Abstract

Moiré superlattices created by twistronics generate flat bands for enabling localization in topological and quantum system. Most prior realizations rely on nonlinear interactions among electrons, photons, or other particles to achieve moiré-driven localization. However, the intrinsically diffusive and momentum-free nature of thermal conduction poses a fundamental challenge to implementing moiré physics in a linear regime. In contrast to exploiting nonlinearity, we demonstrate moiré-induced thermal localization in a linearly coupled bilayer conductive system with spatially engineered diffusivity. By tuning the twist angles, we create both commensurate and incommensurate moiré patterns, each governed by two distinct modulated wavevectors controlling global periodicity and local unit-cell structure. Aperiodic thermal localization emerges in incommensurate quasicrystals with the transition threshold linked to the emergent lattice constant. Our results establish a paradigm for implementing moiré physics in a static, linear, and momentum-free diffusive system, offering a route to geometrically programmable non-equilibrium control in heat and mass transport.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Moiré physics has emerged as a powerful framework for engineering correlated and topological phases across condensed matter systems, offering unprecedented tunability through geometric interference. These phenomena arise from the superposition of two or more periodic structures with a tailored twist angle1, where the interference between stacked periodicities generates a large-scale modulation known as a moiré pattern. This emergent superlattice modifies the original crystalline structure by introducing a new lattice constant and spatial symmetry, thereby reshaping the system properties for investigating correlated2,3,4, topological5,6,7, and quantum behaviors8,9,10. This principle gained particular attention with the discovery of magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene, where a specific twist induces flat electronic bands and unconventional superconductivity11. The geometrical tuning of moiré patterns thus provides a powerful alternative to engineering interactions directly12,13, offering a platform to manipulate localization-delocalization transitions and symmetry-protected band structures14,15. This paradigm has extended well beyond electronic systems to include van der Waals heterostructures16,17, and optical lattices18. A common thread among these advances is their reliance on nonlinear interactions of versatile platforms to unlock moiré-induced band modifications and topological responses1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Specifically, these corresponding moiré-induced behaviors arise from interference effects in momentum-carrying modes, where the underlying dynamics are described by effective tight-binding Hamiltonians for the ideal case of a non-interacting model or nonlinear Schrödinger-type equations for an interacting model19. While such models can often be approximated in a mean-field sense as linear, the intrinsic physical mechanisms responsible for band formation, such as electronic correlations20 and Kerr nonlinearity18,21, still rely on the presence of momentum space and, frequently, on nonlinear coupling. Though some recent works demonstrated rotationally symmetric moiré superlattices22 and dispersion modulation23 with linear coupling frameworks in classical wave dynamics, these works still possess real-space momentum for supporting well-defined band structures governed by a non-interacting momentum-carrying model19.

More recently, moiré physics has entered the domain of dissipative systems through the development of hydrodynamic moiré superlattices24, where advection-driven nonlinearity enables spatial thermal localization and flat-band formation (Fig. 1a, b). In such thermofluidic systems, twist angles and lattice mismatches provide continuous control over energy localization patterns, akin to those observed in condensed matter analogs. Building on this foundation, several discoveries have employed active sources25,26 and fluidic mechanisms to realize non-Hermitian topological behaviors in thermal systems, including thermal topological insulators27,28,29, higher-order bound states30,31, and non-Hermitian skin effects32. Despite these advances, the introduction of nonlinear advection or dynamic flows typically requires active control and complex coupling architectures. This poses significant challenges for constructing stacked, in-plane 2D moiré lattices in thermal conduction, particularly when aiming for passive and scalable designs. This raises a fundamental question of whether moiré physics can be realized in a purely static, momentum-free, and linear thermal conduction system, without invoking advection or interacting nonlinearity? The answer is not obvious. The features of inherent diffusion, lack of intrinsic momentum space and coherent interference, and the linear Laplacian operators in thermal conduction shed dim light on interference-like phenomena and flat-band formation for interacting models (Fig. 1a, b). The absence of nonlinear coupling further complicates efforts to induce spatial localization effects through structural design alone. We are aware that some toy models, including Lieb, Kagome, and Dice lattices, could also support flat bands without moiré physics due to the intrinsic geometric interference or specific spatial symmetry. However, for the cases without geometric frustrations like an SSH model (Fig.1a, b), the introduction of nonlinearity could help further flatten the existing bands without requiring additional site configurations or special spatial symmetries (Fig.1a and b).

a, b present the schematic band structures of a typical linear and nonlinear 1D SSH models without geometric frustrations, possessing the same intracell and intercell hopping. Notably, the introduction of nonlinearity in (b) could artificially flatten the existing bands without additional implementations to create geometric-dependent flat bands with intrinsic geometric interference like Lieb, Kagome, and Dice lattices. c plots the alternating spatial-dependent thermal conductivities in a conductive monolayer to supplement the missing efforts caused by nonlinearity. The global four-site unit cell serves as the minimal model for repeating the conductivity distribution within a single layer, whereas the left-upper local region highlights a single site exhibiting a centrosymmetric distribution with respect to its local origin \({{{\rm{O}}}}^{{\prime} }\). \(r\) and \(\theta\) represent the spatial coordinates of an arbitrary point in the global reference frame of a single four-site unit cell. d denotes the new spatial characteristic and base wavevectors after stacking the two monolayers. Significant changes occur in conductivity distributions under the linear superposition of original conductive interactions. e showcases two types of effective wavenumbers at different twisted angles, including \(\left|{{{\bf{k}}}}_{{{\rm{moire}}}}\right|\) for presenting the global periodic function of the entire superlattice, and \(\left|{{{\bf{k}}}}_{{\mathrm{mod}}}\right|\) for modulating the interior profile of moiré pattern in each unit cell of the superlattice. The right-inset presents the effective wavenumbers \(\left|{{{\bf{k}}}}_{{{\rm{ref}}}}\right|\) without considering the differences of directional wavevectors after wave supersessions.

We address this gap by exploring the moiré-induced thermal localization in static and linear conduction systems. To compensate for the absence of intrinsic nonlinear coupling and geometric frustration in the lattice structure, we design spatially inhomogeneous thermal conductivities with radially tailored anisotropic profiles at prescribed lattice sites and periodically arrange them within a thin conductive plate. In this sense, the spatial gradient of conductivity serves as a generalized velocity field, enabling directional thermal energy propagation and mimicking momentum-like behavior in an otherwise diffusive medium. By vertically stacking two such plates with a prescribed twist angle, we generate a moiré superlattice at the interface without invoking any intrinsic material and flow nonlinearity. Through precise modulation of twist angles satisfying or violating Pythagorean relationships18,19,22,33, we realize both commensurate and incommensurate superlattices with distinct thermal field characteristics. Notably, we observe aperiodic thermal localization near symmetric twist configurations centered around π/4, attributed to mismatched modulated wavevectors within the moiré unit cell. Moreover, we identify a critical input energy threshold required to induce localization–delocalization transitions in incommensurate cases, where the threshold depends on the moiré lattice constant of the quasiperiodic structure defined by non-Pythagorean angles. These results demonstrate the feasibility of realizing moiré transitions and spatial thermal control through purely linear conduction mechanisms. Our findings introduce a paradigm in which moiré physics enables programmable control over dissipative transport in static and linear dissipative diffusion systems34,35,36.

Results

We begin with a four-site unit cell in a single conductive layer. Each site represents a finite volume for describing the heat exchanges with spatial-dependent thermal conductivity \(\kappa \left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\). Note that we consider a pure heat conduction process governed by the spatial-dependent heat diffusion equation, i.e., \(\nabla \cdot \left(\kappa \left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\nabla T\left({{\bf{r}}},t\right)\right)-\rho c\frac{\partial T\left({{\bf{r}}},t\right)}{\partial t}=0\), where \(T\left({{\bf{r}}},t\right)\) and \(\kappa \left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\) are respectively the temperature field and spatially modulated conductivity. This model is linear in the temperature field and satisfies superposition principles. The spatial inhomogeneity \(\kappa \left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\) modifies the coefficients of the diffusion operator but does not introduce nonlinear terms in \(T\left({{\bf{r}}},t\right)\). In stark contrast, nonlinear dissipative systems with momentum feature feedback mechanisms, such as reaction-diffusion models, nonlinear optics, and hydrodynamics, where the field dynamics depend nonlinearly on the field amplitude itself. The spatial variation in conductivity within a single site establishes a gradient that drives the evolution of the scalar temperature field across the unit (Fig. 1c). We then configure alternating spatial-dependent thermal conductivities \({\kappa }_{A}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\) and \({\kappa }_{B}\left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\) between neighboring sites in one unit (Fig. 1c). Taking the geometric center of the unit as origin, the conductivity distributions within each site can be described as

where \({{\bf{r}}}=\left(r\cos \theta,r\sin \theta,0\right)=\left(x,y,0\right)\), \(r\) and \(\theta\) denote the radial and azimuthal components within one four-site unit. \({\kappa }_{A}\) and \({\kappa }_{B}\) are respectively the conductivity amplitudes of each site. \({\kappa }_{0}=\frac{{\kappa }_{A}+{\kappa }_{B}}{2}\) denotes the conductivity of the symmetry center, while \(l\) is the side length of each site. \({n}_{{index}}=\lceil \frac{\theta }{\frac{\pi }{2}}\rceil\) indicates the quadrant of the considered point in the global coordinate system \({{\bf{r}}}\), and \(\delta=\frac{\sqrt{{\left(r-\frac{l}{\sqrt{2}}\right)}^{2}+\sqrt{2}{rl}-\sqrt{2}{rl}\cos \left(\theta -\left(2{n}_{{index}}-1\right)\frac{\pi }{4}\right)}}{\frac{l}{\sqrt{2}}}\) (Supplementary Note 1). By periodically arranging the four-site unit cell along both the x and y directions, we construct a two-dimensional conductive monolayer characterized by a spatially modulated conductivity distribution of \(\kappa \left({{\bf{r}}}\right){e}^{i\left({k}_{x}+{k}_{y}\right)}\). Here, wavevector \({{\bf{k}}}=\left({k}_{x},{k}_{y},{k}_{z}\right)\), and \({k}_{x}=\frac{2\pi }{{l}_{s}}\), \({k}_{y}=\frac{2\pi }{{l}_{s}}\), \({k}_{z}=0\) respectively denote the effective wavenumbers. \({l}_{s}\) is the characteristic length (effective wavelength) in the monolayer, chosen to generate the desired moiré superlattice under a specified twist angle (Supplementary Note 2). To introduce a moiré modulation, we stack a second monolayer atop the first, rotated by a twist angle \(\varphi\) (Supplementary Fig. 1d). The local coordinate in the second monolayer becomes \({{{\bf{r}}}}^{{{{\prime} }}}=\left(r\cos \theta,r\sin \theta,0\right)R\left(\varphi \right)\), \(R\left(\varphi \right)=\left(\begin{array}{ccc}\cos \varphi & -\sin \varphi & 0\\ \sin \varphi & \cos \varphi & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 1\end{array}\right)\). Accordingly, the rotated wavevector is \({{{\bf{k}}}}^{{{{\prime} }}}=\left({k}_{x},{k}_{y},{k}_{z}\right)R\left(\varphi \right)=\left({k}_{x}\cos \varphi -{k}_{y}\sin \varphi,{k}_{x}\sin \varphi+{k}_{y}\cos \varphi,{k}_{z}\right)\) and the conductivity distribution can be written as

Further stacking the two conductive monolayers, a moiré conductivity distribution occurs at the interface, whose in-plane energy exchanges under a wave-like temperature \(T\left({{\bf{r}}},t\right)=\psi \left({{\bf{r}}}\right)U\left(t\right)\) at steady state (Supplementary Note 2) can be expressed as

In that case, a new spatial period occurs in the conductivity distribution at the interface (Fig. 1d), i.e., \(\kappa \left({{\bf{r}}}\right)+\kappa \left({{{\bf{r}}}}^{{{{\prime} }}}\right)\to \kappa \left({{\bf{r}}}\right)\left({e}^{i\left({k}_{x}+{k}_{y}\right)}+{e}^{i\left({k}_{x}^{{\prime} }+{k}_{y}^{{\prime} }\right)}\right)\), thus further leading to an interference of two plane-wave components. This interference leads to the formation of a moiré modulation expressed as \(2{e}^{i\frac{{{\bf{k}}}+{{{\bf{k}}}}^{\prime}}{2} \cdot {{{\bf{r}}}}_{{{\rm{moire}}}}}\cos \left(\frac{{{\bf{k}}}-{{{\bf{k}}}}^{\prime}}{2}{{{\bf{r}}}}_{{{\rm{moire}}}}\right)\), and \({{{\bf{r}}}}_{{{\rm{moire}}}}\) represents the coordinate of the emerging moiré pattern. The base vectors of the moiré superlattice exhibit a deflection angle \(\beta=\arccos \left(\frac{{{{\bf{k}}}}_{{moire}}\cdot {{\bf{k}}}}{\left|{{{\bf{k}}}}_{{moire}}\right|\left|{{\bf{k}}}\right|}\right)=\frac{\varphi }{2}\), which characterizes the orientation of the moiré pattern relative to the original x-y axes. Notably, when the four-site unit cell does not form a perfect square lattice, the deflection \(\beta\) varies, and in the limit where one directional wavenumber approaches zero, \(\beta\) can approach the full twist angle \(\varphi\) (Supplementary Note 3). The global periodic function behaves as a single plane wave with an effective wavevector \({{{\bf{k}}}}_{{{\rm{moire}}}}=\frac{{{\bf{k}}}{{+}}{{{\bf{k}}}}^{{{{\prime} }}}}{2}\), while the interior profile of the moiré pattern is modulated by the difference of the superposed two wavevectors \({{{\bf{k}}}}_{{\mathrm{mod}}}=\frac{{{\bf{k}}}-{{{\bf{k}}}}^{{{{\prime} }}}}{2}\). Considering the dramatic changes in the lattice constants under specific twist angle \(\varphi\), the two wavenumbers indicate irregular evolutions with the increasing \(\varphi\) (Fig. 1e). Strikingly, peaks in these effective wavenumbers appear at specific angles that satisfy Pythagorean triples, giving rise to more available propagation channels. In contrast, near-zero effective wavenumbers emerge for most twist angles violating Pythagorean triples, and lead to the suppression of propagating modes and the formation of localized temperature fields. These wavevector observations stem from the general principles of moiré patterns. That is, Pythagorean triples yield periodic moiré primitive cells with translational symmetry, whereas non-Pythagorean angles lead to aperiodic structures that break translational symmetry, thereby reducing the wavenumbers of the allowed propagating modes.

We then establish three theoretical examples, respectively, at two Pythagorean angles (36.87° and 22.62°) and one non-Pythagorean angle (30°). The thermal conductivities of neighboring sites within a single layer are assigned as \({\kappa }_{A}=10{\kappa }_{{ref}}\) and \({\kappa }_{B}=0.1{\kappa }_{{ref}}\), and \({\kappa }_{{ref}}=1\) W⋅m−1⋅K−1 serves as the reference thermal conductivity. Theoretical calculations of the corresponding conductive properties at these three twist angles are presented in Fig. 2. At the Pythagorean angles (36.87° and 22.62°), the commensurate nature of the twist induces periodic distributions of conductivity. These periodic patterns support the formation of a generalized moiré superlattice for thermal conduction, since they provide a periodic potential defined by the gradient of conductivity for modulating heat flux through the system. In this scenario, a primitive cell occurs (Fig. 2a, b), serving as the repeating unit that captures the spatial characteristics of the moiré superlattice at the interface.

a, b present the conductivity distributions of the periodic moiré patterns respectively at the Pythagorean angles of 36.87° and 22.62°. The red dashed box presents a primitive cell in the moiré patterns. Their right-insets indicate the typical conductive fields of the unit cell, including (i) the heat flux and temperature field, (ii) the conductivity distribution, and (iii) the conductive vorticity. c showcases the conductivity distributions of the aperiodic moiré patterns at the non-Pythagorean angle of 30°. The blue dashed box presents a primitive cell in the moiré patterns approximated by the periodic lattice at the nearest Pythagorean angle of 30.14°. d The typical conductive fields of the unit cell at 30° same to the counterparts in (a, b, e) The anisotropic degree at different twisted angles. f presents the Fourier number under the changing twisted angles (\(\varphi\)) and the strength ratios of conductivity between neighboring sites (\({p}_{c}\)). The black dashed lines denote some representative Pythagorean angles.

The linear superposition of the two mismatched conductive layers results in strong inhomogeneity of thermal conductivity within the emerging moiré unit cell (Fig. 2a(ii), b(ii)). These conductivity distributions generate potential fields for thermal transport between regions of highest and lowest local conductivity, giving rise to clockwise or counterclockwise heat flux directions with inhomogeneous temperature fields (Fig. 2a(i), b(i)). In these cases, thermal energy dissipates rapidly within the unit cell, leading to near-zero temperature gradients. Notably, the centers of the rotated heat flux patterns correspond to conductive vortices with the charges of +1 and –1 in Fig. 2a(iii), b(iii). In contrast, when the twist angle is set to the non-Pythagorean value of 30°, an aperiodic conductivity distribution arises due to mismatched amplitudes and spatial features. This satisfies a critical condition for forming a moiré quasicrystal, namely, the absence of overlapping lattice points or centers between the two stacking layers at the interface (Fig. 2c). Given the visual similarity of the moiré pattern to that at the nearby Pythagorean angle (30.14°), we approximate the geometry of its primitive cell to explore the conductive behavior at 30° (Fig. 2d(ii)). In stark contrast to the periodic moiré superlattices at 36.87° and 22.62° (Fig. 2a, b), the structure at 30° exhibits a significantly larger effective lattice constant, which amplifies the degree of anisotropy (Fig. 2e) (Supplementary Note 3) and introduces greater randomness, manifested in more complex heat flux rotations and additional conductive vortices as illustrated in Fig. 2d(i), d(iii). These effects further enhance the fluctuations of conductive energy exchanges in contrast to those at Pythagorean angles.

To further explore the diffusive process under specific twist angles, we adopt a single conductive layer with homogeneous conductivity at each site as a reference model for nondimensional analysis (Supplementary Note 4), i.e., \({\kappa }_{{ref}}={\kappa }_{0}=\frac{\left|{\kappa }_{A}+{\kappa }_{B}\right|}{2}\). We use the Fourier number \(\left\langle {{\rm{Fo}}}\right\rangle=\frac{\left\langle {{{\bf{D}}}}^{{{*}}}\right\rangle {t}^{*}}{{r}^{*}}\) to quantify the ratio between the rates of heat transfer and thermal energy storage in a finite conductive system (Fig. 2f), where \(\left\langle {{{\bf{D}}}}^{{{*}}}\right\rangle\) represents the average thermal diffusivity, \({r}^{*}\) is the characteristic lattice constant of the system. Note that, \({t}^{*}\) is the normalized heat transfer time, and a large value of \({t}^{*}=10000\,{{\rm{s}}}\)) is selected to ensure a steady-state thermal profile. Significantly lower Fourier numbers are observed at non-Pythagorean angles, indicating a relatively greater contribution of thermal energy storage and a suppressed heat transfer process compared to those at Pythagorean angles. Furthermore, \(\left\langle {{\rm{Fo}}}\right\rangle\) decreases with increasing conductivity ratio \({p}_{c}=\frac{{\kappa }_{A}}{{\kappa }_{B}}\) at a fixed twist angle. This trend arises governed by a more homogeneous conductivity distribution (\({p}_{c}\to 1\)) that reduces the contrast between\(\,{\kappa }_{A}\) and \({\kappa }_{B}\), leading to weaker potential fields for driving heat flux at the interface.

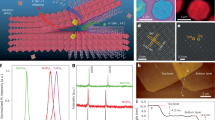

We further adopt a bilayer conductive system (Fig. 3a) to visualize these moiré patterns in temperature fields. The entire system is fabricated with epoxy, which has a thermal conductivity of \({\kappa }_{p}=1\) W⋅m–1⋅K–1, while the desired conductivities are enabled by alternating epoxy fins (Fig. 3b, c) of varying heights (Methods). For representation, we make \({\kappa }_{A}=10\) W⋅m-1⋅K-1 and \({\kappa }_{B}\to 0\) at each site center, while the conductivity of the symmetry center \({\kappa }_{0}=\frac{\left|{\kappa }_{A}+{\kappa }_{B}\right|}{2}\) is 5 W⋅m–1⋅K–1 for each unit cell. All three cases exhibit non-uniform temperature distributions (Fig. 3d–f) at the interface. Due to the commensurability at Pythagorean angles (36.87° and 22.62°), the corresponding temperature fields (Fig. 3d, e) display clear periodicity along their translational vectors. At 22.62°, the larger moiré lattice constant results in a greater number of overlapping site points within a single unit cell, producing more pronounced hot and cold spots. Such behavior implies more charges in the conductivity distributions of the corresponding moiré primitive cell at the Pythagorean angle with larger lattice constants. These features confirm the theoretical prediction of weakened in-plane heat transfer in Fig. 2b, e. In contrast, the temperature profiles at the non-Pythagorean angle (30°) exhibit aperiodic distributions without translational symmetry, thus revealing a quasicrystal at the interface enabled by the nature of moiré geometry. Far more hot/cold spots than the ones at Pythagorean angles occur in the finite area induced by the incremental defect quantities with non-zero charges of the effective moiré primitive cell. These temperature profiles (Fig. 3d–f) align well with the theoretical conductivity distributions shown in Fig. 2. Besides, the linear relation between the lattice constant (L) and an effective \(\left\langle {{\rm{Pe}}}\right\rangle\) (Pelect number) related to the angular frequency (a) for a wave-like thermal system, i.e., \(\frac{L}{\left\langle {Pe}\right\rangle }=\frac{D}{{\partial }_{l}D}\to l\) (Supplementary Note 4), further implies a conserved connection in each system with respect to a fixed lattice constant. This observation provides a foundation for implementing effective band analysis to describe thermal decay behaviors in moiré lattices.

a–c plot the experimental sample and setups for observing the conductive moiré superlattice. Among them, a exhibits the strategy for generating conductive moiré superlattices (purple boundary-area) at the interface by merging the two conductive monolayers. The light-yellow and the light-blue shadow areas respectively mark the top and bottom monolayers. Heat flux is imposed from the top of the entire sample. b demonstrates the two monolayers shown in (a), and the enlarged inset showcases the fin structure. c is a cross-section of the entire system in the y-z plane for generating the conductivity distributions. d–f denote experimental temperature profiles respectively at the twisted angles of 36.87°, 22. 15°, and 30° under a constant heat flux imposed on the entire sample, while the right insets present the locally characteristic profiles within each superlattice. g indicates the linear relationship between lattice constant and effective \(\left\langle {{\rm{Pe}}}\right\rangle\). The error bars denote the standard deviations among measurements.

We adopt a conventional approach by applying a heat source along the z-direction to excite moiré properties at the interface of the superlattice. In this configuration, the temperature field is modeled as a wave-like profile along the z-direction \(T\left(x,y,z,t\right)=\psi \left(x,y,z\right)\cdot U\left(t\right)=m\left(x,y,z\right){e}^{i{k}_{z}}\cdot U\left(t\right)\). Here, \(\psi \left(x,y,z\right)\) denotes the spatial component of temperature propagation, whose in-plane extension and out-of-plane motivation are respectively \(m\left(x,y,z\right)\) and \({e}^{i{k}_{z}z}\). Since thermal decay occurs and diffuses within the conductive medium, we make the total thickness of the stacked bilayer structure (2hp) along the z-direction the characteristic length for the incident wave-like temperature profile. The characteristic wavelength and wavenumber corresponding to the geometry can be defined as \({\lambda }_{z}=2{h}_{p}\) and \({k}_{z,0}=\frac{2\pi }{{\lambda }_{z}}\). In this case, an effective wave velocity for the temperature field propagation can be determined with \({v}_{z,{tem}}=\frac{{\lambda }_{z}}{{t}_{z}}\) as the reference to quantization as illustrated in Fig. 3g. For simplification, the unit period \({t}_{z}=1\) s is adopted in this process. To express the excited frequency passing through the moiré superlattice, we introduce a scaling factor \(n > 0\), such that \({k}_{z,0}=n{k}_{z}\). Due to the far larger heat transfer in-plane distance than that of out-of-plane effective wavelength λz, the in-plane extension \(m\left(x,y,z\right)\) satisfies slowly varying function, i.e.,\(\left|\frac{{\partial }^{2}m}{{\partial z}^{2}}\right|\ll \left|{k}_{z}\frac{\partial m}{\partial z}\right|\), and we can rewrite the thermal energy exchange at the stacking interface for one primitive cell of the superlattice as (Supplementary Note 4)

where, \(a\) and \({a}_{r}\) represent the effective angular frequencies associated with periodic heat transport and dissipative decay in the fixed and rotated conductive layers. By substituting the incident temperature wave into Eq. (4), the in-plane extension \(\psi\) can be solved through an eigenvalue problem \({H}_{{{\rm{moire}}} ^{\prime}}\psi={E}_{{{\rm{moire}}}^{\prime}}\psi\), where \({H}_{{{\rm{moire}}}^{\prime}}\) denotes the effective Hamiltonian of the emerging superlattice, and \({E}_{{{\rm{moire}}}^{\prime}}=a+{a}_{r}\) is the corresponding eigenvalue based on the linear relationship between lattice constant and effective \(\left\langle {Pe}\right\rangle\). These eigenvalues define the effective band structure, which characterizes the coupling between thermal dissipation and the incident wave frequency at the interface.

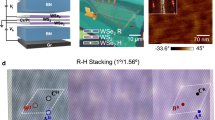

The first Brillouin zones corresponding to the three twist angles are shown in Fig. 4a–c. At the two Pythagorean angles, prominent non-flat bands are observed, indicating a strong correlation between the temperature field distribution and the effective angular frequency in the commensurate moiré superlattice. These band structures signify permitted heat flux propagation and delocalization across the interface. Specifically, these degeneracies provide multiple propagation channels for temperature transport under translational symmetry. The presence of several degenerate modes allows energy to distribute across parallel pathways, thereby reinforcing the extended character of the temperature field. Moreover, the overlaps between non-flat bands ensure that the effective group velocity remains finite over a broad range of thermal modes. This redundancy suppresses the possibility of confinement into localized hot spots and instead results in robust delocalization. In contrast, when the twist angle is set to the non-Pythagorean value of 30°, ultra-flat bands emerge, indicating a near-zero group velocity for temperature wave transport. This suggests that the absence of translational symmetry in the incommensurate moiré superlattice induces strong localization of the temperature field. We then experimentally observe these localized and delocalized states under an incident temperature wave. Due to the dissipative diffusion of intrinsic conduction, we adopt a thermal pulsing point source with a representative frequency of \({f}_{{inc}}=\frac{{v}_{z,{tem}\,}}{{\lambda }_{z,{inc}}}=150\) Hz and measure the temperature profiles at steady state after \(t=1800\,{{\rm{s}}}\) for evaluating the energy distributions at the interface (Methods). Both two cases at Pythagorean angles exhibit rapid temperature field extensions at the interface (Fig. 4d, e), revealing the substantial sufficient delocalization with unobstructed transport. On the contrary, the temperature field becomes highly localized with prominent hot spots around the point source at the non-Pythagorean angle (30°). These behaviors agree well with the effective band structures (Fig. 4a–c), thus revealing the transitions between delocalized and localized thermal conduction as the twist angle is modulated. We then calculate the localized degree with the integral form factor \(\chi=\sqrt{\frac{\iint {\left|\psi \right|}^{4}{dxdy}}{{\left(\iint {\left|\psi \right|}^{2}{dxdy}\right)}^{2}}}\). The numerator represents the concentration of thermal energy, while the denominator reflects the spatial extent of the mode across the interface. The value of \(\chi\) is inversely proportional to the mode extension degree at the interface. That is, the smaller \(\chi\) reveals the stronger delocalization of the temperature field propagations.

a–c present the effective band structures of the first Brillouin zones, respectively, at the twisted angles of 36.87°, 22.62°, and 30°. The line colors indicate the effective bands at different frequencies. Significant degeneracies occur with non-flat bands in the commensurable superlattice at 36.87°and 22.62°, while flat bands appear in the incommensurable superlattice at 30°. d–f exhibit thermal profiles under the incident temperature wave through a pulsing point source (150 Hz), whose positions are indicated by orange stars. Rapid delocalization and localization of the temperature fields are respectively observed in the commensurable and incommensurable superlattices. g plots the phase diagram of the localized degrees (integral form factor) of the passing-through temperature wave under twisted angles and the ratio of conductivity (\({p}_{c}\)). The white-dashed lines indicate some representative Pythagorean angles. h, i present the threshold frequencies for motivating the transitions between thermal delocalization and localization at a specific non-Pythagorean angle. The error bars denote the standard deviations among measurements. Notably, such a threshold also exists in commensurable superlattices at Pythagorean angles. However, only field delocalization is significant due to the quite small integral form factor.

The calculated integral form factors at these three twisted angles are shown in Fig. 4g. Near-zero \(\chi\) appear at the two Pythagorean angles and a finite value is exhibited at non-Pythagorean angle, consistent with the trend of the Fourier numbers shown (Fig. 2e). In addition to the twisted angles, the energy of the incident thermal wave also plays a critical role in driving the transition between field localization and delocalization. Following Eq. (4), a critical frequency for stimulating the moiré transition occurs when the incident thermal wave from the z-direction matches the in-plane extensive energy with the tailored system parameters. This corresponds to a critical wavenumber condition \({\left({k}_{z,0}\right)}^{2}={k}^{2}+{\left({k}^{{\prime} }\right)}^{2}\to {\left(\frac{4\pi }{{l}_{s}}\right)}^{2}\) (Supplementary Note 5), where the critical wavenumber \({k}_{z,0}\) varies with the twist angle and the associated moiré lattice constant. The localization–delocalization behavior can be modulated by adjusting the incident wavenumber \({k}_{z}\) (frequency). When \({k}_{z} > {k}_{z,0}\), field localization is significantly enhanced due to stronger moiré confinement. In contrast, field delocalization (extension) is significant when \({k}_{z} < {k}_{z,0}\), as the energy input is insufficient to motivate the moiré behaviors. We then plot the integral form factor \(\chi\) with the input frequency based on the incident wavenumber \({k}_{z}\). For the cases at the two Pythagorean angles, the increasing input frequency leads to the increasing \(\chi\) (Fig. 4h). However, the values of \(\chi\) always maintain near-zero regardless of the input frequency, thus only resulting in the extensive temperature field delocalization induced by the non-flat bands (Fig. 4a, b) and commensurability of the superlattice. When changing input frequency at the non-Pythagorean angle, an apparent turning point occurs at 30°. Significant delocalization and localization transition in the temperature field are observed when the input frequencies change from zero to infinite, centered by the critical frequency corresponding to \({k}_{z,0}\) (Supplementary Fig. S2). The critical frequency threshold is intimately tied to the lattice constant of the moiré superlattice. Specifically, configurations with larger moiré lattice constants require a higher incident frequency to activate the phase transition in the temperature field. In this case, the system effectively perceives an averaged homogeneous medium without localized behaviors at a non-Pythagorean angle, once the corresponding wavelength of the imposed temperature wave with low incident frequency is much larger than the moiré lattice constant (the insert of Fig. 4i). In this regime, the excitation primarily couples into extended diffusive modes, and delocalization dominates. Once the excitation frequency exceeds the threshold set by the moiré lattice constant, resonant coupling into flat-band modes occurs, and their vanishing group velocity manifests physically as strong localization (as shown in Fig. 4f). Thus, localization in incommensurate moiré lattices requires both the existence of flat bands and sufficient excitation to activate them. This observation highlights the geometric dependence of moiré thermal transport and emphasizes the role of angular commensurability in governing energy confinement and transport modes within twisted bilayer conductive systems. Note that the frequency response in Fig. 4h exhibits an apparent threshold. This threshold does not correspond to a localization-delocalization transition, but rather to the characteristic frequency associated with the moiré lattice constant (see Supplementary Note 5). Below this frequency, the excitation predominantly couples into lower-order extended modes, resulting in the mode extension with weak temperature field intensity. Once the incident frequency approaches the characteristic scale of the superlattice, higher-order delocalized modes are activated, producing a monotonic increase in the integral form factor with strong intensity. The observed threshold in Fig. 4h should therefore be understood as a crossover point for enhanced delocalization efficiency, i.e., a measure of how strongly the external excitation couples into the extended modes of the commensurate superlattice, rather than as a localization-delocalization boundary (which is only present in the incommensurate case, Fig. 4i).

Discussion

We report diffusive moiré superlattices and reveal the moiré flat bands for temperature field transition between localization and delocalization in purely dissipative conduction. Alternating conductivities enable in-plane spatial periodicity in a pure conductive system and generate the potential field for creating moiré flat bands via a bilayer configuration. By modulating the twisted angles, the experimental visualizations exhibit notable moiré patterns through inhomogeneous temperature distributions, resulting from the newly emerging periodicity at corresponding twisted angles. Such moiré patterns offer the opportunity to reveal exotic transport phenomena in general diffusion by modulating the symmetry, coupling strength, and external energy inputs, such as flocking effects, analog ferromagnetism. A general strategy for controlling diffusive conduction within the interfacial superlattice via modulating the twist angles and excited energy of the incident temperature wave, whose critical energy input for inducing the localization-to-delocalization transitions depends on the lattice constant at corresponding non-Pythagorean angles. It is worth noting that the conductivity ratio between neighboring sites in a single layer could also affect the moiré behaviors, like the ones of modulating vortex strength ratio in hydrodynamic moiré superlattice24, indicating the weakened localization with increased ratio. The concept can also extend to other diffusive territories, which pave the avenge of quantity manipulations in microfluids, chemical, and biological disciplines.

Methods

Experimental samples of each site and their effective conductivities

To implement the desired conductivity configuration at each site within a unit cell, we begin with a thin square epoxy plate of thickness of hp = 1 mm and a side length of \({l}_{p}=\frac{l}{2}=5\) mm. The top surface of this plate serves as the coupling platform for heat exchange at the interface of the bilayer structure. On the bottom side, we configure alternating epoxy fins of varying heights (hf) to create the effective conductivity distribution (Fig. 3b, c). Upon energy conservation between each site and its corresponding fin under identical heat sources, we have \({Q}_{i}=\int {\kappa }_{i}{\nabla }^{2}{Td}{V}_{i}=\int {\kappa }_{p}{\nabla }^{2}{Td}{V}_{{fin},i}={Q}_{{fin},i}\) and \(i={A}\,{{\rm{or}}}\,{B}\) representing the target site. Then, the conductivity along the radial direction in each site can be effectively determined by \({\kappa }_{i,r}={\kappa }_{p}\frac{{Q}_{{fin},i}}{{Q}_{i}}\). Given the uniform heat exchange area between each site and its associated fin, the fin height directly dominates the local conductivity, leading to the simplified relation of \({\kappa }_{i,r}\to {\kappa }_{p}\frac{{h}_{f,i}}{{h}_{p}}\). In this case, the heat exchange area between the plate and the fin (from the base to height \({h}_{f}\)), follows a proportional relation to the area of the thin plate, i.e., \(\frac{{S}_{A,h}}{{S}_{p}}=\frac{{l}_{A,h}^{2}}{{l}_{p}^{2}}\), where \({S}_{A,h}\) and \({l}_{p,h}\) respectively denote the heat exchange area and side length of the fin at tailored height of site A. To represent this configuration, we employ a tapered fin structure for site A to realize a smooth conductive gradient across the plate (Fig. 3c). In contrast, for site B with near-zero conductivity, anisotropic effects are negligible. Therefore, we leave the corresponding area of the thin plate in direct contact with air, maintaining a thermal conductivity of \({\kappa }_{B}=0.0025\) W⋅m–1⋅K–1 without additional structures vertical structures (\({h}_{f,{B}}=0\)). By periodically arranging and vertically stacking these two conductive layers with specific twist angles, we construct a platform to experimentally demonstrate the emergence of moiré patterns at the bilayer interface. The linear superposition of their conductivity distributions produces an inhomogeneous moiré potential, with the highest and lowest temperature amplitudes confined to regions where the conductivity gradient approaches zero.

Heating strategy in experiments

In the demonstrations of moiré patterns presented in Fig. 3, a constant heat flux is applied perpendicular to the interface of the entire sample. Specifically, a heat source at 373 K is applied to the bottom surface, while a cooling source at 273 K is imposed on the top surface of the bilayer system. The resulting temperature profiles shown in Fig. 3 are recorded at the interface after 30 min of heating and cooling. To investigate the localized modes illustrated in Fig. 4d–f, we employ a thermal pulsing point source that generates a temperature wave described by \(T\left(z,t\right)=353+80{{{\rm{e}}}}^{i\left(\frac{2\pi z}{{\lambda }_{z,{inc}}}+\frac{2\pi }{{t}_{z,{inc}}}t\right)}\), where the excitation frequency is given by \({f}_{{inc}}=\frac{{v}_{z,{tem}\,}}{{\lambda }_{z,{inc}}}=150\) Hz. Such a point source replaces the global heating strategy in Fig. 3. The heating duration is again set to 30 min. Localized and delocalized thermal modes can be clearly identified based on the spatial extent of a designated isothermal contour line at the interface.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Andrei, E. Y. et al. The marvels of moiré materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 201–206 (2021).

Balents, L., Dean, C. R., Efetov, D. K. & Young, A. F. Superconductivity and strong correlations in moiré flat bands. Nat. Phys. 16, 725–733 (2020).

Tan, Q. et al. Layer-dependent correlated phases in WSe2/MoS2 moiré superlattice. Nat. Mater. 22, 605–611 (2023).

Xion, R. et al. Correlated insulator of excitons in WSe2/WS2 moiré superlattices. Science 380, 860–864 (2023).

Chen, G. et al. Tunable correlated Chern insulator and ferromagnetism in a moiré superlattice. Nature 579, 56–61 (2020).

Liu, B. et al. Higher-order band topology in twisted moiré superlattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 066401 (2021).

Sinha, S. et al. Berry curvature dipole senses topological transition in a moiré superlattice. Nat. Phys. 18, 765–770 (2022).

Li, T. et al. Continuous Mott Transition in Semiconductor Moiré Superlattices. Nature 597, 350–354 (2021).

Du, L. et al. Nonlinear physics of moiré superlattices. Nat. Mater. 23, 1179–1192 (2024).

Sheng, D.N., Reddy, A. P., Abouelkomsan, A., Bergholtz, E. J. & Fu, L. Quantum anomalous Hall crystal at fractional filling of moiré superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 066601 (2024).

Cao, Y. et al. Tunable correlated states and spin-polarized phases in twisted bilayer–bilayer graphene. Nature 583, 215–220 (2020).

Hu, G. et al. Topological polaritons and photonic magic angles in twisted α-MoO3 bilayers. Nature 582, 209–213 (2020).

Carr, S. et al. Twistronics: manipulating the electronic properties of two-dimensional layered structures through their twist angle. Phys. Rev. B 95, 075420 (2017).

Woods, C. R. et al. Commensurate–incommensurate transition in graphene on hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Phys. 10, 451–456 (2014).

Wang, P. et al. Localization and delocalization of light in photonic moire lattices. Nature 577, 42 (2020).

Huang, D., Choi, J., Shih, C.-K. & Li, X. Excitons in semiconductor moiré superlattices. Nat. Nanotech. 17, 227–238 (2022).

Luo, Y. et al. In situ nanoscale imaging of moiré superlattices in twisted van der Waals heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 11, 4209 (2020).

Fu, Q. et al. Optical soliton formation controlled by angle twisting in photonic moiré lattices. Nat. Photonics 14, 663–668 (2020).

Törmä, P., Peotta, S. & Bernevig, B. A. Superconductivity, superfluidity and quantum geometry in twisted multilayer systems. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 528–542 (2022).

Fujimoto, M., Kawakami, T. & Koshino, M. Perfect one-dimensional interface states in a twisted stack of three-dimensional topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 043209 (2022).

Huang, C. et al. Localization-delocalization wavepacket transition in Pythagorean aperiodic potential. Sci. Rep. 6, 32546 (2016).

Wang, P., Fu, Q., Konotop, V. V., Kartashov, Y. V. & Ye, F. Observation of localization of light in linear photonic quasicrystals with diverse rotational symmetries. Nat. Photonics 18, 224–229 (2024).

Han, C. et al. Observation of dispersive acoustic quasicrystals. Nat. Commun 16, 1988 (2025).

Xu, G. et al. Hydrodynamic Moiré Superlattice. Science 386, 1377–1383 (2024).

Yang, F. et al. Controlling mass and energy diffusion with metamaterials. Rev. Mod. Phys. 96, 015002 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Sustainable heat harvesting via thermal nonlinearity. Nat. Rev. Phys. 6, 769–783 (2024).

Xu, G. et al. Diffusive topological transport in spatiotemporal thermal lattices. Nat. Phys. 18, 450–456 (2022).

Xu, G., Zhou, X., Yang, S., Wu, J. & Qiu, C.-W. Observation of bulk quadrupole in topological heat transport. Nat. Commun 14, 3252 (2023).

Gao, H. et al. Topological Anderson phases in heat transport. Rep. Prog. Phys. 87, 090501 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Higher-order topological in-bulk corner state in pure diffusion systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 176302 (2024).

Yang, S. et al. Hierarchical bound states in heat transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2412031121 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Localized and delocalized topological modes of heat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2408843121 (2024).

Arkhipova, A. A. et al. Observation of linear and nonlinear light localization at the edges of moiré arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 083801 (2023).

Xu, G. et al. Tunable analog thermal material. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–9 (2020).

Dunkel, J. et al. Fluid dynamics of bacterial turbulence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 228102 (2013).

Tan, T. H. et al. Topological turbulence in the membrane of a living cell. Nat. Phys. 19, 657–662 (2020).

Acknowledgements

G.X. acknowledged the support of the Big Data Computing Center of Southeast University in calculation and the Center for Fundamental and Interdisciplinary Sciences of Southeast University in measurement. X.Z. acknowledged the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12305041), and the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. KJZD-K202300803). C.-W.Q. acknowledged the support by the Ministry of Education, Republic of Singapore (grant No.: A-8002978-00-00), and National Research Foundation, Singapore (NRF) under NRF’s Medium-Sized Centre: Singapore Hybrid-Integrated Next-Generation μ-Electronics (SHINE). G. H. acknowledged the Nanyang Assistant Professorship Start-up Grant, Ministry of Education (Singapore) under AcRF TIER2 (T2EP50224-0044), and A*STAR under its MTC IRG Grant (Project No. M24N7c0081).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.X. and C.-W.Q. conceived the idea. G.X., S.Y., and X.Z. contributed equally to this work. G.X., S.Y., and X.Z. proposed the methodology. G.X., S.Y., X.Z., H.J., G.H., and C.-W.Q. performed the theoretical analysis. G.X., X.Z., H.J., and J.W. fabricated the samples. G.X., S.Y., and X.Z. implemented the experiments. G.X., S.Y., X.Z., and J.W. made the visualizations. G.X., S.Y., X.Z., and C.-W.Q. wrote the manuscript. X.Z., and C.-W.Q. supervised the work. All authors contributed to the discussion and finalization of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, G., Yang, S., Zhou, X. et al. Localized dissipation in linear moiré heat transport. Nat Commun 17, 722 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67483-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67483-0