Abstract

The global circulation of SARS-CoV-2 in human populations has driven the emergence of Omicron subvariants, which have become highly diversified through recombination. In late 2024, SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XEC variant emerged from the recombination of two JN.1 progeny, KS.1.1 and KP.3.3, and became predominant worldwide. Here, we investigate virological features of the XEC variant. Epidemic dynamics modeling suggests that spike substitutions in XEC mainly contribute to its increased viral fitness. Additionally, four licensed antivirals are effective against XEC. Although the fusogenicity of XEC spike is comparable to that of the JN.1 spike, the intrinsic pathogenicity of XEC in male hamsters is significantly higher than that of JN.1. Notably, we find that the nucleocapsid R204P mutation of XEC enhances inflammation through NF-κB activation. Recent studies suggest that the evolutionary potential of spike protein is reaching its limit. Indeed, our findings highlight the critical role of non-spike mutations in the future evolution of SARS-CoV-2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

RNA viruses are prone to high mutation rates. Environmental factors including host immune responses and antiviral treatment serve as selective pressures that favor the expansion of resistant variants. Genetic variation in RNA viruses typically occur through substitution, deletion and insertion. In addition, dramatic variation through recombination occurs in RNA viruses and is thought to have played a significant role in the recent evolutionary histories1,2,3,4. A notable example is severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)5,6 the causative agent of the highly contagious disease COVID-19.

Because humans experience infection and/or vaccination, the circulating variants, namely Omicron have evolved to exhibit reduced intrinsic pathogenicity, increased transmissibility, and enhanced immune escape compared with ancestral variants7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. The continuous circulation of Omicron has led to the emergence of “recombinant variants” through simultaneous infection with multiple variants and recombination in the host. Omicron XBB lineage was the most prevalent lineage worldwide, a recombinant between BA.2 subvariants BJ.1 and BM.1.1.1 (a descendant of BA.2.75). XBB is the first SARS-CoV-2 variant whose fitness increased through recombination rather than substitution12. Other recombinant variants, such as XBC.1.6 (Delta variant B.1.617.2 × BA.2) and XDD.1.1 (EG.5.1.1 × JN.1), have also been identified, though they did not become the predominant variant. Recent studies indicate that intracellular dynamics can modulate recombination frequency and thereby shuffle traits such as transmissibility and antigenicity17, and clinical reports confirm that recombination can occur in vivo and be transmitted onward18. In line with this, newly emerging lineages such as NB.1.8.1 (JN.1 × XDE) and XFG (LF.7 × LP.8.1.2) have become globally predominant, underscoring that recombination remains an active force in SARS-CoV-2 evolution.

Omicron XEC variant emerged from the recombination of two JN.1 descendants, KS.1.1 (JN.13.1.1.1) and KP.3.3 (JN.1.11.1.3.3). XEC was first identified in Germany in August 2024, has rapidly spread in several Western continents19. As of April 2025, XEC is predominantly circulating worldwide according to Nextstrain (clade 24F; https://nextstrain.org/ncov/gisaid/global/6m). Because XEC is a chimera of KS.1.1 and KP.3.3 variants, spike (S) protein of XEC inherited key mutations enhanced binding affinity to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor from KP.3.3 and acquired mutations for the immune-evasive properties from KS.1.119,20,21,22,23. This suggests that XEC S maintains a similar affinity to ACE2 and a higher capacity to evade immunity compared with the previously dominant variants, KP.3 and KP.3.1.1. In addition, XEC has the R204P mutation in the nucleocapsid (N) protein and the A419T mutation in the NSP2 protein, which it inherited from KP.3.3 and KS.1.1, respectively. In the past variants, the co-occurring mutations at positions 203 and 204 of N (R203K/G204R) are involved in the efficient assembly of viral particle, leading to increased viral replication and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-224,25,26. The effect of the N:R204P mutation on the virological characteristics including replication and pathogenicity has not been reported.

In this study, we aimed to characterize the virological features of SARS-CoV-2 XEC variant and investigate how the R204P mutation in the nucleocapsid protein affects viral replication and pathogenicity.

Results

Mutations contributing to the increased viral fitness of XEC

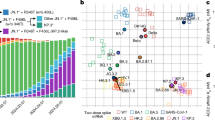

Compared with JN.1, XEC has five amino acid substitutions (S:T22N, S:F59S, S:F456L, S:Q493E, and S:V1104L) in S and two substitutions in the non-spike protein genes (NSP2:A419T and N:R204P)19. To identify the mutations contributing to the rapid spread of XEC, we applied a hierarchical Bayesian multinomial logistic model established in our previous study to viral genome surveillance data from GISAID11. Here, fitness refers to the relative effective reproductive number (Re) between variants, estimated under the assumption that the relative values of the Re among variants remain constant over time. This model predicts the effect of mutations by assuming that the fitness of a given variant is represented as the sum of the effects of its constituent mutations11. When multiple mutations are highly co-occurring, it becomes challenging to estimate their individual effects. To address this, these co-occurring mutations were grouped into mutation clusters, and their effects were estimated at the mutation cluster level. We applied this model to viral genome epidemiological surveillance data from the USA, covering the period from January 1, 2024, to December 31, 2024. This dataset includes 209 mutation clusters, composed of 277 distinct mutations (Supplementary data 1).

?A3B2 twb=.3w?>Among the 209 analyzed mutation clusters, 15 were estimated to contribute positively to increased fitness (Fig. 1A, B). The mutation cluster that exhibited the highest positive effect corresponded to mutations acquired on the stem branch of the BA.2.86 lineage or the JN.1 lineage. Notably, among the seven characteristic mutations of XEC, S:F456L, S:Q493E, S:F59S, and S:T22N were estimated to have a significant positive effect on fitness, ranking in the top 2, 3, 5 and top 8, respectively. In contrast, no statistically significant effect was detected for S:V1104L, NSP2:A419T and N:R(G)204 P (Fig. 1A). These results suggest that the rapid spread of XEC was driven by S:F456L, S:Q493E, S:T22N, and S:F59S rather than other substitutions.

A Estimated effect of each mutation on relative effective reproductive number (Re) estimated by a hierarchical Bayesian model. A group of highly co-occurred mutations (e.g., those acquired on the stem branch of the BA.2.86 or JN.1 lineage) was treated as mutation clusters. The red and blue dots indicate the substitutions with significant positive and negative effects, respectively. Mutations characteristic to XEC are highlighted in pink. B, C Estimated effect of each mutation on relative Re. B shows the top 25 mutations with the highest estimated effects, while C presents the 5 mutations with the lowest estimated effects. The posterior mean value (dot) and 95% credible interval (line) are shown.

Fusogenicity of XEC S

The fusogenicity of the XEC S protein was measured by the SARS-CoV-2 S protein-mediated membrane fusion assay using Calu-3/DSP1-7 cells (Fig. S1A, B)27. The surface expression level of XEC S was comparable to that of the parental JN.1 S (Fig. S1C, D). As previously reported27,28,29, the Delta S protein exhibited the greatest fusogenicity, while the KP.3 S protein exhibited the weakest fusogenicity (Fig. 2A). In the case of XEC S, comparable fusogenicity to the JN.1 S protein was observed, suggesting the XEC S protein contributes similar viral pathogenicity to the JN.1 S protein.

A S-based fusion assay in Calu-3 cells. The dashed green line indicates the result of JN.1. The red number in each panel indicates the fold difference between JN.1 and the derivative tested at 24 h post coculture. Assays were performed in quadruplicate. Statistically significant differences versus JN.1 across time points were determined by multiple regression. B Effect of antiviral drugs against XEC. Antiviral effects of the four drugs (EIDD-1931, nirmatrelvir [also known as PF-07321332], remdesivir, and ensitrelvir) in human iPSC-derived lung organoids. The assay of each antiviral drug was performed in triplicate, and the 50% effective concentration (EC50) was calculated. The viral RNA amount without treatment with antiviral drugs was set as 100%. C JN.1 and XEC were inoculated into VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells (MOI = 0.01). The 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) of the culture supernatant were routinely quantified. (n = 3 independent experiments). D, E Syrian hamsters were intranasally inoculated with JN.1 and XEC. Six hamsters of the same age were intranasally inoculated with saline (uninfected). D Six hamsters per group were quantified viral RNA load in oral swab by RT-qPCR. E Six hamsters per group were used to routinely measure the body weight. Uninfected (saline) hamster data is also shown. The familywise error rates (FWERs) calculated using the Holm method are indicated in the figures. h.p.i: hours post-infection; d.p.i: days post-infection. F H&E staining of the lungs at 2 d.p.i. of infected hamsters. Representative figures and uninfected lung alveolar space are shown. The presented data are expressed as the average ± SD (A, B) or SEM (C–E). Scale bars, 250 µm.

Antiviral effect of clinically available compounds against XEC

We assessed the sensitivity of XEC to four licensed antiviral drugs, EIDD-1931, nirmatrelvir (also known as PF-07321332), remdesivir, and ensitrelvir. Clinical isolate of JN.1 was used as a control. Both viruses were inoculated into human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived lung organoids, a physiologically relevant model, and treated with the four antiviral drugs. Among them, nirmatrelvir showed the strongest antiviral effects, with no significant differences in antiviral efficacy were observed between JN.1 and XEC (Figs. 2B and S2). Remdesivir and ensitrelvir demonstrated significant antiviral effects on the two isolates, whereas EIDD-1931 exhibited moderate antiviral effects on the two isolates.

Viral replication and pathogenicity of XEC variant

To investigate the replication efficiency and intrinsic pathogenicity of XEC, we used the clinical isolates of JN.1 and XEC. First, we inoculated clinical isolates of JN.1 and XEC into VeroE6 cells expressing TMPRSS230 (Fig. 2C) and into human iPSC-derived lung organoids (Fig. S3). Quantifying viral infectious titers in supernatants showed that the replication efficiency of XEC was comparable to that of JN.1 in both cell culture systems. Next, clinical isolates of JN.1 and XEC were respectively intranasally inoculated into hamsters, the established animal model for evaluation7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,28. To evaluate viral spread in infected hamsters, we routinely measured the viral RNA load in oral swabs. The viral RNA load of XEC-infected hamsters was comparable to that of JN.1-infected hamsters at 2 and 5 d.p.i. (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, the body weights of the hamsters infected with XEC were significantly lower than those of JN.1-infected hamsters (Fig. 2E), representing a transient weight loss. To further evaluate intrinsic pathogenicity, we performed histopathological analyses of lung tissues. At 2 d.p.i., JN.1-infected hamsters showed only limited bronchial and bronchiolar inflammation, whereas XEC-infected hamsters exhibited more pronounced alveolar damage (Figs. 2F and S4). Together, these results indicate that, despite comparable replication efficiency, XEC exhibits higher pathogenicity than JN.1.

Mutation dynamics of nucleocapsid protein

Because N protein functions as the basis for viral RNA genome packaging into ribonucleotide complex (RNP) and assembly into virus particles, functional changes lead to alter viral pathogenicity in vivo25,31,32,33. To investigate the effects of mutation in N, the frequency of mutations in JN.1 and XEC was examined. P13L, E31del, R32del, S33del, G204R, and S413R mutations were acquired in a convergent manner during the evolution of the Omicron variant (Fig. 3A)34. In addition, Q229K mutation was acquired during evolution to BA.2.8615. The previous study showed R203K/G204R mutation contributed to enhance both viral replication and pathogenicity. Therefore, the R204P mutation in XEC may affect alteration of viral replication and pathogenicity.

A Frequency of N protein’s mutations in XEC and other lineages of interest. Only mutations with a frequency >0.5 in at least one representative lineage are shown. B The efficiency of VLP assembly was measured for different N-protein species indicated and quantified in relative luminescence units. C Growth kinetics of rJN.1, rXEC/N:P204R, and rXEC were inoculated into VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells (MOI = 0.01). The 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) of the culture supernatant were routinely quantified. (n = 3 independent experiments). D Recombinant viruses were inoculated into an airway-on-a-chip system. The copy numbers of viral RNA in the top and bottom channels of an airway-on-a-chip were routinely quantified by RT-qPCR (left). The percentage of viral RNA load in the bottom channel per top channel at 6 d.p.i. (i.e., % invaded virus from the top channel to the bottom channel) is shown (right). (n = 3 independent experiments). E The percentage of viral RNA load in the bottom channel per top channel at 6 d.p.i. (i.e., % invaded virus from the top channel to the bottom channel) is shown. F–H Syrian hamsters were intranasally inoculated with the recombinant viruses. Six hamsters per group were used to routinely measure the respective parameters. F Body weight of infected hamsters (n = 6 per infection group). Uninfected hamster data is also shown. G Viral RNA loads in the oral swab (n = 6 per infection group) at 2 and 5 d.p.i. H Viral RNA loads in the lung hilum (left) and lung periphery (right) of infected hamsters (n = 4 per infection group) at 2 and 5 d.p.i. The FWERs calculated using the Holm method are indicated in the figures. The presented data are expressed as the average ± SEM (B–H). Statistical significance was determined using Tukey’s multiple comparison test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

Effects of N:R204P on the viral assembly and replication

To evaluate the effect of the N:R204P mutation on the viral assembly, we performed a virus-like particle (VLP) assay. The formation of VLPs in 293T cells containing SARS-CoV-2 structural proteins (S, E, M, and N) and packaging RNA is detected through expression of a luciferase reporter in infected receiver cells35,36. When compared within the same backbone (JN.1N vs. XEC N), the N:R204P mutation did not affect the assembly of VLPs (Fig. 3B). Next, to examine the effect of N:R204P mutation on viral replication, we generated recombinant viruses carrying the single mutation in the N protein of XEC, rXEC/N:P204R, rXEC, and rJN.1. The recombinant viruses were inoculated into the cell cultures we examined as above. In VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells (Fig. 3C), no significant differences in growth kinetics were observed between the viruses. These findings suggest that the N:R204P mutation has little effect on the viral replication.

To investigate the impact of XEC infection on the airway epithelial and endothelial barriers, we employed an airway-on-a-chip system (Fig. S5). Viral penetration from the upper channel to the lower channel serves as an indicator of the viral ability to breach these barriers. The proportion of viruses that penetrated the lower channel of the XEC-infected airway-on-a-chip was higher compared with JN.1- and XEC/N:P204R-infected airway-on-a-chip (Figs. 3D, E and S6). SARS-CoV-2 N activates human endothelial cells through Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)/NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways37. Therefore, N:R204P mutation may affect the airway epithelial and endothelial barriers through endothelial activation. In our previous study using airway-on-a-chips, we confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 infection causes paracellular gaps of endothelial cells to widen38. Thus, the N protein may facilitate the viral penetration to the lower channel by widening the gaps between endothelial cells.

Effects of N:R204P on the viral pathogenicity

To further investigate the intrinsic pathogenicity of the three recombinant viruses, the viruses were respectively inoculated as above. Consistent with the result of clinical isolates, the body weights of the hamsters infected with rXEC were significantly lower than those of rJN.1-infected hamsters (Fig. 3F). Notably, the weight of hamsters infected with rXEC was significantly lower than those of hamsters infected with rXEC/N:P204R, indicating that N:R204P mutation contributes to enhanced pathogenicity.

To evaluate viral spread of the three recombinant viruses in hamsters, the viruses were respectively inoculated into hamsters. We routinely measured the viral RNA load in oral swabs. The viral RNA load of rJN.1-, rXEC/N:P204R- and rXEC-infected hamsters were comparable (Fig. 3G). We then compared viral spread in respiratory tissues. We collected the lungs of infected hamsters at 2 and 5 d.p.i., and the harvested tissues were separated into the hilum and periphery regions. The viral RNA loads of rXEC-infected hamsters were significantly lower than those of rJN.1- and rXEC/N:P204R-infected hamsters (Fig. 3H left and right).

Effects of XEC N:R204P on immunopathogenic features of XEC

We further performed IHC analysis targeting the viral N protein in the respiratory tissues of infected hamsters. At 2 d.p.i, N-positive cells were more detected in the bronchi/bronchioles of rJN.1-infected hamsters than rXEC- and the N:P204R-infected hamsters (Figs. 4A and S7).

A IHC of the viral N protein in the lungs at 2 d.p.i. (left) and 5 d.p.i. (right) of infected hamsters. Representative figures (N-positive cells are shown in brown). Images are from comparable lung lobes, not identical microscopic fields. Uninfected hamster data is also shown. B H&E staining of the lungs at 2 d.p.i. (left) and 5 d.p.i. (right) of infected hamsters. Representative figures and uninfected lung alveolar space are shown. C The structure of N (JN.1 N and XEC N) was predicted by Alphafold3. D HEK293/ACE2/TMPRSS2 cells were transfected with NF-κB reporter vector. At 24 h after transfection, cells were infected with rJN.1, rXEC/N:P204R, and rXEC for 1 h. Luciferase activity was measured at 12 and 24 h.p.i. Horizontal lines in figures represent the average value of the negative control group. (n = 3 independent experiments). E mRNA of the lung tissues obtained at 2 d.p.i. was used to measure expression levels of inflammatory genes (Il-1β, Il-6, Il-8, and Ccl2) with normalization using the housekeeping gene Rpl18. (n = 4 per infection group). The presented data are expressed as the average ± SEM (D, E). Statistical significance was determined using Tukey’s multiple comparison test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). Scale bars, 250 µm.

To investigate the intrinsic pathogenicity of recombinant viruses, histopathological analyses were performed. At 2 d.p.i, alveolar damage around the bronchi was prominent in rXEC- and the N:P204R-infected hamsters (Figs. 4B and S8). On the other hand, inflammation was limited in bronchi/bronchioles in the hamsters infected with rJN.1 (Fig. 4B). At 5 d.p.i, the alveolar architecture was more destroyed by alveolar damage and the expansion of type II pneumocytes in rXEC-infected hamsters (Fig. 4B). The low viral load in XEC-infected lungs may be due to viral clearance caused by an enhanced immune response, judging from the degree of inflammation (Fig. 4A, B). Notably, a strong inflammation in the acute phase was observed in the lungs of rXEC-infected hamsters even at 5 d.p.i. These results suggest that the N:R204P mutation contributes to increased inflammation in the lung.

NF-κB activation of XEC N protein

SARS-CoV-2 accessory and non-structural proteins, including ORF3a, ORF7a, NSP5, NSP6 and NSP14, have been shown to activate the NF-κB pathway and induce downstream inflammatory cytokines and chemokines39,40,41,42,43,44. On the other hand, SARS-CoV-2 N protein has been reported to inhibit NF-κB activation and downstream signaling by inhibiting the formation of the TAK1-TAB2/3 complex45. In addition, N protein lacking interaction with the TAK1-TAB2/3 complex has been shown to induce strong inflammation. Since proline in the linker increases structural rigidity46, we hypothesized that the R204P mutation might alter the overall structure of N protein and impair this regulatory function.

Using AlphaFold347, we found that the amino acid substitutions from arginine to proline at position 204 in XEC N altered the position of the α-helix and the linker (Fig. 4C). As this α-helix has been reported to be important for interaction with the TAK1-TAB2/3 complex, we investigated the effect of N:R204P mutation on NF-κB activation by NF-κB promoter-driven luciferase assay in HEK293/ACE2/TMPRSS2 cells. As expected, the luciferase assay indicated that rXEC-infection activated NF-κB promoter more than rJN.1- and rXEC/N:P204R-infection in HEK293/ACE2/TMPRSS2 cells48 (Fig. 4D).

To assess NF-κB-induced inflammatory signaling provoked by viral infection in vivo, we extracted mRNA of the lung hilum and periphery areas at 2 d.p.i., and quantified the expression of four interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) (Il-1β, Il-6, Il-8, and Ccl2) (Fig. 4E). In the lung hilum, rXEC-infection upregulated Il-6 and Il-8 expression more than rJN.1- and rXEC/N:P204R-infection, suggesting that XEC could induce severe inflammation, supporting the histopathological data. In the lung hilum, the expression levels of Il-1β and Ccl2 were also higher in rXEC-infected lungs than in rJN.1-infected lungs. Taken together, these results indicate that the N:R204P mutation enhances inflammation through NF-κB activation.

Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 continues to circulate in human populations worldwide, and recombination between co-circulating variants remains a major driver of its diversification. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XEC variant, which emerged through recombination between two JN.1 descendants, rapidly spread and became globally predominant. Our previous report demonstrated that XEC possesses an effective reproduction number (Re) 1.13 times higher than that of the previously dominant KP.3.1.1 variant19. To the best of our knowledge, XEC is the second SARS-CoV-2 recombinant lineage to achieve global predominance, following the XBB lineage. In this study, we conducted a comprehensive multiscale investigation to elucidate the virological properties of XEC and identify the mutation(s) defining the characters.

Epidemic dynamics modeling showed that two mutations in the XEC lineage, S:T22N and S:F59S contribute significantly to its rapid spread (Fig. 1). Consistent with these findings, Li et al. recently reported that these mutations alter hydrophilic interactions with adjacent S protein residues, thereby affecting both structural stability and neutralization capacity23. We then evaluated the growth kinetics, sensitivity to clinically available antiviral compounds and fusogenicity of the XEC variant in cell culture and lung organoids. Our experimental results showed that sensitivity to licensed antivirals, fusogenicity and replication efficiency of XEC were comparable to those of JN.1 (Fig. 2A–D). Because the lung organoids used to evaluate the antiviral drugs were generated from a single donor, our findings may not fully reflect inter-individual differences. Therefore, future studies should employ organoid panels generated from multiple donors to better capture variability in drug responses.

The most striking difference between XEC and JN.1 lies in the enhanced intrinsic pathogenicity of XEC, as assessed in the hamster model that has been established and employed in our series of studies7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,28. As shown in Fig. 2E, XEC infection resulted in a greater reduction in body weight compared to JN.1. In a recent study, Guo et al. reported that SARS-CoV-2 N protein inhibits NF-κB activation and that functional loss of N leads to enhanced inflammation45. Thus, we generated the single mutant virus, rXEC/N:P204R, which carries an N gene mutation reverted to the JN.1 sequence (Fig. 3F). rXEC/N:P204R infection led to less attenuation of weight loss compared to the parental rXEC infection. Histopathological analyses also indicated the diminished inflammation upon infection with rXEC/N:P204R (Fig. 4B). Structural modeling using AlphaFold3 suggested that the N:R204P substitution alters the position of the α-helix in the C-terminal domain of the N protein, potentially impairing its ability to inhibit NF-κB activation via interaction with the TAB2/3 complex. Of noted, these predictions will require biochemical validation in future studies, for example by Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC). Consistent with this, the promoter assay revealed that the N:R204P mutation contributes to NF-κB activation (Fig. 4C, D). Furthermore, in vivo analysis showed significantly elevated expression of IL-6 and IL-8 in the lungs of rXEC-infected hamsters compared to those infected with rXEC/N:P204R, indicating enhanced NF-κB-mediated inflammatory signaling (Fig. 4E). Taken these findings together, the N:R204P mutation might lead to disrupt the N protein’s ability to inhibit NF-κB activation, thereby contributing to the enhanced pathogenicity of XEC in vivo. Although the N:R204P mutation did not affect viral replication in vitro (Fig. 3C), viral RNA levels and N-positive areas in the lungs of XEC-infected hamsters were lower than those in rJN.1 infection (Figs. 3H and 4A). We interpret this discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo as the result of an exaggerated inflammatory response: accelerated viral clearance coinciding with immune-mediated tissue damage. These findings highlight a mechanism by which host inflammatory responses, rather than intrinsic replication capacity, may predominantly drive the severe pathogenicity of the XEC variant.

Thus far, Omicron subvariants have largely evolved through modifications in the S protein that enable escape from immune pressure in the human population6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. While the N:R204P itself offers no apparent adaptive benefit and the S mutation remains the principal determinant of XEC dissemination, accumulating evidence indicates that the evolutionary plasticity of SARS-CoV-2 mediated by the S protein may be approaching saturation16,49,50,51,52. For example, while the JN.1 subvariant demonstrates enhanced immune evasion conferred by the S:L455S mutation, this is accompanied by compromised replication efficiency and decreased pathogenicity in the lungs16,49. Our data indicate that the acquisition of the N:R204P mutation enhances pathogenicity of XEC compared to JN.1. This highlights that strategies to modulate certain virological properties through mutations in non-spike proteins may become more common in the future evolution of SARS-CoV-2. In addition, even non-spike mutations that do not provide an immediate selective advantage may persist at low frequency and re-emerge under certain evolutionary contexts. This is consistent with the observation that although N:G204P had been reported in B.1.1.7 sub-lineage, it did not become dominant53. While this mutation has not been retained in currently circulating variants, frequent recombination among co-circulating lineages can reintroduce mutations with pathogenic potential, even if they are not maintained under strong positive selection.

Beyond spike-mediated adaptations, increasing evidence highlights the contribution of non-spike proteins to SARS-CoV-2 pathogenicity and transmission. ORF7b perturbs host defenses by disrupting epithelial integrity and modulating innate immune signaling54,55. ORF8 facilitates immune evasion through MHC-I downregulation while enhancing proinflammatory responses56,57. Deletions in ORF7b and ORF8 have been repeatedly detected in circulating variants, suggesting a role in viral transmissibility58,59. NSP6 remodels host membranes to form replication organelles and suppresses autophagy and interferon responses; recurrent mutations such as Δ106-108 and R252K fine-tune viral fitness by altering autophagy and replication dynamics60,61,62,63. In addition, the nucleocapsid (N) protein is particularly multifunctional, mediating RNA packaging through liquid–liquid phase separation, antagonizing interferon signaling by interfering with stress granules, and activating the NLRP3 inflammasome64,65,66,67,68,69. Given this pleiotropy, the impact of N is likely amplified through interactions with other non-spike proteins. For example, NSP2—which also carries mutations in the XEC lineage—regulates host translation and suppresses antiviral signaling, thereby modulating innate immune responses70,71. Although direct synergy between NSP2 and N has not yet been demonstrated, their convergence on innate immune regulation raises the possibility of cooperative effects that exacerbate immune-mediated pathology.

In summary, our comprehensive characterization of the XEC variant suggests an emerging shift in the evolutionary trajectory of SARS-CoV-2, from spike-driven adaptation to a combination of spike and non-spike modulation. These insights not only advance our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 biology but also inform more effective strategies for controlling COVID-19.

Methods

Virus-like particle assay

A virus-like particle (VLP) assay was employed as a physiological model to test the efficiency of packaging and assembly as a function of the mutations on SARS-CoV-2 N protein35,36. The assay was conducted as described previously35,36. Briefly, the VLPs were generated by co-expressing all four structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2 in HEK293T cells along with a construct containing ~1 kb viral packaging signal PS9 incorporated into the untranslated region of a firefly luciferase reporter. VLPs in the supernatant carrying luciferase reporter were added to receiver HEK293T cells stably expressing ACE2 and TMPRSS2 (HEK293T/ACE2/TMPRSS2 cells) in 96-well plates. Luminescence in receiver cells was measured at 12–16 h post infection using luciferase assay system (Promega).

Cell culture

HEK293 cells (a human embryonic kidney cell line; ATCC, CRL-1573) and HEK293T cells (a human embryonic kidney cell line; ATCC, CRL-3216) were maintained in DMEM (high glucose) (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# 6429-500 ML; Nacalai Tesque, Cat# 08458-16) containing 10% FBS and 1% PS. VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells (an African green monkey kidney cell line stably expressing human TMPRSS2; JCRB Cell Bank, JCRB1819)30 were maintained in DMEM (low glucose) (FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals, Cat# 041-29775) containing 10% FBS, G418 (1 mg/ml), and 1% PS. Calu-3/DSP1-7 cells (Calu-3 cells stably expressing DSP1-7)72 were maintained in EMEM (FUJIFILM Wako Chemicals, Cat# 056-08385) containing 20% FBS and 1% PS.

NF-κB promoter assay

HEK293/ACE2/TMPRSS2 cells were seeded onto 24-well plates and transfected. To assess NF-κB signaling, 50 ng of the pNL3.2.NF-κB-RE vector (Promega, Cat# N1111) was utilized. Following transfection for 24 h, cells were infected for 1 h. For controls, cells were treated with DMEM (negative control) or stimulated with the recombinant TNF-α (positive control) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 300-01 A) for 1 h. The cells were then lysed using a passive lysis buffer and subjected to luciferase activity measurements by the Luciferase Reporter Assay System using an AB-2270 Luminescencer Octa (Atto).

Modeling the relationship between amino acid mutations and epidemic dynamics

To identify the mutations contributing to the rapid spread of XEC, we utilized a hierarchical Bayesian multinomial logistic model previously developed by our research group to estimate the effects of mutations on fitness11. Here, fitness refers to the relative Re between variants, estimated under the assumption that the relative values of the Re among variants remain constant over time. Unlike the conventional method of estimating Re using a multinomial logistic model28, this model does not directly estimate the fitness of variants. Instead, it introduces a hierarchical structure to estimate fitness as a linear combination of mutations. As a result, this model can estimate not only the fitness of each variant but also the effects of individual mutations on fitness. For highly co-occurring mutations (mutation clusters), our method does not permit the estimation of individual effects, and thus, effects are estimated at the mutation cluster level. For details on the model, please refer to Ito et al11. In this study, we estimated the effects of mutations not only in the spike protein but across all viral proteins.

The data used in this analysis were downloaded from the GISAID database (https://www.gisaid.org/) on January 26, 202573. For quality control, we excluded the data of viral sequences with the following features from the analysis: (i) a lack of collection date information; (ii) sampling in animals other than humans; (iii) >1% undetermined nucleotide characters; or (iv) sampling by quarantine. Furthermore, in this analysis, we analyzed viral sequences collected in the USA from January 1, 2024, to December 31, 2024.

For the analysis, we selected mutations (including substitutions, insertions, and deletions) observed in ≥100 sequences in the dataset we used. We then excluded mutations commonly (≥95%) detected in sequences analyzed. According to the criteria above, 209 mutations were retrieved. Subsequently, we classified viral sequences into haplotypes, a group of viral sequences sharing the same set of mutations, according to the profile of the selected mutations. We excluded haplotypes with ≤30 sequences from the downstream analyses. According to the criterion above, 366 types of haplotypes, composed of 51,127 sequences, were retrieved. Then, we clustered highly co-occurring mutations (i.e., a pair of mutations with >0.9 Pearson’s correlation in the mutation profile matrix) into mutation clusters. Consequently, our dataset included the profiles of 209 mutation clusters for 366 haplotypes. For the reference haplotype, which is estimated to have a relative Re of 1, we selected the haplotype with the highest sequence count, corresponding to the major haplotype of JN.1.

Parameter estimation was performed via the MCMC approach implemented in CmdStan v2.30.1 (https://mc-stan.org) with CmdStanr v0.5.3 (https://mc-stan.org/cmdstanr/). Four independent MCMC chains were run with 500 and 2000 steps in the warmup and sampling iterations, respectively. We confirmed that all estimated parameters showed <1.01 R-hat convergence diagnostic values and >200 effective sampling size values, indicating that the MCMC runs were successfully convergent. The above analyses were performed in R v4.2.1 (https://www.r-project.org/). Information on the estimated effect size of each mutation cluster on relative Re is summarized in Supplementary data 1.

Plasmid construction

The nine pmW118 plasmids containing the partial gene of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 were previously generated74. To generate the recombinant JN.1 and XEC viruses, the mutations were introduced into the corresponding plasmids encoding BA.2.86 gene by inverse fusion PCR cloning using the primers listed in Table S1. Sequences of all the plasmids used in this study were confirmed by a SeqStudio Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and an outsourced service (Fasmac). Primer and plasmid information can be provided upon request.

SARS-CoV-2 S-based fusion assay

A SARS-CoV-2 S-based fusion assay was performed as previously described75. Briefly, on day 1, effector cells (i.e., S-expressing cells) and target cells (Calu-3/DSP1-7 cells) were prepared at a density of 0.6–0.8 × 106 cells in a 6-well plate. On day 2, for the preparation of effector cells, HEK293 cells were cotransfected with the S expression plasmids and pDSP8-1176 using TransIT-LT1 (Mirus Bio, Cat# MIR2300). On day 3, 16,000 effector cells were detached and reseeded into a 96-well black plate (PerkinElmer), and target cells were reseeded at a density of 1,000,000 cells/2 ml/well in 6-well plates. On day 4, target cells were incubated with EnduRen live cell substrate (Promega, Cat# E6481) for 3 h and then detached, and 32,000 target cells were added to a 96-well plate with effector cells. Renilla luciferase activity was measured at the indicated time points using Centro XS3 LB960 (Berthold Technologies). For measurement of the surface expression level of the S protein, effector cells were stained with rabbit anti-SARS-CoV-2 S S1/S2 polyclonal antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# PA5-112048, 1:100). Normal rabbit IgG (Southern Biotech, Cat# 0111-01, 1:100) was used as a negative control, and APC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG polyclonal antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cat# 111-136-144, 1:50) was used as a secondary antibody. The surface expression level of S proteins was measured using CytoFLEX Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software v10.7.1 (BD Biosciences). For calculation of fusion activity, Renilla luciferase activity was normalized to the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of surface S proteins. The normalized value (i.e., Renilla luciferase activity per the surface S MFI) is shown as fusion activity.

Antiviral drug assay using SARS-CoV-2 clinical isolates and human iPSC-derived lung organoids

The antiviral drug assay was performed as previously described15. Human iPSC-derived lung organoids were used to perform the antiviral drug assay. These lung organoids contain both airway and lung epithelial cells77. As we reported previously15, after recovering the lung organoids from Matrigel, we seeded them as clusters onto thin Matrigel-coated plates. This procedure enables SARS-CoV-2 to access the apical side of the lung organoids. The human iPSC-derived lung organoids were infected with either JN.1 or XEC isolate (100 TCID50) at 37 °C for 2 h. Following infection, the cells were washed with DMEM and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% PS, and the serially diluted EIDD-1931 (an active metabolite of Molnupiravir; Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 81178S), Nirmatrelvir (MedChemExpress, Cat# HY-138687), Remdesivir (Clinisciences, Cat# A17170), or Ensitrelvir (MedChemExpress, Cat# HY-143216). At 72 h post-infection, the culture supernatants were collected, and viral RNA was quantified using RT-qPCR. The assay of each compound was performed in triplicate, and the 50% effective concentration (EC50) was determined using Prism 9 software v9.1.1 (GraphPad Software). The viral RNA amount without treatment with antiviral drugs was set as 100%.

SARS-CoV-2 preparation and titration

The working virus stocks of SARS-CoV-2 were prepared and titrated as previously described. In this study, clinical isolates of JN.1 (strain LG0688; GISAID ID: EPI_ISL_18771637) and XEC (strain TKYnat18145; GISAID ID: EPI_ISL_19512397) were used.

Recombinant viruses were generated by a circular polymerase extension reaction (CPER)48. The resultant CPER products were transfected into VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells as described previously13. All the viruses were stored at −80 °C until use, and viral genome sequences were confirmed by SANGER sequencing as described above.

Titration and growth kinetics

The infectious titers in culture supernatants obtained from the infected cells were determined by quantifying the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50)78. For growth kinetics, the viruses were respectively inoculated into VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells in 12-well plates at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. The infectious titers of the indicated timepoints were determined.

Airway-on-a-chip

Airways-on-a-chip were prepared as previously described38. Human lung microvascular endothelial cells (HMVEC-L) were obtained from Lonza and cultured with EGM-2-MV medium (Lonza, Cat# CC-3202). For preparation of the airway-on-a-chip, the bottom channel of a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) device was first precoated with fibronectin (3 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# F1141). The microfluidic device was generated according to our previous report79. HMVEC-L cells were suspended at 5,000,000 cells/ml in EGM2-MV medium. Then, 10 μl of suspension medium was injected into the fibronectin-coated bottom channel of the PDMS device. The PDMS device was turned upside down and incubated. After 1 h, the device was turned over, and EGM2-MV medium was added into the bottom channel. After 4 d, airway organoids (AO) were dissociated and seeded into the top channel. AOs were generated according to our previous report80. AOs were generated from normal human bronchial epithelial cells, not from human iPSCs. They contain ciliated, goblet, basal, and club cells. AOs were dissociated into single cells and then suspended at 5,000,000 cells/ml in the AO differentiation medium. Ten microliters of suspension medium were injected into the top channel. After 1 h, the AO differentiation medium was added to the top channel. In the infection experiments, the AO differentiation medium, containing either recombinant virus (500 TCID50), was inoculated into the top channel. At 2 h.p.i., the top and bottom channels were washed and cultured with AO differentiation and EGM2-MV medium, respectively. The culture supernatants were collected, and viral RNA was quantified using RT-qPCR.

Assessment of viral pathogenicity in hamsters

Animal experiments were performed as previously described7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. In brief, Syrian hamsters (male, 4 weeks old) were purchased from Japan SLC Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan). For the virus infection experiments, hamsters were intranasally inoculated under anesthesia with the viruses (2000 TCID50 in 100 μL for hamsters) or saline (100 μL). Body weight was recorded daily by 7 d.p.i. Lung tissues were anatomically collected at 2 and 5 d.p.i. The viral RNA load in the respiratory tissues was determined by RT-qPCR as described previously81. These tissues were also used for IHC and histopathologic analyses as previously described7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. The viral proteins were visualized by anti-SARS-CoV-2 N monoclonal antibody (R&D Systems, Clone 1035111, Cat# MAB10474-SP, 1:400). Pathological features—including (i) bronchitis or bronchiolitis, (ii) hemorrhage with congestive edema, (iii) alveolar damage with epithelial apoptosis and macrophage infiltration, (iv) hyperplasia of type II pneumocytes, and (v) the area of hyperplasia of large type II pneumocytes—were evaluated by certified pathologists after H&E staining. Images were incorporated as virtual slides by NDP.scan software v3.2.4 (Hamamatsu Photonics). The area of N-protein positivity and inflammation was measured using Fiji software v2.2.0 (ImageJ).

To evaluate inflammation levels evoked by viral infection in hamsters, 500 μg of the lung RNA was used to synthesize cDNA with SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 11756050). The resulting cDNA was used to quantify the expression of host genes82,83 with a Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 4367660) and QuantStudio Real-time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical significance was tested by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test using GraphPad Prism 9 unless otherwise noted. The values p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001). In the time-course experiments, a non-parametric permutation test was performed to evaluate the difference between experimental conditions through all timepoints. For each comparison, the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated as the sum of the values across timepoints. Group labels were randomly shuffled to generate the null distribution of AUC differences, and two-sided P values were calculated based on this distribution. Subsequently, familywise error rates (FWERs) were calculated by the Benjamini-Hochberg method. These analyses were performed in R v4.2.1 (https://www.r-project.org/). All assays were performed independently at least 3 times.

Ethics statement

All experiments with hamsters were performed in accordance with the Science Council of Japan’s Guidelines for the Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments. The protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National University Corporation Hokkaido University (approval ID: 20-0123). All human subjects provided written informed consent. All protocols for the use of human specimens were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyoto University (approval ID: R2379-3). All protocols for the use of human specimens were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo (approval IDs: 2021-1-0416 and 2021-18-0617).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Surveillance datasets of SARS-CoV-2 isolates used in this study are available from the GISAID database (https://www.gisaid.org; EPI_SET_251126dy). The supplemental tables for the GISAID datasets are available in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/TheSatoLab/XEC_full). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The computational codes used in the present study are available in the GitHub repository (https://github.com/TheSatoLab/XEC_full).

References

Dudas, G. & Rambaut, A. MERS-CoV recombination: implications about the reservoir and potential for adaptation. Virus Evol. 2, vev023 (2016).

Lau, S. K. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus orf8 protein is acquired from SARS-related coronavirus from greater horseshoe bats through recombination. J. Virol. 89, 10532–10547 (2015).

Holmes, E. C. & Rambaut, A. Viral evolution and the emergence of SARS coronavirus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 359, 1059–1065 (2004).

Bobay, L. M., O’Donnell, A. C. & Ochman, H. Recombination events are concentrated in the spike protein region of Betacoronaviruses. PLoS Genet. 16, e1009272 (2020).

Turakhia, Y. et al. Pandemic-scale phylogenomics reveals the SARS-CoV-2 recombination landscape. Nature 609, 994–997 (2022).

Wells, H. L. et al. The coronavirus recombination pathway. Cell Host Microbe 31, 874–889 (2023).

Suzuki, R. et al. Attenuated fusogenicity and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Nature 603, 700–705 (2022).

Kimura, I. et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2 subvariants, including BA.4 and BA.5. Cell 185, 3992–4007.e3916 (2022).

Tamura, T. et al. Comparative pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants, including BA.1, BA.2, and BA.5. Commun. Biol. 6, 772 (2023).

Saito, A. et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2.75 variant. Cell Host Microbe 30, 1540–1555.e1515 (2022).

Ito, J. et al. Convergent evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants leading to the emergence of BQ.1.1 variant. Nat. Commun. 14, 2671 (2023).

Tamura, T. et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 XBB variant derived from recombination of two Omicron subvariants. Nat. Commun. 14, 2800 (2023).

Tamura, T. et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XBB.1.5 variant. Nat. Commun. 15, 1176 (2024).

Tsujino, S., et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron EG.5.1 variant. Microbiol. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1111/1348-0421.13165 (2024).

Tamura, T. et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 variant. Cell Host Microbe 32, 170–180.e112 (2024).

Tsujino, S. et al. Evolution of BA.2.86 to JN.1 reveals that functional changes in non-structural viral proteins are required for fitness of SARS-CoV-2. J. Virol. 99, e0090825 (2025).

Bonavita, C. M., Wells, H. L. & Anthony, S. J. Cellular dynamics shape recombination frequency in coronaviruses. PLoS Pathog. 20, e1012596 (2024).

Dyrdak, R. et al. A novel SARS-CoV-2 recombinant transmitted from a patient with an acute co-infection. Lancet Microbe 5, 100998 (2024).

Kaku, Y. et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 XEC variant. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00731-X (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. Recurrent SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations confer growth advantages to select JN.1 sublineages. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 13, 2402880 (2024).

Arora, P. et al. Impact of JN.1 booster vaccination on neutralisation of SARS-CoV-2 variants KP.3.1.1 and XEC. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00688-1 (2024).

Liu, J. et al. Enhanced immune evasion of SARS-CoV-2 variants KP.3.1.1 and XEC through N-terminal domain mutations. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00738-2 (2024).

Li, P. et al. Role of glycosylation mutations at the N-terminal domain of SARS-CoV-2 XEC variant in immune evasion, cell-cell fusion, and spike stability. J Virol. e0024225. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00242-25 (2025).

Wu, H. et al. Nucleocapsid mutations R203K/G204R increase the infectivity, fitness, and virulence of SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe 29, 1788–1801.e1786 (2021).

Johnson, B. A. et al. Nucleocapsid mutations in SARS-CoV-2 augment replication and pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 18, e1010627 (2022).

Shuaib, M. et al. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid 203K/204R mutations on the inflammatory immune response in COVID-19 severity. Genome Med. 15, 54 (2023).

Begum, M. M. S. T. et al. Virological characteristics correlating with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein fusogenicity. Front. Virol. 4, 1353661 (2024).

Saito, A. et al. Enhanced fusogenicity and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Delta P681R mutation. Nature 602, 300–306 (2022).

Yamasoba, D. et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2 spike. Cell 185, 2103–2115.e2119 (2022).

Matsuyama, S. et al. Enhanced isolation of SARS-CoV-2 by TMPRSS2-expressing cells. Proc Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 7001–7003 (2020).

El-Maradny, Y. A. et al. Unraveling the role of the nucleocapsid protein in SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis: from viral life cycle to vaccine development. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 279, 135201 (2024).

Wu, W., Cheng, Y., Zhou, H., Sun, C. & Zhang, S. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein: its role in the viral life cycle, structure and functions, and use as a potential target in the development of vaccines and diagnostics. Virol. J. 20, 6 (2023).

Han, Y. et al. SARS-CoV-2 N protein coordinates viral particle assembly through multiple domains. J. Virol. 98, e0103624 (2024).

Nguyen, A., et al. Modulation of biophysical properties of nucleocapsid protein in the mutant spectrum of SARS-CoV-2. Elife 13 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.94836 (2024).

Syed, A. M. et al. Rapid assessment of SARS-CoV-2-evolved variants using virus-like particles. Science 374, 1626–1632 (2021).

Syed, A. M. et al. Omicron mutations enhance infectivity and reduce antibody neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 virus-like particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2200592119 (2022).

Qian, Y. et al. Direct activation of endothelial cells by SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein is blocked by simvastatin. J. Virol. 95, e0139621 (2021).

Hashimoto, R. et al. SARS-CoV-2 disrupts respiratory vascular barriers by suppressing Claudin-5 expression. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo6783 (2022).

Li, W. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp5 activates NF-κB pathway by upregulating SUMOylation of MAVS. Front. Immunol. 12, 750969 (2021).

Su, C. M., Wang, L. & Yoo, D. Activation of NF-κB and induction of proinflammatory cytokine expressions mediated by ORF7a protein of SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep. 11, 13464 (2021).

Nishitsuji, H., Iwahori, S., Ohmori, M., Shimotohno, K. & Murata, T. Ubiquitination of SARS-CoV-2 NSP6 and ORF7a facilitates NF-κB activation. mBio 13, e0097122 (2022).

Nie, Y. et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a positively regulates NF-κB activity by enhancing IKKβ-NEMO interaction. Virus Res. 328, 199086 (2023).

Hua, F. et al. Linear ubiquitination mediates coronavirus NSP14-induced NF-κB activation. Cell Commun. Signal. 22, 573 (2024).

Ito, H. et al. Involvement of SARS-CoV-2 accessory proteins in immunopathogenesis. Microbiol. Immunol. 68, 237–247 (2024).

Guo, X. et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific adaptations in the N protein inhibit NF-κB activation and alter pathogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 224 https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.202404131 (2025).

Reddy Chichili, V. P., Kumar, V. & Sivaraman, J. Linkers in the structural biology of protein-protein interactions. Protein Sci. 22, 153–167 (2013).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Torii, S. et al. Establishment of a reverse genetics system for SARS-CoV-2 using circular polymerase extension reaction. Cell Rep. 35, 109014 (2021).

Wickenhagen, A. et al. Evolution of Omicron lineage towards increased fitness in the upper respiratory tract in the absence of severe lung pathology. Nat. Commun. 16, 594 (2025).

Yang, S. et al. Fast evolution of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 to JN.1 under heavy immune pressure. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24, e70–e72 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Structural basis for the evolution and antibody evasion of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 and JN.1 subvariants. Nat. Commun. 15, 7715 (2024).

Chakraborty, C., Bhattacharya, M. & Abdelhameed, A. S. Recent SARS-CoV-2 evolution trajectories indicate the emergence of Omicron’s several subvariants and the current rise of KP.3.1.1 and XEC. Virology 607, 110508 (2025).

Stadtmüller, M. et al. Emergence and spread of a sub-lineage of SARS-CoV-2 Alpha variant B.1.1.7 in Europe, and with further evolution of spike mutation accumulations shared with the Beta and Gamma variants. Virus Evol. 8, veac010 (2022).

Nguyen, M. H. et al. Analysis of the structure and interactions of the SARS-CoV-2 ORF7b accessory protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2407731121 (2024).

Deshpande, R. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Accessory Protein Orf7b Induces Lung Injury via c-Myc Mediated Apoptosis and Ferroptosis.Int. J. Mol. Sci.25 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25021157 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. The ORF8 protein of SARS-CoV-2 mediates immune evasion through down-regulating MHC-Ι. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2024202118 (2021).

McGrath, M. E. et al. SARS-CoV-2 ORF8 modulates lung inflammation and clinical disease progression. PLoS Pathog. 20, e1011669 (2024).

Su, Y. C. F. et al. Discovery and genomic characterization of a 382-nucleotide deletion in ORF7b and ORF8 during the early evolution of SARS-CoV-2. mBio 11 https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01610-20 (2020).

Rogozin, I. B., Saura, A., Bykova, A., Brover, V., and Yurchenko, V. Deletions across the SARS-CoV-2 genome: molecular mechanisms and putative functional consequences of deletions in accessory genes. Microorganisms 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11010229 (2023).

Ricciardi, S. et al. The role of NSP6 in the biogenesis of the SARS-CoV-2 replication organelle. Nature 606, 761–768 (2022).

Zhang, C. et al. SARS-CoV-2 NSP6 reduces autophagosome size and affects viral replication via sigma-1 receptor. J. Virol. 98, e0075424 (2024).

Feng, S., O’Brien, A., Chen, D. Y., Saeed, M. & Baker, S. C. SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural protein 6 from alpha to Omicron: evolution of a transmembrane protein. mBio 14, e0068823 (2023).

Taha, T. Y. et al. Enhanced RNA replication and pathogenesis in recent SARS-CoV-2 variants harboring the L260F mutation in NSP6. PLoS Pathog. 21, e1013020 (2025).

Wang, S. et al. Targeting liquid-liquid phase separation of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein promotes innate antiviral immunity by elevating MAVS activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 23, 718–732 (2021).

Long, S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 N protein recruits G3BP to double membrane vesicles to promote translation of viral mRNAs. Nat. Commun. 15, 10607 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. SARS-CoV-2 N protein antagonizes stress granule assembly and IFN production by interacting with G3BPS to facilitate viral replication. J. Virol. 96, e0041222 (2022).

Cai, S. et al. Phase-separated nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2 suppresses cGAS-DNA recognition by disrupting cGAS-G3BP1 complex. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 170 (2023).

Gutmann, T., Kuster, D. & Hyman, A. A. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein directly prevents cGAS-DNA recognition through competitive binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2426204122 (2025).

Pan, P. et al. SARS-CoV-2 N protein promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation to induce hyperinflammation. Nat. Commun. 12, 4664 (2021).

Xu, Z. et al. SARS-CoV-2 impairs interferon production via NSP2-induced repression of mRNA translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2204539119 (2022).

Korneeva, N. et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral protein Nsp2 stimulates translation under normal and hypoxic conditions. Virol. J. 20, 55 (2023).

Yamamoto, M. et al. The anticoagulant nafamostat potently inhibits SARS-CoV-2 S protein-mediated fusion in a cell fusion assay system and viral infection in vitro in a cell-type-dependent manner. Viruses 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/v12060629 (2020).

Khare, S. et al. GISAID’s role in pandemic response. China CDC Wkly. 3, 1049–1051 (2021).

Kawashiro, K. et al. Neutralizing antibody responses and cellular responses against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants after mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in kidney transplant recipients. Sci. Rep. 14, 12176 (2024).

Nasser, H. et al. Monitoring fusion kinetics of viral and target cell membranes in living cells using a SARS-CoV-2 spike-protein-mediated membrane fusion assay. STAR Protoc. 3, 101773 (2022).

Kondo, N., Miyauchi, K. & Matsuda, Z. Monitoring viral-mediated membrane fusion using fluorescent reporter methods. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. Chapter 26, Unit 26.29 https://doi.org/10.1002/0471143030.cb2609s50 (2011).

Hashimoto, R. et al. Human iPS cell-derived respiratory organoids as a model for respiratory syncytial virus infection. Life Sci. Alliance 8 https://doi.org/10.26508/lsa.202402837 (2025).

Reed, L. J. & Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am.J.Epidemiol. 27, 493–497 (1938).

Deguchi, S. et al. Usability of polydimethylsiloxane-based microfluidic devices in pharmaceutical research using human hepatocytes. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 7, 3648–3657 (2021).

Sano, E. et al. Cell response analysis in SARS-CoV-2-infected bronchial organoids. Commun. Biol. 5, 516 (2022).

Motozono, C. et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike L452R variant evades cellular immunity and increases infectivity. Cell Host Microbe 29, 1124–1136.e1111 (2021).

Bessière, P. et al. Intranasal type I interferon treatment is beneficial only when administered before clinical signs onset in the SARS-CoV-2 hamster model. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009427 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. Developing a triple transgenic cell line for high-efficiency porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection. PLoS ONE 11, e0154238 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all members of The Genotype to Phenotype Japan (G2P-Japan) Consortium. We thank H. Kubo, M. Tetsuka, S. Shimamura, K. Yano, and A. Hisanaga for their secretory work and H. Murota for his technical assistance. We also thank Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Public Health (Tokyo, Japan) for providing a clinical isolate. We gratefully acknowledge the numerous laboratories worldwide that have provided sequence data and metadata to GISAID. This study was supported in part by AMED SCARDA Japan Initiative for World-leading Vaccine Research and Development Centers “UTOPIA” (JP223fa627001, to K.S.), AMED SCARDA Program on R&D of new generation vaccine including new modality application (JP223fa727002, to K.S.); AMED SCARDA Hokkaido University Institute for Vaccine Research and Development (HU-IVReD) (223fa627005, to T.F.); AMED Project for Advanced Drug Discovery and Development (JP21nf0101627, to T.F.); AMED Research Program on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases (JP21fk0108493, to T.F.; JP22fk0108617, to T.F.; JP22fk0108516, to T.F.; JP22fk0108146, to K.S.; JP21fk0108494 to G2P-Japan Consortium, Shinya T., T.F., and K.S.); AMED CREST (JP21gm1610005, to K.T.; JP22gm1610008, to T.F.); JST PRESTO (JPMJPR22R1, to J.I.); JSPS KAKENHI Fund for the Promotion of Joint International Research (International Leading Research) (JP23K20041 to K.S., and T.F.); JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research B (JP21H02736, to T.F.); JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up (JP25K23813 to Shuhei T.); JSPS Core-to-Core Program (A. Advanced Research Networks) (JPJSCCA20190008, to K.S.); The Cooperative Research Program (Joint Usage/Research Center program) of Institute for Life and Medical Sciences, Kyoto University (to K.S.); the Joint Research Program of Institute for Genetic Medicine, Hokkaido University (to K.Y., and T.T.); International Joint Research Project of the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo (to T.I.); Akiyama Life Science Foundation (to T.T.); Japan Antibiotics Research Association (to T.T.); Hirose Foundation (to T.T.); The Tokyo Biochemical Research Foundation (to K.S.); Takeda Science Foundation (to R.S., T.F., and T.I.); The Uehara Memorial Foundation (to T.I.); Tobe Maki Foundation (to S.S.); Hokkaido University Support Program for Frontier Research (to T.F.); and Tsuchiya Mitsubishi Foundation (to K.S.); Tokuo Fujii Research Fund—Support for Article Processing Charge of International Academic Papers (to Shuhei T.); NIH U19 (AI135990 to M.O.); Roddenberry Foundation (to M.O.); P. and E. Taft (to M.O.); James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust (to M.O.). M.O. is a Chan Zuckerberg Biohub—San Francisco Investigator.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Shuhei T. and S.D. performed cell culture experiments. Shuhei T., R.S., S.S., K.Y., and T.T. performed animal experiments. M.T., L.W., and Shinya T. performed histopathological analysis. S.D. and K.T. prepared human lung organoids and airway-on-a-chip systems. S.D. and K.T. performed antiviral drug tests. H.N. and T.I. performed SARS-CoV-2 S-mediated membrane fusion assays. T.Y.T., J.R., and M.O. designed, performed, and interpreted the VLP experiments. Shuhei T. generated recombinant viruses. J.I. performed phylogenetic and bioinformatics analyses. Shuhei T. performed statistical analyses. Shuhei T., K.S., K.T., Shinya T., T.T., and T.F. designed the experiments and interpreted the results. Shuhei T., T.T., and T.F. wrote the original manuscript. All authors reviewed and proofread the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Hin Chu, Pengfei Li and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsujino, S., Tsuda, M., Deguchi, S. et al. A non-spike nucleocapsid R204P mutation in SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XEC enhances inflammation and pathogenicity. Nat Commun 17, 735 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67455-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67455-4