Abstract

Surgical tasks in small tortuous lumens demand interventional instruments with controllable mechanical adaptability. However, current microcatheters lack a non-disruptive, integration-ready strategy for dynamic stiffness tuning—critical for meeting the divergent mechanical demands for compliant steering and stable advancement. Here, we present a microrobotic system based on a helix-shaped magnetic soft microrobot (Helixoft) that compatibly integrates with commercial microcatheters (down to 300 μm in diameter), enabling continuous stiffness tuning (up to 40-fold) and precise steering, both controlled magnetically, free of any other potentially harmful stimuli. Stiffness tuning and active steering are independently controlled via a decoupled control strategy by the helical motion and torque-driven bending of independent microrobot components. This stiffness and structure reconfiguration allow the integrated microcatheter to perform large-angle navigation, precision payload delivery, and localised tissue biopsy without unintended buckling or tissue damage. We validate the system in both ex-vivo oviduct biopsy and in-vivo drug delivery to the fourth-generation bronchi of live pigs. The Helixoft system provides a minimally disruptive robotic strategy for the mechanical reconfiguration in confined and sensitive luminal environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has significantly advanced modern clinical practice, offering reduced trauma, fast recovery, and minimal scarring, particularly for interventions within small lumens, such as blood vessels, bronchi, and oviducts1,2. Microcatheters are indispensable tools for these procedures3,4,5, enabling precise diagnosis and treatment interventions, such as biopsy6,7,8, stent placement9,10 and reagent delivery11,12,13. For performing complex tasks in intricate and tortuous lumens, microcatheters must achieve precise control over their steerability and compliance adaptability, for effectively manoeuvring through complex paths while maintaining sufficient mechanical stability for performing tissue interactions without causing unintended damage.

Previous efforts to enhance steerability have led to the development of surgical catheters based on tendon-driven14,15,16,17 and concentric tube structures18,19, as well as conductive20,21,22 and magnetic shape-transformable materials11,23,24,25. Among these devices, magnetically controlled soft catheters have demonstrated distinct advantages, offering precise steerability through the highly penetrable and biosafe actuation mechanism afforded by the magnetic field11,23,26. Various magnetic catheters, featuring functionalities such as active navigation27, light delivery28, thrombus removal29,30, and force sensing31,32, were developed by Nelson et al., Zhao et al., our group, and others. Such magnetic catheters, aligned by the magnetic torque, allow for multi-degree-of-freedom orientation control within absolute spatial coordinates, without the need for antagonistic tendons.

However, most magnetically controlled catheters have been designed with constant stiffness, limiting their adaptability to the dynamic mechanical demands of complex operations. In clinical practice, an effective catheter is desired to remain soft during steering yet sufficiently stiff during advancement33. The soft state facilitates smooth navigation through tortuous lumens, whereas the stiff state prevents buckling during advancement in straight luminal segments. Additionally, catheters equipped with end-effectors, such as biopsy needles34 and graspers11, also need such switchable stiffness states to realise both safe navigation around sensitive tissues and efficient penetration at target sites during procedural tasks35,36. Accordingly, both the navigational and operational performances of microcatheters fundamentally depend on achieving reliable and controllable stiffness tuning.

Stiffness tuning strategies previously reported focused primarily on two approaches: material-based and structure-based strategies. Material-based strategies employed viscosity-tuneable materials, such as magnetorheological37,38,39 and electrorheological fluids40,41,42, or phase-changing materials including shape-memory polymers20,43,44 and low-melting-point alloys12,33,45,46. These materials enabled stiffness tuning in response to magnetic, electrical, or thermal fields. However, their reliance on such intense stimuli raised considerable safety concerns for delicate biological environments, including risks of toxicity, thermal injury, and electrical damage. Additionally, integrating stimulus-delivery elements, such as heaters or electrodes, faces significant fabrication challenges, particularly when miniaturising the microcatheters for applications in small lumens.

Structure-based strategies, such as joint stacking47,48, particle jamming49, layer jamming50, fibre jamming51, sliding sleeve, and concentric tube19,52, were proposed by Yang et al., Zhang et al., and others as more biocompatible alternatives for modulating catheter stiffness. Although these structure-based strategies mitigated safety concerns, such as thermal risks, they involved complex integration processes and inevitably led to increased device size, restricting their applicability in small and delicate anatomical environments.

Moreover, previous catheters based on material- and structure-based strategies were primarily developed with diameters exceeding 2 mm, a compromise size requirement to accommodate bulky actuation components, which in turn restricts their applicability mainly to cardiac and gastrointestinal interventions. To date, downsizing stiffness-variable catheters to diameters approaching 1 mm—a critical threshold for vascular and reproductive system applications—remains a significant challenge3,28,53.

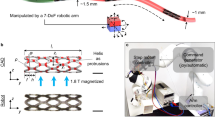

To address these challenges, we present a microrobotic system comprising a helix-shaped magnetic soft microrobot (Helixoft) that seamlessly integrates with commercial microcatheters, to enable continuous stiffness tuning and arbitrary-directional steering, thereby achieving adaptive navigation and controllable tissue penetrability (Fig. 1). The Helixoft microrobot integrates both magnetic responsiveness and mechanical compliance through its constituent components, a rigid magnetic helix and a soft microtube, enabling decoupled control over the stiffness tuning and steering of the integrated microcatheter, based on the material magnetisation–device structure–field pattern triad design. Integrated onto microcatheters with scalable diameters down to 300 μm, the Helixoft enables continuous stiffness tuning across a 40-fold range, superior to previous structure-based strategies that achieve only binary or discrete modulation states. The stiffness tuning and steering processes are solely controlled by low-intensity magnetic fields with no need for thermal, optical, or electrical stimuli that compromise tissue safety or microcatheter integrity. The Helixoft-integrated microcatheter can be also attached with auxiliary microsurgical tools, such as mini-cameras, electrodes, and laser fibres, thereby enabling multimodal surgical functionalities, such as on-board imaging or ablation. Supplementary Table 2 summarises the performance of the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter in comparison with representative variable-stiffness and steerable catheters.

The system comprises four modules: a a Helixoft microrobot; b a robotic catheter manipulator; c a magnetic control module including electromagnetic coils and a permanent magnet mounted on a robotic arm; d an imaging module based on a C-arm computed tomography setup (C-arm CT) and an endoscopic mini-camera. The Helixoft microrobot is mountable onto commercial microcatheters alongside microsurgical tools (e.g., mini-camera, electrode, and fibre). Stiffness tuning of the Helixoft is achieved through the magnetically controlled helical motion of its rigid helix component, which dynamically wraps around the soft microtube section. The magnetic fields also control the microcatheter steering, while the robotic manipulator controls the microcatheter advancement. R denotes the rotational field, and S denotes the static field. The purple curved arrow indicates the rotation direction of the helix, while the green arrow denotes its translational motion direction. The red–blue gradient circular arrow represents the rotating magnetic field, and the red–blue gradient straight arrow indicates the static magnetic field. The orange arrow denotes the deflection direction of the tube. Anatomical elements (lung, brain, uterus) are adapted from Freepik (free license).

To quantitatively predict the pose of the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter, we have developed a mechanical model capable of accurately describing the microcatheter’s mechanical behaviour. We establish both the precise numerical result and the approximate analytical expression for the trajectory of the microcatheter’s pose, providing a theoretical basis for precise control during operation. Combined with the robotic catheter manipulator, magnetic control and imaging modules, the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter performs active navigation, precision payload delivery, and localised tissue biopsy within complex luminal networks, as validated through in-vivo bronchial interventions and ex-vivo oviduct biopsy. Together, the Helixoft microrobotic system offers a generalisable control strategy with minimal tissue damage for the steerability and stiffness tuning of microsurgical instruments operation within small and sensitive anatomical environments (e.g., bronchioles, cerebral vasculature, and fallopian tube).

Results

Design and magnetic actuation principle of the Helixoft microrobot

The Helixoft microrobot comprises a rigid magnetic helix, a soft microtube, and a tubular distal end (Fig. 1). The rigid magnetic helix and tubular end are composed of medical-grade stainless steel, whereas the soft microtube is moulded from biocompatible silicone elastomer (Supplementary Fig. 1). This combination of materials ensures both compliance and biocompatibility for surgical applications. A cylindrical anchor is affixed to the soft microtube’s outer layer between the rigid magnetic helix threads to prevent unintended translational sliding of the rigid helix caused by frictional forces from the surrounding tissue. To further reduce friction during navigation, the entire microrobot is coated with a biocompatible lubricating layer. The tubular end, currently fabricated from a commercial biopsy needle for demonstration purposes, can be replaced with alternative biocompatible magnetic materials depending on specific purposes. The open architecture and dimensional scalability of Helixoft allow for seamless integration onto commercial microcatheters with diameters as small as 300 μm via simple adhesive bonding.

Continuous stiffness tuning of the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter is achieved by dynamically rotating the helix to adjust the length of the soft section of the Helixoft under a rotating magnetic field (R-field) through programming the rotation angle (Fig. 1). As the R-field rotates, the high-stiffness magnetic helix undergoes a screw-like helical motion, gradually overlapping or uncovering the soft microtube, thereby tuning the overall stiffness of the microcatheter. Steering of the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter is achieved by aligning its magnetic end under a static magnetic field (S-field) through programming the field direction. For clinical safety, the system is designed to operate in a sequential manner across distinct modes, including stiffness tuning, advancement, steering, and biopsy. Before each operation, the microcatheter stiffness is tuned under the R-field to the appropriate state. During advancement through straight luminal segments, the catheter is set to a high-stiffness state to prevent distal buckling. When approaching bifurcations or traversing tortuous lumens, its stiffness is reduced under the R-field so that the magnetic distal end can bend the soft microtube under the S-field for active steering. Upon reaching the target site, the microcatheter is switched back to a high-stiffness state to provide sufficient mechanical stability for biopsy or other manipulations. In practice, the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter can be set to three predefined states, simplifying its use for standard minimally invasive surgical scenarios without the need for complex continuous tuning. The low-stiffness state enables high flexibility for large-angle steering under the S-field, while the high-stiffness state ensures structural rigidity for stable advancement and tissue penetration. The medium-stiffness state provides a balanced mechanical response, adaptable to varied environmental conditions.

Mechanical modelling and pose prediction of the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter

Modelling the stiffness tuning and magnetic steering is critical for enabling efficient control of the navigational and surgical performance of the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter (Fig. 2a). After integration, the microcatheter’s average stiffness is dependent on the overlapping length of the rigid helix and the soft microtube, and thus tuneable through the rotation angle of the R-field. Afterwards, with a given stiffness, the microcatheter bending (orientation) is dependent on the magnetic torque, and thus adjustable through the field direction of the S-field. Based on an average constant curvature model, the microcatheter average stiffness satisfies \(EI={(\frac{L1}{LE1}+\frac{L2}{LE2})}^{-1}I\) (see details in Supplementary Notes 1 and 2)54. The pose of the microcatheter’s end is established as:

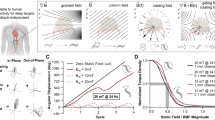

a Schematic of the microcatheter, showing key geometric parameters (left) and the constant-curvature model (right). b Three Helixoft microrobots with different stiffness ranges, mounted on microcatheters with distinct representative properties at sizes of 300 μm (thinnest diameter), 600 μm (largest stiffness tuning range) and 1 mm (finest tuning precision) in diameter. c Comparison results of approximate analysis, numerical analysis, and experimental measurement of the microcatheter’s pose (x, y, θ) under certain R- and S-field conditions. n = 3 repeated experiments. d Motion sequences showing the stiffness tuning process of the microcatheter through the screw-like helical motion of the rigid magnetic helix under the R-field. The black arrow denotes the translational motion direction of the rigid magnetic helix. e Sequential images showing the steering behaviour of three microcatheters at low-stiffness states. f Motion sequences showing the magnetic steering of the microcatheters at three stiffness states through the magnetic alignment of the distal end under the S-field. Scale bars: 2 mm for (b and d); 4 mm for (e and f).

We achieve the microcatheter pose through both an analytical solution after a certain approximation and a numerical solution by solving the governing system of nonlinear equations. During modelling and measurement, the results are dependent on the microcatheter size. For demonstration purposes, we focus on commercial microcatheters with diameters ranging from 300 μm to 1 mm, providing a representative range of sizes and stiffness levels (Fig. 2b). The numerical analysis is conducted using a hybrid optimisation method combining a genetic algorithm for global search and a local optimisation strategy. The approximate analytical expression is given as:

Methodological details and results are shown in Supplementary Note 2 and Fig. 2c.

Decoupled control for stiffness tuning and active steering of the microcatheter

Effective decoupling control between the helix and the magnetic distal end is crucial to eliminate interference between stiffness tuning and active steering. Supplementary Movies 1 and 2 demonstrate their decoupled motion, enabling sequential and independent control of both functions through magnetic field programming. Specifically, the radially magnetised rigid helix responds to the R-field (3 mT), producing screw-like helical motion with a translational speed of up to 5 mm/s to tune the microcatheter’s stiffness (Fig. 2d). Steering is subsequently achieved by aligning the radially magnetised end under the S-field. The bending response depends on the preprogrammed stiffness level. As shown in Fig. 2f, a 1 mm-diameter microcatheter achieves bending angles ranging from 24° at the high-stiffness state (L1/L = 0) to 73° at the low-stiffness state (L1/L = 1), when exposed to an S-field perpendicular to the distal end magnetisation. Adjusting the S-field direction further enables precise control of the bending angle, reaching up to 118° at the low-stiffness state under a 150-mT S-field of oriented at 150° (Fig. 2e).

To avoid unintended bending of the microcatheter during helical motion, the magnetic distal end is also radially magnetised. In contrast, an axially magnetised distal end would bend and rotate conically under the R-field, potentially causing tissue damage through friction and compression. The present decoupling control strategy, based on the material magnetisation–device structure–field pattern triad, enables fully programmable and simultaneous regulation of both motion and mechanical properties, promising as a generalisable decoupling control approach for magnetic soft robotic systems.

Control accuracy of the stiffness tuning and the microcatheter pose

The prediction accuracy of the developed model on the average stiffness and the distal end’s pose is validated by a standard three-point bending test and real-time tracking, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Figs. 2–5, both the approximate and numerical solutions exhibit strong agreement with the experimental results. Stiffness tuning results deviate across microcatheter sizes. For instance, among the three demonstrated microcatheters, the 600-μm microcatheter achieves the highest stiffness tuning range over 40-fold (36 kPa–1500 kPa), whereas the 1-mm microcatheter achieves the finest tuning precision during rotation (0.12 kPa/deg). For a given microcatheter, the magnetic end orientation increases almost linearly with the S-field strength, while increasing the R-field rotation angle progressively stiffens the microcatheter, reducing its bending response. As stiffness rises, the microcatheter’s bending transitions from a pure-rod behaviour toward a cantilever-like elasticity, deviating from linearity.

Comparing the measured values of the microcatheter poses with the numerical and simplified analytical solutions, we assess our model’s prediction accuracy by a classic mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) value test, in which the MAPE value represents the average deviation of the model’s predictions from the actual values (Supplementary Fig. 6). Generally, a MAPE below 10% suggests highly accurate forecasting, while 10–20% indicates good accuracy55,56. For the distal end’s pose coordinates of the microcatheter (x, y, θ) when the R-field rotates 0, 3 and 6 turns, the MAPE values between the numerical model and the experimental measurement are 4.7%, 5.1%, and 8.5%, respectively. Based on our results, the model provides a highly accurate prediction of the microcatheter pose (≥ 91.5%), especially at the low stiffness range (33 kPa–290 kPa).

Distributed stiffness control with a dual-segment module

To demonstrate the scalability of our stiffness tuning mechanism, we have implemented a multi-segment design that enables multi-level stiffness tuning across different regions of a single microcatheter57. As shown in Fig. 3, a dual-segment stiffness tuning module is integrated along the microcatheter. Each segment consists of a rigid magnetic helix coupled to a soft microtube. Independent control of each helix is achieved via the interplay between the magnetic actuation and local friction. A permanent cylindrical magnet (1.5 cm in diameter) generates a rotating magnetic torque, which increases as it approaches the helix. When the applied torque exceeds the resistive torque, the helix undergoes a screw-like motion, thereby enabling the stiffness tuning of the corresponding segment.

a Strategy for estimating resistive torque to enable independent helix control. Error bars represent standard deviation, n = 3 times, mean ± sd. The pink circle represents the actuation zone corresponding to \({T}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}} > {T}_{{{{\rm{resist}}}}}\). b Independent control of two helices in a single microcatheter. The orange and blue arrows indicate the motion directions of the first and second helices, respectively. c Multiple bending configurations of the corresponding microcatheter. The blue line indicates the shape of the microcatheter. Scale bar: 5 mm.

To determine the resistive torque threshold of the helical motion, the rotating magnet is moved toward the helix along the y-axis (Fig. 3a). Helical motion is initiated at a critical distance of 100 mm, corresponding to a field strength of ~0.5 mT (where \({T}_{{{{\rm{m}}}}} > {T}_{{{{\rm{resist}}}}}\)). Maintaining a constant radial distance (\({y}_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}\) = 80 mm), we then translate the magnet laterally along the x-axis. Helical motion is observed when the lateral offset \({x}_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}\) decreases to 40 mm (n = 1,2, referring to the first and second magnetic helix).

Simultaneous or selective control of individual segments is achieved by adjusting the position of the actuation magnet. As shown in Fig. 3b, placing the magnet at \({x}_{1}\) = 5 mm and \({x}_{2}\) = 5 mm with a constant \({y}_{{{{\rm{n}}}}}\) (80 mm) triggers both helices, switching them to a high-stiffness state. Under \({x}_{1}\) = 36 mm and \({x}_{2}\) = 50 mm, the first segment is switched to a low-stiffness state. Likewise, repositioning \({x}_{2}\) to 31 mm (\({x}_{1}\) = 44 mm) reactivates the second helix, resulting in a decrease in the stiffness of the second segment.

By independently tuning the stiffness of the dual-segment module, the microcatheter tip can exhibit multiple bending modes under an S-field (20 mT), including C-shape (both segments in the medium-stiffness state), L-shape (first segment in the low-stiffness state and second segment in the high-stiffness state), and J-shape (first segment in the medium-stiffness state and second segment in the low-stiffness state) (Fig. 3c). Independent helix control enhances the adaptive dexterity of the Helixoft system in complex luminal structures.

Demonstration of the surgical capabilities of the Helixoft system in phantom lumens

To demonstrate its navigation and surgical functionality, the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter is controlled using a combined system comprising the aforementioned magnetic control module for steering and stiffness tuning, along with a self-developed robotic manipulator for precise advancement and withdrawal (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Movie 3). The advancement speed is dynamically adjusted according to the luminal environment, with a speed range of 0–100 mm/s and a resolution of <0.5 mm. The parameters of the R-field and the S-field are modulated according to the theoretical model described above.

The navigation capability is first demonstrated using a 300 μm-diameter microcatheter to navigate a cerebrovascular phantom (ca. 1.5 mm in diameter) with successive bifurcations (Fig. 4a). The microcatheter initially advances smoothly in the straight main lumen but fails to enter the branch in its high-stiffness state. After being modulated to a low-stiffness state under the R-field, it successfully navigates into the left branch and reaches the secondary bifurcation under the S-field (20 mT). By changing the field direction, the microcatheter is then redirected into the right branch in the 2nd bifurcation, highlighting its adaptability to complex and branching vascular environments.

a Navigation through a narrow and tortuous vasculature phantom. The blue line indicates the defined path. b Active steering performed at the bifurcation in a carotid phantom, featuring a phantom lesion and phantom aneurysm in the right and left branches, respectively. The black arrow indicates the advancement or withdrawal direction. c Localised biopsy performed in the right branch through programmed stiffness tuning. d Precision drug delivery performed in the left branch. Scale bars: 4 mm.

We further demonstrate the biopsy and payload delivery capabilities in a carotid phantom, featuring a phantom lesion for biopsy and a phantom aneurysm for payload delivery in the right and left branches, respectively. The phantom is fabricated from biocompatible hydrogel with a similar modulus (ca. 40 kPa) to real tissue, ideal for testing the interaction and safety of the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter58. As shown in Fig. 4b, the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter at the high-stiffness state advances smoothly without buckling in the straight section, controlled by the robotic manipulator. However, at the bifurcation, a 20-mT S-field fails to generate sufficient bending on the microcatheter due to its high stiffness, resulting in damage in the undesired position. To address this, the microcatheter is withdrawn and modulated to the low-stiffness state under the R-field. After that, the S-field is applied again, allowing the microcatheter to smoothly steer into either the right or left branch.

For biopsy, the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter is initially guided into the right branch at the low-stiffness state. However, the microcatheter buckles towards the phantom lesion (stained in red) and fails to puncture it due to insufficient rigidity (Fig. 4c). To address this, the microcatheter is switched back to the high-stiffness state and successfully penetrates the lesion in the end. This ability to freely switch among different stiffness states enables the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter to dynamically balance the flexibility for navigation and rigidity for mechanical intervention.

For payload delivery, the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter is magnetically controlled to perform multi-stage bending to enter the phantom aneurysm site (Fig. 4d). Initially, the microcatheter is steered with a primary bending of ca. 15° under the S-field to be aligned with the branch angle for smooth enter (Fig. 4b, t = 29 s). As the tip approaches the bottom wall, a secondary bending of ca. 40° is introduced to prevent wall contact (t = 30 s). This multi-stage bending allows the microcatheter to gradually adapt to the luminal environment, minimising the risk of tissue damage during navigation. Upon arrival at the target site, a mock drug (gelatin-based embolic agents with red ink) is injected through the fluidic tubing at microlitre-scale precision controlled by a microfluidic pump. This demonstration validates not only the precision drug delivery capability of the Helixoft system, but also its seamless integration and structural stability, particularly under bending stress.

Consequently, the Helixoft system demonstrates efficient navigation, localised biopsy and intraluminal payload delivery. Its scalable size, tuneable stiffness, active steering and non-disruptive control offer a versatile solution for surgical tasks in narrow and tortuous lumens with varying dimensions.

Validation of precision payload delivery in pulmonary interventional surgery of live pigs

Owing to its structural stability and compact size, the Helixoft-microcatheter is fully compatible with commercial real-time surgical imaging systems, such as X-ray fluoroscopy and endoscopy, and thus directly applicable in clinical procedures. In this section, we demonstrate the performance of precision payload delivery of the Helixoft-microcatheter and its quantitative safety evaluation during a classic pulmonary interventional procedure in live pigs (n = 3). The microcatheter is magnetically controlled by a magnet embedded on a robotic arm with six revolute joints, and monitored in real-time by a digital radiography (DR) imaging setup (Fig. 5a). A commercial mini-camera is integrated with the Helixoft-microcatheter for the intratracheal visualisation of the bronchial anatomy during navigation (Fig. 5b).

a Surgery setup comprising a digital radiography (DR) imaging setup and a magnetic field generator mounted on a six-joint robotic arm. b Schematic (left) and photograph (right) of the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter equipped with a mini-camera for intraluminal imaging. c X-ray guided navigation of the microcatheter through bronchial bifurcations by multi-stage steering. d Precision drug injection into the quaternary bronchus by the microcatheter. The bottom left inset shows the enlarged X-ray image; the top right inset shows the corresponding live image captured by the onboard mini-camera. The blue trace indicates the microcatheter trajectory; the white dotted lines outline the bronchial contour. Scale bars: 4 mm for (b); 3 mm for (c and d).

The unique stiffness tuning capability of the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter enables efficient deep bronchial navigation, reaching the fourth-generation branches. Initially, the Helixoft-microcatheter is set to a high-stiffness state, enabling it to smoothly enter the trachea without buckling (t = 0 s) (Fig. 5c). While this initial rigidity facilitates stable insertion in the trachea, it brings risks of mechanical irritation at bronchial bifurcations where the distal biopsy tip might scrape the lumen walls, potentially inducing bronchospasms. To mitigate this interference, the Helixoft-microcatheter is switched to the medium-stiffness state, increasing its compliance and thus minimising the mechanical mucosal irritation during navigation (t = 15–45 s). The stiffness tuning process can be observed in the X-ray images of the pig in the prone position. Subsequently, magnetic steering is activated under the S-field to guide the microcatheter into the primary bronchus (t = 60–75 s, lateral position). Continuing forward, it reaches another bifurcation and successfully enters the secondary bronchus (t = 90–105 s). Owing to its small diameter, the microcatheter successfully accesses the tertiary bronchi and quaternary bronchi (ca. 2 mm in diameter, t = 120–145 s). To validate the therapeutic delivery capability of the Helixoft system, an anticancer drug solution (Doxorubicin) containing contrast agent is administered through the fluidic tubing over a 15-s period (t = 160–175 s) (Fig. 5d). We employ a fluidic control system to precisely regulate the amount of drug (Supplementary Fig. 8). A total of 25 μL of liquid drug is delivered through the microcatheter. The drug distribution is successfully monitored through both the integrated mini-camera and the X-ray radiography in the prone position (Supplementary Fig. 9). After administration, no residual drug remains in the catheter lumen, confirming the dosing accuracy. To assess the navigation success rate, ten independent navigation trials are performed in total. Under combined real-time X-ray and endoscopic imaging, all trials successfully reach the target position (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). The mean navigation time from the trachea to the quaternary bronchus is approximately 4 min.

The open architecture of our Helixoft system within compact size enables seamless integration with auxiliary dual-modality imaging modules, which allows real-time visualisation and precise spatiotemporal controllability of the microcatheter during multi-stage steering manoeuvres. Such synchronised control of a hybrid framework with imaging and actuation modules effectively prevents unintended contact with the lumen walls, ensuring smooth navigation, and minimising the risk of tissue damage. Post-operative assessment confirms the safety profile of the intervention, as indicated by maintenance of stable body weight and normal activity in the porcine models over a 7-day post-operative observation period (Supplementary Fig. 12). Furthermore, routine clinical blood analyses and histological examinations reveal no signs of acute inflammation or mucosal damage (Supplementary Fig. 13, Supplementary Note 3, and Supplementary Tables 3–6).

Demonstration of localised biopsy in real tissue

The Helixoft-integrated microcatheter combines programmable stiffness tuning with magnetic steering, enabling precise force interaction with delicate soft tissues. This capability is critical for performing localised biopsies within narrow and sensitive luminal environments, such as the oviduct, without damaging adjacent healthy tissue. In order to observe the real-time interaction details between the Helixoft system and physiological tissue, we use an ex-vivo porcine oviduct as the biopsy demonstration model (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Movie 4). This model provides a visually accessible and anatomically realistic biomechanical environment, with complex physiological features such as mucosal folds and mucus layers. Such a complex luminal environment introduces substantial friction and mechanical obstruction that impede the microcatheter’s navigation.

a Active steering of the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter. In the high-stiffness state, the microcatheter advances through the oviduct and causes unintended invasion on healthy tissue at the corner (0–2 s). The microcatheter is then switched to the low-stiffness state under the R-field, enabling magnetic steering under the S-field (2–16 s). Finally, the microcatheter is switched to the medium-stiffness state and continues advancing through the corner (16–37 s). b Localised biopsy of the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter. In the medium-stiffness state, the microcatheter buckles upon contact with the target tissue (0–2 s). After switching back to the high-stiffness state (4–8 s), it successfully penetrates the target tissue (11 s). The black arrow indicates the advancement direction. Scale bars: 3 mm.

Traditional catheters often fail to maintain controllable tissue interaction during deep luminal biopsy missions, due to their inability to transition effectively between compliant steering and rigid penetration, frequently resulting in unintended buckling or tissue damage during tissue access or navigation. In contrast, our Helixoft-integrated microcatheter demonstrates adaptive performance through programmable stiffness control. In our demonstration, the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter uses its high-stiffness state to advance smoothly in the straight section of the oviduct until arriving at a corner (Fig. 6a). At this point, if no stiffness tuning is implemented, the magnetic tip collides with the lumen wall, causing unintended invasion of healthy tissue (t = 2 s). To navigate the turn safely, the microcatheter is withdrawn and switched to the low-stiffness state under the R-field, allowing sufficient steering controlled magnetically under the S-field. After successfully navigating the lumen turn, the microcatheter is then switched to the medium-stiffness state, maintaining a ca. 25° bending angle to continue advancing. Upon reaching the target site, the microcatheter is pushed toward the target tissue but fails to penetrate due to buckling under insufficient stiffness. It is then switched back to the high-stiffness state. After that, it finally successfully penetrates the oviduct tissue (Fig. 6b). After biopsy, the microcatheter is withdrawn, carrying the obtained tissue sample in its biopsy needle. This biopsy demonstration highlights the programmable stiffness adaptability of the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter in complex physical environments, enabling safe and effective interaction with target sites while minimising disruption on environmental tissues.

Discussion

We have developed a microrobotic system comprising the robotic manipulation, magnetic control, and imaging modules, centred around a helical soft microrobot (Helixoft), to enable active stiffness tuning and adaptable steering of commercial microcatheters. This system addresses a long-standing challenge in MIS—the inability of existing catheters to transition between high compliance for safe steering and high stiffness for efficient advancement or tissue penetration. By integrating Helixoft into microcatheters with diameters as small as 300 μm, we achieve programmable mechanical reconfiguration using only the magnetic field without reliance on thermal, electrical, or optical stimuli, thereby avoiding tissue-disruptive side effects.

The key innovation of this system is its magnetically decoupled control strategy, realised through a material magnetisation–device structure–field pattern triad. This strategy allows independent actuation of distinct components, achieving over 40-fold stiffness tuning and directional steering up to 118° within complex anatomical networks. In addition, the Helixoft system allows rapid tuning by increasing the magnetic field frequency to 20 Hz, which shortens the transition time and enables tenfold tuning in stiffness within 0.3 s. However, this rapid tuning mode is generally avoided in practice due to stability concerns.

We have validated the surgical capabilities of the present system in both ex vivo and in vivo models, including localised biopsy in porcine oviducts and deep-bronchial payload delivery under real-time imaging in live pigs. The Helixoft system further supports the integration of microsurgical tools such as mini-cameras, electrodes, and optical fibres, expanding its potential for imaging-guided diagnostics, localised ablation, and multifunctional treatment in confined organ systems including the lungs, brain, and reproductive tract.

During navigation, the microcatheter also experiences tangential friction from the lumen wall, which primarily resists axial advancement but has only a limited effect on active steering. With the imaging feedback, the magnetic field precisely controls the Helixoft system to dynamically modulate both its position and bending angle to adapt to the lumen environment and minimise excessive tip–wall contact. In addition, the catheter surface is coated with a low-friction hydrogel layer, minimising the mechanical resistance during navigation. Validation in hydrogel phantoms, ex vivo tissue, and live porcine models has confirmed the Helixoft’s high-performance navigation in complex lumens.

While magnetically controlled catheters show great potential in biopsy and payload delivery, their use in patients who have magnetic implants, such as cardiac pacemakers or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, requires careful planning due to safety concerns related to the interaction of these devices with magnetic fields59. In addition, although these catheters are compatible with imaging modalities such as CT and ultrasound, their combination with Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) would necessitate a redesign of the control strategy, such as using the MRI scanner itself for both actuation and imaging59. Potential safety risks, particularly thermal injury, would also need to be carefully addressed.

In summary, the Helixoft microrobotic system offers a generalisable strategy for motion-driven mechanical programming of minimally invasive instruments. By enabling real-time, non-disruptive control over the mechanical behaviour of tools in complex environments, it establishes a foundation for intelligent robotic systems capable of operating safely and precisely within the body’s delicate luminal networks.

Methods

Fabrication of the soft microtube

All chemicals used in this paper were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) unless otherwise specified. The soft microtube was fabricated using Ecoflex-20 (Dongzhixuan Co., Ltd., China), a biocompatible silicone-based elastomer. The soft microtube, with a thin wall thickness, was fabricated through a one-step moulding process on the commercial catheter. Specifically, two components of Ecoflex were mixed at a 1:1 weight ratio, and the Ecoflex mixture was transferred into a vacuum container to remove air bubbles. Afterwards, the Ecoflex mixture was filled between concentric microtube walls with defined diameter differences, allowing for a wide dimension range for the soft microtube (0.3–1 mm). Furthermore, the Ecoflex mixture in the tube was cured at 60 °C for 20 min. After moulding, the soft microtube was directly integrated onto the commercial microcatheter, with both ends of the soft microtube connected to the microcatheter tube. The inner and outer diameters of the soft microtube match those of the commercial microcatheter. Three dimensions of soft microtubes were fabricated, including 300 μm, 600 μm, and 1 mm.

Fabrication of the Helixoft-integrated microcatheter

After fabricating the soft microtube, a small anchor was glued onto the commercial microcatheter. The rigid magnetic helix was coaxially assembled with the Ecoflex tube, with the length of the helix being longer than that of the soft microtube. The soft microtube was connected to the commercial microcatheter. (e.g., PE tube), which was fixed at the distal end. The rigid magnetic helix was fabricated by tightly winding a stainless-steel wire around a cylindrical metal rod, where the helix diameter was determined by the rod’s diameter. The pitch and number of turns were adjusted to tune the stiffness and length of the structure. The rigid magnetic helix, with higher stiffness, was coaxial with the soft microtube, which had lower stiffness. Three rigid magnetic microhelices with varying dimensions—0.5 mm (0.08-mm wire diameter, 0.3-mm pitch), 1.1 mm (0.2-mm wire diameter, 0.2-mm pitch), and 2 mm (0.1-mm wire diameter, 1-mm pitch)—were matched individually with corresponding soft microtubes. The tubular distal end was modular and material-selective, tailored to specific functional requirements. For tissue biopsy, a stainless-steel needle structure (outer diameter: 0.5 mm) was employed and partially filled with an NdFeB–Ecoflex composite (10 wt% NdFeB particles) to ensure magnetisation stability. The delivery channel for payloads was defined by a fibre inserted during the composite filling process, resulting in a channel approximately 100 μm in diameter. For applications without biopsy requirements, the distal head was fully enclosed within the microcatheter. All magnetic components were magnetised using a high-field magnetizer, with five magnetisation cycles to ensure long-term stability of magnetisation60,61. The magnetic components (stainless steel helix, biopsy needle with NdFeB–Ecoflex composite, ring-shaped NdFeB magnet, and pure biopsy needle) were characterised using vibrating sample magnetometry (Supplementary Fig. 14). A biocompatible lubricating layer of polydimethylacrylamide (PDMAA) was coated onto the surface of the microcatheter. The microcatheter was thoroughly cleaned by sequential rinsing with ethanol and isopropanol to remove surface contaminants. The cleaned microcatheter was treated with oxygen plasma (100 W, 1 min) to activate the surface, enhancing initiator attachment and polymer adhesion. The helix was pre-treated by silanisation using APTES (3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane). After this, the catheter was immediately immersed in an ethanol solution containing 10 wt% benzophenone for 20 min. This step allows benzophenone to adsorb onto the activated surface. The catheter was then transferred to an aqueous solution containing 20 wt% N,N′-dimethylacrylamide and 0.5 wt% Irgacure 2959. The microcatheter was soaked for 10 min to allow penetration of the monomer. Ultraviolet (UV) light (365 nm) was applied for 1 h to initiate in-situ polymerisation, resulting in the formation of a stable PDMAA coating on the catheter surface. The coated catheter was rinsed thoroughly with deionised (DI) water to remove any unreacted monomers or residual chemicals, then dried under nitrogen flow. The microcatheter was sterilised using ethylene oxide (EtO). This sterilisation process did not affect its magnetisation or structural integrity, as verified by surface magnetic flux intensity measurements, repeated bending tests, and payload delivery performance (Supplementary Fig. 15). Cytotoxicity and long-term adhesion of the hydrogel coating were evaluated by cell culture (BEAS-2B cell line, obtained from Saibaikang, Biological iCell-h023) and by bending-cycle tests in saline, respectively (Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17).

Stiffness test

The stiffness test was based on the three-point bending testing method (MARK-10 EMS303). The force sensor had a force sensing range (0–2.5 N) and a resolutionof 0.0005 N. In the experiment, the sensor’s motion speed was 3 mm/min, and the displacement was fixed. The different types of stiffness were realised by changing the overlapping length of the rigid magnetic helix and soft microtube. The stiffness states were defined by helix pitch coverage length (L₁ = turns × pitch) together with the corresponding bending stiffness (EI), thereby avoiding ambiguity related to catheter diameter. Specifically, for the helix with a pitch of 1 mm and diameter of 2 mm, the three states were: Low stiffness: (pitch coverage L₁ = 0 mm, EI = 2.06 × 10−⁸ N·m²), Medium stiffness: (pitch coverage L₁ = 3 mm, EI = 3.60 × 10−8 N·m²), and High stiffness: (pitch coverage L₁ = 6 mm, EI = 1.72 × 10−7 N·m²). For the helix with a pitch of 0.2 mm and diameter of 1 mm, the three states were: Low stiffness: (pitch coverage L₁ = 0 mm, EI = 1.72 × 10−9 N·m²), Medium stiffness: (pitch coverage L₁ = 1.9 mm, EI = 9.72 × 10−9 N·m²), and High stiffness: (pitch coverage L₁ = 3.8 mm, EI = 7.43 × 10−8 N·m²). The control accuracy of the stiffness tuning and the microcatheter pose was furthermore analysed using a classic MAPE value test with MATLAB and Origin.

Magnetic control module

The magnetic control module employed either a coil system or a permanent magnet mounted on a robotic arm. The coil-based module consisted of three pairs of custom-built Helmholtz coils made of copper wire and connected to a direct current (DC) power supply. The three pairs of coils generated a three-axis magnetic field with 99% field homogeneity, producing field strengths up to 30 mT within a 50-mm spherical region over a frequency range of 0–20 Hz. The magnet-based module used a permanent block magnet (45 × 45 × 21 mm) mounted on a robotic arm, providing a maximum field strength of 200 mT. The robotic arm with six revolute joints was used to manoeuvre the block magnet. The magnetic control module generated the R- and S-fields for stiffness tuning and active steering. In the coil-based module, field strength and frequency were adjusted by varying the coil current, with parameters controlled through a graphical user interface. In the magnet-based module, the R- and S-fields were produced by rotating or reorienting the magnet with robotic arm control, and the R-field frequency was set by the motor rotation frequency (0–5 Hz). The coil-based module was mainly used for benchtop experiments and 3D phantom models, whereas the magnet-based module was applied in vivo to provide a larger working space. To accommodate different magnetic field penetration depths in vivo, magnets of varying sizes and field strengths were selected accordingly. The microcatheter’s bending was tested over 100 cycles, with a control accuracy of less than 1°. For the helix rotation, the strength of the R-field was 3 mT. For modelling, the strength of the S-field was set at 150 mT to test the maximum steering angle. The maximum steering angle was determined by gradually increasing the deflection angle until rebound of the magnetic tip was observed. For demonstrations in the phantom model and isolated organ, the strength of the S-field was maintained at 20 mT. For demonstration in the live pig, the strength of the S-field was 15 mT. The influence of the gradient field was weak below 20 mT (Supplementary Fig. 18).

Advancement based on the robotic catheter manipulator

A friction wheel mechanism was designed to drive the microcatheter. A pair of friction wheels was used to clamp the microcatheter. When the two friction wheels rotate in opposite directions simultaneously, forward or backward movement of the microcatheter is generated. The maximum driving speed of the friction wheels was 100 mm/s, with an positioning accuracy of better than 0.5 mm. Additionally, we designed a driver that adapts to the modular structural layout, achieving a high degree of integration for the wiring and sensors.

Payload delivery in the carotid phantom fabricated with tissue-mimicking hydrogel

The phantom was based on the solidified 10% gelatin. Firstly, the structure of the phantom with bifurcation and target area was designed by software. And a mould was printed using a 3D printer (Ultimaker S3, China). Then the 10% gelatin solution was filled into the mould. Then the mould was cooled at 4 °C. The gelatin-based embolic agent with red ink was chosen as the mock drug. The mock drug stored in a 1.5 mL tube can be pumped by a pressure pump (Fluigent). The flow speed can be controlled by adjusting the pressure. The pressure range was 0–2000 mPa. The sealing property of the microcatheter was tested under high pressure (2000 mPa) during the bending process. In addition, the microcatheter was compatible with a protective outer catheter (Supplementary Note 5 and Supplementary Fig. 19).

Animal experiment

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with procedures approved by the Animal Experiment Ethics Committee (IACUC) of Shenzhen LingFu TopBiotech Co., Ltd (approval no. TOPGM-IACUC-2025-0012). Three six-month-old male Bama mini-pigs (about 30 kg) were purchased from Fuhao Experimental Animal Breeding Center (Beijing, China). The pigs were anesthetised with Zoletil 50 and maintained under isoflurane anesthesia. Prior to the procedure, the microcatheter was soaked in PBS and sterilised under ultraviolet light for one hour. The microcatheter, equipped with a mini-camera, was inserted into the pig’s bronchial tree through the tracheal cannula, and its movement within the bronchial tree was monitored using DR imaging. The rigid magnetic helix, controlled by an external magnetic field, enabled forward and backward motion to tune the microcatheter’s stiffness, facilitating navigation through bronchial bifurcations and entry into the target area for anticancer drug injection. The anticancer drug solution (Doxorubicin) containing contrast agent (barium sulphate) was used in this study. Upon completing the injection, the microcatheter was carefully withdrawn along the original path. Following the procedure, the pig was monitored for three days. Pathological analysis was conducted during the observation period, and the pig’s general condition and body weight were recorded throughout the treatment. A required amount of mock drug was preloaded into the reservoir connected to the microcatheter. The drug solution was then delivered through the microcatheter. Following delivery, an additional 100 μL of air (or saline)—corresponding to the microcatheter’s internal dead volume (\({V}_{{{{\rm{d}}}}}={{{\rm{\pi }}}}\cdot {({d}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}/2)}^{2}\cdot {L}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\), where \({d}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\) is the internal diameter and \({L}_{{{{\rm{c}}}}}\) is the length)—was injected as a flushing buffer to ensure complete payload delivery.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary files. Any additional requests for information can be directed to, and will be fulfilled by, the corresponding authors. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Chen, Z. & Sánchez, M. M. Microrobots in gynaecological care and reproductive medicine. Nat. Rev. Electr. Eng. 1, 759–761 (2024).

Nelson, B. J. & Pané, S. Delivering drugs with microrobots. Science 382, 1120–1123 (2023).

Zhang, T. et al. Sub-millimeter fiberscopic robot with integrated maneuvering, imaging, and biomedical operation abilities. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–12 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Magnetic soft microfiberbots for robotic embolization. Sci. Robot. 9, eadh2479 (2024).

Dong, Y. et al. Endoscope-assisted magnetic helical micromachine delivery for biofilm eradication in tympanostomy tube. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq8573 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. AI co-pilot bronchoscope robot. Nat. Commun. 15, 241 (2024).

Kato, T., King, F., Takagi, K. & Hata, N. Robotized catheter with enhanced distal targeting for peripheral pulmonary biopsy. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics 26, 2451–2461 (2021).

Gu, H. et al. Self-folding soft-robotic chains with reconfigurable shapes and functionalities. Nat. Commun. 14, 1263 (2023).

Wu, H. et al. A drug-free cardiovascular stent functionalized with tailored collagen supports in-situ healing of vascular tissues. Nat. Commun. 15, 735 (2024).

Hu, S. et al. Exosome-eluting stents for vascular healing after ischaemic injury. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 1174–1188 (2021).

Rivkin, B. et al. Electronically integrated microcatheters based on self-assembling polymer films. Sci. Adv. 7, eabl5408 (2021).

Agno, K. C. et al. A temperature-responsive intravenous needle that irreversibly softens on insertion. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 8, 963–976 (2024).

Pancaldi, L. et al. Flow driven robotic navigation of microengineered endovascular probes. Nat. Commun. 11, 6356 (2020).

Jolaei, M., Hooshiar, A., Dargahi, J. & Packirisamy, M. Toward task autonomy in robotic cardiac ablation: learning-based kinematic control of soft tendon-driven catheters. Soft Robot 8, 340–351 (2021).

Soltani, M. K., Khanmohammadi, S., Ghalichi, F. & Janabi-Sharifi, F. A soft robotics nonlinear hybrid position/force control for tendon driven catheters. Int. J. Control. Autom. Syst. 15, 54–63 (2017).

Leber, A. et al. Highly integrated multi-material fibers for soft robotics. Adv. Sci. 10, 2204016 (2023).

Zhou, C. et al. Submillimeter fiber robots capable of decoupled macro-micro motion for endoluminal manipulation. Sci. Adv. 10, eadr6428 (2024).

Kim, J., Choi, W. Y., Kang, S., Kim, C. & Cho, K. J. Continuously variable stiffness mechanism using nonuniform patterns on coaxial tubes for continuum microsurgical robot. IEEE Trans. Robot. 35, 1475–1487 (2019).

Li, Z. et al. Design and hierarchical control of a homocentric variable-stiffness magnetic catheter for multiarm robotic ultrasound-assisted coronary intervention. IEEE Trans. Robot. 40, 2306–2326 (2024).

Piskarev, Y. et al. A variable stiffness magnetic catheter made of a conductive phase-change polymer for minimally invasive surgery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2107662 (2022).

Choi, J. et al. Design of continuum robot with variable stiffness for gastrointestinal stenting using conformability factor. IEEE Trans. Med. Robot. Bionics 2, 529–532 (2020).

Abdelaziz, M. E. M. K. et al. Fiberbots: robotic fibers for high-precision minimally invasive surgery. Sci. Adv. 10, eadj1984 (2024).

Nauber, R. et al. Medical microrobots in reproductive medicine from the bench to the clinic. Nat. Commun. 14, 728 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. Evolutionary design of magnetic soft continuum robots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 118, 1–8 (2021).

Yang, Q. et al. Application of magnetically actuated self-clearing catheter for rapid in situ blood clot clearance in hemorrhagic stroke treatment. Nat. Commun. 13, 520 (2022).

Zhou, C. et al. Ferromagnetic soft catheter robots for minimally invasive bioprinting. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–12 (2021).

Lussi, J. et al. A submillimeter continuous variable stiffness catheter for compliance control. Adv. Sci. 8, 2101290 (2021).

Kim, Y., Parada, G. A., Liu, S. & Zhao, X. Ferromagnetic soft continuum robots. Sci. Robot. 4, 1–16 (2019).

Zhang, M. et al. A magnetically actuated microcatheter with soft rotatable tip for enhanced endovascular access and treatment efficiency. Sci. Adv. 11, eadv1682 (2025).

Chang, Y. et al. Milli-spinner thrombectomy. Nature 642, 336–342 (2025).

Li, R. et al. Small-scale magnetic soft robotic catheter for in-situ biomechanical force sensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 270, 116977 (2025).

Wang, X. et al. A magnetic catheter with force sensing capability toward interventional surgery. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 9, 10375–10382 (2024).

Chautems, C. et al. Magnetic continuum device with variable stiffness for minimally invasive surgery. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2, 1900086 (2020).

Wang, M. et al. Synergy actuation of magnetic catheter for on-site biopsy using global and local magnetic field. Procedia Comput. Sci. 250, 150–156 (2024).

Hong, A., Petruska, A. J., Zemmar, A. & Nelson, B. J. Magnetic control of a flexible needle in neurosurgery. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 68, 616–627 (2021).

Kuntz, A. et al. Autonomous medical needle steering in vivo. Sci. Robot. 8, 1–14 (2023).

Yin, X., Guo, S., Hirata, H. & Ishihara, H. Design and experimental evaluation of a teleoperated haptic robot-assisted catheter operating system. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 27, 3–16 (2016).

Song, Y. et al. Performance evaluation of a robot-assisted catheter operating system with haptic feedback. Biomed. Microdevices 20, 1–16 (2018).

Ruan, X., Xuan, S., Zhao, J., Bian, H. & Gong, X. Mechanical performance of a novel magnetorheological fluid damper based on squeeze-valve bi-mode of MRF. Smart Mater. Struct. 29, 055018 (2020).

Ide, M. et al. Development of a training system for interventional radiology. In Modelling in Medicine and Biology VIII. (ed. Brebbia, C. A.) 313–322 (WIT Press, 2009).

Gu, X. & Ren, H. A survey of transoral robotic mechanisms: distal dexterity, variable stiffness, and triangulation. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 4, 0007 (2023).

Tonazzini, A., Sadeghi, A. & Mazzolai, B. Electrorheological valves for flexible fluidic actuators. Soft Robot 3, 34–41 (2016).

Mattmann, M. et al. Thermoset shape memory polymer variable stiffness 4D robotic catheters. Adv. Sci. 9, 2103277 (2022).

Piskarev, Y. et al. Fast-response variable-stiffness magnetic catheters for minimally invasive surgery. Adv. Sci. 11, 2305537 (2024).

Chautems, C., Tonazzini, A., Floreano, D. & Nelson, B. J. A variable stiffness catheter controlled with an external magnetic field. In 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, 181–186 (IEEE, 2017).

Yang, P., Mao, L., Tian, C., Meng, X. & Xie, H. A cooperative and multifunctional magnetic continuum robot for noninteractive access, dexterous navigation, and versatile manipulation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 35, 2412543 (2024).

Hu, Y., Zhang, L., Li, W. & Yang, G. Z. Design and fabrication of a 3-d printed metallic flexible joint for snake-like surgical robot. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 4, 1557–1563 (2019).

Berthet-Rayne, P. et al. Rolling-joint design optimization for tendon driven snake-like surgical robots. In 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 4964–4971 (IEEE, 2018).

Zhang, D. et al. Passive particle jamming variable stiffness material-based flexible capacitive stress sensor with high sensitivity and large measurement limit. Adv. Mater. Technol. 6, 2100106 (2021).

Ibrahimi, M., Paternò, L., Ricotti, L. & Menciassi, A. A layer jamming actuator for tunable stiffness and shape-changing devices. Soft Robot 8, 85–96 (2021).

Sun, Y. et al. Instant variable stiffness in cardiovascular catheters based on fiber jamming. Sci. Adv. 11, eadn1207 (2025).

Liu, H. et al. A concentric tube magnetic continuum robot with multiple stiffness levels and high flexibility for potential endovascular intervention. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 597, 172023 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Soft millirobot capable of switching motion modes on the fly for targeted drug delivery in the oviduct. ACS Nano 18, 8694–8705 (2024).

Hao, Y., Gao, J., Lv, Y. & Liu, J. Low melting point alloys enabled stiffness tunable advanced materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 1–25 (2022).

Montaño Moreno, J. J., Palmer Pol, A., Sesé Abad, A. & Cajal Blasco, B. Using the R-MAPE index as a resistant measure of forecast accuracy. Psicothema 25, 500–506 (2013).

Lewis, C. D. International and Business Forecasting Methods (Butterworths, London, 1982).

Wang, C. et al. Heterogeneous multiple soft millirobots in three-dimensional lumens. Sci. Adv. 10, eadq1951 (2024).

Yokota, Y. et al. Carotid elastic modulus in vivo estimation using ultrasonic images and comparison to in vitro measurement for animal. In World Congress on Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering (eds Dössel, O. & Schlegel, W. C.) 1226–1229 (Springer, 2009).

Tiryaki, M. E., Elmacioǧilu, Y. G. & Sitti, M. Magnetic guidewire steering at ultrahigh magnetic fields. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg6438 (2023).

Abbott, J. J., Ergeneman, O., Kummer, M. P., Hirt, A. M. & Nelson, B. J. Modeling magnetic torque and force for controlled manipulation of soft-magnetic bodies. IEEE Trans. Robot. 23, 1247–1252 (2007).

Beleggia, M., Vokoun, D. & De Graef, M. Demagnetization factors for cylindrical shells and related shapes. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 321, 1306–1315 (2009).

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Dr. Yongshuai Ge, Dr. Zhitong Chen, and Dr. Xiaokun Liang from SIAT for their support with 3D printing and X-ray imaging. We also thank Dr. Huaiyu Wang from SIAT and Xun Zhang from the Southern University of Science and Technology for their assistance with the animal experiments. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 32422046 (H.X.), 52203152 (Y.L.), and 52303167 (H.X.)); the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (Grant Nos. JCYJ20220818101409021 (H.X.), JSGGKQTD20221101115654021 (H.X. and Y.L.), GNZX20241031094809013 (H.X. and Y.L.), and RCBS20221008093222008 (Y.L.)); the Special Projects in Key Fields of Ordinary Colleges and Universities in Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2022ZDZX3047 (H.X.)); and the Obstetrics and Gynecology Open Fund of Peking University Third Hospital (Grant No. BYSYSZKF2023013 (H.X.)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.X. conceived the idea. H.X. and Y.L. designed the experiments. Y.L., J.H., and X.Z. performed the experiments with the help of X.C., L.B., R.L., and M.X. Y.L., J.H. and X.Z. analysed the experimental data with the help of H.X. and M.X. H.X. and M.X. performed the modelling analysis. All authors wrote the paper and participated in the discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Mehmet Efe Tiryaki, Hritwick Banerjee and the other anonymous reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Huang, J., Zhao, X. et al. Magnetically controlled microrobotic system for programmable stiffness tuning and active steering of microcatheters. Nat Commun 17, 916 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67638-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67638-z