Abstract

Nitrogen isotope fractionation (ε15N) in sedimentary rocks has provided evidence for biological nitrogen fixation, and thus primary productivity, on the early Earth. However, the extent to which molecular evolution has influenced the isotopic signatures of nitrogenase, the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen (N₂) to bioavailable ammonia, remains unresolved. Here, we reconstruct and experimentally characterize a library of synthetic ancestral nitrogenase genes, spanning over 2 billion years of evolutionary history. We assess the resulting ε¹⁵N values under controlled laboratory conditions. All engineered strains exhibit ε15N values within a narrow range comparable to that of modern microbes, suggesting that molybdenum (Mo)-dependent nitrogenase has been largely invariant throughout evolutionary time since the origins of this pathway. The results of this study support the early origin of molybdenum nitrogenase and the resilience of nitrogen-isotope biosignatures in ancient rocks, while also demonstrating their potential as powerful tools in the search for life beyond Earth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The metabolic and physiological characteristics of Earth’s earliest life remain largely obscure, with only the broad outlines discernible for the first 2 billion years of evolution1,2,3,4,5,6,7. In the absence of diagnostic fossils, stable isotopes of carbon and sulfur have served as key geochemical proxies for ancient biological activity2,8,9,10,11. Nitrogen, owing to its centrality in biochemistry, is an appealing candidate for early life reconstructions. However, the complexity and diversity of its metabolic pathways have hindered the interpretation of its record. Uniquely, nitrogen fixation of N2 into bioavailable N is catalyzed by a single enzyme, nitrogenase. This constraint raises the possibility that the evolutionary history of this single enzyme could inform the interpretation of nitrogen isotopes across deep time.

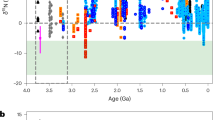

The oldest geochemical evidence for biological nitrogen fixation comes from nitrogen isotopic compositions of ~3.2 Ga Archean sedimentary rocks, with δ15N values ranging from +0.7‰ to −2.8‰12. These values closely resemble those of the biomass of modern organisms using Mo-dependent nitrogenase, which typically fall between +1‰ and −3‰12,13,14,15,16. By contrast, modern organisms expressing alternative vanadium (V)- and iron (Fe)-based nitrogenase isozymes exhibit more negative biomass fractionations (−6‰ to −8‰)13. Similar isotopic patterns in ~2.9 Ga rocks have been interpreted as evidence for the primordial nitrogen cycle driven by Mo-nitrogenase17. Additionally, nitrogen isotope signatures from transient atmospheric oxygenation episodes (“whiffs”) at ~2.66 Ga and ~2.5 Ga suggest that Mo-nitrogenase remained the dominant nitrogen-fixing enzyme before the onset of the Great Oxidation Event (GOE)9,18 at approximately 2.45 Ga, after which time the atmosphere became permanently oxygenated19. Although post-GOE oxidative processes increasingly overprint nitrogen fixation signals in younger rocks, Mesoproterozoic offshore marine sediments deposited under low-oxygen conditions still preserve δ15N values consistent with Mo-nitrogenase activity18,20,21. Even during Phanerozoic ocean anoxic events, such as those in the late Devonian, Jurassic, and Cretaceous, marine sedimentary δ15N values often return to the canonical Mo-nitrogenase range22. Collectively, these records depend on a critical assumption: that nitrogenase-mediated fractionation has remained stable over billions of years, despite profound environmental, ecological, and evolutionary shifts.

Isotopic fractionation during biological nitrogen fixation varies across modern diazotrophs depending on species16, nitrogenase isozyme13, and environmental conditions14,16,23,24. Importantly, all extant nitrogenases are the products of billions of years of molecular evolution, and are adapted to an Earth with an oxygenated atmosphere and an ecologically diverse biosphere25. These factors can impact the isotopic fractionation effect generated from nitrogenase activity by modifying the mechanistic aspects of catalysis. Therefore, it remains uncertain whether the isotopic fractionation signatures observed in modern biology can be reliably extrapolated to interpret nitrogen isotope signatures in the ancient sedimentary record.

We constructed a library of ancient nitrogenases, spanning over 2 billion years, and engineered a model diazotroph, Azotobacter vinelandii (A. vinelandii), to express these ancient variants in vivo. Our work separates itself from prior efforts by beginning with fully synthetic ancient DNA rather than modifying extant genes. We introduce a synthetic-biology framework that reconstructs nitrogenase from first principles, establishing a molecular platform for probing ancient biosignatures. We measured the nitrogen isotope fractionation in the cell biomass of engineered A. vinelandii strains, with all fixed nitrogen coming from the activity of the synthetic ancient nitrogenase. This system enabled a direct test of the evolutionary stability of nitrogen isotope fractionation across deep time, using controlled expression of biochemically functional, phylogenetically inferred ancient enzymes. The resulting isotopic signatures were then evaluated within the context of the sedimentary nitrogen isotopic record and long-term changes in Earth’s biogeochemistry.

Results

Reconstruction of nitrogenase ancestors

Our study builds on a nitrogenase phylogeny and an ancestral nitrogenase protein sequence database (Fig. 1, “Methods”). The phylogeny broadly samples known nitrogenase sequences and host taxonomic diversity, grouping homologs into three major clades: Groups I to III (Fig. 1a). The Nif–III clade also contains two subclades corresponding to the alternative nitrogenases, Vnf and Anf, which incorporate VFe- and FeFe-cofactors, respectively, instead of the canonical FeMo-cofactor found in most nitrogenases26. This overall phylogenetic topology is largely consistent with prior reconstructions of nitrogenase evolution27,28,29.

a Node colors represent the extant taxonomy. b Close-up of Group I nitrogenases. The ancestral nodes targeted in this study are labeled with circles. Heterocystous cyanobacteria (highlighted in teal) serve as a minimum age constraint for the ancestral nitrogenase nodes based on fossil evidence32. c Approximate ages for the origin of nitrogenase isoforms are based on geochemical12 and phylogenetic data29. The estimated timing of the origin of oxygenic photosynthesis and the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) are shaded in green and blue, respectively.

The Group-I clade is distinguished by its association with oxygen-tolerant hosts. In our dataset, approximately 62.5% of Nif-I nitrogenases are either found in, or predicted to occur in, aerobic or facultatively anaerobic prokaryotes, compared to only 6.5% in Group-II and 0% in Group-III (see “Methods”). This strong association between most Group-I nitrogenases and host oxygen tolerance suggests that the diversification of major Group-I lineages likely followed the initial rise of atmospheric oxygen (the GOE) and the resulting emergence of aerobic metabolism5,30. Notably, the Nif-I clade also contains a monophyletic cluster of nitrogenases hosted by cyanobacteria, consistent with abundant cyanobacterial microfossils preserved in Proterozoic strata31,32. Both observations make the Group-I clade particularly well suited for correlating nitrogenase evolution with the sedimentary rock record.

To experimentally reconstruct ancient nitrogenase isotopic signatures, we engineered four ancient nitrogenases representing a temporal series from the present into the deep past ( ~ 700 Ma to 2.3 Ga) in A. vinelandii (Supplemental Table S1). These variants (Anc1 to Anc4), reconstructed from phylogenetic nodes along the oxygen-tolerant Group-I lineage, were individually introduced into a nitrogenase-deficient background to replace one or more native nif genes (Supplemental Table S1). This inferred evolutionary context places the reconstructed ancestors after the GOE and captures a period of permanent but varying atmospheric oxygenation.

Notably, Anc3 and Anc4 precede the diversification of heterocystous cyanobacteria, which form specialized nitrogen-fixing cells33. Phylogenetic analysis places Anc3 prior to the emergence of a monophyletic clade that includes nitrogenase homologs from heterocyst-forming Nostocales, which compartmentalize nitrogen fixation34. The presence of heterocystous cyanobacteria in the Proterozoic fossil record32,35 constraints the minimum ages of Anc3 and Anc4 to approximately 700 Ma to 2.3 Ga (Fig. 1).

Functional characteristics of ancestral nitrogenases

The catalytic function of the ancestral nitrogenases was evaluated by their ability to support diazotrophic growth and catalyze acetylene reduction in vivo (Fig. 2e, f) (“Methods”). Relative to the wild-type, all ancestral strains showed lower rates of ethylene production, a standard proxy for N₂ reduction36, reflecting measurable differences in catalytic performance across evolutionary time. (Fig. 2f).

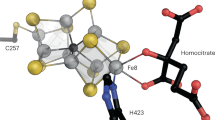

a schematic of methods used to insert ancestral genes into the host A. vinelandii genome37 b Nitrogenase structure and core nif operon, visualized with Mol*64. c Root mean square deviation (RMSD) of atoms in predicted structures versus amino acid sequence identity (%). d Sequence alignment of residues within 5 Å of the FeMo-cofactor of NifD. Residue numbering is based on WT A. vinelandii NifD. e Growth curves of cultures under nitrogen-fixing conditions. A smoothed curve is shown along with the individual data points of five biological replicates per strain. f in vivo ethylene production rates, presented as log2 fold change relative to WT rates. Bars represent mean ± standard error. g In vitro specific activity of purified nitrogenases for H+, C2H2, and N2 substrates. Bars represent mean ± standard deviation.

Purified ancestral nitrogenases exhibited lower in vitro specific activities than their WT counterparts across all tested substrates (Fig. 2g). Despite this, the engineered strains maintained nitrogen-fixation efficiencies comparable to the WT37. Immunodetection showed that nitrogenase protein expressions are generally comparable to the WT (Extended Data Fig. 3), and a prior transcriptomic analysis of Anc2 revealed no significant upregulation of nif genes38. These results suggest that differences arise primarily from intrinsic functional properties rather than changes in expression.

Nitrogen isotope fractionation: Archean to now

Batch cultures of A. vinelandii strains expressing ancestral nitrogenases were grown under diazotrophic conditions, and cell biomass was harvested for nitrogen isotopic analysis. The isotopic fractionation associated with nitrogen fixation (εfixed nitrogen; ε¹⁵N) was calculated relative to atmospheric nitrogen (0‰). All ancestral strains exhibited ε¹⁵N values ranging from −0.9 to −2.9‰ (Fig. 3), and notably, all overlap with the range displayed by the WT. Anc1 and Anc3 were statistically similar to WT, while Anc2 and Anc4 differed significantly from WT and each other, but there was no discernible trend between fractionation values and increasing ancestral enzyme age (Fig. 3b). The isotopic fractionations (ε15N) associated with the ancestral nitrogenases fall within the extremities of the range reported for modern diazotrophs ( + 3.7 to −5.86‰) and align with average values observed in extant bacteria (−1.38‰) and archaea (−4.13‰)16 (Fig. 4). Among the variants, Anc3, the second oldest enzyme, exhibited the broadest range in ε¹⁵N values and the most negative average fractionation.

a Equations used to calculate fractionation. b Isotopic fractionation was measured for whole cell biomass of ancestral strains compared to WT A. vinelandii. Phylogeny is a subset of Group-I tree modified from Fig. 1B. Branches are not to scale. Bars are the average fractionation value calculated across biological replicates, with exact data points shown as well. Error bars represent ±1 standard deviation. Changes in biomass nitrogen isotope signatures throughout early log (c) and late log to early stationary phase (d) of diazotrophic growth are shown. The straight lines are the linear regressions.

N-isotope fractionation values observed in this study compared to the sedimentary δ15N record (a) and known ranges of extant microbial biomass (b). The sedimentary database includes bulk rock δ15N (dark gray) and kerogen δ15N (light gray), from both marine and non-marine rocks across a range of very low to moderate metamorphic grades22,65,66. The purple bar in (a, b) represents the average fractionation signature of all ancestors in this study and is largely coincident with the minimum δ15N values seen in the rock record, which are presumed to record nitrogen-fixation unaffected by subsequent nitrogen cycling. The partial range of bacterial and archaeal fractionation signatures is labeled as the modern range of N-isotopic values16 (see Extended Data Fig. 5 for the full range).

We further assessed whether nitrogen isotopic fractionation changed as a function of diazotrophic growth phase (Fig. 3c, d). Previous work with WT bacteria has shown up to 2‰ variation in isotopic values throughout growth14. In contrast, we observed no significant trend in ε15N values throughout early log phase for WT, Anc1, or Anc2, whereas biomass from Anc3 and Anc4 became slightly more 15N-depleted (Pearson coefficients = −0.75 and −0.66, respectively). Most strains exhibited <1‰ variation in biomass ε15N values, with all strains remaining within the ≤2‰ range reported previously14. At late log to stationary phases (i.e., OD600 of 8–25), biomass 15N increased slightly (i.e., became less 15N depleted) for WT, Anc1, and Anc2 (Pearson coefficients = 0.98, 0.67, and 0.96, respectively), while Anc3 and Anc4 showed weak depletion (Pearson coefficients = −0.23 and −0.4, respectively). Overall, isotopic variation across all growth phases was not a primary control on nitrogen isotopic signatures.

Discussion

In this study, we reconstructed and experimentally characterized the nitrogen isotopic signatures of synthetically reconstructed ancestral nitrogenases to directly probe the molecular origins of Precambrian biosignatures. Because all fixed nitrogen is assimilated into biomass, the measured 15N values of cells reflect the isotopic fractionation of the ancestral enzymes. Despite spanning over 2 billion years of evolutionary divergence, the ancestral strains produced biomass ε15N values broadly comparable to those of extant nitrogenase. Among them, Anc3 produced the most negative average ε15N value, whereas Anc4—the phylogenetically oldest—produced the least fractionated signal. These results demonstrate that nitrogen isotope fractionation by nitrogenase has remained within a relatively narrow range over deep time, suggesting strong conservation of either enzyme-specific isotope effects or whole-cell regulatory processes. More broadly, this work introduces a new experimental framework for interrogating ancient biogeochemical signatures through synthetic molecular evolution, enabling reconstruction of life’s isotopic fingerprints in deep time.

All measured fractionation values from ancestral strains fall within a narrow range (approximately −1 to −3‰), overlapping both with minimum isotopic signatures observed in Archean sedimentary rocks (+2 to −2‰12,39,40,41) and with modern Mo-dependent nitrogen fixers ( + 3.7 to −5.86‰; bacterial average of −1.38‰16) (Fig. 4). The average across all ancestral strains (−1.6 ± 0.5‰) and the tight clustering of individual strain values suggest a striking isotopic continuity extending deep into Earth’s past. These results support the view that Mo-nitrogenases imparted a consistent isotopic biosignature since at least the Paleoproterozoic, and that they can be distinguished from the larger fractionations associated with V- and Fe-nitrogenases (−6 to −8‰13)12.

Critically, whole-rock δ¹⁵N values capture the integrated signature of ancient microbial communities and ecosystem-scale processing, not just nitrogenase enzymes. Even within diazotrophs, the isotopic fractionation effects of downstream nitrogen assimilation steps remain poorly constrained. Nevertheless, the consistency between ancient enzyme-driven ε¹⁵N values and the geologic record22 (Fig. 4) suggests that assimilation pathways and intracellular processing steps have also remained broadly conserved over billions of years of evolution. This is comparable to patterns seen in sulfur isotopes, where once-evolved metabolic strategies exhibit long-term evolutionary stasis9,42,43.

The similarity of the lowest N-isotope values in early Archean rocks (Fig. 4A) suggests that the currently accepted minimum age for nitrogenase (3.2 Ga) may be too conservative, and that its origin could predate what is currently resolvable in the rock record. This hypothesis is supported by recent evidence for elevated dissolved Mo concentrations in Archean seawater44 and the widespread presence of Mo-dependent enzymes by the mid-Archean45. Although Archean sedimentary rocks remain scarce and are often poorly preserved, these constraints do not diminish the significance of our findings. The convergence of geochemical evidence and the consistent ε¹⁵N signatures inherited from ancestral nitrogenase collectively point to an earlier emergence of Mo-based biological nitrogen fixation than previously considered. It is important to note that while other now-extinct ancient biological strategies for nitrogen fixation cannot be entirely ruled out, there is no evidence for any alternative nitrogenase lineage; all characterized nitrogenases derive from a single ancestral enzyme. Abiotic sources of fixed nitrogen, such as lightning-driven reactions46, are also recorded in the rock record, but their isotopic signatures are distinct from those produced by biological nitrogen fixation. Given current knowledge, the most parsimonious interpretation is that the early nitrogen isotope record primarily reflects activity of the nitrogenase enzyme.

Furthermore, while it has been proposed that lower Archean oxygen levels may have enhanced isotopic fractionation via gas diffusion47, our data do not support this interpretation. The stability of ancestral nitrogenase-catalyzed fractionation across over 2 billion years when oxygen levels fluctuated considerably suggests that environmental oxygen concentrations did not exert a primary influence on the enzyme’s isotopic discrimination. Instead, our results support an earlier establishment of the biochemical mechanisms underlying nitrogen isotope fractionation, independent of redox conditions. The effects of other environmental factors, such as temperature, on ancestral nitrogenase activity and isotopic fractionation remain to be explored, but the observed biochemical constancy under variable oxygen levels points to a deeply rooted and resilient biochemical mechanism.

These findings point to a broader principle: once a metabolic pathway becomes established and functionally integrated into the biosphere, its core biochemical properties—and the isotopic signatures they produce—can remain remarkably stable over geological timescales. Crucially, this implies that the persistence of a biosignature is governed less by later environmental changes and more by the physiological context in which the metabolism originally evolved. Gaining insight into life at this critical point is therefore essential, not only for interpreting ancient isotopic records on Earth, but also for recognizing potential signs of life on other worlds. After all, when life was onto a good thing, it stuck to it.

Methods

Ancestral sequence reconstruction

Phylogenetic analysis and ancestral sequence reconstruction of nitrogenase proteins were performed previously37. Briefly, nitrogenase protein sequences were collected by BLASTp search48 against the NCBI non-redundant protein database (accessed August 2020) and curated manually, yielding 385 sets of H-, D-, and K-subunit sequences. Sequences for each subunit were aligned separately by MAFFT v.7.45049. For ancestor Anc2, protein sequence alignments were trimmed using trimAl v.1.250. Evolutionary model selection (LG + G + F) was performed by ModelFinder51 implemented in IQ-TREE v.1.6.1252. Tree reconstruction (using the trimmed alignment) and ancestral sequence reconstruction (using the untrimmed alignment) were performed by RAxML v.8.2.1053 using the best-fit LG + G + F model. For ancestors Anc1, Anc3, and Anc4, an updated tree was built using an untrimmed alignment and RAxML. Ancestral sequence reconstruction was instead performed by PAML v.4.9j54 using the LG + G + model. Oxygen metabolism was calculated via the Oxyphen package55,56.

Sequence and structural comparison

The DDKK complex structures for the WT Nif from A. vinelandii and the selected Group I ancestors were extracted from the Nitrogenase database (https://nsdb.bact.wisc.edu/)57 (Extended Data Fig. 1). To assess the structural variation, we calculated Root Mean Squared Deviation (RMSD) and sequence identity for each ancestor with respect to the WT complex using US-align58 (Fig. 2c).

Sequence embeddings were calculated for the different NifD variant sequences at each node generated during ancestral sequence reconstruction using a 5-dimensional physicochemical representation for each amino acid residue58. Dimensionality reduction and clustering visualization were performed using t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) from the Scikit-learn implementation59 (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Mean posterior probability and SH-like aLRT for each residue and node of the ancestral sequences were calculated (Supplemental Table S3).

Strain engineering and functional assessment

Ancestral nitrogenase sequences were obtained from a previously constructed phylogeny37 (sequences and primers available in Supplemental Tables S1, 2). Strains Anc1-3 were constructed in previous studies (Anc1-237 and Anc360). Anc4 was constructed following these previously established methods. Briefly, ancestral sequences are integrated into a plasmid via Gibson assembly, and this plasmid is then transformed into a Δnif strain. Transformants were screened for nitrogen fixation rescue and loss of kanamycin resistance on solid Burk’s (“B”) medium. The growth rate of each strain in nitrogen-fixing conditions was quantified using previously reported methods61. In brief, liquid B medium was inoculated from a 24-h seed culture to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.05. Three biological replicates of each strain were tested. The cultures were grown in a 96-well, flat-bottom plate (Greiner Bio-One) with a Breathe-Easy adhesive seal (Diversified Biotech). The plate was incubated at 30 °C with a 200-rpm double orbital agitation inside a SPECTROstar Nano Microplate Reader (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany). An optical density reading at 600 nm was taken every 30 min for over 75 h. Doubling time and data visualization were conducted using the R package Growthcurver62.

Acetylene reduction assay was conducted following previous methods37. Biological replicates of each culture were grown overnight and then used to inoculate 100 mL of Burk’s medium with ammonium acetate (“BN media”) to an OD600 of 0.01. Cultures were then grown for 16 h, centrifuged down to a cell pellet at 4255 x g for 10 min, and then resuspended in 100 mL of B medium. The cultures were shaken at 30 °C and agitated at 300 rpm for 4 h, at which time a rubber septum was placed over each flask. 25 mL of headspace air was removed and replaced with 25 mL of acetylene. Headspace measurements were taken 20, 40, and 60 min after acetylene incubation. Ethylene production was quantified via Nexis GC-2030 gas chromatograph (Shimadzu). Cell pellets were collected after the final sampling by centrifuging 24 mL of cultures at 4255 x g for 10 min, washing with 3 mL of phosphate buffer, and pelleting once more as above. Cell pellets were stored at –80 °C. The total protein of each pellet was quantified using a Quick Start Bradford Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad) and CLARIOstar Plus plate reader (BMG Labtech). The total protein of each pellet was used to normalize the acetylene reduction rates.

Growth and sample collection

BN medium was inoculated and grown at 30 °C and agitated at 250–300 rpm. Biological replicates (n = 6 to 9) were prepared for each strain. After 20–24 h, the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of each culture was measured. These cultures were then used to inoculate 500 mL of Burk’s media without any nitrogen (“B media”) in 1 L Erlenmeyer flasks to an OD600 of 0.01. The cultures were placed in a shaker at 30 °C and agitated at 250–300 rpm. The OD600 of the cultures was monitored until the cultures reached log or stationary growth.

To collect samples for isotope analysis, 50 mL of culture was taken from each flask and centrifuged for 10 min at 4255 x g. The pellet was resuspended and washed with 50 mL 1 x PO4, centrifuging as before. The resulting cell pellets were resuspended and washed again with 1 mL 1 x PO4 in a benchtop microcentrifuge (2400 x g for 10 min). The supernatant was removed, and the pellets were dried in an oven at 50 °C for 48 h. Laboratory air samples were also collected for analysis.

Isotopic analyses

All analyses of nitrogen isotopic composition were carried out at the University of Washington Isolab facilities. The bulk nitrogen isotopic analyses were analyzed using an elemental analyzer (Costech ECS 4010) coupled to a continuous-flow isotope-ratio mass spectrometer (CF-IRMS; ThermoFinnigan MAT253).

Approximately 0.500–2.000 mg of freeze-dried A. vinelandii biomass powders were weighed into 3.5 mm x 5 mm tin capsules (Costech) and flash-combusted at 1000 °C under an oxygen-rich atmosphere. The resulting N2 and CO2 gases were purified with chromium oxide at 1000 °C to convert trace CO gas to CO2, and silvered cobalt oxide at 1000 °C to capture sulfur gases and halogens. Then, another purification step was performed with copper at 650 °C to convert trace NOx gases to N2. Traces of H2O were scrubbed with magnesium perchlorate. Subsequently, N2 and CO2 gases were separated chromatographically in a GC column and analyzed for their isotopic composition.

An aliquot of the lab air (2 mL) was analyzed via a Sercon CryoPrep gas concentration system interfaced to a Sercon 20–20 isotope-ratio mass spectrometer at the University of California, Davis Stable Isotope Facility. The measured lab air value was 0.3 ± 0.05‰. The isotope fractionation values associated with nitrogen fixation, calculated using this value for air, are given in Extended Data Fig. 4.

Isotope and abundance measurements were calibrated using three in-house standards (two glutamic acids, GA1 and GA2, and dried salmon, SA). In-house standards were calibrated against the international reference materials USGS40 and USGS4163 (Supplemental Tables S4, S5). Isotope measurements were reported in standard delta notation relative to Air N2:

Calculations and statistics

ε15N of the biomass was calculated using the following equation:

Where δ15NN2 for the biomass samples is atmospheric N2 (0‰) (Supplemental Table S6).

Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA, Pearson correlation coefficient, and Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference tests. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all analyses.

Data availability

All materials, including bacterial strains and plasmids, are available to the scientific community upon request. The phylogenetic data, including phylogenetic trees and ancestral protein sequences, are publicly available at https://github.com/kacarlab/N-isotope. All other data are provided in the Extended Data and Supplementary Information.

References

Lepot, K. Signatures of early microbial life from the Archean (4 to 2.5 Ga) eon. Earth-Sci. Rev. 209, 103296 (2020).

Bontognali, T. R. R. et al. Sulfur isotopes of organic matter preserved in 3.45-billion-year-old stromatolites reveal microbial metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 15146–15151 (2012).

Schopf, J. W. Microfossils of the Early Archean Apex Chert: new evidence of the antiquity of life. Science 260, 640–646 (1993).

Kaçar, B. Reconstructing early microbial life. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 78, 463–492 (2024).

Lyons, T. W. et al. Co-evolution of early Earth environments and microbial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22, 572–586 (2024).

Philippot, P. et al. Early Archaean microorganisms preferred elemental sulfur, not sulfate. Science 317, 1534–1537 (2007).

Garvin, J., Buick, R., Anbar, A. D., Arnold, G. L. & Kaufman, A. J. Isotopic evidence for an aerobic nitrogen cycle in the latest Archean. Science 323, 1045–1048 (2009).

Garcia, A. K., Cavanaugh, C. M. & Kaçar, B. The curious consistency of carbon biosignatures over billions of years of Earth-life coevolution. ISME J. 15, 2183–2194 (2021).

Shen, Y., Farquhar, J., Masterson, A., Kaufman, A. J. & Buick, R. Evaluating the role of microbial sulfate reduction in the early Archean using quadruple isotope systematics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 279, 383–391 (2009).

Ono, S. et al. New insights into Archean sulfur cycle from mass-independent sulfur isotope records from the Hamersley Basin, Australia. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 213, 15–30 (2003).

Havig, J. R., Hamilton, T. L., Bachan, A. & Kump, L. R. Sulfur and carbon isotopic evidence for metabolic pathway evolution and a four-stepped Earth system progression across the Archean and Paleoproterozoic. Earth-Sci. Rev. 174, 1–21 (2017).

Stüeken, E. E., Buick, R., Guy, B. M. & Koehler, M. C. Isotopic evidence for biological nitrogen fixation by molybdenum-nitrogenase from 3.2 Gyr. Nature 520, 666–669 (2015).

Zhang, X., Sigman, D. M., Morel, F. M. M. & Kraepiel, A. M. L. Nitrogen isotope fractionation by alternative nitrogenases and past ocean anoxia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 4782–4787 (2014).

Zerkle, A. L., Junium, C. K., Canfield, D. E. & House, C. H. Production of 15N-depleted biomass during cyanobacterial N2-fixation at high Fe concentrations. J. Geophys. Res.: Biogeosci. 113, 651 (2008).

Nishizawa, M., Miyazaki, J., Makabe, A., Koba, K. & Takai, K. Physiological and isotopic characteristics of nitrogen fixation by hyperthermophilic methanogens: Key insights into nitrogen anabolism of the microbial communities in Archean hydrothermal systems. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 138, 117–135 (2014).

Wannicke, N., Stüeken, E. E., Bauersachs, T. & Gehringer, M. M. Exploring the influence of atmospheric CO2 and O2 levels on the utility of nitrogen isotopes as proxy for biological N2 fixation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 0, e00574–24 (2024).

Koehler, M. C., Buick, R. & Barley, M. E. Nitrogen isotope evidence for anoxic deep marine environments from the Mesoarchean Mosquito Creek Formation, Australia. Precambrian Res. 320, 281–290 (2019).

Stüeken, E. E. A test of the nitrogen-limitation hypothesis for retarded eukaryote radiation: Nitrogen isotopes across a Mesoproterozoic basinal profile. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 120, 121–139 (2013).

Konhauser, K. O. et al. Aerobic bacterial pyrite oxidation and acid rock drainage during the Great Oxidation Event. Nature 478, 369–373 (2011).

Kipp, M. A., Stüeken, E. E., Yun, M., Bekker, A. & Buick, R. Pervasive aerobic nitrogen cycling in the surface ocean across the Paleoproterozoic Era. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 500, 117–126 (2018).

Koehler, M. C., Stüeken, E. E., Kipp, M. A., Buick, R. & Knoll, A. H. Spatial and temporal trends in Precambrian nitrogen cycling: a Mesoproterozoic offshore nitrate minimum. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 198, 315–337 (2017).

Stüeken, E. E. et al. Marine biogeochemical nitrogen cycling through Earth’s history. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 732–747 (2024).

Silverman, S. N., Kopf, S. H., Bebout, B. M., Gordon, R. & Som, S. M. Morphological and isotopic changes of heterocystous cyanobacteria in response to N2 partial pressure. Geobiology 17, 60–75 (2019).

McRose, D. L. et al. Effect of iron limitation on the isotopic composition of cellular and released fixed nitrogen in Azotobacter vinelandii. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 244, 12–23 (2019).

Rucker, H. R. & Kaçar, B. Enigmatic evolution of microbial nitrogen fixation: insights from Earth’s past. Trends Microbiol. 32, 554–564 (2024).

Eady, R. R. Structure−function relationships of alternative nitrogenases. Chem. Rev. 96, 3013–3030 (1996).

Boyd, E. S. & Peters, J. W. New insights into the evolutionary history of biological nitrogen fixation. Front. Microbiol. 4, 201 (2013).

Raymond, J., Siefert, J. L., Staples, C. R. & Blankenship, R. E. The natural history of nitrogen fixation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 541–554 (2004).

Parsons, C., Stüeken, E. E., Rosen, C. J., Mateos, K. & Anderson, R. E. Radiation of nitrogen-metabolizing enzymes across the tree of life tracks environmental transitions in Earth history. Geobiology 19, 18–34 (2021).

Lyons, T. W., Reinhard, C. T. & Planavsky, N. J. The rise of oxygen in Earth’s early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307–315 (2014).

Butterfield, N. J. Modes of pre-Ediacaran multicellularity. Precambrian Res. 173, 201–211 (2009).

Pang, K. et al. Nitrogen-fixing heterocystous cyanobacteria in the Tonian period. Curr. Biol. 28, 616–622.e1 (2018).

Bohme, H. Regulation of nitrogen fixation in heterocyst-forming cyanobacteria: trends in plant science. Trends Plant Sci. 3, 346–351 (1998).

Sánchez-Baracaldo, P., Ridgwell, A. & Raven, J. A. A Neoproterozoic transition in the marine nitrogen cycle. Curr. Biol. 24, 652–657 (2014).

Nagy, L. A. New filamentous and cystous microfossils, ∼2300 m.y. old, from the Transvaal sequence. J. Paleontol. 52, 141–154 (1978).

Hardy, R. W. F., Holsten, R. D., Jackson, E. K. & Burns, R. C. The acetylene-ethylene assay for N2 fixation: laboratory and field evaluation 1. Plant Physiol. 43, 1185–1207 (1968).

Garcia, A. K. et al. Nitrogenase resurrection and the evolution of a singular enzymatic mechanism. eLife 12, e85003 (2023).

Rivier, A., Myers, K., Garcia, A., Sobol, M. & Kaçar, B. Regulatory response to a hybrid ancestral nitrogenase in Azotobacter vinelandii. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e0281523 (2023).

Pellerin, A. et al. Iron-mediated anaerobic ammonium oxidation recorded in the early Archean ferruginous ocean. Geobiology 21, 277–289 (2023).

Stüeken, E. E., Kipp, M. A., Koehler, M. C. & Buick, R. The evolution of Earth’s biogeochemical nitrogen cycle. Earth-Sci. Rev. 160, 220–239 (2016).

Homann, M. et al. Microbial life and biogeochemical cycling on land 3,220 million years ago. Nat. Geosci. 11, 665–671 (2018).

Shen, Y., Buick, R. & Canfield, D. E. Isotopic evidence for microbial sulphate reduction in the early Archaean era. Nature 410, 77–81 (2001).

Ueno, Y., Ono, S., Rumble, D. & Maruyama, S. Quadruple sulfur isotope analysis of ca. 3.5 Ga Dresser Formation: new evidence for microbial sulfate reduction in the early Archean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 72, 5675–5691 (2008).

Hao, W. et al. Evolution of the molybdenum and vanadium cycles through time and their impact on ancient nitrogen fixation. In revision (2025).

Klos, A. S. et al. Biological molybdenum usage stems back to 3.4 billion years ago. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.04.02.646658 (2025).

Barth, P. et al. Isotopic constraints on lightning as a source of fixed nitrogen in Earth’s early biosphere. Nat. Geosci. 16, 478–484 (2023).

Han, E. et al. Nitrogen stable isotope fractionation by biological nitrogen fixation reveals that cellular nitrogenase is diffusion-limited. PNAS Nexus 4, pgaf061 (2025).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinforma. 10, 421 (2009).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B. Q., Wong, T. K. F., von Haeseler, A. & Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–589 (2017).

Nguyen, L.-T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Yang, Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007).

Sobol, M. S., Ané, C., McMahon, K. D. & Kaçar, B. Ecological constraints and evolutionary trade-offs shape nitrogen fixation across habitats. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.05.20.655134 (2025).

Jabłońska, J. & Tawfik, D. S. The number and type of oxygen-utilizing enzymes indicate aerobic vs. anaerobic phenotype. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 140, 84–92 (2019).

Cuevas-Zuviría, B. et al Nitrogenase structural evolution across Earth’s history. eLife 14, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.105613.1 (2025).

Zhang, C., Shine, M., Pyle, A. M. & Zhang, Y. US-align: universal structure alignments of proteins, nucleic acids, and macromolecular complexes. Nat. Methods 19, 1109–1115 (2022).

Atchley, W. R., Zhao, J., Fernandes, A. D. & Drüke, T. Solving the protein sequence metric problem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 6395–6400 (2005).

Harris, D. F. et al. The origins of ATP dependence in biological nitrogen fixation. mBio 15, e01271-24 (2024).

Carruthers, B. M., Garcia, A. K., Rivier, A. & Kaçar, B. Automated laboratory growth assessment and maintenance of Azotobacter vinelandii. Curr. Protoc. 1, e57 (2021).

Sprouffske, K. & Wagner, A. Growthcurver: an R package for obtaining interpretable metrics from microbial growth curves. BMC Bioinforma. 17, 172 (2016).

Qi, H., Coplen, T. B., Geilmann, H., Brand, W. A. & Böhlke, J. K. Two new organic reference materials for δ13C and δ15N measurements and a new value for the δ13C of NBS 22 oil. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 17, 2483–2487 (2003).

Sehnal, D. et al. Mol* Viewer: modern web app for 3D visualization and analysis of large biomolecular structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W431–W437 (2021).

Stüeken, E. E., Buick, R. & Schauer, A. J. Nitrogen isotope evidence for alkaline lakes on late Archean continents. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 411, 1–10 (2015).

Stüeken, E. E. et al. Environmental niches and metabolic diversity in Neoarchean lakes. Geobiology 15, 767–783 (2017).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Interdisciplinary Consortium for Astrobiology Research: Metal Utilization and Selection Across Eons, MUSE [80NSSC17K0296, B.K.] with additional support from the NASA Exobiology Program [NNH23ZDA001N, B.K.] a part of the NASA LIFE Research Coordination Network, USDA-NIFA Hatch Award [WIS05097, B.K.], and the UW-Madison Department of Bacteriology Michael and Winona Foster Predoctoral Fellowship award [H.R]. We would like to thank Amanda Garcia, Scott Chang, Alex Rivier, Chris Wozniak, Kaustubh Amritkar, and Andrew Schauer for their assistance and feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.R.R. and B.K. designed the research; H.R.R., K.B., and D.F.H. performed the research; H.R.R., K.B., D.F.H., R.B., and B.K. analyzed the data; H.R.R., K.B., D.F.H., L.C.S., K.K., R.B., and B.K. interpreted the data; H.R.R. and B.K. wrote the manuscript; B.K. conceptualized and supervised the research. All authors read, edited, and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Magali Ader, Matthew Spence and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rucker, H.R., Bubphamanee, K., Harris, D.F. et al. Resurrected nitrogenases recapitulate canonical N-isotope biosignatures over two billion years. Nat Commun 17, 616 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67423-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67423-y