Abstract

Proton conduction pathways and mechanisms in covalent organic frameworks (COFs) have long been obscured by polycrystalline disorder. Here we report a solvent-free melt-phase post-synthetic modification (PSM) strategy that enables precise functionalization of three-dimensional single-crystalline COFs while preserving crystallinity. This methodology overcomes the limitations of solvent-mediated PSM by operating above the melting point of azole reagents, ensuring homogeneous pore accessibility without solvent occlusion. Applied to archetypal imine-linked COF-300, the method achieves crystallographically resolved conversion of fragile imine bonds (C = N, 1.245 Å) into robust amine linkages (C–N, 1.415 Å), concurrently covalently anchoring of proton-conductive azoles (C–N, 1.487 Å) on the COFs skeleton. The resulting azole-functionalized COFs (COF-300-1,2,3-triazole, COF-300-1,2,4-triazole, COF-300-pyrazole) exhibit intrinsic anhydrous superprotonic conductivity reaching 4.35 × 10−3 S cm−1 at 170 °C, with low activation energies (0.153–0.186 eV). Atomic-resolution crystallography and DFT calculations reveal that rigid hydrogen-bond networks eliminate thermal barriers for proton hopping, establishing a definitive structure-property correlation for proton transport in single-crystal COFs. This work pioneers a versatile platform for functionalizing 3D crystalline porous materials under solvent-free conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) are emerging crystalline porous polymers with two- or three-dimensional structures assembled from pre-designed geometrical organic building blocks, which have potential applications in adsorption and separation, sensing, and catalysis1,2,3,4. The inherent structural designability and porosity of COFs render them an exceptional synthetic platform for the precise installation and transformation of functional groups, enabling the attainment of targeted functional properties through both pre-synthetic and post-synthetic modification (PSM) strategies5,6,7,8. Notably, the PSM approach facilitates the covalent incorporation of diverse chemical functional groups into the skeleton of crystalline porous materials while preserving their original topological structure9,10,11,12. Despite the extensive research on PSM strategies in the field of MOFs13,14, the research on the PSM of COFs is still in its infancy, mainly focusing on two-dimensional COFs, and the functionalization of three-dimensional COFs is still largely unexplored15,16,17. More importantly, due to the scarcity of COFs single crystals, the characterization of PSM of COFs mainly relies on indirect characterization techniques, such as IR, NMR, and other spectroscopy, and the accurate structural information of the PSM of COFs at the atomic level is still a great challenge. To the best of our knowledge, there is only one reports that utilizes high-quality single-crystal X-ray crystallography to elucidate the structural information of PSMs of COFs at the atomic level, including reaction sites, spatial arrangements, and bond lengths16.

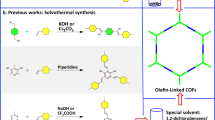

As the most extensively researched subclass of COFs, imine-linked COFs have garnered significant attention because of their high crystallinity, tunable pore architectures, broad synthetic conditions (including solvent and temperature variations), and facile structural building blocks18,19,20,21,22,23. Nevertheless, while the dynamic nature of imine-bond is crucial for crystallization, the intrinsic reversibility of imine bond results in limited stability of imine-linked COFs, particularly under hydrolytic and acidic conditions10,24,25. The PSM approach for imine-linked COFs not only stabilizes imine bonds, thereby enhancing the hydrolytic stability of COFs, but also facilitates the incorporation of functional molecules into the COFs skeleton10. Another advantage of PSM is the diffusion of active chemicals within the pores of COFs, which extends solution-phase organic chemistry into the solid state while preserving structural integrity and crystallinity, thereby enabling precise control over the localization of chemical functional groups within the COFs skeloton7,8. Currently, there are two main strategies for PSM of imine bonds, one is to convert imine bonds into ring structures, such as thiazole ring11 or a pyridine ring12, while the other is to transformed imine bonds into amine bonds through addition reactions, simultaneously grafting functional groups onto the COF skeleton10,26. Employing electrophilic or nucleophilic reagents for addition reactions with imine bonds can anchor richer functional groups to the pore-wall of COFs, thereby fine-tuning the properties of COFs at the molecular level, surpassing the constraints of conventional synthetic methodologies9.

Despite these advancements, current PSM methodologies for COFs predominantly depend on solvent-mediated processes, which impose significant constraints on the functionalization of three-dimensional single-crystalline COFs5,6,7,8,9. Residual solvents inherently occupy pores or channels, hindering guest molecule diffusion and concealing active functional sites for applications requiring accessible active centers (e.g., proton conduction). Moreover, no methodology currently enables solvent-free PSM of 3D single crystals COF while preserving crystallinity for atomic-level structural validation. To address these challenges, we propose a solvent-free melt-phase PSM strategy that operates above the melting point of functional reagents, thereby eliminating solvent inclusion and ensuring homogeneous pore accessibility. This strategy uniquely combines three advantages: (i) elimination of solvent contamination, maximizing free volume for guest diffusion; (ii) enhanced diffusion kinetics of molten modifiers, facilitating deep pore penetration; and (iii) preservation of crystallinity, enabling atomic-resolution structural characterization of the functionalized frameworks. Herein, we demonstrate the application of this methodology to achieve crystallographically precise conversion of fragile imine-linked 3D COFs into robust amine-linked frameworks while installing proton-conductive azole motifs on the skeleton.

Three azole-functionalized amine-linked 3D single-crystal COFs, namely COF-300-1,2,3-triazole, COF-300-1,2,4-triazole, and COF-300-pyrazole, were synthesized and characterized via high-resolution single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD). Direct evidence for the conversion of imine bonds (C = N, 1.245 (7) Å) to amine bonds (C–N, 1.415 (5) Å) and the subsequent ligation of azoles to COF skeleton (C–N, 1.487 (5)) was provided by single-crystal crystallography, combining with Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and solid-state 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (ssNMR) spectroscopy. Furthermore, the azole-functionalized COFs exhibit intrinsic single-crystal superprotonic conductivites27 under anhydrous conditions reaching up to 170 °C (4.14 ~ 4.35 × 10−3 S cm−1) with low activation energies ranging from 0.153 to 0.186 eV28. Atomic-resolution crystallography and theoretical calculations reveal that the rigidity of hydrogen bonds enhances proton transport capabilities, and static hydrogen-bond networks eliminate thermal barriers. By correlating well-defined hydrogen-bond geometries with macroscopic proton dynamics, a single-crystal COF model is established to unambiguously map proton transport pathways.

Results

PSM of imine-linked COF with azoles

Although conventional reduction strategies (e.g., NaBH424 or formic acid25) can convert imine-linked COFs into stable amine-linked frameworks, they fail to confer additional functionality. To address this limitation, we explore azole-mediated PSM of imine bonds, which concurrently enhances framework stability and proton conductivity. Azoles engage in nucleophilic addition with imine bonds, transforming C = N linkages into robust C–N bonds while covalently grafting proton-conductive functional groups to the COF skeleton (Fig. 1a, b). Importantly, these anchored azoles facilitate the formation of extended hydrogen-bond networks, thereby promoting efficient proton transport. To systematically evaluate this approach, eight prevalent azoles were selected for PSM reactivity testing with single-crystalline 3D COF-300. Azoles featuring two adjacent N atoms (1H-1,2,3-triazole, 1H-1,2,4-triazole, pyrazole) effectively undergo nucleophilic addition reactions with imine bonds, converting imine bond into amine linkages with concurrent covalent anchoring to the skeleton (Supplementary Fig. 8). In contrast, imidazole derivatives (Imidazole, 2-Methylimidazole, 2-Ethylimidazole) were incorporated solely as guests, leaving imine bonds intact. Larger azoles (Benzimidazole, Benzotriazole) exhibited no PSM activity due to steric hindrance within the 1D channels (Supplementary Fig. 9). The proposed reaction mechanism, exemplified by 1H-1,2,3-triazole, involves nucleophilic attack by the 2-position nitrogen on the electron-deficient carbon of the imine, forming a zwitterionic intermediate I, followed by intramolecular hydrogen transfer to complete the transformation29. The inability of imidazole derivatives to undergo nucleophilic addition is attributed to the steric hindrance preventing intramolecular hydrogen transfer from the reaction intermediates II (Fig. 1c).

a,b Post-synthetic modification of COF-300 with azoles. c (Ⅰ) The reaction mechanism of the addition process involving 1H-1,2,3-triazole as a representative. (Ⅱ) The reaction mechanism of the addition process involving imidazole as a representative. d The crystal structures of COF-300 and COF-300-1,2,3-triazole.

Synthesis and structural characterization

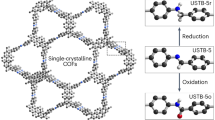

The azole-functionalized amine-linked 3D single-crystal COFs were synthesized via the solvent-free melt-phase PSM of COF-300 with azoles in their molten state (Fig. 1b). Our previous work has proved that COF-300 can retain its crystallinity and structural integrity at 280 °C30. This advanced synthetic methodology eliminates solvent diffusion into the COF pores during the PSM process, thereby preventing pore blockage by solvent molecules. For instance, COF-300-1,2,3-triazole was synthesized by reacting of single-crystal COF-300 with 1,2,3-triazole at 90 °C for 12 h (melting point of 1,2,3-triazole is 25 °C). The imine linkages within COF-300 undergo nucleophilic addition with 1,2,3-triazole, converting the imine-bonds into amine-bonds while covalently anchoring 1,2,3-triazole molecules to the amine groups (Fig. 2b). Additionally, COF-300-1,2,4-triazole and COF-300-pyrazole were synthesized at 125 °C (melting point of 1,2,4-triazole is 121 °C) and 90 °C (melting point of pyrazole is 70 °C), respectively.

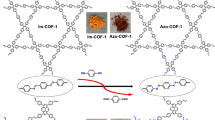

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis reveals that COF-300-1,2,3-triazole, COF-300-1,2,4-triazole, and COF-300-pyrazole are isostructures and cystallized in tetragonal system with I41/a space group. As a representative, the structure of COF-300-1,2,3-triazole was described in details. COF-300-1,2,3-triazole retains a structure similar to pristine COF-300, featuring a sevenfold-interpenetrated dia-c7 topology18,20,23 (Fig. 3a). A significant distinction between COF-300 and COF-300-1,2,3-triazole lies in the transformation of imine bonds (C = N, 1.245 (7) Å) in COF-300 to amine bonds (C–N, 1.415 (5) Å) in COF-300-1,2,3-triazole (Fig. 1d). The single-crystal data for three independent COF-300-1,2,3-triazole samples reveal the C–N bond lengths ranging from 1.415 to 1.424 Å, providing direct evidence for the conversion of imine bonds to amine bonds. Additionally, the amine bond demonstrates greater rotational flexibility compared to the imine bond; the angle between the C = N bond and benzene rings measures approximately 10.20° in COF-300, whereas this angle increases to 36.40° in COF-300-1,2,3-triazole, accompanied by an increase in the dihedral angle between adjacent benzene rings from 44.18° (COF-300) to 49.53° (COF-300-1,2,3-triazole). As the addition reaction proceeds, the triazole molecules are covalently coordinated to the C atoms of amine-bonds with the bond length of 1.487 (5) Å (Fig. 1d).

Moreover, the dimension of the diamondoid unit in COF-300-1,2,3-triazole is 26.01 × 26.01 × 54.30 Å3, which is thinner and longer compared to that of COF-300 (26.19 × 26.19 × 53.31 Å3, Fig. 2a, b). The angles between adjacent linkers of the tetratopic node in COF-300-triazole are measured at 87.54° and 121.43°, respectively, while the length of the diimine linkers connecting the tetrahedral nodes increases from 18.68 Å to 18.80 Å (Fig. 2a, b). Collectively, these factors contribute to distortions in the channels of COF-300 to better accommodate the triazole molecules, along with PSMs to the imine bond. It is worth noting that the anchoring of the triazole molecule to the COF-300 skeleton transforms the original one-dimensional square channel of COF-300 into a helical channel (Fig. 3d), with free triazole molecules being organized into the channel as to form extended proton-conducting networks. Crystallographic analysis reveals that free triazole molecules within the channels are stabilized by π–π stacking interactions (3.53 Å) with adjacent coordinated triazole groups (Fig. 3b). A static one-dimensional helical hydrogen-bond network is formed through robust intermolecular hydrogen-bond (N5–H5···N7: 2.50 (2) Å) between neighboring free triazole molecules (Fig. 3b, c). Platon calculation indicate that in the structure of COF-300-triazole, the anchored and organized triazole molecules completely occupy the channel, leaving no residual solvent-accessible voids for additional guest molecules.

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis reveals that all azole@COF-300 composites (namely Imidazole@COF-300, 2-Methylimidazole@COF-300, 2-Ethylimidazole@COF-300, Benzimidazole@COF-300 and Benzotriazole@COF-300) retain the sevenfold-interpenetrated dia-c7 topology of the parent COF-300. These composites predominantly crystallize in the tetragonal space group I4₁/a (Supplementary Table 21, 22, 24, 25), with the exception of 2-Ethylimidazole@COF-300, which adopts the I_4 space group (Supplementary Table 23). The unit cell parameters are similar to those of pristine COF-300. Within the one-dimensional channels, guest azole molecules are physically adsorbed via van der Waals interactions and assemble into one-dimensional columnar arrays. Their packing density is governed by molecular size: smaller imidazole molecules form four columns per channel, while the bulkier 2-Ethylimidazole accommodates only two columns. Importantly, no covalent bonding occurs between the guest molecules and the COF-300 skeleton, leaving the imine linkages (C = N, ~1.245 Å) fully intact.

The powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns indicate that COF-300-1,2,3-triazole maintains high crystallinity, and the characteristic peaks are consistent with the PXRD patterns simulated from single-crystal data (Fig. 2c). Infrared (IR) spectroscopy provided definitive evidence for the conversion of imine bonds to amine bonds after PSM. The IR spectrum of COF-300 displays a strong peak at 1614 cm−1, which corresponds to the stretching vibration of the imine bonds. In contrast, COF-300-1,2,3-triazole displays a peak at 1268 cm−1 attributed to N–H bending vibrations. The double peaks at 3000 cm−1 and 3130 cm−1 of N–H stretching vibrations are associated with the hydrogen bonds between free triazole molecules (Fig. 2c). Solid-state 13C NMR spectroscopy provided further direct evidence for the conversion of imine bonds to amine linkages and the covalent anchoring of 1,2,3-triazole (Supplementary Fig. 42). In the spectrum of pristine COF-300, the characteristic signal at approximately 155 ppm is assigned to the imine carbon (C = N)18. This signal completely disappeared after the solvent-free melt-phase PSM. Concurrently, a key new signal emerged at approximately 65 ppm in the spectrum of COF-300-1,2,3-triazole, which can be unambiguously assigned to the carbon atom in the newly formed amine bond (N–C). This carbon is directly linked to the triazole ring, serving as direct evidence for the covalent anchoring of the triazole molecules. The solid-state 13C NMR results corroborate the single-crystal X-ray diffraction and FT-IR spectroscopy data, collectively confirming the precise conversion of the imine bonds in COF-300 to amine bonds via the solvent-free melt-phase PSM strategy. The thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curves show that COF-300-1,2,3-triazole, COF-300-1,2,4-triazole, and COF-300-pyrazole all exhibit excellent thermal stability comparable to that of the pristine COF-300 (Supplementary Fig. 30–36). This indicates that the solvent-free melt-phase PSM strategy do not significantly compromise the framework’s thermal robustness. Under ambient air conditions, all three materials demonstrate similar decomposition behaviors (Supplementary Fig. 32, 34, 36). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra confirmed the elemental composition of COF-300-1,2,3-triazole (Supplementary Fig. 43–45).

Single-crystal proton conductivities under anhydrous conditions

To elucidate the intrinsic proton conduction mechanisms and intra-lattice proton transport pathways within COFs, we performed single-crystal impedance spectroscopy measurements on COF-300-1,2,3-triazole, COF-300-1,2,4-triazole, and COF-300-pyrazole using interdigital electrodes. This approach eliminates interfacial resistance artifacts typically associated with conventional conductive adhesives. The single-crystal exhibits a flattened pyramidal morphology with well-defined (011) basal plane, and the channels along the crystallographic c-axis parallel to the diagonal of the base (Supplementary Fig. 49). To optimize the electrode-crystal interface, the crystal’s basal edge was precisely aligned parallel to the electrode array direction, establishing a geometric configuration where the 1D channels intersect the measurement axis at 45° (Supplementary Fig. 50). A crystal of dimensions 140 × 140 × 90 μm3 was selected to bridge three adjacent electrodes (20 μm width/spacing), ensuring reliable electrical contact. However, this orientation geometry precludes direct measurement of anisotropic proton conductivity along different crystallographic axes.

Anhydrous alternating current (AC) impedance spectroscopy was conducted on COF-300-1,2,3-triazole, COF-300-1,2,4-triazole, and COF-300-pyrazole at intermediate temperatures ranging from 100 to 170 °C. To ensure the circuit is continuity, 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide ([BMIM][TFSI]), a non-protonic ionic liquid, is employed to enhance the interfacial contact between the electrodes and the single crystals. Its ionic conductivity (170 °C, ~2.66 × 10−2 S cm−1, Supplementary Table 15) is significantly higher than that of the measured COFs, effectively eliminating interference from contact impedance. As [BMIM][TFSI] provides no exchangeable protons, the measured conductivity can be unambiguously attributed to the intrinsic proton transport within the COFs. Under anhydrous conditions, COF-300-1,2,3-triazole exhibited superprotonic conductivity, reaching a maximum conductivity of 4.23 × 10−3 S cm−1 at 170 °C (Fig. 4a)31,32,33,34,35,36. Along with decreasing the temperature to 150, 130 and 110 °C, the proton conductivities gradually declined to 3.61 × 10−3 S cm−1, 3.23 × 10−3 S cm−1, and 2.73 × 10−3 S cm−1, respectively (Supplementary Table 3). The observed activation energy of 0.153 eV for COF-300-1,2,3-triazole under anhydrous conditions (Fig. 4d) suggests a low-energy Grotthuss-type hopping mechanism37,38. This efficient proton transport is facilitated by a stable and robust hydrogen-bond network within the preorganized transport pathways. Considering the boiling point of 1, 2, 3-triazole ( ~ 203 °C) and the TG analysis of COF-300-1,2,3-triazole, the incorporated 1, 2, 3-triazole molecules within the channels remain stable up to 170 °C. This thermal stability surpasses that of H3PO4 (boiling temperature ~158 °C) doped COFs, which are commonly employed as anhydrous proton-conducting materials16,39,40. Notably, under identical conditions (170 °C, anhydrous), COF-300-1,2,4-triazole and COF-300-pyrazole exhibited proton conductivities of 4.1 5× 10−3 S cm−1 and 4.35 × 10−3 S cm−1, respectively (Supplementary Table 4, 5), with corresponding activation energies of 0.186 eV and 0.155 eV (Fig. 4d). The primary reason for these comparable proton conductivity behaviors lies in the similar crystal structures and proton transport pathways shared by COF-300-1,2,3-triazole, COF-300-1,2,4-triazole, and COF-300-pyrazole.

a Impedance spectroscopy of COF-300-1,2,3-triazole under anhydrous conditions. b Impedance spectroscopy of COF-300-1,2,4-triazole under anhydrous conditions. c Impedance spectroscopy of COF-300-pyrazole under anhydrous conditions. d Activation energy (Ea) of COF-300-1,2,3-triazole、COF-300-1,2,4-triazole and COF-300-pyrazole. e Proton conductivities of COF-300-azole in comparison to other single-crystal proton-conducting materials reported. f Kinetic energy barriers for proton conduction in COF-300-triazole. The initial state and final state are inserted.

Compared with the benchmark single-crystal proton-conducting materials under anhydrous conditions, COF-300-1,2,3-triazole, COF-300-1,2,4-triazole, and COF-300-pyrazole demonstrate superprotonic conductivity and low activation energy across wide temperature ranges (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table 16). Furthermore, we investigated the proton transfer isotope effect in COF-300-1,2,3-triazole by assessing the anhydrous proton conductivity of COF-300-1,2,3-deuterated triazole within the 100 °C–160 °C (Supplementary Fig. 61). The proton conductivity of COF-300-1,2,3-deuterated triazole reached the maximum value of 2.37 × 10−3 S cm−1 at 160 °C, which is about 1.6 times lower than that of COF-300-1,2,3-triazole, with an activation energy of 0.225 eV, thereby confirming that proton is the charge carrier in the observed conduction process (Supplementary Table 11 and Supplementary Fig. 62).

The anhydrous single-crystal proton conductivity of azole@COF-300 composites was measured by alternating current (AC) impedance spectroscopy using interdigitated electrodes and [BMIM][TFSI] as an interfacial mediator at 100 °C–140 °C (Supplementary Fig. 51, 53, 55, 57, 59). The proton conductivity ranged from 3.2 × 10−4 to 1.5 × 10−3 S cm−1 (Supplementary Table 6–10), which is notably lower than that of COF-300-azole ( > 4 × 10−3 S cm−1 at 170 °C). The corresponding activation energy was 0.228–0.385 eV (Supplementary Fig. 52, 54, 56, 58, 60). This relatively moderate conduction performance originates from the absence of a rigid, static hydrogen-bonding network. Proton transport relies on weak intermolecular hydrogen bonds between physically adsorbed azole guests, which are susceptible to thermal disruption. In contrast, covalently anchored azoles in functionalized COFs form continuous pathways for proton hopping.

To complement our experimental observations, we performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations to elucidate the atomic-scale proton conduction mechanisms within COF-300-1,2,3-triazole. The optimized lattice constant for COF-300-1,2,3-triazole exhibited congruence with experimental data (Supplementary Fig. 67). Investigation into the proton transport pathway and the associated kinetic barrier in COF-300-1,2,3-triazole revealed a well-defined proton migration pathway along the rigid hydrogen-bond network of 1,2,3-triazole molecules, characterized by an optimized N–H···N hydrogen-bond length of 2.726 Å and the calculated activation energy of 0.074 eV (Fig. 4f), which is in close agreement with experimental findings. These theoretical insights provide a comprehensive understanding of the proton conduction mechanisms in single-crystal COFs, bridging the gap between atomic-scale structure and macroscopic transport properties.

Discussion

This work develops a solvent-free melt-phase PSM strategy as an innovative platform for functionalizing 3D single-crystalline COFs. By operating above the melting point of azole reagents, we overcome the critical limitations associated with solvent-mediated PSM, facilitating uniform functionalization without pore occlusion and maintaining crystallinity for atomic-resolution characterization. High-resolution single-crystal X-ray diffraction enables direct visualization of covalent bond transformations (imine C = N to amine C–N, 1.245 Å to 1.415 Å) and the covalent anchoring of proton-conductive azoles (C–N, 1.487 Å), providing a detailed atomic-level structural blueprint for COF PSM. The azole-functionalized COFs demonstrate exceptional intrinsic anhydrous proton conductivity ( > 4 × 10−3 S cm−1 up to 170 °C) with low activation energies (0.153–0.186 eV). Integrating crystallographic and computational analyses reveals that rigid hydrogen-bond networks facilitate low-energy Grotthuss proton hopping, establishing a definitive structure-property relationship. This methodology pioneers a general avenue for solvent-free functionalization strategies applicable to crystalline porous materials beyond proton conduction.

Methods

Materials and instruments

Tetrakis(4-aminophenyl)methane (TAM, purity ≥ 98%), Benzene-1,4-dicarboxaldehyde (BDA, purity ≥ 99%) were purchased from Jilin Chinese Academy of Sciences-Yanshen Technology Co., Ltd. 1H-1, 2, 3-triazole was purchased from Aladdin Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd., China.

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SXRD) data of COF-300, azole@COF-300, and COF-300-azole were collected on a Bruker D8 VENTURE CMOS PHOTON 100 diffractometer with helios mx multilayer monochromator Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) at 173 K and 293 K. Crystal data and details of the structure refinement are given in Supplementary Tables 17–25. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) data were collected on a Rigaku-DMAX 2500 diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) at a scanning rate of 2°/min for 2θ ranging from 5° to 30°. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet Is50 micro FTIR spectrometer. The TGA from 30 °C–800 °C was carried out on a DTG-60H in nitrogen atmosphere using a 20 °C/min ramp without equilibration delay and in air atmosphere using a 20 °C/min ramp without equilibration delay. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) were conducted using a SHIMADZU AXIS SUPRA+ photoelectron spectrometer. Solid-State 13C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) was performed on a Bruker Avance NEO 400 spectrometer at a 10 MHz 13C resonance frequency, using a Bruker double-resonance magic-angle spinning probehead for 4-mm rotors. 1H NMR spectra were recorded at 25 °C on a Varian 500 MHz spectrometer and TMS as internal standard. The chemical shifts (δ) are given in parts per million relatives to internal standard TMS (0 ppm for 1H). NMR signal assignments were supported by a combination of literature comparisons for known analogous compounds and computational prediction performed with ChemDraw. High-resolution mass spectrometry data were acquired using the Shimadzu LCMS-9030 quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) high-resolution mass spectrometer coupled with liquid chromatography. Electrospray ionization (ESI) served as the ion source, with mass analysis conducted in positive ion mode. All data were collected and processed using LabSolutions software.

Proton conductivity: The single crystal (140 × 140 × 90 μm3) was placed on a interdigital electrode (the electrode width and the inter-electrode distance are 20 μm). Adjust the position of the crystal under the microscope, ensuring that the base edge of the crystal spans across three electrodes to guarantee connectivity. The proton conductivity was measured using the alternating current (AC) impedance method of a Solartron SI 1260 Impedance/Gain Phase Analyzer, with a test frequency range of 1 Hz to 1 MHz and an applied voltage of 100 mV. For variable temperature and variable humidity electrochemical impedance (EIS) testing, the test is performed after equilibrating each test point for 30 minutes and 12 h, respectively. For anhydrous alternating current (AC) impedance test, non-protonic ionic liquid 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide ([BMIM][TFSI]) is used to increase the contact between the electrodes and the single crystal. Zview software was used to fit the impedance data. Extrapolation of the arc of the impedance spectrum to the X-axis gives resistance. The proton conductivity σ is calculated by taking into account the geometric properties of the electrode array by Eq. (1), where A is the contact area between the sample and the electrodes, n is the number of spacings between electrodes, D is the inter-electrode distance (20 μm), d is the electrode width (20 μm), and a is the width of the crystal:

The activation energy (Ea) was calculated from the linear Arrhenius curve, and the equation was as follows:

where σ0 is the pre-exponential factor, T is the absolute temperature and kB is the Boltzmann constant.

Synthesis of single-crystal COF-300

The COF-300 was synthesized according to the literature23. A sample vial (5.0 mL) was sequentially charged with BDA (12 mg, 0.089 mmol), 1,4-dioxane (0.50 mL) and CF3CH2NH2 (70 μL, 10 equiv.). Then, 0.10 mL of CF3COOH (6.0 M) was added. TAM (20 mg, 0.052 mmol) was dissolved in 1,4-dioxane (0.50 mL) and added to the solution. The mixture was filtered through a 0.20 μm Nylon-6 membrane filter, and the reaction was allowed to stand at temperature of 35 °C. Then, the yellow single crystals of COF-300 were fast crystallized and the crystal size reached ~150 μm in 10 days. The as-synthesized crystals were immersed in 1,4-dioxane for 1 day to exchange the guest molecules in the pores and were subjected to the SXRD measurements.

Synthesis of COF-300-azole

The single crystals of COF-300 (1 mg) and azole reagents (100 mg), including 1,2,3-triazole (melting point: 25 °C), 1,2,4-triazole (121 °C), pyrazole (70 °C), were combined in a 5.0 mL sample vial. The mixture was heated at 90 °C (1,2,3-triazole and pyrazole) and 125 °C (1,2,4-triazole) for 12 h. Subsequently, the mixture was washed with ethanol, and the resulting single crystals of COF-300-azole were isolated. The single crystal was sealed in a capillary tube to collect single-crystal X-ray crystallography.

Synthesis of azole@COF-300

The single crystals of COF-300 (1 mg) and azole reagents (100 mg), including imidazole (melting point: 91 °C), 2-methylimidazole (145 °C), 2-ethylimidazole (81 °C), benzimidazole (171 °C), and benzotriazole (99 °C), were combined in a 5.0 mL sample vial. The mixture was heated above the melting points of the respective azoles for 12 hours. Subsequently, the mixture was washed with ethanol, and the resulting single crystals of azole@COF-300 were isolated. These crystals were sealed within capillary tubes for single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis.

Synthesis of COF-300-1,2,3-deuterated triazole

The mixture of single crystals of COF-300 (1 mg) and 1D-1,2,3-triazole (100 mg) was put in a sample vial. The mixture was heated at 90 °C for 12 h. Then the mixture was washed with ethanol and COF-300-1,2,3-deuterated triazole was obtained.

Theory calculations

The structure optimizations was carried out using the density functional theory (DFT) in the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP, version 5.4.3). The general gradient approximation (GGA) with Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) function was adopted. The projector augmented-wave (PAW) pseudopotential was used to represent electron-ion interactions. The DFT-D3 correction was utilized to describe the van der Waals (vdW) interaction. The lane-wave cutoff energy of 500 eV was employed in all computations. The convergence threshold was set as 10−5 eV in energy and 0.05 eV Å−1 in force. The kinetic barriers for proton conduction were identified by the climbing-image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) methods.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 2418811 (COF-300-1,2,3-triazole), 2468192 (COF-300-1,2,4-triazole), 2468193 (COF-300-pyrazole), 2468194 (imidazole@COF-300), 2468195 (2-Methylimidazole@COF-300), 2468196 (2-Ethylimidazole@COF-300), 2468197 (benzimidazole@COF-300), 2468198 (benzotriazole@COF-300). These data can be obtained free of charge from the CCDC via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The data generated in this study are provided in Supplementary Information and Source Data file. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided in this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Huang, N., Wang, P. & Jiang, D. Covalent organic frameworks: a materials platform for structural and functional designs. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16068 (2016).

Diercks, C. S. & Yaghi, O. M. The atom, the molecule, and the covalent organic framework. Science 355, eaal1585 (2017).

Yin, Y. et al. Ultrahigh–surface area covalent organic frameworks for methane adsorption. Science 386, 693–696 (2024).

Guan, X., Chen, F., Fang, Q. & Qiu, S. Design and applications of three dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 1357–1384 (2020).

Khojastehnezhad, A., Samie, A., Bisio, A., El-Kaderi, H. M. & Siaj, M. Impact of postsynthetic modification on the covalent organic framework (COF) structures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 17, 11415–11442 (2025).

Volkov, A. et al. General strategy for incorporation of functional group handles into covalent organic frameworks via the UGI reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6230–6239 (2023).

Kim, J. H. et al. Post-synthetic modifications in porous organic polymers for biomedical and related applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 43–56 (2022).

Lu, Q. et al. Postsynthetic functionalization of three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks for selective extraction of lanthanide Ions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 6042–6048 (2018).

Nagai, A. et al. Pore surface engineering in covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 2, 536 (2011).

Lu, Z. et al. Asymmetric hydrophosphonylation of imines to construct highly stable covalent organic frameworks with efficient intrinsic proton conductivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 9624–9633 (2022).

Haase, F. et al. Topochemical conversion of an imine- into a thiazole-linked covalent organic framework enabling real structure analysis. Nat. Commun. 9, 2600 (2018).

Li, X. et al. Facile transformation of imine covalent organic frameworks into ultrastable crystalline porous aromatic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 9, 2998 (2018).

Cohen, S. M. Postsynthetic methods for the functionalization of metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 112, 970–1000 (2012).

Cohen, S. M. The postsynthetic renaissance in porous solids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 2855–2863 (2017).

Bunck, D. N. & Dichtel, W. R. Postsynthetic functionalization of 3D covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Commun. 49, 2457–2459 (2013).

Yu, B. et al. Linkage conversions in single-crystalline covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 16, 114–121 (2024).

Bunck, D. N. & Dichtel, W. R. Internal functionalization of three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 1885–1889 (2012).

Ma, T. et al. Single-crystal x-ray diffraction structures of covalent organic frameworks. Science 361, 48–52 (2018).

Kang, C. et al. Covalent organic framework atropisomers with multiple gas-triggered structural flexibilities. Nat. Mater. 22, 636–643 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Guest-dependent dynamics in a 3D covalent organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 3298–3303 (2019).

Zeng, T. et al. Atomic observation and structural evolution of covalent organic framework rotamers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2320237121 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. A crystalline three-dimensional covalent organic framework with flexible building blocks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 2123–2129 (2021).

Han, J. et al. Fast growth of single-crystal covalent organic frameworks for laboratory x-ray diffraction. Science 383, 1014–1019 (2024).

Liu, H., Chu, J., Yin, Z., Cai, X., Zhuang, L. & Deng, H. Covalent organic frameworks linked by amine bonding for concerted electrochemical reduction of CO2. Chem 4, 1696–1709 (2018).

Grunenberg, L. et al. Amine-linked covalent organic frameworks as a platform for postsynthetic structure interconversion and pore-wall modification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 3430–3438 (2021).

Feng, J. et al. Fused-Ring-Linked Covalent Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 6594–6603 (2022).

Otake, K. -i. et al. Confined water-mediated high proton conduction in hydrophobic channel of a synthetic nanotube. Nat. Commun. 11, 843 (2020).

Chen, J. et al. Highly efficient proton conduction in the metal–organic framework material MFM-300(Cr)·SO4(H3O)2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 11969–11974 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. NHC-catalyzed transformation reactions of imines: electrophilic versus nucleophilic attack. J. Org. Chem. 87, 7989–7994 (2022).

Yao, A. et al. Guest-induced structural transformation of single-crystal 3D covalent organic framework at room and high temperatures. Nat. Commun. 16, 1385 (2025).

Joseph, V. & Nagai, A. Recent advancements of covalent organic frameworks (COFs) as proton conductors under anhydrous conditions for fuel cell applications. RSC Adv. 13, 30401–30419 (2023).

Sahoo, R., Mondal, S., Pal, S. C., Mukherjee, D. & Das, M. C. Covalent-organic frameworks (COFs) as proton conductors. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2102300 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. Emerging covalent organic frameworks for efficient proton conductors. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 62, 16545–16568 (2023).

Zhu, L., Zhu, H., Wang, L., Lei, J. & Liu, J. Efficient proton conduction in porous and crystalline covalent-organic frameworks (COFs). J. Energy Chem. 82, 198–218 (2023).

Mukherjee, D., Saha, A., Moni, S., Volkmer, D. & Das, M. C. Anhydrous solid-state proton conduction in crystalline MOFs, COFs, HOFs, and POMs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 5515–5553 (2025).

Xu, H., Tao, S. & Jiang, D. Proton conduction in crystalline and porous covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Mater. 15, 722–726 (2016).

Agmon, N. The Grotthuss mechanism. Chem. Phys. Lett. 244, 456–462 (1995).

Kreuer, K.-D., Paddison, S. J., Spohr, E. & Schuster, M. Transport in proton conductors for fuel-cell applications: simulations, elementary reactions, and phenomenology. Chem. Rev. 104, 4637–4678 (2004).

Chandra, S. et al. Phosphoric acid loaded azo (−N═N−) based covalent organic framework for proton conduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 6570–6573 (2014).

Luan, T.-X. et al. “All in One” strategy for achieving superprotonic conductivity by incorporating strong acids into a robust imidazole-linked covalent organic framework. Nano Lett. 24, 5075–5084 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 22371032).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W. and C.S. conceived the idea. A.Y. conducted the synthesis and crystal growth of COF-300 and postsynthetic modifications. J.L. conducted the addition reaction mechanism. C.Z., and H.X. conducted the theoretical calculation. K.S. and C.Q. carried out the crystallographic studies. A. Y. and H. Z. and conducted the impedance spectroscopy measurements. X.W., Z.S., and D.J. interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, A., Zhu, C., Liu, J. et al. Enhanced proton conductivity in azole-functionalized three-dimensional crystalline covalent organic frameworks. Nat Commun 17, 1115 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67873-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67873-4