Abstract

Single-beam femtosecond laser pulses can surpass the diffraction limit of conventional focusing systems, enabling deep sub-waveguide single-spot modifications via nonlinear absorption at the focus. However, extending this capability to multi-beam parallel processing has been fundamentally limited by the diffraction limit (~λ/2). Herein, we experimentally and theoretically clarify that this limitation stems from spatial coherence and temporal sequence interference, inducing laser-matter interaction crosstalk, non-uniform modifications, and sparse duty-cycle structures. To address this, we propose a de-coherent parallel direct laser writing (Dc-PDLW) strategy, utilizing a patterned single pulse together with a de-coherent holographic algorithm (SSP-BM) to ensure multi-foci polarization orthogonality and eliminate spatial coherence. This method achieves single-shot fabrication of ultra-dense nanopore arrays, with 300 nm (~λ/4) resolution in crystals. We further demonstrate centimeter-scale 3D Pancharatnam–Berry phase plates and voluminous cipher sequences, realizing high-density 3D phase and polarization coding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the field of nanophotonics, the duty cycle emerges as a pivotal metric for quantifying the percentage of the active part in a periodic system. The engineering of duty-cycle in nanostructured elements at the sub-wavelength scale has been demonstrated to enhance the precision of spatial optical phase encoding and structural unit density, thereby enabling unparalleled control of electromagnetic fields1,2,3. This, in turn, facilitates the integration of high-resolution wavefront shaping4,5,6, efficient optical phased arrays7, dynamic holographic reconstruction8,9,10, and multifunctional optical elements11,12,13. The combination of high-duty-cycle architectures with femtosecond laser direct writing (FLDW) technology demonstrates unique fabrication advantages, including the absence of a mask and the ultra-short pulse characteristics14, which enable non-thermal fusible spatial optical phase encoding with true 3D nanoscale precision in transparent media15,16,17,18. This development paves the way for breakthroughs in technologies, such as meta-surface fabrication, LIDAR manufacturing, computational holography, integrated photonic circuits, and optical information encryption, among others.

In the pursuit of efficient spatial optical phase encoding, single-beam processing with femtosecond lasers has been demonstrated to yield sub-wavelength single-spot sizes that overcome the diffraction limit thanks to nonlinear absorption effects19,20,21. However, in conventional serial laser processing15,22, the structure spacing in unit-by-unit fabrication modes is constrained by light-field redistribution effects arising from spatial coherence. This constraint impedes the fabrication of high-duty-cycle architectures23,24. In consideration of the aforementioned point, the parallel processing using multifocal beams is proposed as a strategy of bypassing the light-field redistribution effects caused by the seed structure to eliminate the spatial coherence. The multi-beam parallel processing can be achieved through various beam-splitting and wavefront-shaping techniques, such as the diffractive optical elements25, the micro-lens arrays26,27, and computational holography based on the Weighted Gerchberg-Saxton (WGS/GSW) iterative algorithm28, and the non-iterative optimal rotation angle algorithm29, the superimposed phase design14. Among these methods, the WGS/GSW iterative algorithm has great flexibility and the best parallel beam uniformity, making it a widely-used method for generating complex multi-beam patterns. However, it is important to note that GSW algorithms do not uniquely determine the phase during the iteration process, which can lead to wavefront disorder that may degrade processing performance30,31,32,33,34, especially under high numerical aperture (NA) focusing conditions. In particular, in the context of this study, where adjacent focal spots are brought into close proximity and their optical fields begin to overlap, this wavefront disorder can induce complex spatial coherence effects, making it difficult to surpass the coherent diffraction limit that constrains the minimum achievable spacing between adjacent spots ( ≈ 1.47λ/NA)35. Furthermore, by controlling the polarization orthogonality between adjacent beams, the spatial coherence effects of the optical fields can be effectively eliminated, thereby reducing the minimum achievable spacing between adjacent focal spots by half ( ≈ 0.73λ/NA)36, approaching the coherent diffraction limit. However, in multi-focus parallel femtosecond laser processing, the spacing between adjacent focal spots has consistently been constrained by the coherent diffraction limit. In contrast, single-focus femtosecond laser processing can readily surpass this limitation owing to the strong nonlinear threshold effect of femtosecond pulses, which enables the fabrication of nanostructures with sub-100-nanometer features37,38,39,40,41,42.

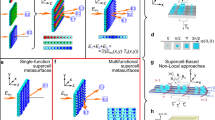

Here, we propose a de-coherent parallel direct laser writing (Dc-PDLW) strategy, leveraging a patterned single pulse and a de-coherent holographic algorithm that combines a stripe segmentation phase hologram with a binary mask (SSP-BM) to eliminate the interaction crosstalk generated by spatial coherence and temporal sequence interference effects, which allows for the machining of large-scale 3D free-designed optical phase encoding in hard and brittle materials. A schematic diagram of multi-foci phase hologram generation and polarization orthogonality is shown in Fig. 1a. The non-iterative strip segmentation phase hologram circumvents the uneven intensity distribution problem under tight focusing, while the binary mask eliminates coherence between adjacent focal spots, together enabling single-shot fabrication of ultra-dense nanopore arrays. A comparison of the minimum dual-pore spacing achieved by different algorithms is presented in Fig. 1b. With the SSP-BM algorithm, we achieve machining of nanostructures at high-duty-cycle, as well as dense linear array structures. Subsequently, it is demonstrated that the strength of the birefringence effect increases as the dual-pore spacing decreases, which also signifies that there is an augmentation in the capabilities of optical phase encoding, as shown in Fig. 1c. Moreover, the higher modulation efficiency Pancharatnam–Berry phase plate structure is processed using this approach, and a demonstration of polarization-related 3D large area information encryption is also conducted. Dc-PDLW strategy demonstrates strong potential for large-scale 3D high-duty-cycle optical phase encoding, with promising applications in diffractive optical elements, integrated photonic devices, and information encryption.

a Schematic diagram of Dc-PDLW, in which a single spot is modulated into orthogonal polarization bifocal beams for parallel inscription. SSP: the strip segmentation phase method45; BM: binary mask; SSP-BM: the non-iterative stripe segmentation phase hologram with a binary mask; HWP: half-wave plate; OL: objective lens. b Comparison of algorithms for achieving high-duty-cycle processing. CSP: the crescent-shaped segmentation phase method77. SPH: the superimposed phase hologram designing14. GSW: the weighted Gerchberg-Saxton algorithm28. c Relationship between birefringence retardance, and dual-pore spacing. As the dual-pore spacing decreases (corresponding to a higher duty cycle), the amount of birefringence retardance increases. This property is exploited here for fabricating a series of birefringent devices. d Energy distribution of the deviated spot affected by the seeding structure in an close range (d1), along with the energy distribution contour (d2) during the conventional serial laser processing. e Schematic diagram of Debye diffraction under high-numerical-aperture focusing: definition of the pupil plane (the x’-y’ plane) and the focus plane (the x-y plane). f1–f3 The SEM images of the multifocal single-pulse nanopore processed using the GSW algorithm, the non-iterative algorithm, the SSP-BM algorithm, and the corresponding simulation. Scale bars: 500 nm. f4 Simulated bifocal light intensity distribution for the three methods (the weighted GS algorithm, the non-iterative algorithm, the SSP-BM algorithm), NI: non-iterative algorithm. g Customized pattern processed by the SSP-BM algorithm. Scale bar: 50 μm. h Schematic diagram of the SSP-BM generation, taking a six-focal-spot array as an example.

Results and Discussion

The principle of the de-coherent parallel direct laser writing process

In conventional serial laser processing, the employment of the FLDW method may be affected by the temporal sequence interference effect, resulting in the redistribution of the light field. As shown in Fig. 1d1, d2, the latter incident beam is markedly influenced by the original structure (located to the right of the latter incident beam), resulting in a shift of its peak energy and a distortion of the Gaussian distribution (Fig. 1d2), which in turn leads to a deviation from the ideal distribution of the structure produced by the latter pulse (see Supplementary Text S1 for more details).

In contrast, parallel laser processing employing holographic beam shaping generates multiple focal spots simultaneously, effectively avoiding cumulative field perturbations and material-induced nonuniformity inherent to serial exposure43,44. Particularly under tightly focused conditions (i.e., high-numerical-aperture systems), non-iterative optical phase holograms produce a uniquely determined phase distribution, ensuring uniform and stable multifocal generation without parasitic diffraction artifacts45,46. A direct comparison of the focal field distributions (under the Debye approximation, Fig. 1e) and corresponding processed structures (Fig. 1f1, f2) confirms that the iterative method induces energy redistribution and additional diffraction orders near the focus, leading to structural distortions and evident side flaps (Fig. 1f1).

Given the aforementioned considerations, we suggest a non-iterative SSP-BM algorithm, which applies stripe segmentation and binary masking to the phase hologram. The corresponding optical path is illustrated in Fig. 1e. The non-iterative phase hologram formulae for an arbitrary spatial position distribution based on the Debye diffractive electric field distribution formulae are as follows47,48,49 (see Supplementary Text S2 for a detailed derivation):

where φM is the phase loaded into SLM. Δx and Δy are the displacements of the center of focus. R is the radius of the phase plane. NA is the numerical aperture of the objective lens. nt is the material refractive index.

To achieve a high-duty-cycle, the concept of hologram partitioning is introduced. Among its forms, strip partitioning enables parallel processing of multiple focal spots while maintaining high uniformity45,50,51. Furthermore, in order to achieve a further minimization of proximity crosstalk, it is necessary to consider the effect of the phase term. A common method of reducing the effect of phase term interference is the adjustment of the polarization state36,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59. In actual processing, the binary phase hologram is a widely utilized method for the control of polarization states at varying positions across multiple focal spots46,60. In accordance with this, we propose the combination of a binary mask with a strip segmentation phase hologram as a means of ensuring the elimination of the crosstalk generated by spatial coherence and temporal sequence interference effects (Detailed derivations are provided in the Supplementary Text S3-S4). This approach can effectively reduce the intensity fluctuations and crosstalk between spots at the nanoscale, thereby breaking the diffraction limit.

Theoretical analysis has thus far validated that SSP-BM can eliminate the effect of crosstalk, thus enabling a high-duty-cycle nanostructure via the Dc-PDLW approach incorporated with the threshold effect of multiphoton absorption, which are intuitively displayed in Fig. 1f3. A comprehensive overview is provided in Fig. 1f4, which presents the central light intensity profile. It can be observed that the GSW algorithm yields a structure with an evident side flap. In contrast, the non-iterative algorithm, although it resolves the side flap issue due to the wavefront disorder, still exhibits a similar pronounced crosstalk as the GSW algorithm. This has been effectively addressed in the SSP-BM algorithm, as evidenced by the absence of interference between the adjacent focal spots (see Supplementary Text S5 for a comparison between the non-iterative ORA algorithm and the SSP-BM algorithm). To demonstrate the superiority of the SSP-BM algorithm, a customised structure fabricated with SSP-BM overserved by SEM images is shown in Fig. 1g. The flow chart of the hologram generation is illustrated in Fig. 1h (M denotes the number of focal spots; N denotes the number of partitions):

Step 1: Define the custom multi-focus array to be loaded, and determine M according to the number of focal spots. Then, according to the required positions, attach the corresponding XY coordinates to the focal spots in M different positions, and calculate the non-iterative phase hologram.

Step 2: Determine N partitions based on actual processing needs. Subsequently, the entire phase hologram (Main area) is divided into N partitions (Subarea). Then, the M focal spots generated in the first step are filled in the subarea.

Step 3: Generate a binary phase mask, and superpose the phase overlapped by partitions with the binary phase mask to obtain the final machining phase hologram.

Uniform parallel processing achieved via de-coherent parallel direct laser writing technology, enabling fabrication of high-duty-cycle nanopore structures

Although the feasibility of the SSP-BM algorithm has been demonstrated through theoretical calculation and simulation, the complex light-matter interactions involved in Dc-PDLW make the process considerably more challenging. The effectiveness and efficiency of the method are further evaluated in the fabrication of nanophotonic structures under various parameters. In our experiment, M = 2 was chosen as the standard experimental configuration (see Supplementary Text S6-S7 for 3D demonstrations with large M).

Herein, N is a core parameter determining the fabrication performance. Figure 2a illustrates the influence of N on the uniformity of bifocal spots denoted as Q, which quantitatively describes the intensity consistency between the two beams of a dual-focus beam. Q is defined as Q = 1-(Imax-Imin)/(Imax+Imin), where I represents the light intensity. It can be seen that the uniformity of bifocal spots exhibits an increase with N. Upon reaching N = 95, the uniformity tends to reach a saturation, resulting in a uniformity value of 99.4%. (Quantitative Comparison of Bifocal Uniformity Generated by the SSP-BM Algorithm and Other Algorithms in Supplementary Table S1).

a Relationship between the number of partitions (N) and the multi-focus uniformity (Q) (right). Left inset: the light spot intensity distribution of bifocal spots when the cross-sectional lines are N = 60 (Q = 79.7%) and N = 80 (Q = 92.6%), respectively. b Feature dimensions. c The gap width and total width between two adjacent nanostructures fabricated under different pulse energies, with an algorithm-preset spacing of 1120 nm. d The SEM images of the single-pulse fabricated nanostructures by two different algorithms (the SSP-BM and the GSW) with decreasing dual-pore spacing. Scale bars: 200 nm. e Comparison of dual-pore spacing for generating nanostructures using three processing methods (Unit-by-unit: serial laser processing under linear polarization). The yellow line is the theoretical diffraction limit (502 nm) for reference. f SEM image and corresponding EDS (Energy Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy) analysis of the nanostructure. Scale bars: 200 nm.

The distance between adjacent pores in the structure is a significant indicator of the efficacy of the methods employed to achieve a high-duty-cycle. The definition of spacing is given in Fig. 2b. The algorithm preset spacing and location required during processing are achieved by changing the X and Y parameters in the non-iterative phase hologram, as outlined in Eq. (1).

The deposition of laser energy into the interior of the material may result in the formation of micro-cracks, micro/nano voids, and localised amorphisation, contingent upon the processing conditions employed. It is also essential to consider space co-operation effects in order to prevent the formation of heat-affected zones, cracks, voids, or residual stress61. Therefore, the setting of the laser parameters is particularly important in actual processing. When discussing the influence of laser energy on dual-pore spacing in actual processing, we set the algorithm preset spacing to a relatively large value to ensure a large energy interval. As the laser energy increases, the laser-induced modification region becomes larger (Fig. 2c). When the pulse energy is 550 nJ, the gap width is 879 nm, with a total width of 1412 nm. With an increase in laser energy to 850 nJ, the gap width decreases, reaching a minimum of 551 nm and a total width of 1727 nm. Accompanied by the increasing laser energy, nanopores are created at the centre of the light intensity, and a ring-shaped amorphous region is created around it due to the effect of the shock wave, which leads to an increase in the size of the nanopore structure62,63. Concurrently, the diameter of the individual nanopores within the bi-focus nanostructure increases, while the nanopore gap width is diminished as a consequence of internal squeezing. In order to achieve processing with a high-duty-cycle, it is of great interest to ascertain the minimum dual-pore spacing that a given algorithm can actually achieve during Dc-PDLW (see Supplementary Text S8 for the nanopore structure under the condition of large dual-pore spacing conditions). As the algorithm’s preset spacing decreases, we compared the processing results of the SSP-BM and the GSW algorithm. At 300 nm preset spacing, the bifocal nanopore structure processed by SSP-BM was just distinguishable (Fig. 2d1), whereas the nanopore by the GSW was not (Fig. 2d2). The slight ellipticity of the nanopore in Fig. 2d1 mainly stemed from the vector polarization effect of linearly polarized light in a tightly focused optical system64. When the preset spacing was reduced to 200 nm—approaching the diameter of a single nanopore—both algorithms failed to resolve the two nanopores (Fig. 2d3, d4). Notably, at a further reduced preset spacing of 100 nm, the structure processed by SSP-BM remained elliptical, in contrast to the circular single nanopores obtained via the GSW (Fig. 2d5, d6).

To demonstrate the processing superiority of the SSP-BM algorithm, we performed several experiments and compared the dual-pore spacing, which appears to be distinguishable with the iterative algorithm and the unit-by-unit serial writing method under identical laser parameters (224 fs, 450 nJ). As shown in Fig. 2e, the bi-focus nanopore structure exhibits substantial concordance with the prediction of the SSP-BM algorithm, with an average value of 321 nm and a minimum observation pitch of 292 nm. In contrast, the iterative algorithm exhibits an average dual-pore spacing of 545 nm due to the disorder of the wavefront and the inability to effectively address multi-beam crosstalk, as previously discussed. The deviated effect of light field redistribution is pronounced when linearly polarized light is employed for unit-by-unit conventional serial laser processing, resulting in a larger average dual-pore spacing of 601 nm. The results illustrate the superiority of the Dc-PDLW method for realizing high-duty-cycle processing.

Meanwhile, the samples were subjected to EDS (Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy) analysis, as illustrated in Fig. 2f. This reveals that during the processing of the bifocal structure, the formation of nanostructures resulted in the original structure being compressed inwards, causing the main constituent elements Al and O in sapphire to be compressed from the outside to the center near the midpoint of the connection. Consequently, the element distribution exhibits a distinct peak at the center of the connection (superior to the outermost unmodified zone), whereas the distribution of pore elements following laser-induced modification corrosion manifests as a valley. Furthermore, the compression zone correlates with the defined gap zone65,66.

To further demonstrate the processing flexibility and superiority of Dc-PDLW, we processed dual-pore structures (Fig. 3a1–a3) and circular dual-pore arrays (Fig. 3c1, c2) based on different spacing settings (Fig. 3b). This was done to verify its efficiency in manipulating optical phase and birefringence. Additionally, it aimed to confirm that the component can serve as a unit of a birefringent device, similar to a nanofin unit. The refractive index variation of nanostructures with different dual-pore spacing was obtained by quadriwave lateral shearing interferometry67 using a wavefront phase sensor (as shown in Fig. 3a2). The results show that the maximum refractive index change of the structure after laser irradiation reached −0.25×10-3 (Fig. 3a3). As illustrated in Fig. 3b, the red profile line denotes the refractive index change of the large-spacing bifocal structure, and it can be observed that the refractive index curve contains a distinct double peak. As the dual-pore spacing decreases, the refractive index change becomes co-influenced by the bifocal nanostructures, as illustrated by the blue profile line, appearing as a superposition of bimodal phase delays that manifests in the form of a single peak. Fig. 3c1-c2 illustrates a circular dual-pore array structure that demonstrates the large-scale, 3D phase and birefringence encoding capabilities of the Dc-PDLW method. Therefore, decreasing dual-pore spacing enhances the duty cycle and refractive index modulation, establishing a basis for birefringent structure fabrication. The compact system architecture of Dc-PDLW benefits from the employment of SLM, making it fully scalable in mass production. During the large-scale processing of a micro-nano birefringent device, it takes less than 3 min to achieve a complete phase encoding process (2 x 2 mm). The high processing rate of micro- and nano-optical products demonstrates the great potential and full feasibility of Dc-PDLW technology in practical applications.

a1 The generated nanostructures with different dual-pore spacing and their corresponding holograms (left insets). a2,a3 The measured optical phase difference of dual-pore arrays (a2) and the calculated refractive index changes (a3). b Refractive index profiles at different dual pore spacing (colors correspond to contour positions in (a2). c Customized circular dual-pore arrays with varying spacing and the resulting refractive-index maps.

Applications of de-coherent parallel direct laser writing technology

From an application perspective, the proposed Dc-PDLW approach introduces a fundamentally new class of anisotropic dual-pore nanostructures that are significantly different from existing laser-induced anisotropic structures, such as self-assembled nanogratings68,69, type-X birefringent structures70, and isotropic nanovoids71. Unlike these prior methods, which rely on multi-pulse accumulation or near-field enhancement and consequently suffer from limited controllability and scalability, our SSP-BM-based strategy achieves subwavelength features with a single pulse, enabling predictable birefringence tuning, high uniformity, and precise polarisation encoding. Beyond its technical innovation, this method provides complete freedom in polarization optics design, allowing simultaneous control over both birefringence magnitude (Fig. 1c) and optical-axis orientation (Fig. 4b), and underscoring the strong potential of this approach for high-density, polarization-resolved optical storage and advanced photonic device fabrication.

a Optical microscopy image (left) and diffraction pattern (middle) of fabricated diffraction gratings with periods d = 1 μm and d = 2.5 μm, and the relationship between the diffraction angle and the grating period (right). b SEM image of fabricated PB phase plate, showing enlarged structural units (right) with orientation angles of 0°, 45°, 90°, 135°. Scale bars: 500 nm. c Optical microscope image of the polarization gratings with a polarizer under cross-polarized white light illumination. Scale bars: 10 μm d, e Demonstration of information encryption: information is written in the in-situ superposition, and no information is presented when natural light is incident. The correct information can only be read out when the material is illuminated with specific orthogonal polarized light. Scale bars: 100 μm.

The Dc-PDLW method can be efficiently extended from a point into line-like structures, enabling the inscription of 3D photonic devices. At the same time, this technology is employed to generate dense, highly integrated diffraction gratings (Fig. 4a), where hologram control allows precise regulation of the grating period (d). A decrease in the grating period leads to an increase in the diffraction angle. For periods of d = 1 μm and d = 2.5 μm, the diffraction angles are measured to be 0.14 and 0.05, respectively. The resulting curve agrees well with the grating diffraction formula. Further results on the influence of laser energy on gratings can be found in Supplementary Text S9.

Another important application lies in geometric phase and polarization encoding, which can be achieved through space-variant retardance engineered in Dc-PDLW–inscribed anisotropic nanostructures (see Supplementary Text S10 for more details). Benefiting from the de-coherent parallel processing nature of Dc-PDLW, the inter-feature spacing can be significantly reduced, enabling stronger and more precise refractive-index modulation for accurate phase and polarization control. Here, by employing the Dc-PLDW method to modulate the dual-pore spacing and relative orientation of the bifocal nanostructure, equivalent to the engineering of birefringence and the rotation of the optical axis, a polarization-selective grating (Pancharatnam–Berry phase plate structure) is processed70,72,73. Figure 4b shows structures fabricated with a sub-diffraction spacing using the SSP-BM algorithm ( ~ 500 nm, the right inset of Fig. 4b), thereby demonstrating that our Dc-PDLW method can reliably achieve super-resolution machining of large-area 3D diffractive optical elements. Bifocal nanostructures tilted at different azimuthal angles at different locations were sequentially written until a 180-degree cycle is completed, as illustrated in the upper left inset of Fig. 4c. Besides, it can be observed that under orthogonal linearly polarized light, different parts of the PB phase plate structure exhibit different brightness. Modifying the angle of the orthogonally polarized light results in a change in the intensity of the light-dark cycle of the structure due to polarization sensitivity, as shown in the right inset of Fig. 4c.

Given that the different spacing and relative orientation of bifocal nanostructures present varying degrees of light intensity under polarized light illumination, this property can be exploited for the encryption of polarization-related information74,75,76. As shown in Fig. 4d, two messages that include a QR code and an image of a qiushi eagle are inscribed overlapped but with different azimuthal angles. It is evident that when observed through natural light illumination, the QR code information is partially obscured by the eagle pattern, rendering it unreadable. Under a correct observation condition with orthogonal polarized light at 45° and 135°, the encrypted information can be displayed clearly. Figure 4e provides another example of the encryption of messages within a QR code, whereby only the requisite azimuth angle is inscribed within the designated square area. The remaining portion of the square is fixed with dual-pore structures, oriented at an angle that is orthogonal to the inscribed angle. As can be observed, when the image is viewed under natural light, the entire pattern appears completely unreadable. In contrast, when the image is viewed under orthogonally polarized light at 45° and 135°, the QR code information appears readable. The results demonstrate the feasibility of utilizing the Dc-PDLW method for the encryption of polarization-related information (see more demonstrations in Supplementary Text S11–S13).

In conclusion, we have proposed a de-coherent parallel direct laser writing (Dc-PDLW) strategy for the inscription of a nanopore array with an ultra-dense distribution, which is achieved by superimposing a non-iterative strip segmentation phase hologram combined with a binary phase mask, in conjunction with wet etching, to create a nanopore structure with a high-duty processing cycle. The principle of achieving super-resolution and crosstalk cancellation using this method has been elucidated and investigated. The non-iterative process eliminates the wavefront disorder of the iterative algorithm, and partitions combined with a binary phase mask eliminate crosstalk generated by spatial coherence and temporal sequence interference effects, thereby ensuring that the feature size of the spacing is in the subwavelength region. The efficiency of the Dc-PDLW is demonstrated by the production of a 3D large-area PB phase plate structure, which exhibits excellent diffraction efficiency and polarization sensitivity. Dc-PDLW exhibits remarkable 3D large-area optical phase encoding capabilities, which portend significant potential for applications in the domain of information encryption. It is particularly well-suited for inscribing meticulously designed phase encodings with nanoscale feature sizes and high efficiencies in a diverse array of materials. Concurrently, the minimum dual-pore spacing is anticipated to be diminished further, potentially through the deployment of larger NA objectives or the utilization of shorter processing wavelengths. The proposed method will facilitate further development of encrypted messages, computational holography, optical storage, and integrated photonics.

Methods

Sample preparation

In our experiments, commercially available Z-cut bulk sapphire wafers with dimensions of 10 × 10 × 0.2 mm (thickness) and full-side polishing were employed. For the fabrication of dual-pore structures, the laser energy was adjusted to a level slightly above the modification energy threshold of sapphire, inducing modification at a depth of 50 μm beneath the sapphire surface. Subsequent to modification, the upper surface of the sapphire was polished until the modified structure was completely exposed.

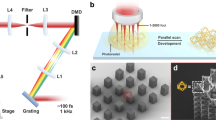

Ultrafast Laser Processing System

The experimental setup of the femtosecond laser processing system is illustrated in Figure S1. A femtosecond laser system (Pharos, Light Conversion Ltd.) with a pulse duration of 224 fs, a repetition rate of 10 kHz, and a central wavelength of 1030 nm was employed. The polarization of the laser beam was controlled by rotating a half-wave plate (HWP1). Subsequently, the phase hologram was loaded into the liquid crystal SLM (spatial light modulator, Hamamatsu LCOS X13138 series, reflection-type) in order to generate multiple focal spots with a nano-scale distance. A 4 f system was constructed by employing two lenses with focal lengths of 400 mm (L1) and 600 mm (L2), respectively. HWP2 coordinates the binary phase mask to achieve an orthogonal polarization state. Subsequently, the beam is focused 50 µm below the sapphire sample surface using an oil immersion objective with a numerical aperture (NA) of 1.25. A CCD camera was employed to assess the uniformity of the multifocal light spot. The sapphire samples were mounted on a 3D translation stage (SmarAct), which provides a positioning resolution of 1 nm.

Structural Characterization

After fabrication, the sapphire samples were preliminarily examined under an optical microscope (Olympus BX53M). The fine structures were further characterized through a SEM (scanning electron microscope, Zeiss), after polishing and etching (40% HF, 80 °C, 60 min). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis was performed simultaneously with the SEM measurements on the same region of the sample, enabling in-situ elemental composition characterization while acquiring structural information. The optical phase difference of dual-pore arrays were mearsured by quadriwave lateral shearing interferometry using a wavefront phase sensor (Phasics Sid4).

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Ouyang, Y.-H., Luan, H.-Y., Zhao, Z.-W., Mao, W.-Z. & Ma, R.-M. Singular dielectric nanolaser with atomic-scale field localization. Nature 632, 287–293 (2024).

Wang, Z. et al. 3D imprinting of voxel-level structural colors in lithium niobate crystal. Adv. Mater. 35, 2303256 (2023).

Gao, J. et al. Multi-dimensional shingled optical recording by nanostructuring in glass. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2306870 (2024).

Shi, X. et al. Dual-channel polarization-modulated metasurface. Results Phys. 58, 107545 (2024).

Ding, F. et al. Versatile polarization generation and manipulation using dielectric metasurfaces. Laser Photonics Rev. 14, 2000116 (2020).

Devlin, R. C., Ambrosio, A., Rubin, N. A., Mueller, J. P. B. & Capasso, F. Arbitrary spin-to–orbital angular momentum conversion of light. Science 358, 896–901 (2017).

Dregely, D. et al. 3D optical Yagi–Uda nanoantenna array. Nat. Commun. 2, 267 (2011).

Deng, Z.-L. et al. Diatomic metasurface for vectorial holography. Nano Lett. 18, 2885–2892 (2018).

Zhao, R. et al. Stereo Jones matrix holography with longitudinal polarization transformation. Laser Photonics Rev. 17, 2200982 (2023).

Zheng, G. et al. Metasurface holograms reaching 80% efficiency. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 308–312 (2015).

Wu, D. et al. Bioinspired fabrication of high-quality 3D artificial compound eyes by voxel-modulation femtosecond laser writing for distortion-free wide-field-of-view imaging. Adv. Optical Mater. 2, 751–758 (2014).

Xu, Q., Schmidt, B., Pradhan, S. & Lipson, M. Micrometre-scale silicon electro-optic modulator. Nature 435, 325–327 (2005).

Jeong, K.-H., Kim, J. & Lee, L. P. Biologically inspired artificial compound eyes. Science 312, 557–561 (2006).

Li, J. et al. Nanoscale multi-beam lithography of photonic crystals with ultrafast laser. Light.: Sci. Appl. 12, 164 (2023).

Sun, K. et al. Three-dimensional direct lithography of stable perovskite nanocrystals in glass. Science 375, 307–310 (2022).

Li, Z.-Z. et al. Super-stealth dicing of transparent solids with nanometric precision. Nat. Photonics 18, 799–808 (2024).

Datta, S., Clady, R., Grojo, D., Utéza, O. & Sanner, N. Scalable nanophotonic structures inside silica glass laser-machined by intense shaped beams. Laser Photonics Rev. 18, 2301365 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Precise mode control of laser-written waveguides for broadband, low-dispersion 3D integrated optics. Light Sci. Appl 13, 130 (2024).

Gissibl, T., Thiele, S., Herkommer, A. & Giessen, H. Two-photon direct laser writing of ultracompact multi-lens objectives. Nat. Photonics 10, 554–560 (2016).

Kawata, S., Sun, H.-B., Tanaka, T. & Takada, K. Finer features for functional microdevices. Nature 412, 697–698 (2001).

Wang, X.-J., Fang, H.-H., Li, Z.-Z., Wang, D. & Sun, H.-B. Laser manufacturing of spatial resolution approaching quantum limit. Light. Sci. Appl. 13, 6 (2024).

Xu, X. et al. Femtosecond laser writing of lithium niobate ferroelectric nanodomains. Nature 609, 496–501 (2022).

Yan, Z., Gao, J., Beresna, M. & Zhang, J. Near-Field mediated 40nm in-volume glass fabrication by femtosecond laser. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2101676 (2022).

Li, Z.-Z. et al. O-FIB: far-field-induced near-field breakdown for direct nanowriting in an atmospheric environment. Light. Sci. Appl. 9, 41 (2020).

Yamaji M., Kawashima H., Suzuki Ji, Tanaka S. Three dimensional micromachining inside a transparent material by single pulse femtosecond laser through a hologram. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 041116 (2008).

Shi, S. et al. Enhanced light-field image resolution via MLA translation. Opt. Express 31, 17087–17097 (2023).

Liu, Y., Zhu, J., Chen, C., Hou, X. & Wang, Y. Irradiance-tailoring integral-illumination polarization homogenizer based on anamorphic aspheric microlens arrays. Opt. Express 32, 26609–26631 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. High-throughput two-photon 3D printing enabled by holographic multi-foci high-speed scanning. Nano Lett. 24, 2671–2679 (2024).

Bengtsson, J. Kinoform design with an optimal-rotation-angle method. Appl Opt. 33, 6879–6884 (1994).

Qian, D. et al. Flexible and rapid fabrication of silver microheaters with spatial-modulated multifoci by femtosecond laser multiphoton reduction. Opt. Lett. 43, 5335–5338 (2018).

Huang, L. et al. Sub-wavelength patterned pulse laser lithography for efficient fabrication of large-area metasurfaces. Nat. Commun. 13, 5823 (2022).

Moser, S., Ritsch-Marte, M. & Thalhammer, G. Model-based compensation of pixel crosstalk in liquid crystal spatial light modulators. Opt. Express 27, 25046–25063 (2019).

Xu, K. et al. High-precision multi-focus laser sculpting of microstructured glass. Opto-Electron. Adv. 7, 240082 (2024).

Fienup, J. R. Phase retrieval algorithms: a comparison. Appl Opt. 21, 2758–2769 (1982).

Hasegawa, S. & Hayasaki, Y. Holographic Vector Wave Femtosecond Laser Processing. Int J. Optomechatronics 8, 73–88 (2014).

Hasegawa, S. & Hayasaki, Y. Polarization distribution control of parallel femtosecond pulses with spatial light modulators. Opt. Express 21, 12987–12995 (2013).

Chen, Z. et al. 25 nm-Feature, 104-aspect-ratio, 10mm2-area single-pulsed laser nanolithography. Nat. Commun. 16, 7434 (2025).

Asgari Sabet, R., Ishraq, A., Saltik, A., Bütün, M. & Tokel, O. Laser nanofabrication inside silicon with spatial beam modulation and anisotropic seeding. Nat. Commun. 15, 5786 (2024).

Zhang, G., Rudenko, A., Stoian, R. & Cheng, G. Ultrafast laser high-aspect-ratio extreme nanostructuring of glass beyond λ/100. Ultrafast Sci. 5, 0103 (2025).

Li Z.-Z. et al. Super-stealth dicing of transparent solids with nanometric precision. Nat. Photonics 18, 799–808 (2024).

Li, Z., Allegre, O. & Li, L. Realising high aspect ratio 10 nm feature size in laser materials processing in air at 800 nm wavelength in the far-field by creating a high purity longitudinal light field at focus. Light. Sci. Appl. 11, 339 (2022).

Stoian, R. Ultrafast laser volume nanostructuring; a limitless perspective. Adv. Opt. Technol. 12, 1237524 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Modulation of high-quality internal multifoci based on modified three-dimensional Fourier transform. Opt. Lett. 48, 900–903 (2023).

Malinauskas, M. et al. Ultrafast laser processing of materials: from science to industry. Light Sci. Appl 5, e16133–e16133 (2016).

Zhu, Y. et al. Realization of flexible and parallel laser direct writing by multifocal spot modulation. Opt. Express 29, 8698–8709 (2021).

Zhu, L. et al. Multifocal array with controllable polarization in each focal spot. Opt. Express 23, 24688–24698 (2015).

Leutenegger, M., Rao, R., Leitgeb, R. A. & Lasser, T. Fast focus field calculations. Opt. Express 14, 11277–11291 (2006).

Richards, B., Wolf, E. & Gabor, D. Electromagnetic diffraction in optical systems, II. Structure of the image field in an aplanatic system. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 253, 358–379 (1997).

Pozzi G. Chapter Seven - Fourier Optics. In: Advances in Imaging and Electron Physics (ed Pozzi G.). (Elsevier, 2016).

Zhu, Y., Zhao, W., Zhang, C., Wang, K. & Bai, J. Non-iterative multifold strip segmentation phase method for six-dimensional optical field modulation. Opt. Lett. 47, 1335–1338 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Non-interleaved shared-aperture full-stokes metalens via prior-knowledge-driven inverse design. Adv. Mater. 37, 2408978 (2025).

Lin, Z., Liu, H., Ji, L., Lin, W. & Hong, M. Realization of ∼10nm features on semiconductor surfaces via femtosecond laser direct patterning in far field and in ambient air. Nano Lett. 20, 4947–4952 (2020).

He, J. et al. An entropy-controlled objective chip for reflective confocal microscopy with subdiffraction-limit resolution. Nat. Commun. 14, 5838 (2023).

Di Francia, G. T. Super-gain antennas and optical resolving power. Il Nuovo Cim. (1943-1954) 9, 426–438 (1952).

Wang, H., Shi, L., Lukyanchuk, B., Sheppard, C. & Chong, C. T. Creation of a needle of longitudinally polarized light in vacuum using binary optics. Nat. Photonics 2, 501–505 (2008).

Zhu, L., Yang, R., Zhang, D., Yu, J. & Chen, J. Dynamic three-dimensional multifocal spots in high numerical-aperture objectives. Opt. Express 25, 24756–24766 (2017).

Waddie, A. J. & Taghizadeh, M. R. Interference effects in far-field diffractive optical elements. Appl Opt. 38, 5915–5919 (1999).

Hosseini, A., Kwong, D., Zhang, Y., Alu, A. & Chen, R. T. Modeling and experimental observation of an on-chip two-dimensional far-field interference pattern. Appl Opt. 50, 1822–1826 (2011).

Hayasaki, Y. & Hasegawa, S. Holographic vector-wave femtosecond laser processing. (SPIE, 2016).

Moreno, I., Davis, J. A., Hernandez, T. M., Cottrell, D. M. & Sand, D. Complete polarization control of light from a liquid crystal spatial light modulator. Opt. Express 20, 364–376 (2012).

Gaudfrin K., Lopez J., Gemini L., Hönninger C., Duchateau G. Laser-induced stress by multi-beam femtosecond pulses in fused silica. J. Appl. Phys. 135, 203109 (2024).

Juodkazis, S. et al. Laser-induced microexplosion confined in the bulk of a sapphire crystal: evidence of multimegabar pressures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 166101 (2006).

Juodkazis, S. et al. Control over the crystalline state of sapphire. Adv. Mater. 18, 1361–1364 (2006).

Pang, W.-B. et al. The effect of polarization light on optical imaging system. Acta Phys. Sin. 61, 234202–234202 (2012).

Beuton, R. et al. Thermo-elasto-plastic simulations of femtosecond laser-induced multiple-cavity in fused silica. Appl. Phys. A 124, 324 (2018).

Beuton, R. et al. Thermo-elasto-plastic simulations of femtosecond laser-induced structural modifications: application to cavity formation in fused silica. J. Appl. Phys. 122, 203104 (2017).

Bon, P., Maucort, G., Wattellier, B. & Monneret, S. Quadriwave lateral shearing interferometry for quantitative phase microscopy of living cells. Opt. Express 17, 13080–13094 (2009).

Gao, J. et al. Multi-dimensional shingled optical recording by nanostructuring in glass. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2306870 (2023).

Shimotsuma, Y., Kazansky, P. G., Qiu, J. & Hirao, K. Self-organized nanogratings in glass irradiated by ultrashort light pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 247405 (2003).

Sakakura, M., Lei, Y., Wang, L., Yu, Y.-H. & Kazansky, P. G. Ultralow-loss geometric phase and polarization shaping by ultrafast laser writing in silica glass. Light Sci. Appl 9, 15 (2020).

Lei, Y. et al. High speed ultrafast laser anisotropic nanostructuring by energy deposition control via near-field enhancement. Optica 8, 1365–1371 (2021).

Beresna, M. & Kazansky, P. G. Polarization diffraction grating produced by femtosecond laser nanostructuring in glass. Opt. Lett. 35, 1662–1664 (2010).

Sun, K. et al. Localized temperature engineering enables writing of heterostructures in glass for polarized photoluminescence of perovskites. ACS Nano 18, 6550–6557 (2024).

Chan, J. Y. E. et al. Full geometric control of hidden color information in diffraction gratings under angled white light illumination. Nano Lett. 22, 8189–8195 (2022).

Li, X., Lan, T.-H., Tien, C.-H. & Gu, M. Three-dimensional orientation-unlimited polarization encryption by a single optically configured vectorial beam. Nat. Commun. 3, 998 (2012).

Chen, Q. et al. Three-dimensional laser writing aligned perovskite quantum dots in glass for polarization-sensitive anti-counterfeiting. Adv. Optical Mater. 11, 2300090 (2023).

Feng, Y., Wang, R., Liu, C. & Huang, Y. Non-iterative phase-only modulation method for generating high-uniformity 3D multifocal spots with flexible position control. Opt. Commun. 547, 129812 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for Micro and Nano Fabrication Center of Zhejiang University providing facilities for SEM and EDS measurements. This work was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program [2024YFB4607403 (J.Q)], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Nos. 52432001 (J.Q)]; Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province [Nos. LDG25F050001 (J.Q)], “Pioneer” and “Leading Goose” R&D Pro-gram of Zhejiang [2023C03089 (J.Q)].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.J. and L.Z. conceived the idea. J.Q. organized, coordinated, and supervised the project. Z.J. performed the main experiments and collected the data. J.H. and Z.J. performed the theoretical simulations and calculations. J.Z., Y.Z., and W.Z. provided assistance in the process of generating SSP-BM holograms. J.H. provided assistance in SEM experiment and the birefringence measurement experiment. Z.J., L.Z., J.H., and J.Q. interpreted the results and proposed the mechanism of spatial coherence effect and temporal sequence interference. Z.J. wrote the manuscript. J.H., L.Z., W.Z., J.Z., and J.Q. discussed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Mark Hopkinson, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, Z., Hu, J., Zhong, L. et al. De-coherent parallel laser processing of ultradense nanopores for high-density, large-area 3D optical phase encoding. Nat Commun 17, 1070 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67828-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67828-9