Abstract

Photonic time crystals host a variety of intriguing phenomena, from wave amplification and mixing to exotic band structures, all stemming from the time-periodic modulation of optical properties. While these features have been well described classically, their quantum manifestation when coupled to an atomic electric dipole has remained elusive. Here, we introduce a quantum electrodynamical model of photonic time crystals that reveals a deeper connection between classical and quantum pictures: the classical momentum gap arises from a localization-delocalization quantum phase transition in a Floquet-photonic synthetic lattice. Leveraging an effective Hamiltonian perspective, we pinpoint the critical momenta and highlight how classical exponential field growth manifests itself as wave-packet acceleration in the quantum synthetic space. Remarkably, when a two-level atom is embedded in such a photonic time crystal, its Rabi oscillations undergo irreversible decay to a half-and-half mixed state—a previously unobserved phenomenon driven by photonic delocalization within the momentum gap, even with just a single frequency mode. Our findings establish photonic time crystals as versatile platforms for studying nonequilibrium quantum photonics and suggest new avenues for controlling light matter interactions through time domain engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent advances in photonics have moved beyond spatially periodic media such as conventional photonic crystals and metamaterials1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, turning instead to structures whose optical properties are periodically modulated in time9,10,11,12. Among these dynamic media are photonic time crystals (PTCs), in which parameters such as refractive index or permittivity follow a strict periodic pattern in time13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. This shift to time-domain periodicity has unveiled unusual photonic band structures and unique ways of manipulating light under time-varying conditions21,22,23,24,25. PTCs thus offer prospects for advanced control of wave propagation, energy transfer, and frequency conversion, expanding beyond the traditional realm of static spatial lattices.

In classical descriptions, PTCs exhibit non-Hermitian behavior arising from time-periodic modulations, giving rise to gain and loss phenomena whose physical origin is distinct from that of static photonic systems11,18. This non-Hermiticity manifests in distinctive band structures marked by momentum gaps and exceptional points, and the breakdown of Floquet-mode orthogonality—quantified by the Petermann factor—heavily influences the photonic density of states near the gap edge13,14,18,26,27. These changes in the photonic density of states are directly relevant for wave amplification, lasing, and frequency conversion, while also influencing atomic light emitter interactions by altering emission and absorption pathways10,14,17,18,28, thus bridging classical PTC phenomena with inherently quantum regimes.

Despite extensive classical analyses via Maxwell’s equations and Floquet theory, a critical gap remains in understanding the quantum properties of PTCs. Classical models can effectively capture non-Hermitian effects (e.g., momentum gaps, exceptional points) but fall short in describing quantum dynamical phenomena unique to time-varying environments. In other words, non-Hermiticity at the classical level can obscure how photons truly behave, particularly when light-matter interactions such as spontaneous emission and Rabi oscillations enter the picture. For instance, the formation of momentum gaps is often attributed to pseudo-Hermiticity breaking, yet quantization of Maxwell’s equations yields a Hermitian Hamiltonian, even in PTCs12. This raises a central question: How can the non-Hermitian features observed classically be reconciled with the Hermiticity of quantum electrodynamical descriptions? Clarifying this paradox is vital for exploring purely quantum effects such as photon pair creation and annihilation, squeezing, and Floquet vacuum fluctuations, all of which exceed the scope of classical models.

The quantum mechanical aspects of photonic states within the momentum gap have been put forward recently in ref. 29, which employs the classical and quantum theories of photonic temporal interfaces30,31. By viewing the time-varying medium as a scattering source of photonic states, the transition probability can be computed as a function of the squeezing parameter, which is in turn connected to the reflectivity. The exponential growth of the photon number in time from the pair generation in the PTC has the same root as the dynamical Casimir effect (DCE)32,33,34,35. The amplification of vacuum fluctuations by a parametrically driven optical cavity has drawn much attention as a means to engineer the photonic vacuum and it has far-reaching applications to the physics of the expanding universe and the Hawking radiation36,37,38,39,40,41,42. In spite of the similarity, the PTC medium is homogeneous in space and therefore right- and left-moving photonic modes (\(| \pm k\rangle\)) are distinct modes in contrast to the DCE. This means the photonic states in the PTC are specified by momentum. As a result, when an atomic electric dipole is coupled to the PTC, the time-varying light-atom interaction allows the exchange of photons with a total momentum quanta followed by the transition of atomic states, and unconventional quantum dynamics emerges in the momentum domain. Such quantum electrodynamics in the PTC has not been explored, and in our work we present the Floquet formalism, which provides a platform to treat the PTC time-periodically coupled to an atomic electric dipole in a unified manner in Floquet-photonic synthetic space.

Our approach reveals how classical non-Hermitian features, such as momentum gaps and time-periodicity induced gain, map onto a localization-to-delocalization quantum phase transition in a Floquet-photonic synthetic lattice. Notably, we show that Rabi oscillations in a two-level system coupled to a PTC settle into an incoherent mixed state within the momentum gap, even in single-frequency photonic modes, a phenomenon triggered by photonic delocalization under time-periodic driving. This dynamics cannot be fully captured by classical theories alone, placing PTCs at the forefront of non-equilibrium quantum photonics. Our results highlight PTCs as a powerful platform for exploring new light-matter interaction regimes and advancing quantum photonic technologies.

Results

Effective description of the quantum PTC

The PTC medium is homogeneous in space and supports a continuum set of momenta k. We focus on the quantum dynamics of photonic modes with momentum k and − k because other modes \(| {k}^{{\prime} }\ne \pm k\rangle\) are uncoupled. The medium is time-periodically varying, as reflected in the permittivity ε(t) = ε(t + T). In natural units adapted for electromagnetism (ℏ = c = ε0 = 1), the Hamiltonian of the system is given by12

where \({\widehat{n}}_{k}={\widehat{a}}_{k}^{{{\dagger}} }{\widehat{a}}_{k}\) is the photon number operator for mode k, and \(\alpha (t)=\frac{1}{2}[1-{\varepsilon }^{-1}(t)]\). In the photon number basis, defined by \({\widehat{n}}_{k}| {n}_{k}\rangle={n}_{k}| {n}_{k}\rangle\), the first term of the Hamiltonian corresponds to the energy contribution from the photon number. The second term describes the creation and annihilation of photon pairs, governed by the operator \({\widehat{a}}_{k}{\widehat{a}}_{-k}\), which acts as \({\widehat{a}}_{k}{\widehat{a}}_{-k}| {n}_{k},{n}_{-k}\rangle=\sqrt{{n}_{k}{n}_{-k}}| {n}_{k}-1,{n}_{-k}-1\rangle\). This term generates off-diagonal elements in the photon number Hilbert space, \(\{| {n}_{k},{n}_{-k}\rangle \}\), representing a hopping process between adjacent photon number states. As a result, the Hamiltonian can be interpreted as a single-particle problem on a 1-dimensional lattice, with both the onsite potential and hopping amplitudes varying periodically in time. Note that the total momentum P = k(nk − n-k) remains conserved under the hopping process. The Hamiltonian is expressed as

where μn(t) = (1 − α(t))(nk + n−k), \({c}_{{{{\bf{n}}}}}^{{{\dagger}} }| 0\rangle=| {n}_{k},{n}_{-k}\rangle\), and \({\alpha }_{{{{\bf{n}}}}}(t)=\sqrt{{n}_{k}{n}_{-k}}\alpha (t)\). Hereafter, we adopt the specific form \(\alpha (t)={\alpha }_{c}\cos (\Omega t)\) for the time-periodic modulation of the permittivity. The coefficients depend not only on time, but also on the photonic site index, n = (nk, n−k). The lattice sites are defined only for non-negative photon numbers, nk, n−k≥0. The linearly increasing onsite potential, known as the Wannier-Stark ladder43,44,45,46,47, leads to the localization of eigenstates. On the other hand, the hopping amplitude varies linearly across the photonic sites, which increases the quantum tunneling amplitude to photonic sites with higher numbers, providing the delocalizing effect. The setup establishes the quantum PTC as a promising new model system for investigating unexplored phenomena. Later, we show that this enables the system to undergo a sharp localization-to-delocalization transition, which occurs at the edges of the momentum gap for all photonic states when an infinitely large number of photonic number states in the Hilbert space are considered, or in the thermodynamic limit. Transformed to a time-periodic single-particle problem, the Floquet formalism is employed to describe it in the frequency domain:

The Hilbert space is spanned by the photon number basis and the Floquet basis, both of which are unbounded; see Fig. 1c. While the Floquet Hamiltonian is in the 3-dimensional synthetic space (nk, n−k; lF), it can be simplified to a 1-dimensional form by collecting Floquet-photonic sites that are relevant only for the formation of the quantum momentum gap near k = Ω/2 and E = 0. For instance, the synthetic sites are grouped by the purple dotted line in Fig. 1c, and they are coupled by the time-periodic modulation of the permittivity. Approaching k = Ω/2, the potential energies of the sites become increasingly similar, as shown in Fig. 1d. Consequently, the effective physics can be described by the following effective Floquet Hamiltonian when αc ≪ 1:

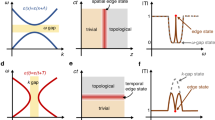

where the Floquet-photonic basis n is introduced, with nk = n−k = lF = n. Since the quantum dynamics is restricted to the photonic states sharing the same total momentum P = k(nk − n-k), for simplicity, we focus on the zero-total-momentum sector with nk = n−k. The underlying physics and the critical phenomena near the momentum gap transition for different total momentum δnk = nk − n−k ≠ 0 remain consistent and unaffected (see Supplementary Note 2). When αc = 0 (i.e., not driven), all (quasi-) eigenenergies of \({\widehat{H}}_{F}^{e{{\mathrm{ff}}}}\) with δnk = 0 are degenerate at zero energy at k = Ω/2 (see Fig. 2a). Therefore, no matter how small the αc-induced quantum tunneling is, a full delocalization of eigenstates in the synthetic space is expected. An intriguing question is what the nature of the transition would be: Will it occur at a single point or be a crossover? Remarkably, this degeneracy of eigenenergies persists even with a nonzero αc, which shifts the critical momentum (i.e., the edge of the momentum gap) to kc± = Ω/2 + δkc± (see Fig. 2b). Note that eigenenergy \({E}_{m}^{\delta {n}_{k}}\) is indexed by m = 0, 1, 2, ⋯ in ascending order of the photon number expectation value \(\langle \widehat{N}\rangle\) for each eigenstate \(| {\psi }_{m}\rangle\) sharing the same total momentum δnk.

a When a classical simple harmonic oscillator (SHO) with frequency ω is quantized, the energy spacing between neighboring eigenstates is ℏω. A similar principle applies to the eigenfrequency spectrum of classical PTCs and the eigenenergy spectrum of quantum PTCs. b The 2D photon number space of a quantum PTC can be grouped with states that share the same total momentum P = ℏck (nk − n−k), which is a good quantum number. The onsite potential and hopping amplitude are time-dependent, as shown in Eq. (2). c By applying the Floquet formalism to the time-periodic Hamiltonian of a quantum PTC, the photonic lattice originally described by (nk, n−k) acquires a third dimension labeled by the Floquet index lF = …, 0, 1, 2, … . d At k = Ω/2, the onsite energies of sites connected by pair creation and annihilation coincide, leading to degeneracy. Even a small coupling αc between these sites can delocalize the eigenstates in the Floquet-photonic space. e A schematic depiction of wave-packet dynamics in the Floquet--photonic space: for \(k\in {{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{band}\), the wave packet remains localized and oscillatory, whereas for \(k\in {{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{gap}\), it becomes delocalized and accelerates in the momentum gap.

a In the absence of driving (αc = 0), all Floquet-photonic sites \(| {n}_{k},{n}_{-k};{l}_{F}\rangle\) are decoupled, and their energies are given by E = k(nk + n−k) − lFΩ. In this plot, we show the eigenenergy spectrum for nk = n−k = lF = 0, 1, 2, ⋯ . b Eigenenergies of the quantum PTC at αc = 0.15 for δnk = 0, 1. The degeneracy at k = Ω/2 is lifted, giving rise to \({k}_{c\pm }=\Omega \,{(2\mp {\alpha }_{c})}^{-1}\). Notably, the energy spacing between eigenstates that differ by one total momentum quanta, \(({E}_{m}^{\delta {n}_{k}=1}-{E}_{m}^{\delta {n}_{k}=0})\), precisely reproduces the classical PTC spectrum ωCPTC(k)(see lower panel). c For a given k, the energy levels of eigenstates that share the same total momentum are equally spaced (see Supplementary Note 1), and this spacing converges to zero at the critical momentum kc−. d For \(k\in {{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{gap}\), the distribution of energy-level spacings follows Wigner--Dyson (orthogonal) statistics, indicating that the eigenstates are delocalized within the momentum gap.

The quantum vs classical momentum gap edge

The aforementioned effective Floquet Hamiltonian has no upper or lower bound, with its elements growing indefinitely as the photon number and Floquet index increase. When diagonalized, the eigenstates converge to a single energy as k → kc± + 0±, thereby making it challenging to accurately estimate kc± using brute-force numerical diagonalization with truncation. We circumvent the issue by employing the transfer matrix method48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55 for the effective Floquet Hamiltonian.

At the critical momentum, the norms of the transfer eigenvalues become unity as the energy gap between the modes vanishes (see Methods). Using this condition, one can identify the values of the critical momenta:

when the permittivity is expressed as \({\varepsilon }^{-1}=1-2{\alpha }_{c}\cos (\Omega t)\). This represents the exact result within the validity of the effective Hamiltonian, and the method can be extended to a more general time-periodic permittivity (see Supplementary Note 3). The location of the momentum gap edge in the classical PTC can also be determined to arbitrary precision using the transfer matrix approach. Since the momentum gap \({{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{gap}=\{k| {k}_{c-} < k < {k}_{c+}\}\) is formed by the hybridization of an infinitely many number of photonic modes sharing the same total momentum, the classical description precisely predicts the location of kc± without any quantum corrections. This is numerically verified by comparing the eigenvalues of \({\widehat{U}}_{F}={{{\mathcal{T}}}}\exp (-i{\int }_{0}^{T}\widehat{H}(t)dt)\) with those of the classical PTC. When \({\widehat{H}}_{F}^{e{{\mathrm{ff}}}}\) is used, it introduces only a constant shift in the critical momenta, preserving all relative features near the critical momentum (see Supplementary Notes 1 and 4). This implies that the physics near kc± is accurately captured by the effective Floquet Hamiltonian in Eq. (4).

The momentum gap transition in the classical PTC is reflected in the imaginary part of the eigenfrequencies, leading to the exponential growth of the fields. In contrast, the quantum Hamiltonian is Hermitian, ensuring that all its eigenvalues are real. The transition in the quantum PTC manifests as a localization-to-delocalization transition of eigenstates in the Floquet-photonic lattice, which is reflected in the distribution of eigenenergy level spacings. For k < kc−, the nearest neighbor eigenenergies are equally spaced (Fig. 2a, b). In contrast, for \(k\in {{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{gap}\), the statistics of eigenenergy level spacings follow the Wigner-Dyson distribution (orthogonal class)56,57 (see Fig. 2d), indicating that the eigenstates are delocalized in the Floquet-photonic space. We next examine the quantum dynamical properties using both the transfer matrix approach and the numerical time evolution of a wave packet in both regimes. This approach offers a unified perspective on both the photonic band structure and the momentum gap, framed within the context of the localization-to-delocalization transition in the synthetic space. Furthermore, it interprets the physics of the classical PTC in terms of its underlying microscopic Hamiltonian.

The localization-to-delocalization transition

The effective Floquet Hamiltonian in Eq. (4) captures two competing mechanisms that govern the dynamical behavior of a wave packet. The first term represents an onsite potential that increases (or decreases) linearly with the site index for k < Ω/2 (or k > Ω/2). This term induces a Wannier-Stark effect, which localizes eigenstates in systems with finite bandwidth44,45,58,59. The second term describes a typical hopping Hamiltonian, but with a hopping amplitude that also increases with the site index, thereby promoting delocalization of quantum states in the Floquet-photonic space. Together, the increasing kinetic and onsite energies create a new quantum mechanical setting, where a localization-to-delocalization transition emerges at the critical momentum kc± in a PTC, even in the absence of quenched disorder.

An essential measure that determines the localization of quantum states is the Lyapunov exponent52,54,60, defined as

where the norm of the wavefunction at site n can be obtained from the multiplication of transfer matrices: Ψ(n) = TnTn−1 ⋯ T1Ψ(0). The Lyapunov exponent γ converges to zero for a delocalized state (indicating that the norm of the state at site n = 0 is equal to that of the state infinitely far away) or to a positive finite value for a localized state, ∣Ψ(n)∣ ~ e−γn. The localization length, ξ = 1/γ, is calculated both analytically and numerically for the effective Floquet Hamiltonian, Eq. (4), of the quantum PTC (see Fig. 3a upper panel). It fully characterizes the nature of the transition at the quantum momentum edge (see Methods). For k < kc−, the localization length is given by

which diverges near the momentum gap edge as ξ ~ ∣k − kc−∣−ν with the critical exponent ν = 1 (see Supplementary Note 2). For \(k\in {{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{gap}\), the localization length ξ diverges, ξ → ∞. In Fig. 3b, the photonic onsite energy, \({E}_{ph}(t)=\langle {\psi }_{t}| {\widehat{H}}_{ph}| {\psi }_{t}\rangle\) where \({\widehat{H}}_{ph}={\sum }_{n=0}^{\infty }(2kn){\widehat{c}}_{n}^{{{\dagger}} }{\widehat{c}}_{n}\) and \(| {\psi }_{t}\rangle={e}^{-i{\widehat{H}}_{F}^{eff}t}| 0,0;{l}_{F}=0\rangle\), is plotted, and it provides a numerical demonstration of this result. Note that the photonic onsite energy is related to the expectation value of the photon number by \({\widehat{H}}_{ph}=k({\widehat{n}}_{k}+{\widehat{n}}_{-k})=k\widehat{N}\). The height of the oscillations indicates the extent to which a wave packet can spread in the Floquet-photon space, and therefore it is proportional to the localization length. The periodicity of the oscillations can be deduced by the energy differences between neighboring eigenstates comprising the initial wave packet: \(| {\psi }_{t}\rangle={\sum }_{m}{c}_{m}{e}^{-i{E}_{m}t}| {\psi }_{m}\rangle\) where \({c}_{m}=\langle {\psi }_{m}| 0,0;0\rangle\) and m is the eigen index. Since the energy difference approaches zero as k → kc−, the periodicity diverges at the critical momentum. (see Supplementary Note 6 for further details).

a The localization length ξ [Eq. (7)] in the band (upper panel) and the photonic-energy growth rate [Eq. (9)] in the momentum gap (lower panel). b Oscillatory photonic energy \({E}_{ph}=k\langle \widehat{N}\rangle\) over time for k < kc−, where the initial wave packet is prepared at nk = n−k = lF = 0. Colors in the legend indicate the ratio k/kc−. c For \(k\in {{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{gap}\), the photonic energy of the same initial wave packet grows exponentially over time. d The inverse participation ratio of eigenstate \(| {\psi }_{m}\rangle\) (m = 0, ⋯ , 50) with δnk = 0.

Within the momentum gap (\(k\in {{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{gap}\)), an initially prepared wave packet at the Floquet-photonic site n = 0, \(| {\psi }_{t=0}\rangle=| 0,0;{l}_{F}=0\rangle\), not only spreads to higher nonzero photonic number states but also accelerates over time. The acceleration of the wave packet in the Floquet-photonic space is associated with the rate of energy transfer from the PTC, where the total number of photons increases as energy is drawn from the source driving the PTC. The quantification of the acceleration is numerically shown in Fig. 3c and can be analytically understood by calculating the time derivative of \(\langle \widehat{N}\rangle=\langle {\psi }_{t}| \widehat{N}| {\psi }_{t}\rangle\), i.e., the center of probability in the Floquet-photonic lattice, where \(| {\psi }_{t}\rangle={e}^{-i{H}_{F}^{eff}t}| {\psi }_{t=0}\rangle\):

which quantifies the photonic energy current flowing into the system. For example, a plane-wave-like wavefunction has a running U(1) phase over space, ψ(x + a) = e ipa/ℏψ(x), and the current carried by the state is related to the momentum, J(x) ~ ℑ [ψ*∂xψ] = p/ℏ. Likewise, in the Floquet-photonic synthetic space, the similar relation ψt(n + 1) = eiϕψt(n) applies as the eigenstates are delocalized (ξ → ∞), and using the transfer matrix method, the analytic expression \(\phi=\arccos (\frac{1-\Omega /2k}{1-\Omega /2{k}_{c-}})\) for \(k\in {{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{band}\) is obtained in the large-n limit (see Supplementary Note 2). On the other hand, the average number of photons in the system is given by \(\langle \widehat{N}\rangle={\sum }_{n}n[{\psi }_{t}^{*}(n){\psi }_{t}(n)]\). Consequently, the exponential growth rate of photonic energy is

which is exactly twice the imaginary part of the (quasi-) eigenfrequency within the momentum gap in the classical PTC, γqu = 2γcl, the energy growth rate of classical electromagnetic waves (see Supplementary Fig. 3).

In the classical PTC, the eigenfrequencies acquire imaginary parts within the momentum gap due to the non-Hermiticity of the classical Hamiltonian. This results in exponential growth of the field strength with an exponent γcl. Within the quantum framework above, we show that the exponential growth of energy at a rate γqu associated with photons can be explained in terms of eigenstates of the quantum Hamiltonian with nonzero momentum in the synthetic lattice. That is, the probability sum of the wave packet is normalized at all times (because the quantum Hamiltonian is Hermitian), but its transport motion toward higher photon number states through pair generating hopping processes leads to the amplification of photonic energy. Our analysis of the quantum PTC offers not only a complementary view of the classical description of the non-Hermitian physics; by decomposing into Floquet-photon quantum states, it provides a photon Fock state resolved understanding of the energy amplification. From a physical perspective, the kinetic energy of a quantum state is proportional to the bandwidth of a lattice model, and our effective Hamiltonian (4) has an increasing hopping strength (or local bandwidth) with synthetic site n. As a result, as a quantum state moves toward a higher n, the effective group velocity increases and this is the source of photon generation at an exponential rate within the momentum gap. It is worth noting that the energy required for the acceleration is supplied by the external driving force of the quantum PTC, contained in \({\widehat{H}}_{Floq}={\sum }_{n=0}^{\infty }(-\Omega )n{\widehat{c}}_{n}^{{{\dagger}} }{\widehat{c}}_{n}\) in (4).

Lastly, the inverse participation ratio of the eigenstate \(| {\psi }_{m}\rangle\), \({IPR}_{{\psi }_{m}}={\sum }_{n=0}^{N}| {\psi }_{m}(n){| }^{4}\), another essential measure of the localization-to-delocalization transition, in the Floquet-photonic space is plotted in Fig. 3d. As the system approaches the critical momentum (k → kc−), the IPR converges to zero in the thermodynamic limit (N → ∞), which is consistent with the diverging localization length. The plateaus of the IPR, one of the unique features in the quantum PTC, arise in the process of delocalization of eigenstates toward n = 0 direction (see Supplementary Note 5 for details). Next, we present Rabi oscillations in the quantum PTC, a distinguishing feature of purely quantum behavior.

The dynamics of the quantum Rabi model in the PTC

When a two-level atom with an electric dipole moment is placed inside a PTC, its interaction with the quantized electromagnetic field is governed by the well-known quantum Rabi model61,62,63. This model predicts coherent oscillations of the ground- and excited-state populations, driven by their coupling to the single frequency photon field. The dynamics of the two-level system is described by the Hamiltonian \({\widehat{H}}_{at}=\Delta (\widehat{I}+{\widehat{\sigma }}_{z})/2\), expressed in the eigenbasis of the ground and excited states. The ground (excited) state is set to Eg = 0 (Ee = Δ). The corresponding electric dipole moment operator is \(\widehat{d}={d}_{0}{\widehat{\sigma }}_{x}\). Focusing on \(| k\rangle\) and \(| -k\rangle\) modes in the quantum PTC, a quantized electric field is coupled to the electric dipole moment of a two-level atom. The interaction Hamiltonian is given by64:

where the coupling depends on the time-periodic permittivity ε(t) and is proportional to \(\sqrt{k} \sim 1/\sqrt{\lambda }\). The coupling constant g includes additional factors that are independent of both time and momentum. The interaction term facilitates coupling between Floquet-photonic states differing by one total momentum unit and the atomic states. Previously, the Hilbert space of the quantum PTC was effectively described by a 1-dimensional wire in the Floquet-photonic space at a fixed total momentum. When coupled to atomic states, the Hilbert space accessible to a wave packet expands to an array of coupled wires corresponding to different total momenta P = k(nk − n−k) (see Fig. 4a). When the energy of the excited atomic state is tuned to Δ = k, the Floquet-photonic sites combined with the atomic state (shown in the left column of Fig. 4a) all share the same onsite energy (Eon = k(nk + n−k) − lFΩ + Eat) at k = Ω/2, indicating that the effective physics near E = Ω/2 is well captured by those states when αc, g ≪ 1. Neighboring sites are then coupled by αc (green), g (purple), and αcg (blue), and consequently all eigenstates can become fully delocalized in the depicted two-dimensional Hilbert space. When k < Ω/2, a set of sites still shares the same onsite energy and is grouped by the same highlighting color in Fig. 4a. Therefore, here again the competition between the Wannier-Stark effect in the 2-dimensional synthetic lattice and the increasing quantum tunneling with site ∣n∣ takes place, which gives rise to a possible quantum dynamical phase transition in the atom-quantum PTC hybrid system. Note that for αc ≠ 0, g = 0, the energy spacing between states that differ by a total momentum quanta, \({\omega }_{CPTC}={E}_{m}^{\delta {n}_{k}=1}-{E}_{m}^{\delta {n}_{k}=0}\), departs from k as shown in Fig. 2b (lower panel), and the above choice of the excited atomic energy Δ = k does not make a resonant transition. See Supplementary Note 8 for the choice of resonant transition energy, Δ = ωCPTC.

a Schematic of the expanded Floquet-photonic lattice n combined with atomic states, indicated on the left end of each line. The Floquet index lF and the photon number state \(| {n}_{k},{n}_{-k}\rangle\) are marked within and next to each site, respectively. When the atomic energy is set to Δ = k, all onsite energies among the illustrated lattice sites coincide at k = Ω/2. At k ≠ Ω/2, sites with identical onsite energies are grouped together by color. Neighboring sites are coupled by αc (green dotted lines), g (blue dotted lines), and αcg (purple dotted lines). b At k ≪ kc−, both the excited-atomic-state population and the photonic energy oscillate coherently, akin to the conventional quantum Rabi model. In the lower panel, ∣ψt(n)∣2 on the lattice shown in (a) is plotted (log scale). The initial wave packet at t = 0 is prepared in \(| 0,0;0\rangle \otimes | e\rangle\), positioned at n = (0, 0). c At k/kc− = 0.9976, the initial atomic state \({\rho }_{at}(t=0)=| e\rangle \langle e|\) decays into the mixed state \({\rho }_{at}=\frac{1}{2}(| g\rangle \langle g|+| e\rangle \langle e| )\) because the wave packet spreads over many Floquet-photonic sites with a large localization length (ξ ≫ 1), where \({\rho }_{at}(t)=Tr[| {\psi }_{t}\rangle \langle {\psi }_{t}| ]\) and the trace is taken over the Floquet-photonic space. Nonetheless, the photonic energy retains its oscillatory behavior. d For \(k\in {{{{\mathcal{K}}}}}_{gap}\), the photonic energy diverges exponentially as the atomic state decays. The lower panel illustrates continuous propagation of the quantum states, showing no sign of localization. We set αc = 0.15 and g = 0.03 for all three simulations.

For k ≪ kc−, the eigenstates are well localized, and their coupling to atomic states results in conventional Rabi oscillations (Fig. 4b): the initial quantum state \(| 0,0;0\rangle \otimes | e\rangle\) hops back and forth between the nearest states \(| 1,0;0\rangle \otimes | g\rangle\) and \(| 0,1;0\rangle \otimes | g\rangle\) with an oscillation periodicity determined by the inverse of the light-atom coupling strength, \(1/g\sqrt{k}\). Near the edge kc− and within the momentum gap, their behavior deviates significantly. The spreading of an initially localized wave packet leads to irreversible changes in the atomic states, resulting in dissipation phenomena, as shown in Fig. 4c,d (upper panel) as the localization length ξ → ∞, despite the system being limited to \(| k\rangle\) and \(| -k\rangle\) photonic modes and a single atom. The initially excited atomic state, \({\rho }_{at}(t=0)=| e\rangle \langle e|\), exhibits underdamped oscillations before settling into the steady-mixed state reflecting dissipation caused by coupling to a number of Floquet-photonic states within a distance ξ from the origin n = 0 in the synthetic space, \({\rho }_{at}(t\to \infty )=\frac{1}{2}(| g\rangle \langle g|+| e\rangle \langle e| )\). Interestingly, the steady state that emerges is not the atomic ground state but a half-and-half mixed state (HHMS). This occurs because the eigenstates of the atom-quantum PTC hybrid system are delocalized along both the vertical and horizontal axes in Fig. 4a in the depicted Hilbert space where the atomic states \(| e\rangle\) and \(| g\rangle\) are equally populated. The decay rate from the initial state (either excited or ground) to the HHMS can be approximately determined using the Fermi-Golden Rule, provided that the coupling strength between the atom and the quantum PTC is much larger than the energy-level spacing between photonic states65. This condition is satisfied within the momentum gap when a large enough photonic and Floquet spaces (n → ∞) are considered. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the atomic states are entangled with the total momentum parity of the Floquet-photonic states: the excited atomic state is entangled with photonic states of even total momentum (∣δnk∣ = 0, 2, 4, ⋯ ), while the ground atomic state is entangled with photonic states of odd total momentum (∣δnk∣ = 1, 3, 5, ⋯ ). Therefore, measuring the atomic state simultaneously projects the Floquet-photonic states. These phenomena are unique to quantum PTCs and have no direct analogs in classical PTCs. Specifically, we propose that atomic-state dissipation, a distinct feature of quantum PTCs, can be systematically observed within the momentum gap as a function of coupling strength and permittivity modulation.

Discussion

Spontaneous emission of a photon, accompanied by the de-excitation of an atomic state, occurs when a continuum photonic spectrum is available. That is, the initial quantum state \(| {n}_{k}=0\rangle \otimes | e\rangle\) transitions to \(| {n}_{k}=1\rangle \otimes | g\rangle\) when ∣ℏck − Δ∣ ≲ g. The entropy associated with a single photon in free space is significantly greater than that of no photon. Consequently, spontaneous emission decay is an irreversible process that dissipates the energy of the excited atomic state. This energy is irretrievably transferred to the vast continuum of photonic modes. In the quantum PTC, a similar dissipative process occurs but is confined to single-frequency photonic modes with a time-periodic permittivity. Near the critical momentum and within the momentum gap, the large, effectively unbounded set of Floquet-photonic states acts as a continuum, allowing the atom to relax irreversibly into a mixed state. It is also worthwhile to note that because of the delocalization of eigenstates in the atomic-photonic two-dimensional domain (Fig. 4a), a transition to the mixed state can occur irrespective of the specific form of the initially prepared atomic state in \(| e\rangle\) or \(| g\rangle\). Namely, with energy transferred from the driven permittivity to photonic energy, another remarkable phenomenon arises in a nearly symmetric manner: a quantum state \(| {n}_{k}=0,{n}_{-k}=0\rangle \otimes | g\rangle\), initially prepared in the atomic ground state, undergoes irreversible excitation to the same mixed state (see Supplementary Note 7). Following the same steps described in the main text, we depict the Hilbert space relevant to the photonic vacuum and the ground atomic state in Supplementary Fig. 7b, c (lower panels) for two different choices of atomic energy. Crucially, there is no direct coupling by \({\widehat{H}}_{int}\) between the two Hilbert spaces associated with the quantum dynamics of \(| {\Phi }_{0}^{g}\rangle=| 0,0;0\rangle \otimes | g\rangle\) and \(| {\Phi }_{0}^{e}\rangle=| 0,0;0\rangle \otimes | e\rangle\). With no interference, for an arbitrary atomic initial state \({| \Phi \rangle }_{t=0}=\sqrt{r}| {\Phi }_{0}^{e}\rangle+\sqrt{1-r}| {\Phi }_{0}^{g}\rangle\), the time evolution of the atomic population is simply given by \({\widehat{\rho }}_{at}(t)=r{\widehat{\rho }}_{at}^{e}(t)+(1-r){\widehat{\rho }}_{at}^{g}(t)\), where \({\widehat{\rho }}_{at}^{e/g}(t)\) is independently obtained from the time evolution of \(| {\Phi }_{0}^{e/g}\rangle\) in the corresponding Hilbert space (see Supplementary Fig. 8).

In this work, we provide a comprehensive understanding of the classical PTC near the critical momentum and within the momentum gap, leveraging the framework of quantum electrodynamics. While our analysis has focused on weak coupling and a closed quantum system with a single atomic light emitter, future work could explore regimes where stronger coupling or multiple atoms introduce collective phenomena analogous to superradiance. Additional complexity may arise if the the system is allowed to exchange energy with an external reservoir—potentially stabilizing different steady states or enabling new non-equilibrium phase transitions. We anticipate that circuit QED platforms and rapidly tunable photonic cavities could offer practical testbeds, where time-domain engineering of the optical properties would systematically probe the momentum gap and measure the emerging half-and-half mixed atomic state.

Methods

Effective Hamiltonian in the Floquet-photonic synthetic lattice

When the energy quanta from the driving frequency of permittivity equals to the energy of two photons, ℏΩ = 2ℏck, the onsite potential energy of Floquet-Photonic synthetic space − lFℏΩ + (nk + n−k)ℏck = ( − 2lF + nk + n−k)ℏΩ/2. For example, the series of synthetic sites grouped in Fig. 1(c,d) shares the same potential energy and therefore no Wannier-Stark localization. At the same time the sites are coupled due to the time periodic coefficient of photon pair creation and annihilation term in Eq. (1), which generates off-diagonal terms in Floquet index, and it leads the delocalization of eigenstates within the grouped sites. The Floquet Hamiltonian elements are

and \({({\widehat{H}}_{F}^{e{{\mathrm{ff}}}})}_{{l}_{F},{l}_{F}-1}={({\widehat{H}}_{F}^{e{{\mathrm{ff}}}})}_{{l}_{F},{l}_{F}+1}\). There are collections of similarly coupled sites in (1, 1, 1)-direction in the Floquet-Photonic lattice (nk, n−k, lF) but at differently shared onsite potential energy. This is the basis for the construction of our effective Hamiltonian in Eq. (4), specifically for nk = n−k = lF = n case. As a result, the original 3-dimensional Hilbert space in (nk, n−k, lF) is reduced to the collection of 1-dimensional Hilbert spaces decoupled in energy and total momentum. When a two-level atom with energy spacing Δ is coupled to the quantum PTC, we again collect sites sharing the same onsite potential energy including the atomic states. Due to the light-matter interaction not conserve the total momentum of photonic states, the effective Hilbert space is extended to 2-dimension as described in Fig. 4a.

Diagonalization of time periodic Hamiltonian in the photon number space

The spectral properties of the quantum PTC in Fig. 2a–c are obtained from the diagonalization of effective Hamiltonian \({\widehat{H}}_{F}^{e{{\mathrm{ff}}}}\) in Eq. (4). The convergence of eigenvalues sharing the same total momentum as approaching to the critical momentum is verified from the effective Hamiltonian with the size of the synthetic space up to N = 10,000. The dynamical properties shown in Fig. 3 are from the eigenstates of \({\widehat{H}}_{F}^{e{{\mathrm{ff}}}}\) and their time evolution as explain in the main text. The Wigner-Dyson distribution observed in the momentum gap for the energy level spacing is computed from \({\widehat{U}}_{F}\) to take into account all eigenvalues within the quasi-energy domain. The Floquet unitary operator obtained from Eq. (1):

where Δt = T/M and tj = (j − 1)T/M. We take M = 1000, and the instantaneous Hamiltonian is represented in Photonic number space up to N = 4000.

Transfer matrix method in the Floquet-Photonic lattice

The Schrodinger equation in Eq. (4) can be expressed in a recursive form in terms of the amplitude ψ(n) = 〈n, n; n∣ψ〉 at site n:

where the relation holds for n≥0, since the photon number cannot be a negative integer. The relation is then cast as

The first matrix on the right-hand side is the transfer matrix that provides a relationship between consecutive quantum states in the Floquet-photonic space: Ψ(n) = TnΨ(n − 1), where Ψ(n) = [ψ(n+1), ψ(n)]T. In the large n limit, the transfer matrix becomes independent of site n and energy E, which crucially indicates that the momentum gap transition at k = kc± depends only on αc and Ω (see Supplementary Note 2 for nonzero total momentum case). This robustly defines the quantum momentum gap:

Its eigenvalues are \({\lambda }_{\pm }=\frac{Z\pm \sqrt{{Z}^{2}-4}}{2}\), where \(Z=\frac{2}{{\alpha }_{c}}(\frac{\Omega }{k}-2)\). The Lyapunov exponent in terms of the transfer matrix is expressed as:

where \(| \Psi (n)|=\sqrt{| \psi (n+1){| }^{2}+| \psi (n){| }^{2}}\). The Lyapunov exponent γ is positive nonzero for localized phase. It is zero for delocalized phase. The Lyapunov exponent is γ = 0 for Z2≤4, and for Z2≥4 (see Supplementary Note 2 for details)

The phase transition takes place at Z2 = 4, which provides the locations of critical momenta:

The localization length ξ is the inverse of the Lyapunov exponent γ. Specifically for k < kc− and k > kc+,

Within the momentum gap (kc− < k < kc+), eigenstates are delocalized (γ = 0) and they come with a momentum ϕ that characterizes the speed of phase rotation in the Floquet-Photonic synthetic lattice, ψ(n + 1) = eiϕψ(n), where in the n → ∞ limit (See Supplementary Note 2 for details)

This information is not captured in the Lyapunov exponent which takes the magnitude of wave function. As elaborated in the main text, the exponential growth rate of photon energy (or number) is analytically expressed in Eq. (9).

Data availability

This work is purely theoretical and produced no experimental or observational datasets. All numerical results can be reproduced from the equations and parameters provided in the manuscript and Supplementary Information. MATLAB/Python scripts used to generate the figures are available from the corresponding authors for non-commercial academic use.

References

Galiffi, E. et al. Photonics of time-varying media. Adv. Photonics 4, 014002 (2022).

Rizza, C. et al. Harnessing the natural resonances of time-varying dispersive interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133, 186902 (2024).

Lee, K. et al. Linear frequency conversion via sudden merging of meta-atoms in time-variant metasurfaces. Nat. Photonics 12, 765–773 (2018).

Solís, D. M., Kastner, R. & Engheta, N. Time-varying materials in the presence of dispersion: plane-wave propagation in a lorentzian medium with temporal discontinuity. Photon. Res. 9, 1842–1853 (2021).

Caloz, C. & Deck-Léger, Z.-L. Spacetime metamaterials–part ii: Theory and applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 68, 1583–1598 (2020).

Xiao, Y., Maywar, D. N. & Agrawal, G. P. Reflection and transmission of electromagnetic waves at a temporal boundary. Opt. Lett. 39, 574–577 (2014).

Chamanara, N., Deck-Léger, Z.-L., Caloz, C. & Kalluri, D. Unusual electromagnetic modes in space-time-modulated dispersion-engineered media. Phys. Rev. A 97, 063829 (2018).

Sounas, D. L. & Alù, A. Non-reciprocal photonics based on time modulation. Nat. Photonics 11, 774–783 (2017).

Tirole, R. et al. Double-slit time diffraction at optical frequencies. Nat. Phys. 19, 999–1002 (2023).

Galiffi, E., Huidobro, P. A. & Pendry, J. B. Broadband nonreciprocal amplification in luminal metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 206101 (2019).

Pendry, J. B., Galiffi, E. & Huidobro, P. A. Gain in time-dependent media—a new mechanism. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 38, 3360–3366 (2021).

Lyubarov, M. et al. Amplified emission and lasing in photonic time crystals. Science 377, 425–428 (2022).

Wang, N., Zhang, Z.-Q. & Chan, C. T. Photonic Floquet media with a complex time-periodic permittivity. Phys. Rev. B 98, 085142 (2018).

Park, J. et al. Revealing non-hermitian band structure of photonic Floquet media. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo6220 (2022).

Zurita-Sánchez, J. R., Halevi, P. & Cervantes-González, J. C. Reflection and transmission of a wave incident on a slab with a time-periodic dielectric function ϵ(t). Phys. Rev. A 79, 053821 (2009).

Martínez-Romero, J. S., Becerra-Fuentes, O. M. & Halevi, P. Temporal photonic crystals with modulations of both permittivity and permeability. Phys. Rev. A 93, 063813 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Metasurface-based realization of photonic time crystals. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg7541 (2023).

Park, J. et al. Spontaneous emission decay and excitation in photonic temporal crystals https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.13287 2404.13287 (2025).

Vázquez-Lozano, J. E. & Liberal, I. Incandescent temporal metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 14, 4606 (2023).

Asgari, M. M. et al. Theory and applications of photonic time crystals: a tutorial. Adv. Opt. Photon. 16, 958–1063 (2024).

Pacheco-Peña, V. & Engheta, N. Temporal aiming. Light.: Sci. Appl. 9, 129 (2020).

Yin, S., Galiffi, E. & Alù, A. Floquet metamaterials. eLight 2, 8 (2022).

Park, J. & Min, B. Spatiotemporal plane wave expansion method for arbitrary space–time periodic photonic media. Opt. Lett. 46, 484–487 (2021).

Lee, S. et al. Parametric oscillation of electromagnetic waves in momentum band gaps of a spatiotemporal crystal. Photon. Res. 9, 142–150 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Expanding momentum bandgaps in photonic time crystals through resonances. Nat. Photon. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-024-01563-3 (2024).

Miri, M.-A. & Alú, A. Exceptional points in optics and photonics. Science 363, eaar7709 (2019).

Wang, Y.-X. & Clerk, A. A. Non-hermitian dynamics without dissipation in quantum systems. Phys. Rev. A 99, 063834 (2019).

Shcherbakov, M. R. et al. Photon acceleration and tunable broadband harmonics generation in nonlinear time-dependent metasurfaces. Nat. Commun. 10, 1345 (2019).

Sustaeta-Osuna, J. E., Garcia-Vidal, F. J. & Huidobro, P. Quantum theory of photon pair creation in photonic time crystals. ACS Photon. 12, 1873–1880 (2025).

Mendonça, J. T., Guerreiro, A. & Martins, A. M. Quantum theory of time refraction. Phys. Rev. A 62, 033805 (2000).

Mendonça, J. T., Martins, A. M. & Guerreiro, A. Temporal beam splitter and temporal interference. Phys. Rev. A 68, 043801 (2003).

Mendonça, J. T. & Guerreiro, A. Time refraction and the quantum properties of vacuum. Phys. Rev. A 72, 063805 (2005).

Wilson, C. M. et al. Observation of the dynamical Casimir effect in a superconducting circuit. Nature 479, 376–379 (2011).

Román-Ancheyta, R., Ramos-Prieto, I., Perez-Leija, A., Busch, K. & León-Montiel, R.dJ. Dynamical Casimir effect in stochastic systems: Photon harvesting through noise. Phys. Rev. A 96, 032501 (2017).

Dodonov, V. Fifty years of the dynamical Casimir effect. Physics 2, 67–104 (2020).

Unruh, W. G. Notes on black-hole evaporation. Phys. Rev. D. 14, 870–892 (1976).

Alsing, P. M. & Milonni, P. W. Simplified derivation of the Hawking-Unruh temperature for an accelerated observer in vacuum. Am. J. Phys. 72, 1524–1529 (2004).

Nation, P. D., Johansson, J. R., Blencowe, M. P. & Nori, F. Colloquium: Stimulating uncertainty: Amplifying the quantum vacuum with superconducting circuits. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 1–24 (2012).

Eckel, S., Kumar, A., Jacobson, T., Spielman, I. B. & Campbell, G. K. A rapidly expanding Bose-Einstein condensate: An expanding universe in the lab. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021021 (2018).

Good, M. R. R., Linder, E. V. & Wilczek, F. Moving mirror model for quasithermal radiation fields. Phys. Rev. D. 101, 025012 (2020).

Horsley, S. A. R. & Pendry, J. B. Quantum electrodynamics of time-varying gratings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 120, e2302652120 (2023).

Pendry, J. B. & Horsley, S. A. R. Qed in space-time varying materials. APL Quantum 1, 020901 (2024).

Wannier, G. H. Wave functions and effective Hamiltonian for Bloch electrons in an electric field. Phys. Rev. 117, 432–439 (1960).

Emin, D. & Hart, C. F. Existence of Wannier-Stark localization. Phys. Rev. B 36, 7353–7359 (1987).

Avron, J. E., Exner, P. & Last, Y. Periodic schrödinger operators with large gaps and Wannier-Stark ladders. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 896–899 (1994).

Wilkinson, S. R., Bharucha, C. F., Madison, K. W., Niu, Q. & Raizen, M. G. Observation of atomic Wannier-Stark ladders in an accelerating optical potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 4512–4515 (1996).

Glück, M., R. Kolovsky, A. & Korsch, H. J. Wannier-Stark resonances in optical and semiconductor superlattices. Phys. Rep. 366, 103–182 (2002).

Ishii, K. Localization of eigenstates and transport phenomena in the one-dimensional disordered system. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 53, 77–138 (1973).

MacKinnon, A. & Kramer, B. The scaling theory of electrons in disordered solids: Additional numerical results. Z. f.ür. Phys. B Condens. Matter 53, 1–13 (1983).

Pichard, J. L. & Sarma, G. Finite size scaling approach to Anderson localisation. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 14, L127 (1981).

Slevin, K. & Ohtsuki, T. Critical exponent for the quantum hall transition. Phys. Rev. B 80, 041304 (2009).

Dwivedi, V. & Chua, V. Of bulk and boundaries: Generalized transfer matrices for tight-binding models. Phys. Rev. B 93, 134304 (2016).

Luo, X., Ohtsuki, T. & Shindou, R. Transfer matrix study of the Anderson transition in non-Hermitian systems. Phys. Rev. B 104, 104203 (2021).

Zhang, Y.-C. & Zhang, Y.-Y. Lyapunov exponent, mobility edges, and critical region in the generalized aubry-andré model with an unbounded quasiperiodic potential. Phys. Rev. B 105, 174206 (2022).

Xiao, Z., Kawabata, K., Luo, X., Ohtsuki, T. & Shindou, R. Anisotropic topological Anderson transitions in chiral symmetry classes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 056301 (2023).

Wigner, E. P. Characteristic vectors of bordered matrices with infinite dimensions. Ann. Math. 62, 548–564 (1955).

Mehta, M. L. Random matrices (Elsevier, 2004).

Kim, K. W., Lee, W.-R., Kim, Y. B. & Park, K. Surface to bulk fermi arcs via weyl nodes as topological defects. Nat. Commun. 7, 13489 (2016).

Kim, K. W., Andreanov, A. & Flach, S. Anomalous transport in a topological Wannier-Stark ladder. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023067 (2020).

Romualdo, I., Hackl, L. & Yokomizo, N. Entanglement production in the dynamical Casimir effect at parametric resonance. Phys. Rev. D. 100, 065022 (2019).

Rabi, I. I. On the process of space quantization. Phys. Rev. 49, 324–328 (1936).

Braak, D. Integrability of the Rabi model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 100401 (2011).

Xie, Q., Zhong, H., Batchelor, M. T. & Lee, C. The quantum Rabi model: solution and dynamics. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 50, 113001 (2017).

Milonni, P. W.An introduction to quantum optics and quantum fluctuations (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Micklitz, T., Morningstar, A., Altland, A. & Huse, D. A. Emergence of Fermi’s golden rule. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 140402 (2022).

Acknowledgements

J.H.B. and K.W.K. acknowledge financial support from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (no. RS-2025-00521598) and the Korean Government (MSIT) (no. 2020R1A5A1016518). K.L. and B.M. are supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) through the government of Korea (NRF-2022R1A2C301335313) and the Samsung Science and Technology Foundation (SSTF-BA2402-02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H.B. and K.L. contributed equally. J.H.B. performed analytical derivations and numerical calculations and prepared figures; K.L. performed numerical calculations and prepared figures. K.W.K. developed the theoretical framework; K.W.K. and B.M. conceived and supervised the project, provided theoretical guidance, verified derivations, and refined the presentation. All authors contributed to writing and editing and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bae, J., Lee, K., Min, B. et al. Quantum electrodynamics of photonic time crystals. Nat Commun 17, 858 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67572-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67572-0