Abstract

Vibronic coupling and coherence are crucial in the charge and energy transfer of photoexcited molecules. Here we investigate the coupled electron-nuclear dynamics of the photoionized benzene molecule using the time-resolved Coulomb-explosion imaging method. A long-period oscillation is experimentally observed in the ion yields of the \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\) channel, as well as the C+ + C+, and the C+ + C+ + C+ Coulomb explosion channels. Quantum dynamics simulations reveal that this ~600 fs oscillation, which notably exceeds the period of any vibrational modes, originates from pseudorotation of the benzene cation. This motion arises from quantum beating between two coherent vibronic states of the benzene molecule coupled via the Jahn-Teller effect around the conical intersection. The structural evolution of the benzene cation via pseudorotation is visualized by the time-resolved momentum imaging in the C+ + C+ + C+ three-body Coulomb explosion channel. Our work offers a comprehensive characterization of coherent vibronic dynamics of the benzene cation and demonstrates the power of the time-resolved Coulomb-explosion imaging for unraveling coupled electronic and nuclear motions in aromatic molecules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electronic and vibrational coherence governs many light-induced dynamics in atto- and femtosecond processes, such as the charge migration, charge separation, and energy transfer in molecules1,2,3,4,5,6. As a paradigmatic example of aromatic ring molecules, the Jahn–Teller distortion of a photoexcited benzene molecule plays a vital role in many areas of physics and chemistry7,8. The ultrafast charge transfer process and energy relaxation in complex aromatic molecules after photoexcitation are closely related to the non-adiabatic coupling between electrons and nuclei9,10,11. One of the important non-adiabatic phenomena of benzene is the symmetry-induced (Jahn–Teller) conical intersection (CI)12, where the intrinsic geometric instability of the degenerate electronic states of the benzene cation leads to spontaneous symmetry breaking (SSB) of the molecular geometry and lifting of electronic degeneracy13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. SSB significantly impacts a wide range of areas that include molecular physics, condensed matter physics, quantum field theory, and the Standard Model of particle physics such as the Higgs mechanism21. The Jahn–Teller (JT) effect of benzene cation has been studied both experimentally7,22 and theoretically23,24,25. The experimental studies of the Jahn–Teller effect and pseudorotation in molecules mostly rely on high-resolution spectroscopy, including infrared or microwave spectroscopy, and zero-kinetic-energy threshold photoelectron spectroscopy among others26,27,28,29.

Interestingly, the JT effect can lead to the internal rotation of the molecule, dubbed pseudorotation30,31,32,33, which connects several stable isoenergetic structures separated by potential barriers and leads to conformational changes of the molecule34. Unlike real rotations where all atoms in the molecule rotate synchronously, in pseudorotation, the molecular structure undergoes a sequence of bond-angle changes that mimics rotation15. Although many examples of JT-effect-induced vibronic pseudorotation are known, direct real-time imaging of the phenomenon is still lacking. The vibrational wavepacket dynamics of the benzene cation, in which both the JT-effect-induced pseudorotation and the non-adiabatic coupling participate, serves as a prototype to reveal the role of conical intersections in the ultrafast coherent vibronic dynamics35. The CI-mediated population transfer can induce electronic coherence, and its magnitude is highly dependent on the symmetry of electronic states36,37.

In this article, we report a ~600 fs coherent vibronic motion of benzene caused by strong field ionization of benzene molecule, in which the Jahn-Teller coupling between the excited cationic states plays a significant role. The temporal evolution of the nuclear vibrational wavepacket, including both the stretching of the C–C bond within ~200 fs and the hundreds-femtosecond-long pseudorotation accompanying the quantum beating between two vibronic states, are revealed by the time-resolved ion yield oscillations of the \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\), C+ + C+, and C+ + C+ + C+ channels. Finally, we capture the transient structural evolution involved in the pseudorotation from time-resolved momentum angle distributions in three-body Coulomb explosion channels. Our results, analyzed with the help of full-dimensional quantum dynamics simulations, provide a comprehensive picture of vibronic coherence mediated by symmetry-induced CIs, along with snapshots of transient structures during pseudorotation. This opens a new avenue for investigating coupled electronic and nuclear motions in aromatic ring systems.

Results and discussion

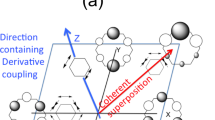

Figure 1a presents the experimental scheme. A femtosecond pulse centered at 800 nm with a pulse width of 80 fs is split into pump and probe pulses. The pump pulse ionizes the benzene molecules to a manifold of cationic states, and a delay-controlled probe pulse ionizes the benzene cation to the dicationic or tricationic states, which forms bounded \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\) dications or dissociates the molecule via Coulomb explosion. Figure 1b presents the energy diagram of our pump-probe measurement and the potential energy curve along the nuclear vibrational coordinate Q18x. The symmetry analysis of electronic states and JT active modes is crucial to understand the vibronic coupling Hamiltonian23, electronic coherence36 and the three-minima structure of adiabatic potential energy surface in Fig. 1c, which corresponds to the pseudorotation of benzene. From wavepacket dynamics simulations, we identify that the Q18 mode serves as the driving coordinate for the long-period pseudorotation, and is also the active mode of the Jahn–Teller effect. The vibrational mode Q18 belongs to the E2g symmetry representation of D6h point group, which is doubly degenerate with two components Q18x and Q18y, as illustrated in Fig. 1c. The pump pulse can populate the cationic \(\tilde{D}\) and \(\tilde{E}\) states through a strong field ionization mechanism38,39. The population of \(\tilde{D}\) and \(\tilde{E}\) states is strongly associated with the long-period oscillation of the experimentally measured ion yields shown in Fig. 1d–f, because our quantum simulations show that only the wavepacket dynamics initiated from both \(\tilde{D}\) and \(\tilde{E}\) states show the corresponding long-period oscillatory behavior (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for detailed autocorrelation analysis of wavepacket dynamics), while the oscillation periods of the wavepackets initiated from the other lower cationic states are significantly shorter. The intensity of the pump pulse is tuned to enhance this channel, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 of Supplementary Note 1.

a Schematic of experimental setup. b PES along the nuclear vibrational coordinate Q18x and schematic of the \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{+}\) wavepacket dynamics. The pump pulse initiates the \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{+}\) wavepacket dynamics in \(\tilde{D}\) and \(\tilde{E}\) cationic states, and a delay-controlled probe pulse further ionizes \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{+}\), leading to bounded \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\) and dissociative C+ + C+ Coulomb explosion channels. c The adiabatic PES of \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{+}\,\tilde{D}\) state along Q18x and Q18y vibrational modes, which is active for the Jahn-Teller effect of \(\tilde{D}\) state and the pseudo-Jahn-Teller coupling between \(\tilde{D}\) and \(\tilde{E}\) states. The coherent vibronic motion of \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{+}\) wavepacket among three potential minima leads to the long-period oscillation of experimental ion yields. Experimentally measured time-resolved ion yields of (d) bounded \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\) and (e) C+ + C+ Coulomb explosion channel as a function of pump-probe time delay. d Is fitted to a decaying oscillation function to obtain the oscillation period T = 621 ± 49 fs. To characterize the oscillatory yield of the C+ + C+ channel, the ion yields are firstly fitted with an exponential decay (e), and the residual distribution is also fitted to the decaying oscillation function (f) (see Supplementary Note 6 for details of fitting). The statistical errors are obtained as the square root of the counts and are shown as the gray shadow (too small to be see). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Figure 1d shows the measured time-resolved ion yield of the \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\) channel. The \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\) channel exhibits a prominent oscillation of the ion yield as a function of the pump-probe time delay. The signal is well described by a decaying oscillatory function, yielding a period of T = 621 ± 49 fs with an initial phase of ϕ = 0.34π ± 0.08π, and a decay-time constant of τ = 316 ± 90 fs. Surprisingly, the oscillation period T is significantly longer than the period of any intrinsic vibrational mode of benzene cation23,24. The Fourier transform (FT) spectrum of the measured oscillation exhibits a dominant frequency centered at ~56 cm−1, as shown in Fig. 2b.

a, b Fourier spectrum analysis for residual signal of C+ + C+ channel and \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\) channel. c Fourier-filtered signal of the ion yields of \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\) and C+ + C+ channel, and the shaded areas represent the standard deviations of the statistical errors. The statistical errors are obtained as the square root of the counts. The yields are divided by the average counts of the long time part and shifted by a constant to facilitate comparison of relative yield changes. The frequency ranges correspond to colored areas under the curves in (a) and (b), centered around 56 cm−1 for \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\) channel, and 69, 408, 611 cm−1 for the three curves of C+ + C+ channel, respectively. d Vibrational spectrum of simulated \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{+}\) wavepacket dynamics initiated from the \(\tilde{E}\) state, obtained from the Fourier analysis of autocorrelation function. e Temporal evolution of the expectation value of the driving vibrational mode Q18x, which exhibits hundreds-femtosecond-long oscillations. f Temporal evolution of \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{+}\) ionization energy Ip to the dicationic ground state and g the corresponding ionization rate calculated by the exponential factor \(\exp [-2{(2{I}_{p})}^{3/2}/3E]\) of the ADK formula, where E is the electric field strength of the ionizing laser. Abbreviations: FT, Fourier transform. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The time-resolved ion yield of \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\to {{{{\rm{C}}}}}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}^{+}\) channel (with other neutral fragments) exhibits somewhat different characteristics, as shown in Fig. 1e. A strong enhancement of the signal around zero time delay is dominating the channel followed by weak long-period oscillations. To analyze the long-period oscillations, the time-resolved ion yield is first fitted with an exponential decay function convolved with a Gaussian function corresponding to the instrument response function, obtaining a decay time constant τd = 116 ± 37 fs. This time scale has been assigned to the decay from the \(\tilde{D}\) state, i.e. the population in the \(\tilde{D}\) state is transferred to the \(\tilde{B}\) state7. The residual signal, obtained by subtracting the fit from the measured C+ + C+ yield, is shown in Fig. 1f and can be well described by a decaying sinusoidal function with a period of T = 570 ± 44 fs.

The Fourier transform spectrum of the residual signal for C+ + C+ channel is shown in Fig. 2a. Interestingly, high-frequency oscillations appear before 200 fs, thus the Fourier spectrum shows two additional bands centered at 408 cm−1 and 611 cm−1 along with the low-frequency peak, which is also present in the Fourier spectrum of the \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\) channel shown in Fig. 2b. Figure 2c shows the Fourier-filtered yield oscillation signals of both \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\) and C+ + C+ channels, which exhibit significant channel dependence. Both channels show long-period oscillation corresponding to ~60 cm−1 peak that persist for ~1 ps. In contrast, the high-frequency oscillation of the C+ + C+ channel decays rapidly within 200 fs.

To interpret the observed long-period oscillation of the ion yields, we performed quantum wavepacket dynamics simulations using the multi-configurational time-dependent Hartree (MCTDH) method40 employing the vibronic-coupling Hamiltonian of \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{+}\) derived in refs. 23,24 (see Supplementary Fig. 4 for the vibrational modes of the Hamiltonian). We simulated the nuclear wavepacket dynamics starting from different cationic states, and their vibrational spectra were obtained from the Fourier transformation of the autocorrelation function, which is a standard method for vibrational analysis2,41 (see Supplementary Note 2 for detailed vibrational spectra analysis). As shown in Fig. 2d, the vibrational spectra of the wavepacket dynamics initiated on the \(\tilde{E}\) state exhibit a low-frequency peak at 56 cm−1, which is consistent with Fig. 2a, b. The 56 cm−1 frequency is much lower than the eigen-frequencies of any vibrational mode of \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{+}\), and can only be formed through the coupling of electronic and nuclear motion, i.e., it is the frequency of a vibronic motion. The wavepacket initiated on the \(\tilde{D}\) state also exhibits low-frequency peaks around 65 cm−1 in the vibrational spectrum (see Supplementary Fig. 2d in Supplementary Note 2), similar to Fig. 2d. The low-frequency peak originates from the long-period pseudorotation dynamics of benzene cation, as shown in Figs. 2e and 3. In contrast, such low-frequency oscillation is absent in the vibrational spectra obtained from the the wavepacket dynamics initiated on the low-lying cationic states \(\tilde{X}\), \(\tilde{B}\), and \(\tilde{C}\) (see Supplementary Fig. 2a–c in Supplementary Note 2). Besides, our simulations show that the nuclear wavepacket, initially on the \(\tilde{E}\) state, is rapidly transferred to the \(\tilde{D}\) state within 50 fs (see Supplementary Fig. 3). The above analysis reveals a strong correlation between the wavepacket dynamics in the \(\tilde{D}\) state and the long-period oscillations in the experimentally measured ion yields. An experimental evidence supporting this conclusion is that the long-term oscillations in the ion yields are enhanced at higher pump laser intensities. As pump laser intensity increases, the ionization ratio to the highly excited cationic states (\(\tilde{D}\) and \(\tilde{E}\)) relative to the cationic ground state (\(\tilde{X}\)) also increases. Consequently, the highly excited cationic states become more significantly populated at higher pump intensities, leading to more pronounced oscillations (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for details).

a Schematic of the relevant vibronic energy levels and PES along Q18 vibrational mode. Under Born-Oppenheimer approximation, the vibrational eigenstates of Q18 mode in the \(\tilde{D}\) state is denoted by the quantum numbers \(\left\vert {{{{\rm{v}}}}}_{18x},{{{{\rm{v}}}}}_{18y}\right\rangle\), and the energy difference between the vibrational ground state \(\left\vert 0,0\right\rangle\) and the first excited states \(\left\vert 1,0\right\rangle\),\(\left\vert 0,1\right\rangle\) is 624 cm−1. The vibronic coupling between \(\tilde{D}\) and \(\tilde{E}\) states reshapes the adiabatic PES of the lower branch to the Mexican hat shape, and the energy difference between the coupled vibronic ground state \(\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\) and the first excited states \(\left\vert {\psi }_{1}\right\rangle,\left\vert {\psi }_{2}\right\rangle\) is 56 cm−1. b Schematic of the molecular structure at different angles of the (Q18x, Q18y) configuration space. The change of molecular geometries are exaggerated for visual convenience. c–i Temporal evolution of probability density Pr(Q18x, Q18y, t) of \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{+}\) wavepacket in \(\tilde{D}\) state. The wavepacket exhibits two different types of motions. c–e Show radial motion between potential minima and high symmetric geometry Q18x = Q18y = 0. f–i Show angular motion moving among the three potential wells. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To explore the origin of the low-frequency oscillation as quantum beating of coherent vibronic states, we analyzed the effect of each vibrational mode on the change of the molecular geometry and found that Q18 is the driving mode of the ~600 fs wavepacket motion (see Supplementary Fig. 5 for detailed comparison of molecular geometry change due to each specific vibrational mode). Symmetry analysis shows that the vibrational mode Q18 of E2g symmetry is both a Jahn-Teller coupling mode for the \(\tilde{D}\) state and a pseudo-Jahn-Teller (PJT) coupling mode between the \(\tilde{D}\) and \(\tilde{E}\) states15. As a result of the JT and PJT couplings, the PES of the \(\tilde{D}\) and \(\tilde{E}\) excited states are largely different from that under Born-Oppenheimer approximation. The shape of the adiabatic PES of the lower branch is a “Mexican hat”, as shown in Fig. 3a, which exhibits three minima corresponding to three equivalent distorted geometries with lower symmetry (see Fig. 3b). With the adiabatic PES, we calculated the vibrational energies and eigenstates using discrete variable representation (DVR)40,42. The vibronic ground state \(\left\vert {\psi }_{0}\right\rangle\) is related to the following Born-Oppenheimer vibrational eigenstates \(\left\vert {{{{\rm{v}}}}}_{18x},{{{{\rm{v}}}}}_{18y}\right\rangle\) as v18x + v18y = 0, 2, 4, while the first excited states \(\left\vert {\psi }_{1}\right\rangle,\left\vert {\psi }_{2}\right\rangle\) are related to \(\left\vert {{{{\rm{v}}}}}_{18x},{{{{\rm{v}}}}}_{18y}\right\rangle\) as v18x + v18y = 1, 3 (see Supplementary Figs. 6, 7 in Supplementary Note 5 for details of DVR calculations). The energy difference between the vibronic ground and first excited states is 56 cm−1. In comparison, the eigen-frequency of the Q18 vibrational mode is 624 cm−1. The vibronic coupling thus leads to significant changes of the energy levels43. Our analysis therefore shows that the experimentally observed long-period oscillation of ion yields stems from the coherent vibronic dynamics of the JT and PJT active mode Q18 that couples the \(\tilde{D}\) and \(\tilde{E}\) states.

The temporal evolution of the probability density along Q18 vibrational modes is illustrated in Fig. 3. As shown in Fig. 3c–e, during the first ~100 fs, the wavepacket rapidly oscillates along the radial direction, i.e., between the JT distorted geometry (at the potential energy minima) and the high-symmetry geometry with Q18x = Q18y = 0. The radial oscillation corresponds to the vibrational 624 cm−1 (53 fs period) eigen-frequency of the Q18 mode, which is consistent with the experimentally measured high-frequency peak in the Fourier spectrum shown in Fig. 2a. The amplitude of the radial motion decreases rapidly with the population decay of the \(\tilde{D}\) state, leaving the wavepacket in the three potential wells. As shown in Fig. 3f–i, after 200 fs, the long-period angular motion of the wavepacket among the three potential wells dominates the dynamics. The wavepacket density evolves from a delocalized distribution spanning the three potential wells to a highly localized one within a single well between 200 fs and 600 fs. After 800 fs, the wavepacket becomes delocalized once again.

We can qualitatively estimate the tunneling ionization rate as the molecular geometry changes along the Q18 coordinate, based on the dominant exponential factor \(\exp [-2{(2{I}_{p})}^{3/2}/3E]\) of the Ammosov–Delone–Krainov (ADK) formula, where Ip is the ionization energy and E is the electric field strength of the ionizing laser. The ionization energy from the \(\tilde{D}\) state to the dicationic ground state is shown in Fig. 2f. As shown, the corresponding relative ionization rate exhibits oscillations that are consistent with the dicationic yield reported in Fig. 1d. The dynamics thus corresponds to the pseudorotation of benzene cation31,32, which arises from the vibronic JT coupling between the \(\tilde{D}\) and \(\tilde{E}\) states, and accounts for the observed low-frequency oscillations in the ion yield, since the geometric variation modulates the ionization energy and consequently the ionization rate.

Can we gain a deeper understanding of the structural evolution of the benzene cation that occurs during the pseudorotation? For this purpose, the time-resolved three-body Coulomb explosion imaging is implemented to extract the transient structure of benzene cation44,45,46, which has been successfully utilized to track the ultrafast structural dynamics such as internal rotation in other molecules47,48. The dominant three-body Coulomb explosion channel measured in our experiment is C+ + C+ + C+ channel. There are three possible dissociation pathways that can contribute to this channel, including \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{1}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{2}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{3}^{+}\), \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{1}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{2}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{4}^{+}\), and \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{1}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{2}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{5}^{+}\), where the subscripts label different C atoms in benzene, as shown in the inset of Fig. 4b. The ranges of kinetic energy release (KER) for the three pathways are different. We present the time-resolved KER spectra and ion yield for \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{1}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{2}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{3}^{+}\) pathway in Fig. 4a–c. As shown in Fig. 4c, the ion yield of \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{1}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{2}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{3}^{+}\) channel also exhibits a ~600 fs long-period oscillation as a function of pump-probe time delay, similar to C+ + C+ and \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\) channels in Fig. 1. The KER spectra of other pathways including \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{1}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{2}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{4}^{+}\) and \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{1}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{2}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{5}^{+}\) are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9 of Supplementary Note 7.

a Time-resolved KER spectra and b ion yield of \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{1}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{2}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{3}^{+}\) three-body Coulomb explosion channel. The ion yield is fitted with an exponential decaying function, and the residual signal shown in (c) is fitted with a decaying oscillation function. The statistical errors are obtained as the square root of the counts and are shown as the gray shaded area in the figure. The yields are divided by the average counts of the long time part. d, e Difference in the experimentally measured momentum angle distribution at different pump-probe time delays, where θp is the momentum angle between \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{1}^{+}\) and \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{3}^{+}\) ion fragments. (For detailed calculations, see Supplementary Note 7). d Is obtained by subtracting the momentum angle distribution at 600 fs from that at 300 fs. Similarly, e is obtained by subtracting the momentum angle distribution at 600 fs from that at 900 fs. In comparison, f and g present the same difference plots obtained from the simulated wavepacket dynamics. Diff. Difference, Exp. Experiment, Sim. Simulation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The time-resolved momentum angular distributions between \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{1}^{+}\) and \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{3}^{+}\) ion fragments from the three-body Coulomb explosion channel reflect the structural evolution of the carbon skeleton of the benzene cation. Since the time-dependent features are superimposed on a strong time-independent background signal in our measurements, we reveal the structural variation by presenting the differences in the momentum angle distributions at three representative time delays: 300 fs, 600 fs, and 900 fs. These time delays correspond to the peak and dip of the ion yield oscillation in Fig. 4c. The difference spectra in Fig. 4d, e are obtained by subtracting the momentum angle distribution at 600 fs from that at 300 fs and 900 fs, respectively. In both Fig. 4d, e, clear oscillations can be observed, and the positive (negative) peaks stand for the ratio of the structure contributing to the specific momentum angle after three-body Coulomb explosion increases (decreases). The oscillations are overall similar in Fig. 4d, e but are more pronounced in e. Figure 4e exhibits four well-resolved peaks, which are located at 124∘, 132∘, 141∘, and 147∘, respectively. The prominent dips are located at 128∘, 136∘ and 144∘, respectively. The similarity of Fig. 4d, e suggests that the momentum angle distributions at 300 fs and at 900 fs are similar, and that both are different from the distribution at 600 fs. Therefore, the long-period structural evolution of benzene cation is revealed through time-resolved three-body Coulomb explosion from two different perspectives: the oscillation of total ion yield reported in Fig. 4c, and the momentum angle variation shown in Fig. 4d, e.

To further confirm the structural evolution, we simulated the time-dependent three-body Coulomb explosion process which serves as a probe for the pseudorotation dynamics. The distribution of momentum angles θp from 0 fs to 1000 fs is shown in Supplementary Fig. 11 of Supplementary Note 7. For direct comparison with the measurement, the difference spectra are also obtained in the same way as in the measurement. The results are shown in Fig. 4f, g. As we see, the computed signal exhibits very similar oscillations, with four dominant peaks that are consistent with the measurement (compare panels e and g). The four dominant peaks are locate at 123∘, 127∘, 130∘, and 133∘, respectively. Those values are quantitatively smaller than those extracted from the measurement; we attribute those discrepancies to an idealized modeling of the Coulomb explosion in the simulation, where the structural relaxation during the multiple ionization within the femtosecond laser pulse is not considered49. The overall agreement between measurement and simulations is nevertheless quite good showing that more sophisticated structural changes of the benzene cation during the pseudorotation can be inferred based on the quantum simulations.

Finally, we comprehensively summarize how the bond angles of the benzene cation evolve in real time and space. The momentum angle θp measured in the \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{1}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{2}^{+}+{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{3}^{+}\) three-body Coulomb explosion channel sensitively reflects the bond angle θC of the carbon ring in benzene (see Supplementary Fig. 10 in Supplementary Note 7 for how the structural change of benzene cation affects the momentum angle). From the quantum wavepacket dynamics, we obtain the time-dependent distribution of θC, as shown in Fig. 5a, which exhibits the long-period variations. The vibrational mode Q18 is the driving mode for the temporal change of θC (see Supplementary Figs. 4, 5), so the long-period pseudorotation shown in Fig. 3 along Q18 vibrational mode is also reflected by the time-resolved bond angle distribution in Fig. 5a. From Fig. 3f we see that at ~200 fs, the wavepacket is predominantly located within the bottom of the three potential wells, corresponding to the 0∘, 120∘ and −120∘ geometries in Fig. 3b. For these geometries, four of the θC bond angles in the carbon ring become larger compared to the equilibrium benzene geometry, and two θC become smaller. The corresponding feature is shown in Fig. 5b, which exhibits a single peak when θC < 120∘ and double peaks when θC > 120∘ at 300 fs. At 600 fs, part of the wavepacket is already distributed in the saddle point region of the PES, as shown in Fig. 3h, corresponding to the 60∘, 180∘, and −60∘ geometries in Fig. 3b, where four θC become smaller and two θC become larger. Accordingly, the bond angle distribution in Fig. 5b exhibits a double-peak structure when θC < 120∘ and a single-peak structure when θC > 120∘ at 600 fs. The bond angle distribution at 900 fs is similar to that at 300 fs. Therefore, the coherent vibronic pseudorotation leads to the long-period change of bond-angle distribution, which is measured by the momentum-angle distribution from the three-body Coulomb explosion imaging.

a Simulated temporal evolution of bond angle distribution of benzene cation, convolved with a Gaussian function corresponding to instrument response function. θC is the bond angle of three neighboring C atoms in benzene C1 − C2 − C3. The black dashed lines indicate the temporal change of the bond angle distribution peaks. b Bond angle distributions of benzene cation at 300 fs, 600 fs and 900 fs. The schematic geometries and the displacement vectors of C atoms are shown in the insets of (b), where the change of bond angles are exaggerated for visual convenience. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To conclude, we characterized a coherent vibronic pseudorotation of photoionized benzene induced by the Jahn-Teller coupling and quantum beating of vibronic states. The pseudorotation is probed by the channel-specified time-resolved Coulomb explosion imaging method, which exhibits a ~600 fs long-period temporal oscillations of the ion yield as a function of the pump-probe time delay. Furthermore, we achieved a real-time, direct visualization of the pseudorotation by capturing its transient structural evolution accompanying the coherent wavepacket dynamics between vibronic states. Our results provide a new avenue to understand the spontaneous symmetry-breaking and coherent vibronic dynamics in polyatomic molecules.

Methods

Experimental methods

Briefly, an amplified Ti:Sapphire laser is used to produce a linearly polarized laser pulse (800 nm, 1 kHz). A Mach–Zehnder interferometer is employed to achieve the pump-probe measurement. The output laser pulse is split into pump and probe beams. A translation stage is used to control the time delay between the pump and probe pulses. The polarization of the pump pulse is kept parallel to the time-of-flight (TOF) axis, while the elliptically polarized probe pulse is used to ensure the dominance of the direct strong field ionization process and reduce the contributions from electron recollisions50,51. The estimated intensities of pump and probe pulses are 200 TW/cm2 and 250 TW/cm2, respectively. Benzene vapor at room temperature is introduced into the chamber through supersonic expansion seeded with Ar. The molecular ionization and fragmentation induced by the laser pulses are studied by the cold target recoil ion momentum spectroscopy (COLTRIMS)52,53,54,55. The produced ions are detected in coincidence by time- and position-sensitive detectors through a uniform electric field formed by a set of electrode plates, and their three-dimensional momentum vector can be extracted56. In the ion-ion coincidence measurement, the count rates for the ions are 0.075/pulse. The absolute experimental peak intensity is roughly estimated by comparing the double ionization yield of Xe with the reference curve firstly, with an error around 20%. The cross-correlation of the pump-probe pulse is ~80 fs.

To extract the oscillation signal from the ion yield of the \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{2+}\) channel, as shown in Fig. 1d, we fit the yield curve with a decaying oscillatory function combined with a Gaussian. This approach allows us to determine the oscillation signal’s period and decay time constant. The C+ + C+ channel (Fig. 1e) and the C+ + C+ + C+ channel (Fig. 4b), both show a significant enhancement with a distinct peak at time zero, followed by a decaying tail and a characteristic long-period oscillation. To isolate the oscillatory component, we fit the ion yield using an exponential decay function, then subtract the fitted function from the raw experimental data. For this oscillatory component, we also apply a decaying oscillatory function fit to determine the oscillation period and the decay time of the oscillation amplitude. This analysis enables us to use Fourier transformation, as shown in Fig. 2, to accurately determine the oscillation frequency without interference from the initial decay profile. It also helps precisely identify the peaks and troughs of the long-period oscillation shown in Fig. 4c, which is crucial for analyzing the structural dynamics in pseudorotation (see Supplementary Note 6 for detailed formulas of the fitting functions).

Quantum wavepacket dynamics simulation

To understand the dynamics of the benzene cation initiated by the pump pulse, we performed wavepacket dynamics simulations using the multi-configurational time-dependent Hartree (MCTDH) method40, based on a multistate vibronic coupling Hamiltonian model of \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{+}\)23,24. The Hamiltonian includes the five lowest electronic states of the cation. The vibrational modes included in the Hamiltonian model are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. The vibrational mode Q18 of E2g symmetry, which is important for the ~600 fs vibronic motion, is an active mode for both the JT effect of \({\tilde{D}}^{2}{E}_{1u}\) state and the PJT coupling between \({\tilde{D}}^{2}{E}_{1u}\) and \({\tilde{E}}^{2}{B}_{2u}\) states (see Supplementary Note 4 of SM for detailed symmetry analysis).

Data availability

Source data are provided via Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30675734).

Code availability

The MCTDH input files used in this study, which we used to simulate the wavepacket dynamics of benzene cation, are available in via Figshare (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30675734).

References

Jha, A. et al. Unraveling quantum coherences mediating primary charge transfer processes in photosystem Ⅱ reaction center. Sci. Adv. 10, 1312 (2024).

Matselyukh, D. T., Despré, V., Golubev, N. V., Kuleff, A. I. & Wörner, H. J. Decoherence and revival in attosecond charge migration driven by non-adiabatic dynamics. Nat. Phys. 18, 1206–1213 (2022).

Timmers, H. et al. Coherent electron hole dynamics near a conical intersection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 113003 (2014).

Gaynor, J. D., Sandwisch, J. & Khalil, M. Vibronic coherence evolution in multidimensional ultrafast photochemical processes. Nat. Commun. 10, 5621 (2019).

Keeler, D., Schnappinger, T., Vivie-Riedle, R. & Mukamel, S. Visualizing conical intersection passages via vibronic coherence maps generated by stimulated ultrafast x-ray raman signals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 24069–24075 (2020).

Arnold, C., Vendrell, O., Welsch, R. & Santra, R. Control of nuclear dynamics through conical intersections and electronic coherences. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 123001 (2018).

Galbraith, M. et al. Few-femtosecond passage of conical intersections in the benzene cation. Nat. Commun. 8, 1018 (2017).

Tran, T., Worth, G. A. & Robb, M. A. Control of nuclear dynamics in the benzene cation by electronic wavepacket composition. Commun. Chem. 4, 48 (2021).

Zinchenko, K. S. et al. Sub-7-femtosecond conical-intersection dynamics probed at the carbon K-edge. Science 371, 489–494 (2021).

Chang, Y.-P. et al. Electronic dynamics created at conical intersections and its dephasing in aqueous solution. Nat. Phys. 21, 137–145 (2024)

Rather, S. R., Fu, B., Kudisch, B. & Scholes, G. D. Interplay of vibrational wavepackets during an ultrafast electron transfer reaction. Nat. Chem. 13, 70–76 (2021).

Paterson, M. J., Bearpark, M. J., Robb, M. A., Blancafort, L. & Worth, G. A. Conical intersections: a perspective on the computation of spectroscopic Jahn-Teller parameters and the degenerate ’intersection space’. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7, 2100–2115 (2005).

Jahn, H. A. & Teller, E. Stability of polyatomic molecules in degenerate electronic states - I - Orbital degeneracy. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 161, 220 (1937).

Koppel, H., Barentzen, H. The Jahn-Teller Effect: Fundamentals and Implications for Physics and Chemistry (Springer, 2009).

Bersuker, I.B. The Jahn-Teller Effect (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Ma, Y., Sette, F., Meigs, G., Modesti, S. & Chen, C. Breaking of ground-state symmetry in core-excited ethylene and benzene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 63, 2044 (1989).

Höchli, U. & Müller, K. A. Observation of the Jahn-Teller splitting of three-valent d7 ions via Orbach relaxation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 12, 730–733 (1964).

Li, M. et al. Ultrafast imaging of spontaneous symmetry breaking in a photoionized molecular system. Nat. Commun. 12, 4233–4233 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Ultrafast imaging of Jahn-Teller distortion and the correlated proton migration in photoionized cyclopropane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 10443–10450 (2024).

Ridente, E. et al. Femtosecond symmetry breaking and coherent relaxation of methane cations via x-ray spectroscopy. Science 380, 713–717 (2023).

Higgs, P. W. Broken symmetries and the masses of gauge bosons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 13, 508 (1964).

Lindner, R., Müller-Dethlefs, K., Wedum, E., Haber, K. & Grant, E. On the shape of \({{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{6}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}^{+}\). Science 271, 1698–1702 (1996).

Döscher, M., Köppel, H. & Szalay, P. G. Multistate vibronic interactions in the benzene radical cation. I. Electronic structure calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 117, 2645–2656 (2002).

Köppel, H., Döscher, M., Bâldea, I., Meyer, H.-D. & Szalay, P. G. Multistate vibronic interactions in the benzene radical cation. II. Quantum dynamical simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 117, 2657–2671 (2002).

Muller-Dethlefs, K. & Peel, J. B. Calculations on the Jahn-Teller configurations of the benzene cation. J. Chem. Phys. 111, 10550–10554 (1999).

Signorell, R. & Merkt, F. PFI-ZEKE photoelectron spectra of the methane cation and the dynamic Jahn-Teller effect. Faraday Discuss. 115, 205–228 (2000).

Jacovella, U., Wörner, H. J. & Merkt, F. Jahn-Teller effect and large-amplitude motion in \({{{{\rm{CH}}}}}_{4}^{+}\) studied by high-resolution photoelectron spectroscopy of CH4. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 343, 62–75 (2018).

Trushin, S., Fuss, W. & Schmid, W. Conical intersections, pseudorotation and coherent oscillations in ultrafast photodissociation of group-6 metal hexacarbonyls. Chem. Phys. 259, 313–330 (2000).

Kowalewski, P., Frey, H.-M., Infanger, D. & Leutwyler, S. Probing the structure, pseudorotation, and radial vibrations of cyclopentane by femtosecond rotational raman coherence spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 11215–11225 (2015).

Sax, A. F. On pseudorotation. Chem. Phys. 349, 9–31 (2008).

Hands, I. D., Dunn, J. L. & Bates, C. A. Determination of pseudorotation rates in E⊗e Jahn-Teller systems. Phys. Rev. B 73, 014303 (2006).

Koizumi, H. & Bersuker, I. B. Multiconical intersections and nondegenerate ground state in E⊗e Jahn-Teller systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 3009 (1999).

Chen, T.-T., Du, M., Yang, Z., Yuen-Zhou, J. & Xiong, W. Cavity-enabled enhancement of ultrafast intramolecular vibrational redistribution over pseudorotation. Science 378, 790 (2022).

Paoloni, L. & Maris, A. Interplay of rotational and pseudorotational motions in flexible cyclic molecules. J. Phys. Chem. A 125, 4098–4113 (2021).

Vacher, M., Mendive-Tapia, D., Bearpark, M.J., Robb, M.A. Electron dynamics upon ionization: control of the timescale through chemical substitution and effect of nuclear motion. J. Chem. Phys. 142, 094105 (2015)

Neville, S. P., Stolow, A. & Schuurman, M. S. Formation of electronic coherences in conical intersection-mediated dynamics. J. Phys. B 55, 044004 (2022).

Mi, X. et al. Geometric phase effect in attosecond stimulated X-ray Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 127, 3608–3613 (2023).

Pan, S. et al. Clocking dissociative above-threshold double ionization of H2 in a multicycle laser pulse. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 063201 (2021).

Ji, Q. et al. Timing dissociative ionization of H2 using a polarization-skewed femtosecond laser pulse. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 233202 (2019).

Beck, M. H., Jäckle, A., Worth, G. A. & Meyer, H.-D. The multiconfiguration time-dependent Hartree (MCTDH) method: a highly efficient algorithm for propagating wavepackets. Phys. Rep. 324, 1–105 (2000).

Yang, Y. et al. H2 formation via non-Born-Oppenheimer hydrogen migration in photoionized ethane. Nat. Commun. 14, 4951 (2023).

Colbert, D. T. & Miller, W. H. A novel discrete variable representation for quantum mechanical reactive scattering via the S-matrix Kohn method. J. Chem. Phys. 96, 1982–1991 (1992).

Fushitani, M. et al. Time-resolved photoelectron imaging of complex resonances in molecular nitrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 154, 144305 (2021).

Boll, R. et al. X-ray multiphoton-induced Coulomb explosion images complex single molecules. Nat. Phys. 18, 423–428 (2022).

Mishra, D. et al. Direct tracking of H2 roaming reaction in real time. Nat. Commun. 15, 6656 (2024).

Lam, H. V. S. et al. Differentiating three-dimensional molecular structures using laser-induced coulomb explosion imaging. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 123201 (2024).

Madsen, C. B. et al. Manipulating the torsion of molecules by strong laser pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 073007 (2009).

Hansen, J. L. et al. Control and femtosecond time-resolved imaging of torsion in a chiral molecule. J. Chem. Phys. 136, 204310 (2012).

Jahnke, T. et al. Direct observation of ultrafast symmetry reduction during internal conversion of 2-thiouracil using coulomb explosion imaging. Nat. Commun. 16, 2074 (2025).

Alnaser, A. S. et al. Rescattering double ionization of D2 and H2 by intense laser pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 163002 (2003).

Wang, Z. et al. Directly imaging excited state-resolved transient structures of water induced by valence and inner-shell ionisation. Nat. Commun. 14, 5420 (2023).

Dörner, R. et al. Cold target recoil ion momentum spectroscopy: a ’momentum microscope’ to view atomic collision dynamics. Phys. Rep. 330, 95–192 (2000).

Ullrich, J. et al. Recoil-ion and electron momentum spectroscopy: reaction-microscopes. Rep. Prog. Phys. 66, 1463 (2003).

Jin, W. et al. Direct observation on H-elimination enhancement from C2H4 through non-adiabatic process by femtosecond laser induced coulomb explosion. Chin. Phys. Lett. 41, 053101 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Coulomb focusing in attosecond angular streaking. Light Sci. Appl. 13, 250 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Accurate in situ measurement of ellipticity based on subcycle ionization dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 013203 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the Innovation Program for Quantum Science and Technology (Grant No. 2024ZD0300700 (C.W.)), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12525411 (C.W.), 92261201 (C.W., X.R.), 12174009 (Z.L.), 12274179 (C.W.), 12325406 (X.R.), 12134005 (D.D.), 12234002 (Z.L.) and 92250303 (Z.L.)), the National Key R&D Program (Grant No. 2023YFA1406801 (Z.L.)), and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. Z220008 (Z.L.)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.W. conceived the experiments, Z.L. (Zejin Liu), X.L., S.Z., L.W., L.H., J.Z., X.R., D.Z. and D.D. conducted the measurements, Z.L. (Zejin Liu), M.Z., and T.Z. prepared the figures. M.Z., T.Z., and Z.L (Zheng Li). provided the calculations. Z.L. (Zejin Liu), M.Z., T.Z., Y.Y., A.K., O.V., K.U., Z.L. (Zheng Li), and C.W. prepared and revised the manuscript. All authors participated in the scientific discussions and in the revisions of the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Zhang, M., Zhou, T. et al. Capturing coherent pseudorotation through conical intersection in photoionized benzene. Nat Commun 17, 874 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67594-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67594-8