Abstract

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) hydrolysis is a critical step in secondary sulfate formation, which significantly affects air quality and climate change. Since the 1980s, debate has persisted over whether this reaction occurs mainly at the air–water interface or in the bulk phase. In this study, we investigate SO2 hydrolysis in heterogeneous systems using molecular dynamics simulations that are driven by a deep neural network potential with ab initio accuracy. In previous studies, rapid interfacial reactions have been proposed to account for the unexpectedly high SO2 uptake coefficients. In contrast, our results reproduce the observed uptake coefficients but show that interfacial hydrolysis contributes only 1%. We find that hydrolysis is accelerated in the bulk phase, where the denser hydrogen-bond network enhances SO2 electrophilicity and lowers the reaction barrier. The theoretical simulations in this work help to improve the understanding of aqueous sulfate aerosol formation and microdroplet chemistry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

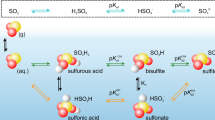

Sulfur dioxide (SO2), which is emitted in large quantities from fossil fuel combustion, can produce secondary sulfate that significantly impacts air quality and climate change1,2,3. Aqueous-phase reactive uptake of SO2 is an important atmospheric removal pathway4. Textbook descriptions typically assume that SO2 undergoes bulk-phase chemistry that involves adsorption, solvation and rapid hydrolysis to form HSO3⁻ or SO32⁻, which are subsequently oxidized to sulfate. Such treatment could neglect possible interfacial processes4. Recently, attention has shifted to processes that occur in deliquesced aerosol water, particularly because sulfate concentrations become very high during haze events. Several studies that have been published in high-impact journals have reached different conclusions. Liu et al.5 suggested that HSO3⁻, which is hydrolyzed in the bulk phase of aerosol water, is the principal precursor of sulfate. Wang et al.6 proposed that SO2 hydrolysis at deliquesced aerosol surfaces accelerates oxidation. Similarly, Liu et al.7. suggested that hydrolysis products (HSO3⁻/SO32⁻) at aerosol surfaces contribute substantially to sulfate formation. Although previous studies have focused primarily on oxidation, hydrolysis is the key mechanistic step that produces HSO3⁻ and SO32⁻. The rate and spatial distribution of hydrolysis may affect the availability of oxidizable substrates and thereby modulate sulfate production. Despite its importance, SO2 hydrolysis remains poorly understood.

The debate over whether SO2 hydrolysis is dominated by interfacial processes or bulk-phase reactions dates back to the 1980s. Hydrolysis-driven uptake involves a sequence of steps, including transfer to the air‒water interface, surface reactions, solvation, and subsequent reactions in the bulk phase. This process is typically assessed using the uptake coefficient (γ), which quantifies the fraction of SO2 molecules that are removed from the gas phase upon collision with the liquid phase. Notably, the observed γ values often far exceed the theoretical upper limit that is predicted by bulk-phase kinetics using measured bulk hydrolysis rate constants8,9,10,11. To address this discrepancy, a rapid surface reaction mechanism was proposed8. However, key physical and chemical properties of SO2 remain poorly characterized, particularly the hydrolysis rate constants at the interface and in the bulk phase. Experimental methods are inherently limited in terms of separating hydrolysis from solvation and distinguishing interfacial from bulk-phase contributions. These limitations make examining the surface-reaction hypothesis and understanding the contribution of SO2 interfacial hydrolysis to uptake difficult.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can overcome these limitations and provide a powerful tool for exploring microscopic mechanisms12. However, current simulation methods still face challenges in describing hydrolysis-driven uptake in large, heterogeneous systems. Classical force field (FF) methods are computationally efficient but rely on empirical potentials. They fail to capture electronic-level changes, and simulations are confined to physical processes13,14,15. Ab initio MD (AIMD), on the other hand, provides an accurate chemical description of SO2 interactions16,17,18. However, its high computational cost limits system size and simulation time, thus preventing realistic studies of hydrolysis in heterogeneous systems. Therefore, to fully understand the reactive uptake, developing a simulation method that balances accuracy and efficiency is essential. All the chemical and physical processes, particularly hydrolysis in heterogeneous systems, need to be captured by this method.

To overcome these limitations, the neural network potential (NNP) framework introduced by Behler and Parrinello19 has emerged as a powerful route for constructing accurate interatomic potential energy surfaces. When trained on ab initio reference data, NNPs can reproduce the accuracy of such calculations while retaining the efficiency of classical FFs, thereby enabling long-time reactive molecular dynamics simulations. However, achieving reliable NNP performance requires training datasets that adequately cover the relevant chemical space, including rare transition-state (TS) configurations. To address this challenge, enhanced sampling techniques and active learning schemes have proven effective in exploring diverse configurational landscapes of complex systems20,21. Among these, the state-of-the-art on-the-fly probability enhanced sampling (OPES)22,23 has demonstrated remarkable capability in promoting reactive events within accessible timescales, while simultaneously enabling accurate thermodynamic and kinetic characterizations.

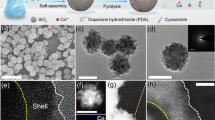

In this work, we construct an NNP using the Deep Potential Smooth Edition scheme24. Representative training configurations are efficiently generated through enhanced sampling combined with active learning. The dataset is labeled at the B3LYP25,26 hybrid density functional theory (DFT) level27,28, ensuring an accurate description of SO2 hydrolysis (Fig. S1). Leveraging this NNP, we carry out extensive molecular dynamics simulations to determine the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of SO2 adsorption, solvation, and hydrolysis in microdroplets (Fig. 1). The resulting uptake coefficient agrees well with experimental measurements, revealing that interfacial processes account for only ~1% of the reactive uptake of SO2. The high measured uptake coefficients may instead be explained by the underestimated bulk hydrolysis rate. We further demonstrate that hydrolysis at the interface is slower than that in the bulk phase, because of a significant reduction in SO2 electrophilicity that is caused by the weaker hydrogen-bond network. These results provide insight into the reactive uptake of SO2 and advance our understanding of its interfacial reactivity.

An SO2 molecule from the gas phase (gas) first adsorbs at the air–water interface (sur.). It may then dissolve into either the bulk aqueous phase (liq.) and undergo hydrolysis there or hydrolyze directly at the interface. Interfacial hydrolysis contributes minimally (approximately 1%) to the overall reactive uptake (quantified by the uptake coefficient, γ), whereas bulk hydrolysis accounts for approximately 99%. The hydrolysis products include HSO3⁻, SO32⁻, and H2SO3; only HSO3⁻ is shown for illustrative purposes.

Results

To quantify the reactive uptake of SO2, the simulations need to capture the full sequence of events, from gas adsorption and solvation to chemical hydrolysis. We conducted comprehensive molecular dynamics simulations across the entire uptake pathway and then extracted thermodynamic and kinetic parameters for the reactive uptake kinetic model12. The model provides a potential bridge between molecular-level interactions and macroscopic reactivity, thereby enabling the quantification of interfacial and bulk-phase processes in the overall uptake.

Adsorption and solvation process

First, the interfacial adsorption and solvation of SO2 were characterized. Adsorption corresponds to temporary residence at the surface, whereas solvation involves penetration into the liquid bulk. To quantify their thermodynamic properties, we computed the free energy profile of SO2 along the surface normal, together with the water density profile (Fig. 2). Classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with umbrella sampling29,30 were employed. The interface was defined as the region where the water density decreased from 90% to 10% of its bulk value, which corresponded to L ≈ 3 Å (13–16 Å along the Z-axis). Further analysis of the interfacial width L is provided in the Supplementary Information (SI). We further defined the difference in free energy between the gas and bulk regions as the solvation free energy ∆Fs31 and the barrier for SO2 transfer from the bulk phase to the interface as ∆Fb. The free-energy profile reveals a pronounced minimum at the interface, which corresponds to an interfacial adsorption free energy of ∆Fa =−3.2 kcal mol−1. This value highlights the hydrophilic character of SO2, consistent with previous studies13,14.

The free energy profile (red line) is shown with the standard deviation from the bootstrapping results (gray shaded region). The water density profile (gray dashed line) is fitted with a hyperbolic tangent function (blue line). Both profiles are plotted against the Z-distance between the center of mass (COM) of SO2 and the water slab. ∆Fa, ∆Fs and ∆Fb represent the adsorption free energy, solvation free energy, and desolvation free energy barrier, respectively. The interfacial region is indicated by the space between the black dashed lines, whereas the Gibbs dividing surface (GDS) is marked by the vertical black line at the midpoint of the fitted density profile. liq. denotes the bulk liquid phase, and sur. denotes the interfacial region. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Equilibrium surface partitioning constant

The equilibrium surface partitioning constant, b’, is defined as the ratio of the interfacial concentration \({\left[X\right]}_{{\mbox{sur}}}\) (mol m−2) to the gas phase concentration [X]gas (mol m−3), in units of length.

Here, \({\beta }_{{{\rm{mol}}}}=1/{{\rm{R}}}T\), with units of mol J−1. Using ∆Fa = −3.2 kcal mol−1 and an interfacial width \(L=3\)Å, b’ is estimated to be approximately 670 Å.

Solubility

The solubility of SO2, which is in equilibrium between a dilute aqueous solution of concentration c (mol L−1) and a gas phase at partial pressure p (Pa), is described by Henry’s law constant H. This constant is related to the solvation free energy ∆Fs:

The calculated ∆Fs is −2.3 kcal mol−1, which yields H=\(2.0\) M atm−1. \({\Delta F}_{{\mbox{s}}}\) aligns well with the experimental value of (−2.0 ± 0.3 kcal mol−1)32.

Mass accommodation

The mass accommodation coefficient ɑ, which is defined as the probability that a gas molecule that collides with the liquid surface enters the bulk phase in the absence of surface reactions12, is often used to characterize the overall transfer process. It is estimated from ∆Fs, ∆Fb and the sticking coefficient S, which indicates the probability of interfacial accommodation upon collision.

Using the calculated ∆Fb = 0.36 kcal mol−1 and S ≈ 1 14, we obtained ɑ = 0.96. This value is close to 1, which is similar to the results from classical MD simulations of other gas-phase species at room temperature12,33,34. This implies that SO2 is efficiently transferred into the bulk liquid.

Hydration network of SO2

SO2 is efficiently transferred from the gas phase into the bulk liquid and may accumulate at the interface. The microscopic structures of SO2 hydration complexes, both at the interface and in the bulk phase, therefore require further investigation. We employed an NNP model with ab initio accuracy to characterize the SO2·(H2O)n complexes. This approach overcomes the limitations of classical force field models, which cannot reliably capture the resonance structures of SO2 that have been revealed by ab initio calculations13.

The hydrogen bonds that involve the oxygen of SO2 (Os) and the S···Ow coordination (Ow denotes the oxygen atom in H2O) were examined through multiple independent simulations. Hydrogen bonds are defined by Ow-Os distances < 3.5 Å and H-Ow···Os angles <30°, whereas S···Ow interactions are identified by S-Ow distances< 3.0 Å\(.\) Analyses were conducted on 10 independent 500 ps production trajectories after 500 ps of equilibrium.

The mean number of hydrogen bonds per SO2 molecule at the air‒water interface was 0.86, whereas it was 0.99 in the bulk. Similarly, the mean number of S···Ow coordinations at the interface was only 0.32, whereas it was 0.81 in the bulk. Multiply bonded complexes also formed predominantly in the bulk (Fig. 3a,b). These results suggest that the hydrogen bonding network couples with S···Ow interactions and influences their formation and stability. Owing to the multiple binding sites of SO2 with surrounding water molecules, more than 20 distinct SO2-H2O complexes were observed. The representative configurations (complexes 0–7) with probabilities that exceeded 4% at either the interface or in the bulk phase are shown in Fig. 3c. Their distributions are shown in Fig. 3d. At the interface, complex 1 was predominant (34%) and was characterized primarily by hydrogen bond interactions rather than S···Ow coordination. These findings are consistent with previous spectroscopic evidence35. The isolated SO2 molecule (complex 0) was the second most common configuration (26%) at the interface. In the bulk, complex 3 was predominant and featured both S···Ow coordination and hydrogen bonding, whereas the isolated SO2 molecule (complex 0) accounted for only 16%. Overall, these results demonstrate that SO2-H2O interactions are stronger, more diverse, and better stabilized in the bulk because of the dense and cooperative hydrogen bonding network.

a Comparison of the probability distributions of the hydrogen bond counts between SO2 and H2O at the air–water interface (red, sur.) and in the bulk phase (blue, bulk). The bulk/sur. ratio represents the bulk-phase value divided by the interface value (purple line). b Comparison of the probability distributions of the S···Ow bond counts between SO2 and H2O at the air–water interface (red) and in the bulk phase (blue). c Representative structures of SO2·(H2O)n complexes with probabilities greater than 4%. Key atom names are labeled in complexes 0 and 1. Red lines represent hydrogen bonds, and blue lines indicate S···Ow interactions. d Probabilities of the identified complexes in Panel (c) at the air–water interface and in the bulk phase. OT denotes other complexes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Thermodynamics and kinetics of hydrolysis

Hydrolysis, unlike adsorption and solvation, introduces a chemical transformation into the reactive uptake of SO2. The free energy surfaces (FESs) for SO2 hydrolysis, both at the air–water interface and in the bulk phase, are presented in Fig. 4a, b. The overall FES topologies are similar and consist of four basins: SO2 (R), HSO3⁻ (P), SO32⁻ (P1), and H2SO3 (P2). HSO3⁻ and SO32⁻ are the most stable products, with free energies that differ by less than 1 kcal mol−1 in in terms of chemical accuracy. In contrast, H2SO3 formation is thermodynamically unfavorable and unlikely to accumulate under aqueous conditions. These results are consistent with those of previous theoretical and experimental studies36,37,38, which indicate that HSO3⁻ and SO32⁻ are the major hydrolysis products. Notably, compared with the bulk phase, the SO2 reactant (R) on the interfacial FES is shifted toward lower S-O coordination numbers. This shift reflects weaker hydrogen-bonding interactions with the surrounding water network, which is consistent with the hydration complex distribution analysis in Fig. 3.

a, b Free energy surfaces (FESs) for SO2 hydrolysis as functions of the S-O coordination number (S-O CN) and the Voronoi-based collective variable (sa) for the surface (a) and bulk phase (b). The minimum free energy pathways (R → P → P1) are highlighted in red (surface) and blue (bulk). The dashed lines indicate energy levels of −5, 5, 15, 17, 20, and 22 kJ mol−1. Representative snapshots of key species are shown as insets: R (SO2), R’ (prereactive state), TS (transition state), P (HSO3⁻), P1 (SO32⁻), and P2 (H2SO3). c Free energy profiles along the MFEPs at the surface (red) and in the bulk (blue). Shaded regions indicate statistical uncertainty from block averaging. d Cumulative probability distributions of hydrolysis times (black lines) that are fitted by first-order Poisson models (colored lines). The blue line corresponds to bulk hydrolysis (kb =1.7 × 107 s−1), and the red line corresponds to interfacial hydrolysis (ks = 9.7 × 105 s−1). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests yielded p values of 0.67 (surface) and 0.93 (bulk), thus supporting first-order kinetics. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The minimum free energy pathways (MFEPs) from R → P → P1, which represent the most favorable reaction pathways, are also depicted in Fig. 4a, b. The corresponding free energy profiles (Fig. 4c) show that hydrolysis at the air–water interface has a higher energy barrier and yields a less stable product state than hydrolysis in the bulk phase does. To assess the kinetic implications, rate calculations were performed for both environments. The conversion of SO2 to HSO3⁻ (R → P), which corresponds to the reaction SO2 + 2H2O → HSO3⁻ + H3O⁺, constitutes the first and rate-limiting step of hydrolysis and thus controls the kinetics of reactive SO2 uptake. Kinetic calculations indicate that the hydrolysis rate in the bulk phase, kb = 1.7×107 s−1, is 5 times faster than the reported experimental value (3.4×106 s−1)39. However, this rate has not been independently measured, as solvation and hydrolysis cannot be separated experimentally. In comparison, the hydrolysis rate at the air‒water interface, ks = 9.7×105 s−1, is approximately 15 times slower than that in the bulk phase (Fig. 4d). This trend is consistent with recent theoretical studies that also report slower interfacial hydrolysis compared with the bulk phase40,41,42. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of long-range interactions in interfacial systems. The analyses, including orientational profile and cutoff-sensitivity examinations, show that the NNP description is converged with respect to these effects43 (see the SI for details). Nonetheless, systems that exhibit stronger long-range contributions may require explicit electrostatics43,44,45.

Hydrolysis mechanism

The MFEPs on the FESs reveal a concerted proton-coupled pathway for SO2 hydrolysis. This pathway is predominant in both interfacial and bulk aqueous environments, as discussed below. Less frequent stepwise ionic alternatives are detailed in the SI.

The hydrolysis reaction proceeds through four key stages along the MFEP: initial reactant (R), prereactive state (R’), transition state (TS), and product (P) (Fig. 5a). Key structural evolutions, including bond length variations and hydrogen bond counts, are illustrated in Fig. 5b–d. In the reactant stage (R), SO2 is loosely coordinated to multiple water molecules through weak hydrogen bonds, with an S–Ow distance of approximately 3.0 Å. The surrounding hydrogen-bond network is relatively sparse and disordered. In the prereactive state (R’), this network reorganizes and becomes denser. This shortens the S–Ow bonds to 2.0‒2.3 Å and slightly elongates the S–Os bonds, thus signaling the onset of a nucleophilic attack. In the transition state (TS), proton transfer occurs via at least two bridging water molecules. The Ow–H bond elongates beyond 1.2 Å. The TS is significantly stabilized by a dense, cooperative hydrogen-bond network that supports bond breaking and formation. In the final product state (P), HSO3⁻ and H3O+ are formed. The hydrogen-bond network around the HSO3⁻ anion becomes denser and more ordered, thus energetically stabilizing the product. The H3O+ ion can then migrate from the reaction site by proton hopping along the extended hydrogen-bond network.

a Representative snapshots that were obtained from OPES-biased simulations. The snapshots depict key stages of the hydrolysis process: the reactant complex (R), prereactive state (R’), transition state (TS), and product (P). Red lines represent hydrogen bonds. Key bond distances (gray lines) are labeled in angstroms (Å). b Time evolution of key bond distances during hydrolysis, including the \({{{\rm{S}}}-{{\rm{O}}}_{{\rm{w}}}\left(\right.}_{({{{\rm{SO}}}}_{2})}{{\rm{S}}}\cdots {{{\rm{O}}}}_{({{{\rm{H}}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}})},{{\rm{blue}}}\left)\right.\) and \(\,{{{{\rm{O}}}}_{{{\rm{w}}}}-{{\rm{H}}}\left(\right.}_{({{\rm{H}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}})}{{\rm{O}}}\cdots {{{\rm{H}}}}_{({{\rm{H}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}})},{{\rm{orange}}}\left)\right.\) bonds. c Time evolution of the number of hydrogen bonds formed by the oxygen atom of SO2 (Os, green). d Time evolution of the bond distance between the sulfur atom of SO2 and its oxygen atom (Os) during hydrolysis (purple). In Panels (c) and (d), the shaded lines represent instantaneous values, whereas the solid lines represent smoothed Savitzky-Golay curves. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Analysis of the hydrolysis mechanism highlights the critical role of a well-developed hydrogen-bond network. Hydrogen bonds have been shown to lower the energy of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO)16,46,47. In the hydrolysis of SO2, the LUMO is primarily localized on the SO2 molecule. The formation of additional hydrogen bonds around the SO2 molecule lengthens the S–Os bonds and enhances their vibrational amplitude16. These changes thereby lower the LUMO energy, increase the electrophilicity of sulfur, and promote nucleophilic attack by H2O.

Studies have suggested that compared with the bulk phase, dangling OH groups at the water surface can directly form hydrogen bonds without the need to break, thereby lowering the activation energy barrier48,49,50. However, this viewpoint has certain limitations. These studies typically used oversimplified models and focused on organic‒water interfaces, which may not be directly applicable to air‒water interfaces. In the context of reactive uptake, the hydrogen bond network undergoes significant disruption and reorganization during the adsorption and solvation of SO2, even before the onset of hydrolysis. Our investigation of SO2 hydration complexes revealed that the hydrogen bond network is denser and more stable in the bulk phase. This strengthens interactions with SO2 and increases S‒Os bond vibrations. As a result, electrophilicity increases, the LUMO energy decreases, and the TSs become more stable. These factors together lead to a higher hydrolysis rate in the bulk phase. In contrast, the less structured hydrogen bond network at the interface limits these effects, thereby leading to a slower hydrolysis rate. This notion is further supported by findings from previous studies51,52. Our OPES flooding simulations provided rate constants without relying on transition state theory and revealed a slower interfacial rate because of the weaker hydrogen bond network. This conclusion complements recent studies by Kumar et al53. and Ma et al54., who emphasized the roles of solvent reorganization and nonequilibrium dynamical coupling in modulating reactivity.

Kinetic model of hydrolysis uptake

The reactive uptake of SO2 is often described by the resistor model. In this framework, a gas molecule first accommodates at the surface with probability ɑ and subsequently diffuses into the bulk phase, where the chemical reaction occurs. The reaction diffusion length is defined as \({l}_{{\mbox{D}}}=\sqrt{D/{k}_{{\mbox{b}}}}\), where D is the diffusion coefficient55 of SO2 and \({k}_{{\mbox{b}}}\) is the bulk hydrolysis rate constant. \({l}_{{\mbox{D}}}\) must be sufficiently long for equilibrium between the gas and the liquid phases to be reached. Given the hydrolysis rate constant that we calculated above, we estimated lD ≈ 10 \({\mbox{nm}}\), which is large enough relative to the interfacial width of 3 Å. The reactive uptake coefficient, γ, can be estimated from56,57

where 1/Γb is the bulk-phase resistance, 1/Γs is the interfacial resistance, ω is the thermal velocity, R is the gas constant, T is the temperature, Rp is the mean particle radius and q is the reactodiffusive parameter. On the basis of our simulations (Table S1), we estimated γ to be approximately 0.10, which aligns well with the experimental measurements (\({\gamma }_{{\mbox{meas}}}=0.03-0.13\))8,9,10,11. Notably, earlier studies struggled to reconcile γmeas > 0.03 with model predictions. If the bulk hydrolysis rate that was reported by Eigen et al39. were to be adopted, the resulting upper limit for γ would be ~0.03. Accordingly, Jayne et al8. proposed that rapid interfacial reactions could account for this discrepancy. However, our analysis suggests that an underestimation of the bulk hydrolysis rate, rather than the interfacial contribution, is the primary factor. We further roughly estimate the interfacial contribution using the ratio (1−γb/γ), where γb is the uptake coefficient that is calculated by setting the interfacial resistance 1/Γs to infinity. This analysis estimates that interfacial processes account for only ~1% of the overall SO2 reactive uptake.

Our reaction–diffusion kinetic analysis revealed a weak size dependence of the SO2 hydrolysis uptake coefficient γ. For droplets from 50 nm to 10 μm, γ varies only slightly (0.08–0.10). This variation is driven by the term coth(q)−1/q, where q = Rp/\({l}_{{\mbox{D}}}\). With a reaction-diffusion length lD ~ 10 nm, this range yields q ≫ 1. In this limit, coth(q)−1/q → 1. As a result, γ shows minimal variation, and the interfacial contribution remains nearly constant at ~0.7–0.9%. This insensitivity arises because SO2 hydrolysis is confined to the first ~10 nm beneath the air–water interface. In this region, the hydrogen-bond network is largely restored and the aqueous phase exhibits a bulk-like density.

Discussion

We report extensive molecular dynamics simulations that were conducted to quantify the thermodynamics and kinetics of SO2 adsorption, solvation and hydrolysis in microdroplets. By explicitly incorporating these processes into a kinetic model, our results reproduce experimentally observed reactive uptake coefficients. Importantly, our simulations reveal that hydrolysis occurs predominantly in the bulk phase, where a robust hydrogen-bond network significantly enhances SO2 reactivity. In contrast, interfacial processes contribute only ~1% to the overall reactivity.

In the aqueous phase, SO2 is hydrolyzed to HSO3⁻ and SO32⁻, which subsequently undergo oxidation by H2O2, O3, or NO2. Our results indicate that hydrolysis is predominant in the bulk phase. This suggests that subsequent oxidation may occur primarily in the bulk, where reactants are concentrated and spatially separated from the interface. Nevertheless, if certain oxidants are enriched or more reactive at the interface, interfacial oxidation could still play a decisive role. Further research on interfacial SO2 oxidation is therefore needed. Building on the framework developed here, future studies of aerosol systems that contain salts and oxidants could provide important insights into multiphase atmospheric chemistry.

Methods

Model of systems

Classical MD simulations were used to study the physical behavior of SO2. System 1 comprised 800 water molecules confined in a simulation box of 28.9 × 28.9 × 100 Å3 (x × y × z), with a single SO2 molecule positioned at the air–water interface. A vacuum spacing of approximately 70 Å was set along the Z-axis (Fig. S2a) to minimize interactions between periodic images. We further conducted NNP-based MD simulations to study the chemical behavior of SO2 in both bulk and interfacial environments. System 2 (bulk) consisted of one SO2 molecule solvated by 127 water molecules in a cubic box of 15.662 × 15.662 × 15.662 Å3 (Fig. S2b). System 3 (surface) was a slab model of 15.662 × 15.662 × 50 Å3, containing 128 water molecules and one SO2 molecule. In the interfacial simulations, the Z-coordinate of SO2 was constrained to within ±1.5 Å of the Gibbs dividing surface (~3 Å in total), thereby sampling the interfacial region. A vacuum gap of approximately 35 Å was introduced along the Z-axis to eliminate spurious periodic interactions (Fig. S2c). Periodic boundary conditions (PBCs) were applied in all three directions in all systems.

Classical molecular dynamics simulations

We performed classical MD simulations combined with the umbrella sampling (US) method to calculate the free energy profile of SO2 transfer from the gas phase into bulk water. Simulations were carried out in the canonical ensemble (NVT) through the velocity-rescaling algorithm by Bussi, Donadio, and Parrinello58 with a time step of 2 fs. Temperature was set to 300 K, with a coupling time constant of 0.1 ps. The SO2 was modeled using the generalized amber force field GAFF59, while water was described by the SPC/E model60. Nonbonded interactions were described by Lennard‒Jones (LJ) and Coulomb potentials. Electrostatic interactions were computed using the particle-mesh Ewald summation method, with a real-space cutoff of 13 Å. The free energy profile was obtained from a series of umbrella sampling simulations. The reaction coordinate was defined as the distance between the center of mass (COM) of the water slab and the SO2 molecule. The bias potential was harmonic, UB=kz(z − z0)2, with kz = 2 kcal mol−1 Å−2. Sampling was performed with 60 windows spanning 0.0–30.0 Å along the z-axis, and an additional 40 windows were placed between 20.0–30.0 Å to achieve convergence. Each simulation window was run for 5 ns, including a 500 ps equilibration phase. Free energies were estimated using the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM)30. Classical MD simulations were performed using the GROMACS 2024.2 package61.

AIMD simulations

AIMD simulations were combined with OPES enhanced sampling (see section OPES enhanced sampling) to build the initial training set for the NNPs. These simulations were carried out on bulk system 2 and surface system 3 with 15.662 × 15.662 × 30 Å3. Input files were generated with Multiwfn program62,63. These simulations were performed in the canonical ensemble (NVT) with a time step of 1 fs. The temperature was controlled using a stochastic velocity-rescaling58 thermostat with a coupling constant of 0.2 ps. Energies and forces were computed with the PBE exchange-correlation functional64. A molopt-DZVP-SR basis set and a plane-wave cutoff of 300 Ry were employed. Core electrons were described by Goedecker-Teter-Hutter (GTH) pseudopotentials65,66 optimized for PBE. AIMD simulations were performed using CP2K 9.167.

Calculation of energies and forces

The DFT energies and forces needed for the NN training were calculated using the B3LYP25,26 hybrid functional. The molopt-DZVP basis set was employed together with the ADMM-DZP auxiliary basis, and a plane-wave cutoff of 1400 Ry was applied. The core electrons were described by GTH pseudopotentials65,66.

To determine the best-performing functional, we computed the energy barriers for the gas phase hydrolysis of SO2·(H2O)n clusters (n = 1–2) at various levels of theory. The results are shown in Fig. S1. The energy barrier obtained at the B3LYP level agreed well with the reference CCSD(T)/def2-tzvp//B3LYP/6-31 G(d,p). In contrast, other functionals showed significant deviations, with PBE and BLYP underestimating the energy barrier. The B3LYP-D3 result was very close to the B3LYP, indicating that the D3 correction had a negligible effect on the reaction barrier. This observation is consistent with previous studies, which reported that D3 corrections have little influence on the hydration behavior of SO216,17. Given this minor effect, the additional computational cost of D3 corrections was unnecessary in this context. ωB97 yielded a reasonable energy barrier but generally incurred higher computational costs. B3LYP provided an optimal balance between computational efficiency and accuracy, indicating that it was a suitable choice for investigating SO2 reactions in both gas and aqueous phases.

NN training

The neural network (NN) potentials were developed using the Deep Potential-Smooth Edition scheme24, as implemented in the DeePMD-kit 2.2.8 package68. This approach employed two neural networks: an embedding network and a fitting network. The embedding network consisted of three hidden layers with 40, 80, and 160 nodes, and the embedding matrix size was set to 16. The fitting network comprised four hidden layers with 240 nodes each. A cutoff radius of 8.0 Å was used, with atomic descriptors smoothly decaying between 0.5 Å and 8.0 Å. The learning rate was decayed from 1.0 × 10−3 to 3.51 × 10−8. The training process used a batch size of 8. The following loss function was minimized during training:

where ɑE, ɑf are the energy and force prefactors, respectively. ∆ denotes the differences between the DeePMD predictions and the training data for energy and forces. N is the number of atoms, E is the energy per atom, and Fi is the force on atom i. The energy and force prefactors in the loss function were varied from 0.02 to 1 and from 1000 to 1, respectively. The model was initially trained for 0.8 × 106 steps, which was extended to 2.0× 106 steps to produce the final neural network.

To assess the influence of the NNP cutoff, we constructed a variant neural network potential. This model augments the original short-range descriptor (se_e2_a) with an additional long-range descriptor (se_e2_r). For the long-range descriptor, a cutoff radius of 12 Å was applied, with atomic descriptors smoothly decaying from 0.5 Å to 12 Å. The embedding network for se_e2_r consisted of three hidden layers with 12, 24, and 48 nodes. The short-range descriptor (se_e2_a) retained the same configuration as in the original NNP.

Training data collecting

The collection of reference configurations for the training set is a critical step in training NNPs, as it directly impacts the potential accuracy. To ensure reliability, an active learning approach21, accelerated by the enhanced sampling method OPES (see section OPES enhanced sampling), was employed. We initially selected approximately 5000 configurations from AIMD simulations of bulk and surface models at 300 and 350 K, with durations of 10–100 ps. This dataset provided the foundation for training an ensemble of NNPs, serving as the starting point for an iterative process:

-

(i)

An ensemble of four NNPs, each initialized with a different random seed, was trained on the same dataset used in the preceding round.

-

(ii)

A set of NNP-based OPES simulations was carried out to sample new relevant configurations along the reaction pathway. For each configuration, model uncertainty was assessed by σ, defined as the maximal standard deviation of atomic forces predicted by the four NNPs:

$$\sigma={\max }_{i}\sqrt{\frac{1}{4}{\sum }_{\alpha=1}^{4}\Vert {F}_{i}^{\alpha }-{\overline{F}}_{i}\Vert }$$(9)where \({F}_{i}^{\alpha }\) is the force on the atom i predicted by the NN potential ɑ, and \( \bar{F\scriptsize i}\) is the average force on the atom i over the four NN potentials. Configurations with 0.2 < σ < 0.5 were prioritized, as they contributed most effectively to diversifying the training dataset. Configurations with σ > \(0.5\) were excluded, as they typically represented non-physical states where atoms were too close or involved improbable chemistry. After each iteration, the dataset was updated, and a new NN was retrained. The error σ was used as the updated uncertainty metric for the next round.

-

(iii)

The energy and forces of selected configurations were labeled with DFT, then incorporated into the training set for NN retraining.

The training set was iteratively updated until the fraction of configurations within the interval 0.2 < σ < 0.5 dropped below 1% and remained nearly unchanged over subsequent iterations. The final dataset contained approximately 60,000 configurations.

NNP-based MD simulations

The neural network potential (NNP)-based MD simulations24,69 were performed using DeePMD-kit interfaced with LAMMPS70 and PLUMED v.2.971. All simulations employed the stochastic velocity rescaling58 thermostat with a coupling constant of 0.05 ps. The temperature was maintained at 300 K with a time step of 0.5 fs.

OPES enhanced sampling

We employed on-the-fly probability enhanced sampling (OPES)22,23 to calculate the free energy of SO2 hydrolysis by optimizing fluctuations in carefully chosen collective variables (CVs), \(s\,=\,s(R)\), where R denotes the atomic coordinates. OPES estimated the equilibrium probability distribution P(s) dynamically and constructed a bias potential Vn(s) that guided s towards a well-tempered target distribution \({P}_{{tg}}\left(s\right){\propto [P(s)]}^{1/\gamma }\). Here, γ > 1 is the bias factor and β = 1/kBT. The bias potential at iteration n is written as:

where Pn(s) is the probability distribution at the n-th iteration, Zn is a normalization factor, and \(\varepsilon \,=\,{{{\rm{e}}}}^{\frac{-{{\rm{\beta }}}\Delta E}{1-1/\gamma }}\) is a regularization parameter that limits the maximum deposited bias. The highest value of ∆E used was 100 kJ mol−1, which increased the robustness of the NN potential.

We selected CVs critical to hydrolysis, namely \({n}_{{{\rm{OH}}}}^{\max }\), the maximum O–H coordination, and a continuous coordination number S–O, nSO. Their definitions are:

with rOH = 1.3 Å, rSO = 2.0 Å. Setting β to 0.01 ensures a smooth evaluation of the soft maxima during calculations.

However, \({n}_{{{\rm{OH}}}}^{\max }\) was highly sensitive to fluctuations in the hydrogen bond network, especially in the presence of numerous H2O molecules, which complicated the distinction between hydrolysis products. To address this issue, we introduced revised Voronoi collective variables (CVs)72,73 to characterize the states of oxygen atoms. When an oxygen atom is coordinated with two hydrogen atoms, the state is set to zero to eliminate the influence of the solution environment effectively. Conversely, if an oxygen atom is coordinated with zero or one hydrogen atom, as in the case of HSO3⁻, its state is assigned as 4 or 1, respectively. The detailed calculations are described below.

To count the number of H atoms ni centered on O atom i, we used the Eq. 14,

Here, the first sum runs over all H atoms with index j, and m is the index of Voronoi centers. The parameter λ controls the smoothness of the function, here, we used λ = 5. The number δi of the Voronoi center i was obtained by subtracting the reference number \({n}_{i}^{0}=2\) corresponding to the H2O state from ni.

Then we defined a CV sa to characterize molecular states (SO2, HSO3⁻, SO32⁻, and H2SO3), by summing contributions from all the O atoms in system.

where \({s}_{{\mbox{a}}}\approx 8\) for SO2, \({s}_{{\mbox{a}}}\approx 12\) for SO32⁻, \({s}_{{\mbox{a}}}\approx 9\) for HSO3⁻, and\({\,s}_{{\mbox{a}}}\approx 6\) for H2SO3.

Kinetic rates estimation

We employed OPES flooding, a modification of standard OPES methods, to estimate the kinetic rates74. This approach enhanced sampling within the initial state basin by filling it to a predefined level, thereby reducing the effective activation barrier for transitions. An excluded region χexc was introduced to ensure that no bias was applied to the transition state (TS). Specifically, based on the calculated free energy surface (FES), the barrier height ∆E and the location of the excluded region χexc were estimated. By combining these two parameters, the TS was left unbiased while the initial free energy basin was sufficiently filled to expedite transitions to the final state. The kinetics of the process was recovered from the flooding simulations, relying on the essential premise that the TS remains unaltered. The physical transition times, \({t}^*\), are given by:

where tMD is the MD simulation time, and V(s) is the bias applied in the flooding simulations. The ensemble average was computed from the flooding trajectory, including both the system potential energy U and the bias potential V. 〈eβ(V(s)〉U+V is the acceleration factor, which is a measure of computational efficiency of the flooding-based approach in estimating the rate constant. Each transition case was evaluated through at least 50 independent simulations. The characteristic time was then extracted by fitting the transition times to a Poisson distribution. The results were validated using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test.

Validation of the neural network model

We validated the accuracy of our model by comparing energy and forces predicted by our NNP with those obtained from DFT on both the training and test datasets. The root mean square errors (RMSE) of energies in the training and test set were 0.9 and 0.8 meV in energy/atom, respectively. The RMSEs of forces in the training and test set were 53 and 52 meV Å−1 in force/atom. The test set consisted of roughly 500 configurations collected along the reactive pathway, including abundant transition configurations sampled in the NNP-based OPES simulation. We included in the test set configurations corresponding to the intermediates and transition states of all the steps discussed in the main text. The comparison of DFT and the corresponding NN predicted atomic forces over the training and test sets is shown in Fig. S3. In addition, reaction energetics between selected transition states (TSs) and a representative reactant (R) predicted by the NNP were benchmarked against DFT results. Ten TS snapshots and one R snapshot were extracted from five independent 2 ns enhanced-sampling NNP-MD trajectories, with bulk water molecules beyond the reactive region frozen to suppress solvent fluctuations. The results show that the NN potential reliably reproduces solution-phase reaction barriers, with an RMSE value of 0.6 kcal mol−1 (see the SI for details).

Furthermore, the radial distribution functions (RDFs) from our NNP were compared with those from DFT-based AIMD. Because B3LYP-level AIMD simulations for the full 128-water system is computationally prohibitive, we instead performed AIMD simulations on a smaller system of 32 water molecules. This allowed a direct comparison with the NNP results. AIMD simulations were carried out at the B3LYP level of theory with DZVP-MOLOPT-GTH basis and GTH pseudopotentials. This level of theory is identical to that used for generating the NNP training labels. The Auxiliary Density Matrix Method (ADMM) was applied with the UZH ADMM-DZP auxiliary basis. A plane-wave cutoff of 700 Ry was applied in a cubic cell of 9.866 Å. Simulations were performed in the NVT ensemble at 300 K with a CSVR thermostat. The time step was 0.5 fs. Four independent 5 ps trajectories were collected after 0.5 ps equilibration. NNP-MD simulations were conducted under identical conditions, yielding five independent 100 ps trajectories after 10 ps equilibration. RDFs were calculated for water-water atom pairs and for interactions between SO2 atoms (S and O) and surrounding water molecules. The results show excellent agreement in peak positions between NNP and DFT confirming that the NNP reproduces the key local structural features of the DFT (Figs S9–S14).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All the inputs to reproduce the results and the data generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo database (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17193403). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

No custom code was developed for this study. Calculations were performed using publicly available software packages, and data analysis used standard Python libraries.

References

Huang, R.-J. et al. High secondary aerosol contribution to particulate pollution during haze events in China. Nature 514, 218–222 (2014).

Fuzzi, S. et al. Particulate matter, air quality and climate: lessons learned and future needs. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 15, 8217–8299 (2015).

Bongaarts, J. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Population and Development Review 50, 577–580 (2024).

Seinfeld, J. H. & Pandis, S. N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change. (Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2016).

Liu, T., Clegg, S. L. & Abbatt, J. P. D. Fast oxidation of sulfur dioxide by hydrogen peroxide in deliquesced aerosol particles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 1354–1359 (2020).

Wang, W. et al. Sulfate formation is dominated by manganese-catalyzed oxidation of SO2 on aerosol surfaces during haze events. Nat Commun 12, 1993 (2021).

Liu, T. & Abbatt, J. P. D. Oxidation of sulfur dioxide by nitrogen dioxide accelerated at the interface of deliquesced aerosol particles. Nat. Chem. 13, 1173–1177 (2021).

Jayne, J. T., Davidovits, P., Worsnop, D. R., Zahniser, M. S. & Kolb, C. E. Uptake of sulfur dioxide(G) by aqueous surfaces as a function of pH: the effect of chemical reaction at the interface. J. Phys. Chem. 94, 6041–6048 (1990).

Ponche, J. L., George, C. H. & Mirabel, P. H. Mass transfer at the air/water interface: Mass accommodation coefficients of SO2, HNO3, NO2 and NH3. J Atmos Chem. 16, 1–21 (1993).

Worsnop, D. R. et al. The temperature dependence of mass accommodation of sulfur dioxide and hydrogen peroxide on aqueous surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. 93, 1159–1172 (1989).

Boniface, J. et al. Uptake of Gas-Phase SO2, H2S, and CO2 by Aqueous Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. A 104, 7502–7510 (2000).

Davidovits, P., Kolb, C. E., Williams, L. R., Jayne, J. T. & Worsnop, D. R. Mass Accommodation and Chemical Reactions at Gas−Liquid Interfaces. Chem. Rev. 106, 1323–1354 (2006).

Baer, M., Mundy, C. J., Chang, T.-M., Tao, F.-M. & Dang, L. X. Interpreting Vibrational Sum-frequency Spectra Of Sulfur Dioxide At The Air/water Interface: A Comprehensive Molecular Dynamics Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 7245–7249 (2010).

Li, W., Pak, C. Y. & Tse, Y.-L. S. Free energy study of H2O, N2O5, SO2, and O3 gas sorption by water droplets/slabs. The Journal of Chemical Physics 148, 164706 (2018).

Shamay, E. S., Johnson, K. E. & Richmond, G. L. Dancing on water: the choreography of sulfur dioxide adsorption to aqueous surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 25304–25314 (2011).

Zhong, J. et al. Interaction of SO2 with the surface of a water nanodroplet. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 17168–17174 (2017).

Shamay, E. S., Valley, N. A., Moore, F. G. & Richmond, G. L. Staying hydrated: the molecular journey of gaseous sulfur dioxide to a water surface. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 6893–6902 (2013).

Liu, J. et al. Mechanism of the gaseous hydrolysis reaction of SO2: effects of NH3 versus H2O. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 102–111 (2015).

Behler, J. Generalized Neural-Network Representation of High-Dimensional Potential-Energy Surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, (2007).

Yang, M., Raucci, U. & Parrinello, M. Reactant-induced dynamics of lithium imide surfaces during the ammonia decomposition process. Nat Catal 6, 829–836 (2023).

Yang, M., Bonati, L., Polino, D. & Parrinello, M. Using metadynamics to build neural network potentials for reactive events: the case of urea decomposition in water. Catalysis Today 387, 143–149 (2022).

Invernizzi, M., Piaggi, P. M. & Parrinello, M. Unified Approach to Enhanced Sampling. Phys. Rev. X 10, 041034 (2020).

Invernizzi, M. & Parrinello, M. Rethinking Metadynamics: From Bias Potentials to Probability Distributions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 2731–2736 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. End-to-end symmetry preserving inter-atomic potential energy model for finite and extended systems. in Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 4441–4451 (Curran Associates Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA, 2018).

Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. The Journal of Chemical Physics 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Lee, C. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B 37, 785–789 (1988).

Hohenberg, P. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864–B871 (1964).

Kohn, W. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133–A1138 (1965).

Torrie, G. M. & Valleau, J. P. Nonphysical sampling distributions in Monte Carlo free-energy estimation: Umbrella sampling. Journal of Computational Physics 23, 187–199 (1977).

Kumar, S., Rosenberg, J. M., Bouzida, D., Swendsen, R. H. & Kollman, P. A. THE weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. Journal of Computational Chemistry 13, 1011–1021 (1992).

Sander, R. Compilation of Henry’s law constants (version 4.0) for water as solvent. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 4399–4981 (2015).

Wiberg, N., Holleman, A. F. & Wiberg, E. Inorganic Chemistry. (Academic Press Inc, San Diego: Berlin; New York, 2001).

Morita, A., Sugiyama, M., Kameda, H., Koda, S. & Hanson, D. R. Mass accommodation coefficient of water: molecular dynamics simulation and revised analysis of droplet train/flow reactor experiment. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 9111–9120 (2004).

Wilson, M. A. & Pohorille, A. Adsorption and solvation of ethanol at the water liquid−vapor interface: a molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 3130–3135 (1997).

Tarbuck, T. L. & Richmond, G. L. Adsorption and reaction of CO2 and SO2 at a water surface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 3256–3267 (2006).

Misiewicz, J. P. et al. Sulfurous and sulfonic acids: Predicting the infrared spectrum and setting the surface straight. The Journal of Chemical Physics 152, 024302 (2020).

Millero, F. J., Hershey, J. P., Johnson, G. & Zhang, J.-Z. The solubility of SO2 and the dissociation of H2SO3 in NaCl solutions. J Atmos Chem 8, 377–389 (1989).

Goldberg, R. N. & Parker, V. B. Thermodynamics of solution of so2(g) in water and of aqueous sulfur dioxide solutions. J Res Natl Bur Stand (1977) 90, 341–358 (1985).

Eigen, M., Kustin, K. & Maass, G. Die Geschwindigkeit der Hydratation von SO2 in wäßriger Lösung. Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie 30, 130–136 (1961).

Galib, M. & Limmer, D. T. Reactive uptake of N 2 O 5 by atmospheric aerosol is dominated by interfacial processes. Science 371, 921–925 (2021).

Fang, Y.-G. et al. Mechanistic insight into the competition between interfacial and bulk reactions in microdroplets through N2O5 ammonolysis and hydrolysis. Nat Commun 15, 2347 (2024).

Cruzeiro, V. W. D., Galib, M., Limmer, D. T. & Götz, A. W. Uptake of N2O5 by aqueous aerosol unveiled using chemically accurate many-body potentials. Nat Commun 13, 1266 (2022).

Gao, A. & Remsing, R. C. Self-consistent determination of long-range electrostatics in neural network potentials. Nat Commun 13, 1572 (2022).

Niblett, S. P., Galib, M. & Limmer, D. T. Learning intermolecular forces at liquid-vapor interfaces. J Chem Phys 155, 164101 (2021).

Grisafi, A., Nigam, J. & Ceriotti, M. Multi-scale approach for the prediction of atomic scale properties. Chem. Sci. 12, 2078–2090 (2021).

Pihko, P. M. Carbonylaktivierung durch doppelte Wasserstoffbrückenbildung: ein neues Werkzeug für die asymmetrische Katalyse. Angewandte Chemie 116, 2110–2113 (2004).

Doyle, A. G. & Jacobsen, E. N. Small-molecule H-bond donors in asymmetric catalysis. Chem. Rev. 107, 5713–5743 (2007).

Ruiz-Lopez, M. F., Francisco, J. S., Martins-Costa, M. T. C. & Anglada, J. M. Molecular reactions at aqueous interfaces. Nat Rev Chem 4, 459–475 (2020).

Jung, Y. & Marcus, R. A. On the theory of organic catalysis “on water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 5492–5502 (2007).

Jung, Y. & Marcus, R. A. Protruding interfacial OH groups and ‘on-water’ heterogeneous catalysis. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 22, 284117 (2010).

Thomas, L. L., Tirado-Rives, J. & Jorgensen, W. L. Quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical modeling finds diels−alder reactions are accelerated less on the surface of water than in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 3097–3104 (2010).

Karhan, K., Khaliullin, R. Z. & Kühne, T. D. On the role of interfacial hydrogen bonds in “on-water” catalysis. The Journal of Chemical Physics 141, 22D528 (2014).

Kumar, N., Bryantsev, V. S. & Roy, S. The role of nonequilibrium solvent effects in enhancing direct co2 capture at the air–aqueous amino acid interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 1411–1415 (2025).

Ma, X., Bryantsev, V. S. & Roy, S. An ab initio free energy study of the reaction mechanism and rate-limiting steps of CO2 capture by aqueous glycine. Cell Reports Physical Science 4, 101642 (2023).

Leaist, D. G. Diffusion coefficient of aqueous sulfur dioxide at 25.degree.C. J. Chem. Eng. Data 29, 281–282 (1984).

Hanson, D. R. Surface-specific reactions on liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 4998–5001 (1997).

Hanson, D. R. & Ravishankara, A. R. Reactive uptake of ClONO2 onto Sulfuric Acid Due to Reaction with HCl and H2O. J. Phys. Chem. 98, 5728–5735 (1994).

Bussi, G., Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J Chem Phys 126, 014101 (2007).

Wang, J., Wolf, R. M., Caldwell, J. W., Kollman, P. A. & Case, D. A. Development and testing of a general amber force field. Journal of Computational Chemistry 25, 1157–1174 (2004).

Berendsen, H. J. C., Grigera, J. R. & Straatsma, T. P. The missing term in effective pair potentials. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 6269–6271 (1987).

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1–2, 19–25 (2015).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. Journal of Computational Chemistry 33, 580–592 (2012).

Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists, Multiwfn. J Chem Phys 161, 082503 (2024).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Goedecker, S., Teter, M. & Hutter, J. Separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials. Phys. Rev. B 54, 1703–1710 (1996).

Hartwigsen, C., Goedecker, S. & Hutter, J. Relativistic separable dual-space Gaussian pseudopotentials from H to Rn. Phys. Rev. B 58, 3641–3662 (1998).

Hutter, J., Iannuzzi, M., Schiffmann, F. & VandeVondele, J. cp2k: atomistic simulations of condensed matter systems. WIREs Computational Molecular Science 4, 15–25 (2014).

Wang, H. et al. DeePMD-kit: A deep learning package for many-body potential energy representation and molecular dynamics. Computer Physics Communications 228, 178–184 (2018).

Singraber, A., Behler, J. & Dellago, C. Library-Based LAMMPS Implementation of High-Dimensional Neural Network Potentials. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 1827–1840 (2019).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Computer Physics Communications 271, 108171 (2022).

Tribello, G. A., Bonomi, M., Branduardi, D., Camilloni, C. & Bussi, G. PLUMED 2: New feathers for an old bird. Computer Physics Communications 185, 604–613 (2014).

Zhang, P., Gardini, A. T., Xu, X. & Parrinello, M. Intramolecular and water mediated tautomerism of solvated glycine. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 64, 3599–3604 (2024).

Grifoni, E., Piccini, G. & Parrinello, M. Microscopic description of acid–base equilibrium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, 4054–4057 (2019).

Ray, D., Ansari, N., Rizzi, V., Invernizzi, M. & Parrinello, M. Rare Event Kinetics from Adaptive Bias Enhanced Sampling. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 18, 6500–6509 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22403042, M.Y.), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BK20241192, M.Y.) and the National Key Scientific and Technological Infrastructure project “Earth System Science Numerical Simulator Facility” (EarthLab). Part of the computations were performed on the High-Performance Computing Center (HPCC) of Nanjing University. We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Umberto Raucci and Dr. Pengchao Zhang for discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S., M.Y. and H.W. conceived and led the study. M.Y. and H.W. designed the numerical experiments. M.D. performed molecular dynamics simulations. M.D., M.Y., H.W., Y.S. and T.Z. interpreted the results and wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Theo Kurtén, Santanu Roy, and Margaret Berrens for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, M., Yang, M., Wang, H. et al. Bulk Phase Dominates Sulfur Dioxide Hydrolysis over Interfacial Processes. Nat Commun 17, 558 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67250-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67250-1