Abstract

Human organ structure and function are important endophenotypes for clinical outcomes. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified numerous common variants associated with phenotypes derived from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and body. However, the role of rare protein-coding variations affecting organ size and function is largely unknown. Here we present an exome-wide association study that evaluates 596 multi-organ MRI traits across over 50,000 individuals from the UK Biobank. We identified 107 variant-level associations and 224 gene-based burden associations (67 unique gene-trait pairs) across all MRI modalities, including PTEN with total brain volume, TTN with regional peak circumferential strain in the heart left ventricle, and TNFRSF13B with spleen volume. The singleton burden model and AlphaMissense annotations contributed 8 unique gene-trait pairs including the association between an approved drug target gene of KCNA5 and brain functional activity. The identified rare coding signals elucidate some shared genetic effects across organs, prioritize previously identified GWAS loci, and are enriched for drug targets. Overall, we demonstrate how rare variants enhance our understanding of genetic effects on human organ morphology and function and their connections to complex diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-derived traits enable us to study the structure, function, and abnormalities of human organs in vivo. Many of these traits serve as established endophenotypes implicated in complex diseases and related traits. Therefore, it is of great interest to uncover genetic effects using imaging data to better understand the biology of human organs in health and disease. Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified common variants associated with multi-organ imaging traits, including brain structural, diffusion, and functional MRI1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, as well as cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR)9,10,11 and abdominal MRI12,13,14. However, a limitation of common variant signals identified by GWAS is that they often reside in non-coding regions and exhibit small effect sizes, which complicates the direct derivation of biological insights or the identification of causal genes15,16,17,18,19. By focusing on rare variants in protein-coding regions of the genome, whole exome sequencing (WES) studies aim to directly identify genes of interest.

Although existing exome-wide association studies16,17,20,21 (ExWAS) have identified associations for some imaging traits, our knowledge of the rare variant genetic architectures of human organs and their roles in various diseases remains substantially limited. Specifically, most previous ExWAS have focused on a single organ and/or a small set of imaging traits, lacking a multi-organ perspective that simultaneously explores the genetic effects of the human brain and body. For example, Park et al.20 analyzed CT imaging-derived hepatic fat, Haas et al.14 studied liver fat based on abdominal MRI using machine learning, Jurgen et al.21 studied several CMR traits, and Backman et al.16 and Karczewski et al.17 included brain MRI traits in their UK Biobank (UKB) WES studies of a wide range of phenotypes. In addition, these studies might be underpowered because of the relatively limited sample sizes, which are critical for rare variant association studies. Therefore, analyzing more and refined imaging traits, spanning multiple organs, in larger sample sizes will yield deeper insights into the genetic effects of rare variants across the whole body and shared genetic effects across organs10.

Here, we conducted ExWAS for 596 MRI traits derived from the brain, heart, liver, kidney, and lung (Supplementary Data S1) of over 50,000 participants from the UKB study. We used an internal discovery-replication design to make the best use of available data resources to identify rare variants and genes associated with human organ structure and function (Fig. 1). Specifically, all the primary findings and the corresponding interpretations are based on the joint sample for higher statistical power and more stable summary statistics. The joint sample was then split into the internal discovery sample and validation sample to partially verify the robustness of the findings within the UKB study (Fig. 1, Methods, and Supplementary Note). We evaluated various functional annotation approaches for missense variants in gene-level set-based association testing, including conventional methods such as SIFT22, PolyPhen2 HDIV23, PolyPhen2 HVAR23, LRT24, and MutationTaster25, as well as the deep learning-based method AlphaMissense26. We compared our results with previous GWAS on the same set of MRI traits in order to provide shared common and rare variant evidence for a gene’s involvement in a trait. We also used burden heritability regression (BHR)27 tests to characterize the genetic architecture for ultra-rare coding variants (minor allele frequency [MAF] <1 × 10−4) across functional classes. In summary, our study identified exome-wide associations for multi-organ structure and function, providing a valuable source of evidence that could be useful in drug discovery and clinical therapeutics. These findings may also enhance our understanding of the complex interrelations between the human organs, health, and disease.

A An overview of the data included in our study. For imaging phenotypes, we made use of a broad range of multi-organ imaging phenotype data including brain imaging traits such as regional brain volume from structural MRI, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) parameters from diffusion MRI, and functional connectivity and activity traits from resting and task fMRI; CMR traits such as measurements of the aorta (ascending/descending aorta) and heart chambers (left ventricle, right ventricle, left atrium, and right atrium); abdominal MRI traits such as abdominal organ traits (liver, kidney, lung, spleen, and pancreas) and abdominal composition measurements of fat and muscle. For genetic data, we included whole exome sequencing data and focused on rare coding variants (minor allele frequency [MAF] <0.01). Only European individuals with imaging traits were included in the present study (n = 54,365). Some elements in this figure were created in BioRender: Fan, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/oz6gd9i, Fan, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/f2ok1xo, Fan, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/x77lwka, Fan, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/29marqh, Fan, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/a8yoefm, and Fan, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/19zbtn5. B An overview of our study design. We adopted an internal discovery-replication procedure and finalized the summary statistics based on the joint sample (phases 1 to 5 sample). Specifically, we conducted association tests on phases 1 to 3 sample, phases 4 to 5 sample, and phases 1 to 5 sample respectively. We examined (i) whether the detected signals from phases 1 to 3 sample had concordant directions and remained significant in phases 4 to 5 sample; (ii) whether the detected signals from phases 1 to 3 sample had concordant directions and obtained stronger evidence (smaller P-values) in the joint sample. Based on this validated procedure, the significant results and other downstream analyses used the summary statistics generated from this joint sample. The average n indicates the average sample size used in the tests across all 596 phenotypes. Some elements in this figure were created in BioRender: Fan, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/n0j8gb2 and Fan, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/wawasqc.

Results

Overview of variant-level associations with multi-organ MRI traits

Based on European individuals from UKB phases 1 to 5 MRI data (released up to late 2023, average n = 40,038; Fig. 1), we identified 107 rare (MAF < 0.01) variant-level associations (Supplementary Data S2) using a conservative P-value threshold of 2.8 × 10−10 (Bonferroni adjusted for all variant-trait tests with minor allele count [MAC] > 5 as 0.05/178,280,016, Methods) (Fig. 2A). Only predicted loss-of-function variants (pLoF) and missense variants were included in our study. There were 75 gene-trait pairs between 24 unique genes and 62 MRI traits, including 3 abdominal MRI traits, 7 CMR traits of the heart and the aorta, 10 brain structural MRI traits (regional brain volumes), as well as 42 brain diffusion MRI traits (diffusion tensor imaging [DTI] parameters) (Fig. 2B). Additionally, 138 associations (92 unique genes and 107 MRI traits) showed suggestive evidence, surviving a more liberal P-value threshold of 1 × 10−8 (Supplementary Data S3, Methods). These associations spanned across all categories of MRI traits (Supplementary Data S2). As expected, larger effect sizes were linked with lower MAF, which revealed the process of negative selection17,28,29 (Fig. 2C).

A Manhattan plot for variant-level association tests across all 596 imaging phenotypes. Only coding variants of interest were included in the variant-level association tests and associations with P < 1 × 10−3 were plotted. P-values are derived from two-sided tests based on z-scores (or equivalently a χ2 test with one degree of freedom. The dashed lines indicate the variant-level significant P-value threshold at 2.8 × 10−10 from Bonferroni correction and the suggestive P-value threshold at 1 × 10−8 as rare variant genome-wide significance threshold (details are provided in Method). The x-axis shows all the categories of our imaging phenotypes, while we further separated the abdominal MRI traits into abdominal organs and body/fat composition, and separated CMR traits into heart chambers and aorta areas based on the specific traits. Significant coding-variant-level associations (P < 2.8 × 10−10) were labeled to the corresponding genes. For DTI parameters, the unlabeled signals all belong to VCAN gene. B Summary count for the number of signals, unique variants (unique genes in the parentheses), and unique traits within each imaging category that has significant variant-level associations. C The scatter plot for all the variant-level significant results (colored by imaging categories) and suggestive results (in grey color). The x-axis shows the minor allele frequency of each association, and the y-axis is the absolute value of the corresponding genetic effect size in s.d. units. D Graphical illustration of associations between two missense variants (rs72553883 and rs34557412) in TNFRSF13B and spleen volume. The rug plot at the first row demonstrates the locations of these two missense variants. The rug plot at the second row indicates the locations of rare variants in the ‘plof_alpha’ gene burden model, since gene-based burden test also revealed the association between TNFRSF13B and spleen volume. The summary statistics (P-values) of exome-wide associations between TNFRSF13B and blood traits based on burden tests were downloaded from Genebass17. Some elements in this figure were created in BioRender: Fan, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/f2ok1xo, Fan, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/rdhm596, and Fan, Y. (2025) https://BioRender.com/e81d7o9. E Visualization of the associations between two missense variants (rs2652098 and rs143368552) in VCAN and 12 mean diffusivity traits (β1 is the effect size in s.d. of rs2652098 and β2 is the effect size in s.d. of rs143368552).

Due to the lack of independent data sources and the inherent rarity of the variants, identifying rare variant associations typically requires large sample sizes, and findings are difficult to fully replicate. To assess the reliability of our findings derived from the joint sample and maximize the use of available data, we adopted an internal replication procedure30 (Fig. 1 and Methods). Specifically, we split our joint sample to the internal discovery dataset and validation dataset for internal replication. The discovery dataset only included individuals from phases 1 to 3 of MRI release (average n = 30,739), while the validation dataset is independent of it by design and contained individuals from phases 4 and 5 of the MRI release (Method). For the purpose of replication analysis, summary statistics from the discovery sample will be separately compared with results from the validation sample and the joint sample (Method and Supplementary Note). When we restricted our study to the discovery sample, which is the subset of the joint sample, 59 associations passed the Bonferroni threshold of P < 3.5 × 10−10 (Bonferroni adjusted for all variant-level tests with MAC > 5 in this subset, 0.05/142,935,657, Methods) (Supplementary Data S4) and were used for internal replication. Among these 59 associations, 48 had mutations with MAC > 5 suitable for association tests (Supplementary Data S4) in the independent validation sample from phases 4 and 5 of the MRI release. Of these, 45 (93.75% = 45/48) passed the P-value threshold of 2.9 × 10−2 (Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate [FDR] at the 0.05 level), and all had consistent effect size directions as those in the phases 1 to 3 data. We conducted the Pearson correlation test for the effect sizes of the identified associations in the discovery sample and the validation sample. Among these 48 associations with summary statistics available in both stages, we observed a substantial correlation (t = 17.825, df = 46, P = 2.8 × 10−22, rg = 0.935), which shows a high level of agreement between the associations identified in the discovery sample and validation sample. When we relaxed the P-value cutoff to 1 × 10−8, there was still a moderate to high correlation (t = 7.7585, df = 81, P = 2.2 × 10−11, rg = 0.653). Furthermore, 84.7% (= 50/59) of these associations had smaller P-values in the combined phases 1 to 5 sample, and all of them had consistent effect directions. Variants with decreased P-values in the joint analysis implied similar effects of the two sub-cohorts, and we found that the 50 signals that had smaller P-values in the combined sample indeed included all the 45 signals that were replicated in the independent phases 4 and 5 sub-cohort (Supplementary Data S4). A comparison between the observed summary statistics in the internal analysis and the expected improvements of these values in the enlarged joint sample is discussed in Supplementary Note. More details of the results from the internal replication analysis and summary statistics of variant-level associations across different stages can be found in Supplementary Data S4. Overall, this internal replication analysis showed the robustness and validity of our data results. Empirically, over 90% of the 107 variant-level associations identified in the UKB phases 1 to 5 sample could potentially be replicated at the 5% FDR level, should a replication dataset become available. In the following two sections, we highlight some interesting findings across different organs. The complete list of all these 107 variant-level associations is presented in Supplementary Data S2.

Variant-level tests identified associations for hepatic and spleen MRI traits

To our knowledge, associations between rare variants and abdominal MRI-derived traits were only studied in Hass et al.14 with the focus restricted to liver fat and only 18,103 subjects were included. Another study20, with a similar focus on hepatic fat trait, used CT imaging data from 9594 individuals to study the exome-wide associations. Thus, the roles of rare variants in a wider range of abdominal MRI traits remain largely unexplored. In our variant-level analysis, we identified associations between spleen volume and two missense variants in TNFRSF13B (rs72553883, MAF = 0.55%, χ2 = 79.20, 1 df, effectorg = 0.025 L, effect = 0.37 s.d. units, 95% CI = [0.29, 0.45], P = 5.6 × 10−19, and rs34557412, MAF = 0.66%, χ2 = 122.25, 1 df, effectorg = 0.028 L, effect = 0.42 s.d. units, 95% CI = [0.34, 0.49], P = 2.0 × 10−28), while the latter was the top hit among all variant-level associations. TNFRSF13B is a well-known risk gene of common variable immunodeficiency and mutations in TNFRSF13B typically occur in patients who developed splenomegaly31,32,33. In addition, the missense variant rs72553883 was associated with a series of blood-related traits including platelet, myeloid white cell, and lymphoid white cell indices in a previous GWAS34 using genotyping array data while similar associations between rare variants in TNFRSF13B and multiple blood biomarkers were also observed in Karczewski et al.17 using exome data (Fig. 2D). Consistent with these results on spleen abnormalities derived from immunodeficiency and the central role of the spleen in blood filtration and blood cell turnover, our finding points out a direct association between spleen volume and missense mutations in TNFRSF13B. Another missense variant in the manganese transporter SLC30A10 (rs188273166, MAF = 0.09%, χ2 = 94.79, 1 df, effectorg = 63.72 ms35,36 [ms], effect = 1.18 s.d. units, 95% CI = [0.94, 1.42], P = 2.1 × 10−22) was associated with higher corrected T1 liver iron. SLC30A10 is known to be involved in maintaining the manganese level37. This association aligned with recent GWAS that reported the role of rs188273166 in hypermagnesemia symptoms and a SLC30A10-targeted study found its positive effect on corrected T1 liver iron38,39. Interestingly, we also identified a missense variant in DDX51 associated with the fat-free muscle volume of right posterior thigh (rs200735214, MAF = 0.01%, χ2 = 41.06, 1 df, effectorg = −0.87 L, effect = −1.09 s.d. units, 95% CI = [−1.42, −0.76], P = 1.5 × 10−10), which constituted the only signal that passed our stringent P value threshold for human muscle/fat composition traits. Notably, at a more permissive P-value threshold at 1 × 10−8 as our suggestive evidence, we observed that rs200735214 in DDX51 was also associated with the fat-free muscle volume for total thigh (MAF = 0.01%, χ2 = 36.02, 1 df, effectorg = −2.26 L, effect = −0.90 s.d. units, 95% CI = [−1.19, −0.60], P = 1.95 × 10−9) among other signals for human muscle/fat composition traits such as rs534069616 in PLIN4 and posterior thigh muscle fat infiltration (MAF = 0.2%, χ2 = 36.94, 1 df, effectorg = −0.95%, effect = −0.40 s.d. units, 95% CI = [−0.53, −0.27], P = 1.2 × 10−9 for the left; MAF = 0.2%, χ2 = 34.52, 1 df, effectorg = −0.91%, effect = −0.38 s.d. units, 95% CI = [−0.51, −0.26], P = 4.2 × 10−9 for the right). DDX51, a member of the DEAD-box helicase family, plays a crucial role in ribosomal RNA processing and is essential for ribosome biogenesi40,41. Although no direct link between DDX51 and muscle function has been reported previously, the strong association identified in our exome data highlights its potential involvement in muscle composition traits. Meanwhile, PLIN4 encodes a protein known as Perilipin 4, which belongs to the perilipin family of proteins that coat lipid droplets and involve in regulating lipid metabolism42. Perilipins are essential for the proper storage and release of lipids within cells. In particular, PLIN4 has been shown to be highly expressed in skeletal muscle and was found at periphery of skeletal muscle fibers42, which is consistent with our findings.

Variant-level tests identified associations for brain and heart MRI traits

We highlight some rare variants associations with regional brain volumes, brain DTI parameters, and CMR traits of the heart and aorta. A missense variant in ADRA1A was associated with the volume of the left ventral diencephalon (rs771722367, MAF = 0.01%, χ2 = 42.67, 1 df, effectorg = 683.56 mm3, effect = 1.28 s.d. units, 95% CI = [0.90, 1.67], P = 6.5 × 10−11), though the P value for this variant and right ventral diencephalon was P = 3.6 × 10−8 (χ2 = 30.37, 1 df), which did not pass our liberal threshold at 1 × 10−8. ADRA1A was previously reported to be associated with schizophrenia43,44. The ventral diencephalon area was also associated with a missense variant in PKD1 (rs1181041827, MAF = 0.01%, χ2 = 45.71, 1 df, effectorg = 923.88 mm3, effect = 1.73 s.d. units, 95% CI = [1.21, 2.24], P = 5.2 × 10−11 for right ventral diencephalon; MAF = 0.01%, χ2 = 43.11, 1 df, effectorg = 945.24 mm3, effect = 1.77 s.d. units, 95% CI = [1.26, 2.29], P = 1.4 × 10−11 for left ventral diencephalon). For DTI parameters, two missense variants (rs2652098 and rs143368552) in Versican (VCAN) contributed the largest number of associations (63 in total, effect range = [−0.48, 0.42] s.d. units, P < 2.8 × 10−10). Figure 2E visualizes the associations between these two missense variants and 12 mean diffusivity traits. Common variants in VCAN have been extensively associated with white matter traits in previous GWAS2,5,8,45,46,47. Notably, Elliot et al.5 identified an intronic variant rs67827860 with strong associations with DTI traits. Thus, we conducted conditional analysis for all the 63 associations between these two variants in VCAN and DTI traits by conditioning on this nearby common variant as a covariate (Methods). We found that 85.7% of these associations still survived our stringent threshold at 2.8 × 10−10 while all the associations passed our suggestive threshold at 1 × 10−8, which supports the identified missense variants in VCAN as independent signals in addition to the previously identified common variant (Supplementary Data S5). VCAN plays a pivotal role in various neural processes, which may influence the pathophysiology of neurological disorders such as multiple sclerosis48,49,50. Another missense variant rs201680145 in NOTCH3 was also associated with multiple DTI parameters (effect range = [−1.50, 1.70] s.d. units, P < 2.5 × 10−10). Previous studies have revealed the role of NOTCH3 in white matter hyperintensities and several neurodegenerative diseases51,52,53.

We found associations between a missense variant rs189569984 in RBM20 and three CMR traits, including left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV), right ventricular end-systolic volume (RVESV) (MAF = 0.87%, χ2 = 64.60, 1 df, effectorg = −3.77 mL, effect = −0.20 s.d. units, 95% CI = [−0.25, −0.15], P = 9.1 × 10−16 for LVESV; MAF = 0.87%, χ2 = 44.88, 1 df, effectorg = −3.37 mL, effect = −0.16 s.d. units, 95% CI = [−0.21, −0.11], P = 2.1 × 10−11 for RVESV), and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (MAF = 0.87%, χ2 = 56.37, 1 df, effectorg = 1.49 %, effect = 0.24 s.d. units, 95% CI = [0.18, 0.30], P = 6.0 × 10−14). Mutations in RBM20 were previously known to be related to cardiovascular diseases including heart failure and dilated cardiomyopathy54,55,56, and were associated with LVEF in a previous GWAS on CMR traits9. Our rare variant analysis prioritized RBM20 and provided additional evidence for its impact on heart structure and function. Furthermore, we found that ascending aorta maximum/minimum areas were associated with a missense variant in ANO1 (rs201870990, MAF = 0.61%, χ2 = 42.35, 1 df, effectorg = 41.95 mm2, effect = 0.22 s.d. units, 95% CI = [0.15, 0.29], P = 7.6 × 10−11 for maximum; MAF = 0.61%, χ2 = 45.61, 1 df, effectorg = 42.05 mm2, effect = 0.23 s.d. units, 95% CI = [0.16, 0.29], P = 1.4 × 10−11 for minimum). ANO1 was among the loci identified by a recent GWAS57 on ascending aorta diameter (see Fig. 1 in their study57) but was not pointed out or discussed explicitly. Indeed, ANO1 was also reported to be effective in preventing cardiac fibrosis and may be a potential target for therapy58,59. However, future research might elucidate its role in aortic development and/or geometric remodeling. In summary, our analysis of rare variants directly prioritized and implied a small set of genes related to human organs. Due to the rarity of these variants and their lack of linkage disequilibrium (LD) with common variants, they could not be effectively studied in previous GWAS that focused on common variants.

Gene-based burden tests identified complementary signals

Gene-based burden tests enable us to study the collective effects of rare variants within a gene, thus boosting power. In burden tests, the variants of interest defined by annotation and MAF (Methods) are collapsed into a burden mask. Then, the burden score is calculated as the maximum genotype dosage across the single variant sites in the mask, and this score is tested for association (Methods). However, the involved burden models pose challenges to the adjustment for multiple testing since they have unknown correlated structure. Thus, we prioritized a P-value threshold at 1 × 10−9 based on two empirical null distributions60,61 (Methods). A total number of 17,474 genes are available for burden tests in the joint sample and discovery sample. Using the same joint sample as in variant-level tests, we identified 224 significant associations in gene-based tests (P < 1 × 10−9, Methods; Supplementary Data S6 for all the significant results). As different burden models or MAF cutoffs may implicate the same gene-trait associations (Methods), we further summarize the nonredundant results of 67 unique gene-trait pairs60 (involving 26 genes and 57 MRI traits) in Table 1 (a more comprehensive version is provided in Supplementary Data S7). For suggestive evidence, we additionally put all the associations that passed a more relaxed P-value threshold at 1 × 10−8 in Supplementary Data S8. Manhattan plot for all the gene-level associations were presented in Fig. 3A, across all MRI phenotype categories. Three gene-trait pairs overlapped across variant-level and gene-level tests (two associations between ANO1 and max/min aorta area, and an association between TNFRSF13B and spleen volume), indicating the robustness of these gene-trait pairs as both a single rare variant in this region and the joint effects of variants across the region are strong enough to drive an association. Consistent with observations in previous ExWAS17,61, we identified 21 additional genes, highlighting the power of gene-based burden tests in rare variant association studies. In particular, we found 3 genes and 18 gene-trait associations for brain functional MRI (fMRI) traits, which did not have any signals in variant-level tests. To evaluate the reportability of our findings, we wanted to follow a similar procedure in variant-level tests to perform an internal replication. However, many rare mutations, particularly those with a MAF of less than 0.01%, accounted for a large proportion of our discoveries but were not observed in the smaller independent dataset from phases 4 to 5 (average n = 8989). Therefore, we only made use of the internal discovery sample and examined whether the associations in the combined phases 1 to 5 sample had smaller P-values than those in the phases 1 to 3 data, similar to internal-replication analysis for variant-level tests (Methods and Supplementary Note). When we restricted the discovery sample to individuals in phases 1 to 3, there were 96 significant associations for 25 unique gene-trait pairs (P < 1 × 10−9, Supplementary Data S9). Within these 96 associations, 79.2% (76/96, 19 gene-trait pairs) had smaller P-values in the combined phases 1 to 5 sample, all of which had concordant directions of effects (Supplementary Data S9). The detailed summary statistics and results of internal replication analysis for gene-based associations have been provided in Supplementary Data S9. We discuss some of the 67 gene-trait pairs in the following two sections.

A Manhattan plot for gene-level burden tests across all 596 imaging phenotypes. For significant gene-trait pairs appearing in multiple burden models, we plotted the association with the smallest P-value. P-values are derived from two-sided tests based on z-scores (or equivalently a χ2 test with one degree of freedom. The dashed lines indicate the gene-level significant P-value threshold at 1 × 10−9 as well as the suggestive P-value threshold at 1 × 10−8. The multiple testing thresholds were derived from empirical null distribution with details provided in Method. The y-axis is capped at 1 × 10−30 and only gene-trait pairs with P < 1 × 10−3 were included. The color legend and x-axis are same as the Manhattan plot for variant-level associations in Fig. 2A. Significant genes were labeled. B Effect sizes for all non-redundant significant gene-trait pairs (n = 67, corresponding to Table 1) within each imaging category. The dashed line indicates an effect size of zero. We labelled all the genes that had the largest positive and negative effects within each imaging category and genes that had an absolute effect size greater than 1.5. C Distribution of total brain volume (in cm3) of mutation carriers (N = 7 individuals) versus non-carriers (N = 40,739 individuals) of PTEN among all the individuals (N = 40,746) included in the exome-wide association test for total brain volume. To illustrate, we select the burden model with the smallest P-value, that is “plof_int5”, which means the aggregation of pLoF variants and missense variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) cutoff at 1 × 10−4. In the violin and boxplots shown, the violin plot illustrates the full distribution of total brain volume across carriers and non-carriers of PTEN burden variants using kernel density estimation, with the width of the violin representing data density at each value. Overlaid boxplots summarize key statistics: the center line denotes the median; the bounds of each box represent the first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles; and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) from the box. The black diamonds indicate group medians. D The effect size estimates (circles, triangles, and diamonds at the centers of bars for distinct MAF cutoffs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (bars) across different burden models of PTEN (N = 40,476 individuals). The color indicates distinct MAF cutoffs. The y-axis includes all the burden models (Methods). Only burden models with minor allele count >5 (after aggregation) were tested (Methods) and plotted.

Genes associated with abdominal, brain, and heart MRI traits in burden tests

As shown in Table 1, we identified 5 genes for abdominal MRI traits, 7 for CMR traits, 7 for regional brain volumes, 8 for brain DTI parameters, and 3 for brain fMRI traits. Figure 3B highlights the genes with large effect sizes. Below, we highlight several interesting findings for each trait category.

We found that 4 out of 5 signals of abdominal MRI traits from the combined phases 1 to 5 sample also present in the phases 1 to 3 data (Supplementary Data S4). The highest hit among all the gene-level signals was the association between spleen volume and TNFRSF13B when aggregating the effects of pLoF and Alpha damaging (Methods) missense variants (MAF = 1.4%, χ2 = 246.24, 1 df, effectorg = 0.027 L, effect = 0.40 s.d. units, 95% CI = [0.35, 0.45], P = 1.7 × 10−55) (Fig. 2D). In addition to TNFRSF13B, we observed that SH2B3 was also associated with spleen volume (MAF = 0.4%, χ2 = 63.40, 1 df, effectorg = 0.025 L, effect = 0.38 s.d. units, 95% CI = [0.29, 0.48], P = 1.7 × 10−15), where spleen abnormalities (e.g. splenomegaly) and associated blood traits have been previously reported62,63,64,65. For muscle measurements, we found an association between fat-free muscle volume of the posterior thigh and TANC1 (MAF = 0.01%, χ2 = 37.63, 1 df, effectorg = −1.06 L, effect = −1.32 s.d. units, 95% CI = [−1.74, −0.90], P = 8.5 × 10−10). TANC1 had genetic overlaps with the identified loci in previous GWAS on heel bone mineral density66 and its role in muscle development and rhabdomyosarcoma has been discussed in previous studies67,68.

As shown in Fig. 4A, TTN was associated with 8 CMR traits, including LVESV (MAF = 0.39%, χ2 = 109.60, 1 df, effectorg = 7.34 mL, effect = 0.40 s.d. units, 95% CI = [0.32, 0.47], P = 1.2 × 10−25), LVEF (MAF = 0.39%, χ2 = 140.48, 1 df, effectorg = −3.48 %, effect = −0.56 s.d. units, 95% CI = [−0.66, −0.47], P = 2.1 × 10−32), as well as global and regional peak circumferential strain measurements (effect range = [0.32, 0.60] s.d. units, P range = [1.2 × 10−21, 2.4 × 10−11]). Figure 4C visualizes the original effect sizes (in percentage) of TTN on different regional peak circumferential strain measurements and a global peak circumferential strain measurement. We observed that they generally produced similar and consistent results. These results make sense as TTN is a well-known gene associated with cardiac structure9 and cardiovascular diseases such as heart failure69, dilated cardiomyopathy70,71, atrial fibrillation72, supraventricular tachycardia, and mitral valve disease21. In addition to the previously known exome-wide association between TTN and LVESV21, our findings suggest a broader influence of this gene on cardiac structure and function, using a larger sample size and an expanded set of CMR traits.

A Graphical illustration of 8 CMR traits of left ventricle (LV) associated with TTN. LVESV, left ventricular end-systolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; and Ecc, peak circumferential strain, including both global (“Global”) and regional traits (such as “AHA_9”). B Five genes (ANO1, COL21A1, GEM, PLCE1, and TAGLN) associated with ascending aorta and descending aorta areas. PLCE1 was also associated with brain fMRI traits. Three ICA-based functional activity traits (Net25_Node3, Net25_Node5, and Net25_Node9) associated with PLCE1 are illustrated, with their major brain regions and networks labeled. The color represents the weight profile of the ICA node. In addition, COL21A1 was associated with cerebrospinal fluid volume. C [Top]: original effect sizes (in percentage; circles) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (bars) of TTN on different regional peak circumferential strain measurements (N = 48,948 individuals for AHA_9; 48,948 individuals for AHA_13; 48,940 individuals for AHA_14; 48,943 individuals for AHA_15; 48,947 individuals for AHA_16) and a global peak circumferential strain measurement (N = 48,934 individuals). [Bottom left]: absolute values of original effect sizes (in mm2; circles) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (bars) of ANO1, COL21A1 and GEM on ascending aorta maximum and minimum area (N = 48,132 for ascending aorta maximum area and N = 48,135 for ascending aorta minimum area); we use ‘+’ to indicate the positive effects and ‘-’ to indicate the negative effects. [Bottom right]: absolute values of original effect sizes (in mm2; circles) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (bars) of PLCE1 and TAGLN on descending aorta maximum and minimum area (N = 48,143 for ascending aorta maximum area and N = 48,150 for ascending aorta minimum area). Association between TAGLN and descending aorta maximum area was among the suggestive results (Supplementary Data S8).

We would like to highlight our exome-wide associations with CMR traits of aorta. Notably, three genes (ANO1, COL21A1, GEM) were associated with both maximum and minimum area of ascending aorta, while PLCE1 was associated with maximum and minimum area of descending aorta (Fig. 4B, C). In particular, both COL21A1 and GEM lower the size of the ascending aorta (effectorg range = [−61.16, −54.95] mm2, P range = [1.7 × 10−13, 6.4 × 10−13] for COL21A1 and effectorg range = [−87.68, −87.06] mm2, P range = [1.3 × 10−12, 1.06 × 10−11] for GEM, respectively). Rare variants in COL21A1 and GEM were reported to be linked to higher pulse blood pressure in a previous rare variant association study of blood pressure73. A smaller aorta leads to a wider pulse pressure because it increases aortic characteristic impedance, which is highly dependent on aortic diameter. Our results on these aorta area-lowering genes further provide the evidence for the underlying mechanisms of previous observations. Moreover, GEM is involved in cardiac activities74 and is related to heart failure74,75. Another study76 pointed out that such effects of GEM could potentially be used as a gene therapy target in treating ventricular arrhythmias and heart failure. Our discovery indicated that GEM may also impact the structural integrity of the ascending aorta, thus improving our understanding of the role of GEM in cardiovascular health. In contrast, missense variants in ANO1 have positive effect. The role of ANO1 has been discussed in our variant-level analysis and we recaptured these associations again by aggregating the missense variants in ANO1 using burden test (effectorg range = [32.43, 32.79] mm2, P range = [1.7 × 10−13, 6.4 × 10−13]), suggesting the similar effects and aligned directions across a group of missense variants within ANO1. In addition, TAGLN was also associated with descending aorta minimum area (MAF = 0.05%, χ2 = 38.71, 1 df, effectorg = 62.28 mm2, effect = 0.67 s.d. units, 95% CI = [0.46, 0.88], P = 4.91 × 10−11) while its association with descending aorta maximum area was observed at a more liberal P value threshold at 1 × 10−8 (Supplementary Data S8). At the bottom of Fig. 4C, we found that the effects (in mm2) of different genes on the aorta area could largely vary in terms of both directions and the sizes. GOLM1 was found to be associated with descending aorta distensibility (MAF = 0.01%, χ2 = 44.23, 1 df, effectorg = 2.85 mmHg, effect = 2.5 s.d. units, 95% CI = [1.77, 3.24], P = 2.93 × 10−11). A recent study demonstrated that GOLM1 may present a potential therapeutic target for treat sepsis-induced cardiac dysfunction in animal models77. GOLM1 was also related to Alzheimer’s disease and the implied cognitive deficits78. However, its role in aortic wall remodeling requires further study. Using GTEx data resources79, we found that four (ANO1, COL21A1, GEM, TAGLN) out of five genes (ANO1, COL21A1, GEM, TAGLN, PLCE1) associated with ascending/descending aorta areas had moderate to high expression and overexpressed in aorta while PLCE1 had high expression in artery tissues in general, which further supports their roles in affecting the structure of aorta.

For brain MRI traits, we highlight in Fig. 3C, D the strongest association between PTEN and total brain volume with a large effect size when aggregating the pLoF and missense variants (MAF = 0.01%, effectorg = 386,703.40 mm3, effect = 2.77 s.d. units, 95% CI = [2.22, 3.32], P = 5.8 × 10−23). The distribution of total brain volume in cm3 for PTEN mutation carriers versus non-carriers is provided in Fig. 3C. Notably, as illustrated in Fig. 3D, different burden masks would yield associations with various strengths, and we observed that the signal became stronger if we aggregate ultrarare (MAF < 1 × 10−4) pLoF variants and damaging missense variants in PTEN, which may not be observed and testable in the previous ExWAS16,17 with a sample size smaller than ours due to the low MAF. In a recent ExWAS80, PTEN was associated with autism spectrum disorder. Indeed, PTEN is a well-known gene that has been consistently linked to autism spectrum disorder81,82,83,84, brain development85,86,87, and brain clinical phenotypes including brain overgrowth88,89,90, with an enlarged brain volume representing an associated phenotype in these conditions. To our knowledge, no previous GWAS or ExWAS has linked PTEN to any brain MRI measurements, thus our analysis provided direct evidence connecting rare variants in PTEN with total brain volume. Another gene OMA1 was observed to be associated with 7 regional brain volume traits including superior frontal gyrus, lateral orbitofrontal cortex, and precentral gyrus for both sides of the brain and right superior parietal lobule (effectorg range = [−524.83, −171.02] mm3 units, P range = [1.77 × 10−14, 6.35 × 10−10]). Notably, PTEN and OMA1 regulate the PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1) and thus may be useful in preventing epileptogenesis91 while a protective role of OMA1 in neurodegeneration92,93,94 was previously reported. The remarkably strong association PTEN demonstrate that even within a general healthy cohort (as opposed to disease-focused or case-control studies), we can identify biological links between genes associated with neurodevelopmental disorders using MRI data.

For DTI parameters, in contrast to variant-level analysis where missense variants in VCAN accounted for the most associations, our gene-based burden tests revealed a more diverse range of effects on white matter, with 8 distinct genes accounting for 10 gene-trait associations. For brain fMRI traits, PLCE1, GLUL, and KCNA5 were identified to be associated with 18 phenotypes, where PLCE1 contributed to 16 of them. We found that many gene-trait pairs would not have been identified if singleton burden models or the recent deep learning-based AlphaMissense26 burden models were not included. We will provide more detailed discussions about these interesting associations in the following sections.

Overall, gene-based burden tests examined the aggregated effects of rare variations within genes and advanced our understanding of the underlying genetic dispositions across the abdomen, heart, and brain organs. Our findings prioritized a set of rare genes previously unknown to be associated with human organs. We further discussed examples of genetic overlaps between these MRI signals and other health-related phenotypes, which may help to understand complex diseases by providing exome-wide insights into the genetic mechanisms underlying multiple human organs including abdominal, cardiac, and neurological pathologies.

Pleiotropic effects of PLCE1 and COL21A1 on brain and heart MRI traits

In our gene-based burden tests, PLCE1 was associated with the largest number of phenotypes including 16 brain fMRI traits (including 5 traits from parcellation-based approach95 and 11 traits from whole brain spatial independent component analysis [ICA]96,97,98) and 2 CMR traits (descending aorta maximum/minimum areas) (Fig. 4B). In addition, COL21A1 was associated with both brain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume and ascending aorta maximum/minimum areas (Fig. 4B). We found that a recent GWAS99 discovered the associations of descending and ascending aorta areas separately with PLCE1 and COL21A1 while PLCE1 was also found in previous GWAS3,5,100 for brain fMRI. PLCE1 encodes a phospholipase (PLCε) that catalyzes the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate to generate inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate and diacylglycerol. They are common second messengers regulating multiple cellular processes, including cell activation, growth, differentiation, and gene expression101. Interestingly, prior mechanistic study identified a causal role for PLCε on the development of thoracic dilation102 and dissection103. Similarly, COL21A1 encodes the alpha-1 chain of collagen 21, a known extracellular matrix component in the arterial wall, secreted by vascular smooth muscle cells. While the previous GWAS99 suggested distinct genetic bases between the ascending and descending aorta and linked aortic traits to brain small vessel disease, it did not establish direct associations of these genes with other brain MRI traits. Our results provide exome-wide evidence highlighting the associations of PLCE1 and COL21A1 with both brain and heart MRI traits. Additionally, a previous study suggested that the observed GWAS effects of PLCE1 on fMRI traits may be blood-derived100. Our exome-wide evidence supporting PLCE1’s role in both aortic and fMRI traits aligns with this hypothesis. Therefore, it might be helpful to integrate cardiac features and cardiac-related genetic information when analyzing fMRI data, given that fMRI phenotypes are blood oxygen level-dependent and are influenced by blood flow.

The connection between the heart and brain has increasingly garnered attention10,104. Moreover, the role of hemodynamic role of the aorta involved the cushioning of pressure and flow pulpability caused by the intermittent ventricular ejection, and an impaired cushioning function for changes in aortic stiffness and/or diameter has been identified as a key mechanism for target organ damage, including the brain and the heart105. The associations we identified, involving rare coding mutations in the same genes (PLCE1 and COL21A1) linked to heart, aortic and brain structure and function, suggest that similar biological mechanisms may underlie the shared pathways of these organs that influence both cardiac and neurological health.

Associations uniquely identified by singletons and AlphaMissense

Singleton variants are those observed only once in the study cohort. AlphaMissense26 is a recent deep learning-based method that offers a novel approach to annotating damaging missense variants. The Singleton burden model captured the rarest category in our association tests and may be of special interest16,106, and the incorporation of AlphaMissense offered additional genetic findings in our study. Therefore, we would like to highlight the contributions of these two groups of burden models in this section. In our gene-based burden tests, 10 gene-trait pairs would not be detected without the singleton burden models or including AlphaMissense as part of our annotation resources. Among these signals, 8 of them did not even have any counterparts that passed the relaxed P < 1 × 10−8 threshold (Supplementary Data S10).

Singleton damaging missense variants in glutamate-ammonia ligase GLUL, which encodes the glutamine synthetase protein, were associated with functional connectivity of the somatomotor and secondary visual networks (MAF = 0.01%, χ2 = 37.54, 1 df, effect = 2.48 s.d. units, 95% CI = [1.68, 3.27], P = 8.9 × 10−10). GLUL knockout mice were reported to be neuronally affected in multiple regions including somatosensory and visual cortices107. Our singleton analysis provides consistent evidence in human genetics. In addition, a recent study suggested that visual-somatosensory integration may be a biomarker for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease108. Together, rare mutations in GLUL may play a potential role in human neurodegenerative diseases109,110,111,112. Another gene, KCNA5 related to potassium voltage-gated channel, was associated with functional activity in the subcortical-cerebellum network when we combined the rare pLoF variants and Alpha damaging missense variants (MAF = 0.1%, χ2 = 44.21, 1 df, effect = 0.59 s.d. units, 95% CI = [0.41, 0.76], P = 2.9 × 10−11). Notably, voltage-gated potassium channels are essential for neurons and cardiac activities and previous GWAS have discovered the common variants mapped to KCNA5 associated with cortical surface7 and thickness113. In addition, a previous study on the rat cerebellum model revealed strong KCNA5 immunoreactivities in the cerebellar nuclei114. Consistent with these findings, we provided additional evidence for KCNA5’s role in brain function. Moreover, some studies also found close relationships between KCNA5 and heart diseases including atrial fibrillation115 and pulmonary arterial hypertension116. Indeed, KCNA5 is an approved drug target for the treatment of cardiac arrhythmias. Inspired by this additional context, we investigated whether KCNA5 was associated with any CMR traits. Interestingly, we found that when aggregating the singleton pLoF and damaging missense variants, KCNA5 was associated with a regional peak circumferential strain measurement (MAF = 0.02%, χ2 = 21.69, 1 df, effectorg = 5.11%, effect = 1.08 s.d. units, 95% CI = [0.63, 1.54], P = 3.2 × 10−6; “Ecc_AHA_4”, Supplementary Data S1) at a P-value threshold of 1.74 × 10−5 (0.05/2870, Bonferroni adjusted for 82 CMR phenotypes across all the 7 variant function classes and 5 MAF classes). These discussions further suggested that multi-organ imaging genetic studies would bring about insights to the complex interplay across the brain-heart system. In summary, our results underscore the efficacy of our gene-based burden test approach and highlight the importance of using multiple MAF cutoffs and innovative annotation tools.

Comparison with previous ExWAS for brain MRI and CMR traits

In this section, we discuss the links between our gene-based rare variant signals and existing ExWAS results on MRI traits. To our knowledge, there were no rare variant associations reported for brain fMRI or abdominal MRI traits. The studies most similar to ours are those by Backman et al.16, which included regional brain volumes and DTI parameters among a broad range of phenotypes, and Jurgen et al.21, which focused on CMR traits, while Pirruccello et al.117 declared no findings of rare variant associations for aorta traits. Both studies used data from the UKB cohort but with smaller sample sizes compared to our current study. Importantly, we analyzed different brain MRI and DTI parameters, extracted from raw images using our own pipeline, compared to those investigated by Backman et al.16. Additionally, we incorporated a broader set of CMR traits, including strain and thickness metrics, expanding upon the traits analyzed by Jurgen et al.21.

For regional brain volumes and DTI parameters (corresponding to STR and dMRI traits in Backman et al.16), 5 genes (AMPD3, HTRA1, MYCBP2, RBL1, SCUBE2) whose associations passed our stringent P-value threshold (P < 1 × 10−9) were also significantly associated with their brain MRI traits. For example, associations between AMPD3 and mean MD of splenium of corpus callosum passed the stringent P value threshold both in our study and in Backman et al.16. SCUBE2 was significantly associated with the regional volume of the left cerebellum exterior in our analysis, while its association with the volume of the cerebellum cortex in the left hemisphere was reported in their result as suggestive evidence. MYCBP2 was associated with the external capsule in both our analysis and Backman et al.16. Additionally, several associations between PLEKHG3 and multiple dMRI traits were identified in Backman et al.16 and two gene-trait pairs within these associations passed our relaxed threshold (P < 1 × 10−8). For CMR traits, we replicated the only exome-wide significant association between TTN and LVEF in Jurgen et al.21, while their suggestive association between TTN and LVESV also passed our stringent threshold. In addition, we found 7 associations between TTN and 7 peak circumferential strain metrics. We summarized the overlapping associations in these previous ExWAS studies in Supplementary Data S11.

Concordant evidence with GWAS signals

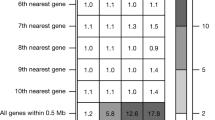

Associations with rare coding variants could prioritize genes among the numerous loci identified in GWAS for polygenic complex traits by providing concordant evidence16,21. In this section, we leveraged the previous GWAS summary statistics1,2,3,10,118 of all the same 596 imaging traits to compare the identified signals between common variants and rare coding variants (Methods). As expected, we observed convergent evidence for all categories of MRI traits. Briefly, more than half of the 174 rare coding signals (53.4% = 93/174, that is, 64/107 variant-trait associations and 29/67 gene-trait pairs) were within the 1 Mb range of the independent GWAS signals, which is consistent with the observation in a previous large-scale UKB phenotype screening16. Based on our results, we found that variant-level associations with regional brain volumes and CMR traits were not within the neighborhood of GWAS signals, while all categories of MRI traits had at least one rare coding association within the 1 Mb of GWAS signal for signals from gene-level tests.

We zoomed into these shared signals between GWAS and ExWAS to provide more detailed insights. The association between SH2B3 and spleen volume identified in our gene-level burden test was further supported by an independent GWAS signal rs2239194, which is an expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) in spleen tissue79. For DTI parameters, two missense variants (rs2652098 and rs143368552) in VCAN contributed the most to the variant-level associations and all these associations were within 1 Mb of the GWAS signals. However, similar to findings from a previous GWAS study47, we did not identify any brain tissue-related eQTLs. Associations between AMPD3 and DTI parameters of splenium of corpus callosum were also accompanied by signals from GWAS. These common variants are eQTLs of multiple brain tissues including cerebellum and spinal cord where brain white matter also presents. For fMRI traits, all the associations between PLCE1 and 18 MRI traits (16 brain fMRI traits and 2 CMR traits) were consistent with previous GWAS results, though there were not eQTLs in brain cortex tissues. On the other hand, we found that the only signal for brain volumes that fell into the GWAS loci was the association between COL21A1 and CSF volume. The corresponding common variants rs3857615 and rs9475654 were eQTLs in cerebellum and cerebellum hemisphere.

In addition, we identified gene-trait associations that were not reported in our previous GWAS of the same MRI traits but appeared in other studies (e.g., RBM20 and LVEF in Pirruccello et al.9). We also observed that some rare coding associations in our study were linked to GWAS loci of related traits within the same phenotype cluster. For example, though both ExWAS and GWAS revealed the associations between TTN and multiple regional peak circumferential strain measurements, the phenotype for the signals did not exactly match. In summary, rare variant associations with MRI traits not only identified novel signals but also prioritized genes among thousands of GWAS loci. These associations provide new insights and context for understanding the genetic basis of structure and function in the human brain and body. We provided these exome-wide signals that showed convergent evidence with previous GWAS signals in Supplementary Data S12 and S13.

Multi-organ imaging genetics and drug targets

We used the Therapeutic Target Database (TTD)119 to query potential drug target genes (Methods). Among the 26 unique genes identified by gene-based burden tests, 6 genes were approved drug targets (KCNA5 and ANO1) or in clinical trials (TTK, GEM, LPAR3, and TNFRSF13B). The identified genes in gene-based burden tests were significantly enriched for potential drug targets (6 out of 26, compared with 1735 out of 17,448 genes, OR = 2.7, P = 0.0391, Supplementary Data S14). Moreover, when including a broader set of potential drug genes that were documented in TTD to be reported in the literature, the enrichment became stronger (13 out of 26, compared with 3468 out of 17,448 genes, OR = 4.0, P = 5.737 × 10−4, Supplementary Data S14). Consistent with the procedure in a previous study61 and observations in other ExWAS16,61,120, our results suggest that rare coding variants identified in imaging genetics may facilitate the discovery of promising drug target genes121,122. Given the complicated nature of human organ interplay and the corresponding biological pathways involved, we would emphasize that such enrichment should be interpreted carefully as they might not directly point to the corresponding diseases and related traits for existing drugs. However, these associations with human organs could provide novel drug targets if they are supported by further evidence, and in turn these MRI traits themselves might be useful to validate the new drugs if the underlying mechanisms are well established123. Moreover, As endophenotypes for complex diseases, MRI traits can offer additional information on known drug targets, such as potential off-targets and/or side effects121,124, and also aid in drug repurposing (e.g., ANO1 and cardiac disease as discussed in the previous section58,59).

Burden heritability and genetic correlation

To investigate the rare coding genetic architecture for multi-organ MRI traits, we applied burden heritability regression (BHR)27 to estimate the heritability for pLoF and damaging missense variants (i.e., “int1 missense variants”, Methods), while the heritability for synonymous variants is also calculated, and it serves as negative control. Designed for rare variants with MAF < 1 × 10−3, BHR stratifies variants based on functional annotation and MAF to allow for different variant classes to have different mean effect sizes. Given our relatively small sample size (average n = 40,038), we restricted our analysis to the ultra-rare MAF bin (MAF < 1 × 10−4) which contained most of the coding variants in our analysis (Supplementary Data S15). As expected, ultra-rare pLoF variants consistently demonstrated higher heritability than damaging missense variants across all MRI categories (Fig. 5A). Supplementary Data S16 and S17 show the complete list of burden heritability for ultra-rare pLoF variants and damaging missense variants. In contrast, there is no evidence that synonymous variants have significant heritability, showing that the estimates from our results for rare variants are well calibrated (Supplementary Data S18). Furthermore, the highest average heritability of ultra-rare pLoF variants were observed in the DTI parameters category. For ultra-rare pLoF variants, the trait had the highest heritability was the caudal anterior cingulate (h² = 0.012, SE = 0.0035) among regional brain volumes, the mean axial diffusivity of the body of the corpus callosum (h² = 0.020, SE = 0.0048) among DTI parameters, functional connectivity between the second visual and auditory networks (h² = 0.020, SE = 0.0047) among brain fMRI traits, regional peak circumferential strain (h² = 0.016, SE = 0.0053) among CMR traits, and pancreas iron (h² = 0.019, SE = 0.0053) among abdominal MRI traits. We note that these burden h² estimates are relatively large, which is similar to the high common variant heritability for many imaging traits. This in general, supports an endophenotype model where genes have more direct connections with imaging phenotypes than downstream health outcomes.

A The distribution of burden heritability point estimates for ultra-rare (minor allele frequency <1 × 10−4) pLoF variants and damaging missense variants (i.e., the int1 damaging missense variants) across 591 multi-organ imaging traits (including 36 abdominal MRI traits, 82 CMR traits, 101 Regional Brain Volumes, 110 DTI traits, 82 resting-state ICA-based fMRI traits, 90 parcellation-based fMRI traits, and 90 parcellation-based fMRI traits) that had a sample size larger than 10,000 (5 abdominal imaging traits were excluded due to insufficient sample size). Burden heritability was estimated based on the summary statistics of each variant-level tests and all the individuals (N = 54,365) were covered. In the boxplots shown, each box represents the distribution of burden heritability estimates across a certain imaging phenotype category for pLoF or damaging missense variant groups. The central line within each box denotes the median value; the upper and lower bounds of the box correspond to the third (Q3) and first (Q1) quartiles, respectively. Whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) from the box, and points beyond the whiskers indicate outliers. The dashed horizontal line marks the null expectation. B Burden genetic correlations of ultra-rare (minor allele frequency <1 × 10−4) pLoF variants for selected imaging phenotypes and other complex traits. P-values are derived from two-sided tests based on z-scores. Only top hits are presented here. Specifically, we first selected seven trait pairs from pairs that had ten smallest P-values among all the trait pairs and additionally included three pairs that had smallest or second smallest P-values for regional brain volumes and abdominal MRI traits, which resulted in nine imaging traits across all MRI categories and seven Genebass traits. Filled circles indicate the selected top hits (P < 0.0032) while filled triangles indicate other pairs that passed a nominal significance threshold at P < 0.05. “Phenotype_ID” was used to define the selected imaging traits. Specifically, abdominal fat ratio from abdominal MRI traits, left atrium maximum volume (LAV_max), regional radial strain (Err_AHA_13) and peak circumferential strain (Err_AHA_4) traits from CMR, left and right insular volumes, functional activity trait from resting fMRI (ICA-based, Net100_Node55) traits, Visual2-Auditory network functional activity trait from task fMRI (parcellation-based), and Somatomotor-Dorsal-Attention network functional activity trait from resting fMRI (parcellation-based) traits were shown here (bottom-to-top order). Supplementary Data S1 includes more details of these phenotypes.

We further explored the burden genetic correlation pattern for ultra-rare pLoF variants between MRI traits (MAF < 1 × 10−4) and 186 complex traits and diseases (MAF < 1 × 10−5) downloaded from Genebass17 (Supplementary Data S19). We focused on 67 heritable MRI traits that passed the Bonferroni adjusted threshold at P < 8.4 × 10−5 (=0.05/596). Consequently, we estimated 12,462 (67 × 186) pairs of burden genetic correlations. We found 3 pairs that passed the MRI-multiple testing threshold at P < 7.5 × 10−4 (0.05/67) and 591 pairs passed a nominal P-value threshold at P < 0.05. Although no pairs survived the most stringent P-value threshold adjusted for both the imaging traits and Genebass traits at P < 4.0 × 10−6 (0.05/12,462), we observed that there were interesting pairs in the top-ranking subset for continuous traits from Genebass (Supplementary Data S20). The results for binary traits can be found in Supplementary Data S21. Figure 5B shows the selected top hits of burden genetic correlation pairs, including insular volume and reaction time125, regional radial strain and systolic blood pressure, left atrium maximum volume and triglycerides to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, and abdominal fat ratio and birth weight. These burden genetic correlations between MRI traits and health-related traits may reveal a shared genetic basis in ultra-rare pLoF variants. While the current MRI sample size was slightly underpowered, future larger samples may enable a more robust quantification and confirmation of these genetic links.

Discussion

We conducted a large-scale ExWAS for 596 multi-organ imaging traits including brain, heart, liver, kidney, and lung. By using both WES and MRI data from over 50,000 participants from the UKB study, we uncovered how rare coding variants contribute to human organ structure and function. The consequences of these rare coding variants to human organs were largely understudied. For example, in abdominal organs, a prior ExWAS focused solely on hepatic fat measurement from CT imaging20, while another GWAS included a broader set of traits13. However, with a relatively limited sample size of over 10,000, it failed to identify rare variant associations. For CMR traits, our study incorporated refined measurements of the left ventricle, right ventricle, ascending/descending aorta, and left/right atrium. These were not examined in previous ExWAS21 but resulted in additional discoveries in our analysis. Additionally, our results helped prioritize genes among previously identified GWAS loci9,10. For brain MRI traits, we analyzed a different set of regional brain volumes and DTI parameters compared to previous ExWAS16,17. Additionally, we discovered associations between rare variants and fMRI traits, which had not been previously reported.

Analyzes at the variant level and gene-based burden level may yield complementary insights into gene associations. For example, gene-based burden testing is more powerful for identifying signals driven by pLoF variants as these variants are rare individually but have consistent effect directions17, while the pattern for missense variants signals in variant-level tests and gene-level tests is less obvious16,17,61. In our study, we found that pLoF signals were exclusively detected by gene-based tests, whereas three gene–trait pairs were observed across both variant- and gene-level analyzes. This pattern aligns with previous findings and underscores the importance of incorporating both approaches. Moreover, although gene-based burden tests can enhance signal detection16,17, annotating the deleterious variants is still an active research area. In group-based tests, variants are collapsed into functional-frequency groups, but different approaches may lead to inconsistent and/or incomplete results126. Therefore, it is helpful to leverage the annotation information from diverse resources to better empower the set-based association test. We incorporated AlphaMissense26 as part of our annotations, resulting in the discovery of an additional set of genes (GOLM1, KCNA5, LPAR3, PIGX, TAGLN, and WIPF3). AlphaMissense is a novel deep learning model for pathogenic missense variant prediction and achieved good performance in predicting the unknown clinical significance of many missense variants.

There is also ongoing research regarding the best practice of performing rare variant association tests. For example, Auer et al.127 pointed out that rare variant associations for quantitative traits might be susceptible to outliers and non-normality and ignoring such issues could result in false discoveries. Although outliers were removed in our pre-processing steps for phenotype data (Methods), there is still potential concern about non-normality. We verified all the identified associations by applying rank-based inverse normal transformation (RINT) (Methods). The results largely supported our original findings (Supplementary Data S22 and S23 and Supplementary Note). Briefly, all associations except one (LPAR3 with the mean MD of uncinate fasciculus) passed the nominal threshold adjusted for the number of signals undergoing RINT analysis (4.7 × 10−4 = 0.05/107 for variant-level tests and 2.2 × 10−4 = 0.05/224 for gene-based burden tests, respectively). The majority of these associations also remained significant under our primary stringent threshold. In addition, Greer et al.128 suggested retaining all the variants before conducting association tests and examining the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium afterward to avoid the over-removal of variants included in the study. We examined the variants filtered out by Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium step in our quality control step and no new discoveries were identified, suggesting that this step had minimal impact on our study (Supplementary Note).

Over half of the identified rare variant signals were within 1 Mb of GWAS common variants. These rare variant associations could prioritize the causal genes among many identified GWAS loci and uncover novel signals. Human organ MRI traits are widely used as endophenotypes for diseases and health-related traits; our rare variant results deepen our understanding from two aspects. First, we showed that many of the identified gene-trait pairs were consistent with existing literature on the associated genes and their links to organ-related diseases or complex traits. This alignment includes findings from previous GWAS and ExWAS, observed clinical outcomes related to these genes, and animal models that elucidate the biological mechanisms connecting the gene to the phenotype. Second, we observed a significant enrichment of potential drug targets among our rare variant signals. This suggests that rare variant imaging genetics can play a role in identifying and repurposing drug targets, as well as understanding potential side effects during drug development. These findings have practical implications for both real-world clinical applications and future scientific research.

Along with these significant new insights, the present study has a few limitations. A primary limitation is the relatively modest sample size for identifying rare variant associations with MRI traits. For example, when the sample size increased from an average of n = 30,739 in the phases 1 to 3 analysis to an average of n = 40,038 in the phases 1 to 5 analysis, we observed a substantial increase in identified signals (84 vs. 174, that is 59 variant-level associations and 25 unique gene-trait pairs in the phases 1 to 3 analysis, and 107 variant-level associations and 67 unique gene-trait pairs in the phases 1 to 5 analysis). It is reasonable to hypothesize that a large number of rare variant associations have not been discovered for many MRI traits. Compared with recent ExWAS studies for other phenotypes encompassing nearly or more than 500,000 participants16,17,21,61,129,130, there remains substantial room for improvement in imaging studies. This is especially important for MRI traits that have a highly polygenic architecture, such as regional brain volumes, and is also critical for simultaneously comparing multiple traits. As the UKB imaging project completes data collection from 100,000 subjects131, we anticipate detecting additional signals and obtaining more robust results. This will not only help identify associated rare coding variants and genes but also elucidate the genetic architecture, such as burden heritability and burden genetic correlation, facilitating downstream analyzes for rare coding variants.

Another limitation is the lack of diversity in imaging ExWAS data resources. First, no independent non-UKB database currently exists that combines both MRI traits and WES data in a sample size comparable to the UKB study. As discussed above, rare variants typically require a large sample size for detection and replication. Although our study leveraged the largest available dataset and had enhanced statistical power, we were unable to perform independent non-UKB replications because many rare variants may not be observed in smaller samples. Consequently, this led us to use joint analysis with a stringent P-value cutoff, and an internal validation procedure to assess the robustness of our findings. Nonetheless, future independent studies with more diverse data resources are essential to replicate the signals we identified. Second, our analysis primarily focused on individuals of European ancestry. It is critical to extend these studies to underrepresented ancestry groups in genetic research as data become available. Different ethnicities may exhibit heterogeneous genetic architectures, and including a diverse range of ancestries could provide a more comprehensive understanding of genetic influences on organ structure and function. When future data resources become available, it will be valuable to replicate our findings and extend the scope of WES studies across multiple cohorts. Meta-analysis may be a robust and efficient approach for identifying and replicating associations using only summary statistics.

In conclusion, we have identified associations between rare coding variants and imaging traits across human organs. These findings enhance our understanding of the genomic mechanisms underlying human organ structure and function from the perspective of protein-coding variants, potentially contributing to the identification and prioritization of novel targets for pre-clinical and clinical drug development. Compared with GWAS of similar sample size (at the scale of 50,000) to our study, the identified associations are much fewer partially due to the limited statistical power induced by the low frequency of the protein-coding variants17,18,61. However, rare coding variants offer more direct and stronger effects with interpretable biological implications, which would contribute to complementary genetic information with common variants, prioritize the effector genes, and elucidate the underlying mechanisms between gene-trait pairs. Looking ahead, it is important to increase sample sizes, integrate data from diverse populations, and expand ExWAS to include a broader spectrum of imaging phenotypes. We anticipate that future collaborative efforts will further elucidate the genetic landscape of human organs, advancing our knowledge of human biology and health.

Methods

Ethics and data resources

This study made use of the data from UK Biobank (UKB) involving ~500,000 participants aged from 40 to 69 when recruited between 2006 and 2010 (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/). The UKB study received the ethics approval from the North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (reference number: 11/NW/0382) with informed consent obtained by all the participants. The present study was under UKB application number 76139.

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) data were obtained from the UK Biobank and the detailed sequencing protocols can be found elsewhere18. By following a unified OQFE protocol121, raw sequencing reads were aligned to the GRCh38 reference genome, and small variants were called on a per-sample basis using DeepVariant. Per-sample gVCFs were then joint-genotyped using GLnexus to produce multi-sample project-level VCFs (pVCF) suitable for association analysis. We made use of the OQFE WES files in BGEN format provided by UK Biobank after these centrally pre-processing steps.

Multi-organ imaging phenotypes

The information of imaging phenotypes can be found in previous studies1,2,3,4,10. Briefly, we studied 596 imaging traits encompassing brain MRI traits1,2,3,4, heart CMR traits10, and abdominal MRI traits. Three major modalities of brain MRI were included. First, we included 101 regional brain volume traits1 derived from structural MRI. Second, we used 110 tract-averaged parameters2 from DTI capturing the microstructure of brain white matter. Third, for fMRI traits, we involved 76 node amplitude traits and six global functional connectivity traits based on ICA3 as part of resting fMRI traits; we also included 180 (90 + 90) parcellation-based4,95 resting fMRI traits and task fMRI traits. Regarding CMR traits, we made use of 82 traits10 including regional and local measurements from cardiac chambers and the aorta. For abdominal MRI traits, we contained 41 imaging traits based on MRI data of the liver, kidneys, lungs, pancreas, spleen, and body muscle/fat composition. For each phenotype, values greater than five times the median absolute deviation from the median value were removed as in our previous work1,2,3,4,10. A full list of these 596 traits can be found in Supplementary Data S1.

Internal replication and joint analysis design

Given the limited sample size (average n = 40,038 across imaging traits with non-missing data) and lack of independent data sources, we prioritized our signals through joint analysis30 and adopted an internal validation procedure to evaluate the robustness of our discoveries. Specifically, we first restricted our sample to include only participants from phases 1 to 3 of MRI release (average n = 30,739) and then excluded any individuals related to phases 1 to 3 participants in the rest of the sample from phases 4 to 5 of MRI release (average n = 8,989, relatives of the phases 1 to 3 were removed). The joint sample included all the individuals from phases 1 to 5 and was used to report significant results. To investigate the robustness of variant-level associations, we tested the associations on phases 1 to 3 individuals and phases 4 to 5 individuals separately. Then, focusing on the significant level and effect sign, we investigated (i) whether signals identified from the phases 1 to 3 sample could be replicated in the independent phases 4 to 5 sample and (ii) whether the signals identified from phases 1 to 3 sample had stronger evidence (i.e., smaller P values and concordant effect directions) in the joint sample. For gene-based burden tests, we noted that many rare mutations, especially those variants with MAF < 1 × 10−4, accounted for a large proportion of our discoveries but were not observed in the smaller independent dataset from phases 4 to 5 (average n = 8989; even within a burden model with MAF cutoff at 0.01, the lack of those rare variants in the sample from phase 4 to phase 5 would make the burden associations incomparable). Thus, we only investigated whether the identified associations from phases 1 to 3 dataset had stronger evidence in the joint sample. Consequently, based on this internal replication procedure, we were able to expect the level to which our discoveries from the joint analysis could be replicated.

Quality control for UK Biobank exome data

We used Plink v.2.0132 to conduct the quality control steps, restricting the sample to individuals with imaging data (n = 54,365). For exome sequencing data, we included all the variants that had a MAF below 0.01. Variant-level quality control excluded all the variants that had missing rate larger than 10% or had Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium P < 1 × 10−15. Sample-level quality control excluded any sample with missing rate over 10%. Consequently, no individual was excluded from the quality control process, while 8,127,841 variants remained for the downstream analyzes before annotation.

Functional annotation for protein-coding variants

We used Variant Effect Predictor133 (VEP v.108) for variant annotation. Each variant was mapped to the most severe consequence across the canonical transcripts. We defined the loss-of-function variants using the Loss-of-Function Transcript Effect Estimator134 (LOFTEE) plugin, which further collapsed stop-gained, essential splice, and frameshift variants into high-confidence predicted loss-of-function variants (hcpLoF or pLoF hereafter) or low-confidence predicted loss-of-function variants (lcpLoF). Missense variants were prioritized by dbNSFP135,136 (v.4.5a) plugin using five prediction algorithms16: SIFT22, PolyPhen2 HDIV23, PolyPhen2 HVAR23, LRT24, and MutationTaster25. Missense variants were defined as “int5 damaging missense variants” if predicted damaging or possible damaging by the intersection of all the five algorithms and “int1 damaging missense variants” if predicted damaging or possible damaging by any one of the five algorithms. Parallelly, we also used AlphaMissense26 to assign the missense variants to be “Alpha damaging” if predicted as “pathogenic”. Synonymous variants served as empirical null control to support the study-wise P-value threshold for burden tests and the method would be detailed below in the section for determining study-wise significance level. Predicted loss-of-function variants (including both hcpLoF and lcpLoF) and missense variants were included in our downstream association tests. They were referred to as non-synonymous variants or coding variants of interest (n = 2,143,707).

Exome-wide association tests

The covariate adjustment for brain MRI, DTI parameters, brain fMRI, and heart CMR traits was consistent with our previous GWAS1,2,3,10,118. In short, we adjusted a set of basic covariates for all the imaging traits including age (at imaging), age-squared, sex, age-sex interaction, age-squared-sex interaction, imaging site, and the top 40 genetic PCs (for the phases 4 to 5 sample replication analysis, we only adjusted for top 10 genetic PCs). For brain structural MRI traits, we additionally adjusted for total brain volume (for traits other than itself). For brain fMRI traits, we additionally adjusted for the effects of volumetric scaling, head motion, head motion-squared, brain position, and brain position-squared. For heart CMR traits, we additionally adjusted for the effects of standing height and weight. For abdominal MRI traits137, we additionally adjusted for the effects of standing height and body mass index.