Abstract

There is a growing body of research on disease clusters in multimorbidity. Here we systematically review clustering methodologies and perform a meta-analysis of disease cluster stability across the literature, searching Medline and EMBASE from inception to June 5th, 2024, for studies of disease clusters in multimorbidity (including network approaches). Here we include 79 articles. 30% of studies had high risk of bias. Hierarchical cluster analysis was the most used clustering methodology (25% of analyses), followed by latent class analysis (20%) and K-center clustering (15%). Network-based approaches were used in 19% of studies. We perform a meta-analysis of 1226 disease clusters across 73 studies. Strong relationships emerged between neurological, autoimmune, musculoskeletal, and cardiovascular diseases. We identify six meta-analytic disease clusters with moderate stability (Jaccard index ≥0.51), these largely featured cardiometabolic conditions. No disease clusters had high stability (Jaccard ≥0.75) and very few accounted for disease temporality. Multimorbidity disease clustering research is heterogeneous regarding disease definitions, the number of diseases included, and clustering methodologies. Despite this heterogeneity, moderately consistent disease clusters emerge. We provide suggestions to improve the performance and reporting of multimorbidity clustering research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multimorbidity is defined as the co-occurrence of two or more chronic conditions1,2. It is estimated that more than half of the global population above the age of 60 has multimorbidity3. These numbers are projected to rise4, due to increasing noncommunicable disease prevalence and aging population demographics in many countries5,6. Multimorbidity increases the complexity of patient care7 and associated health care costs8. Furthermore, different combinations of diseases will have different implications for health outcomes in multimorbidity. For this reason, an identified research priority is to establish which specific diseases are most likely to co-occur (or cluster) in order to evaluate their interactive and temporal effects on health1. In parallel, the recent uptake of statistical techniques for unsupervised data clustering has advanced the technical capacity to perform such disease clustering analyses9. There is a rapidly growing body of literature attempting to partition multimorbid diseases into groups based on patterns of disease occurrence in large population-based samples10,11. A critical assessment and synthesis of research findings is needed to evaluate the overall progress of disease cluster identification in multimorbidity research.

In this systematic review, we provide an overview and meta-analysis of the current state of research on disease clustering in multimorbidity. We update previous reviews of disease clustering in multimorbidity12,13. Importantly, we extend this investigation to studies using network-based approaches, an emerging area of research that has not previously been included in systematic reviews on this topic. We focus on multimorbidity research using administrative data sources with standardized disease code definitions, to facilitate the harmonization of disease entities across studies and to maximize the generalizability of our research findings to public health surveillance. We also perform a meta-analysis of disease cluster membership for 20 common diseases in multimorbidity research. We identified disease relationships with the highest evidence for clustering across multimorbidity research and directly assessed their stability. This study conforms to our previously published study protocol14.

The aims of this review are as follows: (1) to review the statistical methodologies used to derive clusters of chronic diseases in adults with multimorbidity; (2) to perform a risk of bias assessment with the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies-of Exposure (ROBINS-E) tool; (3) to perform a meta-analysis of disease cluster results identifying which diseases have most frequently clustered together in multimorbidity; and (4) to evaluate the strength of evidence for specific disease clusters in the multimorbidity literature by performing a stability assessment of disease co-occurrence patterns.

Results

Study selection and exclusion are documented in a PRISMA diagram in Fig. 1. A total of 79 articles were included in our review (see Appendices 1–3 for data extracted from each article)15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93. Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The included studies were published between 2009 and 2024, with 56 studies (71%) published since the last systematic review on this topic in 201912 (see Fig. 2A). All studies were in English, except for one study in Spanish84. Study populations were primarily from Europe (77% of studies)15,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,31,32,33,34,35,36,38,39,41,42,44,47,48,49,50,51,53,54, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,73,74,75,77,79,80,81,83,84,85,88,89,91,92,93, followed by Asia (11%)29,37,40,43,44,55,76,86,87 and North America (10%)20,30,39,52,72,78,82,90. All studies from North America were conducted in the United States. Samples sizes ranged from 369 to 10,579,232 individuals (median [IQR] = 238,515 [19,156,554–933]). Half of the studies focused solely on middle-aged to older adult populations (48%)17,20,21,22,23,24,27,30,32,35,40,45,47,48,50,51,53,54,55,58,59,61,64,67,68,69,70,71,76,80,81,82,83,84,85,87,89,91. Only 25% of studies stratified analyses by sex15,25,26,27,30,34,35,38,40,42,48,54,62,63,70,72,86,87,88,89. Overall risk of bias was rated as “Low” or “Some Concerns” for 70% of studies15,17,18,19,21,23,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,35,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,47,48,50,51,53,56,61,62,63,64,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,76,77,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,90,93, and “High” or “Very High” for 30% of studies16,20,22,28,34,36,37,46,49,52,54,55,57,58,59,60,65,75,78,87,88,89,91,92. The highest risk of bias was in the subdomain evaluating data clustering methods; scores in this domain reflect poor methodological reporting and/or lack of validation of cluster results. See Supplementary Fig. 1 for a breakdown of risk of bias ratings by domain.

A Histogram of publication year of multimorbidity disease clustering studies (n = 79), with the five most common clustering methods plotted separately on the right-hand panel. B Risk of bias ratings for studies employing the five most common clustering methods. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Multimorbidity was defined as the co-occurrence of two or more chronic conditions by the majority of studies (62%)15,16,18,19,20,21, 23,24,25,27,28,30,31,33,34,35,38,39,41,42,44,47,49,50,51,53,55,56,57,58,59,63,67,68,69,70,71,73,74,77,80,81,82,83,85,86,87,91,92, an additional 18% of studies defined multimorbidity as two or more acute or chronic conditions17,22,26,32,46,54,60,61,62,64,65,79,84,88. 16% of studies did not include a specific definition for multimorbidity36,37,40,43,45,52,72,75,78,89, 90,93. Studies were split on the inclusion of any measures of health-related outcomes (48% did15,17,19,20,21,23,24,25,27,30,34,41,42,44,45,47,49,52,55,59,62,63,65,67,69,71,72,74,77,78,79,80,81,82,89,91,92,93, 52% did not16,18,22,26,28,29,31,32,33,35,36,37,38,39,40,43,46,48,50,51,53,54,56,57,58,60,61,64,66,68,70,73,75,76,83,84,85,86,87,88,90). The number of conditions included in multimorbidity disease clustering analyses ranged from 12 to 6161 (median [IQR] = 51 [22–149]), The most employed disease coding system were ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes (86% of studies)15,16,17,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,39,40,41,42,43,44,46,47,48,50,51,52,55,59,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,93. Disease codes were analyzed by block-level or 3-5-digit ICD codes in 16% of studies17,22,25,26,28,29,31,32,36,37,43,44,46,62,64,72,75,84,85,88,89, the remainder grouped codes into higher disease entities using a variety of coding algorithms.

Methodological characteristics

See Table 2 for a summary of methodological characteristics, Fig. 2B for a breakdown of risk of bias assessment for the most used clustering methodologies, and Appendices 1–3 for detailed methodological information for each study. Hierarchical cluster analysis was the most used methodology (26% of analyses)19,20,22,26,32,44,48,49,50,52,53,54,60,64,82,84,86,88,89,92 followed by latent class analysis (19%)15,16,21,39,41,42,45,51,53,55,60,67,70,76,78,91. Network-based approaches were used in 19% of studies17,25,29,36,37,38,40,43,46,56,69,72,75,86,90. Only a small subset of studies included the temporality of disease occurrence in clustering (8%)26,36,37,43,56,63,81. The number of disease clusters detected ranged from 2 to 461 (median [IQR] = 6 [4–10]). In the following paragraphs, we summarize methodological characteristics of the most common forms of cluster analysis.

For hierarchical cluster analysis (n = 20 studies)19,20,22,26,32,44,48,49,50,52,53,54,60,64,82,84,86,88,89,92, the most common distance metric used was the Jaccard index (40% of studies)20,22,44,52,60,64,84,92 followed by Yule Q correlation (20%)19,48,50,82. The most common linkage measure was Ward’s minimum variance (45%)20,22,44,49,52,53,64,84,89, followed by average linkage (20%)19,48,50,82. A critical decision in hierarchical cluster analysis is the height at which to cut the dendrogram, this determines disease assignment into clusters. 60% of studies reported employing at least one quantitative measure to determine dendrogram cut-height (i.e., pseudo T2 or F statistics, Calinski/Harabasz index, adjusted Rand index)19,20,22,32,44,49,54,64,84,88,89,92; 15% of studies used a combination of quantitative measures and qualitative judgment (i.e., “clinical judgment”) to determine cut-height20,22,84, 10% of studies used qualitative judgment alone26,52, and 30% of studies did not report any information about how cut-height was determined48,50,53,60,82,87. Overall risk of bias was rated “Low” or “Some concerns” for 45% of studies19,22,32,44,49,64,84,88,92 and “High” or “Very high” for 55% of studies20,26,48,50,52,53,54,60,82,87,89.

For latent class analysis (n = 16 studies)15,16,21,39,41,42,45,51,53,55,60,67,70,76,78,91, a critical decision is determining the number of classes (clusters) to include in the final model. To make this decision, 88% of studies used AIC/BIC or likelihood ratio testing as a quantitative metric of model fit15,21,41,42,45,51,53,55,60,67,70,76,78,91 and 44% of studies additionally used qualitative judgment to arrive at a final model15,21,41,42,51,55,91. One study did not report any criteria to determine model fit16. Latent class analysis groups individuals into classes, not diseases, therefore, another critical decision is the criteria to determine which diseases are typical of the individuals in each class (and thus form multimorbidity “clusters”). 31% of studies used the criteria of disease prevalence of individuals in the class exceeding disease prevalence in the full cohort (the definition of “exceeding” was stated in only two studies, as exceeding by >10%)41,42,53,55,67. 38% of studies simply reported diseases that were highly prevalent in the class: two of these studies reported the top n most prevalent diseases (top 3 or 20)21,91, and four of these studies did not report any cutoff for “high prevalent”45,51,60,70. 25% of studies reported diseases with the highest probability of class membership16,39,76,78, and one study did not state any criteria for determining membership of diseases in classes15. Overall risk of bias was rated “Low” or “Some concerns” for 75% of studies15,21,39,41,42,45,51,67,70,76,78,91, and “High” for 25% of studies16,53,55,60.

For K-center clustering (n = 12 studies)23,28,30,33,34,47,53,62,68,74,85,93, 75% of studies used k-means analysis23,28,30,33,34,47,53,74,85, and k-medians93, k-medoids62, and fuzzy k-means68 analyses were each used by one study. The most common distance metric was data projection through multiple correspondence analysis (33% of studies)28,47,53,85, followed by the Jaccard index (25%)33,34,68. The distance metric was not reported in 33% of studies23,30,74,93. A critical decision with K-center testing is setting the number (k) of clusters to fit the data to. Seventy-five percent of studies reported some quantitative measure to compare different k solutions (i.e., Calinski/Harabasz index, silhouette scores, within-cluster sum of squares)23,28,33,34,47,62,68,74,85,93, and three of these studies additionally used qualitative clinical judgment to arrive at a final solution23,33,34. Two studies did not report any measures used to determine cluster solutions30,53. In addition to testing different k solutions, 25% of studies performed cluster stability testing by bootstrap resampling28,47,85. K-center analyses group individuals rather than diseases; to infer multimorbidity disease clusters, some criteria must be used to identify typical diseases for individuals in each group. In 50% of studies, a disease was said to belong to a cluster if its prevalence among individuals in that cluster was higher than its prevalence in the overall sample28,33,34,53,74,85, often expressed as a ratio with a cutoff of ≥1.0, ≥1.5, or ≥2.0. In 25% of studies, clusters were defined by the diseases that were most prevalent among individuals in that cluster23,30,62. In two studies, diseases were considered cluster members based on parametric testing of differences in prevalence between clusters47,93. Overall risk of bias was rated “Low” or “Some concerns” for 75% of studies23,28,33,34,47,62,68,74,93, and “High” for 25% of studies30,53,85.

For exploratory factor analysis (n = 10 studies)18,24,35,49,57,58,61,64,66,71, all studies used tetrachoric correlation as a distance metric. A critical decision with exploratory factor analysis is determining the number of factors to retain in the analysis (to assign as “disease clusters”). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index18,24,35,57,58,64,66,71 and scree plot of factor eigenvalues18,35,57,58,64,66 were the most reported metrics to determine the number of factors to retain (in 80% and 60% of studies, respectively), with two of these studies additionally using qualitative clinical judgment to guide factor retention18,35. 20% of studies did not report any criteria for determining the number of factors to retain in the analysis49,61. Another critical decision is the strength of factor loading for a disease to be considered a member of the factor (i.e., in order to form a disease “cluster”). 50% of studies used a factor loading threshold of >0.25 to assign diseases to a cluster18,57,58,66,71. 40% of studies used a threshold of >0.3024,35,49,64, and 10% used a threshold of >0.5061. Overall risk of bias was rated “Low” or “Some concerns” for 90% of studies18,24,35,49,57,58,64,66,71, and “High” for 10% of studies61.

For network analyses (n = 15; 8 modularity-based algorithms17,29,46,69,72,75,86,90; 5 random walk-based algorithms36,37,38,43,56; 2 other algorithms25,40), a primary decision in network construction is how to weight the links between disease nodes. The most common link weight was “relative risk” (33% of studies)17,25,36,37,56, although this measure was defined inconsistently across different studies, and often did not follow conventional epidemiological definitions of relative risk as previously articulated by Fotouhi et al.94 27% of studies used a similarity measure (such as phi-correlation or Salton cosine index)38,40,72,86, and 20% used unweighted disease networks43,46,90. Another decision is whether a network should be constructed with directionality, meaning that the order of disease occurrence is captured by the network analysis. Only 27% of studies used directed (temporally ordered) networks36,37,43,56. A variety of clustering algorithms have been applied to determine network disease clusters. 53% of studies used clustering algorithms based on network modularity17,29,46,69,72,75,86,90, the Louvain algorithm was the most used in this category (33% of studies)29,46,72,75,87. 27% of studies used algorithms based on random-walks, these were: Infomap37, Markov clustering36,56, or Random Walktraps25. Overall risk of bias was rated “Low” or “Some concerns” for 47% of studies17,25,36,37,38,56,69, and “High” or “Very High” for 53% of studies29,40,43,46,72,75,86,90.

Disease clustering meta-analysis

It is difficult to assess the quality of clustering results across studies because there is no “gold-standard” of known disease clusters to compare outputs against. Instead, we assume that clusters that are more likely to represent a “true” phenomenon should consistently emerge across different data sources and clustering methodologies and with perturbations of the data frame (i.e., they should show high stability with variations to the underlying data)95,96. Therefore, the goals of our meta-analysis were to test for overall clustering structure in multimorbidity disease cluster data, to identify disease clusters from meta-analytic disease relationships, and to assess the stability of our obtained disease clusters.

73 studies had sufficiently detailed information for inclusion in our meta-analysis15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,38,39,40,41,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,76,77,78,79,81,82,83,84,85,88,89,91,92,93. The remainder did not respond to requests for additional information. See Fig. 3A for a breakdown of age and sex characteristics of the included study samples.

A Participant age and sex distributions for studies included in meta-analysis (n = 73). Study samples were combined into broad age groups where possible (young (0–39 years), middle aged (40–59 years) and older adults (60+ years)), or by the lower age limit for unstratified samples (all ages, 18+, 40+). B The frequency of disease inclusion after harmonization across studies in meta-analysis, expressed as a percentage. COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

There is known heterogeneity in the diseases included in multimorbidity studies13,97,98,99. Thus, to perform disease-specific meta-analyses we defined a list of chronic diseases a priori for meta-data extraction (Supplementary Table 1). Our meta-analysis was restricted to diseases on this list. Study data were harmonized into disease entities on this list based on ICD codes, see “Methods” section for more details on disease harmonization in this meta-analysis. See Fig. 3B for the frequency of harmonized disease inclusion across studies. The most frequently included diseases were: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, ischemic heart disease, cancer, and mood & anxiety disorders (included in >75% of studies). HIV/AIDS and gout were included least frequently (~25% of studies). Disease meta-data and harmonization decisions are provided in Appendix 4.

Meta-analytic disease network: pairwise disease relationships

We extracted disease-specific results from 1226 clusters in total across the included studies. We calculated the strength of disease clustering with Lift, a ratio of the observed co-occurrence between each pair of diseases against expected co-occurrence if they were independent (see “Methods” for details). We included only disease pairs with Lift ≥1.0. We represented disease clustering patterns as an undirected weighted network, with the strength of clustering relationships between disease pairs represented by network link weights.

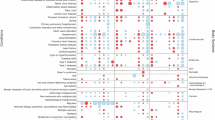

Figure 4A presents the meta-analytic disease network, illustrating dense disease clustering relationships between the 20 harmonized diseases. Disease pairs with high Lift values are linked by darker, thicker edges, indicating these diseases clustered together more often than expected by chance. In other words, a strong Lift connection suggests that when one disease was present in a cluster, the other disease was more likely to also appear in that same cluster. The disease network provides a visual summary of the strongest multimorbidity patterns across the pooled studies.

A Network of multimorbidity disease relationships across included studies (n = 73). Diseases are represented as nodes, and disease nodes are connected by links. Link thickness and color indicate if these two diseases clustered together at a rate that was higher than expected by chance (Lift = observed co-occurrence/expected co-occurrence). B Node degree for each disease in the multimorbidity network. Node degree indicates how many other diseases in the network each disease node formed multimorbidity relationships with. C The average Lift value (observed clustering/expected clustering) for connections with other diseases in the network. This indicates the average strength of multimorbidity relationships for each disease in the network. COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We calculated the descriptive statistics node degree and average link Lift for each disease node in the network, to evaluate each disease’s overall tendency to form disease clusters (Fig. 4B, C). The diseases with highest node degree (indicating they formed clusters with a greater number of other diseases) were: rheumatoid arthritis, Parkinson’s disease, osteoporosis, epilepsy and diabetes (Fig. 4B). The diseases with highest average Lift values across their links (indicating stronger relationships with connected diseases) were: gout, rheumatoid arthritis, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, and schizophrenia (Fig. 4C). Cancer had the fewest connections with other chronic diseases, and the weakest average link Lift. This indicates relatively weak evidence for general/all-type cancer relationships with other conditions, which would likely emerge only with analyses of specific cancer subtypes (i.e. lung cancer).

Meta-analytic disease clusters

We tested whether the meta-analytic disease network contained genuine clustering structure, or if clusters could have arisen purely by chance. To do this, we used the bootstrap resampling approach outlined by Arriata, 2021100 to generate 1000 null networks from our data with random disease relationships. Network modularity was higher in the real disease network compared to all 1000 null networks (percentile rank = 100%). This finding strengthens confidence that the disease clusters observed in multimorbidity research represent meaningful disease associations, rather than being artifacts of algorithms forcing clusters where none truly exist.

Next, we derived specific meta-analytic disease clusters by applying the link community detection algorithm developed by Ahn et al.101, which clusters network links based on their proportion of shared neighbors (allowing disease nodes to appear in more than one cluster). In other words, this algorithm groups disease pairs that are connected to the same neighboring diseases, revealing sets of closely related disease relationships. We detected 43 clusters in total from the meta-analytic disease network. See Supplementary Table 2 for a list of all disease clusters extracted from the meta-network.

We tested the stability of our obtained disease clusters following the approach outlined by Hennig95 by applying the link community detection algorithm to 100 bootstrapped null networks. For each cluster from the observed network, we calculated the average Jaccard coefficient of agreement with the most similar cluster identified in the null networks. Jaccard values ≤ 0.5 indicate a cluster with low stability, and ≥0.75 indicates high stability102. Of the 43 disease clusters detected in the meta-analytic network, six showed moderate stability (Jaccard 0.51–0.71), and none had high Jaccard stability. This indicates that these six diseases clusters recurred consistently despite random perturbations of the data set, providing stronger evidence for their co-occurrence.

Figure 5 displays the six moderately stable disease clusters. Figure 5A represents the whole meta-analytic disease network with disease nodes and links colored based on disease cluster membership. Disease clusters are numbered in descending order of their average stability (average Jaccard index). Chronic kidney disease and diabetes appeared in all six stable clusters. Heart failure appeared in three clusters, and COPD, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and osteoarthritis each appeared in two clusters. Dementia, schizophrenia, and mood & anxiety disorders each appeared in only one cluster. Asthma, cancer, epilepsy, gout, HIV/AIDS, multiple sclerosis, osteoporosis, Parkinson’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and stroke did not appear in any of the stable clusters. Figure 5B presents each individual cluster separately from the overall network, for ease of visualization. Cluster 1 was the only fully connected cluster (all diseases in the cluster were linked to one another), this cluster contained diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure. All other featured a “star topology” where each disease in the cluster was linked to a single central node disease. Clusters 2 and 5 featured cardiovascular diseases as the central nodes (ischemic heart disease and heart failure, respectively), largely connected with cardiometabolic diseases. Clusters 2, 4, and 6 feature neurological disorders as the central nodes (Schizophrenia, mood and anxiety disorders, and dementia, respectively), largely connected with cardiometabolic diseases.

A Network of multimorbidity disease relationships and clusters across included studies (n = 73). Colors indicate cluster membership for six meta-analytic disease clusters with moderate stability (Jaccard index >0.5 in bootstrapped network resampling analysis). Disease nodes are visualized as pie charts, representing the proportion of node links belonging to each cluster. Disease nodes and links that did not appear in any stable clusters are visualized in gray (“NA” cluster membership). B Individual plots for each of the clusters identified in the full multimorbidity network, and their corresponding Jaccard stability scores. COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to studies with Risk of Bias ratings of “Low” or “Some Concerns” (termed low risk of bias (ROB) studies; n = 53; n clusters = 1021). There were no significant differences between low ROB and high ROB studies in geography of data source, age inclusion cutoffs, sample size, publication year, or clustering methods employed (confirmed via t-tests or chi squared tests, all p > 0.05). See Supplementary Fig. 2 for the low ROB disease network. We compared the six clusters identified from the full disease network to the most similar clusters obtained in the low ROB network. All six disease clusters were acceptably replicated in the low ROB network (Jaccard index of best matching cluster ≥0.6, see Supplementary Fig. 3). Clusters 1 and 2 were perfectly replicated in low ROB studies. Clusters 3–6 largely maintained their cardiometabolic disease members, with some differences in membership of osteoarthritis, hypertension, and diabetes. Overall, this sensitivity analysis confirmed that disease cluster results were not driven by studies with a high risk of bias.

Characteristics of studies featuring meta-analytic disease clusters

We expect that multimorbidity disease clusters will vary between population subgroups; age (young vs. older adults) and sex are important considerations in this respect. However, the studies included in our meta-analysis used heterogeneous age bins (or pooled all ages), and rarely stratified samples by sex (see Table 1 and Fig. 3A). Additionally, the meta-analytic clusters we observed are conditional on multiple study features, such as methodological choices, disease inclusion and definitions, and study setting. As a result, we cannot make definitive conclusions about the impact of any single variable (such as age or sex) on disease cluster composition.

To explore how study and sample characteristics might relate to our observed meta-analytic disease clusters, we performed a descriptive analysis of study characteristics conditional on the disease clusters observed. For each of our six stable meta-analytic disease clusters, we identified studies with a similar disease cluster in their results (a cluster “match”). Cluster 1 matches had to contain at least two of its three cluster diseases. For Clusters 2–6, which featured a central node disease in a star network, cluster matches had to contain the central node disease plus at least two other cluster diseases. We then summarized the methodological and sample characteristics of cluster matches. Clustering methodologies were divided into two broad categories: “cluster-based” which groups diseases by maximizing between-group distance and minimizing within-group distance (e.g., hierarchical cluster analysis, and C- or K-means clustering), or “factor-based” which assigns diseases to groups based on their contributions to latent structure in disease co-occurrence data (e.g., exploratory factor analysis, principal component analysis, latent class analysis). Figure 6 presents summary study characteristics for each stable meta-analytic disease cluster. Clusters 1, 2, and 5 appeared with roughly equal frequently in cluster-based and factor-based studies. Clusters 4 and 6 appeared slightly more often in cluster-based methodology studies, while 80% of Cluster 3 matches came from factor-based studies. Most cluster matches came from studies pooling all ages. However, when age stratification occurred, clusters emerged almost entirely in middle-aged and older groups, with younger individuals (aged 0-39) contributing a small minority of matches for Clusters 1 and 2 only. Sex patterns were similar in that most studies combined both sexes in their analyses, however, where sex stratification occurred, there was a slight tendency for Clusters 1, 2, 5, and 6 to appear in male samples.

Characteristics of studies in which meta-analytic disease clusters were observed. For each stable meta-analytic disease cluster, we identified the specific studies where matching clusters appeared (defined for Cluster 1 as a cluster containing at least two of the three diseases, and for Clusters 2–6 as containing the central node disease plus at least two additional cluster diseases). Bar plots show study characteristics as a proportion of total matching disease clusters. Clustering methods are categorized as “cluster-based” if diseases were grouped by maximizing between-group distance and minimizing within-group distance (e.g., hierarchical cluster analysis, and C- or K-means clustering), or “factor-based” if diseases were grouped based on their contribution to latent structure in disease co-occurrence data (e.g., exploratory factor analysis, principal component analysis, latent class analysis). COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, F females, M males. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In summary, while these descriptive analyses highlight some potential subgroup patterns, our meta-analytic disease clusters remain conditional on multiple study characteristics. We cannot attribute disease cluster composition to any single variable, underscoring the need for future research with subgroup stratification and replication across different clustering methodologies.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 79 studies provides an update on the current state of disease cluster discovery in multimorbidity research. We found that multimorbidity disease clustering research using administrative health data has expanded rapidly over the last decade, yet remains methodologically heterogeneous. Although hierarchical clustering is the most common clustering methodology in this field, other unsupervised methods such as latent class analysis, k-center clustering, and network-based approaches are increasingly applied. Very few studies have accounted for the temporality of disease occurrence, with 92% of studies performing cross-sectional disease cluster identification. Within the most employed clustering methods, there was significant heterogeneity in analytic decisions, such as distance metrics and criteria to determine cluster membership.

Our risk of bias assessment found an overall low or acceptable risk of bias in most included studies, but risk of bias varied across the subdomains assessed. Only 20% of studies had low risk of bias in reporting of clustering methodology; often studies lacked transparency in reporting on analytic decisions in clustering pipelines or did not perform any quantitative assessment of goodness of fit of clustering solutions. Another notable source of bias in the risk of bias assessment was a lack of controls for age and sex effects. Some studies did not report these critical descriptive characteristics of included participants. Disease clusters are dependent on population characteristics; therefore, these characteristics of the study sample must be reported. Our findings emphasize the need for clearer reporting and more rigorous validation in multimorbidity clustering research.

Our meta-analysis assessed the strength of evidence for disease clustering relationships among 20 conditions. We found evidence for overall clustering tendencies in the data, validating the use of unsupervised clustering in this field. Additionally, we identified six disease clusters with moderate stability, all of which were replicated in a sensitivity analysis restricted to studies with low risk of bias. These findings are encouraging, suggesting that these disease clusters have the strongest weight of evidence for a “true” tendency to co-occur across populations and analytic approaches. Improving methodological consistency in disease inclusion and clustering methodologies will further strengthen confidence in these key multimorbidity patterns and could yield the development of a targeted list of known disease clusters to interrogate for their impacts on health and health care services.

The core assumption of our meta-analytic approach is that disease clusters that are most likely to represent broad, population-level phenomena will recur across different datasets, analytic methods, and with small perturbations of the data. Since the studies included in our meta-analysis vary in study methodology and population, this heterogeneneous data will reveal only the most universal and stable candidate clusters, rather than context-specific disease clusters. To directly test cluster stability, we introduced random perturbations to our pooled data and found that six of the 43 observed clusters were stable, suggesting that these are the strongest candidates for broadly replicable multimorbidity disease clusters that have emerged in the research literature to date.

The six stable disease clusters are dominated by cardiometabolic diseases, including hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart failure and diabetes. These conditions have well-documented pathophysiological links, such as shared risk factors and etiological mechanisms (e.g., vascular damage, chronic inflammation, insulin resistance)103, supporting their validity. Notably, all six stable disease clusters featured diabetes and chronic kidney disease; the co-occurrence of these diseases is unsurprising given the well-established relationship between diabetes-related microvascular disease and kidney disease104, but their contributions to broader cluster profiles warrant further research attention. In particular, three of the six clusters also featured neurological diseases (dementia, schizophrenia and mood and anxiety disorders), highlighting potential connections between cardiometabolic and brain health105,106,107.

Five out of six stable disease clusters displayed a “star” topology, with one central disease node linked to each other disease in the cluster. The star topography is likely a feature of the hierarchical structure of the link community detection algorithm, whereby links between the non-central diseases in the cluster were allocated to different clusters higher in the clustering dendrogram. Importantly, a star topography does not imply that relationships among non-central cluster diseases are irrelevant for health outcomes. Rather, star topography clusters may be of particular interest to experts focused on the central node disease (Cluster 2: ischemic heart disease, Cluster 3: schizophrenia, Cluster 4: mood and anxiety disorders, Cluster 5: heart failure, cluster 6: dementia) because each cluster provides a set of potentially meaningful disease comorbidities to investigate in individuals with the central node condition.

While our findings are an important step towards identifying broad replicable disease clusters in multimorbidity, we recognize that cluster composition can vary by population context, including age, sex, geographic context, residential setting, and race/ethnicity. Since these variables were not consistently reported across included studies, we were unable to perform necessary stratified analyses to isolate the effects of these population attributes on disease clusters. Our review highlights a consistent lack of sex-stratification in this field to date, underscoring a critical need for future studies examining sex differences. Our results can serve as a baseline reference point for future research against specific population subgroups of interest.

In the following sections, we highlight existing heterogeneity in multimorbidity clustering research and propose strategies to strengthen study methodology in this area. See Box 1 for a summary of our key recommendations for the field.

Regarding disease inclusion in multimorbidity research, we restricted our study sample to those using standardized disease coding systems to facilitate data synthesis and reproducibility. Most studies used ICD-9/10 coding systems as a basis for analysis, but there was substantial variability in how these codes were aggregated to disease entities, with the number of disease entities ranging from 12 to 6121. This fundamental methodological choice significantly impacts two elements of multimorbidity disease clustering research: first in the estimated prevalence of multimorbidity (consider the likelihood of having two or more conditions from a list of 12 possible conditions versus 500 possible conditions); second in the output of clustering algorithms, which are inherently dependent on their inputs. There are consensus lists of core diseases to include in multimorbidity research108,109, but these have not seen uptake in recent studies. Some studies still include acute conditions (such as infection) and non-disease entities (such as injury), which are incongruent with current definitions of multimorbidity as co-occurring chronic diseases1. Furthermore, if highly granular disease definitions (3- or 4-digit code levels) are used, related codes from similar disease constructs are likely to be clustered together, confounding the detection of meaningful patterns between diseases. Future disease clustering research should select diseases for inclusion in alignment with recommended disease lists108,109.

In terms of clustering methodology, a wide range of methods have been applied to disease clustering in multimorbidity. These vary in their conceptual frameworks and assumptions, and the field needs further clarity and consensus on the goals of disease clustering. For instance, is it important for diseases to have membership in multiple clusters (such as in fuzzy-clustering approaches) or to be assigned to a single cluster? Does the temporal order of disease occurrence matter for cluster types? And are there differences between approaches that cluster data at the level of diseases, versus approaches that cluster individuals and later characterize their typical disease profiles? Answering these questions in future research will narrow down the large list of possible clustering methods and prove an analytic roadmap for the field.

The primary source of bias in the literature was unclear reporting of clustering decisions (e.g., dendrogram cut heights, class membership criteria, or k cluster testing). Authors need to clearly state the criteria for determining the optimal number of clusters and/or how diseases or individuals were determined to be exemplary of a cluster (depending on the methods chosen). Reporting these decisions is essential for replicability and to develop consensus around methodological approaches. However, many papers used qualitative judgment or inconsistent criteria to determine disease cluster characteristics (for example, reporting “highly prevalent” diseases in each cluster, without any definition of high prevalence). In these studies, there is potential bias in assigning diseases to clusters based on the authors' preconceptions about disease relationships. This issue was especially prominent in studies employing hierarchical cluster analysis, where the critical decision of where to cut the dendrogram was often unclear, meaning that authors could, in theory, choose the dendrogram cut height that gave preferred results rather than relying on an objective assessment of data fit. The field should follow emerging reporting guidelines relevant to unsupervised machine learning studies110,111, and there is a need for clearer reporting standards specific to unsupervised disease clustering studies.

As research in this area progresses, the field would benefit from explicit validation of cluster results. Cluster validity can be established through formal testing of cluster stability, via bootstrapping and/or cross-validation. Furthermore, the validity of multimorbidity disease clusters will best be demonstrated by their ability to predict health outcomes, which only half of studies have begun to consider.

Our study has several limitations. Only 25% of studies stratified result by sex, therefore, we were unable to conduct sex-specific meta-analyses. There may be important differences in multimorbidity profiles by sex and future research should stratify by sex whenever possible. Age is the most significant risk factor for multimorbidity, and disease profiles are expected to vary by age112. Most studies in this review restricted sample populations to middle-aged and older adults, however, due to the high heterogeneity of our data were unable to stratify analyses to examine age-specific effects. We were additionally limited in our ability to perform meta-analyses by race/ethnicity or clustering methods. Low and middle-income countries were underrepresented, limiting the generalizability of our findings. We recognize that disease case definitions vary across studies and jurisdictions, this is a source of heterogeneity in our data. Finally, the ROBINS-E tool had to be adapted to our specific study question; this was a pragmatic decision to allow for a risk of bias assessment.

This review highlights both the promise and challenges of multimorbidity clustering research. Our analysis focuses on studies using administrative data sources, meaning this evidence is internationally relevant for population-level disease surveillance efforts and research using linked data. Stable patterns of disease co-occurrence, particularly between cardiometabolic and neurodegenerative diseases, provide insights into multimorbidity pathways. The robustness of multimorbidity clustering research will be improved through better consensus on disease inclusion, conceptual methodological decisions, and transparent reporting practices. Areas for future investigation include: sex differences in multimorbidity disease clusters, longitudinal analyses of the evolution of multimorbidity clusters across the life course, identifying which disease clusters have the greatest impact on health outcomes or health care services, and the intersectional impact of sociodemographic factors on each of these points. The stable patterns of disease co-occurrence identified in this study can inform policies and interventions to address the growing burden of multimorbidity on health care systems.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted and reported according to Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE)113, and PRISMA guidelines (PRISMA checklist available as Supplementary Info file). Titles and abstracts were screened against inclusion criteria, and reasons for exclusion were recorded at the full-text stage. All screening steps were completed by two independent reviewers; any disagreements in title and abstract screening were resolved by a third reviewer, and disagreements in the full-text screening were resolved by discussion and consensus. Study screening was performed and documented in Covidence. PROSPERO registration: CRD42023411249. Amendments to the registration were made to add a new team member and update our disease synthesis methodology prior to study selection and data extraction. This study conforms to our previously published study protocol14.

Information sources

We searched Medline and EMBASE. The databases were searched from inception until the search date (initial search performed: March 24th, 2023, search updated: June 5th, 2024). We restricted our search to published articles in peer-reviewed journals. We hand-searched reference lists of included studies to identify additional relevant studies. See Supplementary Materials for a description of our search strategy and example search syntax.

Inclusion criteria

Study characteristics

We included observational studies (cross-sectional, case-control, cohort) employing data-driven methodologies to classify diseases into multimorbidity clusters. There were no restrictions on articles by publication date or language of publication.

Participants

We included studies of the general population of adults aged 18 years and older.

Exposure

We included studies of chronic disease multimorbidity; that is, studies of co-occurring diseases without any single disease focus. We defined chronic as a persistent, long-lasting condition irrespective of the pathophysiology of origin, thus including both communicable and non-communicable diseases. We excluded studies of comorbidity (restricted to participants with a single disease of focus, e.g., dementia114). We excluded studies restricted to populations with specific health contexts unrelated to multimorbidity (e.g., combat veterans, pregnant people, individuals in motor vehicle collisions, or people experiencing homelessness115).

Study methodology

We included studies that characterized disease status with standardized coding systems (such as International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes) and excluded studies that characterized disease status through other means (such as self-report116).

We included studies that used unsupervised data-driven methods to assign diseases to groups based on disease co-occurrence patterns. There are two broad categories of methods meeting this criterion: 1. Factor-based approaches, in which the analysis identifies latent structure in disease co-occurrence data and then assigns diseases to groups based on their contributions to latent structure (i.e., exploratory/confirmatory factor analysis, principal/independent components analysis, and latent class analysis) 2. Cluster-based approaches, in which the analysis employs a distance metric to group diseases by maximizing between-group distance and/or minimizing within-group distance (i.e., hierarchical cluster analysis, and C- or K-means clustering). We excluded studies that used non-data-driven approaches to assign diseases to multimorbidity categories (i.e., counts of the number of co-occurring diseases117, a priori assignment of diseases to groups118, or analyzing disease combinations without clustering119).

We included studies where diseases were clustered based on patterns of disease co-occurrence. We excluded studies that clustered diseases based on measures other than disease co-occurrence (e.g., clustering diseases by their relationship to an outcome120), or that incorporated non-disease measures in clustering algorithms (e.g., clustering diseases and medications together114).

We excluded studies with less than 12 diseases in clustering analyses121, as recommended by Fortin et al.97.

Data extraction

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment were performed on a subset of 15 studies by two independent reviewers (JF and LF). We achieved excellent interrater reliability with 90% agreement on extracted data, thus, the remaining studies were divided and data extraction was performed by a single reviewer (JF or LF), with all final data entries validated by a single reviewer (JF)122. The data extraction form followed Conducting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies of Etiology (COSMOS-E) recommendations123, with additional data categories related to our research question. For articles not in English, we consulted colleagues fluent in the language in question.

Data extracted included: bibliographic information, study design, exposure (multimorbidity) definitions, data source and dates, study population, disease definitions, number of diseases in analysis, disease clustering methodology, distance metric applied, criteria for cluster membership, methods to analyze temporal relationships (if any), subgroup stratifications (if any), details about obtained clusters (total number of clusters and disease composition of each cluster).

A risk of bias assessment was conducted with relevant domains of the ROBINS-E tool124. An additional risk of bias assessment domain was created by the study team to assess bias specific to clustering methodologies (see Supplementary Methods). This domain evaluated whether authors conducted any quantitative analyses of the internal validity of their clustering solutions, and whether clustering results were validated using multiple parameters, algorithms, or independent datasets.

Data synthesis

To synthesize disease data across studies, we defined a list of chronic diseases a priori for harmonization and meta-data extraction (Supplementary Table 1). For a detailed description of the sources considered in the development of our disease list, see Supplementary Methods, or our published protocol paper14. For studies using 3- or 4-digit ICD codes, we categorized codes by case definitions from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS)125, and block-level ICD codes for diseases not present in the CCDSS (cancer and HIV/AIDS). This data pooling approach created qualitatively similar data categories that were robust to anticipated methodological heterogeneity between studies123.

Meta-analysis

Meta-analyses were performed in R (v 4.3.1). Our disease list represents elements in a set, and our meta-analytic approach compared the partitioning of these set elements into subsets across previous research studies. Meta-analysis was performed across two phases:

-

1.

Constructing a meta-analytic disease network

Disease co-occurrence strength was quantified by Lift, which scales the observed co-occurrence between diseases by their expected co-occurrence if they were independent.

$$ {{{{\rm{Lift}}}}}_{\left({{{\rm{A}}}},{{{\rm{B}}}}\right)} \\ =\frac{\left({{{\rm{proportion}}}}\; {{{\rm{of}}}}\; {{{\rm{clusters}}}}\; {{{\rm{with}}}}\; {{{\rm{Disease}}}}\; {{{\rm{A}}}}\;\&\; {{{\rm{Disease}}}}\; {{{\rm{B}}}}\right)}{\left({{{\rm{proportion}}}}\; {{{\rm{of}}}}\; {{{\rm{clusters}}}}\; {{{\rm{with}}}}\; {{{\rm{Disease}}}}\; {{{\rm{A}}}}\right) \, {{{\rm{x}}}} \, \left({{{\rm{proportion}}}}\; {{{\rm{of}}}}\; {{{\rm{clusters}}}}\; {{{\rm{with}}}}\; {{{\rm{Disease}}}}\; {{{\rm{B}}}}\right)}$$(1)All proportions in this Lift formula were calculated only among studies that included both Disease A and Disease B, that is, as a proportion of total clusters among studies where it was possible to observe their joint co-occurrence. We represented disease co-occurrence in an undirected weighted network, where diseases formed the nodes of the network connected by links weighted by the corresponding Lift values between disease pairs. Network analyses were performed with tools from the R packages “igraph” and “ggraph”.

-

2.

Extracting meta-analytic clusters and assessing their stability

We tested for clustering structure in the meta-analytic network, following the approach outlined by Arriata100, implemented in the R package “clustAnalytics”. Briefly, we performed 1000 iterations of bootstrap resampling of disease network links to generate a distribution of null networks. We applied the Louvain algorithm and compared modularity of the real network to average modularity across null networks. If “true” clustering structure exists in the data, then modularity should be higher in the real network compared to null networks, defined as a modularity score exceeding 95% of the null network scores (i.e., alpha = 0.05).

We clustered disease co-occurrence networks with the link community detection algorithm developed by Ahn et al.101, implemented in the R package “linkcomm”. The link community detection algorithm clusters the unique links between nodes based on the proportion of neighbors shared between links, incorporating link weight. We employed Ward’s minimum variance, and the dendrogram was cut at the height that maximized the Calinski–Harabasz index. The Calinski–Harabasz index was high across a narrow range of cut heights, therefore, we chose to cut the dendrogram at the lowest height within this range. This decision was made based on feedback from clinical and public health colleagues that clusters with smaller numbers of diseases are easier to interpret and could provide more targeted information for patient subgrouping in multimorbidity.

We tested the stability of our obtained disease clusters following the approach outlined by Hennig95, implemented in the R package “fpc”.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. Data were extracted from previously published research, and extracted data have been deposited in the figshare database under accession code https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28382543 as Appendices 1–4. Appendices 1–3 provide all extracted data for each included study, separated by data clustering methodology (Appendix 1: cluster-based studies, Appendix 2: factor-based studies, and Appendix 3: network-based studies). Appendix 4 provides cluster-level meta-analytic data, including harmonization to meta-analytic disease entities. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code to reproduce manuscript analyses is provided at: https://github.com/JennFerris/Multimorbidity_cluster_SR.

References

The Academy of Medical Sciences. Multimorbidity: a Priority for Global Health Research (Academy of Medical Sciences, 2018).

World Health Organization. Multimorbidity (WHO, 2016).

Chowdhury, S. R., Chandra Das, D., Sunna, T. C., Beyene, J. & Hossain, A. Global and regional prevalence of multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 57, 101860 (2023).

Kingston, A. et al. Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2035: estimates from the population ageing and care simulation (PACSim) model. Age Ageing 47, 374–380 (2018).

Vos, T. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386, 743–800 (2015).

Pearson-Stuttard, J., Ezzati, M. & Gregg, E. W. Multimorbidity—a defining challenge for health systems. Lancet Public Health 4, e599–e600 (2019).

Moffat, K. & Mercer, S. W. Challenges of managing people with multimorbidity in today’s healthcare systems. BMC Fam. Pract. 16, 15–17 (2015).

Wammes, J. J. G., Van Der Wees, P. J., Tanke, M. A. C., Westert, G. P. & Jeurissen, P. P. T. Systematic review of high-cost patients’ characteristics and healthcare utilisation. BMJ Open 8, e023113 (2018).

Fröhlich, H. et al. From hype to reality: data science enabling personalized medicine. BMC Med. 16, 1–15 (2018).

Hassaine, A., Salimi-Khorshidi, G., Canoy, D. & Rahimi, K. Untangling the complexity of multimorbidity with machine learning. Mech. Ageing Dev. 190, 111325 (2020).

Majnarić, L. T., Babič, F., O’sullivan, S. & Holzinger, A. AI and big data in healthcare: towards a more comprehensive research framework for multimorbidity. J. Clin. Med. 10, 1–23 (2021).

Busija, L., Lim, K., Szoeke, C., Sanders, K. M. & McCabe, M. P. Do replicable profiles of multimorbidity exist? Systematic review and synthesis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 34, 1025–1053 (2019).

Prados-Torres, A., Calderón-Larrañaga, A., Hancco-Saavedra, J., Poblador-Plou, B. & Van Den Akker, M. Multimorbidity patterns: a systematic review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 67, 254–266 (2014).

Ferris, J. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of disease clustering in multimorbidity: a study protocol. BMJ Open 13, 1–7 (2023).

Alvarez-Galvez, J., Ortega-Martin, E., Ramos-Fiol, B., Suarez-Lledo, V. & Carretero-Bravo, J. Epidemiology, mortality, and health service use of local-level multimorbidity patterns in South Spain. Nat. Commun. 14, 1–16 (2023).

Aubert, C. E. et al. Patterns of multimorbidity in internal medicine patients in Swiss university hospitals: a multicentre cohort study. Swiss Med. Wkly. 149, w20094 (2019).

Dervić, E. et al. Unraveling cradle-to-grave disease trajectories from multilayer comorbidity networks. npj Digit. Med. 7, 1–12 (2024).

Diaz, E. et al. Multimorbidity and its patterns according to immigrant origin. A nationwide register-based study in Norway. PLoS ONE 10, e0145233 (2015).

Dong, H.-J., Wressle, E. & Marcusson, J. Multimorbidity patterns of and use of health services by Swedish 85-year-olds: an exploratory study. BMC Geriatr. 13, 120 (2013).

Egan, B. M. et al. A cluster-based approach for integrating clinical management of Medicare beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions. PLoS ONE 14, e0217696 (2019).

Eto, F. et al. Ethnic differences in early onset multimorbidity and associations with health service use, long-term prescribing, years of life lost, and mortality: a cross-sectional study using clustering in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. PLoS Med. 20, e1004300 (2023).

Foguet-Boreu, Q. et al. Multimorbidity patterns in elderly primary health care patients in a south Mediterranean European region: a cluster analysis. PLoS ONE 10, e0141155 (2015).

Forslund, T., Carlsson, A. C., Ljunggren, G., Arnlov, J. & Wachtler, C. Patterns of multimorbidity and pharmacotherapy: a total population cross-sectional study. Fam. Pract. 38, 132–140 (2021).

Fortuna, D., Berti, E. & Moro, M. L. Multimorbidity epidemiology and health care utilization through combined healthcare administrative databases. Epidemiol. Prev. 45, 62–71 (2021).

Fränti, P., Sieranoja, S., Wikström, K. & Laatikainen, T. Clustering diagnoses from 58 million patient visits in Finland between 2015 and 2018. JMIR Med. Inform. 10, e35422 (2022).

Giannoula, A., Gutierrez-Sacristán, A., Bravo, Á, Sanz, F. & Furlong, L. I. Identifying temporal patterns in patient disease trajectories using dynamic time warping: a population-based study. Sci. Rep. 8, 4216 (2018).

Baré, M. et al. Multimorbidity patterns of chronic conditions and geriatric syndromes in older patients from the MoPIM multicentre cohort study. BMJ Open 11, e049334 (2021).

Guisado-Clavero, M. et al. Multimorbidity patterns in the elderly: a prospective cohort study with cluster analysis. BMC Geriatr. 18, 1–11 (2018).

Guo, M. et al. Analysis of disease comorbidity patterns in a large-scale China population. BMC Med. Genom. 12, 1–10 (2019).

Hajat, C., Siegal, Y. & Adler-Waxman, A. Clustering and healthcare costs with multiple chronic conditions in a US Study. Front. Public Health 8, 1–10 (2021).

Hassaine, A. et al. Learning multimorbidity patterns from electronic health records using non-negative Matrix Factorisation. J. Biomed. Inform. 112, 103606 (2020).

Haug, N. N. et al. High-risk multimorbidity patterns on the road to cardiovascular mortality. BMC Med. 18, 1–12 (2020).

Ioakeim-Skoufa, I. et al. Multimorbidity clusters in the oldest old: results from the EpiChron cohort. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 1–15 (2022).

Ioakeim-Skoufa, I. et al. Multimorbidity patterns and trajectories in young and middle-aged adults: a large-scale population-based cohort study. Front. Public Health 12, 1–14 (2024).

Ioakeim-Skoufa, I. et al. Multimorbidity patterns in the general population: results from the EpiChron cohort study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 4242 (2020).

Jensen, A. B. et al. Temporal disease trajectories condensed from population-wide registry data covering 6.2 million patients. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–10 (2014).

Jeong, E., Ko, K., Oh, S. & Han, H. W. Network-based analysis of diagnosis progression patterns using claims data. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–12 (2017).

Beaney, T. et al. Identifying multi-resolution clusters of diseases in ten million patients with multimorbidity in primary care in England. Commun. Med. 4, 1–15 (2024).

Jiang, X. et al. Age-dependent topic modeling of comorbidities in UK Biobank identifies disease subtypes with differential genetic risk. Nat. Genet. 55, 1854–1865 (2023).

Jiang, Y., Ma, S., Shia, B. C. & Lee, T. S. An epidemiological human disease network derived from disease Co-occurrence in Taiwan. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–12 (2018).

Juul-Larsen, H. G. et al. Differences in function and recovery profiles between patterns of multimorbidity among older medical patients the first year after an acute admission—An exploratory latent class analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 86, 103956 (2020).

Juul-Larsen, H. G. et al. Patterns of multimorbidity and differences in healthcare utilization and complexity among acutely hospitalized medical patients (≥65 years) – a latent class approach. Clin. Epidemiol. 12, 245–259 (2020).

Ko, K. et al. Epidemiological characterization of a directed and weighted disease network using data from a cohort of one million patients: network analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 22, 1–12 (2020).

Lai, F. T. T. et al. Comparing multimorbidity patterns among discharged middle-aged and older inpatients between Hong Kong and Zurich: a hierarchical agglomerative clustering analysis of routine hospital records. Front. Med. 8, 651925 (2021).

Lind, K. E. et al. Measuring the prevalence of 60 health conditions in older Australians in residential aged care with electronic health records: a retrospective dynamic cohort study. Popul. Health Metr. 18, 25 (2020).

Lu, H. & Uddin, S. Embedding-based link predictions to explore latent comorbidity of chronic diseases. Health Inf. Sci. Syst. 11, 2 (2023).

Machón, M. et al. Multimorbidity and functional status in older people: a cluster analysis. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 11, 321–332 (2020).

Marengoni, A. et al. Comparison of disease clusters in two elderly populations hospitalized in 2008 and 2010. Gerontology 59, 307–315 (2013).

Bisquera, A. et al. Identifying longitudinal clusters of multimorbidity in an urban setting: a population-based cross-sectional study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 3, 100047 (2021).

Marengoni, A., Rizzuto, D., Wang, H.-X., Winblad, B. & Fratiglioni, L. Patterns of chronic multimorbidity in the elderly population. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 57, 225–230 (2009).

Møller, S. P. et al. Patterns of multimorbidity and demographic profile of latent classes in a Danish population-A register-based study. PLoS ONE 15, e0237375 (2020).

Moran, W. P. et al. Chaos to complexity: leveling the playing field for measuring value in primary care. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 23, 430–438 (2017).

Nichols, L. et al. In simulated data and health records, latent class analysis was the optimum multimorbidity clustering algorithm. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 152, 164–175 (2022).

Nicolet, A. et al. Exploring patient multimorbidity and complexity using health insurance claims data:a cluster analysis approach. JMIR Med. Inform. 10, 1–10 (2022).

Nishida, Y. et al. Multimorbidity patterns in the working age population with the top 10% medical cost from exhaustive insurance claims data of Japan Health Insurance Association. PLoS ONE 18, 1–21 (2023).

Planell-Morell, P., Bajekal, M., Denaxas, S., Raine, R. & Alexander, D. C. Trajectories of disease accumulation using electronic health records. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 270, 469–473 (2020).

Poblador-Plou, B. et al. Similar multimorbidity patterns in primary care patients from two European regions: results of a factor analysis. PLoS ONE 9, e100375 (2014).

Prados-Torres, A. et al. Multimorbidity patterns in primary care: Interactions among chronic diseases using factor analysis. PLoS ONE 7, e32190 (2012).

Prasad, B., Bjourson, A. J. & Shukla, P. Data-driven patient stratification of UK Biobank cohort suggests five endotypes of multimorbidity. Brief. Bioinform. 23, 1–9 (2022).

Buja, A. et al. Multimorbidity patterns in high-need, high-cost elderly patients. PLoS ONE 13, 1–15 (2018).

Profili, F., Maciocco, G., Bellini, B., Razzanelli, M. & Francesconi, P. Prevalence and clustering of chronic diseases in Tuscany (Central Italy): evidence from a large administrative data warehouse. Epidemiol. Prev. 44, 385–393 (2020).

Robertson, L. et al. Identifying multimorbidity clusters in an unselected population of hospitalised patients. Sci. Rep. 12, 5134 (2022).

Roso-Llorach, A. et al. 12-year evolution of multimorbidity patterns among older adults based on Hidden Markov Models. Aging 14, 9805–9817 (2022).

Roso-Llorach, A. et al. Comparative analysis of methods for identifying multimorbidity patterns: a study of ‘real-world’ data. BMJ Open 8, 1–12 (2018).

Ruiz, M., Bottle, A., Long, S. & Aylin, P. Multi-morbidity in hospitalised older patients: who are the complex elderly? PLoS ONE 10, e0145372 (2015).

Schäfer, I. et al. Multimorbidity patterns in the elderly: a new approach of disease clustering identifies complex interrelations between chronic conditions. PLoS ONE 5, e15941 (2010).

Schramm, S., Møller, S. P., Tolstrup, J. S. & Laursen, B. Effects of individual and parental educational levels on multimorbidity classes: a register-based longitudinal study in a Danish population. BMJ Open 12, 1–8 (2022).

Seghieri, C., Tortù, C., Tricò, D. & Leonetti, S. Learning prevalent patterns of co-morbidities in multichronic patients using population-based healthcare data. Sci. Rep. 14, 1–12 (2024).

Siah, K. W., Wong, C. H., Gupta, J. & Lo, A. W. Multimorbidity and mortality: a data science perspective. J. Multimorb. Comorbidity 12, 263355652211054 (2022).

Soley-Bori, M. et al. Disease patterns in high-cost individuals with multimorbidity: a retrospective cross-sectional study in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 74, e141–e148 (2024).

Caballero, F. F. et al. Multimorbidity patterns in older adults: the role of social variables and lifestyle behaviors. Gerontology 69, 716–727 (2023).

Srinivasan, K., Currim, F. & Ram, S. Predicting high-cost patients at point of admission using network science. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 22, 1970–1977 (2018).

Stafford, G. et al. Combined multimorbidity and polypharmacy patterns in the elderly: a cross-sectional study in primary health care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 9216 (2021).

Stockmarr, A. & Frølich, A. Clusters from chronic conditions in the Danish adult population. PLoS ONE 19, 1–24 (2024).

Strauss, M. J., Niederkrotenthaler, T., Thurner, S., Kautzky-Willer, A. & Klimek, P. Data-driven identification of complex disease phenotypes. J. R. Soc. Interface 18, 20201040 (2021).

Tan, X. W., Xie, Y., Lew, J. K., Lee, P. S. S. & Lee, E. S. Patterns of patients with multiple chronic conditions in primary care: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 15, e0238353 (2020).

Tazzeo, C. et al. Multimorbidity patterns and risk of frailty in older community-dwelling adults: a population-based cohort study. Age Ageing 50, 2183–2191 (2021).

Van Cleave, J. H. et al. Multiple chronic conditions and hospitalizations among recipients of long-term services and supports. Nurs. Res. 65, 425–434 (2016).

Vetrano, D. L. et al. Multimorbidity patterns and 5-year mortality in institutionalized older adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 23, 1389–1395.e4 (2022).

Vetrano, D. L. et al. Twelve-year clinical trajectories of multimorbidity in a population of older adults. Nat. Commun. 11, 3223 (2020).

Violán, C. et al. Five-year trajectories of multimorbidity patterns in an elderly Mediterranean population using Hidden Markov Models. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–11 (2020).

Cho, J., Allore, H., Rahimighazikalayeh, G. & Vaughn, I. Multimorbidity patterns, hospital uses and mortality by race and ethnicity among oldest-old patients. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 12, 919–928 (2024).

Violán, C. et al. Soft clustering using real-world data for the identification of multimorbidity patterns in an elderly population: cross-sectional study in a Mediterranean population. BMJ Open 9, 1–14 (2019).

Violán, C. et al. Patrones de multimorbilidad en adultos jóvenes en Cataluña: un análisis de clústeres. Aten. Primaria 48, 479–492 (2016).

Violán, C. et al. Multimorbidity patterns with K-means nonhierarchical cluster analysis. BMC Fam. Pract. 19, 1–11 (2018).

Wang, L., Qiu, H., Luo, L. & Zhou, L. Age- and sex-specific differences in multimorbidity patterns and temporal trends on assessing hospital discharge records in Southwest China: network-based study. J. Med. Internet Res. 24, e27146 (2022).

Wang, X. et al. Multimorbidity among two million adults in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 3395 (2020).

Wartelle, A. et al. Clustering of a health dataset using diagnosis co-occurrences. Appl. Sci. 11, 1–20 (2021).

Webster, A. J., Gaitskell, K., Turnbull, I., Cairns, B. J. & Clarke, R. Characterisation, identification, clustering, and classification of disease. Sci. Rep. 11, 5405 (2021).

Zheng, C. & Xu, R. Large-scale mining disease comorbidity relationships from post-market drug adverse events surveillance data. BMC Bioinform. 19, 500 (2018).

Zhu, Y., Edwards, D., Mant, J., Payne, R. A. & Kiddle, S. Characteristics, service use and mortality of clusters of multimorbid patients in England: a population-based study. BMC Med. 18, 78 (2020).

Collerton, J. et al. Deconstructing complex multimorbidity in the very old: findings from the Newcastle 85+ study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 8745670 (2016).

Corsonello, A. et al. Prognostic interplay of functional status and multimorbidity among older patients discharged from hospital. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 23, 499–506.e1 (2022).

Fotouhi, B., Momeni, N., Riolo, M. A. & Buckeridge, D. L. Statistical methods for constructing disease comorbidity networks from longitudinal inpatient data. Appl. Netw. Sci. 3, 46 (2018).

Hennig, C. Cluster-wise assessment of cluster stability. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 52, 258–271 (2007).

Liu, T., Yu, H. & Blair, R. H. Stability estimation for unsupervised clustering: a review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 14, 1–17 (2022).

Fortin, M., Stewart, M., Poitras, M. E., Almirall, J. & Maddocks, H. A systematic review of prevalence studies on multimorbidity: toward a more uniform methodology. Ann. Fam. Med. 10, 142–151 (2012).

Nguyen, H. et al. Prevalence of multimorbidity in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Comorbidity 9, 2235042X1987093 (2019).

Holzer, B. M., Siebenhuener, K., Bopp, M. & Minder, C. E. Evidence-based design recommendations for prevalence studies on multimorbidity: improving comparability of estimates. Popul. Health Metr. 15, 1–9 (2017).

Arratia, A. & Mirambell, M. R. Clustering assessment in weighted networks. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 7, 1–27 (2021).

Ahn, Y. Y., Bagrow, J. P. & Lehmann, S. Link communities reveal multiscale complexity in networks. Nature 466, 761–764 (2010).

Hennig, C. Dissolution point and isolation robustness: Robustness criteria for general cluster analysis methods. J. Multivar. Anal. 99, 1154–1176 (2008).

Horton, W. B. & Barrett, E. J. Microvascular dysfunction in diabetes mellitus and cardiometabolic disease. Endocr. Rev. 42, 29–55 (2021).

Thomas, M. C. et al. Diabetic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 1, 1–20 (2015).

Tai, X. Y. et al. Cardiometabolic multimorbidity, genetic risk, and dementia: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Health Longev. 3, e428–e436 (2022).

Krittanawong, C. et al. Association of depression and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Med. 136, 881–895 (2023).

Henderson, D. C., Vincenzi, B., Andrea, N. V., Ulloa, M. & Copeland, P. M. Pathophysiological mechanisms of increased cardiometabolic risk in people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses. Lancet Psychiatry 2, 452–464 (2015).

Ho, I. S. S. et al. Examining variation in the measurement of multimorbidity in research: a systematic review of 566 studies. Lancet Public Health 6, e587–e597 (2021).

Ho, I. S. S. et al. Measuring multimorbidity in research: Delphi consensus study. BMJ Med. 1, e000247 (2022).

Stevens, L. M., Mortazavi, B. J., Deo, R. C., Curtis, L. & Kao, D. P. Recommendations for reporting machine learning analyses in clinical research. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 13, E006556 (2020).

Hernandez-Boussard, T., Bozkurt, S., Ioannidis, J. P. A. & Shah, N. H. MINIMAR (MINimum information for medical AI reporting): Developing reporting standards for artificial intelligence in health care. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 27, 2011–2015 (2020).

Divo, M. J., Martinez, C. H. & Mannino, D. M. Ageing and the epidemiology of multimorbidity. Eur. Respir. J. 44, 1055–1068 (2014).

Stroup, D. F. et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 283, 2008–2012 (2000).

Mucherino, S. et al. Changes in multimorbidity and polypharmacy patterns in young and adult population over a 4-year period: a 2011–2015 comparison using real-world data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 1–20 (2021).

Subedi, K. & Ghimire, S. Comorbidity profiles of patients experiencing homelessness: a latent class analysis. PLoS ONE 17, 1–9 (2022).

Han, S. et al. Age, sex, residence, and region-specific differences in prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity among older Chinese: evidence from Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey. BMC Public Health 22, 1–11 (2022).

Han, E. J., Song, M. K. & Lee, Y. The 10-year multimorbidity trajectory and mortality risk in older people with long-term care needs. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 103, 104775 (2022).

Aarts, S. et al. Influence of multimorbidity on cognition in a normal aging population: a 12-year follow-up in the Maastricht aging study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 26, 1046–1053 (2011).

Chartash, D., Gilson, A., Taylor, R. A. & Hart, L. C. The scope of multimorbidity in family medicine: identifying age patterns across the lifespan. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 37, 251–260 (2024).

Bretos-Azcona, P. E., Sánchez-Iriso, E. & Cabasés Hita, J. M. Tailoring integrated care services for high-risk patients with multiple chronic conditions: a risk stratification approach using cluster analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 20, 1–9 (2020).

Gellert, P. aul et al. Multimorbidity profiles in German centenarians: a latent class analysis of health insurance data. J. Aging Health 31, 580–594 (2017).

Shea, B. J. et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 358, j4008 (2017).

Dekkers, O. M. et al. COSMOS-E: guidance on conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies of etiology. PLoS Med. 16, 2149–2159 (2019).

Higgins, J. P. T. et al. A tool to assess risk of bias in non-randomized follow-up studies of exposure effects (ROBINS-E). Environ. Int. 186, 108602 (2024).

Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System (CCDSS) [Data Tool]. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/ccdss/data-tool/ (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Nina Smart for consulting on our study search strategy. We thank Ziying Zhang and Dr. Oralia Gómez-Ramírez for their translation assistance. This work was co-funded by salary support to J.F. from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Michael Smith Health Research BC and BC Centre for Disease Control (Health Systems Impact Fellowship: HSIF-2022-2990 to JF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.F., F.C., M.I., K.S., and A.W. designed the study; J.F., L.F., B.K., and S.H.H. screened studies for inclusion; J.F. and L.F. performed data extraction; J.F. performed data analysis; J.F. drafted the manuscript; All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Lucy Busija, Davide L Vetrano and Jin-Tai Yu for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions