Abstract

Increasing the fidelity of single-qubit gates requires a combination of faster pulses and increased qubit coherence. However, these requirements can be contradictory. Additionally, increasing the drive power can heat the qubit’s environment and degrade coherence. In this work, we circumvent this issue and achieve rapid gates by pumping a transmon’s native Kerr at approximately one third of the qubit’s resonant frequency. The subharmonic Rabi rate of the process is proportional to applied drive amplitude cubed, allowing for rapid gates. In addition, we demonstrate that filtering can be used to protect the qubit’s coherence while performing rapid gates. Single qubit gates as short as 37.4 ns are demonstrated with fidelity of 99.91%. We present theoretical calculations indicating that drive induced multi-photon decay will not limit qubit lifetime; calculated power absorption also indicates that this technique could reduce cryostat heating for fast gates, a vital requirement for large-scale quantum computers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-fidelity single qubit control is one of the fundamental requirements for gate-based quantum computing. While many factors can limit gate fidelity, such as cross-talk1,2 and leakage to non-computational states3, the most fundamental are gate speed and qubit coherence4,5,6,7,8, with recent improvements driven more by increased coherence than enhanced speed9,10. However, for superconducting qubits, single qubit gates typically use resonant driving of a qubit transition, in which the requirements for fast gates and coherent qubits are contradictory.

For instance, to protect the qubit coherence time, weakly coupled drive ports and heavily attenuated lines are typically used to suppress qubit photon leakage, thermal noise10,11, and out of band radiation12. As qubit coherence increases, there is a trend towards more thorough and careful filtering. The increased losses of filtering and weaker qubit-drive line couplings together result in longer gate times at a given drive strength. However, achieving high gate fidelity requires we maintain or increase the ratio of qubit lifetime to gate time and so we attempt to compensate by increasing drive strength, which in turn increases heating of the cryostat. Heating of filter elements and drive lines13 can degrade the qubit by creating an excess thermal population at the qubit transition or higher frequencies (for example, at the superconducting gap) and/or heating the entire cryostat by exceeding the cooling capacity of the dilution refrigerator14. Moreover, the thermal time constants (in the millisecond range) are much slower than the pulses (roughly 10s of nanoseconds range) or qubit coherence times ( ~ 100 μs to 1 ms), and can produce effects which accumulate and persist across many experiments13. This situation is exacerbated by the necessity of scaling to larger quantum machines and thus increased qubit count and associated heating7.

To combat these limitations, better heat handling of each component, especially the attenuators on the control lines, has proven useful11,13. Another solution is to break the symmetry between input control drives and out-going qubit photon decay in the power domain using a non-linear filter15. In this paper, we propose breaking the link between qubit coherence and driving by separating the two processes in frequency space, proposing and demonstrating a new single qubit control scheme based on parametric driving, which we term subharmonic driving.

In subharmonic driving we operate a transmon, a commonly used fixed-frequency qubit, by parametrically driving it at one third of its \(| g\left.\right\rangle \leftrightarrow | e\left.\right\rangle\) transition frequency. Similar controlling methods are widely used in other systems, such as parametric amplification16,17 and parametric qubit-cavity18, multi-cavity19,20,21 and multi-qubit gates22,23. In each of these scenarios, far off-resonant terms in the Hamiltonian are utilized, consuming pump photons to produce effective lower-order interaction Hamiltonians which need not satisfy energy conservation. The benefits of parametric driving include strong interactions and high on/off ratios; the use of reflective filters to protect mode frequencies while allowing strong driving is also well established21,24,25.

The dominant nonlinear term in a transmon, the self-Kerr, is generated from the fourth order term of the Josephson junction’s cosinusoidal potential, with magnitude typically ranging from -150 to -250 MHz26. We pick the 4th order term \({\hat{q}}^{{{\dagger}} }\hat{q}\hat{q}\hat{q}+h.c.\), where \({\hat{q}}^{{{\dagger}} }\) is the qubit creation operator, and parametrically drive the qubit at near one third of the qubit transition frequency. Under these drive conditions, the chosen term annihilates three drive photons to create one qubit photon. The effect of the drive is described by the effective Hamiltonian \(\sim {\eta }^{3}{\hat{q}}^{{{\dagger}} }+h.c.\), where η is the dimensionless amplitude of the coherent drive. We note that the potential energy contains many other terms; however, these terms are suppressed as they are fast-rotating as can be seen by applying the rotating wave approximation (RWA). We emphasize that the term we use is both ubiquitous and of very similar strength in every transmon qubit. This scheme can also be adapted to other qubits and systems by choosing an appropriate source of nonlinearity, for instance, 3rd or 5th order terms in qubits with asymmetric Josephson elements27, and thus can be applied widely in superconducting circuits.

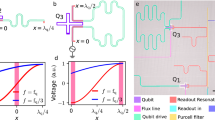

The proposed control scheme has two main advantages. The first advantage is that the drive frequency is separated from the qubit transition frequency. It allows us to suppress a primary relaxation channel in the system without affecting the ability to control the qubit by engineering the impedance at two widely separated frequencies. To this end, we placed a reflective low-pass filter (LPF) with low absorption (S11(ωd)=0.2 dB) and good isolation in the stop band (S21(ωq)=61 dB) at the qubit drive port, as shown in Fig. 1a. This suppresses qubit photon leakage to the environment through resonant decay while allowing low-frequency drive photons to pass freely. Therefore, the drive port can be more strongly coupled to the qubit for fast control without increasing the qubit’s direct relaxation rate. The second advantage of subharmonic control is that the Rabi rate is proportional to the drive amplitude cubed because it is a three-photon driving process, which allows us to rapidly improve qubit gate speed with only a moderate increase of drive power.

a A transmon qubit (at left in blue) and a λ/2 resonator for readout (at right in orange) are supported on a sapphire chip inside an aluminum tube. A low-pass filter (in green) is placed at the qubit drive port to suppress qubit photon leakage to the environment while allowing fast single qubit control at low frequencies. b The frequency distribution of the subharmonic drive ωd (red), qubit frequency ωq (blue), and the readout resonator frequency \({\omega }_{{{{\rm{res}}}}}\) (orange). Only the subharmonic drive is within the pass-band of the LPF (green). The dashed, shifted peak of ωq represents the ac-Stark effect during the subharmonic drive. c The energy level diagram of subharmonic driving. The ac-Stark effect induced by subharmonic drive creates a detuning δd between the qubit’s un-driven and driven frames. Flat-top pulses are used to control the qubit state.

In this paper, we experimentally demonstrate the concept of single qubit, subharmonic control and achieve gates as fast as 37.4 ns with gate fidelities up to 99.91% on a typical, unoptimized transmon qubit. We also present calculations which address two key questions about practical implementation of subharmonic gates. First, we present a theoretical study of the effects of the low frequency lossy environment on the qubit’s coherence, finding that this coupling offers a negligible decay channel even for very strong couplings. Second, based on both theoretical calculations and measured parameters of our system, we find that the combination of low loss at base with realistic filter losses should allow high fidelity qubit gates with heating lower than conventional direct qubit drives.

Results

Subharmonic driving theory

The displaced Hamiltonian of a transmon under an off-resonant drive \(\varepsilon (t)\cos ({\omega }_{d}t)\) can be written as

where η = iβ(ωd)ε(t) is the dimensionless drive strength, and \(\beta=2{\omega }_{d}/[{({\omega }_{q}-\alpha )}^{2}-{\omega }_{d}^{2}]\) (see Supplement Sec. I A). Expanding the Hamiltonian \({\hat{H}}^{D}\), we find numerous 4th-order terms corresponding to different parametric processes of the transmon, which can be individually activated by driving at the correct frequencies. For example, driving the term \(4\eta {e}^{i{\omega }_{d}t}\hat{q}\hat{q}\hat{q}+h.c.\) at 3(ωq + α) activates the three-photon transition \(| g\left.\right\rangle \leftrightarrow | h\left.\right\rangle\) (where \(| h\left.\right\rangle\) is the third excited state), while the two-photon transition \(| g\left.\right\rangle \leftrightarrow | f\left.\right\rangle\), commonly seen in transmon spectroscopy (usually termed gf/2), can be activated by driving the term \(6{({\eta }^{*}{e}^{i{\omega }_{d}t})}^{2}\hat{q}\hat{q}+h.c.\) near (2ωq + α)/2. For subharmonic driving, the term we are interested in is \(4{({\eta }^{*}{e}^{i{\omega }_{d}t})}^{3}\hat{q}+h.c.\) Moving to the rotating frame at 3ωd ≈ ωq and performing the RWA, we acquire the desired single qubit Rabi drive term, as well as a term proportional to (ηη*)q†q, which represents the ac-Stark effect during subharmonic drive.

In the end, the Hamiltonian has the form:

with the drive detuning \(\delta={\omega }_{d}-\frac{1}{3}{\omega }_{q}\). Eq. (2) shows two important properties of subharmonic driving: the Rabi rate of the process Ω is proportional to ∣η∣3, and the ac-Stark shift Δω during the subharmonic drive is proportional to ∣η∣2. The ac-Stark effect also adds a drive-dependent phase on the qubit when performing a gate, which needs to be considered and calibrated in all experiments, as the qubit frequency changes in response to the amplitude of the drive.

One potential concern about subharmonic driving is qubit photon decay through the drive line at low frequencies via multi-photon processes, which could limit coherence when we couple the transmon and drive line very strongly. We perform a detailed calculation in the Supplement Sec. I G and summarize key results here. For a transmon qubit coupled to a low-frequency lossy environment, the system-bath coupling strength is

where Cc is the coupling capacitance between the qubit and the transmission line, Cr is the capacitance of the qubit, c is the characteristic capacitance of the transmission line, and v is the speed of light in the transmission line28. In our case, we put a cut-off (filter) function Θ(ν) to suppress the high-frequency system-bath coupling. Specifically, the filter function is modeled as

where ωq/3 + ϑ is the bandwidth of the filter pass band. The decay rate through a three photon decay process can then be written as

where γ1 = 2πλ2, λ is the system-bath coupling strength. For a transmon system with typical properties, because α and γ1 are both much smaller than ωq, the subharmonic decay rate Γ3 is orders of magnitude smaller than the decay rate through resonant decay via internal losses or residual coupling to drive ports. Therefore, Γ3 can be safely neglected even for very strong couplings.

Gate tune up and calibration

The subharmonic driving scheme was tested on a single qubit-resonator system, which had a transmon qubit and a λ/2 stripline resonator29 with parameters commonly used in the field. Specifically, a transmon qubit (ωq/2π = 4.237 GHz, α/2π = − 148.7 MHz, T1/T2R/T2E = 41/21/72 μs) and a \({\omega }_{{{{\rm{res}}}}}/2\pi=6.498\,\,{\mbox{GHz}}\,\) readout resonator were housed inside a 4 mm diameter aluminum tube. The coupling rate of the resonator is κext/2π = 1.44 MHz and the cross-Kerr between the qubit and the resonator is χ/2π = 0.77 MHz. This system was chosen to represent a general transmon-cavity system without any special engineering or specific design requirements, demonstrating that the subharmonic driving scheme is widely applicable to transmon-based quantum processors.

To better understand subharmonic driving, we first performed Rabi experiments, sweeping the drive frequency and amplitude on the qubit to observe its population oscillating between two states. Figure 2 shows qubit response vs. drive frequency, amplitude, and initial state. The pulse used here was a 100 ns flat-top pulse with smoothed edges (see Supplement Sec. I B). Preparing the qubit in the states \(| g\left.\right\rangle\), \(| e\left.\right\rangle\) and \(| f\left.\right\rangle\), we see the four-wave mixing ge/3, ef/3 and fh/3 processes, respectively, by activating the term q†qqq + h. c. . They are separated by a frequency of α/3. Furthermore, the 8-wave mixing processes gf/6 and eh/6 can be observed, with the term q†q†q6 + h. c. activated. The gf/6 process is the subharmonic correspondence of the gf/2 peak that is often seen in qubit spectroscopy.

a-c prepare the transmon’s initial state in \(| g\left.\right\rangle\), \(| e\left.\right\rangle\), and \(| f\left.\right\rangle\) respectively. Multiple transitions can be activated by sweeping drive amplitude and frequency. The numerator and denominator of labels mean the levels and the number of drive photon involved in the transitions. The drive voltage Vp represents the peak amplitude of a pulse at the base stage of the dilution refrigerator.

We also observe a state-dependent upper boundary above which the coherent oscillations disappear and the transmon population moves to higher excited states. Such a boundary puts a maximum speed limit of our subharmonic gates, but is beyond the scope of this paper and the subject of a separate investigation30. Within this upper boundary, all of these parametric processes can be used to perform qubit controls without appreciable degradation of the qubit’s coherence. In this work, we focus on the ge/3 process and use it to build fast single-qubit gates.

Our next step is driving the qubit with fixed power (and hence ac-Stark shift) and variable pulse duration at a given pulse amplitude to find the Rabi rate and frequency. As shown in Fig. 3a, the subharmonic Rabi oscillation versus time shows a chevron pattern similar to the pattern observed using a resonant drive. By fitting the data, we extract both the ac-Stark shift induced by the off-resonant drive on the qubit and the Rabi rate at the given drive strength.

a A Rabi experiment for subharmonic driving of the qubit as a function of pulse duration and drive frequency at fixed drive amplitude of 6.47 × 10−5 mV/MHz. At this amplitude, the Rabi rate is 2π × 13.55 MHz and the drive-induced qubit ac-Stark shift is 2π × -81.25 MHz, equivalent to 0.55 times of the transmon anharmonicity α. b Rabi rate and qubit ac-Stark shift vs. drive amplitude. The Rabi rate (red squares) is proportional to drive amplitude cubed. The ac-Stark shift (blue stars) is proportional to drive amplitude squared. A single fit function describes both sets of data with only one free parameter, the scaling factor k converting pulse amplitude βVp to the effective driving strength η.

The experiment was then repeated with other pulse amplitudes. The drive amplitude in millivolts is the pulse peak amplitude at the base stage of the dilution refrigerator. The microwave configuration on the input line is shown in Supplementary Fig. 11. The method of calibrating the pulse amplitude in the base stage is discussed in the Supplement Sec. II B. After calibration, we assume that the voltage is linearly proportional to the drive strength η on the qubit. As shown in Fig. 3b, with a drive amplitude of 1.67 × 10−5 mV/MHz, the slowest Rabi rate was only 2π × 0.27 MHz. When the drive amplitude was increased by 7.1 times to 1.11 × 10−4 mV/MHz, the Rabi rate reached 2π × 68.04 MHz, which increased by around 250 times. The qubit also experiences an ac-Stark shift around 1.6 times of its anharmonicity. The Rabi rate Ω(Vd) and the ac-Stark shift Δω(Vd) as a function of drive strength Vd are fitted simultaneously with a single free parameter k, which relates the room temperature and cryogenic drive voltages:

where the transmon self-Kerr α and β are known parameters measured using qubit spectroscopy. In Fig. 3b, the ac-Stark shift is normalized by the transmon anharmonicity α and the data fit well with the fitting function, with k = 2π × 1.25 × 103 MHz/mV. The data point with the highest drive amplitude is plotted but not used in the fitting. In general, the details of the qubit response at the very strongest drives, here with a Rabi rate approaching the qubit anharmonicity, is subject to a number of complicating factors and requires further investigation in future work.

These Rabi experiments demonstrate subharmonic driving can perform fast controls on quite standard transmon qubits. To use this scheme practically, we also need to develop a procedure for calibrating a high-fidelity single-qubit gate with well-defined parameters. For on-resonance driving, both deterministic tune-up31 and randomized benchmarking procedures have been well developed5. However, these procedures cannot be directly applied to subharmonic gates tune-up without first addressing the issue of drive-induced frequency shift. When the generator frame and the qubit frame are rotating at different speeds, phase tracking is required. In the case of subharmonic driving, as shown in Eq. (2) and Fig. 3, the qubit frequency is shifted. Therefore, the qubit frame rotates at a different speed relative to the generator frame during the drive and effectively adds a phase shift φi to the qubit. Such phase shift can be calculated as

where ti and ti+1 are the starting time and ending times of gate i. One way to correct the phase shift is by applying a virtual-Z gate after the pulse32. Alternately, we can apply a time-varying frequency modulation to the pulse, which changes the instantaneous frequency of the pulse based on the qubit’s ac-Stark shift. Ideally, a frequency-modulated pulse can always satisfy 3ωd(t) = ωq + Δω(t), which makes phase tracking unnecessary. However, in experiments, we found that phase tracking is usually still required to remove residual errors over many pulses.

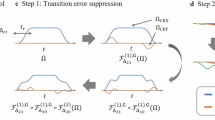

Additionally, applying a fixed-frequency pulse with large ac-Stark shifts can cause direct excitation to non-computational states. For example, as shown in Fig. 4a, when the qubit is prepared in the ground state and driven at fixed frequency ωd = ωq/3 + δ, the gf/6 process can be activated during the ramp up/down period of a pulse if the detune δ is larger than one sixth of the transmon anharmonicity α. By following the transmon frequency during a drive, chirped pulses avoid directly crossing and activating unwanted processes, and thus reduce leakage. Figure 4b shows the Rabi experiment with frequency modulation using a quadratic model Δω = 2α∣η∣2, as predicted by the 4th-order truncated Hamiltonian. The ac-Stark shift of the transmon is mostly removed. The remaining distortion of the Rabi fringes arises primarily from imperfect pulse envelopes and the mismatch of instantaneous frequency and drive amplitude. We can reduce the distortion by performing pulse envelope correction and including higher-order Hamiltonian terms to obtain a more accurate modulation model.

a With the drive frequency following the ac-Stark shift of the transmon (red trace), a frequency chirped pulse is always resonant with the subharmonic process. Compared with fixed-frequency drive (blue trace), it avoids directly crossing other processes. b A power Rabi experiment with frequency chirping. The frequency axis here is the initial frequency of the pulse.

To benchmark our subharmonic single qubit gates, we choose the usual π and π/2 rotation over the X, Y, and Z axes as the basic operations. Rotation about the Z axis is realized through VZ gate, which has no cost and fidelity close to one32. For the X and Y gates, the drive amplitude needs to be balanced between errors due to qubit decay, leakage to non-computational states, hardware limitations, and other factors. Because of control hardware limitations, we found best results when performing rotations of π and π/2 with 50.9 ns and 37.4 ns long smoothed flat-top pulses. The details of a gate sequence-based calibration procedure that calibrates each parameter are explained in Supplement Sec. II C.

Randomized benchmarking and interleaved randomized benchmarking33,34,35 are used to calibrate the average fidelity of all Clifford gates and the fidelity of specific gates, including X, \(\sqrt{X}\), Y and \(\sqrt{Y}\) gates. The fidelity of the interleaved gate is calculated using35,

As shown in Fig. 5, the average Clifford gate fidelity is 99.604(9)%, and the gate fidelities of X, \(\sqrt{X}\), Y, and \(\sqrt{Y}\) are 99.79(1)%, 99.91(1)%, 99.76(2)%, 99.91(1)% respectively. To maintain this fidelity, a stable environment for room-temperature control hardware is crucial. The subharmonic gates are three times more sensitive to the amplitude and phase drift than resonant gates, because of the Rabi rate’s cubic dependence on drive amplitude. To reduce pulse parameter drifting, we stabilized the room-temperature equipment’s environment by sealing it in a PID controlled temperature stabilizing box, which is discussed in detail in Methods and Supplement Sec. II D.

Gate fidelities are calibrated with randomized and interleaved randomized benchmarking. The red trace shows the average fidelity of Clifford gates using subharmonic driving. The green and blue traces show the average fidelity of random sequences with a specific interleaved Clifford gate (X and \(\sqrt{X}\) here), respectively, and are used to extract the fidelities of individual gates.

Potential for reduced heating and fast subharmonic gates

We have shown experimentally that a subharmonic drive can perform fast and high-fidelity single qubit control, and found theoretically that strong couplings to low-frequencies are not associated with enhanced qubit losses. Of far greater concern is the behavior of the low-pass filter, which protects the qubit. The filter’s figures of merit are the absorptive losses in reflection and insertion loss at the qubit’s transition frequency (which protect the qubit from the environment noise and Purcell decay into the filter) and the losses in transmission at the drive frequency (which contribute to cryostat heating).

Measurements of the filter used in this experiment (Mini-circuits ZLSS-A2R8G-S+) at room temperature show that the impedance is 6.66 − 123.3i Ω at the qubit g − e frequency ωq. By performing the finite element simulation using Ansys HFSS, we estimate that the filter reduces the decay rate through the qubit port at ωq from κ(ωq)/2π = 0.55 kHz to κLPF(ωq)/2π = 18.2 Hz. The subharmonic decay rate κsub is much smaller than κLPF and can be neglected. To verify the performance of the LPF, we measured three qubits with lowpass filters on the qubit drive port and one qubit without the filter. These four qubits were fabricated on the same wafer, went through the same fabrication processes and had similar design. Therefore, their coherence times should be similar. Although the improvement of the qubit coherence times are not as good as theory predicts, we still see a clear improvement (see Supplement Sec. II A). The discrepancy is likely due to the loss and electrical length of the cable between the qubit and the filter. A low loss on-chip filter36,37 could further reduce photon loss and improve filter protection.

Subharmonic driving also offers new possibilities to address cryostat and component heating. It is a common practice to attenuate the input signal by 60 dB or higher to reduce thermal noise to a very small residual photon occupancy in the drive lines at the readout resonator and qubit frequencies38,39.

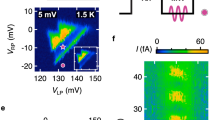

These attenuators put a heat load on the refrigerator and can become a limitation for near-term quantum machines. Because the heat load is usually limited by the cooling power at the base stage of the dilution refrigerator, we focus on the drive line configuration at the base stage. Figure 6 shows an estimate of the heat dissipated at the base stage of a dilution refrigerator with various drive line configurations. Because the drive power is also related to the coupling strength of the drive port to the qubit, the coupling strength is designed to limit the qubit lifetime to T1 = 1 ms, which is estimated using finite element circuit modeling and filter data measured at room temperature. As shown in Fig. 6, with a conventional high-attenuation drive line, approximately -30 dBm of power is dissipated at the base stage to achieve a π-pulse time of 10 ns. The current limited cooling capacity of our dilution refrigerator ( ~ 10 μW at 20 mK) allows only tens of single-qubit drives in parallel before significantly heating the base stage. Moreover, the attenuator itself as a dissipative element can be heated and generate broadband thermal radiation in turn. Commercial attenuators have been shown to cool much slower than the typical experiment repetition rates, creating further complications13. It would be advantageous to simply remove these components.

The heat dissipated at base stage vs. Rabi rate Ω with different input line configurations and driving methods is compared. Using the subharmonic drive method, the attenuators at base stage can be reduced and replaced with reflective filters. The coupling to drive lines limits qubit coherence time T1 around 1 ms. Conventional resonant drives are shown as dashed lines, subharmonic drives are shown as solid lines.

As shown in Fig. 6, we compare conventional drive lines with a line that has 20 dB base attenuation and a LPF, which is close to our experiment configuration, and a line with 3 dB attenuation and a LPF at base. The configuration with 3 dB attenuation further alleviates the heat dissipation at the base stage by completely removing attenuators from the base plate. The remaining 3 dB attenuation represents our estimate of realistic losses on components other than RF attenuators, such as coaxial cables and Eccosorb filters, which dominate over the insertion loss of the LPF. Reducing the losses at the base stage allows us to take full advantage of subharmonic driving; at a Rabi rate of 50 MHz, heat dissipation for subharmonic drive configuration with 3 dB attenuation is reduced by around 20 dB relative to the conventional drive configuration, allowing 100 times more qubits to be controlled for the same dissipated power and realistic assumptions about the drive line configuration.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have shown that subharmonic driving is a new single-qubit control scheme with fast gate speed and high fidelity. By breaking the symmetry between drive and decay of a qubit in the frequency domain, we protect the qubit from resonant relaxation and control the qubit without any need for resonant access. In addition, the cubic dependence of the gate speed on the drive strength could reduce the heat dissipated during qubit driving for appropriately designed reflective drive lines.

In the experiment single-qubit gates with fidelity of 99.9% are realized. However, higher gate fidelity can be achieved. The gate time currently used to achieve 99.9% fidelity is much slower than the maximum Rabi rate that we measured in this experiment. This is because of the pulse distortion and imprecise control of FPGA hardware, we believe gate times of 10 ns or lower are possible to achieve. In addition, DRAG correction or other pulse engineering techniques3,40,41 can be implemented to reduce gate error and improve gate speed. With moderate improvement in qubit coherence times and gate time of 10 ns, gate fidelities of 99.99% or higher are achievable, and, together with reduced cryostat heating, make subharmonic gates a compelling method for single-qubit control in future large-scale quantum computers.

Methods

Experiment setup

The metal block housing the qubit and cavity’s tube is made of Al-6061 alloy with a 4 mm diameter hollow tube and two coupling ports. One of the ports is coupled to the transmon for single qubit control. The other port is coupled to the resonator for the dispersive readout. The transmon qubit and the λ/2 stripline resonator are fabricated on a 421 μm thick sapphire substrate with around 200 nm Ta film except for the Josephson junction of the transmon, which is a Al/AlOx/Al junction.

The experiment setup is shown in the Supplementary Fig. 11. We used a low-pass filter, Mini-circuits ZLSS-A2R8G-S+, to protect the qubit and perform subharmonic drives. The sample is mounted on the base plate of the dilution refrigerator, which is operated at around 20 mK. The qubit driving pulses and readout pulses are generated by direct digital synthesis (DDS) using the Xilinx RFSoC ZCU216 based on the QICK42. For the qubit drive, before the signal is sent to the sample, a small fraction is split using a directional coupler, then sent back to the digitizer for monitoring pulse stability.

Temperature stabilization

The performance of room temperature electronics depends on their operating status and environment. For example, the gain of a power amplifier changes as environment temperature changes. In monitoring our pulse properties, we found the operating temperature, which is regularly perturbed by air-conditioning cycles in the room air, has the most significant effect on our system performance. A clear dependence on devices’ temperature can be observed, As shown in the supplement Sec. II D, While a few percents of relative variation in power and phase can often be ignored in simple one or two pulse protocols, such as T1 or T2 measurements, it is a limiting factor for high-fidelity quantum control, and it is important for building a stable quantum computer without frequent pulse calibration. Also, this is especially important for subharmonic driving, since it is three times more sensitive to the fluctuation of pulses’ magnitude and phase.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17794758.

References

Sheldon, S., Magesan, E., Chow, J. M. & Gambetta, J. M. Procedure for systematically tuning up cross-talk in the cross-resonance gate. Phys. Rev. A 93, 060302 (2016).

Mundada, P., Zhang, G., Hazard, T. & Houck, A. Suppression of qubit crosstalk in a tunable coupling superconducting circuit. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 054023 (2019).

Motzoi, F., Gambetta, J. M., Rebentrost, P. & Wilhelm, F. K. Simple pulses for elimination of leakage in weakly nonlinear qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 110501 (2009).

Barends, R. et al. Superconducting quantum circuits at the surface code threshold for fault tolerance. Nature 508, 500–503 (2014).

Kelly, J. et al. Optimal quantum control using randomized benchmarking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 240504 (2014).

Sheldon, S. et al. Characterizing errors on qubit operations via iterative randomized benchmarking. Phys. Rev. A 93, 012301 (2016).

Boixo, S. et al. Characterizing quantum supremacy in near-term devices. Nat. Phys. 14, 595–600 (2018).

Kjaergaard, M. et al. Superconducting qubits: Current state of play. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 11, 369–395 (2020).

Place, A. P. et al. New material platform for superconducting transmon qubits with coherence times exceeding 0.3 milliseconds. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–6 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. Towards practical quantum computers: transmon qubit with a lifetime approaching 0.5 milliseconds. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 3 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Cavity attenuators for superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 014031 (2019).

Serniak, K. et al. Direct dispersive monitoring of charge parity in offset-charge-sensitive transmons. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 014052 (2019).

Yeh, J.-H., LeFebvre, J., Premaratne, S., Wellstood, F. & Palmer, B. Microwave attenuators for use with quantum devices below 100 mk. J. Appl. Phys. 121, 224501 (2017).

Krinner, S. et al. Engineering cryogenic setups for 100-qubit scale superconducting circuit systems. EPJ Quantum Technol. 6, 2 (2019).

Kono, S. et al. Breaking the trade-off between fast control and long lifetime of a superconducting qubit. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–6 (2020).

Clerk, A. A., Devoret, M. H., Girvin, S. M., Marquardt, F. & Schoelkopf, R. J. Introduction to quantum noise, measurement, and amplification. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1155 (2010).

Roy, A. & Devoret, M. Introduction to parametric amplification of quantum signals with josephson circuits. Comptes Rendus Phys. 17, 740–755 (2016).

Narla, A. et al. Robust concurrent remote entanglement between two superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. X 6, 031036 (2016).

Sirois, A. J. et al. Coherent-state storage and retrieval between superconducting cavities using parametric frequency conversion. Appl. Phys. Lett. 106, 172603 (2015).

Axline, C. J. et al. On-demand quantum state transfer and entanglement between remote microwave cavity memories. Nat. Phys. 14, 705–710 (2018).

Zhou, C. et al. Realizing all-to-all couplings among detachable quantum modules using a microwave quantum state router. npj Quantum Inf. 9, 54 (2023).

Niskanen, A. et al. Quantum coherent tunable coupling of superconducting qubits. Science 316, 723–726 (2007).

McKay, D. C. et al. Universal gate for fixed-frequency qubits via a tunable bus. Phys. Rev. Appl. 6, 064007 (2016).

Axline, C. et al. An architecture for integrating planar and 3d cqed devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 042601 (2016).

Rehammar, R. & Gasparinetti, S. Low-pass filter with ultra-wide stopband for quantum computing applications. ArXiv abs/2205.03941 (2022).

Koch, J. et al. Charge-insensitive qubit design derived from the cooper pair box. Phys. Rev. A 76, 042319 (2007).

Noguchi, A. et al. Fast parametric two-qubit gates with suppressed residual interaction using the second-order nonlinearity of a cubic transmon. Phys. Rev. A 102, 062408 (2020).

Blais, A., Grimsmo, A. L., Girvin, S. M. & Wallraff, A. Circuit quantum electrodynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 93, 025005 (2021).

Wang, C. et al. A schrödinger cat living in two boxes. Science 352, 1087–1091 (2016).

Xia, M. et al. Exceeding the parametric drive strength threshold in nonlinear circuits. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.03456 (2025).

Reed, M. D.Entanglement and Quantum Error Correction with Superconducting Qubits. Ph.D. thesis, Yale University (2013).

McKay, D. C., Wood, C. J., Sheldon, S., Chow, J. M. & Gambetta, J. M. Efficient z gates for quantum computing. Phys. Rev. A 96, 022330 (2017).

Knill, E. et al. Randomized benchmarking of quantum gates. Phys. Rev. A—At., Mol., Optical Phys. 77, 012307 (2008).

Magesan, E., Gambetta, J. M. & Emerson, J. Characterizing quantum gates via randomized benchmarking. Phys. Rev. A—At., Mol., Optical Phys. 85, 042311 (2012).

Magesan, E. et al. Efficient measurement of quantum gate error by interleaved randomized benchmarking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 080505 (2012).

Park, S. H. et al. Characterization of broadband purcell filters with compact footprint for fast multiplexed superconducting qubit readout. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124 (2024).

Sah, A., Kundu, S., Suominen, H., Chen, Q. & Möttönen, M. Decay-protected superconducting qubit with fast control enabled by integrated on-chip filters. Commun. Phys. 7, 227 (2024).

Wang, C. et al. Towards practical quantum computers: Transmon qubit with a lifetime approaching 0.5 milliseconds. npj Quantum Inf. 8, 3 (2022).

Chakram, S. et al. Seamless high-q microwave cavities for multimode circuit quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 107701 (2021).

Khaneja, N., Reiss, T., Kehlet, C., Schulte-Herbrüggen, T. & Glaser, S. J. Optimal control of coupled spin dynamics: design of nmr pulse sequences by gradient ascent algorithms. J. Magn. Reson. 172, 296–305 (2005).

Caneva, T., Calarco, T. & Montangero, S. Chopped random-basis quantum optimization. Phys. Rev. A—At., Mol., Optical Phys. 84, 022326 (2011).

Stefanazzi, L. et al. The qick (quantum instrumentation control kit): Readout and control for qubits and detectors. Review of Scientific Instruments 93 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research, including funding for M.X., C.Z. and C.L. was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, National Quantum Information Science Research Centers, the Co-design Center for Quantum Advantage (C2QA) under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. Support was also provided by the Air Force Office of Strategic Research under award FA9550-15-1-0015, and the National Science Foundation PIRE HYBRID program under contract 1743717.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.J.H. conceived and supervised the project with help from D.P. on theoretical analysis. M.X., C.Z., X.C., P.L. and M.M. acquired data for the project; P.L. contributed important software tools for randomized benchmarking, while B.M. built and tested with M.X. temperature stabilization hardware for the control electronics. P.J.P. designed and fabricated the samples. C.Z. and D.G. contributed to theoretical calculations of the subharmonic gate, while C.L. performed the study of multi-photon decay channels. M.X. led final data acquisition and the gate speed/heating analysis. M.X. and M.J.H. drafted the manuscript, to which all authors contributed.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.J.H. receives consulting fees and/or holds equity in Quantum Circuits, Inc. P.L. has financial interest in Quantum Circuits, Inc. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shingo Kono, and the other, anonymous, reviewer for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, M., Zhou, C., Liu, C. et al. Fast superconducting qubit control with subharmonic drives. Nat Commun 17, 1024 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67766-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67766-6