Abstract

Metabolic syndrome (MetS), a cluster of conditions including abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, and abnormal blood sugar and lipid levels, is a growing global health concern, yet its global burden remains poorly characterized. Here we show trends in MetS prevalence from 2000 to 2023, based on a systematic review and Bayesian modelling of 3236 data points with 45,549,151 adults. Between 2000 and 2023, prevalence rose from 14.7% (13.1–16.7) to 31.0% (28.5-33.9) among women, and from 9.0% (6.9–12.1) to 25.7% (21.5–31.1) among men. In 2023, an estimated 1.54 billion adults (1.35–1.76) had MetS globally: 846 million (776–924) women and 692 million (579–837) men. Prevalence increased with age, urbanicity, and income level, ranging from 7.5% to 45.0% among women and 6.5% to 59.6% among men across regions. Among both women and men, prevalence increased in 196 countries and territories. These findings call for targeted interventions to address the rising global burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of metabolic abnormalities including obesity, insulin resistance, elevated blood pressure, low high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), and elevated triglycerides1. These components are major contributors to global disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and mortality. Elevated fasting glucose ( ≥ 5.4 mmol/L) causes 6.5% of DALYs and 2.4 million deaths; elevated systolic blood pressure ( ≥ 110–115 mmHg) accounts for 10.8 million deaths and 218 million DALYs2. High low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) causes 4.4 million deaths annually3, while overweight and obesity (body mass index, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m²) contribute to 5 million deaths and 160 million DALYs, especially rising in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)4.

Metabolic syndrome results from genetic and environmental factors. Although obesity is no longer always required for diagnosis, it remains a key driver and often precedes other abnormalities5. The syndrome stems mainly from an energy imbalance caused by unhealthy diets and sedentary lifestyles within a genetic context6. Most definitions of metabolic syndrome require at least three of five components, with some variation in thresholds1. Despite debates on its definition, metabolic syndrome remains a valuable public health tool for identifying individuals at high risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney disease, some cancers, and early death, even before clinical disease manifests6.

While numerous global initiatives have quantified the prevalence of individual cardiometabolic risk factors in the general population, few have evaluated their co-occurrence within the framework of metabolic syndrome7,8. This clustering is clinically relevant, as individuals with metabolic syndrome are at substantially higher risk of developing chronic diseases than those with isolated risk factors. Estimating the prevalence of metabolic syndrome at global, regional, and country levels among adults in the general population provides critical insights into the cumulative burden of non-communicable diseases and can inform integrated public health interventions. Here, we show estimates of the prevalence and prevalent cases of metabolic syndrome in women and men across 198 countries and territories from 2000 to 2023. We find that global prevalence has more than doubled in both sexes, reaching 31.0% among women and 25.7% among men in 2023, with substantial variation by age, socioeconomic context, regions, and countries, and socioeconomic context. An estimated 1.54 billion adults are affected worldwide. These findings underscore the urgent need for targeted public health strategies to address the growing burden of metabolic syndrome.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

In total, we included 597 reports with 3236 prevalence data (Supplementary Fig. 1). The total number of participants was 45,549,151. In the original reports, data were collected between 1990 and 2019 and published between 2001 and 2022. According to the setting, 1052 prevalence data were from urban areas, 847 among rural areas, and 1337 among both. According to sex, 1910 prevalence data were from women and 1310 from females. According to representativeness, 686 prevalence data were nationally representative from 44 countries. All super-regions had data except Oceania (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Table 2, and Supplementary Table 3).

Global level

Globally for both merged women and men, the metabolic syndrome prevalence increased from 11.9% (95% credible intervals, CrI: 10.0–14.4) in 2000 to 28.4% (25.0–32.5) in 2023 (absolute increase: +16.5%). Among women, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome increased from 14.7% (13.1–16.7) in 2000 to 31.0% (28.5–33.9) in 2023 (absolute increase: +16.3%). Among men, prevalence rose from 9.0% (6.9–12.1) to 25.7% (21.5–31.1) over the same period (absolute increase of +16.7%) (Table 1, Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 4).

Time trends of metabolic syndrome prevalence (%) for women (in red) and men (in blue) at global level and in regions. Each panel shows the prevalence trajectory from 2000 to 2023. Central lines are bounded by a semi-transparent band representing the 95% credible intervals. Panels share a common y scale to facilitate regional comparisons.

In 2023, an estimated 1.54 billion adults (95% CrI 1.35–1.76) globally were living with metabolic syndrome. There has been a substantial increase in the total number of metabolic syndrome cases for both men and women between 2000 and 2023. The primary driver for this increase in both sexes was the prevalence effect (Fig. 2). East Asia and South Asia emerged as the regions contributing most significantly to this burden, for both men and women in 2023 (Supplementary Fig. 2). The prevalent cases of metabolic syndrome increased from 277 million (246–313) in 2000 to 846 (776–924) million in 2023 among women: 45.8% of this increase was explained by prevalence change, 29.2% by population growth and aging, and 25.0% by the interaction between age structure and prevalence changes. The prevalent cases of metabolic syndrome increased from 166 million (126–222) in 2000 to 692 million (579–837) in 2023 among men: 52.9% of this increase was explained by prevalence change, 19.3% by population growth and aging, and 27.8% by the interaction.

Stacked decomposition of net change in prevalent metabolic syndrome cases (absolute counts) between 2000 and 2023 for women (left) and men (right). Bars show the reference number of cases in 2000 and the total cases in 2023; intermediate segments decompose the net change into the population effect (change due to population growth/age structure), prevalence effect (change due to shifts in age-specific prevalence), and interaction effect (joint effect of population and prevalence changes). Y axis: number of prevalent cases; X axis: year (2000 baseline and subsequent years shown).

Prevalence in 2023 increased with national income level (Supplementary Fig. 3), from 6.2% (CrI: 4.0–9.1) in low income to 38.0% (34.6–41.5) in high-income countries among women, and from 3.7% (2.0–7.9) to 45.9% (38.6–52.7) among men. The prevalence was higher among women in low- and middle-income countries (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 4). A similar gradient was observed with urbanicity (Supplementary Fig. 4): among women, prevalence rose from 12.6% (10.3–16.1) in low-urbanicity settings to 37.4% (34.3–40.7) in highly urbanized areas; among men, it increased from 9.0% (3.7–19.5) to 39.0% (34.3–40.7). The prevalence was higher among women in low- and middle-urbanized countries (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 4).

Prevalence of metabolic syndrome (%) in men (in blue) and women (in red) stratified by national income group (top) and national urbanicity group (bottom). Bars represent prevalence estimates for each sex and category; percentage values shown on the figure indicate the point estimates. Error bars denote the 95% credible intervals. Estimates were derived from modelling analysis.

In 2023, Although rates were similar between men and women in early adulthood (ages 20–40), a substantial sex disparity emerged from midlife onwards. Women consistently exhibited higher prevalence, peaking at nearly 55% in their early-to-mid 70 s, compared to a peak of approximately 45% among men in the same age group. In the oldest age categories, prevalence plateaued or slightly declined (Supplementary Fig. 5). In terms of prevalent cases, the highest burden in 2023 was among women aged 50–54 years (82.8 million; 76.5–89.8) and men aged 35–39 years (84.3 million; 70.1–103.1) (Fig. 4).

When stratified jointly by income level, urbanicity level, and sex, considering the analysis of metabolic syndrome prevalence dependent to age, clear and consistent patterns emerged. The comprehensive analysis of metabolic syndrome prevalence in 2023 reveals a consistent age-dependent increase across all income and urbanicity strata, with women disproportionately affected at older ages. While this trend is universal, higher income and increased urbanicity are associated with a steeper rise in prevalence, culminating in peak rates among high-income, highly urbanized populations, particularly in women (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Regional prevalence

Across almost all regions, there was a clear upward trend in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome for both men and women between 2000 and 2023. While both sexes showed an increase, the magnitude and rate of increase varied by region. In most of the regions, the prevalence in women was higher than in men throughout the period, or the gap between women and men widens over time, with women experiencing a steeper increase (Fig. 1).

The highest absolute increase of prevalence was in East Asia (+28.1%) among women and in Central Europe among men (+42.7%); and the lowest increase among in Central Africa among women (+3.0%) and high-income Asia Pacific among men (+2.5%) (Table 1; Supplementary Table 4). In 2023, the prevalence of metabolic syndrome among women varied markedly across regions, ranging from 7.5% (95% CrI: 5.3–10.4) in Central Africa to 45.0% (43.7–6.3) in high-income English-speaking countries. Among men, regional estimates ranged from 6.5% (2.8–12.5) in Central Africa to 59.6% (51.0–67.4) in Central Europe (Table 1; Supplementary Table 4). The magnitude and direction of sex differences in prevalence varied considerably by region. The absolute difference between women and men ranged from −24.5% in Southwestern Europe (where men had higher prevalence) to +18.9% in Southern Latin America (where women had higher prevalence) (Table 1; Supplementary Table 4).

East Asia accounted for the highest absolute number of individuals living with metabolic syndrome in 2023, with 212 million women (95% UI: 210–215) and 157 million men (155–159) affected (Table 1; Supplementary Table 4). The regions with the highest increase of cases of metabolic syndrome were East Asia in both women (ratio of prevalent cases 2023 vs. 2000 = 5.4) and men (ratio of prevalent cases 2023 vs. 2000 = 17.8) (Table 1; Supplementary Table 4). Analysis of estimated case numbers by region for women and men between 2000 and 2023 revealed distinct decomposition patterns (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). From 2000 to 2023, the relative contributions of aging and population growth, prevalence, and interaction effects to the increase in metabolic syndrome cases exhibited distinct patterns across regions and between sexes. For women, the lowest prevalence effect was 3% in Eastern Europe and East Asia, while the highest was 94% in Eastern Europe. The lowest population effect for women, representing aging and population growth, was 3% in Eastern Europe and East Asia, with the highest at 62% in North Western Europe. The interaction effect for women ranged from a low of 3% in Eastern Europe and East Asia to a high of 54% in High-income Asia Pacific. For men, the prevalence effect ranged from a low of 0% in Eastern Europe to a high of 51% in High-income Asia Pacific. The population effect for men, representing aging and population growth, had a lowest contribution of -5% in High-income Asia Pacific and a highest of 99% in Eastern Europe. The interaction effect for men varied from 0% in Eastern Europe to 54% in High-income Asia Pacific (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11).

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome increased steadily with age across all world regions, peaking between 65 and 74 years before declining slightly in the oldest age groups. Central Europe, East Asia, and high-income English-speaking countries showed the highest age-specific prevalences, particularly among women. In contrast, Sub-Saharan African regions consistently exhibited the lowest levels across all age groups. Sex differences emerged after age 45, with women experiencing higher prevalence than men in most regions (Fig. 5).

Heatmap showing the prevalence of metabolic syndrome (%) in 2023 across world regions and age groups, separately for men and women. Cell shading indicates the prevalence within each stratum. The heatmap highlights both the age gradient of metabolic syndrome prevalence and regional heterogeneity. The colour scale ranges from green (lower prevalence) to red (higher prevalence), with darker shading reflecting greater burden.

Country-specific prevalence

Figures 6 and 7 present country-level maps of the estimated prevalence of metabolic syndrome in 2023, and the variation compared to 2000 (Supplementary Fig. 12, Supplementary Fig. 13), respectively in women and men, across 198 countries and territories. The global distribution of metabolic syndrome prevalence in 2023 reveals marked geographic and sex-related disparities (Fig. 8). Among women, the highest prevalence estimates were observed in Bermuda, Puerto Rico, Hong Kong, The Bahamas, and Iraq. For men, the five countries with the highest prevalence were Bermuda, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Estonia, and Seychelles. At the other end of the spectrum, the lowest prevalence among women was found in Burundi, Central African Republic, Madagascar, Malawi, and Chad, while among men, North Korea, Yemen, Burundi, Central African Republic, and Afghanistan had the lowest levels (Supplementary Table 4). Among between 2000 and 2023, among women the prevalence increased in 196 countries and territories, at least doubled in 66, and at least tripled in 21; while among men it increased in 196 countries and territories, at least doubled in 139 and at least tripled in 85 (Fig. 9).

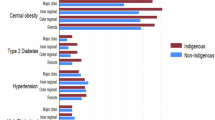

This figure presents estimates of metabolic syndrome prevalence (%) in men and women across countries, with credible intervals shown in brackets. Data are organized by regions (Sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia and Middle East/North Africa, East and Southeast Asia, Oceania, Latin America and the Caribbean, South Asia, High-income Asia Pacific, Central and Eastern Europe, and High-income Western countries). National estimates highlight within-region variation, while regional groupings provide a comparative overview of global patterns in metabolic syndrome.

Scatterplot of country-level prevalence of metabolic syndrome (%) in 2000 (x-axis) and 2023 (y-axis). Each dot represents one country, coloured by its region; facets show women (top) and men (bottom). The black square indicates the global prevalence. Reference lines aid interpretation: the grey diagonal (y = x) marks equal prevalence in 2000 and 2023, the blue line (y = 2x) indicates a doubling, and the red line (y = 3x) indicates a tripling of prevalence. Countries above the grey line experienced increases in prevalence, while those below experienced declines.

In 102 countries, prevalence estimates were higher in women than in men (Supplementary Table 4). The magnitude of sex differences varied widely across countries, with the absolute difference ranging from –36.7% in France (higher in men) to +51.6% in Hong Kong (higher in women). The most pronounced increase in prevalence between 2000 and 2023 was observed in Guyana among women (+33.0%) and in Romania among men (+51.5%) (Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

This study reveals a striking increase in metabolic syndrome prevalence from 11.9% (95% CrI: 10.0–14.4) in 2000 to 28.4% (25.0–32.5) in 2023, affecting approximately 1.54 billion adults worldwide. The findings highlight significant sex disparities, with a higher prevalence among women, affecting roughly one in three women, compared to men, where approximately one in four men are affected in 2023. Prevalence increased with age, national income, and urbanization level, and varied significantly across regions and countries. These findings complement prior global health research by focusing not on individual metabolic risk factors, but on their co-occurrence as defined by metabolic syndrome. This approach reflects real-world clinical complexity, where patients frequently present with multiple interrelated risk factors rather than isolated conditions.

The rising metabolic syndrome prevalence parallels global trends in individual cardiometabolic risk factors. For instance, according to the International Diabetes Federation, there were 589 million people with diabetes aged 20 to 79 years in 2024 globally, compared with 151 million in 20009. In parallel, a Global Burden of Disease study showed that in 2015, 603.7 million adults were living with obesity worldwide, giving a prevalence of 12%4. Between 1980 and 2015, this prevalence of obesity had doubled in more than 70 countries and has continuously increased in most other countries4. Hypertension has also become more common, with the prevalence of elevated systolic pressure (≥140 mmHg) that increased from 17.3% in 1990 to 20.5% in 201510. In addition, this increase could also be partially explained by the change in 2018 in the definition of hypertension, with diastolic blood pressure figures decreasing from 90 mmHg to 80 mmHg11. Prior meta-analyses report high global prevalence of metabolic syndrome components: central obesity (~45%), hypertension (~43%), low HDL cholesterol (~40%), elevated triglycerides (~29%), and high fasting glucose (~25%)8. The clustering of these factors may confer a greater cardiovascular risk than their independent effects1,5. The surge in metabolic syndrome prevalence reflects the concurrent increase in these individual risk factors, highlighting the clinical importance of considering their co-occurrence rather than isolated conditions.

The sharp increase in metabolic syndrome prevalence over two decades is likely driven by multiple, interacting factors. Aging populations contribute significantly, as risk increases with age. Urbanization and lifestyle changes associated with rapid economic development have played a critical role; particularly the adoption of Westernized diets rich in ultra-processed, energy-dense foods, reduced physical activity, increased sedentary behaviour, and heightened psychosocial stress6,12. This is supported by the finding in this study that the prevalence of metabolic syndrome increased independently with the level of urbanicity and country income across all age and sex groups. The rapid urbanization is particularly marked in low- and middle-income countries, mirroring the surge in cardiometabolic risk factors in these countries12. It is estimated that by 2050, 90% of the expected increase in the world’s urban population will take place in the urban areas of Africa and Asia13. Unfortunately, the correlation of the rate of urbanization with economic growth in these regions is low13, meaning that a large proportion of their urban populations have relatively low income and are unable to afford healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables. Furthermore, the urban environment is more sedentary, with occupations that requires less energy expenditure compared to rural ones, and the widespread use of motorized transport12. Environmental factors such as pollution may further exacerbate risk14,15. The findings reinforce the need for tailored cardiometabolic prevention strategies that address both behavioural risk factors and the structural drivers of health in rapidly developing countries.

While higher-income countries may have better healthcare access, their populations are also more exposed to lifestyle-related risk factors that contribute to obesity, insulin resistance, and dyslipidaemias; all central components of metabolic syndrome4,16,17. The fact that this gradient is observed in both sexes, but is even more pronounced among women, may reflect differences in occupational patterns, health behaviours, or sex-based access to prevention and care. Importantly, this socioeconomic pattern suggests that as low- and middle-income countries undergo economic growth, they may face accelerating burdens of metabolic disease, unless proactive, context-appropriate public health interventions are implemented16.

Women have had a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome throughout 2000-2023. This higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome in women is consistent with higher rates of obesity in women compared to men4. In fact, there is not only sex difference in obesity prevalence, but also in body fat distribution18. Several mechanisms have been postulated to explain these sex differences in obesity. Women are potentially genetically predisposed to store excess fat for reproduction and lactation18. Although studies comparing energy expenditure or basal metabolic rate in women and men have yielded conflicting results, data consistently suggest that physical activity energy expenditure is associated with smaller reduction in body weight and fat loss in women than men18. In terms of body fat distribution, men and oestrogen-deficient postmenopausal women tend to accumulate more abdominal and visceral (central) fat and premenopausal women more gluteo-femoral (peripheral) fat18. Visceral fat is associated with increased cardiometabolic risk, whereas gluteo-femoral fat seems to be protective18,19. This explains why despite a lower prevalence of obesity, the deleterious effects of obesity are higher in men, especially in terms of cardiovascular disease burden18.

In this global analysis, we observed distinct sex-based disparities in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome across income and urban strata. Specifically, women exhibited a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome compared to men in low- and middle-income or urbanized countries. This aligns with literature suggesting that socioeconomic disadvantages disproportionately affect women in these settings, contributing to increased risk due to factors such as limited access to resources and specific lifestyle determinants (lower household income, lower education level, and occupational status more pronounced in rural and lower income settings)20,21,22,23.

Country and regional prevalence and trends varied widely, reflecting diverse sociodemographic and environmental contexts. While East Asia and South Asia bore the greatest burden in terms of the number of metabolic syndrome cases, regions such as high-income Western countries and Central and Eastern Europe had higher prevalence, and Sub-Saharan Africa had consistently lower prevalence. Some countries and regions experienced dramatic increases, while others saw more modest changes. These disparities highlight the importance of local epidemiology in tailoring interventions.

Metabolic syndrome significantly increases the risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, cancer, and premature mortality6,24. To the best of our knowledge, no study has quantified the burden of metabolic syndrome at the global level, in terms of mortality and disability. However, there are data for risk factors related to metabolic syndrome. According to the Global Burden of Disease study, high systolic blood pressure (>115 mmHg), high fasting plasma glucose (>5.4 mmol/L) and high BMI (>25 kg/m2) are among the four leading risk factors for disease, accounting together for 37.9% of total deaths and 20.5% of total disability-adjusted life years in 2015, globally25. These data suggest that metabolic syndrome significantly contributes to the global burden of disease. The high and increasing prevalence found in this study represents a major clinical and public health challenge. The clustering of risk factors accelerates disease progression and complicates management, stressing the need for integrated clinical strategies that target multiple metabolic abnormalities simultaneously26.

Public health interventions are needed to curb the progression of metabolic syndrome and related cardiometabolic risk factors. Such interventions should be primarily directed towards promoting and increasing the availability, accessibility, and affordability of healthy foods including fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, while controlling the use of energy-dense foods and the intensive marketing of such foods12. A legislation framework to regulate the dietary content of processed foods should be established and implemented with the collaboration of food industries. Improving opportunities for physical activity is also crucial. In this regard, the United Nations Environment Programme in collaboration with the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy developed a toolkit on ‘How to develop a non-motorised transport policy.’ to help building a walking and cycling environment that offers basic mobility, affordable transport, access to public transport and health benefits27.

Although metabolic syndrome diagnostic is based on a cluster of cardiometabolic risk factors, the contribution of each component is not at the same level. A recent global meta-analysis reported that the global prevalence was 45.1% for ethnic-specific central obesity, 42.6% for the high blood pressure, 40.2% for low HDL-cholesterol, 28.9% for high serum triglycerides, and 24.5% for high fasting plasma glucose7. These data position obesity as the primary target for public health interventions to curb the burden related to metabolic syndrome, closely followed by high blood pressure. However, integrated interventions toward the cluster of the components of metabolic seems to be the best-in-class powerful approach than targeting one component. Pharmacological approaches, such as phentermine topiramate and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, could also be considered as adjuncts to lifestyle interventions for managing metabolic syndrome28, although universal testing and treatment are unlikely to be feasible or cost-effective at the population level, particularly in resource-limited settings. Clinicians should be aware of the high and rising burden of metabolic syndrome, particularly among middle-aged and older adults and women. Early identification and comprehensive management of clustered cardiometabolic risk factors can mitigate progression to type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, cancer, and premature mortality6,24. Multidisciplinary care approaches and patient education are essential to address lifestyle modification challenges.

This study has some limitations. Not all countries and regions had data to build the model. Despite our extensive efforts to identify and access worldwide population-based data, some countries had no or few data sources, especially those in sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, Central Asia, and Central Europe. Estimates for these countries relied mostly or entirely on the statistical model, which shares information across years, countries, and regions through its hierarchy and through predictive covariates. The absence or scarcity of data is reflected in wider uncertainty intervals of our estimates for these countries and regions. It is important to note that for the JIS definition of metabolic syndrome, the criteria for waist circumference is not the same across regions and countries among men to adapt for context-specific definition of central obesity. We were not able to introduce in the statistical model other sources of variability of metabolic syndrome prevalence because of scarcity of reported data in primary studies: lifestyle habits (low physical activity, high energy intake, unhealthy diets, poor quality of sleep, alcohol use, and tobacco use), air pollution, and occupation29. It would have been interesting to examine the proportional importance of each components of the metabolic syndrome not only at global but also at regional and country levels. However, conducting such analyses would have been challenging because of the scarcity, heterogeneity and inconsistency on the reporting of each component of the metabolic syndrome across studies. Future studies should investigate component-specific trends and their relative contributions to metabolic syndrome prevalence, ideally using harmonized definitions and standardized reporting practices. Our study defined elevated blood pressure as ≥130/85 mmHg or antihypertensive treatment, per the harmonized metabolic syndrome criteria. However, recent guidelines now classify hypertension as ≥130/80 mmHg11. This lower threshold, particularly for diastolic BP (≥80 mmHg vs. ≥85 mmHg), could increase the apparent prevalence of metabolic syndrome by expanding the pool of individuals meeting the blood pressure criterion. Such a shift may disproportionately affect populations with borderline elevated blood pressure, potentially altering risk stratification and the clinical interpretation of metabolic syndrome. Standardization of metabolic syndrome criteria across evolving clinical guidelines remains an important consideration for longitudinal and comparative research. It is important to note that the variability in sampling approaches across studies may introduce some bias which could affect the accuracy of the prevalence estimates. In the end, over 3000 prevalence datapoints with more than 40 million individuals were included as the result of a methodological process rigorously conducted considering multiple data sources. Furthermore, robust statistical procedures were applied using Bayesian modelling that explained more than 99% of the variance in metabolic syndrome prevalence. The use of Bayesian hierarchical modelling allowed robust estimation while accounting for data gaps and variability. To minimize bias from subnational data, we restricted inclusion to population-based studies using probabilistic sampling and assessed methodological quality based on three core criteria. Within our Bayesian multilevel framework, we further adjusted for study representativeness and incorporated hierarchical random effects. While alternative strategies such as quality-score weighting have been applied in other global analyses, our stringent inclusion criteria ensured a consistently high methodological standard across studies.

Metabolic syndrome is a growing global health crisis, with more than one in four adults affected worldwide in 2023. The rising prevalence is driven by aging populations, disproportionately impacting women and higher-income urban settings with substantial country and regional heterogeneity. Tailored clinical and public health interventions are needed to mitigate the expanding burden and associated cardiometabolic diseases. Continued global surveillance and research will be vital to inform effective strategies in diverse settings.

Methods

Study design and definitions

This systematic review with modelling analysis was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for systematic reviews30, and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Supplementary Note 1)31. This review was not registered. We estimated metabolic syndrome prevalence among men and women from 2000 to 2023 across 198 countries and territories, grouped into 21 regions and nine super-regions. Regional and super-regional grouping were based primarily on geographical proximity and national income classifications, with one exception: a specific region comprised high-income English-speaking countries, grouped together to reflect their distinct cardiometabolic risk profiles, which differ from those of other countries within their geographical areas. The grouping was done as per Global Burden of Diseases framework (Supplementary Table 5)2,3. Countries were stratified by income level using the 2023 World Bank gross national income per capita classifications and by urbanicity level in 2023, categorized into four quartiles32,33.

Metabolic syndrome was defined as the presence of at least three out of five components: elevated fasting plasma glucose, raised blood pressure, elevated triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), and central obesity. Specifically, elevated glucose was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥5.6 mmol/L or the use of glucose-lowering medications; elevated blood pressure as systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mmHg, or the use of antihypertensive medications in individuals with a history of hypertension; elevated triglycerides as fasting triglycerides ≥1.7 mmol/L or use of lipid-lowering therapy; low HDL-C as fasting HDL-C ≤ 1.29 mmol/L in women and ≤1.03 mmol/L in men, or treatment for low HDL-C; and central obesity as a waist circumference ≥80 cm for women. For men, central obesity was defined as ≥90 cm in Central Asia, East and Southeast Asia, High-income Asia Pacific, South Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean, or ≥94 cm in Central and Eastern Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, high-income Western countries, Oceania, and Sub-Saharan Africa. These criteria correspond to the harmonized definition proposed by the Joint Interim Statement (JIS) of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the American Heart Association, the World Heart Federation, the International Atherosclerosis Society, and the International Association for the Study of Obesity5.

Data sources

Using PRESS guidelines34, we searched PubMed, Excerpta Medica Database, Web of Knowledge (including Web of Science Core collection, Current Contents Connect, KCI-Korean Journal Database, Russian Science Citation Index, Scientific Electronic Library Online Citation index), African Journals Online, Global Index Medicus (including Literatura Latino Americana em Ciências da Saúde, Index Medicus for South-East Asia Region, Western Pacific Region Medicus, Index Medicus for the Eastern Mediterranean Region, Africa Index Medicus) up to September 20, 2022. We searched for records regardless of the language of publication. Key search terms introduced in the search as medical subject heading terms and text words included “metabolic syndrome”, “insulin resistance syndrome”, and “cardiometabolic syndrome” (Supplementary Table 6).

We included population-based observational studies-either cross-sectional surveys or baseline cross-sectional analyses of cohort studies that reported the crude prevalence of metabolic syndrome or provided sufficient data to calculate it (i.e., number of cases and sample size) in the general adult population (aged ≥18 years). Eligible studies were not restricted by geographic location and were required to have used probability-based sampling methods and to include a minimum of 30 participants. We included studies regardless of the diagnostic criteria used to define metabolic syndrome. Only studies conducted in general populations, without restriction to specific characteristics or health conditions, were considered.

Two investigators independently performed the selection of records based on titles and abstracts; followed by selection based on the full text through the Rayyan online application. Disagreements were solved by discussion and consensus. Four pairs of investigators performed the methodological quality assessment of finally included studies with the Joanna Briggs Institute tool for prevalence studies (Supplementary Table 7)30. Disagreements in each pair of investigators were solved by discussion.

Four pairs of investigators independently extracted relevant data. Disagreements in each pair of investigators were solved by discussion. Data were double-checked by a senior investigator for accuracy. Using a pretested form, we extracted bibliometric information, country of recruitment, period of participants’ inclusion, representativeness of the sample (national, subnational), mean or median age of the population, proportion of males, proportion of participants living in an urban area, diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome, number of participants included in the study and number with metabolic syndrome. When possible, we extracted data by age group, sex, setting, and year of data collection.

Data analysis

We used a Bayesian multilevel logistic regression model to estimate the global, regional, and national prevalence of metabolic syndrome between 2000 and 2023, separately for men and women (Supplementary Text 1). The modelling approach is aligned with previously published statistical and substantive frameworks2,3,4,35. This hierarchical strategy accounted for the nested structure of the data, with prevalence estimates from individual studies clustered within countries, regions, and super-regions.

The outcome was modelled as the number of individuals with metabolic syndrome out of the total number examined, assuming a binomial distribution with a logit link function. Several fixed effects were incorporated to account for population and study-level characteristics. Age was modelled as a continuous variable, centred at 50 years to improve model convergence and interpretability. To capture non-linear relationships between age and prevalence, we applied natural cubic splines. For men, knots were placed at 35, 65, and 75 years, with boundary knots at 20 and 80 years. For women, knots were located at 40, 60, and 65 years, with the same boundary knots. These placements were informed by epidemiological evidence suggesting that metabolic syndrome and its cardiometabolic components exhibit non-linear age trajectories, with key inflection points around midlife and older age4,35.

Additional fixed effects included the national representativeness of the study (national vs subnational), urbanicity (proportion of the population living in urban areas), gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (log-transformed), and the diagnostic definition of metabolic syndrome. For men, diagnostic categories included the JIS with waist circumference thresholds of 90 cm or 94 cm, as well as other definitions. For women, definitions included the JIS threshold of 80 cm and others. An interaction between representativeness and log GDP was incorporated to assess whether the influence of economic context on prevalence varied by study coverage, capturing potential inconsistencies between national economic indicators and subnational data.

Random effects were introduced at multiple geographic levels to reflect spatial clustering and unmeasured heterogeneity. Random intercepts and age slopes were included at the super-regional level, allowing the age-prevalence association to vary across broad epidemiological zones. Nested random intercepts at subregional and national levels were also included to account for additional within-region and within-country variation not explained by fixed effects.

Priors were specified based on established epidemiological knowledge and assumptions about the distribution and determinants of metabolic syndrome. For the model intercept, we applied informative priors to reflect plausible global prevalence values under the JIS definition8, anchoring the model without overly constraining it. For fixed effects, weakly informative priors were applied, centred at zero but allowing moderate variation, to reflect the well-documented associations of age, urbanicity, and GDP with metabolic syndrome while remaining conservative. Priors for the interaction term between GDP and representativeness were centred around a null effect. Priors on random effect standard deviations were weakly regularizing, helping to stabilize variance estimation without suppressing meaningful heterogeneity. Correlations between intercepts and age slopes at the super-regional level were also modelled, with structured priors permitting moderate correlation.

Models were implemented using the brm function from the brms package (version 2.22.0) in R (version 4.3.3), with Stan as the backend via cmdstanr. Estimation used four parallel Markov chains, each with 5000 iterations and a 2500-iteration warm-up. Posterior distributions were sampled using Hamiltonian Monte Carlo, yielding 10,000 post-warm-up draws.

Posterior predictions were generated to estimate the prevalence of metabolic syndrome across all countries and territories included in the study, including those without primary data. The predictions were informed by a set of time-varying covariates (age distribution, GDP per capita, and level of urbanicity) specific to each year between 2000 and 2023. This enabled the model to capture year-to-year changes in the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in relation to shifting demographic and socioeconomic conditions. In countries with available data, estimates incorporated both fixed effects and country-specific random effects. In countries without direct data but located in regions with available data, predictions were based on fixed effects and random effects at the regional and super-regional levels. For countries with no data at the country or regional level, predictions relied on fixed effects and super-regional random effects. This hierarchical modelling structure allowed estimates to borrow strength across geographic levels while maintaining internal coherence and accounting for data sparsity. Uncertainty was expressed through 95% CrI derived from the posterior distributions, capturing both parameter uncertainty and structural variability across time and space.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data used in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo repository under accession code https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15923329. The data are publicly available and unrestricted. No individual-level raw data were collected; therefore, no privacy restrictions apply. All authors had access to the data used in this study.

Code availability

The R code for modelling the prevalence of metabolic syndrome is available for download at: Github: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1759979336.

References

Cornier, M. A. et al. The metabolic syndrome. Endocr. Rev. 29, 777–822 (2008).

GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1223–1249 (2020).

GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1736–1788 (2018).

GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 13–27 (2017).

Alberti, K. G. et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 120, 1640–1645 (2009).

O’Neill, S. & O’Driscoll, L. Metabolic syndrome: a closer look at the growing epidemic and its associated pathologies. Obes. Rev. Off J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 16, 1–12 (2015).

Noubiap, J. J. et al. Global, regional, and country estimates of metabolic syndrome burden in children and adolescents in 2020: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 6, 158–170 (2022).

Noubiap, J. J. et al. Geographic distribution of metabolic syndrome and its components in the general adult population: A meta-analysis of global data from 28 million individuals. Diab. Res. Clin. Pract. 188, 109924 (2022).

International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, https://diabetesatlas.org/resources/idf-diabetes-atlas-2025/ (2025).

Forouzanfar, M. H. et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990-2015. Jama 317, 165–182 (2017).

Whelton, P. K. et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex.: 1979) 71, 1269–1324 (2018).

Swinburn, B. A. et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 378, 804–814 (2011).

United Nations, D. o. E. a. S. A., Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: the 2014 Revision, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/826634/files/WUP2014-Report.pdf (2014).

Lee, K. K. et al. Adverse health effects associated with household air pollution: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and burden estimation study. Lancet Glob. health 8, e1427–e1434 (2020).

Li, N. et al. Association between household air pollution and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 30, 5312–5346 (2023).

Popkin, B. M., Adair, L. S. & Ng, S. W. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr. Rev. 70, 3–21 (2012).

Jaacks, L. M. et al. The obesity transition: stages of the global epidemic. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 7, 231–240 (2019).

Lovejoy, J. C. & Sainsbury, A. Sex differences in obesity and the regulation of energy homeostasis. Obes. Rev. Off J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 10, 154–167 (2009).

Després, J. P. et al. Abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome: contribution to global cardiometabolic risk. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 1039–1049 (2008).

Abbate, M. et al. Socioeconomic Inequalities in metabolic syndrome by age and gender in a Spanish working population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910333 (2021).

Adjei, N. K. et al. Ethnic differences in metabolic syndrome in high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 25, 727–750 (2024).

Dallongeville, J. et al. Household income is associated with the risk of metabolic syndrome in a sex-specific manner. Diab. Care 28, 409–415 (2005).

Lim, L. L. et al. Gender-associated cardiometabolic risk profiles and health behaviors in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional analysis of the Joint Asia Diabetes Evaluation (JADE) program. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 32, 100663 (2023).

Marchesini, G. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndrome. Hepatology 37, 917–923 (2003).

GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388, 1659–1724 (2016).

Grundy, S. M. Metabolic syndrome update. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 26, 364–373 (2016).

United Nations Environment. How to Develop a Non-Motorised Transport Strategy or Policy. https://nmttoolkit.itdp.org/ (2019).

Shi, Q. et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 403, e21–e31 (2024).

NHLBI. Metabolic Syndrome: Causes and Risk Factors. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/metabolic-syndrome/causes (2022).

Munn, Z., Moola, S., Lisy, K., Riitano, D. & Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 13, 147–153 (2015).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 10, 89 (2021).

World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (2023).

World Bank. Urban Population (% of Total Population). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS (2023).

McGowan, J. et al. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 75, 40–46 (2016).

Finucane, M. M., Paciorek, C. J., Danaei, G. & Ezzati, M. Bayesian estimation of population-level trends in measures of health status. Stat. Sci. 29, 18–25 (2014).

Bigna, J. J. et al. R code for worldwide trends in metabolic syndrome from 2000 to 2023: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17599793 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and study design: JJN, JRN and JJB. Search strategy: J.J.N. and J.J.B. Study selection: J.J.N. and J.J.B. Data extraction: U.F.N., E.L.Y., D.N.T., A.T.N., F.T., A.J.F., A.L.N., and J.R.N.k. Data management, synthesis, and analysis: JJB. Data interpretation: J.J.N., J.R.N., and J.J.B. Manuscript drafting: J.J.N. and J.J.B. Literature management: U.F.N., D.N.T., A.L.N., J.R.N.k., F.T., A.J.F., and J.J.B. Manuscript revision and review: J.J.N., J.R.N., U.F.N., E.L.Y., D.N.T., A.T.N., F.T., A.J.F., A.L.N., J.R.N.k., and J.J.B. Accepted the final version of the manuscript: J.J.N., J.R.N., U.F.N., E.L.Y., D.N.T., A.T.N., F.T., A.J.F., A.L.N., J.R.N.k., and J.J.B. Guarantors of the review: J.J.N. and J.J.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JJB reports serving as a medical advisor to Sanofi. This role is unrelated to the submitted work and had no influence on the study design, data analysis, interpretation, or manuscript preparation. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xiaochen Dai, Kaijian Hou, Felix Teufel, and Yilin Yoshida for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Noubiap, J.J., Nansseu, J.R., Nyaga, U.F. et al. Worldwide trends in metabolic syndrome from 2000 to 2023: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Nat Commun 17, 573 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67268-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67268-5