Abstract

Battery monitoring requires high accuracy and robustness throughout the entire lifespan to ensure safe and optimal operations. Here we introduce mechanistic leading residual learners to enhance the monitoring of battery charge and health states, as well as guide safety warnings, targeting large-scale applications. Leveraging prior knowledge from real-time filtering as primary guidance, complemented by mechanistic and statistical features, our approach significantly improves accuracy and robustness. We propose and validate two general residual learning pipelines, namely the correction model and compensation model, across various scenarios, encompassing different battery types, loading profiles, aging conditions, and environmental conditions, using three aging datasets under dynamic cycling. Our method achieves a relative root mean square error reduction of over 50% from the results observed in prior estimations. The extrapolation capability under unseen conditions, along with interpretability, enhances both accuracy and trustworthiness. The models remain effective even with reduced training data and sampling frequency, maintaining the potential for practical electric vehicle applications. Application demonstrations confirm the efficacy in providing continuous monitoring across lifespan without the need for offline testing and model calibration during operation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries are extensively utilized to support sustainable development, yet they present significant challenges in accurate state monitoring due to their diverse chemistry and types, usage conditions, and the complex aging processes encountered in electrified transportation1,2,3,4. To ensure safe operations and guide optimal management, state of charge (SOC) and state of health (SOH) are two of the most concerned indices to indicate the battery potential in real-time and in a long-time horizon5,6,7. Developing a closed-loop framework for battery monitoring is crucial for enhancing battery management and avoiding safety hazards, particularly as batteries degrade8,9,10. Traditionally, specific tests are conducted to verify the estimations of SOC and SOH independently or under several sparse conditions. However, real-world applications demand effective battery state monitoring that accounts for continuous aging under dynamic loads and varying temperatures.

Widely adopted methods for battery state monitoring include model-based and data-driven approaches, each offering distinct advantages but also having certain limitations. Model-based methods are known for their robustness, particularly when incorporating high-fidelity battery models, though they tend to be more complex. Model-based methods are usually constructed with filtering methods such as the Kalman filter for internal state estimation. In contrast, data-driven methods, which map the relationships between the features and battery states via machine learning (ML) models, offer greater flexibility but often suffer from limited generalization capabilities11. Consequently, hybrid monitoring structures that combine model-based filtering approaches with ML have gained popularity, aiming to enhance both accuracy and robustness12,13,14,15. One straightforward method involves fusing the outputs of different sub-models, e.g., filtering-based estimation and ML estimation, to mitigate uncertainties associated with any single model11,16,17. Due to the large variances of the estimation from data-driven approaches, especially for SOC estimation, one popular approach employs filtering techniques afterwards to enhance the estimation from ML models16,18,19,20. However, the implementation in SOC estimation usually adopts the real reference, i.e., coulomb counting, as the observation, which makes it hard to obtain accurate calculations in real applications. On the other hand, ML excels at modeling uncertain relationships, and the estimated errors from model-based methods vary and are hard to describe21,22. Therefore, the sequential framework of the model-based method followed by ML was proposed, where ML is employed after the filtering method to improve the initial estimation from model-based methods23,24,25. The main idea is that ML models the uncertainties and the errors of the mechanistic model-based methods, which have been employed for both hybrid battery modeling and temperature estimation. Nevertheless, the specific pipeline is designed for a specific purpose and has only been verified under several specific tests, limiting its practical large-scale application. Systematic design for general hybrid pipelines integrating model-based filtering and ML methods with applications using dynamic cycling for the entire lifespan is a practical yet unsolved challenge. Additionally, physics-informed neural network models have shown the potential to enhance physical interpretability and reduce data requirements in battery modeling26,27. However, the sensitivity of these models to the tolerance of physical laws can greatly impact their predictive accuracy. Conversely, when reliable prior knowledge is incorporated, data-driven models demonstrate more stable improvements in predictive performance.

Feature extraction is one key factor that hugely influences the accuracy of ML models28,29,30,31,32. Methods for statistical calculation can extract highly effective features28,29. However, these features are often sensitive to varying operating conditions, such as different current rates and temperatures, which can reduce model performance across diverse scenarios. While domain adaptation techniques can reduce the discrepancies between the feature distributions, thus enhancing the generalization of monitoring models under different conditions, they also increase model complexity and computational demands, hindering the application for real-time state estimation33,34. Therefore, improving the suitability and coherence of features across different conditions is crucial for enhancing model accuracy and generalizability. Additionally, statistical features typically lack physical interpretability, complicating the explanation of ML models. Thus, incorporating features with mechanistic meaning can significantly contribute to more interpretable monitoring systems35,36. Recent research has increasingly focused on the interpretability of ML models, which provides deeper insights into their internal workings and facilitates better optimization37,38,39,40.

Most of the existing work on SOC estimation has been limited to specific operational scenarios, often neglecting performance under real-world conditions where the model must function continuously across a battery’s entire lifespan. Health predictions are similarly conducted under idealized conditions, assuming consistent availability of data from uniform charging and discharging cycles, an assumption that is difficult to meet in practical applications. Studies on health monitoring frequently consider ideal scenarios with stable working conditions, while in practice, the varying conditions pose significant challenges to maintaining the effectiveness of monitoring models. The continuous verifications of the SOC and SOH joint estimation model are expected to be conducted during the entire lifespan, which is the practical demand of the battery management system, instead of under several specific tests. Moreover, battery safety conditions are crucial for monitoring, which is key to avoiding hazards like thermal runaway. The potential of continuous state monitoring during dynamic aging to guide safety warnings worthy deeper studies.

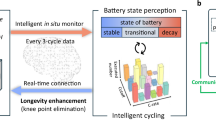

We propose mechanistic leading residual learnings for continuous monitoring of battery states, specifically SOC and SOH, under varying dynamic working conditions throughout the entire lifespan. The general pipeline is adaptable for battery modeling and monitoring with different practical requirements. Using three datasets incorporating different battery types aging under different loading and temperature conditions for verifications, we demonstrate the effectiveness of our model working under different degradation patterns to emulate real-world usage scenarios. The proposed mechanistic leading residual models integrate a model-based approach with ML, where prior estimations and mechanistic features derived from the battery model are used as inputs for residual learners, including a correction model and a compensation model, for enhanced state monitoring. This general pipeline works effectively for both SOC and SOH and constructs a closed-loop framework to support the monitoring of the battery states for the entire lifespan, regardless of the varying loading profiles, temperature conditions, and working ranges (SOC windows) for representations of uncontrollable, randomly varying, and unseen working scenarios. The model is also beneficial for early thermal safety warnings during aging. Through interpretable ML and practical demonstrations, the proposed model enhances accuracy, robustness, and trustworthiness, thereby increasing its potential for real-world applications. The overall framework is illustrated in Fig. 1, where the pathway of the application and the flowchart of the pipeline for residual learning are demonstrated. Additional model details are provided in Fig. S1.

a Demonstration of the closed-loop application of the proposed framework. b Pipeline of the proposed residual learning pipeline for battery SOC and SOH monitoring with mechanistic inspiration. SOC* and SOH* are the direct estimations from the correction model, and SOC** and SOH** are the estimations from the compensation model using the estimated residuals (such as ΔSOH) to be added to the prior estimations (SOCp and SOHp).

Results and Discussion

Data generation

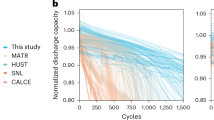

We employed three datasets to evaluate the proposed mechanistic leading residual learning models under dynamic loadings for the full lifespan. Three types of batteries, including pouch, prismatic, and cylindrical cells, which were cycled with urban, highway, and real-world dynamic profiles, are used for verifications under different scenarios.

To emulate the dynamic working and the varying environmental conditions encountered in real-world applications, the first dataset subjected 13 pouch batteries (nominal capacity of 8 Ah) to aging under dynamic discharge across the entire lifespan at different temperatures34. Urban, highway, and hybrid profiles were employed and are illustrated in Fig. S2, while Fig. S3 presents the variations in voltage curves observed during the aging process. Capacity degradation curves relative to equivalent full cycles are shown in Fig. S4, demonstrating that urban dynamic loading profiles generally result in longer battery life compared to highway-based loading, with varying temperature conditions significantly affecting the degradation patterns. There are in total 27840 discharge samples (represented as the dynamic discharge cycles) generated in dataset 1.

Besides, 3 large-format prismatic cells with a nominal capacity of 50 Ah are used in the second aging test until they die at around 20% SOH with sudden death, i.e., rapid degradation in a few cycles. We employed WLTP (Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Procedure) to discharge the cells and used both CC and pulse-constant current (PCC) for charging, as shown in Fig. S5. The pulse was set with an average rate the same as the CC (2 C), while with twice the amplitude. The frequency and duty cycle are 1 Hz and 50%, respectively. The capacity, current, voltage, and temperature curves during aging are shown in Fig. S6. The open circuit voltage (OCV) test was conducted using C/20 constant charging and discharging. The sampling frequency is 10 Hz, and the current and voltage variations for the pulses are tracked precisely. This dataset benefits wide applications, including state monitoring, life prediction, and thermal safety warning. The detailed information of the tested pouch and prismatic cell is listed in Table S1. The sample size, i.e., dynamic discharge curves until capacity drops below 50% of the fresh capacity, is 8590.

Finally, datasets using 25 cylindrical cells from Ref. 41., which were aged with synthetic highway and urban, as well as real city driving profiles, are employed to verify our model for use under different unseen working conditions. Typical current and voltage curves during aging under different loading profiles are shown in Fig. S7, indicating varying discharge patterns observed among different cycling, which therefore cause diverse working scenarios and aging trajectories. We used the first dynamic test after the diagnostic test as the dynamic cycling data during aging, the C/2 discharge capacity before the dynamic cycle as the referenced capacity, and the C/40 discharge curve of a new cell as the OCV curve. There are 483 dynamic discharge curves generated for the model evaluation.

Mechanistic leading residual learning pipelines for enhanced state monitoring

To promote the real-time application of the pipelines, the mechanistic model adopts an equivalent circuit model in this work. For real-time battery SOC estimation, online parameter identification and adaptive filtering methods are employed (see Note S1 for a detailed procedure), where the SOC prior estimations and mechanistic model parameters (e.g., resistance and polarization features) are obtained. Coupled with SOC estimation and coulomb counting for released capacity calculation, the battery capacity can be derived to calculate the prior estimation of battery SOH. The capacity here represents the releasable discharge capacity under the corresponding discharging condition with the specific loading profile, temperature, and aging conditions. Meanwhile, measured parameters (e.g., voltage, current, and released capacity) and identified mechanistic parameters (e.g., identified resistance, OCV, and polarization resistance/capacitance) during dynamic discharging are used to calculate health features, which are composed of several statistical values including mean value, standard deviation, and min and max values of these sequential parameters from a random discharge phase. Detailed feature calculations are described in Methods and Notes S2–S3.

Here, we introduce mechanistic leading residual learners, incorporating a correction model and a compensation model to enhance the state monitoring results from prior estimations. As shown in Fig. 1b and S8, the prior estimations and extracted features serve as input for the ML to output an enhanced estimation and a residual for the prior estimation compensation. Therefore, the function of the correction model is to enhance the prior estimation by direct state predictions, while the compensation model enhances the estimations by adding the predicted residuals to the prior estimations. The prior estimation from the mechanistic model provides stable guidance, and those feature matrices help capture the expected battery states, condition indicators from the real battery responses, as well as the mechanistic features describing the internal conditions. The ML model is built to compensate for the error caused by model uncertainties and other influences, such as OCV variations under varying aging and temperature conditions. The effectiveness of this method is demonstrated through two key states: real-time SOC and the more slowly varying SOH. Note that the compared prior estimations represent the conventional model-based filtering methods. The standard coulomb counting-based calculation is employed to obtain the referenced real SOC and SOH for the evaluations of the conventional model-based filtering method and the proposed residual learning models, while it is not used in any part of the modeling pipelines. Additionally, our model can be easily extended to monitor other relevant states as required, for example, the sensor-less temperature estimations based on the mechanistic features and the lamped-mass thermal model-based prior estimations24.

Results for online parameter identification-based voltage and SOC estimation under varying aging and temperature conditions for pouch cells are shown in Fig. S9. Examples of the variations of the estimated model parameters during aging under three different dynamic profiles are shown in Fig. S10, indicating stable mechanistic feature extractions under different working and aging conditions. To emulate uncertain initializations, error noises (ranging within 5%) are randomly added to the initial SOCs and battery capacities. The findings indicate that accurate and robust estimations are achieved despite these initial errors, maintaining stability across different loading, aging, and temperature conditions. However, errors may still become significant during prolonged usage. By incorporating the estimated SOC from the filtering method as prior knowledge, along with mechanistic and measurable features, our mechanistic leading residual learner further enhances estimation accuracy and robustness. Demonstrations of the monitoring through the correction model and compensation model are presented in Fig. 2a, where the estimation errors underscore the significant potential for enhanced accuracy. Additional estimation results are provided in Fig. S11. Both pipelines exhibit similar performance, as evidenced by the symmetrical estimation distributions shown in Fig. 2b, and the densities match the regular usage conditions. Results when only prior estimation is used as input are provided in Fig. S12 and Table S2, which indicate the importance of mechanistic features to enable more accurate and robust estimations. The root mean square error (RMSE) for the two residual learners is reduced to 0.57% and 0.56%, respectively, a significant improvement from the initial 2.20% (see Table S2 for detailed RMSE and mean absolute error (MAE)).

a Error distributions before and after the enhancement by the residual learners. b Distributions of estimations obtained by the two residual learning pipelines. c Demonstration of the prior estimation for battery health. The estimated SOC from random partial dynamic discharging is used for the capacity (i.e., Capp) and SOH (i.e., SOHp) calculations, and the prior estimations exhibit a high correlation coefficient (0.959) to the real capacities, providing knowledge, together with mechanistic features, for the following ML enhancement. d Predictions results for the correction model (SOH*), where R2 represents the goodness of fit. e Prediction results for the compensation model (ΔSOH). f Error distributions of the results from the prior calculations and after enhancement by the two mechanistic leading residual learners.

Evaluating battery health under practical dynamic working conditions and varying depths of discharge (DOD) is challenging due to diverse operational requirements. To meet real-world dynamic working applications, we predict battery health based on random DOD in partial dynamic discharges. As shown in Fig. S13, the SOC ranges indicate the adaptability of the residual learners to monitor battery health status under uncertain working DODs with varying loading profiles. The corresponding average temperature distribution highlights the model’s generalization across a broad temperature range (20–50 °C). The varying working conditions are reflected in the density of capacity distributions relative to running cycles, which underscores the irregularity of degradation patterns and the necessity for timely health estimation during usage. By considering random DODs in real-world applications alongside the estimated SOC, the prior capacity is calculated to guide the residual learners. As depicted in Fig. 2c, the correlation coefficient between the prior estimation and real capacity is 0.959, indicating stable estimations, although large residuals exist. The estimations obtained from the model-based methods are stable despite the moderate accuracy, indicating their great effectiveness in guiding ML models.

Inspired by prior estimations and the mechanistic states, which are derived through sequential information (i.e., the measured data and mechanistic states) during discharging, the residual learners are trained to enhance the accuracy and reliability of health monitoring, thereby guiding safer and more effective operations. The predictions of the two residual learners, i.e., corrected SOH and compensations (Δ SOH) for the prior SOH respectively, shown in Fig. 2d–e demonstrate the coefficient of determination (R2) larger than 0.98 and 0.84 respectively. Here, the SOH is calculated by dividing the present capacity (Capp) by the nominal capacity (Capn). The MAE for the SOH predictions (as listed in Table S3), based on these residual learners, are as low as 0.779% and 0.783%, respectively. Error distributions for the prior SOH and the enhanced estimations, presented in Fig. 2f, highlight significant improvements in accuracy and reliability, with smaller average errors and narrower distribution ranges.

Evaluation and explanation

Maintaining model performance across different SOC ranges during dynamic discharging is challenging but crucial for practical applications. We evaluated the error distributions of two residual learning pipelines across varying SOC ranges under different working conditions. The tightly concentrated error distributions with low values, as shown in Fig. 3a, b, demonstrate the robustness and high accuracy of the models under diverse driving conditions. The absence of significant bias across error sizes and SOC intervals further ensures reliable model performance under random usage scenarios. Error distributions relative to running cycles, as depicted in Fig. S14, also confirm robustness across different aging stages. Our residual learners are adaptable to various machine-learning algorithms, making them versatile for different practical requirements and computational resources. We demonstrate the performance of six different machine-learning algorithms using the two mechanistic learning residual learning pipelines, as shown in Fig. 3c. All results reflect average performance over ten iterations, each with a distinct training-testing set, with estimation errors consistently below 2.2% across the different models. Notably, significant improvements were achieved even with more lightweight machine-learning models like KNN (K-nearest neighbors) and DT (decision tree), highlighting their potential for real-world implementations where computational resources may be limited. The pipelines for residual learning are also suitable for other ML algorithms, indicating great generalizability over various application requirements. Detailed descriptions of the ML algorithms are provided in Note S4.

a, b Robustness evaluation for random SOC working ranges. c. Performance based on different ML models employed in the residual learners. d–f the model performance for SOH monitoring with different ratios of data for training under 10 times random validations for model-based filtering estimations, correction model, and compensation model, respectively. g SHAP feature importance analysis results for the six most important features in battery SOH predictions for two residual learners. h SHAP analysis for feature importance analysis of the two residual learners in SOC estimations.

We then evaluate the model performance with different ratios of data splitting for training and testing, since different working conditions cause varying aging patterns. Fig. 3e, f show the results of the MAE for the two residual learners under 10 times validations with different split data sets, and the results of RMSE and R2 are demonstrated in Fig. S15. With the increased training ratio from 0.1 to 0.9, a clear trend of accuracy increment was seen by the reduction trends on MAE and RMSE. There are no obvious differences for the model-based prior estimations, witnessed by the error differences varying within 0.1% under different testing cases in Fig. 3d. Obvious improvements are seen before the training ratio surpasses 50%, and improvement after that becomes smaller. As shown in Fig. S16, where the training data and testing data are demonstrated, after the training ratio surpasses 50%, the testing data distributions are almost covered by the training data distributions. However, even when the training data only takes up 10% of the whole data, i.e., the testing data covers many unseen conditions from the training data, the accuracy is still high (less than 1.2% for MAE and 1.7% for RMSE). Having R2 greater than 0.96 under all testing scenarios indicates high extrapolation capability. One major reason is that the model-based estimations provide stable and reliable prior knowledge for the residual learning pipeline, while the mechanistic features also help improve the accuracy under different scenarios.

To further understand the impactful features for the residual learners, SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) analysis is employed42,43,44,45,46. Additionally, a correlation coefficient map is provided in Fig. S17. As shown in Fig. 3g, the prior knowledge derived from battery model-based estimations exerts the dominant influence on the predictions of the residual learner, effectively ensuring robust data-driven estimations, which is also proven by the stable estimations in Fig. 3d. These model-based filtering estimations demonstrate greater resilience to unseen conditions due to the mechanistic constraints, offering reliable information that helps mitigate the primary limitation of ML models, namely poor generalization under unseen conditions. Mechanistic features also significantly impact SOH predictions for the two residual learners, underscoring their importance in enhancing accuracy. The detailed SHAP values for all the features are shown in Figs. S18 a–b. Not all features with high correlation coefficients shown in Fig. S17 have had a high impact on the output. We found that some of those features are redundant to other highly impacted features from the high mutual correlation coefficients. For this case, the random forest model helps remove redundant features and improves monitoring accuracy, eliminating the tedious manual feature selection process47. Comparisons with models using only the mechanistic features (excluding prior estimations) or only the prior estimations (excluding physical features) are presented in Figs. S12 and S19 for SOC and SOH monitoring, demonstrating that our mechanistic leading residual learners achieve better accuracy and robustness. Interestingly, the model relying solely on prior knowledge performs the worst, likely because similar prior estimations under different conditions can mask real differences, which mechanistic features can reveal to improve accuracy across scenarios. The mean absolute SHAP values for SOC residual learners, shown in Fig. 3h, further indicate that prior estimations from the filter provide the most critical guidance for the ML model, while mechanistic information, such as OCV and resistance, aids the estimations, and direct measurements have less impact.

Varying verifications

We further employed our model for the state monitoring of different battery types with different aging patterns caused by different cycling conditions. The dynamic aging of large-format prismatic cells is verified. As shown in Fig. 4a, three large-format prismatic cells are aged with CC/PCC charging and WLTP dynamic discharging, which experience accelerated aging after SOH drops below the knee points. The average current of the pulses remains the same as the constant current, as shown in Fig. 4b. While different battery impedances cause the voltage to vary differently, and according to the heat generation, the cells have higher temperatures using pulse current compared to the constant current. Around 10°C difference for the maximum temperature and 3.5°C difference for the average temperature during cycling are seen for the two different charging protocols. These large thermal condition differences during cycling become the main cause of the different lifetimes for the cells under constant or pulse currents. Previous related works have revealed that pulse currents have an influence on battery lifetime. The battery aging is coupled and influenced by current profiles, temperature, current rates, etc., thus, we advocate coupling mechanisms and battery types during evaluations for the lifetime extension strategy designs.

a Full lifespan degradation curves, temperature curves, and resistance curves of the three cells during aging. ΔT represents the temperature difference between the different cycling conditions. b Illustration of the constant and pulse loading currents and the corresponding voltage curves. c SOC monitoring results and interpretations for the mechanistic leading correction and compensation models. d SOH monitoring results and interpretations for the mechanistic leading correction and compensation models.

We continuously age the batteries until they die, where accelerated aging is seen. As shown in Fig. S20, the battery is heavily swelled after aging, and the thermal safety issue (largely and rapidly increased temperature) occurred as demonstrated in Fig. 5a. Interestingly, the battery capacity degradation accelerated earlier (around 100 cycles) than the thermal safety issue happened, and the identified mechanistic resistances also show earlier detection. Therefore, accurate estimations of the battery capacity and mechanistic states are also crucial to guiding safety management, which helps with early warning of battery safety conditions before thermal issues during operations.

a Training and testing cells split strategies. b SOC and SOH monitoring results for the three validation cases. c Feature interpretation of the mechanistic leading models for the SOC and SOH monitoring, where the definition of the features is provided in Note S2.

The monitoring results for the cells, until SOH (current capacity divided by initial capacity) drops below 50%, are shown in Fig. 4cd, where the total discharging curves are randomly divided into training and testing datasets with a 50% portion of each. The mechanistic leading correction model and compensation model show improved SOC and SOH monitoring for the full lifespan with MAE of less than 0.50% and 0.68%, respectively, as listed in Table S4. SHAP interpretation also indicates the most important impact of the prior estimation and reflects the importance of the mechanistic features. Due to the high linear relationships between the corrected and prior estimations, while the higher nonlinear relationships of the residuals between the prior and real estimations, the mechanistic features have higher impacts on the compensation model compared to the correction model. Both models show improved monitoring and reveal the performance of the proposed mechanistic leading residual learning models. More importantly, the potential of early thermal safety warning can be achieved during operation and aging.

Finally, cylindrical batteries from Ref. 41. are employed for the verification of the proposed models by further considering unseen working conditions. Three different validation cases are generated using cells with different synthetic profiles or real driving profiles-based aging. Specifically, as shown in Fig. 5a, cells with independent highway or urban loading profiles are divided into a training dataset and the validation 1 dataset. The loading profile of combined highway and urban loadings is included in the validation 2 dataset, and the cells with two city driving profiles are used in the validation 3 dataset. Therefore, we evaluated our mechanistic leading residual learning models with different real applications, considering unseen validation scenarios. Typical loadings and the related prior estimations are demonstrated in Fig. S21. The state monitoring and corresponding interpretation results are shown in Fig. 5b, c, respectively. More detailed results for the three validation cases are shown in Figs. S22–S24 and Tables S5–S6. MAE for the SOC estimation keeps below 1.5% and below 1.8% for SOH estimations for all three validation cases with both the correction model and the compensation model. All the cases indicate enhanced state monitoring performance compared to conventional model-based methods, even under unseen loadings for the whole lifespan. Similar interpretations can be summarized from the SHAP results, i.e., the prior estimations play significant roles for both the correction model and compensation model, while the mechanistic features provide critical information and have higher impacts on the compensation model compared to the correction model. Though the prior estimations are the most significant information, mechanistic parameters are essential for the model, as shown in Fig. S25, where the errors may increase instead by only using prior estimation for the model input. Only one fresh OCV curve is used for the estimations instead of updating during aging, which would require more tests and need further calibrations in real-world applications, and the results indicate the residual models are effective to learn the change during aging for accuracy enhancement.

In real-world applications, the sampling frequency is usually reduced, e.g., 0.1 Hz, so that the estimation accuracy is further deteriorated. The prior estimations with enlarged errors can also be enhanced by our mechanistic leading residual learners. We down-sampled the original data with 0.1 Hz and re-tested the three validation cases to evaluate the robustness of our models in potential real application conditions. The down-sampled currents and original currents (1 Hz) for different loading profiles are shown in Fig. S26, where the currents with 0.1 Hz lost fidelity. Therefore, the prior estimations became worse compared to the results with 1 Hz sampled currents (Fig. 5b), as shown in Fig. S27. Based on the proposed correction model and compensation model, the accuracies are enhanced with MAE less than 1.92% and 3.58% for SOC and SOH monitoring (which are more than 3.4% and 5.5% of filtering based-prior estimations for all the three cases), respectively, demonstrating the effectiveness in low sampling frequency applications. Through model interpretation, we noticed that, though the prior estimations are still the most important information, the accuracy is worse in these cases, which makes the mechanistic features become more important for the model to enhance state monitoring.

We have verified the models using real-world driving cycles for potential real-world EV applications. To further evaluate the model extrapolation to other application scenarios, such as grid storage, we applied the same model trained based on the training cells in Fig. 5a for the verification of cells aged with three different kinds of periodic profiles. The results for the SOC and SOH monitoring are shown in Fig. S28, indicating the effectiveness of the proposed model for accuracy enhancement even under quite different unseen loading profiles and aging trajectories.

Closed-loop application entire lifespan

The mechanistic leading residual learners facilitate collaborative monitoring of different battery states throughout the entire lifespan, with capacity updating during each dynamic discharging cycle. To validate their effectiveness and the extrapolation capability of the proposed pipeline, we applied these learners for the monitoring of a cell from dataset 1 aged under hybrid discharging loads with varying temperature conditions to emulate the daily usage of EVs in seasonal scenarios, as shown in Fig. 6. The data from this cell is not included in the training dataset for unseen condition monitoring and the test is conducted every 10 cycles for demonstration consideration. Real-time SOC estimations at four distinct aging stages (Fig. 6a–d) across the lifespan demonstrate the model’s ability to track SOC variations during dynamic operations accurately. Note that without closed-loop state updating, the estimation errors are enlarged during operation, as compared in Table S7. The two residual learners’ effectiveness in monitoring SOC during dynamic operations over the full lifespan is further evidenced in Fig. 6e, confirming their capability to accurately track SOC curves in varying DODs, thereby ensuring safe operations. A notable advancement of our model is its ability to precisely track capacity degradation under random partial dynamic operation profiles, leveraging the mechanistic leading residual learners.

As illustrated in Fig. 6e, the residual learners successfully follow the degradation path during dynamic operations, enabling timely capacity updates for real-time SOC monitoring and guiding necessary maintenance. The effectiveness and the extrapolation capability are proven to be good for the proposed pipeline. Additional results and comparisons are presented in Fig. S29 and Tables S7–S8. Interestingly, the prior estimation of capacity may become more accurate sometimes. This is because we adopted the closed-loop update for SOC and capacity, so the prior estimation can be very accurate when the SOC estimations have high accuracy. Another interesting application verification is for the testing of the cell with a clearly higher discharge capacity than other cells. We need to normalize the prior capacity by dividing the fresh capacity instead of the nominal capacity here, and then effective monitoring can be achieved, as shown in Fig. S30. Finally, an application for highway loading, the cell with a short lifetime, is also achieved in Fig. S30. Therefore, our model is also easy to transfer under different application scenarios to help enhance the state monitoring.

Then, we show the application for dataset 3 with unseen testing conditions under real-world driving profiles. Note that we also use the dynamic cycle after the diagnostic test for verifications, so the degradation curve is composed of sparse points. By using the training cells in Fig. 5a to train the residual learners, the state monitoring under unseen working conditions (cell 92 aged using real-world driving protocols) entire the lifespan are enhanced, as shown in Fig. 6f. Unseen validation for exemplary cells working under another real city protocols (cell 95) and synthetic Urban + Highway (cell 88) protocols are also shown in Fig. 6f, demonstrating the stability and robustness of our model under varying unseen working conditions, which prove the good extrapolation capability of the proposed mechanistic leading residual learning pipelines. Numerical results listed in Table S9 indicate that the MAE for all the tests is below 1.8% for both SOC and SOH. With enhanced SOC and SOH estimation accuracy through closed-loop operations possibly exceeding 50%, battery systems are poised for improved management and operational performance. This closed-loop structure not only supports effective state monitoring but also self-updates to maintain functionality and provide safety warnings, thereby optimizing the overall management of the battery system without the need for costly and time-consuming offline testing. Furthermore, we evaluate the computational cost for consideration of practical applications. The execution time for the full discharge at each SOH point in Fig. 6f is shown in Fig. S31. Due to the low dimension of features and with a simple machine learning model, only a slight additional time (less than 1 second for the full discharge) is required for the residual learning models for accuracy enhancement.

Overall, we employed our mechanistic leading residual learning with two pipelines for enhanced state monitoring during the whole lifespan with feature interpretations and validations using different battery types and verification cases, which indicates high generalizations of our models. Nevertheless, the verifications are still conducted separately for the three datasets, though varying conditions are considered. It is still hard for cross-battery material applications due to the large discrepancies in the mechanistic features of different batteries caused by the chemical properties. Therefore, future work needs to further investigate the improved approach enabling applications across different battery types, especially for lithium-ion phosphate batteries, which pose a significant challenge to address the impact of hysteresis and OCV flatness in state estimations. In addition, the proposed mechanistic leading hybrid modeling framework is worthy of investigation for improving the electrochemical model fidelity.

Discussion

In conclusion, the development and application of mechanistic leading residual learners have demonstrated significant advancements in the real-time monitoring and management of battery systems. By integrating model-based estimations with ML, these learners effectively track SOC and SOH across the entire lifespan of batteries, even under varying dynamic conditions and partial discharges. The adaptability of these models to different operational profiles, coupled with their ability to update themselves based on real-time data, ensures robust and accurate battery state monitoring. Furthermore, the interpretable nature and grounding of our models in mechanistic principles provide additional transparency and reliability, making the predictions more understandable and actionable. SHAP analysis successfully identifies the main contribution of the prior knowledge and the significant roles of the features derived from the mechanistic model. Together with the enhanced state monitoring and mechanistic features, early thermal safety warning can be provided to ensure safe operations, especially after aging. The proposed pipelines have good extrapolation capability for unseen scenarios, ensuring effective and reliable monitoring for real-world applications. This closed-loop framework not only enhances operational safety and efficiency but also reduces the need for time-consuming offline testing, making it a promising solution for the practical implementation of advanced battery management systems. The results verified by using three datasets incorporating three different battery types validate the effectiveness of this approach in improving battery performance and longevity, with MAE of less than 1.6% for both SOC and SOH estimations even under real-world loadings in unseen validations, paving the way for more reliable, efficient, and interpretable energy storage solutions. Our models maintain accuracy with reduced sampling frequencies (0.1 Hz), presenting great potential for real-world EV applications.

Further investigations are required to validate the proposed methods across battery chemistries and within battery packs. While the lightweight ML models and equivalent circuit approaches employed here offer computational efficiency, their deployment in real-world battery management systems will necessitate additional hardware in loop verifications.

Methods

The experimental setup is aimed at emulating real dynamic aging. To this end, three datasets are included in this work. The first dataset includes three different dynamic loading profiles to age pouch batteries (MGL SPIM08HP 8 Ah high power pouch cell) under both constant and varying temperature conditions. Specifically, the representative loading profiles for urban (UDDS), highway (HWFET), and hybrid (combination of UDDS and HWFET) working conditions are employed for discharging, while the multi-constant current charging is used for charging during the aging test34. The chemistry is nickel cobalt aluminum Oxide (NCA) and graphite, and the voltage limit is 2.8–4.2 V. The loading currents of each type of cycling test are shown in Fig. S2. Two different temperature conditions, including constant temperature (25°C) and variable temperature (15-25-35°C) are set for the testing environment. More details about the experiment and data processing are depicted in Note S5. In the second dataset, we use three large-format prismatic cells (L148N50B 50 Ah), which are widely employed in EVs, for dynamic aging with WLTP profiles. The cathode chemistry is nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC), the anode is graphite, and the voltage range is set as 2.75–4.3 V. One cell is charged with a constant current of 2 C, and the other employs pulse currents (1 Hz, 50% duty cycle, 4 C amplitude) for charging. The loading currents are shown in Fig. S5, and the aging test is conducted in a thermal chamber with a controlled 35°C. The sampling frequency is set as 10 Hz, which enables the tracking of variations during pulse loadings. The OCV test is conducted with a low constant current of C/20. The third dataset is from Stanford University, where the cylindrical cells are aged with both synthetic urban and highway dynamic loadings, and more practical real-world loading41. Periodical diagnostic tests are conducted where the real capacities can be obtained. The first dynamic discharge cycle after the diagnostic test is used for verification, where the real capacity can be obtained for verification from the diagnostic test. Furthermore, the sampling frequency is artificially reduced to 0.1 Hz to generate data for the robustness verification of our models in real-world applications.

Battery SOC and SOH, which represent the charge state in a short-time horizon and the health state in a long-time horizon, are monitored for the verification of the proposed mechanistic leading residual learning pipelines. The SOC definition is expressed as

where I is the loading current, t is the current time, and Cap depicts the battery capacity. With the equivalent circuit model, battery dynamic behavior is captured with the real-time identified model parameters. The parameter matrix identification can be described as

The relationship between battery SOC and OCV (identified from \({{{\mathbf{\theta }}}}\)) can be mapped through the OCV test, which is shown in Fig. S32, indicating that different battery types have different shapes of OCV curves. Then, the filtering approach is employed for the posterior real-time SOC estimation, which can be expressed as

By calculating the released capacity within one selected SOC window, the prior calculation of battery capacity and the corresponding SOH are obtained through

The features from the identified battery model parameters and the statistical features are extracted along with the prior estimations to construct the feature matrix \({{{\mathbf{\varphi }}}}\). Specifically, three types of features are extracted in this work. First, the prior estimations for the SOC and SOH from the filtering method serve as the main features for the two residual models. In addition, in order to inform the ML model of the mechanistic states, the features from the mechanistic model are derived. For SOC monitoring, the real-time identified resistance, polarization resistance and capacitance, and the OCV are used as the mechanistic features. For SOH monitoring, in consideration of the sequential information and the aging information derived from the dynamic discharging process, the features such as mean value, standard deviation, and maximum value of the mechanistic parameters and the estimated SOC are derived. The last category is the measured features, i.e., the measured current and voltage for the SOC model and the corresponding derived statistical features. The full description of the features is detailed in Note S2.

Then, the prior estimations and the extracted features are input for the ML model to get enhanced monitoring results. Two residual models are proposed in this work for state monitoring enhancement, and the structures are shown in Fig. S8. The first model is the correction model, and the function is to enhance the prior estimations directly with an improved estimation. The function can be expressed as

where \({Z}_{p}\) is the prior estimation and \(Z*\) is the enhanced estimation from the correction model. For the second residual model, the compensation model, the function of the ML is to estimate the residuals between the prior estimations and the real values to compensate for the prior estimations. The compensation model for enhanced state monitoring can be expressed as

where \({\mbox{Z}}*\ast \) is the enhanced state estimation through the compensation model. All the notations and abbreviations are summarized in Table S10.

Data availability

Source data for the figures in the main text, including the reproduction code, are provided with this paper in the Source Data file. All data including cycling data and OCV data from the pouch and prismatic cells are (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15606246) for results generation. The cylindrical cell dataset is available from Stanford University at (https://purl.stanford.edu/td676xr4322). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code for the main text figures reproduction is provided together with the Source Data file. All codes for modeling and results generation are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1560624648.

References

Pozzato, G. et al. Analysis and key findings from real-world electric vehicle field data. Joule 7, 2035–2053 (2023).

Zhang, H., Hu, X., Hu, Z. & Moura, S. J. Sustainable plug-in electric vehicle integration into power systems. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 1, 35–52 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. A comprehensive review of battery modeling and state estimation approaches for advanced battery management systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 131, 110015 (2020).

Jones, P., Stimming, U. & Lee, A. A. Impedance-based forecasting of battery performance amid uneven usage. Nat. Commun. 13, 4806 (2022).

Ng, M. F., Zhao, J., Yan, Q., Conduit, G. J. & Seh, Z. W. Predicting the state of charge and health of batteries using data-driven machine learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 161–170 (2020).

Sulzer, V. et al. The challenge and opportunity of battery lifetime prediction from field data. Joule 5, 1934–1955 (2021).

Mc Carthy, K., Gullapalli, H., Ryan, K. M. & Kennedy, T. Review—Use of Impedance Spectroscopy for the Estimation of Li-ion Battery State of Charge, State of Health and Internal Temperature. J. Electrochem Soc. 168, 080517 (2021).

Zhao, P. et al. Challenges and opportunities in truck electrification revealed by big operational data. Nat. Energy 9, 1427–1437 (2024).

Rahimi-Eichi, H., Ojha, U., Baronti, F. & Chow, M. Y. Battery management system: An overview of its application in the smart grid and electric vehicles. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 7, 4–16 (2013).

Palacín, M. R. & De Guibert, A. Batteries: Why do batteries fail? Science (1979) 351, 1253292 (2016).

Che, Y., Hu, X., Lin, X., Guo, J. & Teodorescu, R. Health prognostics for lithium-ion batteries: mechanisms, methods, and prospects. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 338–371 (2023).

Thelen, A. et al. Integrating physics-based modeling and machine learning for degradation diagnostics of lithium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 50, 668–695 (2022).

Nascimento, R. G., Corbetta, M., Kulkarni, C. S. & Viana, F. A. C. Hybrid physics-informed neural networks for lithium-ion battery modeling and prognosis. J. Power Sources 513, 230526 (2021).

Hu, X., Xu, L., Lin, X. & Pecht, M. Battery lifetime prognostics. Joule 4, 310–346 (2020).

Aykol, M. et al. Perspective—combining physics and machine learning to predict battery lifetime. J. Electrochem Soc. 168, 030525 (2021).

Li, Y., Ye, M., Wang, Q., Lian, G. & Xia, B. An improved model combining machine learning and Kalman filtering architecture for state of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries. Green. Energy Intell. Transp. 3, 100163 (2024).

Yu, H., Lu, H., Zhang, Z. & Yang, L. A generic fusion framework integrating deep learning and Kalman filter for state of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries: analysis and comparison. J. Power Sources 623, 235493 (2024).

Tian, J., Xiong, R., Lu, J., Chen, C. & Shen, W. Battery state-of-charge estimation amid dynamic usage with physics-informed deep learning. Energy Storage Mater. 50, 718–729 (2022).

Qi, W., Qin, W. & Yun, Z. Closed-loop state of charge estimation of Li-ion batteries based on deep learning and robust adaptive Kalman filter. Energy 307, 132805 (2024).

Tian, Y., Lai, R., Li, X., Xiang, L. & Tian, J. A combined method for state-of-charge estimation for lithium-ion batteries using a long short-term memory network and an adaptive cubature Kalman filter. Appl Energy 265, 114789 (2020).

Tu, H., Moura, S., Wang, Y. & Fang, H. Integrating physics-based modeling with machine learning for lithium-ion batteries. Appl Energy 329, 120289 (2023).

Pozzato, G., Li, X., Lee, D., Ko, J. & Onori, S. Accelerating the transition to cobalt-free batteries: a hybrid model for LiFePO4/graphite chemistry. NPJ Comput Mater. 10, 14 (2024).

Surya, S., Samanta, A., Marcis, V. & Williamson, S. Hybrid electrical circuit model and deep learning-based core temperature estimation of lithium-ion battery cell. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electr. 8, 3816–3824 (2022).

Zheng, Y., Che, Y., Hu, X., Sui, X. & Teodorescu, R. Sensorless temperature monitoring of lithium-ion batteries by integrating physics with machine learning. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electr. 10, 2643–2652 (2023).

Liu, X., Li, K., Wu, J., He, Y. & Liu, X. An extended Kalman filter based data-driven method for state of charge estimation of Li-ion batteries. J. Energy Storage 40, 102655 (2021).

Singh, S., Ebongue, Y. E., Rezaei, S. & Birke, K. P. Hybrid modeling of lithium-ion battery: physics-informed neural network for battery state estimation. Batteries 9, 301 (2023).

Wang, F., Zhai, Z., Zhao, Z., Di, Y. & Chen, X. Physics-informed neural network for lithium-ion battery degradation stable modeling and prognosis. Nat. Commun. 15, 4332 (2024).

Zhu, J. et al. Data-driven capacity estimation of commercial lithium-ion batteries from voltage relaxation. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–10 (2022).

Severson, K. A. et al. Data-driven prediction of battery cycle life before capacity degradation. Nat. Energy 4, 383–391 (2019).

Geslin, A. et al. Selecting the appropriate features in battery lifetime predictions. Joule 7, 1956–1965 (2023).

Li, T., Zhou, Z., Thelen, A., Howey, D. A. & Hu, C. Predicting battery lifetime under varying usage conditions from early aging data. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 5, 101891 (2024).

Li, M. et al. Lithium inventory tracking as a non-destructive battery evaluation and monitoring method. Nat. Energy 9, 612–621 (2024).

Lu, J. et al. Deep learning to estimate battery state of health without additional degradation experiments. Nat. Commun. 14, 2760 (2023).

Che, Y., Zheng, Y., Onori, S. & Hu, X. Increasing generalization capability of battery health estimation using continual learning. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 4, 101743 (2023).

Kim, S. et al. Accelerated battery life predictions through synergistic combination of physics-based models and machine learning. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 101023 (2022).

Kim, M., Kim, I., Kim, J. & Choi, J. W. Lifetime prediction of lithium ion batteries by using the heterogeneity of graphite anodes. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 2946–2953 (2023).

Murdoch, W. J., Singh, C., Kumbier, K., Abbasi-Asl, R. & Yu, B. Definitions, methods, and applications in interpretable machine learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 22071–22080 (2019).

Rudin, C. et al. Interpretable machine learning: Fundamental principles and 10 grand challenges. Stat. Survevs 16, 1–85 (2022).

Gilpin, L. H. et al. Explaining Explanations: An Overview Of Interpretability Of Machine Learning. Proceedings - 2018 IEEE 5th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), 80–89 (2018).

Galuppini, G. et al. Improving diagnostics and prognostics of implantable cardioverter defibrillator batteries with interpretable machine learning models. J. Power Sources 610, 234668 (2024).

Geslin, A. et al. Dynamic cycling enhances battery lifetime. Nat. Energy 10, 172–180 (2025).

Nielsen, R. L. et al. Data-driven identification of predictive risk biomarkers for subgroups of osteoarthritis using interpretable machine learning. Nat. Commun. 15, 2817 (2024).

Yang, J., Tao, L., He, J., McCutcheon, J. R. & Li, Y. Machine learning enables interpretable discovery of innovative polymers for gas separation membranes. Sci. Adv. 8, 9545 (2022).

Linardatos, P., Papastefanopoulos, V. & Kotsiantis, S. Explainable AI: a review of machine learning interpretability methods. Entropy 23, 18 (2021).

Samek, W., Montavon, G., Lapuschkin, S., Anders, C. J. & Müller, K. R. Explaining deep neural networks and beyond: A review of methods and applications. Proc. IEEE 109, 247–278 (2021).

Lundberg, S. M., Allen, P. G. & Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. NIPS'17: Proc. 31st Int. Conf. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 4768–4777 (2017).

Sun, W. & Braatz, R. D. Smart process analytics for predictive modeling. Comput Chem. Eng. 144, 107134 (2021).

Che, Y. et al. Mechanistic leading residual learning for battery state monitoring entire full life. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15606246 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation (Y. Che and R.D. Braatz), Independent Research Foundation Denmark (Y. Che), and Villum Foundation (R. Teodorescu, Y. Che, and Y. Zheng). We would like to thank Wenxue Liu for the OCV test of the pouch cell and paper review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.C. Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Writing-Original Draft, Visualization, Funding Acquisition. Y.Z. Methodology, Investigation, Writing-Original Draft, Visualization. J.R. Validation, Writing - Review & Editing. J.G. Writing - Review & Editing. S.W. Writing - Review & Editing. R.T. Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing. R.D.B. Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding Acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shun Zheng, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Che, Y., Zheng, Y., Rhyu, J. et al. Mechanistically guided residual learning for battery state monitoring throughout life. Nat Commun 17, 855 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67565-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67565-z