Abstract

Nuclear Factor IA, a member of the long-studied Nuclear Factor I family of DNA-binding proteins, plays pivotal roles in development and metabolism. Dysregulation or loss of Nuclear Factor IA is associated with severe neurological defects in humans and disruptions in fatty acid metabolism linked to conditions such as osteoarthritis. Despite extensive study, the DNA recognition mechanism of Nuclear Factor I family proteins remains unresolved. Previous studies have proposed that these proteins dimerize via their DNA-binding domains to bind TGGCA-containing dyad sequences. In this study, we demonstrate that both full-length Nuclear Factor IA and its isolated DNA-binding domain are monomeric in solution, challenging dimer models. Genome-wide ChIP-Seq analysis shows TGGCA half-sites are enriched among Nuclear Factor IA binding motifs. We determine Nuclear Factor IA’s crystal and solution structures bound to half-site and dyad-symmetric DNA motifs, providing a structural basis for its monomeric DNA recognition. Furthermore, functional binding assays show that key residues in Nuclear Factor IA, which facilitate base-specific interactions, are critical for DNA sequence recognition and binding. These findings establish the DNA-binding mechanism of Nuclear Factor IA and provide a detailed molecular framework for understanding the functions of this classic transcription factor family.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Nuclear Factor I (NFI) family comprises site-specific DNA-binding transcription factors (TFs) that are critical for regulating gene expression and viral DNA replication1,2,3. Initially identified as essential activators of the adenovirus origin of replication, NFI proteins were later shown to bind promoter and enhancer regions of diverse genes, regulating transcription in both cellular and viral systems4,5,6,7. In vertebrates, the NFI family comprises four members—NFIA, NFIB, NFIC, and NFIX—each exhibiting distinct, though sometimes overlapping, expression patterns during embryogenesis and in adult stem cells8,9,10. These proteins are involved in various developmental and regulatory pathways, including cytokine-mediated differentiation and cerebellum development, underscoring their broad functional versatility11,12,13. Dysregulation of NFI proteins has been associated with significant changes in gene expression, leading to diverse physiological and pathological consequences, including tumor development in diverse cancers14,15.

The NFI family member, NFIA, has emerged as a critical regulator of both neural development and metabolism. In conjunction with NFIB, NFIA is indispensable for proper brain development and central nervous system function16,17,18. Nfia-knockout mice exhibit severe neurological abnormalities, including corpus callosum dysgenesis, hippocampal malformations, and enlarged ventricles19,20,21. Consistent with these findings, mutations or deletions of Nfia in humans are associated with intellectual disabilities and structural brain defects22,23,24,25. Beyond its well-established role in neural development, our recent work identified elevated NFIA expression in both human and murine osteoarthritic (OA) articular chondrocytes26. In this context, NFIA acts as a key transcription factor that upregulates genes involved in fatty acid metabolism, including the rate-limiting enzymes ACACA and CPT2. This transcriptional activation enhances fatty acid metabolism, leading to disrupted cellular homeostasis in OA articular chondrocytes. Notably, NFIA inhibition reversed these effects by suppressing metabolic enzyme overexpression, which subsequently alleviated cartilage destruction, joint pain responses, and disease progression in the murine OA model. These findings have motivated us to pursue the structural characterization of NFIA as a foundation for developing mechanism-based therapies for OA, particularly given the current lack of disease-modifying treatments27,28,29.

In terms of domain organization, NFIA comprises a well-defined N-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD), which mediates sequence-specific DNA recognition, and a proline-rich C-terminal region that remains largely unstructured and variable1,15. The C-terminal domain is subject to alternative splicing and post-translational modifications, contributing to its role in transcriptional activation or repression30. The DBD is highly conserved across the NFI protein family yet shares no significant sequence homology with other DNA-binding domains31,32. Previous studies suggested that NFI proteins dimerize via their DBDs and thereby recognize dyad-symmetric sequences, such as TGGCA(N3)TGCCA4,32,33,34,35. Meanwhile, half-sites containing the TGGCA motif have also been reported as sufficient for DNA binding and transcriptional activation, implying that DNA recognition might be more flexible than previously anticipated32,34,36. Despite these findings, NF1 proteins, including the isolated DBD, have not previously been purified to the level required for rigorous biophysical analysis, leaving the molecular mechanism underlying their DNA recognition unresolved.

To address these gaps, we expressed and purified full-length NFIA and its isolated DBD, facilitating a comprehensive analysis of their oligomerization and DNA-binding properties. Remarkably, structural analysis of the NFIADBD revealed that it adopts a monomeric state in solution, in contrast to the previously proposed dimeric model. Genome-wide ChIP-Seq analysis revealed that TGGCA half-sites are enriched within NFIA peak regions, while symmetric TGGCA(N3)TGCCA full-sites are also bound by NFIA. Functional binding assays showed comparable binding affinities for both motifs. To further elucidate the structural basis of DNA recognition, we determined the crystal structures of NFIADBD in complex with DNA containing these motifs. Our results validate the monomeric DNA-binding mode indicated by our biophysical analyses and provide detailed molecular mechanistic insights into sequence-specific recognition by NFIA. Since this family shows high sequence conservation, our data may fundamentally define the structural paradigm for NFI-DNA interactions.

Results

Characterization of NFIA and its DBD in solution

Previous studies have proposed that NFI proteins form a dimer via their double-stranded DNA-binding domains that facilitate DNA recognition and binding33,34,37,38. However, these conclusions were largely derived from analyses conducted in cell lysates or using crosslinking techniques, both of which may overlook other DNA-binding configurations. In cell lysates, unpurified NFI proteins can interact with other cellular components, such as proteins, nucleic acids, or cofactors, potentially creating artifacts that complicate accurate determination of the oligomeric state of a protein. Yet, detailed analyses of purified NFI family proteins or their isolated DBDs are limited, leaving a gap in the reliable characterization of their oligomerization properties and allowing the dimer theory to persist.

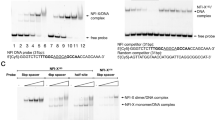

To address these limitations, we systematically expressed and purified both full-length human NFIA and its DNA-binding domain (NFIADBD, Fig. 1a), enabling rigorous analysis of their oligomeric states under controlled conditions. Optimized expression systems yielded full-length NFIA from HEK293 cells and NFIADBD from E. coli in sufficient quantities for downstream biophysical analysis. Both constructs included an N-terminal His₆–MBP tag to facilitate initial purification via nickel-affinity chromatography, with a TEV protease cleavage site introduced to minimize interference from the tag. After TEV cleavage, size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) was employed for further purification. The SEC profiles for both NFIA and NFIADBD revealed single, symmetric Gaussian peaks consistent with well-folded, monodisperse proteins, and elution volumes corresponding to monomeric molecular weights (Fig. 1b). Non-denaturing gel electrophoresis further confirmed that both NFIA and NFIADBD exist as monomers in solution (Fig. 1c). These results do not align with the previously proposed dimeric model and demonstrate that neither full-length NFIA nor its DBD undergoes dimerization under the tested conditions.

a Schematic showing the domain architecture of human NFIA and its conserved DNA-binding domain. The DNA-binding domain of NFIA (residues 13–175, referred to as NFIADBD) was used for structural studies. b Representative size-exclusion chromatography profiles of purified NFIA and NFIADBD using Superdex 200 increase column, with retention volumes of protein standards indicated for reference. c Native-PAGE analysis of purified NFIA and NFIADBD, confirming the oligomerization of the protein samples (representative of n = 3 independent experiments). d Crystal structure of NFIADBD, illustrated as a ribbon diagram (helices as spirals, strands as arrows, and loops as tubes), in two views. e Overlay of experimental scattering profiles (black) with back-calculated scattering profiles (red) for the NFIADBD. The inset shows the overlay of the crystal structure (red) with experimental (black) pair-distance distribution functions (PDDFs). f The NFIADBD crystal structure fits well in the SAXS ab initio envelope. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The structure of NFIADBD

Given that the NFIA DNA-binding domain is highly conserved and structurally ordered, whereas the remainder of the protein is largely unstructured, we focused on the NFIADBD for structural characterization. We successfully crystallized NFIADBD and determined its structure at a resolution of 3.2 Å (Supplementary Table 1). The crystal exhibits P41212 symmetry, with the asymmetric unit containing three polypeptide chains of NFIA, encompassing residues 13–173. Each NFIADBD molecule forms a single domain characterized by a distinct fold comprising six α-helices and two short, two-stranded β-sheets positioned on one side of the domain (Fig. 1d). The β-sheet region coordinates a zinc ion via three cysteines and one histidine, a feature reminiscent of the SMAD MH1 DNA-binding domain (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, the overall architecture of NFIADBD diverges significantly from the MH1 domain, particularly in its extended α-helical region, defining a distinct structural framework for the NFI DNA-binding domain family.

Despite the presence of three NFIADBD molecules in the asymmetric unit, SEC analysis confirmed that NFIADBD exists as a monomer in solution. To further characterize the solution conformation, we utilized small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). The scattering intensity I(q) versus momentum transfer q and the pair-distance distribution function (PDDF) (Fig. 1e) indicated a molecular mass of 24.8 kDa (Supplementary Table 2), consistent with the monomeric state observed in the crystal structure. The maximum dimension (Dmax) of 55 ± 3 Å aligns closely with the longest dimension observed in the crystal structure (53 Å). Moreover, the ab initio shape calculated from the SAXS data matched the monomeric crystal structure precisely (Fig. 1f). These findings validate the solution structure of NFIADBD and corroborate the architecture observed in the crystal structure, providing a consistent view of its structural properties using distinct methodologies.

Genome-wide NFIA DNA-binding specificity

To elucidate the genome-wide DNA-binding specificity of NFIA and gain further insight into its mechanistic binding patterns, we analyzed its preferred DNA motifs. Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-Seq) data for NFIA were processed using the HOMER algorithm to identify enriched sequence motifs39. Mapping of NFIA-bound peaks revealed significant enrichment in promoter regions (Supplementary Fig. 2a), consistent with its function as a transcription factor. Among these binding peaks, TGGCA-containing motifs emerged as the predominant binding motif, present in 37.4% of NFIA-bound genomic regions, with similar counts observed when using 10- or 18-nt motif windows (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2c). This result is consistent with the sequence motif for NFIA reported in the JASPAR database and corresponds to motifs identified in genes associated with fatty acid metabolism26,40. Additionally, the dyad-symmetric consensus sequence TGGCA(N3)TGCCA, which was not previously reported in JASPAR, was identified in 6.4% of NFIA-bound regions in our analysis (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2b). Notably, TGGCA-containing regions showed greater enrichment in genes associated with cellular metabolism and developmental processes (Supplementary Fig. 2d), underscoring the critical role of NFIA in these biological pathways. These findings provide insights into the cellular DNA-binding specificity of NFIA, expanding our understanding of NFIA beyond the traditionally recognized dyadic site.

a NFIA motif identification based on ChIP-Seq data (experiment ID ENCSR226QQM), obtained from ENCODE, and analyzed using the HOMER algorithm to identify enriched DNA motifs in NFIA-bound regions. Sequence logos derived from the ChIP-Seq analysis were compared with the JASPAR database (matrix ID MA0670.1) to validate motif similarity. b DNA sequences containing NFIA recognition motifs, comprising the half-site (DNA-S) and the full-site (DNA-L) motifs, were utilized in both functional and structural analyses. c, d Biolayer interferometry (BLI) binding profiles of NFIA and NFIADBD with DNA-S. Serial 2-fold dilutions of protein were used, and binding kinetics were analyzed using a 1:1 Langmuir binding model with ForteBio Data Analysis software. e, f BLI binding profiles of NFIA and NFIADBD with DNA-L, following the same experimental setup as DNA-S binding.

To further investigate NFIA’s DNA-binding mechanism, we employed biolayer interferometry (BLI) to evaluate its DNA-binding properties41. Based on the two DNA sequences uncovered by our NFIA ChIP-Seq data, DNA oligonucleotides were synthesized for functional binding assays: a 12-bp DNA-S containing the TGGCA half-site motif and an 18-bp DNA-L, incorporating the dyad-symmetric TGGCA(N3)TGCCA full-site motif (Fig. 2b). Both substrates were chemically synthesized with a biotin tag at the 5′ end of the forward strand to enable immobilization on an Octet SA biosensor for BLI-based analysis. Upon exposure to NFIA during the association phase, a significant wavelength shift was observed for both DNA-S and DNA-L, even at low protein concentrations, indicating strong and specific binding (Fig. 2c, e). BLI analysis revealed a 1:1 binding stoichiometry for both substrates, with dissociation constants (Kd) of 20.4 nM (R² = 0.9994) for DNA-S and 27.4 nM (R² = 0.9986) for DNA-L, demonstrating similar binding affinities. Additional assays with the isolated NFIADBD yielded comparable binding profiles and dissociation constants (Fig. 2d, f, Supplementary Table 4), and independent measurements using microscale thermophoresis (MST) produced similar Kd values for both DNA-S and DNA-L (Supplementary Fig. 3), further validating the robustness of the affinity measurements and confirming that the DNA-binding domain alone is sufficient for sequence-specific DNA recognition. Importantly, substitution of the TGGCA motif in DNA-S with either a polyT stretch or an unrelated CAGAC sequence completely abolished binding (Supplementary Fig. 4), supporting the sequence specificity of NFIA-DNA interactions. Collectively, these results reveal that NFIA binds DNA containing either the half-site or full-site motif with similar affinity in a sequence-specific manner.

Structure of NFIADBD bound to the TGGCA motif

To elucidate the structural basis of DNA recognition by NFIA, we initially conducted crystallization trials using the NFIADBD in the presence of the functional DNA-S (Fig. 3a). We obtained crystals of the protein-DNA complex and determined its structure at a resolution of 2.3 Å (Supplementary Table 1). The structure revealed that the complex consisted of a single NFIADBD molecule bound to a DNA-S duplex (NFIADBD:DNA-S), consistent with the SEC profile (Fig. 3b). In Fig. 3a, the right panel shows a view perpendicular to the axis of the dsDNA, highlighting the precise fit of the DNA within the NFIADBD. The left panel presents a view along the dsDNA axis, illustrating how one NFIADBD molecule binds the entire length of one helical turn of B-form DNA with a 1:1 binding stoichiometry. The crystal symmetry is C2, and the asymmetric unit contains one polypeptide chain (residues 13–173), two DNA strands, and one zinc ion. The NFIADBD:DNA-S structure demonstrated that the protein recognizes the 12-bp DNA duplex by inserting a loop into the major groove of the DNA, inducing conformational changes within the loop region while leaving the rest of the protein structure largely unaltered (Fig. 3c). The overall structure forms a compact complex, with a buried surface area of 736.2 Å2, indicative of specific protein-DNA binding. These observations provide direct structural evidence of the NFIA DNA recognition mechanism and its role in gene regulation.

a Crystal structure of the NFIADBD:DNA-S complex showing two views. The complex contains one NFIADBD (cyan) and a 12-bp double-stranded DNA (DNA-S) (blue/red). b Representative SEC profiles of purified NFIA and DNA-S complex. c Conformational change triggered by DNA binding. Superimposition of the apo form of NFIADBD (in limon) with the DNA-bound form of NFIADBD (in cyan). d Overlay of experimental scattering profiles (black) with back-calculated scattering profiles (red) for the NFIADBD:DNA-S. The inset displays the alignment of the crystal structure (red) with experimental pair-distance distribution functions (PDDFs) (black). e The crystal structure of the NFIADBD:DNA-S complex aligns well with the SAXS ab initio envelope, supporting its solution conformation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further confirm the formation of the NFIADBD:DNA-S complex in solution, we examined it using SAXS. Analysis of the SAXS data revealed a molecular mass of 25.3 kDa, which agrees with the crystal structure composition (26.2 kDa). Additionally, the Dmax value of 55 ± 3 Å matched the longest dimension observed in the crystal structure (Supplementary Table 2). To elucidate the solution structure of NFIADBD:DNA-S, an ab initio shape envelope was generated using the program DAMMIN. The back-calculated scattering profile for the crystal structure closely aligned with the experimental data (Fig. 3d, χ2 = 0.90), and the crystal structure fit remarkably well within this ab initio shape envelope (Fig. 3e). These findings confirm that the crystal structure accurately represents the assembly of the NFIADBD:DNA-S complex.

Molecular mechanism of DNA recognition by NFIA

Structural analysis of the NFIADBD:DNA-S complex revealed both sequence-specific and backbone interactions with the DNA, providing critical insights into the molecular basis of NFIA function as a transcription factor. The detailed protein-DNA interactions are summarized in Supplementary Table 3. Specifically, the sidechains of R38, K78, K81, Q110, and R121 interact with the phosphate backbone of the DNA (Fig. 4a), contributing to non-specific DNA binding. Sequence-specific recognition is primarily mediated by residues R116, A123, and K125. Among these, the sidechain of R116 forms two base-specific hydrogen bonds with the G6 base of strand 2, while A123’s carbonyl oxygen establishes a hydrogen bond with C8 of the same strand (Fig. 4a). Additionally, K125 plays a pivotal role by forming base-specific hydrogen bonds with G5 and G6 bases of strand 1, and its carbonyl oxygen interacts with C7 on the complementary strand (Fig. 4a). The schematic representation of key interactions is shown in Fig. 4b. These residues collectively create a positively charged surface on NFIADBD that engages both strands of the dsDNA in a 1:1 stoichiometric complex (Fig. 4c), targeting the TGGCA base-pairs positioned at the center of the major groove.

a Illustration of major protein-DNA interactions with NFIADBD (ribbon diagram in cyan, overlapped with a transparent molecular surface) and DNA-S (Strands 1 and 2 in blue/red, overlapped with composite omit 2mFo-DFc electron density map contoured at 2σ). Insets show detailed interactions between protein and DNA. b Schematic representation of protein-DNA interactions observed in the NFIADBD:DNA-S structure. c Electrostatic potential surface of NFIA at the DNA-binding interface. The electrostatic potential surface of NFIADBD was calculated using PyMOL, with positively charged regions depicted in blue and negatively charged residues highlighted in red. d Comparison of DNA-binding activity of NFIADBD and its mutants measured by BLI. e Relative binding affinity was calculated as WT KD ÷ mutant KD × 100. Each dot represents one independent experiment (n = 3); bars show mean ± SD. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To gain deeper insights into the functional mechanism of DNA binding, we performed site-directed mutagenesis coupled with BLI binding assays. Three key residues mediate DNA recognition: A123 interacts with the DNA through its carbonyl oxygen on the main chain, while R116 and K125 establish base-specific interactions via their sidechains. Accordingly, we introduced individual and combined mutations in R116 and K125 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Mutations in either residue significantly disrupted DNA-binding activity, as evidenced by a substantial reduction in wavelength shift during the association phase compared to wild-type NFIADBD (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 5). Quantitative analysis revealed that the R116A and K125A mutations each completely abolished detectable binding (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 4), highlighting the critical roles of these residues in sequence-specific DNA recognition. To further validate the functional significance of this binding mechanism, we performed dual-luciferase reporter assays using the pGL3 vector system, in which the firefly luciferase gene is driven by the native promoters of NFIA target genes ACACA and CPT226. Overexpression of wild-type NFIA significantly activated reporter expression, whereas the R116A/K125A mutant failed to induce transcriptional activation, consistent with its inability to bind DNA (Supplementary Fig. 6). Together, our structural and functional analyses provide a detailed understanding of the molecular mechanism by which NFIA engages with its target DNA.

Structural basis of TGGCA(N3)TGCCA motif recognition by NFIA

BLI assays demonstrated that NFIA binds both DNA-S and DNA-L with comparable specificity (Supplementary Table 4). To elucidate the mechanism underlying NFIA’s recognition of the dyad-symmetric sequence TGGCA(N3)TGCCA, we crystallized the NFIADBD in complex with DNA-L and determined its structure at a resolution of 2.7 Å (Supplementary Table 1). The crystal symmetry is P21, with the asymmetric unit containing two NFIADBD:DNA-L complexes. As the two complexes were structurally similar, and SEC data confirmed a 1:1 stoichiometry for NFIADBD binding to DNA-L, we focused on analyzing a single NFIADBD:DNA-L complex (Fig. 5a–c).

a The crystal structure of the NFIADBD:DNA-L complex is depicted from two perspectives. The complex consists of a single NFIADBD molecule (green) bound to an 18-bp double-stranded DNA (DNA-L) (purple/yellow). b Detailed interactions between NFIADBD and DNA-L are highlighted, illustrating both base-specific and backbone contacts. c Representative SEC profiles of the purified NFIADBD:DNA-L complex, confirming the formation of a 1:1 complex. d Schematic representation of protein-DNA interactions observed in the NFIADBD:DNA-L structure. e Molecular modeling of two NFIADBD molecules binding simultaneously to DNA-L. The model aligns NFIA (MolA) within the first major groove and projects it onto the second major groove of DNA-L. The circled region highlights potential steric clashes, suggesting that simultaneous binding of two molecules is not feasible. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The detailed interactions between NFIADBD and DNA-L are illustrated in Fig. 5b and summarized in Supplementary Table 3. Similar to the interactions observed in the DNA-S complex, residues R38, K78, K81, Q110, R121, and T145 mediate non-specific interactions with the DNA backbone. Sequence-specific recognition of the TGGCA base-pairs is facilitated by residues R116, A123, and K125. While the symmetric TGGCA motif was present within the DNA-L crystal structure, no protein-DNA interactions were observed involving this region (Fig. 5d). The symmetric motif was positioned within the major groove but remained unengaged by NFIA.

To investigate whether NFIA could simultaneously recognize both halves of the dyad-symmetric TGGCA(N3)TGCCA motif, we created a structural model aligning the first TGGCA base-pairs with the symmetric TGGCA motif. Although this alignment suggested the theoretical possibility of two NFIADBD molecules binding the same DNA duplex with a three-nucleotide spacer, the structural model revealed significant steric clashes between the two NFIA molecules if bound simultaneously (Fig. 5e). These clashes occur because the two major grooves of the DNA duplex are located on the same side, preventing simultaneous binding of two NFIA molecules (Fig. 5e). These findings are consistent with our functional assays, supporting the conclusion that NFIA binds the TGGCA(N3)TGCCA motif in a monomeric 1:1 binding mode. The structural evidence presented here resolves ambiguities surrounding DNA-binding by NFIA and provides a foundational framework for future investigations into its transcriptional regulatory roles.

Discussion

The molecular characterization of transcription factors is pivotal for elucidating their roles in development, physiological processes, and pathological conditions. Despite being studied for over three decades, the molecular mechanisms underlying DNA binding and transcriptional regulation by the NFI family of TFs remain incompletely understood. Here, we demonstrate that full-length human NFIA and its DBD function as monomers and exhibit specific DNA-binding activity. Through structural analyses of NFIADBD bound to DNA substrates containing TGGCA and dyad-symmetric TGGCA(N3)TGCCA recognition motifs, we elucidated the molecular basis of its sequence-specific recognition of the TGGCA motif within the major groove. Our findings establish NFIA as a TGGCA-binding protein. Moreover, the conserved nature of DNA-interacting residues across the NFI family suggests a shared mechanism of DNA recognition (Supplementary Fig. 7). These insights represent a substantial advance in our understanding of the NFI family and address a long-standing gap in their mechanistic characterization.

Our data establish the NFI DBD as a unique type of DNA-binding domain with distinct structural and functional properties. Although the JASPAR database places the NFI DBD into a family similar to the SMAD MH1 domain40, our results reveal significant differences between these DBD domains. The overall structure of the NFI DBD is very different from MH1 since it contains an extended α-helical region that mediates DNA interactions (Supplementary Fig. 1). Additionally, NFIADBD inserts a loop into the DNA major groove for sequence recognition, while MH1 relies on a β-hairpin for DNA binding (Supplementary Fig. 1). Furthermore, the sequence recognized by NFIADBD differs significantly from that of MH1 domains. NFI DBD recognizes the TGGCA motif, while MH1 recognizes the CAGAC Smad binding element, further supporting the classification of NF1 as a unique DNA-binding domain family42. Interestingly, SMAD proteins have also been shown to interact with 5GC-rich sequences43. These sequences reported all contain a central GGC motif within the major groove, alongside other GC-rich elements, aligning with the base-specific contacts observed in our NFIA–DNA complex. Consistent with this structural similarity of the DNAs, we tested a representative sequence from PDB entry 5MEY and found that NFIA binds it with an affinity comparable to its canonical TGGCA motif (Supplementary Fig. 4c), suggesting a broader sequence tolerance centered around GGC recognition.

Two structures of the human NFIX DNA-binding domain have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB IDs: 7QQD and 7QQE); these entries are not supported by published functional data. The apo structure of NFIX (PDB ID: 7QQE), resolved at 3.5 Å, shows a high degree of similarity to the NFIA structure, with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.76 Å (Supplementary Fig 8a). The NFIX structure in complex with dsDNA (5′-TTGGCAGGCAGCCAG-3′) is available at 2.7 Å resolution (PDB ID: 7QQD). However, this complex does not appear to be functionally relevant, as the dsDNA is positioned outside the protein and lacks base-specific interactions (Supplementary Fig. 8b, c). Notably, we did not observe such non-specific or peripheral DNA contacts in any of our NFIA–DNA structures, all of which exhibit clear and reproducible base-specific interactions. These limitations in prior structural data emphasize the importance of our findings, which provide functionally validated structural insights into the interaction of NFIA with DNA.

To validate the importance of the NFIA-DBD-mediated DNA recognition mechanism we uncovered, we employed AlphaFold to predict the structure of NFIADBD and its DNA-S complex. AlphaFold accurately predicted the overall structure of NFIADBD, except for the DNA-binding loop, likely due to its flexibility in the absence of DNA (Supplementary Fig. 9a). However, AlphaFold failed to predict the NFIA:DNA-S complex accurately, as the predicted protein-DNA interactions did not correspond to our experimental data (Supplementary Fig. 9b, c). This discrepancy underscores the importance of the dsDNA recognition mechanism revealed in our study. Since AlphaFold cannot predict these interactions, our work establishes a structural paradigm for NFI proteins. This insight highlights the value of experimental validation in understanding protein-DNA interactions.

Our findings suggest an alternative to the previously assumed dimeric DNA-binding model for NFI proteins. The dyad-symmetric TGGCA(N3)TGCCA sequence observed in earlier studies and in our ChIP-seq analysis suggested that a dimeric mode of binding does exist. However, our structural analyses demonstrated that NFIA cannot simultaneously bind two TGGCA base-pairs separated by a three-nucleotide spacer due to steric hindrance. Instead, the symmetric motif may enhance the DNA recognition efficiency of NFIA or serve as a binding site for this protein in conjunction with cellular cofactors. Future studies are needed to explore the potential roles of cofactors in NFIA-mediated DNA binding. By providing a structural basis for NFIA recognition of DNA containing TGGCA motifs, our work lays the groundwork for drug design and screening efforts targeting NFIA, particularly in therapeutic applications such as osteoarthritis treatment.

Methods

Expression and purification of human NFIA and its DBD

The cDNA encoding full-length human NFIA was synthesized and cloned into the pcDNA 3.1 vector, incorporating an N-terminal His6-MBP tag followed by a TEV protease cleavage site. Protein was expressed using the Expi293 expression system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Five days post-transfection, the cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −80 °C for subsequent protein purification.

The binding domain of NFIA (residues 13–175) was cloned into the pMAL-c5X vector with a His6-MBP tag at the N terminus, followed by a TEV cleavage site. The clone was overexpressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) (Beyotime). Cultures were grown to mid-log phase at 37 °C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium, induced by the addition of beta-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 1 mM. The cells were incubated for an additional 16 h at 18 °C, harvested by centrifugation, and stored at −80 °C until protein purification.

Both NFIA and its DNA-binding domain (DBD) were purified using the same method at room temperature, using an AKTA chromatography system with prepacked columns (GE Healthcare). Cells were suspended in buffer A [30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM TCEP, and 25 mM imidazole], lysed by sonication, and centrifuged at 26,916 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was applied onto a 5-ml His Trap FF column pre-equilibrated in buffer A. The column was washed with buffer A to baseline, and the fusion protein was eluted with buffer B [30 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM TCEP, and 300 mM imidazole]. The fusion protein was digested overnight with 0.2 mg ml−1 TEV protease. The digestion solution was buffer-exchanged to buffer A and applied onto a 5-ml His Trap FF column pre-equilibrated in buffer A. The target protein was isolated in the column flow-through and was concentrated to 5 ml, which was then applied onto a Superdex 75 gel filtration column pre-equilibrated in buffer C [25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, and 1 mM TCEP]. The protein was collected from peak fractions, and the quality was analyzed by SDS gel electrophoresis.

ChIP-sequencing data analysis

NFIA ChIP-Seq data (ENCSR226QQM) were obtained from the ENCODE database. Raw sequencing reads were aligned to the human reference genome assembly (hg38) using the findMotifsGenome.pl and annotatePeaks.pl functions within the HOMER software with default parameters39. Significantly enriched de novo binding motifs were identified and annotated with motif logos generated for visualization using the WebLogo software44. The enrichment p-values reported in Supplementary Fig. 2a were calculated automatically by HOMER’s annotatePeaks.pl script during the peak annotation step. Briefly, HOMER evaluates the statistical significance of peak enrichment across distinct genomic annotations (e.g., promoters, exons, introns, intergenic regions) by comparing the observed number of peaks within each annotation category to the expected number, based on the fraction of the genome occupied by that category. Statistical significance is assessed using a hypergeometric distribution, and the resulting p-values are log-transformed and reported as logP scores39. ChIP-Seq peak sets containing either the TGGCA half-site motif or the dyad-symmetric motif are provided as Supplementary Data files.

Biolayer interferometry binding assay

The DNA-binding activities of NFIA and its mutants were assessed using biolayer interferometry (BLI) on an Octet-K2 device. Biotin-labeled DNA and its complementary strand were chemically synthesized (General Biol), annealed, and loaded onto activated Octet SA biosensors. The DNA sequences used were 5′-Biotin-AGTTGGCAAGTC-3′ and 5′-GACTTGCCAACT-3′ for DNA-S, and 5′-Biotin-AGTTGGCAAGATGCCATC-3′ and 5′-GATGGCATCTTGCCAACT-3′ for DNA-L. The DNA substrates were loaded at a concentration of 0.5 ng/μL for DNA-L and 1 ng/μL for DNA-S in BLI buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM ZnCl2, pH 7.4) until saturation. The loaded biosensors were then incubated with serial dilutions of NFIA or its mutants in BLI buffer. Association and dissociation were measured at 30 °C and fitted using ForteBio Data Analysis software.

Microscale thermophoresis (MST) assay

MST experiments were performed using a Monolith NT.115 instrument (NanoTemper Technologies) with standard capillaries in a total reaction volume of 10 μL. Cy5-labeled DNA substrates were diluted to a final concentration of 20 nM. Serial dilutions of purified NFIADBD were prepared by performing 15 two-fold serial dilutions starting from a 2 μM stock concentration, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. Samples were incubated for 60 min to allow equilibrium binding prior to loading into capillaries. Measurements were conducted at 30 °C with 20% LED excitation power, 40% MST power, and detection via the NanoRed fluorescence channel. Data were analyzed using MO Affinity Analysis Software v2.3, and dissociation constants (Kd) were calculated using the standard model based on the law of mass action.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

To evaluate transcriptional activation by NFIA, a dual-luciferase reporter assay was performed using HEK293 cells (ATCC, CRL-1573). Briefly, cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density to reach approximately 60% confluence on the day of transfection. The 2-kb upstream promoter regions of the human ACACA and CPT2 genes were cloned into the pGL3-Basic firefly luciferase reporter vector (Servicebio). Cells were co-transfected with either wild-type NFIA, mutant NFIA (R116A/K125A), or an empty pcDNA 3.1 control vector using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), along with the pRL-TK Renilla luciferase vector (Promega), which served as an internal control for normalization. Each condition was transfected in triplicate. After 48 h, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Yeasen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity to account for variation in transfection efficiency.

Crystal structure determination

The fresh purified NFIADBD protein in buffer C was concentrated to 10 mg ml−1 and used for crystallization immediately. Crystals were grown by mixing the protein solution with an equal volume of reservoir solution [0.1 M CHES (pH 9.5), and 30% (w/v) PEG 3000], using the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion method. For crystallization of the protein-DNA complexes, DNA oligos (Fig. 2b) were purchased (General Biol) and annealed without further purification. The purified NFIADBD protein (10 mg ml−1) was mixed with either DNA-S or DNA-L at a molar ratio of 1:1.2 and incubated on ice for 30 min. Crystals of the NFIADBD:DNA-S complex were grown by mixing the protein-DNA solution with an equal volume of reservoir solution [0.1 M Bis-Tris Propane (pH 7.0), and 1.5 M Ammonium Sulfate], while crystals of the NFIADBD:DNA-L complex were grown using a reservoir solution [0.1 M Tris (pH 7.0), and 20% (w/v) PEG 2000]. For data collection, the crystals were soaked in a reservoir solution containing 20% (v/v) ethylene glycol and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. X-ray (λ = 0.9795 Å) diffraction data were collected at −173 °C using a PILATUS3 S 6M detector at the BL18U1 beamline of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) and processed using the program HKL-300045. For NFIADBD, the structure was solved by molecular replacement using the PHASER program46 with the NFIA AlphaFold model as the search model. For the NFIADBD:DNA complexes, the structures were solved by molecular replacement using the NFIADBD structure, and DNA molecules were built de novo based on the electron density map. Model building and structure refinement were performed using Coot47 and Phenix48. The final structures were evaluated using the wwwPDB49 validation server. Data collection and structure statistics are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Small-angle X-ray scattering analysis

SAXS data were recorded at the SSRF beamline BL19U2 using a PILATUS3 X 2 M detector. The wavelength (λ) of X-ray radiation was 1.033 Å, and the momentum transfer q was recorded in the range 0.006–0.39 Å−1 [q = (4π/λ)sinθ, where 2θ is the scattering angle]. The NFIADBD and NFIADBD:DNA-S complexes were concentrated to 4 mg ml−1, respectively, and pre-equilibrated in a SAXS buffer [25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP, and 5% (v/v) glycerol] for data collection. For each sample, scattering profiles were measured at three solute concentrations (4-, 2-fold dilution, and stock solution) to remove the scattering contribution due to inter-particle interactions and to extrapolate the data to infinite dilution. A set of 20 two-dimensional images was recorded for each buffer or sample solution using a flow cell, with an exposure time of one second per image to minimize radiation damage and optimize the signal-to-noise ratio. The images were reduced on site to one-dimensional scattering profiles using BioXTAS RAW.

The SAXS data were analyzed using IGOR-Pro (WaveMetrics) and the ATSAS suite50, similar to previously described protocols51,52. Briefly, the forward scattering intensity I(0) and the radius of gyration (Rg) were calculated from the infinite dilution data at low q values in the range of qRg < 1.3, using the Guinier approximation in PRIMUS53. These parameters were also estimated from the scattering profile with a broader q range of 0.006–0.30 Å−1 using the indirect Fourier transform method implemented in the program GNOM, along with the pair-distance distribution function (PDDF) and the maximum dimension of the protein (Dmax). The molecular weight was calculated using the SAXS MoW method, which is independent of protein concentration. Low-resolution ab initio shape envelopes were calculated using DAMMIN, which generates models represented by an ensemble of densely packed beads, using scattering profiles within the q range of 0.006–0.30 Å−1. A total of 20 independent models were created and averaged by DAMAVER54, superimposed by SUPCOMB based on the normalized spatial discrepancy criteria, and filtered using DAMFILT to generate the final model. The theoretical scattering intensity of the crystal structure was calculated and fitted to the experimental scattering intensity using CRYSOL55. Data collection and scattering-derived parameters are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Structure factors and atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank [www.rcsb.org] with the accession codes 9JH4 (https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb9JH4/pdb), 9JH2 (https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb9JH2/pdb), and 9LC2 (https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb9LC2/pdb). ChIP-seq data analyzed in this study were obtained from ENCODE (www.encodeproject.org) with the accession code ENCSR226QQM (https://doi.org/10.17989/ENCSR226QQM), and processed peak sets annotated for the TGGCA half-site and the TGGCA(N3)TGCCA dyad-symmetric motif are provided in Supplementary Data 1–2. Author-generated structural models (model for two DBDs on DNA-L and AlphaFold3 models for NFIADBD and NFIADBD:DNA-S) are provided as Supplementary Data 3–5. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Gronostajski, R. M. Roles of the NFI/CTF gene family in transcription and development. Gene 249, 31–45 (2000).

Pjanic, M. et al. Nuclear factor I revealed as family of promoter binding transcription activators. BMC Genomics 12, 1–10 (2011).

Borgmeyer, U., Nowock, J. & Sippel, A. E. The TGGCA-binding protein: a eukaryotic nuclear protein recognizing a symmetrical sequence on double-stranded linear DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 12, 4295–4311 (1984).

Gronostajski, R. M., Adhya, S., Nagata, K., Guggenheimer, R. A. & Hurwitz, J. Site-specific DNA binding of nuclear factor I: analyses of cellular binding sites. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5, 964–971 (1985).

Jones, K. A., Kadonaga, J. T., Rosenfeld, P. J., Kelly, T. J. & Tjian, R. A cellular DNA-binding protein that activates eukaryotic transcription and DNA replication. Cell 48, 79–89 (1987).

Nagata, K., Guggenheimer, R. A., Enomoto, T., Lichy, J. H. & Hurwitz, J. Adenovirus DNA replication in vitro: identification of a host factor that stimulates synthesis of the preterminal protein-dCMP complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79, 6438–6442 (1982).

Nagata, K., Guggenheimer, R. A. & Hurwitz, J. Specific binding of a cellular DNA replication protein to the origin of replication of adenovirus DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 80, 6177–6181 (1983).

Harris, L., Genovesi, L. A., Gronostajski, R. M., Wainwright, B. J. & Piper, M. Nuclear factor one transcription factors: divergent functions in developmental versus adult stem cell populations. Dev. Dyn. 244, 227–238 (2015).

Qian, F., Kruse, U., Lichter, P. & Sippel, A. E. Chromosomal localization of the four genes (NFIA, B, C, and X) for the human transcription factor nuclear factor I by FISH. Genomics 28, 66–73 (1995).

Rupp, R. A. et al. Chicken NFI/TGGCA proteins are encoded by at least three independent genes: NFI-A, NFI-B and NFI-C with homologues in mammalian genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 2607–2616 (1990).

Alevizopoulos, A. et al. A proline-rich TGF-beta-responsive transcriptional activator interacts with histone H3. Genes Dev. 9, 3051–3066 (1995).

Alevizopoulos, A. & Mermod, N. Antagonistic regulation of a proline-rich transcription factor by transforming growth factor β and tumor necrosis factor α. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 29672–29681 (1996).

Wang, W. et al. Nuclear factor I coordinates multiple phases of cerebellar granule cell development via regulation of cell adhesion molecules. J. Neurosci. 27, 6115–6127 (2007).

Bunt, J. et al. Combined allelic dosage of Nfia and Nfib regulates cortical development. Brain Neurosci. Adv. 1, 2398212817739433 (2017).

Chen, K.-S., Lim, J. W., Richards, L. J. & Bunt, J. The convergent roles of the nuclear factor I transcription factors in development and cancer. Cancer Lett. 410, 124–138 (2017).

Deneen, B. et al. The transcription factor NFIA controls the onset of gliogenesis in the developing spinal cord. Neuron 52, 953–968 (2006).

Lu, W. et al. NFIA haploinsufficiency is associated with a CNS malformation syndrome and urinary tract defects. PLoS Genet. 3, e80 (2007).

Mason, S., Piper, M., Gronostajski, R. M. & Richards, L. J. Nuclear factor one transcription factors in CNS development. Mol. Neurobiol. 39, 10–23 (2009).

das Neves, L. et al. Disruption of the murine nuclear factor IA gene (Nfia) results in perinatal lethality, hydrocephalus, and agenesis of the corpus callosum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 11946–11951 (1999).

Piper, M. et al. NFIA controls telencephalic progenitor cell differentiation through repression of the Notch effector Hes1. J. Neurosci. 30, 9127–9139 (2010).

Shu, T., Butz, K. G., Plachez, C., Gronostajski, R. M. & Richards, L. J. Abnormal development of forebrain midline glia and commissural projections in Nfia knock-out mice. J. Neurosci. 23, 203–212 (2003).

Gobius, I. et al. Astroglial-mediated remodeling of the interhemispheric midline is required for the formation of the corpus callosum. Cell Rep. 17, 735–747 (2016).

Koehler, U. et al. A novel 1p31. 3p32. 2 deletion involving the NFIA gene detected by array CGH in a patient with macrocephaly and hypoplasia of the corpus callosum. Eur. J. Pediatr. 169, 463–468 (2010).

Lu, W., Quintero-Rivera, F., Fan, Y., Alkuraya, F. & Donovan, D. NFIA haploinsufficiency is associated with a CNS malformation syndrome and urinary tract. PLoS Genet. 3, e80 (2007).

Negishi, Y. et al. Truncating mutation in NFIA causes brain malformation and urinary tract defects. Hum. Genome Var. 2, 1–4 (2015).

Wang, C. et al. NFIA regulates articular chondrocyte fatty acid metabolism and joint homeostasis. Sci. Transl. Med. 17, eadm9488 (2025).

Chen, D. et al. Osteoarthritis: toward a comprehensive understanding of pathological mechanism. Bone Res. 5, 16044 (2017).

Tong, L. et al. Current understanding of osteoarthritis pathogenesis and relevant new approaches. Bone Res. 10, 60 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Current cutting-edge omics techniques on musculoskeletal tissues and diseases. Bone Res. 13, 59 (2025).

Altmann, H., Wendler, W. & Winnacker, E.-L. Transcriptional activation by CTF proteins is mediated by a bipartite low-proline domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 3901–3905 (1994).

Mermod, N., O’Neill, E. A., Kelly, T. J. & Tjian, R. The proline-rich transcriptional activator of CTF/NF-I is distinct from the replication and DNA binding domain. Cell 58, 741–753 (1989).

Roulet, E. et al. Experimental analysis and computer prediction of CTF/NFI transcription factor DNA binding sites. J. Mol. Biol. 297, 833–848 (2000).

Armentero, M.-T., Horwitz, M. & Mermod, N. Targeting of DNA polymerase to the adenovirus origin of DNA replication by interaction with nuclear factor I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 11537–11541 (1994).

Gounari, F. et al. Amino-terminal domain of NF1 binds to DNA as a dimer and activates adenovirus DNA replication. EMBO J. 9, 559–566 (1990).

Gronostajski, R. M. Analysis of nuclear factor I binding to DNA using degenerate oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 14, 9117–9132 (1986).

Wuarin, J., Mueller, C. & Schibler, U. A ubiquitous CCAAT factor is required for efficient in vitro transcription from the mouse albumin promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 214, 865–874 (1990).

Kruse, U. & Sippel, A. E. Transcription factor nuclear factor I proteins form stable homo-and heterodimers. FEBS Lett. 348, 46–50 (1994).

Goyal, N., Knox, J. & Gronostajski, R. M. Analysis of multiple forms of nuclear factor I in human and murine cell lines. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 1041–1048 (1990).

Heinz, S. et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38, 576–589 (2010).

Rauluseviciute, I. et al. JASPAR 2024: 20th anniversary of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, D174–D182 (2024).

Sultana, A. & Lee, J. E. Measuring protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid interactions by biolayer interferometry. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. 79, 19.25.1–19.25.26 (2015).

Shi, Y. et al. Crystal structure of a Smad MH1 domain bound to DNA: insights on DNA binding in TGF-β signaling. Cell 94, 585–594 (1998).

Martin-Malpartida, P. et al. Structural basis for genome wide recognition of 5-bp GC motifs by SMAD transcription factors. Nat. Commun. 8, 2070 (2017).

Crooks, G. E., Hon, G., Chandonia, J.-M. & Brenner, S. E. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190 (2004).

Minor, W., Cymborowski, M., Otwinowski, Z. & Chruszcz, M. HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution–from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 859–866 (2006).

McCoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 (2007).

Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004).

Adams, P. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol. Crystallogr 65, 1074 (2009).

Berman, H. M. et al. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242 (2000).

Petoukhov, M. V. et al. New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 45, 342–350 (2012).

Song, H. et al. The functional cycle of Rnt1p: five consecutive steps of double-stranded RNA processing by a eukaryotic RNase III. Structure 25, 353–363 (2017).

Song, H. et al. Structure and activity of PPX/GppA homologs from Escherichia coli and Helicobacter pylori. FEBS J. 287, 1865–1885 (2020).

Konarev, P. V., Volkov, V. V., Sokolova, A. V., Koch, M. H. & Svergun, D. I. PRIMUS: a Windows PC-based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 1277–1282 (2003).

Volkov, V. V. & Svergun, D. I. Uniqueness of ab initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36, 860–864 (2003).

Svergun, D., Barberato, C. & Koch, M. H. CRYSOL–a program to evaluate X-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 28, 768–773 (1995).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Prof. Xin Chen (University of Macau) for providing valuable resources and support. This work was supported by the Macau Science and Technology Development Fund (0068/2023/ITP2 and 0143/2025/ITP2, H.S.; 0007/2022/AKP, X.C.), University of Macau (MYRG-GRG2024-00283-ICMS-UMDF, H.S.; SRG2023-00054-ICMS, H.S.), The State Key Laboratory of Mechanism and Quality of Chinese Medicine (005/2023/SKL, H.S.), Basic Research Program of Jiangsu (BK20243030, Z.L.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82272508, J.T.), Hunan Health Commission Key Clinical Specialty Major Research Project (No. Z2023033, J.T.) and Chinese National Key Clinical Specialty (Orthopedics, J.T.). The X-ray crystallography experiments were carried out with the support of Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Beamline B18U1 (proposal 2024-NFPS-JJ-501348, H.S.), with expert assistance from beamline staff member Yijun Gu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S. and H.S. conceived the project. C.Z., Y.W., and X.C. prepared protein samples. C.Z. conducted binding assays and analyzed the experimental data. D.X., H.X., and J.T. performed luciferase assays. C.Z., Z.L., and H.S. performed X-ray crystallography experiments and carried out subsequent data analysis. S.L. and X.L. conducted ChIP-Seq analysis and designed the DNA constructs. J.Z. and X.F. performed SAXS experiments and analysis. J.S. and H.S. supervised the project. J.S. and H.S. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, C., Xiao, D., Luo, Z. et al. Structural basis for genome-wide site-specific DNA recognition by Nuclear Factor IA. Nat Commun 17, 917 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67641-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67641-4