Abstract

Metasurfaces supporting bound states in the continuum (BIC) can be leveraged as lasing platforms, offering ultra-compact and highly coherent light sources. Although designs using low-index polymers that do not require etching have been demonstrated and shown to possess remarkably high quality factors for free-space radiation, these have been so far limited to passive designs. Here, we report on highly coherent BIC-based lasing, emerging from etch-free metasurfaces that are directly patterned onto organic supramolecular materials consisting of small-molecule, ionic isolation lattices (SMILES). We observe highly directional lasing with a divergence angle of 0.2°, linewidth of 0.04 nm — limited by the spectral resolution of our measurement setup — and a temporal coherence of 20.4 ± 2.4 ps. The reported performance is a direct consequence of the combination of high-quality metasurface designs with the intrinsic uniformity and stability of SMILES, offering a strategy to realize active metasurfaces and organic molecular lasers, superior to alternative approaches based on solution-processable materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metasurfaces enable versatile manipulation of light at subwavelength scales, offering remarkable control over amplitude, phase, direction and polarization1. Their applications extend across a wide range of areas, including flat optics2, holography3, lasers4,5, and quantum communications6. In particular, metasurface lasers based on bound states in the continuum (BIC)4 have drawn considerable interest as they offer compactness, narrow linewidth, high coherence, directionality, wavelength tunability, and scalability5. Metasurface lasers based on traditional III–V semiconductors have demonstrated exceptionally narrow linewidth of lasing emission and ultrahigh quality factor (Q-factor)7,8,9,10, enabled by advanced fabrication techniques and excellent material properties. Beyond this, novel material systems such as transition metal dichalcogenides11, perovskites12, colloidal nanomaterials13,14, and organic materials15,16,17 have also attracted growing attention to realize metasurface lasers owing to their advantages, including solution processability, synthetic tunability, and compatibility with flexible substrates. Nevertheless, these materials have a relatively low refractive index, are difficult to pattern directly, and are generally used only as the active media for pre-fabricated passive structures composed of high-index materials17,18.

Low-refractive-index materials generally exhibit poor light confinement and low diffraction efficiency, making it challenging to design efficient photonic structures19. However, novel metasurface designs have been reported that can achieve ultra-high Q-factors with low-refractive indexes20,21,22. For instance, the metasurface reported by Fang et al.21 achieved Q-factors exceeding one million, leveraging the etch-free process that would be typically required with commonly used polymers. This outcome was achieved with a perturbed multilayer-waveguide configuration and low-loss materials21. Etch-free designs minimize imperfections in fabrication, thereby substantially reducing unwanted scattering losses. However, these demonstrations are passive in nature, and hence require integration with active media to function as light-emitting devices.

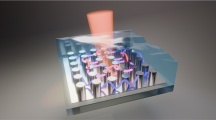

Here, we show a highly coherent, directional, and etch-free molecular metasurface laser utilizing a novel direct patterning approach. We employ small-molecule, ionic isolation lattices (SMILES)23, a newly developed supramolecular material synthesized using self-assembly methods by combining an organic dye with a macrocycle host called cyanostar24. SMILES materials provide extraordinary brightness25 and structural stability by preventing the aggregation and quenching of organic dye molecules. Incorporating SMILES into an e-beam resist allows direct e-beam lithography (EBL) to pattern molecular nanostructures without the etching process, while preserving their brightness and optical properties. Based on this platform, we demonstrate direct EBL fabrication of molecular metasurfaces made of SMILES as shown schematically in Fig.1a. Using optical spectroscopy, we observe lasing at the BIC. The lasing emission exhibits an ultra-narrow linewidth of 0.04 nm (corresponding to 103 μeV), which reaches the spectral resolution limit of our measurement setup. Moreover, the lasing emission is highly directional with a divergence angle of 0.2°. To further characterize the coherence properties, we measure the temporal coherence of the lasing, revealing a coherence time of 20.4 ± 2.4 ps.

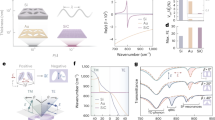

a Schematic of the etch-free molecular metasurface using R3B-SMILES. b Photograph and chemical structures of R3B-SMILES in chlorobenzene solvent. c Photoluminescence intensities of R3B dye (black) and R3B-SMILES (red) films after baking process depending on baking temperature. Error bars represent the standard deviation. d Process of direct patterning of SMILES onto the SiN/SiO2/Si substrate. e Image of the patterned SMILES measured by scanning electron microscope (SEM), optical microscope (OM), and photoluminescence (PL), respectively. The scale bars correspond to 10 μm.

Results

Direct lithography with SMILES

First, we synthesize SMILES by combining rhodamine 3B (R3B) dye and cyanostar in a solvent. To enable direct lithography of the R3B-SMILES using EBL, we incorporate PMMA into the R3B-SMILES solution, shown in Fig. 1b, together with their chemical structures. The detailed synthesis method of the SMILES resist is described in the Methods section. While PMMA is not required for SMILES to function as a bright fluorescent emitter, it has previously been used to control the precise thickness of the SMILES films during the spin-coating process by adjusting the concentration of PMMA26,27. Here, we emphasize that PMMA retains its function as E-beam resist even when mixed with SMILES.

The EBL process typically requires a baking step after resist coating to evaporate the solvent and ensure that the resist functions effectively as an etch mask. PMMA has a glass transition temperature of 105 °C28, and is generally baked at around 180 °C on a hot plate for a few minutes. However, these thermal processing can negatively affect the photophysical properties of traditional organic-based materials29,30,31, making the fabrication of nanostructures using such materials challenging with conventional lithography process. We note that the baking process does not degrade SMILES but rather improves its fluorescence up to a certain temperature. We spin-coat the PMMA containing R3B dye and R3B-SMILES onto substrates and bake them on a hot plate for 5 min at different temperatures. We measure the PL spectra five times at different positions on each sample and averaged the PL peak intensities. Due to sample nonuniformity across positions, the measured PL intensities show slight variations. The PL intensities of baked R3B-SMILES and baked R3B dye resists as a function of baking temperature are shown in Fig. 1c, with error bars indicating the standard deviation. The R3B-SMILES resist exhibits notably stronger PL intensity than R3B dye. For R3B dye resist, the PL intensity decreases monotonically as the baking temperature increases, whereas for R3B-SMILES, the PL intensity increases up to approximately 150 °C. At this temperature, the PL intensity of baked R3B-SMILES resist is about 1.5 times higher than that of the unbaked R3B-SMILES. Beyond this temperature, R3B-SMILES films undergo thermal degradation, leading to a decrease in PL intensity. The cyanostar used in the preparation of the SMILES materials not only provides optimal spacing for organic dyes to prevent aggregation caused quenching but also enhances thermal robustness through structural stability with isolation lattices according to the reported thermal properties23.

The step-by-step process of direct lithography using the SMILES-resist is illustrated in Fig. 1d. First, a SMILES resist thin film is coated on the substrate via spin-coating. Second, the thin film is baked on a hot plate at 150 °C for 3 min. Third, EBL is performed on the SMILES-resist film using a dose value of 300 µC/cm2. Fourth, the development process is carried out using a PMMA developer, in which the sample is immersed for 1 min. Scanning electron microscope (SEM), optical microscope, and PL images of the directly patterned SMILES-resist showing the logo of the City College of New York are displayed in Fig. 1d. This shows that even with the SMILES mixed in, the patterned structure shows feature sizes on the order of 10 nm, a typical fabrication resolution of PMMA, while maintaining the bright PL of the SMILES material.

Structural design and BIC in etch-free molecular metasurface

Our molecular metasurface design is the structure used in ref. 21, but replacing PMMA with SMILES, which has a refractive index similar to PMMA, ~1.5 (See Supplementary Fig. 1 for refractive index data). The unit cell structure of the etch-free molecular metasurface is defined by a periodicity \(a\), and a square hole with side \(L\) (Fig. 2a). We spin coat ~100-nm-thick SMILES on the 100-nm-thick SiN layer on SiO2/Si substrate. Here, the light is effectively trapped at the interface between SMILES and SiN layers21. A SEM image of the fabricated molecular metasurface is shown in Fig. 2b. For the SEM measurement, a thin gold layer (~20 nm) was deposited to prevent surface charging.

a Schematic of the unit cell for molecular metasurfaces. R3B-SMILES is coated on a SiN/SiO2/Si substrate, defined by the period \(a\) and hole size \(L.\) b SEM image of fabricated molecular metasurface under top view. c Calculated electric field distribution within the x-y plane of unit cell in R3B-SMILES layer. The white, dashed square indicates the boundary between R3B-SMILES and air. d Calculated electric field distributions in the x–z plane for the bound state in the continuum (BIC) mode on the left and off-BIC mode on the right. The white dashed lines indicate the material boundaries. e, f Calculated and measured angle-resolved reflectance spectra of molecular metasurface, respectively.

This metasurface is designed to support a symmetry-protected Γ-point (k = 0) BIC, where the radiative coupling is completely suppressed32,33. To visualize the electric field characteristics, we perform finite element method calculations, shown in Fig.2c, d. The calculated electric field of x-y plane in SMILES layer at the Γ-point is shown in Fig.2c. For the BIC, the electric field is strongly confined within the SMILES and SiN layers, confirming its non-radiative characteristic, shown in Fig. 2d (left). In contrast, the off-BIC mode shows distinct field leakage into air and substrate, shown in Fig. 2d (right).

We perform angle-resolved reflectance spectroscopy to measure the photonic dispersion of the SMILES metasurface, and calculate reflectance spectra of the molecular metasurface with \(a=364{nm}\) and \(L=90{nm}\), for TE polarization (Fig. 2e). The lower guided mode resonance (GMR) band vanishes at \(\theta=0\)° (k = 0), indicating the formation of a BIC. The reflectance spectrum measured from the molecular metasurface exhibits a clear GMR band for TE-polarized light and qualitatively matches the calculated spectra, as presented in Fig. 2f. Compared to the metasurface of the same structure made of PMMA only21, the photonic dispersion has the same shape, but the linewidth is broader due to the absorption of SMILES. The dark and broad parabolic dispersion is attributed to Fabry-Perot interference within the thick SiO2 layer, which is independent of the SMILES layer. (See Supplementary Fig. 2) We extract the Q-factors of the two photonic bands from the angle-resolved reflectance spectra. The reflectance spectra were fitted with a Lorentzian function to obtain the peak positions \({E}_{p}\) and linewidths \(\Delta {E}_{p}\), from which the Q-factors were calculated as \(Q={E}_{p}/\Delta {E}_{p}\). For the lower band having the BIC, the Q-factor reaches approximately 1534, measured at \({\theta }_{x}=0.4\)°. In contrast, the upper band exhibits a lower Q-factor of about 600. This difference originates from the broad excitonic absorption centered around 2.2 eV, which increases optical loss and reduced Q factor. Numerical simulations also represent this trend, yielding a theoretical Q-factor on the order of 10³ for the lower band. (See Supplementary Fig. 3 for details.)

BIC lasing in etch-free molecular metasurface

We measure the PL spectrum of the SMILES metasurface using Fourier imaging to investigate the lasing characteristics. We excite the molecular metasurface using a 515 nm (~2.4 eV) fs-pulsed laser with a Gaussian beam of approximately 280 μm diameters (Fig. 3a). A PL image obtained from a large area of the molecular metasurface region is presented in Fig. 3b, while PL spectra measured below and above the lasing threshold are provided in Fig. 3c, d, respectively. In the weak pump power regime, PL spectrum exhibits a broad distribution of GMR band (Fig. 3c). As the pump power increases, PL spectrum exhibits the lasing emission with a very narrow linewidth as two distinct spots near \(\theta=0\), at the BIC. Due to the symmetry-protected nature of the Γ-point BIC, radiation is completely suppressed at k = 0, while lasing emission emerges from near-Γ states with finite radiative coupling. Notably, the measured lasing emission appears at an angle of under 0.2° in the momentum space, indicating that it is highly directional along the out-of-plane axis of the metasurface.

a Microscopic image of the etch-free molecular metasurface, outlined by the white, dashed lines, showing the pump laser. b Photoluminescence (PL) image from the molecular metasurface. c, d Angle-resolved PL spectra of the molecular metasurface below and above threshold power, respectively. Above the threshold power, PL spectrum shows a narrow emission at the BIC state near \({\theta }_{x}=0\). e PL spectra as a function of the pulse fluence. Inset shows PL spectrum of BIC lasing at threshold power, measured with higher spectral resolution. f pulse fluence dependence of PL peak intensity (black squares) and linewidth (blue circles) of BIC lasing.

The threshold of pulse fluence Pth for lasing is found to be approximately 2.08 μJ/cm², corresponding to a pulse energy of 1.28 nJ per pulse and an instantaneous pump power of about 6.4 kW. The angle-integrated PL spectra as a function of pulse fluence is shown in Fig. 3e. As the pulse fluence increases, a sharp peak suddenly emerges above Pth. We measure the PL spectrum near the threshold power by narrowing the entrance slit of the spectrometer as much as possible. The narrowest linewidth of the lasing emission obtained by fitting is 0.031 \(\pm\) 0.0005 nm, which is on the order of the instrument limit of our measurement setup (~0.04 nm), as shown in the inset of Fig. 3e.

We plot the pulse fluence dependence of PL peak intensity (black square), and linewidth (blue circle) of lasing emission in Fig. 3f. The PL peak intensity shows nonlinear behavior, while the linewidth of PL emission decreases abruptly above Pth, as clear evidence of lasing behavior (We also obtained data over a wider pump-power range, provided in the Supplementary Fig. 4). A slight blueshift of the PL peak is observed above the threshold, originating from Kerr-type nonlinearities and saturation of molecular optical transitions inherent to the organic molecules34.

We also measure the coherence properties of lasing emission from the SMILES metasurface using a Michelson interferometer and a retroreflector. A superimposed PL image from the interferometer is presented in Fig. 4a. The PL emissions from each arm are marked by white dashed circles, which also indicate the pumped regions. Here we excite the metasurface with a beam diameter of ~ 50 μm. Below Pth, the superimposed PL image represents simply the sum of two PL images, showing no interference features. In contrast, above Pth, the superimposed PL image exhibits clear fringes in the overlapped region, indicating coherent emission. Moreover, fringe patterns are observed beyond the pumping area. The lasing emissions appear broad in both vertical and horizontal directions, which are the leaked emissions from the propagating GMRs. We observe that the lasing emission propagates beyond 100 μm (See Supplementary Fig. 5).

a Superimposed PL images measured with Michelson interferometer, below the threshold power. The top left dashed circle outlines the PL reflected from the retroreflector, whereas the bottom right dashed circle encloses the PL reflected from the mirror. b Superimposed PL images for power above threshold, showing a clear fringe pattern in the overlap region. c Visibility of the interference fringes as a function of the delay time \(\tau\) between the two arms of the Michelson interferometer, showing the BIC lasing temporal coherence as the full width half-maximum of the peak. The experimental data are shown as black squares, and the fitting curve is displayed as a red solid line. The extracted coherence time from the fitting is 20.4 ps. The inset images show interference images measured at τ = 0 ps and τ = –26.4 ps. The white scale bars correspond to 10 μm.

We evaluate the temporal coherence of the lasing emission by changing the relative optical path length between the two interferometer arms. The visibility of the interference as a function of the time delay τ is shown in Fig. 4c. The measured data fit with a Gaussian curve, yielding a temporal coherence time of 20.4 ± 2.4 ps. The interference fringes are clearly visible at τ = 0 ps but almost disappear at τ = –26.4 ps, as shown in the insets, indicating the loss of temporal coherence with increasing delay time.

Polarization vortex of BIC

We investigate the topological properties of BICs in momentum space using polarization-resolved measurements. PL images in momentum space below Pth with two orthogonal linear polarizations are shown in Fig. 5a, b, where the red arrows indicate the polarization direction. The PL images show broad intensity distributions in all angles, with weakly visible photonic modes. However, above Pth, two-lobe emission patterns are observed (Fig. 5c–f). As the measured polarization angle is rotated, the orientation of two lobes also rotates in momentum space. Without the linear polarizer, the PL emission exhibits a donut-shaped pattern above the threshold power (See Supplementary Fig. 6). These data present the vortex feature of BICs, consistent with previously reported results for BIC lasing12,33,35. To further reveal the topological characteristics of the BIC, we calculated the polarization vortex in momentum space, as shown in Fig. 5g. The phase singularity around Γ point indicates a topological charge, confirming the vortex nature of the BIC in momentum space.

a, b Angle-resolved photoluminescence (PL) images below the threshold power measured through a linear polarizer oriented along the direction indicated by red arrows. c, d, e, f Angle-resolved PL images above the threshold power. As the linear polarizer in readout rotates, the intensity distribution of the BIC state rotates along with it, indicating the polarization vortex feature of BIC state. Inset images show an enlarged view of the data near the center. g Calculated map of the azimuthal angle of the state of polarization at the BIC, in momentum space.

Discussion

In this work, we demonstrate highly coherent lasing emission in an etch-free molecular metasurface. We emphasize that our lasing emission displays the narrowest linewidth for BIC lasing using solution-processable materials (See Supplementary Table 1). There are two key factors enabling such a narrow lasing linewidth, achieved despite SMILES being all-organic molecular systems. First, our metasurface design can support very high Q-factors, enabling the onset of BICs with ultra-narrow linewidths. These are comparable to the linewidths reported in inorganic material-based BIC lasing, where linewidths below 0.1 nm have been demonstrated7. Second, we emphasize that SMILES materials produce nanostructures that have a clear surface morphology, free of severe roughness originating during the lithography process. This reduces the impact that SMILES materials have on the EBL processing and leads to highly coherent lasing emission. We also assume that the structural stability provided by SMILES materials contributes to the observed coherent lasing emission as it lowers disorder and enables uniform and high quantum yields. Notably, a SMILES-based polariton laser has also demonstrated temporal coherence on the order of 10 ps27.

Direct patterning techniques for fabricating etch-free nanostructures have been developed over the past few decades36,37,38,39. In particular, approaches using conventional lithography have achieved remarkable progress using solution-based materials, including inorganic nanomaterials40, colloidal quantum dots41,42, perovskites43 and fluorescent dyes44. The work reported here demonstrates that our direct patterning approach can achieve lasing applications using organic dyes in a solid form and it can be extended to other wavelengths, using the large number of available organic dyes that are compatible with the SMILES approach23,45,46.

Our direct lithography can be used to easily realize complex three-dimensional nanostructures with grayscale EBL47. This technique enables precise control of the thickness of the SMILES resist by modulating the electron beam dose, resulting in continuous, non-binary patterns without additional lithographic processes. Consequently, this grayscale EBL has the great potential to enable the fabrication of three-dimensional photonic structures, such as stepped grating48 or stepped metasurface49, using SMILES materials. We believe that our approach paves the way for the next generation of nanophotonic devices, providing a practical and scalable solution for advanced photonic applications.

Methods

Sample fabrication

To synthesize R3B-SMILES resist, we dissolve the rhodamine 3B dye as the perchlorate (ClO4–) salt and cyanostar (Halophore, Inc.) with a molar ratio of 1:2 in a PMMA C2 solution (2% w/w PMMA in chlorobenzene, Kayaku Chem). The solution undergoes 48 h of stirring at room temperature.

For measuring baking-temperature dependence, R3B-SMILES and R3B dye films are prepared by spin-coating on SiO₂ substrates at 2000 RPM for 60 s. The spin-coated samples are then placed on a hot plate at various temperatures for five minutes.

To make a metasurface structure, we spin-coat the SMILES-resist on a SiN/SiO2/Si substrate at 2000 RPM for 60s. The thicknesses of SiN and SiO2 are 100 nm and 1470 nm, respectively. We place the spin-coated SMILES resist substrate on a hot plate at 150 °C for 3 min for thermal annealing. We write the metasurface patterns using E-beam lithography, followed by the development process for 1 min.

Simulation

We perform rigorous coupled-wave analysis with the Lorentz oscillator model to calculate reflectance spectra of the molecular metasurfaces. We assume the permittivity of SMILES resist using the following Lorentz oscillator model: \(\varepsilon \left(E\right)={\varepsilon }_{\infty }+\mathop{\sum }_{j}\frac{{f}_{j}}{{E}_{j}^{2}-{E}^{2}-i{\gamma }_{j}E}\) where E is an energy, \({\varepsilon }_{\infty }\) is the high-frequency dielectric constant, \({E}_{j}\) is resonance energy of the j-th oscillator, \({f}_{j}\) is oscillator strength of the j-th oscillator, \({\gamma }_{j}\) is damping coefficient of the j-th oscillator, ε∞ = 2.5, E1 = 2.19 eV, E2 = 2.36 eV, E3 = 3.5 eV, f1 = 0.036 eV2, f2 = 0.01 eV2, f3 = 0.04 eV2, γ1 = 0.12 eV, γ2 = 0.19 eV, γ3 = 0.5 eV. We assume the refractive index of SiO2 as n = 1.45, the index of SiN as n = 2.0, and the index of silicon n = 4.0 in the calculation.

We also perform three-dimensional finite element method (FEM) simulations using COMSOL Multiphysics to calculate the electric field distributions of the molecular metasurface and polarization vortex of BIC. The simulations are carried out with the eigenfrequency solver module.

Measurements

Optical measurement and interferometry: angle-resolved reflectance measurements were conducted using a broadband tungsten halogen lamp. The reflected signal was collected using a 5\(\times\) objective lens with numerical aperture 0.15. The signal was measured with a spectrometer (Princeton Instruments) and a charge-coupled device camera (Princeton Instruments). PL spectrum measurements were conducted using a fs-pulsed laser (Light Conversion), emitting at 515 nm wavelength and 10 kHz repetition rate.

PL spectra of R3B-SMILES and R3B dye on SiO2 substrates as a function of baking temperature were measured under identical excitation power and exposure time. Five different positions on each sample were measured, the PL peak intensities were averaged, and the standard deviation of these values was obtained.

The excitation beam had a Gaussian profile with a diameter of approximately 280 µm on the sample surface. For the angle-resolved PL spectrum measurements, the entrance slit of the spectrometer was set to 50 µm, while a narrower slit width of 10 µm was used to achieve higher spectral resolution. PL spectra and images were collected using a 5\(\times\) objective lens with numerical aperture 0.15. A 550 nm long pass filter was used to eliminate the laser signal in PL measurement. Interference fringes were measured with a Michelson interferometer and a retroreflector, where the excitation beam was focused to a diameter of approximately 50 µm. Visibility is calculated as \(V=\frac{\left({I}_{\max }-{I}_{\min }\right)}{\left({I}_{\max }+{I}_{\min }\right)}\), where maximum intensity \({I}_{\max }\) and minimum intensity \({I}_{\min }\) within the interference fringes, respectively. One arm of the interferometer was placed on a computer-controlled stage (Thorlabs), enabling measurement of temporal coherence by varying the optical path length. The resulting visibility as a function of delay time was fitted with a Gaussian profile to extract the coherence time. The PL images in momentum space were measured with an excitation beam of approximately 50 µm diameter.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All source data used in this study are available in the link below https://figshare.com/s/297ae919e3938bd9dcf7.

References

Yu, N. & Capasso, F. Flat optics with designer metasurfaces. Nat. Mater. 13, 139–150 (2014).

Wang, S. et al. A broadband achromatic metalens in the visible. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 227–232 (2018).

Lin, J., Genevet, P., Kats, M. A., Antoniou, N. & Capasso, F. Nanostructured holograms for broadband manipulation of vector beams. Nano Lett 13, 4269–4274 (2013).

Kodigala, A. et al. Lasing action from photonic bound states in continuum. Nature 541, 196–199 (2017).

Xie, Y.-Y. et al. Metasurface-integrated vertical cavity surface-emitting lasers for programmable directional lasing emissions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 125–130 (2020).

Stav, T. et al. Quantum entanglement of the spin and orbital angular momentum of photons using metamaterials. Science 361, 1101–1104 (2018).

Yu, Y. et al. Ultra-coherent Fano laser based on a bound state in the continuum. Nat. Photonics 15, 758–764 (2021).

Hwang, M.-S. et al. Ultralow-threshold laser using super-bound states in the continuum. Nat. Commun. 12, 4135 (2021).

Ardizzone, V. et al. Polariton Bose–Einstein condensate from a bound state in the continuum. Nature 605, 447–452 (2022).

Ren, Y. et al. Low-threshold nanolasers based on miniaturized bound states in the continuum. Sci. Adv. 8, eade8817 (2022).

Barth, I. et al. Lasing from a large-area 2D material enabled by a dual-resonance metasurface. ACS Nano 18, 12897–12904 (2024).

Huang, C. et al. Ultrafast control of vortex microlasers. Science 367, 1018–1021 (2020).

Wu, M. et al. Room-Temperature Lasing in Colloidal Nanoplatelets via Mie-Resonant Bound States in the Continuum. Nano Lett 20, 6005–6011 (2020).

Wu, M. et al. Bound State in the Continuum in Nanoantenna-Coupled Slab Waveguide Enables Low-Threshold Quantum-Dot Lasing. Nano Lett 21, 9754–9760 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Low-Threshold Bound State in the Continuum Lasers in Hybrid Lattice Resonance Metasurfaces. Laser Photonics Rev 15, 2100118 (2021).

Azzam, S. I. et al. Single and Multi-Mode Directional Lasing from Arrays of Dielectric Nanoresonators. Laser Photonics Rev 15, 2000411 (2021).

Zhai, Z. et al. Multimode Vortex Lasing from Dye–TiO2 Lattices via Bound States in the Continuum. ACS Photonics 10, 437–446 (2023).

Deng, H. et al. Chiral lasing enabled by strong coupling. Sci. Adv. (2025).

Gong, Y. & Vučković, J. Photonic crystal cavities in silicon dioxide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 031107 (2010).

Huang, L. et al. Ultrahigh-Q guided mode resonances in an All-dielectric metasurface. Nat. Commun. 14, 3433 (2023).

Fang, J. et al. Million-Q free space meta-optical resonator at near-visible wavelengths. Nat. Commun. 15, 10341 (2024).

Fang, C. et al. Multiple High- Q Optical Modes in a Polymer-Lithium Niobate Integrated Metasurface. Laser Photonics Rev 18, 2300900 (2024).

Benson, C. R. et al. Plug-and-Play Optical Materials from Fluorescent Dyes and Macrocycles. Chem 6, 1978–1997 (2020).

Lee, S., Chen, C.-H. & Flood, A. H. A pentagonal cyanostar macrocycle with cyanostilbene CH donors binds anions and forms dialkylphosphate [3]rotaxanes. Nat. Chem. 5, 704–710 (2013).

Kacenauskaite, L., Stenspil, S. G., Olsson, A. H., Flood, A. H. & Laursen, B. W. Universal Concept for Bright, Organic, Solid-State Emitters─Doping of Small-Molecule Ionic Isolation Lattices with FRET Acceptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 19981–19989 (2022).

Deshmukh, P. et al. Plug-and-Play Molecular Approach for Room Temperature Polariton Condensation. ACS Photonics 11, 348–355 (2024).

Choi, D., Zachariah, S., Yadav, R. K. & Menon, Vinod. M. Highly Coherent Room-temperature Molecular Polariton Condensates. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2500086 (2025).

Brandrup, J., Immergut, E. H., Grulke, E. A., Abe, A. & Bloch, D. R. Polymer Handbook. 89 (Wiley New York, 1999).

Estrada-Pérez, C. E., Hassan, Y. A. & Tan, S. Experimental characterization of temperature sensitive dyes for laser induced fluorescence thermometry. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 82, 074901 (2011).

Vu, T. T., Méallet-Renault, R., Clavier, G., Trofimov, B. A. & Kuimova, M. K. Tuning BODIPY molecular rotors into the red: sensitivity to viscosity vs. temperature. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 2828–2833 (2016).

Rana, M. S., Wang, X. & Banerjee, A. An Improved Strategy for Fluorescent Tagging of Membrane Proteins for Overexpression and Purification in Mammalian Cells. Biochemistry 57, 6741–6751 (2018).

Zhen, B., Hsu, C. W., Lu, L., Stone, A. D. & Soljačić, M. Topological Nature of Optical Bound States in the Continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 257401 (2014).

Wang, B. et al. Generating optical vortex beams by momentum-space polarization vortices centred at bound states in the continuum. Nat. Photonics 14, 623–628 (2020).

Yagafarov, T. et al. Mechanisms of blueshifts in organic polariton condensates. Commun. Phys. 3, 18 (2020).

Doeleman, H. M. et al. Experimental observation of a polarization vortex at an optical bound state in the continuum. Nat. Photonics 12, 397–401 (2018).

Hon, K. K. B., Li, L. & Hutchings, I. M. Direct writing technology—Advances and developments. CIRP Ann 57, 601–620 (2008).

Baek, S. & Son, J. S. Recent Advances in Direct Optical Patterning of Inorganic Materials and Devices. Adv. Phys. Res. 3, 2300069 (2024).

Guo, W. et al. Direct Photolithography Patterning of Quantum Dot-Polymer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2310338 (2024).

Liang, L. et al. Patterning Technologies for Metal Halide Perovskites: A Review. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2200419 (2023).

Wang, Y., Pan, J.-A., Wu, H. & Talapin, D. V. Direct Wavelength-Selective Optical and Electron-Beam Lithography of Functional Inorganic Nanomaterials. ACS Nano 13, 13917–13931 (2019).

Hahm, D. et al. Direct patterning of colloidal quantum dots with adaptable dual-ligand surface. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 952–958 (2022).

Kulkarni, S. P., Pathak, A. K., Krishnaswamy, S. & Aydin, K. High-Q Emission from Colloidal Quantum Dots Embedded in Polymer Quasi-BIC Metasurfaces. Nano Lett 25, 1653–1659 (2025).

Liu, D. et al. Direct optical patterning of perovskite nanocrystals with ligand cross-linkers. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm8433 (2022).

Kaiser, C. et al. Fluorescent E-beam and Photolithographic Resists for Upconversion. Micro-Nano-Integr. 7th GMM-Workshop Dortm. Ger. 1–6 (2018).

Stenspil, S. G. et al. Supramolecular Control of Helicene Circularly Polarized Luminescence Emitters in Molecular Solids and Bright Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202412320 (2024).

Stenspil, S. G., Chen, J., Liisberg, M. B., Flood, A. H. & Laursen, B. W. Control of the fluorescence lifetime in dye based nanoparticles. Chem. Sci. 15, 5531–5538 (2024).

Mortelmans, T. et al. Grayscale e-beam lithography: Effects of a delayed development for well-controlled 3D patterning. Microelectron. Eng. 225, 111272 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Ultralow-loss optical interconnect enabled by topological unidirectional guided resonance. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn4372 (2024).

Kang, M., Xiao, M. & Chan, C. T. Janus Bound States in the Continuum with Asymmetric Topological Charges. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 013805 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This paper is based predominantly on work conducted at the City University of New York and University of Washington and supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) Science and Technology Center (STC) for Integration of Modern Optoelectronic Materials on Demand (IMOD) under Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-2019444 (S.Z., J.F., A.M., V.M.M.). D.C. was supported by NSF QExpand grant OMA-2328993. R.K. and A.A. were supported by the US Air Force Office of Scientific Research-MURI Grant FA9550-22-1-0317. A.F. was supported by NSF DMR-2118423 and J.C. and B.W.L. were supported by Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF22OC0073582). A.A. was also supported by the Simons Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.C. conceived the experimental idea. D.C. and V.M.M. designed and conceptualized this work. D.C. and J.F. developed the sample design and carried out simulations supervised by A.M and A.A. Samples were fabricated by D.C., S.Z., and R.K. D.C. and S.Z. conducted optical experiments and data collection. SMILES was developed by A.H.F., B.L. and J.C. D.C. and S.Z. performed all data analysis and visualization. D.C. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors and supervised the project with V.M.M. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

B.W.L. and A.H.F. hold a patent on SMILES materials, and are cofounders of Halophore, Inc. B.W.L., A.H.F., D.C. and V.M.M. have a patent pending. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Kirill Koshelev and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, D., Zachariah, S., Kaurav, R. et al. Highly coherent organic lasing based on etch-free metasurface. Nat Commun 17, 906 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67628-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67628-1