Abstract

Achieving both high electroluminescence (EL) efficiency and power conversion efficiency (PCE) in a single organic device has long been considered difficult, since the design principles optimising one often compromise the other. In this study, we present a strategy employing multiple-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials with strong absorption and high emission efficiency, enabling coexistence of high EL and photovoltaic (PV) efficiencies. By precisely controlling charge-transfer states at donor/acceptor interfaces, we successfully achieve full-spectrum visible EL while maintaining efficient charge generation essential for PV operation. The optimised multifunctional devices exhibit emission colours ranging from blue to red, as well as white, with the green- and orange-light-emitting devices achieving an external quantum efficiency of EL exceeding 8.5% and a PCE of about 0.5%. These findings not only mitigate conventional efficiency trade-offs in organic devices but also open future avenues for emerging applications, including self-powered displays and lighting, potentially advancing optoelectronic technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the remarkable design flexibility of organic semiconductors has driven intensive research into a wide range of optical devices. Notable examples include organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), organic photovoltaics (OPVs), and various sensors, all of which have seen significant advancements in material development and performance enhancement1,2,3,4,5,6,7. The key factors governing the functionality of these light-emitting, energy-harvesting, and sensing devices are excitons and charge transfer (CT) states, which are bound states of an electron and a hole. In OLEDs, charge injection and transport lead to exciton/CT state formation, followed by radiative recombination that results in light emission8,9,10,11,12,13. Conversely, in OPVs and sensors, such as organic photodiodes (OPDs), the excitons/CT states generated by incident light must dissociate into free charges, which are subsequently transported and collected14,15,16,17. Therefore, precise control over exciton/CT state energy and dynamics holds the potential not only to enhance device performance but also to enable the development of dual-functional (DF) and multifunctional (MF) devices that integrate multiple functionalities, such as electroluminescence (EL) devices, photovoltaics (PVs), and PDs into a single platform18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Initially, many devices were reported as DF devices (EL devices and PVs). However, since PDs and PVs share similar operating mechanisms, DF devices can also function as MF devices (EL devices, PVs, and PDs). MF organic devices represent a groundbreaking technology with the potential to significantly contribute to both the advancement of an increasingly digitalized society and sustainable energy solutions. To enhance security in mobile displays, such as those in smartphones, OLED and OPD panels are being developed separately25. If a high-performance device integrating both EL and PD functions can be realised, there will no longer be a need for a separate OPD panel. Furthermore, if both EL and PV functions can be combined, it could enable mobile displays that recharge under indoor lighting or sunlight when not in use. While we note that the optimal PV device should ideally harvest part of the near-infrared spectrum of sunlight, which is difficult to exploit simultaneously for visible emission, the demonstration of efficient MF devices nonetheless suggests a pathway toward reducing charging needs and lowering the overall energy consumption of displays.

Despite several reports on the advances made on MF devices, achieving both high EL efficiency and power conversion efficiency (PCEPV, defined as the ratio of generated electrical power to incident optical power in photovoltaic operation) remains a significant challenge (open symbols in Fig. 1). The first reported DF device was fabricated employing rubrene as the electron-donating molecule (donor) and fullerene (C₆₀) as the electron-accepting molecule (acceptor). Although this device exhibited a PCEPV of about 3%, its external quantum efficiency (EQE) of EL emission (EQEEL) remained below 0.001%18. In this system, CT states are formed at the rubrene/C₆₀ interface with an energy (ECT) of about 1.46 eV in the near-infrared region (~ 850 nm)26. By utilising triplet–triplet annihilation (TTA), we can realise EL emission in the orange region (~560 nm). To date, almost all reported organic MF devices have been based on rubrene18,19,20,21. However, the EQEEL in all reported devices with rubrene remains below 0.001%. One of the primary reasons for this low EQEEL is the limited efficiency of TTA-based upconversion (TTA-UC)27. Furthermore, a major limitation in enhancing PV performance arises from the high exciton binding energy (Eb) of CT states. Although the Eb of CT states is considered lower than that of Frenkel excitons, which ranges from 0.2 to 1.2 eV, it often falls within the range of 0.2 to 0.6 eV28,29,30. A high Eb is desired to facilitate charge recombination in EL devices while hindering charge separation in PVs31,32. Thus, in organic-semiconductor-based devices, it is inherently challenging to achieve high performance in both EL and PV functions, as the design principles that enhance one often compromise the other. Recently, an orange-light-emitting MF device fabricated without utilising TTA-UC has been reported; its PCEPV remains at approximately 0.8% and its EQEEL is about 1.5%22,23. The only reported MF device in which high EQEEL and PCEPV are both successfully realised utilises quantum dots (QDs), achieving an EQEEL of 8% and a PCEPV of approximately 0.2%24. However, the emission colour of QD-based devices is restricted to red. To realise advanced devices, such as self-powered displays and lighting, it is necessary to overcome the trade-off between PCEPV and EQEEL and develop MF devices that exhibit various emission colours.

Here, we present the strategy for both material selection and device design to achieve MF devices with both high PCEPV and EQEEL, as well as the control of CT states to realise various emission colours ranging from blue to red. By using multiple-resonance thermally activated delayed fluorescence (MR-TADF) materials, which exhibit high emission efficiency and strong absorption, as the donor and acceptor materials with a low electron affinity (EA) of 2–3 eV, we successfully fabricated multiple MF devices exhibiting visible EL without utilising TTA-UC and a PCEPV exceeding 1%33,34,35. The Eb of the CT state was found to depend on the donor–acceptor combination, ranging from approximately 0 to 0.4 eV. It was revealed that Eb has a greater impact on the EL characteristics of MF devices than on their PV properties. Although the EL emission from the CT state (exciplex) is dominant in most devices, it was found that the emission colour can be tuned, as some devices exhibited EL from MR-TADF materials depending on the magnitude of Eb. On the basis of these insights, MF devices capable of emitting blue, green, yellow, orange, red, and white light are designed. Notably, the green- and orange-light-emitting devices achieved an EQEEL exceeding 8.5% and a PCEPV of about 0.5%, whereas MF devices emitting blue and white light exhibited an EQEEL of approximately 2% and a PCEPV exceeding 1% (Fig. 1).

Results

Device architecture and design for MF operation

The basic structure of the proposed MF device is illustrated in Fig. 2. This structure consists of a hole injection/extraction layer (HIL), a donor–acceptor pair responsible for exciton generation, and an electron injection/extraction layer (EIL). During EL emission, holes are injected from the anode and electrons from the cathode, leading to exciton formation and subsequent emission at the donor/acceptor interface (Fig. 2b). In this process, the observed emission may originate not only from the CT state exciplex of the donor–acceptor pair but also from the intrinsic emission of either the donor or the acceptor. Conversely, the charge and exciton dynamics during solar energy conversion are depicted in Fig. 2c, using the case where the donor absorbs light to generate electricity. Upon solar irradiation, the donor enters an excited state. The exciton’s electron then transfers to the acceptor, forming a CT state. The electron is subsequently extracted at the cathode, whereas the hole is extracted at the anode, generating electrical power. The ECT of this exciton is lower than the energy difference between the donor’s ionisation energy (IE) and the acceptor’s EA, denoted as the final charge-separated (CS) state energy (ECS), by an amount corresponding to the exciton binding energy (Eb). Eb can be determined from the difference between ECS, obtained using techniques, such as low-energy inverse photoemission spectroscopy (LEIPS), and ECT, derived from the EL spectrum of the exciplex29,36. By precisely controlling excitons in this manner, we can possibly realise an MF device that integrates both EL and PV functions.

a Schematic of MF devices with directions of charge flow for electroluminescence and photovoltaic. b,c Energy band diagram and the carrier/exciton dynamics in MF devices. d Chemical structure of materials used as the donor (blue characters) and acceptor (red characters). Rubrene is used as both the donor and the acceptor.

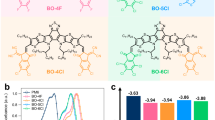

For the realisation of a highly efficient MF device, it is essential to select a donor–acceptor pair with an energy gap (ECS) exceeding 2 eV to ensure a large ECT. In conventional OPVs, donor–acceptor pairs with ECT below 1.5 eV have commonly been employed, as this design strategy enables the absorption of a broad solar spectrum, thereby achieving high power conversion efficiency3,4,5. However, in MF devices with ECT below 1.5 eV, the efficiency of TTA-UC is low, making it difficult to achieve high EQEEL. Therefore, to realise efficient visible-light emission, it is necessary to increase ECS and generate excitons with ECT exceeding 2 eV22,23,29. To meet this requirement, we employed the donor and acceptor materials widely used in OLEDs, as shown in Fig. 2d (Supplementary Table 1). In particular, MR-TADF materials exhibit not only high emission efficiency but also small Stokes shift, resulting in strong absorption in the solar spectrum37,38,39. Moreover, previous studies have shown that suppressing exciton losses due to triplet excited states is crucial for improving PCEPV15,40,41. From the perspective of triplet energy (ET) confinement, MR-TADF materials, which exhibit a small energy gap between the singlet and triplet states, are well suited for achieving both high EQEEL and PCEPV. Therefore, the utilisation of MR-TADF materials is expected to enable the development of high-performance MF devices. As acceptor materials, we selected TADF materials with an EA exceeding 2 eV, such as 5,10-bis(4-(9H-carbazol-9-yl)−2,6-dimethylphenyl)−5,10-dihydroboranthrene (CzDBA) and 13b-aza-naphtho(3,2,1-de)anthracene-5,9-dione (DikTA), in addition to electron transport materials (ETMs) with relatively high ET, such as 4,6-bis(3,5-di(pyridin-4-yl)phenyl)−2-methylpyrimidin (B4PyMPM) and 9-(4-(4,6-dipyridin −1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)phenyl)−9H-carbazole (Cz-TRZ-Py)42,43,44,45. The use of Py-hpp2 enables the reduction in the work function of the cathode to approximately 2.1 eV, allowing for efficient charge collection even from materials with an EA of 3 eV or lower45. Conversely, 3,3’-bi[1,4]benzoxazino[2,3,4-kl]phenoxazine (HN-D2), rubrene, and 9,10-bis[4-(6-methylbenzothiazol-2-yl)phenyl]anthracene (DBzA), which exhibit a relatively low ET, were used as reference materials46. In this study, we systematically adjusted the donor–acceptor combinations shown in Fig. 2d to achieve ECS values in the range of 2.0–2.7 eV and evaluated the corresponding device performance (Supplementary Table 2).

Dependence of EL on donor properties

Figure 3 presents the characteristics of MF devices fabricated by varying the donor material while fixing the acceptor material as CzDBA. The EL characteristics shown in Fig. 3a indicate that all devices exhibit current flow at applied voltages below 2 V, reaching a current density of approximately 100 mA cm−2 at around 4 V. This observation suggests an efficient charge injection at the electrode/organic semiconductor interface, while the low onset voltage for emission can also be attributed to the small Eb of the CT state, consistent with previous reports23. As discussed later, many of the devices investigated in this study indeed involve donor–acceptor pairs with relatively small CT-state Eb, which further supports the observed low-voltage EL operation. As shown in Fig. 3b, c, both luminance and EQEEL strongly depend on the donor material, with a maximum EQEEL of approximately 1.2%. Notably, only the devices fabricated employing donors with high ET values exhibited EQEEL values exceeding 0.5% (Supplementary Fig. 1a). In contrast, the low EQEEL observed in the device with rubrene is likely attributed to the low efficiency of TTA-UC. Whereas the device with rubrene exhibited emission from rubrene facilitated by TTA, all other devices predominantly exhibited EL spectra with peaks above 600 nm (Fig. 3d). Given that CzDBA has an emission peak of around 550 nm, the observed EL spectra above 600 nm are attributed to emission from the CT state (Supplementary Fig. 2a)8,9,10,11,12,13. From the onset of the EL spectra, the ECT of MF devices, excluding the device with rubrene, was estimated to be in the range of 1.96–2.5 eV (Supplementary Table 2)29. Furthermore, differences in donor emission intensity within the 450–550 nm wavelength range provide insights into the effect of Eb on exciton and charge behaviour (Supplementary Fig. 3a). As shown in Fig. 3e, a lower Eb correlates with a higher donor emission intensity relative to exciplex EL emission. This trend suggests that at the donor/acceptor interface, a low Eb facilitates exciton dissociation, enabling electrons to migrate to the donor side and contribute to emission (inset in Fig. 3e). A comparison between devices fabricated utilising N7,N7,N13,N13,5,9,11,15-octaphenyl-5,9,11,15-tetrahydro-5,9,11,15-tetraaza-19b,20b-diboradinaphtho[3,2,1-de:1′,2′,3′-jk]pentacene-7,13-diamine (ν-DABNA) and 9-([1,1’-biphenyl]−3-yl)-N,N,5,11-tetraphenyl-5,9-dihydro-5,9-diaza-13b-boranaphtho [3,2,1-de]anthracen-3-amine (DABNA-2), both with an EA of 1.4 eV, revealed that the device incorporating ν-DABNA, which has a lower Eb, exhibited a higher emission intensity. This result is notable given that the photoluminescent quantum yield (PLQY) of the neat film of ν-DABNA ( ~ 12%) is lower than that of DABNA-2 ( ~ 44%), yet a higher emission intensity was observed (Supplementary Table 3). Although this emission intensity is likely affected by the difference in EA between the donor and the acceptor, similar results were obtained even when donors with an EA of 2.1 eV were used (Supplementary Figs. 3a and 3b). These findings suggest that a lower Eb facilitates charge dissociation within the CT state, leading to an increase in donor emission intensity. In this study, several donor/acceptor interfaces exhibited an Eb of less than 0.2 eV (Fig. 3f). Although Eb increases with ECS, many Eb values are smaller than those observed in previous studies using typical arylamine-based donors and triazine-based acceptors29. Our results demonstrate that appropriate donor–acceptor combinations can reduce the Eb of the CT state to below 0.2 eV. It has been reported that non-fullerene acceptors exhibit a lower Eb when the number of fused rings and steric hindrance are greater31. Since MR-TADF materials and HN-D2 have a greater number of fused rings than typical arylamine-based donors, it is considered that the Eb of the CT state was reduced. Although it is difficult to quantitatively discuss the effect of the number of fused rings on Eb because the MR-TADF donors used in this study possess different fused-ring geometries, a clear influence of steric hindrance has been observed. A comparison between indolo[3,2,1-de]indolo[3’,2’,1’:8,1][1,4]benzazaborino[2,3,4-kl]phenazaborine (CzBN) and 2,6-bis(3,6-di-tert-butyl-9H-carbazol-9-yl)boron (DtBuCzB) suggests that the steric hindrance of the tertial butyl group is also effective in reducing Eb. Furthermore, a noticeable difference in Eb was also identified between 5,9-Diphenyl-5,9-diaza-13b-boranaphtho[3,2,1-de]anthracene (DABNA-1) and DABNA-2, which likely originates from the different degrees of steric hindrance around their boron centres. A more detailed discussion on the impact of Eb on emission characteristics will be presented in a later section.

a,b Current density–voltage (a) and luminance–voltage (b) characteristics of devices with different donors. (c), EQEEL traces of devices for electroluminescence. d Electroluminescence spectra of devices. (e), Correlation between EL intensity of donor and Eb of CT state. Inset: Schematic of emission mechanism from both the exciplex and the donor. (f), Eb of CT state as function of ECS. (g) Current–density voltage curves of devices measured under simulated AM1.5 G solar illumination. h Open-circuit voltage as a function of ECT.

Photovoltaic performance and energy-level correlations

Figure 3g presents the current density–voltage (J–V) characteristics of the devices measured under simulated AM1.5 G solar illumination. Owing to the large energy level difference between ECS and ECT, most devices exhibited a high VOC exceeding 1.5 V (Supplementary Table 2). In recent studies, devices with similarly high VOC have been demonstrated; however, their short-circuit current density (JSC) was limited to approximately 0.6 mA/cm² and no devices with PCEPVs exceeding 1% have been demonstrated22,23. In contrast, four devices with an MR-TADF material as the donor achieved a PCEPV of approximately 1% (Supplementary Table 2). PCEPV exhibits a strong correlation with the ET of the donor (Supplementary Fig. 4). This high PCEPV is attributed to the strong absorption of the MR-TADF material and its high ET, which effectively confines exciton energy. The photovoltaic EQE of devices employing MR-TADF materials as donors reached approximately 25%, which is comparable to the values reported for state-of-the-art OPDs based on MR-TADF materials (Supplementary Fig. 5)34. For comparison, we fabricated an MF device with 3Cz–Ph–TRZ as the donor, a representative donor–acceptor-type TADF material with an IE of 5.2 eV (Supplementary Fig. 6)47. However, this device exhibited a low PCEPV, primarily because of the poor absorption of 3Cz–Ph–TRZ in the solar spectrum. Additionally, the presence of CzDBA emission in the EL spectrum suggests that CT state formation at the donor/acceptor interface was suppressed. Although HN-D2 exhibits absorption at shorter wavelengths than MR-TADF materials, rubrene absorbs over a broader wavelength range (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Nevertheless, the JSC, fill factor (FF), and PCEPV of the rubrene-based device were significantly lower than those of the other devices. Rubrene has been reported to achieve VOC = 0.9 V, JSC > 2 mA/cm², and PCEPV > 2% in stacked OPVs with C6018. However, in our rubrene–CzDBA-based MF device, no exciplex emission was observed, yet a VOC of 1.85 V was obtained. This suggests that ECT exceeds 2 eV, which is significantly higher than that of conventional donor–acceptor systems, such as rubrene–C60. The ET of rubrene is 1.14 eV, meaning that high-ECT excitons formed at the rubrene/CzDBA interface are likely to undergo rapid nonradiative deactivation15,40,41. Fig. 3h shows the correlation between VOC and ECT. In recent studies, OPVs with ECT values exceeding 2 eV have been reported to exhibit small VOC losses, and similar results were obtained in this study23. For conventional OPVs with lower ECT, the VOC loss is typically large, and VOC is reported to fall within the range of VOC = ECT/e − 0.5 ∼ ECT/e − 0.7 V23,48. However, as shown in Fig. 3h, most devices in this study exhibited small VOC losses, which can be attributed to the low Eb. These results indicate that the use of MR-TADF materials enables the realisation of MF devices with both high PCEPV and minimal VOC loss. In MF devices with CzDBA as the acceptor, which emits orange light, EL emission was limited to the orange–red spectral range42. To explore the feasibility of MF devices with diverse emission colours, we fabricated devices with different donor–acceptor combinations.

Emission colour tuning and role of exciton binding energy

When ν-DABNA was used as the donor with various acceptors, MF devices exhibited a wide range of emission colours (Fig. 4a). As shown in Supplementary Figs. 7a–c, the J–V–L characteristics and EQEEL exhibited values similar to those of MF devices with CzDBA as the acceptor. Additionally, a significant decrease in EQEEL was observed in devices fabricated using acceptors with a lower ET, such as rubrene and DBzA (Supplementary Fig. 1b). A particularly noteworthy observation is the differences in EL spectra between devices with B4PyMPM and Cz–TRZ–Py as acceptors, despite both having comparable EAs. The device incorporating Cz–TRZ–Py exhibited strong exciplex emission, whereas the device with B4PyMPM showed predominantly ν-DABNA emission. This difference can be understood by considering Eb, as illustrated in Fig. 4b. In the device with B4PyMPM, which has an Eb of 0.1 eV, excitons readily dissociate, leading to strong donor emission. Conversely, in the device with Cz–TRZ–Py, which has a relatively high Eb of 0.25 eV, the exciplex emission was predominantly observed. The high Eb observed in the device with Cz–TRZ–Py is considered to be due to the localisation of the LUMO on the triazine side, as well as the absence of steric hindrance (Supplementary Fig. 8)47. For all the CT states examined so far, the least-squares fitting of Eb as a function of ECS yielded a slope of approximately 0.3, which is intriguingly similar to the slope of 0.25 reported for isolated molecules30. Because reports on the Eb of CT states are still scarce, we anticipate that acquiring more data will allow a more detailed analysis in the future. Figure 4c shows the correlation between the maximum EQEEL and Eb in devices where exciplex emission was the dominant luminescence. The observed trend of lower EQEEL for lower Eb suggests that a certain threshold Eb is required for the formation and radiative recombination of CT states. Furthermore, in donor–acceptor blend films, a positive correlation was observed between Eb and the PLQY of exciplex emission (Supplementary Fig. 9). While the PLQY of the individual donor and acceptor may also influence the exciplex PLQY, the current dataset is limited, and further data collection will be required to clarify these potential effects. These findings highlight the strong effect of Eb on both the emission colour and efficiency of MF devices.

a Electroluminescence spectra of devices. b Schematic of mechanism of emission from both the exciplex and the donor. c Correlation between maximum EQEEL and Eb of CT state. d Current–density voltage curves of devices measured under simulated AM1.5 G solar illumination. e PCEPV as a function of ET of acceptor. f PCEPV of MF devices fabricated using MR-TADF material as a function of Eb of CT state.

Figure 4d presents the J–V curves of devices measured under simulated AM1.5 G solar illumination. As similarly observed in Fig. 3g high VOC exceeding 1.5 V was achieved in many of the devices, with a maximum PCEPV of approximately 1.5%. As shown in Fig. 4e strong correlation was also observed between PCEPV and the acceptor’s ET. Since light absorption in the devices shown in Fig. 4 is primarily attributed to ν-DABNA, the correlation between JSC and ET was analysed to further elucidate the effect of ET on exciton generation (Supplementary Fig. 10). High JSC was obtained for acceptors with ET above 2.4 eV, indicating that the insufficient confinement of ET leads to exciton quenching. On the other hand, in the MF devices fabricated employing MR-TDAF materials shown in Figs. 3 and 4, high PCEPV was achieved even when Eb was around 0.4 eV, and no clear correlation between PCEPV and Eb was observed (Fig. 4f). This can be attributed to the simple donor/acceptor stacked structure of the devices. The electron mobility of a tBuCzDBA neat film is on the order of 10–6 cm2 V–1 s–1, whereas that of a CzDBA neat film is on the order of 10–5 cm2 V–1 s–1. Nevertheless, the PCEPV of ν-DABNA-based MF devices was comparable in both cases, suggesting that a one-order difference in electron mobility exerts only a minor influence on PCEPV (Figs. 4e and 4f)49,50. In contrast, in the OLED characteristics (J–V curves) of the ν -DABNA-based MF devices, those employing tBuCzDBA required a higher operating voltage (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 7a). Although no clear correlation was observed between Eb and PCEPV (Fig. 4f), a trend was identified in which a larger ECT led to a higher PCEPV (Supplementary Fig. 11a). This can be attributed to the fact that an increased ECT results in a higher VOC (Supplementary Fig. 11b). These PCEPV values were higher than those reported for recently developed MF devices with VOC exceeding 1.5 V, demonstrating the effectiveness of MR-TADF materials23.

Realization of high-efficiency multicolour MF devices

On the basis of the obtained EL and PV characteristics and physical properties, such as Eb, MF devices exhibiting various emission colours were successfully realised. The device configurations, along with their emission and PV characteristics, are shown in Fig. 5 (Supplementary Fig. 12, Supplementary Table 4). For blue-, green-, and yellow-light-emitting MF devices, DABNA-2 was selected as the donor because of its high PLQY in both neat and blended films (Supplementary Table 3). For demonstrating the blue-light-emitting device, B4PyMPM was chosen as the acceptor to minimise Eb, ensuring that the emission originated from DABNA-2. Although the Eb of the CT state in the blue-light-emitting device was estimated to be 0.21 eV, blue emission from DABNA-2 was mainly observed. The blue-light-emitting device exhibits an EQEEL of 2% and a PCEPV of 1%. To utilise the high PLQY of the DABNA-2 doped with B4PyMPM film (44%), a doped layer was introduced into the green-light-emitting device. As a result, an EQEEL exceeding 8.5% was achieved. Considering the PLQY of 44% and a light outcoupling efficiency of approximately 20%, this EQEEL suggests that almost all generated excitons were efficiently converted into light51. However, the PCEPV was lower than that of a simple donor/acceptor stacked device. This reduction in PCEPV is attributed to the large energy differences in IE and EA between DABNA-2 and B4PyMPM, which led to charge trapping. Furthermore, by using Cz-TRZ-Py, which is an acceptor with higher Eb, in the same device structure as the blue device, we obtained a yellow-light-emitting MF device. The Eb of the CT state of DABNA–2/Cz–TRZ–Py was estimated to be 0.41 eV. This device exhibited a similar PCEPV ( ~ 1%) to the blue-light-emitting device and achieved an EQEEL of approximately 5%. To further examine the possible influence of carrier injection and transport on the EL spectra, we compared four MF devices using ν-DABNA or DABNA-2 as donors and B4PyMPM or Cz-TRZ-Py as acceptors (Supplementary Fig. 13). The results suggest that differences in hole-injection and transport between ν-DABNA and DABNA-2 may have some influence on exciton dissociation, but the effect appears less significant than that of Eb. In the devices employing ν-DABNA as the donor, the smaller IE of ν-DABNA led to higher current density and earlier hole arrival at the donor/acceptor interface. In such a situation, increased hole flux to the interface would generally be expected to suppress donor emission; however, strong donor emission was observed specifically in the devices with B4PyMPM, which yielded smaller Eb values. These results indicate that, for emission-colour modulation in MF devices, the influence of Eb outweighs that of donor-dependent carrier injection and transport. By blending tBuCzDBA and DtBuCzB, we realised an orange-light-emitting MF device, demonstrating comparable PCEPV and EQEEL to the green-light-emitting device. To further clarify the emission origin, the PL spectra of the three mixed films corresponding to the green-, yellow-, and orange-emitting devices are shown in Supplementary Fig. 14. These results confirm that the green, yellow, and orange EL emissions mainly originate from CT states. MF devices, such as the green- and orange-light-emitting devices, which simultaneously achieved an EQEEL exceeding 8.5% and a PCEPV of about 0.5%, were not reported previously, marking the realisation of the highest-performance MF devices to date (Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables 4, 5 and 6). These devices employed doped layers that exhibited higher PLQY than the corresponding undoped films, and the expansion of the recombination region achieved through the introduction of the doped layer further enhanced EQEEL. This combination of improved radiative efficiency and a broadened recombination region likely explains the higher EQEEL observed in the green and orange devices compared with the blue and red ones. By precisely controlling the behaviour of charges, excitons, and CT states, we successfully realised MF devices using organic semiconductors with both high EL and power conversion efficiencies, which was previously considered challenging. It was also discovered that by doping additional emissive materials into the device, in addition to the donor–acceptor materials required for PV conversion, the emission colour could be further expanded (R/W device). The MF device doped with tris(1-phenylisoquinoline)iridium(III) [Ir(piq)3], a red phosphorescent dopant, exhibited red emission at low current densities and white emission at high current densities52. In contrast, other MF devices showed minimal emission colour variation with current density (Supplementary Fig. 15).

a Schematic illustration and picture of optimised devices with various emission colours. b Luminance–voltage–current density characteristics of devices. c EQEEL–current density characteristics of the devices. d Corresponding 1931 CIE coordinates of device emission. e Electroluminescence spectra of devices. f Current density–voltage curves of devices measured under simulated AM1.5 G solar illumination.

The realisation of MF devices exhibiting various emission colours significantly broadens their potential applications. The successful demonstration of MF devices capable of RGB emission suggests that, when implemented in display technology, display panels could be designed to harvest ambient light for charging when not in use. Furthermore, the realisation of white emission highlights the feasibility of emerging applications, such as self-powered lighting. Currently, the operational stability of these MF devices remains limited; however, optimising materials and device architectures is expected to extend their lifetime (Supplementary Fig. 16). The blue device exhibited a shorter EL lifetime but a longer PV lifetime than the yellow device. Although both devices showed comparable PCEPV values, the higher EL efficiency of the yellow device was accompanied by a shorter PV lifetime, suggesting that achieving both high efficiency and long-term stability remains challenging. Continued material development will be essential to address this trade-off. Notably, in 2024, an OPV, which features a donor/acceptor stacked structure similar to that used in this study, was reported to achieve a PCEPV exceeding 20% with high stability4. Building on these findings, further improvements in both the efficiency and stability of MF devices can be anticipated. In particular, the development of MR-TADF materials with high PLQY in both neat and highly doped films holds great promise for significantly enhancing the EQEEL of MF devices. In this study, although the PCEPV was limited to a maximum of ~1.5%, we obtained several indications that point toward possible strategies for improvement. For example, in MF devices incorporating a mixed film of ν-DABNA and CzDBA, increasing the mixed film thickness led to a higher JSC but a reduced FF (Supplementary Fig. 17). This behaviour can be explained by the fact that a thicker mixed layer increases the number of charge-generating interfaces, while the decrease in FF is likely caused by a large offset between the IE and EA of ν-DABNA and CzDBA. Furthermore, in MF devices employing HN-D2 together with DikTA, which possesses a complementary absorption range, we observed an enhancement in JSC similar to that typically seen in bulk-heterojunction OPVs (Supplementary Fig. 18)43. These results suggest that the use of mixed layers containing donor/acceptor pairs with complementary absorption spectra, combined with carefully designed energy levels that do not hinder charge transport, can provide a pathway to further improvement in PCEPV. To achieve a balance between high EQEEL and PCEPV, a deeper understanding of the influence of Eb is also crucial. Although this study mainly focused on simple donor/acceptor-stacked structures, further clarification of how Eb affects device characteristics in doped-film-based MF devices will be essential for identifying its optimal range.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated the simultaneous realisation of both high EQEEL and PCEPV in a single organic MF device. By employing MR-TADF materials with both strong absorption and high photoluminescence efficiency, we successfully overcame efficiency trade-offs and simultaneously enhanced EQEEL and PV performance. The use of MR-TADF materials led to significant reductions in Eb compared with conventional organic semiconductors, with donor–acceptor Eb values ranging from approximately 0 to 0.4 eV. Notably, MF devices with lower Eb exhibited remarkably small VOC losses, whereas its impact on PCEPV remained relatively minor. Eb proved to be a key factor for determining both emission colour and emission efficiency, underscoring its critical role in MF device performance. These findings highlight the importance of precise Eb control for optimising device efficiency and achieving emission colour tuning from blue to red. Ultimately, this work provides a strategy for overcoming efficiency trade-offs in organic devices and paves the way to next-generation applications, such as self-powered displays and lighting, where EL and PV functions are seamlessly integrated into a single platform.

Methods

Fabrication of MF devices (MF devices)

The MF devices shown in Figs. 3 and 4 were fabricated on glass substrates coated with a 100-nm-thick ITO layer. Prior to the fabrication of the organic layers, the substrate was cleaned using ultrapurified water and organic solvents, and by UV–ozone treatment. After the UV–ozone treatment, Clevios HIL 1.3 N (supplied by Heraeus Holding GmbH) was spun onto the substrate to form a 10-nm-thick layer. The other organic layers were sequentially deposited onto the substrate. The film structure of the OLEDs was ITO (100 nm)/Clevios HIL 1.3 N (10 nm)/donor (30 nm)/acceptor (30 nm)/Py-hpp2 (3 nm), where Py-hpp2 is 2,6bis(1,3,4,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2H-pyrimido[1,2-a]pyrimidin-1-yl)pyridine. After the formation of Py-hpp2, a 100-nm-thick Al layer was deposited as the cathode. The devices were encapsulated using a UV-epoxy resin, a glass cover, and a desiccant in a nitrogen atmosphere after cathode formation.

MF devices with various emission colours (shown in Fig. 5) were fabricated similarly to the simple-structure OLEDs except for the organic layer. The film structure of the MF devices was ITO/Clevios HIL 1.3 N (10 nm)/organic layers/Py-hpp2 (3 nm). The organic layers used for each device were DABNA-2 (30 nm)/B4PyMPM (30 nm) for blue emission, DABNA-2 (30 nm)/DABNA-2 doped with B4PyMPM (50 wt% 10 nm)/B4PyMPM (30 nm) for green emission, DABNA-2 (30 nm)/Cz-TRZ-Py (40 nm) for yellow emission, DtBuCzB (30 nm)/ DtBuCzB doped with tBuCzDBA (50 wt% 20 nm)/ tBuCzDBA (40 nm) for orange emission, and v-DABNA (40 nm)/B4PyMPM (5 nm)/B4PyMPM: Ir(piq)3 (1 wt%, 3 nm)/ B4PyMPM (22 nm) for red/white emission. After the formation of Py-hpp2, a 100-nm-thick Al layer was deposited as the cathode. The devices were encapsulated using a UV-epoxy resin, a glass cover, and a desiccant in a nitrogen atmosphere after cathode formation.

Materials were purchased from Luminescence Technology Corporation and Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd. We used them after sublimation.

Device characterization

The EL spectra and luminance were measured using a spectroradiometer (Minolta CS-1000). A digital SourceMeter (Keithley 2400) and a desktop computer were used to operate the devices. We assumed that the emission from MF devices was isotropic so that the luminance was Lambertian; thus, we calculated EQEEL from the luminance, current density, and EL spectra. Current–voltage characteristics in the dark and under solar illumination were measured with a Keithley 2400 at room temperature under ambient conditions. The cells were illuminated with a spectrally mismatch-corrected intensity of 100 mW cm−2 (AM1.5 G) provided by a sun simulator (OTENTO-SUNⅢFNS, Bunkokeiki Co., Ltd.), with intensity calibration via a standard silicon photodiode. The device areas were 3 × 3 mm2. To confirm the validity of the experimental results, devices with identical structures were fabricated on different experimental days. The variation in both EQEEL and PCEPV among these devices was found to be less than 2%, indicating that the device-to-device variation is small (see Supplementary Fig. 19). Photovoltaic EQE and response spectra of the devices were collected using a Spectral sensitivity measurement system VC-250 (Bunkokeiki Co., Ltd.) under zero-bias conditions.

IE and EA measurements

The IE of the materials was determined by the spectroscopic measurement of photoemission in the air (AC-3, Rikenkeiki). The LEIPS spectra of organic thin films deposited on glass/ITO using a vacuum evaporation system were measured using an LEIPS measurement system (ALS Technology Co., Ltd.). No discernible dependence on the sample current or photon energy was observed, confirming that the LEIPS spectra were free from sample charging. A bandpass filter with a centre wavelength of 260 nm was used. The onset of an LEIPS spectrum was determined as the intersection of the straight line fitted to the onset region of the spectrum and the baseline.

Photoluminescence (PL) measurement

The 50-nm-thick organic films used for optical measurements were fabricated on clean quartz substrates by thermal evaporation. The PL spectra of the films and the transient PL characteristics were recorded using a spectrofluorometer (Horiba Jobin Yvon, FluoroMax-4). The excitation wavelength for all PL measurements was 350 or 355 nm. The sample PLQY was measured using a PL quantum yield measurement system (Hamamatsu Photonics, Quantaurus-QY).

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are provided in the article and its Supplementary Information. No additional raw data files are required to interpret or reproduce the results.

References

Tang, C. W. Two-layer organic photovoltaic cell. Appl. Phys. Lett. 48, 183–185 (1986).

Tang, C. W. & VanSlyke, S. A. Organic electroluminescent diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 51, 913–915 (1987).

Yan, C. et al. Non-fullerene acceptors for organic solar cells. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 1–19 (2018).

Zhu, L. et al. Achieving 20.8% organic solar cells via additive-assisted layer-by-layer fabrication with bulk p-i-n structure and improved optical management. Joule 8, 3153–3168 (2024).

Jiang, Y. et al. Non-fullerene acceptor with asymmetric structure and phenyl-substituted alkyl side chain for 20.2% efficiency organic solar cells. Nat. Energy 9, 975–986 (2024).

Fuentes-Hernandez, C. et al. Large-area low-noise flexible organic photodiodes for detecting faint visible light. Science 370, 698–701 (2020).

Lan, Z. et al. Near-infrared and visible light dual-mode organic photodetectors. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaw8065 (2020).

Goushi, K., Yoshida, K., Sato, K. & Adachi, C. Organic light-emitting diodes employing efficient reverse intersystem crossing for triplet-to-singlet state conversion. Nat. Photon. 6, 253–258 (2012).

Sarma, M., Chen, L.-M., Chen, Y.-S. & Wong, K.-T. Exciplexes in OLEDs: principles and promises. Mater. Sci. Eng., R. 150, 100689 (2022).

Chen, D. et al. Fluorescent organic planar pn heterojunction light-emitting diodes with simplified structure, extremely low driving voltage, and high efficiency. Adv. Mater. 28, 239–244 (2016).

Chen, D. et al. Modulation of exciton generation in organic active planar PN heterojunction: toward low driving voltage and high-efficiency OLEDs employing conventional and thermally activated delayed fluorescent emitters. Adv. Mater. 28, 6758–6765 (2016).

Li, B. et al. An effective strategy toward high-efficiency fluorescent OLEDs by radiative coupling of spatially separated electron–hole pairs. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 5, 1800025 (2018).

Liu, D. et al. Highly horizontal oriented tricomponent exciplex host with multiple reverse intersystem crossing channels for high-performance narrowband electroluminescence and eye-protection white organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 36, 2403584 (2024).

Clarke, T. M. & Durrant, J. R. Charge photogeneration in organic solar cells. Chem. Rev. 110, 6736–6767 (2010).

Chen, Z. et al. Triplet exciton formation for non-radiative voltage loss in high-efficiency nonfullerene organic solar cells. Joule 5, 1832–1844 (2021).

Lee, J. et al. Charge transfer state versus hot exciton dissociation in polymer−fullerene blended solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11878–11880 (2010).

Zhou, Y. et al. Observation of a charge transfer state in low-bandgap polymer/fullerene blend systems by photoluminescence and electroluminescence studies. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19, 3293–3299 (2009).

Pandey, A. K. & Nunzi, J.-M. Rubrene/fullerene heterostructures with a half-gap electroluminescence threshold and large photovoltage. Adv. Mater. 19, 3613–3617 (2007).

Engmann, S. et al. Higher order effects in organic LEDs with sub-bandgap turn-on. Nat. Commun. 10, 227 (2019).

Yamada, M., Naka, S. & Okada, H. Light-emitting organic photovoltaic devices based on rubrene/PTCDI-C13 Stack. Electrochemistry 85, 280–282 (2017).

Lou, Y., Wang, Z., Naka, S. & Okada, H. Bi-functional electroluminescent and photovoltaic devices based on rubrene-doped poly(3-hexylthiophene):1-(3-methoxycarbonyl)-propyl-1-phenyl-(6,6)C61 blends. Syn. Met. 162, 281–284 (2012).

Jia, X. et al. Molecularly induced order promotes charge separation through delocalized charge-transfer states at donor–acceptor heterojunctions. Mater. Horiz. 11, 173–183 (2024).

Ullbrich, S. et al. Emissive and charge-generating donor–acceptor interfaces for organic optoelectronics with low voltage losses. Nat. Mater. 18, 459–464 (2019).

Oh, N. et al. Double-heterojunction nanorod light-responsive LEDs for display applications. Science 355, 616–619 (2017).

Hendy, I. & Bouthinon, B. OLED smartphone 2.0 and AIO OPD sensing: the future of smartphone OLED and security. J. Inf. Disp. 39, 21–26 (2023).

Izawa, S., Morimoto, M., Naka, S. & Hiramoto, M. Efficient interfacial upconversion enabling bright emission at an extremely low driving voltage in organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2101710 (2022).

Ieuji, R., Goushi, K. & Adachi, C. Triplet–triplet upconversion enhanced by spin–orbit coupling in organic light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 10, 5283 (2019).

Campbell, I. H., Hagler, T. W., Smith, D. L. & Ferraris, J. P. Direct measurement of conjugated polymer electronic excitation energies using metal/polymer/metal structures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 1900–1903 (1996).

Satoh, C. et al. Bandgap engineering for ultralow-voltage operation of organic light-emitting Diodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 2300683 (2023).

Sugie, A., Nakano, K., Tajima, K., Osaka, I. & Yoshida, H. Dependence of exciton binding energy on bandgap of organic semiconductors. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14, 11412–11420 (2023).

Zhu, Y. et al. Exciton binding energy of non-fullerene electron acceptors. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 3, 2100184 (2022).

Small exciton binding energies enabling direct charge photogeneration towards low-driving-force organic solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 15348–15353 (2021).

Hatakeyama, T. et al. Ultrapure blue thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules: efficient HOMO–LUMO separation by the multiple resonance effect. Adv. Mater. 28, 2777–2781 (2016).

Yao, X. et al. High External quantum efficiency and ultra-narrowband organic photodiodes using single-component photoabsorber with multiple-resonance effect. Adv. Mater. 37, 2414465 (2025).

Mamada, M., Hayakawa, M., Ochi, J. & Hatakeyama, T. Organoboron-based multiple-resonance emitters: synthesis, structure–property correlations, and prospects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 1624–1692 (2024).

Yoshida, H. & Yoshizaki, K. Electron affinities of organic materials used for organic light-emitting diodes: a low-energy inverse photoemission study. Org. Electron. 20, 24–30 (2015).

Kondo, Y. et al. Narrowband deep-blue organic light-emitting diode featuring an organoboron-based emitter. Nat. Photon. 13, 678–682 (2019).

Xu, Y. et al. Molecular-structure and device-configuration optimizations toward highly efficient green electroluminescence with narrowband emission and high color purity. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 1902142 (2020).

Kim, H. J. & Yasuda, T. Narrowband emissive thermally activated delayed fluorescence materials. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2201714 (2022).

Rao, A. et al. The role of spin in the kinetic control of recombination in organic photovoltaics. Nature 500, 435–439 (2013).

Wang, R. et al. Nonradiative triplet loss suppressed in organic photovoltaic blends with fluoridated nonfullerene acceptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 4359–4366 (2021).

Wu, T.-L. et al. Diboron compound-based organic light-emitting diodes with high efficiency and reduced efficiency roll-off. Nat. Photon. 12, 235–240 (2018).

Hall, D. et al. Improving processability and efficiency of resonant TADF emitters: a design strategy. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8, 1901627 (2020).

Sasabe, H. et al. Influence of substituted pyridine rings on physical properties and electron mobilities of 2-methylpyrimidine skeleton-based electron transporters. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 336–342 (2011).

Sasaki, T. et al. Unravelling the electron injection/transport mechanism in organic light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 12, 2706 (2021).

Wakamiya, A. et al. On-Top π-stacking of quasiplanar molecules in hole-transporting materials: inducing anisotropic carrier mobility in amorphous films. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 5800–5804 (2014).

Hirata, S. et al. Highly efficient blue electroluminescence based on thermally activated delayed fluorescence. Nat. Mater. 14, 330–336 (2015).

Benduhn, J. et al. Intrinsic non-radiative voltage losses in fullerene-based organic solar cells. Nat. Energy 2, 1–6 (2017).

Liu, W., Kotadiya, N. B., Blom, P. W. M., Wetzelaer, G.-J. A. H. & Andrienko, D. Molecular origin of balanced bipolar transport in neat layers of the emitter CzDBA. Adv. Mater. Technol. 6, 2000120 (2021).

Wu, T.-L. et al. Substituent engineering of the diboron molecular architecture for a nondoped and ultrathin emitting layer. Chem. Sci. 12, 12996–13005 (2022).

Lin, C.-L., Cho, T.-Y., Chang, C.-H. & Wu, C.-C. Enhancing light outcoupling of organic light-emitting devices by locating emitters around the second antinode of the reflective metal electrode. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 081114 (2006).

Tsuboyama, A. et al. Homoleptic cyclometalated iridium complexes with highly efficient red phosphorescence and application to organic light-emitting diode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 12971–12979 (2003).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Heraeus Holding GmbH for supplying Clevios HIL 1.3. T.H. acknowledges Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) CREST (grant no. JPMJCR22B3, T.H.). This research was financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (grant no. 24K23071, H.F.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.O. and Y.A. fabricated the MF devices and measured their characteristics with help from T.Ok., T.S., and H.S. T.H. and T.Sh. revised the manuscript. H.F. supervised the project and wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oono, T., Aoki, Y., Sasaki, T. et al. A pathway to coexistence of electroluminescence and photovoltaic conversion in organic devices. Nat Commun 17, 694 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67332-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67332-0