Abstract

Lime-based precipitation, though widely adopted for wastewater phosphorus (P) removal, suffers from surface passivation. The passivation layer inhibits Ca2+ release, forcing excessive dosing while yielding low-quality sludge and effluent with elevated hardness and pH. Limestone, despite its economic and environmental benefits, exhibits limited efficacy under fluctuating alkalinity. Here, we develop a limestone-integrated electrochemical system that spatially decouples the dissolution and precipitation reactions. By strategically positioning limestone at the acidic anode, we ensure sustained Ca2+ release without passivation, while cathodic alkalinity enables efficient P recovery (85.7%). The system produces high-purity products (15.2 wt% P) at low energy consumption (14.8 kWh kg P–1) and delivers superior effluent quality. Beyond its robustness and capacity flexibility over long-term operation, the electrochemical strategy reduces overall costs by 73.2% and carbon emissions by 29.1%, positioning it as a cost-effective and sustainable alternative to traditional lime-based wastewater treatment with remarkable passivation resistance and resource recovery efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The over-exploitation of phosphate rock and inefficient phosphorus (P) use have exacerbated P scarcity and recurrent eutrophication1,2. To promote a more sustainable P cycle, P removal and recovery from industrial, agricultural, and municipal wastewater have been widely advocated3,4. Currently, lime-based chemical precipitation remains the dominant treatment for wastewater containing P, heavy metals, and fluoride5,6,7. Owing to its operational simplicity and cost-effectiveness, this method is considered a gold standard for neutralizing acidic phosphate-rich wastewater and removing phosphate (PO43–)7,8,9. The process typically involves dosing quicklime (CaO), hydrated lime (Ca(OH)2), or limestone (CaCO3). On dissolution, CaO generates Ca(OH)2 (Eq. 1), releasing Ca2+ and OH– into wastewater (Eq. 2). Under optimal conditions, this induces supersaturation of calcium phosphate (Ca-phosphate) species, leading to their precipitation (Eq. 3)10.

However, effective PO43– removal via lime-based precipitation typically requires either excessive CaO dosing or pre-treatment of CaO with large volumes of water to generate sufficient Ca(OH)2 and ensure adequate Ca2+ availability. For example, in treating highly acidic PO43–-laden wastewater, removing just 1.3 kg of P necessitates 14 kg CaO and 120 kg of water—representing a CaO dosage roughly four times the stoichiometric requirement7. This inefficiency likely stems from surface passivation of lime particles, whether CaO, Ca(OH)2, or CaCO3.

In soil systems, PO43– is known to nucleate with Ca2+ and precipitate on calcite mineral surfaces11. Similarly, when CaO-based adsorbents (e.g., fly ash or CaO-biochar) are used for aqueous P removal, Ca-phosphate forms on the adsorbent surface12,13, impairing reactivity. A parallel mechanism occurs in ammonium recovery via struvite precipitation, where brucite14,15 or MgO16 dissolution and struvite precipitation are coupled at the solid-liquid interface. This process creates a thin fluid boundary layer that inhibits further Mg2+ release. Likewise, during lime-based precipitation, in-situ Ca-phosphate likely coats the reagent surface, inducing passivation and reducing reagent utilization efficiency for PO43– removal17.

Unfortunately, the passivation process and its impacts on wastewater P removal efficiency remain poorly understood. Surface passivation is not unique to lime-based P removal—it also critically impairs other environmental processes, including struvite recovery14,15,16, lime-based heavy metal removal5,18, zerovalent iron oxidative corrosion19,20, and mineral carbonation21,22,23, where practical solutions are urgently needed. Beyond reducing P removal efficiency, surface passivation compromises the quality and recovery of the valuable products, as unreacted lime contaminates the recovered Ca-phosphate. For instance, in treating acidic PO43–-laden wastewater, removing 1.3 kg of P requires excessive lime dosing and water pre-treatment, ultimately producing 129 kg of poorly setting, Ca-rich sludge7. A fundamental understanding of passivation mechanisms and practical mitigation strategies is essential to optimize reagent utilization and enable high-purity fertilizer production.

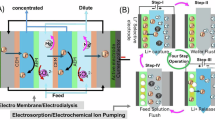

Electrochemical methods have garnered significant attention as next-generation wastewater treatment technologies24,25, with water electrolysis emerging as an up-and-coming platform26. This process splits water molecules via direct current, generating H+ at the anode and OH– at the cathode. These electrochemically produced ions have been successfully employed in diverse applications ranging from acid and base production27, water softening28, sludge leaching29, and electrochemically mediated precipitation30,31,32,33.

Building on this foundation, we present an innovative limestone-integrated electrochemical system designed to overcome the persistent challenges of surface passivation in conventional lime-based precipitation. Our system creates two functionally distinct zones: (1) an anodic region where dissolution is enhanced by locally generated H+ (Eqs. 4–5), ensuring continuous Ca2+ release while preventing particle passivation, and (2) a cathodic region where HER (hydrogen evolution reaction, Eq. 6) creates alkaline conditions for Ca-phosphate precipitation and collection (Eq. 3)34.

This system achieves three key advantages by overcoming surface passivation. First, Ca release is enhanced, and overdosing is avoided. The acidic anode region prevents surface passivation, maximizing reagent Ca release while eliminating the need for lime overdosing. This breakthrough makes low-solubility but cost-effective CaCO3 (Ksp = 10–9)35 (previously unsuitable for conventional precipitation) now fully applicable. Second, high-quality phosphate products are recovered: the cathodically formed Ca-phosphate precipitates as dense solids rather than sludge through homogeneous precipitation. The absence of lime overdosing further ensures product purity. Lastly, the system induces Ca-phosphate precipitation by creating a localized supersaturation at the cathode without elevating the bulk solution pH. This avoids the adjustment of the whole bulk pH and discharge of strongly alkaline effluent, as found in conventional lime-based precipitation.

This study investigates wood-based activated carbon (WAC) wastewater as a representative PO43–-laden stream. In the activated carbon industry, phosphoric acid activation generates acidic, PO43–-rich effluents7. We first evaluate three conventional lime-based precipitation methods (CaO, Ca(OH)2, and CaCO3), elucidating their surface passivation mechanisms and limitations. Subsequently, we demonstrate the effectiveness of our limestone-integrated electrochemical system in overcoming these challenges through targeted experiments and mechanistic analysis. A comprehensive comparison between electrochemical and conventional methods is presented, assessing PO43– removal efficiency, reagent utilization, product quality, and effluent characteristics. The system’s additional benefits, particularly in terms of chemical oxygen demand (COD) reduction, are also quantified. Techno-economic analysis (TEA) and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) highlight the operational advantages of the electrochemical approach, supporting its practical implementation. This work provides an innovative solution to surface passivation in phosphate recovery and offers insights applicable to other processes (i.e., mineral carbonization) plagued by similar interfacial limitations.

Results

Thermodynamic insights

The WAC wastewater exhibits strong acidity (pH 1.9) due to residual phosphoric acid from the activation process, with phosphate (1244.4 mg L–1) as the dominant anion (Supplementary Table 1). Minor metal cations (Ca2+, K+, Na+, Mg2+, and Al3+) are present, alongside high turbidity (255.6 NTU) from activated carbon fines and elevated COD (438.0 mg L–1) from tail gas treatment7. The existing lime-based precipitation systems struggle with three key inefficiencies: (1) excessive lime demand due to surface passivation, (2) voluminous, poor-settling sludge, and (3) highly alkaline effluents, undermining economic and ecological sustainability.

To address these limitations, Ye et al. proposed fluidized-bed struvite crystallization for WAC wastewater treatment7. The authors highlighted that the wastewater’s firm acidity enhances MgO dissolution, lowering reagent demand while producing struvite as a slow-release fertilizer7. However, both CaO and MgO dosing face inherent particle passivation issues. Given CaO’s cost advantages over MgO, our study explicitly targets surface passivation in lime precipitation. Before conducting lime dosing experiments, we modeled the effects of Ca2+ supply and pH elevation using Hydra-Medusa software. Phosphate speciation in WAC wastewater, initially dominated by H3PO4 and H2PO4–, progressively shifted to HPO42– and PO43– with increasing pH (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Notably, precipitation only occurred upon Ca2+ introduction, as pH adjustment alone proved insufficient. At a Ca/P molar ratio of 1:1, brushite (CaHPO4·2H2O) began precipitating at pH ~3.5 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The system favored the formation of thermodynamically stable hydroxyapatite (Ca5(PO4)3OH, HAP) under neutral to basic conditions10. Accordingly, complete P removal was realized at an elevated Ca/P ratio of 1.67:1 to account for HAP formation (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Interestingly, excess Ca2+ (Ca/P ratio of 3:1 or 4:1) lowered the pH threshold due to enhanced thermodynamic driving forces (Supplementary Fig. 1d, e), demonstrating the critical role of Ca2+ concentration in precipitation kinetics.

Mechanistic insights on lime surface passivation

While thermodynamic modeling suggested that lime dosing at a Ca/P of 1:1 should achieve almost complete P removal (based on brushite’s stoichiometry, Supplementary Fig. 1b), experimental results revealed only 2.3% of P removal at this ratio. Even at the theoretically optimal Ca/P ratio for HAP formation (1.67:1), merely 60.1% P removal was achieved (Fig. 1a). Significant P removal efficiencies (91.9–100.0%) required substantial lime overdosing at Ca/P ratios of 3:1 and 4:1, respectively.

a The P removal efficiency under increasing Ca/P dosing ratios in lime precipitation. b The visual presentation of the granules generated. c The particle size distribution (in wt%) of the granular products obtained from various Ca/P dosing ratios in lime precipitation. d Schematic diagram of the surface passivation process in lime precipitation. e The XRD patterns of the ground dried products from various Ca/P dosing ratios in lime precipitation. f The cross-sectional SEM image of a 1.0–2.0 mm granule and the corresponding elemental mapping of Ca (g), P (h), and O (i). j The reagent usage efficiencies of lime in P removal. Data with error bars represented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3). a.u. refers to arbitrary units.

Notably, despite using fine lime powder (<0.15 mm) with vigorous mixing, granules with varying sizes were generated after dosing (Fig. 1b), exhibiting a broad particle size distribution up to 6.0 mm (Fig. 1c). At Ca/P 1:1, only 28.4 wt% of particles were below 0.15 mm, with the remainder distributed across multiple size fractions: 19.9 wt% (0.15–0.5 mm), 16.8 wt% (0.5–1.0 mm), 18.8 wt% (1.0–2.0 mm), 4.1 wt% (2.0–3.0 mm), 9.6 wt% (3.0–4.0 mm), and 2.4 wt% (4.0–5.0 mm) (Fig. 1c).

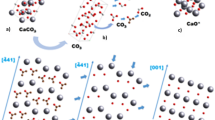

The observed reduction in P removal and the formation of granular products stem from surface passivation during lime precipitation. When lime is introduced to the aqueous system, it rapidly hydrates to Ca(OH)2, releasing substantial heat (ΔH298K = –104 kJ mol–1)36 and consuming water. This exothermic reaction dramatically decreases Ca(OH)2 solubility with increasing temperature, promoting rapid nucleation and growth of Ca(OH)₂ crystals that readily agglomerate (Fig. 1d)—a phenomenon well-documented in lime-based thermochemical heat storage materials37,38.

In wastewater treatment, these agglomerates release Ca2+ and OH–, creating localized conditions favorable for Ca-phosphate precipitation. Due to its low solubility product (Ksp = 10–6.59 for brushite)39, Ca-phosphate readily forms a passivation layer on particle surfaces, inhibiting further Ca2+ release and limiting P removal (Fig. 1d). Solid-phase characterization confirmed this mechanism: XRD analysis identified that brushite and Ca(OH)2 coexist as primary phases (Fig. 1e). Cross-sectional SEM revealed a distinct core-shell structure (Fig. 1f), with a shell thickness of around 20 μm (Supplementary Fig. 2). The associated elemental mapping showed that Ca and O are present evenly throughout the particles, while P is exclusively concentrated in the shell layer (Fig. 1g–i). The flake-like morphology of the shell layer of the generated granule (Supplementary Fig. 3), as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4a, corroborated its brushite composition40,41. Moreover, the even distribution of Ca, P, and O on the shell layer (Supplementary Fig. 4b–d), with nearly identical atomic percentages of Ca (10.7 atom%) and P (10.1 atom%), further confirms that the shell layer is composed of brushite (Supplementary Fig. 4e). In contrast, the core of the granules only contains Ca and O, with a ratio (1:2) consistent with that of Ca(OH)₂ (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b).

Surface passivation significantly reduces lime utilization efficiencies in P removal. Consequently, at a Ca/P of 1:1, only 2.0% of the dosed lime is effectively utilized (Fig. 1j). The passivation process renders a substantial portion of Ca(OH)₂ inactive, and even the dissolved fraction fails to elevate pH (4.0) sufficiently for adequate Ca-phosphate precipitation despite available Ca2+ (Fig. 2a, b). While increasing the Ca/P of 1.67:1 improves P removal and raises lime use efficiency to 32.1%, further overdosing to Ca/P = 4:1 (required for complete PO43– removal) reduces efficiency to 20.9% (Fig. 1j). The fundamental mechanism of surface saturation-induced passivation appears widely applicable across chemical systems. For example, in the realm of struvite precipitation, MgO/Mg(OH)2 surfaces experience passivation through struvite overgrowth, limiting dissolution and reagent efficiency14,16,42,43. Likewise, silicate minerals or alkaline solid waste show comparable carbonate-induced passivation during CO2 capture21,22,23.

The final pH (a) and Ca concentration (b) of the effluents under increasing Ca/P dosing ratios in lime precipitation. c Images of lime-treated WAC wastewater. The product purity (d) and moisture content (e) of the obtained sludges from various Ca/P dosing ratios in lime precipitation. Data with error bars represented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3).

Notably, our study reveals a distinct phenomenon not reported in the literature: the formation of mm-scale granules during lime treatment. This unique observation suggests that lime’s characteristic exothermic conversion to Ca(OH)₂, combined with the subsequent agglomeration caused by Ca(OH)2’s retrograde solubility behavior, may constitute the critical mechanistic step leading to passivation.

To verify this hypothesis, we performed comparative experiments using preformed Ca(OH)₂ (Supplementary Fig. 6). Strikingly, at a Ca/P molar ratio of 1:1, Ca(OH)₂ dosing achieved 98.2% PO₄³⁻ removal efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 6a), representing a dramatic improvement over the mere 2.3% efficiency observed with lime under identical conditions (Fig. 1a). Simultaneously, the reagent usage efficiencies of hydrated lime (37.9–106.1%) were notably higher than that of lime (Supplementary Fig. 6c). This improved performance originates from the fundamental difference in dissolution behavior: Ca(OH)₂ directly provides Ca2+ and OH– ions without undergoing the agglomeration associated with lime’s exothermic hydration process. Consequently, Ca(OH)2 dosing facilitates phase-pure brushite production when dosed appropriately (Supplementary Fig. 6d). Still, owing to the intrinsic nature of homogeneous crystallization in chemical precipitation, marked by instantaneous high supersaturation and the generation of dispersed small nuclei, even hydrated lime—despite avoiding passivation—inevitably forms poorly settling sludge (Supplementary Fig. 6e) with high water content (Supplementary Fig. 6f). This ultimately results in a low P content in the collected sludge (3.7–6.1 wt% P, Supplementary Fig. 6g).

Overall, these findings provide conclusive evidence that lime passivation originates from three sequential phenomena: (1) the exothermic hydration of lime to form Ca(OH)₂, followed by (2) particle agglomeration induced by the retrograde solubility characteristics of Ca(OH)2, and (3) the complete coverage of the agglomerates by the Ca-phosphate layer. This mechanistic understanding represents a significant advancement in our knowledge of phosphate precipitation processes, explaining the previously observed limitations of lime-based treatment approaches.

Lime passivation compromises effluent and product quality

Lime passivation not only reduces P removal efficiency but also compromises effluent and product quality. Achieving adequate P removal (e.g., at Ca/P = 4:1) requires excessive lime dosing, yielding an alkaline effluent (pH 12.7) with elevated Ca2+ (936.7 mg L–1, Fig. 2a, b), increasing scaling risks as well as post-treatment efforts in the downstream process44. Moreover, lime precipitation consistently produces low-quality sludge across all Ca/P dosing ratios (Fig. 2c, d), thereby dictating their current destination as hazardous alkaline waste in practical applications7. The passivation was a key driver in reducing P content, leading to unreacted Ca(OH)₂ contamination in the generated sludge. At Ca/P = 1:1, the P content is only 0.6 wt% (Fig. 2d), which is far below the theoretical value of brushite (18.0 wt% P). At Ca/P = 1.67:1, purity improves to 6.9 wt% P with higher P removal. Further overdosing (Ca/P = 4:1) ensures P removal but reduces purity to 2.9 wt% P due to excess Ca(OH)2.

Another factor contributing to the inferior quality of the sludge turns out to be the high moisture content. The collected product exhibited elevated moisture contents (52.0–74.2%), showing a distinct trend with varying Ca/P ratios (Fig. 2e). Moisture levels remained high at Ca/P = 1:1 (70.0%), decreased to 52.0% at 1.67:1, and peaked at 74.2% under overdosed conditions (Ca/P = 4:1). This non-monotonic trend inversely correlated with both CaO utilization efficiency (Fig. 1j) and product purity (Fig. 2d), suggesting a mechanistic link to the Ca(OH)₂ content in the solids.

We attributed this behavior to two key factors: (1) the hygroscopic nature of Ca(OH)₂, whose hydroxyl groups promote stronger water retention than crystalline Ca-phosphate; (2) the amorphous structure of Ca(OH)2-rich solids, which enhances moisture adsorption capacity. At a low Ca/P ratio (1:1), passivation leaves substantial unreacted Ca(OH)₂ in the product, elevating moisture. Improved CaO efficiency at an intermediate ratio (1.67:1) increases crystalline brushite content in the obtained product, reducing hygroscopicity. However, excessing dosing (4:1) reintroduces Ca(OH)₂ dominance, maximizing moisture retention. These findings align with known material properties—Ca-phosphates like brushite exhibit lower water affinity than Ca(OH)₂, consistent with our observed moisture trends.

Limited efficacy of limestone dosing

Lime and hydrated lime production are highly carbon- and energy-intensive processes. Direct use of their precursor material, limestone, could substantially reduce carbon emissions, manufacturing costs, and transportation hazards associated with corrosive chemicals (Fig. 3a). However, our experiments revealed severe limitations in limestone’s P removal capability: at Ca/P ratios of 1:1, 1.67:1, and 3:1, only 0.3%, 0.8%, and 0.4% P removal were achieved, respectively, after settling (Fig. 3b). Even at a 4:1 ratio, P removal efficiency plateaued at merely 11.0%, with CaCO3 remaining the dominant solid phase (Fig. 3d).

a Images of limestone-treated WAC wastewater. The P removal efficiency (b) and Ca concentration (c) right after mixing and post-settling under increasing Ca/P dosing ratios in limestone dosing. d The XRD patterns of the ground dried products from various Ca/P dosing ratios in limestone dosing. e Schematic diagram of the Ca-phosphate crystallization and redissolution in limestone precipitation. Data with error bars represented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3).

This poor performance stems from fundamental chemical constraints. While limestone can dissolve to release Ca2+ and create localized high-pH microenvironments at its surface—enabling transient Ca-phosphate precipitation—it cannot directly supply sufficient OH– to maintain bulk wastewater alkalinity (Fig. 3e). Consequently, precipitates re-dissolve as they encounter the low-pH bulk solution (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 7). This mechanism is supported by two key observations: initial P removal (5.6–94.4%, after 1-h mixing) was significantly higher than final removal (0.3–11.0%, after proper settling) (Fig. 3b); corresponding increases in aqueous Ca2+ concentrations (e.g., from 203.2 to 961.8 mg L–1 at Ca/P = 4:1, Fig. 3c) confirmed precipitate instability.

These findings highlight a fundamental limitation of chemical precipitation approaches: the inseparable coupling of Ca2+ release and phosphate precipitation. In lime systems, this coupling causes surface passivation on Ca(OH)2 agglomerates. For limestone, it leads to precipitate redissolution unless spatial separation can be achieved, where limestone dissolves in acidic zones while phosphate products remain stabilized in alkaline regions.

Spatially decoupled electrochemical strategy for enhanced calcium release and phosphate recovery

Water electrolysis offers a viable solution by establishing a sustained and distinctly differentiated acidic condition at the anode and an alkaline condition at the cathode. Water oxidation delivers an acidic region at the anode, in which limestone undergoes continuous dissolution, steadily supplying Ca2+. Furthermore, the acidity suppresses Ca-phosphate formation on the limestone surface, effectively preventing surface passivation. Meanwhile, the HER creates an alkaline region at the cathode where Ca-phosphate precipitates are stabilized without redissolution.

Anodic acidity for passivation elimination

To implement this configuration, limestone was positioned adjacent to the anode, with a Ru-Ir mesh basket functioning as both the anode and a porous container (Fig. 4a). The Ca2+ release kinetics were initially evaluated in a 10 mM Na2SO4 electrolyte without PO43–, with the pH pre-adjusted to 1.9. At a current density of 18 A m–2, the Ca2+ concentration steadily increased, reaching 470.6 mg L–1 in 2 h (Supplementary Fig. 8a), while the solution pH rose to 6.1 (Supplementary Fig. 8a)—consistent with limestone dissolution driven by electrochemically generated H+. Notably, Ca2+ release correlated with current density: higher currents produced more H+, intensifying the H+-limestone reaction and enhancing Ca2+ release (Supplementary Fig. 8b). These results underscore the critical role of anodic acidity in sustaining Ca2+ supply.

a Schematic diagram of the passivation mitigation by anodic acidity and stable precipitation by cathodic alkalinity, with driving forces of Ca²⁺ and H₃₋ₓPO₄⁽ˣ⁻³⁾ ions labeled. b The evolution of Ca2+ concentration over electrolysis under various current densities. The SEM images of the pristine limestone (c) and post-use limestone (e). Element mapping of the pristine limestone (d) and post-use limestone (f). The Raman spectrum (g) and XRD pattern (h) of pristine and post-use limestone. Condition: 18 A m–2; 1 L; 36 h. Data with error bars represented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3).

In PO43–-rich WAC wastewater, Ca2+ concentrations displayed a characteristic rise-and-fall trajectory across all tested current densities (Fig. 4b). Under conditions of stable H+-limestone reactivity, this trend reflected progressively intensifying Ca-phosphate precipitation throughout electrolysis. During the initial phase (<8 h), the system exhibited net Ca2+ accumulation, as precipitation kinetics were constrained by the low baseline Ca2+ concentration (79.3 mg L–1 Ca compared to 1244.4 mg L–1 P, Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 1). This accumulating Ca2+ elevated the saturation index (SI) of Ca-phosphate species (Eq. 8), thereby increasing the thermodynamic driving force for precipitation. As the reaction progressed, Ca2+ consumption eventually outpaced supply, leading to a net concentration decline. Critically, higher current densities amplified this effect: by enhancing the thermodynamic driving force at the cathode, they accelerated Ca-phosphate precipitation34, ultimately yielding lower residual Ca2+ levels. Notably, one may argue that the inherent acidity of WAC wastewater may also play a role in Ca supply. Indeed, while Ca2+ release correlated with current density in the absence of PO43-, the trend observed is relatively modest. For instance, increasing the current fourfold from 4.5 to 18 A m–2 only increased Ca2+ release from 455.2 to 479.2 mg L–1 in 2 h (Supplementary Fig. 8b). As demonstrated in the limestone chemical dosing, the low pH of the WAC wastewater itself could indeed contribute to limestone dissolution and Ca2+ supply in the first place. However, the subsequent precipitation and redissolution of Ca-phosphate remained an inevitable limit (Fig. 3e). Thus, while the acidity of WAC wastewater could contribute to limestone dissolution, the key to stable and efficient Ca2+ supply lies in sustained anodic acidity, specifically by preventing surface passivation.

We noticed that continuous operation for 36 h under 18 A m–2 preserved the original limestone morphology with no observable alterations (Fig. 4c, e). Post-reaction characterization confirmed the maintained bulk composition (Ca, C, and O) without P enrichment (Fig. 4d, f), as evidenced by both surface analysis and acid-digestion elemental comparisons (Supplementary Table 2). The passivation resistance stemmed from the persistently acidic anodic environment (pH<3.5 at 18 A m–2, Supplementary Fig. 9), which remained below the threshold required for Ca-phosphate precipitation—consistent with the thermodynamic predictions (Supplementary Fig. 1)—while still being sufficiently acidic, ensuring Ca2+ supply via limestone dissolution.

The absence of passivation was further verified by spectroscopic analyses. Raman spectroscopy revealed preserved calcite signatures, with the characteristic ν₁ symmetric CO32– stretch at 1087 cm–145, along with associated peaks at 155, 282 (ν₂), and 714 cm–1 (ν₄) (Fig. 4g). Similarly, XRD patterns matched reference calcite profiles (Fig. 4h). Notably, unlike lime, which readily forms Ca-phosphate passivation layers, the electrolysis-integrated limestone showed no evidence of secondary mineral phases, confirming the effectiveness of anodic acidification in maintaining surface reactivity.

Cathodic alkalinity for enhanced phosphate recovery

The limestone-integrated electrochemical system maintains stable anodic acidity while generating cathodic alkalinity via HER, creating a localized high-pH environment at the cathode without significantly increasing the bulk pH34. Combined with Ca2+ supplied from the anode, this configuration establishes ideal supersaturation conditions for Ca-phosphate crystallization at the cathode surface, enabling efficient P precipitation and recovery (Fig. 4a). As primary ions in this framework, the migration of Ca²⁺ and H₃₋ₓPO₄⁽ˣ⁻³⁾ toward the cathode is primarily driven by mass diffusion, driven by their consumption due to precipitation (Fig. 4a). For cations such as Ca²⁺, electromigration also plays a role in their movement toward the cathode. Importantly, in addition to mass diffusion, H₃₋ₓPO₄⁽ˣ⁻³⁾, as a buffer, tends to react with OH– generated, further promoting its migration toward the cathode (Fig. 4a). While the electric field opposes H₃₋ₓPO₄⁽ˣ⁻³⁾ migration, among the three current-related driving forces, the combined influence of mass diffusion and buffering predominates, as evidenced by the positive correlation between current and P removal (Fig. 5a), rather than a decline, which would be expected if electromigration prevailed.

a The P recovery performance at various current densities. The XRD patterns (b) and product purity (c) of the recovered products by electrochemical method across various currents. d The images of the cathode and dense precipitates collected. e the pH evolution over electrolysis under various current densities. f the specific energy consumption under all current densities. Data with error bars represented as mean ± s.d. (n = 3).

Specifically, P removal efficiency demonstrated strong current-dependence: 36.0% P at 4.5 A m–2 (36 h), increasing to 47.3% at 9 A m–2 and reaching 85.7% at 18 A m–2 (Fig. 5a). This enhancement arises from intensified electrode reactions at higher currents: accelerated H+ generation at the anode improves limestone dissolution kinetics and Ca2+ release; enhanced HER at the cathode creates more pronounced local alkalinity. The synergistic effect of increased Ca2+ availability and elevated local pH provides a greater thermodynamic driving force for Ca-phosphate crystallization, ultimately boosting P recovery efficiency.

XRD and SEM-EDS analyses confirmed Ca-phosphate crystallization in the recovered products. As shown in Fig. 5b, the product obtained at 4.5 A m–2 displayed distinct brushite patterns. SEM reveals the characteristic stacked plate-like morphology of this crystalline phase with even distribution of Ca, P, and O (Supplementary Fig. 10a–d). EDS analysis of selected plate-like products further verified brushite formation, showing consistent Ca/P ratios (~1.0) across sampled regions (Supplementary Fig. 10e, f). However, at higher current densities (18 A m–2), the appearance of a broadened peak around 2θ = 30°—accompanied by sphere particles in SEM images with uniform distribution of Ca, P, and O (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 11a–d)—indicated the formation of amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP). This current-dependent crystallinity transition aligns with established literature demonstrating that rapid pH elevation in complex wastewater matrices promotes ACP formation10,32,46,47. Specifically, the combination of high local alkalinity at elevated current densities and the presence of interfering species (e.g., Mg2+ and NOMs) can inhibit the transformation of ACP into crystalline phases, explaining our observed predominance of amorphous products under more intensive operating conditions.

Notably, the electrochemical approach achieves superior Ca-phosphate recovery (13.9–15.2 wt% P) compared to conventional lime precipitation (0.6–6.9 wt% P) by fundamentally addressing its key limitations (Fig. 5c). Unlike lime systems, where surface passivation necessitates reagent overdosing and compromises product purity, the electrochemical method prevents passivation through spatially separated reaction zones. The physical segregation enables Ca-phosphate crystallization to proceed without limestone interference, yielding high-purity products. More importantly, electrochemically induced heterogeneous precipitation provides sustained supersaturation conditions that preferentially promote post-nucleation growth, forming larger Ca-phosphate particles that aggregate into dense, low-moisture precipitates (Fig. 5d). In contrast, conventional chemical precipitation creates instantaneous high supersaturation, generating numerous small nuclei dispersed as high-water-content sludge with poor settling properties—a direct consequence of rapid, uncontrolled homogeneous nucleation32,48.

The electrolysis process induced gradual pH elevation in WAC wastewater, reaching 4.4, 4.2, and 4.0 after 36 h at current densities of 4.5, 9, and 18 A m–2, respectively (Fig. 5e). This pH increase results from two coupled processes: H+ consumption during limestone dissolution (Eq. 5) and OH– accumulation through cathodic HER (Eq. 6). All current conditions displayed similar temporal patterns—rapid pH increase within the initial 8 h followed by stabilization and eventual slight decline at 4.5 and 9 A m–2. This behavior confirms our previous observation that OH– consumption by Ca-phosphate crystallization begins to dominate over H+-consumption (from Ca2+ release) after approximately 8 h of operation. The inverse current density-pH relationship reflects enhanced OH– consumption at higher current densities, where accelerated Ca-phosphate precipitation occurs. More importantly, the electrochemical approach demonstrates significant advantages over conventional lime precipitation in effluent quality (Figs. 4b and 5e). At optimal P removal conditions (18 A m–2), the system produced effluent with markedly low residual Ca2+ (88.6 mg L–1) and pH (4.0), compared to lime treatment (936.7 mg L–1 Ca2+, pH 12.7 at Ca/P = 4:1), not to mention its low specific energy consumption (14.8-19.5 kWh kg P–1, Fig. 5f) and competitive cost efficiency ($1.4-1.9 kg P–1 removed) within a wide range of processes targeting P removal/recovery ($1.4-422.3 kg P–1 removed at 5.6-1300.0 mg L–1 P) (Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Table 3). This breakthrough eliminates two major drawbacks of lime-based systems: scaling risks from high Ca2+ concentrations44 and two-step pH swing (alkalinization and neutralization). On top of passivation elimination and enhanced P recovery, the electrochemical system demonstrated a notable added capability for COD removal. In chemical precipitation, lime, hydrated lime, and limestone dosing exhibited only modest COD removal of 6.7–13.0%, 8.4–11.0%, and 7.4–15.9% (Supplementary Fig. 13), respectively, likely due to co-precipitation by the generated sludge47,49. In contrast, even at a low current density of 4.5 A m–2, the electrochemical system achieved a COD removal efficiency of 79.3%, which increased to a maximum of 87.0%, as the current density was elevated to 18 A m–2 (Supplementary Fig. 13). This enhanced COD removal may be attributed to anodic direct oxidation and active chlorine species generation at the inert anode50, with chloride ions (Cl–) present in the WAC wastewater at 127.5 mg L–1 (Supplementary Table 1).

Long-term robustness and implementation outlook

To evaluate the long-term performance and stability of the spatially decoupled electrochemical strategy, we conducted a 864-h (36-d) continuous operation with the same setup. At an initial setting (9 A m–2; HRT 36 h), the system attained 60.0% P recovery within the first few days (Supplementary Fig. 14). Upon increasing the current to 18 A m–2, the P recovery remained stable at 86.2–96.5% for over a week (Supplementary Fig. 14). Anticipating scenarios that require higher treatment capacities, the HRT was shortened to 6 h, and the current density was further elevated to 72 A m–2 following a decline in recovery efficiency. Subsequently, the system shows promising P recovery stabilizing between 72.9–93.3% under 72 A m–2 and HRT 6 h for a further 20 days (Supplementary Fig. 14). Throughout the operation, limestone was replenished on days 21 and 35 upon noticing a decline in P recovery, highlighting the importance of adequate limestone supply in the system’s practical implementation. Overall, the system displayed good stability and flexible recovery capacity via the conditions tuning. The continuous anti-passivation and utilization of limestone were further validated under prolonged operation. Even excluding the limestone that was fully consumed, the remaining limestone exhibited a notable decrease in particle size, shifting from an initial dominant range of 2.0–3.0 mm to 1.0–2.0 mm, with a minor fraction falling below 1.0 mm (Supplementary Fig. 15). Throughout the dissolution, the surface of the limestone remained consistent (Supplementary Fig. 16a). The limestone before and after long-term operation both exhibited strong Ca 2p signals, indicative of CaCO3, with no P detected (Supplementary Fig. 16b, c). These findings collectively illustrate that limestone underwent continuous dissolution from the outside in and maintained its resistance to passivation throughout utilization.

The electrochemical cell’s durability is pivotal for practical applications. Inspiringly, the Ru-Ir coated Ti anode, renowned for its electrochemical stability, exhibited exceptional performance with no detectable Ru or Ir leaching over the extended operation (Supplementary Table 4). Importantly, the precipitates/products remained on the cathode over extended use. These precipitates/products can be effectively harvested via physical scraping without compromising the integrity of the cathode, allowing its prompt cleaning and reuse for the next cycles (Supplementary Fig. 17). Foreseeing more automated implementations, scraper integration51 and polarity reversal52 are promising options for product collection and electrode refreshing.

Cutting costs and alleviating emissions

To assess the potential of the electrochemical process for the iteration of the typical industrial lime-based precipitation process, the ongoing WAC wastewater treatment (20.8 m3 h–1) was selected as a scenario, where a TEA was performed for both the existing processes and the electrochemical process. The detailed calculations of capital expenditure (CAPEX) and operating expenditure (OPEX) were outlined in Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Tables 5, 6. The electrochemical process inevitably entails a higher CAPEX ($398,300) than the existing lime/hydrated lime precipitation process ($312,000), with the anode representing the major share (72.0%) (Supplementary Table 5). Allocating the CAPEX as depreciation over the system’s lifespan yields a cost of $0.109 m–3 at a 5% depreciation rate (Supplementary Table 6).

Inspiringly, by overcoming the key limitations of lime-based precipitation, the limestone-integrated electrochemical technique notably reduces the OPEX towards WAC wastewater, far offsetting the CAPEX (Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Note 1). Specifically, the lime precipitation currently represents the highest total cost ($3.503 m–3), with substantial portions allocated to limestone expenditure (23.0%) and calcination (25.2%), both of which can be attributed to the substantial increase in limestone consumption due to reagent surface passivation. More importantly, lime overdosing derives a considerable amount of hazardous alkaline sludge, leading to inevitably high sludge dewatering and disposal costs, which are the dominant cost factors (36.7%) (Supplementary Table 6). While reagent passivation would not occur in hydrated lime precipitation and the total cost is reduced to $1.699 m–3, it still cannot circumvent the expenses associated with limestone calcination (13.0%) and the inevitable dewatering and disposal of the substantial sludge produced by chemical precipitation (44.7%) (Supplementary Table 6). By avoiding reagent surface passivation, the limestone-integrated electrochemical system, on the one hand, eliminates limestone overdosing, maintaining the limestone expenditure at $0.201 m–3, notably lower than that of lime precipitation ($0.804 m–3). On the other hand, as the system delivers Ca2+ under ambient temperature and pressure, the cost-intensive limestone calcination was also circumvented. Instead of alkaline sludge, the recovered dense, high-purity Ca-phosphate by the electrochemical method serves as P fertilizer, obtaining a revenue of $1.802 m–3. Thanks to these improvements, the limestone-integrated electrochemical system notably reduces the overall cost to $0.939 m–3 (Supplementary Table 6). It is worth noting that the main cost driver for the electrochemical method remains electrical energy consumption (72.8%), which holds great potential to be optimized in future studies by enhancing the interaction between H⁺ and limestone (e.g., via limestone grinding)53. Collectively, the process iteration is expected to bring 73.2% overall cost savings in its lifespan.

Furthermore, environmental benefits are anticipated by implementing a limestone-integrated electrochemical system to replace the existing lime precipitation. The two LCA scenarios are depicted in Fig. 6b, with calculation details documented in Supplementary Note 2. As illustrated in Fig. 6c, the electrochemical strategy (12.60 kg CO2 eq) results in lower CO2 emissions than the routine lime treatments (17.78 kg CO2 eq), for each m3 of wastewater processed. The CO₂ emissions in the current situation primarily originate from lime manufacture (11.24 kg CO2 eq), which is carbon-intensive and further exacerbated by passivation-induced excessive lime demand. Simultaneously, the disposal of hazardous alkaline sludge resulting from passivation contributes 1.63 kg CO2 eq, alongside the manufacture of Ca-phosphate fertilizer (4.93 kg CO2 eq). By circumventing lime passivation and its associated detriments, the electrochemical method has demonstrated notably reduced CO2 emissions (12.60 kg CO2 eq) (Fig. 6c). While the construction of new electrochemical plants does incur certain carbon emissions (14258.17 kg CO₂ eq), this impact becomes minimal (0.07 kg CO2 eq) when normalized per m3 of wastewater, given the system’s high processing capacity. Notably, since the predominant emissions from the electrochemical method stem from electricity consumption (12.51 kg CO2 eq), integrating renewable energy could further reduce carbon emissions to 7.6% of those associated with the routine lime precipitation process (Fig. 6c). Despite the fact that electrode manufacturing contributes significantly to mineral resource scarcity (54.3%), the electrochemical strategy (0.02 kg Cu eq per m3 wastewater processed) is characterized by substantially less mineral resource scarcity than the routine method (0.19 kg Cu eq per m3 wastewater processed), as it reduces P fertilizer production and the corresponding ore extraction via efficient wastewater P recovery (Fig. 6d).

a Cost comparison and analysis of lime, hydrated lime, and the limestone-integrated electrochemical system. b Schematic representation of processes (bold) and material flows (italicized) in the life cycle assessment of the incorporation of a limestone-integrated electrochemical system (proposed scenario) in comparison to the current lime precipitation (baseline scenario). Evaluation of the environmental impacts of the two scenarios in terms of global warming potential with contribution analyses (c) and mineral resource scarcity (d).

Discussion

In this research, mechanistic insights towards surface passivation in conventional lime-based precipitation were first systematically investigated. Specifically, our key findings reveal that the exothermic hydration of lime induces retrograde solubility behavior, wherein elevated temperature reduces Ca(OH)2 solubility, thereby promoting particle agglomeration and subsequent Ca-phosphate precipitation at the same reactive interface. This cascade of reactions ultimately forms a passivation layer that severely limits Ca2+ release and P removal, highlighting the critical need to decouple Ca supply from P precipitation sites spatially. The lime passivation—governed by the retrograde solubility of Ca(OH)2—necessitates substantial over-dosing (up to Ca/P ratio of 4:1), ultimately yielding low-purity products (<6.9 wt% P) and poor effluent quality (936.7 mg L–1 Ca2+ and pH 12.7). While limestone presents an economically and environmentally favorable alternative, its efficacy remains critically limited (0.3–11.0% at Ca/P 1:1–4:1) due to rapid Ca-phosphate redissolution, underscoring the importance of stable alkalinity.

To address these inherent limitations, we developed a membrane-free, limestone-integrated electrochemical system featuring spatially separated acidic anodic (for Ca2+ release) and alkaline cathodic regions (for stable P precipitation). The strategic design of placing limestone in the anodic acidity enables two critical advances: (1) sustained Ca2+ supply (470.6 mg L–1 in 2 h) via controlled electrolysis and (2) complete inhibition of passivation layer formation. By circumventing lime passivation and the following over-dosing, the stable cathodic alkalinity facilitates recovery of high-purity phosphate products (13.9–15.2 wt% P) at remarkably low energy consumption of 14.8–19.5 kWh kg P–1. Most notably, the electrochemical system demonstrated superior performance at optimal conditions (85.7% at 18 A m–2), producing effluent with drastically improved quality (88.6 mg L–1 Ca2+, pH 4.0) compared to lime precipitation, effectively eliminating post-treatment risks (e.g., scaling) and neutralization costs associated with lime-based processes. These findings provide fundamental insights into passivation mechanisms while establishing an efficient electrochemical alternative characterized by passivation resistance, high-quality products, and effluents. Building upon mechanistic insights, the spatially decoupled electrochemical strategy demonstrates robustness and capacity flexibility over long-term operation, underscoring its implementation potential. The TEA and LCA project that the electrochemical strategy can achieve 73.2% cost savings and a 29.1% reduction in carbon emissions by overcoming the inherent limitations of routine lime precipitation. The pivotal function of the electrochemical method may further offer a paradigm shift for overcoming surface passivation challenges in precipitation-based processes (i.e., mineral carbonization for CO2 capture).

Methods

Chemicals

Analytical-grade and powdered CaO, Ca(OH)2, or CaCO3 were purchased from Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The limestone (1–2 mm) was received from Jinxin Mineral (Xuancheng, China), and its elemental composition is depicted in Supplementary Table 2. The WAC wastewater investigated in this research was collected from the regulating tank in a typical WAC factory in Nanping (Fujian, China), with physicochemical properties displayed in Supplementary Table 1.

Experimental procedure

Conventional lime-based precipitation

The performance of three typical lime (CaO, Ca(OH)2, and CaCO3) in WAC wastewater was systematically investigated. Four dosing ratios were implemented based on Ca/P molar ratios of 1:1, 1.67:1, 3:1, and 4:1, corresponding to CaHPO4·2H2O formation, Ca5(PO4)3OH precipitation, and calcium-excess conditions, respectively. For each lime-based precipitation experiment, reagents were added to 500 mL of WAC wastewater at designated dosing ratios under continuous agitation at 500 rpm. All precipitation experiments were processed with 1-h mixing to ensure a complete reaction, followed by 24-h settling.

Water samples were collected at three stages: before reaction, after mixing, and post-settling, for comprehensive analysis of critical parameters such as pH, element (e.g., Ca and P), and COD. The generated sludge was collected via vacuum filtration, air-dried, and subsequently subjected to characterization, including moisture content and P content quantification and solid-phase analyses (SEM, XRD, and Raman spectroscopy).

Limestone-integrated electrochemical method

The electrochemical system consisted of a 1.0 L reactor equipped with a Ru-Ir coated titanium mesh basket anode (∅ = 29 mm, h = 118 mm; coated density of 8 g m–2 Ru and 2 g m–2 Ir) and a tubular stainless steel 304 cathode (∅ = 90 mm, h = 120 mm; effective surface area of 111.1 cm2).

Each experiment was conducted with 25 g of limestone loaded in the basket anode. We systematically investigated the effects of current density (4.5, 9, and 18 A m–2, corresponding to applied currents of 50, 100, and 200 mA, respectively) on system performance and reaction mechanisms. All electrochemical experiments were conducted under constant current conditions using a DC power supply MN-155D from Zhaoxin (Shenzhen, China) at room temperature (20 ± 0.5 °C).

All experiments were performed using 0.5 L of WAC wastewater under continuous mixing (500 rpm) for 36 h. We conducted periodic sampling to monitor the temporal variations in critical parameters, including pH, element concentrations, and COD. Following reaction completion, the generated solids were air-dried for 24 h and then collected by gentle scraping. Subsequently, the recovered solids were subject to subsequent characterization of moisture content and P content quantification and solid-phase analyses. Unless stated otherwise, all experiments were performed in triplicate, and data are presented as mean with standard deviation (s.d.).

Sample analysis

Liquid analysis

Solution pH was measured immediately after sampling using a calibrated pH meter (SevenExcellence, METTLER TOLEDO). For elemental analysis, samples were first filtered through 0.45 μm membranes and appropriately diluted before measurement by ICP-OES (iCAP7400 Duo MFC, Thermo Scientific) to determine Ca, P, Mg, and other relevant element concentrations. For trace metals (e.g., Ru and Ir), ICP-Mass (iCAP RQ, Thermo Scientific) was employed. Turbidity was quantified at 860 nm using a Formazin calibration standard (Supelco Analytical, Germany) under ISO 7027 standards. COD was determined using HACH cuvette tests (2038215-CN) following the manufacturer’s protocols.

Solid analysis

The moisture content of the collected sludge was determined via 105 °C drying. The composition, including the P content of all products, was quantified by ICP-OES after nitric acid digestion. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, SU3800 Hitachi, Japan) coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, XFlash6130 Bruker, USA) and X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku SmartLab, Japan) was used to examine the morphology, elemental distribution, and phase composition of the collected products. Raman spectra were recorded using a Thermo Fisher Scientific DXR3 Laser Microscopic Raman Spectrometer, with spectra collected in the 300-1200 cm–1 range at a resolution of 2 cm–1 using a 532 nm excitation laser. For passivated granules generated in lime precipitation, particle size distribution was determined by sieve analysis. The limestone’s chemical composition was determined by an X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS, PHI 5000 Versaprobe III, ULVAC-PHI) with the monochromatic Al Kα radiation at a voltage of 15 kV and current of 5 mA.

Software simulation and calculational methods

The software package of Hydra and Medusa (version: Jan., 2016)54 was applied to simulate phosphate speciation in WAC wastewater in response to Ca2+ release and pH increase, enabling comprehensive prediction of phosphate species distribution across the experimental conditions examined.

The P removal efficiency in % was calculated with Eq. 7:

C0 and Ct mean the P concentrations before and after treatment (mg L–1).

The saturation index (SI) was calculated by Eq. 8:

IAP refers to the ion activity of the associated lattice ions, and Ksp refers to the solubility product.

As P in the sludge from lime-based precipitation exists exclusively in CaHPO4·2H2O, the reagent usage efficiency in lime-based precipitation was determined as follows (Eq. 9):

Careagent refers to the Ca content in the dosed reagent, and Psludge is the P content in the sludge collected from lime-based precipitation.

The moisture content of the sludge collected was calculated with Eq. 10:

where m0 and mt mean the weight of sludge before and after 105 °C drying (g).

The energy consumption (kWh) of the electrochemical system was calculated by Eq. 11:

where Ū and Ī are the recorded voltage (V) and current (I) on average over the electrolysis of a specific time (h).

Life cycle assessment and economic aspect

TEA was conducted to assess and compare the economic feasibility of the limestone-integrated electrochemical method to existing lime-based precipitation processes, based on lab-scale results and sourced inventory data (Supplementary Table 5 and 6). Calculation details can be found in Supplementary Note 1. The LCA was performed to evaluate the environmental impacts of both the limestone-integrated electrochemical method (proposed scenario) and conventional lime-based precipitation processes (baseline scenario). The assessment followed the framework and standards outlined in ISO14040/44 with background information from both lab-scale results and the Ecoinvent version 3 database. SimaPro software was employed to establish scenarios and assess environmental impacts using the ReCiPe Midpoint (H) v1.05 methodology. The system boundary and calculation details are presented in Fig. 6b and Supplementary Note 2, respectively.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of the study are included in the main text, Supplementary information and Source Data files. Raw data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Cordell, D., Drangert, J.-O. & White, S. The story of phosphorus: global food security and food for thought. Glob. Environ. Change 19, 292–305 (2009).

Elser, J. & Bennett, E. A broken biogeochemical cycle. Nature 478, 29–31 (2011).

Li, W.-W., Yu, H.-Q. & Rittmann, B. E. Chemistry: reuse water pollutants. Nature 528, 29–31 (2015).

Zheng, M. et al. Pathways to advanced resource recovery from sewage. Nat. Sustain. 7, 1395–1404 (2024).

Song, Y. et al. A novel approach for treating acid mine drainage by forming schwertmannite driven by a combination of biooxidation and electroreduction before lime neutralization. Water Res. 221, 118748 (2022).

Hu, X., Zhu, F., Kong, L. & Peng, X. A novel precipitant for the selective removal of fluoride ion from strongly acidic wastewater: synthesis, efficiency, and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 403, 124039 (2021).

Ye, X. et al. Dissolving the high cost with acidity: a happy encounter between fluidized struvite crystallization and wastewater from activated carbon manufacture. Water Res. 188, 116521 (2021).

Carvalho, F., Prazeres, A. R. & Rivas, J. Cheese whey wastewater: characterization and treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 445, 385–396 (2013).

Cichy, B., Kużdżał, E. & Krztoń, H. Phosphorus recovery from acidic wastewater by hydroxyapatite precipitation. J. Environ. Manag. 232, 421–427 (2019).

Wang, L. & Nancollas, G. H. Calcium orthophosphates: crystallization and dissolution. Chem. Rev. 108, 4628–4669 (2008).

Wang, L., Ruiz-Agudo, E. N., Putnis, C. V., Menneken, M. & Putnis, A. Kinetics of calcium phosphate nucleation and growth on calcite: implications for predicting the fate of dissolved phosphate species in alkaline soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 834–842 (2012).

Liu, X., Shen, F. & Qi, X. Adsorption recovery of phosphate from aqueous solution by CaO-biochar composites prepared from eggshell and rice straw. Sci. Total Environ. 666, 694–702 (2019).

Hermassi, M. et al. Fly ash as a reactive sorbent for phosphate removal from treated wastewater as a potential slow-release fertilizer. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 5, 160–169 (2017).

Hövelmann, J. R. & Putnis, C. V. In situ nanoscale imaging of struvite formation during the dissolution of natural brucite: implications for phosphorus recovery from wastewaters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 13032–13041 (2016).

Huang, H., Xiao, X., Yang, L. & Yan, B. Removal of ammonium from rare-earth wastewater using natural brucite as a magnesium source of struvite precipitation. Water Sci. Technol. 63, 468–474 (2011).

Romero-Güiza, M. et al. Reagent use efficiency with removal of nitrogen from pig slurry via struvite: a study on magnesium oxide and related by-products. Water Res. 84, 286–294 (2015).

Filippov, L., Kaba, O. & Filippova, I. Surface analyses of calcite particles reactivity in the presence of phosphoric acid. Adv. Powder Technol. 30, 2117–2125 (2019).

Tolonen, E.-T., Sarpola, A., Hu, T., Rämö, J. & Lassi, U. Acid mine drainage treatment using by-products from quicklime manufacturing as neutralization chemicals. Chemosphere 117, 419–424 (2014).

Li, J. et al. Improving the reactivity of zerovalent iron by taking advantage of its magnetic memory: implications for arsenite removal. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 10581–10588 (2015).

Wu, Y. et al. Enhancing and sustaining arsenic removal in a zerovalent iron-based magnetic flow-through water treatment system. Water Res. 263, 122199 (2024).

Weber, J. et al. Armoring of MgO by a passivation layer impedes direct air capture of CO2. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 14929–14937 (2023).

Chen, Z., Cang, Z., Yang, F., Zhang, J. & Zhang, L. Carbonation of steelmaking slag presents an opportunity for carbon neutral: a review. J. CO2 Util. 54, 101738 (2021).

Beerling, D. J. et al. Potential for large-scale CO2 removal via enhanced rock weathering with croplands. Nature 583, 242–248 (2020).

Alkhadra, M. A. et al. Electrochemical methods for water purification, ion separations, and energy conversion. Chem. Rev. 122, 13547–13635 (2022).

Miller, D. M. et al. Electrochemical wastewater refining: a vision for circular chemical manufacturing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 19422–19439 (2023).

Radjenovic, J. & Sedlak, D. L. Challenges and opportunities for electrochemical processes as next-generation technologies for the treatment of contaminated water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 11292–11302 (2015).

Lin, H.-W. et al. Direct anodic hydrochloric acid and cathodic caustic production during water electrolysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 20494 (2016).

Jiang, B. et al. A critical review on the electrochemical water softening technology from fundamental research to practical application. Water Res. 250, 121077 (2023).

Wang, Z. & He, Z. Electrochemical phosphorus leaching from digested anaerobic sludge and subsequent nutrient recovery. Water Res. 223, 118996 (2022).

Hug, A. & Udert, K. M. Struvite precipitation from urine with electrochemical magnesium dosage. Water Res. 47, 289–299 (2013).

Wang, Y. et al. Electrochemically mediated precipitation of phosphate minerals for phosphorus removal and recovery: progress and perspective. Water Res. 209, 117891 (2022).

Lei, Y., Zhan, Z., Saakes, M., van der Weijden, R. D. & Buisman, C. J. Electrochemical recovery of phosphorus from acidic cheese wastewater: feasibility, quality of products, and comparison with chemical precipitation. ACS EST Water 1, 1002–1013 (2021).

Lei, Y., Remmers, J. C., Saakes, M., van der Weijden, R. D. & Buisman, C. J. Is there a precipitation sequence in municipal wastewater induced by electrolysis? Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 8399–8407 (2018).

Lei, Y., Song, B., van der Weijden, R. D., Saakes, M. & Buisman, C. J. Electrochemical induced calcium phosphate precipitation: importance of local pH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 11156–11164 (2017).

Buljan Meić, I. et al. Comparative study of calcium carbonates and calcium phosphates precipitation in model systems mimicking the inorganic environment for biomineralization. Cryst. Growth Des. 17, 1103–1117 (2017).

García, Y. C., Martínez, I. & Grasa, G. Determination of the hydration and carbonation kinetics of CaO for low-temperature applications. Chem. Eng. Sci. 295, 120146 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. Agglomeration inhibition mechanism of SiO2 in the Ca(OH)2/CaO thermochemical heat storage process: a reactive molecular dynamics study. Chem. Eng. J. 480, 148118 (2024).

Criado, Y. A., Alonso, M. & Abanades, J. C. Kinetics of the CaO/Ca(OH)2 hydration/dehydration reaction for thermochemical energy storage applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 53, 12594–12601 (2014).

Zhai, H. et al. Direct observation of simultaneous immobilization of cadmium and arsenate at the brushite–fluid interface. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 3493–3502 (2018).

Boanini, E., Silingardi, F., Gazzano, M. & Bigi, A. Synthesis and hydrolysis of brushite (DCPD): the role of ionic substitution. Cryst. Growth Des. 21, 1689–1697 (2021).

Qin, L., Zhang, W., Lu, J., Stack, A. G. & Wang, L. Direct imaging of nanoscale dissolution of dicalcium phosphate dihydrate by an organic ligand: Concentration matters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 13365–13374 (2013).

Romero-Güiza, M., Astals, S., Chimenos, J., Martínez, M. & Mata-Alvarez, J. Improving anaerobic digestion of pig manure by adding in the same reactor a stabilizing agent formulated with low-grade magnesium oxide. Biomass Bioenergy 67, 243–251 (2014).

Chimenos, J. et al. Removal of ammonium and phosphates from wastewater resulting from the process of cochineal extraction using MgO-containing by-product. Water Res. 37, 1601–1607 (2003).

Courtney, C., Brison, A. & Randall, D. G. Calcium removal from stabilized human urine by air and CO2 bubbling. Water Res. 202, 117467 (2021).

Renard, F. O. et al. Sequestration of antimony on calcite observed by time-resolved nanoscale imaging. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 107–113 (2018).

Cao, X. & Harris, W. Carbonate and magnesium interactive effect on calcium phosphate precipitation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 436–442 (2008).

Lei, Y., Song, B., Saakes, M., van der Weijden, R. D. & Buisman, C. J. Interaction of calcium, phosphorus and natural organic matter in electrochemical recovery of phosphate. Water Res. 142, 10–17 (2018).

Nie, X. et al. Competition between homogeneous and heterogeneous crystallization of CaCO3 during water softening. Water Res. 250, 121061 (2024).

Sindelar, H. R., Brown, M. T. & Boyer, T. H. Effects of natural organic matter on calcium and phosphorus co-precipitation. Chemosphere 138, 218–224 (2015).

Martínez-Huitle, C. A., Rodrigo, M. A., Sirés, I. & Scialdone, O. Single and coupled electrochemical processes and reactors for the abatement of organic water pollutants: a critical review. Chem. Rev. 115, 13362–13407 (2015).

Jiang, B. et al. Electrochemical water softening technology: From fundamental research to practical application. Water Res. 250, 121077 (2024).

Lei, Y. et al. Electrochemical phosphorus removal and recovery from cheese wastewater: function of polarity reversal. ACS EST Eng. 2, 2187–2195 (2022).

Luo, J., Zhan, Z., Li, W., Zhang, X. & Lei, Y. Electrochemically assisted calcium silicate utilization for phosphate recovery. Environ. Sci. Technol. 59, 7779–7790 (2025).

Puigdomenech, I. Hydra/Medusa chemical equilibrium database and plotting software (KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 2004).

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20250604144607011, Y.L.; JCYJ20230807093405011, Y.L.), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023A1515110152, Y.L.), High-level University Special Fund (G03050K001, Y.L.), and SUSTech Start-Up Funding (Y01296128, Y.L.). The authors acknowledge the assistance of SUSTech Core Research Facilities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. and Y.L. conceived the study and designed experiments; Z.Z. and J.L. (Jingwen Lv) performed the experiments and analyzed the data, with W.L. providing assistance. J.L. (Jiyao Liu) performed the life cycle assessment. Z.Z. and Y.L. wrote the manuscript, with C.L. contributing to the manuscript revision; All authors reviewed and commented on the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Mohan Qin and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhan, Z., Lv, J., Liu, J. et al. Spatially decoupled electrochemical strategy for lime passivation prevention and sustainable phosphate recovery. Nat Commun 17, 100 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67911-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67911-1