Abstract

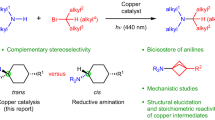

Nucleosi(ti)des and nucleic acids with N6 modified adenosine play an important role in the areas of disease diagnosis and treatment, biological chemistry, as well as nanotechnology. The conventional way to achieve N6 alkylation includes nucleophilic aromatic substitution reaction from N6 activated adenosine and direct reductive amination from adenosine. However, nucleophilic aromatic substitution reaction needs pre-functionalization of adenosine and reductive amination has limited alkyl substrate groups, especially not compatible with the secondary and tertiary alkyl groups. Herein, we develop a practical alkylation at the N6-position of adenines in adenosine and its analogues as well as late-stage functionalization of nucleotides/oligonucleotides through photoredox and copper co-catalyzed decarboxylative C(sp3)–N cross-coupling reaction. This method features simplicity and directness with various free radical precursors which is promising for medicinal and biological applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Modified nucleic acids (NAs) play a crucial role in regulating biological functions and activities, significantly impacting heredity, growth, and disease mechanisms1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. For instance, N6-methyladenosine (m6A), the most common internal modification in messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA), influences multiple aspects, including mRNA stability, translation, splicing regulation, and plays a key role in cell differentiation and immune response processes9,10,11. N6-isopentenyl adenosine (i6A) is a subset of transfer RNA (tRNAs) in bacteria and eukaryotes, improving the translation efficiency and accuracy12. Additionally, free i6A nucleoside is a component of a unique class of natural hormones—cytokinins, which serve as regulators for plant growth and differentiation13 (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, numerous chemically modified nucleoside analogues have been synthesized to enhance their properties. Among these, N6-functionalized adenine nucleoside analogues exhibit distinct bioactivities14,15,16, with several already on the market and more undergoing clinical or preclinical trials (Fig. 1a). Notably, Abacavir17, an adenosine analogue containing N6-cyclopropane, is an FDA-approved drug for treating human immunodeficiency virus D (HIV). ORIC-53318, also featuring a cyclopentyl group at the N6 position, is a highly potent and selective inhibitor of CD73 (ecto-5’-nucleotidase). It is currently in Phase III clinical trials for treating relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Cangrelor19, the only available intravenous P2Y12 platelet receptor antagonist, exhibits potent and rapidly reversible antiplatelet effects.

a Representative examples of bioactive N-alkylated purine nucleoside analogues and nucleic acids. b Selected examples of N6-alkylation of purine nucleosides. c Selected examples of late-stage N6 functionalization of purine in DNA/RNA. d Our strategy for late-stage functionalization of N6-alkylated nucleosides, nucleotides, and oligonucleotides with respectively unprotected adenosine. Me methyl, Et ethyl, Ac acetyl, dtbby 4,4’-Di-tert-butyl-2,2’-dipyridyl, Phen o-Phenanthroline, BTMG 2-(tert-butyl)−1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine, LED light-emitting diode, MES 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid.

Due to the significant bioactivities of these N6-alkylated adenosine compounds, substantial efforts have been made to develop these analogues20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. The nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) strategy has been employed to directly functionalize nucleosides from adenosine derivatives with C6 halogenated and C6-OH groups (see Supplementary Fig. 2)20. In addition, there are a few examples of SNAr reactions that start at the C6-NH2 position of adenosine, involving multiple steps under harsh conditions29. Compared to the traditional SNAr methods, using adenosine itself as the substrate is more economical and commercially available, since the former require halogenated nucleoside substrates or activated C6 substrates to react with alkylamine. There are several approaches for the N6 alkylation from adenosine itself (Fig. 1b): (1) Dimroth rearrangement (see Supplementary Fig. 3)21,22,23,24. As early as 1963, Robins group21 developed the indirect N6-alkylation of 2’-deoxyadenosine (dA), which firstly alkylated at the N1 position, followed by the Dimroth rearrangement to finally get the desired N6-substituted product; however, this approach is limited to active RX, such as MeI, BnBr. (2) Reductive amination (see Supplementary Fig. 4). In 1980, Leonard group25 established the reductive amination for the synthesis of N6-alkylated adenosine; however, this approach is limited to aldehyde substrates. Moreover, the acidic condition (pH 3.3-4.4) is not suitable for the dA substrate. (3) Radical approach (see Supplementary Fig. 5)26,27,28. In 2012, Qu and Guo group successfully developed direct N6 alkylation of protected adenosine derivatives with cycloalkane promoted by tBuOOtBu and CuI26. However, the protection of adenosine substrates and high temperature conditions are needed. In 2023, Kwon group engaged ozone to activate alkenes at −78 °C and successfully developed direct N6 methylation of adenosine and 2′-deoxyadenosine27. In 2024, Koh and Chen group reported a glycosyl radical-mediated N-glycosylation reaction using readily accessible glycosyl sulfone donors and N-nucleophiles under mild copper-catalyzed, photoredox-promoted conditions28. These N-nucleophiles included protected adenosine analogs.

Late-stage N6 alkylation of oligonucleotides or nucleic acids is more challenging due to reaction condition compatibility and different bases selectivity issues30,31,32,33. To be more specific, oligonucleotides cannot tolerate harsh conditions (e.g., Dimroth rearrangement’s strong bases); reductive amination preferentially occurs at the N2-position of guanine in oligonucleotides34; and previous radical approaches are too harsh for oligonucleotide modification. Indeed, examples of direct N6-alkylation of the adenosine skeleton in oligonucleotides or nucleic acids are scarce (see Supplementary Fig. 8)35,36,37,38,39. In fact, SNAr reactions have been applied for formal N6-alkylation (Fig. 1c). As early as 1991, Verdine group35 introduced N6-NHR groups into oligonucleotides using N6-OPh as a leaving group. Later, Kierzek group37 (2003) and Zhou group38 (2022) reported more practical SNAr methods using SOMe/SO2Me and iodine leaving groups, respectively. In 2021, Seo group39,40 achieved selective N6-arylation of adenine in oligonucleotides via SNAr. Meanwhile, Gillingham group (2012) used N–H insertion for catalytic alkylation of DNA and RNA41; this rhodium-catalyzed carbene transfer reaction showed high N-alkylation compared to O-alkylation selectivity but still produced O–H insertion byproducts.

Despite the above efforts, current N6 alkylation methods suffer from limitations: harsh conditions, lengthy steps, and narrow substrate scope—especially for late-stage adenosine N6 alkylation of oligonucleotides. Developing direct, efficient methods for N6-alkylation of nucleosi(ti)des and oligonucleotides under simple, mild conditions is thus a valuable extension of current research. Recently, radical decarboxylative strategies have shown high efficiency in carbon–nitrogen bond formation28,42,43,44,45,46.

In this work, continuing with our interest in the late-stage functionalization and biological study of nucleosi(ti)des and oligonucleotides47,48,49,50,51,52, we establish direct N6-alkylation of nucleosi(ti)de analogues via photoredox and copper co-catalyzed decarboxylative C(sp3)–N cross-coupling with N-Hydroxyphtalimide (NHPI) esters (Fig. 1d). We also achieve late-stage N6-alkylation of oligonucleotides in both DNA and RNA, which is useful in medical chemistry and chemical biology.

Results

Reaction development

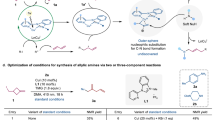

We investigated the N6-alkylation of unprotected 2’-deoxyadenosine 1a under several reported reaction conditions (see Supplementary Fig. 13)22,25,37,41,42. Among the approaches tested, only the Hu group’s synergistic photoredox combined with copper-catalyzed decarboxylative C–N cross-coupling method42, successfully produced the target N6-cyclohexyl deoxyadenosine (3a) in 7% yield. This was achieved using Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 (1 mol%) as the photoredox catalyst, CuBr (0.2 equiv.) as the metal catalyst, L1 as the ligand, Et3N (5.0 equiv.) as the base, and MeCN (0.1 M) as the solvent, under two 20 W blue LED irradiation at room temperature for 12 h (Table 1, entry 1).

To optimize conditions, considering the solubility of more polar 1a, firstly, we explored various solvents (see Supplementary Table 1). When the dry N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMA) was used as the solvent, the yield of 3a increased to 18% (Table 1, entry 2). We then screened different cuprous salts and their equivalents (see Supplementary Table 2). Replacing CuBr with Cu(MeCN)4PF6 improved the yield by 10% (Table 1, entry 3), and increasing its equivalent to 0.5 further boosted the yield to 50% (Table 1, entry 5). Next, we tested various photoredox catalysts (see Supplementary Table 3), confirming that Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 remained the most effective for this reaction among them. Similarly, when different bases were explored (see Supplementary Table 4), among them, Et3N was found to be the most suitable. We also tested different ligands and their equivalents, finding that the reaction could proceed without a ligand while maintaining the same yield (see Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). Reducing the equivalence of Et3N did not significantly affect the yield (Table 1, entry 5). Subsequently, we adjusted the reaction concentration, achieving a notable improvement in yield to 84% at 0.02 M (Table 1, entry 6). If the reaction time is extended to 20 h, the yield can be further increased to 91% (Table 1, entry 7).

We also conducted control experiments, which confirmed that both Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 and Cu(MeCN)4PF6 are essential for this N6 alkylation (see Supplementary Table 10). Building on this protocol and maintaining a reaction time of 12 h, we attempted the N6-alkylation of adenosine (1a’), but could only obtain a 60% yield of the target product 4a. Through ligand screening (see Supplementary Table 11), we found that using dibutyl phosphate (L2) improved the yield of 4a to 66%. Further increasing the equivalent of L2 to 1.5 equiv. resulted in an enhanced yield of 84% for the target product 4a (Table 1, entry 8). Based on previous reports42, a potential radical mechanism was proposed (see Supplementary Fig. 14).

Reaction scope

With the optimal conditions established, the substrate scope of this reaction was explored (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 22). Encouragingly, various primary alkyl NHPI esters proven to be suitable substrates, yielding the desired N6-alkylated products (3b–3i) in 32–88% yields. The N6-methylation of dA produced the desired products 3b (m6dA) and 3c (D3-m6dA), with the latter being a more valuable commodity ($380/mg)53. Furthermore, NHPI esters bearing functional groups such as bromo (2e), alkenyl (2f), alkynyl (2g), and aromatic scaffolds (2h and 2i) efficiently participated in the N6-alkylation, producing the corresponding products (3e–3i). Notably, product 3g, featuring an alkyne handle, could be further conjugated with a functionalized azide compound via a click reaction, which is of interest for biological or pharmaceutical applications.

a2’-deoxyadenosine (1.0 equiv.), NHPI ester (1.2 equiv.), Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 (1 mol%), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (50 mol%), and Et3N (2.5 equiv.) in dry DMA (0.05 M) on 0.2 mmol scale; irradiated by 20 W blue LED *2 at r.t. for 20 h; isolated yield. b1.5 equiv. dibutyl phosphate was added; irradiated by 20 W blue LED *2 at r.t. for 12 h. cthe equivalent of NHPI ester is increased to 2.4 equiv. d2’-deoxyadenosine (1.0 equiv.), 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)acetaldehyde (15.0 equiv.), NaBH3CN (6.0 equiv.), and acetic acid (1.0 M), 50 °C, 12 h; LC-yield. eAcetone was used instead of 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)acetaldehyde. fCyclopentanone was used instead of 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)acetaldehyde. Ph phenyl, Boc tert-butyloxy carbon, PyBA 1-pyrenebutyric acid.

The presence of acyclic substituted NHPI esters, such as isopropyl and isopentyl, was found to be conducive to the formation of N6-alkylated products (3j and 3k) in good yields (72% and 78%), and 3k was obtained as a 1:1 diastereomeric mixture. Cyclic substrates, including cyclobutyl (3m), cyclopentyl (3n), cyclohexyl (3a), cycloheptyl (3o), oxane (3p), and piperidine (3q) rings, afforded the corresponding alkylated products in yields ranging from 65 to 85%. However, the cyclopropyl system, used as a radical precursor, resulted in a product yield of only 8% (3l), despite extensive condition screening. This is probably due to the destabilization of the resulting cyclopropyl radical54.

For the tertiary alkyl redox-active ester, we found that the transformation was much more difficult than the primary and secondary cases, yielding lower product amounts. This is consistent with the significant steric hindrance effects observed in cross-coupling reactions42. The target product can be obtained with a better yield of 23% (3r) and 30% (3s) after doubling the equivalent of the NHPI ester. Additionally, complex substrates and functional groups can also be introduced to get desired N6-alkylated products in this system. To our delight, the substrate derived from N-Boc-protected amino acid can also be compatible, providing the desired product (3t) in an acceptable yield (42%). The substrates containing biotin (3u, 43%) and fluorescence (3v, 57%) functional groups can transfer into the desired product in reasonable yields, which may be further applied to biological research. This system also has good compatibility with steroid substrates (3w, 61%), which comes from the dehydrocholic acid. Notably, no multi-alkylated products (e.g., O-alkylated or bis N6-alkylated) were observed during the reaction, also highlighting the advantages of this method.

As a control, we utilized the reductive amination method, which is a traditional approach for introducing alkyl groups at the N6 position of adenosine and its analogs. This strategy is usually suitable for introducing primary alkyl groups. The 3h can also be produced through dA (1a) reacted with 2-(4-methoxyphenyl) aldehyde (2h’) in 40% yield, and yet 8% of ribose-cleaved byproduct is generated due to the acidic condition. However, reductive amination methodology is not suitable for the introduction of secondary and tertiary alkyl groups. Utilizing the corresponding ketone in reaction with 1a25, failed to yield the desired products (3j and 3n). Additionally, if a complex substrate, such as those listed in Fig. 2, is synthesized using reductive amination, the corresponding aldehydes are not as readily available as the corresponding carboxylic acids.

Subsequently, we explored a wide range of purine-based nucleosides (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 23). To our satisfaction, arabinofuranosyl purine nucleosides with 2-F, OMe, and O-methoxyethyl substitutions on the furan-sugar moiety, commonly used in RNAi drug research55,56,57,58,59, reacted efficiently to yield the corresponding N6-alkylated products (4b–4d) with satisfactory yields. For the bioactive substances Cordycepin60 and ddA61, the target products were obtained with yields of 89% (4e) and 82% (4f), respectively. Purine nucleosides with modifications at the 5′ position also performed well in this reaction system. For instance, a 5′-DMTr-protected substrate yielded the desired product (4g) with a 51% yield, while a 5′-Cl substituted adenosine analogue produced the desired product (4h) with an 85% yield. Satisfying results were also obtained from acetyl group-protected adenosine (4i, 69%) and 2′,3′-O-isopropylidene adenosine (4j, 85%). We then investigated the compatibility of the reaction with respect to C8 position-substituents. Functional groups, such as methyl, bromide, and phenyl groups at the C8 position, were well-tolerated, resulting in products 4k–4m. However, no desired products 4n were observed when C2-substituted analogues were used as substrates. Furthermore, aza- and deaza-analogues of adenosine also underwent the reaction successfully, providing acceptable to good yields (4o–4r, 48–82%). The late-stage modification of purine-based drugs is particularly appealing, as it may offer a straightforward and efficient approach to drug discovery. Encouragingly, our reaction proceeded efficiently with further modifications of existing drug molecules, such as the Vidarabine (anti-HSV agent)62, the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (a second messenger involved in cell migration, activation, proliferation, and survival)63, the Adefovir dipivoxil (anti-HBV)64, the Remdesivir (anti-COVID-19)65, and the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) (Oxidative Coenzyme I)66, yielding the corresponding alkylation products with good to high yields (4s–4w, 38–86%). Moreover, above-metioned SNAr approach is also be tried. This method starts from adenosine, whose C6-NH2 is directly converted into a triazol group as an active site for reacting with an alkylamine29. This approach is proven incompatible with thermally labile adenosine derivatives. Such as the Cordycepin (1e), ddA (1f), Adefovir dipivoxil (1u) and, Remdesivir (1v), they exhibited the generation of a large number of glycosidic bond cleavage products during intermediate preparation due to prolonged heating (intermediate: 4ea, 9%; 4fa, N.D.; 4ua, N.D.; 4va, N.D.).

aGeneral conditions: adenosine analogue (1.0 equiv.), NHPI ester (1.2 equiv.), Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 (1 mol%), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (50 mol%), and Et3N (2.5 equiv.) in dry DMA (0.05 M) on 0.2 mmol scale; irradiated by 20 W blue LED *2 at r.t. for 20 h; isolated yield. badenosine analogue (1.0 equiv.), NHPI ester (1.2 equiv.), Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 (1 mol%), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (50 mol%), dibutyl phosphate (1.5 equiv.), and Et3N (2.5 equiv.) in dry DMA (0.05 M) on 0.2 mmol scale; irradiated by 20 W blue LED *2 at r.t. for 12 h; isolated yield. cadenosine analogue (1.0 equiv.), NHPI ester (1.2 equiv.), Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 (1 mol%), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (50 mol%), dibutyl phosphate (1.5 equiv.), H2O (150.0 equiv.) and Et3N (4.0 equiv.) in DMA (0.05 M) on 0.2 mmol scale; irradiated by 20 W blue LED *2 at r.t. for 12 h; isolated yield. dAdenosine analogue (1.0 equiv.), TMSCl (4.0 equiv.), BDMAMH·2 HCl (3.5 equiv.) in pyricdine (1 mL, 0.15 M) on 0.15 mmol scale, stirred for 24 h at 100 °C. The mixture was cooled to r.t., TMSCl (3.4 equiv.) was added and stirring was continued for 15 min. 4ea 6-(1,2,4-triazol-4-yl)purine cordycepin, 4fa 6-(1,2,4-triazol-4-yl)purine ddA, 4ua 6-(1,2,4-triazol-4-yl)purine adefovir dipivoxil, 4va 6-(1,2,4-triazol-4-yl)purine Remdesivir, DMTr 4,4′-dimethoxytrityl, HSV herpes simplex virus, HBV hepatitis B virus, COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019.

While there has been growing interest in dinucleoside monophosphate drug development, reports on the late-stage functionalization of these compounds are limited due to reactivity and selectivity concerns48,67. To our delight, our protocol proven effective not only for the deoxy-dinucleoside monophosphate dApT (5a) but also for the dinucleoside monophosphates ApU (5e) (Fig. 4). Additionally, it demonstrated compatibility with various NHPI esters (2a, 2d, and 2e). N6-alkylation of these dinucleoside monophosphates resulted in the desired alkylated products (6aa–6ac, 6e; 44–69%) without affecting the thymine or uracil. Alkylation reactions of dApC (5b), dCpA (5c), dApG (5d), and ApC (5f) have also been conducted. Under the general reaction conditions, only ApC (5f) afforded monosubstituted alkylated products with a yield of 3%, while no target products were detected for the other substrates (see Supplementary Table 24).

Applications of the methodology

After confirming the broad substrate scope and compatibility with various functional groups in purine nucleosides, we expanded our methodology to the modification of complex nucleosides and nucleotides (Fig. 5). When the reaction of compounds 1a and 2a was scaled up to 1.0 mmol, the desired product 3a was obtained with an isolated yield of 78%, which opened up possibilities for further expansion (Fig. 5a). DNA solid-phase synthesizers are commonly used for synthesizing modified oligonucleotides using modified nucleoside phosphoramidite. Since the DMTr-dA phosphoramidite was found to be incompatible with this alkylation process, the 5’-DMTr-protected compound 4g was straightforwardly converted into the modified nucleoside phosphoramidite 7 (Fig. 5b)68,69. After attempting to optimize the conditions, we found it difficult to achieve N6-alkylation for AMP, ADP and ATP by using our method (see Supplementary Tables 19, 20, and 21), but protection of one of the phosphate hydroxyl groups with a cyanoethyl (OCE) group (8)70 allowed the successful synthesis of the target product 8a with a yield of 61%. A subsequent simple deprotection step yielded the N6-alkylated AMP product 8aa (Fig. 5b). Additionally, our products can be further modified using other methodologies. The alkylated adenosine (9) was explored for further modifications. It served as a substrate for C8 arylation71,72 and C2 borylation49, producing the target products with yields of 30% (10) and 41% (11), respectively. Modified nucleoside acids play an important role in drug development and bio-imaging applications. By utilizing click chemistry73, compound 3g, which possesses an alkyne handle, was bioconjugated with the azide group of Zidovudine74, an HIV-1 medication, resulting in the formal dinucleoside 13 with an impressive yield of 98% (Fig. 5c). Furthermore, compound 3g also reacted with coumarin 12 (which contains an azide group), yielding the fluorescent compound 14 in 82% yield. Covalent crosslinking of DNA strands has been demonstrated as an effective strategy to enhance the thermal stability of DNA origami structures, facilitating higher-temperature self-assembly75,76,77. We applied our method to link two adenosines with an alkyl chain, successfully obtaining the alkylated di-adenosine product 3x in 72% yield (Fig. 5e). This experiment could serve as a basic concept for the covalent crosslinking of DNA.

a 1.0 mmol scale synthesis of alkylated nucleoside. b Functionalization of alkylated product to form phosphoramidite reagent and alkylated adenosine monophosphate. c Synthetic transformations to form arylated product and borylated product. d Bioconjugation with Zidovudine and fluorescent compound 12 via click reaction. e Link two deoxyadenosine with alkylation. iPr isopropyl, tBu tert-butyl, DMAP 4-dimethylaminopyridine, TBTA tris((1-benzyl-4-triazolyl)methyl)amine, DMF N, N-dimethylformamide.

Alkylation of ssDNA/RNA oligonucleotides

After successfully applying this method to dApT (5a), our next focus was the late-stage functionalization of ssDNA and RNA oligonucleotides (Table 2). While high selectivity between adenine and thymidine/uracil has been demonstrated in the dinucleoside monophosphate system (Fig. 4), reactivity issues may arise when oligonucleotides are used as substrates. This is primarily because the scale of oligonucleotides is much lower compared to standard conditions (0.4 × 10−3 mmol vs. 0.2 mmol)78, which can lead to reduced reactivity and potentially lower yields under these conditions. This challenge requires optimization to maintain efficiency when scaling the method to oligonucleotide substrates, ensuring that functionalization can still proceed effectively at lower amounts and concentrations.

When dApT (5a) was used as a substrate and the reaction was scaled down from 0.2 mmol to 400 nmol, no target product was detected at the lower amount and concentration (0.2 mmol, 20 mM vs. 400 nmol, 6.7 mM) (see Supplementary Table 35, entry 1). Upon increasing the equivalents of the reagents respectively (NHPI ester, Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2, Cu(MeCN)4PF6, dibutyl phosphate, and Et3N), no product was detected under most conditions, except for entry 5, where only trace amounts of the target product were observed (see Supplementary Table 35 and entries 2–5). On this basis, by incrementally increasing the equivalents of individual reagents, a significant enhancement in the yield of product 6c was achieved by increasing the amount of Et3N. When the amount of Et3N was raised from 12.5 equivalents to 20 equivalents, the yield of the target product reached 58% (see Supplementary Table 35 and entry 6). Further increases in Et3N led to higher yields, and an optimal condition was found with 27 equivalents of Et3N, resulting in a yield of 71% (see Supplementary Table 35 and entry 8). The optimal reaction conditions were listed as follows: dApT (5a) (400 nmol), NHPI ester (6.0 equiv.), Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 (5 mol%), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (2.5 equiv.), dibutyl phosphate (7.5 equiv.), Et3N (27.0 equiv.), and dry DMA (60 μL, 6.7 mM). Furthermore, control experiments demonstrated the importance of Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2, Cu(MeCN)4PF6, dibutyl phosphate, and Et3N in the reaction system. Both Cu(MeCN)4PF6 and Et3N were found to be indispensable for the reaction. Omitting either of them resulted in the accumulation of excess 5a, with no product 6c formation (see Supplementary Table 35 and entries 11, 13). When Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 or dibutyl phosphate was excluded, there was a notable decrease in the yield of 6c, with the yield dropping to 41% and 19%, respectively (see Supplementary Table 35, entries 10 and 12).

With the optimized method, the application to DNA oligonucleotides was further verified. Firstly, ODNs 2, 6, and 7 (3nt) and ODN 10 (5 nt), which feature adenosine bases positioned at different sites (5’, inside, and 3’), were subjected to the reaction. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis revealed that the desired N-alkylated product was obtained with yields ranging from 57% to 73% (Table 2, entries 3, 7, and 8). Additionally, DNA oligonucleotides of varying lengths (ODN 7, 9, 12, and 14) were tested, and the target product was successfully obtained with good to excellent yields (54–63%). Attempts have also been made on sequences containing two adenine (A) residues (see Supplementary Table 37, ODN 17, ODN 18). Notably, only two monosubstituted products has been observed, with no formation of disubstituted products detected. The total yields of the monosubstituted products for these two sequences are 71% and 55%, respectively. The underlying mechanism remains unclear and requires further investigation.

The optimized method has also proven effective for RNA oligonucleotides. When using ApU (5e) and ON 1 as substrates, the target products were achieved with yields of 75% and 51%, respectively (Table 2 and entries 16, 17).

However, a decline in yield was observed when the single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) oligonucleotides contained cytosine or guanine bases. The ODN 4 (3 nt), which contains adenine and cytosine, produced an alkylated adenine yield of 34% (Table 2, entry 5). Longer substrate has also been attempted, the ODN 13 (6nt), which also increases the distance between cytosine and adenine, did not lead to a significant increase in alkylation at adenine, with the yield remaining at 35% (Table 2 and entry 14). Similarly, when ODN 2, which contains adenine and guanine, was used, only a 9% yield of the desired product was obtained. Adjusting the spatial arrangement of guanine and adenine or reducing the proportion of guanine in the overall base composition (ODN 3, 3 nt, ODN 11, 5 nt, and ODN 8, 4 nt) did not improve the yield, which remained around 10% (Table 2, entries 4, 12, and 9). This reduction in yield may be attributed to the relatively low solubility of guanine and cytosine in dry DMA or the potential interference caused by the exposed amine groups of these bases.

The product and the site of reaction were further confirmed by the high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), the matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization Fourier transform mass spectrometry (MALDI-FTMS), and MALDI-MS/MS (see Supplementary Fig. 76). Additionally, an enzymatic hydrolysis experiment was conducted, further supporting the results and confirming the product’s structure (see Supplementary Fig. 77). These analytical methods provided strong evidence for the successful alkylation and the precise location of the modification within the oligonucleotides.

Anti-viral test

Nucleoside analogs (NAs) are synthetic compounds derived from natural nucleosides, widely employed as therapeutic agents with a well-documented history in the management of viral infections16,79. The adenosine skeleton is present in several established antiviral drugs16, indicating that this structural framework may confer antiviral activity. Consequently, we have investigated the efficacy of our synthesized compounds. Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), a member of the Rhabdoviridae family, is a negative-strand RNA virus with a compact 11.2 kb genome encoding five genes (N, P, M, G, and L)80. Its compact genome and well-characterized biology make VSV an ideal model for evaluating the antiviral activity of our compounds. To assess viral infection, we utilized a modified VSV expressing green fluorescent protein (VSV-GFP), with infected cells identified by fluorescence microscopy. Among our synthesized compounds, compounds 3a and 3q demonstrated antiviral activity at a concentration of 10 μM. To our knowledge, they have not been reported to be synthesized before. Compound 3a exhibiting greater potency than compound 3q (see Fig. 6). The difference in antiviral potency may be due to the greater steric hindrance in 3q. This steric hindrance likely impedes the incorporation of 3q into the viral genome, resulting in less effective termination of viral chain elongation and thus higher levels of viral infection, as suggested by previous studies81.

Anti-VSV activity of alkylated adenosine analogues 3a and 3q by immunofluorescence staining. Quantification data of virus infection are listed on the upper left corner of the Merge image. Scale bars are 10 μm. A representative result from 3 independent experiments with similar results is shown. Primary antibody: GFP (abcam #ab290), dilution: 1:500; Secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor™ 488 (invitrogen #A-11008), dilution: 1:5000.

Discussion

Modified nucleic acids are essential for regulating biological functions and activities, influencing genetic processes, organismal growth, and disease mechanisms. These modifications are of significant importance in pharmaceutical chemistry, chemical biology, biotechnology, and related fields1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. The introduction of functional groups into nucleobases has traditionally relied on labor-intensive de novo chemical synthesis. However, recent advancements in late-stage functionalization of nucleosides, nucleotides, and oligonucleotides have emerged as a promising alternative. Notably, N6-position alkylation of adenosine and its analogues has garnered considerable attention, with numerous nucleoside-based drugs incorporating such alkyl modifications (Fig. 1a)14,15,16,17. Furthermore, N6-alkylation modifications have been observed in DNA/RNA, such as the N6-methyladenosine (m6A), which is the most common internal modification in mRNA. These modifications modulate mRNA stability, translation, splicing regulation, and other key biological processes9,10,11. We therefore propose that developing a method for site-specific introduction of diverse alkyl groups at the N6 position of adenine holds substantial application potential, as the resulting alkylated nucleosides, nucleotides, and oligonucleotides are promising candidates for advancing nucleic acid-related research and applications.

While several methods have been developed for synthesizing N6-alkylated adenosine derivatives from nucleosides, they suffer from limited substrate scope and typically require multi-step synthesis to access the target products. In contrast, our proposed method addresses these limitations with notable advancements, which will be elaborated in detail below.

1) We attempted to use the reductive amination25 to introduce the 2-(4-methoxyphenyl) aldehyde (2h′), a primary alkyl group, to N6 of dA (1a), but only obtained 40% of the 3h. Compared to the 61% yield obtained by our method, it is much lower. Moreover, in this reductive amination reaction, the glycosidic bond of dA (1a) was broken due to the acidic condition, resulting in 8% of by-product. Additionally, reductive amination cannot introduce secondary alkyl groups at the N6 position, let alone those tertiary ones. We also attempted to use the acetone and cyclopentanone to react with dA (1a), but did not produce the target 3j and 3n. That further distinguished our approach from the reductive amination. Our method can introduce secondary alkyl groups (3a, 3j–3q) with a yield of up to 85% and tertiary alkyl groups with a yield of 23 and 30% (3r and 3s). Among them, the challenging cyclopropane can also be late-stage modified in a NOT trace amount. The introduction of those primary alkyl groups with complex structures on the other end has also been achieved (3t–3w). If reductive amination is used to synthesize these products, the corresponding aldehyde is not comparatively commercially available and there is also a possibility of incompatibility between substrates and this reaction (Fig. 2).

2) We also conducted control experiments using SNAr29. This approach can produce the secondary-alkyl-substituted products at C6. It starts from adenosine and its analogues, converting their C6-NH2 directly into C6-triazole, obtaining the intermediates. Then, alkylamines substitute the triazole via SNAr, generating N6-alkyl substituted products. However, this method has the limitation of long-term heating (100 °C, 24 h) during the generation of intermediates. Such harsh conditions are not friendly to thermally unstable substrates, such as the Cordycepin (1e), the ddA (1f), the Adefovir dipivoxil (1u), and the Remdesivir (1v). The yield of intermediate 4ea was 9%, and the rest did not observe the target intermediate. These four substrates were basically consumed, and were accompanied by the generation of decomposed products due to heating under alkaline conditions. It is gratifying that our conditions are mild and compatible with these heat-unstable substrates, producing the target products with excellent yields of 89% (4e), 82% (4f), 52% (4u), and 85% (4v), respectively (Fig. 3).

3) There are also other approaches that do not start from natural nucleoside substrates. For example, nucleoside analogues whose C6 position are modified by -Cl (C6-chloropurine nucleosides) or -OH (Inosine analogues) (see Supplementary Fig. 2). Utilizing these kinds of nucleosides as starting material to obtain the N6 alkyl substituted products tends to be less efficient, because they do not start from natural nucleoside substrates and usually need multiple reaction steps. Moreover, the number of commercially available analogues of these substrates is limited. In such cases, constructing a compound library for drug screening becomes a labor-intensive task with repetitive steps. However, for our method, as shown in the Fig. 3, we presented more than twenty alkylated analogues (4a–4w) in total with conversion rates range from 34 to 89%. The vast majority of these are commercially available.

Our method has also demonstrated wide compatibility. The Fig. 3 shows the results of late-stage modified drugs or bioactive compounds (4s–4w, 38–85%). This is all synthesized through our one-step method, not from scratch. When it is necessary to construct a library that introduces different functional groups at the N6 position of such complex substrates, our method will further demonstrate its superiority. We also conducted an initial anti-viral test using a library composed of our products, and the 3a and 3q showed obvious activities (Fig. 6).

Figure 5 illustrates some applications of our method. In the 1.0 mmol scale-up experiment, the yield remained high (78%), suggesting its potential for industrial mass production. N6-alkylated AMP was obtained using the OCE group. Combining results from alkylated cAMP (4t) and oligonucleotides, we conclude that our approach can alkylate phosphate-containing substrates, requiring the substitution of at least one hydroxyl of the phosphate group. The alkylated products generated by our method can serve as starting materials for subsequent reactions, thereby enhancing their utility and expanding the range of potential applications. These attempted reactions include the introduction of phosphoramidite groups68,69 (7, 65%), C8 arylation71,72 (10, 30%), C2 borylation49 (11, 41%), and click reactions73 (13, 98%; 14, 82%). There is also a promising application for DNA origami, where the double headed NHPI ester (2x) can link two dA and obtain the target product 3x with a yield of 72%.

Furthermore, we aim to expand the substrate scope to ssDNA/RNA oligonucleotides, which would eliminate the need for de novo synthesis from phosphoramidites to introduce modifying groups at the N6 position of adenine. Aforementioned expansion presents a challenge to the adaptability of the alkylation method. Unlike nucleosides, oligonucleotides are more complex substrates due to their composition of multiple nucleotides, which introduces several reaction sites and phosphate groups. Firstly, we tried the alkylating dinucleoside monophosphates, which can be considered as the simplest oligonucleotides. As shown in Fig. 4, the target product (6aa–6ac, 6e) can be obtained with a yield of 44–64%. This reaction has high selectivity and reacts at the N6 position of adenine, instead of thymine or uracil. Various alkyl groups were also introduced.

Beyond that, oligonucleotide reactions typically involve lower quantities and more dilute concentrations. Through a series of optimization steps, we identified favorable reaction conditions, achieving a maximum yield of approximately 70% of N6-alkylated adenine in oligonucleotides (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 36). However, the presence of cytosine and guanine bases in the oligonucleotide sequence leads to a decrease in yield. Although there is still a certain amount of product generated in the end, it needs to be improved in the future.

In conclusion, we have successfully developed a photoredox and copper co-catalyzed N6-alkylation of unprotected purine nucleosides with NHPI esters as nucleophilic radical precursors. This late-stage functionalization method could achieve a series of purine analogues, including different kinds of drugs, complex nucleoside substrates, and dinucleoside monophosphates. In addition, this catalytic N6-alkylation process offers a powerful strategy for the labeling and modification of DNA oligonucleotides. We believe that our approach will facilitate its potential application in nucleoside/nucleotide drug development, tailoring of DNA architectures, and the labeling of DNA oligonucleotides for biological study or therapeutic applications.

Methods

General procedure for the N6 Alkylation of Nucleoside

A 25 mL Schlenk tube containing a Teflon stir bar was charged with nucleoside (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), NHPI ester (0.24 mmol, 1.2 equiv.), Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 (0.002 mmol, 0.01 equiv.), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (0.1 mmol, 0.5 equiv.), and Et3N (0.5 mmol, 2.5 equiv.) in 10 mL dry DMA. The Schlenk tube was sealed with a rubber plug and taped, utilizing the freeze-pump-thaw (FPT) method for deaeration. The reaction system was exposed to 2 × 20 W LED light for 20 h, monitoring the progress of the reaction by thin layer chromatography (TLC) (Dichloromethane (DCM)/MeOH = 5/1 or 10/1) or the liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

The mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure, and the crude product was purified by column chromatography (C18 Spherical silica) using MeOH/H2O as an eluent to give the pure product. NOTICE: Cu(MeCN)4PF6 MUST be newly purchased. The Cu(MeCN)4PF6 should be a white dry powder. If its color changes (e.g., yellowing) or becomes damp, it should not be used.

General procedure for microscale N6 alkylation of dinucleoside monophosphate substrates

For a better understanding, you can read Chapter 8 of the Supplementary Information.

Firstly, preparing solutions of the dinucleoside monophosphate (20 mM), mixed solution of NHPI ester (294.8 mM, 410 μL) and Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 (11.6 mM, 90 μL), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (97.8 mM), dibutyl phosphate (599 mM), and Et3N (1744 mM). They are dissolved in the anhydrous DMA (these solutions need to be prepared in a glove box, and the anhydrous DMA needs to be bubbled using Ar).

Then, the 20 µL of dinucleoside monophosphate solution (400 nmol, 1 equiv.), the 10 µL of mixed solution of NHPI ester and Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 (6.0 equiv. and 0.05 equiv.), the 10 µL of Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (2.5 equiv.), the 10 µL of dibutyl phosphate (7.5 equiv.), and the 10 µL of Et3N (27.0 equiv.) were sequentially transferred into a 5 mL Schlenk tube (containing a Teflon stir bar) using a pipette. The Schlenk tube was sealed with a rubber plug and taped.

The freeze-pump-thaw (FPT) method was utilized for deaeration. In that operation, the liquid nitrogen and argon are employed. Pay attention to safety when using liquid nitrogen and argon, and keep the Schlenk line in a state of blowing argon when thawing, which is to maintain atmospheric pressure and an inert gas atmosphere.

Next, the reaction mixture is exposed to a 10 W blue light. The time from adding various solutions to being exposed to bule LED should not exceed about 5 minutes. It uses running water for cooling. The temperature of the reaction should NOT be lower than 25 degrees Celsius and should be kept constant.

The yield and recovery of the reaction was detected by LC-MS (see the Supplementary Information for specific analysis method).

General procedure for microscale N6 alkylation of RNA/DNA Oligonucleotides

Firstly, the substrate needs to be pretreated. RNA/DNA Oligonucleotide was dissolved in the DEPC water, transferred to a Schlenk tube (20 μL ×3 times), and lyophilized to obtain a freeze-dried oligonucleotide. These steps are making sure that the oligonucleotide is dry and a full dose of oligonucleotide is transferred to the reaction system.

Then, preparing solutions of mixed solution of NHPI ester (294.8 mM, 410 μL) and Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 (11.6 mM, 90 μL), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (97.8 mM), dibutyl phosphate (599 mM), and Et3N (1744 mM). They are dissolved in the anhydrous DMA (these solutions need to be prepared in a glove box, and the anhydrous DMA needs to be bubbled using Ar).

Next, the 20 µL of dry DMA, the 10 µL of mixed solution of NHPI ester and Ru(bpy)3(PF6)2 (6.0 equiv. and 0.05 equiv.), the 10 µL of Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (2.5 equiv.), the 10 µL of dibutyl phosphate (7.5 equiv.), and the 10 µL of Et3N (27.0 equiv.) were sequentially transferred into a 5 mL Schlenk tube (containing Oligonucleotide and a Teflon stir bar) using a pipette. The Schlenk tube was sealed with a rubber plug and taped.

The freeze-pump-thaw (FPT) method was utilized for deaeration. In that operation, the liquid nitrogen and argon are employed. Pay attention to safety when using liquid nitrogen and argon, and keep the Schlenk line in a state of blowing argon when thawing, which is to maintain atmospheric pressure and an inert gas atmosphere.

Finally, the reaction mixture is exposed to a 10 W blue light. The time from adding various solutions to being exposed to bule LED should not exceed about 5 minutes. It uses running water for cooling. The temperature of the reaction should NOT be lower than 25 degrees Celsius and should be kept constant.

The yield and recovery of the reaction was detected by LC-MS (see the Supplementary Information for specific analysis method).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Details about materials and methods, experimental procedures, mechanistic studies, and NMR spectra are available in the Supplementary Information, and from the corresponding author(s) upon request. The information of the oligonucleotide sequence is available in the Supplementary Dataset 1.

References

Egli, M. et al. Nucleic Acids in Chemistry and Biology (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2006).

Chen, K., Zhao, B. S. & He, C. Nucleic acid modifications in regulation of gene expression. Cell Chem. Biol. 23, 74–85 (2016).

Frye, M., Jaffrey, S. R., Pan, T., Rechavi, G. & Suzuki, T. RNA modifications: what have we learned and where are we headed?. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 365–372 (2016).

Chen, Y. et al. Epigenetic modification of nucleic acids: from basic studies to medical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 2844–2872 (2017).

Harcourt, E. M., Kietrys, A. M. & Kool, E. T. Chemical and structural effects of base modifications in messenger RNA. Nature 541, 339–346 (2017).

Ivancová, I., Leone, D.-L. & Hocek, M. Reactive modifications of DNA nucleobases for labelling, bioconjugations, and cross-linking. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 52, 136–144 (2019).

Hofer, A., Liu, Z. J. & Balasubramanian, S. Detection, structure and function of modified DNA bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 6420–6429 (2019).

McKenzie, L. K., El-Khoury, R., Thorpe, J. D., Damha, M. J. & Hollenstein, M. Recent progress in non-native nucleic acid modifications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 5126–5164 (2021).

Huang, H., Weng, H. & Chen, J. The biogenesis and precise control of RNA m6A methylation. Trends Genet. 36, 44–52 (2020).

He, P. C. & He, C. m6A RNA methylation: from mechanisms to therapeutic potential. EMBO J. 40, e105977 (2021).

Zaccara, S., Ries, R. J. & Jaffrey, S. R. Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 608–624 (2019).

Lin, X.-N., Gai, B.-X., Liu, L. & Cheng, L. Advances in the investigation of N6-isopentenyl adenosine i6A RNA modification. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 110, 117838 (2024).

Shaw, G. Chemistry of Adenine Cytokinins (CRC Press, 1994). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781351071284.

Jacobson, K.A. et al. Modified nucleosides. In Modified Nucleosides as Selective Modulators of Adenosine Receptors for Therapeutic Use (eds Herdewijn, P.) 433–449 (WILEY-VCH, 2008).

Shelton, J. et al. Metabolism, biochemical actions, and chemical synthesis of anticancer nucleosides, nucleotides, and base analogs. Chem. Rev. 116, 14379–14455 (2016).

Seley-Radtke, K. L. & Yates, M. K. The evolution of nucleoside analogue antivirals: A review for chemists and non-chemists. Part 1: early structural modifications to the nucleoside scaffold. Antiviral Res. 154, 66–86 (2018).

Yuen, G. J., Weller, S. & Pakes, G. E. A review of the pharmacokinetics of abacavir. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 47, 351–371 (2008).

Rodriguez, C. et al. Preliminary results of the oral CD73 inhibitor, oric-533, in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM). Blood 142, 4761–4762 (2023).

De Luca, L., Steg, P. G., Bhatt, D. L., Capodanno, D. & Angiolillo, D. J. Cangrelor: clinical data, contemporary use, and future perspectives. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10, e022125 (2021).

Lakshman, M. K. Base modifications of nucleosides via the use of peptide-coupling agents, and beyond. Chem. Rec. 23, e202200182 (2022).

Jones, J. & Robins, R. K. Purine nucleosides. III. Methylation studies of certain naturally occurring purine nucleosides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 85, 193–201 (1963).

Robins, M. J. & Trip, E. M. Nucleic acid related compounds. 6. Sugar-modified N6-(3-methyl-2-butenyl) adenosine derivatives, N6-benzyl analogs, and cytokinin-related nucleosides containing sulfur or formycin. Biochemistry 12, 2179–2187 (1973).

Schiffers, S. et al. Quantitative LC-MS provides no evidence for m6dA or m4dC in the genome of mouse embryonic stem cells and tissues. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 11268–11271 (2017).

Buter, J. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis releases an antacid that remodels phagosomes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 889–899 (2019).

Sattsangi, P. D., Barrio, J. R. & Leonard, N. J. 1,N6-Etheno-bridged adenines and adenosines. Alkyl substitution, fluorescence properties, and synthetic applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102, 770–774 (1980).

Xia, R., Niu, H.-Y., Qu, G.-R. & Guo, H.-M. CuI controlled C–C and C–N bond formation of heteroaromatics through C(sp3)–H activation. Org. Lett. 14, 5546–5549 (2012).

He, Z., Moreno, V., Swain, M., Wu, J. & Kwon, O. Aminodealkenylation: ozonolysis and copper catalysis convert C(sp3)–C(sp2) bonds to C(sp3)–N bonds. Science 381, 877–886 (2023).

Sun, Q. et al. N-glycoside synthesis through combined copper- and photoredox-catalysed N-glycosylation of N-nucleophiles. Nat. Synth. 3, 623–632 (2024).

Robins, M. J., Miles, R. W., Samano, M. C. & Kaspar, R. L. Syntheses of puromycin from adenosine and 7-deazapuromycin from tubercidin, and biological comparisons of the 7-aza/deaza pair. J. Org. Chem. 66, 8204–8210 (2001).

Stetsenko, D. A. & Gait, M. J. Oligonucleotide synthesis. In Chemical Methods for Peptide–Oligonucleotide Conjugate Synthesis (ed. Herdewijn, P.) 205–224 (Humana Press, 2004).

Yu, Y. & Wang, W. Post-synthetic chemical functionalization of oligonucleotides. Curr. Org. Synth. II. 9, 463–493 (2014).

Lechner, V. M. et al. Visible-light-mediated modification and manipulation of biomacromolecules. Chem. Rev. 122, 1752–1829 (2021).

Ito, Y. & Hari, Y. Synthesis of nucleobase-modified oligonucleotides by post-synthetic modification in solution. Chem. Rec. 22, e202100325 (2022).

Bhoge, B. A., Mala, P., Kurian, J. S., Srinivasan, V. & Saraogi, I. Selective functionalization at N2-position of guanine in oligonucleotides via reductive amination. Chem. Comm. 56, 13832–13835 (2020).

Ferentz, A. E. & Verdine, G. L. Disulfide-crosslinked oligonucleotides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113, 4000–4002 (1991).

Goodwin, J. T. & Glick, G. D. Synthesis of a disulfide stabilized RNA hairpin. Tetrahedron Lett. 35, 1647–1650 (1994).

Kierzek, E. & Kierzek, R. The thermodynamic stability of RNA duplexes and hairpins containing N6-alkyladenosines and 2-methylthio-N6-alkyladenosines. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 4472–4480 (2003).

Xie, Y. et al. 6-iodopurine as a versatile building block for RNA purine architecture modifications. Bioconjug. Chem. 33, 353–362 (2022).

Guralamatta Siddappa, R. K., Pandith, A. & Seo, Y. J. Direct and selective metal-free N6-arylation of adenosine residues for simple fluorescence labeling of DNA and RNA. Chem. Commun. 57, 5450–5453 (2021).

Guralamatta Siddappa, R. K. & Seo, Y. J. Directly arylated oligonucleotides as fluorescent molecular rotors for probing DNA single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 56, 116617–116621 (2022).

Tishinov, K., Schmidt, K., Häussinger, D. & Gillingham, D. G. Structure-selective catalytic alkylation of DNA and RNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 12000–12004 (2012).

Mao, R., Frey, A., Balon, J. & Hu, X. Decarboxylative C(sp3)–N cross-coupling via synergetic photoredox and copper catalysis. Nat. Catal. 1, 120–126 (2018).

Liang, Y., Zhang, X. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Decarboxylative sp3 C–N coupling via dual copper and photoredox catalysis. Nature 559, 83–88 (2018).

Nguyen, V. T. et al. Visible-light-enabled direct decarboxylative N-alkylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 7921–7927 (2020).

Li, Q. Y. et al. Decarboxylative cross-nucleophile coupling via ligand-to-metal charge transfer photoexcitation of Cu(ii) carboxylates. Nat. Chem. 14, 94–99 (2022).

Liu, Y., Yang, Y., Zhu, R. & Zhang, D. Computational clarification of synergetic RuII/CuI-metallaphotoredox catalysis in C(sp3)–N cross-coupling reactions of alkyl redox-active esters with anilines. ACS Catal. 10, 5030–5041 (2020).

Wang, H., Bag, R., Karuppu, S., Chen, G. & Xiao, G. Handbook of CH-Functionalization. In C–H Functionalization-Based Strategy in the Synthesis and Late-Stage Modification of Drug and Bioactive Molecules (ed. Maiti, D.) 1–65 (WILEY-VCH, 2022).

Xie, R. et al. Late-stage guanine C8–H alkylation of nucleosides, nucleotides, and oligonucleotides via photo-mediated Minisci reaction. Nat. Commun. 15, 2549 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Regioselective homolytic C2–H borylation of unprotected adenosine and adenine derivatives via minisci reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 21428–21441 (2024).

Ge, Y. et al. Visible light-mediated late-stage thioetherification of mercaptopurine derivatives. Chem. Eur. J. 30, e202401774 (2024).

Ge, Y. et al. Ligand-enabled copper-catalyzed N6-arylation of 2′-deoxyadenosine and its analogues. Tetrahedron Lett. 138, 154983 (2024).

Zhao, Q. et al. Palladium-catalyzed C–H olefination of uridine, deoxyuridine, uridine monophosphate and uridine analogues. RSC Adv. 12, 24930–24934 (2022).

N-6-Methyl-2-deoxyadenosine-d3 CAS No.1354782-02-7 - Ruixibiotech. Ruixibiotech.com https://www.ruixibiotech.com/pts/n-6-methyl-2-deoxyadenosine-d3 (2025).

Genossar, N. et al. Ring-opening dynamics of the cyclopropyl radical and cation: the transition state nature of the cyclopropyl cation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 18518–18525 (2022).

Crooke, S. T., Baker, B. F., Crooke, R. M. & Liang, X. Antisense technology: an overview and prospectus. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 427–453 (2021).

Setten, R. L., Rossi, J. J. & Han, S. The current state and future directions of RNAi-based therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 421–446 (2019).

Wan, W. B. & Seth, P. P. The medicinal chemistry of therapeutic oligonucleotides. J. Med. Chem. 59, 9645–9667 (2016).

Egli, M. & Manoharan, M. Chemistry, structure and function of approved oligonucleotide therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 2529–2573 (2023).

Dhara, D., Mulard, L. A. & Hollenstein, M. Natural, modified and conjugated carbohydrates in nucleic acids. Chem. Soc. Rev. 54, 2948–2983 (2025).

Tan, L. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of cordycepin: a review. Phytother. Res. 35, 1284–1297 (2020).

el Kouni, M. H. Trends in the design of nucleoside analogues as anti-hiv drugs. Curr. Pharm. Des. 8, 581–593 (2002).

Suzuki, M., Okuda, T. & Shiraki, K. Synergistic antiviral activity of acyclovir and vidarabine against herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and varicella-zoster virus. Antiviral Res. 72, 157–161 (2006).

Tavares, L. P. et al. Blame the signaling: role of cAMP for the resolution of inflammation. Pharmacol. Res. 159, 105030–105041 (2020).

Dando, T. M. & Plosker, G. L. Adefovir dipivoxil: a review of its use in chronic hepatitis B. Drugs 63, 2215–2234 (2003).

Lamb, Y. N. Remdesivir: first approval. Drugs 80, 1355–1363 (2020).

Covarrubias, A. J., Perrone, R., Grozio, A. & Verdin, E. NAD+ metabolism and its roles in cellular processes during ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 119–141 (2021).

Omumi, A., Beach, D. G., Baker, M., Gabryelski, W. & Manderville, R. A. Postsynthetic guanine arylation of DNA by suzuki−miyaura cross-coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 42–50 (2010).

Mourani, R. & Damha, M. J. Synthesis, characterization, and biological properties of small branched RNA fragments containing chiral (Rp and Sp) 2′,5′-phosphorothioate linkages. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 25, 203–229 (2006).

Jayalath, P., Pokharel, S., Véliz, E. & Beal, P. A. Synthesis and evaluation of an RNA editing substrate bearing 2′-deoxy-2′-mercaptoadenosine. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 28, 78–88 (2009).

Grimm, W. A. H. & Leonard, N. J. Synthesis of the ‘Minor Nucleotide’ N6-(γ,γ-Dimethylallyl) adenosine 5’-phosphate and relative rates of rearrangement of 1- to N6-dimethylallyl compounds for base, nucleoside, and nucleotide. Biochemistry 6, 3625–3631 (1967).

Čerňa, I., Pohl, R. & Hocek, M. The first direct C–H arylation of purine nucleosides. ChemComm 45, 4729–4730 (2007).

Storr, T. E. et al. Pd(0)/Cu(I)-mediated direct arylation of 2′-deoxyadenosines: mechanistic role of Cu(I) and reactivity comparisons with related purine nucleosides. J. Org. Chem. 74, 5810–5821 (2009).

Fantoni, N. Z., El-Sagheer, A. H. & Brown, T. Hitchhiker’s guide to click-chemistry with nucleic acids. Chem. Rev. 121, 7122–7154 (2021).

Van Poecke, S. et al. 3′-[4-Aryl-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)]-3′-deoxythymidine analogues as potent and selective inhibitors of human mitochondrial thymidine kinase. J. Med. Chem. 53, 2902–2912 (2010).

Rajendran, A., Endo, M., Katsuda, Y., Hidaka, K. & Sugiyama, H. Photo-cross-linking-assisted thermal stability of DNA origami structures and its application for higher-temperature self-assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 14488–14491 (2011).

Kashida, H., Doi, T., Sakakibara, T., Hayashi, T. & Asanuma, H. p-Stilbazole moieties as artificial base pairs for photo-cross-linking of DNA duplex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 7960–7966 (2013).

Tomás-Gamasa, M., Serdjukow, S., Su, M., Müller, M. & Carell, T. “Post-It” type connected DNA created with a reversible covalent cross-link. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 796–800 (2014).

Wang, J. et al. Kinetically guided radical-based synthesis of C(sp3)−C(sp3) linkages on DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, E6404–E6410 (2018).

Robson, F. et al. Coronavirus RNA proofreading: molecular basis and therapeutic targeting. Mol. Cell 80, 1136–1138 (2020).

Lyles, D. S. & Rupprecht, C. E. Rhabdoviridae. In Fields Virology 5th edn (eds Knipe, D. M. & Howley, P. M.) 1363–1408 (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007).

Jordheim, L. P., Durantel, D., Zoulim, F. & Dumontet, C. Advances in the development of nucleoside and nucleotide analogues for cancer and viral diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 447–464 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant 22271186 and 22001165, G.C.), the Natural Science Foundation of Qinghai Province (2023-ZJ-917M, G.C.) and Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTU). We thank Prof. Ruowen Wang (SJTU) for editorial advice on the manuscript preparation, and Ms. Heyu Zhang (SJTU) for the preparation of intermediates. We also thank Prof. Wanbin Zhang’s lab (SJTU) for the kind gift of Remdesivir and GS-441524.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.C. conceived and directed the project. R.X., G.X., Wanlu, L., Wenhao, L., M.B., Y.Q., X.L., Y.L., and L.S. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. G.C. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A patent application by G.C., G.X., W.L. and Y.L. detailing part of this research was filed through the Patent Office of the People’s Republic of China (March 2023). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Marcel Hollenstein and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, R., Xiao, G., Li, W. et al. Late-stage adenine N6-alkylation of nucleos(t)ides and oligonucleotides via photoredox and copper co-catalytic decarboxylative C(sp3)–N coupling. Nat Commun 17, 1090 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67851-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67851-w