Abstract

The fabrication of high-performance functional polymer composites requires delicate balance between functionalities, filler content and overall performance, and preparation route is urgently needed. Guided by Simmons theory, a PDMS-based stretchable conductor with metal-level conductivity is realized through a strategy by combining silver nanoparticle in-situ formation, optimized barrier height and volume excluding effect. Firstly, a universal matrix-independent etching-reduction method generates uniform Ag nanoparticles (~ 9.7 nm), shortening tunneling distances. Then, tunneling barrier height is minimized to 0.06 eV by aligning energy levels of surface-treated silver nanoflakes and PDMS, reducing electron scattering. Finally, silver-plated PDMS microspheres act as volume-excluding phase, compressing tunneling widths below the critical threshold (<10 nm). This integrated approach yields exceptional electrical conductivity (29429 S/cm) at 50 wt% Ag loading. Such tunneling networks retain 53% conductivity at 100% strain, while thermal conductivity increases from 4.3 to 24.3 W/m·K. This work demonstrates rational quantum tunneling barrier control to overcome performance trade-offs, providing a design framework for advanced conductive composites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-performance functional polymer composites require robust percolating filler networks for electrical/thermal conductivity and stretchability1,2,3. Physical connections between fillers critically influence functionality by reducing interfacial contact resistance4. Minimizing inter-filler distance is quite important. However, increasing filler concentration beyond the percolation threshold to cut down electron tunneling distance compromises elasticity and processability due to aggregation and restricted polymer mobility5,6. A delicate balance between functionalities, filler content and overall performance is often needed. Advanced strategies have been proposed to decouple functionality from mechanical degradation, including filler welding7, aspect ratios optimization8, spatial alignment9, dispersion control10, and hierarchical structuring11, and incorporating minor auxiliary fillers like metallic nanowires12, carbon nanotubes (CNTs)13 or low-aspect-ratio metallic nanoparticles14,15,16,17 to bridge discontinuous domains. Among them, the generation of uniform silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) surrounding silver nanoflakes (AgFs) shows an order-of-magnitude improvement in electrical conductivity18,19. However, diffusion-dominated Ag⁺ migration causes uncontrolled Ag NPs concentration, hindered in viscous polymers18, and requires matrix reducing groups, failing in silicone elastomers20, despite their wide range of applications. Thus, a universal Ag NPs in situ synthesis strategy remains a challenge.

Meanwhile, preparing strain-insensitive conductivity in stretchable conductors is equally critical and challenging, which demands preserved network integrity under tensile strain21. Conventional conductive composites exhibit strain-dependent resistance increases due to disrupted filler connections22. Strategies accommodate deformation via controlled percolation pathways8 or microstructural modulation11, exemplified by locally bundled Ag nanowires (Ag NWs) assemblies23, ternary self-organization Ag NWs/AgFs/Ag NPs hybrids8, and metal nanowires porous architectures11, which allows further optimization via engineered structural designs24. Meanwhile, largely kept conductivity under strain and filler self-alignment has been observed in AgFs20 and Au NPs based high performance stretchable conductors25 under specific conditions. However, the mechanism is still unclear, and it lacks reproducibility and general applicability. Overall, a generalizable, scalable network modulation strategy has not yet been realized.

Furthermore, high-performance conductive elastomers require understanding electron transport and rational network design. Transport primarily occurs via quantum tunneling across sub-10-nm interparticle gaps26,27. Simmons' theory dictates exponential scaling of tunneling resistance with barrier width (interparticle distance) and is sensitive to barrier height (energy-level mismatch)17,28. While most studies modulate barrier width, systematic co-optimization of both parameters remains unexplored despite being essential for efficient networks. Herein, we propose a Simmons theory-guided strategy by combining silver nanoparticle in situ formation, optimized barrier height and volume excluding effect. Surface-treated AgFs enhance electron affinity and intrinsic conductance. Kelvin probe force microscopy (KPFM) indicates PDMS as the optimal matrix, aligning work functions with AgFs for minimal barrier height (0.06 eV). Subsequently, a universal chemical etching-reduction method generates uniform Ag NPs (~9.7 nm) within PDMS, reducing tunneling distances to ~19.2 nm. Then, incorporating silver-coated PDMS (PAg) microspheres as a volume-excluding phase compresses tunneling widths below the critical cut-off (9.6 nm). This yields a stretchable composite with exceptional conductivity (29429 S/cm) at 50 wt% Ag loading. Meanwhile, the thermal conductivity increases from 4.3 to 24.3 W/m·K thanks to efficient carrier transport. Uniform Ag NPs (1.29 vol%) and optimized tunneling enabled 53% conductivity retention at 100% strain. This demonstrates that such a strategy can overcome intractable performance trade-offs. By elucidating the interplay between filler architecture, matrix properties, and electron transport physics, our strategy provides a guideline for high-performance functional nanocomposites containing silver.

Results

Characterization of PAg microspheres and AgFs

Micron-sized PDMS microspheres are synthesized via suspension polymerization and subsequently coated with a conductive Ag layer to form PAg microspheres. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) (Fig. 1a) reveal that the PAg microspheres exhibit a uniform spherical morphology, with each microsphere uniformly coated with a metallic Ag layer. The particle size distribution (Fig. S1) indicates an average diameter of ~28 μm. Elemental mapping (Fig. 1b) demonstrates distinct distributions of Si and Ag, with the surface dominated by Ag, forming a continuous conductive layer approximately 132 nm thick. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Fig. S2) displays prominent characteristic peaks at 2θ values of 38.1°, 44.3°, 64.5°, 77.4° and 81.5°, corresponding to the (111), (200), (220), (311) and (222) crystal planes of Ag29, confirming a face-centered cubic structure. The Ag content is quantified using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (Fig. S3). Based on the residual weight of PAg (44.4 wt%) and that of pure PDMS (13.8 wt%), the Ag content is calculated to be 64.5 wt%30.

a SEM image and EDS mappings of PAg microspheres; b Cross-sectional SEM image and EDS mapping of bisected PAg microsphere; c XPS spectrum and d SEM images of AgFs treated by alcohol with varying cycles (scale bar: 2 μm); e Conductivity of as-obtained AgFs, alcohol treated AgFs (4 cycles) and intrinsic Ag. Five parallel samples were measured, and error bars represent the standard deviation.

To endow composites with high conductivity, AgFs are employed as the primary conductive filler due to their moderate aspect ratio and intrinsic high conductivity. However, the as-received AgFs are coated with a thin layer of surfactant, typically long-chain unsaturated fatty acids, which can increase inter-flake contact resistance and impair conductivity31. To address this, the AgFs are subjected to multiple washing cycles in boiling ethanol to remove the surfactant. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis (Fig. 1c) reveals distinct C1s and O1s peaks for the unwashed AgFs (0 cycle). After 4 washing cycles, the C1s peak intensity markedly decreases, while the O1s peak remains. This is because ethanol dissolves the fatty acids, eliminating the associated C1s signal, whereas the persistent O1s peak originates from a native oxide layer on AgFs. The ratios of C1s/Ag3d and O1s/Ag3d peak areas, derived from the XPS spectra, are compared in Fig. S4. After washing, the C1s/Ag3d ratio drops from 0.207 to 0.043, confirming the effective removal of physisorbed fatty acids. The residual carbon likely stems from trace amounts of chemically bonded surfactant31 (Fig. S5a). In contrast, the O1s/Ag3d ratio decreases less markedly, from 0.097 to 0.074.

The fine surface structure of the untreated AgFs is obscured by the surfactant coating (Fig. 1d). After surfactant removal, however, the AgFs display a clear surface morphology with well-defined grain boundaries and sharp edges. Additional physical and chemical evidence further supports the effective removal of surfactants (Fig. S5). Consequently, the intrinsic conductivity of AgFs increases from 127540 S/cm to 341438 S/cm, representing a ~ 3-fold enhancement (Fig. 1e). This substantial improvement in conductivity is highly beneficial for constructing highly conductive composites.

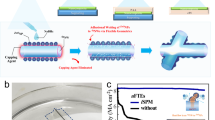

Preparation and electrical properties of PDMS-AgFs-PAg conductor

The fabrication process of PDMS-AgFs-PAg conductive composite is illustrated in Fig. 2a. First, a PDMS precursor mixture is prepared by combining PDMS base, a crosslinking agent (10:1, w/w), and 10 wt% glycerol (Gly). The abundance of electron-donating hydroxyl (-OH) groups in Gly enables it to act as a reducing agent, facilitating the reduction of Ag⁺ to elemental Ag through a redox reaction20. Gly also modifies the mechanical properties of the PDMS matrix (Fig. S6). Next, AgFs and a specific amount of formic acid are incorporated into the matrix. The formic acid removes surface oxides from the AgFs through in situ etching, forming Ag formate (Fig. S7)32. Then, PAg microspheres are added as a volume-excluding phase. The final step involves the chemical crosslinking of the PDMS matrix at 160 °C to form the PDMS-AgFs-PAg conductor. Such high temperature accelerates the decomposition of Ag formate and the redox reactions between Ag+ and the –OH groups of Gly, promoting the formation of Ag nanoparticles (Ag NPs) (Fig. S8). This method enables flexible control over Ag NPs concentration with matrix independence, a capability not yet achieved in other reported systems10,15,20, as discussed in subsequent sections.

a Schematic of the elaboration of PDMS-AgFs-PAg conductor; b Optical images (insert: uncured mixture) and SEM images of crosslinked conductor; c SEM images of retrieved conductive filler from PDMS-AgFs-PAg conductor (scale bar: 100 nm); Conductivity of conductors (d) treated by varying concentrations of formic acid and (e) filled with untreated AgFs (W/ Ag2O), AgFs with removed Ag2O layer (W/O Ag2O) and AgFs with in situ synthesized Ag NPs (W/Ag NPs). Five parallel samples were measured, and error bars represent the standard deviation for (d, e).

Fig. 2b (insert) presents digital photographs of uncured, grease-like PDMS-AgFs-PAg mixture. After crosslinking the PDMS matrix, a stretchable conductor with a smooth surface and a golden hue was obtained. SEM images reveal that PAg microspheres are uniformly dispersed within PDMS-AgFs. Magnified view (20k ×) identifies several large Ag NPs, and higher-magnification imaging (200k ×) further shows numerous uniformly dispersed Ag NPs throughout the PDMS matrix, which are expected to enhance conductivity.

Maximizing electrical conductivity requires the complete removal of the Ag₂O surface layer from AgFs. XRD spectra (Fig. S9a) confirm the presence of an oxide layer, in situ etching and conversion to silver formate (Ag(HCOO)), and the subsequent reduction to metallic Ag33. To investigate its effect on AgFs microstructure and conductor properties, the formic acid content is systematically varied from 10 to 40 μL/g. At 40 μL/g, the complete disappearance of Ag2O peaks (Fig. S9b) indicates thorough etching and reduction. TEM images and derived O/Ag signal ratio (Fig. S10) reveal that the O signal decreases from 3.6% in untreated AgFs to 0.2% at 40 μL/g. Furthermore, numerous Ag NPs are observed around the treated AgFs. The crystal structure of the etched AgFs (Fig. S11) further validates the complete removal and conversion of the Ag2O layer. SEM images (Fig. 2c) show Ag NPs populated among adjacent AgFs, which serve as electron bridges to enhance electron hopping within the matrix.

The formic acid concentration critically modulates the chemical etching and in situ reduction process, directly determining the ultimate electrical conductivity. The control composite without formic acid treatment (0 μL/g) contains only AgFs (Fig. S12a). In contrast, treated composites exhibit secondary conductive Ag NPs between AgFs, with their abundance increasing with formic acid concentration. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Fig. S12b) results further show two distinct peaks corresponding to AgFs and in situ formed Ag NPs, respectively. Figure 2d compares the conductivity of PDMS-AgFs-PAg composites (45 wt% AgFs, 10 wt% PAg) at different formic acid concentrations. Without etching, conductivity is merely 3.6 S/cm, escalating to 1483 S/cm at 40 μL/g. Beyond this concentration, conductivity declines due to over-etching-induced defects in AgFs (Fig. S13). Therefore, 40 μL/g is selected as the optimal content for subsequent analyses. The proposed strategy uniquely leverages Ag₂O layers-eliminating their insulating barriers while converting them into functional Ag NPs (Fig. 2e). Moreover, this dual optimization allows controllable Ag NPs synthesis, distinguishing it from methods that consume pristine AgFs to generate Ag NPs17,34,35.

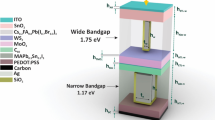

Percolation modulation based on the simmons theory

Electron transport in conductive composites occurs via the quantum tunneling effect, whereby electrons tunnel through a thin insulating layer between adjacent conductive fillers36. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, in the PDMS-AgFs-PAg composite, neighboring AgFs serve as electrodes separated by PDMS. The tunneling barrier width (d) equates to inter-filler distance, while the barrier height (λB) is governed by the difference between the work function of AgFs (φAg) and the electron affinity of PDMS matrix (χP)28. Simmons theory quantifies the electron tunneling current density (J) at low applied voltages (V) as a function of d and λB:

where me is the electron mass, h is Planck’s constant, and e is the electronic charge. Adjusting the distance between conductive fillers varies the tunneling barrier width, while selecting polymer matrices with different electron affinities tunes the barrier height.

a Schematic illustration of the Ag-polymer-Ag tunneling junction; b TEM images of PDMS-AgFs-PAg without (0 μL/g) and with (40 μL/g) formic acid treatment (scale bar: 100 nm) and (c) statistical distributions of Ag NPs size and tunneling distances; d Energy level distributions of PDMS and AgFs obtained by KPFM; e The energy band alignment diagram of AgFs, PDMS, SBS, TPU and TPAE; Comparisons of (f) electrical conductivities and (g) electrical-mechanical behaviors of conductors with varying elastomer matrices. Five parallel samples were measured, and error bars represent the standard deviation for (f).

The distribution of conductive fillers within PDMS-AgFs-PAg composite is systematically analyzed (Fig. 3b). Compared to the untreated composite, a substantial number of Ag NPs are synthesized and uniformly dispersed within the PDMS matrix, effectively reducing the inter-particle tunneling distance. As depicted in Fig. 3c, the Ag NPs exhibit a size distribution ranging from 1.8 to 12 nm, with an average size (s) of 9.8 nm and an estimated concentration of 1.29 vol% (Fig. S14). The resulting tunneling distance distribution in PDMS-AgFs-PAg composite ranges from 2.1 to 47.6 nm, with an average value of 19.2 nm. In contrast, the composite without Ag NPs shows a much larger tunneling distance (> 500 nm). This effective percolation modulation strongly promotes high conductance, as predicted by Simmons' theory. Moreover, the tunneling distance overlaps with the tunneling cut-off distance (10 nm), which facilitates efficient electron transport.

The work function of AgFs (φAg) and the electron affinity of PDMS matrix (χPDMS) are measured using KPFM (Fig. S15a). The values of φAg and χPDMS are extracted from the surface potential distribution images. Surface potential can be influenced by factors such as surface chemical adsorption, surface roughness, and chemical purity37,38, leading to a broad potential distribution (Fig. S15b). Based on these results, the energy level distributions of PDMS and AgFs are calculated (Fig. 3d). The surface potential of PDMS corresponds to an electron affinity of 4.76 eV, showing significant overlap with the work function of AgFs (4.70 eV). This close alignment yields a negligible barrier height (λB = 0.06 eV), which greatly facilitates charge transport and contributes to the composite’s high conductance.

Using AgFs as conductive filler, the barrier height (λB) can be modulated by selecting polymer matrices with varying electron affinities39. To validate the rationale for choosing PDMS, several elastomers, including styrene-butadiene-styrene copolymer (SBS), thermoplastic polyurethane elastomer (TPU), and thermoplastic polyester elastomer (TPAE), are investigated (Fig. 3e). Their electron affinities differ significantly from φAg, resulting in increased barrier heights of 0.13 eV (SBS), 0.51 eV (TPU), and 0.86 eV (TPAE). This increase correlates with a clear decline in conductivity (Fig. 3f). At a fixed Ag loading (45 wt%, 10 wt% PAg), conductivity drops from 1483 S/cm (PDMS) to 1037 S/cm (SBS), 829 S/cm (TPU), and 472 S/cm (TPAE). Since barrier widths, Ag NP sizes and conductive fillers (AgFs, PAg) dispersion state remain identical across systems (Figs. S16, S17), the reduced conductivity is primarily attributed to the increased barrier heights. These findings confirm the universality of the proposed in situ Ag NPs generation strategy, which is independent of the type of polymer matrix, providing a versatile and effective method for optimizing the electrical performance of conductive composites.

According to Simmons' theory, large barrier height amplifies the resistance change under strain, resulting in high strain sensitivity14. As shown in Fig. 3g, the PDMS-AgFs-PAg composite (45 wt%, 10 wt% PAg) exhibits the lowest strain sensitivity. This behavior stems from a negligible barrier height (λB ~ 0.06 eV), which permits electrons to tunnel efficiently through the PDMS conduction band. Moreover, the short travel distance (19.2 nm) between Ag NPs minimizes stretch-induced electron scattering. In summary, by precisely modulating the tunnel distance and matching the energy levels of polymer-filler, we realized a highly conductive PDMS-AgFs-PAg conductor that maintains excellent conductivity retention under strain.

Volume-excluding-induced network formation

Subsequently, the tunneling distance is further minimized by tailoring the PAg content. Owing to the volume excluding effect, a higher PAg content confines the conductive fillers (AgFs, Ag NPs) into a smaller matrix volume, promoting the formation of localized, efficient conductive pathways. As shown in Fig. 4a, the incorporation of 10 wt% PAg microspheres boosts the conductivity by ~4 orders of magnitude compared to the PAg-free composite (total Ag content: 45 wt%). Such dramatic enhancement stems from the localized densification of the conductive network, as schematized in Fig. 4b. Although the PAg-free composite (PDMS-AgFs) generates numerous Ag NPs, the interparticle distance remains insufficient for efficient conduction. In contrast, the PAg microspheres act as a passive filler that compresses the available space, effectively ‘squeezing’ the AgFs and Ag NPs phases. This selective distribution increases their local concentration and drastically reduces the tunneling distance, thereby accounting for the substantial conductivity increase.

a Electrical conductivity and (b) schematic illustration of the microstructure of PDMS-AgFs without and with PAg (10 wt%); c Electrical percolation and (d) fitted results according to the power-law equation of PDMS-AgFs conductors without and with PAg (10 wt%), as well as AgFs-filled PDMS without Ag NPs; e Electrical conductivity, f TEM images and (g) tunneling distance distributions of PDMS-AgFs-PAg conductors with different PAg contents. Five parallel samples were measured, and error bars represent the standard deviation for (a, c, E).

To further demonstrate the superiority of PAg in enhancing electrical percolation, the percolation curves of PDMS-AgFs-PAg composites without and with PAg, as well as AgFs-filled PDMS without Ag NPs, are presented (Fig. S18). The PAg-containing composite exhibits markedly higher conductivity, particularly within the critical 35–55 wt% filler range. To gain deeper insights into the conductive mechanisms, we analyzed the data using the power-law equation from percolation theory40, which describes the conductivity as follows:

where σ is the composite conductivity, σ0 is a proportionality factor related to the filler conductivity, V and Vc represent the filler volume fraction and percolation threshold, respectively, and t is the critical exponent.

The weight fraction of Ag from Fig. S18 is converted to volume fraction for analysis (Fig. 4c). According to the best-fit results (Fig. 4d), a percolation threshold (Vc) of 5.1 vol% is determined for PDMS-AgFs-PAg composite, which is 1.1 vol% lower than that of PDMS-AgFs (6.2 vol%). This reduction is attributed to the volume-excluding effect of PAg microspheres. Furthermore, the conductivity-filler content relationship for PDMS composites filled solely with AgFs is calculated. As shown in Fig. 4c, d (blue curves), these composites exhibit a higher Vc of 9.4 vol%, indicating that the in situ growth of Ag NPs effectively reduces Vc from 9.4 vol% to 6.2 vol%. Together, these findings highlight the synergistic effect of in situ Ag NPs formation and volume-excluding effect in regulating the percolation behavior of composites, enabling high conductivity at low filler contents.

The conductivity of PDMS-AgFs-PAg composite is further optimized by increasing the PAg microsphere content (Fig. 4e). Across the 30–60 wt% filler range, a higher PAg content substantially enhances conductivity. For instance, at a fixed 40 wt% total Ag loading, the conductivity escalates from 2.8 × 10−4 S/cm (0 wt% PAg) to 0.3 S/cm (10 wt% PAg) and ultimately 6544 S/cm (50 wt% PAg), representing an increase of ~7 orders of magnitude. Notably, at 50 wt% Ag content, the composite with 50 wt% PAg achieves a metal-like conductivity of 29429 S/cm. Once a dense conductive network forms, further increases in Ag content yield diminishing returns. To visualize this volume-exclusion effect, we examined the composite’s microstructure (Figs. 4f, S19). The introduction of PAg continuously increases the local concentration of AgFs and Ag NPs, drastically reducing the inter-particle distance. With 10 wt% PAg, the composite shows a broad tunneling distance distribution (1.2–48.3 nm) and an average of 20.7 nm (Fig. 4g). This distance is effectively reduced to 15.5 nm and 9.6 nm at 30 wt% and 50 wt% PAg, respectively. The shortened tunneling distance facilitates efficient electron transport, underpinning the dramatic conductivity enhancement.

Generally, enhancing composite conductivity often compromises stretchability41. Interestingly, our PDMS-AgFs-PAg composite simultaneously improves both properties at PAg contents between 0 and 30 wt% (Fig. 5a). The conductivity increases monotonically with PAg content, reaching 29429 S/cm at 50 wt%. Conversely, stretchability first increases, peaks at 30 wt% PAg, and then decreases, defining an optimal balance. Thus, application-specific selection of PAg content is essential to effectively harness the resultant conductivity-stretchability trade-off. This optimal PAg content also enables robust conductivity retention under strain (Fig. 5b). In contrast to the PAg-free composite, which fails mechanically below 150% strain, PAg-containing counterparts maintain high conductivity within the 0–150% strain range. Notably, the composite with 30 wt% PAg retains high conductivity even at 222% strain. The diminished strain tolerance beyond this optimal content is likely due to crack formation induced by the heavily loaded rigid filler.

a Electrical conductivities and stretchability, and (b) electrical-mechanical behavior of conductors at different PAg contents; Normalized conductivity changes (σ/σ0) of conductors under (c) elevated temperatures and (d) cyclic heating-cooling (25–200–25 °C per cycle) for 20 times; Comparisons of (e) conductivity-filler content (Table S1) and (f) electrical retention (σ/σ0 at 100%)-conductivity (Table S2) with recently reported results based on Ag nanomaterials. Five parallel samples were measured, and error bars represent the standard deviation for (a, c, d).

For practical applications, maintaining effective conductivity under various external perturbations is as crucial as achieving high conductivity over a wide strain range. The mechanical robustness of the conductor was evaluated through cyclic stretching (Fig. S20). Remarkably, it shows negligible fatigue, with minimal degradation in conductivity after 1000 cycles. Furthermore, the temperature dependence of conductivity was investigated (Fig. 5c). As the temperature increases from 25 °C to 200 °C, the conductivity of the composite displays a unique V-shaped trend. The initial decrease is attributable to the thermal expansion of the PDMS matrix, which dilutes the filler concentration, while the subsequent increase at higher temperatures is likely due to thermal welding between adjacent AgFs35. The composite also exhibits efficient thermal stability, demonstrated by a minimal resistance deviation of only 0.8% over 20 heating-cooling cycles (Fig. 5d). Finally, a two-week reliability test was conducted (Fig. S21). After the damp heat aging process, the internal Ag NPs showed unobservable migration or aggregation, which effectively preserved the electrical conductivity.

Previous stretchable conductors typically require conductive filler contents exceeding 80 wt% to achieve conductivities above 10000 S/cm29,42,43. In contrast, the present work achieves a high conductivity of 29429 S/cm at a markedly lower Ag content (Fig. 5e). Additionally, due to the narrow barrier width and negligible barrier height, the composites exhibit exceptional conductivity retention under large strains. As shown in Fig. 5f, which compares the normalized conductivity (σ/σ₀) at 100% strain, the PDMS-AgFs-PAg composite simultaneously delivers high conductivity and superior electromechanical stability.

Thermal conductivity of PDMS-AgFs-PAg composites

According to the Wiedemann-Franz law, the electrical conductivity (σ) and thermal conductivity (k) of a composite are related as follows44:

where κB is the Boltzmann constant, e is the electronic charge, T is the temperature in Kelvin (K), and L is the Lorenz number (2.44 × 10−8 WΩ/K for free electrons). Since the ratio k/σ is constant, the high electrical conductivity of PDMS-AgFs-PAg suggests that the composite may also exhibit satisfactory thermal conductivity.

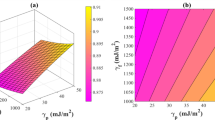

At a fixed total Ag loading (50 wt%), the thermal conductivity of composites with varying PAg content (10–50 wt%) is investigated (Fig. 6a, Table S3). Both in-plane and out-of-plane thermal conductivity increased monotonically with PAg content, rising from 9.7 to 24.3 W/(m·K) and from 7.7 to 11.9 W/(m·K), respectively. This monotonic increase is attributed to the formation of additional thermally conductive pathways45,46,47, while the observed anisotropy stems from the preferential in-plane orientation of AgFs48,49. To elucidate the contributing factors, three systems at identical Ag content are compared (Fig. 6b): (i) AgFs only, (ii) AgFs with in situ Ag NPs, and (iii) the synergistic combination of Ag NPs and volume-excluding effect from PAg. The in situ formation of Ag NPs enhanced the in-plane (out-of-plane) thermal conductivity from 4.8 (4.3) to 9.7 (7.7) W/(m·K). A more substantial improvement is induced by the volume-excluding effect, elevating conductivity to 24.3 (11.9) W/(m·K). Meanwhile, the enhancement in thermal conductivity is accompanied by a progressive intensification of anisotropic behavior, which arises from the increasingly aligned orientation of AgFs (Fig. S22). Using Eq. (3), the electron-contributed thermal conductivity (ke) is quantified (Fig. 6c). Due to the significant enhancement in electrical conductivity, ke increases sharply with PAg content, surging from 4.16 (10 wt% PAg) to 21.4 W/(m·K) (50 wt% PAg). Consequently, the relative contribution of electrons to the total thermal conductivity increased from 42.9% to 86.3%.

a Thermal conductivity and thermal diffusivity of PDMS-AgFs-PAg composites with altered PAg content; b Thermal conductivity comparison of AgFs-filled PDMS, PDMS-AgFs composite and PDMS-AgFs-PAg composite (50 wt% PAg) at consistent Ag content (50 wt%); c Electron contributed thermal conductivity and contribution ratio of composites with different PAg contents; d Comparison of TCE of PDMS-AgFs-PAg with reported composites (Table S4). Five parallel samples were measured, and error bars represent the standard deviation for (a, b, c).

To evaluate the efficacy of the proposed percolation modulation strategy, the thermal conductivity enhancement (TCE) of PDMS-AgFs-PAg is compared with recently reported metal-polymer composites. TCE is defined as49:

where kc and kp represent the thermal conductivity of PDMS-AgFs-PAg and PDMS, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6d, the TCE values achieved in this work significantly outperform those in the literature. This exceptional performance primarily stems from two mechanistic factors: (i) optimized energy-level alignment between the AgFs and PDMS matrix, which minimizes electron scattering, and (ii) a modulated tunneling barrier width that enhances the probability of electron hopping between adjacent conductive particles. The advantage of our strategy is further underscored in Fig. S23, where the TCE per 1 vol% filler content for PDMS-AgFs-PAg (8.7 vol% Ag) is compared against other metal-filled composites, demonstrating the superior efficiency in enhancing the thermal conductivity of PDMS.

Discussion

Guided by Simmons' theory, we present a high-performance PDMS-AgFs-PAg composite with exceptional electrical and thermal properties. The design involves a multi-faceted strategy. First, purified AgFs are incorporated into the PDMS matrix, followed by a controllable chemical etching and in situ reduction process to generate Ag NPs, which shortens the tunneling distance to ~19.2 nm. Concurrently, matrices with varying electron affinities are screened to achieve an optimized energy level alignment, yielding a negligible barrier height of 0.06 eV that minimizes electron scattering. Furthermore, the introduction of conductive PAg microspheres as a volume-excluding phase further compresses the tunneling width to 9.6 nm. The synergy of a narrow tunneling distance and negligible barrier height enables the composite to achieve an ultrahigh conductivity of 29429 S/cm at a low Ag content of 50 wt%, while retaining > 50% of initial conductivity under 100% strain. This synergistic percolation modulation also yields a notable in-plane thermal conductivity of 24.3 W/(m·K), corresponding to a remarkable TCE of 12050% that significantly surpasses state-of-the-art values. In summary, this work provides a universal strategy for designing high-performance conductive elastomers by rationally modulating the conductive network based on electron tunneling principles.

Methods

Raw materials

Sylgard 184 PDMS elastomer kit was produced by Dow Corning Corporation. Silver nanoflakes (AgFs) was kindly provided by Bohuas Nanotechnology (Ningbo, China) Co., Ltd. Glycerol (AR, ≥ 99.7%) was purchased from Titan Technology (Shanghai, China) Co., Ltd. Anhydrous ethanol (AR, ≥ 99%), formic acid (AR, ≥ 99%), tin chloride dehydrate (SnCl2·2H2O, AR, ≥ 99%), silver nitrate (AgNO3, 1 M), ammonia (NH₃·H₂O, 7 M) and potassium sodium tartrate (AR, ≥ 99%) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Synthesis of PAg microspheres

The synthesis procedure for PAg microspheres is as follows: PDMS crosslinker and matrix in a volume ratio of 1:10 were mixed in a planetary mixer (AR 100, Thinky) for 5 min to obtain 22 mL PDMS precursor mixture. Then, the PDMS mixture was loaded in a syringe (10 G) and slowly injected into 300 mL DI water. Simultaneously, an emulsification disperser (IKA Magic Lab) was utilized to apply high-speed shear (15000 rpm) at 80 °C. After 1 h, a crosslinked PDMS microsphere suspension was synthesized. Further, PDMS microspheres were separated from water by vacuum filtration, which was followed by drying at 60 °C for collection. Meanwhile, a 500 mL SnCl2 aqueous solution at a concentration of 5 mg/mL was formulated. Then, 10 g dried PDMS microspheres, 100 mL silver ammonia solution (14 mg/mL), and 100 mL potassium sodium tartrate aqueous solution (20 mg/mL) were uniformly dispersed in the above solution. This Ag-plating ink was stirred at room temperature for 2 h (500 rpm). Finally, the obtained Ag-coated PDMS (PAg) microspheres were collected by vacuum filtration and dried thoroughly at 60 °C for further use.

Surface pretreatment of AgFs

First, AgFs (20 g) were added to a flask containing 200 mL ethanol, and the dispersion was stirred at 70 °C for 10 min (500 rpm). Then, the dispersion was allowed to stand for 1 h, and the settled AgFs at the bottom were collected. Next, the collected AgFs were redispersed in fresh ethanol, and the above operation was cycled 4 times. Finally, the treated AgFs were separated and dried under vacuum for 12 h to obtain surface-treated AgFs.

Preparation of PDMS-AgFs-PAg composites

First, PDMS matrix and crosslinker in a volume ratio of 10:1 were uniformly mixed. Then, 10 wt% glycerol (Gly), an appropriate amount of AgFs, and formic acid were added to the PDMS mixture (Note that for composites without removing the Ag oxide layer, formic acid was not introduced, while other experimental parameters maintain unchanged). After homogeneously mixing, the mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature for 24 h to ensure thoroughly reaction between formic acid and the surface oxide layer of AgFs. The volume fraction of AgFs is 25–60 wt%, and the content of formic acid is 0–40 μL (per gram of AgFs). Further, PAg microspheres were homogeneously blended into the above composite. The mass fraction of PAg is 0–50 wt%, and the amount of AgFs was adjusted appropriately according to the content changes of each component, ensuring the total Ag content remains constant (the mass fraction of Ag in PAg is 64.5 wt%). Finally, the obtained blends were cast onto a PDMS substrate and thermally crosslinked at 160 °C for 2 h to obtain a stretchable PDMS-AgFs-PAg conductor.

Preparation of PDMS-AgFs-PAg composites without Ag NPs

First, purified AgFs were uniformly mixed with formic acid (40 μL/g) to etch the surface Ag2O layer. The etching process lasted for 12 h at 25 °C and then repeatedly rinsed with ethanol to completely remove the exfoliated Ag formate particles, which is followed by drying in a vacuum oven (60 °C, 8 h). Next, the etched AgFs were uniformly mixed with PDMS (containing 10 wt% Gly) matrix and PAg to elaborate a composite mixture (for the cases of AgFs-filled PDMS composites without Ag NPs, PAg was not introduced). Finally, the mixture was cast onto the PDMS substrate and cured at 160 °C for 2 h to obtain PDMS-AgFs-PAg composites without Ag NPs.

Characterization

The morphologies of PAg microspheres, AgFs, and PDMS-AgFs-PAg composites were characterized using a Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FEI-SEM, Quanta 650 ESEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) equipped with an Energy Dispersive Spectrometer (EDS, OXFORD Xplore 30). The surface potentials of PDMS and AgFs were measured using Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM, Bruker, Icon, USA) with a gold-coated silicon AFM tip. Prior to measurement, KPFM was calibrated based on the contact potential difference between the tip and highly oriented pyrolytic graphite with a known work function (4.6 eV). The microstructure of AgFs and composites, as well as the thickness of AgFs, were characterized using an Atomic Force Microscope (AFM, Bruker, Icon, USA). The lattice structure and surface elements of AgFs were analyzed using a Scanning Transmission Electron Microscope (STEM, Talos F200i, Thermo Scientific). When analyzing the conductive network in PDMS-AgFs-PAg composites, the composites were sliced using Focused Ion Beam (FIB) technology before characterization. The chemical composition and bonding type analysis of surfactant on AgFs were conducted on an FTIR (Nicolet 6700, Thermo Scientific, USA) within a scanning wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm−1, with 32 scans performed. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) tests were conducted on a Thermo ESCALAB 250 XPS spectrometer under a pressure of 2.0 × 10−7 Pa, using Al Kα (hv = 1486.6 eV) as the X-ray source. Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted using a TGA instrument (Q500, TA, USA). The test was performed under a nitrogen (N2) atmosphere within a temperature range of 25–800 °C, with a heating rate of 10 °C/min. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) of AgFs was collected using a DSC 8000 (PerkinElmer), heated from room temperature to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under an N2 atmosphere. The thermal diffusivity (α) and specific heat capacity (Cp) of the composites were determined using the laser flash method with an LFA 467 analyzer (NETZSCH, Germany). Thermal conductivity (k) was further calculated according to: k = α × Cp × ρ, where the composite density (ρ) was measured using Archimedes’ Law method. For each sample, the final reported value represents the average of at least five independent measurements. The mechanical properties of PDMS film were tested on a universal tensile testing machine (SANS CMT 40000) at a temperature of 25 °C and a relative humidity of approximately 60%, using a sensor with a load of 100 N. The conductivities of PDMS-AgFs-PAg composites and AgFs were measured using the four-probe method (JCY3100, Xi’an Hechuang Electronic Technology Co., Ltd.), with the average of five measurements taken as the result. Resistance changes under strain were obtained using the two-point method with a JK2512B DC low resistance tester (Jinko, China), equipped with a universal tensile testing machine (SANS CMT 40000) to apply synchronous strain. Prior to testing, both ends of the specimen were coated with a uniform layer of conductive silver paint to minimize contact resistance. The composition and crystal structure of PAg, AgFs, and PDMS-AgFs-PAg composites were characterized using XRD (Bruker D8). The Cu-Kα X-ray source was used with a voltage of 40 kV, a current of 40 mA, a scanning range of 10–90°, and a scanning speed of 10 °/min. Particle size and particle size distribution were obtained using Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS, Zeta PALS 190 Plus, Brookhaven). The intrinsic conductivity of AgFs was measured using a four-point probe method. Prior to the measurement, an appropriate mass of AgFs was pressed into a pellet with a thickness of 100 μm under a pressure of 100 MPa.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information. Additional datasets related to this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Lee, W. et al. Universal assembly of liquid metal particles in polymers enables an elastic printed circuit board. Science 378, 637 (2022).

Lv, J. et al. Printed sustainable elastomeric conductor for soft electronics. Nat. Commun. 14, 7132 (2023).

Guo, Y. Q. et al. Consistent thermal conductivities of spring-like structured polydimethylsiloxane composites under large deformation. Adv. Mater. 36, 2404648 (2024).

Kim, D. C. et al. Material-based approaches for the fabrication of stretchable electronics. Adv. Mater. 32, 1902743 (2020).

Choi, S. et al. High-performance stretchable conductive nanocomposites: materials, processes, and device applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 1566 (2019).

Mi, X. et al. Ink formulation of functional nanowires with hyperbranched stabilizers for versatile printing of flexible electronics. Nat. Commun. 16, 2590 (2025).

Jung, D. et al. Highly conductive and elastic nanomembrane for skin electronics. Science 373, 1022 (2021).

Jung, D. et al. Adaptive self-organization of nanomaterials enables strain-insensitive resistance of stretchable metallic nanocomposites. Adv. Mater. 34, 2200980 (2022).

Yun, G. et al. Liquid metal-filled magnetorheological elastomer with positive piezoconductivity. Nat. Commun. 10, 1300 (2019).

Wang, T. et al. Printable and highly stretchable viscoelastic conductors with kinematically reconstructed conductive pathways. Adv. Mater. 34, 2202418 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Phase-separated porous nanocomposite with ultralow percolation threshold for wireless bioelectronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 1158–1167 (2024).

Lee, S. et al. Ag nanowire reinforced highly stretchable conductive fibers for wearable electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 3114 (2015).

Lee, B. et al. Omnidirectional printing of elastic conductors for three-dimensional stretchable electronics. Nat. Electron. 6, 307 (2023).

Ajmal, C. M. et al. Invariable resistance of conductive nanocomposite over 30% strain. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn3365 (2022).

Faseela, K. P. et al. In situ regeneration of oxidized copper flakes forming nanosatellite particles for non-oxidized highly conductive copper nanocomposites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2304776 (2023).

Ajmal, C. M. et al. In situ reduced non-oxidized copper nanoparticles in nanocomposites with extraordinary high electrical and thermal conductivity. Mater. Today 48, 59 (2021).

Suh, D. et al. Electron tunneling of hierarchically structured silver nanosatellite particles for highly conductive healable nanocomposites. Nat. Commun. 11, 2252 (2020).

Matsuhisa, N. et al. Printable elastic conductors by in situ formation of silver nanoparticles from silver flakes. Nat. Mater. 16, 834 (2017).

Matsuhisa, N. et al. Printable elastic conductors with a high conductivity for electronic textile applications. Nat. Commun. 6, 7461 (2015).

Kim, S. H. et al. An ultrastretchable and self-healable nanocomposite conductor enabled by autonomously percolative electrical pathways. ACS Nano 13, 6531 (2019).

Cheng, M. et al. Recent development on the design, preparation, and application of stretchable conductors for flexible energy harvest and storage devices. Susmat 4, e204 (2024).

Lim, C. et al. Facile and scalable synthesis of whiskered gold nanosheets for stretchable, conductive, and biocompatible nanocomposites. ACS Nano 16, 10431 (2022).

Jung, D. et al. Metal-like stretchable nanocomposite using locally-bundled nanowires for skin-mountable devices. Adv. Mater. 35, 2303458 (2023).

Park, J. et al. Electromechanical cardioplasty using a wrapped elasto-conductive epicardial mesh. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 344ra86 (2016).

Kim, Y. et al. Stretchable nanoparticle conductors with self-organized conductive pathways. Nature 500, 59 (2013).

Chanthbouala, A. et al. Solid-state memories based on ferroelectric tunnel junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 101 (2012).

Alayli, M., Faseela, K. P. & Baik, S. Surface energy governs the electrical conductivity of polymer-matrix composites. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 8, 243 (2025).

Simmons, J. G. Generalized formula for the electric tunnel effect between similar electrodes separated by a thin insulating film. J. Appl. Phys. 34, 1793 (1963).

Tian, K. et al. Evaporation-induced closely-packing of core-shell PDMS@Ag microspheres enabled a stretchable conductor with ultra-high conductance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2308799 (2023).

Duan, Y. et al. Modulus matching strategy of ultra-soft electrically conductive silicone composites for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Chem. Eng. J. 472, 144934 (2023).

Zhao, J. et al. Skin-integrated electrodes based on room-temperature curable, highly conductive silver/polydimethylsiloxane composites. Small 20, 2309470 (2024).

Puzan, A. N., Baumer, V. N. & Mateychenko, P. V. Structure and decomposition of the silver formate Ag(HCO2). J. Solid State Chem. 246, 264 (2017).

Mou, Y. et al. A novel thermal conductive Ag2O paste for thermal management of light-emitting diode. Mater. Lett. 316, 132022 (2022).

Ma, R. et al. Extraordinarily high conductivity of stretchable fibers of polyurethane and silver nanoflowers. ACS Nano 9, 10876 (2015).

Mistry, K., Yavuz, M. & Musselman, K. P. Simulated electron affinity tuning in metal-insulator-metal (MIM) diodes. J. Appl. Phys. 121, 184504 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Tuning surface states of metal/polymer contacts toward highly insulating polymer-based dielectrics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 46142 (2021).

Li, W. & Li, D. Y. On the correlation between surface roughness and work function in copper. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 64708 (2005).

Ajmal, C. M. et al. Absence of additional stretching-induced electron scattering in highly conductive cross-linked nanocomposites with negligible tunneling barrier height and width. Adv. Sci. 11, 2409337 (2024).

Li, J. & Kim, J.-K. Percolation threshold of conducting polymer composites containing 3D randomly distributed graphite nanoplatelets. Compos. Sci. Technol. 67, 2114 (2007).

Sakorikar, T. et al. A guide to printed stretchable conductors. Chem. Rev. 124, 860 (2024).

Boland, C. S. et al. Sensitive electromechanical sensors using viscoelastic graphene-polymer nanocomposites. Science 354, 1257 (2016).

Ajmal, C. M., Bae, S. & Baik, S. A superior method for constructing electrical percolation network of nanocomposite fibers: in situ thermally reduced silver nanoparticles. Small 15, 1803255 (2019).

Sangwook, L. et al. Anomalously low electronic thermal conductivity in metallic vanadium dioxide. Science 355, 371 (2017).

Zhang, H. T. et al. Liquid crystal-engineered polydimethylsiloxane: enhancing intrinsic thermal conductivity through high grafting density of mesogens. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 64, e202500173 (2025).

Guo, Y. Q. et al. Enhancing hydrolysis resistance and thermal conductivity of aluminum nitride/polysiloxane composites via block copolymer-modification. Polymer 323, 128189 (2025).

Han, Y. X. et al. Highly thermally conductive aramid nanofiber composite films with synchronous visible/infrared camouflages and information encryption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401538 (2024).

Jaleel, S. A. A., Kim, T. & Baik, S. Covalently functionalized leakage-free healable phase-change interface materials with extraordinary high-thermal conductivity and low-thermal resistance. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300956 (2023).

Chen, L. et al. Near-theoretical thermal conductivity silver nanoflakes as reinforcements in gap-filling adhesives. Adv. Mater. 35, 2211100 (2023).

Ma, X. et al. Enhancing thermal conductivity in polysiloxane composites through synergistic design of liquid crystals and boron nitride nanosheets. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 231, 54 (2025).

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Key Research & Development Plan (2022YFA1205200).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ke Tian and Hua Deng conceived this project and wrote and revised the manuscript. Ke Tian performed the experiments and characterizations. Hua Deng and Qiang Fu supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Junwei Gu, Zunfeng Liu, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tian, K., Jing, J., Wen, M. et al. Designing functional filler networks via in situ silver nanoparticles through barrier tuning and volume exclusion. Nat Commun 17, 728 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67461-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67461-6