Abstract

Coastal communities around the world are becoming increasingly vulnerable to climate change driven natural hazards. Yet, a global scale coastal vulnerability assessment has not been attempted to date. Here, by employing currently available global datasets together with the widely used Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI) approach, we assess present-day coastal vulnerability at the global scale. Our country level assessment shows that median coastal vulnerability is highest in Aruba, Benin, Togo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba, Sri Lanka, Nigeria, French Guiana, Ghana and Liberia. At the IPCC AR6 region scale, Central North America, and Northern South America emerge as the regions with the highest median coastal vulnerability. Results at both country and regional scales indicate that tropical and subtropical regions are more vulnerable to coastal hazards. In countries with High or Very High median CVI, the dominant contributors to present-day coastal vulnerability are geomorphology, mean tidal range, and coastal slope.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The coastal zone, where land meets ocean, is arguably one of the world’s most dynamic environments. A variety of geomorphological features are present in these coastal environments, including rocky beaches, cliffs, soft-shores, hilly or flat coastal plains, narrow or wide coastal shelves1, supporting a diverse range of ecosystems such as mangroves and coral reefs. Coastal zones are also characterized by their high biological productivity and biodiversity, making them important for both ecological balance and human livelihoods. Nearly 10% of the global population currently lives in the coastal zones that are within 10 m elevation from mean sea level (MSL) (which is known as Low Elevation Coastal Zone (LECZ)2,3), with recent studies projecting that the global LECZ population might exceed 1.4 billion by 20603.

However, coastal environments face significant challenges from hazards such as coastal flooding and erosion, which threaten both physical systems (e.g., geomorphology, ecosystems, infrastructure) and socioeconomic systems (e.g., livelihoods, population centers, marine and coastal industries)4. These hazards are caused by both natural and human-induced pressures (e.g., urbanization, overexploitation of coastal resources such as sand mining, removal of coastal vegetation)5. The impacts of climate change, including accelerated sea level rise, more frequent and severe storms are expected to increase the frequency and intensity of coastal hazards over time6,7,8.

The Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states with high confidence that most regions of the world will experience an increase in coastal flooding and erosion of sandy coasts over the twenty-first century9. To efficiently prioritize coastal adaptation efforts, it is necessary to have an understanding of not only the hazard level but also the level of coastal vulnerability. The most common approach used to assess coastal vulnerability is the multivariate Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI)10,11. The CVI is a unitless index that expresses the relative vulnerability of a specific location to coastal flooding and/or erosion12,13 in comparison to all other locations considered in the study.

CVI was first introduced by Gornitz (1991)14 to flag the highly vulnerable areas of the eastern coast of the United States to future sea level rise. To determine the CVI, various indicators are used that supposedly each plays a role in the process of flooding and/ or erosion, including geomorphology, geology, coastal slope, coastal relief, wave height, and relative sea level change. These indicators can contain qualitative or quantitative information, at different spatial scales and units14. At a given location, each indicator is assigned a rank from 1 (Very Low) to 5 (Very High) to represent the level of vulnerability associated with its value/ characteristics. These indicator ranks are then aggregated to compute values of the Coastal Vulnerability Index (CVI). Calculated CVI values are then classified into one of five vulnerability classes (i.e., Very Low, Low, Moderate, High and Very High).

This approach was subsequently used by different authors with or without modifications to the original method to assess the coastal vulnerability at some locations in US15, Italy12,16,17, Croatia18, Greece19,20, Brazil21,22, Spain10,23, India24,25,26,27,28,29, Bangladesh30, China31, Ghana32,33, Indonesia34,35, Malaysia36, Australia37,38. Majority of these CVI studies are carried out at the local scale, while some studies focus on the regional scale (i.e., West African region39, Mediterranean region40). The main modifications observed in the later studies are; use of different indicators based on the local area (e.g., Pantusa et al. (2022)17 used additional indicators such as emerged beach width, river discharge, dune, vegetation behind the back beach; Simac et al. (2023)11 modified the method by using storm frequencies and coastal orientation as indicators instead of wave height and shoreline change), the approach used in assigning the ranks for vulnerability (from 1–5) to the indicators (e.g., López et al. (2016)23 assigned rank 5 for vulnerability if the erosion rate is more than 1 m/year while Thieler and Hammar-Klose (2000)15 assigned rank 4 if the erosion rate is between 1–2 m/year), method of computing the values of CVI using the ranks given to indicators (e.g., taking the square root of the product mean of the ranks or taking the arithmetic mean of the ranks to compute CVI) and finally the number of vulnerability classes defined (e.g., Addo (2013)32 used 3 classes (Low, Moderate and High), Pantusa, et al. (2022)17 used 4 classes (Low, Moderate, High and Very High) while López et al. (2016)23 used 5 classes (Very Low, Low, Moderate, High and Very High)). Further, some recent studies19,33,41 have modified the original CVI method, including socioeconomic indicators such as population density, road density, coastal protection, tourist arrivals, etc., together with the aforementioned physical indicators to calculate the Integrated Coastal Vulnerability Index (ICVI).

Although coastal vulnerability is a globally relevant issue, vulnerability assessments undertaken to date have mostly focused on the local to regional scale, likely because these are the scales at which coastal zone management measures are designed and implemented. A global-scale assessment of coastal vulnerability, which is hitherto lacking, can provide a first pass, high-level overview of vulnerable regions of the world, such as that often needed for informing macro-scale decisions and policies. This study is an attempt to address this knowledge gap.

In this study, the vulnerability of the global coastline to erosion and coastal flooding is assessed by considering four methods14,15,23,42 suggested in the literature. These four methods share similar criteria for indicator selection, though they use slightly different parameters (e.g., Lopez et al. (2016) and Thieler and Hammar-Klose (2000)15,23 use coastal slope parameter as the indicator to represent the coastal elevation, while Shaw et al. (1998)42 and Gornitz (1991)14 use coastal relief). The indicators used in all four methods are well-suited for global-scale assessments, providing a consistent basis for comparison across regions. Further, all these methods use a similar method in calculating the overall CVI (i.e., by taking the square root of the product mean of the ranks of each indicator). Additionally, the availability of required input data at relatively uniform spatial resolution makes these four methods practically viable for our analysis. The CVI methods used by Lopez et al. (2016) and Thieler and Hammar-Klose (2000)15,23 use six geophysical and coastal forcing indicators (i.e., geomorphology, coastal slope, relative sea level change, shoreline change, mean tidal range, and wave height) to calculate the CVI, while those used by Shaw et al. (1998)42 and Gornitz (1991)14 use seven indicators (i.e., geomorphology, geology, coastal relief, relative sea level change, shoreline change, mean tidal range, and wave height) related to the geophysical and hydrometeorological characteristics of the coasts. This study exploits increasingly available open global datasets to extract data for each indicator at 362,424 locations spaced at 1 km intervals along the global coastline to assess the vulnerability of the global coastline to coastal flooding and erosion, under present-day conditions. Using these data, we first calculate CVI under the aforementioned four methods and perform a CVI class comparison with previously reported local and regional studies to identify the optimal method for a global scale assessment. The CVI calculated globally at 1 km along coast resolution using this optimal method is then adopted to assess coastal vulnerability at the country level, the IPCC AR6 region level, and per coastal typology type. Finally, the contribution of different CVI indicators to the overall CVI is investigated at the country level to identify the dominant contributors.

Results

Comparison of global CVIs

First, we compare our CVI classes computed at the global scale with those reported in previous local and regional CVI studies that use higher resolution data. The comparison poses several challenges, such as differences in the input data resolutions, different indicators used, different methods of assigning vulnerability ranks to the indicators, different output spatial resolutions of the studies, and different numbers of vulnerability (CVI) classes employed. Therefore, our globally computed CVIs need to be first aggregated to the same output resolution (see Table 1) as the local/regional studies, where necessary (e.g., Dada et al. (2024)39, Addo (2013)32, Abuoda et al. (2006)37), and then rescaled to the local or regional scale for meaningful comparison. For instance, in Dada et al. (2024)39, CVIs are calculated at nearly 25 km intervals, while our global CVIs are calculated at each 1 km. Therefore, to enable a meaningful comparison with Dada et al.’s (2024)39 CVIs, we assign the median value of all global CVI points within each 25 km segment as the representative global CVI for that coastal segment to match the spatial resolution. The rescaling here is done by reclassifying the globally computed CVIs, which are within the same area of a local/regional study to be compared with, to be in line with the number of CVI classes adopted in that local/regional study. Then, the rescaled globally computed CVI classes in the local/regional area are compared with the corresponding local/regional CVI classes.

The local/regional studies used here for the comparison are: the CVI assessments reported for the Barcelona coast10, West African coastline39, Accra region in Ghana32, Illawarra coast, Australia37 (for more details about these local/regional studies, please see Table 1).

Rescaled global CVI classes (i.e., CVI classes obtained by reclassifying the CVI values into the same number of classes as in the Koroglu et al.’s (2019)10 study, using only the CVI value range in that area) for the Barcelona coast were compared with the Koroglu et al.’s (2019)10 study that calculates CVIs using the same four methods used in this study, at the same output spatial resolution (i.e., at 1 km interval) but using higher resolution input data. This point-wise comparison shows the highest agreement (62%) in CVIs computed (in both global and local assessments) using Lopez et al. (2016)23 CVI method, with the other three CVI methods yielding agreements below 50% between rescaled global and local CVI classes (Fig. 1a).

a for the Barcelona coast; b for the West African coast; c for the Accra region, Ghana; d for the Illawarra coast, Australia. M1, M2, M3 and M4 in Fig. 1 (a, b) correspond to the methods suggested by Lopez et al. (2016)23, Thieler and Hammar-Klose (2000)15, Shaw et al. (1998)42 and Gornitz (1991)14. VL, L, M, H and VH in Fig. 1 (c, d) represent Very Low, Low, Moderate, High and Very High vulnerability classes, respectively.

To compare the global CVIs with the regional CVIs for the West African coast presented by Dada et al. (2024)39, which has nearly 25 km (0.25 degrees) output resolution, our globally computed CVIs (at 1 km resolution) are first aggregated into 25 km resolution by taking the median CVI value for each 25 km coastal segment. The aggregated global CVIs for the same regional study region (i.e., West African coast starting from Mauritania till the boundary of Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea) are then rescaled following the same rescaling philosophy adopted for Koroglu et al.’s (2019)10 Barcelona study. The point-wise comparison of aggregated and rescaled global CVI classes with Dada et al.’s (2024)39 regional CVI classes shows similar levels of agreement (20%–25%) for all four CVI methods used, with Shaw et al.’s (1998)42 method showing a slightly higher agreement (Fig. 1b).

To compare our globally computed CVI classes with those computed by Addo (2013)32 for the Accra region, Ghana, the median of the globally computed CVIs for each of the three different sub-regions in Addo (2013)32 (i.e., West, Central, and East Accra) is calculated and rescaled to the Accra region. In this comparison, while global CVI classes from all four methods agree with each other in all three sub-regions, they only agree with the regional CVI classes computed for the Central Accra region (Fig. 1c).

Abuoda et al. (2006)37 present CVI classes for six bay areas along the Illawarra coast in Australia. The median values of our globally computed CVIs for these 6 bay areas, which were calculated by taking the median CVI of all computational points falling within each bay area, are rescaled to the relevant region (i.e., the whole Illawarra region) and classified into four CVI classes (i.e., to be in line with Abuoda et al.’s (2006)37 study). These rescaled CVI classes are then compared with Abouda et al.’s (2006)37 locally computed CVI classes. The rescaled global and local CVI classes agree for 3 CVI methods (i.e., Lopez et al. (2016)23, Shaw et al. (1998)42, Gornitz (1991)14) for three sites (Bulli, Perkins, and Seven Mile) (Fig. 1d).

Several factors may explain why the percentage agreements between our rescaled global CVI and the local/regional CVI results reported in previous local/regional studies are not very high (in the range of ~20%–60%). These factors include differences in the approach used to rank indicator variables at global versus local/regional scale studies, variations in input data resolution (for example most of the local studies are carried out using local datasets that have a higher resolution than most of our global datasets), and discrepancies in the spatial resolution at which CVIs are calculated (e.g., CVIs are calculated at about 1 km in our study while in Dada et al. (2024) CVIs are calculated at 25 km interval). Therefore, despite the percentage agreements not being very high, this comparison remains valuable as it highlights the applicability of different CVI methods, previously proposed for local/regional study areas, to global-scale CVI calculations using global datasets.

Based on the above comparisons, the CVI method that appears to perform best across the four considered comparison cases is that proposed by Lopez et al. (2016)23, especially at a spatial resolution similar to that adopted in our study (see Fig. 1a). Therefore, only the global CVIs calculated by Lopez et al.’s (2016)23 CVI method are used in our further analysis and hereon referred to as ‘the global CVIs’.

Present-day global CVIs

The global CVIs under present conditions are computed for the global coastline at the country level, for IPCC AR6 regions, and across different coastal typologies. The median, 10th, and 90th percentile CVI values for each country or IPCC region are determined by calculating the median, 10th and 90th percentile CVI values of all computational points along the coastline of a given country or IPCC AR6 region. Coastal typologies of the computational points are extracted from the global coastal typology dataset published in Durr et al. (2011)43. The median, 10th and 90th percentile CVI per typology type is calculated using all the computational points categorized into the respective typology type, regardless of their spatial locations. These CVI values are then classified into each of the five CVI classes, which are defined by dividing the CVI values (i.e., between 0.7–30.6) of all the computational locations along the global coastline into 5 equal percentiles (i.e., Very Low = 0–20% (0.7–6.1); Low = 20%-40% (6.1–9.1); Moderate = 40%–60% (9.1–12.2); High = 60%–80% (12.2–14.1); Very High = 80%–100% (14.1–30.6)).

Country level CVIs

Figure 2 presents computed median, 10th and 90th percentile coastal vulnerability levels (CVIs), ranging from Very Low to Very High class at the country level. Figure 2a, which shows country-median CVI classes indicates that coastal vulnerability is higher (High/Very High vulnerability classes) in tropical (between Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn) and subtropical regions (between Tropic of Cancer/Capricorn and 35° North/ South) of the world, where most of the global south countries of the world are also to be found.

a Median CVI class, b 10th percentile CVI class and c 90th percentile CVI class per country. Blank base map was created using publicly available World Countries Generalized shapefile data (World Countries Generalized | ArcGIS Hub)58.

With respect to the computed median CVI classes, of the 146 countries analyzed, 19 fall into the Very High vulnerability class. Out of these Very High vulnerable countries, eight are located in the West African region (Benin, Togo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, Ghana, Liberia, the Congo, and Côte d’Ivoire), four are in the South American region (Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana), two are located in the Caribbean sea (Aruba, and Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba), four are located in Asia (Iraq, Oman, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan), and one is in the Atlantic Ocean (Bahamas). Countries that fall into the Very Low median CVI class are mainly located in Europe, including Norway, the United Kingdom, Slovenia, Croatia, Greece, Belgium, etc. This classification arises because most computational points in these countries have lower CVI values compared to those along the coastlines of other countries. Consequently, their country-median CVI values fall into the Very Low vulnerability category, in a global sense. It is important to note that although these countries may fall in the very low vulnerability category in comparison with other countries in the world, this does not necessarily mean that the coasts of these countries are not vulnerable to coastal hazards. Moreover, it is important to emphasize that our study did not include many small islands (e.g., Caribbean islands, Pacific islands) due to input data limitations (see Supplementary Table S1).

Note that country-level CVI classes in Fig. 2a are median values and thus do not provide insights into locally occurring extreme CVI values. To better capture the variation around the median CVI, country-level median CVIs should be interpreted together with the extreme values, represented here by the 10th and 90th percentile CVI classes for each country (see Fig. 2b, c). This is especially relevant for countries with relatively long coastlines and diverse coastal geomorphology, where local conditions can vary considerably. As a result, a country with a long coastline, such as Myanmar, with its vulnerable southern delta region, but elsewhere less vulnerable long coastline, gets colored green (Low vulnerability), while a country with a short coastline, such as Iraq, gets colored red (Very High vulnerability). Also, countries that have a median CVI classification of Very low vulnerability may well contain local areas that are highly vulnerable to coastal hazards, as can be seen by comparing Fig. 2a, c. Therefore, a low median vulnerability at the country level does not exclude the possibility of a locally highly vulnerable coastline stretch. Conducting vulnerability assessments at the local scale is essential for informing effective and site-specific coastal management planning.

CVIs for IPCC AR6 reference regions

The computational points considered in the CVI assessment are distributed over 35 IPCC AR6 reference regions44. The median CVI class calculated for each region is shown in Fig. 3. Out of the 35 regions, two regions fall into the Very High median CVI class (i.e., Central North America (CNA) and Northern South America (NSA)), while 14 regions fall into the High median CVI class. Here, too, it can be seen that regions with High and Very High median CVIs are located mostly in the tropical and sub-tropical regions of the world. The 10th and 90th percentile CVI classes for all IPCC AR6 regions are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Associated 10th and 90th percentile uncertainty ranges are shown in Supplementary Fig S1. Names of all IPCC AR6 regions are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. Blank base map was created using publicly available World Countries Generalized shapefile data (World Countries Generalized | ArcGIS Hub)58.

CVIs for different coastal typologies

Figure 4 shows the distribution of CVIs (i.e., median, 10th and 90th percentile range, minimum and maximum) for the different coastal typologies suggested by Dürr et al. (2011)43, where the red lines show medians, lower and upper limits of the boxes represent 10th and 90th percentiles, and black whiskers represent minimums and maximums, respectively. Large rivers, lagoons, and arheic emerge as the most vulnerable typologies (with High median CVI). Karst, tidal systems and small deltas are identified as the second most vulnerable typologies (with Moderate median CVI), while fjords and fjaerds are categorized as the least vulnerable typology (with Low median CVI). These high and low CVIs can be explained by the geomorphological characteristics associated with each coastal typology. Fjords and fjareds generally have high slopes and high elevations, making them less vulnerable to erosion and flooding. In contrast, arheic coasts are mostly formed with unconsolidated sediments, making them more vulnerable to erosion. The typology large rivers is mainly located near the deltaic coasts, which are classified as highly vulnerable to coastal flooding and erosion14,15.

Relative contribution of CVI indicators to CVI value

The CVI, as calculated here, is influenced by different CVI indicators contributing to the overall CVI values (i.e., coastal slope, geomorphological characteristics, tidal impacts, wave impacts, relative sea level change, and shoreline change rates). To understand the relative influence of these different indicators on the coastal vulnerability index (CVI) in each country, here we calculate the percentage contribution of each of the six CVI indicators to the CVI at the country level (see Fig. 5). The countrywise relative contributions are calculated as the mean value of contributions of that indicator at all the computational points located in that country’s coastline. Percentage contributions were then calculated as the fraction of the relative contribution of that indicator to the total relative contributions from all six indicators. The 146 countries in the bar chart in Fig. 5 are listed in increasing order of median CVI (i.e., ordered from Very Low CVI countries at the top of the list to Very High CVI countries at the bottom).

In countries with Very High to High median CVIs, the most dominant CVI indicators are geomorphology (19%–26%), mean tidal range (14%-25%), and coastal slope (14%–26%) (see also Supplementary Table S2). In contrast, in most of the countries that fall into Low to Very Low CVI classes, the tidal range is more influential, while the coastal slope has a lower contribution.

This study adopted openly available global data to assess the vulnerability of the global coastline to coastal flooding and erosion under present-day conditions. The commonly used approach to assess the vulnerability level is the coastal vulnerability index (CVI). CVIs were computed globally at 1 km along coast resolution, using four commonly used CVI methods (i.e., CVI methods suggested by Lopez et al. (2016)23, Thieler and Hammar-Klose (2000)15, Shaw et al. (1998)42 and Gornitz (1991)14), and compared with previously reported higher resolution local and regional CVI assessment studies. The best comparisons were obtained with the CVI method suggested by Lopez et al. (2016)23, across the local and regional studies considered, which was consequently adopted to further assess CVI globally at country and IPCC AR6 region levels, and per coastal typology type.

Country-level median CVI analysis indicates that the majority of the most vulnerable countries are located in West Africa, South America and Asia. The top ten countries with the highest median coastal vulnerability at present are: Aruba, Benin, Togo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba, Sri Lanka, Nigeria, French Guiana, Ghana and Liberia, in the descending order. Out of the 35 IPCC AR6 regions, two regions (i.e., Central North America (CNA) and Northern South America (NSA)) emerge as regions with Very High median vulnerability. Results obtained for both the country and IPCC region levels indicate that tropical and subtropical regions are more vulnerable to coastal hazards compared to the temperate, sub-polar and polar regions. However, our analysis excluded numerous small islands due to data limitations, which might have otherwise been identified as highly vulnerable to coastal flooding and erosion. The CVI analysis by coastal typology reveals that large rivers, arheic, and lagoons are the most vulnerable typologies, while fjords and fjaerds emerge as the least vulnerable coastal typologies. The analysis of dominant contributors to the CVI at the country level shows that, in countries with High to Very High median CVIs, the dominant CVI indicators are geomorphology, mean tidal range, and coastal slope.

It should be noted that the results presented in this study are based on the global scale data obtained from previously published global scale studies45,46,47,48, which have coarser resolutions compared to data generally used in local or regional scale assessments. Therefore, while the results of our global scale assessment are useful for gaining a broad overview and insights on coastal vulnerability to inform macro-scale decisions and policies, it is important that local scale decisions are underpinned by higher resolution local vulnerability assessments.

Methods

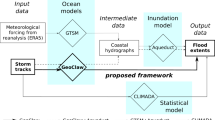

The CVI for the global coastline was calculated using the four commonly used methods suggested by Lopez et al. (2016)23 (M1), Thieler and Hammar-Klose (2000)15 (M2), Shaw et al. (1998)42 (M3) and Gornitz (1991)14 (M4). The global transects system described below in subsection ‘Global transects/ computational points’ was used to define computational points in this study. To calculate the CVI, the methods suggested by Lopez et al. (2016)23, and Thieler and Hammar-Klose (2000)15 have used six indicators (i.e., coastal slope, geomorphology, wave climate/mean wave height, mean tidal range, relative sea level change, and shoreline change), while the methods suggested by Shaw et al. (1998)42 and Gornitz (1991)14 have used seven indicators (i.e., coastal relief, geomorphology, geology, maximum wave height, mean tidal range, relative sea level change, and shoreline change) (see subsection ‘Vulnerability indicators’ below). The values of each vulnerability indicator were extracted at the computational points from the global datasets described in subsections ‘Global data sources’ and ‘Extraction of data’ below. For each indicator, a rank was assigned, following each of the four CVI methods (see Supplementary Table S3). Within each CVI method, the ranks for each indicator were then aggregated to calculate the CVI at each computational point. All four methods used a similar approach in aggregating the ranks of indicators by taking the root mean square value of the product of all the vulnerability ranks assigned for the selected indicators. Finally, the computed CVI values were classified into five different vulnerability classes, by considering all the CVI values calculated at all the computational points along the global coastline and dividing into five equal percentile classes (Very Low = 0–20%, Low = 20%–40%, Moderate = 40%–60%, High = 60%–80%, and Very High = 80%–100%) (details are given in subsection ‘CVI calculation’). Figure 6 presents the overall methodology adopted in this study to calculate the CVIs for the global coastline. These CVI classes calculated by the four methods were then compared with previously reported local/regional CVI studies to select the best-performing method for the global scale application. The CVI calculated for the global coastline using this selected method was further analysed at the country level, IPCC AR6 regional level and for different coastal typologies. Finally, the relative contributions of different indicators to the overall CVI were calculated for each country to gain insights into the dominant indicators in CVI for each country.

D1 to D13 represent the different data used in this study, I1 to I7 represent indicators, and i represents the method from 1–4 (i.e., 1—Method suggested by López et al. (2016)23, 2— Method suggested by Thieler and Hammar-Klose (2000)15, 3—Method suggested by Shaw et al. (1998)42 and 4—Method suggested by Gornitz (1991)14).

Vulnerability indicators

Coastal slope/ coastal relief

The coastal slope (i.e., defined as the cross-shore slope between the depth of closure and first coastal peak, which is identified by finding the first elevation peak landward of the shoreline45) of an area represents its vulnerability to the combined effect of coastal flooding and erosion. Locations with steeper coastal slopes are considered less vulnerable, while those with milder coastal slopes are considered more vulnerable. The coastal relief used in the CVI methods suggested by Gornitz (1991)14 and Shaw et al. (1998)42 was here defined as the maximum elevation of the cross-shore profile up to 1 km landward from the shoreline.

Geomorphology

The geomorphology indicator represents the different landform characteristics and is indicative of the vulnerability to erosion of different landforms such as sandy beaches, cliffs, deltas, and vegetated beaches16,49.

Geology

Geology is used as an indicator in the CVI methods suggested by Gornitz (1991)14 and Thieler and Hammar-Klose (2000)15 to represent the resistance to erosion. Geologies with higher resistance to erosion are considered to be less vulnerable to coastal erosion.

Mean wave height/ maximum wave height/ wave climate

The significant wave height (Hs) is representative of the wave energy acting on beaches10. Coastal environments experiencing higher wave heights are expected to be more vulnerable to coastal erosion and flooding. Of the four CVI methods considered in this study, three methods (Thieler and Hammar-Klose (2000); Shaw et al. (1998); and Gornitz (1991))14,15,42 directly use wave height (mean/maximum) while Lopez et al.’s (2016)23 method introduced a new wave climate indicator, defined as the ratio between square of the 95th percentile significant wave height and square of the threshold significant wave height for storm identification (i.e., taken as the 99.5th percentile significant wave height following the Mendez et al. (2006)50) to represent the vulnerability of coasts to storm erosion.

Mean tidal range

Mean tidal range influences the vulnerability of coasts to coastal flooding and permanent inundation17,23,49 as well as vulnerability to erosion14. The four CVI methods used here consider the contribution of the mean tidal range to vulnerability in different ways. López et al. (2016)23 and Thieler and Hammar-Klose (2000)15 classified micro tidal coasts to be more vulnerable than macro tidal coasts. This is explained by the argument that, in the case of micro tidal coasts, the sea level is always close to the high tide level, and therefore, during storm surge events, the risk of flooding is higher than in the case of macro tidal coasts. On the other hand, Gornitz (1991)14 and Shaw et al. (1998)42 classified macro tidal coasts to be more vulnerable on the premise that higher mean tidal ranges are associated with strong tidal currents.

Relative sea level change

Compared to mean sea level change, relative sea level change includes both the global eustatic sea level rise (SLR) as well as the effects of local tectonic land motion, glacial-isostatic adjustments (GIA), and local subsidence or uplift due to anthropogenic activities10,16. Relative sea level change is associated with the potential for flooding, permanent inundation, and erosion10,14,16,23,49,51. An increase in relative sea level can inundate low-lying coastal areas and also increase the risk of coastal flooding due to storm surges and erosion.

Shoreline change

Coastal environments that show high rates of long-term erosion rates are considered to be more vulnerable to coastal erosion.

Global data sources

The global data sources for each of the above-listed vulnerability indicators, together with their resolutions and the data acquisition periods, are summarized in Table 2. For some datasets, data acquisition periods were not clear or varied for different data, and these are shown in Table 2 as ‘various’ (details can be found in the corresponding references).

Coastal slope and coastal relief were extracted at 1 km resolution from the Global Coastal Characteristics (GCC) database presented by Athanasiou et al. (2024)45. These slope and relief values have been calculated using the Copernicus DEM52. A single dataset for global-scale geomorphology was not found in the literature. Therefore, for the purpose of this study, the geomorphology indicator was developed using nine different datasets. These datasets consist of the coastal slope (D1), coastal relief (D2), presence of coastal vegetation (D3), landcover class (D4), coastline types (e.g., sandy, muddy, rocky) (D6), locations of deltas (D7), locations of estuaries (D8), coastal typologies (D9), and coastal geology (D10) data. The Global Lithological Map (GLiM)46 database was used as the source for extracting the geology characteristics at the computational locations. The gridded version of GLiM has a resolution of 0.5° latitude – longitude.

Mean wave height, maximum wave height and wave climate were calculated using the Significant wave height (Hs) data, extracted from the European Center for Medium Weather Forecasting (ECWMF) ERA547 climate reanalysis data, which has a spatial resolution of 0.25° and a temporal resolution of 1 hour. These (Hs) time series were post-processed to obtain the above indicators.

Mean tidal range was calculated as the difference between mean higher high water (MHHW) and mean lower low water (MLLW) levels in the Global Coastal Characteristics (GCC) database, which has been extracted from Global Tide and Surge Model version 3.0 (GTSMv3.0)53.

Relative sea level change rates were obtained using the Nicholls et al. (2021)54 dataset on global relative sea level change, which has been calculated using four components that define the relative sea level change. These components are satellite-observed sea level change over the period 1993-2015, glacial–isostatic adjustment (GIA), delta subsidence, and city subsidence.

Shoreline change rates were obtained from an updated version of the shoreline change dataset presented by Luijendijk et al. (2018)48. In the updated dataset, some contentious data points (i.e., non-sandy points that had been classified as sandy, and vice versa) have been removed, based on local knowledge and Google Earth satellite imagery. These shoreline change rates have been calculated using the shoreline positions obtained from Landsat satellite images over the 1984–2016 period.

Global transects/ computational points

Computational points for the analysis were adopted from the global transects system used in Athanasiou et al. (2024)45, where the global coastal characteristics (GCC) data are provided for 80 different coastal geophysical, hydrometeorological, and socioeconomic indicators. These transects have been generated with about 1 km spacing along the generalized global coastline vector derived from Open Street Maps (OSM), which is a simplified version of the global coastline, after removing finer features such as rocky outcrops45. Computational points are defined where these transects intersect the global coastline. The GCC database comprises a total of 728,088 data points. However, data for one or more of the indicators required were not available at 365,664 of these data points. Thus, the total number of computational points used in this study was 362,424.

Extraction of data

Coastal slope (D1), relief (D2), and mean tidal range (D5) data for this study were directly extracted from the Global Coastal Characteristics (GCC) database, as our computational points coincide with the GCC data points. For other indicators, a nearest neighbor analysis (with appropriate search radii) was conducted to extract the most appropriate value. A maximum search radius of 0.01° (~ 1 km at the equator) was used to extract the coastline type (D6) from the Hulskamp et al. (2023)55, while a maximum search radius of 1° (~ 108 km at the equator) was used to extract data from the coastal typology (D9) database43 and the global lithology (D10) database (GLiM)46. For the wave height indicator, significant wave heights (D11) were extracted from ECMWF ERA5 wave data, which are available at a grid resolution of nearly 30 km. These offshore wave conditions do not represent the local wave conditions at the selected computational locations. However, considering the computational expense of transforming 30 years of hourly offshore wave data to the considered 362,424 nearshore points, which is beyond the scope of this study, wave data were extracted from the ERA5 data point nearest to each computational point, within a maximum search radius of 1° (~ 108 km at the equator). Using these hourly wave height time series, the necessary indicator values were computed at each computational point, including the mean wave height, the maximum wave height (i.e., average and maximum of 30 year wave time series for mean wave height and maximum wave heights), and the wave climate parameter, which is defined as the ratio between the square of the 95th percentile significant wave height to the square of the storm threshold significant wave height (taken as 99.5th following Mendez et al. (2006)50). The mean tidal range was calculated by taking the difference between the mean higher high water (MHHW) level and the mean lower low water (MLLW) level (D5) extracted from the GCC database45. Relative sea level change rates (D12) were extracted from the nearest point from the relative sea level change rates dataset by Nicholls et al. (2021)54, within a maximum search radius of 1° (~ 108 km at the equator). Shoreline change rates (i.e., erosion/accretion rates) (D13) were extracted directly from the aforementioned updated Luijendijk et al.‘s (2018)48 dataset, as GCC points and Luijendijk et al.‘s (2018)48 data points coincide, albeit at a 1:2 along coast scale (i.e., one GCC point for every two Luijendijk et al. (2018)48 points).

CVI calculation

Extracted characteristics data for all the indicators at each computational point were then considered to assign the vulnerability ranks (i.e., from 1 (Very Low) to 5 (Very High)) for each vulnerability indicator, following the rank assigning methods in the four CVI methods used here14,15,23,42. Assigning the ranks for different vulnerability indicators was adopted from the original studies presenting the four CVI methods. The ranking methods of all four CVI methods are summarized in Supplementary Table S3.

After assigning ranks of 1 to 5 for indicators, these ranking values were aggregated to calculate the coastal vulnerability index (CVI) at each computational point. Two approaches have been used in the literature to calculate CVI, which are the square root of the product mean or the arithmetic mean of the ranking values of the indicators. In the original studies of the four CVI methods adopted in this study, the approach of the square root of the product mean of indicator ranking values has been used to calculate CVI. Hence, this same approach was also adopted in this study to calculate the CVI at the computational points, and is presented in Eq. (1) below:

where Ri = ranking value for ith indicator, n = number of indicators.

The calculated CVI value at each computational point was then classified into one of five vulnerability classes defined as Very Low, Low, Moderate, High, and Very High. These five classes were defined based on the equal percentile ranges of all the CVI values calculated at all 362,424 computational points (i.e., Very Low: 0–20%, Low: 20%-40%, Moderate: 40%-60%, High: 60%-80%, Very High: 80%-100%). All data extraction, data processing, calculation and post-processing of results were carried out with Python 3.11 using geopandas, pandas, numpy, xarray and matplotlib packages. The overall CVI calculation method is presented in Fig. 6.

Comparison of global CVIs

The globally computed CVIs from four methods were compared with available higher resolution CVI studies previously carried out at the local and regional level10,32,37,39. However, a direct comparison of CVI classifications could not be performed in all cases due to variation in the number of classified CVI classes (i.e., some studies used five CVI classes10,23,39,49,56 while others used three32 or four CVI classes14,15,42,57). Furthermore, the vulnerability classes are defined as percentiles in the total CVI range obtained in the study area. The range of local or regional CVI values may be smaller than that of global-scale CVI values. Hence, for a local or regional area, the CVI values calculated from global data should be classified using only the range of CVI values in that specific area. For comparison with local/ regional studies, the globally computed CVIs were rescaled to the same relevant area to obtain comparable CVI classes. The rescaling of global CVI values was performed by reclassifying the globally computed CVIs within each local or regional study area into the same number of classes used in the respective local/regional study, as well as only based on the range of CVI values from the computational points within that specific area. This comparison revealed that the CVI method that appears to perform best across the four considered comparison cases is the method proposed by Lopez et al. (2016)23 The global CVI calculated with this method is used for further analysis of CVI at the country, IPCC AR6 regional level and for different coastal typologies.

Analysis of CVI at country level, for IPCC regions and for coastal typologies

The CVIs calculated using the method suggested by Lopez et al. (2016)23, were analyzed at the country level, at IPCC AR6 reference region level and per coastal typology. However, a number of small islands, ice-covered coastlines (such as Antarctica) had to be excluded from our analysis due to data limitations. The list of countries (following the listing in the International Organization of Standards (ISO) 3166) with a coastline that are included in the Global Coastal Characteristics (GCC) dataset but not included in our analysis are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Country-level statistics and IPCC AR6 region-level statistics of the CVI classes derived here comprised the median, 10th, and 90th percentile CVI. Computational points located along the coastline of each country and IPCC AR6 region were identified using the “world countries” shapefile and “IPCC AR6 reference land and ocean regions” shapefile, respectively. The World countries shapefile was downloaded from “Arc-GIS Hub“58, and IPCC AR6 WGI reference land and ocean regions shapefile was downloaded from Copernicus Earth System Science Data44. The IPCC AR6 reference regions are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S2. Coastal typologies at each computational point were extracted from the coastal typology shapefile provided in Durr et al. (2011)43. Based on these typology types, all the computational locations are categorized into seven different typology classes (i.e., small delta, tidal system, lagoon, fjord and fjeard, large river, karst, and arheic). A schematic representation of the physical characteristics of these seven typologies is shown in Supplementary Fig. S3.

Contribution of different CVI indicators to the overall CVI

Relative contributions (in percentage) of different vulnerability indicators to the overall CVI were calculated first by calculating the contribution from each indicator to the CVI at each computational point. This contribution from each indicator was calculated by dividing the normalized rank of that indicator by the normalized overall CVI at that computational point (see Eq. (4)). The normalized rank of an indicator and the normalized overall CVI at each computational point were calculated using Eq. (2) and Eq. (3):

where \({minimum\; rank}=1\) and \({maximum\; rank}=5\)

Here, the minimum and maximum CVIs are defined by:

\({minimum}\; {CVI}=\,\root{{2}}\of{\frac{{1}^{n}}{n}}\) (where n = number of indicators) = \(\root{{2}}\of{\frac{1}{6}}=0.41\) and \({maximum\; CVI}=\,\root{{2}}\of{\frac{{5}^{n}}{n}}\) = \(\root{{2}}\of{\frac{{5}^{6}}{6}}=51.03\)

The individual contribution from each of the six indicators at each computational point was calculated using Eq. (4) below.

Subsequently, the contribution from an indicator to the overall CVI for each country was calculated by considering all the contributions (from that indicator) at all computational points located along that country’s coastline and by taking the mean of all these contributions from all relevant points. These mean contributions for the six indicators were then used to calculate the percentage contribution from each indicator to the CVI at the country level, as shown in Eq. (5) below.

Limitations

The study offers new insights into the vulnerability of global coastlines to coastal flooding and/ or erosion. However, the spatial scale of this study imposes unavoidable challenges that are common among such large-scale assessments.

The main limitation is the variable resolution of the input data sources. Some of the coarser resolution data, such as wave heights obtained from ERA5, geology data obtained from GLiM, might not accurately represent local conditions at computational points spaced at 1 km interval. Vulnerability indicators derived from the GLiM dataset (geology) and ERA5 wave data (mean significant wave height, maximum significant wave height, wave climate) have a resolution of 0.5° latitude-longitude, equivalent to 54 km at the equator. For the indicators that are directly extracted from the GCC dataset45, the limitations in the original datasets (such as: biases of DEMs, especially in highly vegetated areas, land cover data extracted from the buffer zone around the transects) inevitably propagate into this study as well (for more details, see Athanasiou et al. (2024)45). Especially, the countries that fall into the Very Low median CVI class should be interpreted with caution for two reasons; (a) because these country level classifications are relative to the full range of CVI values computed along the entire global coastlines, and hence a Very Low classification does not necessarily mean that coastlines of these countries are not vulnerable to coastal hazards, and (b) because country-median CVIs may mask local areas that may have high CVI values, which may be particularly the case in countries with long coastlines. While very large-scale assessments, such as the one presented here, are essential for guiding macro-scale decisions and policies, they will most likely not be very accurate at the local scale. Local scale, on-the-ground decisions would be better served by high-resolution vulnerability assessments that are tailored to the local context.

Data availability

The raw data used in this study is openly available online. The coastal slope, relief, mangrove presence, landcover types, and tide data can be accessed via https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8200199. Coastal transect types data used to obtain the geomorphological characteristics is openly available at https://zenodo.org/records/7582197. Global deltas and global estuary datasets can be downloaded via https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-7-773-2019-supplement and https://data.unep-wcmc.org/datasets/23. ERA5 wave data is available through Copernicus website https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=download, relative sea level change rates are available through https://zenodo.org/records/4434773 and the shoreline change rates can be accessed through https://aqua-monitor.appspot.com/?datasets=shoreline. The CVI data generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo repository under the accession code: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17513575.

Code availability

Python scripts to generate the result figures in the manuscript are deposited in the Zenodo repository: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17513575.

References

Martínez, M. L. et al. The coasts of our world: ecological, economic and social importance. Ecol. Econ. 63, 254–272 (2007).

McGranahan, G., Balk, D. & Anderson, B. The rising tide: Assessing the risks of climate change and human settlements in low elevation coastal zones. Environ. Urban. 19, 17–37 (2007).

Neumann, B., Vafeidis, A. T., Zimmermann, J. & Nicholls, R. J. Future coastal population growth and exposure to sea-level rise and coastal flooding - a global assessment. PLoS One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118571 (2015).

Bevacqua, A., Yu, D. & Zhang, Y. Coastal vulnerability: Evolving concepts in understanding vulnerable people and places. Environ. Sci. Policy 82, 19–29 (2018).

Sekovski, I., Newton, A. & Dennison, W. C. Megacities in the coastal zone: Using a driver-pressure-state-impact-response framework to address complex environmental problems. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 96, 48–59 (2012).

Pang, T., Wang, X., Nawaz, R. A., Keefe, G. & Adekanmbi, T. Coastal erosion and climate change: a review on coastal-change process and modeling. Ambio 52, 2034–2052 (2023).

Ranasinghe, R. Assessing climate change impacts on open sandy coasts: a review. Earth-Science Rev. 160, 320–332 (2016).

Ranasinghe, R. et al. Climate Change Information for Regional Impact and for Risk Assessment. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.014 (2021).

IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. in Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 3−32 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2021).

Koroglu, A., Ranasinghe, R., Jiménez, J. A. & Dastgheib, A. Comparison of Coastal Vulnerability Index applications for Barcelona Province. Ocean Coast. Manag. 178, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.05.001 (2019).

Šimac, Z., Lončar, N. & Faivre, S. Overview of coastal vulnerability indices with reference to physical characteristics of the Croatian coast of Istria. Hydrology 10, 14 (2023).

Sekovski, I., Del Río, L. & Armaroli, C. Development of a coastal vulnerability index using analytical hierarchy process and application to Ravenna province (Italy). Ocean Coast. Manag. 183, 104982 (2020).

Ramieri, E. et al. Methods for assessing coastal vulnerability to climate change: ETC CCA Technical Paper 1/2011. http://cca.eionet.europa.eu/https://www.eionet.europa.eu/etcs/etc-cca/products/etc-cca-reports/1 (2011).

Gornitz, V. Global coastal hazards from future sea level rise. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 89, 379–398 (1991).

E. R. Thieler & Hammar-Klose, E. S. National Assessment of Coastal Vulnerability to Sea-Level Rise: Preliminary Results for the U.S. Atlantic Coast. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 99-593 https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr00178 (2000).

Pantusa, D., D’Alessandro, F., Riefolo, L., Principato, F. & Tomasicchio, G. R. Application of a coastal vulnerability index. A case study along the Apulian Coastline, Italy. Water (Switzerland) 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/w10091218 (2018).

Pantusa, D., D’Alessandro, F., Frega, F., Francone, A. & Tomasicchio, G. R. Improvement of a coastal vulnerability index and its application along the Calabria Coastline, Italy. Sci Rep 12, 21959 (2022).

Ruži, I. & Dugonji, S. Assessment of the Coastal Vulnerability Index in an Area of Complex Geological Conditions on the Krk Island, Northeast Adriatic Sea. Geosci. MDPI https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences9050219 (2019).

Ramnalis, P., Batzakis, D. V. & Karymbalis, E. Applying two methodologies of an Integrated Coastal Vulnerability Index (ICVI) to future sea-level rise. Case Study: Southern Coast of the Gulf of Corinth, Greece. Geoadria 28, 7–24 (2023).

Tragaki, A., Gallousi, C. & Karymbalis, E. Coastal Hazard Vulnerability Assessment Based on Geomorphic, Oceanographic and Demographic Parameters: The Case of the Peloponnese. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7020056 (2018).

de Andrade, T. S., Sousa, P. H. G., de, O. & Siegle, E. Vulnerability to beach erosion based on a coastal processes approach. Appl. Geogr. 102, 12–19 (2019).

Szlafsztein, C. & Sterr, H. A GIS-based vulnerability assessment of coastal natural hazards, state of Pará, Brazil. J. Coast. Conserv. 11, 53–66 (2007).

López, R. M., Ranasinghe, R. & Jiménez, J. A. A rapid, low-cost approach to coastal vulnerability assessment at a national level. J. Coast. Res. 32, 932–945 (2016).

Hegde, A. V. & Reju, V. R. Development of coastal vulnerability index for Mangalore coast, India. J. Coast. Res. 23, 1106–1111 (2007).

Dwarakish, G. S. et al. Coastal vulnerability assessment of the future sea level rise in the Udupi coastal zone of Karnataka state, west coast of India. Ocean Coast. Manag. 52, 467–478 (2009).

Abijith, D., Saravanan, S. & Sundar, P. K. S. Coastal vulnerability assessment for the coast of Tamil Nadu, India—a geospatial approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 75610–75628 (2023).

Parthasarathy, A. & Natesan, U. Coastal vulnerability assessment: a case study on erosion and coastal change along Tuticorin, Gulf of Mannar. Nat. Hazards 75, 1713–1729 (2015).

Ramakrishnan, R., Shaw, P. & Rajput, P. Coastal vulnerability map of Jagatsinghpur District, Odisha, India: a satellite-based approach to develop two-dimensional vulnerability maps. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 57, 102747 (2023).

Murali, R. M., Ankita, M., Amrita, S. & Vethamony, P. Coastal vulnerability assessment of Puducherry coast India, using the analytical hierarchical process. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 13, 3291–3311 (2013).

Mullick, M. R. A., Tanim, A. H. & Islam, S. M. S. Coastal vulnerability analysis of Bangladesh coast using fuzzy logic-based geospatial techniques. Ocean Coast. Manag. 174, 154–169 (2019).

Yin, J., Yin, Z., Wang, J. & Xu, S. National assessment of coastal vulnerability to sea-level rise for the Chinese coast. J. Coast. Res. 16, 123–133 (2012).

Addo, K. A. Assessing coastal vulnerability index to climate change: the Case of Accra – Ghana. J. Coast. Res. 165, 1892–1897 (2013).

Charuka, B., Angnuureng, D. B., Brempong, E. K., Agblorti, S. K. M. & Antwi Agyakwa, K. T. Assessment of the integrated coastal vulnerability index of Ghana toward future coastal infrastructure investment plans. Ocean Coast. Manag. 244, 106804 (2023).

Hastuti, A. W., Nagai, M. & Suniada, K. I. Coastal vulnerability assessment of bali province, indonesia using remote sensing and GIS approaches. Remote Sens. 14, 4409 (2022).

Loinenak, F. A., Hartoko, A. & Muskananfola, M. R. Mapping of coastal vulnerability using the coastal vulnerability index and geographic information system. Int. J. Technol. 6, 819–827 (2015).

Ariffin, E. H. et al. A multi-hazards coastal vulnerability index of the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 84, 103484 (2023).

Abuodha, P. A. & Woodroffe, C. D. Assessing vulnerability of coasts to climate change: a review of approaches and their application to the Australian coast. GIS Coast. Zo. A Sel. Pap. CoastGIS 2006, 458 (2006).

Mcinnes, K. L., Macadam, I., Hubbert, G. & O’Grady, J. An assessment of current and future vulnerability to coastal inundation due to sea-level extremes in Victoria, southeast Australia. Int. J. Climatol. 33, 33–47 (2013).

Dada, O. A., Almar, R. & Morand, P. Coastal vulnerability assessment of the West African coast to flooding and erosion. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–15 (2024).

Satta, A., Puddu, M., Venturini, S. & Giupponi, C. Assessment of coastal risks to climate change-related impacts at the regional scale: The case of the Mediterranean region. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 24, 284–296 (2017).

Mari, I., Peer, M., Cipak, A. & Koba, K. Environmental and sustainability indicators integrated coastal vulnerability index for coastal flooding: a case study of the Croatian coast. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 24, 100514 (2024).

Shaw, J., Taylor, R. B., Forbes, D. L., Ruz, M.-H. & Solomon, S. Sensitivity of the coasts of Canada to sea-level rise. Geol. Survey Canada 505, 1–79 (1998).

Dürr, H. H. et al. Worldwide typology of nearshore coastal systems: defining the estuarine filter of river inputs to the oceans. Estuaries and Coasts 34, 441–458 (2011).

Iturbide, M. et al. An update of IPCC climate reference regions for subcontinental analysis of climate model data: definition and aggregated datasets. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 2959–2970 (2020).

Athanasiou, P., Dongeren, A., Van, Pronk, M. & Giardino, A. Global Coastal Characteristics (GCC): a global dataset of geophysical, hydrodynamic, and socioeconomic coastal indicators. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 8200199, 3433–3452 (2024).

Hartmann, J. & Moosdorf, N. The new global lithological map database GLiM: A representation of rock properties at the Earth surface. Geochemistry, Geophys. Geosystems 13, 1–37 (2012).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3803 (2023).

Luijendijk, A. et al. The State of the World's Beaches. Sci. Rep. 8, 6641 (2018).

Mendoza, E. T. et al. Coastal flood vulnerability assessment, a satellite remote sensing and modeling approach. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 29, 100923 (2023).

Méndez, F. J., Menéndez, M., Luceño, A. & Losada, I. J. Estimation of the long-term variability of extreme significant wave height using a time-dependent Peak Over Threshold (POT) model. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean 111, 1–13 (2006).

Avornyo, S. Y. et al. A scoping review of coastal vulnerability, subsidence and sea level rise in Ghana: assessments, knowledge gaps and management implications. Quat. Sci. Adv. 12, 100108 (2023).

European Space Science Agency. Copernicus Digital Elevation Model (DEM). https://doi.org/10.5270/ESA-c5d3d65 (2021).

Muis, S. et al. Global Projections of Storm Surges Using High-Resolution CMIP6 Climate Models Earth’s Future. Earth’s Futur. 1–17 https://doi.org/10.1029/2023EF003479 (2023).

Nicholls, R. J. et al. A global analysis of subsidence, relative sea-level change and coastal flood exposure. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 634 (2021).

Hulskamp, R. et al. Global distribution and dynamics of muddy coasts. Nat. Commun. 14, 8259 (2023).

Furlan, E. et al. Development of a multi-dimensional coastal vulnerability index: assessing vulnerability to inundation scenarios in the Italian coast. Sci. Total Environ. 772, 144650 (2021).

Pendleton, B. E. A., Barras, J. A., Williams, S. J. & Twichell, D. C. Coastal Vulnerability Assessment of the Northern Gulf of Mexico to Sea-Level Rise and Coastal Change. https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2010/1146/ (2010).

Esri. World Countries Generalized. ArcGIS Hub. https://hub.arcgis.com/datasets/esri::world-countries-generalized/explore (accessed 10 November 2024).

Caldwell, R. L., Edmonds, D. A., Baumgardner, S., Paola, C. & Roy, S. A global delta dataset and the environmental variables that predict delta formation on marine coastlines. Earth Surf. Dyn. 7, 773–787 (2019).

Alder, J. Global Estuary Database. Catalogue PIGMA https://www.pigma.org/geonetwork/srv/api/records/5c17c6ac-866c-4747-b5b3-9d6287d5c738 (2003).

Acknowledgments

R.R. is partly supported by AXA Research Fund. R.A. was supported by the French ANR ASTRID program under the GLOBCOASTS project (ANR-22-ASTR-0013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.B. performed the calculations and wrote the first draft of the paper. The study was conceptualized by R.A., R.R., and T.M.D. V.B., T.M.D., and R.R. designed the computational workflow. All authors (V.B., T.M.D., R.R., R.A., and K.M.W.) contributed to refining the methodology, editing, and finalizing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Lars Rosendahl Appelquist and Daniela Pantusa for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Basnayake, V., Duong, T.M., Ranasinghe, R. et al. A global assessment of coastal vulnerability and dominant contributors. Nat Commun 17, 578 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67275-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67275-6