Abstract

The identity of cations plays a critical role in electrochemical CO2 and CO reduction reactions. While most research has focused on elucidating the effects of alkali metal cations, the influence of organic cations, which are widely employed in practical anion exchange membrane (AEM) electrolyzers, remains underexplored. Here, we systematically investigate the effects of a series of organic cations with varying sizes and hydrophilic/hydrophobic properties on the CO reduction reaction (CORR). By combining electrochemical online mass spectrometry for kinetic analysis, in-situ Raman spectroscopy for interfacial species characterization, and ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations to probe interfacial structures, we uncover that the structure of organic cations significantly influences the accessibility of interfacial water to the electrode surface, and thus the potential-dependent behavior of surface *H coverage, ultimately modulating the CORR selectivity. These findings provide new insights into the mechanisms governing CORR and can guide the development of efficient AEM electrolyzers for CO conversion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electrochemical CO2 reduction to valuable fuels and chemicals is a promising approach for mitigating atmospheric CO2 concentration, thus attracting widespread research interest1,2. However, the conversion of CO2 into deeply reduced products like methane (CH4), ethylene (C2H4), ethanol (EtOH), acetic acid (AcOH), and others still faces challenges such as sluggish kinetics and poor selectivity. CO is widely recognized as a key intermediate in the deep reduction of CO2. While the CO2 to CO conversion mechanism has been thoroughly elucidated3,4,5, the subsequent reduction of CO remains less clear, with various controversial mechanisms proposed for the conversion of CO to different deeply reduced products6,7,8,9. Therefore, unveiling the detailed mechanism of CO reduction reaction (CORR) is crucial, as this understanding will facilitate the design of efficient electrocatalytic interfaces for the selective production of high-value products.

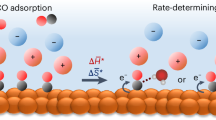

Many efforts have been made to clarify the CORR mechanism using various methods. Tafel analysis, a convenient yet effective electrokinetic study method, serves as a valuable tool for dissecting reaction pathways and discerning the rate-determining step (RDS)10,11,12. For example, the CO conversion toward C2+ products, such as C2H4, EtOH, and AcOH, exhibits a Tafel slope of approximately 118 mV dec−1 over copper electrodes13,14,15,16, indicating that the first electrochemical step involving one-electron transfer is the RDS for C2+ production. Early studies suggested that the RDS is the dimerization of two adsorbed *CO with one electron transfer (*CO + *CO + e− → *OCCO−)17,18,19. Similarly, Deng et al. also claim that the CO-CO coupling (*CO + *CO + δe− → *OCCOδ-) is the RDS of C2+ formation based on a non-linear fit of the reaction order curve in a recent study20. Other studies indicated that the reaction order of C2+ product formation falls between 0 and 1, which is inconsistent with the CO-CO coupling mechanism13,16,18. Additionally, some experimental results obtained in different pH electrolytes revealed that the C2+ production rate is comparable on the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) scale, indicating the RDS is independent of proton activity14,21. Based on previous findings, Xu et al. proposed that the hydrogenation of *CO with adsorbed water (*H2O) is the RDS for C2+ production (*CO + *H2O + e− → *CO(H) + OH−), supported by precise kinetic analysis and in-situ surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (SEIRAS)22,23. In contrast, CH4 formation depends on the proton activity. It exhibited a Tafel slope of 118 mV dec−1 at a pH below 11.3, but it decreased to 59 mV dec−1 when the electrolyte became more alkaline. The shift suggests a transition of RDS from the initial proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) process of adsorbed *CO and the later chemical hydrogenation step (with adsorbed *H or *H2O) in different pH environments and applied potentials22,23. These studies provide valuable insights into the further CO conversion mechanism, but primarily in liquid electrolytes with alkali cations (Fig. 1 left).

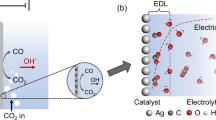

Replacing liquid electrolytes with polyelectrolytes that contain only organic cations represents a notable advancement in modern electrochemical technologies24,25,26. Specifically, for CO2 or CO reduction, anion exchange membrane (AEM) electrolyzers with pure water anolyte can not only mitigate risks such as leakage, corrosion associated with liquid electrolytes, but also prevent salt precipitation in gas diffusion electrodes (GDE)27,28. While alkali cations in liquid electrolytes were once considered essential for CO2 or CO reduction29, recent studies have demonstrated that these reductions are feasible in coordination-inhibited cation solutions or at electrode/polyelectrolyte interfaces containing only organic cations30,31,32,33. Additionally, pure water-fed electrolyzers for converting CO2 to CO or C2H4 have already been realized34,35. Our previous investigation found that different organic cations exert a significant influence on the product distribution of CO2 reduction, primarily due to their varying capability to synergistically activate CO236. However, the extent to which organic cations can influence the further *CO conversion remains unclear. Studies, such as that by Li et al.37, have shown that large quaternary alkyl ammonium cations inhibit the conversion of CO to C2H4, which is attributed to the absence of hydrogen bonding interaction between interfacial water and *CO-*CO intermediate. These investigations were mostly conducted on fully-immersed electrodes, that is, the working electrode is entirely immersed in liquid electrolytes with dissolved CO2 or CO serving as the reactant. As a result, the current densities were far lower than those of GDE-based electrolyzers (>100 mA cm−2). Previous studies on the alkali cation effect have indicated that when the GDE is employed to enhance mass transfer, with an abundant supply of CO reactant at the triple-phase interface, the CORR behavior differs significantly from that observed with fully-immersed electrodes38. Therefore, there is an urgent need for in-depth investigations into the organic cation effect on CORR, especially under the practical high-current-density conditions provided by GDE-based setups (Fig. 1 right).

In this study, we systematically investigated the structure-function relationship of organic cations in CORR using a series of aqueous quaternary ammonium hydroxide (R4NOH) electrolytes. This allowed us to independently examine the influence of organic cations (R4N+) with varying sizes and hydrophilic/hydrophobic properties. A custom-designed GDE-based flow cell was employed for electrochemical tests, ensuring an abundant supply of CO and facilitating systematic investigations into the organic cation effect under high current densities without mass-transfer limitations. Additionally, electrochemical in-situ mass spectrometry (EC-MS) was utilized to track the continuous evolution of gaseous products as a function of applied potential, providing more precise values for Tafel slope analysis. By combining electrokinetic studies, in-situ Raman measurements, and AIMD simulations, we revealed that the molecular structure of organic cations (R4N+) significantly affects the accessibility and configuration of interfacial water, which further influences the generation and consumption of adsorbed hydrogen (*H) on the electrode surface, ultimately altering the CORR selectivity.

Results

Size effect of organic cations on CO reduction performance

A homemade flow cell was employed for CORR (Supplementary Fig. 1). The working electrode used was a Cu gas diffusion electrode, fabricated through magnetron sputtering of Cu onto hydrophobic carbon paper, followed by spray coating with a Nafion binder to mitigate the electrolyte flooding (denoted as MsCu GDE). The cations in the R4NOH electrolytes can permeate the thin Nafion film due to the attraction of the negatively-charged sulfonate groups. Therefore, the cation-Nafion hybrid serves as a platform to study the catalytic characteristics of different organic cations without mass transfer limitations, similar to those at the electrode/polyelectrolyte interface in AEM electrolyzers. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image revealed that the deposited Cu layer exhibited a continuous aggregation of nanoparticles (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). CORR was first conducted in a typical KOH electrolyte, yielding a Faradaic efficiency (FE) of 8–19% for H2 and 30–40% for C2H4 within the potential range of −0.5 ~ −0.8 V vs. RHE (Supplementary Fig. 4), which aligns with literature reports on the product distribution for Cu-catalyzed CORR39,40. Additionally, it sustained a high current density of up to 1 A cm−2 at −0.8 V, due to sufficient CO supply. Therefore, this cell setup is well-suited for investigating CORR behavior under high-current-density conditions.

To investigate the organic cation effect, a series of quaternary ammonium hydroxide (R4NOH) solutions of varying cation sizes were used as electrolytes for CORR, including symmetric tetraalkylammonium cations (TMA, TEA, TPA, TBA, containing four methyl, ethyl, propyl, and butyl groups, respectively) and an asymmetric cation, diethyl-dimethyl ammonium (DEDMA), Fig. 2a–e present detailed FE of different products and the current densities (Details in Supplementary Tables 1–5). Overall, CORR performance in electrolytes containing organic cations was inferior to that with alkali metal cations (K+), particularly regarding the selectivity for C2+ products like C2H4. Among the organic cations tested, the TMA (Fig. 2a) and DEDMA (Fig. 2b), which have smaller sizes, exhibited superior C2+ selectivity. The FE for C2+ products exceeded 70% at −0.7 V, with the FE for C2H4 reaching 21%. When the cation size exceeded that of TEA (Fig. 2c–e), C2H4 production dropped significantly, consistent with previous research findings37. Additionally, we observed that the production of C1 product CH4 and the competitive product H2 increased rapidly as the cation size increased. To account for the flexibility of the alkyl chain segments, we used their gyration radius as a descriptor of cation size41,42. Obviously, the FE ratios of C2H4 to CH4 descended monotonically with the increase in the gyration radius of these cations (Fig. 2f).

a–e Faradaic efficiencies (FE) of different products and current densities, with insets showing the molecular structures of corresponding organic cations. f Relationship between the cation gyration radius and the C2H4/CH4 FE ratio. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent tests. Source data for (a–f) are provided as Source data files.

Tafel analysis to explore the size effect of organic cations

Tafel analysis was conducted to elucidate the distinct CORR behaviors in the presence of different R4N+ cations. Conventional Tafel analysis in CO(2)RR studies often relies on the linear fitting of several discrete data points43,44, primarily due to the time-consuming process required for product quantification by gas chromatography (GC), which typically takes at least several minutes. Consequently, this method provides only time-averaged information at a few specific potentials, failing to capture real-time changes in different products as the polarization potential varies. We thus constructed an in-situ electrochemical mass spectrometry (EC-MS) method for Tafel analysis (Fig. 3a), by incorporating a capillary sampling branch at the cathode outlet for MS detection. Owing to the rapid response and high sensitivity of MS analysis, this setup can record the ion currents of CORR gaseous products, such as H2, CH4, and C2H4, in real-time during linear sweeping voltammetry (LSV) tests. Since the MS ion currents are proportional to the concentration of detected products, the Tafel slope for each product generation can be determined from the logarithmic MS ion current (log im/z)–potential (E) polarization curve. A slow LSV scanning rate of 1 mV s−1 was set to achieve a steady state and reduce the influence of double-layer charging10,45. In contrast to the distinct polarization behaviors observed for C2H4 generation in these different electrolytes (Supplementary Fig. 5), H2 and CH4 production appear to be somewhat interrelated (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Figs. 6–7). Their production rates all exhibit a notable turning point at around −0.75 V, where the Tafel slope for CH4 production significantly increases at the higher overpotential range. In contrast, the Tafel slope for H2 production markedly decreases. This is likely due to the competitive consumption of surface-adsorbed *H species required for both CH4 and H2 formation, resulting in a competitive reaction dynamic. Moreover, we observed that reducing the CO partial pressure (PCO) from 1 to 0.067 atm to increase the surface *H coverage, and subsequently restoring PCO back to 1 atm, resulted in a significantly higher CH4 ion current compared to the initial level, while the C2H4 ion current returned to its original value (Supplementary Fig. 8). This indicates that CH4 production is strongly dependent on the surface *H coverage, whereas C2H4 production is not.

a Schematic illustration of the EC-MS experimental setup. b Comparison of logarithmic ion current for H2 (m/z = 2) and CH4 (m/z = 15) in different electrolytes. Note that the Tafel slope is the reciprocal of the linear fit slope. During the test, the CO flow rate was set to 20 sccm, and the LSV scan rate was 1 mV s−1. c Tafel slopes for H2 and CH4 production derived from linear fittings as shown in (b). The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent tests (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). Source data for (b, c) provided as Source data files.

Specifically, the HER Tafel slopes are all much higher than 118 mV dec−1 in the lower overpotential range (E > ca. −0.75 V, Fig. 3b), indicating that the RDS is a non-electrochemical process12. In contrast, at higher overpotentials (E <ca. −0.75 V), the HER Tafel slopes decrease with increasing R4N+ cation size (Fig. 3c). The TMA electrolyte shows a Tafel slope of 175 mV dec−1, suggesting that the RDS remains a non-electrochemical process. However, the Tafel slope drops to 118 mV dec−1 in the TEA electrolyte, which approaches the theoretical value of 118 mV dec−1 for the first electron transfer RDS, indicating the Volmer step of water dissociation (H2O + e− → *H + OH−) becomes the RDS. Further decreases in the Tafel slope are observed in the TPA (104 mV dec−1) and TBA (84 mV dec−1) electrolytes. It is probable that the RDS further shifts from the Volmer step to the subsequent *H consumption steps. Given that the *H has a low coverage on Cu surface22, the Tafel step (2*H → H2) is less likely to occur, and the Heyrovsky step (*H + H2O + e− → H2 + OH−) is more plausible for consuming *H to produce H2. The regular change in HER Tafel slopes implies that large R4N+ cations are more conducive to interfacial water dissociation to generate *H. This is likely due to the relative hydrophobicity of organic R4N+ cations, which are not hydrated as intensely as alkali cations46,47. Under cathode potentials, the interfacial electrical double layer (EDL) formed by these R4N+ cations hinders water access to the electrode surface. The larger R4N+ cations form a looser EDL, allowing easier water molecule access and dissociation on the electrode surface. This finding is also consistent with a recent study indicating that, compared with smaller TMA and alkali cations, the large TPA cation can enhance the hydrogen evolution/oxidation reaction kinetics by facilitating interfacial proton shuttling48.

For CH4 production, in the lower overpotential range (E > ca. −0.75 V), the Tafel slope is 67 mV dec−1 for TMA (Fig. 3c). It is close to the theoretical value of 59 mV dec−1 when the chemical step after a single electron transfer reaction serves as the RDS49. Although the coverage of reactants (e.g., *CO and *CO(H)) can affect Tafel slopes, recent studies have shown a low coverage of *CO on the Cu surface at 1 atm23,50, and thus coverage effects will not significantly influence Tafel slope analysis. Therefore, the first charge-transfer step (*CO + H2O + e− → *CO(H) + OH−) is unlikely to be the RDS for CH4 formation. Instead, it is probable that the subsequent chemical hydrogenation between *CO(H) and *H is the RDS, which is consistent with the views in the literature22. Notably, this is based on the assumption that the *H coverage remains constant and is independent of potential change (Case 1 in Supplementary Note 1). However, the Tafel slope could decrease further if the *H coverage varies with the potential (Case 2 in Supplementary Note 1). Theoretically, when the *H generation from water dissociation (Volmer step: H2O + e− → *H + OH−) is regarded as a pseudo-equilibrium step, the resulting Tafel slope could be lower and approach a minimum value of 30 mV dec−1 (Eq. S10, neglecting reactant coverage influence). The obtained Tafel slope indeed becomes lower for these larger cations and drops to 41 mV dec−1 in the TPA electrolyte (Fig. 3c), which corresponds well to Case 2. This is because a looser EDL, formed by large cations, improves water accessibility to the electrode surface (i.e., sufficient water supply), thus making the subsequent water dissociation more sensitive to potential changes. Regarding the largest TBA cation, there is an anomalous slight increase in the Tafel slope. It can be attributed to the fact that the further enhanced water accessibility allows more water adsorption/dissociation on the electrode surface and thus suppresses *CO adsorption, as evidenced by in-situ Raman spectra showing that the *CO band vanished completely after −0.7 V (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Regarding C2H4 production, although the selectivity is relatively high in the TMA and TEA electrolyte (Fig. 2a, c), the C2H4 Tafel slope is much higher than 118 mV dec−1 (Supplementary Fig. 5), suggesting that the RDS is a non-electrochemical process under such circumstances. In contrast, the C2H4 selectivity becomes very low in the larger-sized TPA and TBA electrolytes, but the C2H4 Tafel slope is relatively close to 118 mV dec−1. This indicates that the first electron transfer process is the RDS. For instance, as proposed in the literature, it could be the *CO(H) formation reaction (*CO + H2O + e− → *CO(H) + OH−), or *CO coupling step involving proton-coupled electron transfer (2*CO + H2O + e− → *COCO(H) + OH−)49.

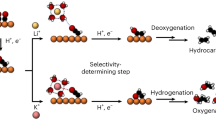

Hydrophilic/hydrophobic effect of organic cations on CO reduction

The above results indicate that the R4N+ cations with hydrophobic alkyl side chains significantly influence water accessibility and thus the proton supply on the electrode surface, leading to variations in the CORR pathway. We further examined the impact of introducing hydrophilic hydroxyl (-OH) groups into organic cations and their effect on CORR. Figure 4a, b present the CORR performance in the presence of choline and bis(2-hydroxylethyl) dimethylammonium hydroxide (DHDMA), respectively (Details in Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). Upon the introduction of the hydrophilic -OH group, HER was exacerbated, and CH4 production was inhibited, compared to TMA and DEDMA of similar size (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). Meanwhile, the C2H4 production was enhanced to some extent, and its FE remained almost unchanged with the negative shift of potential (Supplementary Fig. 12). Consequently, the C2H4/CH4 FE ratio exhibited a gradual increasing trend with the increasing number of -OH groups introduced into the cations, as shown in Fig. 4c.

Faradaic efficiencies (FE) and current densities of the MsCu GDE in the choline (a) and DHDMA (b) electrolytes, respectively. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent tests. c C2H4/CH4 FE ratios under the influence of organic cations containing different amounts of -OH groups. d Logarithmic polarization curves for CH4 formation (m/z = 15) in DHDMA(x% in molar ratio)-TEA mixed electrolytes, measured by the EC-MS method, along with detailed Tafel slope values. Source data for (a–d) provided as Source data files.

To clarify how the hydrophilic -OH group affects CORR kinetics, we also utilized the EC-MS method (Fig. 3a) to perform Tafel analyses in mixed electrolytes with varying ratios of hydrophilic DHDMA and hydrophobic TEA cations. As the proportion of hydrophilic DHDMA cations rises, the HER Tafel slope in the lower overpotential range (E > ca. −0.75 V) significantly decreases, and the inflection point around −0.75 V in the polarization curve gradually becomes less distinct (Supplementary Fig. 13). This observation can be attributed to the hydrophilic -OH groups forming hydrogen bonding interactions with interfacial water, as reflected by an increased proportion of strongly hydrogen-bonded water in the in-situ Raman analysis (Fig. 5g, vide infra). Consequently, water accessibility at the electrode surface is enhanced, promoting HER at the lower overpotentials. The HER rapidly consumes surface *H via the Heyrovsky reaction (*H + H2O + e− → H2 + OH−). Given that *H is a crucial reactant in the RDS for CH4 formation, CH4 production is gradually inhibited, and its Tafel slope climbs from 52 to 213 mV dec−1 (Fig. 4d). Moreover, the blurring of the inflection point in the HER polarization curve (Supplementary Fig. 13) may be because, after introducing -OH groups, the interfacial water composition remains largely unchanged within the tested potential range. This behavior differs significantly from that with hydrophobic R4N+ cations (Fig. 5g and Supplementary Figs. 24, 25, vide infra).

a Comparison of Raman spectra at −0.8 V. b–d Heatmaps of ν(*CO) stretching vibration under different potentials. 100% iR compensation was applied, and the solution resistance (R) was 18 Ω for TMA, 22 Ω for TPA, and 70 Ω for DHDMA. e Ratio of the ν(O-H)/ν(C-H) band area under different potentials. The gray-shaded region denotes the potential range for CORR performance testing. f Raman spectra of ν(Cu-OH) and ν(O-H) with peak deconvolution at −0.8 V. g Ratio of strongly hydrogen-bonded water (sh-H2O) under different potentials. h AIMD structural optimization of Cu(111)/water interface with different organic cations. The O, H, N, C, and Cu atoms are represented by red, gray, cyan, black, and golden colors, respectively. Hydrogen bonds are colored in dark blue, while those formed by the -OH group of DHDMA are highlighted in orange. i Phonon density of states (DOS) of -OH vibration in the AIMD simulations with different cations. The marker over the curve represents the central value of the corresponding signal. Source data for (a–g, i) are provided as Source data files.

In-situ Raman measurements and AIMD simulations

To validate the inferences drawn from the above kinetic analysis, we selected three representative organic cations with different sizes and hydrophilic/hydrophobic properties, including TMA, TPA, and DHDMA, and conducted electrochemical in-situ Raman measurements using a home-designed GDE-type spectroelectrochemical cell (Supplementary Fig. 14). Figure 5a shows the full Raman spectra acquired at −0.8 V across the three electrolytes, while Raman spectra at different potentials are provided in Supplementary Fig. 15-19. The peaks around 280 and 360–380 cm−1 are assigned to frustrated rotation and Cu-CO stretching vibrations51,52,53, respectively. The peak at 490–530 cm−1, corresponding to the Cu-OH stretching vibration54,55, gradually enhances as the potential becomes more negative. The peaks at 750 and 943 cm−1, attributed to the symmetry and asymmetry N-C4 stretching vibrations, are notably intense in the TMA electrolyte56, likely due to its smallest ionic size, which allows it to approach closer to the electrode surface. The two dashed lines indicate the D and G bands of the carbon paper substrates (Supplementary Fig. 20). The peaks at 1380 cm−1 and 1450 cm−1 are assigned to the rocking vibration of CH2 and CH3 (δ(C-H)), respectively. The band at 1800–2100 cm−1 is identified as the stretching vibration of surface adsorbed *CO intermediate. The band at 2750–3030 cm−1 is attributed to the stretching vibrations of C-H bonds (ν(C-H)), primarily arising from the contribution of organic cation aggregation at the interface rather than from CORR intermediates, from the comparison with the very weak peak at the corresponding position in the KOH electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 21). The board band spanning from 3100 to 3700 cm−1 is assigned to the ν(O-H) vibration of interfacial water. These observations provide crucial insights into the interfacial processes during CORR.

Figure 5b–d compares the ν(*CO) band presented in heatmap forms across the three electrolytes57, and Supplementary Fig. 22 separately presents the potential-dependent plots of the peak positions for the *CO (upper) and Cu-CO (lower) bands. Both bands exhibit the greatest shift as the potential becomes more negative, i.e., the largest Stark slope, in the TMA electrolyte, whereas the least shift is observed in the TPA electrolyte. These results suggest that the interfacial electric field is strongest in the presence of TMA cations, corroborating their ability to approach the electrode surface more closely and pack more closely to form a compact double-layer structure due to their relatively smaller size. In contrast, the largest-sized TPA cations form a more loosened interfacial double-layer structure. Previous studies have found that the interfacial electric field significantly affects electrocatalytic CO2 (CO) reduction58,59. In this study, choline and TMA cations, which have similar sizes and the same R-NMe3+ end group, approach the electrode with comparable proximity58. As a result, the intensities of the interfacial electric fields they form are similar, as reflected by the comparable ν(CO) Stark slope values (Supplementary Fig. 23)3,37,60. However, their CORR performances vary greatly (Figs. 2a and 4a), indicating that the interfacial electric field is not the main influencing factor. Instead, as speculated by the kinetic analysis above, the influence of different organic cation properties on interfacial water is the fundamental reason for the variations in CORR performance. In the presence of large organic cations, water molecules are more likely to overcome the barrier posed by the hydrophobic cation layer at the interface and reach the electrode surface when the overpotential increases, as indicated by a higher ν(O-H)/ν(C-H) band intensity ratio in the TPA electrolyte, compared to that in the TMA electrolyte (Fig. 5e). This observation supports the kinetic analysis speculation indicating an enhanced water accessibility in the presence of large-sized organic cations. For the DHDMA cation, the ν(O-H)/ν(C-H) band intensity ratio is even higher, confirming the hydrophilic-enhanced interfacial water supply mentioned earlier.

Comparative analysis shows that the ν(O-H) bands of DHDMA are at relatively lower wavenumbers, indicating a more coherent hydrogen bonding network (Supplementary Fig. 24). The ν(O-H) band was further deconvoluted into three components using Gaussian functions (Supplementary Fig. 25), including isolated water (i-H2O, ~3600 cm−1), weakly hydrogen-bonded water (wh-H2O, ~3450 cm−1), and strongly hydrogen-bonded water (sh-H2O, ~3260 cm−1)61,62. Figure 5f (right) provides a comparative example of the deconvoluted peaks around −0.8 V. For a quantitative perspective, the ratio of sh-H2O component is shown in Fig. 5g. The sh-H2O ratio for the hydrophilic DHDMA is consistently higher than that for the two hydrophobic cations and remains nearly constant, owing to the hydrogen bonding interaction between the -OH group and interfacial water. For both the TMA and TPA, the sh-H2O ratio shows a downward trend as the overpotential increases. This is because the hydrophobic alkyl chains in the EDL disrupt the interfacial hydrogen bonding network, and longer alkyl chains cause more significant disruption. Besides, there appears to be a correlation between the ν(Cu-OH) peak position and the integrity of the interfacial hydrogen bonding network: a higher proportion of sh-H2O tends to shift the ν(Cu-OH) peak towards higher Raman shifts (Fig. 5f left). This suggests the possibility that an interaction occurs between interfacial sh-H2O and surface -OH species, which may weaken the O-H bond and concurrently strengthen the Cu-O bond in the Cu-OH species.

Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation results elucidate how distinct organic cations influence interfacial properties. As illustrated in Fig. 5h (atom coordinates in Supplementary Data 1–3), all three cations exhibit a strong affinity for the Cu(111) surface under negative polarization, effectively repelling H2O due to their respective alkyl side chains. Notably, TPA induces a distinctive H2O-repellent cavity. Conversely, DHDMA can form hydrogen bonding interaction with H2O through its -OH group, as highlighted in Fig. 5h left. The statistical analysis of H2O molecules (represented by the density of O atoms, which excludes the O atoms on the DHDMA cation) perpendicular to the Cu surface substantiates the differences among these three organic cations (Supplementary Fig. 26). Despite the presence of an H2O-gap layer at 3.6–5.0 Å from the surface, a region occupied by the cations, the hydrophilic DHDMA exhibits a higher O atom density (i.e., higher H2O content) from 5.3 to 6.0 Å, compared to the hydrophobic TMA and TPA. Further statistics reveal that the -OH groups on DHDMA distribute at approximately 3.5 Å and 4.8 Å (Supplementary Fig. 27), thus it is reasonable to attribute the increased O atom density to the hydrophilic effect of -OH groups. The number of hydrogen bonds was also statistically analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 28). Similar to the aforementioned H2O-gap layer, for all the organic cations, the number of hydrogen bonds decreases significantly at a distance of 4–6 Å from the surface. The largest TPA results in a smaller number of hydrogen bonds at the surface than its smaller counterpart, TMA. However, the hydrogen bond numbers of DHDMA are even higher than those of the small TMA cation. In other words, the -OH groups of DHDMA alleviate the H2O-repellent cavity originating from the steric effect of organic cations. Furthermore, we calculated the phonon density of states (PDOS) for the interfaces with different cations to provide an in-depth statistical view63,64 (details in Supplementary Note 2). Figure 5h shows the PDOS curves within 2800–4000 cm−1, which represent the ν(O-H) stretching vibrations. Notably, the v(O-H) curves shift towards lower wavenumbers in the order TPA > TMA > DHDMA, as further evidenced by their central values marked in Fig. 5h. These simulation results align well with the experimental trends observed in the Raman spectra of the ν(O-H) vibration (Fig. 5f, g), providing a reasonable verification at the theoretical level. These findings corroborate the above hypothesis that hydrophilic cations increase interfacial water content and enhance the hydrogen bonding network at the electrode/electrolyte interface, thereby impacting CORR selectivity.

Discussion

In this study, we systematically investigated the effects of organic cations on CORR by integrating a GDE-based flow cell for performance evaluation, online EC-MS for Tafel analysis, in-situ Raman characterization of interfacial species, and AIMD simulations of interfacial structure. Our findings demonstrate that CORR behavior is primarily influenced by the steric and hydrophobic/hydrophilic properties of these organic cations. For hydrophobic organic cations with only alkyl chains, the interfacial EDL, formed by their aggregation, can hinder the accessibility, thus impacting the dissociation of water (i.e., proton source) on the electrode surface. This directly impacts the generation and consumption of surface *H, affecting both HER and CH4 generation kinetics (RDS: *CO(H) + *H → *CO(H)2). In contrast, the RDS for C2H4 generation appears less related to *H species. Regarding cations of different sizes, smaller organic cations such as TMA and TEA form more compact EDLs (Fig. 6a), which more effectively impede the interfacial water supply. This leads to suppressed HER and CH4 generation, turning to favor the production of C2H4 and other C2+ products. Conversely, larger cations like TPA and TBA form more loosely packed EDLs (Fig. 6b), allowing water to access the electrode surface more easily and thereby promoting HER and CH4 generation, while making C2H4 generation more difficult. For hydrophilic organic cations with -OH side chains (Choline, DHDMA), the formed EDLs can partially mitigate the gap layer in interfacial water induced by alkyl chains, and restore the hydrogen bonding network in interfacial water (Fig. 6c). This facilitates both the interfacial water supply and the Heyrovsky step for H2 formation (*H + H2O + e− → H2 + OH−), thereby accelerating the consumption of surface *H. This leads to enhanced HER and suppressed CH4 generation. Simultaneously, C2H4 generation is somewhat promoted. These insights provide a deeper understanding of the CORR mechanism in the presence of organic cations and offer valuable guidance for designing efficient alkaline polyelectrolytes (particularly ionomers) for advanced membrane electrode assembly (MEA) electrolyzers aimed at CO and pure water co-electrolysis.

Methods

Chemicals and pre-treatment

Tetramethylammonium hydroxide pentahydrate (TMAOH‧5H2O, 98%), and deuterium oxide (D2O, 99.8% D atom) were purchased from Energy Chemical. Silver oxide (Ag2O), tetraethylammonium hydroxide (TEAOH, 25 wt% in water), and tetrabutylammonium hydroxide (TBAOH, 40 wt% in water) were purchased from Aladdin. Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and potassium hydroxide (KOH) were purchased from the Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., PR China. Choline hydroxide (50 wt% in water), tetrapropylammonium hydroxide (TPAOH, 2.0 mol/L in water), and bis(2-hydroxyethyl)dimethylammonium chloride (DHDMA-Cl, 98%) were purchased from Macklin. Diethyldimethylammonium hydroxide (DEDMA, 25 wt% in water) was purchased from Adamas. Unless otherwise specified, all chemicals were used without further purification.

Bis(2-hydroxyethyl)dimethylammonium hydroxide (DHDMA-OH) was prepared via an ion-exchange method. Specifically, the DHDMA-Cl salt (4.24 g, 25 mmol) was dissolved in deionized water, and then silver oxide (5.79 g, 25 mmol) was added to the solution. The mixture was continuously stirred for 18 h at 40 °C. After centrifugation, the liquid supernatant was collected and diluted to prepare a 0.5 mol/L solution for electrochemical testing. The counter ion was converted to the hydroxide form, and the resulting solution had a pH value of 13.

Electrode fabrication

Hydrophobic carbon paper (AvCarb GDS3250) was used as the GDE substrate. The Cu catalytic layer was prepared by magnetron sputtering deposition of a Cu target (99.999%) onto the carbon paper for 45 min. The sputtering current was 100 mA, and the Ar pressure was 1.7 Pa. A 2.5 mL solution of 0.05 wt% Nafion in ethanol was sprayed onto the Cu surface, covering an area of 20 cm2, to form a hydrophobic layer that prevented electrolyte flooding. The apparent area of the work electrodes is 0.78 cm2 for CORR performance tests. The morphologies of the MsCu electrodes were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss Merlin Compact).

CORR performance tests

All the CORR performance and electrokinetic tests were carried out in a domestic flow cell at room temperature (25 °C). The chronoamperometry method was applied for performance tests over a potential range of −0.65 to −0.90 V vs. RHE, with a scanning step of 50 mV. A porous Ti plate coated with Ir was used as the counter electrode, and an Hg/HgO electrode was used as the reference electrode. The applied potential was converted to the RHE scale using the following equation:

Here, the \(\Delta\)E represents the potential difference between the Hg/HgO electrode and the RHE, which was calibrated manually to be 0.92 V (pH = 13.7). Eapplied stands for the applied potential. The pH values of different R4NOH electrolytes without hydroxyl groups are around 13.7. The pH values of cations with hydroxyl groups are slightly lower (Choline: 13.3 and DHDMA: 13.0).

CO was introduced to the back side of the GDE at a flow rate of 20 sccm. The electrolyte solution was circulated with a peristaltic pump at a flow rate of 8 mL min−1. Gaseous products were analyzed in-line using gas chromatography (MICRO GC FUSION®, INFICON), and the Faradaic efficiency (FE) is calculated from the corresponding peak area as the following equation:

Where nie is the electron transfer number of product i, \({N}_{i}\) is the amount of substance of product i per unit time quantified by the gas chromatography, \(I\) represents the overall current, and F is the Faradaic constant. Liquid products were quantified by the 1H NMR (AVANCE NEO 400 MHz Digital NMR Spectrometer), and the FE is also calculated from Eq. 2.

For the electrokinetic study, the LSV test was conducted with a sweeping rate of 1 mV s−1. The sampling capillary of mass spectroscopy (PM-DEMS, Protech®) was introduced into the outlet pneumatic hose to collect the product mixture. As a result, changes in the signal of a specific m/z over time reflected changes in the production rate with potential. The electrochemical measurements were conducted using the Autolab PGSTAT302N workstation, and the mass spectrum was acquired using the PM-QMS mass spectrometer (Pro-tech).

Electrochemical in-situ Raman measurements

The working electrode was the same as that used in electrochemical performance tests. A roughened Ag wire was used as the quasi-reference electrode, and the potential was calibrated using the HgO/Hg electrode after each test. The potentials are 100% iR-corrected by subtracting the iR drop from the applied potentials after each test. The electrode surface area is 0.07 cm2. In-situ Raman tests were conducted using the HORIBA (XploRA™ PLUS) Raman spectrometry. The spectra subtracting baseline are then processed using a Savitzky-Golay smoothing filter (window size = 10, order = 2) to achieve a higher signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio, and the excitation laser wavelength was 638 nm. Raman spectra were collected starting from the open circuit potential, decreasing in 100 mV intervals in the negative direction until exceeding the CORR performance testing potential range (−0.9 V vs. RHE).

Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations

This work utilizes the Vienna Ab initio simulation package (VASP), employing the plane-wave pseudopotential method, to perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations65,66. The PBE functional within the GGA framework is chosen to describe electron exchange-correlation interactions, while Grimme’s D3 method enhances accuracy by incorporating dispersion corrections in all simulations67,68. A plane-wave energy cutoff of 400 eV ensures adequate computational accuracy, and the first-order Methfessel-Paxton scheme with a smearing width of 0.1 eV is adopted for electronic structure calculations. All simulations are performed without spin polarization, focusing solely on the gamma point of the Brillouin zone and disregarding any symmetry considerations. To simulate realistic system behavior, a time step of 1.0 fs is used in conjunction with a Nose-Hoover thermostat to maintain constant temperature (NVT) conditions at 298 K. Before data analysis, each modified interface system undergoes a 17 ps simulation to ensure systems are well equilibrated. Statistical analyses are then conducted using snapshots extracted from the final 12 ps of these trajectories. The simulated Cu/water interface consists of a four-layer 6 × 6 orthogonal Cu(111) slab, upon which 110 water molecules were overlaid. This arrangement results in an approximate water density of 1.0 g/cm3. A vacuum layer with a thickness of ~2.4 nm separates the system from its periodic images, preventing spurious interactions. A single molecule is strategically positioned near the Cu surface, allowing it to interact with both the metallic substrate and the surrounding water molecules.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Shin, H., Hansen, K. U. & Jiao, F. Techno-economic assessment of low-temperature carbon dioxide electrolysis. Nat. Sustain. 4, 911–919 (2021).

Belsa, B., Xia, L. & García De Arquer, F. P. CO2 electrolysis technologies: bridging the gap toward scale-up and commercialization. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 4293–4305 (2024).

Chernyshova, I. V., Somasundaran, P. & Ponnurangam, S. On the origin of the elusive first intermediate of CO2 electroreduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E9261–E9270 (2018).

Li, M. et al. Heterogeneous single-atom catalysts for electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001848 (2020).

Rosen, J. et al. Mechanistic insights into the electrochemical reduction of CO2 to CO on nanostructured Ag surfaces. ACS Catal. 5, 4293–4299 (2015).

Heenen, H. H. et al. The mechanism for acetate formation in electrochemical CO(2) reduction on Cu: selectivity with potential, pH, and nanostructuring. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 3978–3990 (2022).

Garza, A. J., Bell, A. T. & Head-Gordon, M. Mechanism of CO2 reduction at copper surfaces: pathways to C2 products. ACS Catal. 8, 1490–1499 (2018).

Birdja, Y. Y. et al. Advances and challenges in understanding the electrocatalytic conversion of carbon dioxide to fuels. Nat. Energy 4, 732–745 (2019).

Nitopi, S. et al. Progress and perspectives of electrochemical CO2 reduction on copper in aqueous electrolyte. Chem. Rev. 119, 7610–7672 (2019).

Van Der Heijden, O., Park, S., Vos, R. E., Eggebeen, J. J. J. & Koper, M. T. M. Tafel slope plot as a tool to analyze electrocatalytic reactions. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 1871–1879 (2024).

Limaye, A. M., Zeng, J. S., Willard, A. P. & Manthiram, K. Bayesian data analysis reveals no preference for cardinal Tafel slopes in CO2 reduction electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 12, 703 (2021).

Xu, Y., Yang, H., Chang, X. & Xu, B. Introduction to electrocatalytic kinetics. Acta Phys. Chim. Sin. 39, 2210025 (2023).

Lu, X., Shinagawa, T. & Takanabe, K. Product distribution control guided by a microkinetic analysis for CO reduction at high-flux electrocatalysis using gas-diffusion Cu electrodes. ACS Catal. 13, 1791–1803 (2023).

Hori, Y., Takahashi, R., Yoshinami, Y. & Murata, A. Electrochemical reduction of CO at a copper electrode. J. Phys. Chem. B 101, 7075–7081 (1997).

Liang, Y. et al. Efficient ethylene electrosynthesis through C–O cleavage promoted by water dissociation. Nat. Synth. 3, 1104–1112 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Effectively increased efficiency for electroreduction of carbon monoxide using supported polycrystalline copper powder electrocatalysts. ACS Catal. 9, 4709–4718 (2019).

Cheng, T., Xiao, H. & Goddard, W. A. Full atomistic reaction mechanism with kinetics for CO reduction on Cu(100) from ab initio molecular dynamics free-energy calculations at 298 K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, 1795–1800 (2017).

Schreier, M., Yoon, Y., Jackson, M. N. & Surendranath, Y. Competition between H and CO for active sites governs copper-mediated electrosynthesis of hydrocarbon fuels. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 10221–10225 (2018).

Schouten, K. J. P., Kwon, Y., Van Der Ham, C. J. M., Qin, Z. & Koper, M. T. M. A new mechanism for the selectivity to C1 and C2 species in the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide on copper electrodes. Chem. Sci. 2, 1902 (2011).

Deng, W. et al. Unraveling the rate-determining step of C2+ products during electrochemical CO reduction. Nat. Commun. 15, 892 (2024).

Kastlunger, G. et al. Using pH dependence to understand mechanisms in electrochemical CO reduction. ACS Catal. 12, 4344–4357 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Electrokinetic and in situ spectroscopic investigations of CO electrochemical reduction on copper. Nat. Commun. 12, 3264 (2021).

Chang, X. et al. C − C coupling is unlikely to be the rate-determining step in the formation of C2+ products in the copper-catalyzed electrochemical reduction of CO. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202111167 (2022).

Fan, J. et al. Immobilized tetraalkylammonium cations enable metal-free CO2 electroreduction in acid and pure water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202317828 (2024).

Xiao, L. et al. First implementation of alkaline polymer electrolyte water electrolysis working only with pure water. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 7869 (2012).

Lu, S., Pan, J., Huang, A., Zhuang, L. & Lu, J. Alkaline polymer electrolyte fuel cells completely free from noble metal catalysts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 20611–20614 (2008).

She, X. et al. Pure-water-fed, electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to ethylene beyond 1000 h stability at 10 A. Nat. Energy 9, 81–91 (2024).

Zhao, J. Y. et al. A focus on the electrolyte: realizing CO2 electroreduction from aqueous solution to pure water. Chem. Catal. 3, 100471 (2023).

Monteiro, M. C. O. et al. Absence of CO2 electroreduction on copper, gold and silver electrodes without metal cations in solution. Nat. Catal. 4, 654–662 (2021).

Mi, Z., Wang, T., Xiao, L., Wang, G. & Zhuang, L. Catalytic peculiarity of alkali metal cation-free electrode/polyelectrolyte interfaces toward CO2 reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 17377–17383 (2024).

Gao, Z. et al. Promoting electrocatalytic CO2 reduction via anchoring quaternary piperidinium cations onto copper electrode. Electrochim. Acta 458, 142509 (2023).

Fan, M. et al. Cationic-group-functionalized electrocatalysts enable stable acidic CO2 electrolysis. Nat. Catal. 6, 763–772 (2023).

Weng, S., Toh, W. L. & Surendranath, Y. Weakly coordinating organic cations are intrinsically capable of supporting CO2 reduction catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 16787–16795 (2023).

Li, W. et al. Bifunctional ionomers for efficient co-electrolysis of CO2 and pure water towards ethylene production at industrial-scale current densities. Nat. Energy 7, 835–843 (2022).

Yin, Z. et al. An alkaline polymer electrolyte CO2 electrolyzer operated with pure water. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 2455–2462 (2019).

Xue, L. et al. Dual-role of polyelectrolyte-tethered benzimidazolium cation in promoting CO2/pure water co-electrolysis to ethylene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202309519 (2023).

Li, J., Li, X., Gunathunge, C. M. & Waegele, M. M. Hydrogen bonding steers the product selectivity of electrocatalytic CO reduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 9220–9229 (2019).

Yan, W., Wu, T., Liu, J., Zheng, Z. & Ma, M. Mass transport-dependent c–c bond formation for CO electroreduction with alkali cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 9990–10001 (2025).

Jouny, M., Luc, W. & Jiao, F. High-rate electroreduction of carbon monoxide to multi-carbon products. Nat. Catal. 1, 748–755 (2018).

Xia, R., Lv, J.-J., Ma, X. & Jiao, F. Enhanced multi-carbon selectivity via CO electroreduction approach. J. Catal. 398, 185–191 (2021).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Lu, T. A comprehensive electron wavefunction analysis toolbox for chemists. Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 161, 082503 (2024).

Chen, Y., Li, C. W. & Kanan, M. W. Aqueous CO2 reduction at very low overpotential on oxide-derived Au nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 19969–19972 (2012).

Ma, W. et al. Electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to ethylene and ethanol through hydrogen-assisted C–C coupling over fluorine-modified copper. Nat. Catal. 3, 478–487 (2020).

Anantharaj, S., Noda, S., Driess, M. & Menezes, P. W. The pitfalls of using potentiodynamic polarization curves for tafel analysis in electrocatalytic water splitting. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 1607–1611 (2021).

Nilsson, E. J., Alfredsson, V., Bowron, D. T. & Edler, K. J. A neutron scattering and modelling study of aqueous solutions of tetramethylammonium and tetrapropylammonium bromide. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 11193–11201 (2016).

García-Tarrés, L. & Guàrdia, E. Hydration and dynamics of a tetramethylammonium ion in water: a computer simulation study. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 7448–7454 (1998).

Zhao, K. et al. Action at a distance: organic cation induced long range organization of interfacial water enhances hydrogen evolution and oxidation kinetics. Chem. Sci. 14, 11076–11087 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. pH effects on the electrochemical reduction of CO(2) towards C2 products on stepped copper. Nat. Commun. 10, 32 (2019).

Hou, J., Chang, X., Li, J., Xu, B. & Lu, Q. Correlating CO coverage and CO electroreduction on Cu via high-pressure in situ spectroscopic and reactivity investigations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 22202–22211 (2022).

Zhan, C. et al. Revealing the CO coverage-driven C–C coupling mechanism for electrochemical CO2 reduction on Cu2O nanocubes via Operando Raman spectroscopy. ACS Catal. 11, 7694–7701 (2021).

Smith, B. D., Irish, D. E., Kedzierzawski, P. & Augustynski, J. A surface enhanced raman scattering study of the intermediate and poisoning species formed during the electrochemical reduction of CO2 on cpper. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 4288–4296 (1997).

Li, J. et al. Silica-copper catalyst interfaces enable carbon-carbon coupling towards ethylene electrosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 12, 2808 (2021).

Ma, H., Ibáñez-Alé, E., You, F., López, N. & Yeo, B. S. Electrochemical formation of C2+ products steered by bridge-bonded *CO confined by *OH domains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 30183–30193 (2024).

Shao, F. et al. Surface water as an initial proton source for the electrochemical CO reduction reaction on copper surfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202214210 (2023).

Deng, Z. & Irish, D. E. SERS investigation of the adsorption and decomposition of tetramethylammonium ions on silver electrode surfaces in aqueous media. J. Phys. Chem. 98, 11169–11177 (1994).

Van Der Velden, E. CMasher: scientific colormaps for making accessible, informative and ‘cmashing’ plots. J. Open Source Softw. 5, 2004 (2020).

McGregor, J.-M. et al. Organic electrolyte cations promote non-aqueous CO2 reduction by mediating interfacial electric fields. Nat. Catal. 8, 79–91 (2025).

Resasco, J. et al. Promoter effects of alkali metal cations on the electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 11277–11287 (2017).

Ge, A. et al. Interfacial structure and electric field probed by in situ electrochemical vibrational stark effect spectroscopy and computational modeling. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 18674–18682 (2017).

Wang, Y.-H. et al. In situ Raman spectroscopy reveals the structure and dissociation of interfacial water. Nature 600, 81–85 (2021).

Shen, L. et al. Interfacial structure of water as a new descriptor of the hydrogen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 22397–22402 (2020).

Thomas, M., Brehm, M., Fligg, R., Vöhringer, P. & Kirchner, B. Computing vibrational spectra from ab initio molecular dynamics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 6608 (2013).

Yu, C.-C. et al. Vibrational couplings and energy transfer pathways of water’s bending mode. Nat. Commun. 11, 5977 (2020).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B 46, 6671–6687 (1992).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22522205, 22172115, 21991154, 21991150, 22472121), the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFA1508002, 2023YFF0723100), and Science and Technology Innovation Talent Program of Hubei Province, China (2024DJA024). G.W. also acknowledges the Start-Up Grant of Wuhan University and the Xiaomi Young Talents Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z. and G.W. supervised this work. L.X. (Liwei Xue) designed and conducted most experiments and data analysis. F.W. performed AIMD simulations and assisted with calculation elucidation and writing. J.W. and G.W. (Guangzhe Wang) contributed to Raman characterizations. X.H. helped with data analysis. H.W. contributed to flow-cell tests. L.X. (Li Xiao) joined the discussion. All authors contributed to the work and discussions during manuscript preparation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jun Gu, Jia Zhu, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, L., Wei, F., Wang, J. et al. Steric and hydrophilic/hydrophobic effects of organic cations on electrochemical CO reduction. Nat Commun 17, 1018 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67761-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67761-x