Abstract

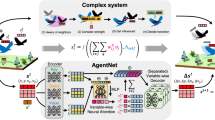

Despite their groundbreaking performance, autonomous agents can misbehave when training and environmental conditions become inconsistent, with minor mismatches leading to undesirable behaviors or even catastrophic failures. Robustness towards these training-environment ambiguities is a core requirement for intelligent agents and its fulfillment is a long-standing challenge towards their real-world deployments. Here, we introduce a Distributionally Robust Free Energy model (DR-FREE) that instills this core property by design. Combining a robust extension of the free energy principle with a resolution engine, DR-FREE wires robustness into the agent decision-making mechanisms. Across benchmark experiments, DR-FREE enables the agents to complete the task even when, in contrast, state-of-the-art models fail. This milestone may inspire both deployments in multi-agent settings and, at a perhaps deeper level, the quest for an explanation of how natural agents – with little or no training – survive in capricious environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A popular approach to designing autonomous agents is to feed them with data, using Reinforcement Learning (RL) and simulators to train a policy (Fig. 1a). Deep RL agents designed on this paradigm have demonstrated remarkable abilities, including outracing human champions in Gran Turismo1, playing Atari games2, controlling plasmas3, and achieving champion-level performance in drone races4. However, despite their groundbreaking performance, state-of-the-art agents cannot yet compete with natural intelligence in terms of policy robustness: natural agents have, perhaps through evolution, acquired decision-making abilities so that they can function in challenging environments despite little or no training5,6,7. In contrast, for artificial agents, even when they have access to a high fidelity simulator, the learned policies can be brittle to mismatches, or ambiguities, between the model available during learning and the real environment (Fig. 1b). For example, drone-champions and Atari-playing agents assume consistent environmental conditions from training, and if this assumption fails, because, e.g., the environment illumination or color of the objects changes, or the drone has a malfunctioning—so that its dynamics becomes different from the one available during training—learned policies can fail. More generally, model ambiguities—even if minor—can lead to non-robust behaviors and failures in open-world environments8. Achieving robustness towards these training/environment ambiguities is a long-standing challenge9,10,11 for the design of intelligent machines5,12,13 that can operate in the real world.

a A robotic agent navigating a stochastic environment to reach a destination while avoiding obstacles. At a given time-step, k − 1, the agent determines an action Uk from a policy using a model of the environment (e.g., available at training via a simulator possibly updated via real world data) and observations/beliefs (grouped in the state Xk−1). The environment and model can change over time. Capital letters are random variables, lower-case letters are realizations. b The trained model and the agent environment differ. This mismatch is a training/environment (model) ambiguity: for a state/action pair, the ambiguity set is the set of all possible environments that have statistical complexity from the trained model of at most \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). We use the wording trained model in a very broad sense. A trained model is any model available to the agent offline: for example, this could be a model obtained from a simulator or, for natural agents, this could be hardwired into evolutionary processes or even determined by prior beliefs. c A free energy minimizing agent in an environment matching its own model. The agent determines an action by sampling from the policy \({\pi }_{k}^{\star }({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\). Given the model, the policy is obtained by minimizing the variational free energy: the sum of a statistical complexity (with respect to a generative model, q0:N) and expected loss (state/action costs, \({c}_{k}^{(x)}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})\) and \({c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\)) terms. d DR-FREE extends the free energy principle to account for model ambiguities. According to DR-FREE, the maximum free energy across all environments—in an ambiguity set—is minimized to identify a robust policy. This amounts to variational policy optimization under the epistemic uncertainty engendered by ambiguous environment.

Here we present DR-FREE, a free energy14,15 computational model that addresses this challenge: DR-FREE instills this core property of intelligence directly into the agent decision-making mechanisms. This is achieved by grounding DR-FREE in the minimization of the free energy, a unifying account across information theory, machine learning16,17,18,19,20,21,22, neuroscience, computational and cognitive sciences23,24,25,26,27,28,29. The principle postulates that adaptive behaviors in natural and artificial agents arise from the minimization of the variational free energy (Fig. 1c). DR-FREE consists of two components. The first component is an extension of the free energy principle: the distributionally robust (DR) free energy (FREE) principle, which fundamentally reformulates how free energy minimizing agents handle ambiguity. While models based on the classic free energy principle (Fig. 1c) obtain a policy by minimizing the free energy based on a model of the environment available to the agent, under our robust principle, free energy is instead minimized across all possible environments within an ambiguity set around a trained model. The set is defined in terms of statistical complexity around the trained model. This means that the actions of the agent are sampled from a policy minimizing the maximum free energy across ambiguities. The robust principle yields the problem statement for policy computation. This is a distributionally robust problem having a free energy functional as objective and ambiguity constraints formalized in terms of statistical complexity. The problem has not only a nonlinear cost functional with nonlinear constraints but also probability densities over decision variables that equip agents with explicit estimates of uncertainty and confidence. The product of this framework is a policy that minimizes free energy and is robust across model ambiguities. The second key component of DR-FREE—its resolution engine—is the method to compute this policy. In contrast to conventional approaches for policy computation based on the free energy principle, our method shows that the policy can be conveniently found by first maximizing the free energy across model ambiguities—furnishing a cost under ambiguity—and then minimizing the free energy in the policy space (Fig. 1d). Put simply, policies are selected under the best worst-case scenario, where the worst cases accommodate ambiguity. Our robust free energy principle yields—when there is no ambiguity—a problem statement for policy computation naturally arising across learning21,30,31—in the context of maximum diffusion (MaxDiff) and maximum entropy (MaxEnt)—and control32. This means that DR-FREE can yield policies that not only inherit all the desirable properties of these approaches but ensures them across an ambiguity set, which is explicitly defined in the formulation. In MaxEnt—and MaxDiff—robustness depends on the entropy of the optimal policy, with explicit bounds on the ambiguity set over which the policy is robust available in discrete settings31. To compute a policy that robustly maximizes a reward, MaxEnt is used with a different, pessimistic, reward31; this is not required in DR-FREE. These desirable features of our free energy computational model are enabled by its resolution engine. This is the method tackling the full distributionally robust, nonlinear and infinite-dimensional policy computation problem arising from our robust principle; see “Results” and Sec. S2 in Supplementary Information for details. In Supplementary Information we also highlight a connection with the Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) formalism. DR-FREE yields a policy with a well-defined structure: this is a soft-max with its exponent depending on ambiguity. This structure elucidates the crucial role of ambiguity on optimal decisions, i.e., how it modulates the probability of selecting a given action.

DR-FREE not only returns the policy arising from our free energy principle, but also establishes its performance limits. In doing so, DR-FREE harbors two implications. First, DR-FREE policy is interpretable and supports (Bayesian) belief updating. The second implication is that it is impossible for an agent faced with ambiguity to outperform an ambiguity-free agent. As ambiguity vanishes, DR-FREE recovers the policy of an agent that has perfect knowledge of its environment, and no agent can obtain better performance. Vice-versa, as ambiguity increases, DR-FREE shows that the policy down-weights the model available to the agent over ambiguity.

We evaluate DR-FREE on an experimental testbed involving rovers, which are given the task of reaching a desired destination while avoiding obstacles. The trained model available to DR-FREE is learned from biased experimental data, which does not adequately capture the real environment and introduces ambiguity. In the experiments—even despite the ambiguity arising from having learned a model from biased data—DR-FREE successfully enables the rovers to complete their task, even in settings where both a state-of-the-art free energy minimizing agent and other methods struggle. The experiments results— confirmed by evaluating DR-FREE in a popular higher dimensional simulated environment—suggest that, to operate in open environments, agents require built-in robustness mechanisms, and these are crucial to compensate for poor training. DR-FREE, providing a mechanism that defines robustness in the problem formulation, delivers this capability.

Our free energy computational model, DR-FREE, reveals how free energy minimizing agents can compute optimal actions that are robust over an ambiguity set defined in the problem formulation. It establishes a normative framework to both empower the design of artificial agents built upon free energy models with robust decision-making abilities, and to understand natural behaviors beyond current free energy explanations33,34,35,36,37. Despite its success, there is no theory currently explaining if and how these free energy agents can compute actions in ambiguous settings. DR-FREE provides these explanations.

Results

DR-FREE

DR-FREE comprises a distributionally robust free energy principle and the accompanying resolution engine—the principle (Fig. 2a) is the problem statement for policy computation; the resolution engine is the method for policy computation. The principle establishes a sequential policy optimization framework, where randomized policies arise from the minimization of the maximum free energy over ambiguity. The resolution engine finds the solution in the space of policies. This is done by computing—via the maximum free energy over all possible environments in the ambiguity set—a cost associated to ambiguity. Then, the ensuing maximum free energy is minimized in policy space (Fig. 1d).

a Summarizing the distributionally robust free energy principle—the problem statement for policy computation. Our generalization of active inference yields an optimization framework where policies emerge by minimizing the maximum free energy over all possible environments in the ambiguity set, which formalizes the constraints in the problem formulation. The principle can accommodate environments that change over time. b The resolution engine to find the policy. Given the current state, the engine uses the generative model and the loss to find the maximum free energy \({D}_{KL}({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})| | {q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))+{{\mathbb{E}}}_{{p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})}[{\overline{c}}_{k}({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{k})]\) across all the environments in the ambiguity set. This yields the cost of ambiguity \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})+\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) that builds up the expected loss for the subsequent minimization problem. In this second problem, the variational free energy is minimized in the space of polices providing: (i) \({\pi }_{k}^{\star }({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\), the DR-FREE policy from which actions are sampled. Elements that guarantee robustness in green—these terms depend on ambiguity; (ii) the smallest free energy that the agent can achieve, i.e., the cost-to-go \({\overline{c}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})\) fed back to the maximization problem at the next time-step. For reactive actions, where N = 1, the cost-to-go equals the state cost given by the agent loss. c Using the generative model and the state-cost, DR-FREE first computes the cost of ambiguity, which is non-negative. This, together with the action cost, is then used to obtain the exponential kernel in the policy, i.e., \(\exp (-{c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})-{\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})-\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))\). After multiplication of the kernel with \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) and normalization, this returns \({\pi }_{k}^{\star }({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\).

In Fig. 1a, random variables Xk−1 and Uk are state at time k − 1 and action at k (see “Methods” and Section S3 of Supplementary Information). The agent infers the state of a stochastic environment \({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) and the action is sampled from \({\pi }_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\). In the decision horizon (e.g., from 1 to N), the agent-environment interactions are captured by p0:N, defined as \({p}_{0}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{0}){\prod }_{k=1}^{N}{p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}){\pi }_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\), where p0(x0) is an initial prior. The trained model available to the agent, \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\), does not (necessarily) match its environment, and the goal of DR-FREE is to compute a policy that, while optimal, is robust against the training/environment ambiguities. For example, if—as in our experiments—the robot model of Fig. 1a is learned from corrupted/biased data, then it differs from the real robot, and this gives rise to ambiguities. These ambiguities are captured via the ambiguity set of Fig. 1b. For a given state/action pair, this is the set of all possible environments with statistical complexity within \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) from the trained model. For this reason, the ambiguity set \({{{{\mathcal{B}}}}}_{\eta }({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))\) is captured via the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence: the ambiguity set is the set of all possible models, say \({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\), such that \({D}_{KL}({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})| | {\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))\le {\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). The radius of ambiguity available to DR-FREE, \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\), is positive and bounded. For a state/action pair, a small radius indicates low ambiguity, meaning that the agent is confident in its trained model. Vice-versa, high values indicate larger ambiguity and hence low confidence in the model. See “Methods” for the detailed definitions.

DR-FREE computes the optimal policy via a distributionally robust generalization of the free energy principle that accounts for ambiguities. This first component of DR-FREE, providing the problem statement for policy computation, generalizes the conventional free energy principle to ensure policies remain robust even when the environment deviates from the trained model. Our principle is formulated as follows: over the decision horizon, the optimal policy sequence \({\{{\pi }_{k}^{\star }({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\}}_{1:N}\) is obtained by minimizing over the policies the maximum free energy across all possible environments in the ambiguity set expected under the policy in question. The expected free energy combines two terms: (i) the statistical complexity, \({D}_{KL}({p}_{0:N}| | {q}_{0:N})\), of the agent-environment behavior from q0:N; (ii) the expected cumulative loss \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{{p}_{0:N}}\left[{\sum }_{k=1}^{N}({c}_{k}^{(x)}({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{k})+{c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{U}}}}}_{k}))\right]\). The principle is formalized in Fig. 2a (see Methods for details) as a distributionally robust policy optimization problem in the probability space. DR-FREE computes the policy via bi-level optimization, without requiring the environment \({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) and without performing stochastic sampling for the ambiguity set. The ambiguity set defines the problem constraints—these are nonlinear in the decision variable—and the min-max objective is the free energy—also nonlinear in the decision variables (see Section S2 in the Supplementary Information for connections with other frameworks). As also shown in Fig. 2a, the complexity term in the min-max objective regularizes the optimal policy to prevent environment-agent interactions that are overly complex with respect to q0:N. This is specified as \({q}_{0}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{0}){\prod }_{k=1}^{N}{q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}){q}_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\), with q0(x0) being a prior. Hence, the first term in the min-max objective biases the optimal solution of our robust principle—DR-FREE policy—towards q0:N. The second term in the objective minimizes the worst case expected loss across ambiguity. We refer to q0:N as generative model, although—for the application of our principle in Fig. 2a—this is not necessarily required to be a time-series model. For example, in some of our navigation experiments, q0:N only encodes the agent goal destination— in this case the complexity term in Fig. 2a encodes an error from the goal. In contrast, in a second set of experiments—where we relate DR-FREE to a state-of-the-art approach from the literature21,30—q0:N encodes a time-series model. Our formulation also allows for the generative model \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\)—provided to DR-FREE—to be different from the true environment \({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\)—not available to the agent—and the trained model \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\), see also Fig. 1a, b. This feature can be useful in applications where, by construction, the model available to the agent and the generative model differ24. Both reactive and planned behaviors can be seen through the lenses of our formulation: a width of the decision horizon N greater than 1 means that the policy at time-step k is computed as part of a plan. If N = 1, the agent action is reactive (or greedy). These actions frequently emerge as reflexive responses in biologically inspired motor control38,39. In brief, this generalization of active inference can be regarded as robust Bayesian model averaging to accommodate epistemic uncertainty about the environment, where the prior over models is supplied by the KL divergence between each model and the trained model. When there is no ambiguity, our robust principle in Fig. 2a connects with free energy minimization in active inference based upon expected free energy40—which itself generalizes schemes such as KL control and control as inference37,41,42,43. See “Methods” and Section S2 of Supplementary Information.

The policy optimization problem in Fig. 2a is infinite-dimensional as both minimization and maximization are in the space of probability densities. This enables a Bayes-optimal handling of uncertainty and ambiguity that characterizes control and planning as (active) inference. DR-FREE resolution engine—the method to compute the policy—finds the policy and returns a solution with a well-defined and explicit functional form. The analytical results behind the resolution engine are in Sections S3 and S6 of the Supplementary Information. In summary, the analytical results show that, at each k, the policy can be found via a bi-level optimization approach, first maximizing free energy across the ambiguity constraint and then minimizing over the policies. While the maximization problem is still infinite dimensional, its optimal value—yielding a cost of ambiguity—can be obtained by solving a scalar optimization problem. This scalar optimization problem is convex and has a global minimum. Therefore, once the cost of ambiguity is obtained, the resulting free energy can be minimized in the policy space, and the optimal policy is unique. These theoretical findings are summarized in Fig. 2b. Specifically, the policy at time-step k is a soft-max (Fig. 2b) obtained by equipping the generative model \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) with an exponential kernel. The kernel contains two costs: the action cost \({c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) and the cost of ambiguity, \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})+\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). Intuitively, given the cost-to-go \({\overline{c}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})\), the latter cost is the maximum free energy across all possible environments in the ambiguity set. The infinite dimensional free energy maximization step, which can be reduced to scalar convex optimization, yields a cost of ambiguity that is always bounded and non-negative (Fig. 2c and “Methods”). This implies that an agent always incurs a positive cost for ambiguity, and the higher this cost is for a given state/action pair, the lower the probability of sampling that action is. The result is that DR-FREE policy balances between the cost of ambiguity and the agent beliefs encoded in the generative model (Fig. 2c).

DR-FREE succeeds when ambiguity-unaware free energy minimizing agents fail

To evaluate DR-FREE we specifically considered an experiment where simplicity was a deliberate feature, ensuring that the effects of model ambiguity on decision-making could be identified, benchmarked against the literature32, and measured quantitatively. The experimentation platform (Fig. 3a) is the Robotarium44, providing both hardware and a high-fidelity simulator. The task is robot navigation: a rover needs to reach a goal destination while avoiding obstacles (Fig. 3b). In this set-up we demonstrate that an ambiguity-unaware free energy minimizing agent—even if it makes optimal actions—does not reliably complete the task, while DR-FREE succeeds. The ambiguity-unaware agent from the literature32 computes the optimal policy by solving a relaxation of the problem in Fig. 2a without ambiguity. This agent solves a policy computation problem—relevant across learning and control45— having DR-FREE objective but without ambiguity constraints. We performed several experiments: in each experiment, DR-FREE, used to compute reactive actions, only had access to a trained model \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) and did not know \({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). We trained off-line a Gaussian Process model, learned in stages. At each stage, data were obtained by applying randomly sampled actions to the robot, and a bias was purposely added to the robot positions (see Experiments settings in Methods for training details and Section S5 in Supplementary Information for the data), thus introducing ambiguity. The corrupted data from each stage was then used to learn a trained model via Gaussian Processes. Figure 3c shows the performance of DR-FREE at each stage of the training, compared to the performance of a free energy minimizing agent that makes optimal decisions but is ambiguity unaware. In the first set of experiments, when equipped with DR-FREE, the robot is always able to successfully complete the task (top panels in Fig. 3c): in all the experiments, the robot was able to reach the goal while avoiding the obstacles. In contrast, in the second set of experiments, when the robot computes reactive actions by minimizing the free energy—without using DR-FREE—it fails the task, crashing in the obstacles, except in trivial cases where the shortest path is obstacle-free (see Fig. 3c, bottom; details in “Methods”). The conclusion is confirmed when this ambiguity-unaware agent is equipped with planning capabilities. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3 for different widths of the planning horizon, the ambiguity-unaware agent still only fulfills the task when the shortest path is obstacle-free, confirming the findings shown in Fig. 3c, bottom. The experiments provide two key highlights. First, ambiguity alone can have a catastrophic impact on the agent and its surroundings. Second, DR-FREE enables agents to succeed in their task despite the very same ambiguity. This conclusion is also supported by experiments where DR-FREE is deployed on the Robotarium hardware. As shown in Fig. 3d, DR-FREE in fact enabled the robot provided by the Robotarium to navigate to the destination, effectively completing the task despite model ambiguity. The computation time measured on the Robotarium hardware experiments was of approximately 0.22 s (“Methods” for details). See “Data availability” for a recording; code also provided (see “Code availability”). Supplementary Fig. 4 presents results from a complementary set of experiments in the same domain but featuring different goal positions and obstacle configurations. The experiments confirm that, despite ambiguity, DR-FREE consistently enables the robot to complete the task across all tested environments (code also available).

a Unicycle robots (from the Robotarium) of 11cm × 8.5cm × 7.5cm (width, length, height) that need to achieve the goal destination, xd, avoiding obstacles. The Robotarium work area is 3m × 2m, the robot position is the state, and actions are vertical/horizontal speeds; \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) is a Gaussian centered in xd and \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) is uniform. See Methods for the settings. b The non-convex state cost for the navigation task. See Methods for the expression. c Comparison between DR-FREE and a free-energy minimizing agent that makes optimal decisions but is unaware of the ambiguity. DR-FREE enables the robot to successfully complete the task at each training stage. The ambiguity-unaware agent fails, except when the shortest path is obstacle-free. Training details are in “Methods”. d Screenshots from Supplementary Movie 1. This is from the Robotarium platform. DR-FREE allows the robot (starting top-right) to complete the task (trained model from stage 3 used). e How DR-FREE policy changes as a function of ambiguity. By increasing the radius of ambiguity by 50%, DR-FREE policy (left) becomes a policy dominated by ambiguity (right). As a result, actions with low ambiguity are assigned higher probability. Screenshot of the robot policy when this is in position [0.2, 0.9], i.e., near the middle obstacle. The ambiguity increase deterministically drives the robot bottom-left (note the higher probability) regardless of the presence of the obstacle. f Belief update. Speeds/positions from the top-right experiments in (c) are used together with F = 16 state/action features, \({\varphi }_{i}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})={{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})}[{\phi }_{i}({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{k})]\) in Supplementary Fig. 1b. Once the optimal weights, \({w}_{i}^{\star }\), are obtained, the reconstructed cost is \(-{E}_{{\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})}[{\sum }_{i=1}^{16}{w}_{i}^{\star }{\phi }_{i}({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{k})]\). Since this lives in a 4-dimensional space, we show \(-{\sum }_{i=1}^{16}{w}_{i}^{\star }{\phi }_{i}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})\), which can be conveniently plotted.

DR-FREE elucidates the mechanistic role of ambiguity on optimal decision making

DR-FREE policy (Fig. 2b) assigns lower probabilities to states and actions associated with higher ambiguity. In simpler terms, an agent that follows DR-FREE policy is more likely to select actions and states associated with lower ambiguity. DR-FREE yields a characterization of the agent behavior in regimes of small and large ambiguity. Intuitively, as ambiguity increases, DR-FREE yields a policy dominated by the agent’s generative model and radius of ambiguity. In essence, as ambiguity increases, DR-FREE implies that the agent grounds decisions on priors and ambiguity, reflecting its lack of confidence. Conversely, when the agent is confident about its trained model, DR-FREE returns the policy of a free energy minimizing agent making optimal decisions in a well-understood, ambiguity-free, environment.

Characterizing optimal decisions in the regime of large ambiguity amounts at studying DR-FREE policy (Fig. 2b) as \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) increases. More precisely, this means studying what happens when \({\eta }_{\min }=\min {\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) increases. Since \(\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) and \({c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) are non-negative, and since \(\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) does not depend on \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) for sufficiently large \({\eta }_{\min }\), this means that, when \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) is large enough, \(\exp (-{\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})-\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})-{c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))\approx \exp (-{\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))\) in DR-FREE policy (derivations in Supplementary Information). Therefore, as ambiguity increases, \({\pi }_{k}^{\star }({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) only depends on the generative model and the ambiguity radius. Essentially, DR-FREE shows that, when an agent is very unsure about its environment, optimal decisions are dominated by the generative model and the radius of ambiguity. In our experiments, an implication of this is that with larger \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) the robot may sacrifice physical risk (obstacle avoidance) in favor of epistemic risk (avoiding model mismatch). Hence, an interesting but not usual outcome is that risk-averse is not equal to obstacle-avoidance especially when model uncertainty is not evenly distributed. This behavior is clearly evidenced in our experiments. As shown in Fig. 3e, as ambiguity increases, the agent’s policy becomes dominated by ambiguity. As a result, it deterministically directs the robot towards the goal position—associated to the lowest ambiguity—disregarding the presence of obstacles. At the time-step captured in the figure, the robot was to the right of the middle obstacle. Consequently, while DR-FREE policy with the original ambiguity radius would assign higher probabilities to speeds that drive the robot towards the bottom of the work-area, when ambiguity increases the robot is instead directed bottom-left, and this engenders a behavior that makes the robot crash in the obstacle.

Conversely, to characterize the DR-FREE policy in the regimes of low ambiguity, we need to study how the policy changes as \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) shrinks. As \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\to 0\), the ambiguity constraint is relaxed, and \(\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) simply becomes \({D}_{KL}({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})| | {q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))+{{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})}[{\overline{c}}_{k}({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{k})]\). See Supplementary Information for the derivations. This yields the optimal policy from the literature32. The minimum free energy attained by this policy when there is no ambiguity is always smaller than the free energy achieved by an agent affected by ambiguity. Hence, DR-FREE shows that ambiguity cannot be exploited by a free energy minimizing agent to obtain a better cost. See “Methods” for further discussion. Supplementary Fig. 5 shows experiments results for different ambiguity radii. Experiments confirm that, due to the presence of ambiguity, when the radius is set to zero the agent—now ambiguity unaware—does not always complete the task. Additionally, we conduct a second set of experiments in which the trained model \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) coincides with \({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). This scenario remains stochastic but no longer features ambiguity. The results (Supplementary Fig. 6) show that—unlike in the previous experiments—DR-FREE enables the robot to complete the task even when the ambiguity radius is set to 0. This outcome is consistent with our analysis: when there is no ambiguity, the KL divergence between \({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) and \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) is identically zero and DR-FREE therefore succeeds even for a zero ambiguity radius. We provide the code to replicate the results (see Code Availability).

DR-FREE supports Bayesian belief updating

DR-FREE policy associates higher probabilities to actions for which the combined action and ambiguity cost \({c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})+{\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})+\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) is lower. This means that the reason why an action is observed can be understood by estimating this combined cost: DR-FREE supports a systematic framework to achieve this. Given a sequence of observed states/actions, (\({\widehat{{{{\bf{x}}}}}}_{k-1}\), \({\widehat{{{{\bf{u}}}}}}_{k}\)), and the generative policy \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\), the combined cost can be estimated by minimizing the negative log-likelihood. The resulting optimization problem is convex if a widely adopted (see Methods) linear parametrization of the cost in terms of known (and arbitrary) features is available. Given F state/action features and G action features, this parametrization is \({\sum }_{i=1}^{F}{w}_{i}{\varphi }_{i}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})+{\sum }_{i=1}^{G}{v}_{i}{\gamma }_{i}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). Reconstructing the cost then amounts at finding the optimal weights that minimize the negative log-likelihood, with likelihood function being \({\prod }_{k=1}^{M}{p}_{k}^{\star }({\widehat{{{{\bf{u}}}}}}_{k}| {\widehat{{{{\bf{x}}}}}}_{k-1};{{{\bf{v}}}},{{{\bf{w}}}})\). Here, M is the number of observed state/inputs pairs, and \({p}_{k}^{\star }({\widehat{{{{\bf{u}}}}}}_{k}| {\widehat{{{{\bf{x}}}}}}_{k-1};{{{\bf{v}}}},{{{\bf{w}}}})\) is, following the literature32, the DR-FREE policy itself, but with \(-{c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})-{\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})-\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) replaced by the linear parametrization (v and w are the stacks of the parametrization weights). We unpack the resulting optimization problem in the “Methods”. This convenient implication of DR-FREE policy allows one to reconstruct the cost driving the actions of the rovers using DR-FREE in our experiments, and Fig. 3f shows the outcome of this process. The similarity with Fig. 3b is striking, and to further assess the effectiveness of the reconstructed cost we carried out a number of additional experiments. In these experiments, the robots are equipped with DR-FREE policy but, crucially, \(-{c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})-{\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})-\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) is replaced with the reconstructed cost. The outcome from these experiments confirms the effectiveness of the results: as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1d, the robots are again able to fulfill their goal, despite ambiguity. Additionally, we also benchmarked our reconstruction result with other state-of-the-art approaches. Specifically, we use an algorithm from the literature that, building on maximum entropy46, is most related to our approach47. This algorithm makes use of Monte Carlo sampling and soft-value iteration. When using this algorithm—after benchmarking it on simpler problems—we observed that it would not converge to a reasonable estimate of the robot cost (see Supplementary Fig. 1e for the reconstructed cost using this approach and the Methods for details). Since our proposed approach leads to a convex optimization problem, our cost reconstruction results could be implemented via off-the-shelf software tools. The code for the implementation is provided (see “Code availability”).

Relaxing ambiguity yields maximum diffusion

Maximum diffusion (MaxDiff) is a policy computation framework that generalizes maximum entropy (MaxEnt) and inherits its robustness properties. It outperforms other state-of-the-art methods across popular benchmarks21,30. We show that the distributionally robust free energy principle (Fig. 2a) can recover, with a proper choice of q0:N, the MaxDiff objective when ambiguity is relaxed. This explicitly connects DR-FREE to MaxDiff and—through it—to a broader literature on robust decision-making (Section S2 of Supplementary Information). In MaxEnt—and MaxDiff—robustness guarantees stem from the entropy of the optimal policy31, with explicit a-posteriori bounds on the ambiguity set over which the policy guarantees robustness available for discrete settings and featuring a constant radius of ambiguity31 (Lemma 4.3). To compute policies that robustly maximize a reward, MaxEnt is used with an auxiliary, pessimistic, reward31. In contrast, by tackling the problem in Fig. 2a, DR-FREE defines robustness guarantees directly in the problem formulation, explicitly via the ambiguity set. As a result, DR-FREE policy is guaranteed to be robust across this ambiguity set. As detailed in Section S2 of Supplementary Information, DR-FREE tackles the full min-max problem in Fig. 2a—featuring at the same time a free energy objective and distributionally robust constraints—that remains a challenge for many methods10,21,30,31. This is not just a theoretical achievement—we explore its implications by revisiting our robot navigation task: we equip DR-FREE with a generative model that recovers MaxDiff objective and compare their performance. The experiments reveal that DR-FREE succeeds in settings where MaxDiff struggles. This is because DR-FREE not only retains the desirable properties of MaxDiff, but also guarantees them in the worst case over the ambiguity set.

In MaxDiff, given some initial state x0, policy computation is framed as minimizing in the policy space \({D}_{KL}({p}_{0:N}| | {p}_{\max }({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{0:N},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{1:N}))\). This is the KL divergence between (using the time-indexing and notation in Fig. 2a for consistency) p0:N and \({p}_{\max }({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{0:N},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{1:N})=\frac{1}{Z}{\prod }_{k=1}^{N}{p}_{\max }({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\exp (r({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))\). In this last expression, r(xk, uk) is the state/action reward when the agent transitions in state xk under action uk, Z is the normalizer, and \({p}_{\max }({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) is the maximum entropy sample path probability21. On the other hand, the distributionally robust free energy principle (Fig. 2a) is equivalent to

in the sense that the optimal solution of (1) is the same as the optimal solution of the problem in Fig. 2a (see Methods). In the above expression, \({\widetilde{q}}_{0:N}=\frac{1}{Z}{q}_{0:N}\exp (-{\sum }_{k=1}^{N}({c}_{k}^{(x)}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})+{c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})))\) and Z is again a normalizer. When there is no ambiguity, the optimization problem in (1) is relaxed and it becomes

Given an initial state x0, as we unpack in the Methods, this problem has the same optimal solution as the MaxDiff objective when the reward is \(-{c}_{k}^{(x)}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})-{c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) and in the DR-FREE generative model—which we recall is defined as \({q}_{0}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{0}){\prod }_{k=1}^{N}{q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}){q}_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\)—we set \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) to be the maximum entropy sample path probability and \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) to be uniform.

The above derivations show that relaxing ambiguity in DR-FREE yields, with a properly defined q0:N, the MaxDiff objective—provided that the rewards are the same. This means that, in this setting, DR-FREE guarantees the desirable MaxDiff properties in the worst case, over \({{{{\mathcal{B}}}}}_{\eta }({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))\). To evaluate the implications of this finding, we revisit the robot navigation task. We equip DR-FREE with q0:N defined as described above, in accordance with MaxDiff, and compare DR-FREE with MaxDiff itself. In the experiments, the cost is again the one of Fig. 3b and again the agents have access to \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). Initial conditions are the same as in Fig. 3c. Given this setting, Fig. 4a summarizes the success rates of MaxDiff—i.e., the number of times the agent successfully reaches the goal—for different values of key hyperparameters21: samples and horizon, used to compute the maximum entropy sample path probability. The figure shows a sweetspot where 100% success rate is achieved, yielding two key insights. First, increasing samples increases the success rate. Second—and rather counter-intuitively—planning horizons that are too long yield a decrease in the success rate, and this might be an effect of planning under a wrong model. Worst performance is obtained with horizon set to 2, and Fig. 4b confirms that the success rates remain consistent when an additional temperature-like21 hyperparameter is changed. Given this analysis, to compare DR-FREE with MaxDiff, we equip DR-FREE with the generative model computed in accordance with MaxDiff (with horizon set to 2 and samples to 50). In this setting, MaxDiff successfully completes the task when the shortest path between the robot initial position and the goal is obstacle free (Fig. 4c). In contrast, in this very same setting, the experiments show that DR-FREE—computing reactive actions—allows the robot to consistently complete its task (Fig. 4d). This desirable behavior is confirmed when samples is decreased to 10 (Fig. 4e). Experiments details are reported in Methods (Experiments settings) and Supplementary Information (Section S6 and Table S-1). See also “Code availability”.

a MaxDiff success rates for different values of the sampling size and planning horizon. Experiments highlight a sweetspot in the hyperparameters with 100% success rate. Worst rates are obtained for low horizons, where the success rate is between 25% and approximately 40%. All experiments are performed with the temperature-like hyperparameter α set to 0.1. Data for each cells obtained from 12 experiments corresponding to the initial conditions in Fig. 3c. b Success rates for different values of α and samples when horizon is set to 2. Success rates are consistent with the previous panel—for the best combination of parameters, MaxDiff agent completes the task half of the times. See Supplementary Fig. 7 for a complementary set of MaxDiff experiments. c Robot trajectories using the MaxDiff policy when the horizon is equal to 2 and samples is set to 50. MaxDiff fulfills the task when the shortest path is obstacle-free. d DR-FREE allows the robot to complete the task when it is equipped with a generative model from MaxDiff computed using the same set of hyperparameters from the previous panel. e This desirable behavior is confirmed even when samples is decreased to 10. See “Methods” and Supplementary Information for details.

Finally, we evaluate DR-FREE in the MuJoCo48 Ant environment (Fig. 5a). The goal is for the quadruped agent to move forward along the x-axis while maintaining an upright posture. Each episode lasts 1000 steps, unless the Ant becomes unhealthy— a terminal condition defined in the standard environment that indicates failure. We compare DR-FREE with all previously considered methods, as well as with model-predictive path integral control49 (NN-MPPI). Across all experiments, the agents have access to the trained model \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) and not to \({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). The trained model was obtained using the same neural network architecture as in the original MaxDiff paper21, which also included benchmarks with NN-MPPI. The cost provided to the agents is the same across all the experiments and corresponds to the negative reward defined by the standard environment. Figure 5b shows the experimental results for this setting. The experiments yield two main observations. First, DR-FREE outperforms all comparison methods on average, and even the highest error bars (standard deviations from the mean) of the other methods do not surpass DR-FREE average return. Second, in some of the trials, the other methods would terminate prematurely the episode due to the Ant becoming unhealthy. In contrast, across all DR-FREE experiments, the Ant is always kept healthy and therefore episodes do not terminate prematurely. See Experiments Settings in “Methods” and Supplementary Information for details; code also provided.

a Screenshot from the MuJoCo environment (Ant v-3). The state space is 29-dimensional and the action space is 8-dimensional. b Performance comparison. Charts show means and bars standard deviations from the means across 30 experiments. In some episodes, the ambiguity unaware, MaxDiff and NN-MPPI agents terminate prematurely due to the Ant becoming unhealthy; rewards were set to zero from that point to the end of the episode. The Ant becomes unhealthy in 6% of the episodes for the ambiguity unaware agent, 20% for MaxDiff, and 23% for NN-MPPI. In contrast, the Ant remains healthy in all DR-FREE experiments. As in previous experiments, DR-FREE is used to compute reactive actions. The ambiguity-unaware policy32 corresponds to DR-FREE with the ambiguity radius set to zero.

Discussion

Robustness is a core requirement for intelligent agents that need to operate in the real world. Rather than leaving its fulfillment to – quoting the literature50 – an emergent and potentially brittle property from training, DR-FREE ensures this core requirement by design, building on the minimization of the free energy and installing sequential policy optimization into a rigorous (variational or Bayesian) framework. DR-FREE provides not only a free energy principle that accounts for environmental ambiguity, but also the resolution engine to address the resulting sequential policy optimization framework. This milestone is important because addresses a challenge for intelligent machines operating in open-worlds. In doing so, DR-FREE elucidates the mechanistic role of ambiguity on optimal decisions and its policy supports (Bayesian) belief-based updates. DR-FREE establishes what are the limits of performance in the face of ambiguity, showing that, at a very fundamental level, it is impossible for an agent affected by ambiguity to outperform an ambiguity-free free energy minimizing agent. These analytic results are confirmed by our experiments.

In the navigation experiments, we compared the behaviors of an ambiguity-unaware free energy minimizing agent32 with the behavior of an agent equipped with DR-FREE. All the experiments show that DR-FREE is essential for the robot to successfully complete the task amid ambiguity, and this is confirmed when we consider additional benchmarks and different environments. DR-FREE enables to reconstruct the cost functions that underwrote superior performance over related methods. Our experimental setting is exemplary not only for intelligent machines, underscoring the severe consequences of ambiguity, but also for natural intelligence. For example, through evolutionary adaptation, bacteria can navigate unknown environments, and this crucial ability for survival is achieved with little or no training. DR-FREE suggests that this may be possible if bacteria follow a decision-making strategy that, while simple, foresees a robustness promoting step. Run-and-tumble motions51,52 might be an astute way to achieve this: interpreted through DR-FREE, tumbles might be driven by free energy maximization, needed to quantify across the environment a cost of ambiguity, and runs would be sampled from a free-energy minimizing policy that considers this cost.

DR-FREE offers a model for robust decision making via free energy minimization, with robustness guarantees defined in the problem formulation—it also opens a number of interdisciplinary research questions. First, our results suggest that a promising research direction originating from this work is to integrate DR-FREE with perception and learning, coupling training with policy computation. This framework would embed distributional constraints in the formulation of the policy computation problem, as in DR-FREE, while retaining perception and learning mechanisms inspired by, for example, MaxDiff and/or evidence free energy minimization. The framework would motivate analytical studies to quantify the benefits of integrated learning over an offline pipeline. Along these lines, analytical studies should be developed to extend our framework so that it can explicitly account for ambiguities in the agent cost/reward. Second, DR-FREE takes as input the ambiguity radius, and this motivates the derivation of a radius estimation mechanism within our model. Through our analytic results, we know that reducing ambiguity improves performance; hence, integrating in our framework a method to learn ambiguity would be a promising step towards agents that are not only robust, but also antifragile53. Finally, our experiments prompt a broader question: what makes for a good generative model/planning horizon in the presence of ambiguity? The answer remains elusive—DR-FREE guarantees robustness against ambiguity, and experiments suggest that it compensates for poor planning/models; however, with other, better-tuned (e.g., more task-oriented) models/planning, ambiguity-unaware agents could succeed. This yields a follow-up question. In challenging environments, is a model tuned for a task better than a multi-purpose one for survival?

If, quoting the popular aphorism, all models are wrong, but some are useful, then relaxing the requirements on training, DR-FREE makes more models useful. This is achieved by departing from views that emphasize the role and the importance of training: in DR-FREE the emphasis is instead on rigorously installing robustness into decision-making mechanisms. With its robust free energy minimization principle and resolution engine, DR-FREE suggests that, following this path, intelligent machines can recover robust policies from largely imperfect, or even poor, models. We hope that this work may inspire both the deployment of our free energy model in multi-agent settings (with heterogeneous agents such as drones, autonomous vessels, and humans) across a broad range of application domains and, combining DR-FREE with Deep RL, lead to learning schemes that—learning ambiguity—succeed when classic methods fail. At a perhaps deeper level—as ambiguity is a key theme (see also Section S7 in Supplementary Information) across, e.g., psychology, economics and neuroscience54,55,56—we hope that this work may provide the foundation for a biologically plausible neural explanation of how natural agents—with little or no training—can operate robustly in challenging environments.

Methods

The agent has access to: (i) the generative model, q0:N; (ii) the loss, specified via state/action costs \({c}_{k}^{(x)}:{{{\mathcal{X}}}}\to {\mathbb{R}}\), \({c}_{k}^{(u)}:{{{\mathcal{U}}}}\to {\mathbb{R}}\), with \({{{\mathcal{X}}}}\) and \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}\) being the state and action spaces (see Sec. S1 and Sec. S3 of the Supplementary Information for notation and details); (iii) the trained model \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\).

Distributionally robust free energy principle

Model ambiguities are specified via the ambiguity set around \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\), i.e., \({{{{\mathcal{B}}}}}_{\eta }({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))\). This is the set of all models with statistical complexity of at most \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) from \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). Formally, \({{{{\mathcal{B}}}}}_{\eta }({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))\) is defined as the set

The symbol \({{{\mathcal{D}}}}\) stands for the space of densities and supp for the support. The ambiguity set captures all the models that have statistical complexity of at most \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) from the trained model and that have a support included in the generative model. This second property, explicitly built in the ambiguity set makes the optimization meaningful as violation of the property would make the optimal free energy infinite. The radius \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) is positive and bounded. As summarized in Fig. 2a, the principle in the main text yields the following sequential policy optimization framework, where we highlight that the environment can change over time:

This is an extension of the free energy principle27 accounting for policy robustness against model ambiguities. When the ambiguity constraint is removed our formulation links to the expected free energy minimization in active inference. In this special case, the expected complexity (i.e., ambiguity cost) becomes risk; namely, the KL divergence between inferred and preferred (i.e., trained) outcomes. The expected free energy can be expressed as risk plus ambiguity; however, the ambiguity in the expected free energy pertains to the ambiguity of likelihood mappings in the generative model (i.e., conditional entropy), not ambiguity about the generative model considered in our free energy model. In both robust and conventional active inference, the complexity term establishes a close relationship between optimal control and Jaynes’ maximum caliber (a.k.a., path entropy) or minimum entropy production principle57,58. It is useful to note that, offering a generalization to free energy minimization in active inference, our robust formulation yields as special cases other popular computational models such as KL control59, control as inference41, and the Linear Quadratic Gaussian Regulator. Additionally, in special cases the negative of the variational free energy in the cost functional is the evidence lower bound60, a key concept in machine learning and inverse reinforcement learning46. With its resolution engine, DR-FREE shows that in this very broad set-up the optimal policy can still be computed.

Drawing the connection between MaxDiff and DR-FREE

We start with showing that the robust free energy principle formulation in Fig. 2a has the same optimal solution as (1). We have the following identity:

The left hand-side is the objective of Fig. 2a. In the right-hand side, \({\widetilde{q}}_{0:N}\) is given in the main text and \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{{q}_{0:N}}[\exp (-{\sum }_{k=1}^{N}({c}_{k}^{(x)}({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{k})+{c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{U}}}}}_{k})))]\) is the normalizing constant denoted by Z in the main text. The last term in the right-hand side does not depend on the decision variables, and this yields that the min-max problem in Fig. 2a has the same optimal solution as (1). Next, we show why—with the choice of q0:N described in the main text—DR-FREE yields the MaxDiff objective when there is no ambiguity. In this case, the ambiguity constraint is relaxed and DR-FREE min-max problem becomes

This is the problem given in (2) but with \({\widetilde{q}}_{0:N}\) explicitly included in the objective functional. To establish the connection between MaxDiff and DR-FREE we recall that the MaxDiff objective consists in minimizing in the policy space the KL divergence between p0:N and \({p}_{\max }({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{0:N},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{1:N})\), which can be conveniently written as \(\frac{1}{Z}{\prod }_{k=1}^{N}({p}_{\max }({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1}))\exp ({\sum }_{k=1}^{N}r({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))\). Now, this minimization problem has the same optimal solution of

when \(\overline{p}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{{{{k}}}}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) is uniform. The equivalence can be shown by noticing that this reformulation has been obtained by adding and subtracting the constant quantity \({{\mathrm{ln}}}{\prod }_{k=1}^{N}\overline{p}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{{{{k}}}}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) to the MaxDiff cost functional. The similarity between (4) and (3) is striking. In particular, the two problems are the same when: (i) x0 is given, (ii) in q0:N —which we recall is defined as \(p({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{0}){\prod }_{k=1}^{N}{q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}){q}_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) —we have \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) set to \({p}_{\max }({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) and \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) uniform; (iii) \(r({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})=-{c}_{k}^{(x)}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})-{c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). This establishes the connection between DR-FREE and MaxDiff objective from the Results.

Resolution engine

Both the variational free energy and the ambiguity constraint are nonlinear in the infinite-dimensional decision variables, and this poses a number of challenges that are addressed with our resolution engine. The resolution engine allows to tackle the sequential policy optimization framework arising from our robust free energy principle. We detail here the resolution engine and refer to Supplementary Information for the formal treatment. Our starting point is the robust free energy principle. This can be solved via a backward recursion where, starting from k = N, at each k the following optimization problem needs to be solved:

In the above expression, for compactness we used the shorthand notations \({\pi }_{k| k-1}^{(u)}\), \({q}_{k| k-1}^{(u)}\), \({p}_{k| k-1}^{(x)}\) and \({q}_{k| k-1}^{(x)}\) for \({\pi }_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\), \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\), \({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) and \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\), respectively. The term \({\overline{c}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})\) is the cost-to-go. This is given by \({\overline{c}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})={c}_{k}^{(x)}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})+{\widehat{c}}_{k+1}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})\), where \({\widehat{c}}_{k+1}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})\) is the smallest free energy that can be achieved by the agent at k + 1. That is, \({\widehat{c}}_{k+1}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})\) is the optimal solution of the above optimization problem evaluated at k + 1. When k = N, \({\widehat{c}}_{N+1}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{N})\) is initialized at 0. This means that, for reactive actions, e.g., reflexes, \({\overline{c}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})={c}_{k}^{(x)}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})\). The above reformulation is convenient because it reveals that, at each k, \({\pi }_{k}^{\star }({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) can be computed via a bi-level optimization approach, consisting in first maximizing over \({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\), obtaining the maximum expected variational free energy across all possible environments in the ambiguity set, to finally minimize over the policies. Crucially, this means that to make optimal decisions, the agent does not need to know the environment that maximizes the free energy but rather it only needs to know what the actual maximum free energy is. In turn, this can be found by first tackling the problem in green in Fig. 2b, i.e., finding the cost of ambiguity, and then taking the expectation \({{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\pi }_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})}[\cdot ]\). While the problem in green in Fig. 2b is infinite-dimensional, DR-FREE finds the cost of uncertainty by solving a convex and scalar optimization problem. This is possible because the optimal value of the problem in green in Fig. 2b equals \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})+{\min }_{\alpha \ge 0}{\widetilde{V}}_{\alpha }({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). In this expression, α is a scalar decision variable and \({\widetilde{V}}_{\alpha }({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\), detailed in the Supplementary Information, is a scalar function of α, convex for all α ≥ 0. The global non-negative minimum of \({\widetilde{V}}_{\alpha }({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) is \(\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). In summary, the free energy maximization step can be conveniently solved with off-the-shelf software tools. In DR-FREE, the cost of ambiguity promotes robustness and contributes to the expected loss for the subsequent minimization problem in Fig. 2b. The optimal solution of this class of problems has an explicit expression (\({\pi }_{k}^{\star }({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) in Fig. 2b) and the optimal value is \({\widehat{c}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) used at the next step in the recursion. Derivations in Supplementary Information.

Why is it always better to be ambiguity-aware

As ambiguity vanishes, \(\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) becomes \({D}_{KL}({\overline{p}}_{k| k-1}^{(x)}| | {q}_{k| k-1}^{(x)})+{{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\overline{p}}_{k| k-1}^{(x)}}[{\overline{c}}_{k}({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{k})]\). Thus, the DR-FREE policy becomes

This is the optimal policy of an ambiguity-free agent32 (with \({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})={\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\)). Given the current state xk−1, the optimal cost is

This is smaller than the cost achieved by the agent affected by ambiguity. In fact, when there is ambiguity, the DR-FREE policy achieves the optimal cost \(-{{\mathrm{ln}}}\int \,{q}_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\exp (-{\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})-\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})-{c}_{k}^{(u)}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})) d{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}\) and \({D}_{KL}({\overline{p}}_{k| k-1}^{(x)}| | {q}_{k| k-1}^{(x)})+{{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\overline{p}}_{k| k-1}^{(x)}}[{c}_{k}^{(x)}({{{{\bf{X}}}}}_{k})] < {\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})+\widetilde{c}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). See Sec. S4 in the Supplementary Information for the formal details.

Why DR-FREE supports Bayesian belief updating

The approach adopts a widely used parametrization32,46,61,62 of the cost in terms of F state-action features, φi(xk−1, uk), and G action features, γi(uk). No assumptions are made on the features, which can be, e.g., nonlinear. With this parametrization, given M observed actions/state pairs, the likelihood function—inspired by the literature32,62—is

where w and v are the stacks of the weights wi and vi, respectively. The negative log-likelihood32,62 is then given by

The cost reconstruction in the main paper is then obtained by finding the weights that are optimal for the problem \({\min }_{{{{\bf{w}}}},{{{\bf{v}}}}}-L({{{\bf{w}}}},{{{\bf{v}}}})\), after dropping the first term from the cost because it does not depend on the weights. Convexity of the problem follows because32,62 the cost functional is a conical combination of convex functions. See Supplementary Information.

Experiments settings

DR-FREE was turned into Algorithm 1 shown in the Supplementary Information and engineered to be deployed on the agents (see Code Availability). In the robot experiments \({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) is \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1}+{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}dt,\Sigma )\) with \({{{\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}}}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}0.001 & 0.0002\\ 0.0002 & 0.001\end{array}\right]\), and where \({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}={[{p}_{x,k},{p}_{y,k}]}^{T}\) is the position of the robot at time-step k, \({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}={[{v}_{x,k},{v}_{y,k}]}^{T}\) is the input velocity vector, and dt = 0.033s is the Robotarium time-step. In these experiments, the state space is [−1.5, 1.5] × [−1, 1] m, matching the work area, and the action space is [−0.5, 0.5] × [−0.5, 0.5] m/s. In accordance with the maximum allowed speed in the platform, the inputs to the robot were automatically clipped by the Robotarium when the speed was higher than 0.2 m/s. DR-FREE does not have access to \({p}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\). Its trained model, \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\), is learned via Gaussian Processes (GPs) with covariance function being an exponential kernel. The trained model was learned in stages, and the model learned in a given stage would also use the data from the previous stages. The data for the training had a bias: the input uk was sampled from a uniform policy, and the next observed robot position was corrupted by adding a quantity proportional to the current position (0.1xk−1). See Supplementary Information for the details and the data used for training. This means that the models learned at each stage of the training data were necessarily wrong: the parameters of the trained model at each stage of the training are in Supplementary Fig. 1a. For the generative model, \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})={{{\mathcal{N}}}}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{d},{\Sigma }_{{{{\bf{x}}}}})\), with Σx = 0.0001I2, and \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) being the uniform distribution. Also, the ambiguity radius, \({\eta }_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})={D}_{KL}({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})| | {\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))\) and clipped at 100, is higher the farther the robot is from the goal position (we recall that the agent has access to both \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) and \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\)). This captures higher agent confidence as it gets closer to its goal destination (see Supplementary Fig. 2, also reporting the number of steps recorded across the experiments). The state cost in Fig. 3b, adapted from the literature32, is \(c({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})=50{({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}-{{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{d})}^{2}+20{\sum }_{i=1}^{n} \, {g}_{i}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})+5b({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})\), where: (i) xd is the goal destination, and thus this term promotes goal-reaching; (ii) n = 6, gi are Gaussians, \({{{\mathcal{N}}}}({{{{\bf{o}}}}}_{i},{\Sigma }_{o})\), with Σo = 0.025I2 (I2 is the identity matrix of dimension 2). The oi’s are in Supplementary Fig. 1c) and capture the presence of the obstacles. Hence, the second term penalizes proximity to obstacles; (iii) b(xk) is the boundary penalty term given by \(b({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}):={\sum }_{j=1}^{2}\left(\exp \left(-0.5{\left(\frac{{p}_{x,k}-{b}_{{x}_{j}}}{\sigma }\right)}^{2}\right)+\exp \right.\left.\left(-0.5{\left(\frac{{p}_{y,k}-{b}_{{y}_{j}}}{\sigma }\right)}^{2}\right)\right)/\sigma \sqrt{2\pi }\), with \({b}_{{x}_{j}}\), \({b}_{{y}_{j}}\) representing the jth component of the boundary coordinates (bx = [−1.5, 1.5], by = [−1, 1]) and σ = 0.02. In summary, the cost embeds obstacle avoidance in the formulation. The optimal policy of the ambiguity-unaware free energy minimizing agent is available in the literature32. This is again exponential but, contrary to DR-FREE policy in Fig. 3b, the exponent is now \(-{D}_{KL}({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})| | {q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}))-{{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})}[{c}_{k}^{(x)}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k})]\). Across experiments, the first term dominated the second, which accounted for obstacles (see Supplementary Information for details). As a result, the policy consistently directs the robot along the shortest path to the goal, disregarding the presence of the obstacles. This explains the behavior observed in Fig. 3c. The computation time reported in the main text was obtained from DR-FREE deployment on the Robotarium hardware—measurements obtained using the time() function in Python and averaging across the experiment.

The benchmark for our belief updating is with respect to the Infinite Horizon Maximum Causal Entropy Inverse RL algorithm with Monte-Carlo policy evaluation and soft-value iteration (not required in DR-FREE belief update) from the literature47. In order to use this algorithm, we discretized the state space in a 50 × 50 grid (this step is not required within our results) and we needed to redefine the action space as [−1.0, 1.0] × [−1.0, 1.0]. This was then discretized into a 5 × 5 grid. The corresponding reconstructed cost in Supplementary Fig. 1e was obtained with the same dataset and features used to obtain Fig. 3f. After multiple trials and trying different settings, we were not able to obtain a reconstructed cost that was better than the one in Supplementary Fig. 1e. The settings used to obtain Supplementary Fig. 1e are: (i) initial learning rate of 1, with an exponential decay function to update the learning rate after each iteration; (ii) discount factor for soft-value iteration, 0.9; (iii) initial feature weights randomly selected from a uniform distribution with support [−100, 100]; (iv) gradient descent stopping threshold, 0.01. The code to replicate all the results is provided (see “Code availability”). For the comparison with MaxDiff21 we used the code available on the paper repository. In the experiments reported in Fig. 4, consistently with all the other experiments, MaxDiff had access to \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) and cost/reward from Fig. 3b. In the experiments of the Supplementary Fig. 7b, MaxDiff learns both the reward and the model. In this case, the data used by MaxDiff is corrupted by the same bias as the data used by DR-FREE (100000 data points are used for learning, consistently with the original MaxDiff repository). Across all MaxDiff experiments, again consistently with the original code, the additional MaxDiff hyperparameters are γ = 0.95, λ = 0.5, and learning rate 0.0005 (this last parameter is used only in the experiments where MaxDiff does not have access to the reward/model). No changes to the original MaxDiff code were made to obtain the results. The available MaxDiff implementation natively allows users to configure if the framework uses reward/model supplied by the environment. These details, together with a table summarizing all the parameter settings used in the experiments, are given in the Supplementary Information (see at the end of Section S5 and Table S-1). For the experiments of Fig. 5, the Ant becomes unhealthy when either the value of any of the states is no longer finite or the height of the torso is too low/high (we refer to the environment documentation at https://gymnasium.farama.org/environments/mujoco/ant/ for the standard definition of the unhealthy condition). The cost is the negative reward provided by the environment, and the trained model \({\overline{p}}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) is learned from 10,000 data points collected through random policy rollouts, using the same neural network as in the Ant experiments in the MaxDiff paper21. The same network—providing as output mean and variance—is used across all the experiments. For the DR-FREE generative model, \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1})\) is uniform, and \({q}_{k}({{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k}| {{{{\bf{x}}}}}_{k-1},{{{{\bf{u}}}}}_{k})\) is set as an anisotropic Gaussian having the same mean provided by the neural network but with a different variance. The ambiguity radius captures higher agent confidence as this is moving in the right direction. See Supplementary Information for details. MaxDiff and NN-MPPI implementations are from the MaxDiff repository.

Schematic figure generation

The schematic figures were generated in Apple Keynote (v. 13.2). Panels were assembled using the same software.

Data availability

All (other) data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper and to replicate the experiments are available in the paper, Supplementary Information and accompanying code (see the Assets folder in Code Availability). Supplementary Movie 1 provides a recording of the robot experiments from the Robotarium platform. Recording and the figures of this paper also available at the folder Assets of our repository63.

Code availability

Pseudocode for DR-FREE is provided in the Supplementary Information. The full code for DR-FREE to replicate all the experiments is provided at our repository63. The folder Experiments contains our DR-FREE implementation for the Robotarium experiments. The folder also contains: (i) the code for the ambiguity-unaware free energy minimizing agent; (ii) the data shown in Fig. SI-8, together with the GP models and the code to train the models; (iii) the code to replicate the results in Fig. 3f and e. The folder also contains the code for the experiments in Supplementary Fig. 4 and provides the instructions to replicate the experiments of Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6. The folder Belief Update Benchmark contains the code to replicate our benchmarks for the belief updating results. The folder Assets contains all the figures of this paper, the data from the experiments used to generate these figures, and Supplementary Movie 1 from which the screen-shots of Fig. 3d were taken. The folder MaxDiff Benchmark contains the code to replicate our MaxDiff benchmark experiments. We build upon the original code-base from the MaxDiff paper21, integrating it in the Robotarium Python environment. The sub-folder Ant Benchmark contains the code for the Ant experiments. MaxDiff and NN-MPPI implementations are from the literature21. As highlighted in the Discussion, extending our analytical results to consider ambiguity inherently in the reward is an open theoretical research direction, interesting per se. Nevertheless, we now discuss how DR-FREE can be adapted to this setting. To achieve this, quoting form the literature31, one could define a modified problem formulation where the reward is appended to the observations available to the agent. In this setting, the reward becomes—quoting the literature31—the last coordinate of the observation, so that it can be embedded into model ambiguity.

References

Wurman, P. R. et al. Outracing champion Gran Turismo drivers with deep reinforcement learning. Nature 602, 223–228 (2022).

Mnih, V. et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 518, 529–533 (2015).

Degrave, J. et al. Magnetic control of Tokamak plasmas through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 602, 414–419 (2022).

Kaufmann, E. et al. Champion-level drone racing using deep reinforcement learning. Nature 620, 982–987 (2023).

Lake, B. M., Ullman, T. D., Tenenbaum, J. B. & Gershman, S. J. Building machines that learn and think like people. Behav. Brain Sci. 40, e253 (2016).

Vanchurin, V., Wolf, Y. I., Katsnelson, M. I. & Koonin, E. V. Toward a theory of evolution as multilevel learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2120037119 (2022).

Manrique, J. M., Friston, K. J. & Walker, M. J. ‘snakes and ladders’ in paleoanthropology: from cognitive surprise to skillfulness a million years ago. Phys. Life Rev. 49, 40–70 (2024).

Kejriwal, M., Kildebeck, E., Steininger, R. & Shrivastava, A. Challenges, evaluation and opportunities for open-world learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 6, 580–588 (2024).

McAllister, R. D. & Esfahani, P. M. Distributionally robust model predictive control: closed-loop guarantees and scalable algorithms. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 70, 2963–2978 (2025).

Moos, J. et al. Robust reinforcement learning: a review of foundations and recent advances. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extract. 4, 276–315 (2022).

Taskesen, B., Iancu, D., Koçyiğit, C. & Kuhn, D. Distributionally robust linear quadratic control. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 36 (eds Oh, A., Naumann, T., Globerson, A., Saenko, K., Hardt, M. & Levine, S.) (Curran Associates Inc., 2023).

Rocher, L., Tournier, A. J. & de Montjoye, J.-A. Adversarial competition and collusion in algorithmic markets. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 497–504 (2023).

West, M. T. et al. Towards quantum enhanced adversarial robustness in machine learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 581–589 (2023).

Hinton, G. E. & Zemel, R. S. Autoencoders, minimum description length and Helmholtz free energy. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vol. 6 (eds Cowan, J. Tesauro, G. & J. Alspector, J.) (Morgan-Kaufmann, 1993).

Hinton, G. E., Dayan, P., Neal, R. M. & Zemel, R. S. The Helmholtz machine. Neural Comput. 7, 889–904 (1995).

Jose, S. T. & Simeone, O. Free energy minimization: a unified framework for modeling, inference, learning, and optimization [lecture notes]. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 38, 120–125 (2021).

Hibat-Allah, M., Inack, E. M., Wiersema, R., Melko, R. G. & Carrasquilla, J. Variational neural annealing. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 952–961 (2021).