Abstract

Amorphous materials have garnered significant research interest because of their high structural tolerances and useful functionalities. Here, we develop an effective synthesis method for atomically thin, highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets that exhibit a promising electrocatalytic performance and a distinct pH-dependent operation mechanism. The poor orbital overlap and coordinatively unsaturated nature of the Ru ions in the highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets have a synergistic effect on the electrocatalytic performance by enhancing surface adsorption and the activation of lattice oxygen. The highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets exhibit high electrocatalytic activities in the oxygen evolution reactions (OERs) performed in both alkaline and acidic electrolytes. Various in situ spectroscopic investigations reveal that structural disordering causes a greater contribution of the lattice oxygen participation mechanism in acidic media than in alkaline media. This pH-dependent mechanism can be attributed to the amorphization-induced enhancement of lattice oxygen occupation in the acidic OER medium and increased hydroxide adsorption in the alkaline OER medium. Such disorder-driven pH tuning of the electrocatalytic operation mechanism enables the fabrication of pH-universal high-performance electrocatalysts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Highly disordered amorphous materials are attracting increasing research interest because of their good structural and electrochemical stabilities, along with their promising functionalities as electrodes and catalysts1,2. The absence of long-distance structural order in highly disordered materials provides a high level of structural flexibility to accommodate the crystal lattice frustration caused by catalytic and electrochemical processes3,4,5. As previously reported, the amorphization of metal oxide lattices frequently results in imperfect coordination between metal ions and oxide ions6,7. This lowered coordination number renders such highly disordered materials highly active as catalysts, since the amorphization-induced depression of orbital overlap inside the lattice endows the material with an extra capacity to form additional bonds with the adsorbed reactants8,9. Thus, the enrichment of surface active sites in highly disordered materials is crucial for optimizing their electrocatalytic performances10,11.

Two-dimensional (2D) nanosheets with atomic-level thicknesses are considered promising candidates for use in the exploration of amorphization-based high-performance electrocatalysts because of their high structural flexibility toward lattice disordering12,13. As reported previously by our group, the atomically thin 2D morphologies of exfoliated inorganic nanosheets allowed us to maximize the influence of amorphization on the catalyst activity owing to their large surface-to-volume ratios14. The calcination of monolayer metal oxide nanosheets under reducing conditions was expected to amorphize these materials via the loss of oxygen ions followed by a resulting rearrangement of the component ions in the crystal lattice. Notably, the degree of amorphicity can also be controlled by fine-tuning the calcination temperature and atmosphere. The controlled amorphization of inorganic nanosheets could therefore provide opportunities not only to explore high-activity electrocatalysts, but also to elucidate the influence of amorphicity on the pH dependence of the catalyst performance. Among the various inorganic nanosheets reported to date, monolayer RuO2 nanosheets have received significant research attention due to their promising functionalities as electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and as supercapacitor electrodes15,16,17. The single-crystalline nature of exfoliated RuO2 nanosheets renders them appropriate model compounds to elucidate the correlation between structural disorder and the improved catalyst functionality18. Furthermore, the presence of many coordinatively unsaturated surface sites and significant surface disordering in highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets is assumed to create a strong pH dependence with regard to the electrocatalyst functionality via an enhanced surface sensitivity. Thus, a systematic in situ investigation of the pH-dependent operation mechanism of highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets would provide a crucial basis for the development of universal pH-active electrocatalysts. At the time of this submission, despite the advantages of its amorphous nature, no studies have reported the synthesis of atomically thin amorphous nanosheets, and no systematic in situ investigation has been performed regarding the impact of structural disordering on the pH dependence of the electrocatalytic mechanism.

To address these gaps in the literature, the current study focuses on the fine-tuning of structural disorder as an efficient strategy to explore highly active electrocatalysts with pH-dependent operation mechanisms. The impact of structural disorder on the chemical bonding and morphology of atomically thin RuO2 nanosheets is investigated using spectroscopic and microscopic techniques as well as theoretical calculations to understand their high electrocatalytic activities in both alkaline and acidic electrolytes. Additionally, the distinct pH dependence of the electrocatalytic activity and the underlying mechanism for this dependence are elucidated systematically by in situ spectroscopy.

Results

Phase transition to highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets

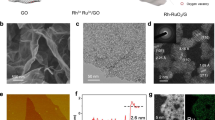

As precursors for the preparation of highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets, exfoliated RuO2 nanosheets were obtained by the intercalation of a protonated Na0.2RuO2 species with tetrabutylammonium (TBA+) cations16. The formation of atomically thin 2D layered RuO2 nanosheets was evidenced by atomic force microscopy (AFM), scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (Supplementary Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 1a, the crystal order of the layered RuO2 nanosheets was regulated in a controlled manner by subjecting the nanosheets to heat treatment at moderate temperatures of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 °C under an Ar atmosphere. The resulting materials were designated as aRu100, aRu200, aRu300, aRu400, and aRu500, respectively. Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Fig. 1b) confirmed amorphization during the reductive heat treatment process. While the layered RuO2 nanosheets and the aRu100 specimen each exhibited a (001) XRD peak corresponding to a layered RuO2 lattice16, the intensity of this peak significantly decreased for the aRu100, aRu200, and aRu300 samples (c.f., the RuO2 nanosheets), with a notable shift to higher angles being observed. Moreover, broad signals were detected in the XRD patterns of these samples, indicating structural disordering of the RuO2 lattice. Considering that the position and intensity of the (001) peak are strongly dependent on the layer-by-layer ordering of the RuO2 layer with interlayer water molecules, the observed high-angle shift and depression of this peak can be ascribed to the collapse of the intercalated RuO2 structure and the shrinkage of the interlayer distance due to the deintercalation of interlayer water molecules. Similar calcination-induced changes in the XRD patterns have been well documented for various layered metal oxides19,20,21. Upon increasing the calcination temperature further to 400 and 500 °C, rutile RuO2-related Bragg reflections became discernible in the XRD patterns of the aRu400 and aRu500 specimens22, indicating recrystallization of the rutile structure in these materials. Despite these thermally induced structural changes, the very thin 2D nanosheet morphology with a house-of-cards-type stacking structure remained essentially unchanged after heat treatment, as evidenced by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (Supplementary Fig. 2). Additionally, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements confirmed the retention of the atomically thin 2D nanosheet morphology after reductive thermal treatment (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 3). In contrast to the aRu100, aRu200, and aRu300 samples, the aRu400 and aRu500 samples exhibited surface holes, indicating that reductive heat treatment yielded vacant 2D nanosheets. The formation of atomically thin vacant nanosheets was confirmed using AFM. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 4, aRu500 exhibits surface holes and a markedly anisotropic 2D shape with a thickness of only ~0.7 nm. The formation of a highly disordered RuO2 lattice after calcination at 200 °C was further confirmed from the STEM images (Fig. 1d). Furthermore, a notable structural disorder was observed for the component ions in the aRu200 sample, as can be seen from Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 5. In contrast, distinct lattice fringes were observed for aRu500, indicating that calcination at 500 °C induced the crystallization of the rutile RuO2 structure (Fig. 1b).

Local atomic structure and chemical bonding in highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets

The impact of the reductive calcination process on the Ru valence state was subsequently verified using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). As shown in Fig. 2a, increasing the calcination temperature induced a continuous displacement of the Ru 3p peaks toward the low-energy side with respect to those of the layered RuO2 nanosheets, indicating that the Ru valence state continuously decreased because of the evaporation of lattice oxygen. As plotted in the O 1 s XPS data of Fig. 2b, among the present materials, the highly disordered aRu200 material showed the most intense shoulder peak in the higher energy region of ~531−532 eV, which was attributed to surface-adsorbed oxygen species23. Peak convolution analysis revealed that the area of this shoulder peak became smaller upon increasing the heating temperature to 500 °C due to the depression of structural disordering, as presented in Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 1. This suggests that structural disordering effectively promoted the surface adsorption of hydroxide species on the RuO2 nanosheets. Such enhanced surface adsorption could be attributed to the increased ability of the nanosheets to interact with the adsorbed hydroxide species owing to the amorphization-induced depression of the orbital overlap inside the oxide lattice. The increased local structural disorder around the Ru ions following reductive heat treatment was verified by O K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) measurements24. As displayed in Fig. 2c, all present aRu materials and rutile-structured bulk RuO2 materials exhibited two XANES features (A and B), which were related to the dipole-allowed transitions from the O 1s orbital to the O 2p orbitals that were hybridized with the Ru 4dt2g and Ru 4deg orbitals, respectively25. The energy difference between these peaks was reduced from ~3.1 eV for the bulk RuO2 to ~2.4 eV for aRu100, reflecting the depression of crystal field splitting for the 4 d orbitals. Thus, the observed peak splitting indicates a depression of the crystal field splitting (Δo) by ~29% owing to the disordering of the local structure in the RuO2 material (see Fig. 2c). As depicted in Fig. 2d, the poor orbital overlap in the highly disordered RuO2 lattice is responsible for a decrease in the splitting between the Ru 4dt2g and 4 deg orbitals. The observed depression of the peak splitting in the aRu200 material highlights the existence of thermally induced disorder in this material. Moreover, the Ru K-edge extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) data provided additional compelling support for the enhanced structural disorder following reductive heat treatment. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 7, despite the overall similarity in the oscillation features of the layered RuO2, aRu100, aRu200, and aRu300 species, calcination at 200−300 °C rendered the features beyond 8 Å−1 more diffuse and rather similar to those of the bulk RuO2, thereby reflecting the calcination-induced local structural modification. As shown in Fig. 2e, the layered RuO2 nanosheets and the aRu100 specimen exhibited typical layered RuO2-type EXAFS profiles with two Fourier-transform (FT) peaks related to the Ru−O and Ru−Ru coordination shells26, whereas significantly weaker FT peaks were observed for aRu200. Upon increasing the heat-treatment temperature, an increase in the FT peak intensity of the Ru−Ru shell was discernable at ~3.2 Å, reflecting a gradual transformation into rutile-type features27. As demonstrated in Fig. 2f, the Ru K-edge FT-EXAFS result strongly suggests that, despite the highly disordered structure of aRu200, this sample possesses a rutile RuO2-type local atomic arrangement including the first Ru−O coordination shell and the two Ru−Ru coordination shells up to 4 Å (Supplementary Table 2). In contrast to aRu200, the aRu500 specimen exhibits well-defined intense FT peaks assignable to the rutile RuO2 phase, confirming the restoration of its crystalline nature upon calcination at elevated temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 2). The reasonable quality of the EXAFS fitting results was further substantiated by the Fourier-filtered EXAFS results in the k-space, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. Moreover, the calcination-driven sequential structural modification, i.e., the layered RuO2 → highly disordered RuO2 → rutile RuO2 transformation, was further verified from the contour wavelet plots of the EXAFS oscillations (Fig. 2g–i). Additionally, heat-induced amorphization and phase transitions were confirmed using micro-Raman analysis (Fig. 2j). In contrast to the layered RuO2 nanosheet and the aRu100 specimen, which exhibit the typical phonon lines of a layered RuO2 phase28, only diffusive featureless spectra were observed for aRu200, aRu300, and aRu400, confirming the highly disordered structures of these materials. Additionally, aRu500 was found to exhibit distinct phonon lines corresponding to the rutile RuO2 phase29, consistent with the TEM images, XRD patterns, and first derivatives of the Ru K-edge XANES data (Supplementary Fig. 9). In contrast to the surface-sensitive XPS data, the impact of the structural disorder (accompanied by the removal of surface oxygen) on the Ru K-edge energy was less distinct in the bulk-sensitive XANES spectra. To further confirm the enhanced adsorption of hydroxides following the introduction of structural disorder, Ru K-edge EXAFS analyses were conducted on the aRu200 and bulk RuO2 materials before and after soaking in the alkaline electrolyte. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 10, the Ru K-edge EXAFS analysis reveals that the highly disordered aRu200 exhibits a notable enhancement in the FT peak related to the Ru−O bond after soaking in a 1 M KOH electrolyte. This indicates that an increase in the coordination number caused the effective adsorption of OH− ions. Conversely, the bulk RuO2 material exhibits only a negligible change in the intensity of the FT peak after soaking in the same electrolyte. This result provides additional convincing evidence for the amorphization-induced enhancement of OH− adsorption.

a Ru 3p XPS, b O 1s XPS, c O K-edge XANES, d schematic orbital diagram of RuO2, e Ru K-edge FT-EXAFS data, f EXAFS fitting data (The radial distance was not phase-corrected.), and j micro-Raman data of aRu materials, layered RuO2, and bulk RuO2. WT-EXAFS data of g layered RuO2, h aRu200, and i bulk RuO2.

OER electrocatalytic activity of the highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets

The role of structural disordering in enhancing the electrocatalytic activity of the RuO2 nanosheets for the OER was confirmed by performing linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) measurements in N2-saturated 1 M KOH and 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolytes at 1600 rpm using a scan rate of 10 mV s−1. As presented in Fig. 3a–d, the calcined RuO2 nanosheets exhibit significantly improved OER activities with lower overpotentials than those of the bulk RuO2 and layered RuO2 nanosheets in both alkaline and acidic media, highlighting the benefit of reductive heat treatment on the electrocatalytic performance of the RuO2 nanosheets. Compared to the commercialized Ir/C catalyst, which exhibited overpotentials (η) of 289 mV for 1 M KOH and 325 mV for 0.5 M H2SO4, the aRu200 nanosheets exhibited a better OER functionality with significantly lower overpotentials of 190 mV for 1 M KOH and 220 mV for 0.5 M H2SO4, thereby emphasizing the influence of amorphization in maximizing the electrocatalytic activity30. Upon increasing the heat-treatment temperature beyond 200 °C, the OER activity of the calcined RuO2 nanosheets decreased in both 1 M KOH and 0.5 M H2SO4 solutions, suggesting that the crystallization of a highly disordered structure had a detrimental effect on the electrocatalytic activity. Moreover, as presented in Supplementary Fig. 11, the aRu200 material displayed a higher electrochemically active surface area (ECSA), mass activity (MA), surface activity (SA), and turnover frequency (TOF) than the bulk RuO2, underscoring the significant advantage of structural disordering in improving the electrochemical activity and electrocatalytic performance of the RuO2 material31,32,33.

a, b LSV curves of OER, c, d overpotential data, e, f long term durability plot, and g, h EIS data of aRu materials, layered RuO2, and bulk RuO2. The inset in e provides an enlarged view to highlight the potential change in the early stage. The mass roading of catalyst ink is 0.2265 mg cm−2. All LSV curves were collected at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 with a rotating speed of 1600 rpm and measured at room temperature. No iR correction was conducted.

In addition, at a current density of 10 mA cm−2, the chronopotentiometric data revealed a significant improvement in the electrocatalyst durability for the RuO2 nanosheets upon amorphization. As shown in Fig. 3e, f, during the durability test, aRu200 exhibited only weak potential decays in acidic and alkaline electrolytes, respectively, indicating its robust electrocatalytic durability. Notably, the stability of aRu200 was slightly higher in the alkaline electrolyte than in the acidic electrolyte. Similar to aRu200, the other aRu materials exhibited robust durabilities at higher temperatures, giving results that were comparable or slightly inferior to that of aRu200 (see Supplementary Fig. 12). In stark contrast, the bulk RuO2 material suffered from severe activity fading within several hours after the measurement, highlighting the crucial role of amorphization in enhancing the electrocatalyst durability. The high OER activity of the aRu200 specimen was further validated by incorporating this material into polymer electrolyte membrane water electrolyzers (PEMWEs) and anion exchange membrane water electrolyzers (AEMWEs). Specifically, the aRu200-based PEMWEs and AEMWEs delivered better performances with smaller overpotentials than the corresponding electrolyzers based on the bulk RuO2, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 13. This further confirms the role of structural disorder in improving the catalytic performance of RuO2. The origin of the disorder-induced effects on the OER functionality of the RuO2 nanosheets was subsequently examined by performing electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements at 1.45 V. As depicted in Fig. 3g, h, the semicircle diameter of aRu200 was significantly smaller than that of the layered RuO2 nanosheets in the mid- and high-frequency regions, indicating an improved charge transfer efficiency in the former34. Curve-fitting based on equivalent circuits confirmed the decrease in the charge transfer resistance (Rct) upon amorphization, underscoring the benefit of amorphization on the charge transfer kinetics (Supplementary Table 3).

The role of structural disorder in improving the stability of the RuO2 nanosheets was also investigated by monitoring the XRD, Ru 3p XPS, Ru K-edge EXAFS, and TEM data obtained for the aRu200 material after stability testing to compare the catalyst phases, surface states, and structures. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 14, these analyses revealed that the stability test induced no significant changes, indicating that aRu200 retained its crystal phase, surface state, local structure, and crystal morphology after stability testing. This highlights the improved structural tolerance of the RuO2 material following amorphization.

Origin of the enhanced activity of the RuO2 nanosheets following amorphization

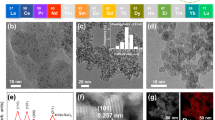

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to elucidate the origin of the significantly enhanced electrocatalytic activity of the highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets. Initially, disordered RuOx (x = 1.5, 1.7, and 2.0) models were generated using a robust melt-quench approach with ab initio molecular dynamics (aiMD) simulations, which have been successfully applied to model the amorphous forms of several systems (e.g., Si, SiO2, and other oxides such as IrO2)35,36. The simulation details are provided in the Methods section and in Supplementary Fig. 15. Furthermore, oxygen vacancies were introduced into the initial RuO2 structure to create oxygen-deficient disordered RuO2 systems. The structural properties of the bulk crystalline RuOx are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 16. It is evident that the disordered RuOx showed a good agreement with the experimental data. The partial radial distribution function, g(r), depicted in Fig. 4a–c reveals that no long-distance ordering exists beyond 4 Å in the highly disordered RuOx structures with various stoichiometries (denoted as aRuO2, aRuO1.75, and aRuO1.50), consistent with the disordered natures of the prepared samples (e.g., aRu200 and aRu300). Notably, significant amorphization-induced variations were observed for aRuO1.75 and aRuO1.50 with regard to their averaged Ru coordination numbers of 5.0 ± 0.83 and 4.2 ± 0.94 and their Ru–O bond lengths (highest peaks at 1.96 and 1.94 Å with widely broadened peaks, black solid lines in Fig. 4b, c). These values deviate from the single value of 6 for the Ru coordination number and 1.98 Å for the Ru–O bond length in the rutile-structured bulk RuO2. The decrease in the Ru–O bond length and the reduced coordination number for Ru in these theoretical amorphous structures are consistent with the experimentally characterized values of the Ru–O bond lengths and Ru coordination numbers, as summarized in Supplementary Table 4.

Partial radial distribution function, g(r), with the bulk amorphous a aRuO2, b aRuO1.75, and c aRuO1.50 structures, where the highest peak for the Ru–O, O–O, and Ru–Ru bond pairs is denoted by black, red, and blue dotted lines. d Stability of amorphous surfaces under oxygen-rich condition. e Top view of amorphous RuOx surfaces. Calculated Gibbs free energy diagrams of aRuO2.08 surface for f AEM and g LOM. In a, b, c, e, f, g, Ru, O, H atoms are denoted by violet, yellow, and white spheres, respectively. Darker RuOx polyhedra denote highly undercoordinated Ru atoms.

Subsequently, highly disordered RuOx surfaces derived from two bulk phases, namely aRuO1.75 and aRuO1.50, were generated by randomly selecting ensemble structures from the MD trajectories equilibrated at 300 K and varying the cleaving planes from the amorphous bulk structures. The local oxygen ion environment around the outermost Ru ions was maintained on both cleaved facets, resulting in 30 amorphous surface configurations. To evaluate the stabilities of these surface forms of disordered RuOx, the Gibbs free energy changes (ΔG; Supplementary Fig. 17) were computed under oxygen-rich conditions (with the oxygen chemical potential set by the O2 molecule as the oxidation limit), as illustrated in Fig. 4d. Qualitatively consistent with the experimental observations indicating the enhanced adsorption of oxygen species onto the RuO2 nanosheets following surface amorphization, the obtained disordered surfaces bearing additional oxygen adsorbates exhibited increased stabilities under oxidative conditions. Figure 4e illustrates the thermodynamically favorable disordered surfaces, namely the aRuO1.81 and aRuO2.08 surfaces (derived from aRuO1.75 and aRuO1.50), under oxygen-rich conditions (red arrows in Fig. 4d). As indicated, the coordination numbers of the Ru ions in these slab models were 4.8 ± 0.84 and 4.1 ± 0.90, respectively, where the darker RuOx polyhedra indicate the presence of highly undercoordinated Ru atoms (coordination number <4).

Energetic analyses of the lattice oxygen participation mechanism (LOM) and the adsorbate evolution mechanism (AEM) were subsequently conducted using DFT calculations to elucidate the enhanced OER activities of the amorphous RuOx surfaces. The ΔG values for the elementary steps of the AEM and LOM occurring on the thermodynamically favorable amorphous surfaces (Fig. 4f, g) were calculated using the computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) method37. Owing to the lack of long-range periodicity, the Ru site dependency of ΔG was considered (Supplementary Fig. 18) and the reaction pathways with the lowest theoretical OER overpotentials (η) were selected (Fig. 4f, g). The calculated ηLOM value for the aRuO2.08 surface was 1.51 V, which was notably lower than those obtained for rutile-structured bulk RuO2 (i.e., 1.99 and 1.86 V for the (110) and (211) surfaces, respectively), suggesting that local disorder could lower the LOM barrier relative to crystalline facets38. As previously reported, the rate-determining step in the LOM of the rutile-structured RuO2 involves activation of the lattice oxygen species through the creation of oxygen vacancies, followed by reaction with a free molecule of H2O38. In the LOM on the highly disordered RuO2.08 surface, the activation of the Ru–O bond involved significant structural rearrangement of the RuO4 polyhedron with H* and its connectivity with the neighboring RuOx polyhedra (the “H* + O2” step shown in Fig. 4g), alongside the creation of an oxygen vacancy. This ~0.5 V reduction in ηLOM relative to that of the crystalline counterpart confirms that the promotion of the LOM process by the disordered RuOx surfaces depends on the nature of the electrolyte. In contrast, the ηAEM value for the aRuO2.08 surface (0.77 V) was comparable to those obtained for the (110) and (211) rutile-structured RuO2 surfaces (0.56 and 0.98 V, respectively)38. However, significant Ru site-dependence was observed for the ΔG values of both the AEM and the LOM in the aRuO2.08 surface, with variations of ±0.5 V, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 18. Such marked changes of ΔG depending on the Ru site could be responsible for the local disorder-induced improvement in the OER activity through both mechanisms. We note that our DFT/CHE models neglect explicit electrolyte and sample only a limited set of amorphous surface configurations. Accordingly, the computed energetics are used to rationalize qualitative trends observed experimentally rather than to provide quantitative predictions.

Origin of the pH-dependent OER activity of the highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets

To obtain an in-depth understanding of the pH-dependent mechanism underlying the disorder-induced enhanced OER activity of the RuO2 nanosheets, in situ differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) analyses were performed for the aRu200 and bulk RuO2 specimens under varying potentials in acidic 0.5 M H2SO4 and alkaline 1 M KOH electrolytes prepared using O18-labeled water, see Fig. 5a–d. As shown in Fig. 5a, b, the ratio between the evolved 34O2 and 36O2 gases was notably greater for the acidic electrolyte than for the alkaline electrolyte. From Fig. 5e, it can be seen that the LOM process yielded 34O2 gas upon the combination of one 16O atom from the RuO2 lattice and one 18O atom from the isotope water, whereas the AEM process produced 36O2 gas via the combination of two 18O atoms from isotope water39. In this regard, the higher 34O2/36O2 gas ratio observed in the 0.5 M H2SO4 solution (c.f., the 1 M KOH solution) provides convincing evidence for the enhanced contribution of the LOM upon the lowering of the electrolyte pH. Furthermore, such an enhancement of the 34O2/36O2 gas ratio in the 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte was not observed for the bulk RuO2 (Fig. 5c), confirming the disorder-driven increase in the LOM contribution in the acidic electrolyte. The observation of similar 34O2/36O2 gas ratios for the bulk RuO2 in both the 0.5 M H2SO4 and 1 M KOH electrolytes confirms that bulk RuO2 shows minimal mechanistic change across pH.

To further investigate the pH dependence of the operation mechanism, in situ XANES/EXAFS analyses were carried out for aRu200 and the bulk RuO2 under varying potentials (i.e., at the open-circuit voltage (OCV) and at 1.40, 1.45, 1.50, and 1.60 V) in the same acidic and alkaline electrolytes. As shown in Fig. 6a–h, the application of an oxidative potential to aRu200 led to quite distinct shifts in features A and B toward higher-energy sides in the alkaline electrolyte condition. These features corresponded to the rising edge and the dipole-allowed 1 s → 5p transition, respectively, thereby indicating an increased Ru valence state during the OER40. To perform a detailed investigation of the spectral changes induced by the evolution of O2, the differential Ru K-edge data were inspected with regard to the plots of the differences in the normalized intensity (ΔI = INth − I1st) and the intensity difference of feature A during the OER (Fig. 6g, h). With an increasing oxidative potential, aRu200 experienced a continuous decrease in the intensity of feature A, related to a decrease in ΔI and indicating the displacement of the edge position toward the high-energy side. This variation confirmed an increase in the Ru valence state of aRu200 during the OER in the alkaline electrolyte41. Since the adsorption of hydroxide ions during the intermediate step of the OER process depletes the electron density of RuO242, the marked increase in the Ru valence state of aRu200 observed during the OER could be considered strong evidence for effective hydroxide accumulation in the highly disordered RuO2. This originates from the enhanced capability of the amorphous material to interact with the adsorbed reactants. On the other hand, the potential-induced spectral changes appeared weaker in the 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte than in 1 M KOH, which could be attributed to a significantly lower hydroxide ion concentration in the acidic electrolyte. In comparison with highly disordered aRu200, the variation of the XANES features of bulk RuO2 during the OER was less prominent, reflecting milder modification of its electronic structure (Supplementary Fig. 19). In addition, the potential-induced variation in the edge energy was further inspected by monitoring the shifts of the maximum peaks observed in the first derivatives of the XANES spectra. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 20, the highly disordered aRu200 exhibited a distinct shift in the maximum peak (i.e., the edge energy) toward the high-energy region during the OER in the alkaline electrolyte, which was greater than the peak shift observed for the bulk RuO2. This result confirms the higher OER activity and greater modification of the electronic structure of the highly ordered aRu200. In contrast, despite the higher OER activity of aRu200 than bulk RuO2, only a weak shift of the maximum peak in the first derivatives occurred in the acidic electrolytes for highly disordered aRu200 as well as for bulk RuO2. Considering that the AEM pathway relies strongly on the adsorption of hydroxide ions and induces a greater increase in the Ru oxidation state than the LOM pathway (Supplementary Fig. 21)43, the weak edge shift observed for aRu200 in the acidic electrolyte can be attributed to the reduced contribution of the AEM pathway and the increased contribution of LOM pathway under low pH conditions. This is consistent with the H2O18-labeled DEMS results obtained for aRu200, which showed a decreased contribution of the AEM and an increased contribution of the LOM in the acidic electrolyte (Fig. 5a). These in situ XANES results emphasize the pivotal role of amorphization and vacancies in enhancing the surface adsorption of hydroxide ions in alkaline media and increasing contribution from the LOM to the OER activity in acidic media.

a, b 3D contour plots for in situ Ru K-edge XANES data, c, d 2D contour plots of edge regions, e, f difference (ΔI = INth – I1st) in normalized intensity and g, h ΔI for the peak (A) of in situ Ru K-edge XANES data in 0.5 M H2SO4 and 1 M KOH electrolytes. In situ FT-EXAFS data and overlapped data of aRu200 in i, j 0.5 M H2SO4 and k, l 1 M KOH electrolytes. The insets in j, l provide enlarged views to highlight the change of the first FT peak intensity and position upon the application of electrical potential. In situ Raman data of m aRu200 and n bulk RuO2 in 1 M KOH and o aRu200 and p bulk RuO2 in 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolytes. The inset in m provides an enlarged view to highlight the shift of the Raman peak at 400–600 cm−1 upon the application of electrical potential. The arrows in i, j, k, l, m are guides to highlight the shift of peaks.

As per the Ru K-edge EXAFS analysis, a notable shift of this FT peak toward a longer distance was observed during the OER performed in the acidic electrolyte, indicating the elongation of the Ru−O bond (see Fig. 6i, j and Supplementary Table 5). In contrast to the AEM, which experiences the additional formation of Ru−OOH bonds with the adsorbed hydroxide ions, the LOM involves the replacement of the shorter lattice Ru−O bonds with longer Ru−OO (i.e., OO*) bonds44, thereby accounting for the observed increase in the average Ru−O bond distance. In addition to the peak shift, a close comparison of the FT-EXAFS data measured for aRu200 in the acidic electrolyte at both the OCV and at 1.6 V revealed a slight depression of the Ru–O-related FT peak intensity upon the application of an oxidation potential (see Fig. 6j). This potential-induced lowering of the peak intensity demonstrated a decrease in the coordination number during the OER process in an acidic medium, as confirmed by the EXAFS fitting analysis (Supplementary Fig. 22 and Supplementary Table 5). Such a decrease in the coordination number with a larger distance provided compelling evidence for the increasing contribution of the LOM in the acidic electrolyte, since this process involved the cleavage of metal−oxygen bonds and a corresponding reduction in the coordination number45. Conversely, as presented in Fig. 6k, l, during the OER performed in an alkaline medium, the FT peak corresponding to the Ru−O bond in aRu200 was displaced toward the shorter-distance side with an increasing oxidative potential. This result indicated the shortening of the Ru−O bond, which was further corroborated by fitting analysis (Supplementary Table 5), thereby supporting the dominant contribution of the AEM mechanism in the alkaline electrolyte. Specifically, this involves the additional adsorption of hydroxide ions, which results in an increased Ru oxidation state, as evidenced by the XANES results. This EXAFS analysis clearly demonstrates the greater contribution of the LOM in the acidic electrolyte (c.f., in the alkaline electrolyte) when considering the OER functionality of the highly disordered aRu200. In contrast to aRu200, the EXAFS spectrum recorded for the bulk RuO2 changed negligibly during the OERs performed in acidic and alkaline media (Supplementary Fig. 22 and Supplementary Table 5). This can be ascribed to the weak OER activity of the layered RuO2 nanosheets. Overall, the in situ XANES/EXAFS results suggest that aRu200 exhibits a distinct pH-dependent OER activity, i.e., an increasing contribution of the LOM upon reducing the solution pH. This could be attributed to a reduction in the Ru−O bond strength through structural disordering, which facilitated the participation of lattice oxygen species in the OER (Supplementary Fig. 21). In the alkaline electrolyte, the AEM is dominant during the OER because of the high concentration of hydroxide ions. Thus, the disorder-induced enhancement in the adsorption capability of aRu200 in the presence of hydroxide species was responsible for the increased contribution of the AEM under alkaline conditions with respect to the bulk RuO2. As presented in Supplementary Fig. 23, in contrast to the aRu200 and bulk RuO2 specimens, the layered RuO2 nanosheets showed a significantly more severe depression of the FT peaks during the OER process in both acidic and alkaline electrolytes, highlighting the relatively weak structural stability of this material.

The pH-dependent operating mechanism of the highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets was further substantiated by in situ Raman analysis. As shown in Fig. 6m, aRu200 exhibits broad phonon lines related to the Ru−O vibration modes at 400–600 cm−1 in the 1 M KOH solution22,46, demonstrating the retention of a highly disordered structure in the alkaline electrolyte. An increase in the oxidative potential slightly displaces the phonon lines corresponding to the stretching mode of the Ru−O vibration toward higher wavenumbers, indicating an increase in the Ru−O bond energy47. This is consistent with the Ru K-edge XANES/EXAFS results. Such a distinct variation in the Ru−O vibrational energy could be regarded as evidence of the additional creation of Ru−OH bonds and a subsequent increase in the Ru oxidation state during the OER performed in an alkaline electrolyte. This observation offers further convincing proof of the increased contribution of the AEM to the OER activity of highly disordered aRu200 in an alkaline medium. Moreover, since CO2 can dissolve in the alkaline electrolyte to form CO32− an additional Raman peak assigned to the CO32− species appeared at ~1065 cm−1 40. As shown in Fig. 6m, the intensity of this carbonate peak increased for aRu200 upon increasing the oxidative potential, which could be ascribed to the surface adsorption of hydroxide ions on the highly disordered material. Such spectral variations were less prominent for the bulk RuO2 during the OER (Fig. 6n), consistent with its lower OER activity compared to that of aRu200. In situ Raman analysis also provided compelling evidence for the increased contribution of the AEM to the improved OER activity of the highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets in the alkaline medium. Furthermore, in the acidic medium, an increasing oxidation potential led to the enhancement of RuOOH-related peaks at 850−950 cm−1 for the aRu200 system (Fig. 6o)22,46. Even at a low potential of 1.4 V (i.e., during the very early stages of the OER), this oxygen intermediate (e.g., HOO*)-related peak was discernible for aRu200, which is in stark contrast to the results obtained for the bulk RuO2 (Fig. 6p). As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 21, the LOM process was initiated by the formation of Ru−OOH (e.g., HOO*) bonds, in contrast to the AEM process, which involved the formation of HOO* species in the final step. Additionally, in contrast to the LOM pathway, wherein the Ru−OOH bonds are formed by the attachment of hydroxide to the lattice Ru−O bond, the formation of Ru−OOH bonds in the AEM process relies on the successive adsorption of two hydroxide ions on the RuO2 surface. Thus, the Ru−OOH bonds formed during the AEM process were too labile to be detected, thereby accounting for the absence of RuOOH-related Raman peaks in the bulk RuO2. Thus, the observation of this RuOOH-related peak throughout all stages of the OER (i.e., 1.4−1.6 V) could be regarded as convincing evidence for a disorder-induced increase in the LOM contribution to the enhanced OER activity. Alternatively, it was reported that the Raman peak originating from the deprotonated Ni−OO (i.e., OO*) species was discernible at 900−1000 cm−1 48. Consequently, a Raman peak originating from the Ru−OO species was expected to appear below 900 cm−1 since the stronger Ru4+−OO bond (c.f., the Ni2+−OO bond) should lead to lowering of the O−O* vibration energy in the Ru4+−OO species (with respect to the Ni2+−OO species) due to the bond competition effect. Thus, the vibration mode originating from the OO* species in the RuO2 electrocatalyst also contributed to the observation of a Raman peak at 850–950 cm−1 during the OER process of aRu200. Since this OO* species was formed only in the LOM pathway, its presence for only the aRu200 specimen and its absence from the bulk RuO2 system could be interpreted as compelling evidence for the increased contribution of the LOM pathway to structural disordering. The formation of oxygen intermediate species for the OER performed over aRu200 in the acidic electrolyte was further corroborated by in situ Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. As presented in Supplementary Fig. 24, the aRu200 system exhibited a clear peak at ~1050 cm−1 originating from the *OOH species after the application of an electrical potential49,50, which was not discernible at the OCV. This result provides further proof of the generation of RuOOH species during the OER, thereby supporting the increasing contribution of the LOM in the acidic electrolyte. This *OOH-related peak was not discernible for the bulk RuO2, either at the OCV or at 1.6 V, ultimately confirming the disorder-induced enhancement of the LOM contribution in the acidic electrolyte.

To further confirm the increased contribution of the LOM under acidic conditions, the effects of tetramethylammonium (TMA) ions on the OER activities of the aRu200 and bulk RuO2 specimens were also investigated in the 0.5 M H2SO4 and 1.0 M KOH electrolytes. TMA was selected due to its ability to act as a quencher for *OO species, i.e., a characteristic intermediate in the LOM pathway (see Supplementary Fig. 21)51,52. Thus, the variation in the OER activity upon the addition of TMA can be an effective indicator of the contribution of the LOM to the OER performance. It was found that the addition of TMA led to a marked degradation in the OER activity of the highly disordered aRu200 under acidic conditions (Supplementary Fig. 25). This is in stark contrast to the bulk RuO2, which exhibited a much weaker TMA-induced depression of its OER performance. This result provides additional convincing support for the significant contribution of the LOM pathway to the OER activity of aRu200 under acidic conditions. Conversely, negligible effect of TMA addition on the alkaline OER activity was commonly observed for aRu200 and bulk RuO2, indicating no significant contribution of LOM process to the alkaline OER activity of both materials.

Considering that the AEM pathway is known to be more advantageous than the LOM pathway for improving the stability of an OER catalyst, the higher stability of aRu200 in the alkaline electrolyte than in the acidic electrolyte could be interpreted as a greater contribution of the AEM process in the alkaline solution. Notably, even in an acidic solution, the aRu200 material delivered a good durability for up to 100 h, emphasizing the merit of a highly disordered structure. Indeed, the high structural flexibility of the amorphous lattice helped relieve the destabilization effect caused by oxygen loss in the LOM pathway. This was achieved via rearrangement of the local oxygen sublattice around the Ru ions, thereby preventing a significant loss of lattice enthalpy.

Theoretical surface Pourbaix diagrams were subsequently obtained to provide further support for the above experimental findings by illustrating how the stabilities of the surface adsorbates change depending on the pH and the applied (oxidation) potential. In these diagrams (Supplementary Fig. 26), two surfaces of the highly disordered RuOx were considered, each of which was identified as having the lowest theoretical overpotential for either the AEM or the LOM (Fig. 4f, g). The relevant adsorbates (i.e., O*, HOO*, H*, and HO*) of these surfaces were also considered. Under alkaline conditions (pH = 14), the theoretical results (left panel, Supplementary Fig. 26) show the enhanced stability of HO* for the AEM compared to the LOM, indicating stronger hydroxide adsorption, consistent with the XANES and EXAFS observations. In contrast, under acidic conditions (pH = 1), the surfaces bearing lattice oxygen vacancies (i.e., H*, see Fig. 4g for the surface geometries) exhibited a broader stability range for the LOM than for the AEM (right panel, Supplementary Fig. 26). The theoretical observation that reduced Ru species bearing lattice oxygen vacancies exhibit an increased stability during the LOM process aligns with the reduced Ru coordination number detected by EXAFS under acidic OER conditions. Overall, the considerable agreement between the spectroscopic findings and these theoretical surface adsorbate stability predictions demonstrate that the hydroxide-driven AEM dominated under alkaline conditions, whereas the LOM (with the formation of lattice oxygen vacancies) governed the OER process under acidic conditions, thereby enabling a highly efficient OER across a wide pH range.

Discussion

In summary, a thermally driven amorphization route was developed for the preparation of atomically thin, highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets that exhibited a good electrocatalytic OER activity and a distinct pH-dependent operation mechanism. Significant disordering of the crystal lattice effectively increased the OER activity and durability of the RuO2 nanosheets via enhanced surface adsorption and the activation of lattice oxygen atoms to create oxygen vacancies in an agreement with DFT calculations. Various in situ spectroscopic investigations revealed that the highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets exhibited a pH-dependent tuning of their OER mechanism. Specifically, the contributions of the LOM and AEM processes to the OER activity were found to vary significantly with respect to the change in the electrolyte pH. In an acidic electrolyte, the reduction in the lattice energy caused by amorphization facilitated the occupation of lattice oxygen sites of the highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets (i.e., an increasing contribution of the LOM). In contrast, the high concentration of hydroxide ions in the alkaline electrolyte rendered the AEM dominant during the OER. This was attributed to the fact that amorphization decreases the orbital overlap inside the lattice and enhances the ability to interact with the adsorbed species. The enhanced surface adsorption of hydroxide ions therefore enhanced the OER activity of the highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets, with an increasing contribution from the AEM. The amorphization strategy presented herein can therefore be applied for the development of a useful synthetic route toward highly efficient transition metal oxide-based electrocatalysts that are active over a wide pH range. Currently, our group is developing soft chemical amorphization routes that are applicable to other types of monolayer inorganic nanosheets, including metal chalcogenides, metal hydroxides, and metal pnictogenides, to explore economically feasible and efficient electrocatalysts with a high degree of structural disorder.

Methods

Materials

Ruthenium (IV) oxide (RuO2, anhydrous, 99.9%), ruthenium powder (Ru, −200 mesh, 99.9%), tetrabutylammonium hydroxide solution (TBA·OH, 40 wt% in H2O), and sodium persulfate (Na2S2O8, 98%) were purchased from Merck. Sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, anhydrous, 99%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, 35.0–37%), sulfuric acid (95%), 2-propanol (99.5%), and potassium hydroxide (KOH, 95%) were obtained from SAMCHUN chemicals. 20% Ir on Vulcan XC-72 was purchased from Premetek. Nafion (5 wt%) and fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) glass were obtained from Omniscience. Carbon paper (TGP-H-60) was purchased from thermoscientific. Platinum wire and saturated calomel electrode (SCE) were purchased from ALS. H2O18(98%) water was purchased from China Isotope Company.

Material preparation

The precursor material for the synthesis of exfoliated RuO2 nanosheets was synthesized as follows: first NaRuO2 was prepared by mixing Na2CO3, Ru, and RuO2 in a molar ratio of 2:1:3, followed by heating at 900 °C for 12 h under an Ar atmosphere. The resulting powder was then reacted with 1 M Na2S2O8 for 3 days (100 mL per 1 g), washed with distilled water, and oven-dried. The obtained powder was reacted with 1 M HCl for another 3 days (100 mL per 1 g), with a daily replacement of the acidic solution. Afterward, the powder was thoroughly washed with distilled water and oven dried. The resulting powder was dispersed in distilled water containing TBA·OH solution and stirred for 10 days (250 mL distilled water and 1 mL 40 wt% TBA·OH per 1 g powder). The obtained colloid was centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min to remove unexfoliated precipitates16. Owing to the negative surface charges of the exfoliated RuO240, the obtained colloidal suspension of RuO2 nanosheets was restored through protonation using a 37% concentrated HCl solution as the H+ source. The obtained precipitate was washed with distilled water and freeze-dried. To synthesize the aRu materials, the proton-assembled H−RuO2 nanosheets were heat-treated under an Ar atmosphere in a tube furnace at temperatures of 100–500 °C for 3 h (heating rate: 2 °C/min).

Material characterization

Powder XRD was performed for the synthesized materials using a Rigaku MiniFlex instrument (Ni-filtered Cu-Kα radiation) at room temperature. AFM images were recorded for the layered RuO2 nanosheets using a Park System NS-10 instrument. The crystal shapes and atomic arrangements of the aRu materials and layered RuO2 nanosheets were characterized by electron microscopy (JEOL JEM-F200, JSM-7001F, and JEM-ARM200F). The O K-edge XANES and Ru K-edge XANES/EXAFS measurements were conducted at beamlines 10A2 and 10C in the Pohang Light Source under top-up operations at 3 GeV and 300 mA. While all spectra were obtained in transmission mode, the in situ measurements were conducted in fluorescence mode. To ensure spectral reliability, care was taken to evaluate the stability of the energy scale by monitoring the spectrum of the Ru metal foil for each measurement; thus, the edge positions were reproducible to <0.05 eV. The in situ XANES/EXAFS spectra were recorded in the fluorescence mode using an in situ cell (prepared in-house), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 27. The catalyst material was deposited on FTO glass (1 × 2 cm2) to prepare the working electrode, which was placed in the in situ cell filled with the desired electrolyte (1 M KOH or 0.5 M H2SO4). A Pt wire and a SCE were used as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively. Data processing for the XANES and EXAFS measurements was performed using Athena software. The XPS measurements were carried out using a Thermo VG spectrometer (monochromatized Al-Kα X-ray source, operated at 12 keV and 3 mA). The XPS energy calculations were performed based on the adventitious C 1 s peak at 284.8 eV. Micro-Raman analysis was conducted using a Horiba Jobin Yvon LabRam Aramis spectrometer (Ar-ion laser, λ = 514.5 nm). In situ Raman experiments were performed using an Au nanoparticle-based substrate for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. The in situ FTIR experiments were conducted using a JASCO FT/IR-4600 instrument. In situ DEMS data were recorded to analyze evolved gases during the HER process using a custom design cell, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 28.

Electrocatalytic activity tests

The electrocatalytic activity was measured using a three-electrode system. To prepare the composite catalyst, the active material (8 mg), Vulcan XC-72 (2 mg), and Nafion® solution (5 wt%, 40 μL) were mixed in a Milli-Q water/isopropanol (5 mL, 4:1 (v/v)), followed by sonication for 1 h to form the catalyst ink. The catalyst ink (10 μL drop) was deposited on a glassy carbon (GC) electrode (3 mm, ALS Co.), then oven-dried. The catalyst loading was 0.2265 mg cm−2. The resulting catalyst-coated GC electrode, an SCE, and a Pt metal wire were used as the working, reference, and counter electrodes, respectively. The EIS data were collected over a frequency range of 100 kHz–0.1 Hz with an amplitude of 10 mV applied to the 1.45 V (V vs RHE). All electrochemical data were measured using an IVIUM analyzer and an RRDE-3A rotator. Prior to performing the electrochemical measurements, the electrolyte solution was purged with nitrogen gas for 30 min, and a nitrogen flow was maintained throughout the experiment to ensure an oxygen-free environment. LSV was conducted in both acidic and basic electrolytes. For the acidic conditions, a 0.5 M H2SO4 (2.81 mL of 95% H2SO4 solution was dispersed in 97.19 mL of Milli-Q water, pH = 0.28 ± 0.05) solution was used, while for the basic conditions, a 1 M KOH solution (59.06 g KOH in 100 mL of Milli-Q water, pH = 13.79 ± 0.05) was employed. The electrolyte was freshly prepared before each measurement. The measurements were performed in a glass cell (ALS Co., 120 mL) with an electrolyte volume of 60 mL. The LSV measurements were performed at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 and a rotating speed of 1600 rpm. The potential was scanned from 0.2 to 0.6 V (V vs SCE) in the case of 1 M KOH electrolyte, and from 1.1 to 1.5 V (V vs SCE) for the 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte. The electrochemical measurements were performed. No iR correction was conducted. The chronopotentiometry test was evaluated using carbon paper (1 cm2, 0.2265 mg cm−2) substrate. In H2-saturated 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte, calibration was conducted utilizing a Pt mesh as the working electrode and counter electrode, a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference electrode. LSV measurement was performed at a scan rate of 2 mV s−1 (Supplementary Fig. 29). The calibration potential was determined by averaging the potential, at which the current density approached to zero, corresponding to the onset of the HER. All reported potentials were subsequently referenced to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) scale, calculated as: E (V vs RHE) = E (V vs SCE) + 0.059 × pH. The electrochemical measurements were performed at least three times for each catalyst.

Preparation of the membrane-electrode assembly and PEMWE/AEMWE tests

Membrane electrode assemblies (MEAs) were prepared to evaluate the single-cell performances and durabilities of the fabricated catalysts. Nafion® 212 (DuPont, USA) and PiperION-60® (Versogen, USA) were used as the PEM and AEM, respectively. Both membranes were treated before use according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All catalyst layers were fabricated using the catalyst coated substrate method by spraying the catalyst slurry onto a porous transport layer (PTL). 2GDL8N-035 (Bekaert, Belgium) and 20FP3 (Bekaert, Belgium) were used as the anode PTLs for the PEMWEs and the AEMWEs, respectively. JNT40-A3 (JNTG Co., Korea) was used as the PTL cathode in both systems. A catalyst slurry was prepared by mixing the catalyst, the ionomer, 2-propanol, and deionized (DI) water. The anode and cathode catalyst loadings were 1.0 and 0.4 mg cm−2, respectively, while the ionomer contents were 60 and 30 wt.% for the anode and the cathode, respectively. The anode and cathode membranes were assembled at a torque of 70 kgfcm to prepare the MEA. The active area was 5 cm2. The single-cell performances were evaluated using single-cell tests. The cell temperatures were maintained at 80 and 70 °C for the PEMWEs and AEMWEs, respectively. Preheated distilled water and 1 M KOH were supplied to the anodes and cathodes of the PEMWEs and AEMWEs as reactants at flow rates of 5 mL min−1. The polarization curves were recorded using the voltage sweep method over a range of 1.35–2.15 V at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1. The performance was measured using a potentiostat (Zahner-Elektrik GmbH & Co. KG, Germany).

DFT calculations

The Vienna ab initio Simulation Package53,54,55 was used to perform the DFT calculations with the revised Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functional and Grimme’s D3-dispersion correction56,57,58. A plane-wave-basis kinetic energy cutoff of 400 eV was employed. The aiMD simulations were performed under constant pressure conditions (NPT ensemble) using the Langevin thermostat, with a friction coefficient of 10 ps−1 to control the temperature fluctuations and a time step of 1 fs59,60. To model the amorphous phases of the bulk Ru oxides with varying stoichiometries, 192-atom p(2 × 4 × 2) supercells of rutile were utilized, wherein oxygen vacancies were randomly introduced to set the O/Ru stoichiometries to 1.75 and 1.50 in the starting structures. The Brillouin zone was folded to the Γ-point for these supercell structures. The initial structures were randomized at 3000 K for 10 ps to mimic the melting process, followed by quenching from 3000 to 100 K over 5 ps at a cooling rate of 580 K/ps. The quenched structures were equilibrated at 300 K for 10 ps. The amorphous RuOx surfaces were derived from two bulk phases, namely aRuO1.75 and aRuO1.50, by randomly selecting ensemble structures from the MD trajectories equilibrated at 300 K and varying the cleaving planes from the amorphous bulk structures. The local oxygen atom environments around the outermost Ru atoms on both cleaved facets were maintained, resulting in 30 amorphous surface configurations. The vacuum region was adjusted to ~15 Å to minimize the interaction between periodic images. The CHE approach37 was employed to assess the OER overpotentials for the LOM and AEM, and also to assess the relative stabilities of the amorphous surface as a function of the pH and the electrode potential (versus SHE)61. The Gibbs free energy calculations for the OER process were conducted considering the zero-point energy and vibrational entropy corrections, as reported previously38. A gamma point sampling of the Brillouin zone was used to optimize the gaseous H2 and H2O molecules within a box having dimensions of 15 × 15 × 15 Å. The site dependencies of the surface adsorbates (HO*, O*, HOO*, and H*O-site) were also considered.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. The DFT datasets generated in this study are deposited in Zenodo repository and is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17241077. The repository includes DFT-optimized structures and ab initio molecular dynamics (aiMD) trajectories, including RuOx bulk MD trajectories, amorphous surface models, and adsorbate-covered optimized surfaces. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Wan, C. et al. Amorphous nickel hydroxide shell tailors local chemical environment on platinum surface for alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Mater. 22, 1022–1029 (2023).

Li, R. et al. Amorphization-induced surface electronic states modulation of cobaltous oxide nanosheets for lithium-sulfur batteries. Nat. Commun. 12, 3102 (2021).

Guo, T., Hu, P., Li, L., Wang, Z. & Guo, L. Amorphous materials emerging as prospective electrodes for electrochemical energy storage and conversion. Chem. 9, 1080–1093 (2023).

Kang, J. et al. Recent progress of amorphous nanomaterials. Chem. Rev. 123, 8859–8941 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Sodium-decorated amorphous/crystalline RuO2 with rich oxygen vacancies: a robust pH-universal oxygen evolution electrocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 18821–18829 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Determining the three-dimensional atomic structure of an amorphous solid. Nature 592, 60–64 (2021).

Strand, J. & Shluger, A. L. On the structure of oxygen deficient amorphous oxide films. Adv. Sci. 11, 2306243 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Lattice-strain engineering of homogeneous NiS0.5Se0.5 core-shell nanostructure as a highly efficient and robust electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Adv. Mater. 32, 2000231 (2020).

Jin, X. et al. Synergistic control of structural disorder and surface bonding nature to optimize the functionality of manganese oxide as an electrocatalyst and a cathode for Li–O2 batteries. Small 16, 1903265 (2020).

Zhang, B. et al. A strongly coupled Ru-CrOx cluster-cluster heterostructure for efficient alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis. Nat. Catal. 7, 441–451 (2024).

Ahn, S. H., Jin, D., Lee, C. & Lee, Y. Oxygen-vacancy rich IrxMo1−xOy nanofibers for oxygen evolution reaction: Excellent pH-universal and electrolyte-concentration-independent catalytic activity. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 14941–1495 (2023).

Jin, X., Gu, T.-H., Kwon, N. H. & Hwang, S.-J. Synergetic advantages of atomically coupled 2D inorganic and graphene nanosheets as versatile building blocks for diverse functional nanohybrids. Adv. Mater. 33, 2005922 (2021).

Yang, L. et al. Vertical growth of 2D amorphous FePO4 nanosheet on Ni foam: outer and inner structural design for superior water splitting. Adv. Mater. 29, 1704574 (2017).

Park, Y. H. et al. Recent trends in combinative defect engineering and hybridization approach to develop efficient energy-functional layered double hydroxide-based materials. Nano Res. Energy 4, e9120163 (2025).

Wang, C., Liu, K., Jin, Y., Huang, S. & Lam, J. C.-H. Amorphous RuO2 catalyst for medium size carboxylic acid to alkane dimer selective Kolbe electrolysis in an aqueous environment. ChemSusChem 16, e202300222 (2023).

Fukuda, K. et al. Synthesis of nanosheet crystallites of ruthenate with α-NaFeO2-related structure and its electrochemical supercapacitor property. Inorg. Chem. 49, 4391–4394 (2010).

Tsuji, E., Imanishi, A., Fukui, K. I. & Nakato, Y. Electrocatalytic activity of amorphous RuO2 electrode for oxygen evolution in an aqueous solution. Electrochim. Acta 56, 2009–2016 (2011).

Lee, J. M. et al. A conductive hybridization matrix of RuO2 two-dimensional nanosheets: a hybrid-type photocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 8546–8550 (2016).

Kim, T. W. et al. Bifunctional heterogeneous catalysts for selective epoxidation and visible light driven photolysis: nickel oxide-containing porous nanocomposite. Adv. Mater. 20, 539–542 (2008).

Kim, T. W., Han, A. R., Hwang, S.-J. & Choy, J.-H. Local atomic arrangement and electronic configuration of nanocrystalline zinc oxide hybridized with redoxable 2D lattice of manganese oxide. J. Phys. Chem. C 111, 16774–16780 (2007).

Park, H. M., Kim, T. W., Hwang, S.-J. & Choy, J.-H. Chemical bonding nature and mesoporous structure of nickel intercalated montmorillonite clay. Bull. Kor. Chem. Soc. 27, 1323–1328 (2006).

Chen, D. et al. Bicontinuous RuO2 nanoreactors for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 15, 3928 (2024).

Wang, Z., Lin, R., Huo, Y., Li, H. & Wang, L. Formation, detection, and function of oxygen vacancy in metal oxides for solar energy conversion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2109503 (2022).

Frati, F., Hunault, M. O. J. Y. & Groot, F. M. F. D. Oxygen K-edge X-ray absorption spectra. Chem. Rev. 120, 4056–4110 (2020).

Hu, Z. et al. Multiplet effects in the Ru L2,3 x-ray-absorption spectra of Ru(IV) and Ru(V) compounds. Phys. Rev. B 61, 5262 (2000).

Jin, X. et al. Crucial roles of interfacial coupling and oxygen defect in multifunctional 2D inorganic nanosheets. Nano Energy 67, 104192 (2020).

Tébar-Soler, C. et al. Low-oxidation-state Ru sites stabilized in carbon-doped RuO2 with low-temperature CO2 activation to yield methane. Nat. Mater. 22, 762–768 (2023).

Zhang, G. et al. Controllable intercalated polyaniline nanofibers highly enhancing the utilization of delaminated RuO2 nanosheets for high-performance hybrid supercapacitors. ChemElectroChem 9, e202200039 (2022).

Chen, R. S. et al. A comparative study of microstructure of RuO2 nanorods via Raman scattering and field emission scanning electron microscopy. Solid State Commun. 131, 349–353 (2004).

Liang, C. et al. Unravelling the effects of active site density and energetics on the water oxidation activity of iridium oxides. Nat. Catal. 7, 763–775 (2024).

Hu, C. et al. Misoriented high-entropy iridium ruthenium oxide for acidic water splitting. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf9144 (2023).

Xue, Y. et al. Stabilizing ruthenium dioxide with cation-anchored sulfate for durable oxygen evolution in proton-exchange membrane water electrolyzers. Nat. Commun. 14, 8093 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Amorphous MnRuOx containing microcrystalline for enhanced acidic oxygen-evolution activity and stability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202405641 (2024).

Zhai, P. et al. Regulating electronic states of nitride/hydroxide to accelerate kinetics for oxygen evolution at large current density. Nat. Commun. 14, 1873 (2023).

Car, R. & Parrinello, M. Structural, dynamical, and electronic properties of amorphous silicon: an ab initio molecular-dynamics study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 204–207 (1988).

Lee, S., Lee, Y., Lee, G. & Soon, A. Activated chemical bonds in nanoporous and amorphous iridium oxides favor low overpotential for oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 13, 3171 (2022).

Man, I. C. et al. Universality in oxygen evolution electrocatalysis on oxide surfaces. ChemCatChem 3, 1159–1165 (2011).

Zagalskaya, A. & Alexandrov, V. Role of defects in the interplay between adsorbate evolving and lattice oxygen mechanisms of the oxygen evolution reaction in RuO2 and IrO2. ACS Catal. 10, 3650–3657 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Unraveling oxygen vacancy site mechanism of Rh-doped RuO2 catalyst for long-lasting acidic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 14, 1412 (2023).

Jin, X., Jang, H., Jarulertwathana, J., Kim, M. G. & Hwang, S.-J. Atomically thin holey two-dimensional Ru2P nanosheets for enhanced hydrogen evolution electrocatalysis. ACS Nano 16, 16452–16461 (2022).

Timoshenko, J. et al. Deciphering the structural and chemical transformations of oxide catalysts during oxygen evolution reaction using quick X-ray absorption spectroscopy and machine learning. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 4065 (2023).

Gao, G. et al. Recent advances in Ru/Ir-based electrocatalysts for acidic oxygen evolution reaction. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 343, 123584 (2024).

Zhang, N. & Chai, Y. Lattice oxygen redox chemistry in solid-state electrocatalysts for water oxidation. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 4647–4671 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. High-valence oxides for high performance oxygen evolution electrocatalysis. Adv. Sci. 10, 2301706 (2023).

Zhu, Y., Zhou, W. & Shao, Z. Perovskite/carbon composites: applications in oxygen electrocatalysis. Small 13, 1603793 (2017).

Yao, N. et al. Atomically dispersed Ru oxide catalyst with lattice oxygen participation for efficient acidic water oxidation. Chem 9, 1882–1896 (2023).

Kang, B. et al. An effective way to improve bifunctional electrocatalyst activity of manganese oxide via control of bond competition. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 236, 107–116 (2018).

Zhang, Y.-C. et al. NiCo-based electrocatalysts for the alkaline oxygen evolution reaction: a review. ACS Catal. 11, 12485–12509 (2021).

Liu, H., Qi, Z. & Song, L. In situ electrocatalytic infrared spectroscopy for dynamic reactions. J. Phys. Chem. C 125, 24289 (2021).

Hu, Y. et al. Understanding the sulphur-oxygen exchange process of metal sulphides prior to oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 14, 1949 (2023).

Yao, L. et al. Sub-2 nm IrRuNiMoCo high-entropy alloy with iridium-rich medium-entropy oxide shell to boost acidic oxygen evolution. Adv. Mater. 36, 2314049 (2024).

Niu, Z. et al. Robust Ru-VO2 bifunctional catalysts for all-pH overall water splitting. Adv. Mater. 36, 2310690 (2024).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Zhang, Y. & Yang, W. Comment on “Generalized gradient approximation made simple”. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 890 (1998).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Crystal structure and pair potentials: a molecular-dynamics study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 1196 (1980).

Parrinello, M. & Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys 52, 7182 (1981).

Hansen, H. A., Rossmeisl, J. & Nørskov, J. K. Surface Pourbaix diagrams and oxygen reduction activity of Pt, Ag and Ni (111) surfaces studied by DFT. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10, 3722–3730 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00439825, RS-2023-00208355, RS-2024-00411134). This study was supported by the Project Code IBS-R006-A2 in Republic of Korea. T.L. and A.S. gratefully acknowledge support by the Basic Science Research Program through National Research Foundation of Korea (RS-2023-NR077023). Computational resources have been kindly provided by the KISTI Supercomputing Center (KSC-2024-CRE-0380). X.J. gratefully acknowledges support by the 2024 Advanced Facility Fund of the University of Seoul. The experiments at PAL were supported in part by MOST and POSTECH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.J. carried out synthesis, characterization, and electrocatalytic activity tests and wrote the manuscript; T.L. and A.S. contributed to DFT calculation and wrote the manuscript; J.P. and M.G.K. carried out in situ XANES/EXAFS measurement; J.K. and D.W.K. carried out in situ DEMS measurement and wrote the manuscript; S.P. and Y.-E.S. carried out AEMWE and PEMWE measurement and wrote the manuscript. Y.S.Y. carried out electrocatalytic activity tests; S.-J.H. contributed to the conception and design of the experiment, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to discussion and preparation of manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shichun Mu, Tao Yao, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, X., Lee, T., Park, J. et al. pH-dependent mechanism of oxygen evolution in highly disordered RuO2 nanosheets. Nat Commun 17, 672 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67318-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67318-y