, are highly compatible with each other and do not show a strong variation.

The eleven spectra acquired on 26th December night (Fig. 2) covering more than two full rotations of the primary and the additional two spectra obtained in the subsequent night also are in complete agreement with October data.

Overall, the 23 spectra acquired are all compatible with the pre-impact one 6 and confirm the S-type taxonomic classification following Bus-Binzel classes16 both in October and in December.

Spectra independently obtained on 18th October UT 11:40 at LBT and on 19th October at UT 5:09 at the 10.4-m GTC, located in the island of La Palma (Spain) (see “Methods” for details), are in great accordance with our spectra (see Fig. 3).

Didymos-Dimorphos spectra acquired in October, December are compared with GTC, LBT, and pre-impact spectrum6. Mean S-type spectrum is also reported.

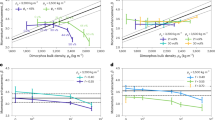

We calculated the spectral slopes of the reported spectra, considering the reflectance in the range 600 and 700 nm. Spectral slope values are reported in Table 1 and in Fig. 4 for each spectrum. Errors in the spectra slopes (Table 1 and Fig. 4) are the computational errors associated to the fitting least squares method.

a Spectral slopes with computational errors associated to the fitting least squares method for each spectrum. Orange dashed lines indicate epochs when mutual events occur (essentially SO/SE). The spectra are temporally distributed from October to December along the x-axis. b Spectral slopes with associated errors as a function of time for October dataset. c Spectral slopes with associated errors as a function of time for December dataset.

As visible in Fig. 4 a subtle variation in spectral slope (see also values in Table 1) is tentatively identified. As reported also in Polishook et al.17, we must recall that spectral slopes can change due to observational circumstances: the airmass of the target, the solar analog star used, the phase angle, weather conditions, and parallactic angle. We carefully tried to get rid of any of such variations in the observations whenever possible, for example trying to observe the solar analog at a very close angular distance from the Didymos system and aligning the slit along the parallactic angle.

Being interested in the rotationally resolved spectroscopy, obviously it was not possible to compare spectra acquired at the same airmass (as done by ref. 17). However, the data have been carefully corrected for possible extinction effects. Possible contribution due to the phase angle is presented in the discussion below. Our analysis is done under the assumption, based on the observational cautions adopted and the validation checks performed, that these spectral slopes represent a real physical behavior.

In October, the calculated slope values range from 3.6%/1000 Å to 9.1%/1000 Å, while in December they range from 8.8%/1000 Å to 17.0%/1000 Å (Table 1). Despite being overall compatible within the errors, the value of the spectral slopes tentatively show a subtle reddening from October to December (Fig.4).

We calculated the mutual events at the epoch of the observations by using the most up-to-date post-impact orbital solution18. The occurrence and the type of mutual events is reported in the last column of Table 1 as SO for secondary occultation (Dimorphos visually occulted by Didymos) and SE for secondary eclipse (Dimorphos in the shadow of Didymos).

Secondary eclipse/occultations events occur during both October and December observations, while no primary eclipses (PE: Dimorphos casts a shadow on Didymos) nor primary occulations (PO: part of Didymos’ disk is occulted by Dimorphos) occur during our observing times despite GTC observations fall very close to a PE occurrence.

In Fig. 4A the orange dashed vertical lines highlight the observations occurring during mutual events. Those are further specified in Fig. 4B, C, where the spectral slopes are reported as a function of time and the type and duration of each mutual event is highlighted as a coloured shaded region.

As visible in Fig. 4B, the spectral slopes show the lowest values (3.57%/1000 Å and 4.66%/1000 Å) for observations 1 and 2 (see Table 1), which fall within a total and partial SE, respectively (meaning that Dimorphos, which was at this stage still surrounded by its ejecta cloud, is in the shadow of Didymos). Interestingly in Fig. 4C the spectral slopes corresponding to observations 17, 18, and 19 acquired in December within a SO/SE event also show relatively low values (8.81%/1000 Å and 11.23%/1000 Å) with respect to previous and subsequent observations not falling within mutual events.

Datapoint’s horizontal extension given by the exposure time. Primary and secondary eclipses and occultations are indicated as coloured bands as described in the legend.

To further investigate the subtle variations observed in spectral slopes and identify the corresponding regions for each spectrum on the surface of Didymos, the geometry of the binary system for each spectral observation has been inspected using the latest NASA/DART Spice Kernel (JPL orbit solution 542).

In case of no mutual events, the two bodies are visually separated, thus in principle they both contribute to the observed reflectance, falling within the field of view (FOV). However, variable portions of the surfaces of the two bodies are instantaneously illuminated and observable. Thus, spectral variations might theoretically be related with local surface heterogeneity in the covered regions.

In the pre-impact phase, it is expected that the contribute from Dimorphos to the spectrum is negligible since the surface ratio between Dimorphos and Didymos is 0.0511 suggesting that any variation in Dimorphos spectrum should be almost insignificant compared to the light reflected from Didymos17.

In the post-impact phase the ejecta cloud has been found to be the main contribution (60–70%) to the post-impact system in the first 40 h17. The system has been largely investigated during the impact and in the following period to monitor the development and evolution of the dust cloud, being persistent for months, using photometry in the visible spectral range13,19.

About one week after the impact, a second tail has been identified14, possibly due to an impact by a large grain. This tail has a different direction with respect to the primary tail, making the dust environment around the system non-uniform, as shown by ground-based14 and space-based measurements14.

The evolution of the ejecta orbit in the system has shown to be very complex (i.e., ref. 14), and while at early stages after the release, the particles distribution would be more homogeneous, the solar radiation pressure is expected to further spread the particles forming substructures.

Mid October corresponds to nearly three weeks after the NASA/DART impact and the presence of the dust emitted by Dimorphos was very high14 and probably not uniformly distributed around the binary system, this ejecta cloud could in principle influence the spectra behaviour, so the complex dust cloud generated by the DART impact and distributed around the system must be considered in analyzing the spectra obtained.

Taking into account the complexity of the post-impact system, it is still important to perform a detailed geometrical investigation and retrieve the source regions corresponding to the spectra in order to study possible surface heterogeneity contributions. We searched essentially for possible heterogeneity on Didymos surface that could be discernible from the observed spectra. Nonetheless, we investigated the spectra source regions also on Dimorphos surface for the sake of completeness. In particular, we wanted to check also a possible relative contribution from the DART impact site on Dimorphos surface, which could in principle, reveal fresh and diverse material.

For the geometric analysis, we considered the following parameters: the phase angle of both bodies, the sub-Earth latitude (also called aspect angle) and longitude and the sub-solar point on both Didymos and Dimorphos surfaces for each observing epoch. Using those parameters, we estimated the illuminated and observable portion of the surface of both bodies, assumed to be spherical, thus determining the surface coverage corresponding to each epoch (see “Methods” for details of computation and Supplementary Table 1 for summary of geometric parameters).

Two examples of surface coverage maps for both Didymos (upper panels) and Dimorphos (lower panels) are reported in Figs. 5 and 6 for October and December, respectively. The aspect angle changes significantly from negative values in October to positive values in December (see Supplementary Table 1). This occurrence, combined with the sub-solar latitudes, indicates that mostly the southern hemispheres and the south poles of both Didymos and Dimorphos are visible and illuminated throughout October observations (see Fig. 5), while in December the observations mostly cover the northern hemispheres of the binary system including their north poles (see Fig. 6). Due to the fast rotation of the primary body (2.26 h period), its surface longitudinal coverage is almost complete both in October and in December observing periods.

a Didymos surface coverage maps for several spectra acquired in October. The illuminated and observable surface area at the acquisition time of each spectrum is filled with the same color used for the spectrum (see Fig. 1 for the spectra). See “Methods” section for details of the computation. Mostly Didymos southern hemisphere is observable in October due to the negative value of the aspect angle, while the longitudinal surface coverage is almost complete. b Dimorphos surface coverage maps for spectra #3, #4, #5, #6 (Table 1) when Dimorphos is not eclipsed or occulted. Dimorphos southern hemisphere is also observable in October dataset, while longitudinal coverage includes mostly west longitudes, while DART mission impact site on Dimorphos is indicated with an empty red circle at 90E longitude.

a Didymos surface coverage maps for all the spectra acquired in December. The illuminated and observable surface area at the acquisition time of each spectrum is filled with the same color used for the spectrum (see Fig. 2 for the corresponding spectra). See “Methods” section for details of the computation. b Dimorphos surface coverage maps for spectra from #11 to #16 and from #20 to #23 (Table 1) when Dimorphos is not eclipsed or occulted.

Dimorphos surface coverage maps are shown only for the epochs when it is not eclipsed or occulted. Dimorphos longitudinal coverage in October includes mostly west longitudes, while the DART mission impact site is located at about 90°E longitude based on the values reported by Daly et al.20 and indicated as an empty red circle on the maps.

Dimorphos slower rotation (11 h 22 min post impact3) is responsible for the slower changes in its longitudinal coverage (see Figs. 5B and 6B).

Didymos and Dimorphos surface cylindrical projection maps have been taken from shapeviewer software21 for visualization and comparison with the surface coverage maps.

Mostly Didymos’ and Dimorphos’ northern hemispheres are observable in December due to the positive value of the aspect angle. Didymos longitudinal coverage is highly complete, covering more than two full rotations of the body, while Dimorphos longitudinal coverage is almost complete despite its slower rotation. DART mission impact site on Dimorphos is indicated with an empty red circle at 90E longitude.

Discussion

We observe an overall good agreement among spectral observations acquired on 18th October, about 25 days after the DART impact on Dimorphos and spectra acquired about two months later in December 2022.

The good match also with independent observations acquired at LBT and GTC telescopes in the same period (mid-October) strongly supports our measurements.

As reported in Results, we computed spectral slopes in the wavelength range 600–700 nm for all the reported spectra and although they are all in agreement within the errors, we notice subtle variations that, after taking into account the several possible observational effects cited above, we are confident in considering them real.

If we exclude the observations occurring during mutual events, the average October slope is 9.82%/1000 Å, while average December slope results 13.94%/1000 Å.

As discussed above, October observations cover mostly southern hemispheres of both bodies, while December spectra are pointing mostly to northern hemispheres. Therefore, we cannot exclude that the observed small spectral variations among the two periods might be due to latitudinal compositional heterogeneity that could be a pre-impact property of Didymos or due to an uneven post-impact deposition of ejecta on its surface.

As an alternative, this behavior could instead suggest a long-term evolution of the ejecta cloud around Dimorphos, becoming slightly redder on a monthly basis since the smaller dust particles move away from the system, leaving the larger and redder ones15 probably not uniformly distributed around the binary system.

The ejecta are shown to be apparently blue just after the impact17 and to become redder after October. The change in the photometric color is explained with the release and detection of finer grains immediately after the impact15. The tail is made of a continuously developing size distribution of grains from finer to larger, where the finer ones are faster dispersed during the early stages of the ejection on timescales of hours or days15. Coarser grains can survive longer, i.e., for weeks and months after the impact, and so they can be observable around the system at the time of our measurements.

Additionally, we also notice very small variations occurring within mutual events, in particular secondary eclipses. Average October slope value within SE is 4.12%/1000 Å, about 5%/1000 Å lower than the average outside mutual events. Similarly, the average December slope within SE is 9.64%/1000 Å, about 4%/1000 Å lower than average December slope outside mutual events.

The repeated occurrence of this behavior both in October and in December seems to support the physical nature of this variation. This result might indicate that the occurrence of secondary eclipses, hiding Dimorphos and part of its ejecta cloud behind Didymos or in its shadow, can cause small variations in the visible spectral observations.

In order to further investigate the possible causes of the observed small differences in the spectral slopes, we compared the surface coverage maps for individual spectra within and outside mutual events to search for possible correlations.

For example spectrum #2 and the LBT spectrum have slightly different slopes (see Table 1), but they have very compatible surface coverage of the primary as visible in Fig. 7A. The two surface coverages differ only for the more extended area of AF784960 (spectrum #2) due to a longer exposure time. However, the major geometrical difference among these two observations is that spectrum #2 occurs during a secondary eclipse, while LBT spectrum doesn’t. This means that LBT spectrum also includes Dimorphos with mainly east longitudes coverage, including also the DART impact site location.

a Didymos surface coverage comparison between spectrum # 2 and LBT spectrum (Table 1). Despite the time difference of about 9 h among those two spectra, the surface coverages are almost identical apart from the more extended coverage of AF784960 (Table 1) due to longer exposure time. The major geometrical difference among these two observations is that AF784960 occurs during a secondary eclipse, while LBT spectrum doesn’t. b Dimorphos surface coverage for LBT spectrum.

Similarly, Didymos surface coverage of GTC observation (Fig. 8A) is very similar to that of AF784959 (spectrum #1, see Fig. 5A), which, however occurs during SE while GTC doesn’t. They again have slightly different spectral slopes. In this case Dimorphos east longitudes are observed in GTC data (Fig. 8B).

a Didymos surface coverage corresponding to GTC1, GTC2 and GTC3 (Table 1) observations. It partially corresponds to AF784959 coverage (see Fig. 5A), but again they differ since AF784959 occurs during a secondary eclipse while GTC1, GTC2, and GTC3 don’t. b Dimorphos surface coverage maps corresponding to GTC1-3.

Therefore, the observed variations in spectral slope specifically between these two couple of epochs do not seem to be related to any type of longitudinal heterogeneities on the covered primary surface but might rather be tentatively associated with Dimorphos and its ejecta cloud partially hiding in shadow for spectrum #1 and #2. This would, in turn, indicate that in October Dimorphos and/or its ejecta cloud could be the responsible of a slightly higher slope. As we do not expect such a strong influence by Dimorphos surface alone, we believe that this could be rather due to the dust cloud present around it.

As reported above, also December mutual events spectra appear slightly flatter than the average but still steeper than October mutual event spectra. In this case we do not have additional independent observations for direct surface coverage comparison. Nonetheless, we compared Didymos surface coverage during October SE with that of December SE (Fig. 9).

AF800551 (spectrum #17) covers almost the same longitudinal area of October mutual events spectra (spectra #1,#2) despite showing a higher spectral slope (see Table 1), while AF800552 and AF800553 (spectra #18, #19) cover mostly western longitudes on Didymos surface. North-south pole coverage differences remain between October and December. Therefore, we tentatively interpreted the relative drop in spectral slope both in October and in December as due to the mutual events, while the higher absolute value in December as possibly related with a compositional variegation of the poles being the north pole potentially redder than the south. We cannot exclude that this latitudinal surface heterogeneity could be connected with uneven deposition of freshly exposed material from the impact.

The impact site is located on the unilluminated and not visible surface portion of Dimorphos during all October observations with the exception of the LBT spectrum, while it becomes observable in many of December observations.

We also considered possible phase reddening effects. The October data were collected at a phase angle of 76 deg, whereas the December data were collected at 17 deg (see Supplementary Table 1 for phase angle values for each spectrum), therefore, we should expect rather redder spectra in October than in December. The general cause of phase reddening is still under investigation, but microscale structures at the microns scales could play an important role (e.g., Schroeder et al.22).

Although phase reddening is usually observed in asteroids of various taxonomic classifications (e.g., ref. 23), several investigations show that typical phase reddening for S-type asteroids is very small (0.01%/1000 Å/deg)24. Based on this estimate, we could expect on our spectra a reddening due to phase angle of about 0.59%/1000 Å, considering the difference in phase angle of the observations between October and December. This is below the long-term variation that we observe. So we suspect that the geometrical and/or evolutionary effects are in such case stronger than any possible phase reddening effect.

Additionally, none of the existing studies report a clear evidence of phase reddening effects on Didymos system (refs. 9,17).

Ieva et al.9 in their Table 1. Two report pre-impact values of spectral slope ranging from 4.4%/1000 Å to 20.0 %/1000 Å, which are computed in the 500–700 nm spectral range and on spectra normalized at 550 nm. Despite not being directly comparable, the measured values are highly compatible with our measurements. They tentatively interpreted the small variations as possibly related to local heterogeneities, although a detailed geometrical study is missing. Interestingly, looking at their Fig. 3, it emerges a similarity with the behavior of our measurements with respect to mutual events.

In spite of the mutual events and the small variations we found among the spectra, they all confirm the S-type taxonomic classification of the whole binary system in agreement with the standard binary system formation model.

In Lin et al.19, the principal component index technique is used to infer the taxonomic classification of the system. Although the silicate nature of Didymos-Dimorphos is confirmed, they reported similarities with S-complex, as well as C-complex, just after the impact, which is likely to be the result of contamination with ejecta due to the impact.

Photometric measurements were also used to confirm the classification as an S-type asteroid of the Didymos-Dimorphos system15,19, despite the temporal variations immediately after the DART impact19.

In conclusion, our findings do support the S-type classification and confirm an overall agreement with pre-impact spectra despite subtle variations emerged, possibly correlated with mutual events, together with a small long-term dust cloud color evolution probably related to grain size effects. As an alternative, the small variations found between the north and south pole could be tentatively attributed to locally different deposition of freshly exposed material from the impact.

The ESA Hera mission2 will investigate in detail the Didymos system in 2027, including its compositional properties with its hyperspectral imager (Hyperscout-H) onboard the main spacecraft and its visible-near-infrared imager onboard the Milani Cubesats (Aspect). Although no small dust from the DART impact is expected to be still around, being removed through solar radiation pressure, the measurements by Hera will allow checking our conclusion and determining whether some original or impact-induced compositional heterogeneity exist on Didymos and Dimorphos and/or between the two components, which could raise new questions for binary formation models.

Methods

Observations and data reduction

A total of 19 visible spectra of (65803) Didymos presented in this work have been taken on 18 October 2022 and on 26–27 December 2022 at the 1.80 m Copernico Telescope of the Asiago Observatory, Italy. One spectrum acquired on 18 October 2022 from the LBT in Arizona and three spectra acquired on 19 October 2022 from the GTC on the Canary Islands are also reported for comparison.

On 18th October, we covered 73% of the full rotation of the primary (2.26 h), while on 26th December, we covered almost 2,5 full rotational periods, allowing the investigation of possible surface composition variations within the rotation.

The Copernico Telescope is equipped with Asiago Faint Object Spectrograph and Camera (AFOSC), a long-slit with a 134 micron aperture (corresponding to 1.69 arcsec) and a Volume Phase Holographic Grisms (VPH6) of 285 lines/mm that yields a dispersion of 3.5 Å/pixel with low resolution, R = 500, in the spectral range 0.5–0.9 micron. The images exposure time ranges from 720 to 1800 s, depending on the object magnitude (see Table 1).

The spectra have been reduced using the standard Image Reduction and Analysis Facility (IRAF) routine26.

The images are trimmed, bias subtracted, flat field divided and then calibrated in wavelength using the appropriate lamp (HgCd). Finally, we proceed with the extraction of the spectra and the atmospheric extinction correction. Each spectrum is then divided by the appropriate solar analogue taken during the same night with as much as possible similar airmass. The solar analog observed both in October and December has been SA 98–978. We have applied a median filter at 3 sigma, with a box of 100 pixel, to remove the cosmic rays and the spurious features. The spectra are normalized to unity at 600 nm. Normalization of the spectra was performed through linear regression. This is an easy way to retrieve a most accurate measure of the actual flux collected at the designed wavelength.

LBT spectrum (spectrum # 7 in Table 1) was acquired on 2022-10-18 using the MODS instrument, which is composed by MODS1 and MODS2, a pair of low- to medium-resolution Multi-Object Double CCD Spectrographs/Imagers designed for the twin 8.4-m diameter mirror LBT on Mt. Graham in southeastern Arizona. Dual prisms spectroscopy mode was employed for low-resolution (R = 500–150) spectra with longslit 1.2”. Each MODS works with two different channels, the blue and the red channel, covering the full range 320–1050 nm. The MODS science detectors are 3K × 8K monolithic E2V CCDs; blue-coated standard silicon on the blue channel and extended-red coated 40-micron deep depletion silicon on the red channel. Non-sidereal mode was set to accurately follow the target across the night. The spectra have been reduced following standard spectroscopic reduction procedures using the Spectroscopic Interactive Pipeline and Graphical Interface25 provided by LBT team. SA98-978 analog star was observed the same night at a similar airmass of Didymos on both channels and used to remove the solar contribution from the spectrum. The blue and red portion of the spectrum were therefore divided by the corresponding analogue spectra and then matched together in a single spectrum covering the full range. Since the overlapping region was around 550 nm we decided to normalize the final spectrum at 600 nm, together with all the other spectra presented.

Spectra #8, #9, and #10 in Table 1 were obtained on 2022-10-19 at the 10.4-m GTC, using the OSIRIS camera-spectrograph. We used the 1.2 arcseconds slit and the R300R grism, covering a wavelength range from 420 to 920 nm with a dispersion of 7.74 Å/pixel. Three spectra of 180 s of exposure time each were obtained, with an offset of 10 arcseconds in the slit direction between them. We also observed one solar analog (SA98-978) at an airmass similar to that of the asteroid. Data reduction was done using standard procedures. Images were bias and flat-field corrected. Sky background was subtracted and 1 d spectra were extracted. Wavelength calibration was done using Xe+Ne+HgAr lamps. This procedure was applied to the spectra of the asteroid and the star. We divided the asteroid’s individual spectra by the spectrum of the solar analog, and the resulting ratios were normalized to unity at 600 nm.

The data have been acquired orienting the slit along the parallactic angle to reduce the effects of the differential atmospheric refraction that is important when observing targets at high zenith distances.

The spectra slopes (Table 1) have been calculated in the spectral range 6000–7000 Å using a least squares method with its associated errors.

Geometric analysis

To investigate for possible Didymos surface heterogeneities or for a possible influence of a Dimorphos different composition on the spectral appearance, we computed the instantaneous geometry of the binary system for each spectral observation using the post-impact orbital solution provided by Scheirich, P. et al.18 and the NASA ancillary system SPICE and its tools (https://naif.jpl.nasa.gov/naif/index.html). We used in particular the leapseconds kernel (naif0012.tls), the planet ephemerides kernel (de432s.bsp), the planetary constants kernel (pck00010.tpc), Didymos and Dimorphos frame kernels (didymos_system_006.tf, dimorphos_fixed.tf), Didymos-Dimorphos ephemeris kernels (didymos_barycenter_s205_v01.bsp, didymos_system_s527_v01.bsp, dimorphos_s542.bsp), and Didymos-Dimorphos constants kernels (didymos_system_14.tpc, dimorphos_s542-preimp.tpc, and dimorphos_s523-postimp.tpc) available at the link above.

All geometric parameters are reported in Supplementary Table 1. We also determined the possible occurrence of mutual events at the epochs of our observations (see Table 1) based on the latest post-impact orbital solution. Projection maps have been realized using the open source Python programming language (Python Software Foundation 2024) (https://www.python.org/).

In all cases in which there are mutual events occurring in correspondence with observations, they are reported in Table 1. In all other cases the two bodies are visually separated, thus in principle, they both fall within our FOV and can contribute to the spectral properties observed.

In order to estimate the instantaneous illuminated and observable surface coverage for each observation, we computed for each epoch the sub-Earth point and the sub-solar point on both Didymos and Dimorphos surfaces.

Supplementary Fig. 1 shows an example of surface coverage for Didymos (upper panel) and Dimorphos (lower panel) for one epoch (spectrum #3 AF784961 or spectrum #11 AF800545). The solid yellow line indicates the light-night terminator on the body and the star symbol indicates the sub-solar point on the surface; thus, it defines the illuminated side with respect to the terminator. The dotted red line indicates the observable-non observable terminator on the body and the red filled dot indicates the sub-Earth point on the surface; thus, it determines the observable side with respect to the terminator.

The intersection between the illuminated and the observable surfaces determines the actual region on the surface of the asteroid, which is instantaneously sampled at the corresponding epoch.

Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the coverage at the start time of a single observation, while the coverage areas depicted in Figs. 5–9 have been calculated taking into account the full exposure time of each observation.

Due to the different rotation rate of the two bodies, the longitudinal coverage on Didymos surface (see for example, Figs. 5A and 6A) is changing much faster than the longitudinal coverage on Dimorphos surface, which remains much more stable along each night (see for example, Figs. 5B and 6B).

In Figs. 6B–9B and Supplementary Fig. 1, we also indicated the location of the DART impact site (open red circle) on Dimorphos based on the value reported by Daly et al.20.

Data availability

Data used in this paper include spectra acquired with AFOSC at Asiago 1.80 m Copernico Telescope, Asiago, Italy, MODS at Large Binocular Telescope and OSIRIS camera at Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC). Asteroid spectra are provided at the link https://researchdata.cab.unipd.it/1440/ and description of the data can be found in the repository at the same link. The data generated in this study for the spectral and geometrical analysis presented are available in a source data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Rivkin, A. et al. The double asteroid redirection test (DART): planetary defence investigations and requirements. Planet. Sci. J. 2, 173 (2021).

Michel, P. et al. The ESA Hera mission: detailed characterization of the DART impact outcome and of the binary asteroid (65803) Didymos. Planet. Sci. J. 3, 160 (2022).

Thomas, C. A. et al. Orbital period change of Dimorphos due to the DART kinetic impact. Nature 616, 448 (2023).

Binzel, R. et al. Observed spectral properties of near-Earth objects: results for population distribution, source regions, and space weathering processes. Icarus 170, 259 (2004).

De Leon, J., Licandro, J., Duffard, R. & Serra-Ricart, M. Spectral analysis and mineralogical characterization of 11 olivine pyroxene rich NEAs. Adv. Space Res. 37, 178 (2006).

De Leon, J., Licandro, J., Serra-Ricart, M., Pinilla-Alonso, N. & Campins, H. Observations, compositional, and physical characterization of near-Earth and Mars-crosser asteroids from a spectroscopic survey. Astron. Astrophys. 517, 23 (2010).

Dunn, T. L., Burbine, T. H., Bottle, W. F. & Clark, J. P. Mineralogies and source regions of near-Earth asteroids. Icarus 222, 273 (2013).

Michel, P. et al. Science case for the asteroid impact mission (AIM): a component of the asteroid impact & deflection assessment (AIDA) mission. Advan. Space Res. 57, 2529 (2016).

Ieva, S. et al. Spectral rotational characterization of the Didymos system prior to the DART impact. PSJ 3, 183 (2022).

Walsh, K. J. & Jacobson, S. A. Formation and evolution of binary Asteroids. In Asteroids IV (eds Michel, P., DeMeo, F. E. & Bottke, W. F.) 375–393 (University of Arizona Press, Tucson, 2015).

Scheirich, P. & Pravec, P. Pre-impact mutual orbit of the DART target binary asteroid (65803) Didymos derived from observations of mutual events in 2003–2021. PSJ 3, 477 (2022).

Lazzarin, M. et al. Phaethon variability during December 2017 closest approach to Earth. Planet. Space Sci. 165, 115 (2019).

Kareta, T. et al. Ejecta evolution following a planned impact into an asteroid: the first five weeks. ApJL 959, 12 (2023).

Li, J.-Y. et al. Ejecta from the DART-produced active asteroid Dimorphos. Nature 616, 52–456 (2023).

Opitom, C. et al. Morphology and spectral properties of the DART impact ejecta with VLT/MUSE. Astron. Astrophys. 671, id.L11 (2023).

Bus, S. J. & Binzel, R. P. Phase II of the small main-belt asteroid spectroscopy survey. A feature-based taxonomy. Icarus 158, 146 (2002).

Polishook, D. et al. Near-IR spectral observations of the Didymos system - daily evolution before and after the dart impact, indicates Dimorphos originated from Didymos. Planet. Sci. J. 4, 229 (2023). 12.

Scheirich, P. et al. Dimorphos orbit determination from mutual events photometry. Planet. Sci. J. 5, 17 (2024).

Lin, Z.-Y., Vincent, J.-B. & Ip, W.-H. Physical properties of the Didymos system before and after the DART impact. Astron. Astrophys. 676, A116 (2023).

Daly, T. R. et al. Successful kinetic impact into an asteroid for planetary defence. Nature 616, 443 (2023).

Vincent, J.-B. shapeViewer, a Mapping tool for the morphological analysis of small bodies and mission operations planning. In 49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, Vol. 2083, 1281 (LPI Contribution, 2018).

Schroeder, S. E. et al. Laboratory observations and simulations of phase reddening. Icarus 239, 201–206 (2014).

Luu, J. X. & Jewitt, D. Charge-coupled device spectra of asteroids. I. Near-earth and 3:1 resonance asteroids. Astron. J. 99, 1985 (1990).

Perna, D. et al. A spectroscopic survey of the small near-Earth asteroid population: peculiar taxonomic distribution and phase reddening. Planet. Space Sci. 157, 82–95 (2018).

Gargiulo, A. et al. SIPGI: an interactive pipeline for spectroscopic data reduction. In Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 514, 2902–2914 (Oxford University Press, 2022).

Doug, T. The Iraf data reduction and analysis system. In Instrumentation in astronomy VI; Proceedings of the Meeting Tucson, AZ, 733 (Bellingham, WA, Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers, 1986).

Acknowledgements

Monica Lazzarin, Fiorangela La Forgia, and Alessandra Migliorini are grateful to the Italian Space Agency (ASI) for financial support through agreement No. 2022-8-HH.0 for ESA’s Hera mission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L., F.L.F., A.M., and A.F. have prepared the manuscript. M.L., F.L.F., A.M., E.F., A.F., P.O., and A.C.M. participated in data acquisition, reduction, and analysis. J.d.L., S.G., and D.O. contributed to data acquisition (from the GTC) and analysis. M.L., F.L.F., A.M., A.F., A.C.M., J.d.L., P.M., M.K., I.C., S.U., N.C., E.A., M.A., M., T.K., J.-Y.L., M.P., and A.S.R. participated in the discussion of the data, interpretation, and analysis of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Humberto Campins, Stefan Schroeder, Faith Vilas, and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lazzarin, M., La Forgia, F., Farina, A. et al. Spectroscopic insights into the near-earth didymos-dimorphos binary system following the double asteroid redirection test (DART) mission impact. Nat Commun 17, 551 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67242-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67242-1