Abstract

While most approaches to polariton research focus on achieving strong coupling between excitons in monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) and external microcavities, bulk TMDCs have been largely overlooked due to their reduced exciton oscillator strength and indirect bandgap nature. Here, we report the observation of polariton condensation within the indirect-transition range, enabled by a condensation mechanism in 50-nm-thick WS₂-based bound state in the continuum (BIC) cavities. Our photonic-like BIC polaritons exhibit a significant Rabi splitting energy ( ~ 294 meV) and clear evidence of condensation driven by a mechanism involving indirect excitons that directly inject photons into BIC polaritons. Remarkably, the interaction-induced confinement of polariton condensates can be optically tuned by adjusting the pump laser size, despite a minimal exciton fraction of 6%, distinguishing this system from purely photonic counterparts. These findings open new avenues for exploring polariton physics with indirect excitons in TMDCs and other emerging materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exciton cavity polaritons (polaritons) are interacting bosonic quasi-particles with tunable relative fractions between excitons and photons. Polaritons are advantageous for studying bosonic condensation, opening pathways from the fundamental physics of quantum coherent gases1,2,3 to applications in quantum photonic devices4,5,6. The primary challenge in polariton research, however, has been achieving a high-quality cavity7 that supports both polariton formation and polariton condensation. Traditionally, most cavity structures rely on distributed Bragg reflectors (DBRs), which require precise and time-consuming fabrication processes. Recently, bound states in the continuum (BIC) cavities8,9 have attracted growing attention, as they exhibit high Q-factors even without a multilayered DBR structure. Recent studies have demonstrated polariton condensation in GaAs quantum wells10 at cryogenic temperatures and in perovskite-based systems11 at room temperature.

Transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), van der Waals semiconductors with large exciton binding energies and strong oscillator strengths, are among the most actively studied materials for room-temperature polariton research. While polariton formation has been successfully demonstrated in monolayer or bilayer TMD structures12,13,14,15, achieving polariton condensation in these layers remains challenging. The limited number of excitons in a monolayer makes polariton condensation highly sensitive to detuning, impacting the efficiency of polariton scattering to the ground state. Recent discoveries have shown that multilayered TMDs—typically indirect bandgap materials—can exhibit larger Rabi splitting energies16,17 due to the expanded exciton wavefunction volume. However, the potential of multilayer TMDs remains largely unexplored; for instance, very recently, unexpected lasing behavior has been observed in multilayered TMD cavities18.

Here, we introduce the observation of photonic-like polariton condensation using multilayered WS2-based BIC cavities via the condensation mechanism involving indirect excitons. Multilayered WS2 layers exhibit unique optical properties, including a high refractive index (n > 4) and near-zero loss in the indirect bandgap transition range, enabling the formation of high-quality BIC cavities without any external cavity structure. This approach results in “BIC polaritons” with only a 6% exciton fraction and substantial vacuum Rabi splitting energy ( ~ 294 meV). Unlike conventional condensation mechanisms initiated from direct exciton reservoirs, this new condensation mechanism involving indirect exciton reservoirs enables direct photon injection into the BIC polaritons, bypassing the need for polariton relaxation along the polariton branches. Through this approach, we observed the room temperature polariton condensate with clear evidence. Notably, even with only a few percent of exciton fraction, the confinement of polariton condensates is directly controlled by adjusting the optical pumping size, distinguishing this system from pure photon lasing systems. Unlike conventional polariton systems, our unique polariton system with indirect exciton reservoir allows for polariton condensate independent of precise photon energy detuning and exhibits unexpectedly strong interaction. This work establishes a distinctive polariton system mediated by indirect excitons, offering new avenues for enhancing polariton interactions.

Results

Condensation mechanism via indirect excitons

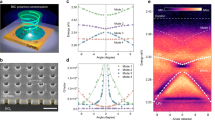

We have designed and fabricated BIC polariton structures based on ultra-thin WS2 multilayers. Figure 1a shows a 3D schematic of the 2D BIC polariton condensate emitting vortex beam based on WS2 multilayers. Recently, ultra-thin nanophotonic structures, such as waveguide19,20, optical cavity18, modulator21, metasurface17, based on TMD multilayers have been actively studied due to their high refractive index. This structure consists of a 50 nm-thick WS2 multilayer film with periodic nanohole patterns. This nanostructured design enables the formation of BIC modes and allows for manipulating polariton characteristics.

a 3D schematic of multilayered WS2-based BIC polariton structure emitting vortex beam. b Calculated photon and polariton band structure of multilayered WS2, illustrating the relaxation process, including both direct and indirect excitons. c Corresponding PL spectrum for WS2 multilayers, showing emissions related to both direct and indirect exciton.

Figure 1b shows the calculated photon and polariton band structure of multilayered WS2, along with the band schematic of the relaxation process that includes both direct and indirect excitons. The black solid line represents the direct exciton reservoirs, while the black dashed line indicates the indirect exciton reservoirs (see below). The red dashed lines and blue solid lines show the photonic modes and corresponding lower polariton bands, respectively, resulting from the strong coupling between the direct exciton and the photonic modes. In contrast, the indirect exciton, which has a very weak coupling with photon, does not lead to strong coupling with the photon modes. Here, multilayered WS2 exhibits a distinctive photoluminescence (PL) spectrum with emissions related to both direct and indirect excitons (see Fig. 1c). Optical pumping initially excites electrons to the direct bandgap, generating direct excitons. Simultaneously, these excited electrons relax into the indirect bandgap due to phonon interactions, forming inter-valley dark exciton22,23 or ‘indirect excitons’. Remarkably, these indirect excitons transitions allow photons to be directly injected into BIC polariton far-detuned from exciton resonance, ignoring complex polariton branches located in near the direct exciton energy level. This is the key principle of the condensation mechanism of our system, allowing direct photon injection into polaritons, which differ from the conventional condensation mechanism involving direct exciton reservoirs going through complex intersubband transition. Hence, this new mechanism enables room-temperature polariton condensation without precise photon energy detuning.

Generation of BIC polariton in multilayered WS2

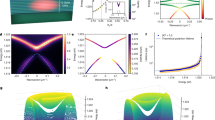

To induce the coupling of indirect excitons into a BIC polariton, we precisely designed a BIC mode in the indirect exciton transition range through Finite-Difference Time-Domain (FDTD) simulations. The optimized thickness, period, and diameter of the nanoholes are set to 50 nm, 480 nm, and 140 nm, respectively. The inserted scanning electron microscope (SEM) image shows the fabricated structure of the multilayer WS2 BIC cavity (scale bar 500 nm). We compared the angle-resolved reflection spectrum calculated through FDTD simulation with the experimentally measured angle-resolved photoluminescence spectrum (Fig. 2a). The simulation results (left) and experimental results (right) showed excellent agreement. In particular, the dark spot appearing in the lower polariton branch at E ≈ 1.43 eV corresponds to the polariton BIC. The red dashed line represents the photonic BIC band without exciton oscillator, while the blue dashed line indicates the polariton branch calculated using the coupled oscillator model (see Supplementary Section 1 for details). The results regarding calculated dispersions are also in excellent consistency with the measurements. The deduced Rabi splitting energy is as large as 294 meV, significantly exceeding the 37 meV typically observed in monolayer-based DBR polaritons24. This indicates that the direct excitons in multilayered WS₂ still retain a strong oscillator strength. Furthermore, deduced Hopfield coefficients indicate the exciton fraction ( | X | 2) of ~6% and the photon fraction ( | C | 2) ~ 94% for the lower BIC polariton (see Supplementary Section 1), confirming the formation of a far-detuned BIC polariton from exciton resonance as intentionally designed in our system. To rigorously confirm the polariton formation, we verified the characteristic bending of the lower polariton branch near the exciton resonance energy in both the PL spectra (see Supplementary Section 2) and the reflectance spectra (see Supplementary Section 3).

a Angle-resolved spectra of FDTD simulation (left) and experiment (right) for multilayered WS2 BIC cavity. Blue and red dashed lines for polariton and photon, respectively. Inset: the scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of the fabricated multilayered WS2 BIC cavity. Scale bar, 500 nm. b Side views of the magnitude of electric field profiles (x component) of the at-Γ BIC [kx = 0°] and off-Γ mode [kx = 3°]. c Q- factor of the BIC mode as a function of kx. Inset: the normalized electric field in the x and y directions on the surface of a unit cell. d Simulated azimuthal angle map of state of polarization on BIC mode. Measured polarization-resolved monochromatic image (1.43 eV) in k-space.

Figure 2b shows a cross-sectional view of the magnitude of the transverse electric field mode profiles along the x-axis for the BIC mode [kx = 0°] at the Γ point and guided mode resonance at the off-Γ point [kx = 3°]. In the BIC mode, the electric field is strongly localized within the structure, while in the guided mode resonance, the electric field leaks out from the structure. To verify the formation of BIC, we deduced the Q-factor as a function of kx, which is shown in Fig. 2c. A sharp increase in the Q-factor is observed at kx = 0, due to the suppressed radiation loss of the BIC mode. The inserted images show the normalized electric field distribution with x and y direction on the unit cell surface, demonstrating both symmetry-protected BIC characteristics (Fig. 2b) and strong field localization within the WS2 material. The combination of robust oscillator strength and strong electromagnetic field localization in the patterned WS₂ contributes to the significantly enhanced Rabi splitting energy of 294 meV, which is comparable to the values observed in self-hybridized BICs in van der Waals metasurfaces17.

The BIC feature was further confirmed by examining the polarization state near the BIC mode. Figure 2d (top) shows a simulated azimuthal map of the polarization state, demonstrating that the BIC mode exhibits vortex characteristics10,25, consistent with the theoretical features of BIC. Furthermore, the experimental monochromatic image in k-space is closely aligned with the polarization vortex (Fig. 2d, bottom). We emphasize that the BIC modes are positioned within the indirect exciton-related emission range, which minimizes not only radiative loss but also the exciton absorption loss due to the small relative fraction of direct exciton; it enables a high Q-factor and long polariton lifetimes, crucial factors in realizing polariton condensation at room temperature.

Evidence of photonic-like polariton condensate

To explore a high-Q BIC microcavity, we examined the power-dependent energy-momentum dispersion along kx under femtosecond pulsed laser excitation with a beam size of 5 μm. The light-in–light-out curve of the BIC polariton intensity, deduced around kx = 0, shows clear but weak nonlinear emission in the polariton condensation regime (Fig. 3a, top). Angle-resolved measurements were compared below (Fig. 3b) and above (Fig. 3c) the condensation threshold (Pth). Below Pth, emission is uniformly distributed across the entire polariton branch. Above Pth, strong emission is concentrated near kx = 0, corresponding to the BIC region, accompanied by weaker background emission from the residual polariton band.

a Light in-light out curve around k = 0 (top), Blueshift (middle) and full width of half maximum (bottom) in the function of corresponding pump power. Experimental energy-momentum dispersion crosscut along kx at (b). below condensation threshold, c above condensation threshold. Real-space g(1) images above the threshold: d non-interfered image (single arm) and e interfered image (double arm).

Notably, the residual polariton band’s light-in–light-out curves show sub-linear behavior at high angles, transitioning to super-linear behavior near the BIC region (see Supplementary Section 4 for details). This transition is a clear signature of stimulated scattering driven by the bosonic final state occupancy above the threshold, leading to an accelerated scattering rate. In our case, the relatively weak and low-contrast condensation emission is attributed to a low scattering rate. In general, stimulated scattering is governed by two primary mechanisms: polariton-phonon scattering (WLP-ph) and polariton-polariton scattering (WLP-LP)26. These scattering rates depend on the exciton fraction (|X|2) as follows:

\({W}_{{LP}-{ph}} \sim {{|X|}}^{4},{W}_{{LP}-{LP}} \sim {{|X|}}^{8}\)

In our system, the small |X|2 (~6%) leads to intrinsically weak stimulated scattering. Remarkably, such a photonic-like polariton condensate has rarely been explored before because it typically requires an extremely high threshold power in conventional condensation schemes.

To elucidate this behavior, we employed a semi-classical Boltzmann-rate-equation approach, which revealed that the residual band arises as the excitonic fraction decreases owing to the weak stimulated scattering combined with the short polariton lifetime (see Supplementary Section 5 for details). Despite this limitation, the system exhibits clear evidence of a photonic-like polariton condensate, as described below.

The spectral peak shift (blue square) exhibits a blue shift of ~1.6 meV in our photonic-like polariton condensation regime (Fig. 3a, middle), which is unexpectedly large considering our system’s small excitonic fraction. Remarkably, this blue shift magnitude is significantly larger than that observed in conventional DBR-based WSe2 monolayer polariton systems27 (0.5 meV), which have a much higher excitonic fraction (94%), despite our system being predominantly photonic (see Discussion). The linewidth shows a decrease followed by an increase after Pth (Fig. 3a, bottom) owing to the interaction of polaritons28. This behavior contrasts with the redshift and linewidth narrowing observed in previous study of indirect bandgap lasing in ultrathin WS2 microdisk18. A detailed comparison between the whispering gallery mode cavity and BIC mode system is provided in the discussion below.

To verify the long-range spatial coherence of the polariton condensate, we performed real-space g(1) imaging above Pth using a retro-reflector in both the single-arm (Fig. 3d) and double-arm (Fig. 3e) configurations. In the single-arm configuration, no interference fringes were observed even above Pth, whereas the double-arm configuration exhibited a clear interference pattern. From the interference image, the extracted spatial coherence length was 4.85 µm, which is comparable to the laser pump diameter (5 µm) (see Supplementary Section 6). This long-range spatial coherence is a key characteristic of the BIC-polariton condensate and provides strong evidence for the formation of the condensate and its quantum nature.

From the cavity-photon-energy detuning study (see Supplementary Section 7), we find that the photonic-like polariton condensate persists over a detuning range of at least ~100 meV, demonstrating that precise tuning of the cavity photon energy is not required. Importantly, this new condensation mechanism, mediated by the indirect-exciton reservoir, enables access to the photonic-like polariton-condensate regime.

Optical controllability of BIC polariton condensate

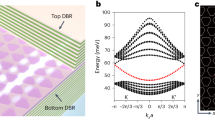

Furthermore, we investigated an additional unique characteristic of the polariton condensate, distinct from photon lasing: the ability to control the polariton potential via optical pumping. It is well known that the Gaussian profile of the pump laser induces a polariton potential hill due to the power-dependent blue shift of the polariton condensate. In a conventional polariton system, such as DBR-based polaritons, polaritons have a positive effective mass and spread out from the potential hill29,30. In contrast, our 2D BIC polariton band structure is uniquely designed with a negative effective mass, leading to the opposite behavior under the same potential hill: polariton confinement31,32. To explore the polariton confinement under optical pumping, we adjusted the size of the Gaussian-profiled c. w. pump laser, as shown in Fig. 4a. The distribution of exciton reservoir, both direct exciton and indirect exciton, was observed to closely match the pump laser profile, enabling the generation of potential energy gradient.

a Gaussian-profiled femto pulsed laser with varying sizes—2.6 μm, 3.8 μm, and 4.8 μm—used to control lateral confinement of the condensate. b Energy-space resolved image showing the trapped states: M0, the ground state, and M1, the first excited state. c Energy level spacing (\({{\hslash }}\omega\)) between M0 and M1 in the function of diameter of pump laser. Dashed line and scatters for calculation and experiment, respectively.

The energy-space resolved measurements above Pth (Fig. 4b) reveal two discrete quantum confinement states: a ground state (M0), with symmetric double peaks at a higher energy level, and a first excited state (M1), displaying triple peaks with strong central emission. The symmetric double peak at the ground state is due to the vortex nature of the BIC mode, distinct from to the polariton quantum vortex33.

Importantly, the spatial profiles observed in the near field directly reflect the condensate wavefunctions, whereas the far-field emission patterns are shaped by the radiative coupling of polaritons leaking out of the BIC cavity. As a result, the M0 mode exhibits a donut-shaped far-field profile owing to destructive interference at k = 0, even though its near-field density has Gaussian-like profile without a central singularity. In contrast, the M1 mode shows a double-peak structure in the near field but yields a triple-peak pattern with strong central emission in the far field, reflecting the distinct radiative coupling of this excited state. Thus, the difference between the near-field and far-field distributions highlights the intrinsic BIC radiative properties rather than changes in the underlying condensate density.

This quantized modal structure can be further tuned by adjusting the pump-laser diameter, ranging from 2.6 μm to 4.8 μm, which effectively tailors the lateral confinement potential of the condensate. The energy spacing between M0 and M1 closely follows the prediction of the quantum harmonic oscillator34:

where \({{\hslash }}\) is the reduced Planck constant and \(R\) is the diameter of pump laser. The effective mass of the polaritons, \({m}_{{pol}}^{*}\), extracted from the angle resolved spectra, is approximately 7.8×10-6me, where me is the free electron mass. The potential well depth, V, is estimated to be 11 meV, which exceeds the value obtained in momentum space. This discrepancy arises from the influence of space-resolved high local polariton density in real space, differing from the space-integrated blueshift observed in momentum space. The calculated energy level spacing are also in excellent consistency with the experimental data, as presented in Fig. 4c. This simple Gaussian pumping allows optical control over the energy levels of the trapped polariton condensate (see Supplementary Section 8). It is worth noting that this photonic-like polariton condensate, with exciton fraction of just a few percent, provides excellent controllability even, unlike conventional photonic system where such control is challenging due to a lack of interaction.

Discussion

In summary, we have achieved the generation of photonic-like BIC polaritons exhibiting substantial Rabi splitting, attributed to the large spatial overlap between excitons and photons and the robust oscillator strength present in multilayered WS2. Utilizing a novel condensation mechanism mediated by indirect excitons, we observed a photon-like polariton condensate at room temperature with clear experimental signatures, including nonlinear emission, spectral blueshift, changes in linewidth, and long-range order of spatial coherence. The key distinction between the redshift observed in whispering gallery mode system and the blueshift observed in BIC mode system lies in the negative effective mass of the BIC modes, despite both microcavity systems supporting strong coupling and featuring a low excitonic fraction at the indirect bandgap transition energy. The high Q-factor of the BIC mode, combined with the negative mass, ensures a high local polariton density, facilitating strong nonlinear polariton interactions. Hence, we demonstrated the controllability of energy states of trapped polariton condensates by adjusting the pump laser size, a feature distinguishing it from conventional photonic systems.

We stress that our results experimentally reveal an unexpectedly strong polariton nonlinearity under non-resonant pumping measurement, gpol-pol-IX = 0.026 ± 0.001 μeV · μm2 (see Supplementary Section 9), which is approximately two orders of magnitude larger than the previous report (gpol-pol)13 on monolayer WS2 integrated with BIC at a similar excitonic fraction. This enhanced nonlinearity enables optical controllability even at a very low excitonic fraction ( ~ 6%). Typically, polariton blueshift arises from both polariton-polariton and exciton reservoir-polariton interactions. To determine the origin of the blueshift in our system, we performed resonant pumping measurements, which exclude both direct- and indirect exciton reservoir-polariton interactions (see Supplementary Section 10 for details). The negligible blueshift observed under resonant pumping confirmed that polariton-polariton interactions (gpol-pol) alone are not dominant in the absence of the indirect excitons reservoir. We also verified that nonlinear phase-space filling is negligible (see Supplementary Section 11). These findings indicate that this enhanced polariton nonlinearity in our system is primarily mediated by the indirect exciton reservoir.

Given the indirect bandgap nature of WS2, it is likely that indirect exciton reservoir-polariton interactions play a significant role. We hypothesize that the large density of indirect excitons, accumulated due to their substantially long lifetime, could be responsible for this unexpected interaction strength. A rigorous theoretical modeling that incorporates both direct excitons and indirect excitons will be necessary to fully understand this phenomenon. Since existing polariton theories primarily focus on direct bandgap material, we believe that these findings will inspire new theoretical approaches involving indirect excitons.

Finally, our results highlight the potential for practical applications, as this nonlinear behavior is achieved at a polariton-condensate wavelength of 850 nm, which is ideally suited for optical interconnects.

Method

Sample fabrication

A 50 nm-thick WS2 flake was transferred onto a silica substrate (see Supplementary Section 12 for quantum yield of IX-related emission). The BIC cavity was patterned using electron beam lithography (ELS-BODEN, ELIONIX, acceleration voltage: 50 kV, beam current: 1 nA) with a positive photoresist (ZEP 520 A, ZEON). The exposed patterns were then developed using n-Amyl acetate developer (ZED-N50, ZEON) at 0 °C for 1 minutes. Subsequently, the patterned photoresist served as an etch mask to transfer patterns into the WS2 layer through a dry etching process (CF4 40 s.c.c.m., O2 10 s.c.c.m., 30 W, 50 mtorr, 1 min). Finally, the patterned WS2 BIC cavity was encapsulated with spin-on-glass (NDG-2000, Desert Silicon) to achieve index matching with the silica substrate and to enhance the mechanical and thermal stability of the WS2 BIC cavity (see Supplementary Section 13 for OM image). The spin-on-glass was spin-coated onto the patterned WS2 BIC cavity at 2000 rpm for 60 seconds, followed by thermal annealing at 300 °C for 1 h.

Experimental set-up

Measurements were taken using a homemade microscopy set-up at room temperature. We designed and implemented a reconfigurable 8 f to 9 f optical configuration for far-field observation. Excitation of the sample was achieved using a 594 nm continuous-wave diode laser source. The optical system incorporated a 40× objective lens (N. A. 0.95) for both laser excitation and emission collection. A beam expander was utilized to control the pumping spot size. The detection scheme employed a > 600 nm long-pass filter to eliminate the excitation laser, followed by spectral analysis using a PIXIS-400BX detector (Princeton Instruments) coupled to a spectrometer. Wavelength-selective imaging of condensation phenomena was facilitated by an adjustable band-pass filter system. Spectroscopic measurements were performed using an HRS-300 spectrometer (Princeton Instruments) equipped with a 1200 g mm−1 diffraction grating. For k-space investigations, we selected the central emission region through a spectrometer entrance slit. Vortex characterization in k-space was accomplished through polarization control. The spatial filtering of emission near k = 0 was implemented using an iris placed at the far-field plane within the 4 f configuration. Long-range spatial coherence measurements (g(1)) were conducted using a custom Michelson interferometric setup, incorporating a cube-type 50:50 beam splitter and mirror arrangement.

Mode simulation

The dielectric function of 50 nm WS2, obtained using the Lorentz oscillator model is represented by following equations.

The background permittivity (ϵ0) and oscillator strength (f0) were adjusted to 9.54 and 0.4, respectively, to match experimental measurements. We used known values for the exciton resonance energy (\({\omega }_{{\rm{ex}}}=1.96{\rm{eV}}\)) and damping constant (γex = 0.09 eV). To compare polariton BIC and photon BIC, we performed reflectance simulations using a 3D finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulator (Lumerical) with and without the exciton oscillator in the dielectric function. The design and analysis of the BIC cavity were performed using finite element method (FEM) simulations. All numerical calculations were carried out using the commercial software COMSOL Multiphysics 5.2, specifically employing its eigenfrequency solver module. The computational domain consisted of a three-dimensional space with dimensions of 480 nm × 480 nm × 3 μm along the x, y, and z axes, respectively. Periodic boundary conditions were implemented along both the x and y directions, with a periodicity of 480 nm to simulate the extended structure.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study, including all source data for the main figures, have been deposited in Figshare and are publicly available at the following link: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30655754.

References

Kasprzak, J. et al. Bose-Einstein condensation of exciton polaritons. Nature 443, 409–414 (2006).

Balili, R., Hartwell, V., Snoke, D., Pfeiffer, L. & West, K. Bose-Einstein condensation of microcavity polaritons in a trap. Science 316, 1007 (2007).

Deng, H., Weihs, G., Santori, C., Bloch, J. & Yamamoto, Y. Condensation of semiconductor microcavity exciton polaritons. Science 298, 199–202 (2002).

Zasedatelev, A. V. et al. Single-photon nonlinearity at room temperature. Nature 597, 493–497 (2021).

Berloff, N. G. et al. Realizing the classical XY Hamiltonian in polariton simulators. Nat. Mater. 16, 1120–1126 (2017).

Liu, W. et al. Generation of helical topological exciton-polaritons. Science 370, 600–604 (2020).

Ballarini, D. et al. Macroscopic two-dimensional polariton condensates. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118 (2017).

Kodigala, A. et al. Lasing action from photonic bound states in continuum. Nature 541, 196–199 (2017).

Hsu, C. W. et al. Observation of trapped light within the radiation continuum. Nature 499, 188–191 (2013).

Ardizzone, V. et al. Polariton Bose-Einstein condensate from a bound state in the continuum. Nature 605, 447–452 (2022).

Wu, X. et al. Exciton polariton condensation from bound states in the continuum at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 15, 3345 (2024).

Barachati, F. et al. Interacting polariton fluids in a monolayer of tungsten disulfide. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 906–909 (2018).

Maggiolini, E. et al. Strongly enhanced light-matter coupling of monolayer WS(2) from a bound state in the continuum. Nat. Mater. 22, 964–969 (2023).

Kravtsov, V. et al. Nonlinear polaritons in a monolayer semiconductor coupled to optical bound states in the continuum. Light Sci. Appl. 9, 56 (2020).

Zhao, J. et al. Exciton polariton interactions in Van der Waals superlattices at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 14, 1512 (2023).

Shin, D. J., Cho, H., Sung, J. & Gong, S. H. Direct observation of self-hybridized exciton-polaritons and their valley polarizations in a bare WS(2) layer. Adv. Mater. 34, e2207735 (2022).

Weber, T. et al. Intrinsic strong light-matter coupling with self-hybridized bound states in the continuum in van der Waals metasurfaces. Nat. Mater. 22, 970–976 (2023).

Sung, J. et al. Room-temperature continuous-wave indirect-bandgap transition lasing in an ultra-thin WS2 disk. Nat. Photonics 16, 792–797 (2022).

Lee, S. W., Lee, J. S., Choi, W. H. & Gong, S. H. Ultrathin WS2 polariton waveguide for efficient light guiding. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11 (2023).

Lee, H. S., Sung, J., Shin, D.-J. & Gong, S.-H. The impact of hBN layers on guided exciton–polariton modes in WS2 multilayers. Nanophotonics 13, 1475–1482 (2024).

Lee, S. W., Lee, J. S., Choi, W. H., Choi, D. & Gong, S. H. Ultra-compact exciton polariton modulator based on van der Waals semiconductors. Nat. Commun. 15, 2331 (2024).

Liu, E. et al. Multipath Optical Recombination of Intervalley Dark Excitons and Trions in Monolayer WSe_2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 196802 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Momentum-dark intervalley exciton in monolayer tungsten diselenide brightened via chiral phonon. ACS Nano 13, 14107–14113 (2019).

Zhao, J. et al. Ultralow threshold polariton condensate in a monolayer semiconductor microcavity at room temperature. Nano Lett. 21, 3331–3339 (2021).

Doeleman, H. M. et al. Experimental observation of a polarization vortex at an optical bound state in the continuum. Nat. Photonics 12, 397–401 (2018).

Deng, H., Haug, H. & Yamamoto, Y. Exciton-polariton Bose-Einstein condensation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1489–1537 (2010).

Shan, H. et al. Spatial coherence of room-temperature monolayer WSe(2) exciton-polaritons in a trap. Nat. Commun. 12, 6406 (2021).

Song, H. G., Choi, M., Woo, K. Y., Park, C. H. & Cho, Y.-H. Room-temperature polaritonic non-Hermitian system with single microcavity. Nat. Photonics 15, 582–587 (2021).

Song, H. G. et al. Tailoring the potential landscape of room-temperature single-mode whispering gallery polariton condensate. Optica 6 (2019).

Wertz, E. et al. Spontaneous formation and optical manipulation of extended polariton condensates. Nat. Phys. 6, 860–864 (2010).

Gianfrate, A. et al. Reconfigurable quantum fluid molecules of bound states in the continuum. Nat. Phys. 20, 61–67 (2024).

Riminucci, F. et al. Polariton condensation in gap-confined states of photonic crystal waveguides. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 246901 (2023).

Kwon, M. S. et al. Direct transfer of light’s orbital angular momentum onto a nonresonantly excited polariton superfluid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 045302 (2019).

Tosi, G. et al. Sculpting oscillators with light within a nonlinear quantum fluid. Nat. Phys. 8, 190–194 (2012).

Acknowledgements

J.R. acknowledges the POSCO-POSTECH-RIST Convergence Research Center program funded by POSCO, and the National Research Foundation (NRF) grant (RS-2024-00356928) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) of the Korean government. J.K. acknowledges the Asan Foundation Biomedical Science fellowship and the Presidential Science fellowship funded by the MSIT of the Korean government. M.J. acknowledges the Hyundai Motor Chung Mong-Koo fellowship. S.-H.G. acknowledges support from the NRF grant (RS-2024-00335222) funded by the MSIT of Korea government, and Samsung Science and Technology Foundation (SSTF-BA1902-03). H.G.S. acknowledges support from the NRF grant (RS-2024-00337279 and RS-2024-00454894) funded by the MSIT of Korea government and KIST Institutional Programs (2E33831).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.R., S.-H.G., and H.G.S. conceptualized and supervised the study. J.S. and J.K. performed all data analysis and visualization. J.K., M.J., J.L., and S.K. fabricated the sample structures. J.S., H.S.L., D.-J.S., and D.C. conducted the optical experiments and data collection. J.S. and J.K. wrote the original draft. J.R., S.-H.G., and H.G.S. reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sung, J., Kim, J., Lee, H.S. et al. Polariton condensate far-detuned from exciton resonance in WS2 bound states in the continuum. Nat Commun 17, 1434 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67454-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67454-5