Abstract

Electrocatalytic N2O reduction reaction offers a sustainable solution of converting greenhouse gas N2O to N2 under ambient conditions, but achieving high single-pass conversion remains challenging. Here, we present a gas-diffusion-electrolyzer system with copper-silver bimetallic nanoalloy serving as the catalyst for efficient N2O reduction, realizing a single-pass conversion rate of 79.4% and a decomposition rate of 1381.7 μmol h−1 mgcat−1 for 10 vol.% N2O. Computational fluid dynamics simulation shows that the system optimizes gas flow regime and reduces diffusion distance compared to batch system, ensuring a uniform N2O distribution over cathode surface. The combination of Ag with Cu synergistically facilitates the adsorption, hydrogenation, and cleavage of the N–O bond in N2O. Techno-economic assessment indicates the levelized N2O decomposition cost varies between 1.66−2.14 US$ kg−1. Our findings underscore the substantial potential and practical viability of electrocatalytic N2O decomposition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is the third most significant greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4), with a global warming potential (GWP) of 273 ± 128 times that of CO21. Beyond its role in intensifying global warming, N2O, which ascends to the stratosphere participates in photochemical reactions that contribute to ozone layer depletion. Its ozone depletion potential (ODP) of approximately 0.017 is more than double that of chlorofluorocarbons, establishing N2O as the primary anthropogenic stratospheric ozone-depleting substance of the 21st century2,3. The long atmospheric lifespan of N2O (116 ± 9 years)4 underscores its substantial impact on both global warming and ozone depletion, highlighting it as a critical environmental hazard. Among anthropogenic sources, industrial emissions constitute 14–20% of N2O emissions5,6, primarily originating from the tail gases of chemical processes such as the production of adipic acid, nitric acid, and caprolactam7. These industrial emissions are characterized by high N2O concentrations (0.3–40 vol.%) and well-defined emission patterns, rendering them suitable for targeted mitigation using effective abatement technologies.

Traditional N2O treatment methods predominantly rely on thermocatalytic processes, including direct decomposition (deN2O)8,9,10,11 and selective catalytic reduction (SCR)12,13,14,15. These high-temperature approaches (operating above 350 °C) are both energy-intensive and carbon-intensive. Moreover, the catalysts employed in these processes are susceptible to deactivation caused by coexisting water vapor, oxygen oxidation, or sintering (Fig. 1)16,17,18. Secondary pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOx) may be generated through the oxidation of N2O by *O species formed during N2O decomposition19. In contrast, the electrocatalytic N2O reduction reaction (N2ORR) has emerged as an environmentally friendly and sustainable alternative (Fig. 1)20. This approach utilizes renewable electrical energy directly through cathodic N2O reduction, thereby eliminating energy losses associated with conversion to heat. Unlike thermocatalytic methods, N2ORR is not hindered by challenges such as water interference, oxygen oxidation, or catalyst sintering21. During N2ORR, N2O is reduced to N2 via a two-electron (2e−) pathway without producing secondary pollutants: N2O + H2O + 2e− → N2 + 2OH−, E0 = 1.77 V vs RHE22. In neutral or alkaline electrolytes, the hydroxide ions (OH−) generated from the oxygen atom of N2O can serve as effective absorbents for CO2, offering the additional benefit of CO2 capture from N2O-containing exhaust gases or directly from the atmosphere.

Despite its potential, N2ORR significant challenges for practical application, primarily due to its relatively low single-pass conversion efficiency. Current studies report N2O conversion rates of only 0.3–29.5% when treating 30–100 vol.% N2O, which are considerably lower than the near-complete conversion (100%) achieved by thermocatalysis at 350–600 °C under comparable space velocities (~200 L h−1 g−1)23,24,25,26,27. Insufficient single-pass conversion allows residual N2O to persist in the outlet stream. Although tandem systems could ensure complete degradation, they would increase complexity, cost, and footprint, undermining scalability. Therefore, enhancing single-pass efficiency through improved reactor design and catalyst development is of central importance. By narrowing this gap, N2ORR can achieve conversion levels comparable to thermocatalysis—while operating under mild conditions using renewable electricity. The low N2O conversion rate can be attributed to two primary factors: (1) restricted mass transfer in the H-type batch cell (abbreviated as H cell) commonly used in proof-of-concept studies, and (2) suboptimal catalyst performance during critical reaction steps, including the adsorption, hydrogenation, and cleavage of the N–O bond in N2O (Fig. 1).

The H cell exhibits low N2ORR kinetics resulting from low N2O solubility, limited N2O diffusion, and insufficient interfacial contact between N2O and electrode. The gas-aqueous-solid triple phase interactions, coupled with low solubility of N2O in water (0.617 mL gas/mL)28, lead to random collisions between N2O gas bubbles and the cathode, accompanied by a short residence time. The accumulation of stagnant bubbles adhering to electrode surface also obstructs catalyst sites, impeding their effective participation in the reaction29. The mass transfer of N2O is restricted by the diffusion length at the microscale (~50 μm) within the H cell, with a considerable thickness of mass transfer boundary layer hindering N2O and catalyst interaction30,31. Consequently, these mass transfer limitations result in sluggish reaction rates32. On the other hand, the relatively inert nature of N2O makes it hard for adsorption and activation on catalysts33. N2O typically adsorbs on the catalyst surface through physical adsorption21, hindering the charge transfer between N2O and the catalyst. The hydrogenation and N–O bond cleavage are often recognized as rate-limiting steps (RDS), attributing to the weak proton affinity of N2O23,34. The substantial energy barriers of these RDS hinder the progression of the reaction, ultimately leading to low overall reaction rates.

Herein, we designed a gas-diffusion-electrolyzer (GDE) system incorporating a CuAg bimetallic nanoalloy catalyst to enhance the efficiency of N2ORR (Fig. 1). GDE integrating gas diffusion electrodes with gas-fed flow channel has been demonstrated to improve mass transfer in CO2 and O2 reduction systems32,35. Bimetallic nanoalloys have shown potentials in reducing kinetic overpotentials and optimizing charge transfer36,37. Modifications in electronic structure, geometric strain, and chemical bifunctionality of such alloys enhance the interaction between catalyst and N2O20,33. A structure-activity analysis revealed that a CuAg alloy with a molar ratio of 10:1 achieved the highest single-pass degradation rate of 79.4% at −1.4 V vs RHE, with an inlet concentration of 10 vol.% N2O at a room temperature of 25 °C. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations compared the gas flow regime of designed GDE with H cell, revealing a significant enhancement in mass transfer efficiency of GDE achieved by enhanced gas flow velocity, concentration, and uniformity. In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) and density functional theory (DFT) elucidated that the synergistic effect between Cu and Ag, which enhanced the adsorption and hydrogenation of N2O and the cleavage of N–O bond. A techno-economic assessment (TEA) was conducted to evaluate the levelized cost distribution and the economic factors influencing the viability of N2ORR.

Results

Synthesis and performance of CuAg in GDE-N2ORR

The synthesis of CuAg nanoalloys loaded on multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) involved an incipient wetness co-impregnation method with Cu(NO3)2 and AgNO3 as metal precursors, and subsequent calcination in 5 vol.% H2/Ar (Fig. 2a)38. The nanoalloys were categorized based on actual atomic molar ratios detected by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES), denoted as CuAgx (x = 0.03, 0.04, 0.13, 0.25, 1, 7, 14, 40, 70) (Table S1). For comparison, Cu NPs or Ag NPs were synthesized using amounts consistent with CuAg0.13 and CuAg14, respectively. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed the overlapping of MWCNT networks that formed a non-dense matrix conducive to rapid electron migration (Fig. S1a)39. From BET and pore volume measurements, the porous structure of MWCNT possessed high specific surface area (Table S2), serving as effective conduits for gas adsorption and desorption. TEM showed the finely distributed nanoalloys on MWCNT substrate with diameters of approximately 30–40 nm (Fig. 2b). The lattice spacing of 0.25 nm in the CuAg(111) nanoalloy increased compared to 0.21 nm of Cu(111) and 0.24 nm of Ag(111) (Fig. S1b), which was attributed to the lattice stretching effect induced by the larger Ag atoms than Cu40. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping confirmed the successful synthesis and uniform distribution of Cu and Ag elements (Fig. 2c).

a Illustration of synthesis of CuAg catalysts. b TEM image and particle size distribution of CuAg0.13. c EDS elemental mappings of CuAg0.13. d Schematic diagrams and gas diffusion mechanisms of GDE, and the SEM images of the side and the top view of working electrode. e Reaction rate fitting curves of CuAg1 CuAg0.13, CuAg0.03, and Cu NPs at −1.4 V vs RHE. f 10 vol.% N2O conversion rates of CuAg0.13 at −1.4 V vs RHE in GDE and H cell. g 10 vol.% N2O conversion rates and h FEN2ORR of CuAg at different potentials. The voltages were not iR corrected (electrode surface area = 2.25 cm2, RΩ = 1.6 Ω). The data in (f–h) are presented as mean values ± s.d. (n = 3).

X-ray diffraction (XRD) showed diffraction peaks at 43.2°, 50.3°, and 73.9°, corresponding to the (111), (200), and (220) crystal planes of metallic Cu, respectively (PDF#70 − 3038) (Fig. S2a). The peaks at 38.1°, 44.3°, 64.4°, and 77.5° were associated with (111), (200), (220), and (311) of metallic Ag (PDF#04-0783). Note that the Cu(111) diffraction peak in CuAg alloy exhibited a smaller 2θ value compared to that of Cu NPs (Fig. S2b), whereas the Ag(111) peak shifted toward a higher 2θ value relative to Ag NPs (Fig. S2c). The extent of these shifts increased with the proportion of doped elements, indicating lattice strain induced by atomic introduction, consistent with the increased lattice spacing observed in TEM analysis 41,42.

The elemental compositions and chemical states of the catalyst surfaces were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The survey spectra confirmed the presence of Cu, Ag, C, and O elements in the CuAg catalysts (Fig. S3a). Quantitative XPS analysis revealed the surface atomic ratios of Cu and Ag (Table S3). In the Cu 2p spectra, peaks at 957.7 eV and 932.8 eV were identified for Cu0/+ species (Fig. S3b). A small portion of Cu2+ at 955.8 eV and 935.0 eV was observable, potentially arising from air oxidation21. Compared to Cu NPs, following Ag introduction, the Cu0/+ peaks exhibited a positive shift to higher binding energy due to the electron transfer from Cu to Ag, resulting the formation of Cu with higher valence states35. The Cu LMM Auger spectra confirmed the existence of Cu+ (Fig. S3c). Notably, the Cu0/Cu+ ratio in CuAg0.13 was the lowest (0.53), indicating that this composition exhibited the highest extent of electron transfer from Cu to Ag. The Ag 3d spectra displayed peaks at 374.3 eV and 369.3 eV, corresponding to Ag0 in Ag 3d2/3 and Ag 3d2/5, respectively (Fig. S3d)43. Compared to Ag NPs, a negative binding energy shift was observed for CuAg samples, indicating that Ag acted as an electron acceptor, consistent with Cu XPS.

A GDE system was designed to test N2ORR performance of CuAg nanoalloys (Fig. 2d). The working electrode consisted of a gas diffusion layer (GDL, ~160 μm), a microporous layer (MPL, ~70 μm), and a catalyst layer (CL, ~100 μm). In this configuration, the gas flow field directly contacted with GDL, where carbon fibers provided structural support, while the MPL served as a gas diffuser, facilitating gas transport towards the catalyst layer. The MPL contained a mixture of carbon powders and a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) hydrophobic layer. The carbon powders were firmly bound to the catalyst layer, facilitating efficient electron transfer and gas diffusion, while the PTFE layer acted to prevent catholyte flooding. Upon receiving gaseous reactants, the catalyst layer in contact with electrolyte promoted reaction at the gas–liquid–solid triple-phase. After N2O entered the inlet, it flowed through the gas-fed channel, which was designed with a serpentine flow path measuring 105 mm in length, 7 mm in depth, and a square cross-sectional area of 1.5 × 1.5 cm2. The subparts of GDE included a cathode chamber, an anode chamber, and current collectors (Fig. S4). As shown in Fig. 2d, the supplied N2O diffuses along the path of serpentine flow channel-GDL-MPL-CL, driven by the concentration gradient, ultimately reaching the gas–liquid–solid triple-phase boundary where electrochemical reduction occurs. At this interface, the gaseous products, N2 of N2ORR and H2 of hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), were generated and experienced the highest local chemical potential gradient, which facilitated the desorption from the electrolyte and initiated reverse diffusion, and eventually transported back to the flow channel. These species were subsequently carried out of the system by the gas stream and introduced into the gas chromatograph (GC) in a continuous flow for product analysis (Fig. S5).

We investigated N2O degradation efficiencies across initial concentrations from 5 to 30 vol.%—a range representative of industrial exhaust gases, as well as pure N2O for comparison. The N2O degradation efficiency peaked at 10 vol.% (typical of caprolactam flue gas) and declined at higher concentrations (Fig. S6a), reflecting a trade-off between mass transfer and catalytic kinetics. Low concentrations limited N2O availability, while higher partial pressures initially enhanced diffusion and surface coverage. Beyond 10 vol.%, short residence time in the flow reactor reduced conversion despite faster reaction rates. The optimal performance at 10 vol.% signifies balanced N2O utilization, where surface kinetics and mass transport were synergistically aligned. Notably, under 100% N2O, our catalyst reached a maximum Faradaic efficiencies for N2ORR (FEN2ORR) of 95.0% at −0.8 V vs RHE (Fig. S6b), demonstrating performance comparable to prior reports under concentrated conditions21,33,44. More importantly, it sustained high conversion and selectivity even at lower N2O partial pressures—typical of industrial emissions—where competing reactions intensify, and most conventional catalysts fail.

With varied gas flow rates ranging from 5 to 9 mL min−1, 5 mL min−1 exhibited the highest degradation rate with a residence time of 19.7 s (Fig. S7a). By adjusting gas flow rates, the degradation rates and reaction rate constants (k) for different gas residence times were acquired (Figs. 2e and S7b). These results indicated that an extended residence time for N2O enhances the degradation rate, suggesting that slower gas flow rates promote more thorough reactions. Among the comparative samples analyzed, CuAg0.13 exhibited the highest k value of 0.063 s−1, demonstrating the fastest reaction kinetics. The N2O conversion rates in GDE at 5 mL min−1 (65.1–79.4%) were approximately 3.2 times higher than those in H cell (20.1–25.2%) (Fig. 2f), validating that GDE significantly enhanced the reaction rate of N2ORR.

Furthermore, we explored the structure-activity relationship of CuAg with varying Cu:Ag molar ratios. The degradation rates and FEN2ORR of CuAg nanoalloys exhibited a characteristic sloping “M-volcano” shape across a voltage range of −0.8 to −1.6 V vs RHE (Fig. 2g, h). This “M-volcano” shape featured two prominent peaks, with CuAg0.13 exhibiting N2O conversion rates of 65.1–79.4% and FEN2ORR of 60.5–92.6%, while CuAg14 displayed N2O conversion rates of 26.4–52.9% and FEN2ORR of 21.5–62.7%. CuAg0.13 showed the highest N2 yield rates among CuAg nanoalloys (Fig. S8). Analysis of the tail gas composition at the GDE outlet using a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) coupled with GC revealed only N2 and H2 signal peaks, with no detectable NOx byproducts (Fig. S9). From UV-Vis measurement, potential liquid phase products such as NH4+, N2H4, NO2−, and NO3− were not observable, suggesting that N2O only underwent reduction and terminated at N2 and without further hydrogenation under the applied electrochemical conditions (Table S4).

Owing to the inherently weaker and less reliable N2 signal in GC measurements, the FE for N2O degradation was adopted as a more robust indicator of electron selectivity toward the primary reaction (Fig. S10a). Under applied potentials ranging from −0.8 to −1.6 V vs RHE, the N2O conversion rate exhibited a volcano-type dependence, reaching a maximum 79.4% at −1.4 V vs RHE. In contrast, the FEN2ORR progressively declined with increasing voltage, attributable to the enhanced parasitic HER competing with N2ORR. Across the entire potential window, CuAg0.13 outperformed controls such as MWCNT, Cu, and Ag NPs, underscoring the bimetallic synergistic effect that enhanced N2ORR and expanded the effective reaction voltage window (Figs. S10b and S11a). In general, catalysts with higher Cu content demonstrated greater activity than those with higher Ag content, indicating that Cu serves as the primary active site. This outperformance was also attributed to the stronger inhibition of Cu on HER21. Notably, CuAg0.13 and Cu NPs exhibited FEHER lower than CuAg14 and Ag NPs due to better inhibition on HER by Cu (Fig. S11b).

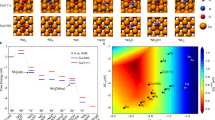

CFD simulation comparison between GDE and H Cell for N2ORR

To provide a more intuitive comparison of mass transfer in GDE and H cell for N2ORR, CFD simulations using COMSOL were applied to model the real-time N2O flow velocity and volume fraction along the electrode surface (Figs. 3a–d and S12). The flow rate of N2O within the GDE remained consistently uniform, with minimal temporal fluctuations, facilitating stable and continuous diffusion of N2O. Along the vertical central axis of the flow channel, viscous fluid effects created a characteristic volcano-shape velocity distribution, with a peak velocity at the center (17.8 mm s−1) that gradually decreased towards the edges (Fig. 3a, e, top). In contrast, the flow dynamics within the H cell were markedly different. At the gas inlet, the flow velocity was initially high near the cathode but diminished as the gas traveled through the cell, resulting in an uneven distribution (Fig. 3b, f, top). By 7 s after the initiation of gas flow, the system reached a quasi-steady state, characterized by the upward and lateral movement of gas bubbles towards the electrolyte. However, the flow velocity in the vicinity of the cathode was significantly lower (1.6 mm s−1), indicating suboptimal flow dynamics and limitations in the continuous mass transfer of N2O along the cathode interface.

N2O flow velocity along the electrode surface for (a) GDE and (b) H cell at 1 s and 7 s, and the N2O volume fraction along the electrode surface for (c) GDE and (d) H cell at 1 s and 7 s. The N2O flow velocity and volume fraction along the red line varies with distance for (e) GDE and (f) H cell. g Scheme of gas diffusion kinetic from flow channel to gas–liquid–solid triple-phase boundary. h N2O ideal diffusion rate and decomposition rate at −1.4 V vs RHE of different inlet concentrations.

Additionally, the volume distribution analysis revealed a marked improvement in the uniformity of N2O distribution within the serpentine flow channel (Fig. 3c). With prolonged N2O feeding, the gas became uniformly dispersed throughout the flow channel, with a fraction diffusing into and penetrating the catalyst layer. Most regions attained a volume fraction of approximately 15.0% (Fig. 3e, bottom), demonstrating that the GDE achieved a high gas concentration and facilitated smooth diffusion across the cathode surface. In contrast, in the H cell, the N2O volume fraction was relatively high near the gas inlet (14.5%) but exhibited a rapid decline with increasing distance from the cathode due to the unconfined movement of gas molecules (Fig. 3d). In addition, buoyancy effects caused gas bubbles to accumulate near the top of the electrolyte, resulting in a volume fraction of approximately 10%. This distribution created a vertical concentration gradient, with higher concentrations at the top and a gradual decrease toward the bottom. Along the horizontal centerline of the cathode, a noticeable concentration gradient was observed, peaking at the inlet and declining sharply to 4.8% in the electrolyte at 7s (Fig. 3f, bottom). These CFD simulations demonstrate that the GDE enables stable, rapid, and continuous N2O diffusion to the cathode surface by optimizing both gas flow velocity and volume distribution.

We further investigated the spatial distribution of N2O with different N2O/Ar vol.% ratios in the flow channel and corresponding mass transfer through the GDE. The simulations showed that the N2O volume fraction and the diffusion flux through the GDE slightly decreased along the flow direction due to pressure drop (Fig. S13). Higher N2O inlet concentrations enhanced the diffusion flux by overcoming mass transfer resistance, facilitating both N2O influx and gaseous product (N2, H2) release (Fig. 3g). However, experimental N2O decomposition rates did not scale linearly with concentration, instead plateauing due to catalytic kinetic limitations (Fig. 3h). This indicates that the reaction rate approached a maximum due to saturation of active sites. The steepest degradation slope occurred at 10 vol.%, indicating the most efficient rate enhancement per concentration increase. Combined with simulated diffusion trends and experimental conversion data, these findings suggest that 10 vol.% N2O optimally balanced degradation efficiency and reaction rate under the tested conditions, maximizing overall reactant utilization. This reflects a transition from mass-transfer-limited to kinetically controlled regimes at higher concentrations.

Electrochemical properties of CuAg nanoalloys

To elucidate the intrinsic kinetics of N2O reduction, we conducted linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) tests on various catalysts. Among the tested catalysts, CuAg0.13 exhibited the highest current density and the lowest onset potential (Fig. 4a, b). The LSV curves of CuAg0.13 in Ar- and N2O-saturated solutions demonstrated its strong activity for N2ORR (Fig. 4c). Comparatively, the lower current densities of Cu and Ag NPs compared to CuAg0.13 highlighted the synergistic interaction between Cu and Ag in enhancing N2ORR. CuAg0.13 also achieved the lowest Tafel slope (107.5 mV dec−1) (Fig. 4d), indicative of favorable reaction kinetics. Charge-transfer resistance (Rct) analysis, conducted via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), revealed that CuAg0.13 exhibited a smaller Nyquist plot radii than other catalysts, signifying more efficient charge transfer (Fig. 4e). The electrochemical surface area (ECSA) was assessed through double-layer capacitance (Cdl) derived from cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves and further normalized by roughness factor (Rf). CuAg0.13 exhibited the highest Cdl (15.53 mF cm−1) and largest ESCA (1271 cm2), reflecting a greater abundance of accessible active sites (Figs. 4f, S14, and Table S5).

LSV curves under N2O-saturated electrolyte of a Cu NPs, CuAg0.03, CuAg0.13, CuAg1, and b Ag NPs, CuAg70, CuAg14, CuAg1. c LSV curves of CuAg0.13 under Ar- and N2O-saturated electrolytes. d Tafel slopes of CuAg1, CuAg0.13, CuAg0.03, and Cu NPs under N2O-saturated condition. e Nyquist plots and f Cdl measurement of CuAg1, CuAg0.13, CuAg0.03, and Cu NPs. g Current density and N2O conversion rate of CuAg0.13 under different gas atmospheres at –1.4 V vs RHE over 48 h. h XRD pattern of the electrolyte after 1 h reaction at –1.4 V vs RHE (Electrolyte: 30 mL of 0.07 mol L−1 K2SO4; Inset: the picture of dried after-reaction electrolyte). The voltages were not iR corrected.

The 48-h stability test of CuAg0.13 at −1.4 V vs RHE confirmed catalytic durability, with the N2O conversion rate consistently maintained at 75.2–82.7% (Fig. 4g). The current density remained stable overall, showing only minor fluctuations attributable to OH⁻ accumulation and associated changes in electrolyte concentration over time. Post-reaction ICP-OES analysis detected minimal metal leaching (23.9 μg L−1 Cu and 0.07 μg L−1 Ag) in the electrolyte. Comprehensive characterization confirmed the catalyst’s structural integrity after reaction. Elemental mapping revealed homogeneous spatial distribution of Cu and Ag on the nanoparticles (Fig. S15a). XPS analysis of the reacted catalyst displayed no detectable shift in characteristic binding energies of Cu 2p and Ag 3d spectra (Fig. S15b), or surface segregation (Table S3). These results demonstrated that CuAg0.13 exhibited both reaction stability and structural robustness under operating conditions.

To assess practical feasibility, we evaluated N2ORR performance under simulated caprolactam tail gas containing 5 vol.% CO2 and 0.5 vol.% O2 (Fig. 4g). The presence of CO2 led to an initial current increase, attributable to (bi)carbonate-enhanced conductivity, followed by a decline after electrolyte renewal due to electrode fouling and increased resistance. N2O conversion decreased from 78.9% to 64.8% over 48 h, indicating that carbonate accumulation blocked active sites and inhibited N2ORR. In contrast, 0.5 vol.% O2 caused minor current fluctuations from competing oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) but maintained stable N2O conversion (74.6–82.5%), demonstrating negligible impact. These results confirmed robust catalyst stability under long-term operation, with CO2 identified as the primary challenge for real-flue gas applications. Further efforts should focus on understanding competitive gas interactions and developing anti-fouling strategies—such as active-site engineering and interface modulation—to enable efficient N2O reduction in complex gas streams.

The decomposition rate is a key practical metric for flow electrolyzer systems, as it reflects the combined influence of catalyst activity and residence time, providing a quantitative measure of reactant conversion per unit time. This parameter is crucial for assessing processing capacity and industrial scalability in continuous-flow electrochemical systems. Compared to prior studies, our system achieved a significantly enhanced N2O decomposition rate of 1381.7 μmol h−1 mgcat−1 at a short residence time of only 19 s (Fig. S16a and Table S6). This performance is competitive with previously reported N2O electroreduction rates by approximately 33- to 2100-fold21,23,24,33,34,45,46, and exceeds thermocatalytic N2O decomposition rates by nearly 1200-fold (Fig. S16b and Table S7)47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66, Furthermore, the system maintained high decomposition rate, FEN2ORR, and current density even under relatively low N2O concentrations (Fig. S16c), underscoring the strong viability of our approach for practical implementation.

We further investigated the trajectories of the O atom originating from N2O during N2ORR. As reaction proceeded, the O atoms released from N2O decomposition gradually concentrated in the aqueous phase, specifically in the form of OH−. The N2ORR at −1.4 V vs RHE in a neutral electrolyte (30 mL of 0.07 M K2SO4, initial pH = 7.1 ± 0.10) resulted in a significant increase in solution pH to 13.0 ± 0.05 after 1 h, corresponding to a net OH− production of ~1.2 mmol from N2ORR after subtracting the background contribution from the HER (final pH = 12.8 ± 0.05, ~1.8 mmol OH−). This experimental OH− yield closely aligned with the theoretical value of ~1.4 mmol, calculated based on the measured N2O conversion efficiency of ~70%. This close correspondence confirmed that O atoms from N2O were quantitatively converted to OH− ions during N2ORR. The XRD analysis of the dried electrolyte identified a pronounced K2CO3 peak, which resulted from the reaction between KOH and atmospheric CO2 (Fig. 4h). This finding indicates that the electrolyte, enriched with KOH from N2O decomposition, can function as an efficient CO2 absorbent, offering the additional advantage of CO2 capture—an outcome not achievable through conventional thermocatalysis. Under the specified experimental conditions (0.07 M KOH with 0.27 M K2SO4 as the electrolyte, an applied potential of −1.4 V vs RHE, and an electrode area of 2.25 cm2), the system exhibited the capacity to degrade 2.05 kg N2O and capture 1.58 kg CO2 within a 24-h period, corresponding to a CO2 equivalent (CO2e) reduction of 24.9 tCO2e m−2 d−1 (CO2e = (mass of gas) × (GWP of gas)).

Mechanism analysis

In-situ DRIFTS spectra of CuAg0.13, Cu NPs, and Ag NPs (abbreviated as CuAg, Cu, and Ag, respectively, in Fig. 5) were measured across a potential range from open circuit potential (OCP) to −1.6 V vs RHE. At OCP, characteristic peaks of adsorbed N2O were observed on the CuAg surface at 1275 cm−1, 1301 cm−1, 2209 cm−1, and 2237 cm−1 67. These peaks were subsequently subtracted as background values in further measurements (Fig. S17). Upon applying voltage, a peak at 1406 cm−1, associated with the *NNOH intermediate product68, was observed on the CuAg surface, indicating the hydrogenation of adsorbed N2O (Fig. 5a, b). The peaks at 1635 cm−1 and ~3400 cm−1 have been reported as the δ(O–H) and ν(O–H) vibrational modes of adsorbed *OH or H2O68,69. However, since H2O was consumed rather than produced in this reaction, these signals were more reasonably attributed to surface-adsorbed *OH intermediates formed via N–O bond cleavage of *NNOH. In contrast, the spectrum of Cu lacked a *NNOH peak, whereas a weaker *OH peak was observed, likely originating from H2O dissociation (Fig. 5c, d). The Ag spectrum showed no discernible absorption peaks of either *NNOH or *OH (Fig. S18). Active hydrogen (H*) was found to play a pivotal role in the initial hydrogenation step of N2ORR. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) results showed that the H* production in Ar-saturated conditions followed the order of CuAg > Cu > Ag (Fig. 5e), indicating the strongest capability of CuAg to produce H*. In addition, the H* signal intensity of CuAg decreased under N2O-saturated conditions compared to Ar, indicating that H* was consumed during the hydrogenation of N2O in the N2ORR process (Fig. 5f).

Mechanism analysis of N2ORR. In-situ DRIFTS spectra of N2ORR on (a, b) CuAg, (c, d) Cu. e The EPR spectra of H* on CuAg, Cu, and Ag in N2O-saturated electrolyte at −1.4 V vs RHE. f The EPR spectra of H* on CuAg in Ar- and N2O-saturated electrolyte at −1.4 V vs RHE. The voltages were not iR corrected. g Free-energy diagrams and intermediate configurations of N2ORR on CuAg, Cu(111), and Ag(111). h Charge density difference of CuAg and CuAg-*NNOH.

To elucidate the catalytic mechanism of N2ORR, a comparative analysis of the lowest-energy N2ORR pathways for CuAg, Cu, and Ag catalysts was conducted by DFT calculations (Fig. 5g). The electrochemical reduction was carried out in an alkaline medium (pH = 13); accordingly, the DFT simulations were conducted under analogous alkaline conditions to reflect the actual reaction environment. Based on the overall cathodic half-reaction N2O + H2O + 2e− → N2 + 2OH− and corroborated by in situ DRIFTS analysis, the reduction of N2O to N2 followed the pathway: N2O → *N2O → *NNOH → *N2 + *OH → N2. Efficient adsorption and activation of N2O are essential prerequisites for optimal N2ORR performance. As depicted in the intermediate configurations (Fig. 5g, inset), *N2O preferentially adopted a side-on adsorption configuration on CuAg and Cu(111). Notably, on Cu(111), N2O formed two N–Cu bonds, whereas on CuAg, it formed one N–Cu bond and one O–Cu bond. On Ag(111), N2O exhibited physisorption, as evidenced by the substantial distance between N2O molecule and the substrate33. The adsorption energy barrier of N2O on CuAg (0.32 eV) was lower than that on Cu(111) (0.85 eV), implying that the incorporation of Ag facilitated the adsorption of N2O.

After adsorption, the H* preferentially attacked the O atom of N2O, forming *NNOH intermediate. At this point, the adsorbed N2O molecule on CuAg underwent a structural reorientation, adopting a side-on adsorption configuration with two N–Cu bonds, one of which was adjacent to Ag, exposing the O atom to facilitate the acceptance of H*. The hydrogenation of *N2O to *NNOH on CuAg proceeded with a minimal energy barrier of 0.07 eV, whereas the ΔG for the same process on Ag(111) reached up to 0.4 eV, suggesting inhibited *NNOH production on Ag(111), consistent with in-situ DRIFTS. The cleavage of N–O bond in *NNOH occurred readily on CuAg with the most downhill free energy of −1.58 eV among three catalysts, which was more negative compared to Cu(111) (−1.49 eV) and Ag(111) (−1.46 eV), suggesting a more favorable decomposition process on CuAg. Collectively, these results highlight that the synergistic effects of Cu and Ag in the nanoalloy, which reduce the thermodynamic barriers of N2O adsorption and hydrogenation while facilitating N–O bond cleavage, thereby enhancing N2O decomposition.

The charge density difference diagram further illustrated the Cu-Ag synergy, as revealed from the electron perturbation in CuAg nanoalloy upon Ag introduction. Due to the higher electronegativity of Ag, it readily attracted electrons from neighboring Cu atoms (0.186 e‒), inducing charge transfer that left Cu in a more positively charged state than Cu in Cu(111) (Fig. 5h, top, and Fig. S19a, b). Such positively charged Cu species would facilitate more efficient charge transfer compared to metallic Cu70,71. DFT calculation suggested that this electron-imbalanced alloy structure could promote the adsorption and activation of the *NNOH intermediate, as evidenced by the stronger electron transfer in CuAg-*NNOH (1.113 e‒ vs 1.109 e‒ of Cu-*NNOH and 1.107 e‒ of Ag-*NNOH) (Fig. 5h, bottom, and Fig. S19c, d). These findings collectively revealed that Ag would primarily modulate the electronic environment of Cu through electron withdrawal, thereby creating positively charged Cu sites that optimally adsorbed and activated key reaction intermediates.

Techno-economic assessment

To investigate the economic feasibility of N2ORR, a comprehensive TEA was conducted to evaluate the levelized cost of N2O decomposition (LCN2O). Under experimental conditions ranging from −0.8 to −1.6 V vs RHE (equivalent to 3.0−4.4 V full-cell voltage, Table S8), the LCN2O of N2ORR varied between 1.66 and 2.14 US$ kg−1 (Fig. 6a), showing a “V-shape” correlation with varying voltages. This behavior stems from the competing effects between increased operational costs due to more energy consumption at higher voltages and reduced capital costs as the electrolyzer area decreases72. The optimal balance between the two factors occurs at an intermediate voltage of −1.4 V vs RHE, where the lowest cost is achieved73. The LCN2O distribution revealed that operating costs accounted for 50.3%, and capital costs made up 49.7% (Fig. 6b). Among the capital costs, the cost of electrolyzer (28.0%) represented the largest proportions. Sensitivity analysis identified key parameters affecting the economic effectiveness of N2ORR (Fig. 6c and Table S9), with FEN2ORR, current density, and conversion rate ranking as the top three factors affecting LCN2O. Therefore, cost reductions require further advances in enhancing catalytic efficiency to simultaneously obtain a high FEN2ORR and conversion rate at increased current densities, while also minimizing energy consumption.

a LCN2O of N2ORR ranging from −0.8 to −1.6 V vs RHE. b Cost distribution of electrolyzer, BoP, membrane, installation, catalyst, maintenance, labor, electricity, and electrolyte of LCN2O at −1.4 V vs RHE. c Sensitivity analysis of FEN2ORR, current density, conversion rate, electrolyzer cost, electricity cost, operating years, and full-cell potential for N2ORR. The base case was established using experimental data obtained at −1.4 V vs RHE, which were rounded for simplicity. Based on this base case, both optimistic and pessimistic scenarios for each parameter were considered within a possible range (See Table S9 for details). The contour plot of dependence of LCN2O on d FEN2ORR and current density with 80% conversion rate, and e FEN2ORR and conversion rate at 100 mA cm−2. f Roadmap to reducing electrocatalytic LCN2O by successive changes to cost-relevant parameters. Except for (a), the remaining figures represent calculated data derived from the voltage condition of −1.4 V vs RHE.

Additionally, we analyzed the dependence of LCN2O on FEN2ORR, current densities, and conversion rates (Fig. 6d, e). The blue region represents low LCN2O achieved through optimized cell performance, characterized by high FEN2ORR, current densities, and conversion rates at −1.4 V vs RHE. Conversely, the red region corresponds to increased LCN2O associated with reduced activity. The dashed line indicates the LCN2O of traditional thermocatalysis at 0.94 US$ kg−1 (as detailed in Supplementary Information). Currently, due to the suboptimal reaction selectivity over HER, N2O conversion rates, and current density, the LCN2O of electrocatalysis (falling within the region beneath the dotted line) remains slightly higher than that of thermocatalysis. To overcome this cost bottleneck, it is of great importance to achieve high FEN2ORR and N2O conversion rates at elevated current densities.

While achieving a substantial reduction in LCN2O of N2ORR through the optimization of a single factor remains challenging, we propose a comprehensive roadmap for optimizing key factors through a waterfall analysis, highlighting the cumulative impact of various optimizations (Fig. 6f). By elevating FEN2ORR to 90% and further raising the current density to 60 mA cm−2, reductions in LCN2O of 0.24 and 0.22 US$ kg−1 were achieved, respectively. Improving the conversion rate to 90% could further reduce LCN2O by an additional 0.14 US$ kg−1. The electrolyzer system cost of N2ORR (0.981 US$ kg−1 including electrolyzer, BoP, and installation) was significantly higher than thermocatalysis (0.004 US$ kg−1). A 20% reduction in electrolyzer manufacturing costs would lower LCN2O by 0.09 US$ kg−1. Moreover, a reduction in electricity price from current 0.03 US$ kWh−1 to 0.02 US$ kWh−1 would further reduce LCN2O by 0.08 US$ kg−1. Under these optimized conditions, the electrocatalytic LCN2O could fall from 1.66 to 0.90 US$ kg−1, which is lower than the current LCN2O of thermocatalysis, marking a significant advancement towards overcoming the economic barriers of N2ORR.

Discussion

In this study, we developed a GDE system utilizing a CuAg bimetallic nanoalloy for efficient N2ORR with a high single-pass conversion rate. CFD simulations revealed a significant improvement in mass transfer within the designed GDE compared to traditional H-cell configurations. In GDE, CuAg0.13 achieved a single-pass conversion rate of 79.4% at ‒1.4 V vs RHE, along with the highest N2O decomposition rate (1381.7 μmol h−1 mgcat−1) and reaction rate (k = 0.063 s−1), which was competitive with previous N2O electrocatalysts. In-situ DRIFTS and DFT revealed a synergistic effect between Cu and Ag, enhancing N2O adsorption and hydrogenation, thereby promoting the cleavage of N–O bond. Furthermore, we highlighted the role of the KOH product during N2ORR as an absorbent for CO2, offering potential for the synergistic capture of coexisting CO2 in N2O waste streams or CO2 from the air. While laboratory-scale N2ORR has made progress, challenges remain in scaling it up for industrial applications, particularly in terms of cost. TEA identified potential routes for cost reduction by simultaneously increasing FEN2ORR and the conversion rate at higher current densities. Our findings emphasize the practical feasibility of room-temperature N2O decomposition using renewable energy sources.

Methods

Reagents and materials

Copper nitrate (Cu(NO3)2, 99.99%) and potassium sulfate (K2SO4, 99%) were obtained from Aladdin. Silver nitrate (AgNO3, 99.8%), ethanol (C2H6O, 99.7%), and potassium chloride (KCl, 99%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Experimental solutions were prepared using deionized water (DI, >18.2 MΩ·cm) from Milli-Q system.

Synthesis of catalysts

The CuAg nanoalloy synthesis involved dissolving corresponding quantity of Cu(NO3)2 and AgNO3 in pure ethanol, stirring for 30 min. Subsequently, purchased carbon nanotube powder was added to the solution, followed by stirring overnight and drying at 80 °C. The surface-modified carbon was then calcined under a H2 atmosphere at 500 °C for 3 h with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1, yielding the solid product CuAg nanoalloy catalyst.

Preparation of working electrodes

Catalysts (10 mg) and 50 μL Nafion 117 (5 wt.%, DUPONT D520) were dissolved in 0.95 mL ethanol and thoroughly mixed by ultrasonic treatment for 1 h. The resulting catalyst ink (150 μL) was dropped onto the gas diffusion layer (1.5 × 1.5 cm2, TORAY YLS −30 T) and dried at room temperature. The catalyst loading density was maintained at approximately 0.67 mg cm−2 for all experiments.

Catalyst characterization

The morphology and microstructure of CuAg catalysts were examined through SEM (ZEISS GEMINI 300 microscope, Germany) with a 3 kV accelerating voltage and high-resolution TEM (JEOL JEM F200), equipped with two JEOL energy dispersive X-ray spectrometers (super-EDS) at 200 kV. ICP-OES analysis on Thermo Fisher iCAP PRO was conducted to determine metal loading. Detailed chemical compositions of samples were analyzed using XPS with a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha system employing Al Kα radiation. XRD analysis (Rigaku Ultima IV) was performed at a scan rate of 10° min−1 within the 2θ range of 10–80° using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.542 Å). The specific surface area, pore volume and pore size distribution of catalyst were measured by static nitrogen adsorption instrument (Beijing JWGB Sci. & Tech. Co., Ltd, JW-BK32F). EPR spectra were obtained on a Bruker A300 EPR spectrometer. The instrumental parameters were kept as follows: scanning frequency: 9.652 GHz; scanning width: 100 G; scanning power: 20.03 mW.

Electrocatalytic experiments

Electrocatalytic reduction experiments were carried out in GDE with a three-electrode system at a room temperature of 25 °C, controlled by a CHI 660E electrochemical workstation. The cathode and anode chambers were separated by a proton-conductive membrane (Nafion 117). The membrane pretreatment involved boiling in ultrapure water for 1 h, treatment with 5% H2O2 at 80 °C for 1 h, immersion in 0.5 M H2SO4 at 80 °C for 2 h, and finally boiling in water for 6 h. In the reaction system, Pt foil and Ag/AgCl were employed as the counter electrode and reference electrode, respectively. The electrolyte comprised 0.27 mol L−1 KOH and 0.07 mol L−1 K2SO4, circulated at 20 mL min−1 under the control of peristaltic pump. During testing, the gas of 10 vol.% N2O/Ar was consistently supplied into the cathode flow plate at a rate of 5 mL min−1 (except where specifically mentioned), controlled by mass flow controllers (MFCs, Horiba). The gaseous effluent from the continuous-flow electrochemical reactor was directly channeled to an online gas chromatograph (GC-9660) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) and a 5 A molecular sieve column for separation. An automated fourteen-port gas sampling valve was used to periodically inject fixed-volume aliquots of the reactor effluent gas stream into the GC carrier gas stream at pre-set time intervals (typically every 10 min). Quantification of gaseous products (including N2, H2, and unreacted N2O) was achieved by comparing peak areas against calibration curves generated using certified standard gas mixtures.

Liquid products were determined using colorimetric methods. For N2H4, the color reagent was prepared by dissolving 0.2 g of p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde in 10 mL of ethanol, followed by the addition of 1 mL of concentrated HCl. A 2 mL sample solution was mixed with 1 mL of the color reagent and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The absorbance was measured at 475 nm using a UV–vis spectrophotometer. NH4+ was determined using the indophenol blue method. Reagent A consisted of 1.4 wt.% phenol and 0.014 wt.% sodium nitroprusside (Na2[Fe(CN)5NO]), and Reagent B was 0.05 M sodium hypochlorite (NaClO). A 1 mL sample solution was mixed with 2.5 mL each of Reagents A and B, incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, and the absorbance was measured at 630.5 nm. NO2− concentration was measured using a commercially available nitrite colorimetric assay. Briefly, 4.5 mL of the sample was mixed with 0.5 mL of the chromogenic reagent, incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm. NO3− concentration was determined by adding 0.1 mL of 1 M HCl and 10 μL of 0.8 wt% sulfamic acid to 5 mL of the sample. The absorbance was measured at 220 nm (A220) and 275 nm (A275), and the corrected absorbance (A) was calculated as A = A220 − 2 × A275. The conditions of experiment carried out in 30 mL H cell were similar to those of GDE, except for the circulating electrolyte. Before electrocatalytic experiments, corresponding gas was bubbled into the electrolyte for at least 30 min to ensure electrolyte saturation. The scan rate of LSV tests was set at 100 mV s−1. EIS performance was detected at an open-circuit voltage with 5 mV alternating voltage amplitude in the frequency range of 106 to 0.1 Hz. All potentials were expressed relative to the RHE scale and were calculated using the following equation: E (vs RHE) = E (vs Ag/AgCl) + 0.197 + 0.0591 × pH.

The Faradaic efficiency (FE) calculation

The FE was calculated as follows:

where Q represents the quantity of electric transfer for the product; Qtotal denotes the total electric charge, which is calculated as the product of the average current (I) and the period of time (t); Ne- is the number of electrons required for 1 mole product formation or reactant consumption, with a value of 2 both for N2O to N2 and H2O to H2; F is Faradaic constant (96,485 C mol−1); n and η are moles and concentration of the product formation or reactant consumption; Vgas is the total volume of gas; P is atmospheric pressure (1.013 × 105 Pa); R is ideal gas constant (8.314 J mol–1 K–1); T is reaction temperature (298 K). Specifically, FEN2ORR was calculated based on the two-electron reduction of N2O to N2, using the amount of N2O consumed as the calculation basis. This approach was adopted because: (1) systematic product analysis confirmed N2 as the sole reduction product, with no other species (e.g., NH3 or N2H4) detected; and (2) quantification of N2O depletion was analytically more accurate and reliable than N2 measurement in the GC system.

The electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) measurement

The ECSA of catalyst was calculated using the relation:

where, S denotes the real surface area of a smooth metal electrode, which was 2.25 cm2 in this study. The roughness factor (Rf) was determined by the ratio of the double-layer capacitance (Cdl) of the electrode to the corresponding smooth metal electrode (Specific capacitance for carbon was reported as 27.50 μF cm−2). Therefore, Rf was given by

The Cdl was derived from the slope of the linear relationship between capacitive current and scan rate obtained from CV in a non-faradaic potential window (0.00–0.10 V vs RHE). CV curves were recorded at scan rates of 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 mV s−¹. The capacitive current (Δj = ja − jc) at 0.05 V (where ja and jc are the anodic and cathodic current densities, respectively) was plotted as a function of scan rate, and Cdl was determined from the slope of this plot, which corresponds to 2 × Cdl.

N2O decomposition rate calculation

The N2O decomposition rate was calculated as follows:

where nN2O is moles of N2O decomposition; mcat represents the total mass of catalyst, which is the sum of metal and MWCNT support; WHSV is the abbreviation for weight hourly space velocity of thermocatalysis, which is the ratio of gas flow rate to the mass of the catalyst.

In-situ DRIFTS measurements

In-situ DRIFTS was conducted using a Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrometer equipped with an MCT detector and a reflectance accessory designed for in situ electrochemical analysis, operated at an incidence angle of 60 degrees. A custom-built two-chamber electrochemical cell with a standard three-electrode configuration was used. Both the anode and cathode chambers were filled with 10 mL electrolyte. A 1 cm2 platinum sheet served as the counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl electrode was used as the reference. The working electrode was prepared by drop-casting 30 μL of catalyst ink onto a silicon crystal, followed by air drying. Prior to data acquisition, the MCT detector was cooled with liquid nitrogen for at least 30 min to ensure signal stability. N2ORR experiments were carried out under chronoamperometric conditions, and IR spectra were collected after 2 min of electrolysis in the range of 4000–1000 cm−1.

Computational fluid dynamics simulation

COMSOL Multiphysics 6.1 software was used for CFD simulation, employing CFD module, bubble flow and laminar flow physical field. In this simulation analysis, the following assumptions can be made: (1) The fluid flow form involved in the calculation is free flow, laminar flow; (2) The flow medium in the current assumption is a multiphase flow, which is a bubble flow in a discrete two-phase flow; (3) The system satisfies the transient hypothesis. The volume fraction represents the ratio of the volume occupied by N2O molecules to the total volume of the space, providing a quantitative measure of the N2O concentration within the given domain. The simulation uses laminar physical fields based on Navier-Stokes equations.

where, ρl is the density of liquid (kg m−3); ul is the liquid flow rate (m s−1); Φl is the volume fraction of the liquid; u is the fluid velocity vector (m s−1); p is fluid pressure (Pa); K is the viscous stress tensor (Pa); F is the volume force (N m−3); I represents the unit tensor; μl is the dynamic viscosity of a liquid (Pa s). At the interface between the bubble and liquid, due to different physical properties, there may be relative movement between the bubble and liquid, that is, the slip velocity, which is calculated according to the slip model, which selects the homogeneous flow in this simulation. The velocity relationship and force balance equations related to bubbles are as follows:

where, ρg is the density of the bubble (kg m−3); ug is the gas flow rate (m s−1); uslip is the relative velocity between the gas phase and the liquid phase, that is, the slip velocity (m s−1); Nρgφg represents the force of the bubble (N); mgl represents the force of gravity on the bubble (N); Φg is the volume fraction of the bubble; rhogeff is the effective density of the bubble.

Density functional theory calculations

The Vienna Ab Initio Package (VASP)74,75 has been utilized to conduct comprehensive DFT calculations within the framework of the generalized gradient approximation (GGA), employing the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) formulation76. To accurately depict the ionic cores and account for the valence electrons, we selected the projected augmented wave (PAW) potentials77,78, utilizing a plane wave basis set with a stringent kinetic energy cutoff of 400 eV. The Methfessel-Paxton smearing technique, with a width of 0.2 eV, was adopted to permit partial occupancies of the Kohn–Sham orbitals. The electronic self-consistency criterion was set at an energy change threshold of 10−5 eV. Furthermore, geometry optimization was considered converged once the force variation diminished to less than 0.02 eV/Å. To capture dispersion interactions, Grimme’s DFT-D3 methodology79 was incorporated into our calculations. From characterizations, Cu NPs and Ag NPs exhibited prominent (111) facet orientations, so that we simulated Cu(111) and Ag(111) facets to model the metallic behavior of Cu and Ag in the catalyst, respectively. Further, the simulated model of CuAg0.13 was reasonably simplified as Ag atoms anchored on the Cu(111) facets of Cu NPs, maintaining an Ag/Cu atomic ratio of 1/10, henceforth abbreviated as CuAg. The structural relaxation process employed a 2 × 2 × 1 k-point mesh for sampling the Brillouin zone, with the bottom two layers constrained and the upper layers free to relax. The adsorption energy (Eads) for adsorbate A was defined as

where, EA/surf refers to the total energy of the system with A adsorbed on the surface, Esurf is the energy of the pristine surface, and EA(g) denotes the energy of an isolated A molecule placed within a 20 Å side-length cubic periodic box. For the Brillouin zone sampling, a 1 × 1 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid was utilized80. The equation utilized for calculating the free energy of a gas-phase molecule or an adsorbate on a surface was given by

where G represents the free energy, E denotes the total energy, ZPE stands for the zero-point energy, T is the temperature set at 298.15 K (in kelvin), and S signifies the entropy.

Techno-economic assessment

A unified scenario has been proposed for electrocatalytic and thermocatalytic decomposition of N2O, assuming a caprolactam plant with a production capacity of 300,000 tons per year. The plant has a lifespan of 20 years and operates for 350 days each year73,81. As reported, the N2O concentration in the exhaust gas from caprolactam production is approximately 10 vol.%, with an emission factor of 9 kg N2O per ton of caprolactam82. Therefore, the amount of N2O generated is:

The decomposition cost of N2O is categorized into capital cost (CAPEX, primarily for initial equipment investment) and operating cost (OPEX, the expenses required for facility operation)81,83. The specific cost components of electrocatalysis and thermocatalysis were analyzed separately and are presented in Fig. S20. A renewable electricity price of 0.03 US$ kWh−1 was adopted84. Furthermore, a financial parameter of a 5% discount rate was also considered85. The levelized cost of N2O decomposition was calculated according to the following formula, where Rf represents the capital recovery factor72,81;

The techno-economic modeling and computational details are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Thompson, R. L. et al. Acceleration of global N2O emissions seen from two decades of atmospheric inversion. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 993–998 (2019).

W. W. M. Organisation. Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2022 (WMO, 2022).

Ravishankara, A. R., Daniel, J. S. & Portmann, R. W. Nitrous oxide (N2O): the dominant ozone-depleting substance emitted in the 21st century. Science 326, 123–125 (2009).

Prather, M. J. et al. Measuring and modeling the lifetime of nitrous oxide including its variability. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 5693–5705 (2015).

Davidson, E. A. & Winiwarter, W. Urgent abatement of industrial sources of nitrous oxide. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 599–601 (2023).

Reay, D. S. et al. Global agriculture and nitrous oxide emissions. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2, 410–416 (2012).

Tian, H. et al. A comprehensive quantification of global nitrous oxide sources and sinks. Nature 586, 248–256 (2020).

Richards, N. et al. Lowering the operating temperature of perovskite catalysts for N2O decomposition through control of preparation methods. ACS Catal. 10, 5430–5442 (2020).

Abu-Zied, B. M., Schwieger, W. & Unger, A. Nitrous oxide decomposition over transition metal exchanged ZSM-5 zeolites prepared by the solid-state ion-exchange method. Appl. Catal. B 84, 277–288 (2008).

You, Y. et al. Enhancement of N2O decomposition performance by N2O pretreatment over Ce-Co-O catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 347, 184–192 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. Ce-Pr Co-doped Co3O4 with enriched oxygen vacancies for the efficient decomposition of N2O. ChemCatChem 0, e202401060 (2024).

You, Y. et al. Low-temperature selective catalytic reduction of N2O by CO over Fe-ZSM-5 catalysts in the presence of O2. J. Hazard. Mater. 383, 121117 (2020).

Cheng, J. et al. N2O catalytic decomposition and NH3-SCR coupling reactions over Fe-SSZ−13 catalyst: mechanisms and interactions unraveling via experiments and DFT calculations. ACS Catal. 13, 934–947 (2023).

Wu, Y., Sun, Y., Wu, X., Wang, H. & Wu, Z. Reversed charge transfer enables dual active sites on Ir/hBN for synergistic N2O valorization and propane selective oxidation. ACS Catal. 14, 13520–13530 (2024).

Sun, Y. et al. High performance iridium loaded on natural halloysite nanotubes for CO-SCR reaction. Fuel 357, 129938 (2024).

Konsolakis, M. Recent advances on nitrous oxide (N2O) decomposition over non-noble-metal oxide catalysts: catalytic performance, mechanistic considerations, and surface chemistry aspects. ACS Catal. 5, 6397–6421 (2015).

Kijlstra, W. S. et al. Inhibiting and deactivating effects of water on the selective catalytic reduction of nitric oxide with ammonia over MnOx/ Al2O3. Appl. Catal. B 7, 337–357 (1996).

Lian, D. et al. Promising selective catalytic reduction of NOx by CO: status, Challenges, and perspective. Chem. Eng. J. 496, 154242 (2024).

Yun, J. G. et al. Effect of the oxygen concentration and temperature on thermal decomposition of N2O in an inert gas. ACS Omega 6, 30983–30988 (2021).

Kim, K. et al. Systematic approach to designing a highly efficient core–shell electrocatalyst for N2O reduction. ACS Catal. 11, 15089–15097 (2021).

Li, Z., Wu, Y., Wang, H., Wu, Z. & Wu, X. High-efficiency electrocatalytic reduction of N2O with single-atom Cu supported on nitrogen-doped carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 8976–8987 (2024).

Gómez, R. & Weaver, M. J. Reduction of nitrous oxide on iridium single-crystal electrodes. Langmuir 18, 4426–4432 (2002).

Deeba, R., Molton, F., Chardon-Noblat, S. & Costentin, C. Effective homogeneous catalysis of electrochemical reduction of nitrous oxide to dinitrogen at rhenium carbonyl catalysts. ACS Catal. 11, 6099–6103 (2021).

Rapson, T. D. et al. Conversion of nitrous oxide to nitrogen by cobalt-substituted myoglobin. RSC Adv. 5, 89003–89008 (2015).

Lei, S. et al. Simultaneous generation of electricity, ethylene and decomposition of nitrous oxide via protonic ceramic fuel cell membrane reactor. J. Energy Chem. 77, 359–368 (2023).

Silambarasan, P. & Moon, I. S. Enhancing the mediated electrochemical reduction process combined with developed liquid-gas electrochemical flow sensors for sustainable N2O removal at room temperature. Environ. Res. 204, 111912 (2022).

Kanazawa, K., Yamamura, H., Nakayama, M. & Ogura, K. Electrochemical reduction of nitrous oxide by the protons transported through polyelectrolyte-coated porous glass. J. Electroanal. Chem. 521, 127–131 (2002).

Kunerth, W. Solubility of CO2 and N2O in certain solvents. Phys. Rev. 19, 512–524 (1922).

Hernandez-Aldave, S. & Andreoli, E. Fundamentals of gas diffusion electrodes and electrolysers for carbon dioxide utilisation: challenges and opportunities. Catalysts 10, 713 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Porous bilayer electrode-guided gas diffusion for enhanced CO2 electrochemical reduction. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2, 2100083 (2021).

Burdyny, T. & Smith, W. A. CO2 reduction on gas-diffusion electrodes and why catalytic performance must be assessed at commercially-relevant conditions. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 1442–1453 (2019).

Xing, Z., Hu, L., Ripatti, D. S., Hu, X. & Feng, X. Enhancing carbon dioxide gas-diffusion electrolysis by creating a hydrophobic catalyst microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 12, 136 (2021).

Wu, D. et al. Direct eight-electron N2O electroreduction to NH3 enabled by an Fe double-atom catalyst. Nano Lett. 24, 8502–8509 (2024).

Stanley, J. S., Wang, X. S. & Yang, J. Y. Selective electrocatalytic reduction of nitrous oxide to dinitrogen with an iron porphyrin complex. ACS Catal. 13, 12617–12622 (2023).

Niu, Z.-Z., Chi, L.-P., Liu, R., Chen, Z. & Gao, M.-R. Rigorous assessment of CO2 electroreduction products in a flow cell. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 4169–4176 (2021).

Shen, Q. et al. Oxidation coupling of terminal alkynes over CuPd bimetallic alloy enhanced by optimized charge transfer and alloy structure. Chem. Eng. J. 470, 144193 (2023).

Kim, C. et al. Alloy nanocatalysts for the electrochemical oxygen reduction (ORR) and the direct electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction reaction (CO2RR). Adv. Mater. 31, 1805617 (2019).

Wu, X. et al. Contrasting capability of single atom palladium for thermocatalytic versus electrocatalytic nitrate reduction reaction. ACS Catal. 13, 6804–6812 (2023).

Luo, W. et al. Single-atom and bimetallic nanoalloy supported on nanotubes as a bifunctional electrocatalyst for ultrahigh-current-density overall water splitting. ACS Catal. 12, 1167–1179 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Electrochemical reduction of CO2 toward C2 valuables on Cu@Ag core-shell tandem catalyst with tunable shell thickness. Small 17, 2102293 (2021).

Liu, Y., Ma, J., Huang, S., Niu, S. & Gao, S. Highly dispersed copper-iron nanoalloy enhanced electrocatalytic reduction coupled with plasma oxidation for ammonia synthesis from ubiquitous air and water. Nano Energy 117, 108840 (2023).

Su, W., Guo, W. & Fan, Y. CuAg bimetallic catalysts derived from an Ag-anchored Cu-based metal–organic framework for CO2 electroreduction to ethanol. Chem. Eng. J. 477, 147204 (2023).

Lv, X. et al. Electron-deficient Cu sites on Cu3Ag1 catalyst promoting CO2 electroreduction to alcohols. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2001987 (2020).

Ko, B. H., Hasa, B., Shin, H., Zhao, Y. & Jiao, F. Electrochemical reduction of gaseous nitrogen oxides on transition metals at ambient conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 1258–1266 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. A novel sustainable and self-sufficient biotechnological strategy for directly transforming sewage sludge into high-value liquid biochemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 12520–12531 (2024).

Silambarasan, P., Ramu, A. G., Govarthanan, M., Jung, K. D. & Moon, I. S. Enhanced sustainable electro-generation of a Ni (I) homogeneous electro-catalyst at a silver solid amalgam electrode for the continuous degradation of N2O, NO, DCM, and CB pollutants. J. Hazard. Mater. 420, 126564 (2021).

Xue, L., Zhang, C., He, H. & Teraoka, Y. Catalytic decomposition of N2O over CeO2 promoted Co3O4 spinel catalyst. Appl. Catal. B 75, 167–174 (2007).

Xue, L., Zhang, C., He, H. & Teraoka, Y. Promotion effect of residual K on the decomposition of N2O over cobalt–cerium mixed oxide catalyst. Catal. Today 126, 449–455 (2007).

Xue, L., He, H., Liu, C., Zhang, C. & Zhang, B. Promotion effects and mechanism of alkali metals and alkaline earth metals on cobalt−cerium composite oxide catalysts for N2O decomposition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 890–895 (2009).

Zhao, X. et al. Rhodium supported on silica-stabilized alumina for catalytic decomposition of N2O. Catal. Lett. 141, 128–135 (2010).

Abu-Zied, B., Bawaked, S., Kosa, S. & Schwieger, W. Rare earth-promoted nickel oxide nanoparticles as catalysts for N2O direct decomposition. Catalysts 6, 70 (2016).

Yentekakis, I. V. et al. Stabilization of catalyst particles against sintering on oxide supports with high oxygen ion lability exemplified by Ir-catalysed decomposition of N2O. Appl. Catal. B 192, 357–364 (2016).

Cho, C.-M., Nunotani, N. & Imanaka, N. Direct decomposition of N2O over C-type cubic Yb2O3-Co3O4 catalysts. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 92, 1148–1153 (2019).

Cho, C.-M., Nunotani, N. & Imanaka, N. Effect of oxygen vacancies on direct N2O decomposition over ZrO2-Y2O3 catalysts. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 7, 518–523 (2019).

Jabłońska, M. et al. Understanding the origins of N2O decomposition activity in Mn(Fe)CoAlO hydrotalcite derived mixed metal oxides. Appl. Catal. B 243, 66–75 (2019).

Xiong, S. et al. Balance between reducibility and N2O adsorption capacity for the N2O decomposition: CuxCoy catalysts as an example. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 10379–10386 (2019).

Zhu, H., Li, Y. & Zheng, X. In-situ DRIFTS study of CeO2 supported Rh catalysts for N2O decomposition. Appl. Catal. A 571, 89–95 (2019).

Basahel, S. N., Mokhtar, M., Ali, T. T. & Narasimharao, K. Porous Fe2O3-ZrO2 and NiO-ZrO2 nanocomposites for catalytic N2O decomposition. Catal. Today 348, 166–176 (2020).

Hinokuma, S., Iwasa, T., Kon, Y., Taketsugu, T. & Sato, K. Effects of support materials and Ir loading on catalytic N2O decomposition properties. Catal. Commun. 149, 106208 (2021).

Zabilskiy, M., Arčon, I., Djinović, P., Tchernychova, E. & Pintar, A. In-situ XAS study of catalytic N2O decomposition Over CuO/CeO2 catalysts. ChemCatChem 13, 1814–1823 (2021).

Jing, Y. et al. Catalytic decomposition of N2O in the presence of O2 through Redox of Rh Oxide in a RhOx/ZrO2 catalyst. ACS Catal. 12, 6325–6333 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. Strong electronic orbit coupling between cobalt and single-atom praseodymium for boosted nitrous oxide decomposition on Co3O4 catalyst. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 16325–16335 (2022).

Umegaki, T., Dobashi, M., Komuro, T. & Kojima, Y. Fabrication of copper supported porous silica–alumina hollow spheres for catalytic decomposition of nitrous oxide. Super. J. Chem. 46, 11166–11173 (2022).

Choi, S., Bok Nam, K., Phil Ha, H. & Wook Kwon, D. Enhancement of catalytic N2O decomposition by modulating oxygen vacancies over Cu/Ce1-XYX catalysts. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 121, 462–471 (2023).

Li, Y., Wang, X. & Shi, C. The catalytic performance of Ba-Ce-Cu catalysts for N2O decomposition. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 109970 (2023).

Xie, S., Kim, D., Ye, K., Tetard, L. & Liu, F. Regulating local coordination environment of rhodium single atoms in Rh/CeO2 catalysts for N2O decomposition. J. Rare Earths 41, 941–951 (2023).

Parres-Esclapez, S. et al. Study by isotopic gases and in situ spectroscopies (DRIFTS, XPS and Raman) of the N2O decomposition mechanism on Rh/CeO2 and Rh/γ-Al2O3 catalysts. J. Catal. 276, 390–401 (2010).

Xiao, L. et al. Identification of Cu(111) as superior active sites for electrocatalytic NO reduction to NH3 with high single-pass conversion efficiency. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202319135 (2024).

Ren, Y. et al. Microscopic-level insights into the mechanism of enhanced NH3 synthesis in plasma-enabled cascade N2 oxidation–electroreduction system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 10193–10200 (2022).

Huang, J. et al. Highly selective electroreduction of CO2 to CH4 on Cu–Pd alloy catalyst: the role of palladium-adsorbed hydrogen species and blocking effect. Adv. Sci. 12, 2417247 (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Electronic metal-support interaction modulates Cu electronic structures for CO2 electroreduction to desired products. Nat. Commun. 16, 1956 (2025).

Leow, W. R. et al. Chloride-mediated selective electrosynthesis of ethylene and propylene oxides at high current density. Science 368, 1228–1233 (2020).

Wang, M. et al. Can sustainable ammonia synthesis pathways compete with fossil-fuel based Haber–Bosch processes?. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 2535–2548 (2021).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Zhang, X. et al. Near-infrared photon-triggered CH4-to-CH3OH conversion over plasmonic oxyselenides. Nat. Commun. 16, 7612 (2025).

Daiyan, R. et al. Nitrate reduction to ammonium: from CuO defect engineering to waste NOx-to-NH3 economic feasibility. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 3588–3598 (2021).

Wu, X. et al. Progress and challenges in nitrous oxide decomposition and valorization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 8379–8423 (2024).

Lum, Y. et al. Tuning OH binding energy enables selective electrochemical oxidation of ethylene to ethylene glycol. Nat. Catal. 3, 14–22 (2020).

Qi, J. et al. Energy-saving and product-oriented hydrogen peroxide electrosynthesis enabled by electrochemistry pairing and product engineering. Nat. Commun. 14, 6263 (2023).

Verma, S., Kim, B., Jhong, H., Ma, S. C. & Kenis, P. J. A. A gross-margin model for defining technoeconomic benchmarks in the electroreduction of CO2. ChemSusChem 9, 1972–1979 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 52341001, 52400098, 52370120), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LZ25B070003), National Key R&D Program of China (2025YFE0207100).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X. W. and Z. L. designed research; Z.L. performed research; Z.L. and J.Y. analyzed data; Z.L., J.Y., Z.W., and X.W. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Feng Jiao and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Yuan, J., Wu, Z. et al. High single-pass conversion of nitrous oxide to dinitrogen in gas-diffusion-electrolyzer. Nat Commun 17, 552 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67244-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67244-z