Abstract

Full-length gene-humanized mice engineered by completely replacing mouse loci with human counterparts, including untranslated and regulatory regions, provide a robust in vivo platform for human gene function studies. However, reliably humanizing large genomic regions remains challenging due to limited DNA insert sizes, complex protocols, and specialized material requirements. This study introduces a streamlined approach that enables full-length gene humanization through two sequential CRISPR-assisted homologous recombination steps in embryonic stem cells. This method supports targeted knock-in of genomic fragments ( > 200 kbp) and is applicable across multiple mouse strains. Humanized alleles generated using the developed method recapitulate human-like splicing isoforms and organ-specific gene expression while restoring essential functions in hematopoiesis, spermatogenesis, and survival. Furthermore, disease-associated mutations can be engineered into humanized alleles to model human genetic disorders in vivo. This versatile platform enables the creation of physiologically relevant, fully gene-humanized mouse models for broad applications in biomedical research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mice are widely used as model organisms in biomedical research, sharing approximately 99% of genes with humans1. However, substantial differences in untranslated and regulatory regions can result in species-specific patterns of tissue- and cell-type–specific gene expression2,3,4,5,6,7, limiting the suitability of these models for studying certain human biological processes. Replacing entire mouse gene loci with their corresponding human orthologs—known as full-length gene humanization (FL-GH)—has shown promise in addressing these limitations by enabling the development of mouse models that more accurately replicate human gene regulation8.

Implementing FL-GH typically involves replacing large genomic regions spanning tens to hundreds of kilobases. Characterized by high homologous recombination (HR) efficiency and drug selection compatibility, embryonic stem (ES) cells remain the conventional method for generating genetically modified mice9,10,11. Nevertheless, vector constraints restrict conventional HR-based gene targeting in ES cells to ~10 kbp inserts8. Consequently, most reported humanizations have been partial, targeting individual residues12,13,14, specific exons15,16,17,18,19, or functional domains20,21, with no previous reports achieving FL-GH of genomic segments exceeding 10 kbp using straightforward conventional targeting methods22.

The introduction of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC)-based targeting vectors—capable of carrying >200 kbp genomic DNA fragments—has enabled successful FL-GH attempts for larger genes22,23,24,25,26,27. One representative example is the sequential humanization of the immunoglobulin locus, achieved through six rounds of recombination (144, 196, 210, 105, 195, and 90 kbp, respectively), albeit with very low overall efficiency (0.1%–0.5%)24. CRISPR/Cas9-assisted genome editing has markedly improved targeting efficiencies in ES cells28,29,30, facilitating FL-GH for gene loci larger than 100 kbp via HR-based strategies31,32,33. Long-fragment knock-in of over 100 kbp has also been achieved using non-cell-intrinsic machinery–based approaches, such as exogenous recombinase-mediated genomic replacement34,35 and recombinase-mediated cassette exchange36. However, most existing FL-GH methods lack broad applicability owing to their inherent reliance on specialized enzyme–recombination site systems, overly long homology arms (> 50 kbp), rare customized vectors, and pre-optimized ES cell lines. In addition, their complex multistep protocols typically require prolonged in vitro culture, reducing ES cells’ chimera formation and germline transmission efficiency.

To address these limitations, we developed a two-step CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing strategy in mouse ES cells (Two-step ES Cell-based HumaNizatiOn; TECHNO) that enables efficient and stable FL-GH exceeding 200 kbp. Notably, this method’s key strength lies in its exclusive use of standard molecular biology reagents and readily available BAC resources, enabling theoretical humanization of >90% of human genes. We systematically evaluated knock-in efficiency across multiple loci, mouse strains, and homology arm lengths and assessed the expression and functionality of the humanized genes in vivo. Our results demonstrate a robust and broadly applicable platform for generating FL-GH mouse models.

Results

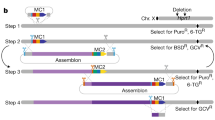

A strategy for FL-GH by two-step genome editing in mouse ES cells

To enable efficient FL-GH, we developed a two-step genome editing strategy in mouse ES cells. FL-GH ES cell lines were generated through two sequential electroporation and drug selection steps. The first step involves removing the target locus by introducing locus-specific Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNPs), which enable efficient genome editing in ES cells30. Homology arms targeting the upstream and downstream sequences of the human gene region are then simultaneously integrated with a neomycin-resistant cassette via HR (Fig. 1a, left). The second step involves introducing a full-length human genomic fragment (delivered via BAC) and a blasticidin resistance cassette through HR, using the homology arms inserted in the first step (Fig. 1a, right). Currently, BAC libraries containing human genomic sequences are widely available37. Given the insert size limitation of BACs, our strategy can, in principle, humanize genes up to approximately 200 kbp in length, encompassing 93% of all human genes (Fig. 1b).

a Schematic of a two-step genome editing protocol for full-length gene humanization (FL-GH) in embryonic stem (ES) cells. b Pi chart showing the distribution of human protein-coding gene length (n = 19890). Data were obtained from GRCh38.p14 (GCF_000001405.40). Gene size was defined as the length from the TSS of the most upstream isoform to the 3’UTR of the most downstream isoform among the splicing variants of that gene. c Schematic illustration of the knock-in strategy targeting the full-length hKIT genomic region into the Rosa26 locus. d Number of G418-resistant ES cell colonies obtained after the first step. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments with or without Rosa26-RNP (unpaired t-test, two-tailed). e Knock-in efficiency of the hKIT homologous arms based on genotyping PCR of G418-resistant ES cell colonies after the first step. Data are presented as means ± SD of three independent experiments (ordinary one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). f Number of blasticidin-resistant ES cell colonies obtained after the second step. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments with or without NeoR-RNP and BAC (ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). g Knock-in efficiency of the hKIT locus based on genotyping PCR of blasticidin-resistant ES cell colonies after the second step. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments with or without NeoR-RNP (unpaired t-test, two-tailed). h One representative genotyping PCR of blasticidin-resistant ES cell colonies obtained after the second step is shown in (g). i Sequence analysis of the junction between the Rosa26 locus and the hKIT genomic region using the PCR product in Fig. 1h. j Copy number analysis of the ES cell clones obtained in the second step using primers targeting the PGK-Bsd cassette. Data are presented as the means ± SD of biological triplicates. Copy numbers are shown relative to control ES cells carrying homozygous PGK-Bsd cassettes. The proportion of humanized ES cell clones with a single copy BAC knock-in was 6/8. k FISH analysis of an ES cell clone (#21) obtained in the second step using a probe targeting the hKIT genomic region. The red arrowhead indicates the predicted integration site of the human gene on the metaphase chromosome spread. l Quantitative PCR analysis of hKIT expression in the ES cell clones obtained in the second step. Data are presented as the means ± SD of biological triplicates. Expression levels relative to those in #6 ES cell clone are shown. m Representative immunofluorescence images showing mouse and human c-KIT expression in ES cell clones obtained in the second step. Eight independent clones were analyzed, and all clones were positive for Human c-KIT. Scale bars: 100 µm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Knock-in of a full-length human genomic region into the Rosa26 locus

To assess the feasibility of our strategy, we performed a knock-in of the full-length human c-KIT (hKIT) genomic region (~ 100 kbp) into the Rosa26 locus (Fig. 1c). Initially, 1-kbp sequences from the upstream and downstream regions of the hKIT gene were cloned into a vector containing a neomycin-resistant cassette. These hKIT homology arms were then further flanked by Rosa26-derived homology arms, which were also included in the vector. In the first step, 1.0 × 105 mouse ES cells (V6.5: C57BL/6 × 129SvJae) were electroporated with this targeting vector and Cas9-RNP specific for the Rosa26 locus (Rosa26-RNP), followed by G418 selection (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). The exclusive appearance of resistant colonies in the presence of Rosa26-RNP (Fig. 1d) suggests minimal random integration during the first step. Genotyping PCR of the G418-resistant colonies showed that the hKIT homologous arms were integrated into the Rosa26 locus with ~80% efficiency (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 1c). For the second step, we used an ES cell line heterozygous for the hKIT homology arms. A blasticidin resistance cassette was inserted into the BAC containing the full-length hKIT genomic fragment. The modified BACs were then electroporated into the 1.0 × 107 ES cell line alongside a Cas9-RNP targeting the neomycin-resistant cassette (NeoR-RNP), followed by blasticidin selection (Supplementary Fig. 1d, e). Resistant colonies emerged only in the RNP (+) condition and rarely without the RNP (−) condition (Fig. 1f). Genotyping revealed successful knock-in in ~30.2% of RNP (+) colonies (Fig. 1g, h, Supplementary Fig. 1f). All knock-in-positive clones exhibited the expected recombination junction between the Rosa26 locus and the hKIT region (Fig. 1i). In contrast, no knock-in was detected in RNP(–) colonies, despite blasticidin resistance, suggesting random integration of the BAC38,39 (Supplementary Fig. 1g). To assess random integration, we quantified the BAC copy numbers. While some clones showed multiple insertions, most did not display unintended integration (Fig. 1j). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) with an hKIT probe confirmed single-copy integration in a representative clone (Fig. 1k). Consistent with genomic data, expression of hKIT mRNA (exons 4–5 and 17–18) was detected in all clones (Fig. 1l), and hKIT protein expression was confirmed by immunostaining with a human-specific antibody (Fig. 1m). These results demonstrate that our two-step genome editing strategy enables the efficient knock-in of full-length human genomic regions into mouse ES cells.

Full-length humanization of the mouse c-Kit locus

Next, to humanize the full-length mouse c-Kit locus (Fig. 2a), we replaced the Rosa26 homology arms in the targeting vector with sequences homologous to regions upstream and downstream of the mouse c-Kit gene. In the first step, mouse ES cells were electroporated with this targeting vector and a Cas9 RNP specific to the c-Kit locus (c-Kit-RNP) (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). When 1.0 × 10⁵ cells were used, no G418-resistant colonies were obtained, whereas multiple colonies emerged when 1.0 × 10⁶ cells were used (Fig. 2b), indicating lower editing efficiency at the c-Kit locus compared to Rosa26. Genotyping of these colonies showed that the hKIT homology arms were integrated with ~60% efficiency (Fig. 2c). In the second step, BACs carrying the full-length hKIT genomic region were introduced into 1.0 × 107 ES cell lines heterozygous to the hKIT homology arms. Blasticidin-resistant colonies were picked and genotyped (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 2c). Using 1-kbp human homology arms, knock-in bands were detected with ~5% efficiency (Fig. 2e). DNA sequencing of the knock-in clones confirmed precise HR at the mouse c-Kit locus (Fig. 2f). Importantly, extending the human homology arms from 1 kbp to 3 kbp markedly increased the number of resistant colonies and the knock-in efficiency to over 10% (Fig. 2d, e). In contrast, no knock-in clones were obtained with 0- or 100-bp homology arms, indicating that BAC knock-in efficiency depends on homology arm length. To assess the functionality of the humanized c-Kit allele in vivo, c-Kit-humanized ES cells were injected into blastocysts to generate chimeric mice (Supplementary Fig. 2d), and germline transmission of the modified allele was confirmed (Fig. 2g). While c-Kit null mice die during fetal development or within one week after birth40, crosses between heterozygous c-Kit-humanized mice yielded wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous offspring at Mendelian ratios (Fig. 2g, lower panel). Although some homozygous mice exhibited white spotting, they survived for at least 8 weeks without any obvious health issues (Fig. 2g, upper panel and Supplementary Fig. 2e). These results suggest that the humanized c-Kit allele can compensate for the essential functions of the native mouse gene. RNA-seq analysis of spermatogonia from homozygous c-Kit-humanized mice revealed the expression of all 21 exons of the hKIT gene, with a splicing pattern similar to that observed in human cells41 (Fig. 2h). Additionally, the variable tissue-specific expression pattern of hKIT in c-Kit-humanized mice was similar to that in humans (Fig.2i). Immunostaining using a hKIT-specific antibody showed expression in the cerebellar molecular layer, pulmonary macrophages, and kidney collecting ducts—consistent with the expression pattern observed in human tissues42 (Fig. 2j, Supplementary Fig. 2f-h)—but not in the heart or pancreas (Supplementary Fig. 2h). These findings indicate that the organ-specific expression of hKIT can be recapitulated in humanized mice. Consistent with preserved c-KIT function, homozygous mice showed no significant body weight differences compared to wild-type or heterozygous mice (Fig. 2k). Unlike c-Kit null mutants, mice harboring a single amino acid substitution (c-KitWv) are viable but suffer from anemia and infertility40,43. In our model, although the average values did not differ significantly, half of the homozygous mice showed anemia-like features—reduced red blood cell counts and hemoglobin levels—while the other half exhibited normal hematological parameters (Fig. 2l, Supplementary Fig. 2i). Homozygous mice exhibited significantly lower testis weights than wild-type and heterozygous animals, with some seminiferous tubules showing histological abnormalities (Fig. 2m, n). Sperm from homozygous mice showed variable fertilization ability when used for in vitro fertilization (IVF) with wild-type oocytes (Supplementary Fig. 2j). Notably, viable heterozygous offspring were obtained from these embryos (Fig. 2o). Overall, these findings demonstrate that our method enables FL-GH of an ~100-kbp region and that the hKIT gene can partially substitute for the in vivo function of the mouse c-Kit gene.

a Schematic illustration of FL-GH of the mouse c-Kit locus. b Number of G418-resistant ES cell colonies after the first step. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments under different ES cell numbers (1 × 105 or 1 × 106) and with or without c-Kit-RNP (ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). c Knock-in efficiency of hKIT homology arms based on genotyping PCR of G418-resistant ES cell colonies obtained after the first step. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments (ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). d Number of blasticidin-resistant ES cell colonies obtained after the second step under varying human homology arm lengths (0, 0.1, 1, or 3 kbp). Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments (ordinary one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). e Knock-in efficiency at the hKIT locus based on the genotyping PCR of blasticidin-resistant ES cell colonies obtained after the second step under different human homology arm lengths (0, 0.1, 1, 3 kbp). Data are presented as means ± SD of three independent experiments (ordinary one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). f Sequence analysis of the junction between the mouse c-Kit locus and the human c-KIT genomic region in c-Kit-humanized ES cell clones. g Representative images of heterozygous and homozygous c-Kit-humanized F2 mice at 4 weeks of age, and offspring genotypic ratios from heterozygous F1 intercrosses (Chi-square test, two-tailed, P = 0.6065). h RNA-seq analysis showing specific hKIT expression peaks and splicing patterns in spermatogonia of heterozygous c-Kit-humanized mice, with reads detected across all 21 exons. For comparison, RNA-seq data of human spermatogonia were obtained from GSE9228041. i Heatmap showing tissue-specific expression patterns of hKIT gene between human and humanized mice across the indicated organs. For human gene expression data, we used TPM values from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Portal (Cerebellum: n = 266, Testis: n = 414, Heart: n = 452, Muscle: n = 818)46, and for humanized mouse gene expression, we used relative expression values obtained by qPCR (normalized to Actb). After calculating z-scores for each dataset, we visualized the expression patterns as heatmaps. j Representative immunobiological images showing hKIT protein expression in various organs of c-Kit-humanized mice. Two independent c-Kit-humanized mice were analyzed and yielded similar results. Scale bars: 200 µm. k Body weights of c-Kit-humanized mice (wild-type, n = 8; heterozygous hKIT, n = 21; homozygous hKIT, n = 8). Data are presented as means ± SD of biologically independent mice (two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). l Hematological parameters of c-Kit-humanized mice (wild-type, n = 5; heterozygous hKIT, n = 6; homozygous hKIT, n = 8). Graphs show the red blood cell (left) and hemoglobin (HGB, right). Data are presented as means ± SD of biologically independent mice (ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). m Representative testis image and testis/body weight ratio in c-Kit-humanized mice (wild-type, n = 6; heterozygous hKIT, n = 7; homozygous hKIT, n = 5). Data are presented as means ± SD of biologically independent mice (ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). Scale bar: 5 mm. n Representative PAS staining images of the testis in homozygous c-Kit-humanized mice. Three independent c-Kit-humanized mice were analyzed and yielded similar results. Scale bar: 500 μm (low) and 100 μm (high). o F3 offspring derived from the sperm of homozygous c-Kit-humanized male mice via in vitro fertilization with wild-type oocytes. Genotyping PCR confirmed that all offspring were heterozygous for the humanized c-Kit allele (WT: 399 bp, humanized: 221 bp). In vitro fertilization was performed using three independent c-Kit-humanized males, and all offspring obtained were subjected to genotyping. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

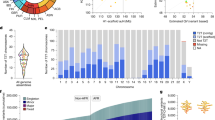

Full genomic replacement of a mouse locus with a human gene cluster region of over 200 kbp

In mice, the cytidine deaminase APOBEC3 protein is encoded by a single gene, whereas in humans, gene duplication during mammalian evolution has expanded the family to include seven tandemly arranged genes (APOBEC3A, 3B, 3C, 3D, 3F, 3G, and 3H) located on chromosome 2244. We next investigated whether our method could replace the mouse Apobec3 locus with the human APOBEC3 gene cluster spanning more than 200 kbp (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 3a–c). Similar to the c-Kit humanization strategy, when 3-kbp human homology arms were used in the first step, successful knock-in of the full human APOBEC3 gene cluster in the second step was confirmed, with efficiencies of 15.2% in BALB/c ES cells and 10.6% in C57BL/6 N ES cells45 (Fig. 3b, c, Supplementary Fig. 3d–g), demonstrating the applicability of the method across multiple mouse strains. Notably, no head-to-tail tandem insertion was detected in any of the analyzed clones (Supplementary Fig. 3h). BALB/c and C57BL/6 N ES cell lines contributed to the germline of chimeric mice, generating animals carrying the human APOBEC3 gene cluster (Fig. 3d, e, Supplementary Fig. 3i). In humans, APOBEC3 genes are highly expressed in the lung and spleen but show low expression in skeletal muscle and the cerebrum42. Consistently, RNA-seq analysis of the lungs and spleens from Apobec3-humanized mice revealed the expression of all seven human APOBEC3 genes (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 3j, k). Notably, the expression profiles in the lungs of humanized mice correlated significantly with those in human lungs46 (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Fig. 3l). Quantitative PCR further confirmed high expression of APOBEC3 genes in the spleen and lungs and low expression in skeletal muscle and the cerebrum, similar to the organ-specific expression patterns observed in humans (Fig. 3h, i). In mice, the Apobec3 locus is flanked by Cbx6 and Cbx7 (Supplementary Fig. 3m). While Cbx7 expression was unaffected in the lungs and spleens of humanized mice, Cbx6 expression was reduced in the lungs (Fig. 3j), suggesting that large-scale genomic humanization can potentially influence neighboring gene expression. Finally, protein analysis of humanized mouse leukocytes revealed expression of APOBEC3B, 3C, 3F, 3G, and 3H proteins, but not APOBEC3A (Fig. 3k). Collectively, these results demonstrate that our method enables FL-GH of genomic regions exceeding 200 kbp and can accurately replicate major aspects of human gene expression profiles in vivo.

a Schematic illustration of FL-GH of the mouse Apobec3 locus. b Knock-in efficiency of human APOBEC3 gene cluster calculated from the genotyping PCR results of blasticidin-resistant ES cell colonies that appeared after the second step. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments using BALB/c or C57BL/6 N ES cells with or without NeoR-RNP (ordinary one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). c Sequence analysis of the junction between the mouse Apobec3 locus and the human APOBEC3 gene cluster in Apobec3-humanized ES cell clones. d Representative images of mice carrying a human APOBEC3 gene cluster at 4–8 weeks of age. Both BALB/c and C57BL/6 ES cell clones contributed to the germline in chimeric mice. e FISH analysis of an ES cell clone (C57BL/6 N #1-19) obtained in the second step using a probe targeting the human APOBEC3 genomic region. The red arrowhead indicates the predicted integration site on the chromosome. Fluorescent signals were observed at a single location using a probe specific to the human APOBEC3 gene cluster. f RNA-seq analysis of lungs from Apobec3-humanized mice showing expression peaks corresponding to all seven human APOBEC3 family genes. g Correlation analysis of APOBEC3 family gene expression between humans and humanized mouse lungs (two-tailed F-test, R2 = 0.7186, P = 0.0160). Expression values were calculated as individual APOBEC3 TPM / mean TPM of all seven human APOBEC3 family genes. Human lung RNA-seq data were obtained from the GTEx Portal (n = 604)46. h qPCR analysis of all seven human APOBEC3 family gene expressions in organs of the mice carrying the human APOBEC3 gene cluster. Expression levels relative to those in the lungs of humanized mice are shown. Data are presented as means ± SD from biological triplicates (ordinary one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). i Heatmap showing tissue-specific expression patterns of APOBEC3 genes between human and humanized mice across the indicated organs. For human gene expression data, we used TPM values from the GTEx Portal (Spleen: n = 277, Lung: n = 604, Muscle: n = 818, Cerebrum: n = 270)46, and for humanized mouse gene expression, we used relative expression values obtained by qPCR (normalized to Actb). After calculating z-scores for each dataset, we visualized the expression patterns as heatmaps. j qPCR analysis of neighboring gene expressions (Cbx6 and Cbx7) flanking the Apobec3 locus in multiple organs of humanized mice. Expression levels relative to organs of wild-type mice are shown. Data are presented as means ± SD of biological triplicates (ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). k Western blot analysis for human APOBEC3 family proteins in leukocytes of humanized mice. APOBEC3D was not evaluated due to the lack of a suitable antibody. Three independent humanized mice were examined, except for APOBEC3F, which was analyzed in one mouse. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Human disease modeling in mice by introducing mutations into a humanized allele

To further evaluate the versatility of our technique, we humanized the X-linked Cybb gene (Fig. 4a). As in previous experiments, 3-kbp homology arms flanking the human CYBB (hCYBB) gene were introduced in the first step (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 4a, b), and ES cell lines harboring a full-length hCYBB gene were established with an average efficiency of 13% in the second step (Fig. 4c–e, Supplementary Fig. 4c–e). As observed in the Apobec3 humanization, no tandem insertions were detected in any of the clones analyzed (Supplementary Fig. 4f). The humanized Cybb allele was successfully transmitted through the germline (Fig. 4f). In humans, CYBB is highly expressed in pulmonary macrophages and splenic lymphocytes42. Consistent with this, the CYBB protein was coexpressed with F4/80-positive macrophages in the lungs of Cybb-humanized male mice (Fig. 4g). Furthermore, qPCR analysis revealed high expression of the hCYBB gene in the lungs and spleen but low expression in the cerebellum of Cybb-humanized males (Fig. 4h, left), recapitulating the organ-specific expression pattern reported in humans (Fig. 4i), whereas mouse Cybb expression was detected only in wild-type mice (Fig. 4h, right). The Xk and Dynlt3 genes, which flank the mouse Cybb locus (Supplementary Fig. 4g), exhibited no significant differences in expression between wild-type and humanized mice (Fig. 4j), suggesting that Cybb locus humanization minimally affects neighboring gene expression. CYBB encodes NADPH oxidase, an enzyme responsible for generating the reactive oxygen species (ROS) required for phagocytic activity in granulocytes47. Loss-of-function mutations in CYBB cause chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), a rare immunodeficiency characterized by defective ROS production in phagocytes48. To model CGD, we introduced two CGD-associated mutations (T458G and A461Δ)49 into the hCYBB allele in Cybb-humanized ES cells using additional genome editing (Fig. 4k, Supplementary Fig. 4h). Mice carrying the mutant hCYBB allele (hCYBBMut) developed normally and showed comparable growth to those carrying the wild-type human allele (hCYBBWT) up to at least 8 weeks of age (Fig. 4l). Upon phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) stimulation, which induces intracellular ROS production, granulocytes from hCYBBWT and wild-type (mCybb) mice generated comparable ROS levels, whereas those from hCYBBMut mice failed to increase ROS levels (Fig. 4m, Supplementary Fig. 4i). Overall, these results demonstrate that our method enables not only FL-GH of individual loci but also precise modeling of human genetic diseases in vivo by introducing disease-associated mutations into humanized alleles.

a Schematic illustration of FL-GH of the mouse Cybb locus. b Knock-in efficiency of hCYBB homologous arms based on genotyping PCR of G418-resistant ES cell colonies after the first step. Data are presented as means ± SD of three independent experiments (ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). c Knock-in efficiency of the hCYBB locus calculated from the genotyping PCR results of blasticidin-resistant ES cell colonies that appeared after the second step. Data are presented as means ± SD of three independent experiments under RNP (with or without) (unpaired t-test, two-tailed). d Sequence analysis of the junction between the mouse Cybb locus and the human CYBB genomic region in the Cybb-humanized ES cell clones. e FISH analysis of an ES cell clone (#2–17) obtained in the second step obtained in the second step using a probe targeting the human CYBB genomic region. The red arrowhead indicates the predicted integration site on the chromosome. Fluorescent signals were observed at a single location using a probe specific to the human CYBB gene. f Representative images of Cybb-humanized mice at 4 weeks of age. The genotypes were determined by the presence or absence of PCR bands with predicted sizes. g Immunofluorescence staining for CYBB and F4/80 in the lungs of male Cybb-humanized mice at 4 weeks of age. Images were obtained from one Cybb-humanized male mouse. Reproducibility was confirmed using three independent mice. Scale bars: 50 µm. h qPCR analysis of mouse Cybb and human CYBB expression in various organs of male Cybb-humanized mice. Data are presented as mean ± SD from biological triplicates. Expression levels are shown relative to those in the lungs of Cybb-humanized mice or wild-type mice (ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). i Heatmap showing tissue-specific expression patterns of the human CYBB gene between human and humanized mice across the indicated organs. For human gene expression data, we used TPM values from the GTEx Portal (Spleen: n = 277, Lung: n = 604, Cerebellum: n = 266, Testis: n = 414)46, and for humanized mouse gene expression, we used relative expression values obtained by qPCR (normalized to Actb). After calculating z-scores for each dataset, we visualized the expression patterns as heatmaps. j qPCR analysis of neighboring gene expressions (Xk and Dynlt3) flanking the Cybb locus in lungs of male Cybb-humanized mice. Data are presented as mean ± SD from biological triplicates. Expression levels are shown relative to those in the lungs of wild-type mice (ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, two-tailed). k Schematic illustration of the establishment of ES cell lines, of which CGD-causing mutations (T458G and A461⊿) were introduced into a humanized Cybb allele, and their establishment efficiency and sequence analysis. l Representative images of Cybb-humanized mice carrying CGD-associated mutations at 8 weeks of age. Genotypes were confirmed by the presence or absence of PCR bands with predicted sizes. m Flow cytometry histogram showing ROS production in Ly6G+ granulocytes from Cybb-humanized mice with or without CGD-associated mutations, following PMA stimulation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

Previously, BAC transgenic mice harboring full-length human genes have been reported50,51. However, this approach retains the endogenous mouse counterpart genes, making it difficult to distinguish the phenotypic contributions of mouse and human genes. In contrast, BAC knock-in-based FL-GH replaces mouse loci with their human orthologues, enabling precise analysis of human genes in vivo. In this study, we developed a versatile method, termed TECHNO, for FL-GH in mouse ES cells using two sequential CRISPR/Cas9-assisted HR steps. We successfully applied the method to multiple gene loci with insert sizes ranging from 55 kbp (CYBB) to 205 kbp (APOBEC3 cluster), achieving stable knock-in efficiency across this nearly four-fold size difference. These results demonstrate the scalability of our approach within the BAC-compatible genomic range. The first-step vectors were constructed using standard PCR-based cloning, whereas the second-step genomic inserts were derived from commercially available BACs. Our methods enabled efficient FL-GH for genomic fragments over 200 kbp with only two recombination events. Given that 93% of human genes fall within this size range, our method has broad applicability.

While a previous study has reported successful BAC knock-in using CRISPR/Cas9 in rat zygotes52, knock-in methods for genomic fragments exceeding 100 kbp have not been reported in zygote-based genome editing in mice. This raises the possibility that species-specific differences may influence the efficiency or feasibility of ultra-large fragment integration via zygote-based methods. In addition, ES cell-based targeting allows in vitro screening, enabling the recovery of a defined number of knock-in clones in a single trial.

Conventional HR techniques using ES cells have shown poor efficiency for large-fragment knock-in (e.g., ~0.2% for >200 kbp)24. In contrast, we achieved knock-in efficiencies of 10.6% and 15.2% for the >200 kbp APOBEC3 cluster in C57BL/6 N and BALB/c ES cells, respectively, representing a > 50-fold improvement. In addition, we consistently achieved >10% efficiency across all tested loci (Table 1), reflecting the simplicity and robustness of the approach. The first step builds on our previously reported high-efficiency knock-in system30, while the second step uses a universal gRNA with validated cleavage activity, ensuring reliable outcomes. These results suggest that with sufficient homology arms and efficient double-strand breaks, the endogenous recombination machinery in ES cells can support the integration of very large DNA fragments. As even longer genomic libraries become available in the future, our method could be extended beyond the current BAC capacity.

Another possible approach for FL-GH in ES cells is to use BAC vectors equipped with mouse homologous arms for a one-step genome editing process based on E. coli–mediated BAC recombination. We attempted such a one-step FL-GH targeting the hKIT locus using a BAC carrying mouse homology arms; however, no FL-GH ES cell clones were obtained, suggesting that simultaneous recombination involving both large deletions within the genomic region and large insertions of exogenous DNA fragments in ES cells is less efficient and stable compared with our TECHNO method (Supplementary Fig. 5a). It is also notable that the efficiency of genome editing in ES cells may vary depending on the target locus and gRNA cleavage activity (Supplementary Fig. 5b). In contrast, since our two-step approach uses universal gRNAs for the large-size knock-in at the second step, it consistently achieves stable FL-GH efficiencies across multiple loci, highlighting its versatility and robustness. In addition, unlike earlier FL-GH studies that relied on F1 hybrid ES cells due to their greater tolerance for extended culture, which often impairs the chimera-forming ability of commonly used inbred ES cell lines, our streamlined strategy enabled rapid selection of correctly targeted clones and supported germline transmission, even in inbred strains like BALB/c and C57BL/6. This eliminates the need for prolonged backcrossing and accelerates the generation of genetically matched humanized models.

To avoid loss of genes essential for ES cell maintenance or development, we selected heterozygous knock-in clones after the first step and used them for the second step. Importantly, functional complementation between mouse and human orthologs is known to be gene-dependent. Thus, if a gene is so critical that even its heterozygous disruption impairs ES cell survival or organismal development, and the human KI gene cannot fully compensate for the loss of mouse gene function, additional strategies may be required. Notably, our analysis of the non-knock-in allele in Apobec3-humanized ES cell lines revealed that, among six clones without large deletions, four harbored small indels within the gRNA recognition sequence (Supplementary Fig. 5c). These findings indicate that even in the absence of large deletions, small mutations are frequently introduced into the non-knock-in allele during Cas9-mediated editing. Accordingly, when designing gRNAs for the first step, it is advisable to target genomic regions that are located sufficiently distant from known genes and promoter elements, and preferably reside within non-annotated regions in public databases, to minimize the risk of disrupting gene regulatory functions.

Although technical constraints exist, previous studies have reported humanized mouse models generated using short human cDNAs. For example, transgenic models expressing human ACE2 cDNA have been widely used for MERS or SARS-CoV research53,54. However, these models lacked native regulatory elements, resulting in the expression patterns of a transgene that differed from those in humans. They also expressed only a single isoform while retaining endogenous mouse gene expression. In contrast, our c-Kit-humanized mice, with full replacement of the mouse locus, faithfully recapitulated human alternative splicing and organ-specific gene expression. Similarly, a previous attempt to introduce a human CYBB cDNA minigene into the mouse locus failed to yield protein expression49,55, while our Cybb FL-GH allele, which retained human introns, produced functional CYBB protein, underscoring the regulatory importance of noncoding regions. Nonetheless, APOBEC3A expression was significantly reduced in humanized mice relative to humans, and no protein was detected in leukocytes. Given that mice possess only a single Apobec3 gene, this discrepancy likely reflects interspecies differences in transcriptional regulation. Future studies should investigate species-specific regulatory mechanisms that govern the expression of orthologous genes. In addition, a reduction in Cbx6 mRNA expression was observed in the lungs of homozygous APOBEC3-humanized mice. This suggests that deleted Apobec3 regions may contain unidentified regulatory elements—such as organ-specific distal enhancers— required for proper regulation of Cbx6 expression.

It should be noted that we designed the KI constructs to include approximately 5–30 kbp of sequence upstream and downstream of the entire gene, including proximal regulatory regions such as the promoter (Supplementary Figs. 1d, 2c, 3c, 4c). However, our method may not fully cover distal regulatory regions such as enhancers. Since transcriptional regulation, splicing, and translation are influenced by numerous factors—such as transcription factors and RNA-binding proteins—that are species-specific, the expression dynamics and functionality of each humanized gene in mice should be carefully analyzed and compared with those in humans on a gene-by-gene basis.

Finally, the FL-GH of the hCYBBMut mouse recapitulated key features of human CGD in vivo without requiring human cells. In the future, combining FL-GH technology with genome editing, particularly in vivo base editing56 or prime editing57, could allow for the precise introduction of disease-relevant human mutations into humanized gene loci within living mice. This would enable direct investigation of disease mechanisms such as cancer or immune disorders under physiologically relevant conditions. Moreover, BAC libraries are already available not only for humans but also for domestic animals such as cattle and pigs. Thus, our approach may also be applied to rapidly evaluate valuable genetic traits in livestock using small animal models.

Another potential application of FL-GH mice is to analyze protein-protein relations, such as ligand-receptor interactions, in vivo by developing multi-locus humanization mice. As shown in Fig. 2, the testes of homozygous c-Kit-humanized mice were significantly smaller than those of the control mice, although these mice were still able to produce fertile sperm. c-KIT is a receptor tyrosine kinase that forms dimers upon ligand binding and activates downstream signal pathways. This phenotype suggests that testicular regression in homozygous humanized mice may be due to suboptimal compatibility between the mouse ligand and the human receptor. By humanizing corresponding mouse ligands using our method and analyzing the resulting phenotypic changes, it would be possible to assess human gene functionality in vivo and gain insights into the evolutionary conservation of ligand-receptor interactions between mice and humans. Collectively, our FL-GH platform enables the efficient generation of physiologically relevant humanized models with wide-ranging applications in gene regulation, disease modeling, and translational research.

Methods

Targeting vector (for the first step)

To prepare the insert, mouse 5′ and 3′ homologous arms with 15 bp extensions complementary to the backbone ends (1000 + 30 bp, respectively) were amplified using KOD-FX-Neo (TOYOBO) with C57BL/6 J or BALB/c wild-type mouse genome as a template. The backbone (2626 bp) was obtained using a pUC vector (AZENTA) as a template. The insert and backbone were combined using an In-Fusion HD Cloning Kit (TaKaRa). Then, for insert preparation, human 5′ and 3′ homologous arms with 15-bp extensions complementary to the backbone ends (1000 + 30 or 3000 + 30 bp, respectively) were amplified with BAC as a template. The backbone (4626 bp) was obtained using a pUC vector into which mouse genomic regions were cloned as a template, as described above. The insert and backbone were combined by the In-Fusion reaction. Lastly, a fragment of EF1a-NeoR-pA with 15 bp extensions complementary to the backbone ends (3219 + 30 bp) was amplified as an insert. The backbone (6626 or 10626 bp) was obtained by PCR amplification using the pUC vector into which the mouse and human genomic regions were cloned. The insert and backbone were combined by the In-Fusion reaction. The genomic regions cloned into each vector are as follows: Gt(ROSA)26Sor upstream: Chr6 (NC_000072.7) 113052998-113053997, Gt(ROSA)26Sor downstream: Chr6 (NC_000072.7) 1113051998-113052997, mouse c-Kit upstream: Chr5 (NC_000071.7) 75728713-75729712, mouse c-Kit downstream: Chr5 (NC_000071.7) 75819206-75820205, human c-KIT upstream: Chr4 (NC_000004.12) 54652015-54653014 (for 1 kbp arm), human c-KIT upstream: Chr4 (NC_000004.12) 54650015-54653014 (for 3k bp arm), human c-KIT downstream: Chr4 (NC_000004.12) 54743558-54744557 (for 1 kbp arm), human c-KIT downstream: Chr4 (NC_000004.12) 54743558-54746557 (for 3 kbp arm), mouse Cybb upstream: ChrX (NC_000086.8) 9343739-9344738, mouse Cybb downstream: ChrX (NC_000086.8) 9292498-9293497, human CYBB upstream: ChrX (NC_000023.11) 37770807-37773806, human CYBB upstream: ChrX (NC_000023.11) 37818821-37821820, mouse Apobec3 upstream: Chr15 (NC_000081.7) 79765736-79766740, mouse Apobec3 downstream: Chr15 (NC_000081.7) 79797039-79798029, human APOBEC3 upstream: Chr22 (NC_000022.11) 38927609-38930608, human APOBEC3 upstream: Chr22 (NC_000022.11) 39125837-39128836. Genome sequence information was obtained from Ensembl genome browser 113, and GRCm39 (GCF_000001635.27) and GRCh38.p14 (GCF_000001405.40) was used as a reference genome, respectively. The targeting vectors were purified using NucleoBond Xtra Midi EF (TaKaRa) and dissolved in TE at 1 µg µL−1.

BAC (for the second step)

A fragment of rox-PGK-Bsd-pA-rox-Ef1-copGFP-T2A-PuroR-pA (PGK-Bsd cassette) flanked by insulator sequences with 50 bp homologous arms (3623 + 100 bp) was amplified using KOD-FX-Neo. This fragment was inserted downstream of the 3′UTR gene region contained in the BACs (BACPAC Resources) by the Red-ET BAC-recombination system58 (GeneBridges). The clone numbers of the BACs used for gene humanization are as follows: c-KIT: RP11-1122L13, CYBB: RP11-641C23, and APOBEC3: RP11-1033I2. The recombinant BACs were purified using NucleoBond Xtra BAC (TaKaRa) and dissolved in TE at 1 µg µL−1.

Defining the length of the human gene and determining the extent of the humanized region

Ensembl Human (GRCm38.p14) was used as the reference genome, and gene size was defined as the distance from the transcription start site (TSS) of the most upstream exon to the 3’ end of the most downstream exon among the reported splicing isoforms for each gene. To determine the extent of regulatory regions to be included in the KI, we surveyed 21570 human genes and identified approximately 16559 genes with annotated promoter regions. The distance between the TSS and the annotated 5’ end of the promoter regions ranged from a maximum of 2773 bp to an average of 486 bp. Based on the analysis, we designed the KI constructs to include approximately 5–30 kbp of sequence upstream and downstream of each gene.

Preparation of the CRISPR-Cas9 RNP complex

TracrRNA and crRNA (IDT, 200 µM each) were dissolved in Duplex Buffer (IDT) and annealed in a thermal cycler at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by −1 °C min−1 stepdown cycles until 25 °C. Annealed gRNA (100 µM) was then incubated with 3 µg µL−1 of Alt-R S.p. Cas9 Nuclease V3 (IDT) at 37 °C for 20 min to form Cas9-RNP. An electroporation enhancer (IDT, 108 µM) was dissolved in RNase-free water. The cleavage efficiency of each Cas9-RNP used in the first and second steps in the target genomic region is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5 (for the first step) and Supplementary Fig. 1e (for the second step), respectively. The gRNAs used in this study were chosen to have a high MIT specificity score and CFD spec. score in CRISPOR59.

Cell culture

Mouse ES cells were cultured in an ES cell medium comprising Knockout DMEM (Gibco), 1 × GlutaMAX-Ⅰ (Gibco), 1 × MEM NEAA (Gibco), 100 U mL−1 penicillin (Wako), 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin (Wako), 15% FBS (Gibco), 0.1 mM mercaptoethanol (Nacalai Tesque), 1000 U mL−1 human LIF (Wako), 0.2 μM PD0325901 (Stemgent) and 3 μM CHIR99021 (Stemgent) on MEFs irradiated with X-ray.

Establishment of ES cells

ES cell lines carrying human homologous arms (first step)

V6.5 (C57BL/6 × 129SvJae) ES cell line was established in the laboratory of Dr. Rudolf Jaenisch and provided to Dr. Yasuhiro Yamada. C57BL6N (JM8A3) ES cell line was obtained from EuMMCR. The BALB/c ES cell line was established in our laboratory. The V6.5 ES cell line (C57BL/6 × 129SvJae) was used to humanize Rosa26, c-Kit and Cybb genes, and the BALB/c and JM8 (C57BL/6N) ES cell lines were used to humanize the Apobec3 gene. ES cell lines carrying human homologous arms were generated according to a previously described protocol30. Briefly, 1 μL of a circular targeting vector (1 μg) for the first step and a total of 1 μL of Cas9-RNPs (up/down) together with 2 µL of electroporation enhancer was electroporated into 1 × 105 ES cells using the Neon NxT Electroporation System 10 µL Kit (Invitrogen). When 1 × 106 ES cells were used, the total volume was scaled up 10-fold and the Neon Nxt Electroporation System 100 µL Kit (Invitrogen) (at a final concentration of 10 µM annealed RNA, 0.3 µg µL−1 Cas9 protein and 21.6 µM electroporation enhancer). The number of ES cells used for genome editing at each locus was as follows: Rosa26: 1.0 × 105 cells, c-Kit: 1.0 × 105 or 106 cells, Apobec3: 1.0 × 106 cells, Cybb: 1.0 × 106 cells. Electroporation was performed under the conditions of two pulses at 1200 V and 20 ms. The sequences of the gRNA are as follows: Rosa26: CGCCCATCTTCTAGAAAGAC, c-Kit upstream: TGGTCCTTGCCACGCCCACG, c-Kit downstream: ATGTAACTATGTGTTTTTGA, Cybb upstream: GCCAGATATCATTACAGCGT, Cybb downstream: ATACTCGTTTTGTGACTAAA, Apobec3 upstream: GTTAGCATCAGGGTCCTAGC, Apobec3 downstream: CCCATCCACTCAGAACCCGT. After selection with 350 μg mL−1 G418 (Nacalai Tesque) for 7 days, G418-resistant ES cell colonies were picked and expanded to establish ES cell lines.

ES cell lines carrying full-length human gene (second step)

Thirty microliters of the BACs inserted PGK-Bsd cassette (30 μg) and a total of 10 µL of NeoR-RNPs (up/down) together with 40 µL electroporation enhancer in Opti-MEM (Gibco) (Total volume: 200 µL) were introduced into 1.0 × 107 ES cell lines carrying human homologous arms using a NEPA21 TypeⅡ (NEPAGENE) and NEPA Electroporation Cuvettes 2 mm Gap (NEPAGENE) (at a final concentration of 5 µM annealed RNA, 0.15 µg µl−1 Cas9 protein and 21.6 µM electroporation enhancer). Electroporation protocols are as follows (voltage [V], pulse length [msec], pulse interval [msec], pulses, decay rate [%], polarity): poring pulse; 110, 5.0, 50.0, 2, 10, + and transfer pulse; 20, 50.0, 50.0, 5, 40, +/−. The sequences of the gRNA are as follows: NeoR upstream: TTATTAATAGTAATCAATTA, NeoR downstream: AGGCCAAAAACTGAGTCCTT. After selection with 10 μg mL−1 blasticidin S (Gibco), blasticidin-resistant ES cell colonies were picked and expanded to establish ES cell lines.

Establishment of hCYBB mutant ES cells

One point five micrograms of a Megamer ssGene Fragment of the CYBB exon5 sequence (401 bp) carrying T458G and A461⊿ mutations (IDT) and total 1 μL of Cas9-RNPs (up/down) targeting human CYBB exon5 together with 2 µL of electroporation enhancer was electroporated into 1 × 105 ES cell lines carrying the Cybb-humanized allele using Neon NxT Electroporation System 10 µl Kit (at final concentration of 10 µM annealed RNA, 0.3 µg µl−1 Cas9 protein and 21.6 µM electroporation enhancer). Electroporation was performed under the conditions of two pulses at 1200 V and 20 ms. The sequences of the gRNA are as follows: CYBB exon5 upstream: CACTCTCTGAACTTGGAGAC, CYBB exon5 downstream: TATCTAAGTCAGATAATGAG. After electroporation, the ES cells were passed once and then picked and expanded to establish ES cell lines.

Genomic DNA extraction and PCR genotyping

ES cells for genotyping PCR were cultured in feeder-cell-free conditions. For the in vivo samples, freshly collected tissues were incubated in Tail Lysis Buffer (Nacalai Tesque) at 65 °C for 2 h or more. Genomic DNA was purified by a standard phenol-chloroform nucleotide extraction procedure followed by ethanol precipitation and dissolved in TE. Genomic DNA was quantified on a NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and diluted to a concentration of 50 ng μL−1. One microliter of genomic DNA was used for PCR analysis with KOD-FX-Neo and GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega).

Copy number analysis

Quantitative real-time PCR for copy number analysis was performed using 50 ng of ES cell genomic DNA and primers targeting the BAC-contained blasticidin resistance cassette (PGK-Bsd). GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega) and CXR Reference Dye (Promega) were used for PCR, which was performed on a StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Supplementary Table S1 lists the primers used. Relative copy numbers were normalized against the corresponding level of Actb. A mouse genomic DNA homozygous for the locus into which the PGK-Bsd was introduced was used as a positive control, and a wild-type mouse genomic DNA was used as a negative control. The experiments were performed in biological triplicate.

FISH analysis

Cells were washed with PBS and incubated in 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Nacalai Tesque) for 5 min at 37 °C. After centrifuging at 200 g for 3 min, the cell pellet was hypotonically treated with 1.5 mL of 0.075 M KCl solution for 20 min at room temperature (RT). A 1.5 mL fixative solution (methanol: acetic acid = 3:1) was added and incubated at 4 °C for 5 min. Post-treatment with 10 mL of fixative solution, the sample underwent centrifugation at 200 g for 3 min at 4 °C. After the sample suspension, an additional 10 mL of fixative solution was added and recentrifuged. The sample was resuspended, and a single drop was placed on a glass slide with a Pasteur pipette. The slide was dried at 37 °C overnight for cell preparation. Dried slides were incubated at 70 °C for 2 h on a hot plate, covered with coverslips, and hybridized with Cy3-labeled probes (prepared from the humanization BAC template; Chromosome Science Labo) after co-denaturation at 70 °C for 5 min. Following overnight hybridization at 37 °C, slides were soaked in 2 × SSC (5 min) to remove coverslips, washed stringently in formamide/4 × SSC (1:1, 37 °C, 20 min), rinsed in 1 × SSC (15 min), counterstained with DAPI, and imaged using a BZ-X710 microscope (KEYENCE).

Immunocytochemistry

Cultured cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at RT and treated with blocking buffer (PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 [Sigma] and 3% BSA [Wako]) at RT for 30 min. Cells were stained overnight at 4 °C with rabbit monoclonal anti-mouse c-KIT (Abcam, #ab273119, dilution 1/200) or rabbit monoclonal anti-human c-KIT (Abcam, #ab283653, dilution 1/200). The next day, cells were stained in blocking buffer at RT for 1.5 h with secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor488 (Invitrogen, #A-21206, dilution 1/500), Alexa Fluor555 (Abcam, #ab150062, dilution 1/500) and DAPI (Invitrogen, #D21490, dilution 1/750). Immunofluorescence signals were detected using a BZ-X710 fluorescence microscope.

Generation of chimeric mice

Eight-week-old ICR or C57BL/6 J female mice (Japan SLC) received 7.5 U of equine chorionic gonadotrophin (eCG) (Serotropin: ASKA Animal Health) by intraperitoneal injection. Additionally, 48 h after serotropin treatment, mice were injected with 7.5 U of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (Gonatropin: ASKA Pharmaceutical) and then mated with male mice (Japan SLC). Two-cell fertilized eggs were collected and maintained in CARD-KSOM medium (KYUDO) to obtain blastocysts. After the injection of six to ten ESCs, the injected blastocysts (22–26 blastocysts/mouse) were transplanted into the uterus of pseudopregnant ICR female mice (Japan SLC).

IVF

Superovulation of female C57BL/6 J mice was carried out in the same manner described above. The oocytes were retrieved from the oviduct 17 h after hCG injection and incubated in CARD-mHTF medium (KYUDO) until use. IVF was performed with the CASE3 method (KYUDO), as described in the instruction manual. Fresh cauda epididymal sperm were dispersed in a drop of CARD medium (KYUDO) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The entire amount of sperm collected from one mouse was added to the drop containing the oocytes. The oocytes were collected 4 h after IVF and cultured in mHTF medium at 37 °C under 5% CO2 in air. The next day, the number of 2-cell stage embryos was counted, followed by their transfer into the oviducts of pseudopregnant ICR female mice.

Histological analysis, immunostaining, and immunofluorescence

Dissected tissue samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, Nacalai Tesque) overnight at RT. The fixed samples were embedded in paraffin using HistoCore PEARL (Leica Biosystems). Sections were sliced to a thickness of 3–4 μm. The samples were soaked three times for 5 min each in Lemosol (Wako) to remove paraffin, and three times for 5 min each in 100% ethanol to hydrophilize. After water washing for several minutes, the samples were boiled in Tris-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.05% [v/v] Tween 20 prepared in water; pH 9.0) via autoclaving (110 °C, 20 min) to reactivate the antigens. The samples were then soaked in PBS for several minutes and incubated with 200 μL of primary antibodies in PBS with 2% BSA (MP Biomedicals) at 4 °C overnight. The primary antibody used was rabbit monoclonal anti-human c-KIT (Abcam, #ab283653, dilution 1/200). Sections were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Nichirei Bioscience, Histofine) at RT for 30 min, and chromogen development was performed using DAB (Nichirei Bioscience). The stained slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. The sections were mounted and visualized with a DP28 microscope (Evident Scientific). For immunofluorescence, the primary antibodies used were rabbit monoclonal anti-human c-KIT (Abcam, #ab283653, dilution 1/400), mouse monoclonal anti-F4/80 (Santa Cruz, #sc-377009, dilution 1/200), mouse monoclonal anti-PLZF (Santa Cruz, #sc-28319 dilution 1/200), goat polyclonal anti-SCP-3 (Santa Cruz, #sc-20845, dilution 1/200), mouse monoclonal anti-CYBB (Abcam, #ab80897, dilution 1/1000), and rabbit monoclonal anti-F4/80 (CST, #70076, dilution 1/500). Sections were stained for 30 min at RT in PBS comprising 2% BSA with secondary antibody conjugated with fluorescent protein: Alexa Fluor488 anti-goat IgG (Abcam, #ab150129, dilution 1/500), Alexa Fluor488 anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, #A-21206, dilution 1/500), Alexa Fluor488 anti-mouse IgG (Abcam, #ab150109, dilution 1/500), Alexa Fluor555 anti-rabbit IgG (Abcam, #ab150062, dilution 1/500), Alexa Fluor555 anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, #A-31570 dilution 1/500), and Alexa Fluor647 anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, #A-31571, dilution 1/500). After two more 5-min washes in PBS, the sections were mounted using ProLong Glass Antifade Mountant with NucBlue Stain (Invitrogen) and visualized with a BZ-X710 fluorescence microscope (KEYENCE).

Western blotting

Human APOBEC3 family proteins were detected by western blot in mouse peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) lysates using established methods60,61,62. PBMCs were harvested from the spleens of 4-week-old mice, washed twice with PBS, and lysed in 2 × SDS sample buffer [100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 4% SDS, 12% β-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol, 0.05% bromophenol blue]. The lysates were boiled at 95 °C for 10 min, and the proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE before being transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, #IPVH00010). Membranes were blocked with 4% skim milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20, followed by incubation with primary antibodies in blocking buffer: rabbit monoclonal anti-A3A/A3B63 (CST, #5210-87-13, dilution 1:1000), rabbit polyclonal anti-A3C (Proteintech, #10591-1-AP, dilution 1:1000), rabbit polyclonal anti-A3F64 (Covance, #675, dilution 1:1000), rabbit anti-A3G (NARP, #10201, dilution 1:2500), rabbit polyclonal anti-A3H (NOVUS, #NBP1-91682, 1:5000), rat monoclonal anti-GAPDH conjugated with HRP (BioLegend, #607903, dilution 1:100000). Subsequently, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies: donkey anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch, #711-035-152, dilution 1:5000). For HRP detection, SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #34095) or SuperSignal Atto (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A38555) was used. Bands were visualized using the Amersham Imager 600 (Amersham).

Hematologic examination

Peripheral blood was obtained from the buccal veins of mice. Hematological parameters were determined using Celltac α MEH-6558 (Nihon Kohden).

Stimulation of ROS production and flow cytometric analysis in blood cells

Whole blood was collected from the femoral veins of mice. To remove red blood cells, the whole blood was treated with 20 times the volume of ACK Lysing Buffer (Gibco) on ice for 15 min. After centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min, the supernatant was removed, and 15 mL of ACK Lysing Buffer was added and treated for 5 min. Intracellular ROS was detected using a Cell Meter Intracellular Fluorimetric Hydrogen Peroxide Assay Kit Blue Fluorescence Optimized for Flow Cytometry (ABD). The cell pellets were suspended with 500 μl of DMEM/F-12 medium (Gibco) containing 1 μL of OxiVision Blue Peroxide Sensor stock solution and stained at 37 °C for 30 min. Post-centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min, the cell pellets were suspended with 200 nM Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) PKC activator (Abcam) in DMEM/F-12 medium and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. After centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min, the cell pellets were suspended with FACS buffer (PBS containing 4% BSA) supplemented with an anti-Ly6G antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor647 (BioLegend, #127609, dilution 1/1000) at 4 °C for 20 min. After centrifuging at 500 g for 5 min, cell pellets were resuspended in FACS buffer and passed through a cell strainer. The cells were analyzed by CytoFLEX S (Beckman Colter). The FACS data were analyzed using FLOWJO V10 (BD).

RNA preparation

For the in vitro samples, RNA was isolated by NucleoSpin RNA plus (TaKaRa). For the in vivo samples, freshly collected tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground into powder using a mortar. RNA was isolated from spleens, lungs, skeletal muscles, and testes using a RNeasy Fibrous Tissue Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and from cerebrums and cerebellums using a RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (QIAGEN). For mRNA-seq in spermatogonia, testes were collected from 2-week-old mice, and the tunica albuginea was removed. The testes were then transferred to 200 μL of collagenase Ⅳ solution (1.5 mg mL−1 in DMEM/F-12 medium) and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. Post-centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min, the samples were transferred to 250 μL of 0.25% trypsin-EDTA, and 25 μL of DNaseⅠ solution (5 mg mL−1) were added and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. Next, 50 μL of FBS and 25 μL of DNaseⅠ solution were added and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. After pipetting, the cells were passed through a 0.44 μm cell strainer and washed with MACS buffer (0.5 M EDTA and BSA in PBS). MACS was performed according to the instructions of CD117 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, #130-097-146). Briefly, cell pellets were resuspended in 80 μL of MACS buffer per 1 × 107 cells total cells, and 20 μL of CD117 MicroBeads were added and incubated at 4 °C for 15 min. The cells were washed with MACS buffer and then applied to a rinsed MS column placed in the magnetic field of a MACS Separator. After washing the column three times with MACS buffer, the magnetically labeled cells were flushed out. RNA was isolated by NucleoSpin RNA plus (TaKaRa) and quantified on a NanoDrop 2000.

cDNA synthesis and qPCR analysis

Five hundred nanograms of RNA were reverse transcribed into cDNA using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed using the GoTaq qPCR Master Mix and CXR Reference Dye on a StepOnePlus real-time PCR system. Supplementary Table S1 lists the primers used. Transcript levels were normalized against the corresponding level of Actb. The experiments were performed in biological triplicate.

Library preparation for RNA sequencing

For mRNA-seq in spermatogonia of c-Kit-humanized mice, libraries were generated using a Hieff NGS Ultima Dual-mode mRNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (Yeasen) and subjected to paired-end sequencing (150 bp) with NovaSeq X plus (Illumina). For total RNA-seq in Apobec3-humanized BALB/c mice, libraries were generated using an Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep with Ribo-Zero Plus (NEB) and subjected to paired-end sequencing (100 bp) with NovaSeq X Plus (Illumina).

RNA-seq data analyses

For the mapping pattern analysis, the genomic regions spanning certain positions were extracted from the GRCh38.p14 reference genome to build an index with HISAT2 (version 2.2.1)65. The following genome sequences were used: 54650015 to 54746557 on chromosome 4 for the c-KIT gene, and 38,927,609 to 39,128,836 on chromosome 22 for the APOBEC3 gene cluster. Paired-end RNA sequencing reads were mapped to this index using HISAT2. The resulting SAM alignment files were converted into sorted BAM files using SAMtools (version 1.21)66, and mapping patterns were visualized using an Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV)67. For gene expression analysis of individual APOBEC3 family genes, a genome-wide index was generated from the GRCh38.p14 reference genome using HISAT2. Paired-end RNA sequencing reads were mapped to this index using HISAT2. The resulting SAM alignment files were converted into sorted BAM files using SAMtools. The gene-level read counts were quantified using featureCounts (version 2.0.8)68, and the expression levels were normalized to Transcripts Per Million (TPM).

Statistics and reproducibility

All statistical parameters, including statistical comparison test and exact P-value, are described in the figure or figure legends. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 10 software (GraphPad). Data are presented as mean ± SD. The reproducibility of representative images was confirmed in a minimum of three biologically independent samples (Figs. 1h, m, 2n, o, 3k, 4g, Supplementary Fig. 2g), except Fig. 2j and Supplementary Fig. 2f, h (using two independent animals). No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Mice and ethics

All animal procedures were approved by the IMSUT Animal Experiment Committee and followed institutional animal care guidelines (approval number: A2024IMS013). All mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free animal facility under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle with food and water ad libitum.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The Gene Expression Omnibus accession number for the RNA-seq data reported in this paper is GSE294590. All relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files or from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Mouse Genome Sequencing, C. et al. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 420, 520–562 (2002).

Breschi, A., Gingeras, T. R. & Guigo, R. Comparative transcriptomics in human and mouse. Nat. Rev. Genet 18, 425–440 (2017).

Cardoso-Moreira, M. et al. Developmental gene expression differences between humans and mammalian models. Cell Rep. 33, 108308 (2020).

Deveson, I. W. et al. Universal alternative splicing of noncoding exons. Cell Syst. 6, 245–255 e245 (2018).

Pishesha, N. et al. Transcriptional divergence and conservation of human and mouse erythropoiesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 4103–4108 (2014).

Schroder, K. et al. Conservation and divergence in Toll-like receptor 4-regulated gene expression in primary human versus mouse macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E944–E953 (2012).

Seok, J. et al. Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 3507–3512 (2013).

Devoy, A., Bunton-Stasyshyn, R. K., Tybulewicz, V. L., Smith, A. J. & Fisher, E. M. Genomically humanized mice: technologies and promises. Nat. Rev. Genet 13, 14–20 (2011).

Bradley, A., Evans, M., Kaufman, M. H. & Robertson, E. Formation of germ-line chimaeras from embryo-derived teratocarcinoma cell lines. Nature 309, 255–256 (1984).

Evans, M. J. & Kaufman, M. H. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature 292, 154–156 (1981).

Thomas, K. R. & Capecchi, M. R. Site-directed mutagenesis by gene targeting in mouse embryo-derived stem cells. Cell 51, 503–512 (1987).

Enard, W. et al. A humanized version of Foxp2 affects cortico-basal ganglia circuits in mice. Cell 137, 961–971 (2009).

Raffai, R. L., Dong, L. M., Farese, R. V. Jr. & Weisgraber, K. H. Introduction of human apolipoprotein E4 “domain interaction” into mouse apolipoprotein E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 11587–11591 (2001).

Saito, T. et al. Single App knock-in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 661–663 (2014).

Kostenuik, P. J. et al. Denosumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody to RANKL, inhibits bone resorption and increases BMD in knock-in mice that express chimeric (murine/human) RANKL. J. Bone Min. Res 24, 182–195 (2009).

Levine, M. S. et al. Enhanced sensitivity to N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor activation in transgenic and knockin mouse models of Huntington’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res 58, 515–532 (1999).

Menalled, L. B., Sison, J. D., Dragatsis, I., Zeitlin, S. & Chesselet, M. F. Time course of early motor and neuropathological anomalies in a knock-in mouse model of Huntington’s disease with 140 CAG repeats. J. Comp. Neurol. 465, 11–26 (2003).

van den Broek, W. J. et al. Somatic expansion behaviour of the (CTG)n repeat in myotonic dystrophy knock-in mice is differentially affected by Msh3 and Msh6 mismatch-repair proteins. Hum. Mol. Genet 11, 191–198 (2002).

White, J. K. et al. Huntingtin is required for neurogenesis and is not impaired by the Huntington’s disease CAG expansion. Nat. Genet 17, 404–410 (1997).

Luo, J. L. et al. Knock-in mice with a chimeric human/murine p53 gene develop normally and show wild-type p53 responses to DNA-damaging agents: a new biomedical research tool. Oncogene 20, 320–328 (2001).

Song, H., Hollstein, M. & Xu, Y. p53 gain-of-function cancer mutants induce genetic instability by inactivating ATM. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 573–580 (2007).

Zhu, F., Nair, R. R., Fisher, E. M. C. & Cunningham, T. J. Humanising the mouse genome piece by piece. Nat. Commun. 10, 1845 (2019).

Herndler-Brandstetter, D. et al. Humanized mouse model supports development, function, and tissue residency of human natural killer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E9626–E9634 (2017).

Macdonald, L. E. et al. Precise and in situ genetic humanization of 6 Mb of mouse immunoglobulin genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 5147–5152 (2014).

Rathinam, C. et al. Efficient differentiation and function of human macrophages in humanized CSF-1 mice. Blood 118, 3119–3128 (2011).

Valenzuela, D. M. et al. High-throughput engineering of the mouse genome coupled with high-resolution expression analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 652–659 (2003).

Willinger, T. et al. Human IL-3/GM-CSF knock-in mice support human alveolar macrophage development and human immune responses in the lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 2390–2395 (2011).

Wang, B. et al. Highly efficient CRISPR/HDR-mediated knock-in for mouse embryonic stem cells and zygotes. Biotechniques 59, 206–208 (2015).

Zhang, L. et al. Large genomic fragment deletions and insertions in mouse using CRISPR/Cas9. PLoS ONE 10, e0120396 (2015).

Ozawa, M. et al. Efficient simultaneous double DNA knock-in in murine embryonic stem cells by CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein-mediated circular plasmid targeting for generating gene-manipulated mice. Sci. Rep. 12, 21558 (2022).

Baker, O. et al. The contribution of homology arms to nuclease-assisted genome engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 8105–8115 (2017).

Devoy, A. et al. Generation and analysis of innovative genomically humanized knockin SOD1, TARDBP (TDP-43), and FUS mouse models. iScience 24, 103463 (2021).

Zhang, W. et al. Mouse genome rewriting and tailoring of three important disease loci. Nature 623, 423–431 (2023).

Hasegawa, M. et al. Quantitative prediction of human pregnane X receptor and cytochrome P450 3A4 mediated drug-drug interaction in a novel multiple humanized mouse line. Mol. Pharm. 80, 518–528 (2011).

Wallace, H. A. et al. Manipulating the mouse genome to engineer precise functional syntenic replacements with human sequence. Cell 128, 197–209 (2007).

Lee, E. C. et al. Complete humanization of the mouse immunoglobulin loci enables efficient therapeutic antibody discovery. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 356–363 (2014).

Shizuya, H. et al. Cloning and stable maintenance of 300-kilobase-pair fragments of human DNA in Escherichia coli using an F-factor-based vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 8794–8797 (1992).

Jakobovits, A. et al. Germ-line transmission and expression of a human-derived yeast artificial chromosome. Nature 362, 255–258 (1993).

Mendez, M. J. et al. Functional transplant of megabase human immunoglobulin loci recapitulates human antibody response in mice. Nat. Genet. 15, 146–156 (1997).

Russell, E. S. Hereditary anemias of the mouse: a review for geneticists. Adv. Genet. 20, 357–459 (1979).

Guo, J. et al. Chromatin and single-cell RNA-seq profiling reveal dynamic signaling and metabolic transitions during human spermatogonial stem cell development. Cell Stem Cell 21, 533–546 e536 (2017).

Uhlen, M. et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347, 1260419 (2015).

Mintz, B. & Russell, E. S. Gene-induced embryological modifications of primordial germ cells in the mouse. J. Exp. Zool. 134, 207–237 (1957).

Salter, J. D., Bennett, R. P. & Smith, H. C. The APOBEC protein family: united by structure, divergent in function. Trends Biochem Sci. 41, 578–594 (2016).

Pettitt, S. J. et al. Agouti C57BL/6N embryonic stem cells for mouse genetic resources. Nat. Methods 6, 493–495 (2009).

Consortium, G. T. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat. Genet 45, 580–585 (2013).

Pollock, J. D. et al. Mouse model of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, an inherited defect in phagocyte superoxide production. Nat. Genet 9, 202–209 (1995).

Winkelstein, J. A. et al. Chronic granulomatous disease. Report on a national registry of 368 patients. Med. (Baltim.) 79, 155–169 (2000).

Sweeney, C. L. et al. Targeted repair of CYBB in X-CGD iPSCs requires retention of intronic sequences for expression and functional correction. Mol. Ther. 25, 321–330 (2017).

Ranatunga, D. et al. A human IL10 BAC transgene reveals tissue-specific control of IL-10 expression and alters disease outcome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 17123–17128 (2009).

Sparwasser, T. & Eberl, G. BAC to immunology – bacterial artificial chromosome-mediated transgenesis for targeting of immune cells. Immunology 121, 308–313 (2007).

Yoshimi, K. et al. ssODN-mediated knock-in with CRISPR-Cas for large genomic regions in zygotes. Nat. Commun. 7, 10431 (2016).

McCray, P. B. Jr. et al. Lethal infection of K18-hACE2 mice infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Virol. 81, 813–821 (2007).

Tseng, C. T. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection of mice transgenic for the human Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 virus receptor. J. Virol. 81, 1162–1173 (2007).

Santilli, G. & Thrasher, A. J. A new chapter on targeted gene insertion for X-CGD: do not skip the intro(n). Mol. Ther. 25, 307–309 (2017).

Gaudelli, N. M. et al. Programmable base editing of A*T to G*C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature 551, 464–471 (2017).

Anzalone, A. V. et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature 576, 149–157 (2019).

Zhang, Y., Buchholz, F., Muyrers, J. P. & Stewart, A. F. A new logic for DNA engineering using recombination in Escherichia coli. Nat. Genet 20, 123–128 (1998).

Concordet, J. P. & Haeussler, M. CRISPOR: intuitive guide selection for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing experiments and screens. Nucleic Acids Res 46, W242–W245 (2018).

Anderson, B. D. et al. Natural APOBEC3C variants can elicit differential HIV-1 restriction activity. Retrovirology 15, 78 (2018).

Ikeda, T. et al. HIV-1 restriction by endogenous APOBEC3G in the myeloid cell line THP-1. J. Gen. Virol. 100, 1140–1152 (2019).

Ikeda, T. et al. APOBEC3 degradation is the primary function of HIV-1 Vif, determining virion infectivity in the myeloid cell line THP-1. mBio 14, e0078223 (2023).

Brown, W.L. et al. A rabbit monoclonal antibody against the antiviral and cancer genomic DNA mutating enzyme APOBEC3B. Antibodies 8, 47 (2019).

Wang, J., Shaban, N.M., Land, A.M., Brown, W.L. & Harris, R.S. Simian immunodeficiency virus vif and human APOBEC3B interactions resemble those between HIV-1 Vif and human APOBEC3G. J Virol 92, e00447–e00518 (2018).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915 (2019).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 24–26 (2011).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general-purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to K. Miyazaki, S. Nagata, M. Li, H. Chiba, Y. Hayashi, N. Takoh, R. Sakamoto, R. Kimoto, A. Iwama, K. Yamaguchi, Y. Furukawa, N. Misawa and J. Ito for their technical assistance, N. Sugimoto for her support on grammatical correction, and Dr. Reuben Harris for sharing the reagents. This study was supported by T. Ando in the Pathology Core laboratory, The Institute of Medical Science (IMSUT), The University of Tokyo. M.O. was supported in part by the JSPS KAKENHI (23K27084). J.T. was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI (25K18393) and 2024 Inamori Research Grants. M.I. and M.O. were supported in part by the JSPS KAKENHI (21H05033).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.T. and M.O. designed this study and wrote the paper. J.T. conducted the experiments. M.K. supported the experiments related to mouse generation. H.J. and S.Y. performed hematological analysis. H.M. performed RNA-seq data analysis. R.S., K.S., and T.I. performed immunoblotting. Y.Y. and M.I. provided technical assistance.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yasuhiro Kazuki and Seiya Mizuno for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Taguchi, J., Kikuchi, M., Jeon, H. et al. A scalable two-step genome editing strategy for generating full-length gene-humanized mice at diverse genomic loci. Nat Commun 17, 356 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67900-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67900-4