Abstract

Programmable dual-mode (two- or three- dimension, 2D/3D)-coupling responsive coating constitutes one of the most promising strategies to ensure the security of anti-counterfeiting and information encryption, but it is still lack of effective approaches to integrate stimuli-responsive 2D and 3D information. Herein, we develop a self-growing method to achieve this purpose based on photoswitchable fluorescence and supramolecular interaction (dipole-dipole interaction) toward advanced multi-dimensional anti-counterfeiting and encryption. In our method, trifluoromethyl-rich monomers (2,2,2-trifluoroethyl methacrylate (TFEMA) and 2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl acrylate (HFBA)), polymerizable green fluorescent dye (2-(6-(dimethylamino)−1,3-dioxo- 1H-benzodeisoquinolin-2(3H)-yl) ethyl acrylate, MNEA) and photochromic diarylethene derivative (4-(acryloyloxy) butyl-4-(2-methyl-3-(2-(2-methylbenzo thiophen-3-yl)−4-oxo-5,6-dihydro-4H-thieno 2,3- thiopyran-3-yl) benzo thiophen-6-yl)−4-oxobutanoate, BTBA) are introduced into specific 3D structure via a self-growing method. The coating is capable of reversible fluorescence switching from green to red through photo-induced fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) process between MNEA and BTBA, and reversible switch of 3D structure based on force- and thermo-induced shape memory caused by dipole-dipole interaction and covalent bond. Interestingly, when the 2D information is stimulated, the 3D information remains unchanged. Several examples demonstrate that the great application potential of the programmable responsive coating in high-security of multilevel anti-counterfeiting and information encryption. We thus envision the great potential of our method in developing advanced anti-counterfeiting, multilevel information encryption and high-density data storage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Counterfeiting is a serious global social problem involving many industries, which can cost the worldwide economy over 500 billion annually1. Many counterfeiting technologies were developed to ensure economic security and prevent the serious social problems caused by counterfeit information2,3,4,5,6. These technologies generally included the complanate two-dimensional information (2D, Fig. 1a), and surface texture (3D, Fig. 1a). 2D technologies mainly depended on fluorescent and color coating based on optical pattern, watermark, QR code, bar code, and so on7,8,9,10,11. Recently, many stimulus-responsive coatings that can regulate their optical signal (i.e., fluorescence, color) through external stimuli (i.e., light, temperature, force, ions, pH and humidity) have been developed for improving the security of these anti-counterfeiting technologies12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Among these, photoswitchable fluorescence coatings with high resolution and easy identification, which can achieve reversible fluorescence switching under the alternately irradiation of different light, have been applied in creating various advanced anti-counterfeiting systems26,27,28,29. Meanwhile, 3D-encoding strategy like surface texture is another powerful method by using reflecting light to show real 3D image (holography) or utilizing surface texture to encode information directly (Fig. 1a)30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. 3D-encoding strategies thus have gained widespread attention because of some excellent features, including tunable properties, 3D topography, and hard-to-forge, and thus applied in the development of anti-counterfeiting systems38,39. Although reported 2D- and 3D-encoding strategies exhibit some inherent advantages, and applied to banknotes, passport and high-end packaging, they can only offer single-dimensional anti-counterfeiting and encryption protection, which put them at risk of being forged because of single functionality and low information-bearing dimension40,41,42. Therefore, the imperfection of 2D- or 3D-encoding strategy has encouraged researchers to try to couple them into one system to significantly improve security performance.

a Anti-counterfeiting illustration of hand-drawn commemorative currency based fluorescence patterns (2D) and 3D structures. b Schematic diagram of the coupling of the 3D structure and color (2D) of a gecko. c Self-growth diagram of 2D/3D-coupling responsive coating and the corresponding structures of fluorescence dye, photo-induced reversible transformation of photochromic molecules and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) process (UV: 365 nm; Visible light (Vis.): 525 nm), polymer, crosslinker, dynamic interaction, reversible fluorescence switching and three-dimensional (3D) structure switching. Fluorescence switching depended on the photo-induced FRET process between fluorescence dyes and photochromic molecules. 3D structures switching depended on the thermo- and force-induced dynamic interaction to trigger the shape memory.

Natural systems are masters in coupling 2D color and 3D structures for camouflage. Like Tokay geckos43, they can achieve desired camouflage by specifically integrating 2D color and 3D structure on their backs (Fig. 1b), in which the 2D and 3D information are on-demand combined to significantly enhance their security, suggesting an advanced anti-counterfeiting technology. Recently, several attempts have been conducted to mimic such a combination of 2D and 3D technologies to develop high-performance anti-counterfeiting and encryption systems44,45,46,47. However, those 2D and 3D information are simply mixed rather than being coupled on demand. They are still far from on-demand coupling that allow for independent manipulation of 2D and 3D information, due to the lack of the effective integration mechanism of incorporating functionalized molecules to functionalize 3D structures. Obviously, programmatically coupling responsive 2D and 3D information like natural systems still remains challenging. In contrast, bio-inspired self-growing method is a promising strategy for constructing programmable 3D structures and on-demand coupling responsive 2D and 3D information48,49,50. In this strategy, polymerizable functional monomers (nutrients) are firstly pre-stored in substrates (act as seeds), and then generated on-demand 3D structures by using photo-induced cascade reactions including polymerization for forming polymer networks and chain exchange reactions to eliminate internal stress caused by growth between 3D structures and substrates51. Compared with the traditional methods (i.e., imprinting methods), bio-inspired self-growing method also shows several advantages: (1) easily coupling different functional monomers into the user-defined location to creating specific structures with orthogonal multi-stimulus response; (2) post-modifying some functions that cannot be introduced by direct synthesis or imprinting methods.

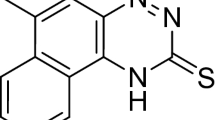

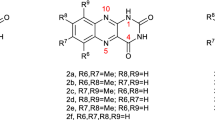

Herein, we use a self-growing method to prepare programmable 2D/3D-coupling responsive coatings constructed via dynamic interaction (dipole-dipole interaction), toward multi-dimensional anti-counterfeiting and information encryption. In our design, the initiated substrates (seeds) are prepared via free radical polymerization of trifluoromethyl-rich monomers (2,2,2-trifluoroethyl methacrylate (TFEMA) and 2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl acrylate (HFBA)), and a cross-linker (hexamethylene diacrylate, HDDA). Polymerizable green fluorescent dye (2-(6-(dimethylamino)−1,3-dioxo- 1H-benzodeisoquinolin-2(3H)-yl) ethyl acrylate, MNEA) and photochromic diarylethene derivative (4-(acryloyloxy) butyl-4-(2-methyl-3-(2-(2-methylbenzo thiophen-3-yl)−4-oxo-5,6-dihydro-4H-thieno 2,3- thiopyran-3-yl) benzo thiophen-6-yl)−4-oxobutanoate, BTBA) are integrated into the seeds to fabricate 2D/3D-coupling responsive coating by using a self-growing method and subsequently benzenesulfonic acid (BSA)-induced transesterification for chain exchange. In this system, photo-induced fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) process between MNEA and BTBA would ensure fluorescence information (2D) to reversibly switching between green and red52. Thermo- and force-induced reversible change of dipole-dipole interaction would induce a reversible switching in 3D information. Overall, comparing with previous stimuli-responsive coating for anti-counterfeiting, programmable 2D/3D-coupling responsive coating shows multiple advantages: (1) the responsive 2D and 3D information are programmatically coupled into the user-defined location; (2) the coupled responsive 2D and 3D information can be reversibly and independently switched; (3) growth-induced self-healing can facilitate the preparation of complex user-defined structures for their applications in advanced anti-counterfeiting and information encryption. Thanks to advanced features including high fluorescence contrast, responsiveness, and excellent reversibility, we thus can demonstrate the programmable responsive coating in high-security of multilevel anti-counterfeiting and information encryption. These results indicate that this strategy offer an opportunity for developing multi-mode anti-counterfeiting and encryption materials.

Results

Anti-counterfeiting coating design

Our dual-modal (2D/3D) encryption strategy was demonstrated through combining the self-growing method and dynamic interaction (dipole-dipole interaction) to prepare programmable 2D/3D-coupling responsive coatings (Fig. 1c). The self-growing method, capable of in-situ post-modulating the structure and properties of existed samples or on-demand integrating functional monomers into prepared samples, represents a desired method for developing orthogonal multi-stimulus response functional materials or functionalized surface. This method would urge us to specifically integrate functional monomers into prepared samples for developing functionalized surface with orthogonal multi-stimulus response (Fig. 1c). In addition, dipole-dipole interactions were typical dynamic interactions, which can facilitate the assembly and disassembly of polymer-network structures by employing heat and force as stimuli (Fig. 1c). Therefore, a thermo- and force-induced reversible 3D structural switching would be created using self-growing method to specifically integrate dipole-dipole interactions into 3D structure. Next, the thermally stable green fluorescence dye and photochromic dyes were incorporated into the pre-programmed 3D structure using a self-growing method. A typical photo-induced fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) process occurred, resulting in the photo-induced reversible fluorescence switching between green and red (Fig. 1c). During growth-induced size expansion, mechanical tension was caused in the polymer networks, which hindered the structural growth. Transesterification-based chain exchange step was thus designed to eliminate such tension to ensure stable 3D structures (Fig. 2a). Finally, a photo-, thermo-, and force-induced dual-modal (2D/3D) switching systems were created (Fig. 1c). They were supposed to exhibit some favorable features, including excellent photo- and thermo-responsiveness and reversibility, high fluorescence contrast, and self-healing properties.

a Schematic illustration of preparation of anti-counterfeiting coating based on self-growing method and transesterification. b Schematic growing strategy. c Schematic illustration of the corresponding structures of TFEMA, HFBA, and HDDA, and polymer (PTFEMA-co-PHFBA) and crosslinker. d Photographs of cross-section of the grown structure over time. The scale bar is 0.2 cm. e Height changes of growing 3D structure under the different polymerization time. f 3D profiles of the grown 2D structures. Inset in (f): the 3D profile of the grown structures.

Time- and space-controlled growth of 3D structures

The starting coatings (seeds) were prepared via a copolymerization of trifluoromethyl-rich monomers (2,2,2-trifluoroethyl methacrylate (TFEMA, monomer) and 2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl acrylate (HFBA, comonomer) and hexamethylene diacrylate (HDDA, crosslinkers) in the presence of a photoinitiator (I819, Fig. 2a, b, c and Supplementary Fig. 1). The seed is named as P0 (Supplementary Table 1, nTFEMA/nHFBA = 1/1). Next, the nutrients made from trifluoromethyl-rich TFEMA and HFBA (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 2.5/1), and crosslinker (HDDA) were employed to swell seeds within 4 h (Fig. 2a, b, c and Supplementary Figs. 2, 3). To prevent sample damage caused by excessive swelling, we chose 1.5 h as the swelling time. The swollen samples were sealed and stored in the dark for 1 d to ensure that the nutrients were evenly distributed in seeds. The stable samples were exposed to blue light (460 nm, 10 mW/cm2) to grow 3D structure under a mask with a circular hole (d = 2 mm). As shown in Fig. 2d, the 3D structure gradually grown on the surface of seeds within 460 s, accompanying with a significant linear increase in the height of a circular pillar (h = 286 μm, Fig. 2d, e, f and Supplementary Fig. 4). Finally, anti-counterfeiting coating was successfully fabricated based on BSA-induced transesterification. BSA-induced transesterification can eliminate growth stress to ensure the stability of coating (Supplementary Fig. 5)50. In addition, atomic force microscopy (AFM) was used to capture microscopic variations in surface morphology (5 × 5 μm). The surface of the seed and grown 3D structure appears to be relatively smooth (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). These results proved that the growth process of 3D structures is time-controllable.

Space-controlled growth of 3D structures was also investigated. Essential to this synthesis, 2-(6-(dimethylamino)−1,3-dioxo-1H-benzodeisoquinolin-2(3H)-yl)ethyl acrylate (MNEA, green fluorescence dye, Supplementary Fig. 7) and 4-(acryloyloxy)butyl-4-(2-methyl-3-(2-(2-methylbenzothiophen-3-yl)−4-oxo-5,6-dihydro-4H-thieno-2,3-thiopyran-3-yl)benzothiophen-6-yl)−4-oxobutanoate (BTBA, photochromic dyes, Supplementary Fig. 8) were first synthesized based on our previous work28,53. MNEA exhibited a stable green fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. 9). BTBA revealed reversible fluorescence switching between none and red fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. 10). Subsequently, we fabricated the seeds containing MNEA or BTBA using one-pot photo-induced radical copolymerization. Seeds containing MNEA exhibited an absorption peak (375 nm, Supplementary Fig. 11a) and a green fluorescence emission peak (506 nm, Supplementary Fig. 11b). Seeds containing BTBA showed a reversible switching in absorbance and fluorescence emission under alternating UV and Vis. irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 11c, d). When we used the nutrients including TFEMA, HFBA, MNEA, BTBA, and HDDA to grow 3D structures (typical pillar shape, the grown coatings were named as P1-P12, Supplementary Table 1), grown structures (P1, nTFEMA/nHFBA = 2.5/1) exhibited the absorption peak of MNEA and the reversible absorption peak of BTBA under alternating UV and Vis. irradiation, whereas no absorption peak was observed in the non-growing areas (Fig. 3a, b, c). Especially, UV could induce a color change form pale yellow to pink in grown structures containing MNEA and BTBA (Fig. 3b). We also tested the fluorescent cross-section images of the grown structure made from 460 s. As shown in Fig. 3d, the growth area showed obvious green fluorescence, and the fluorescence intensity was highest at the top surfaces (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). More complex 3D patterns could be constructed by employing complex masks (Fig. 3f). These results demonstrated that spatial-controlled growth was feasible. The time- and space-controlled growth would prompt us to create an advanced anti-counterfeiting and encryption system via on-demand coupling 2D and 3D information.

Schematic illustration (a) and photographs (b) of anti-counterfeiting coating (P1) under UV (365 nm, 2.8 mW/cm2, 10 min) and Vis. (525 nm, 1.34 mW/cm2, 12 min). The scale bar is 0.4 cm. c The absorption of growing (1) and non-growing areas (2 (Vis., 12 min) and 3 (UV, 10 min)). d Fluorescent cross-section images of the grown structure (Grown time: 460 s). The scale bar is 1 mm. e Fluorescence intensity of the different regions was obtained using ImageJ software. f 3D profiles of the grown sample (P8). Inset in (f): optical photographs of grown sample. The scale bar is 0.5 cm.

Coupling responsive 2D and 3D information

The above results demonstrated the effectiveness of the time- and space-controlled growth of this growth strategy. Based on this, the common monomers (i.e., 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate) were used to grow 3D structure (3D information, Fig. 4a). Growing 3D structure could return to its initial state after being pressed at 60 °C and then fixed at 25 °C, indicated that growing 3D information had no responsiveness to heat and force (Fig. 4a, b). When we utilized TFEMA and HFBA as functional monomers to construct 3D information (Fig. 4c), the 3D structure exhibited a typical thermally induced shape memory. When we compressed it at high temperature (T = 60 °C) and placed it in a low temperature environment (T = 25 °C), its 3D structure almost disappeared (h = 30 μm, Fig. 4c, d), and then continued to maintain this state at temperature below 40 °C. Subsequently, the 3D structure was recovered in a relatively high-temperature environment (T = 45 °C). This process was reversible (Fig. 4d). This feature should be attributed to be fact that growing 3D structure have a shape-memory transition temperature (Ttrans= 40 °C). Ttrans depended on the glass transition temperature (Tg). Briefly, when a high temperature of 60 °C was used, dipole-dipole interaction showed an excellent dynamic characteristic, and growing 3D structure was elastic (Tg = 40 °C). The compressive stress can be released by dynamic interaction, resulting in the disappearing 3D structure and metastable covalent crosslinking points (Fig. 4c). When the temperature is below Ttrans (T = 25 °C, T < Tg), dipole-dipole interaction exhibited a weak dynamic performance, P1 acted as typical thermoset, which would promote a metastable 3D structure to remain in its current state rather than recover. Subsequently, upon the enhancement of T (T = 45 °C), the metastable covalent crosslinking points would drive 3D structure recovery. Finally, the 3D structure reverted to its original state. Thus 3D structural cycling could be achieved based on thermo- and force-induced shape memory properties caused by dipole-dipole interaction and covalent bond. In addition, we used atomic force microscopy (AFM) to acquire microscopic variations in surface morphology after the stimulation of force (5 × 5 μm). A relatively smooth surface of grown 3D structure was presented (Supplementary Fig. 6b). When 3D structure disappears by the force stimulus, only tiny structures on its surface are observed (Supplementary Fig. 6c). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was also employed to observe the non-growing area (grown 3D structure) and the growing area of the growing sample. The results indicated that growth did not induce nano-scale microstructures (Supplementary Fig. 13).

a Schematic illustration and 3D profiles of thermostable 3D information. The scale bar is 1 mm. b The 2D profile of the grown structures under the alternating stimulation of force and heat. c Schematic illustration and 3D profiles of thermo-induced reversible 3D information switching. The scale bar is 1 mm. d The 2D profile of the grown structures under the alternating stimulation of force and heat. Inset in (d): optical photographs of grown sample (P1) under force and heat. The scale bar is 2 mm. e Schematic illustration and photographs of photo-induced fluorescence switching of P1 under UV (365 nm, 2.8 mW/cm2, 10 min) and Vis. (525 nm, 1.34 mW/cm2, 12 min). The scale bar is 1 cm. f Photo-induced fluorescence switching of P1 under UV and Vis.

Furthermore, we further explored the shape-memory property. The sample could be returned to its initial state from various shapes (twist and bend shapes, Supplementary Fig. 14), and even various embossed patterns can be erased at 45 °C (Supplementary Fig. 15). Our previous works revealed that Tg of the polymer made from TFEMA and HFBA gradually increased as the enhancement of TFEMA fraction54. Therefore, we tried to adjust Ttrans by tuning Tg, which can induce a programmed control of thermo-response 3D information. The different samples (P1 (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 2.5/1), P5 (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 1/1), P6 (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 0.5/1), P7 (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 1.5/1), P8 (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 2/1)) were prepared to explore their Tg and mechanical properties (maximum tensile strain (ε), modulus (E), strength (σ), toughness (T)). The more proportion of TFEMA caused coating to show a higher Tg (Supplementary Fig. 16) and a better mechanical property including high E and σ (Supplementary Fig. 17 and Supplementary Table 2).

Next, the green fluorescence dyes (MNEA) and photochromic molecules (BTBA) were integrated into growing 3D structures (Fig. 4e). The introduction of MNEA and BTBA does not affect the mechanical properties of the 3D structure due to the quite low content of fluorescence dyes and photochromic molecules (MNEA (0.025 ‰mol), BTBA (1.5 ‰mol), Supplementary Fig. 18). The growing 3D structures containing MNEA and BTBA revealed a fluorescence change from green to red (Fig. 4e). The large spectral overlap between the fluorescence emission of MNEA and the absorption of the closed-ring structure of BTBA (BTBA-c) demonstrated that an efficient FRET process could occur (Supplementary Fig. 19). Therefore, we further optimized the FRET efficiency of coating containing the different ratio of MNEA to BTBA (P1 (nMNEA/nBTBA = 1/60, nTFEMA/nHFBA = 2.5/1), P2 (nMNEA/nBTBA = 1/15), P3 (nMNEA/nBTBA = 1/30), P4 (nMNEA/nBTBA = 1/50), P5 (nMNEA/nBTBA = 1/60, nTFEMA/nHFBA = 1/1), Supplementary Fig. 20). When the ratio of MNEA to BTBA was 1/60 (P1 (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 2.5/1) and P5 (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 1/1)), the FRET efficiency was up to 90.7% (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 21). When they were exposed to UV, the color and fluorescence were changed yellow to red, green to red, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21). Their color and fluorescence could be reversibly switched between under the irradiation of ultraviolet (UV, 365 nm, 2.8 mW/cm2) and visible light (Vis., 525 nm, 1.34 mW/cm2). Therefore, we chose P1 as the typical sample to perform subsequent optical tests. An effective photo-induced FRET process between the MNEA and BTBA were demonstrated based on a decreased fluorescence lifetime (9.67 ns to 2.76 ns, Supplementary Fig. 22). These results demonstrated that a photo-induced FRET process between the MNEA and BTBA was successfully created in the reprogrammable growing 3D structures. In addition, the thermostability of BTBA was evaluated before and after UV irradiation. When P1 were placed in a dark thermal environment (80 °C), its fluorescence intensity at 500 nm and 650 nm only presented a slight change within 24 h, indicated the excellent thermostability of BTBA-c (Supplementary Fig. 23).

Photo- and thermo-induced switching properties

The photoswitchable fluorescence property of P1 was investigated. As shown in Fig. 5a, upon the irradiation of UV (365 nm, 2.8 mW/cm2), the fluorescence intensity (500 nm) of MNEA decreased significantly within 10 min, whereas the fluorescence intensity (650 nm) of BTBA exhibited an opposite trend. This process was accompanied by a change in fluorescence from green to red (Fig. 5b). When the sample was exposed to Vis. (525 nm, 1.34 mW/cm2), the red fluorescence disappeared, and the green fluorescence returned within 12 min. In addition, when we alternately stimulate P1 with UV and Vis., no significant photobleaching were observed even more than 20 cycles, demonstrating an excellent reversibility (Fig. 5c). Based on this, we further explored the thermo-responsiveness of the 3D structure. First, we erased the 3D structure of P1 using pressing at 60 °C and fixing at 25 °C. Then, the disappeared 3D structure still maintained at 25 °C and 35 °C, whereas it can recover quickly when T was above Tg (Fig. 5d, e). Similarly, P1 can withstand 20 cycles without significant change under different stimuli (Fig. 5f). These results demonstrated that P1 have excellent responsiveness (fast response rates) and reversibility.

a Fluorescence response of P1 under UV (365 nm, 2.8 mW/cm2) and Vis. (525 nm, 1.34 mW/cm2), λex = 410 nm. b CIE and optical photographs of P1 under UV irradiation. The scale bar is 0.5 cm. c Photoswitching cycles of P1 under alternative UV (10 min) and Vis. (12 min) light irradiation, λex = 410 nm. d The height of 3D structure of P1 at different temperatures (25 °C, 35 °C, 45 °C, 55 °C). The 3D structure of P1 is eliminated by press at 60 °C and then fixed at 0 °C. e Optical photographs of 3D structure recovery at different temperatures. The scale bar is 4 mm. f Switching cycles of the 3D structure of P1 under force and heat. Inset in (f): optical photographs of 3D structure. The scale bar is 2 mm.

Growth-induced healing property

Self-healing ability is a desirable property for elongating the service time of materials55,56. We explored a growth-induced healing strategy57,58. As shown in Fig. 6a, the surfaces of all parts (Seed, P0 (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 1/1)) adhered after the application of the nutrient solution (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 1/1) because of the dipole-dipole interaction. Subsequently, in situ polymerization produced new polymer chains and formed a strong entanglement to lock the interface, resulting in a high self-healing efficiency of 72.6% (P0-1, Fig. 6b). When we used the nutrients containing more TFEMA fraction (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 2.5/1) to perform, a higher self-healing efficiency of 94.2% were obtained (P0-2, Fig. 6b). The healed sample can support 100 times its own weight (200 g, Supplementary Fig. 24). To demonstrate the advantages of growth-induced healing, we designed and fabricated a complex cup (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 25). The artificial cup was constructed by self-healing driven by dipole-dipole interaction, and then the contact points are strengthened by growth self-healing. As shown in Fig. 6c, the artificial cup can hold 9.35 g of quartz sand and 8.0 g of water without deformation. The photoswitchable fluorescence in special parts (label and handle) was observed, demonstrating that growth-induced self-healing does not affect the fluorescence property of the bonded region. This self-healing method was desired for applying it in the practical anti-counterfeiting fields.

a Schematic illustration of growth-induced self-healing process and the corresponding photographs. One of the samples was dyed with MNEA. The scale bar is 0.5 cm. b Stress-strain curves of P0, growth-induced self-healing (P0-1: nTFEMA/nHFBA = 1/1, P0-2: nTFEMA/nHFBA = 2.5/1). c Optical photographs of artificial cups prepared by growth-induced self-healing. Cup body: P0, flower and handle: P0. The scale bar is 0.5 cm. Optical photographs of artificial cup (5.6 g) containing quartz (9.35 g) sand and water (8.0 g). The scale bar is 0.5 cm. d Fluorescence photographs of artificial cup before and after UV. The scale bar is 0.5 cm.

2D/3D-encoding multistage information encryption and anti-counterfeiting

The integration of responsive fluorescence (2D) and 3D information encoding in one system could significantly enhance information security. To demonstrate this, we prepared 3D structures with varying fluorescence information and Tg (Fig. 7a). In the original state, green fluorescence information (“7”) and 3D information (“3”) were displayed and as a result, the coupled information “73” was achieved (Fig. 7a). When we pressed at 60 °C to eliminate part of the 3D information, and then fixed at 25 °C, green fluorescence information (“7”), 3D information (“1”), and coupled information (“71”) were observed. When it was exposed UV for 600 s, the new red fluorescence information (“3”) emerged, the coupled information was “31”. When the temperature increase to 30 °C and 45 °C, the red fluorescence remained unchanged, 3D information transformed to “7” and “3”, which could induced a change in coupled information (“37” and “33”). Finally, by employing Vis. (525 nm, 1.34 mW/cm2) to irradiate it, all information was returned to the original state (Fig. 7a). In addition, we grew the thirteen pillars on the matrixes to present number “8” and perform the anti-counterfeiting demonstration (Supplementary Fig. 26). We first eliminated the 3D information as an original state. Only green fluorescence (“5”) could be seen. Temperature (T1 = 30 °C and T2 = 45 °C) induced 3D information “5” and “8” to be displayed, accompanying with coupled information “55” and “58”. UV could further cause the coupled information of “88”. Finally, a press operation and the irradiation of visible light could restore system to its initial state.

a Schematic diagram and corresponding photographs of 2D/3D dual-mode coupling information encryption by stimulating with UV (365, 2.8 mW/cm2, 10 min), Vis. (525, 1.34 mW/cm2, 12 min), heat (T1: 30 °C, 5 min; T2: 45 °C, 5 min), and force. The scale bar is 0.5 cm. b Anti-counterfeiting label application design model and optical photos. The scale bar is 0.5 cm. c Schematic illustration of the unfolding of lotus petals in response to temperature and the corresponding photographs (T0: 20 °C, 5 min; T1: 30 °C, 5 min; T2: 45 °C, 5 min). The scale bar is 0.5 cm.

In practical applications, anti-counterfeiting labels are crucial for identifying counterfeits and substandard products. We tried to apply the responsive coating to create 2D/3D dual-mode anti-counterfeiting labels. As depicted in Fig. 7b, we regulated the proportion of fluorescent dyes and fluorinated monomers through twice growth, enabling the cloud and raindrops to contain different fluorescence pattern and Tg values (cloudy: P8 (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 2.0/1, nMNEA/nBTBA = 1/60), rain: P10 (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 2.5/1, nMNEA/nBTBA = 1/0)). By using force and heat as stimulus, the 3D pattern disappeared, and only a green pattern (rain) was observed. Subsequently, the different T (30 °C and 45 °C) would induce the 3D or coupled pattern of “cloudy” and “rain”. UV and press further facilitate the transformation of coupled pattern into “rain” with red fluorescence and “no pattern”. Finally, Vis. irradiation drove the coupled pattern to its original state. Inspired by the unfolding of lotus petals in response to temperature, we designed a flower that could open layer-by-layer in response to temperature. Every layer of the flower contained different fluorescence information by using a variety of masks and precisely adjusting the proportion of fluorinated monomers. Three layers were prepared using one-pot photo-induced radical copolymerization of two monomers, and then grow the 3D structure using some nutrients containing different dyes (bottom: MNEA (P11 (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 1.5/1, nMNEA/nBTBA = 1/60)), middle: BTBA (P12 (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 2/1, nMNEA/nBTBA = 0/60)), top: MNEA and BTBA (P1 (nTFEMA/nHFBA = 2.5/1, nMNEA/nBTBA = 1/60)), Supplementary Fig. 27). As shown in Fig. 7c and Supplementary Movie 1, in the initial state, flower was not open and did not display any information. With a gradual increase in temperature (T0 = 20 °C, T1 = 30 °C, and T2 = 45 °C), the petals slowly opened, and the 3D structures gradually were shown. Under UV irradiation, the green fluorescence information “HUNAN” was unchanged, and the green fluorescence of the six-point star pattern was turned into red emission. New information “HNUST” then emerged. These results showed that the responsive coating could promote the high security of anti-counterfeiting via skillfully combining 2D information and 3D information.

Discussion

We have developed a self-growing strategy that allows for the incorporation of various anti-counterfeiting technologies into one system easily. The obtained programmable 2D/3D-coupling responsive coatings not only exhibit photo-induced reversible fluorescence switching and thermo- and force-induced reversible 3D structure switching, orthogonal multi-responsibility, excellent reversibility, but also present programmability of multi-dimensional information and structures, and excellent self-healing ability. The programmability of 2D/3D-coupling information can be regulated using various parameters during the growth process, such as the components of nutrients (MNEA and BTBA) and functional monomer (TFEMA and HFBA), growth times, and growing structures. We thus expect the concept of programmable 2D/3D-coupling responsive coating to inspire more advances of anti-counterfeiting technologies with high security. This strategy will benefit areas including anti-counterfeiting, encryption, and data storage. In addition, since self-growing strategy is applicable to integrating different functions or creating specific 3D structures and texture surfaces in existed samples, we envision its future applications in soft robotics and bioelectronic interfaces.

Methods

Materials

2,2,2-trifluoroethyl methacrylate (TFEMA, 96%), 2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl acrylate (HFBA, 96%), hexamethylene diacrylate (HDDA, 90%), 2-hydroxyethyl acrylate (HEA, 98%) phenylbis(2, 4, 6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide (I819, 99%), and benzenesulfonic acid (BSA, 90%) were bought from HEOWNS. TFEMA, HDDA, HFBA, and HEA were purified by column chromatography to remove the polymerization inhibitor before use.

Preparation of seeds (P0)

A mixture solution of HDDA (cross-linker, 13.8 mg, 0.1 mmol), I-819 (photoinitiator, 85 mg, 0.2 mmol), TFEMA (1.68 g, 10 mmol), HFBA (2.36 g, 10 mmol) were placed in 1 h in reaction cells consisting of a pair of glass plates with 1.0 mm spacing, and then irradiated using Vis. (460 nm, 10 mW/cm2) for 1 h. Next, the polymer blocks were immersed into a large amount of a mixture of petroleum ether and ethanol to remove residual monomers and dried at 80 °C for 6 h to obtained seeds.

Preparation of grown samples (P1)

Taking P1 as a typical sample. The seeds were immersed into the nutrients containing HDDA (13.8 mg, 0.1 mmol), I-819 (85 mg, 0.2 mmol), TFEMA (2.40 g, 14.3 mmol), HFBA (1.35 g, 5.7 mmol), MNEA (0.15 mg, 0.0005 mmol), BTBA (20 mg, 0.03 mmol) for 1.5 h. The 3D structure (cylinder) was grown in a box using a mask. Subsequently, the growing samples were dialyzed into a mixture of petroleum ether and ethanol (three times), and then dried at 80 °C for 6 h. Next, the obtained samples were soaked into an ethanol solution containing benzenesulfonic acid (BSA, 1 wt %) and dried 25 °C for 24 h. The dried samples were heated at 80 °C for 8 h to trigger chain exchange for eliminating grown stress and then dialyzed in ethanol to remove BSA. Finally, P1 was fabricated by drying at 50 °C for 12 h. The other grown samples (P1, P2, P3, P4, P6, P7, P8, P9, P10, P11, P12) were prepared via the same process using different TFEMA and HFBA, and MNEA and BTBA. The corresponding compositions are listed in Supplementary Table 1. For growing 3D structures, the masks were selected according to demand (pillar, flower, number, pattern).

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Purohit, K., Abdul-Baki, S. & Purohit, H. Mind the inclusion gap: a critical review of accessibility in anti-counterfeiting technologies. In Proc. 2024 IEEE 6th International Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security in Intelligent Systems, and Applications (TPS-ISA), 455–460 (IEEE, 2024).

Shen, Y., Le, X., Wu, Y. & Chen, T. Stimulus-responsive polymer materials toward multi-mode and multi-level information anti-counterfeiting: recent advances and future challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 606–623 (2024).

Wang, X. et al. Manipulating electroluminochromism behavior of viologen-substituted iridium (III) complexes through ligand engineering for information display and encryption. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107013 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. Multi-stimulus room temperature phosphorescent polymers sensitive to light and acid cyclically with energy transfer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202308848 (2023).

Zuo, M. et al. A spatiotemporal cascade platform for multidimensional information encryption and anti-counterfeiting mechanisms. Adv. Optical Mater. 12, 2302146 (2024).

Yang, J. et al. Bionic micro-texture duplication and RE3+ space-selective doping of unclonable silica nanocomposites for multilevel encryption and intelligent authentication. Adv. Mater. 35, 2306003 (2023).

Quan, Z., Zhang, Q., Li, H., Sun, S. & Xu, Y. Fluorescent cellulose-based materials for information encryption and anti-counterfeiting. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 493, 215287 (2023).

Hu, W. et al. Realizing multicolor and stepwise photochromism for on-demand information encryption. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 2145–2152 (2024).

Guo, J. M. & Seshathiri, S. Visually encrypted watermarking for ordered-dithered clustered-dot halftones. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video 33, 4375–4387 (2023).

Qin, Y. & Gong, Q. Optical information encryption based on incoherent superposition with the help of the QR code. Opt. Commun. 310, 69–74 (2014).

Xie, Y. et al. 2D hierarchical microbarcodes with expanded storage capacity for optical multiplex and information encryption. Adv. Mater. 36, 2308154 (2024).

Huang, Y. et al. Stimuli-fluorochromic smart organic materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 1090–1166 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Photo-response with radical afterglow by regulation of spin populations and hole-electron distributions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218994 (2023).

Xu, W.-C. et al. Designing rewritable dual-mode patterns using a stretchable photoresponsive polymer via orthogonal photopatterning. Adv. Mater. 34, 2202150 (2022).

Xu, F. & Feringa, B. L. Photoresponsive supramolecular polymers: from light-controlled small molecules to smart materials. Adv. Mater. 35, 2204413 (2023).

Li, Z. & Yin, Y. Stimuli-responsive optical nanomaterials. Adv. Mater. 31, 1807061 (2019).

Li, C. et al. Photoswitchable and reversible fluorescent eutectogels for conformal information encryption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313971 (2023).

Tong, X. et al. Oxygen-doped carbon nitrides with visible room-temperature phosphorescence and invisible thermal-stimuli-responsive ultraviolet delayed fluorescence for security applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202415312 (2025).

Lou, D. et al. Double lock label based on thermosensitive polymer hydrogels for information camouflage and multilevel encryption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202117066 (2022).

Chen, J. et al. Hydrochromic perovskite system with reversible blue-green color for advanced anti-counterfeiting. Small 19, 2301010 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. High-throughput printing of customized structural-color graphics with circularly polarized reflection and mechanochromic response. Matter 7, 2091–2107 (2024).

Sagara, Y. et al. Rotaxanes as mechanochromic fluorescent force transducers in polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 1584–1587 (2018).

Meng, K. et al. A reversibly responsive fluorochromic hydrogel based on lanthanide–mannose complex. Adv. Sci. 6, 1802112 (2019).

Lan, R. et al. Humidity-responsive liquid crystalline network actuator showing synergistic fluorescence color change enabled by aggregation-induced emission luminogen. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2010578 (2021).

Jiang, Y. et al. Solid-state intramolecular motions in continuous fibers driven by ambient humidity for fluorescent sensors. Nat. Sci. Rev. 8, nwaa135 (2020).

Zhao, J.-L. et al. Photochromic crystalline hybrid materials with switchable properties: recent advances and potential applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 475, 214918 (2023).

Yang, H. et al. Erasable, rewritable, and reprogrammable dual information encryption based on photoluminescent supramolecular host–guest recognition and hydrogel shape memory. Adv. Mater. 35, 2301300 (2023).

Xie, Y. et al. Hydrogen bond-associated photofluorochromism for time-resolved information encryption and anti-counterfeiting. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202414846 (2025).

Chen, X., Hou, X.-F., Chen, X.-M. & Li, Q. An ultrawide-range photochromic molecular fluorescence emitter. Nat. Commun. 15, 5401 (2024).

Zhao, Y., Xie, Z., Gu, H., Zhu, C. & Gu, Z. Bio-inspired variable structural color materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 3297–3317 (2012).

Yang, M. et al. Stimuli-responsive mechanically interlocked polymer wrinkles. Nat. Commun. 15, 5760 (2024).

Sun, Y. et al. Dual-mode hydrogels with structural and fluorescent colors toward multistage secure information encryption. Adv. Mater. 36, 2401589 (2024).

Liu, N. et al. Wrinkled interfaces: Taking advantage of anisotropic wrinkling to periodically pattern polymer surfaces. Adv. Sci. 10, 2207210 (2023).

Lin, E.-L., Hsu, W.-L. & Chiang, Y.-W. Trapping structural coloration by a bioinspired gyroid microstructure in solid state. ACS Nano 12, 485–493 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Structural coloration: shear-induced assembly of liquid colloidal crystals for large-scale structural coloration of textiles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2170133 (2021).

He, Y. et al. Dynamically tunable chiroptical activities of flexible chiral plasmonic film via surface buckling. Small 21, 2407635 (2025).

Chen, D. et al. Orthogonal photochemistry toward direct encryption of a 3D-printed hydrogel. Adv. Mater. 35, 2209956 (2023).

Lou, K., Hu, Z., Zhang, H., Li, Q. & Ji, X. Information storage based on stimuli-responsive fluorescent 3D code materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2113274 (2022).

Li, T. et al. Micropatterns fabricated by photodimerization-induced diffusion. Adv. Mater. 33, 2007699 (2021).

Lyu, B., Ouyang, Y., Gao, D., Wan, X. & Bao, X. Multilevel and flexible physical unclonable functions for high-end leather products or packaging. Small 21, 2408574 (2025).

Kanika, Kedawat, G., Srivastava, S. & Gupta, B. K. A strategic approach to design multi-functional RGB luminescent security pigment-based golden ink with myriad security features to curb counterfeiting of passports. Small 19, 2206397 (2023).

Tomar, A., Gupta, R. R., Mehta, S. K. & Sharma, S. An overview of security materials in banknotes and analytical techniques in detecting counterfeits. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 54, 2865–2878 (2024).

Szydłowski, P., Madej, J. P. & Mazurkiewicz-Kania, M. Histology and ultrastructure of the integumental chromatophores in tokay gecko (Gekko gecko) (Linnaeus, 1758) skin. Zoomorphology 136, 233–240 (2017).

Wen, T. et al. Phase-transition-induced dynamic surface wrinkle pattern on gradient photo-crosslinking liquid crystal elastomer. Nat. Commun. 15, 10821 (2024).

Tang, J., Xing, T., Chen, S. & Feng, J. A shape memory hydrogel with excellent mechanical properties, water retention capacity, and tunable fluorescence for dual encryption. Small 20, 2305928 (2024).

Huang, J., Jiang, Y., Chen, Q., Xie, H. & Zhou, S. Bioinspired thermadapt shape-memory polymer with light-induced reversible fluorescence for rewritable 2D/3D-encoding information carriers. Nat. Commun. 14, 7131 (2023).

Feng, D. et al. Viscoelasticity-controlled relaxation in wrinkling surface for multistage time-resolved optical information encryption. Adv. Mater. 36, 2314201 (2024).

Matsuda, T., Kawakami, R., Namba, R., Nakajima, T. & Gong, J. P. Mechanoresponsive self-growing hydrogels inspired by muscle training. Science 363, 504–508 (2019).

Wu, B. et al. Interfacial reinitiation of free radicals enables the regeneration of broken polymeric hydrogel actuators. CCS Chem. 5, 704–717 (2023).

Xiong, X., Wang, H., Xue, L. & Cui, J. Self-growing organic materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306565 (2023).

Xiong, X. et al. Controlled macroscopic shape evolution of self-growing polymeric materials. Nat. Commun. 16, 2131 (2025).

Szabó, Á, Szöllősi, J. & Nagy, P. Principles of resonance energy transfer. Curr. Protoc. 2, e625 (2022).

Jiang, J. et al. Dual photochromics-contained photoswitchable multistate fluorescent polymers for advanced optical data storage, encryption, and photowritable pattern. Chem. Eng. J. 425, 131557 (2021).

Deng, H. et al. Highly stretchable and self-healing photoswitchable supramolecular fluorescent polymers for underwater anti-counterfeiting. Mater. Horiz. 10, 5256–5262 (2023).

Wang, S. & Urban, M. W. Self-healing polymers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 562–583 (2020).

Yang, Y., Ding, X. & Urban, M. W. Chemical and physical aspects of self-healing materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 49-50, 34–59 (2015).

Wang, H. et al. Alternating growth for insitu post-programing hydrogels’ sizes and performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2212402 (2023).

Fang, Y. et al. Damage restoration in rigid materials via a keloid-inspired growth process. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 174–179 (2022).

Acknowledgements

H.W. acknowledges support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52403266) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M760887). J.C. (Jian Chen) acknowledges support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52273206), the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFB3812400, 2023YFB3812403), Huxiang High-level Talent Gathering Project (2022RC4039). The authors appreciate Dr. Tingchuan Zhou from Analysis and Testing Center, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, for technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.W. and H.D. equally contributed to this work. J.C. (Jian Chen), J.C. (Jiaxi Cui), X.C., H.W., and H.D. conceived the concepts of the research. H.W. and H.D. designed the experiments and prepared samples. H.W., H.D., J.C. (Junyi Chen), Y.T., F.H., and Y.Z. performed the sample characterization. H.W., H.D., J.C. (Junyi Chen), F.H., J.C. (Jiaxi Cui), and J.C. (Jian Chen) analyzed the experimental data. J.C. (Jian Chen), J.C. (Jiaxi Cui), H.W., H.D., and Z.Z. wrote the manuscript. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Deng, H., Chen, J. et al. Self-growth of programmable 2D- and 3D-coupling responsive coating for anti-counterfeiting. Nat Commun 17, 1009 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67742-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67742-0