Abstract

Electroconversion of acetylene towards polymer-grade ethylene (EAE) is recognized as a promising substitution for thermo-catalytic route. The excessive active-hydrogen supplies a high current density induces the conspicuous hydrogen evolution, reducing the ethylene Faradaic efficiency (FE). Here, we develop a Cu-Pd single atom alloy (SAA) catalyst, achieving a 90.5% FE with a large ethylene partial current density of −1.16 A cm−2, and maintain stability for 110 h at −0.2 A cm−2 in the flow-cell system. In membrane electrode assembly, Cu-Pd SAA delivers a 90.1% ethylene FE and ~100 % conversion at −2.5 A (−0.1 A cm−2), along with 500 h stability for crude ethylene purification. Combined in-situ spectroscopy and DFT calculation reveal that the catalyst facilitates the direct hydrogenation of acetylene via Pd-H species rather than hydrogen spillover. This mechanism concurrently lowers the EAE energy barrier and suppresses the hydrogen evolution reaction. This work provides insights for designing high-efficiency electrocatalysts for hydrogenation electrosynthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ethylene (C2H4), as an essential building block for producing commodity chemicals, mainly stems from petroleum cracking1,2,3,4. The development of acetylene (C2H2) production derived from coal or methane provide a feasible route, that is acetylene hydrogenation to ethylene, to preclude oil dependence5,6,7,8. At present, industrial hydrogenation of acetylene to ethylene still depends on thermo-catalytic process (TAE), which demands extensive energy consumption and excess high-purity hydrogen9,10,11. In this case, intensive carbon emissions and high cost is inevitable. As an emerging technology in recent years, electro-conversion of acetylene towards ethylene (EAE) powered by renewable energy has been recognized as a promising replacement to TAE12,13,14,15,16. A fundamental issue in making EAE profitable is to maintain remarkable ethylene selectivity at high current density10. However, the high current density will lead to severe hydrogen evolution and low ethylene selectivity, especially at ampere level17,18. In these regards, there is a pressing need to design efficient electrocatalysts for achieving high ethylene selectivity and ampere-level current density simultaneously.

The ethylene electrosynthesis from acetylene and water mainly consists of two processes, that is the formation of H* from water dissociation and acetylene hydrogenation to ethylene17,19,20. Cu catalysts have been demonstrated efficient for electrocatalytic acetylene hydrogenation to ethylene21,22. However, the lack of active sites for generating adequate H* from water dissociation impede ethylene production at high rate23. In this regard, some strategies like introducing vacancy, halogen, and unsaturated site on Cu have been presented to reinforce water dissociation towards H* and improve the ethylene production rate10,17,23,24,25. Despite some progress has been made, the EAE still faces the challenges in achieving ampere-level ethylene partial current density with high FE (over 90%). This can be attributed to spillover hydrogenation effect. Based on recent reports, EAE process generally follows electron-coupled proton transfer mechanism or hydrogen-localization transfer mechanism, which demands H-species spillover to hydrogenation sites9,26. As a result, the migration of spilled H-species inevitably enhances the collision of themselves, eventually accelerating the formation of H2 (Figure S1A), especially at ampere-level current density. Moreover, the high energy barrier of hydrogen spillover on Cu would decelerate the whole EAE process. Therefore, one can expect that a non-spillover hydrogenation model (Figure S1B) could be an ideal pathway to break activity-selectivity trade-off of EAE even at ampere-level current density.

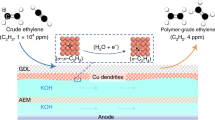

In this work, we develop a series of single-atom alloys (SAAs) with isolated metal atoms embedded in the Cu lattice (Cu-M SAA, where M = Pd, Pt, Ru, Ag) to enable efficient EAE process. Among these, the Cu-Pd SAA achieves a competitive ethylene partial current density of −1.16 A cm−2 with a Faradaic efficiency (FE) of 90.5%. In a membrane electrode assembly, the Cu-Pd SAA demonstrates a 90.1% ethylene FE and nearly 100% acetylene single-pass conversion at −2.5 A (−0.1 A cm−2), along with a long-term stability of 500 h for crude ethylene purification. Combining in situ experiments with DFT calculations, we show that the Cu-Pd SAA would facilitate a non-spillover hydrogenation mechanism for EAE. Specifically, the Pd sites promote the decomposition of H2O, forming Pd-H species. Subsequently, the acetylene molecule undergoes direct hydrogenation with the adsorbed activated hydrogen at the Pd sites to generate ethylene. The supply of activated hydrogen during the hydrogenation step may rely on Pd-H mediation rather than hydrogen spillover, which not only reduces the energy barrier for EAE but also suppresses hydrogen evolution.

Results and Discussions

Preparation and characterization of Cu-Pd SAA

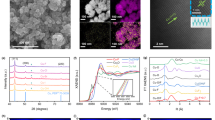

In this study, the Cu-Pd SAA catalyst is synthesized using a pre-catalyst electro-derivation strategy (Figure S1C)27. Specifically, the pre-catalyst Cu3N-Pd is formed by introducing ammonia into a solution containing Cu and Pd precursors. The resulting Cu3N-Pd exhibits a flower-like morphology, with Cu, N, and Pd elements uniformly distributed (Fig. 1A and Figs. S2–4). The crystalline structure of Cu3N is confirmed in Cu3N-Pd (Fig. 1B and Figure S5), with the lattice incorporating heavier atoms (Fig. 1C). Atom-scale microscopy further reveals that the pre-catalyst consists of Pd atoms doped into the Cu3N crystal structure (Fig. 1D and Figure S6). Following this, the Cu3N-Pd is deposited onto a gas diffusion layer (GDL) electrode and reduced at −0.8 V vs. RHE to yield the Cu-Pd SAA, which is then peeled off for subsequent analyses.

A–D Structure of Cu3N-Pd: (A) TEM image, (B, C) HAADF-STEM image (the insert of Figure B is the fast Fourier transform of the HAADF-STEM image, and crystal planes corresponding to the lattice points in reciprocal space are labeled with circles. The Pd atoms are present in identification areas in C), and the (D) atomically resolved elemental mapping (the designated areas are found to show the Pd atom position illustrated in Figure S6). E–O Structure identification of Cu-Pd SAA: (E) TEM image, (F, G) HAADF-STEM (the insert of Figure (F) is the fast Fourier transform of the HAADF-STEM image, and crystal planes corresponding to the lattice points in reciprocal space are labeled with circles. The Pd atoms are presented in identification areas in G), and the Figure (H) atomically resolved elemental mapping (the 3D morphology of the square box is presented in Figure (I, J), and the specific atomic array of the rectangle area is enlarged in K), (I–K) intensity profile results (the green dots denote the Pd atoms and the red dots are Cu atoms), (L) XRD patterns of Cu3N-Pd (cyan) and Cu-Pd (blue), (M) Pd k-edge XANES spectra (the inset is enlarged the indicated area), (N) Pd k-edge EXAFS spectra and (O) wavelets transformation.

The electro-derivation leads to total N-eliminating (Figure S7), the Pd content is ~1.3 wt.% (Table S1), and areal density of Pd and Cu sites is 4.6 and 10.5 atom nm−2 based on the BET surface area coupling with HAADF-STEM image and atomically resolved elemental mapping (Figure S8). Moreover, its morphology transfers from flower-like to cubic in 400 s (Figure S9). As shown in Fig. 1E and Figure S10, the cubic Cu-Pd SAA takes a size about 60 nm. The crystallization is confirmed (Figure S11), and the lattice space is determined as 2.08 Å, assigning to the Cu (111) plane (Fig. 1F)28,29. Fig. 1G displays randomly distributed bright-spot in Cu array, confirming the maintain of heavy atoms doping. The atomically resolved elemental mapping results further reveal the heavy atoms are isolate Pd sites (Fig. 1H). Intensity analysis of Fig. 1H demonstrates a significant increase in the intensity of the Pd column compared to the Cu column (Fig. 1I-J). Moreover, the intensity profile takes along Cu line shows even distance for Cu-Cu and Cu-Pd (Fig. 1K), suggesting Pd atoms prefer to insert into Cu lattice rather than adsorb on the surface. The XRD patterns of Cu-Pd SAA display only diffraction features of crystalline Cu (Fig. 1L), with no peaks corresponding to Pd particles or Cu3N, confirming the uniformity of the Cu-Pd SAA. The X-ray adsorption fine structure (XAFS) is exploited to further investigate the coordination environment of Cu and Pd. The Cu k-edge XANES spectra and EXAFS spectra confirm the formation of metallic Cu (Figure S12). The Pd k-edge XANES spectra (Fig. 1M) show the white line intensity of Cu-Pd SAA locates between Pd foil and PdO, suggesting that Pd exists in a partially positive oxidation state. The Pd k-edge EXAFS spectra of Cu-Pd SAA shows a dominant peak at 2.25 Å (Fig. 1N), shorter than the 2.53 Å for Pd-Pd coordination (Fig. 1O)30. Considering the smaller radius of Cu atom than Pd atom, this peak can be attributed to the Pd-Cu coordination. Fitting results at R space further confirm the Pd-Cu coordination numbers as 7.9 (Figure S13 and Table S2). The above results solidly demonstrate the embedding of Pd atom into Cu lattice in Cu-Pd SAA, forming single atom alloy with strong Cu-Pd coordination. Moreover, SAA of Cu-Pt, Cu-Ag and Cu-Ru are also prepared and investigated (Figure S14–16), as well as a pure Cu catalyst Cu NP (Figure S17), to reveal the effect of metal doping.

Electrocatalytic performance in EAE

For EAE evaluation, Cu-Pd SAA is coated on 1 cm2 GDL and tested in the three electrodes flow-cell in 1 M KOH solution, with 70% C2H2 (balanced with Ar) as feed gas. All potentials involved are converted to RHE without resistance correction because of the negligible influence (Figure S18 and Table S4). The LSV curves of Cu-based catalysts show increased current density in C2H2 compared with that in Ar (Figure S19), revealing their intrinsic EAE activity. Metal doping significantly enhances the activity of Cu, and Cu-Pd SAA emerges as the competitive-performing catalyst (Fig. 2A), achieving an overall current density of −1.29 A cm−2 at −1.6 V. The ECSA-normalized LSV and normalized C2H4 formation rate are also shown identical activity trend (Figure S20, Table S5). Product quantification via gas chromatography (Figure S21) reveals C2H4 as the main product, with C4 and H2 as by-products. Cu-Pd SAA exhibits the FE of C2H4 beyond 90% over the potential range from −0.4 to −1.6 V (Fig. 2B), which is competitive among other Cu-M SAA (Figure S22). The onset potential for C2H2 semihydronation is as low as -0.278 V (Figure S23), higher than that of H2 evolution (−1.233 V), accompanying with an ampere-level C2H4 partial current density of −1.16 A cm−2 at −1.6 V (Fig. 2C). This result further indicates that the high C2H4 selectivity of Cu-Pd SAA stems from the strong suppression of HER, as evidenced by the negligible H2 FE below −1.2 V (Fig. 2B). The TOF of C2H4 on Cu sites was calculated as 21.7 s−1 and the TOF of H* generated on Pd sites was 23.1 s−1. Considering the areal density of metal atoms, there is sufficient H supply for EAE from Pd (Note 1 in SI). The EAE performance of Cu-Pd SAA keeps stable at Ecell of −2.2 V for 110 h (Fig. 2D), as well as at higher current density (Figure S24), and used catalyst maintained its structure (Figure S25), demonstrating the robustness. The single-path conversion of C2H2 increases along overall current density without impacting ethylene selectivity (Fig. 2E and Figure S26), reaching 72.1% at −1.2 A cm−2 under 10 mL min−1 of C2H2 flow. The fast C2H2 conversion and high selectivity of Cu-Pd SAA further lead to the C2H4 formation rate of 21.4 mmol h−1 cm−2 at −1.6 V (Fig. 2F). The above results illustrate that the Cu-Pd SAA is competitive, in aspects of conversion, selectivity, dynamics, capacity and stability (Fig. 2G)10,15,17,18.

A LSV curves of Cu-Pd, Cu-Pt, Cu-Ru, Cu-Ag and Cu NP in C2H2. The insert is the LSV curve of Cu-Pd in 70 mol% C2H2 (purple) and Ar (pink). B FE and current density at different potentials. C The partial current density for C2H4 (blue) and H2 (orange). (D) Long-term stability test. (E) The single-path conversion at 30 mL min−1, 20 mL min−1 and 10 mL min−1 flow rate under 70% C2H2 atmosphere. F The production rate of C2H4 of Cu-Pd, Cu-Pt, Cu-Ru, Cu-Ag and Cu NP in C2H2 at different potentials. G Comparison with other catalysts. (H–J) direct generation of polymer-grade C2H4 from 70 % C2H2 in Ar (H, J are the chromatogram of 70 mol% acetylene feed gas and polymer-grade ethylene product, respectively. The Figure I is the cell voltage of the series system). The results of A-F are measured using a three-electrode flow cell (1 cm2) in 1 M KOH at room temperature under 70 mol% C2H2/Ar flow (30 mL min−1). The result of H is measured using a tandem flow-cell device at room temperature under 70 mol% C2H2/Ar flow (6 mL min−1). Error bars correspond to the s. d. of three independent measurements, and the maximum measurement error is ±3.6% (s. d.). The data points without error bars represent single measurements. The results are presented without iR compensation.

In addition to its performance with 70% C2H2, Cu-Pd SAA also demonstrates effective operation with feed-gas concentrations as low as 1% (Figure S27), encouraging us to direct generation of polymer-grade C2H4 from 70% C2H2 (in Ar) using Cu-Pd SAA. This process is practiced in a tandem device with straight channel flow-cell (1 cm2) as front-end to reduce C2H2 concentration, and meandering channel flow-cell (25 cm2) as trailing-end to treat residual C2H2 (Figure S28). The current for the front-end is optimized at −600 mA (−600 mA cm−2) to achieve the efficiency (Figure S29), while the trailing-end operates at −550 mA (−22 mA cm−2) to adapt the reduced C2H2 concentration. After passing through this tandem device, nearly 100% C2H2 is converted, with negligible residual C2H2 detected in the C2H4 product (Fig. 2H), meeting the requirements for polymer-grade C2H431. This process remains stable for at least 9 h. Moreover, the Cu-Pd SAA can also be used in C2H2 elimination from crude ethylene (Figure S30), the C2H2 residual was kept below 5 ppm (C2H2 conversion over 99.95%) and the H2 content in the production gas is less than 1.5%, stably gains polymer-grade C2H4 for at least 70 h (Figure S31).

Mechanistic insight

In situ time-dependent Cu k-edge XAFS measurements are conducted at a constant −1.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl to monitor the evolution of the Cu-Pd SAA. The FT EXAFS spectrum of the pre-catalyst Cu3N-Pd reveals two peaks corresponding to Cu-N and Cu-Cu bonds with equal intensity (Fig. 3A) at OCP. Upon applying a potential, the Cu-N bond intensity decreases over time in Ar, with only Cu-Cu bonding detectable in the Cu-Pd SAA after 400 s. The reduction in Cu-N bonding is further confirmed by the negative shift of the pre-edge feature over time in Ar (Fig. 3B), indicating a decrease in the oxidation state of Cu towards 0. After reduction, the gas flow is switched from Ar to C2H2 for 300 s. Under C2H2, the oxidation state of Cu in Cu-Pd SAA shows a slight increase, attributed to the interaction between Cu and reaction intermediates. This interaction is further investigated using potential-dependent in situ Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 3C, D, Figure S32). Signals at ~1109, 1250, and 1500 cm−1 are assigned to polyacetylene32, while the band at ~1641 cm−1 corresponds to the v(C ≡ C) stretching vibration10, indicating C2H2 adsorption on both Cu-Pd SAA and Cu NPs. When the applied potential is set to −0.4 V, a band associated with adsorbed C2H4 appears at ~1550 cm−1 over Cu-Pd SAA, with intensity increasing as the potential is negatively shifted (Fig. 3C)33,34. This suggests that the hydrogenation of C2H2 is significantly enhanced over Cu-Pd SAA compared to Cu NP (Fig. 3D). The adsorption energies of the intermediates are calculated using DFT to elucidate the roles of Cu and Pd (Fig. 3E, Figure S33 and Supplementary data). The Pd sites exhibit less negative adsorption energy for C2H2 and more negative adsorption energy for H2O compared to Cu sites. This indicates that C2H2 preferentially adsorbs on Cu, which is subsequently maybe involved in the hydrogenation process. Perhaps, In the other hand, Pd is inclined to activate water to provide the hydrogen source for hydrogenation. The Cu-Pd SAA shows a relatively low KIE of 1.39 (Fig. 3F).

Time-depend in-situ Cu k-edge (A) FT EXFAS spectra and (B) XANES spectra during the formation of Cu-Pd SAA and EAE process (the green and blue dash line indicates the position of the Cu-N and Cu-Cu bonding in Fig. 3A, respectively. And the purple dash line represents electrolysis in C2H2 environment). C, D Potential-depend in-situ Raman spectra (the blue and red dash line indicate the characteristic Raman band of ethylene and acetylene, respectively. The black dash lines represent the signals of polyacetylene). E Adsorption energy of C2H2 and H2O. F Kinetic isotope effect, KIE, the maximum measurement error is ±3.7% (s. d.). G Time-depend in-situ Raman spectra of Cu-Pd SAA in EAE. H Nyquist plots measured at −0.4 V vs. RHE, inset: the fitting circuit and R2 value (the Ru of Cu-Pd, Cu-Ru, Cu-Pt, Cu-Ag and Cu NP is 1.33 ± 0.10 Ω, 1.32 ± 0.13 Ω, 1.30 ± 0.25 Ω, 1.31 ± 0.22 Ω, 1.33 ± 0.16 Ω, respectively). I The energy variation for H* transferring on the surface of Pd atom doped Cu (111) at 0 V. J Free energy diagram for the hydrogenation of C2H2 at 0 V. Error bars correspond to the s. d. of three independent measurements. The results are presented without iR compensation.

To investigate the hydrogen supply, the effect of pH in the electrolyte is examined. A typical electron-coupled proton transfer process (*CxHy + H2O + e− → *CxHy+1 + OH−) is more favorable under relative low pH. 9 However, the overall FE of the Cu-Pd SAA shows negligible variations across different KOH concentrations (Figure S34), indicating that the electron-coupled proton pathway is not significant. Thus, the effective hydrogen source provided by Cu-Pd SAA is likely the active H* generated from water dissociation. This H* supply is further supported by the reduced C2H2 conversion observed upon the addition of tert-butanol (t-BuOH) to the electrolyte (Figure S35), as t-BuOH is a capture to prevent H* from participating in hydrogenation17. Fig. 3G illustrates the time-dependent in situ Raman spectra during EAE. The Cu-Pd SAA exhibits a band corresponding to adsorbed H* on Pd (Pd-H) at ~2115 cm−1 35, with stable adsorption over 5 min. Furthermore, the fitting on Nyquist plots from in situ EIS measurements reveal a significantly smaller R2 (0.15 Ω) for Cu-Pd SAA (Fig. 3H and Table S3), indicating reduced H* adsorption resistance36. Given the relatively negative adsorption energy of Pd-H (Figure S36), the Pd sites are probable to interact strongly with H*, which impedes its desorption (Figure S37) and spillover on Cu-Pd SAA.

To further elucidate the behavior of H*, the transfer energy of H* on Pd-doped Cu (111) is calculated at 0 V (Fig. 3I and and Supplementary data). For Cu-Pd SAA, the transfer barrier for H* from Pd to an adjacent Cu site (IM-2 to IM-3) is 2.0 eV. In Fig. 3J (Supplementary data) and Figure S38-39, the rate determining step (RDS) for EAE is identified as the interaction of H* with *C2H2 to TS-1, and the energy barrier on Cu-Pd sites is 0.80 eV (at 0 V). The H* transfer barrier is higher than the RDS barrier of EAE on Cu-Pd SAA. In contrast, for pure Cu, the transfer barrier for H* between two Cu atoms (IM-5 to TS-6) is 0.43 eV, lower than the hydrogenation barrier (0.95 eV). These results probably indicate that the H* from Pd-H preferentially reacts directly with C2H2 gathered by Cu, rather than transferring to adjacent Cu, characterizing a non-spillover hydrogenation process mediated by Pd-H species

For deeply illustrating the non-spillover process, pioneering works with spillover system need to be discussed. Lv et. al. reported a Pd-Cu alloy containing PdCu fcc phase and PdCu bcc phase37. The bcc was energetically favorable or water dissociation but energetically unfavorable for H-recombination, the fcc was the opposite of bcc. Thermodynamically, the H* generated on bcc tended to spillover to fcc to accomplish the H-recombination, and was confirmed by the enhanced HER activity at high proportion of the bcc phase. In this work, the Pd and Cu sites in Cu-Pd SAA are somehow like bcc and fcc phase energetically, but the HER activity during EAE process showed slight distinction at different Pd content (Figure S40), excluding the H* migration from Pd to Cu. This agrees with the relatively strong Pd-H interaction and the high H* transfer barrier of Cu-Pd SAA. Moreover, the competitive EAE has faster H* consumption than HER via non-spillover process with adsorbed C2H2 on Cu-Pd SAA, decreasing the H* collisions, thus suppressing the HER. Consequently, the overall EAE performance of Cu-Pd SAA is enhanced. It must be mentioned, the non-spillover mechanism described above was based on the unique structure of Cu-Pd with strong Pd-H interaction, which is not universally applicable to all EAE processes. Both non-spillover and spillover can boost EAE by suppressing HER, the former focuses on weakening the generation of free-H*, and the latter aims to reduce the local H* concentration, it depends on the interaction strength of H with active sites.

EAE performance in MEA

Compared with flow-cell reactor, the two electrodes membrane electrode assembly (MEA) exhibits higher energy efficiency with reduced operating voltage, as well as a simplified design, making it more feasible for practical applications38. Therefore, the EAE performance of Cu-Pd SAA is tested in MEA with different C2H2 concentration, to further explore its application potential. The ability of Cu-Pd SAA to deal with 70% C2H2 is tested in a 25 cm2 MEA (Figure S41). The single path C2H2 conversion increased with applied current, and surpass 90% at −2.0 A in Fig. 4A (−0.08 A cm−2, Figure S42). Moreover, the FE of C2H4 keeps above 90%, even at a total current of −2.5 A (−0.1 A cm−2) is applied (Fig. 4B and Figure S42), demonstrating the favorable EAE efficiency Cu-Pd SAA in MEA. Whereas model catalytic studies often employ high concentration feed gas, industrial feedstock is ubiquitously more dilute. The acetylene derived from coal via an arc-plasma process typically exhibits a C2H2 concentration of 15%. This substantial disparity imposes an imperative for catalysts to retain efficiency under low-concentration regimes. Figure 4C reveals a 73% C2H2 conversion and 98% C2H4 selectivity at −600 mA cm−2 of Cu-Pd SAA, in a 1 cm2 MEA (Figure S43) under 15% C2H2 in Ar. Moreover, when a tandem device composed by a 1 cm2 and a 25 cm2 MEA is used (Fig. 4D), the 15% C2H2 is almost totally converted to C2H4. This tandem device combines the ability of 1 cm2 MEA to reduce C2H2 concentration and the capacity of 25 cm2 MEA to deal with low concentration feed gas, resulting the C2H2 residual in the production keeps blow 5 ppm for at least 15 h (Fig. 4E), demonstrating the potential of Cu-Pd SAA to produce polymer-grade ethylene with coal-derived C2H2 as raw materials. However, the overall FE for C2H4 is 16.1%, which mainly attributed to the 25 cm2 MEA because of its immature technology (Figure S44). The relatively low FE will significantly increase the electricity cost for ethylene production. Although the by-product green hydrogen can be used as an additional product to partially offset the electricity cost, the electro-hydrogenation device still needs further optimization in future research to enhance the energy efficiency.

A Conversion of C2H2 and (B) FE of C2H4 in 70% C2H2 in Ar, 25 cm2 MEA, flow rate of 20 mL min−1, and 0.1 M KOH anolyte (the transverse red line directs the location of 90% FE for ethylene). C Conversion in simulative coal-derived C2H2, 1 cm2 MEA, flow rate of 20 mL min−1, and 0.1 M KOH anolyte. D−F The tandem device of 1 cm2 MEA and 25 cm2 MEA (D, F are the chromatogram of 15% acetylene feed gas and polymer-grade ethylene product, respectively. The (E) is the schematic diagram of the MEA series system). G Long-term stability of EAE in the tandem device with simulative coal-derived C2H2 (Ecell is −3.4 V for 1 cm2 MEA). H The effect of flow rate on the EAE of crude ethylene (1% C2H2 residual) in 25 cm2 MEA (the red line indicates the limitation of 5 ppm acetylene). I The simulative purification of crude ethylene, 25 cm2 MEA, flow rate of 20 mL min−1, current set as −50 mA (the red dash line indicates the limitation of 5 ppm acetylene). Error bars correspond to the s. d. of three independent measurements, and the maximum measurement error is ±2.8% (s. d.). The data points without error bars represent single measurements. The results are presented without iR compensation.

The purification of crude ethylene (1% C2H2 (10000 ppm) and 20% C2H4 balanced with Ar) is another prospective application of EAE, especially with MEA. When treating crude ethylene in a 25 cm2 MEA (Fig. 4F and Figure S45), the C2H2 residual can be controlled blow 5 ppm with a flow from 20 ~ 40 mL min−1 (maximal space velocity is 8.57 × 104 mL gcat−1 h−1), the conversion of C2H2 is above 99.95%. The stimulative purification process runs for as long as 500 h (Fig. 4G and Figure S46), with a stable Ecell of −2.3 V, hydrogen generation blow 2% and C2H2 residual less than 5 ppm. Overall, the EAE performances in MEA disclose the practical application value of Cu-Pd SAA in efficiently and stably generating polymer-grade ethylene via EAE with different raw materials, making it one of the promising catalysts for acetylene semihydrogenation (Table S6).

In summary, Pd-doped Cu is developed for the electrocatalytic semi-hydrogenation of acetylene to ethylene. The Pd-H intermediate is supposed to facilitate a non-spillover hydrogenation process. By circumventing the active H* transfer step, the EAE barrier is relatively lowered, while the competitive HER is suppressed. As a result, the Cu-Pd SAA achieves an ampere-level ethylene partial current density of −1.16 A cm−2 with a FE exceeding 90% in a flow cell. Furthermore, the EAE performance in MEA underscores the potential of Cu-Pd SAA for practical applications. The polymer-grade ethylene can be continuously produced for at least 500 h during the stimulative crude ethylene purification process. Our findings offer a perspective for designing electrocatalytic hydrogenation processes.

Methods

Chemical and materials

Commercialized reactants employed in experiments are analytical grade as received without further purification. 1-Nonanol (98%), hexane (97%) were purchased from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. Cupric acetate anhydrous (98%), palladium (II) chloride (Pd, 59–60%), platinum (IV) chloride (Pt, 57%), ruthenium (III) chloride (Ru, 47%), silver nitrate (99.8%), tert-butyl alcohol (t-BuOH), nafionTM perfluorinated resin solution (D2021CS), potassium hydroxide (KOH) and potassium sulfate were obtained from InnoChem Science & Technology Co., Ltd. Both of GDL applied for flow-cell system and MEA system were received from Sinero Technology Co., Ltd. named as YLS-30T and SGL 28BC, respectively. Anion exchange membrane (Fumasep FAA-3-50, Sustainion X37-50 grade RT), alkaline ionomer Sustainion XA-9 and nickel foam were harvest from SCI Material Hub.

Preparation of precursor Cu3N-Pd

Cu3N-Pd precursor was prepared via in-situ doping Pd atoms throughout the process from Cu3N seeds then epitaxial growth to nanoflowers, according to previous reports with some modifications. Typically, 2 mg PdCl2 was dissolved in 10 mL 1-Nonanol via the assistance of ultrasonic wave about 40 mins denoted as solution A. Then, 200 mg Cu(CH3COO)2 was dispersed in 90 mL1-nonanol with 30 mL min−1 NH3 bubbling till forming sapphire blue solution at room temperature denoted as solution B. Afterwards, solution A was injected into solution B with vigorous stirring and mixed solution was heated to 383.15 K maintaining for 1 h. Ultimately, 150 mL min−1 NH3 stream continuously bubbled into solution at 463.15 K for 30 mins before the product was cooled to ambient temperature. The Cu3N-Pd product was collected and washed with hexane three times by centrifugation and then vacuum drying overnight.

Preparation of precursor Cu3N-M (M = Pt, Ru, Ag) and Cu3N

Similarly, Cu3N-Pt, Cu3N-Ru and Cu3N-Ag were harvest through resemblance courses as that of preparing Cu3N-Pd, besides solution A was consisted of 3.4 mg PtCl2, 4.1 mg RuCl3 or 2.5 mg AgNO3 to introduce diverse noble metal ions for doping, respectively. For obtaining Cu3N precursor, 200 mg cupric acetate was directly dissolve in 1-nonanol with 30 mL min−1 ammonia flow without other metal ion, then the solution was heated to 383.15 K holding for 1 h. NH3 bubbling rate was altered to 150 mL min−1 during system’s temperature was heated up to 463.15 K maintaining for 30 min. After it cooling naturally, the product Cu3N was washed by hexane and dried in vacuum.

Preparation of electrocatalyst Cu-Pd, Cu-Pt, Cu-Ru, Cu-Ag and Cu NP loaded gas diffusion electrode

Cu-M (M=Pd, Pt, Ru, Ag) and Cu NP were prepared through in-situ electrical derivation of relevant precursors in a flow cell. Typically, 10 mg Cu3N-Pd was suspended in 1.5 mL aqueous ethanol (1:1, v/v) containing 5 μL nafion by ultrasonic dispersion uniformly for 1 h before it was spraying onto 1 cm×2.5 cm GDL (0.5 cm×2 cm effective area) with 1.1 mg ~ 1.3 mg mass loading (mass change of the electrode upon loading). Then, Cu3N-Pd was reduced in 1 M KOH at −1.8 V (V vs. Ag/AgCl) during 600 s with Ar atmosphere, marked as Cu-Pd GDE (the loading of Cu-Pd and was approximated 1.04 mg (1.1 mg/206 × 64 × 3/0.987) based on mass of precursor, and the mass loading of Pd species was 0.014 mg based on Table S1 and the mass of the precursor). For 25 cm2 (5 cm × 5 cm) GDE, 28 mg Cu3N-Pd was coating on GDL and was applied at −3.75 A for 900 s in 1 M KOH under continuous Ar flow by galvanostatic method. The Cu-Ru (the Ru mass loading was approximated 0.011 mg), Cu-Pt (the Pt mass loading was approximated 0.027 mg), Cu-Ag (the Ag mass loading was approximated 0.015 mg) and Cu NP (loading 1.03 mg) were obtained through the same procedure as that of Cu-Pd catalyst, originated from Cu3N-Ru, Cu3N-Pt, Cu3N-Ag and Cu3N, respectively.

Electrochemical measurements

CHI 1130 C and CHI 1140D were employed in electrochemical experiments that were conducted in a series of flow cells. Typically, the GDE consisted of electro-reduced precursor served as working electrode and 0.5 mm thickness nickel foam worked as the counter electrode with a saturated Ag/AgCl electrode as a reference electrode, which was placed close to the GDE. The gas chamber, cathode chamber, anode chamber and supporting plate constituted a representative flow cell with straight gas flow path for 1 cm2 (0.5 cm × 2 cm) and meandering channel for 25 cm2 (5 cm × 5 cm). An anion exchange membrane (Fumasep FAA-3-50, 45 µm thickness, 1.5 cm × 3.0 cm for 1 cm2 flow-cell and 6 cm × 6 cm for 25 cm2 flow-cell, soaked in 1 M KOH for 24 h before employment) was arranged intermediate position to separate cathode chamber and anode chamber. The flow rate of feed gas was set as 30 mL min−1 and 1 mL min−1 KOH was cycle pumped as catholyte (50 mL) and anolyte (50 mL) by peristaltic pumps, except as otherwise noted. The gas obtained from the outlet of gas chamber directly flowed to the quantitative loop (1 mL) of gas chromatography to analyze composition of gaseous products. All potentials involved were converted to RHE scale without any solution correction as following Eq. (1), and the pH was set to 14.

For the electrochemical measurements in membrane electrode assembly (MEA), the cathode and anode (titanium fiber paper loaded with IrO2, 2 mg cm−2) were attached to the either side of the anion exchange membrane (sustainion X37-50 grade RT, 50 µm thickness, 2.0 cm × 2.0 cm for 1 cm2 MEA and 6.5 cm × 6.5 cm for 25 cm2 MEA, soaked in 0.1 M KOH for at least 72 h). The Ar or C2H2 feed gas was bubbled through deionized water to increasing moistening then flowed to the inlet of cathode chamber with ‘S’ type flow field integrated into current collector before products gas was pretreated via a cold trap to be introduced to gas chromatography. Galvanostatic method was applied during 300 s for 1 cm2 (1 cm × 1 cm) at −150 mA and −3.75 A for 25 cm2 (5 cm × 5 cm) persisting 1000 s to harvest Cu-Pd catalyst from Cu3N-Pd under Ar atmosphere (20 mL min−1) with 0.1 M KOH consecutively pumped through anode (2 mg cm2, IrOx/titanium fiber paper).

Polymer grade ethylene was obtained via tandem system due to sufficient gas residence time originated from high concentration acetylene. The series-wound flow cell system was consisted of pre-cell (1 cm2) and post cell (25 cm2) with three electrode system. The post-cell purified the residual C2H2 to below 5 ppm at −550 mA after the pre-cell converted 70% C2H2 at −600 mA cm−2 with 6 mL min−1 feed gas flow rate. The individual peristaltic pump flow path independently forced 1 M KOH to tandem system at 1 mL min−1 for pre-cell and 5 mL min−1 for post-cell. Carbon balance was controlled between 97% and 99%. Similarly, tandem system also was designed for MEA consisted of pre-MEA (1 cm × 1 cm) and post-MEA (5 cm×5 cm) to convert simulated raw coal-derived C2H2 (15%). The acetylene feed gas was transferred to pre-MEA with water vapor at 20 mL min−1 and adopted amperometric i-t curve at −3.4 V about −500 mA cm−2, then polymer grade ethylene was identified by GC coupled with a cold trap and captured from outlet of post-MEA at −2.0 A after Cu-Pd catalyst was activated in Ar flow via two-electrode system. A carbon balance exceeding 97% was achieved.

The use of scaled-up components, a flow cell and a membrane electrode assembly (MEA) with an area of 25 cm2, was necessary to address the conversion of acetylene impurities in an ethylene-rich stream. 1% C2H2 (20% C2H4 balanced with Ar) was converted to C2H4 with lower than 5 ppm acetylene residuals at 20 mL min−1 at −50 mA for both reactors through chronopotentiometry via two-electrode system. The anolyte of flow-cell was 1 M KOH and 0.1 M KOH was introduced to MEA.

For preparation of electrolyte, 1 M KOH was harvest by dissolving 2.8 g KOH into 40 mL deionized water. After the solution was cooling to room temperature, a 50 mL volumetric flask was utilized to contain the alkali solution and diluted to 50 mL with deionized water. For other concentration of KOH, only proportionally adjusting the mass of KOH with the remaining steps. For the H* capture tests, 1 mL of t-BuOH was

incorporated in KOH solution before diluting to 50 mL with deionized water. The electrolyte involved was freshly prepared and stored in graduated bottles at room temperature.

Characterization of the electrocatalysts

The morphologies of catalysts were performed by SEM working on Apro S at 8.0 kV. The high-resolution TEM and atomically resolved elemental mapping was recorded on JEM-ARM 200 F (JEOL) with spherical aberration corrector. The X ray diffraction (XRD) was operated on Bruker D8 advance diffractometer with range from 10° to 90°. The chemical and composition environment were characterized on ESCALAB Xi+ photoelectron spectron spectra (XPS) to distinguish the valence state of Cu and noble metal of precursor and catalysts. To further explicit valence and distribution mode of Pd atoms and Cu atoms, the EXAFS data was obtained by X ray absorption fine structure spectra. Also, the in-situ XAS measurement of Cu k-edge adsorption was carried out in Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for recording structure evolution process of Cu3N-Pd to Cu-Pd under Ar atmosphere for 400 s at -0.8 V (V vs. RHE) and valence fluctuation after switching to C2H2 for 300 s at −1.4 V (V vs. RHE) with a three-electrode cell. Operando Raman spectra was collected in a Raman flow cell equipped with Pt wire as a counter electrode and GDL loaded Cu-Pd as working electrode beneath observable window with a 532 nm laser. 1 M KOH was circulated through cathodic an anodic chamber at 2 mL min−1 and 70% C2H2 flowed through gas chamber and potentials ranged from OCP to −1.6 V (V vs. RHE) applied after catalysts formed at −150 mA cm−2. The time resolution spectra was also conducted at −1.0 V (V vs. RHE) during 300 s under Ar flow.

Performance assessments

Gas chromatography (Panna, A6) equipped with a TCD and a FID was utilized to analyzed the component and content of gas products (H2, C2H4, C2H2, C4) collected from outlet of the flow-cell system or the MEA system. Hydrocarbon (C2H4, C2H2, C4) was separated on Plot Al2O3 column and H2 was determined on Porapak Q and Molecular 5 A in tandem. External standard method was constructed to estimate the content of each substance. The partial current density (jpartial) of gas and the Faraday efficiency (FE) were determined as Eq. (2):

Where, v is gas flow rate, mL s−1; δ is the concentration of related component determined by the external standard method by GC; n is the charge transfer number of related component; F is the faraday constant, 96485 C mol−1; Vm is the molar volume of gas, 24 L mol−1; Jtotal is the total current density.

The formation rate (R) of C2H4 was acquired according to Eq. (3):

Where, Qtotal is the total amount of charge consumed during electrolysis time (t, h); s is the geometric area of working electrode.

The H2 volume generated in the process of experiments was determined based on Eq. (4):

Where, Voutlet is the H2 volume in product gas collected from outlet of flow cell; Vinlet is the volume of feed gas provided to system.

The theoretical current was calculated as Eq. (5) with assumption that C2H2 in feed gas was completely consumed.

Where, P is the pressure of atmosphere, 101.3 KPa; R and T are the molar gas constant and the temperature set as 8.314 J (mol K)−1 and 293.15 K, respectively; vi is the velocity of C2H2 in the feed gas.

The conversion of acetylene and selectivity of ethylene were obtained on the basis of carbon balance range from 97% to 99% via Eqs. (6) and (7):

Where, cfeed, cx, \({c}_{{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{2}{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{6}}\) and \({c}_{{{{{\rm{C}}}}}_{4}}\) represent the concentration of acetylene in feed gas; the calculated concentration of residual acetylene, generated ethane and C4 collected gas from outlet of electrolytic cell by applying external standard method.

The turnover frequency (TOF) of the C2H4 and H2 was calculated based on the Eq. (8):

Where, I is partial current density (A cm−2), NA is Avogadro constant (6.02×1023), z is the number of electrons transferred of species, F is Faraday’s constant (96485 C mol−1), n is the number of active sites.

Computer details

The Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP) was utilized via the frozen-core all-electron projector-augment-wave (PAW) method to conduct the DFT calculations. The exchange and correlation potential was evaluated through the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) of generalized gradient approximation (GGA). The cutoff energy for the plane-wave basis set was set to 450 eV. The decoupling between neighboring systems was implemented based on a 5-layer 4 × 4 Cu (111) slab with a vacuum region of 15 Å above it. A Ru, Pd, Pt or Ag atom substituted a Cu atom in 同the surface of Cu (111) slab to simulate the slab of Cu-111-Ru, Cu-111-Pd, Cu-111-Pt, and Cu-111-Ag, respectively. The geometry optimizations were performed until the forces on each ion was reduced below 0.01 eV/Å, and a 3 × 3 × 1 Monkhorst-Pack k-point sampling of the Brillouin zone was used. The van der Waals interaction was shaped by the DFT-D3 method.

The Gibbs free energy (∆G) is calculated as Eq. (9)

where, EDFT is the total energy of DFT calculated system. ∆EZPE is the variation of the zero point energy between the adsorbed molecule and molecule in the gas phase, T is the temperature (300 K) and ∆S is the molecule entropy of difference from absorbed state to gas phase.

The adsorption energy (Eads) was calculated based on Eq. (10)

where, Esurface is the representative energy of the Cu-111, Cu-111-Pd, Cu-111-Pt, Cu-111-Ru, or Cu-111-Ag slab and Emolecule is the energy of the C2H2 or H2O molecule. Emolecule+surface represents the total energy of the adsorbed system.

Data availability

All the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Huang, R. et al. Acetylene hydrogenation to ethylene by water at low temperature on a Au/α-MoC catalyst. Nat. Catal. 6, 1005–1015 (2023).

Najari, S. et al. Oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane: catalytic and mechanistic aspects and future trends. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 4564–4605 (2021).

Gomez, E., Yan, B. H., Kattel, S. & Chen, J. G. Carbon dioxide reduction in tandem with light-alkane dehydrogenation. Nat. Rev. Chem. 3, 638–649 (2019).

Jang, J. H. et al. Electrochemically initiated synthesis of ethylene carbonate from CO2. Nat. Synth. 3, 846–857 (2024).

Liu, C. J., Mallinson, R. & Lobban, L. Nonoxidative Methane Conversion to Acetylene over Zeolite in a Low Temperature Plasma. J. Catal. 179, 326–334 (1998).

Schobert, H. Production of Acetylene and Acetylene-based Chemicals from Coal. Chem. Rev. 114, 1743–1760 (2014).

Corma, A. Introduction: Chemicals from Coal, Alkynes, and Biofuels. Chem. Rev. 114, 1545–1546 (2014).

Ma, Y. J. et al. Direct Conversion of Methane to Ethylene and Acetylene over an Iron-Based Metal–Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 20792–20800 (2023).

Wang, S. H. et al. Highly efficient ethylene production via electrocatalytic hydrogenation of acetylene under mild conditions. Nat. Commun. 12, 7072 (2021).

Zhao, B. H. et al. Economically viable electrocatalytic ethylene production with high yield and selectivity. Nat. Sustainability 6, 827–837 (2023).

Studt, F. et al. Identification of Non-Precious Metal Alloy Catalysts for Selective Hydrogenation of Acetylene. Science 320, 1320–1322 (2008).

Shi, R. et al. Room-temperature electrochemical acetylene reduction to ethylene with high conversion and selectivity. Nat. Catal. 4, 565–574 (2021).

Bu, J. et al. Selective electrocatalytic semihydrogenation of acetylene impurities for the production of polymer-grade ethylene. Nat. Catal. 4, 557–564 (2021).

Wang, Z. P. et al. Highly selective acetylene-to-ethylene electroreduction over Cd-decorated Cu catalyst with efficiently inhibited carbon-carbon coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202400122 (2024).

Chen, F. P. et al. Ethylene electrosynthesis from low-concentrated acetylene via concave-surface enriched reactant and improved mass transfer. Nat. Commun. 15, 5914 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Deprotonated 2-thiolimidazole serves as a metal-free electrocatalyst for selective acetylene hydrogenation. Nat. Chem. 16, 893–900 (2024).

Bai, L. et al. Efficient industrial-current-density acetylene to polymer-grade ethylene via hydrogen-localization transfer over fluorine-modified copper. Nat. Commun. 14, 8384 (2023).

Huang, L. S. et al. Electrocatalytic Acetylene Hydrogenation in Concentrated Seawater at Industrial Current Densities. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202405943 (2024).

Gao, X. et al. Highly Efficient and Selective Electrocatalytic Semihydrogenation of Acetylene to Ethylene via Continuous Proton Feeding and Accelerated Transfer on Cu NP/Fe NC Composite. Adv. Funct. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202415384 (2024).

Cheng, C. Q. et al. Promoting Water Dissociation and Weakening Active Hydrogen Adsorption to Boost the Hydrogen Transfer Reaction over a Cu−Ag Superlattice Electrocatalyst. Angewandte Chemie Int. Edition https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202413897 (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Identification of Copper as an Ideal Catalyst for Electrochemical Alkyne Semi-hydrogenation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 126, 3037–3042 (2022).

Zheng, M. et al. Recent Advances in Electrocatalytic Hydrogenation Reactions on Copper-Based Catalysts. Adv. Mater. 36, 2307913 (2024).

Wu, Z. L. et al. Near 100% Conversion of Acetylene to High-purity Ethylene at Ampere-Level Current. Adv. Mater. 36, 2408681 (2024).

Xue, W. Q. et al. Electrosynthesis of polymer-grade ethylene via acetylene semihydrogenation over undercoordinated Cu nanodots. Nat. Commun. 14, 2137 (2023).

Liu, C. B. et al. Designed Nanomaterials for Electrocatalytic Organic Hydrogenation Using Water as the Hydrogen Source. Acc. Chem. Res. 56, 1872–1883 (2023).

Wu, Y. M. et al. Selective Transfer Semihydrogenation of Alkynes with H2O (D2O) as the H (D) Source over a Pd-P Cathode. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 21170–21175 (2020).

Zhao, C. M. et al. In Situ Topotactic Transformation of an Interstitial Alloy for CO Electroreduction. Adv. Mater. 32, 2002382 (2020).

Gao, J. et al. Electrochemical synthesis of propylene from carbon dioxide on copper nanocrystals. Nat. Chem. 15, 705–713 (2023).

Xie, M. C. et al. Fast Screening for Cu-based Bimetallic Electrocatalysts: Efficient Electrocatalytic Reduction of CO2 to C2+ Products on Magnesium-Copper. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202213423 (2022).

Ji, Y. L. et al. Selective CO-to-acetate electroreduction via intermediate adsorption tuning on ordered Cu–Pd sites. Nat. Catal. 5, 251–258 (2022).

Schbib, N. S. et al. Kinetics of Front-End Acetylene Hydrogenation in Ethylene Production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 35, 1496–1505 (1996).

Liu, G. K. et al. Electrochemical polymerization of acetylene on Rh electrodes probed by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J. Electroanalytical Chem. 594, 73–79 (2006).

Zhang, L. et al. Efficient electrocatalytic acetylene semihydrogenation by electron–rich metal sites in N–heterocyclic carbene metal complexes. Nat. Commun. 12, 6574 (2021).

Shirakawa, H. et al. Raman Scattering and Electronic Spectra of Poly(acetylene). Polym. J. 4, 460–462 (1973).

Lin, X., Hu, F. S. et al. Electron Divergence of Cuδ− and Pdδ+ in Cu3Pd Alloy-Based Heterojunctions Boosts Concerted C≡C Bond Binding and the Volmer Step for Alkynol Semihydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 18451–18458 (2024).

Chen, S. Y. et al. N,O-C Nanocage-mediated high-efficient hydrogen evolution reaction on IrNi@N,O-C electrocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 304, 120996 (2022).

Lv, X.-H. et al. Hydrogen Spillover Accelerates Electrocatalytic Semi-hydrogenation of Acetylene in Membrane Electrode Assembly Reactor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 8668–8678 (2024).

Cao, X. et al. Identification of Cu0/Cu+/Cu0 interface as superior active sites for CO2 electroreduction to C2+ in neutral condition. Chem 10, 2089–2102 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the photoemission endstation beamline 1W1B station in the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) and beamline BL14W1 in Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) for help with the XAFS characterizations. This work is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22575187, 22275147 and 21902150 to Y.Q., 52301289 to K.L., 52122212, 12274391, 22321001 and 12404225 to Y.L.), Shaanxi Key Science and Technology Innovation Team Project (2025RS-CXTD-018 to Y.Q.), the Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, (ZDBS-LY-SLH003 to Y. L.), the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi (2024JC-YBMS-115 to Y.Q.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Q. and L.B. designed the experiments, K.L. performed the DFT calculation and wrote the original draft. X.H. and Y.L. characterized the materials via STEM and obtained the data of atom scale mapping. L.Z. carried out the measurement of XAS. L.B., and D.L. conducted the experiments and performed the operando Raman spectra in company with J.S., M.S. and C.K. All authors participated in interpretation of mechanism and thank J. Bai. (Jinbo Bai), C.K. and Y.Z. for the assistance of insightful suggestion. Thanks for the assistance of characterizing the features of materials via TEM and constructive suggestions for DFT calculation with insight by J. B. (Jintao Bai).

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jianhua Shen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bai, L., Han, X., Li, D. et al. Ampere-level electroconversion of acetylene towards polymer grade ethylene via Pd-H mediated non-spillover hydrogenation. Nat Commun 17, 1020 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67764-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67764-8