Abstract

The initial evolution of warning coloration (“aposematism”) within a cryptic population of defended prey presents an evolutionary paradox. A recent phylogenetic analysis of amphibia suggests a new solution: prey that combine cryptic colours with conspicuous patches on concealed body parts (“hidden signallers”), may have mediated the transition of species from camouflage to aposematism. Here, we focus on the colour-diverse snake family Elapidae and test whether species with hidden colours could also serve as an intermediate stage in the evolution of aposematism in this group. Phylogenetic comparative analysis reveals several key patterns in their anti-predator colour evolution: (i) a few major transitions influenced the overall distribution of hidden-colours, camouflage, and aposematism in the group, and (ii) aposematism evolved multiple times, with hidden coloration a common precursory state, while direct transitions from camouflage to aposematism are also observed. We also quantify associations between colour patterns and defensive behaviours that reveal ventral surfaces (i.e. hidden signals). We find that venter-revealing defensive behaviours frequently co-occur with hidden colour signals. Our results suggest that aposematism can evolve through multiple routes and highlight the prevalence of co-evolution between venter-revealing defensive behaviour and anti-predator coloration in snakes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Most animals face predators at some stage in their life cycle. This has led to the evolution of a range of morphological and behavioural adaptations to avoid detection and/or deter their attack post-encounter1. In particular, many animal species have evolved camouflage, reducing their probability of detection or recognition by predators2. Conversely, some species have evolved active defences against predators such as stings or toxins and signal their unprofitability to their would-be predators through conspicuous warning signals, an association known as “aposematism”3. These warning signals can be mimicked by harmless species (Batesian mimicry)4 or copied by other defended species, thereby reducing the costs of predator education (Müllerian mimicry)5.

While conspicuous signals may serve to warn would-be predators, the initial spread of aposematic mutants from rarity is challenging to understand. The problem, first recognised by Fisher6, arises because the first conspicuous mutants would not only be more detectable than their cryptic conspecifics, but also not as readily recognised as defended. To learn the association, predators must sample the conspicuous mutant, yet in so doing, the rare mutant(s) may be driven to extinction. In spite of these challenges, aposematism has successfully evolved many times across the animal kingdom1. Several explanations as to how aposematic mutants overcome their two-fold disadvantage have been proposed. For example, some species may be able to deploy their noxious defences and survive capture by predators7. There are a variety of ways that this could occur; some insects, for example, have distasteful secretions or stings, which, combined with protective integuments, may allow them to survive taste rejection8. While resistance to handling may explain how aposematism has evolved in some taxa, it cannot provide a complete explanation because many poisonous aposematic species are soft-bodied and appear unlikely to be able to survive sampling9. Alternatively, some defences can be deployed or detected from a distance10, such as skunk spray or urticating hairs of New World theraphosid spiders11,12 but once again, not all defences are apparent before capture.

Fisher’s celebrated explanation for how aposematism evolves in these taxa was that while the individuals that are sampled die, aposematism can still be selected for if the prey have close relatives with the same anti-predator traits that benefit from any learned aversion. This kin selection13 hypothesis will be more likely to hold when relatives form aggregations, such that a predator may sample one individual but then ignore the rest of the group14. In support, many aposematic lepidoptera larvae do form aggregations15,16. However, phylogenetic analyses indicate that, in all lineages considered, conspicuous coloration likely preceded the evolution of gregariousness, suggesting that kin selection is unlikely to have contributed to the initial evolution of aposematism in these caterpillars15,17,18. Additionally, aposematism is observed in many non-gregarious taxa19, including coral snakes (Micrurus and Calliophis genera) that are highly cannibalistic outside of the breeding season and therefore unlikely to have exhibited gregarious behaviour at any point in their evolutionary history. Finally, an alternative explanation is that aposematism may evolve incrementally, with species gradually acquiring conspicuous coloration such that they may educate predators without fully abandoning crypsis, at least at first20. For this to work, predators must generalise learned avoidance of semi-conspicuous phenotypes to more readily detectable forms. A behavioural experiment using blue tits (Cyanistes caeruleus) as model predators found that prior exposure to semi-conspicuous distasteful targets did not reduce the birds’ probability of attacking more conspicuous similar-looking targets21. This led the authors to suggest that it is unlikely that aposematism evolves by gradual change.

Studies of the evolution of aposematism have typically only taken into account animal coloration that is always visible. However, many cryptic species exhibit patches of conspicuous colour on surfaces that are usually hidden and only transiently exposed during locomotion or as part of a behavioural display22,23,24. Unlike consistently visible aposematic signals, these hidden colour defences do not impose the costs of full conspicuousness during the initial stages of evolution. Their normally camouflaged appearance reduces the risk of detection, while still potentially deterring predators through post-attack displays that startle, warn, and/or facilitate avoidance learning25,26,27. This is an important distinction because, unlike rare aposematic forms, mutations causing hidden signals may provide a fitness benefit at the outset, for example, by startling a predator27. Once established, it is conceivable that species with hidden signals may function as a stepping stone, facilitating the evolution of aposematism if predators are able to generalise their learned avoidance of hidden signals to prey with permanently displayed signals.

In support of the hypothesis that species with hidden signals serve as stepping stones to species with full aposematism, a recent large-scale macroevolutionary study of transitions between different types of signaller in amphibians found that the acquisition of aposematic coloration in species was disproportionately preceded by species with hidden signals28. This evolutionary route to aposematism is likely not restricted to amphibians and may be widespread in the animal kingdom. Indeed, many aposematic species across various taxonomic groups, including fish, arthropods, and other tetrapods, have close relatives that are cryptic but possess conspicuous hidden signals27,28,29. Unfortunately, parallel analyses comparable to what was done in amphibians in many of these groups present substantial challenges. This is because the analysis requires a few conditions to be met. First, relatively complete time-calibrated molecular phylogenies are required. Gaps in the phylogeny may result in intermediate forms being missed, preventing the detection of key transitions30. In many arthropods, for example, only a small proportion of the total described species have known phylogenetic information, and many more species remain undescribed31. Second, aposematism must have evolved several times independently. If all aposematic species in a taxon form a monophyletic clade, then the transition between colour states effectively happened once, not providing sufficient statistical power to estimate transition rates32.

One taxon that appears to be an excellent model to explore the evolutionary history of anti-predator coloration and test the hidden signal stepping stone hypothesis is elapid snakes. Aposematism is widespread in this group, and chemical defence (or offence) is the ancestral condition, with only a few congeneric species having secondarily lost this trait19,33. Additionally, the phylogenetic position of most extant described species is known except for the recently described species34. Intriguingly, elapids exhibit a variety of defensive behaviours (Fig. 1). For example, hooding describes a form of defensive display in which the anterior portion of the body is raised off the ground, exposing the ventral surface and the ribs are spread, potentially increasing the perceived size of the snake. While this behaviour is best known in cobras of the genus Naja, such as the Spectacled Cobra (Naja naja), it is widespread across other elapids. In addition to hooding, there exist other venter-revealing defensive behaviours, including rolling over, defensive coiling, tail displaying, and exposing the ventral surface in response to provocation by a predator27. These defensive behaviours involve revealing the usually hidden ventral surface, which raises the question of whether there are evolutionary associations between these defensive behaviours and anti-predator coloration.

The upper panels show species that were classified as cryptic (A; Green Mamba Dendroaspis angusticeps), hidden-coloured (B; Calliophis nigrotaeniatus), and conspicuous (C; Banded Krait Bungarus fasciatus). The lower panels show examples of venter-revealing defensive behaviours such as lifting the body (D; Eastern Bandy-Bandy Vermicella annulata) or hooding (E; Black-necked Spitting Cobra Naja nigricollis). Image copyright: © Johan Marais, © Charles Francis, © Rohit Giri, © Richard D. Reams, © Michele Menegon.

Here, we have classified the anti-predator coloration of snakes in the family Elapidae (comprising approximately 400 known species from 55 genera) using a schema that recognises aposematism, crypsis, species with camouflaged dorsal surfaces and conspicuous ventral coloration that is usually hidden, as well as polymorphism in which individuals with different colour states are observed within a species. We then perform ancestral state reconstruction analysis of elapid anti-predator coloration and use discrete character evolution models to test the hidden signal stepping stone hypothesis in this taxon. We also evaluate the presence/absence of defensive behaviour in elapids using both video and pictorial documentation of their responses to human provocation. Using these data, we elucidate how this behavioural defence has coevolved with anti-predator coloration.

Results and discussion

The history of colour evolution in elapid snakes

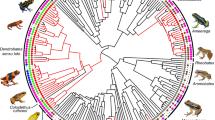

We analysed 251 species (~62% of extant species) of elapid snakes with known phylogenetic relationships and colour information. Three human classifiers experienced with snakes categorised each species based on its anti-predator coloration: either cryptic (colours and patterns that match natural backgrounds), conspicuous (high contrast coloration typically associated with aposematism such as black and white, bright blue, bright yellow, red, or orange), or hidden with cryptic coloration on the dorsal surface and conspicuous coloration on the ventral surface (see Methods for details). The three classifiers all agreed on the colour classification for 236 elapid species (94% of analysed species). For the remaining 15 species, two classifiers agreed, and we used the most common classification for each species in the main analysis. Substantial variation existed in the type of defensive coloration in elapid snakes; 34% were classified as cryptic (Cry), 40% as conspicuous (Con), 21% as hidden-coloured (Hidden), and 5% as polymorphic (here, defined narrowly when a species exhibits two or more different defensive coloration strategies) (Fig. 2B, Table S1).

A Hypothetical model that we compared when analysing anti-predator colour transitions. Absence of arrows indicates that transition rates were fixed at zero. B Proportion of each anti-predator colour type, showing high diversity in the anti-predator coloration. C Estimated transition rates in the best-supported model (ER model). Grey arrows and circles show estimated transition rates associated with polymorphic states. The number of species in each polymorphic group is limited, making inferences regarding polymorphic state transitions relatively weak. Con: Conspicuous; Cry: Cryptic; Hidden: Hidden-coloured; Poly: Polymorphic species.

We generated six hypothetical models with different constraints on transition pathways or transition rate estimation (see “Methods” for details). We initially considered seven states in total, comprising three major colour states and four polymorphic states. However, our hypothetical models were generated using only the three monomorphic states because the small number of species in each polymorphic state limited reliable estimation of transition rates (see “Methods” for details). Among the competing six models (Fig. 2A), the Equal rates (ER) model, in which a single rate governs all transitional pathways, was the most strongly supported (64% support; Table 1; full transition rates among seven different states, including those for polymorphic states, can be found in Table S2), demonstrating that transitions of species between the three colour states occurred at similar rates. Stochastic character mapping results aligned well with the transition rate results in that the transitions among different strategies have occurred in similar frequencies (Fig. 3C). However, although the estimated rates were similar, the historical frequency of transitions from conspicuous to cryptic colour was considerably lower than that of other transitions, which is consistent with our analysis of the most likely transitional history for each species (Fig. 3D). This indicates that such transitions have rarely occurred in the history of elapid snake anti-predator coloration evolution, yet the comparable rate estimates suggest that whenever they do occur, they proceed just as quickly as other types of transitions. We mainly discuss the results of the ER model and the ancestral states it estimated, but we also include results from the second-best model, the Symmetrical (SYM) model (15% support) in Fig. S1.

A Reconstructed ancestral states of the family Elapidae and (B) including sister clades. C Results of stochastic character mapping, showing the posterior distribution of changes between each colour state. The ranges highlighted by “HPD” represent the 95% highest posterior density (HPD) interval. D Number of extant species following each historical transitional route. Image copyrights for (A) are provided in Table S5. Con: Conspicuous; Cry: Cryptic; Hidden: Hidden-coloured; Poly: Polymorphic species.

Marginal and joint ancestral character reconstruction results matched 96% of cases in the most likely ancestral state for each node. Both the joint and marginal results suggest that the hidden colour state is the most likely ancestral state of elapid snakes (30% probability in the marginal ancestral character reconstruction when all seven states were considered), but there is also some support for the conspicuous (19%) and conspicuous/hidden polymorphic (19%) states (Fig. S2). The ancestral character reconstruction results (Fig. 3A) provide insights into several major patterns of colour evolution history, which we now discuss.

First, ancestral hidden colours have been retained in several lineages, including those in the Naja, Sinomicrurus, and Calliophis genera. Second, a few major transitions largely determined the overall distribution of crypsis and conspicuousness (Fig. 3D): (i) a single transition from hidden colours to conspicuousness affected the prevalence of aposematism in the species-rich Micrurus genus, and (ii) a transition from hidden colours to cryptic colours at the basal node (the common ancestors from the Laticauda to the Hydrophis genera in Fig. 3A) influenced the prevalence of crypsis across descendant lineages. As a consequence, the majority of elapid species obtained their current anti-predator colour type by either no or a single transition event from the common ancestor (Fig. 3D). Third, conspicuous coloration evolved at least 18 times independently. The transition to conspicuous colour occurred in various lineages through one of two pathways: (i) ancestral hidden colours evolved to conspicuous colours or (ii) ancestral hidden colours evolved to cryptic colours, then conspicuous colour subsequently evolved (Fig. 3D). Fourth, crypsis evolved mostly from hidden colour states, mostly governed by a single transition at the basal node as explained above, with only a few exceptions that evolved a more complex route involving conspicuous colours (Fig. 3D). Once crypsis had evolved, multiple subsequent pathways emerged: most remained cryptic, while the rest evolved to either hidden or conspicuous colours. Fifth, the polymorphic states evolved multiple times independently in the phylogeny.

Smaller-scale transitional patterns in recently diverged lineages are lineage-specific, indicating no consistent trends among the lineages, as suggested by the relatively strong support for the equal-rate model. While a previous study on amphibians revealed that hidden colours served primarily as an intermediary stage in the transition from camouflage to aposematism28, when viewed within elapid snakes alone, the same pattern did not emerge; when the transition from crypsis to hidden colours occurred, the hidden colours remained in the extant lineages without further evolving to aposematism. However, this pattern could arise because the hidden colour state is the most likely ancestral state of elapid snakes, unlike amphibians, in which camouflage is the most likely ancestral state. We therefore explored the possibility that ancestors of the elapid snakes, such as common ancestors of Elapidae and sister clades (a multi-family clade including Pseudoxyrhophiidae, Psammophiidae, Lamprophiidae, Atractaspidadae, Cyclocoridae, and Buhoma sp), exhibited camouflage. Ancestral reconstruction incorporating 151 species from sister clades showed that elapid snakes likely diverged from cryptic ancestors (86% support; Figs. 3B, S3 for marginal reconstruction results; images of the sister clades were classified by KLH using the same criterion described in the “methods”). This suggests that stepwise evolution from crypsis to conspicuousness via hidden coloured states also occurred in snakes. However, unlike amphibians, where these transitional patterns appeared multiple times in various lineages, this stepwise evolution in elapid snakes (and relatives) is explained by a single ancestral transition from camouflage to the hidden colour state at a deep node. A more comprehensive examination of other snake families is warranted to confirm the prevalence and generality of this stepwise-evolution route and to assess its role in the evolution of aposematism in snakes.

The direct transitions of camouflaged species to species with conspicuous signals may be explained in part by the prevalence of Batesian and Müllerian mimicry in elapid snakes; thus, while it is challenging to understand how the novel conspicuous mutants of cryptic prey initially spread from rarity35, if one taxon first acquires aposematism through the hidden signal route, then new conspicuous mutants of other species who resemble this well-established warning signal may be recognised as unprofitable to attack at the outset. Indeed, the conspicuous coloration of non-venomous Emydocephalus species, which are Batesian mimics of venomous sea snakes like Aipysurus, Hydrophis, and Laticauda spp.36, likely evolved from cryptic ancestors, suggesting that direct transitions from crypsis to conspicuous forms can occur through mimicry. Additionally, unlike amphibians in which no direct transition from crypsis to aposematism has been observed28, snakes possess hard keratinous scales compared to the relatively delicate skin of amphibians, which may allow them to better survive handling by predators. Likewise, the chemical defence of elapids involves venom that can be injected, rather than poison that must be ingested to take effect, further suggesting that elapids may be better able to survive sampling attempts than amphibians.

While these results provide insight into the evolutionary pathways through which lineages acquire aposematism, they do not explain why some lineages evolve this trait while others retain ancestral hidden signals. Indeed, in certain ecological contexts, hidden signalling may be an optimal strategy—allowing a snake to remain concealed from its prey while still being capable of signalling to predators when necessary. A recent phylogenetic study found that aposematism is more likely to evolve in elapid species that feed on other snakes37. Given that many snakes exhibit limited colour discrimination abilities, this may reduce the need to remain cryptic38. Under such conditions, there may be an advantage to signal their defences constantly to reduce the risk of initial attacks by their own predators. For example, if a surprise predatory attack leaves no chance for the snake to reveal its hidden signals, it may be costly to have cryptic dorsal coloration. This may happen in sea snakes such as Laticauda sp., where surprise strikes of potential predators, such as ospreys or sharks, often leave no chance for the snake to show hidden signals.

We conducted additional analyses to ensure robustness of our conclusions against (i) uncertainty in the phylogeny’s topology and node age, and (ii) uncertainty in colour classification. To examine how this uncertainty affects our results, we repeated the analysis using 100 randomly selected trees sampled from the posterior distribution of the supertree. The ER model remained the best-supported model in 63 trees, while the SYM model, the second-best, was supported in 31 trees. We also re-analysed our data using a dataset that removed 15 species with classification disagreements; the ER model still remained the best-supported model (Table S3). Additionally, we excluded all polymorphic species and re-analysed the data to mitigate the effects of species-poor states on major colour transition patterns. The ER model continued to be the best-supported model (Table S4). The ancestral character reconstruction results suggest that all supplementary analyses exhibit transitional patterns consistent with the main findings (Figs. S4, 5). These supplementary analyses confirm the robustness of the observed transitional patterns.

The evolutionary patterns of venter-revealing defensive behaviours

We analysed behaviours of 180 species for which both colour and behavioural data were available. Venter-revealing defensive behaviours were classified into one of three categories for each species: no behavioural display evident, presence of hooding behaviour, or other venter-revealing defensive behaviours (such as rolling over onto the back or lifting the tail to reveal the ventral surface) that are not hooding. A simple frequency comparison revealed strong evidence of an association between the colour group and the frequency of defensive behaviours (Chi-square test of independence; χ24 = 60, P < 0.001; Fig. 4B). Venter-revealing defensive displays (i.e. summed frequency of hooding and non-hooding defensive behaviours) are most common in the Hidden group (80%), followed by the Con (43%) and Cry (20%) groups. Specifically, hooding behaviour occurred more frequently in species with hidden colours than in other colour groups, and non-hooding defensive displays were similarly common in species with hidden and conspicuous colours, but none was found in cryptic species (Fig. 4B). While a previous study suggests that conspicuous colours are not associated with aggressive behaviours in snakes39, our results imply that defensive behaviours, particularly those that reveal the ventral surfaces, are more frequently found in species with both hidden and conspicuous colours in snakes. Ancestral character states for the colour dataset are described above; thus, our discussion here primarily focuses on defensive behaviour results.

A Estimated transition rate from the best-supported model for defensive behaviour analysis. The arrow thickness correlates with the estimated transition rate. B Frequency of each defensive behaviour associated with each anti-predator coloration. C Reconstructed ancestral states for colours (left) and behaviours (right).

Both the discrete character evolution model and the stochastic character mapping suggest that the hooding and non-hooding displays have evolved independently, each arising multiple times in different clades, with no transitions between the two display types (Table 2, Figs. 4, S6 for the model description, Fig. S7 for marginal ancestral character results, Fig. S8 for stochastic character mapping results); we found no evidence of any transitions between these two defensive behaviours. The type of defensive behaviours was conserved within each genus; most species in the Naja, Pseudonaja, Pseudechis, and Austrelaps genera exhibit only the hooding behaviour, if any. In contrast, species in Micrurus, Sinomicrurus, Calliophis, and some species in Suta, Vermicella, and Hydrophis exhibit the non-hooding defensive behaviours.

Both types of defensive behaviours have multiple independent origins (see Fig. 4C). First, hooding behaviour evolved at least six times. Among the six identified instances where hooding behaviour was acquired, two transitions occurred in ancestors with hidden colours, and four in ancestors with cryptic colours. After acquiring hooding behaviour, this behaviour was lost in some cryptic lineages, such as those in the genera Pseudechis and Pseudonaja, but was rarely lost in lineages with hidden colours, such as in the Naja genus. Once hooding behaviour evolved in cryptic lineages, many descendants subsequently developed hidden colours, retaining the hooding behaviour. This suggests two major evolutionary pathways for the correlated evolution of hooding behaviour and hidden colours: (i) hooding behaviour initially evolved in some cryptic lineages, followed by the subsequent evolution of hidden colours, and (ii) hooding behaviour evolved in species that already possessed hidden colours (the ancestral state of elapid snakes) and was retained within the lineage.

Non-hooding defensive displays seem to be the most likely ancestral trait of elapid snakes (Fig. 4C, 97% support). This ancestral state has been retained in many genera, such as Micrurus, Sinomicrurus, and Calliophis, with some species losing the defensive behaviour, primarily in aposematic species. Apart from this single ancestral effect, defensive behaviours have evolved independently multiple times, mostly in recently diverged lineages. Notably, these non-hooding defensive behaviours have evolved in either hidden-coloured or conspicuously-coloured lineages, but not in cryptically-coloured lineages.

Our study demonstrates general patterns of defensive colour evolution in elapid snakes and highlights the prevalence and key role of hidden colour states in the evolution of aposematism. As previously demonstrated in amphibians28, our phylogenetic analysis provides evidence that hidden warning signals can serve as an intermediary stage in the transition from camouflage to aposematism in elapid snakes, although there have also been direct transitions of species with camouflage to species with conspicuous signals. This finding offers a potential resolution to the paradox of the initial evolution of aposematism, suggesting that hidden colour states could facilitate this transition. That said, we stress that hidden-coloured states were likely present early in the Elapidae lineage, following a single transition from a cryptic ancestor. This early origin allowed hidden-coloured species to serve as a common precursor in all subsequent transitions. While our analysis is limited to the family Elapidae, where defensive coloration is more diverse than in other snake groups, most of which are predominantly camouflaged, it may not be a coincidence that aposematic species are rare in groups where hidden-coloured species are also rare. The paradox of the initial evolution of aposematism may persist in these groups, but hidden-coloured states could mitigate its associated costs and may facilitate the evolution of aposematism. This, in turn, may influence higher taxonomic patterns in the distribution of aposematic species.

In addition, our behavioural analyses highlight a close co-evolutionary relationship between hidden colours and the defensive behaviours. Hidden signals and associated defensive behaviours like flash displays and deimatism are widespread in the animal kingdom and are often observed in clades that contain aposematic species29. Therefore, it is possible that the hidden signal stepping-stone route to aposematism is not restricted to herpetofauna. However, as our results in elapids demonstrate, other evolutionary routes can bypass the need for hidden signals in the transition from camouflage to aposematism, and this may extend beyond this taxon. For example, nudibranchs often mimic the toxic cnidarians from which they sequester their chemical defences, while many aposematic mammals utilise defences that do not require sampling or close contact by predators, such as the noxious sprays of skunks and African polecats12,40. Such defences may reduce the costs associated with the initial evolution of aposematism.

Methods

An extensive list of elapid species was obtained from the Reptile Database (http://www.reptile-database.org)41. We performed a phylogenetic analysis of the anti-predator coloration adopted by elapids based on classifying their images, as well as their defensive behaviours when approached by predators, based on both video and pictorial data.

Colour data acquisition and classification

All species on the list were categorised into one of three antipredator coloration groups based on the images obtained from online sources (Data S1). In making the classification, conspicuous colours were defined as high contrast or bright colours that are uncommon in natural backgrounds and are commonly associated with aposematic signals37,42. These include bright yellows, reds, oranges, blues, and high contrast black and white markings. Cryptic coloration was defined as colours that resemble the substrates that are common in natural backgrounds, such as leaf litter, foliage, tree bark, rocks, and sand. The cryptic coloration usually includes brown, tan, grey, and green colours. A species was deemed conspicuous (Con) when its dorsal colours were conspicuous, regardless of ventral colours. A species was classified as cryptic (Cry) when its dorsal colours were cryptic and lacked any hidden conspicuous colour patches on the body. Species with hidden colour signals (Hidden) were defined as having a cryptic dorsal colour but possessing conspicuous colour patches, usually on the whole or part of the venter (e.g., underside of tails) that are typically hidden when resting. Additionally, some species, such as Naja naja, exhibit conspicuous coloration on the skin in between the scales that is only visible during hooding displays when the skin is stretched, and the scales are separated. These species were also categorised as having hidden signals.

Elapid snakes encompass considerable ecological diversity, so what constitutes a hidden signal may differ based on their ecological contexts, snake behaviours, and observer orientations, which are factors that we were not able to incorporate into our analysis. Generally, coloration on the ventral surface is clearly only exposed transiently and therefore qualifies as a hidden signal. However, a notable exception to this is in sea snakes (subfamilies Hydrophiinae and Laticaudinae), which swim suspended in the water column where their ventral surfaces are readily visible most of the time. Because of this, no sea snake species were classed as having hidden signals. However, we note that the colour categorisation of some sea snake species, such as Hydrophis platurus, may depend on the viewer. This species has a yellow belly and a dark brown dorsum, appearing aposematic underwater but camouflaged to aerial predators such as ospreys and sea eagles, which approach exclusively from above. In our list, H. platurus is the only species that exhibits such a bicolour pattern.

There were some standard challenges to defining whether a species exhibits polymorphism or not. While the classical definition of colour polymorphism is based on the presence of multiple discrete forms within a single population, we used a restricted definition of the term, deeming a species as polymorphic when we observed two or more of the above colour classes exhibited by different individuals of the same species. This was because polymorphic forms with the same antipredator signals would fall into the same category in our analysis. We appreciate that some morphs may occur at very low frequencies within a population or be restricted to a very limited geographical range, and as such, may not be represented in the data source we sampled.

To obtain images for categorisation, all species' scientific names were searched on Google® Images. Snake images were only used if they had been uploaded by reliable sources, usually a biodiversity database or naturalist community (Data S1). We restricted our image sampling to naturally occurring individuals and excluded those resulting from selective breeding or colour abnormalities (i.e., albinism). All species were categorised following the classification above by 3 independent observers: KLH and two independent observers (JB & RH) recruited from the Canadian Herpetological Society. The two external observers were trained to use the same categorisation scheme as KLH by being shown examples of clearly cryptic and aposematic species in non-elapid taxa to define what sorts of colours fall into the respective categories. Wherever possible, different images of each species were categorised by KLH and by the two external observers (Data S1). This was done to demonstrate the generality of the categorisation across separate individuals of the same species.

In most species (62%), the prepared images consisted of two images, one showing the dorsum and another showing the venter. For the rest of the species, both the dorsal and ventral coloration were visible from one image. Since any snake that exhibited conspicuous dorsal coloration would be ranked as conspicuous regardless of ventral coloration, some species for which images of the ventral surface were unavailable were provisionally included in the categorisation. This was done when KLH considered the dorsal coloration to be unambiguously conspicuous. When this occurred, the species was categorised as conspicuous by KLH and images of the dorsal surface were presented to the other categorisers. If the other categorisers had ranked any of these species as anything other than conspicuous, they would have been omitted from the analysis. However, this never occurred, and all 54 of these species were ranked with 100% agreement across all categorisers. When polymorphic forms were detected during image collection, each morph was categorised separately. All the images were presented to the external observers through a Zoom® meeting. For all species characterised by KLH as polymorphic, each morph was presented on a separate slide and categorised separately as if they were independent species. We classified 269 species, but ultimately analysed 251 species with known phylogenetic relationships.

Naturally, photo-based colour classification has drawbacks, as it does not account for snakes’ micro-habitat choices or predator (notably bird) vision—both crucial for assessing conspicuousness against natural backgrounds43,44. However, in global-scale comparative studies like ours, incorporating these factors is challenging, yet significant evolutionary patterns have still been successfully inferred from photos28,45. Public photos also lack ultraviolet (UV) colour, which can be seen by some natural predators such as birds and other snakes37. Recent evidence shows widespread evolution of UV colours in both camouflaged and aposematic snakes, especially in their venter46. In our classification, UV colours in visually conspicuous species would still be classified as conspicuous. For camouflaged species, UV might compromise camouflage, yet it may also help conceal against UV-reflecting substrates or serve as a predator deterrent via UV on the venter46. Thus, our classification may misidentify UV-hued species as cryptic if UV serves as a predator warning signal, although how frequently this occurs is unclear.

Defensive behaviour data acquisition and classification

KLH categorised the defensive behaviours of snakes using a scheme based on the descriptions provided by the California Herps webpage (www.californiaherps.com) and published literature47. Although snakes exhibit a variety of defensive behaviours, including acoustic signals such as hissing or tail rattling48,49, for the purposes of this study, we focused on visual defensive behaviours of snakes that involve showing their ventral surface. This includes (i) hooding, defined as lifting the anterior portion of the body off the ground and spreading the ribs to expose the ventral surface (Fig. 1D), and (ii) non-hooding defensive behaviours that encompass either flipping over entirely, lifting the underside of the tail, or lifting sections of the body to show the ventral surface (Fig. 1E for example). There were practical challenges in categorising defensive behaviours due to their diversity and the lack of clear distinctions between different behaviours. For analytical purposes, we classified each elapid species into one of three behavioural categories: (i) no evidence of the presence of venter-revealing defensive behaviours, (ii) showing hooding behaviours, (iii) showing a defensive behaviour that involves exposing the ventral surface that is not hooding. Naturally, how salient a behaviour depends on habitat and context. However, this generalised categorisation schema is useful in enabling broad multispecies comparisons.

There may be functional distinctions between hooding and non-hooding displays, with hooding displays in venomous snakes likely signalling imminent defence and dissuading predators through startle or by accentuating the size and ferocity of the snake, while non-hooding hidden signals could be aposematism or thanatosis50. As such, hooding may be more closely associated with an impending potent reaction, while non-hooding displays may be less dependent on the defence itself and more susceptible to being exploited by undefended Batesian mimics50. Naturally, acquiring behavioural data from over a hundred species of snakes distributed around the world is challenging. To overcome this, we used two independent methods to survey elapid snake defensive behaviour. First, we observed videos of snakes being confronted by humans; then, we surveyed images of snakes available on the internet (see Data S2,3 for a list of sources). This resulted in the formation of two independently derived behavioural datasets whose collection is described below.

Video-based behavioural survey

Hooding behaviour is a characteristic display of elapid snakes that may function to increase the perceived size of the snake. Although best known from cobras of the genus Naja, hooding behaviour is also exhibited by many other species in this family. To assess whether a species exhibits hooding behaviour or not, the scientific names of all extant described elapid snakes were searched on YouTube® and Google® Video (Data S2, N = 455 videos from 180 species). To be considered evidence that a species does not exhibit hooding behaviour, a video had to show a wild specimen not exhibiting hooding behaviour while being handled or manipulated in the field, either by hand or with tools such as snake hooks, snake tongs, sticks, etc. Because this effectively simulates a predation event, we assume that species that utilise hooding behaviour as part of their defensive behaviour will do so under these conditions. A video was considered evidence of the presence of hooding behaviour if a snake being handled as described above exhibited hooding behaviour. Additionally, some snakes exhibit hooding behaviour simply by being approached by the filmer, even without being touched. These videos were also considered evidence of hooding behaviour. Likewise, some videos of captive snakes exhibiting hooding behaviour were used as evidence of hooding behaviour. However, videos in which no physical contact was made with the snake were never considered evidence of a lack of hooding behaviour. Because snakes often habituate to humans when in captivity, videos of captive snakes not exhibiting hooding behaviour were never considered evidence that a species does not have hooding behaviour.

Time stamps are provided for the relevant times in each video (see uploaded datafile), except for videos that are less than two minutes long or videos in which the entire duration is relevant. The time stamps correspond to the duration of handling time in videos with snakes not exhibiting hooding behaviour. In videos where snakes exhibit hooding behaviour, the timestamps correspond to the duration of the hooding behaviour. One to five videos were used for each species, depending on availability. All video analyses were done by KLH.

In addition to hooding behaviour, many elapids also engage in other defensive behaviours that involve revealing the ventral surface. However, these behaviours were generally not exhibited in the videos that we selected because they require the snake to be on a flat surface, and most videos of snakes being handled involved them being lifted off the ground. Because of this, we additionally utilised an image-based approach to evaluate the presence of snake defensive behaviour (see below).

Photo-based behavioural survey

In order to confirm and broaden our video-based categorisation of elapid snakes’ defensive behaviour, we collected an additional defensive behaviour dataset based on their images. This was accomplished by searching the names of all extant elapids in iNaturalist (http://www.inaturalist.org)51 and surveying all available images of each species. In order to be photographed, snakes must necessarily be approached by a human photographer. This is likely to be perceived by snakes as a predation cue. As such, it is expected that snakes will exhibit defensive behaviours in response. Therefore, if numerous photographs of a species are available yet none show evidence of a given defensive behaviour, it is likely that the species does not exhibit the defensive behaviour in question. If any images of snakes engaging in defensive displays that involved showing the venter were found, then the species was categorised as having such defensive behaviour. For the absence of defensive behaviours, we used an arbitrary criterion based on the availability of the images for each species; if more than 10 images of a species in the field were available and none showed evidence of defensive behaviour, it was considered that this species does not likely utilise such defensive behaviours (the mean and median number of surveyed images for each species were 227 and 66 respectively per species).

To verify more rigorously the absence of defensive behaviour, if more than 10 images were available on iNaturalist, and no evidence of defensive behaviours was found, then the species name was additionally searched in Google Images, first on its own and then with the phrases “defensive display,” “defensive behaviour,” and “defensive posture” successively. If an image of a ventral surface-exposing defensive displays of a snake was found (Data S3), then that was considered evidence that the species has such defensive behaviour. However, if no such evidence was found, then the species was categorised as not having evidence of venter-revealing defensive behaviours. Whenever a defensive behaviour was found in a species, we deemed a species to have either hooding or non-hooding defensive behaviours. The classification of hooding behaviour followed the video-based definition. The non-hooding defensive behaviours include lifting the tail such that the ventral coloration is revealed, or rolling over, displaying the entire ventral surface.

Using the two behavioural datasets described above, we classified a species as exhibiting hooding behaviour if this behaviour was observed in either video or photo sources. Similarly, if evidence indicated that a species displays non-hooding defensive behaviour in either source, it was classified accordingly. Hooding behaviours were identifiable in both video and image sources, whereas information on non-hooding defensive behaviours was available only from images. Overall, video- and image-based data were largely consistent in detecting hooding behaviour. However, image sources provided more comprehensive information, as all species classified as exhibiting hooding behaviour based on video evidence were also classified as such from image data. Additionally, we identified five additional species displaying hooding behaviour in cases where no video data were available. Information on non-hooding defensive behaviours was exclusively derived from image sources.

Phylogenetic analysis

All analyses were conducted in the R programming environment52, version 4.4.3. We obtained Elapidae phylogenetic trees using Vertlife (https://vertlife.org). The Vertlife uses the phylogenetic tree of 9754 squamate species by Toniri et al.53 as a backbone and produces distributions of trees with subsets of taxa. We generated phylogenetic trees for 251 species (~62% of extant elapid snakes) for which images were available. We first extracted 1000 trees randomly drawn from the posterior distribution. Then, we generated the maximum clade credibility (MCC) tree using the ‘maxCladeCred’ function in the ‘phangorn’ package54. The main phylogenetic analyses were performed using the MCC tree, while the rest of the trees were also used for supplementary analyses to validate the robustness of the main results.

We employed discrete character evolution models implemented in the ‘fitMk’ function (but also used equivalent alternatives ‘fitHRM’ or ‘fitMk.parallel’ using the same model structure when ‘fitMk’ performed unstable or to speed up the process) in the ‘phytools’ package to estimate the transition rates between each colour state55. Treating polymorphic states needed special attention due to the low number of extant species in each state (Table S1). First, despite the low number of species for each group, we considered all polymorphic combinations (Cry/Hidden, Cry/Con, Hidden/Con, Cry/Hidden/Con) as separate states without merging them into one combined polymorphic state; this makes sense because polymorphic states were comprised of different combinations of colour groups which, in consequence, influence which colour state to evolve from or to. Next, we assumed that the transition rates between all polymorphic states were zero. This was based on the fact that all polymorphic states were located independently from each other in the phylogeny; thus, the direct transitions between different polymorphic states were unlikely. Additionally, we considered that each polymorphic state could evolve from, or to, one of the monomorphic states already included in the polymorphic forms (i.e., Cry/Hidden polymorphic states cannot evolve to or from Con states). Finally, we let the transitions from or to any polymorphic states to a monomorphic state free to vary (i.e., parameters were not set to zero and estimated by the model). Consequently, while we tested specific hypotheses for the transitions among the major monomorphic states, we did not test specific hypotheses regarding polymorphic states. This was (i) because the number of species in each polymorphic state is too low (Table S1; all less than six), thus the estimated transition rates were difficult to be generalised, and (ii) to still account for any contributions of polymorphic states to transition dynamics.

After determining how to handle the polymorphic states, we generated six hypothetical models for the transitions among the monomorphic states. These were All-rates-different (ARD), Symmetric (SYM), Equal-rates (ER), Intermediate, Cost-offset, and Secondary models (Fig. 2A). The ARD model allows all the transition rates between each monomorphic state to vary freely. The SYM model assumes that forward and reverse transitions share the same parameters. In the ER model, a single parameter governs all transition rates. The Intermediate model assumes that Hidden states serve as an intermediate stage between Cry and Con states by not allowing direct transitions between Cry and Con states. Cost-offset models do not allow direct transitions between Hidden and Cry states, making Hidden states evolve only from or to Con states. This assumes that Hidden states evolve from Con states to alleviate the high detectability costs of conspicuous colours27. The Secondary model assumes that the hidden colours in elapid snakes mainly evolve as a secondary defence of cryptic species; thus, the Secondary model only allows the Hidden states to evolve from or to Cry but not Con states. Then, we determined the best-supported model using corrected Akaike Information Criterion (AICc) and associated AIC weights.

We used the ‘ancr’ function in the ‘phytools’ package for ancestral character reconstruction55. The ancestral characters were reconstructed using the parameters of the best-supported model. We tried both marginal (finding the state at the current node that maximises the likelihood, integrating over all other states at all nodes; gives the results as proportional support for each state for each node) and joint (finding the set of character states at all nodes that jointly maximise the likelihood; gives the results as a single most likely state for each node) methods56. We primarily interpret the transitional patterns using the results from joint methods due to their ease of interpretation. However, we also compared the results of joint and marginal methods to confirm the consistency between the two methods and included the marginal results in the Supplementary materials. Additionally, we performed stochastic character mapping using the best-supported model to estimate a posterior distribution on the number of transitions that occurred among different states57. We sampled 100 stochastic character maps using ‘make.simmap’ function in ‘phytools’ package55.

For the analysis including behavioural data, we were able to analyse 180 species. For this dataset, we first excluded all polymorphic species from the analyses, because the number of species in each group is either zero or very few, making transition analysis impossible to conduct. Next, we first tried generating a nine-state dataset (three colour categories × three behaviour categories) and examining the transitions among the nine states. However, the estimated transition rates had low reliability (i.e., different functions of the discrete state evolution model, such as ‘fitMk’, ‘fitMk.parallel’, ‘corHMM’, yielded disparate results) in states with only a few species. Therefore, instead of analyzing the nine-state models, we deliberately decided to analyse colour and behaviour separately.

For the defensive behaviour data, we compared the model fits of ARD, SYM, and ER models. We also generated three hypothetical models that have the equivalent model structure of Intermediate, Cost-offset, and Secondary models in colour analysis and compared the model fit. These models included scenarios where (i) non-hooding defensive behaviours can only evolve from/to non-display states via the hooding behaviour state (Hooding Intermediate), the hooding behaviour can only evolve from/to non-display states via non-hooding defensive behaviour states (Other Displays Intermediate), and (ii) (iii) hooding behaviour and non-hooding defensive behaviours evolve independently without direct transitions between the two (Independent) (see Fig. S1 for visual description of the models). We then estimated ancestral character states using the best-fitted model based on AICc.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data generated in the study have been deposited in the Figshare database (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28435067.v2)58. Also, the images and videos we used were collected from open databases listed in Supplementary Data S1–3.

Code availability

The code of the study has been deposited in the Figshare database (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28435067.v2)58.

References

Ruxton, G. D., Allen, W. L., Sherratt, T. N. & Speed, M. P. Avoiding Attack: The Evolutionary Ecology of Crypsis, Aposematism, and Mimicry. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2018).

Stevens, M. & Merilaita, S. Animal Camouflage: Mechanisms and Function. (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2011).

Poulton, E. B. The Colours of Animals: Their Meaning and Use, Especially Considered in the Case of Insects. (D. Appleton, London, 1890).

Bates, H. W. XXXII. Contributions to an insect fauna of the Amazon Valley. Lepidoptera: Heliconidae. Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. os. 23, 495–566 (1862).

Müller, F. Ituna and Thyridia: a remarkable case of mimicry in butterflies. Trans. Entomol. Soc. Lond. 1879, 20–29 (1879).

Fisher, R. A. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. (Oxford University Press, 1930).

Wiklund, C. & Järvi, T. Survival of distasteful insects after being attacked by naive birds: a reappraisal of the theory of aposematic coloration evolving through individual selection. Evolution 36, 998–1002 (1982).

Sherratt, T. N. & Stefan, A. Capture tolerance: a neglected third component of aposematism? Evol. Ecol. 38, 257–275 (2024).

Wallace, A. Mimicry, and other protective resemblances among animals. West. Q Rev. 32, 1–43 (1867).

Speed, M. P. & Ruxton, G. D. Warning displays in spiny animals: one (more) evolutionary route to aposematism. Evolution 59, 2499–2508 (2005).

Battisti, A., Holm, G., Fagrell, B. & Larsson, S. Urticating hairs in arthropods: their nature and medical significance. Annu Rev. Entomol. 56, 203–220 (2011).

Howell, N. et al. Aposematism in mammals. Evolution 75, 2480–2493 (2021).

Smith, J. M. Group selection and kin selection. Nature 201, 1145–1147 (1964).

Ruxton, G. D. & Sherratt, T. N. Aggregation, defence and warning signals: the evolutionary relationship. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 273, 2417–2424 (2006).

Sillén-Tullberg, B. Evolution of gregariousness in aposematic butterfly larvae: a phylogenetic analysis. Evolution 42, 293–305 (1988).

Tullberg, B. S. & Hunter, A. F. Evolution of larval gregariousness in relation to repellent defences and warning coloration in tree-feeding Macrolepidoptera: a phylogenetic analysis based on independent contrasts. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 57, 253–276 (1996).

McLellan, C. F., Cuthill, I. C. & Montgomery, S. H. Warning coloration, body size, and the evolution of gregarious behavior in butterfly larvae. Am. Nat. 202, 64–77 (2023).

Wang, L., Cornell, S. J., Speed, M. P. & Arbuckle, K. Coevolution of group-living and aposematism in caterpillars: warning colouration may facilitate the evolution from group-living to solitary habits. BMC Ecol. Evol. 21, 25 (2021).

Mouy, H. The function of red and banded patterns in snakes: the ophiophagy hypothesis. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 142, 375–396 (2024).

Yachi, S. & Higashi, M. The evolution of warning signals. Nature 394, 882–884 (1998).

Lindström, L., Alatalo, R. V., Mappes, J., Riipi, M. & Vertainen, L. Can aposematic signals evolve by gradual change?. Nature 397, 249–251 (1999).

Caro, T., Sherratt, T. N. & Stevens, M. The ecology of multiple colour defences. Evol. Ecol. 30, 797–809 (2016).

Cott, H. B. Adaptive Coloration in Animals. (Methuen, London, 1940).

Edmunds, M. Defence in Animals: A Survey of Anti-Predator Defences. (Longman Publishing Group, New York, 1974).

Schlenoff, D. H. The startle responses of blue jays to Catocala (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) prey models. Anim. Behav. 33, 1057–1067 (1985).

Kang, C., Cho, H.-J., Lee, S. & Jablonski, P. Post-attack aposematic display in prey facilitates predator avoidance learning. Front Ecol. Evol. 4, 35 (2016).

Drinkwater, E. et al. A synthesis of deimatic behaviour. Biol. Rev. 97, 2237–2267 (2022).

Loeffler-Henry, K., Kang, C. & Sherratt, T. N. Evolutionary transitions from camouflage to aposematism: Hidden signals play a pivotal role. Science 379, 1136–1140 (2023).

Loeffler-Henry, K., Kang, C. & Sherratt, T. N. Consistent associations between body size and hidden contrasting color signals across a range of insect taxa. Am. Nat. 194, 28–37 (2019).

Lewis, P. O. A likelihood approach to estimating phylogeny from discrete morphological character data. Syst. Biol. 50, 913–925 (2001).

Li, X. & Wiens, J. J. Estimating global biodiversity: the role of cryptic insect species. Syst. Biol. 72, 391–403 (2023).

Rabosky, D. L. No substitute for real data: a cautionary note on the use of phylogenies from birth–death polytomy resolvers for downstream comparative analyses. Evolution 69, 3207–3216 (2015).

Palci, A., Lee, M. S. Y., Crowe-Riddell, J. M. & Sherratt, E. Shape and size variation in elapid snake fangs and the effects of phylogeny and diet. Evol. Biol. 50, 476–487 (2023).

Pyron, R. A., Burbrink, F. T. & Wiens, J. J. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes. BMC Evol. Biol. 13, 1–54 (2013).

Speed, M. P. & Ruxton, G. D. Aposematism: what should our starting point be?. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 272, 431–438 (2005).

Shine, R., Brown, G. P. & Goiran, C. Frequency-dependent Batesian mimicry maintains colour polymorphism in a sea snake population. Sci. Rep. 12, 4680 (2022).

Kojima, Y., Ito, R. K., Fukuyama, I., Ohkubo, Y. & Durso, A. M. Foraging predicts the evolution of warning coloration and mimicry in snakes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2318857121 (2024).

Simões, B. F. et al. Visual Pigments, Ocular Filters and the Evolution of Snake Vision. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 2483–2495 (2016).

Allen, W. L., Baddeley, R., Scott-Samuel, N. E. & Cuthill, I. C. The evolution and function of pattern diversity in snakes. Behav. Ecol. 24, 1237–1250 (2013).

Avila, C., Núñez-Pons, L., & Moles, J. From the tropics to the poles: chemical defense strategies in sea slugs (Mollusca: Heterobranchia). In Chemical Ecology (ed. Puglisi, M. P. & Bacerro, M. A.) 71–163. (CRC Press, 2018).

Uetz, P. & Etzold, T. The EMBL/EBI reptile database. Herpetol. Rev. 27, 174–175 (1996).

Mappes, J., Kokko, H., Ojala, K. & Lindström, L. Seasonal changes in predator community switch the direction of selection for prey defences. Nat. Commun. 5, 5016 (2014).

Stevens, M. & Ruxton, G. D. The key role of behaviour in animal camouflage. Biol. Rev. 94, 116–134 (2019).

Endler, J. A. A predator’s view of animal color patterns. in Evolutionary Biology. (ed. Max K. Hecht, William C. Steere, B. W.) 319–364 (Springer, New York, 1978).

Arbuckle, K. & Speed, M. P. Antipredator defenses predict diversification rates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 13597–13602 (2015).

Crowell, H. L., Curlis, J. D., Weller, H. I. & Davis Rabosky, A. R. Ecological drivers of ultraviolet colour evolution in snakes. Nat. Commun. 15, 5213 (2024).

Seigel, R. A. & Collins, J. T. Snakes: Ecology and Behavior. (McGraw-Hill, 1993).

Young, B. A. Snake bioacoustics: toward a richer understanding of the behavioral ecology of snakes. Q Rev. Biol. 78, 303–325 (2003).

Klauber, L. M. Rattlesnakes. (Univ of California Press, 1972).

Caro, T. & Ruxton, G. Aposematism: unpacking the defences. Trends Ecol. Evol. 34, 595–604 (2009).

iNaturalist. Available from https://www.inaturalist.org. (accessed April 2024).

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. (version 4.4.3.) R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria http://www.r-project.org/ (2024).

Tonini, J. F. R., Beard, K. H., Ferreira, R. B., Jetz, W. & Pyron, R. A. Fully-sampled phylogenies of squamates reveal evolutionary patterns in threat status. Biol. Conserv 204, 23–31 (2016).

Schliep, K. P. phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics 27, 592–593 (2011).

Revell, L. J. phytools 2.0: an updated R ecosystem for phylogenetic comparative methods (and other things). PeerJ 12, e16505 (2024).

Pagel, M. The maximum likelihood approach to reconstructing ancestral character states of discrete characters on phylogenies. Syst. Biol. 48, 612–622 (1999).

Huelsenbeck, J. P., Nielsen, R. & Bollback, J. P. Stochastic mapping of morphological characters. Syst. Biol. 52, 131–158 (2003).

Kang, C., Loeffler-Henry, K. & Sherratt, T. N. Data and R code for the manuscript “Hidden colour signals as key drivers in the evolution of anti-predator coloration and defensive behaviours in snakes”. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.28435067.v2 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to James Butler and Rosie Heffernan for their role in categorising snake coloration. KLH is funded by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) fellowship, while TNS is supported by an NSERC Discovery Grant. CK is supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (RS-2024-00333709 and RS-2024-00405751) and the Creative-Pioneering Researchers Programme through Seoul National University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.L.H., T.N.S., and C.K. conceived the study. K.L.H. conducted the image and video collecting and classifications. C.K. conducted the phylogenetic analysis with input from K.L.H. and T.N.S. All authors contributed to discussions and interpretation of the data, and formulating the initial draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Tim Caro and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Loeffer-Henry, K., Kang, C. & Sherratt, T.N. Hidden colour signals as key drivers in the evolution of anti-predator coloration and defensive behaviours in snakes. Nat Commun 17, 1050 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67809-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67809-y