Abstract

Chemical dopants-induced phase boundary engineering has boosted electrical properties of (K, Na)NbO3-based piezoceramics, yet the underlying mechanisms governing these improvements remain unclear. Here, we elucidate these mechanisms through comprehensive multi-scale structural analysis (atomic-to-nanoscale-to-mesoscale) on two representative solid-solutions, namely (K, Na, Li)NbO3 and (K, Na)NbO3-(Bi0.5Na0.5)ZrO3. By utilizing neutron pair distribution function analysis, scanning transmission electron microscope, first-principle calculations, and phase-field simulations, our results reveal distinct atomic-scale mechanism underlying phase boundary engineering. In (K, Na, Li)NbO3, convergent off-center displacements of Li atoms induce an interplay between displacive and order-disorder phase transition; while in (K, Na)NbO3-(Bi0.5Na0.5)ZrO3, divergent off-center displacements of Bi atoms trigger a predominant order-disorder type phase transition. These atomic-scale structural characteristics directly correlate with mesoscopic ferroelectric domains and ultimately determine macroscopic electrical properties. This work elucidates the role of chemical dopants in phase boundary engineering from a multi-scale perspective, establishing a framework for designing lead-free piezoceramics with enhanced electrical properties and advancing the development of eco-friendly piezoceramics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Piezoceramics, well-known for their ability to interconvert electrical and mechanical energies, serve as indispensable functional components in a variety of electronic devices, such as sensors, actuators, and transducers1. Historically, lead(Pb)-based piezoceramics, predominantly the lead zirconate titanate {Pb(Zr, Ti)O3, PZT} family, have dominated the market2. However, the widespread use of Pb-based commercial piezoceramics raises significant environmental and health concerns due to the toxicity of Pb3. In response to this challenge, substantial efforts have been made to develop eco-friendly Pb-free alternatives, among which potassium sodium niobate {(K, Na)NbO3, KNN} based ceramics stand out due to their excellent piezoelectric properties4.

The documented high piezoelectric properties of KNN-based ceramics are intimately related to the phase boundary engineering (PBE), a strategy that regulates the phase transition temperature, notably the orthorhombic/monoclinic-tetragonal phase transition temperature (TO/M-T) to occur near room temperature5. This modulation is typically achieved through the addition of dopants, such as lithium (Li) or (Bi0.5M0.5)NO3 (M = Na, K; N = Zr, Hf) dopants6. Recent crystallographic studies, including our work, indicate that the monoclinic (M) phase better describes KNN ceramics than the traditional orthorhombic (O) phase7,8,9, therefore we consistently refer to this structural feature as the M phase hereafter.

Several physical mechanisms have been proposed to interpret the enhanced performance induced by PBE, including the multi-phase coexistence10,11, nano-sized ferroelectric domains12, and electric-induced phase transitions13,14. It is well established that chemical dopants directly influence atomic displacements and octahedral tilting/rotation in individual unit cells, which subsequently induces nano-sized domains or phase transition. However, these proposed mechanisms primarily account for enhancements at the meso-/macroscopic scale, falling to provide comprehensive explanations at the atomic scale. This knowledge gap stems from limited investigations into local atomic structures, particularly evident in KNN-based solid-solutions, exhibiting similar M-T phase boundaries but distinct electrical properties (as exemplified in Fig. 1). Consequently, the development of high-performance KNN-based ceramics remains largely empirical and relies heavily on trial-and-error approaches. Deciphering how different chemical dopants affect local atomic structures is therefore crucial for deeper understanding the fundamental mechanisms of PBE formation and for explaining the observed differences in electrical properties induced by chemical modifications.

a, b Lab XRD patterns with 2θ = 44–47°. The XRD patterns are indexed according to the pseudo-cubic phase. c–e Temperature-dependent real part permittivity curves, measured at 200 kHz. The solid and dashed lines are measured from unpoled (ε′) and poled (\({\varepsilon }_{33}^{{\prime} }\)) samples. f–h PFM amplitude images with a scanning area of 5 μm × 5 μm. i, j P–E loops and S–E curves measured from unpoled samples. k εr, Pr, and d33 values of KNN, KNN-0.06Li, and KNN-0.06BNZ. Although KNN-0.045BNZ exhibits better ferroelectric and strain properties than those of KNN-0.06BNZ, its lower room-temperature εr results in its relatively lower d33 (Fig. S11), further proving the importance of high εr. Thus, we chose KNN-0.06BNZ to perform the neutron total scattering because of its highest room-temperature εr.

In this work, we conduct a comprehensive multi-scale structural analysis, with particular emphasis on local atomic scale, to explain the role of chemical dopants towards construction of the phase boundaries in KNN-based ceramics. Our approach integrates neutron total scattering, scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), first-principles calculations, and phase-field simulations, in providing a detailed examination on two representative solid-solution systems: (1−x)(K0.48Na0.52)NbO3−xLiNbO3 and (1−y)(K0.48Na0.52)NbO3−y(Bi0.5Na0.5)ZrO3 (abbreviated as KNN-xLi and KNN-yBNZ, respectively). Through this multi-technique investigation, we elucidate the distinctive role of Li and BNZ in constructing the M-T phase boundary and demonstrate how these specific dopants contribute to the observed variations in electrical properties.

Results

Structure and electrical properties at the meso-/macroscopic scale

We first compare two KNN-based ceramics with similar M-T phase boundaries but distinct electrical properties: KNN-xLi and KNN-yBNZ systems. The chemical composition analysis reveals the elemental ratio close to the nominal value, and Li occupies the A-site in KNN-xLi ceramics (Figs. S1–S3). X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns reveal a transition in the long-range crystal symmetry from an M (monoclinic) to T (tetragonal) phase structure in both solid-solution systems with increasing dopant content, evidenced by a clear shift in the intensity ratio between (002) and (200) peaks from 2:1 to 1:2 (Fig. 1a, b and Fig. S4). Temperature-dependent dielectric properties further show a decrease in the TM-T with increasing Li and BNZ content (Fig. 1c–e and Figs. S5–S6). Despite these structural similarities, significant differences emerge in their dielectric behaviors. KNN-0.06Li shows a sharp dielectric anomaly with low permittivity (i.e., ε′ for unpoled or \({\varepsilon }_{33}^{{\prime} }\) for poled) of 500–700 at TM-T, whereas KNN-0.06BNZ demonstrates a diffused dielectric anomaly with a higher ε′ (or \({\varepsilon }_{33}^{{\prime} }\)) of 1200–1500. This distinction extends to domain morphologies as revealed by piezoelectric force microscopy (PFM). While pristine KNN ceramics exhibit regular striped domains averaging ~0.5 μm in width and ~3.5 μm in length (Fig. 1f), KNN-0.06Li ceramics show sub-micron-sized striped domains (e.g., 0.4–0.8 μm in width) overlapped with irregular watermark-shaped domains (Fig. 1g). KNN-0.06BNZ exhibits, however, distinctly irregular and fragmented domains with sizes of 0.3–0.6 μm (Fig. 1h). Additional PFM results and related analysis are shown in Figs. S7–S10.

Ferroelectric hysteresis (P–E) loops and electric-induced strain (S–E) curves further differentiate these two systems. Li doping shows minimal improvement in polarization and strain properties, and causes a decline at higher concentrations (e.g., x ≥ 0.07) (Fig. 1i, j and Fig. S11). Conversely, an optimal BNZ content (e.g., y = 0.045) significantly improves the polarization and strain properties, though excessive BNZ deteriorates performance. The piezoelectric coefficient (d33), which is proportional to the product of relative dielectric permittivity (εr) and remanent polarization (Pr), increases by a factor of ~3.6 in KNN-0.06BNZ and ~2 in KNN-0.06Li compared to pristine KNN (Fig. 1k and Fig. S11). Thus, d33 enhancement of both systems depends on εr rather than Pr because they show lower Pr values than that of pristine KNN ceramics.

Several critical questions arise regarding the observed differences in electrical properties and domain morphologies between KNN-0.06Li and KNN-0.06BNZ, despite their similar M-T phase boundaries. First, why does KNN-0.06BNZ exhibit a room-temperature εr approximately twice as high as that of KNN-0.06Li? εr is determined by both intrinsic (e.g., crystal structure) and extrinsic factors (e.g., grain size and domains). Both systems share the similar M-T phase coexistence and comparable domain sizes (Figs. S7 and S8), suggesting these factors alone cannot explain the disparity. Furthermore, the larger grain size of KNN-0.06Li (Fig. S12), which typically enhances εr15, corresponds instead to a lower value, indicating additional mechanisms are involved. Second, why do two systems show different trends of Curie temperature (TC) and diffusion factor varying with composition (Fig. S13)? BNZ doping makes the dielectric anomaly at TM-T dispersive and decreases TC, whereas the opposite situations occur with Li doping. TC is directly proportional to the spontaneous polarization (PS)16. While Pb-/Bi-doped ceramics achieve higher PS through strong hybridization of Pb–O and Bi–O bonds17, Li–O bonds exhibit weak hybridization18. Third, why does KNN-0.06BNZ exhibit more fragmented domains compared to KNN-0.06Li? (Figs. S7 and S8). This is likely related to the heterovalent ionic substitutions of BNZ that introduces local heterogeneities in KNN ceramic matrix19. These questions hint at the fact that Li and BNZ additions affect the local atomic structures near the M-T phase boundary in fundamentally different ways. Therefore, we conduct a multi-scale structural analysis, with a particular focus on local atomic structures, to clarify these mechanisms.

Neutron total scattering analysis

To quantitatively characterize the M-T phase transition behavior, Rietveld refinements are performed on neutron Bragg diffraction patterns to analyze structural parameters, including unit cell constants, atomic coordinates, and atomic displacement parameters (ADPs) (Figs. S14–S17)20. These refinements indicate a structural transition from an M phase in KNN to a coexistence of M and T phases in KNN-0.06Li and KNN-0.06BNZ (Fig. 2a, Figs. S15 and S16). Despite this shared M-T phase coexistence, notable differences emerge between the two systems (Tables S1–S3). KNN-0.06Li exhibits an approximately equal M-to-T phase ratio, with the T phase characterized by a large tetragonality (i.e., c/a = 1.016). Conversely, KNN-0.06BNZ exhibits a dominant T phase with smaller tetragonality (i.e., c/a = 1.009). Additionally, the lattice parameter (a, b, and c) differences in the M phase are more pronounced in KNN-0.06Li but significantly reduced in the KNN-0.06BNZ. Lower degrees of non-cubic lattice distortion, typically facilitating polarization rotation and domain switching under applied electric fields, imply that KNN-0.06BNZ requires lower exciting voltage for domain switching. This is consistent with the lower coercive field (EC) and local coercive voltage (VC) for KNN-0.06BNZ, as observed in P–E loops and litho-PFM measurements, respectively (Fig. 1i and Figs. S9–S11).

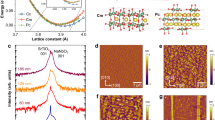

a Neutron diffraction patterns of KNN-0.06BNZ, measured at BANK5 of the NOMAD instrument. b Experimental PDF within one unit cell ~4 Å, showing the nearest neighbor pairwise atom correlations. Peaks representing B–O, A–O/O–O, and A–B interatomic correlations are marked with arrows. The two shoulders at 2.5 and 3.2 Å are due to the A–O atomic bond. c Experimental and fitted G(r) profiles of KNN-0.06BNZ for interatomic distance r ~ 1–10 Å, incorporating individual atomic positions and anisotropic displacement parameters. d Fitting results of PDF and S(Q) data for KNN-0.06BNZ, obtained by the RMC modeling. Stereographic projections (left column) of the atomic polar displacement vectors along the [001] direction for e Bi and f Li atoms, and corresponding directional displacement (right column). Corresponding 2D probability distribution of g Bi and h Li atoms in KNN-0.06BNZ and KNN-0.06Li, respectively. The index of stereographic projection of (e, f) is referred to Fig. S22a.

The ADPs further suggest increased local atomic disorder in transitioned T phase, reflected by higher equivalent isotropic displacement parameter (Uiso) values for oxygen (Tables S1–S3). This local disorder likely contributes to the M-T phase transition, which is further explored through neutron pair distribution function (PDF). PDF results reveal splitting B–O atomic correlations at 1.9 and 2.1 Å and triplet subpeaks for A–O atomic correlation, indicative of B-site off-center displacement and diverse A–O bonds (Fig. 2b). Despite the long-range M-to-T phase transition in KNN-0.06Li and KNN-0.06BNZ, Rietveld-like refinements on the PDF indicate that the short-range structural symmetry of the M persists in both ceramics (Fig. 2c and Fig. S17). Note that the local structure model with separate treatment of A/B-site atoms and anisotropic displacement parameters could better reproduce the experimental PDF data (Fig. S18). Big-box modeling using reverse Monte Carlo (RMC) further reveals the off-center displacement of specific elements, particularly for Bi and Li atoms (Fig. 2d–f and Figs. S19–S21). Intriguingly, these dopants exhibit fundamentally different displacement behaviors.

The off-center displacements of Bi atoms exhibit multi-directional characteristics, spanning cross [110], [100], and \([1\bar{1}0]\) directions, aligning with the spontaneous polarization directions of the M and T phases (Fig. 2e, g). In the KNN system, the spontaneous polarization directions of M and O phases are nearly identical due to the negligible difference between the monoclinic Pm phase and the primary perovskite unit cell orthorhombic Amm2 (see Table S4). Given the high degree of divergence in these off-center displacements, we term this behavior as divergent displacement. In contrast, the off-center displacements of Li atoms are predominantly along [100] and \([\bar{1}00]\) directions (i.e., the spontaneous polarization directions of T phase) and are much more focused than those of Bi atoms (Fig. 2f, h). Thus, we characterize the Li atomic displacements as convergent displacement. Such divergent and convergent displacements of dopants have not been experimentally reported earlier for KNN-based solid-solutions. The RMC analysis also reveal distinct off-center displacements of Nb atoms in KNN-0.06Li and KNN-0.06BNZ, suggesting retained spontaneous polarization from B-site ions (Figs. S20 and S21), consistent with their measured P–E loops (Fig. 1i, j). Besides, Na atoms also show pronounced off-center displacement, whereas K atoms exhibit weaker displacement likely due to the smaller ion radius of Na+ than K+, analogous to previous results21,22,23. Note that the displacement of Zr atoms is similar to that of Nb atoms, which contrasts with the distinct distributions of Bi, and K/Na (Fig. S21), indicating that the phase transition in KNN-yBNZ is mainly attributed to Bi atoms.

We next evaluate the statistical distribution of A-site and B-site atoms for better explaining the underlying physical mechanisms governing phase transitions in these three KNN solid-solution compositions24. Atomic correlation analysis reveals directional displacement of A-site and B-site atoms relative to their surrounding oxygen atoms, visualized as stereographic projections viewed along the [001] axis (Fig. 3 and Fig. S22). In KNN, B-site atomic displacements predominantly formed a triangular region within \(\left[\bar{1}\bar{1}1\right]\), \(\left[\bar{1}11\right]\), and [001] directions, statistically aligning with the \(\left[\bar{1}01\right]\) direction, characteristic of the M phase symmetry (Fig. 3a). KNN-0.06Li exhibits a distinct pattern, with B-site atoms shifting primarily between the [001] and \(\left[\bar{1}01\right]\) direction, inducing a displacive phase transition from M to the T phase (Fig. 3b). Conversely, KNN-0.06BNZ exhibits significant B-site disorder, with displacements distributed along multiple directions (i.e., \(\left[\bar{1}\bar{1}1\right]\), \(\left[\bar{1}11\right]\), \(\left[1\bar{1}1\right]\), and [111] directions), which averages out to yield a net T phase (i.e., a statistically [001] direction). This pattern reflects an order-disorder transition, culminating in a T phase (Fig. 3c). A-site atomic displacements also exhibit composition-dependent variations. In KNN, A-site atoms displaced predominately along the \(\left[\bar{1}\bar{1}0\right]\) direction (Fig. 3d); while in KNN-0.06Li, these displacements become more disordered, spanning an orientation space between \(\left[\bar{1}\bar{1}0\right]\) and \(\left[\bar{1}10\right]\) directions, facilitating an M-to-T transition with a net \(\left[\bar{1}00\right]\) displacement direction (Fig. 3e). KNN-0.06BNZ demonstrates even greater A-site atoms disorder, with displacement across four directions (i.e., \(\left[\bar{1}\bar{1}0\right]\), \(\left[\bar{1}10\right]\), \(\left[1\bar{1}0\right]\) and [110]), averaging out to a net zero displacement and generating a T phase featured with a low tetragonality (i.e., c/a ~ 1.009) (Fig. 3f).

Projected distribution statistics of a–c B-site and d–f A-site ions in KNN, KNN-0.06Li, and KNN-0.06BNZ. The arrow indicates the atomic displacement in the local structure, and hand-marked arrow indicates the atomic displacement in the average structure. The corresponding 2-D view is shown in Fig. S22.

These results reveal fundamentally different mechanisms driving the M-to-T phase transition in two doped systems. KNN-0.06Li experiences a phase transition driven by a combination of B-site displacive and A-site order-disorder transitions. By contrast, KNN-0.06BNZ undergoes a predominant order-disorder phase transition characterized by increased atomic displacements disorder in both AO12 and BO6 polyhedron. The interplay between displacive and order-disorder transitions, governed by the cooperative behavior of A-site and B-site atoms within their polyhedral, determines the average phase structures. These atomic structural changes directly influence mesoscopic ferroelectric domains and ultimately affect the macroscopic electrical properties.

TEM/STEM analysis

We then analyze the local structure using the TEM/STEM techniques. Analogous to the foregoing PFM measurements, TEM images reveal different ferroelectric domains in two doped systems. Specifically, KNN-0.06Li exhibits abundant stripe and herringbone domains (with a size ranging from tens to hundreds of nanometers) (Fig. 4a and Fig. S23). In contrast, KNN-0.06BNZ shows nano-sized domains (whose domain walls are not situated in specific crystal planes) or even undetectable domains, indicative of disrupted long-range ferroelectric order (Fig. 4d and Fig. S23). To further explore the atomic-scale structure, we measure high-angle annular dark field (HAADF) images and calculate the polarization magnitudes and angles (Fig. 4 and Fig. S24). The projected polarization angle mappings along the [100] direction revealed that both KNN-0.06Li and KNN-0.06BNZ possess the coexisting M(/R) and T phases (Fig. 4b, e, g, i), coinciding with the neutron diffraction results. Quantitative analysis revealed average polarization magnitudes of 19.0 pm for KNN-0.06Li and 13.6 pm for KNN-0.06BNZ (Fig. 4c, f, h, j). The higher polarization amplitude in KNN-0.06Li manifests the larger off-center displacement of both A- and B-site atoms. These STEM-HAADF findings are consistent with our PDF analysis results, providing complementary evidence at the atomic scale and reinforcing our understanding of the structural mechanisms underlying their ferroelectric behaviors.

Domain morphologies and [100]-oriented STEM-HAADF images with projected polarization magnitude/angle mapping of a–c KNN-0.06Li and d–f KNN-0.06BNZ. The statistic histogram of calculated polarization magnitude/angle distribution of g, h KNN-0.06Li and i, j KNN-0.06BNZ. In the polarization angle mapping, as shown in the inset of (g), the \([00\bar{1}]\) direction is set to be 0°, and \([0\bar{1}\bar{1}]\) and \([01\bar{1}]\) directions correspond to −45° and 45°, respectively.

Theoretical analysis

We then rationalize foregoing experimental observations by using the first-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) and phase-field simulations. Due to the similar off-center displacements of Nb and Zr atoms, only the effect of Bi on the crystal structure of KNN is considered. Regardless of whether the matrix symmetry adopts monoclinic Pm or tetragonal P4mm phase configuration, the relaxed supercells consistently reveal a more significant off-center displacement of Li atoms compared to Bi atoms (Fig. 5a–c, Figs. S25 and S26). Compared with pristine KNN supercells, Li atoms significantly increase the disparity in Nb–O bond lengths within the nearest neighboring NbO6 octahedra, while Bi atoms markedly reduce these disparities (Fig. 5d and Fig. S26d). Thus, Li atoms disrupt the short-range order of Nb atoms but retain a displacement of the long-range order of Nb atoms along other directions (e.g., [001] direction); conversely, Bi atoms disrupt both the short-range and long-range order of Nb atoms, consistent with the atomic displacement distributions observed in our PDF analysis. The intensified Nb–O bond length difference in KNN-Li indicates the higher bond strength of Nb–O bonds, whereas the reduced difference in KNN-Bi corresponds to the lower bond strength, well coinciding with the analysis of Raman spectra (Fig. S27). Furthermore, compared with KNN supercells, the calculated density of states (DOS) profile and charge density reveal the negligible hybridization between Li and O atoms in KNN-Li supercells, while the weakened hybridization between Nb and O atoms and the distinct hybridization between Bi and O atoms are observed in KNN-Bi supercells (Fig. 5e–g and Fig. S28). These findings indicate that the off-center displacement of Li atoms arises entirely from its smaller ionic radius relative to K/Na atoms, whereas the displacement of Bi atoms results from a synergistic effect of its small ionic radius and Bi–O hybridization.

a–c Relaxed crystal structure of KNN, KNN-Li, and KNN-Bi supercells by setting the matrix symmetry as monoclinic Pm phase; d Nb–O bond length of KNN supercells, and Nb–O bond length nearest to Li and Bi atoms of KNN-Li and KNN-Bi supercells; e–g calculated charge density of KNN, KNN-Li, and KNN-Bi supercells; h phase-field simulated domains of KNN, KNN-Li, and KNN-BNZ samples with and without applied electric field; i corresponding Landau energy profiles.

To further elucidate the role of mesoscopic domains in enhancing piezoelectricity, we conduct phase-field simulations. In the initial state (i.e., E = 0), all three samples show domain configurations analogous to the results of PFM and TEM measurements (Fig. 5h). Under the maximum electric field (i.e., E = Emax), both KNN and KNN-Li show partial domain switching, while KNN-BNZ demonstrates a predominant domain switching, consistent with the litho-PFM results (Fig. S9). The corresponding Landau energy profiles show the most flattened landscape for KNN-BNZ, whereas the deepest one observed for KNN-Li (Fig. 5i). The flattened landscape of KNN-BNZ indicates easier polarization rotation and higher dielectric response, accounting for its higher d33 values. Moreover, the phase-field simulations well reproduce the experimental ferroelectric and strain properties (Fig. S29), proving the reliability of this theoretical calculation.

Discussion

The foregoing multi-scale structural analysis, particularly at the atomic level, unambiguously reveals two distinct mechanisms for constructing the M-T phase boundary in KNN-based ceramics: a combined displacive and order-disorder model in KNN-0.06Li and a predominant order-disorder model in KNN-0.06BNZ. The divergent off-center displacement of Bi atoms increases disorder on both local and long-range scales, while the convergent off-center displacement of Li atoms only increases local disorder but retains long-range order. This fundamental difference in atomic behavior produces cascading effects across multiple length scales. The enhanced local disorder at both A and B sites in KNN-0.06BNZ results in a flattened Landau energy profile, fragmented nano-domains, and a predominant T phase featured with low tetragonality. These features synergistically boost the dielectric response and enhance the piezoelectricity. In contrast, disorder in KNN-0.06Li is primarily confined to the A-site, accounting for the limited enhancement in dielectric response and piezoelectricity (relative to KNN-0.06BNZ) even though the construction of M-T phase boundary. Moreover, the large tetragonality of KNN-0.06Li severely impedes the domain switching, resulting in lower maximum polarization (Pmax) and high EC (Fig. S11).

Interestingly, the off-displacements of Bi and Li atoms persist even at cryogenic conditions. When heating from −260 to 0 °C, KNN-0.06BNZ shows a significant increase in ε′ but no the dielectric anomalies observed in KNN and KNN-0.06Li. This increase is accompanied by much higher ε" (and tan δ) and strongly frequency-dependent tan δ (Fig. S30). The temperature-dependent synchrotron XRD patterns show no significant phase transitions (Fig. S31), indicating that the phase-transition-unrelated anomaly in tan δ likely stems from energy dissipation caused by the switching of nanoscale polar regions25. These nanoscale polar regions originate from disrupted long-range order caused by the off-center displacement of Bi atoms. Noting that neither KNN-0.06Li nor KNN-0.06BNZ transitions into a single M or R phase even at −150 °C, confirming the stability of the off-center displacements of Bi and Li atoms. As temperature rises, the divergent off-center displacement of Bi atoms and associated nanoscale polar regions become active, significantly promoting the mobility of surrounding domains and thereby contributing to the elevated dielectric response.

This atomic-scale structure analysis may provide a unifying framework that integrates other physical models, especially the electric-induced phase transition and high-density nano-regions with low-angle polar vectors proposed in the high-performance KNN-based ceramics containing Bi atoms13,26. First, the highly directional displacement of Bi atoms and the reduced lattice distortion (e.g., low tetragonality c/a ~ 1.009) enable rapid atom re-arrangements under electric fields27, thus generating the electric-induced phase transition. Second, the divergent off-center displacement of Bi atoms not only induces the dominant T phase with low tetragonality but also brings in local structural heterogeneities. The T phase with a low tetragonality substantially reduces the polarization anisotropy, enabling easier polarization rotate and promoting the formation of high-density nano-regions with low-angle polar vectors28. These nano-regions exhibit the interfacial energies similar to the Landau energy of the matrix and consequently further promote the polarization rotation and domain switching as “seeds”26,29, ultimately boosting the dielectric response and piezoelectricity. Thus, our findings suggest that more attention should be directed towards locally structural design rather than solely focusing on shifting phase transition temperatures when aiming to enhance the electrical properties of KNN-based ceramics in future endeavors.

Finally, we emphasize the differences between our work and existing studies. While previous research has reported off-center displacement of Bi3+ ions, these studies primarily focused on the host ions in systems without the room-temperature phase boundary30. Our work decodes how specific doping ions (i.e., Bi3+ and Li+) construct the M-T phase boundary in KNN system and their influence on mesoscopic ferroelectric domains and macroscopic piezoelectric properties. Our work not only identifies the off-centering displacements of Bi3+ and Li+ ions as the fundamental origin of the M-T phase boundary formation, but also reveals that their distinct displacement behaviors lead to different phase boundary construction processes and consequently markedly different domains and electrical properties. To our knowledge, such mechanistic insight has not been previously reported.

In addition, the proposed physical mechanism may extend beyond KNN to BaTiO3 (BTO) ceramic system. Specifically, even though the decreased TO-T after doping Li+ and Bi3+ ions in BTO ceramics, doping Li+ ions showed the unchanged (or slightly increased) TC and the enhanced tetragonality (c/a) [analogous to the situation of KNN-xLi]31,32, while doping Bi3+ ions significantly sacrificed both TC and tetragonality (c/a) and fragmented the ferroelectric domains [analogous to the situation of KNN-yBNZ]33,34. This consistency across different ABO3 perovskites valid our proposed model as a potentially universal principle governing dopant-induced property control in ferroelectric ceramics.

In summary, we decipher the multi-scale structure (especially at the atomic level) of two KNN-based solid-solutions with the M-T phase boundary, achieved through distinct chemical dopants (Li and BNZ). Despite similar M-T phase boundary construction, a synergetic displacive and order-disorder model characterizes KNN-0.06Li, whereas a predominant order-disorder model distinguishes KNN-0.06BNZ. The divergent off-center displacement of Bi atoms increases disorder on both local and long-range scales, while the convergent off-center displacement of Li atoms only increases local disorder but retains long-range order, which is responsible for the observed difference in mesoscopic domains and macroscopic electrical properties. Our findings not only reveal two physical models for constructing M-T phase boundary in KNN-based ceramics, but also provide meaningful insight into the design of lead-free piezoceramics with enhanced electrical properties.

Methods

Materials design and synthesis

(1−x)(K0.48Na0.52)NbO3−xLiNbO3 and (1−y)(K0.48Na0.52)NbO3−y(Bi0.5Na0.5)ZrO3 ceramics (abbreviated as KNN-xLi and KNN-yBNZ, respectively; x = 0, 0.06, 0.07, and 0.075; y = 0, 0.045, 0.06, and 0.08) were prepared by the conventional solid-state sintering method. Here, (1−x)(K0.48Na0.52)NbO3−xLiNbO3 can be written as (K0.48Na0.52)1−xLixNbO3. That is to say, Li atoms designedly doped into the A-site, analogous to the situation of (K0.95Li0.05)NbO3 and (Ba1−xLix)TiO3−x/2 ceramics35,36. The subsequent ICP-OES, TOF-SIMS, and XPS results also demonstrate that Li atoms occupy the A-site instead of the B-site (Figs. S1–S3). For (1−y)(K0.48Na0.52)NbO3−y(Bi0.5Na0.5)ZrO3 ceramics, the chemical formula can be written as (A1−0.5yBi0.5y)(Nb−Zry)O3 (A = K/Na). Therefore, Bi and Zr atoms replace the A-site and B-site atoms and generate the A-site vacancies and oxygen vacancies simultaneously in the following equation26:

Obviously, the concomitant A-site vacancies and oxygen vacancies occur to remain the charge neutrality overall in KNN-yBNZ ceramics.

K2CO3 (99%), Na2CO3 (99.8%), Nb2O5 (99.95%), Li2CO3 (99%), Bi2O3 (99.999%), ZrO2 (99%), and Fe2O3 (99%) (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) were selected as raw materials. 0.2 mol% Fe2O3 was introduced to promote the sintering of KNN-yBNZ ceramics. A small amount of Fe2O3 mainly acted as a sintering aid and minimal impact on the phase transition temperature37, as evidenced by the fact that our KNN-yBNZ ceramics showed very similar change tendency in phase transition temperature evolution compared with other KNN-BNZ ceramics reported in literature (Fig. S32)38. Moreover, our KNN-yBNZ ceramics showed comparable d33 values but lower Ts, relative to other KNN-BNZ ceramics38,39. These results confirmed that the Fe2O3 addition did not alter the fundamental physical mechanism discussed in this work. While no sintering aid was needed for KNN-xLi ceramics (x = 0.06, 0.07, and 0.075) as Li can reduce the sintering temperature and promote sintering process. After being weighed based on the standard stoichiometric ratio, the powders were ball-milled in the plastic jar for 24 h by the aids of the anhydrous ethanol and zirconia ball media. The dried slurry was calcined at 850 °C for 6 h, and then it was ball-milled again for 24 h to make the mixture more evenly. A moderate amount of 5 wt% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) was dripped into the fine powders time by time as a binder to form granular clusters, and then they were pressed into disks (1 mm in thickness and 10 mm in diameter) under the applied pressure of near 400 MPa. PVA was burnt off at 850 °C for 3 h, and then green disks were sintered at 1040–1100 °C for 3 h under a corundum crucible in air.

Density measurements

The density of as-sintered ceramics was measured by the Archimedes method, which was widely used in the research of piezoceramics40,41. In this work, we used an electronic balance (with precision of 0.0001 g, BSA224S, Sartorius, Germany) equipped with a set of accessories for measuring density (see Fig. S33). The detailed process is listed as follows. We first cleaned up as-sintered samples and then put them into the drying oven with temperature of 120 °C for 2 h, with the purpose of removing the moisture. Then, we constructed the apparatus shown in Fig. S33. The hollow metal basket was completely immersed into the deionized water. Subsequently, the dry weight (m1) of samples was measured by putting the sample in the top small box. After obtaining the dry weight (m1), the sample was quickly transferred into the hollow metal basket and kept for 30 min, consequently obtaining the wet weight (m2). According to the buoyancy principle (i.e., \(V=\frac{{m}_{1}-{m}_{2}}{{\rho }_{\mathrm{water}}}\), V is the volume of samples and ρ is the density of deionized water (i.e., 1 g·cm−3). Therefore, the density of samples was calculated by the equation of \({\rho }_{\mathrm{sample}}=\frac{{m}_{1}}{V}=\,\frac{{m}_{1}}{{m}_{1}-{m}_{2}}\). For each composition, the density was determined by averaging five samples. The relative density was calculated by the ratio between the measured density and the theoretical density of 4.51 g·cm−342. All sintered ceramic disks show a relative density higher than 95% (see Table S5). Note that the presence of closed pores may affect the accuracy of the Archimedes method, which was the possible reason why some references reported high densities but also observed visible pores40.

Basic structure characterizations

X-ray diffraction (XRD) instrument (Bruker D8 Advance XRD, BrukerAXS Inc., Madison, WI, Cu-Kα) was used to measure the crystal structure of as-sintered samples. Then, samples were ground into fine powders for the neutron diffraction experiments. Temperature-dependent Raman spectra were recorded on a Jobin-Yvon LabRAM HR Evolution micro-Raman spectrometer with excitation sources of 514 nm from an Ar+ laser, in connection with an external temperature controller. To perform the out-of-plane piezoresponse force microscopy (OP-PFM) measurements, the as-sintered samples were polished mechanically with the nano-diamond polishing slurry (DS001, Truer, Shanghai, China). Ferroelectric domains were observed in the contact mode by using a commercial atomic force microscope (MFP-3D, Asylum Research, Goleta, USA) aided by a conductive Pt-Ir-coated cantilever (PPP-NCHPt, Nanosensors, Switzerland). Switching spectroscopy piezoelectric force microscopy (SS-PFM) was obtained by applying an alternating voltage of ±30 V. To detect the domain reversal with the litho-PFM mode, a voltage of −40 V is applied first, and then the gradient-increasing voltage from +5 to +20 V is applied to make some domains switch back to the up. Then, polished samples were thermally etched at a temperature 50 °C lower than the sintering temperature for 30 min. The surface morphology of polished and thermally-etched samples was recorded by a field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JSM-7500, Japan). The chemical composition of KNN-0.06BNZ ceramics was analyzed by the SEM energy disperse spectroscopy (SEM-EDS). To analyze the chemical composition of KNN-0.06Li ceramics, the inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES, 5100 SVDV, Agilent, USA) and the time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS, PHI nanoTOF II, ULVAC-PHI, Inc., Japan) measurements were conducted. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy measurements (AXIS Supra, Kratos, UK) were measured to evaluate the oxygen vacancy.

Electrical property measurements

Temperature- and frequency-dependent dielectric properties (i.e., the real part of dielectric constant, the imaginary part of dielectric constant and the dielectric loss) of unpoled (i.e., ε′, ε″, and tan δ) and poled samples (i.e.,\(\,{\varepsilon }_{33}^{{\prime} }\), \({\varepsilon }_{33}^{{\prime\prime} }\), and tan δ) were measured by a broadband dielectric spectrometer (Novocontrol Concept 80, Novocontrol Technologies GmbH, Germany) over the temperature range of −150–250 °C and −260–0 °C. The temperature-dependent relative dielectric permittivity (εr) was measured at 30–550 °C by using the dielectric spectroscopy test system (TZDM-RT-800, Harbin Julang Technology Co Ltd., Harbin, China). Polarization-electric field (P–E) loops and strain-electric field (S–E) curves were collected by using a commercial ferroelectric workstation (aixACCT TF Analyzer 2000, Germany) with a laser interferometer vibrometer (SP-S120/500, SIOS Meßtechnik GmbH, Germany). The small signal piezoelectric coefficient (d33) was obtained from a quasi-static d33 meter (ZJ-3A, China Academy of Acoustics, China).

Synchrotron X-ray diffraction measurements

The temperature-dependent synchrotron X-ray diffraction measurements of KNN-0.06Li and KNN-0.06BNZ ceramic powder samples were conducted on BL02U2 instrument of Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). The wavenumber of beamline is about 1.27 Å, and the beam energy is about 10 keV.

TEM/STEM measurements

The sintered ceramic samples were cut, grinded, and polished to pellets of 3 mm in diameter and 30 μm in thickness followed by ion-milling of Ar+ using a Gatan PIPS II (Gatan Inc., Pleasanton, CA) from 3 keV to 0.5 keV for reducing ion-beam damage. The perforated thin disc was coated with a thin carbon film to reduce charge accumulation during electron beam illumination in TEM experiments. A JEM-F200 microscope was used to acquire dark-field images and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns. The atomic-scale high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) imaging was carried out on a Cs-corrected Hitachi HF5000 microscope with ultra-high resolution (UHR) mode and a convergence/collection semi-angle of 20 mrad/60‒320 mrad. The atomic column positions at picometer-precision fitting were operated by MATLAB code43,44.

DFT calculations

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were implemented in the framework of Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) in conjunction with the Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange-correlation based on the generalized gradient approximation (GGA)45,46,47,48,49. The projector augmented wave (PAW) was utilized to describe the electron-ion interactions and plane wave cutoffs were set to 500 eV. The valence electron configurations were K 3s3p4s, Na 2p3s, Nb 4s4p4d5s, Li 1s, Bi 5d6s6p, O 2s2p states. Two KNN structures, one with the Pm phase and the other with the P4mm phase, were considered, respectively. In the case of Pm phase, the supercell size is 2 × √2 × 3√2 and contains 60 atoms. In the case of P4mm phase, the supercell size is 2 × 2 × 4 and contains 80 atoms. For Li- and Bi-doped supercells, each supercell contains one Li or Bi atom that replaced one Na atom. The relaxed supercell configurations were depicted in Fig. S25. All models were exhibited using the 6 × 9 × 3 Monkhorst-Pack k-point meshes50. The convergence criteria for electronic self-consistent iterations were set to 10−6 eV, and atomic coordinates were optimized until the Hellmann-Feynman forces were less than 0.001 eV/Å. The simulation data was analyzed by employing VASPKIT, a pre-and post-processing tool for the VASP code.

Neutron total scattering measurements

Time-of-flight (TOF) neutron scattering experiments were performed at the Nanoscale-Ordered Materials Diffractometer (NOMAD) BL1B instrument of the Spallation Neutron Source (SNS)51. The synthesized powder samples were loaded into vanadium cans of a diameter of ~6 mm, which were placed on an automatic sample changer for sequential data collection. For each sample, two 24 min long datasets (comparable proton charges) were collected and then summed together to improve the measurement statistics. Background intensity measured from an empty vanadium can was subtracted from the neutron scattering intensity measured from each sample. The background-corrected intensity was subsequently normalized against the signal from a 6 mm vanadium rod to correct for detector efficiency. Self-scattering was subtracted during the data reduction, and the data was not absolutely normalized. The intensities were normalized and reduced to the structure function S(Q). To obtain the corresponding reduced PDFs, the S(Q) data were then Fourier-transformed using the function:

where Qmin = 0.2 Å−1 and Qmax = 40 Å−1.

Neutron data analysis

Rietveld refinements of Bragg diffraction from the middle four banks, corresponding to 2θ of 31°, 67°, 122°, and 154°, were carried using the General Structure Analysis System (GSAS-II) software20. PDF small-box modeling was conducted using the software PDFgui52. Big-box modeling was conducted using RMCprofile53. Starting configurations for all compositions were generated based on the best fit of monoclinic (M) model to Bragg diffraction data. The modeling boxes contains 12 × 12 × 12 unit cells, 8640 atomic sites, with dimensions of approximately 48 × 48 × 48 Å. Fits to the PDF and F(Q) data were conducted, fixing PDF data fits across 1.5–10 Å. A “distance-window” constraint was applied to avoid unphysical pair distances, and bond valence sum restraints were used to minimize unphysical bonding configurations. Swapping was allowed between different cations occupying the same sites in the ABO3 structure. To ensure statistical reliability, RMC refinements were performed 20 times to assess the consistency of the final results.

Phase-field simulations

To investigate the intricate domain configurations present in randomly arranged grain configurations, an order parameter η was introduced to encapsulate the wide range of crystal orientations. To capture the polarization characteristics within these diverse grain structures, two distinct coordinate systems were adopted. Within each individual grain, the domain structure manifests as a locally spontaneous polarization phenomenon. Transitioning to a broader perspective, the phase-field model incorporated key order parameters such as global polarization P and displacement field u. The temporal evolution of polarization was tracked by utilizing the time-dependent Ginzburg-Landau (TDGL) equation, in conjunction with the stress/electric field equilibrium equation,

Here, L represents a kinetic coefficient associated with domain wall mobility, while F denotes the overall free energy of the system. The thermodynamic driving force is represented by \(\frac{\delta F}{\delta {P}_{j}}\), and σij signifies the stress tensor. Additionally, D stands for the electric displacement, and \({\rho }_{f}\) represents the free charge density. r and t are the spatial coordinate and time, respectively. The total free energy of a bulk system can be formulated as follows,

Where F includes the bulk free energy \({F}_{\mathrm{bulk}}({\boldsymbol{P}})\), domain-wall energy \({F}_{\mathrm{grad}}({\boldsymbol{P}})\), elastic energy \({F}_{\mathrm{elastic}}({\boldsymbol{P}})\), and electrostatic energy \({F}_{\mathrm{elec}}({\boldsymbol{P}},\,{\boldsymbol{E}})\), E is the applied static electric field. fLand, fgrad, felastic and felec are the corresponding energy density.

The bulk free energy density within a specific grain can be expressed as an expansion in terms of polarization components. In the context of the KNN system, the bulk free energy density can be comprehensively described as follows:

fLand incorporates the Landau coefficients \({a}_{1}-{a}_{1123}\) and the polarization field PL in the local crystallographic coordinate system within each grain. The polarization within the local coordinate system can be formulated as a transformation arising from the polarization expressed in the global coordinate system, achieved through the application of a transformation matrix,

The transformation matrix tr facilitates the transition from the global to the local coordinate system,

The gradient energy density in an anisotropic system can be calculated by

where gijkl is the gradient energy coefficient and \({P}_{i,j}=\frac{\partial {P}_{i}}{\partial {x}_{j}}\). The elastic energy density can be described as:

where \({c}_{ijkl}\) is the stiffness tensor, \({e}_{ij}\) is the elastic strain tensor, \({\varepsilon }_{ij}\) is the total strain tensor, and \({\varepsilon }_{ij}^{0}\) is the eigenstrain,

where \({\varepsilon }_{Lij}^{0}\) is the eigenstrain with respect to the local coordinate system, \({Q}_{ijkl}\) is the electrostrictive coefficient tensor. Consequently, the eigenstrain in the global coordinate system can be derived by employing an appropriate transformation matrix,

The electrostatic energy density felec of the system in phase-field simulation is given by,

where \({E}_{i}^{{in}}(r)\) is the E-field induced by the dipole moments, \({E}_{i}(r)\) is the applied electric field and \({E}_{{RF}}\) is the local electric field caused by the random point defects.

The parameters (all in SI units) in details are \({a}_{1}=4.29\left(\mathrm{Coth}\left[\frac{140}{T}\right]- \, \mathrm{Coth}\left[\frac{140}{657}\right]\right)\times {10}^{7}\), \({a}_{11}=-2.73\times {10}^{8}\), \({a}_{12}=1.0861\times {10}^{9}\), \({a}_{111}=3.04\times {10}^{9}\), \({a}_{112}=-2.73\times {10}^{9}\), \({a}_{123}=1.55\times {10}^{10}\), \({a}_{1111}=2.4\times {10}^{10}\), \({a}_{1112}=3.73\times {10}^{9}\),\({a}_{1122}=3.34\times {10}^{10}\), \({a}_{123}=-6.2\times {10}^{10}\), \({Q}_{11}=0.13\), \({Q}_{12}=- 0.047\), \({Q}_{44}=0.052\), \({s}_{11}=5.5\times {10}^{-11}\), \({s}_{12}=-1.6\times {10}^{-10}\), \({s}_{44}=1.3 \times {10}^{-9}\). Here, s represents the compliance coefficients, and Q denotes the electrostrictive coefficients. The simulation scale encompassed a domain of 512dx × 512dz, with grid scales dx and dz set to 10 nm. For the random grain structure, a random Euler angle ranging from −45 degrees to 45 degrees was chosen. To solve the equations, the Fourier method was utilized. Furthermore, the calculations incorporated the open-circuit electrical boundary condition, in conjunction with periodic mechanical boundary conditions, ensuring accurate and comprehensive simulations.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data that support the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information file. More relevant datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the first authors and corresponding authors on reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Jaffe, B., Cook, W. R. & Jaffe, H. Piezoelectric Ceramics (Academic Press, 1971).

Trolier-McKinstry, S., Zhang, S., Bell, A. J. & Tan, X. High-performance piezoelectric crystals, ceramics, and films. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 48, 191–217 (2018).

Rödel, J. & Li, J.-F. Lead-free piezoceramics: status and perspectives. MRS Bull. 43, 576–580 (2018).

Lv, X., Zhu, J., Xiao, D., Zhang, X. -x & Wu, J. Emerging new phase boundary in potassium sodium-niobate based ceramics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 671–707 (2020).

Li, J. F., Wang, K., Zhu, F. Y., Cheng, L. Q. & Yao, F. Z. K, Na)NbO3-based lead-free piezoceramics: fundamental aspects, processing technologies, and remaining challenges. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 96, 3677–3696 (2013).

Wu, J., Xiao, D. & Zhu, J. Potassium–sodium niobate lead-free piezoelectric materials: past, present, and future of phase boundaries. Chem. Rev. 115, 2559–2595 (2015).

Kong, J. et al. A local atomic mechanism for monoclinic-tetragonal phase boundary creation in Li-doped Na0.5K0.5NbO3 ferroelectric solid solution. Inorg. Chem. 61, 4335–4349 (2022).

Wang, K. & Li, J.-F. Analysis of crystallographic evolution in (Na,K)NbO3-based lead-free piezoceramics by x-ray diffraction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 262902 (2007).

Tellier, J. et al. Crystal structure and phase transitions of sodium potassium niobate perovskites. Solid State Sci. 11, 320–324 (2009).

Lin, J. et al. Multiscale reconfiguration induced highly saturated poling in lead-free piezoceramics for giant energy conversion. Nat. Commun. 15, 2560 (2024).

Saito, Y. et al. Lead-free piezoceramics. Nature 432, 84–87 (2004).

Liu, Q. et al. High-performance lead-free piezoelectrics with local structural heterogeneity. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 3531–3539 (2018).

Zhang, M.-H. et al. Deciphering the phase transition-induced ultrahigh piezoresponse in (K,Na)NbO3-based piezoceramics. Nat. Commun. 13, 3434 (2022).

Liu, Y., Liu, H., Sun, S., Wang, L. & Chen, J. Direct observation of electric field-induced tetragonal-orthorhombic phase transition in KNN-based piezoelectric ceramics via in-situ synchrotron diffraction. Scr. Mater. 207, 114283 (2022).

Yang, W. et al. A study on the relationship between grain size and electrical properties in (K, Na)NbO3-based lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. Adv. Electron Mater. 5, 1900570 (2019).

Li, F. et al. Giant piezoelectricity of Sm-doped Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3-PbTiO3 single crystals. Science 364, 264–268 (2019).

Yashima, M., Omoto, K., Chen, J., Kato, H. & Xing, X. Evidence for (Bi,Pb)–O covalency in the high TC ferroelectric PbTiO3–BiFeO3 with large tetragonality. Chem. Mater. 23, 3135–3137 (2011).

Zou, J. et al. Enhancing piezoelectric coefficient and thermal stability in lead-free piezoceramics: insights at the atomic-scale. Nat. Commun. 15, 8591 (2024).

Shvartsman, V. V. & Lupascu, D. C. Lead-free relaxor ferroelectrics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 95, 1–26 (2012).

Toby, B. H. & Von Dreele, R. B. GSAS-II: the genesis of a modern open-source all purpose crystallography software package. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 46, 544–549 (2013).

Levin, I. et al. Coupling of emergent octahedral rotations to polarization in (K,Na)NbO3 ferroelectrics. Sci. Rep. 7, 15620 (2017).

Wang, N., Yao, Y., Liu, H. & Chen, J. Role of Na in structural and polarization characteristics of prototype lead-free K0.5Na0.5NbO3 piezoelectrics. Scr. Mater. 244, 116032 (2024).

Tan, Z., Peng, Y., An, J., Zhang, Q. & Zhu, J. Intrinsic origin of enhanced piezoelectricity in alkali niobate-based lead-free ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 102, 5262–5270 (2019).

Kong, J., Liu, J., Marlton, F., Jørgensen, M. R. V. & Pramanick, A. Local structural mechanism for phase transition and ferroelectric polarization in the mixed oxide K0.5Na0.5NbO3. Phys. Rev. B 103, 184104 (2021).

Li, F. et al. Ultrahigh piezoelectricity in ferroelectric ceramics by design. Nat. Mater. 17, 349–354 (2018).

Gao, X. et al. The mechanism for the enhanced piezoelectricity in multi-elements doped (K,Na)NbO3 ceramics. Nat. Commun. 12, 881 (2021).

Kim, S. et al. Piezoelectric actuation mechanism involving extrinsic nanodomain dynamics in lead-free piezoelectrics. Adv. Mater. 35, 2208717 (2023).

Arzenšek, M. et al. Origins of the large piezoelectric response of samarium-doped lead magnesium niobate–lead titanate ceramics. Sci. Adv. 10, eadp0895 (2024).

Li, F. et al. The origin of ultrahigh piezoelectricity in relaxor-ferroelectric solid solution crystals. Nat. Commun. 7, 13807 (2016).

Kuroiwa, Y. et al. Piezoelectricity in perovskite-type pseudo-cubic ferroelectrics by partial ordering of off-centered cations. Commun. Mater. 1, 71 (2020).

Kimura, T. et al. Synthesis and piezoelectric properties of Li-doped BaTiO3 by a solvothermal approach. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 33, 1009–1015 (2013).

Huang, Y. et al. Giant electrostrictive effect in lead-free barium titanate-based ceramics via A-site ion-pairs engineering. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 17366–17375 (2019).

Bahri, F., Simon, A., Khemakhem, H. & Ravez, J. Classical or relaxor ferroelectric behaviour of ceramics with composition Ba1-xBi2x/3TiO3. Phys. Status Solidi A 184, 459–464 (2001).

Ogihara, H., Randall, C. A. & Trolier-McKinstry, S. Weakly coupled relaxor behavior of BaTiO3–BiScO3 ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 92, 110–118 (2009).

Lou, Q. et al. Ferroelectric properties of Li-doped BaTiO3 ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 101, 3597–3604 (2018).

Thong, H.-C. et al. Increased Curie temperature in lithium substituted ferroelectric niobate perovskite via soft polar mode enhancement. NPJ Comput Mater. 11, 92 (2025).

Zuo, R., Wang, M., Ma, B., Fu, J. & Li, T. Sintering and electrical properties of Na0.5K0.5NbO3 ceramics modified with lanthanum and iron oxides. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 70, 750–754 (2009).

Wang, D. et al. Composition and temperature dependence of structure and piezoelectricity in (1−x)(K1−yNay)NbO3-x(Bi1/2Na1/2)ZrO3 lead-free ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 100, 627–637 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. New lead-free (1−x)(K0.5Na0.5)NbO3–x(Bi0.5Na0.5)ZrO3 ceramics with high piezoelectricity. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 97, 688–690 (2014).

Liu, Y.-X., Thong, H.-C., Cheng, Y.-Y. -S., Li, J.-W. & Wang, K. Defect-mediated domain-wall motion and enhanced electric-field-induced strain in hot-pressed K0.5Na0.5NbO3 lead-free piezoelectric ceramics. J. Appl Phys. 129, 024102 (2021).

Han, H.-S. et al. Hardening behavior and highly enhanced mechanical quality factor in (K0.5Na0.5)NbO3–based ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 37, 2083–2089 (2017).

Jaeger, R. E. & Egerton, L. Hot pressing of potassium-sodium niobates. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 45, 209–213 (1962).

De Backer, A., van den Bos, K. H. W., Van den Broek, W., Sijbers, J. & Van Aert, S. StatSTEM: an efficient approach for accurate and precise model-based quantification of atomic resolution electron microscopy images. Ultramicroscopy 171, 104–116 (2016).

Van Aert, S. et al. Advanced electron crystallography through model-based imaging. IUCrJ 3, 71–83 (2016).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133–A1138 (1965).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Wang, Y. Generalized gradient approximation for the exchange-correlation hole of a many-electron system. Phys. Rev. B 54, 16533–16539 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Neuefeind, J., Feygenson, M., Carruth, J., Hoffmann, R. & Chipley, K. K. The Nanoscale Ordered MAterials Diffractometer NOMAD at the spallation neutron source SNS. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res Sect. B-Beam Interact. Mater. At. 287, 68–75 (2012).

Farrow, C. L. et al. PDFfit2 and PDFgui: computer programs for studying nanostructure in crystals. J. Phys: Condens Matter 19, 335219 (2007).

Tucker, M. G., Keen, D. A., Dove, M. T., Goodwin, A. L. & Hui, Q. RMCProfile: reverse Monte Carlo for polycrystalline materials. J. Phys: Condens Matter. 19, 335218 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant Nos. 12204327 (X.L.) and U23A20567 (J.W.)], the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province [Grant Nos. 2023NSFSC0967 (X.L.) and 2024NSFJQ0025 (J.W.)], the Sichuan University postdoctoral interdisciplinary Innovation Fund [Grant No. 1082204112L76 (J.W.)], and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [(J.W.)]. A portion of this research used resources at the Spallation Neutron Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility operated by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory [Grant No. IPTS-30510 for POWGEN and NOMAD instruments (A.P.)]. Dr. Yueliang Gu at SSRF is appreciated for helping collect the synchrotron data. The authors thank Ms. Hui Wang and Mr. Xi Wu (both from the Analytical & Testing Center of Sichuan University) for conducting the FE-SEM and ICP-OES measurements, respectively.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L. and J.W. conceived the idea of this work. B.W. and X.W. prepared KNN-xLi and KNN-yBNZ ceramics, respectively. X.W., X.L., and J.W. measured the electrical properties, SEM images, OP-PFM images, and temperature-dependent synchrotron XRD patterns. X.S. and H.H. performed the phase-field simulations. T.H. and Z.F. conducted the TEM/STEM measurements and analysis. J.L. worked on the DFT calculations. Y.M. and X.Z. measured XRD patterns and temperature-dependent dielectric properties. J.K. and A.P. measured the neutron data and conducted related analysis. All authors contributed to data analysis and discussion. X.W., J.K., X.S., T.H., X.L., and J.W. wrote the draft, and all authors participated in its modification. X.L., J.K., and J.W. dealt with the review responses and revisions for paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Dang Duc Dung, Yukio Sato and Jan Suchanicz for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lv, X., Wang, X., Shi, X. et al. Beyond phase boundaries: atomic mechanisms governing structure and property variations in (K, Na)NbO3-based ferroelectrics. Nat Commun 17, 859 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67573-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67573-z