Abstract

Electrochemical dechlorination provides a sustainable method to treat chlorinated volatile organic compounds polluted water with producing value-added hydrocarbon. However, dechlorination of dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) generates *CH3 and *CH2Cl intermediates, which are highly unstable due to lack of efficient hyperconjugation from neighboring carbon sites. Herein, we report that cobalt phthalocyanine (CoPc) grafts onto sulfur-doped graphene toward efficient electrocatalysis of CH2Cl2 dechlorination at moderate potentials. It reveals that sulfoxide groups within graphene linked to Co sites by an axial coordination, resulting in an electron donation effect to decrease the barriers of elemental dechlorination step. While in situ electrochemically generates [Co1+Pc]⁻ species mediated the electron transfer from Co sites to CH2Cl2. The production rate of CH4 is significantly enhanced compares to the current level, and an additional case of producing C2H4 and C2H6 is achieved. For potential practical application, the electrochemical dechlorination of a diluted CH2Cl2 solution is validated in an electrofiltration module setup by an efficient flow-through mode.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) represents one of the most significant chlorinated volatile organic compounds (CVOCs) with low molecular weights that have been widely used as solvents or cleaning agents in various fields of paint strippers, metal degreaser and the pharmaceutical industry, etc.1,2,3. However, CH2Cl2 is of high toxicity, which can be persistent in the ecological environment to seriously threaten life health4,5. To degrade CH2Cl2 is mainly realized by thermal and advanced oxidation6,7,8,9,10. While these approaches are operative to completely mineralize CH2Cl2, they require significant energy input and complicated systems to prevent the formation of harmful byproducts (e.g., dioxins and furans)6,11,12. Alternatively, electrochemical dechlorination reduction (EDR) in water powered by renewable energy provides a sustainable approach to degrade CH2Cl2 through cleaving C-Cl bonds and simultaneously generates value-added hydrocarbon compounds through water-enabled protonation13,14,15. However, EDR in water needs to compete with the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) for overlapped working potentials, resulting in decreased Faradaic efficiencies (FEs) of cleaving C-Cl bonds and protonating CH2Cl216,17,18,19. Such an issue is highly detrimental to the EDR performance, limiting broad-scale up applications.

Metal phthalocyanines (MPcs) represent a type of well-established molecular catalysts, which contain planar macrocyclic geometry to exhibit low steric hindrance for chemisorbing a variety of small molecules20,21,22. Both the macrocyclic planes and axial positions of MPcs can be systematically regulated to optimize the chemisorption of substrates for the appropriate substrate activation22,23,24,25. In addition, the metal sites of MPcs generally exhibit relatively weak chemisorption toward H+/*H species, causing sluggish HER kinetics26,27,28. These dominant characters make MPcs highly potential for selective EDR. For instance, Wang et al. demonstrated that CoPc loaded on carbon nanotubes efficiently electrocatalyzed dechlorination of 1,2-dichloroethane, competing with trivial HER events14,15,29. However, the *CH3 or *CH2Cl intermediate30,31, which potentially emerges in the EDR of CH2Cl2, is unstable due to lack of efficient hyperconjugation from neighboring carbon sites. This leads to relatively high barriers in the dechlorination of CH2Cl2 compared to cases of treating CVOCs with longer carbon chains. In addition, the elemental pathway of dechlorination has not yet been fully clarified, especially lacking insights into the dynamic interfacial electron transfer from catalysts to CH2Cl2. Thus, it requires further investigations of MPcs-based EDR electrocatalysts with tailored electronic states to stabilize reactive *CH3 and *CH2Cl intermediates, thereby enhancing EDR selectivity and activity of CH2Cl2 together with elucidating the reaction pathway.

On the basis of the aforementioned considerations, we report that CoPc grafted onto sulfur-doped graphene (CoPc-SG) at a mild condition functioned as an efficient electrocatalyst for the EDR of CH2Cl2. The binding of CoPc is accomplished by sulfoxide groups doped in graphene, providing an axial coordination environment to the Co sites. Such an axial binding resulted in an electron donation effect to Co sites that facilitated EDR. It identified that the electron transfer from Co sites to CH2Cl2 was realized through electrochemical generation of [Co1+Pc]⁻ species serving as the electron media. It afforded a production rate (PR) of CH4 significantly enhanced compared to the current reported level, as well as an additional case of C2H4 and C2H6 production. For potential practical application, the EDR process was examined toward diluted CH2Cl2 solution by an electrofiltration module setup in an efficient flow-through operation mode. In one single-pass filtration, 98% of CH2Cl2 was removed with CH4 conversion efficiency of 32.7%.

Results

Synthesis of CoPc-based catalysts

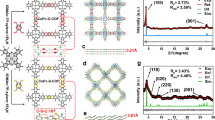

Graphene oxide (GO) was first synthesized following a modified Hummers’ method32. The GO aqueous solution was reacted with thioacetamide under hydrothermal conditions to generate a sulfur-doped graphene (SG, Table S1). Then CoPc complex was linked to SG under a mild condition (80 °C, 12 h, N, N-dimethylformamide)25, and the as-derived sample was denoted as CoPc-SG (all details have been provided in the Supplementary information, SI). The loading amounts of CoPc on SG were approximately 6.62 × 10−7 mol mgSG−1 by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, Table S2). Scanning and transmission electron microscopic (SEM/TEM, Figs. 1a and S1, S2) images revealed the typical graphene characteristics of CoPc-SG without observable metal-based nanostructures or bulk aggregates. Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX, Fig. S3) mapping images showed a homogeneous distribution of Co elements across those carbon layers. Raman spectra revealed that CoPc-SG contained both the bonding characters of CoPc and SG (Fig. S4)33,34,35, which verified the successful linking between the two components. X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS, Figs. 1b and S5 also presented the CoPc characters of CoPc-SG according to the dominant Co 2p3/2 (780.3 eV), Co 2p1/2 (795.8 eV) and N 1 s signals. The S sites remained as two forms of carbonized (163.4 eV) and oxidized (167.7 eV) sulfur species, ongoing from SG to CoPc-SG (Fig. 1c)36,37,38.

a A representative TEM image of CoPc-SG. XPS surveys of Co 2p (b) and S 2p (c) core electron levels of SG, CoPc, and CoPc-SG. d UV-Vis spectra of CoPc, SG and CoPc-SG. e Co K-edge XANES data. f FT-EXAFS data in R space. g FT-EXAFS fitting curves of CoPc-SG in R space. The inset is the schematic model of CoPc-SG. WT-EXAFS plots of CoPc (h) and CoPc-SG (i). Source data is provided as a Source Data file.

Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis, Fig. 1d) spectra presented the characteristic B and Q bands of CoPc-SG. The Q band at 663 nm is attributed to the a1u(π)-eg(π*) transition from the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), showing a significant red shift compared to the transition of pristine CoPc. This suggests a ligand modification occurring at the axial position of Co sites24,39. X-ray absorption spectroscopy was employed to analyze the oxidation states and coordination spheres of Co sites, referring to the Co foil, CoO, Co3O4 and CoPc standards. In the normalized X-ray absorption near-edge spectra (XANES, Fig. 1e), CoPc-SG exhibited a discernible shift to a lower energy compared to the pristine CoPc, which is consistent with the shift in the corresponding electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR, Fig. S6) data. According to the Fourier-transformed k3-weighted extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS, Fig. 1f), the intensity of the first sphere is enhanced going from CoPc to CoPc-SG. Such a result reflected the increased coordination number of Co sites upon interacting with SG. Moreover, the wavelet transform (WT) contour plots (Fig. 1h, i) exhibited a positive shift of k value from the maximum intensity at 7.45 Å−1 in CoPc-SG to 7.05 Å−1 in CoPc, suggesting the tuned coordination of Co sites by the support of SG40,41. As examined by the least squares EXAFS fitting (Fig. 1g, Figs .S7, S8 and Table S3) it revealed that the Co site of CoPc-SG is made of four Co-N scattering paths (1.87 Å) by the planar Pc ligation, and one Co-O scattering path with slightly prolonged distance (1.88 Å), while the pristine CoPc only contains the four Co-N paths. This supports the axial modification of Co sites in CoPc-SG, which is consistent with the UV-Vis data.

Electrocatalytic measurements

The EDR performance was evaluated in a gas-tight H-type cell using a three-electrode setup. An Ar carried CH2Cl2 vapor was continuously fed into 0.1 M K2HPO4 (pH = 8.8) at the ambient condition. The high ionic conductivity and buffering capability of the electrolyte ensured durable electrochemical measurement conditions (all potentials refer to the reversible hydrogen electrode, RHE, if not specified). As a main control sample, a reduced OG was synthesized from GO by the same hydrothermal method without introducing any dopants, which linked to CoPc (denoted as CoPc-OG, Figs. S9–S12), following the same procedures as the synthesis of CoPc-SG. A series of chronoamperometric curves presented that CoPc-SG afforded reduced overpotentials with enhanced currents compared to CoPc-OG (Fig. 2a). In-line gas chromatographic (GC) analysis identified the reduction products of EDR as CH4, C2H4 and C2H6 with a fraction of methyl chloride (CH3Cl) (Figs. 2b, c and S13). Apparently, CoPc-SG afforded higher dechlorination efficiency than CoPc-OG by \({{\mbox{FE}}}_{{{\mbox{CH}}}_{4}}\) and \({{\mbox{FE}}}_{{{\mbox{C}}}_{2}}\) up to 62.3% and 13.2%, while a minimal fraction of competent H2 was detected. Correspondingly, CoPc-SG increased the PRs of CH4 and C2 products by more than 6-fold compared to the cases of CoPc-OG at a typical potential of −0.68 V, which reached 53.9 mmol g−1 h−1 and 10.08 mmol g−1 h−1, respectively (Fig. 2d, e). Note that compared to previous works, we reported that the PR of CH4 was significantly enhanced, and an additional case of emerging C2 products (Fig. 2f and Table S4). In the meantime, a quantitative analysis of chloride ions released into the electrolyte was conducted by ion chromatography (IC), verifying that CoPc-SG afforded higher FEs of dechlorination ions compared to CoPc-OG (Fig. S14). Under the same condition, the pristine SG barely showed any EDR activity, indicating the active sites originated from CoPc (Fig. S15). The pristine CoPc without the carbon supports also exhibited significantly degraded FEs and currents of EDR, suggesting that the molecular dispersion of CoPc on the carbon supports is critical to achieve such high EDR performance42. By normalizing the partial reduction currents with the amounts of CoPc exposed on the electrode surfaces (Fig. 2g and Table S5), the TOFs for CH4 and C2 production were assessed. At −0.68 V, the TOFs were enhanced by more than 8-fold for CH4 production, and 7-fold C2 production transiting from CoPc-OG to CoPc-SG, revealing the intrinsically improved dechlorination activity of CoPc by the SG linkage (Fig. 2h, i).

a Total current densities of EDR at various potentials on CoPc-SG and CoPc-OG. FEs of CH4 (b) and C2 (c) production. PRs of CH4 (d) and C2 compounds (e). f PRs on various EDR catalysts. g Partial current densities of CH4 and C2 production. The error bars represent standard deviations from two independent measurements. TOFs of Co sites for CH4 (h) and C2 (i) production. The error bars represent standard deviations from three independent measurements. Source data is provided as a Source Data file.

In order to verify the EDR process on CoPc-SG, an in situ attenuated total reflection-Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy was conducted under the same conditions as set in the H-type electrolytic cell (Fig. S16). At an open circuit potential (OCP), the emerged IR peaks at 744 cm−1 and 1258 cm−1 are attributed to the C-Cl symmetric stretching and C-H bending vibration of CH2Cl229,43,44. As the potential was made more negative on the CoPc-SG catalyst, a new band appeared at 1448 cm−1. This band, which is absent on the pristine SG support, can be attributed to the C-H deformation vibration of *CH345. Meanwhile, doublet bands emerged at 2989/3008 cm−1 corresponding to the asymmetric stretching vibration of CH4, indicating the dechlorination process46. In contrast, on the pristine SG that only afforded HER events, the peak intensities of C-Cl and C-H vibration are relatively weak, which even decreased with applying reduction potentials, suggesting very weak chemisorption of CH2Cl2 in the absence of CoPc. Correspondingly, there are no vibrations of CH4 being observed. We further conducted EPR spin-trapping experiments using 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) to probe the EDR intermediates (Fig. S17). The electrolyte exhibited a characteristic six-line pattern with the electrocatalysis of EDR. The hyperfine splitting constants (AN = 16.1 G, AH = 23 G) agree with the literature values of the DMPO-•CH3 adduct47,48, indicating the generation of *CH3 intermediate. Besides, note that the EDR processes involved the formation of CH3Cl, which should be realized through the protonation of *CH2Cl intermediate49,50.

An insight into dechlorination mechanism

We conducted the density functional theory (DFT) calculations to gain an insight into the CoPc-based EDR process (the atomic coordinates of the optimized computational models are provided in Supplementary Data 1). According to previous studies25, sulfoxide (-SO)/sulfone (-SO2)/sulfonic (-SO3) groups of SG, and carboxyls (-CO2) of OG were considered as typical groups that can link to CoPc, and established the heterogeneous structures of CoPc in CoPc-SG and CoPc-OG, respectively. In the case that CoPc is immobilized onto carbon supports through the Van der Waals force, which does not affect the intrinsic activity in the DFT calculation, a free-standing CoPc is considered51,52. As revealed by the differential charge distribution, CoPc-SO exhibited a prominent electron transfer region at the molecule-graphene interface, which is broader than that in CoPc-CO2 (Fig. 3a). A clear change in Bader charges for CoPc in CoPc-SO was +1.62 e−, which turned to be −0.48 e− in CoPc-CO2. Thus, the sulfoxide group generally exhibited an electron-donating effect to CoPc, which is consistent with the energy shift observed in the XANES data. While the carboxyl group had the inverse effect of electron withdrawing. Based on partial density of state (PDOS, Fig. 3b), the low-to-medium spin transition ongoing from CoPc-CO2 to CoPc-SO facilitated the d orbital filling of Co sites that enhanced the Co-O bond energy. Correspondingly, the interaction energies of the molecule-graphene interface were calculated to be −0.96 eV for CoPc-SO and 0.42 eV for CoPc-CO2 (Fig. 3c). Note that in the cases of CoPc-SO2 and CoPc-SO3 (Fig. S18), the interaction energies of the molecule-graphene interface significantly increased to 2.10 eV and 2.88 eV, suggesting that the formation of CoPc-SO2 and CoPc-SO3 is relatively difficult.

a Charge analysis of CoPc onto graphene with different linkages. b PDOS analysis for d orbitals of Co sites. c Interaction energy of CoPc-SO, CoPc-SO2, CoPc-SO3 and CoPc-CO2. d Free energy diagrams of dechlorination on free-standing CoPc, CoPc-SO, CoPc-SO2, CoPc-SO3 and CoPc-CO2. e Correlations between the Bader charges on Co sites and the Gibbs free energy of dechlorination elemental steps. Source data is provided as a Source Data file.

Toward the EDR pathway, it involves multiple elemental steps of dechlorination and protonation to generate *CH2Cl and *CH3 intermediates (Figs. 3d and S19–S21). The cleavage of the C–Cl bond is identified as a potential-limiting step. For the dechlorination of either CH2Cl2 or CH3Cl, the energy barriers on CoPc-SO are significantly lower than those on CoPc-CO2, as well as those on the free-standing CoPc by reducing 0.5–0.7 eV. For CoPc-SO2 and CoPc-SO3, the dechlorination processes are even more difficult than the free-standing CoPc and CoPc-CO2. Accordingly, among those various models, the electron donation ability of linkages exhibits a negative correlation with the Gibbs free energy of the elemental dechlorination steps (Fig. 3e). These results are highly consistent with the experimental results and demonstrate that the linkage of sulfoxides resulted in electron donation to the Co sites, which facilitates C-Cl bond cleavage and thus enhances the EDR performance. In addition, we presented the complete Gibbs free energy changes for the pathways of EDR into CH4, C2H4 and C2H6 products based on the proposed active CoPc-SO configuration (Figs. S22, S24, S25). For C2 products, the DFT calculations revealed that the involved C-C coupling elemental steps followed the Eley-Rideal mechanism, where surface-bound intermediates (*CH2Cl or *CH3) reacted with solvated CH2Cl2 molecules (Fig. S23)53,54. In all cases, CoPc-SO exhibited consistently lower energy barriers than both pristine CoPc and CoPc-CO2 samples, underscoring the pivotal role of the sulfoxide axial coordination in facilitating the EDR processes.

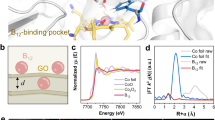

In the DFT calculations, it is found that both CH2Cl2 and CH3Cl cannot directly chemisorb onto CoPc, as the distance between Co (CoPc) and C (CH2Cl2/CH3Cl) sites is more than 3.6 Å. The onset potential of EDR on CoPc-SG approaches −0.28 V. Prior to this catalytic potential, the Co2+/1+Pc redox was observed (Fig. S26). Thus, CoPc should electrochemically evolve by generating Co1+ sites to commence EDR55,56. To validate such an assumption, an in situ Raman spectroscopic measurement was conducted in an electrochemical cell set with a transparent quartz window. CoPc-SG exhibited distinct peaks at 1145 and 754 cm−1 at OCP, corresponding to the A1g (Co-N and C-H vibrations) and B1g (in-plane ring symmetric Co-N pyrrole stretch) modes of CoPc, respectively (Fig. 4a). As the potential passed across the CoPc redox range, the A1g and B1g modes gradually shifted to 1125 cm−1 and 746 cm−1, respectively, signifying the Co2+ to Co1+ reduction prior to the EDR events (Fig. 4b, c). However, the redox of CoPc contains two different pathways that have either H+ coupling or H+ non-coupling character to generate different structures57. We then examined the pH dependence of Co2+/1+ redox in a broad pH range in various PBS buffers, and established the Pourbaix diagram (Fig. S27). The Pourbaix slope of Co2+/1Pc-SG redox is only −4.3 mV pH−1, indicating that the redox event is barely coupled with H+ transfer. The Co2+ to Co1+ reduction should generate [Co1+Pc]⁻ species instead of the possible [Co1+PcH] species as previously reported57, which commenced EDR and the competent HER events (Fig. 4d, e). As the DFT calculation showed an intermediate state in which the *CH2Cl species bonded with CoPc, it indicated that the [Co1+Pc]⁻ sites should bond to CH2Cl2, and the additional electrons transferred to the bonded CH2Cl2 for commencing the dechlorination elemental step (Fig. 4f, g).

a In situ Raman spectra of CoPc-SG in 0.1 M K2HPO4 under Ar atmosphere ranging from OCP to −0.28 V. Raman peak intensity ratio of A1g (b) and B1g (c) mode. Pourbaix diagrams of Co2+/1+ Pc redox in CoPc-SG compared with HER (d) and EDR (e). A schematic diagram presents the electrochemical evolution of CoPc (f) and the corresponding electron transfer between Co sites and CH2Cl2 (g). Source data is provided as a Source Data file.

Besides, the Pourbaix slope of HER on CoPc-SG was fitted to be −58.1 mV pH−1 for the typical one H+ and one electron coupled transfer process (Fig. S28). Upon the EDR event involving into HER, the Pourbaix slope significantly turned to be a positive value of +21.6 mV pH−1, which approaches the Co2+/1+Pc redox potential with increasing pH. Such a phenomenon is observed in our previous result, indicating that the alkaline environment could facilitate the chemisorption of CH2Cl2 on the [Co1+Pc]− sites. In the case of CoPc-OG, it follows the same evolution process of CoPc (Figs. S29, S30). While the Laviron analysis showed that the redox kinetics of Co2+/1+Pc in CoPc-SG is more rapid than that in CoPc-OG (Fig. S31)58, suggesting the tuned electron communication between CoPc and carbon supports by the S-based linkages, and should reflect the above DFT calculation results.

Electrochemical membrane performance

For the scale up application, CoPc-SG was integrated into a self-made electrofiltration module setup to assess its performance in treating the CH2Cl2-contaminated wastewater in a flow-through operation mode (Fig. 5a). The module comprises a feed chamber with a commercial RuO2-IrO2/Ti mesh anode (top), and a permeate chamber featuring a CoPc-SG coated carbon paper (CP) supported by a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane as the cathode (CoPc-SG@CP, bottom). The feeding solution is 0.1 M K2HPO4 with 3 mM CH2Cl2. The as-derived CoPc-SG@CP exhibited a lower water permeability of 100.5 L m−2 h−1 compared to 135 L m−2 h−1 of the pristine CP, which allowed extended residence time for dealing with water purification (Fig. S32). In one single-pass filtration (details in SI), 98% of total CH2Cl2 was removed at a constant current density of 75 mA cm−2 for 300 mL 3 mM CH2Cl2 solution (Figs. 5b–d and S33), including 32.7% of CH2Cl2 converted into CH4, 1.64% of CH2Cl2 converted into C2 products, 63% of CH2Cl2 converted into the incompletely dechlorinated byproduct of CH3Cl and some CH2Cl2 might be physically adsorbed (under the same condition, we indeed detected that the CP electrode without the loading CoPc-SG removed 59% of CH2Cl2 without generating CH4, C2 products and CH3Cl). In addition, the process remained highly energy-efficient, achieving a relatively low electrical energy consumption per order (EEO) of 0.062 kWh m−3 under 75 mA cm−2 (Fig. 5e), which is substantially lower than the EEO value of 0.42 kWh m−3 reported in an analogous cross-flow system treating another typical chlorinated organic compound of 1,2-dichloroethane14. The performance degradation at 100 mA cm−2 could be ascribed to the overly limited mass transport of CH2Cl2 reactant by increasing the applied currents. To provide a more complete picture of the system’s performance, we also calculated the FE for these products (Fig. S34). The concentrations of released Cl− ions showed a consistent variation trend (Fig. S35). Particularly, the vertical flow mode is more effective for enriching and treating trace or low concentrations of CH2Cl2 compared to the traditional lateral flow mode (Fig. S36). To assess the durability of the device, the flow-through electrofiltration was continuously operated for 10 cycles, which maintained the high PRs of CH4 and C2 production, and Cl− ions release (Figs. 5f and S37).

a Scheme of an electrofiltration module setup. b Residual concentrations and removal efficiency of CH2Cl2 in one single-pass filtration at different current densities. c Single-pass conversion efficiency of CH4 production on CoPc-SG@CP in vertical and lateral flow cells. The error bars represent standard deviations from two independent measurements. d Single-pass conversion efficiency of C2 production on CoPc-SG@CP in vertical and lateral flow cells. e EEO in one single-pass filtration at different current densities. f Stability of EDR on CoPc-SG@CP at 75 mA cm−2. Source data is provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

In summary, this work demonstrated that CoPc-SG is an efficient electrocatalyst for the CH2Cl2 dechlorination, achieving PRs of CH4 and C2 products up to 53.9 mmol g−1 h−1 and 10.08 mmol g−1 h−1, respectively. Such performance was significantly enhanced compared to its counterpart CoPc-OG and free-standing CoPc, which represents a high level of EDR of CH2Cl2. It revealed that sulfoxide groups emerged in SG linked to Co site through the axial coordination. An electron donation effect occurred from sulfoxides to Co sites that facilitated the C-Cl bond cleavage. In a further pathway investigation, CoPc on SG surface was reduced without H+ coupling to generate a [Co1+Pc]⁻ specie, which mediated the electron transfer from Co sites to CH2Cl2. For the potential practical application, the electrochemical dechlorination of CH2Cl2 was demonstrated in an electrofiltration module with a lateral flow setup for the treatment of diluted CH2Cl2 solution. In one single-pass filtration, 98% of CH2Cl2 was removed with CH4 conversion efficiency of 32.7%. This research highlights the potential of CoPc-SG as an efficient, selective, and sustainable catalyst for environmental applications, particularly in the treatment of CH2Cl2-contaminated water. The findings offer a promising pathway for further developments in electrocatalytic dechlorination technologies aimed at minimizing environmental pollutants while producing valuable chemicals.

Methods

Materials

Dichloromethane (DCM; 99%), N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF; 99.5%), Phthalocyanine (H2Pc; 99.5%), K3PO4 (99%), KH2PO4 (99.7%) and K2HPO4 (99.7%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Co(NO3)2·6H2O (99%), Graphite powder (99%), K2O8S2 (99.5%), P2O5 (99.99%), thioacetamide (98%) were purchased from Macklin Biochemical Technology. The RuO2-IrO2/Ti mesh was purchased from Hangzhou Saiao Technology. Deionized water (18.2 MΩ cm at 25 °C) from a Millipore water purification system was used throughout the experiments. Unless otherwise noted, all the commercial chemicals were used without purification. All solutions in this work were prepared using ultrapure water.

Synthesis of CoPc-SG and CoPc-OG

GO was synthesized based on a modified Hummers’ method. Firstly, 2 g graphite powders, 1 g K2S2O8 and 1.2 g P2O5 were added into 20 mL 98% H2SO4, and were heated at 100 °C for 10 h. The resultant solids were washed with water to neutrality and dried to obtain a pre-oxidized product. Afterwards, the pre-oxidized product was transferred into 50 mL 98% H2SO4 in an ice bath, and 6.5 g of KMnO4 was slowly added. The mixture was heated in an oil bath at 50 °C for 6 h to further react with KMnO4. Finally, 5mL of H2O2 was added under ice bath conditions, and the final product was bright yellow. The final solid was washed with 3.7% HCl and plenty of water, centrifuged and dialyzed for 7 days to obtain GO.

To obtain a sulfur-doped graphene (SG), thioacetamide was used as the dopant, and mixed with GO aqueous solution (1 mg mL−1) (mass ratio 1:50). Then the suspension was transferred into a polytetrafluoroethylene-lined stainless autoclave for heat treatment at 150 °C for 3 h. After the reaction, the resultant solids were washed with water and ethanol to obtain the desired SG. As a control sample, the oxygen-doped graphene (OG) was synthesized from GO following the same hydrothermal conditions without using any dopants.

To obtain heterogeneous cobalt complexes, the as-synthesized SG or OG (4 mg) was dispersed in 20 mL DMF and mixed with 2 mg of cobalt phthalocyanine (CoPc). The resultant dispersion was heated at 80 °C for 12 h, and washed with ethanol to remove excess CoPc. The final solid was dispersed in isopropanol with a concentration of 2 mg mL−1 to obtain the catalyst ink, which was denoted as CoPc-SG and CoPc-OG, respectively.

Electrochemical measurements

All electrochemical measurements were conducted using a CHI 1140 potentiostat in a three-electrode setup at room temperature (25 °C). A gas-tight H-type cell was employed with a cathode chamber (50 mL) and an anode chamber (50 mL) separated by a proton exchange membrane (Nafion-117, 183 μm in thickness). Prior to use, the Nafion-117 membrane was pretreated by sequential 80 °C boiling steps in 5 wt% H2O2, deionized water, 1.0 M H2SO4. All potentials were measured against a Hg/HgO electrode, unless indicated otherwise. A graphite electrode was used as the counter electrode. The supporting electrolyte was 0.1 M K2HPO4 solutions (pH = 8.8 ± 0.1, stored in a sealed container at 25 °C). (CPs, 1 × 1 cm2) With casting, 140 μL catalyst inks were used as the working electrodes, the covered area was 2 cm2, giving a catalyst mass loading of 0.14 mg cm−2.

For the electrocatalysis of EDR, Ar was flown at 20 ccm through a pure CH2Cl2 liquid to carry CH2Cl2 vapor into the cathode chamber for at least 30 min to obtain a CH2Cl2 aqueous solution before each electrolysis. All the electrochemical CH2Cl2 dechlorination measurements were conducted with stirring at 300 rpm. The Ar carried the CH2Cl2 vapor was kept bubbling into the electrolyte during the electrolysis. Gaseous products from the cathodic chamber were analyzed in real-time by in-line (GC, Agilent Technologies 8890) equipped with Hayesep D/N and Molsieve 5A columns, a thermal conductivity detector (for H2 detection) and a flame ionization detector (for hydrocarbons detection). All the reported current density was normalized to the geometric area of CP without iR compensation. All recorded potentials (E) were converted to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) scale with the Eq. (1),

The Faradaic efficiency for products was calculated using the Eq. (2),

where n is the number of electron transfer, M is the relative molecular mass, F is the Faraday constant, Q is the quantity of applied electricity.

Turnover frequency and production rate analysis

Turnover frequency (TOF) was calculated based on Eq. (3),

where J is the cathodic current density, A is the geometric surface area of the electrode, F is Faraday’s constant, and M is the molar amount of Co sites on the surface of the electrode. The molar amount of Co sites was quantified by ICP-OES. In brief, the electrodes coated with catalysts were immersed in 0.5 mL HNO3 (65%) for 3 min, and the resultant acidic solutions containing Co2+ ions were diluted to 5 mL, and then were tested by ICP-OES. The PR was calculated as the molar amounts of CH4 or C2 produced per gram of catalyst per hour.

In situ attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectra

In situ ATR-FTIR spectra were performed on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Nicolet iS50 FTIR spectrometer, equipped with a diamond crystal and a DLaTGS detector cooled with liquid nitrogen. A customized three-electrode electrochemical single-cell was used for tests. Graphite rod and Hg/HgO electrodes were used as counter and reference electrodes, respectively. Silicon prisms coated with catalysts were applied as the working electrodes. For ATR-FTIR measurement, 64 scans were collected with a spectral resolution of 1 cm−1. The potential-dependent spectra were collected by applying the working potential from 0.28 to 0.78 V vs. RHE in 0.1 M K2HPO4 with steps and durations of 0.1 V and 120 s, respectively.

In situ Raman spectra

In situ Raman measurements were conducted on an electrochemical cell quartz window in 0.1 M K2HPO4. An Ag/AgCl wire (soaked in saturated KCl) and a carbon rod were used as the reference and counter electrode, respectively. Glassy carbon electrodes coated with catalysts were used as the working electrodes. Raman spectral window was set as 200–1200 cm−1, and the acquisition time was set as 90 s with a 638 nm laser.

Electrochemical membrane

The filtration module consists of upper and lower chambers with gas collection and inlet and outlet ports, a CoPc-SG@CP/PVDF/Ti mesh and a commercial RuO2-IrO2/Ti mesh was applied as the cathode and anode, respectively, and were connected with a DC power supply (UNI-T, UTP136S). The size of the CP coated with the catalyst was 32 cm−2. Typically, in one single-pass filtration, the feeding solution of 3 mM CH2Cl2 dissolved in 300 mL 0.1 M K2HPO4 was circulated utilizing a constant-current pump (Rongbai, BT100-2J) under a constant current density of 25/50/75/100 mA cm−2. After 1 h of operation, any gaseous products generated from EDR in the upper chamber were collected through a gas collection port, and the anodic gas was collected in the lower chamber. The collected gases were quantitatively analyzed by gas chromatography, the Cl- ions released into the solutions were measured by IC, and the amounts of residual CH2Cl2 were measured by 1H NMR.

Computational details

Spin-polarized DFT calculations were performed by the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP) with the projector augmented method to describe the interaction between atomic cores and valence electrons59,60,61. The exchange-correlation functional is treated with the generalized gradient approximation in the form of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof 62 CoPc, CoPc-OG, and CoPc-SG slab models were employed to simulate the surface properties. The vacuum layer was set around 15 Å in the z-direction to avoid interaction between neighboring images. The Van der Waals interaction is considered using the DFT-D3 method. An energy cutoff for the plane wave basis expansion was set to 480eV, and the force on each atom less than 0.03eV/Å was set as the convergence criterion for geometry relaxation. The k-points in the Brillouin zone were sampled by a 1 × 1 × 1 grid63. The electronic energy was considered self-consistent with the energy change less than 10–5 eV. VASPsol was used to simulate the solvent effect in the experimental environment64.

The energy differences (ΔE) for the reactions were calculated according to the approach proposed by Nørskov and coworkers, ΔE = ΔE0 + ΔEU, where ΔE0 is the computed reaction energy, ΔEU is the externally applied potential. In the dechlorination process, ΔEU = −e(U−UClθ), where UClθ is the standard potential of the reversible chlorine electrode, UClθ = 1.36 V at 298 K. In the hydrogenation process, ΔEU = −eUH, where UH is the electrode potential relative to the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE), UH = 0 V at 298 K.

Electrical energy consumption

Electrical energy consumption per order (EEO, kWh m−3 order−1) for CH2Cl2 reduction during electrofiltration was evaluated using the Eq. (4),

where Ucell (V) is the applied voltage, I (A) is the current, Q is the permeate flow rate, C0 and C are the initial and timely measured contaminant concentrations, respectively.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the conclusions of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Additional data are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Hossaini, R. et al. The increasing threat to stratospheric ozone from dichloromethane. Nat. Commun. 8, 15962 (2017).

Cox, M. L. et al. Regional sources of methyl chloride, chloroform and dichloromethane identified from AGAGE observations at Cape Grim, Tasmania, 1998-2000. J. Atmos. Chem. 45, 79–99 (2003).

Simmonds, P. G. et al. Global trends, seasonal cycles, and European emissions of dichloromethane, trichloroethene, and tetrachloroethene from the AGAGE observations at Mace Head, Ireland, and Cape Grim, Tasmania. J. Geophys. Res. 111, D18304 (2006).

Agency for toxic substances and disease registry. Toxicol. Profile Methylene Chloride https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp14.pdf (2000).

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Risk Evaluation for Methylene Chloride, https://www.epa.gov/assessing-and-managing-chemicals-under-tsca/risk-evaluation-methylene-chloride-0 (2017).

Jiang, W. et al. Synergistic elimination of NOx and chloroaromatics on a commercial V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalyst: byproduct analyses and the SO2 effect. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 12657–12667 (2019).

Zhang, L., Deng, W., Cai, Y., Dai, Q. & Guo, L. Comparative studies of phosphate-modified CeO2 and Al2O3 for mechanistic understanding of dichloromethane oxidation and chloromethane formation. ACS Catal. 10, 13109–13124 (2020).

Xiang, L. et al. Catalytic ozonation of CH2Cl2 over hollow urchin-like MnO2 with regulation of active oxygen by catalyst modification and ozone promotion. J. Hazard. Mater. 436, 129217 (2022).

Almomani, F., Rene, E. R., Veiga, M. C., Bhosale, R. R. & Kennes, C. Treatment of waste gas contaminated with dichloromethane using photocatalytic oxidation, biodegradation and their combinations. J. Hazard. Mater. 405, 123735 (2021).

An, J. et al. Revealing decay mechanisms of H2O2-based electrochemical advanced oxidation processes after long-term operation for phenol degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 10916–10925 (2020).

Su, Y. et al. Recent advances of chlorinated volatile organic compounds’ oxidation catalyzed by multiple catalysts: reasonable adjustment of acidity and redox properties. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 9854–9871 (2022).

Ding, S., Wu, S., Fang, N., Chu, Y. & Wang, P. Recent advances in chlorinated volatile organic compounds’ oxidation over multiple noble metal catalysts: a review based on rational manipulation of redox-acidity balance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 349, 127859 (2024).

Williams, C. K., McCarver, G. A., Lashgari, A., Vogiatzis, K. D. & Jiang, J. J. Electrocatalytic dechlorination of dichloromethane in water using a heterogenized molecular copper complex. Inorg. Chem. 60, 4915–4923 (2021).

Choi, C. et al. Efficient electrocatalytic valorization of chlorinated organic water pollutants to ethylene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 160–167 (2023).

Gao, Y. et al. Effective electrochemical trichloroethylene removal from water enabled by selective molecular catalysis. Carbon Future 1, 9200015 (2024).

Zuo, K. et al. Electrified water treatment: fundamentals and roles of electrode materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 472–490 (2023).

Alkhadra, M. A. et al. Electrochemical methods for water purification, ion separations, and energy conversion. Chem. Rev. 122, 13547–13635 (2022).

Yu, W., Jiang, H., Fang, J. & Song, S. Designing an electron-deficient Pd/NiCo2O4 bifunctional electrocatalyst with an enhanced hydrodechlorination activity to reduce the consumption of Pd. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 10087–10096 (2021).

Cheon, S. et al. Neighboring catalytic sites are essential for electrochemical dechlorination of 2-chlorophenol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 25151–25157 (2024).

Wu, Y., Liang, Y. & Wang, H. Heterogeneous molecular catalysts of metal phthalocyanines for electrochemical CO2 reduction reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 3149–3159 (2021).

Sorokin, A. B. Phthalocyanine metal complexes in catalysis. Chem. Rev. 113, 8152–8191 (2013).

Yang, Z.-W., Chen, J.-M., Qiu, L.-Q., Xie, W.-J. & He, L.-N. Molecular engineering of metal complexes for electrocatalytic carbon dioxide reduction: from adjustment of intrinsic activity to molecular immobilization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202205301 (2022).

Chen, K. et al. Iron phthalocyanine with coordination-induced electronic localization to boost oxygen reduction reaction. Nat. Commun. 11, 4173 (2020).

Rivera Cruz, K. E., Liu, Y., Soucy, T. L., Zimmerman, P. M. & McCrory, C. C. L. Increasing the CO2 reduction activity of cobalt phthalocyanine by modulating the σ-donor strength of axially coordinating ligands. ACS Catal. 11, 13203–13216 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Linkage effect in the heterogenization of cobalt complexes by doped graphene for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13532–13539 (2019).

Hossain, M. D., Huang, Y., Yu, T. H., Goddard Iii, W. A. & Luo, Z. Reaction mechanism and kinetics for CO2 reduction on nickel single atom catalysts from quantum mechanics. Nat. Commun. 11, 2256 (2020).

Varela, A. S. et al. Electrochemical reduction of CO2 on metal-nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts. ACS Catal. 9, 7270–7284 (2019).

Chang, Q. et al. Metal-coordinated phthalocyanines as platform molecules for understanding isolated metal sites in the electrochemical reduction of CO2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 16131–16138 (2022).

Choi, C. et al. CO2-promoted electrocatalytic reduction of chlorinated hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 8486–8491 (2024).

Romero, K. J., Galliher, M. S. & Pratt, D. A. Radicals in natural product synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 7851–7866 (2018).

Michael B. Smith, J. M. In March’s Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure 6th edn, 234–295 (Wiley-Interscience, 2006).

Hummers, W. S. J. & Offeman, R. E. Preparation of graphitic oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80, 1339–1339 (1958).

Xu, W. et al. Graphene-veiled gold substrate for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Adv. Mater. 25, 928–933 (2013).

Gu, H. et al. Graphdiyne/graphene heterostructure: a universal 2D scaffold anchoring monodispersed transition-metal phthalocyanines for selective and durable CO2 electroreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 8679–8688 (2021).

Zhang, S. et al. Raman spectra and corresponding strain effects in graphyne and graphdiyne. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 10605–10613 (2016).

Yang, Z. et al. Sulfur-doped graphene as an efficient metal-free cathode catalyst for oxygen reduction. ACS Nano 6, 205–211 (2012).

Xia, L. et al. Sulfur-doped graphene for efficient electrocatalytic N2-to-NH3 fixation. Chem. Commun. 55, 3371–3374 (2019).

Jeon, I.-Y. et al. Edge-selectively sulfurized graphene nanoplatelets as efficient metal-free electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction: the electron spin effect. Adv. Mater. 25, 6138–6145 (2013).

Li, N. et al. Bioinspired catalytic generation of high-valent cobalt-oxo species by the axially coordinated CoPc on pyridine-functionalized MWCNTs for the elimination of organic contaminants. Appl. Surf. Sci. 434, 1112–1121 (2018).

Song, J. et al. Asymmetrically coordinated CoB1N3 moieties for selective generation of high-valence Co-Oxo species via coupled electron-proton transfer in Fenton-like reactions. Adv. Mater. 35, 2209552 (2023).

Pan, Y. et al. Design of Single-Atom Co–N5 Catalytic Site: a robust electrocatalyst for CO2 reduction with nearly 100% CO selectivity and remarkable stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4218–4221 (2018).

Li, A.-Z. et al. One-step electrochemical ethylene-to-ethylene glycol conversion over a multitasking molecular catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 5622–5633 (2024).

Wallington, T. J. et al. CH3Cl, CH2Cl2, CHCl3, and CCl4: infrared spectra, radiative efficiencies, and global warming potentials. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 174, 56–64 (2016).

Gan, G. et al. Identification of catalytic active sites in nitrogen-doped carbon for electrocatalytic dechlorination of 1, 2-dichloroethane. ACS Catal. 9, 10931–10939 (2019).

Li, H. et al. Constructing asymmetric dual active sites through bimetallic synergy for achieving selective photocatalytic nonoxidative coupling of methane toward ethylene. ACS Catal. 15, 9717–9727 (2025).

Jiang, J. et al. Methyl radical dominated highly selective methane oxidation to liquid oxygenates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 36016–36026 (2025).

Zhang, X. et al. Anion intercalation enables efficient and stable carboxylate upgrading via aqueous non-Kolbe electrolysis. Nat. Commun. 16, 3719 (2025).

Chen, L. et al. Accurate identification of radicals by in situ electron paramagnetic resonance in ultraviolet-based homogeneous advanced oxidation processes. Water Res. 221, 118747 (2022).

Duan, J., Yang, Y., Fan, S., Li, X. & Liu, S. Vitamin B12-functionalized NiMn2O4 spinel: a promising bioinspired electrocatalyst for dechlorination in the aqueous phase. J. Phys. Chem. C 129, 9356–9367 (2025).

Yang, J. et al. Highly efficient electrocatalysis dechlorination of dichloromethane over single-atom Cu/Co3O4-β spinel nanofibers. Chem. Eng. J. 470, 144040 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. A water-soluble Cu complex as molecular catalyst for electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction on graphene-based electrodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1803151 (2019).

Wang, J., Huang, X., Xi, S., Xu, H. & Wang, X. Axial modification of cobalt complexes on heterogeneous surface with enhanced electron transfer for carbon dioxide reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 19162–19167 (2020).

Hu, B. et al. Directing the C–N coupling pathway enables efficient urea electrosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 21764–21777 (2025).

Chen, H. et al. Mechanism of electrocatalytic H2 evolution, carbonyl hydrogenation, and carbon–carbon coupling on Cu. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 13949–13961 (2024).

Akyüz, D., Keleş, T., Biyiklioglu, Z. & Koca, A. Metallophthalocyanines bearing polymerizable [5-((1E)-[4-(diethylamino)phenyl]methyleneamino)-1-naphthy1]oxy groups as electrochemical pesticide sensor. Electroanalysis 29, 2913–2924 (2017).

Bıyıklıoğlu, Z., Çakır, V., Demir, F. & Koca, A. New electropolymerizable metal-free and metallophthalocyanines bearing {2-[3-(diethylamino)phenoxy]ethoxy} substituents. Synth. Met. 196, 166–172 (2014).

Liu, Y. & McCrory, C. C. L. Modulating the mechanism of electrocatalytic CO2 reduction by cobalt phthalocyanine through polymer coordination and encapsulation. Nat. Commun. 10, 1683 (2019).

Laviron, E. The use of linear potential sweep voltammetry and of a.c. Voltammetry for the study of the surface electrochemical reaction of strongly adsorbed systems and of redox-modified electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 100, 263–270 (1979).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 3, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 169–196 (1996).

Kresse, G. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Mathew, K., Sundararaman, R., Letchworth-Weaver, K., Arias, T. A. & Hennig, R. G. Implicit solvation model for density-functional study of nanocrystal surfaces and reaction pathways. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 084106 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from the Key Basic Research Program of Jiangsu, China (BK20253055), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22002119, 22106139), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LZYQ25B060001), and the Programs of Science and Technology of Suzhou, China (ZXL2021448, SYG202137).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. conceived and designed the project. Y.Y. and Y.H. prepared the samples. Y.Y. conducted the electrocatalytic dechlorination. Y.W. conducted the flow-through dechlorination. M.P. carried out the DFT calculations. Y.Y., M.P., G.Gao, and J.W. wrote the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Haohong Duan and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

You, Y., Wei, Y., Hu, Y. et al. Electrochemical dechlorination and hydrocarbon valorization by cobalt phthalocyanine with non-proton-coupled redox property. Nat Commun 17, 985 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67720-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67720-6