Abstract

The development of a safe and affordable redox flow battery technology is important for storing intermittent renewable energy. Here, we design a stable aqueous organic iron-cerium redox flow battery based on the inexpensive metal iron and the abundant rare earth metal cerium, enabled by the universal complexing agent diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid. Molecular dynamics simulations are employed to screen for carboxyl-containing ligands with different electron donating capacities, revealing that diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid is an effective candidate to chelate iron and cerium in the negolyte and posolyte, respectively, as verified by experimental characterization. The complexing agent enhances the redox characteristics of iron and cerium and reduces osmotic water migration between the negative and positive chambers by allowing the same ligand in both electrolytes. Our iron-cerium redox flow battery achieves an energy efficiency of 87.7% at 40 mA cm−2 and 80.6% at 100 mA cm−2, while retaining 95.3% of its initial capacity and maintaining around 86.3% energy efficiency after 500 cycles under neutral environments (100% of state-of-charge). The capacity is still preserved after 1779 cycles even when cycled at high-rates (80 mA·cm−2, 70% of state-of-charge).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

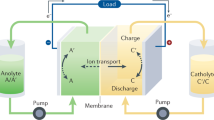

The intermittency of renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind, poses significant challenges to their integration into power grids1,2,3,4. The development of large-scale energy storage systems that are safe, affordable, and efficient will play an essential part in resolving this intermittency problem5,6,7. Among the various technologies available, redox flow batteries (RFBs) stand out due to their inherent safety, economic viability, and the ability to independently scale power and energy capacity8,9,10. Currently, the vanadium redox flow battery (VRFB) is the most mature technology pathway. However, it has not been able to fulfill the accelerating demand for long-term energy storage due to the scarcity of vanadium ore, for which it also competes with the steel industry11,12,13,14. Other reported RFB chemistries include iron-chromium, zinc-bromine, zinc-iron, and aqueous organic systems. However, each of these is constrained by intrinsic limitations such as chromium deactivation, bromine’s strong corrosiveness, zinc dendrite penetration of membranes, and the high sensitivity of organic active materials to air, respectively15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Due to the limitations imposed by their self-discharge, RFBs are typically employed for short-term energy balancing, reducing peak demand and filling low-demand periods on the grid. Now, with the increasingly large-scale integration of renewable energy into the grid, frequency modulation demands will rise, highlighting the need for new RFB technologies that address both peak regulation and frequency modulation23,24.

Iron has been utilized in RFB technology since the 1980s, attracting attention as a resource-rich and low-cost active material25. More recently, researchers have altered the solvation structure of iron by coordinating with organic ligands to construct alkaline iron-based RFBs. Such an RFB, composed of triethanolamine (TEA) and ferrocyanide, was found to achieve a voltage of 1.3 V26. Subsequently, a 3-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]−2-hydroxypropanesulfonic acid (DIPSO) ligand that was altered by sulfonating TEA achieved even greater Fe solubility27,28. In 2024, Li’s group successfully built an iron-based flow battery in a neutral environment by using a nitrilotri-(methylphosphonic acid) (NTMPA) ligand29. A serious issue that arises with this approach is that small organic ligands such as TEA can easily traverse the ion exchange membrane between the negative and positive chambers, causing side interactions with the active substances in the other chamber, along with the formation of hydroxide precipitate, shortening the lifespan of the RFB and jeopardizing the overall safety of the battery system30. Increasing the ligand’s steric hindrance effectively mitigates this shuttle problem31, but complete prevention of shuttling is impossible when electrolyte compositions differ between the negative and positive chambers over extended periods. Therefore, employing a universal complexing agent that functions effectively in both the posolyte and the negolyte presents a compelling strategy for homogenizing the two chambers. Nevertheless, this necessitates that the two active substances that constitute an RFB have a significant potential difference. Cerium has inherent benefits as the most abundant rare earth element and an eco-friendly material, with a standard redox potential as high as 1.65 V versus (vs.) SHE, and it can combine with other redox compounds that have low potential to build a high voltage RFB32,33. In typical cerium-based flow batteries, the posolyte is often a cerous mesylate system, but its sluggish kinetics result in a low current density for the battery34,35. Furthermore, the strongly acidic environment causes low coulombic efficiency (CE), accelerated battery deterioration, and harmful hydrogen evolution side reactions. To enhance its performance and create a stable flow battery, cerium’s solvation structure in water can be altered by introducing suitable electron-donating ligands to chelate with cerium.

We have developed an aqueous organic redox flow battery which incorporates iron and cerium as its active ingredients, and uses 5-carboxyl-containing diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) as a universal complexing agent ligand. After identifying the optimal ligand candidate through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the coordination chemistry was manipulated to alter the redox characteristics and electrochemical stability of iron and cerium. This design allows a theoretical cell voltage of 0.92 V, with solubilities reaching 0.858 M and 0.927 M in the neutral flow battery system for iron and cerium, respectively. We used this universal complexing agent in both the negolyte and posolyte, eliminating the impact of ligand transmembrane transport and minimizing water migration caused by the variations in osmotic pressure and viscosity between the negolyte and posolyte. The Fe-Ce DTPA RFB consistently maintains a CE close to 100%, with an energy efficiency (EE) that reached up to 86.3%, and a discharge capacity after cycling of 95.3% of the original capacity (100% state of charge, SOC). Our universal complexing agent RFB demonstrates excellent performance in 500-cycle testing in a neutral environment. Even at a high cycling rate of 80 mA cm−2 (70% SOC), long-term cycling stability and capacity were maintained without attenuation for 1779 cycles. Our universal complexing agent strategy, unified across the negolyte and posolyte, offers an important approach for the advancement of RFBs.

Results

Theoretical calculation and structural characterization

In aqueous solution, metal ions form a stable coordination structure by interactions between the oxygen atom’s lone pair electrons in its 2p orbital and the metal atom’s empty orbital. The carboxylic acid group (−COOH) is a common oxygen-containing electron donor. Several common ligands have −COOH in varying amounts: iminodiacetic acid (IDA, two −COOH groups), nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA, three −COOH groups), ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA, four −COOH groups), 1,3-propylenediaminetertaacetic acid (PDTA, four −COOH groups), diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA, five −COOH groups), among others (Fig. 1a). The number and position of −COOH, as well as the length of the ligand backbone, influence the coordination structure by modulating the electron donation intensity and steric hindrance. These factors offer effective approaches for designing RFB electrolytes.

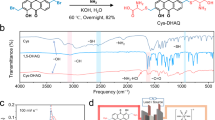

a Molecular formulas for IDA, NTA, EDTA, PDTA, and DTPA. b Radial distribution function and corresponding coordinated number of Fe-DTPA. c 3D snapshot and coordination structure of Fe-DTPA obtained from MD simulations. Ce-DTPA’s (d) radial distribution function and corresponding coordinated number and (e) 3D snapshot and coordination structure. The system anneals from 0 to 298 / 263 K in a time of 0.5 ns, and then runs another 1 ns to reach equilibrium. f Binding energies of Fe-based electrolytes (left) and Ce-based electrolytes (right). g Raman and (h) FTIR spectra of electrolytes. Calculated HOMO and LUMO energy levels of (i) Fe-based electrolytes and (j) Ce-based electrolytes. k Fourier-transformed EXAFS fitting curves of Fe-DTPA, FeCl3·6H2O, and Fe2O3. l The electrostatic potential maps of Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To identify appropriate electron donor ligands, MD simulations and density functional theory (DFT) calculations were employed to diagnose the evolution of Fe and Ce solvation structures at the atomic scale in the presence of carboxylic acid-containing ligands. The results of MD simulations, shown in Fig. 1b–e, Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, and Supplementary Data 1 reveal that the addition of ligands leads to coordination interactions between the O atom of ligands near the Fe or Ce ion in each electrolyte, reducing the coordination number (CN) of H2O. This suggests that the oxygen-containing ligands greatly reshape the Fe and Ce solvating structure. For example, the CN of Fe−H2O(O) in Fe-DTPA drops from 6 to 3.7, as illustrated in Fig. 1b, c, yet the CN of Fe−DTPA(O) rises to 0.46. Fe−DTPA(O) has a shorter radial distribution function (≈ 1.94 Å) than Fe−H2O(O) (≈ 2.11 Å), suggesting that Fe and DTPA(O) have a stronger binding strength than Fe−H2O(O). Similarly, the Ce coordination structure in Fig. 1d, e is Ce(H2O)4.55(DTPA)0.48, and the radial distribution functions of Ce−DTPA(O) and Ce−H2O(O) are slightly bigger than Fe-DTPA (2.16 Å and 2.32 Å, respectively), which is due to the increased radius of the Ce atom itself.

MD simulations of Fe and Ce coordinated with ligands IDA, NTA, EDTA, and PDTA are presented in Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, with Supplementary Table 1 summarizing the details. Although DTPA has a greater molecular size and steric hindrance than NTA, EDTA, and PDTA, which may make coordination with metal atoms more difficult, its five −COOH groups provide a stronger electron-donating capability. This means that Fe−DTPA(O) has a higher CN (0.46) than Fe−NTA(O) (0.45), Fe−PDTA(O) (0.41), and Fe−EDTA(O) (0.34). Similarly, the CN of Ce−DTPA(O) (0.48) is higher than that of Ce−NTA(O) (0.46), Ce−PDTA(O) (0.47), and Ce−EDTA(O) (0.43). Mean square displacement (MSD) plots of K+ ions and ligand molecular sizes are shown in Supplementary Figs. 3, 4. DFT calculation further supports these findings, showing that the binding energies of Fe-DTPA (−178 kcal mol−1) and Ce-DTPA (−1427 kcal mol−1) are lower than those of Fe or Ce with other ligands (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Data 1). Compared to ligands with fewer −COOH groups, that is IDA, NTA, EDTA, and PDTA, DTPA with its five −COOH groups has a higher binding capacity to Fe or Ce ions and generates more stable Fe−O or Ce−O interactions. Consequently, we deduce that DTPA ought to be a viable option for both the negolyte and posolyte of the flow battery.

Raman spectroscopy and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) characterizations were employed to experimentally verify the coordination structures in Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA electrolytes. The formation of the Ce−DTPA(O) bond was confirmed by the visible peak at 450 cm−1 in the Raman spectrum (Fig. 1g), which is absent in the reference spectrum for CeCl3. Similarly, the emergence of a new Fe-DTPA peak at 450 − 500 cm−1 confirms the formation of the Fe−DTPA(O) bond, and the disappearance of the Fe(H2O)6 peak (≈ 300 cm−1) in Fe-DTPA also confirms the change in solvation structure compared with a reference FeCl3 aqueous solution. Comparison with the Raman spectrum of free DTPA confirms that the new peaks observed in Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA arise from Fe–DTPA(O) and Ce–DTPA(O) bonds, rather than from the uncoordinated ligand. In the FTIR spectra, both Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA exhibit a new peak at ~ 935 cm−1, attributed to the stretching vibrations of the Ce−DTPA(O) and Fe−DTPA(O) bonds (Fig. 1h). The outcomes of the Raman and FTIR measurements match with the MD simulations. Synchrotron X-ray absorption spectroscopy measurements were performed to further clarify the local environment of the metal atoms. Fourier-transformed (FT) extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) fitting curves are presented in Fig. 1k. The prominent peak of Fe-DTPA, corresponding to the Fe−DTPA(O), has a lower radical distance than the Fe−H2O(O) peak of the FeCl3 reference. This result indicates that a strong electron-donating ability exists in the first solvation shell of the Fe ions in Fe-DTPA, compared to the Fe(H2O)6 solvation shell of the FeCl3 reference. The bond length and chemical environment of iron complexes can be obtained through least-squares EXAFS fitting, with detailed information displayed in Supplementary Table 2. The fitting reveals two Fe−O bond lengths of 1.98 Å and 2.17 Å in Fe-DTPA, which closely match the results calculated by MD (1.94 Å and 2.11 Å).

To assess each electrolyte’s facility for electron transfer, quantum chemical calculations were performed. A narrower band gap between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) indicates a stronger ability to transfer electrons, as it facilitates faster oxidation and reduction processes through stronger electronic coupling and lower activation barriers, respectively. Figure 1i, j, and Supplementary Data 1 show the frontier molecular orbital diagrams of the iron and cerium electrolytes, as well as their respective LUMO and HOMO energy levels. The calculated results show that the E value (the gap between the HOMO-LUMO) of Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA are 4.82 eV and 0.42 eV, respectively, which are the lowest values in their respective control groups, indicating their strong electron transfer properties.

Electrostatic potential (ESP) diagrams of Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA, shown in Fig. 1l and Supplementary Data 1, highlight five electron-rich regions in red, mainly concentrated in the oxygen atoms of the −COOH part. These regions are strong electron-donating sites for coordination with Fe or Ce. ESP comparisons with other ligand structures (Supplementary Fig. 5) show that the electron-donating capacity of ligands is mainly positively correlated with the number of −COOH, and DTPA, with its five −COOH groups having the strongest electron-donating capacity. Taken together, these results indicate that Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA formed by Fe, Ce, and DTPA are the most stable coordination structures.

Optical and physicochemical property investigation

The solubility of the electrolytes is a crucial factor for determining the energy density of the battery. To evaluate this, we investigated the maximum solubility of Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA. The ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) absorption spectra of Fe-DTPA at various concentrations (0.1 M to 0.8 M solution diluted 1000-fold) are shown in Fig. 2a, b. A calibration curve was established between absorbance and concentration, revealing a maximum solubility for Fe-DTPA of 0.858 M. Figure 2c displays snapshots of the solutions at various concentrations of Fe-DTPA, showing how the reddish-brown color deepens with increasing solution concentrations. Similarly, we determined that Ce-DTPA has a maximum solubility of 0.927 M according to the absorption peak at 297 nm, which is marginally greater than Fe-DTPA’s maximum solubility (Fig. 2d–f). The fitting curve at 270 nm showed a consistent trend with that of 297 nm, and the results are similar (Supplementary Fig. 6). To further characterize the properties of the electrolytes, the viscosity and conductivity of Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA were investigated (Fig. 2g). Both Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA’s conductivity and viscosity displayed a similar trend with a change in concentration. Conductivity increased with concentration and remained high at concentrations more than 0.6 M, while the viscosity for both Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA remained nearly identical, making them suitable for use as the negolyte and posolyte, respectively. UV-vis spectra acquired after 3, 5, and 7 days of the diffusion experiment show negligible crossover of active species through the membrane (Fig. 2h, Supplementary Fig. 7), ensuring a stable CE for the battery. Membrane penetration is greatly reduced because of the chelation of DTPA, which introduces a significant steric hindrance effect for both Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA compared to just Fe3+ and Ce3+. Alongside this, the matched viscosity of negolyte and posolyte and ligands markedly lessens the diffusion driving force brought on from using different electrolyte components36.

a UV-vis absorption spectra and (b) absorbance-concentration plot at 258 nm of Fe-DTPA solutions diluted 1000-fold. c Digital photos of Fe-DTPA solutions with different concentrations. d UV-vis absorption spectra and (e) absorbance-concentration plot at 297 nm of Ce-DTPA solutions diluted 1000-fold. f Digital photos of different Ce-DTPA concentrations. g Viscosity and ionic conductivity of Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA at various concentrations. h Digital photos of Fe–Ce DTPA RFB penetration tests. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Electrochemical property study

The electrochemical characteristics of Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA electrolytes were evaluated using cyclic voltammetry (CV). Fe3+ and OH− are known to combine easily to form hydroxide, which is detrimental to flow battery operation as they increase pipeline pressure, cause leaks, and reduce battery capacity. We evaluated the CV curves of Fe-DTPA at different pH levels and found that the change in current density was within an acceptable range at pH = 4 to 9 (Supplementary Fig. 8a–d). 500-cycle tests of the solution component demonstrate that the stability is still good even when the pH is raised to 10 or 12; however, the current density is much decreased, and a precipitate was observed in the solution (Supplementary Fig. 8i–l). For Ce-DTPA, Supplementary Fig. 9 shows that there is no substantial difference between the potential and current density of the CV curves at pH = 4 and pH = 7, yet there is an irreversible reduction peak at pH = 9, and the cyclic stability deteriorates. This behavior is likely due to the permanent loss of active chemicals caused by partial hydroxides and oxides of Ce that arise following a decrease in H+ concentration. In conclusion, Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA operate optimally within the pH range of 4 to 7.

Based on these findings, subsequent investigations were performed under neutral pH conditions. CV measurements of Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA electrolytes were tested at a scan rate of 40 mV s−1, revealing that Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA exhibit a clear reversible redox pair with formal potentials of −0.28 V and 0.64 V (vs. saturated calomel electrode (SCE)), respectively (Fig. 3a). Therefore, 0.2 M Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA in the presence of 1.0 M NaCl supporting electrolyte can theoretically deliver a cell voltage of about 0.92 V. CV curves for other Fe / Ce-based electrolytes with 1.0 M NaCl are shown in Supplementary Fig. 10a; their theoretical voltages (IDA: 0.43 V, NTA: 0.69 V, EDTA: 0.87 V, and PDTA: 0.31 V) are all lower than that of DTPA (0.92 V). In addition, both Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA exhibit the highest current densities, confirming superior electrochemical activity. The electrochemical operating window of the DTPA solution (Fig. 3b) shows no significant redox activity, or any hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) or oxygen evolution reaction (OER) within the electrochemical window (between −1.31 V and 1.19 V vs. SCE) at pH = 7. CV tests were performed at different scan rates to further elucidate the electrolyte dynamics (Fig. 3c, f). These reveal a strong linear relationship between the scan rate and the square root of the current density (Fig. 3d, g). It is notable that both slopes of the fitted Log(I) vs. Log(v) lines are close to 0.5 (Supplementary Fig. 11), indicating a diffusion-controlled redox process. Furthermore, throughout the entire 500-cycle tests performed on Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA electrolytes, minimal variation can be seen between the representative 1st to 500th cycles shown in Fig. 3e, h, indicating long-term electrochemical stability (full cycle data are shown in Supplementary Figs. 12, 13).

a Cyclic voltammograms of 0.2 M Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA in the presence of 1.0 M NaCl supporting electrolyte recorded at a scan rate of 40 mV s−1. b Electrochemical window of DTPA electrolyte derived at a scan rate of 40 mV s−1. Cyclic voltammograms of (c) Fe-DTPA electrolyte and (f) Ce-DTPA electrolyte recorded at different scan rates. d, g Linear fitting curves of the square root of the scan rate to the current density. Representative cyclic voltammograms of (e) Fe-DTPA electrolyte and (h) Ce-DTPA electrolyte obtained at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 in 500-cycle tests. During the tests conducted at 25 ± 1 °C, the electrolytes were adjusted at pH = 7 with a concentration of 0.2 M. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Redox flow battery evaluation

The Fe-Ce DTPA RFB was assembled and the charge and discharge curves at various current densities (40 mA cm−2, 60 mA cm−2, 80 mA cm−2, 100 mA cm−2, and 120 mA cm−2) were measured, as shown in Fig. 4a. As the current density increases, the battery’s effective capacity decreases due to the decreased electrolyte usage caused by a higher ohmic polarization, which is a common trend in flow batteries. The open-circuit voltage (OCV) of the full cell at 50% SOC was measured to be 0.73 V (Supplementary Fig. 14a), which is lower than the output voltage obtained by CV in a single electrolytic cell (Fig. 3a). This discrepancy is likely due to the differences in electrolyte concentration, thus altering the activity ratio of oxidized and reduced species ([\({c}_{{{{\rm{Ox}}}}}{{{\rm{\cdot }}}}{{\gamma }}_{{{{\rm{Ox}}}}}\)] / [\({c}_{{{{\rm{Red}}}}}{{{\rm{\cdot }}}}{{\gamma }}_{{{{\rm{Red}}}}}\)]) according to the Nernst equation. To confirm this, further CV measurements were performed in full cells with 0.5 M Fe-DTPA and 0.5 M Ce-DTPA without supporting electrolyte, matching the electrolytes used in full battery tests (Supplementary Fig. 14b). The modified device included a saturated calomel reference electrode, enabling us to perform CV measurements under conditions more comparable to those of the full-cell tests (i.e., with a N212 membrane and 9 cm2 graphite felt electrodes). The obtained CV curves (Supplementary Fig. 14b–f) show that the voltage derived is about 0.74 V, close to the OCV at 50% SOC (Supplementary Fig. 14a).

a Voltage-capacity diagram of 0.5 M Fe-Ce DTPA RFB at different current densities (from 40 to 120 mA cm−2) and (b) corresponding efficiency and current densities. c Discharge voltage and power density plots vs. current density. Power densities are shown for the 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100% SOC, respectively. d Partial characteristic charge and discharge curve in full battery test at 40 mA·cm−2. e Efficiency and capacity data of the full battery test at 40 mA cm−2 for 500 cycles. f Cycle test of 0.5 M Fe-Ce DTPA RFB at 80 mA cm−2 under 70% SOC. In situ Raman spectra on (g) Fe-DTPA and (h) Ce-DTPA obtained from 0 to 100% SOC, with the real-time status of the corresponding electrolyte recorded. i Representative charge and discharge profiles and (j) performance of the·0.5 M Fe-Ce DTPA RFB stack at 80 mA cm−2. k CV curves of 0.2 M Fe-CN, Fe-DTPA, and Ce-DTPA solutions. l Efficiency and capacity of K3[Fe(CN)6] / K4[Fe(CN)6] electrolyte in a 1031 h cycling test. The inset in (l) shows the charge-discharge curves at the first 10 cycles and the last 10 cycles of the test. All electrochemical tests were performed at 25 ± 1 °C. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The as-assembled Fe-Ce RFB exhibited an EE of 87.7% and 80.6% at 40 mA cm−2 and 100 mA cm−2, respectively. The corresponding efficiency shown in Fig. 4b illustrates that the CE remained consistently at or close to 100%, indicating the significantly improved performance from the ligand chelation approach. Discharge voltage and power density plots at different SOCs demonstrate that 245 mA cm−2 provides a maximum power density of 108 mW cm−2 (Fig. 4c). The nearly linear discharge curve suggests that ohmic polarization is the primary factor governing battery discharge. Long-term battery cycling tests were used to assess the stability and longevity, as well as its capacity and EE (Fig. 4d, e). FTIR and Raman analyses after cycling confirm that the electrolyte structure remained largely unchanged, highlighting its stability (Supplementary Fig. 15). Representative cycles from a 500-cycle test (Fig. 4d) indicate minimal voltage variation throughout the course of the cycle. The discharge capacity after the cycling test retained 95.3% of the original capacity, with the EE peaking at around 86.3%, accompanied by a CE consistently close to 100% when cycled under neutral conditions (100% SOC). These performance metrics are superior to those measured for Fe-Ce DTPA RFBs operated in acidic or alkaline conditions (details are shown in Supplementary Figs. 16–18). However, testing with the thicker N117 membrane resulted in a decrease in battery efficiency (Supplementary Table 3, Supplementary Fig. 19). Comparative tests using other reference ligands cycled under identical conditions revealed varying degrees of instability (Supplementary Fig. 20).

After establishing the optimal operating parameters for a Fe-Ce DTPA RFB, we carried out a long-term cycling test at 80 mA cm−2 and 70% SOC (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 21). The results show that the capacity is almost unchanged over the 1779 cycles of operation. The 0.5 M Fe-Ce DTPA RFB also exhibited CE consistently close to 100% (Supplementary Fig. 22). Compared to other reported Ce-based RFBs, batteries featuring Fe-Ce DTPA exhibit a combination of high EE and long cycle life (Supplementary Fig. 23)37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47. In situ Raman tests provide additional evidence for the stability of the Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA coordination structures under different SOCs (Fig. 4g, h). Additionally, we discovered that the Ce-DTPA exhibits a noticeable color variation under various SOCs, allowing us to approximate the electrolyte’s SOC based on color, although no equivalent color change was observed for the Fe-DTPA. Self-discharge tests were performed (Supplementary Fig. 24), where the cell is fully charged at 40 mA cm−2 and then allowed to undergo static self-discharge, while the pump continues to operate until the battery voltage is lowered to below 0.3 V. The results demonstrate that the charge lasted about 0.5 h, while the self-discharge time lasted more than 351 h. We attribute this low level of self-discharge to our universal complexing agent approach. Furthermore, after fully charging the Fe-Ce DTPA RFB and resting for 3 days under open-circuit conditions, the battery retained a CE of 97.9%, further confirming its resistance to self-discharge (Supplementary Fig. 24b).

We assembled an RFB stack with five single cells and an active area of 14.5 × 7.5 cm2 to evaluate the viability of a Fe-Ce DTPA RFB (Supplementary Fig. 25). Representative cycles (Fig. 4i) show the cycling stability and utility. An EE of 80.8% was achieved at a current density of 80 mA cm−2, as illustrated in Fig. 4j. Additionally, a decoupling method with K3[Fe(CN)6] / K4[Fe(CN)6] (positioned between the potentials of Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA, Fig. 4k), which showed almost no change in capacity and efficiency over 2000 cycles in a symmetric battery test (Fig. 4l), was utilized to demonstrate that Fe-Ce DTPA RFB’s total EE may be further improved by enhancing both the voltage efficiency (VE) of the Ce-DTPA side and the CE of the Fe-DTPA side. Detailed discussion is provided in the Supplementary Information and Supplementary Figs. 26–29.

Discussion

In this work, we present an aqueous redox flow battery based on a universal complexing agent strategy, utilizing Fe-DTPA and Ce-DTPA as active substances. Coordination chemistry was leveraged to tune redox properties and electrochemical stability, enabling reliable operation in a neutral environment. The use of the same DTPA ligand for both the negolyte and posolyte minimizes osmotic pressure and viscosity differences between negolyte and posolyte, thereby reducing ligand crossover and water migration across the membrane. In a neutral environment, we found that Fe-Ce DTPA RFB operates steadily for 500 cycles, with CE consistently approaching 100%, EE reaching 86.3%, and the discharge capacity remaining at 95.3% of the starting capacity after cycling. Furthermore, capacity remains unchanged over 1779 cycles at a rate of 80 mA cm−2 (70% SOC). The electrochemical stability of the Fe-Ce DTPA RFB suggests promise for use not just in energy storage peak regulation, but also in power grid frequency modulation, broadening the application range of RFB technology.

Methods

Chemicals

Diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (DTPA, AR), iminodiacetic acid (IDA, AR), nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA, AR), ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA, AR), 1,3-propylenediaminetertaacetic acid (PDTA, AR), anhydrous potassium carbonate (K2CO3, 99%), cerium chloride heptahydrate (CeCl3‧7H2O, 99%), ferric chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3‧6H2O, 99%), potassium chloride (KCl, 99%), potassium ferrocyanide trihydrate (K4[Fe(CN)6]‧3H2O, AR), and potassium ferricyanide (K3[Fe(CN)6], AR) were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., LTD. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99%) was bought from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., LTD. All chemicals were stored in an inert gas glovebox to prevent water exposure and used without any treatment. The deionized water (DIW, 18.2 MΩ cm) was boiled under reduced pressure to remove the dissolved oxygen and carbon dioxide, and stored in reagent bottles filled with nitrogen.

Commercial Nafion membranes were purchased from Chemours. For acidic environment studies, membranes were soaked at 80 °C in 5% H2O2 for 1 h, in 0.5 M H2SO4 for 1 h, and in deionized water for 0.5 h before use. For alkaline environment studies, membranes were immersed in 1 M NaOH and 1.0 M KCl solution for 2 h. Membranes were then stored in deionized water, ready for use. The membranes need to be first soaked in electrolytes before electrochemical tests.

Graphite felts were bought from Liaoning Jin Gu Carbon Material Co., Ltd. and cleaned with acetone, ethanol, and deionized water (DIW). After impurity removal, graphite felts were annealed in the air at 500 °C for 5 h. The graphite felts should be removed from the floating fiber before use and fully soaked in the electrolytes.

Flow battery (LSB-1, YTH-1, 3 cm × 3 cm) subassemblies were provided by Wuhan Zhi Sheng New Energy Co., LTD. All parts of the devices in contact with the electrolytes are made of anti-corrosion materials. Some components in our battery devices, such as gaskets and electrode frames, were purpose-built for our application. The customized gaskets are made of polytetrafluoroethylene or ethylene propylene diene monomer. The central area of customized gaskets matches the active area of the battery, and the thickness can be 0.1, 0.2, or 0.5 mm, depending on the specific requirements. The peristaltic pumps were purchased from Baoding River Fluid Technology Co., LTD. All battery tests were performed with the CT3002K battery testing system purchased from Wuhan Land Electronics Co., Ltd. The battery stack with five single cells (FSS-SK, testing bench WHZS-STS-QP) and an active area of 14.5 × 7.5 cm2 were custom-made by Wuhan Zhi Sheng New Energy Co., LTD.

Preparation of 0.5 M Fe-based electrolytes

33.79 g of FeCl3‧6H2O and 49.17 g of DTPA were added into 200 mL of deoxidized DIW and fully stirred for 10 min at 20 °C. Then 51.83 g of K2CO3 was gradually added to the solution and stirred for 24 h until a uniform solution formed. K2CO3 was used to deprotonate the DTPA ligand and enable stable metal–ligand complexation, while avoiding rapid pH rise and metal hydroxide precipitation. Under the monitoring of a pH meter, we adjusted the pH to 4, 7, or 9 with HCl or KOH solution. Finally, the volume of the solution after ultrasonic defoaming was adjusted to 250 mL with deoxidized DIW. All preparation steps were conducted under a nitrogen atmosphere to avoid oxidation and absorption of carbon dioxide. The configuration of other Fe-based electrolytes is similar to the above process, simply replacing DTPA with IDA, NTA, EDTA, PDTA and adjusting the pH to a neutral level.

Preparation of 0.5 M Ce-based electrolytes

Similar to the preparation of solution Fe-DTPA, 46.57 g of CeCl3‧7H2O and 49.17 g of DTPA were added into 200 mL of deoxidized DIW and fully stirred for 10 min at 20 °C. Then 51.83 g of K2CO3 was gradually added to the solution and stirred for 24 h until a uniform solution formed. Under the monitoring of a pH meter, we adjusted the pH to 4, 7, or 9 with HCl or KOH solution. Finally, the volume of the solution after ultrasonic defoaming was adjusted to 250 mL with deoxidized DIW. The entire configuration process was prepared in a nitrogen environment to avoid oxidation and absorption of carbon dioxide. Other Ce-based electrolytes are similar to the above process, simply replacing DTPA with IDA, NTA, EDTA, or PDTA, and adjusting the pH to neutral.

Preparation of K4Fe(CN)6 (K3Fe(CN)6) electrolytes

52.8 g of K4Fe(CN)6 (41.16 g of K3Fe(CN)6) and 9.32 g of KCl were dissolved into 200 mL deoxidized DIW and stirred for 30 min. Under the monitoring of a pH meter, the pH was adjusted to 7. The solution was adjusted to 250 mL with deoxidized DIW at normal temperature.

Electrochemical measurements

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements were performed at 25 ± 1 °C at different sweep rates from 10 mV s−1 to 50 mV s−1 using a standard three-electrode system consisting of a graphite working electrode (6 mm in diameter), a saturated calomel reference electrode with KCl salt bridge, and a platinum network (1 cm2) counter electrode on a CHI660 electrochemical workstation (Shanghai Chen Hua Instrument Co., LTD). 15 mL of different Fe-based negolyte and Ce-based posolyte in the presence of 1.0 M NaCl supporting electrolyte were used for CV tests. The electrochemical cell was purged with nitrogen to remove air before the CV tests. As for evaluating the electrochemical window of DTPA electrolyte by CV, the electrolyte was prepared by dissolving 49.17 g of DTPA in 200 mL of deoxygenated deionized water under stirring for 10 min at 20 °C. Subsequently, 51.83 g of K2CO3 was gradually added to the solution, followed by continuous stirring for 24 h until a homogeneous solution was obtained. The pH of the final electrolytes was adjusted to 7 by adding HCl or KOH solution.

CV measurements were also performed in a full cell for 0.5 M Fe-DTPA and 0.5 M Ce-DTPA with a saturated calomel reference electrode under similar battery operating conditions.

Battery tests

The flow battery system was assembled by connecting a battery device to the negolyte and posolyte tanks through two peristaltic pumps and an anti-corrosion silicone tube. A battery structure with two prepared graphite felt electrodes with an effective area of 9 cm2 was used on each side of a membrane as positive and negative electrodes, and handmade Teflon gaskets were employed to control the electrode compression ratio. The entire battery system was cleaned with nitrogen before the test began to ensure the absence of oxygen and carbon dioxide. The peristaltic pump pushed the electrolyte from the tank into the battery stack at a flow rate of 100 mL min−1. In the rate performance tests, five charging and discharging cycles were evaluated at each current density, batteries were charged to 1.0 V and discharged to 0.3 V at a current density of 40 mA cm−2 to 120 mA cm−2. For the long cycle tests (under 100% SOC unless stated otherwise) at a current density of 40 mA cm−2 with 15 mL electrolytes, batteries were charged to 1.0 V and discharged to 0.3 V (N212 membrane). The longer cycle tests with 15 mL electrolytes were charged at 80 mA cm−2 to 70% SOC, or cutoff at 1 V (N211 membrane), avoiding the high-voltage regime where polarization and parasitic reactions dominate. Fe-DTPA / K4[Fe(CN)6] RFB and K3[Fe(CN)6] / Ce-DTPA RFB assembled by N212 membrane.

Computational details

To analyze the coordination structure of Fe-based or Ce-based electrolytes, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and density function theory (DFT) were performed using Gaussian 09 and the GROMACS package, respectively. All the geometric optimizations of each individual ion and each individual molecular compound were performed at the B3LYP / 6-31 + G (d, p) theoretical level, and the solution is water. The force field parameters were obtained from General Amber Force Field (GAFF) and assigned with RESP charges. The size of the box is 10 × 10 × 10 nm3, and periodic boundary conditions were set in all three directions. FeCl3 / CeCl3, IDA / NTA/ EDTA / PDTA / DTPA, K+, Cl−, and H2O were randomly filled into simulated chambers with different molecular ratios. The Packmol software was used to build all the initial structures of the cell. The electrostatic interaction was calculated by the PME method. A cutoff length of 1 nm was used for the calculation of electrostatic and non-electrostatic interactions in real space. In order to obtain a reasonable initial configuration, the fastest descent integration protocol was used to minimize the energy. The system then anneals from 0 to 298 / 263 K in a time of 0.5 ns, and then runs another 1 ns to reach equilibrium. Finally, the Parrinello-Rahman method of 10 ns NPT was performed once, and the stable product was obtained. The final 5 ns was sampled for radial distribution function (RDF) and coordination structure counting analyses.

Physical characterization

The conductivity was measured using a DDSJ-308F conductivity meter equipped with a DJS-1VTC electrode. Prior to the measurements, the instrument was calibrated at 25 °C using standard solutions. After calibration, the electrode was thoroughly rinsed and immersed in the electrolyte samples. The measurements were carried out at a constant temperature of 25 °C, and the final conductivity value was automatically recorded once the instrument reading stabilized. To confirm the coordination structure and component of the samples, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were measured on an FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, Nicolet 6700, USA). Raman and in situ Raman spectroscopy (inVia Reflex) were conducted to analyze the solvation structural evolution (514 nm laser wavelength). During the test, a small amount of electrolyte is exported synchronously through the branch to observe the color and electrolyte state. Then, a pipette was used to immediately take an appropriate amount of liquid and store it in a sample bottle filled with nitrogen. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of samples were collected on an X-ray diffractometer (XRD-6000) with Cu Kα radiation ranging from 10 to 90° at a scan rate of 5° / min. After the battery tests, the battery device was removed from the testing station, and the inlet and outlet ports were sealed with rubber stoppers. The battery device was then transferred into the glovebox, where the electrodes were disassembled and sealed for subsequent measurements. The Fe K-edge extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra were measured at BL01C at the Taiwan Light Source, NSRRC. Fe-DTPA solutions were directly used at room temperature without further treatment. Before the analysis at the beamline, samples were placed into aluminum sample holders and sealed using Kapton tape film. The energy resolution (ΔE/E) for incident X-ray photons was found using a Si(111) double crystal monochromator. EXAFS spectra were recorded in transmission mode and obtained by subtracting the post-edge background from the overall absorption and then normalizing with respect to the edge-jump step. Subsequently, the χ(k) data were Fourier transformed to real (R) space using a Hanning window (dk = 1 Å−1) to separate the EXAFS contributions from different coordination shells.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Carrington, M. E. et al. Associative pyridinium electrolytes for air-tolerant redox flow batteries. Nature 623, 949–955 (2023).

Ai, F. et al. Heteropoly acid negolytes for high-power-density aqueous redox flow batteries at low temperatures. Nat. Energy 7, 417–426 (2022).

Feng, R. et al. Reversible ketone hydrogenation and dehydrogenation for aqueous organic redox flow batteries. Science 372, 836–840 (2021).

Robb, B. H., Farrell, J. M. & Marshak, M. P. Chelated chromium electrolyte enabling high-voltage aqueous flow batteries. Joule 3, 2503–2512 (2019).

Waters, S. E., Davis, C. M., Thurston, J. R. & Marshak, M. P. Maximizing vanadium deployment in redox flow batteries through chelation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 17753–17757 (2022).

Scott, E. W., Brian, H. R. & Michael, P. M. Effect of chelation on iron–chromium redox flow batteries. ACS Energy Lett 5, 1758–1762 (2020).

Park, M., Ryu, J., Wang, W. & Cho, J. Material design and engineering of next-generation flow-battery technologies. Nature Rev. Mater. 2, 16080 (2016).

Zhao, Z. et al. Development of flow battery technologies using the principles of sustainable chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 6031–6074 (2023).

Zhang, X., Li, W. & Chen, H. High-capacity CuSi2P3-based semisolid anolyte for redox flow batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 40552–40561 (2021).

Zhi, L. et al. New alkalescent electrolyte chemistry for zinc-ferricyanide flow battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202403607 (2024).

Yu, Z. et al. Electrolyte engineering for efficient and stable vanadium redox flow batteries. Energy Storage Mater 69, 103404 (2024).

Xing, F. et al. Highly active hollow porous carbon spheres@graphite felt composite electrode for high power density vanadium flow batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2111267 (2022).

Agarwal, H. et al. Electrode treatments for redox flow batteries: translating our understanding from vanadium to aqueous-organic. Adv. Sci. 11, e2307209 (2024).

Wei, J. et al. Energy density boosted vanadium colloid flow batteries realized by a reversible nanoparticle suspension-dissolution strategy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2314956 (2024).

Zhu, F., Guo, W. & Fu, Y. Functional materials for aqueous redox flow batteries: merits and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 8410–8446 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Regulated adsorption capability by interface-electric-field enabling promoted electrochemical kinetics of zinc-bromine flow batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 486, 150317 (2024).

Huang, K. et al. Porous ceramic metal-based flow battery composite membrane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202401558 (2024).

Wei, X. et al. Materials and systems for organic redox flow batteries: status and challenges. ACS Energy Lett 2, 2187–2204 (2017).

Jang, J. E. et al. Full-hexacyanometallate aqueous redox flow batteries exceeding 1.5 V in an aqueous solution. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2300707 (2023).

Li, X. et al. A complexing agent to enable a wide-temperature range bromine-based flow battery for stationary energy storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2100133 (2021).

Ling, R. et al. Dual-function electrolyte additive design for long-life alkaline zinc flow batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, e2404834 (2024).

Kwabi, D. G. Molecular engineering expands the chemical possibilities for organic flow batteries. Joule 5, 1636–1638 (2021).

Sun, J., Shi, D., Zhong, H., Li, X. & Zhang, H. Investigations on the self-discharge process in vanadium flow battery. J. Power Sources 294, 562–568 (2015).

Chou, Y.-S., Devi, N., Yen, S.-C., Singh, P. & Chen, Y.-S. Study on the self-discharge of an all-vanadium redox flow battery through monitoring individual cell voltages. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 10, 12245–12251 (2022).

Hruska, L. W. & Savinell, R. F. Investigation of factors affecting performance of the iron-redox battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 128, 18–25 (1981).

Noh, C., Chung, Y. & Kwon, Y. Organometallic redox flow batteries using iron triethanolamine and cobalt triethanolamine complexes. J. Power Sources 466, 228333 (2020).

Shin, M., Noh, C., Chung, Y. & Kwon, Y. All-iron aqueous redox flow batteries using organometallic complexes consisting of iron and 3-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino-2-hydroxypropanesulfonic acid ligand and ferrocyanide as redox couple. Chem. Eng. J. 398, 125631 (2020).

Shin, M., Noh, C. & Kwon, Y. Stability enhancement for all-iron aqueous redox flow battery using iron-3-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-hydroxypropanesulfonic acid complex and ferrocyanide as redox couple. Int. J. Energy Res. 46, 6866–6875 (2021).

Nambafu, G. S. et al. Phosphonate-based iron complex for a cost-effective and long cycling aqueous iron redox flow battery. Nat. Commun. 15, 2566 (2024).

Gong, K. et al. All-soluble all-iron aqueous redox-flow battery. ACS Energy Lett 1, 89–93 (2016).

Yang, J. et al. High-stable all-iron redox flow battery with innovative anolyte based on steric hindrance regulation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202414452 (2025).

Xie, X., Mushtaq, F., Wang, Q. & Daoud, W. A. The renaissance of the Zn–Ce flow battery: dual-membrane configuration enables unprecedentedly high efficiency. ACS Energy Lett 7, 3484–3491 (2022).

Modiba, P., Matoetoe, M. & Crouch, A. M. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy study of Ce(IV) with aminopolycarboxylate ligands for redox flow battery applications. J. Power Sources 205, 1–9 (2012).

Schmickler, W., Nazmutdinov, R. R., Wang, Q. & Daoud, W. A. Electrochemistry of Ce(IV)/Ce(III) redox couples in mixed solutions for aqueous flow battery: Experimental and molecular modelling study. Electrochim. Acta 368, 137601 (2021).

Leung, P. K., Ponce-de-León, C. & Walsh, F. C. The influence of operational parameters on the performance of an undivided zinc-cerium flow battery. Electrochim. Acta 80, 7–14 (2012).

Song, Y. et al. Electrolyte transfer mechanism and optimization strategy for vanadium flow batteries adopting a Nafion membrane. J. Power Sources 449, 227503 (2020).

Leung, P. K., Ponce-de-León, C., Low, C. T. J., Shah, A. A. & Walsh, F. C. Characterization of a zinc–cerium flow battery. J. Power Sources 196, 5174–5185 (2011).

Li, Y. et al. Cerium-containing complexes for low-cost, non-aqueous redox flow batteries (RFBs). J. Power Sources 450, 227634 (2020).

Yu, H., Pritzker, M. & Gostick, J. Use of Mixed methanesulfonic acid/sulfuric acid as positive supporting electrolyte in Zn–Ce redox flow battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 170, 020536 (2023).

Na, Z., Yao, R., Yan, Q., Sun, X. & Huang, G. General growth of carbon nanotubes for cerium redox reactions in high-efficiency redox flow batteries. Res 2019, 3616178 (2019).

Na, Z., Wang, X., Liu, X., Li, W. & Sun, X. O/N/S trifunctional doping on graphite felts: A novel strategy toward performance boosting of cerium-based redox flow batteries. Carbon Energy 3, 752–761 (2021).

Wu, Y. et al. A green europium-cerium redox flow battery with ultrahigh voltage and high performance. Chem. Eng. J. 500, 157189 (2024).

Kocyigit, N., Gencten, M., Sahin, M. & Sahin, Y. A novel electrolyte for redox flow batteries: Cerium and chromium couples in an aqueous system. Int. J. Energy Res. 45, 16176–16188 (2021).

Na, Z., Xu, S., Yin, D. & Wang, L. A cerium–lead redox flow battery system employing a supporting electrolyte of methanesulfonic acid. J. Power Sources 295, 28–32 (2015).

Leung, P. K., Ponce-de-León, C. & Walsh, F. C. An undivided zinc–cerium redox flow battery operating at room temperature (295 K). Electrochem. Commun. 13, 770–773 (2011).

Wu, J. et al. Boosting the kinetics of Ce3+/Ce4+ redox reaction by constructing TiC/TiO2 heterojunction for cerium-based flow batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2309825 (2023).

Chang, T. C. et al. Cerium/ascorbic acid/iodine active species for redox flow energy storage battery. Molecules 26, 3443 (2021).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22372007 and 21972010) and the Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24B20201).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y. designed and performed most of the experiments and wrote the draft. W.W. and A.T. conducted the calculations. C.Z. helped perform some battery measurements. T.W., Y.Z., Y.S., and M.L. carried out XAFS measurements and analyses. A.R. helped polish the language. X.T., A.T., and Z.S. revised the manuscript. Z.S. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Juezhi Yu and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Wei, W., Zhou, C. et al. Universal complexing agent enabling advanced iron-cerium redox flow batteries. Nat Commun 17, 1119 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67878-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67878-z