Abstract

A topological superconductor, characterized by either a chiral order parameter or a topological surface state in proximity to bulk superconductivity, is foundational to topological quantum computing. A key open challenge is whether electron-electron interactions can tune such topological superconducting phases. Here, we provide experimental signatures of a unique topological superconducting phase in competition with electronic correlations in 10-unit-cell thick FeTexSe1-x films grown on SrTiO3 substrates. When the Te content x exceeds 0.7, we observe a topological transition marked by the emergence of a superconducting surface state. Near the FeTe limit, the system undergoes another transition where the surface state disappears, and superconductivity is suppressed. Theory suggests that electron-electron interactions in the odd-parity xy− band drives this second topological transition. The flattening and eventual decoherence of dxy-derived bands track the superconducting dome, linking correlation effects directly to superconducting coherent transport. Our work establishes many-body electronic correlations as a sensitive knob for tuning topology and superconductivity, offering a pathway to engineer new topological phases in correlated materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The interplay between electronic correlations, topology, and superconductivity is central to quantum materials research. In moiré systems, for instance, correlations facilitate integer or fractional topological states1,2,3,4, while in Cu-5 and Fe-based6 unconventional superconductors they shape superconducting domes. Yet in these strongly correlated systems, competing charge and spin orders5 often obscure the underlying mechanisms.

Intrinsic topological superconductors, which host a topological insulator (TI) phase in proximity to bulk superconductivity, provide a cleaner platform to study the interplay between correlations, topology, and superconductivity. In compounds such as FeTexSe1-x (FTS)7 and 2M-WS28, the topologically nontrivial phases are accompanied by strong electronic correlations9,10. This raises a key question: can electronic correlations themselves drive topological transitions and impact superconductivity?

We address this problem using multi-layer FTS thin films grown on SrTiO3 (STO), which combines relatively high Tc among other intrinsic topological superconductor candidates8,11,12 and built-in strong correlations. Theory predicts that the topological character of this system arises from a band inversion between the Fe dxz band and odd-parity xy− band, the latter formed by the hybridization of the Fe dxy and chalcogen pz orbitals13. The strong correlations in the xy- band can collapse the nontrivial topology13. However, this regime cannot be easily accessed in bulk FTS14,15, where an antiferromagnetic (AFM) and structural transition obscures correlation effects near the FeTe limit16,17, nor in monolayer films, where the 3D topological insulator phase and 2D topological surface state are no longer present18,19. Hence, straining a multi-layer FTS thin film by a C4-symmetric substrate provides an excellent opportunity to realize the predicted correlation-driven topological phase and correlation-tuned superconductivity.

Here we use angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) and density functional theory with embedded dynamical mean field theory (DFT+eDMFT) calculations to uncover a correlation-driven topological transition and a correlation-tuned superconducting dome in 10 unit-cell-thick (10 UC) FTS thin films. When the Te content x crosses 0.7, the first topological transition is signified by the emergence of a superconducting topological surface state (TSS). The nontrivial topology and superconductivity persist up to x = 0.95. When x reaches 1, a second topological transition occurs where the TSS disappears. Instead, a dxz/yz derived electron pocket and a strongly correlated xy− band are confirmed by polarization-dependent ARPES measurements, in agreement with our DFT+eDMFT predictions. Our ARPES and transport results also reveal an intimate relationship between the flattening of the dxy-derived bands and the enhancement in the zero-resistance superconducting transition temperature (\({T}_{c}^{0}\)). \({T}_{c}^{0}\) is rapidly quenched when the electronic correlations suppress the spectral weight of the dxy-derived bands in 10 UC FeTe. Our results establish the correlation-induced topological transition in FTS multilayer films and suggest a sensitive control of topology and superconductivity using electron-electron interactions.

Results

Superconducting topological surface state in thin-film FTS

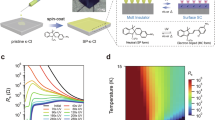

We begin our investigation by showing evidence of topological superconductivity in thin-film FTS: the opening of a superconducting gap on the TSS in a 10 UC FeTe0.93Se0.07 film grown on STO (Fig. 1). The Te content x is determined by considering both the c-axis lattice constant and the Te:Se flux ratio (Fig. S1), cross-checked by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (Supplementary Note 1; Fig. S2). Based on matrix element calculations for ARPES (Supplementary Note 2; Fig. S3; Table S1), we use s-polarized light to enhance sensitivity to the dxz orbital, and p-polarized light for the dyz, dxy, and pz orbitals. All of these orbitals contribute to the TSS which is probed by both polarizations (Fig. 1b, f). Energy distribution curves (EDCs) taken at the Fermi momentum kF of the TSS exhibit an enhanced quasiparticle peak when temperature decreases (Fig. 1c). The TSS displays Fermi crossing above ~13 K (Fig. S4), but shows a superconducting gap below this temperature, as demonstrated by the EDCs symmetrized about the Fermi level (EF) determined by polycrystalline gold (Fig. 1d). The EDC symmetrization is justified by the fact that 13 K indeed corresponds to the superconducting onset temperature (\({T}_{c}^{{\mbox{onset}}}\)) observed in electrical transport (Fig. 2c), and that superconducting gaps are particle-hole symmetric. The band structure revealed by the p-polarized light (the p-spectrum) is more complex (Fig. 1f). The quasi-flat band observed in Fig. 1f primarily originates from the superconducting dxy/dyz bulk states (Supplementary Note 3; Fig. S5)20. We extract EDCs at the momentum corresponding to the smallest gap value (Fig. 1f). We fit the symmetrized EDCs using the established Norman model21 and extract the superconducting gaps for both light polarizations (Fig. 1e). Above ~14 K, the experimental data does not allow a robust fitting as the superconducting gap vanishes (Supplementary Note 4; Fig. S6). Importantly, the gap extracted from the p-spectrum is on average 90% higher than that from the s-spectrum. This is because the bulk dxy/dyz band has a dominating contribution to the flat-band feature in the p-spectrum (Fig. 1f; Fig. S5), whereas the gap extracted from the s-spectrum reflects the superconducting order parameter on the TSS. The gap on the TSS is smaller due to proximity coupling with bulk superconductivity. Our results provide experimental signatures of topological superconductivity and superconducting proximity coupling in multilayer FTS films.

a Schematic illustration of the goal of this study: how strong electronic correlations impact band topology and superconductivity in thin-film FeTexSe1-x. b ARPES spectrum on 10 UC FeTe0.93Se0.07 measured at 8 K along \(\bar{\Gamma }-\bar{{\mbox{X}}}\) using s-polarized 6 eV photons. The black arrow indicates the momentum at which energy distribution curves (EDCs) are taken. Inset shows the schematic of the polarization-selected band structure. c Selected EDCs at various temperatures. d EDCs symmetrized around the zero energy. e Temperature dependence of the extracted superconducting gap Efit for the two polarization schemes, determined from the symmetrized EDCs in (d) and (h). Above 14 K, the quality of fits using either a single- or double-Lorentzian model becomes indistinguishable, indicating that the gap has effectively closed (Fig. S6). Within this framework, the gap extracted at 14 K using the established Norman model21 should also be indistinguishable from zero. We thus define our effective error bars based on this criterion. (f–h): Same as (b–d), but using p-polarized 6 eV photons.

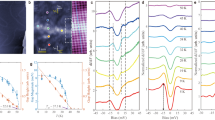

a Evolution of the ARPES spectra as a function of the Te content (x) near the \(\bar{\Gamma }\) point using p-polarized 6 eV laser. b Same as (a) but using s-polarized 6 eV photons. c Resistance-vs-temperature curves for FTS thin films. The resistance values of each curve have been vertically offset for clarity. d Fitted spectral weight (S. W.) of the lower Dirac cone as a function of the Te content. e Fitted hybridization gap (\({\Delta }_{{Hyb}}\)) between the dxy and dyz bands as a function of the Te content. The error bars in panels (d) and (e) represent the statistical uncertainty derived from the fitting procedure. f Black circles are EDCs taken at -0.025 \({\mathring{\rm A} }^{-1}\). Red curves are fits to the EDCs (see Supplementary Note 7). Red and green shaded areas represent the components corresponding to the lower and upper Dirac cones, respectively. g Inverted second derivative curves corresponding to momentum-dependent EDCs in the range between −0.065 (top) and −0.165 \({\mathring{\rm A} }^{-1}\) (bottom). Dashed lines are guides to the eye indicating the band dispersion.

Two topological transitions in FTS thin films

The most crucial observation of this work is the occurrence of two topological transitions as we tune the Te:Se ratio. The first topological transition is observed between x = 0.60 and x = 0.79, where the innermost dxz hole-like band evolves from a parabolic (Fig. 2a(i), b(i)) to a linear shape (Fig. 2a(ii), 2b(ii)). Second derivative plots of the s-spectra confirm the emergence of the TSS at x = 0.79 (Fig. S7). This first topological transition was predicted by DFT22 based on a single-particle picture and largely consistent with observations in bulk FTS materials7 despite a modified critical Te content for the topological transition. The nontrivial topology is well defined even though the inversion symmetry is broken in our films (Supplementary Note 5; Fig. S8). The topologically nontrivial phase persists as the Te content increases up to 0.95 (Fig. 2a(ii)-(v), b(ii)-(v)). Superconductivity is confirmed by electrical transport in the topologically nontrivial phase (Fig. 2c; Figs. S9, S10). As x approaches 1, the band topology undergoes another transition. The clear Dirac dispersions disappear in both the p- and s-spectra, indicating a second topological transition. A vertical streak feature appears at zero momentum of the p-spectrum (Fig. 2a(vi)); an electron pocket is observed in the s-spectrum (Fig. 2b(vi)). Since the TSS is a 2D state and has been observed at all out-of-plane momenta (kz) by previous studies on bulk FTS crystals23, the absence of the TSS for 10 UC FeTe films cannot be explained by a change in the probed kz, but rather suggests a topologically trivial phase.

The second topological transition is unexpected from a single-particle perspective (Fig. S11), but can be reconciled with a many-body picture where strong electronic correlations fundamentally modify the band topology13. The odd parity xy− band responsible for the band inversion is of Te pz and Fe dxy characters. Strong correlations in the dxy orbital are predicted to place the xy− band entirely below the dxz band along \(\Gamma -Z\), hence mitigating the anti-crossing gap between the xy− and dxz band, and driving the system topologically trivial. This theoretical picture leads to three predictions: the TSS on the a-b plane should disappear; an electron-pocket of dxz/dyz characters should emerge near the zone center (Fig. 3c(v); Supplementary Note 6); the innermost valence band should primarily consist of xy− characters and become strongly correlated with a dramatically enhanced self energy (Fig. 3c(v)). These predictions are experimentally verified. The TSS is absent in both the p- and s-spectra (Fig. 2a(vi), b(vi)). An electron pocket is clearly observed in the s-spectrum (Fig. 2b(vi)), which substantiates that it has a strong contribution from the dxz orbitals. It is more challenging to identify this electron pocket in the p-spectrum (Fig. 2a(vi)), but a more careful analysis of momentum distribution curves (MDCs) suggests its presence (Fig. S13), in agreement with the contribution from the dyz orbitals. Theoretically, in the topologically nontrivial phase the only electron pocket near \(\Gamma\) in the vicinity of EF is the xy− band above EF22,24,25. However, the observed electron pocket in the correlation-driven trivial phase is a hybridized band of both dxz/yz and xy− orbital characters (Figs. S12 and S13c). Finally, due to the xy− characters in the innermost valence band, it is most clearly resolved by the p-polarized light, and becomes much weaker using the s-polarized light. This is because neither the pz nor dxz orbital has an appreciable matrix element under the s-polarized light (Fig. S3). The large linewidth due to the strong correlation effect leads to the appearance of the vertical streak feature, which is again reproduced in our DFT+eDMFT calculations (Fig. 3c(v)). Importantly, the increasing xy− component in the valence band and its increasing strong correlations in the x = 1 limit are confirmed by the vanishing spectral weight in the lower Dirac cone as a function of increasing x, extracted by fitting the EDC at −0.025 Å−1 to the sum of two Lorentzian peaks and a featureless background (Fig. 2d; Fig. S14). The increasing correlations in the dxy orbital is confirmed by the systematically suppressed hybridization of the bulk dxy and dyz hole-like bands (Fig. 2e; Fig. S15), extracted by tracking the corresponding intensity extrema in the second derivative plots of the EDCs.

a Evolution of the ARPES spectra as a function of the Te content near the \(\bar{\Gamma }\) point and the \(\bar{M}\) point using 21.2 eV photons. b Corresponding 2D curvature plots of the raw data in (a). c Calculated spectral functions for bulk FeTe0.5Se0.5 and FeTe with different inverse spectral weights for the dxy orbital (\({Z}_{{xy}}^{-1}\)) using the density functional theory (DFT) in combination with the embedded dynamical mean field theory (eDMFT). \({Z}_{{xy}}^{-1}\) of FeTe is tuned by the Te height (Methods).

Orbital-selective electronic correlations in FTS

We obtain a full picture of the strong correlation effect in FTS thin films by comparing ARPES data and DFT+eDMFT calculations in an extended momentum and energy range (Fig. 3). This experimental data was taken using unpolarized 21.2 eV photons, allowing us to probe electronic structures from both the \(\bar{\Gamma }\) and \(\bar{M}\) points (Fig. 3a, b). The first topological transition is still observed between x = 0.60 and x = 0.79, evidenced by the change of a parabolic dxz band dispersion near \(\bar{\Gamma }\) (Fig. 3b(i)) to a Dirac-cone-like feature (Fig. 3b(iii); Fig. S16). We make three observations related to strong correlations. First, the dxy band near \(\bar{\Gamma }\) – the outermost hole-like band—becomes rapidly flattened as the Te content increases (Fig. S16). The effective mass of the dxy band increases from 29 ± 3 me to 53 ± 4 me when x goes from 0.60 to 0.93 (Supplementary Note 8; Fig. S17), where me is the free-electron mass. This strongly correlated band loses spectral weight and coherence in the FeTe limit (Supplementary Note 9; Fig. S18, S19). Second, the hybridized dxy/xz electron-like band near \(\bar{M}\) also becomes rapidly flattened as a function of the Te content, with its effective mass increased from 9 ± 2 me to 39 ± 9 me when x goes from 0.60 to 0.93 (Fig. S17). Its spectral weight disappears in the FeTe limit (Fig. 3a(vi)). This rapid disappearance reflects the combined effect of strongly correlated dxy and dxz orbitals near \(\bar{M}\), while the dxy orbital attains the highest renormalization (Fig. S20). Third, in the FeTe limit the TSS again evolves into a vertical streak feature, which reflects the strongly correlated xy− character and correlation-induced topological transition13, as was argued above. The appearance of the vertical streak feature in the ARPES data taken with 6 eV (Fig. 2a(vi)), 21.2 eV (Fig. 3a(v)), and 23.1 eV photons (Fig. S30) demonstrates that this feature is relatively kz independent, consistent with theoretical predictions based on the strongly correlated xy− band13 but contrasting the strongly kz-dependent streak feature in bulk FeTe17.

All observations of strong electronic correlations are confirmed by our first-principles DFT+eDMFT calculations (Fig. 3c). Importantly, theoretical calculations for strongly correlated materials remain inherently challenging, and achieving quantitative agreement with experiments at the meV scale is not yet expected at this stage. Here we focus on the general trend of the band structure evolution as electronic correlations are tuned without spin-orbit coupling (SOC). The more detailed comparison between calculations with and without SOC is provided in Figs. S21 and S22. The first two correlation-induced spectral features are reproduced by theory: the dxy band near \(\bar{\Gamma }\) and the dxy/xz band near \(\bar{M}\) are drastically flattened going from substrate-strained FeTe0.5Se0.5 (Fig. 3c(i), c(ii)) to substrate-strained FeTe (Fig. 3c(iii), c(iv)). For the former, the calculated effective mass increases from 15.56 me to 35.20 me. Even with the increased electronic correlations for the dxy orbital, the calculated spectral function for strained FeTe (Fig. 3c(iii), c(iv)) cannot capture the corresponding ARPES spectra for x = 1 (Fig. 3a(v), a(vi)). To further explore the impact of stronger electronic correlations, we perform calculations on FeTe with a manually increased chalcogen height of 1.85 Å. The resulting spectral function of FeTe reproduces the other key experimental observations: the dxy band near \(\bar{\Gamma }\) and the dxy/xz band near \(\bar{M}\) lose spectral weight; the dxz band at \(\bar{\Gamma }\) evolves into a vertical streak. The electron pocket derived from the dxz/dyz orbitals is also reproduced (Fig. 3c(v)), which agrees with the ARPES results using 6 eV photons (Fig. 2a(vi)). This feature is less obvious from the ARPES spectrum taken with 21.2 eV photons (Fig. 3a(v)), possibly due to a different kz or a sub-optimal energy resolution. Importantly, it is well-known that the experimental kz dependence of the FTS electronic structure is much weaker than any first-principles predictions23,26. Moreover, FTS compounds with different Te:Se ratios may not have the same inner potential for kz determination15. These complications make it challenging to determine the kz for theory-experiment comparison (Supplementary Note 12). Here we presented theoretical calculations for kz = 0, considering the successful reproduction of the spectral function in the FeTe limit (Fig. S23). In fact, the systematic kz dependent calculations show that the xy− band dispersion is flattened in the strongly correlated limit and completely submersed below the dxz/yz bands (Fig. S24), supporting the picture of the correlation-induced second topological transition.

Discussion

The phenomenology of our 10 UC FTS thin films appears fundamentally different from that of bulk FTS crystals. First, a signature of the antiferromagnetic (AFM) transition—a sharp drop in electrical resistivity near 70 K27—is not present in our FTS films for any Te content (Fig. S25). As the AFM transition is intimately linked to a C4-to-C2 structural transition28, the absence of the AFM transition likely emerges from the suppression of the structural symmetry breaking due to substrate straining (Fig. S26). The absence of the AFM phase is key to maintaining the overall electronic band structure without additional broken-symmetry-induced reconstruction, allowing a clear comparison with theoretical predictions when the electronic correlations are systematically enhanced. We note that such clarity was lacking in a recent study on bulk FTS crystals, where correlation-induced band features could not be observed at x < 0.04 and 15 K, possibly due to the competing AFM phase29. Second, absence of the AFM phase is beneficial for superconductivity. Our superconducting phase dome extends to x = 1 (Fig. 4), whereas the counterpart for bulk FTS stops at x = 0.9 ~ 0.95 due to the competing phase of AFM30,31.

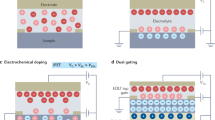

The onset transition temperature (\({T}_{c}^{{onset}}\)) and the temperature (\({T}_{c}^{0}\)) at which the resistance reaches 1% of the normal state resistance at 20 K are plotted against Te content, x. Error bars indicate one-standard-deviation (1σ) uncertainties of the fitting results. For \({T}_{c}^{{onset}}\), the uncertainties are smaller than the marker size. The blue curve shows the effective mass of the dxy band as a function of x. Near the FeTe limit, another topological transition occurs, and the system becomes trivial again. Concurrently, this region also exhibits a suppression of superconductivity.

The correlation-driven band flattening also provides a hint for the evolution of superconductivity. While the average chalcogen height has been predicted to be a key factor affecting superconductivity32, this is not the only mechanism dictating our superconducting dome. Near the optimal \({T}_{c}^{0}\) (Fig. 4), the average chalcogen height in our 10 UC FeTe0.93Se0.07 - 1.74 Å (Fig. S27)—is close to the value for bulk FeTe33,34 but much larger than the value for bulk FeTe0.5Se0.5 which exhibits the optimal Tc among other bulk FTS materials34. Moreover, 10 UC FeTe0.93Se0.07 and FeTe exhibit negligible differences in the structural parameters (Fig. S27), but \({T}_{c}^{0}\) for 10 UC FeTe is below 2 K while that for 10 UC FeTe0.93Se0.07 is 7.9 K (Fig. 4). We argue that the evolution of the superconducting dome is intimately related to the strong correlation effects of both the dxy band at \(\bar{\Gamma }\) and the dxy/xz band at \(\bar{M}\) (Fig. 3b(iii), b(iv)). Consider a generic electron-boson coupling strength \(\lambda \sim N\left({E}_{F}\right){D}^{2}\), where \(N\left({E}_{F}\right)\) is the electronic density of states at \({E}_{F}\) and \(D\) is a generalized coupling potential. When x increases from 0.60 to 0.93, the dxy-derived bands are flattened both at \(\bar{\Gamma }\) and \(\bar{M}\), contributing a rapidly increasing \(N\left({E}_{F}\right)\). Moreover, \(D\) for the case of electron-phonon coupling can also be enhanced by electronic correlations35,36,37. These factors lead to the enhancement of superconductivity. When x increases from 0.93 to 1, the superconducting onset temperature (\({T}_{c}^{{onset}}\)) stays largely unchanged while \({T}_{c}^{0}\) rapidly diminishes. The trend of \({T}_{c}^{0}\) near the FeTe limit is consistent with previous transport results38. The superconducting gap measurements at x = 0.60 and 1.00 are consistent with this trend (Figs. S28, S29), considering that the gap onset temperature corresponds to \({T}_{c}^{{onset}}.\) In the strong correlation limit, while the enhanced \(N({E}_{F})\) due to flattened bands helps with pairing, the diverging correlation effect leads to a poorly defined quasiparticle state \(\Psi \left(r,t\right)=\Psi \left(r\right)\exp (-i{E}_{B}t/\hslash )\exp (-{Im}(\Sigma )t/\hslash )\)39. When the imaginary part of the self-energy \({Im}(\Sigma )\) exceeds the electronic binding energy \({E}_{B}\) near \({E}_{F}\), the system cannot be described by traditional weak-coupling theories based on well-defined quasiparticles40. The incoherent quasiparticle states thus give rise to short-lived and incoherent pairs, leading to a suppressed \({T}_{c}^{0}\). We also note that the quasi-flat dxy band and its narrow bandwidth in 10 UC FeTe0.93Se0.07 lead to \(\Delta /{E}_{{{\rm{Fermi}}}} \sim 0.3\) and \({T}_{c}/{T}_{{{\rm{Fermi}}}} > 0.09\), where \(\Delta\), \({E}_{{{\rm{Fermi}}}}\) and \({T}_{{{\rm{Fermi}}}}\) stand for the superconducting gap, the Fermi energy, and the Fermi temperature, respectively. This makes FTS thin films in the FeTe limit potentially comparable to a broader class of flat-band superconductors such as twisted bilayer graphene41, which are in the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer Bose-Einstein Condensation (BCS-BEC) crossover. In such a regime, the discrepancy between \({T}_{c}^{{onset}}\) and \({T}_{c}^{0}\) is also expected41.

Our work demonstrates that strong correlations, superconductivity, and nontrivial topology in epitaxially grown FTS thin films are no longer separate entities. It is feasible to tune the topological superconducting phase by modulating the electron-electron interactions. This can be achieved by engineering the epitaxial strain or by changing the dielectric environment. For instance, creating an STO/FTS/STO sandwich structure42 can fully contain the Coulomb interactions within a high-dielectric-constant medium, leading to strongly modified electron-electron and electron-phonon interactions and potentially higher-temperature topological superconductivity.

Methods

Sample growth

For the ARPES measurements, 0.05% wt Nb-doped SrTiO3(100) substrates from SHINKOSHA CO., LTD were used. They were cut into 10 × 2.5 mm rectangles. After ultrasonic cleaning in Acetone and Isopropyl Alcohol, the substrates were annealed in ultra-high vacuum at ∼1000 °C for about 30 min. The FeTexSe1−x thin films were synthesized at a substrate temperature of 270 °C by co-evaporating Fe, Te, and Se in an MBE chamber. For all the FeTexSe1−x thin films, the temperature of Fe and Te were kept at 1180 °C and 265 °C, respectively. Te content was controlled by varying the Se temperature from 110 °C to 135 °C. All films were post-annealed at the growth temperature for 1 h before ARPES measurements. The growth rate and sample quality were calibrated by scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) measurements (Fig. S31).

For the transport measurements, insulating SrTiO3(100) substrates from SHINKOSHA CO., LTD were used. They were cut into 10 × 5 mm rectangles. After ultrasonic cleaning in Acetone and Isopropyl Alcohol, the substrates were etched in buffered oxide etch (BOE) for 1 min and were then annealed at 1000 °C with an O2 flow of 0.5 L/min for 3 h.

ARPES measurements

ARPES measurements were typically carried out at 20 K on the multi-resolution photoemission spectroscopy platform established at the University of Chicago43. Helium-lamp-based ARPES measurements were performed using 21.2 eV He-Iα light. Laser-based ARPES measurements were performed with a spatial resolution of 10 × 15 μm2 and a typical energy resolution of ∼4 meV using 206-nm pulses with a repetition rate of 80 MHz. In the superconducting gap measurements, the energy resolution was further optimized to ∼2.4 meV and the sample temperature was varied between 8 and 25 K.

STEM measurements

FeTexSe1−x samples with Te capping were prepared for cross-sectional STEM imaging using standard focused ion beam (FIB) lift-out procedures in a Thermo Fisher Scientific Helios 600i DualBeam FIB-SEM. A cryo-can was used during the thinning process to reduce redeposition. These FIB cross-sectional samples were stored in an inert atmosphere glovebox between sample preparation and STEM imaging. FeTexSe1−x cross sectional samples were imaged in a Thermo Fisher Scientific Themis Z aberration-corrected STEM operated at 300 kV with a convergence angle of 25.2 mrad. Scale for each atomic resolution image was calibrated with the bulk STO spacing of the sample substrate.

STM measurements

Samples were transferred from the University of Chicago to the Center for Nanoscale Materials utilizing a homebuilt vacuum suitcase. The vacuum suitcase was compatible with the Omicron VT-STM, which allowed for characterization of samples that remained in ultrahigh vacuum conditions after initial growth. Imaging was done with a standard electrochemically etched W tip. A topographic image of 0.8 UC FTS is illustrated in Fig. S21. Sample bias of +2.0 V and a tunneling current setpoint of 100 pA were used during the scanning.

DFT+eDMFT calculations

We used a fully self-consistent DFT+eDMFT implementation44,45, where the charge density, impurity level, chemical potential, self-energy, and the lattice and impurity Green’s Function were computed self-consistently. The DFT+eDMFT functional had a form of the exact Klein functional46,47, with the approximation of the correlation self-energy to be truncated to the local part of each correlated atom in the unit cell47. In addition, the less correlated chalcogen atoms and interstitial charge were treated on the DFT level. The double-counting between DFT and DMFT was subtracted exactly48. The resulting non-perturbative self-energy, which the Klein functional requires, was in practice calculated by solving the quantum impurity problem in the presence of a self-consistent electronic bath (mean-field environment). The imaginary axis self-energy was calculated using the continuous-time quantum Monte Carlo method from local properties of the Fe ion and was added to the DFT Kohn–Sham Hamiltonian47. To represent the lattice problem, we used the WIEN2k package49, which uses the full potential augmented plane wave method. To obtain the local Green’s function, required by the impurity solver, we used projection to the very localized orbitals contained within the muffin-tin spheres of correlated atoms44. This projection/embedding was done on correlated orbitals within \(\pm\) 10 eV of the Fermi-energy, which can capture spectral weight of all electrons in the solid. A Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh of 15 × 15 × 10 and the Local Density Approximation (LDA) exchange-correlation was employed at the DFT level, while at the DFT+eDMFT level we used a total of 5 million Monte Carlo steps, a Coulomb’s interaction (U) of 5.0 eV, a Hund’s coupling (JH) of 0.8 eV, and a temperature of 116 K (100 β) to model the effects of alloying tellurium and selenium on the FTS system. The values of U and J were computed using the constrained-DMFT method and had been used previously and agreed with experiments32,50. To represent 10 UC films, we modeled the FeTe0.5Se0.5 and FeTe systems in their bulk phases. FeTe0.5Se0.5 was modeled by having separate sheets of selenium and tellurium. The in-plane lattice parameters of FeTe0.5Se0.5 and FeTe were set to the experimental value of 3.88 Å. For FeTe0.5Se0.5, we optimized the Se/Te positions using eDMFT, which incorporated the effects of the electron’s entropy51,52. For FeTe, we performed calculations using both the eDMFT-optimized Te height of 1.73 Å, and a manually tuned height of 1.85 Å to investigate the strong correlation effect. We used the maximum entropy method to analytically continue the self-energy from the imaginary to the real axis. We then computed the spectral functions [A(k,ω)] shown in Fig. 3c. Calculations incorporating the spin-orbit coupling (SOC) are shown in Figs. S21, S22.

Tight-binding calculations

We adopted the eight-band effective model to simulate the band structure of multilayer FTS thin films in the topologically nontrivial regime11. The adopted onsite energy of the dxy orbital was modified to \({m}_{0}^{3}\) = 0.001 eV and the out-of-plane lattice constant was 6.27 Å.

Electrical transport measurements

10 UC FTS thin films were grown using the recipe described in the Sample growth section. A capping layer was deposited by keeping the Te flux for ∼5 min after film growth. Electrical contacts for transport measurements were established using small indium dots, which were manually applied to the samples. The average distance between adjacent dots was ∼0.5 mm. Electrical transport measurements were conducted using a Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS). An excitation current of approximately 1 μA was applied for the resistivity measurements.

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS)

For ICP-MS measurement, each sample was treated with 750 μL of hydrochloric acid (HCl, ∼ 38 wt%) and 250 μL of nitric acid (HNO3, ∼70 wt%), then left for at least three days to ensure complete dissolution. The resulting supernatant was then diluted with a 3% nitric acid solution for subsequent ICP-MS analysis. All measurements were performed using either the Thermo iCAP Q ICP-MS or Thermo iCAP RQ ICP-MS. The calibration curves demonstrated excellent linearity, with coefficients of determination (R2) of at least 0.9999 for all elements of interest, ensuring high analytical accuracy and precision.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Results can be reproduced using standard packages. Details about the implementation of DFT+eDMFT are described in the Methods section. Codes used to produce figures can be made available upon request.

References

Cai, J. et al. Signatures of fractional quantum anomalous Hall states in twisted MoTe2. Nature 622, 63–68 (2023).

Zeng, Y. et al. Thermodynamic evidence of fractional Chern insulator in moiré MoTe2. Nature 622, 69–73 (2023).

Park, H. et al. Observation of fractionally quantized anomalous Hall effect. Nature 622, 74–79 (2023).

Choi, Y. et al. Correlation-driven topological phases in magic-angle twisted bilayer graphene. Nature 589, 536–541 (2021).

Keimer, B., Kivelson, S. A., Norman, M. R., Uchida, S. & Zaanen, J. From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides. Nature 518, 179–186 (2015).

Mazin, I. I., Singh, D. J., Johannes, M. D. & Du, M. H. Unconventional superconductivity with a sign reversal in the order parameter of LaFeAsO1-xFx. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 057003 (2008).

Zhang, P. et al. Observation of topological superconductivity on the surface of an iron-based superconductor. Science 360, 182–186 (2018).

Li, Y. W. et al. Observation of topological superconductivity in a stoichiometric transition metal dichalcogenide 2M-WS2. Nat. Commun. 12, 2874 (2021).

Ma, X. et al. Correlation-corrected band topology and topological surface states in iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 106, 115114 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Evidence of strong and mode-selective electron–phonon coupling in the topological superconductor candidate 2M-WS2. Nat. Commun. 15, 6235 (2024).

Zhang, P. et al. Multiple topological states in iron-based superconductors. Nat. Phys. 15, 41–47 (2019).

Guan, S.-Y. et al. Superconducting topological surface states in the noncentrosymmetric bulk superconductor PbTaSe2. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600894 (2016).

Kim, M., Choi, S., Brito, W. H. & Kotliar, G. Orbital-selective mott transition effects and nontrivial topology of iron chalcogenide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 136504 (2024).

Huang, J. et al. Correlation-driven electronic reconstruction in FeTe1−xSex. Commun. Phys. 5, 29 (2022).

Liu, Z. K. et al. Experimental observation of incoherent-coherent crossover and orbital-dependent band renormalization in iron chalcogenide superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 92, 235138 (2015).

Liu, Z. K. et al. Measurement of coherent polarons in the strongly coupled antiferromagnetically ordered iron-chalcogenide Fe 1.02 Te using angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 037003 (2013).

Kim, Y. et al. Kondo interaction in FeTe and its potential role in the magnetic order. Nat. Commun. 14, 4145 (2023).

Shi, X. et al. FeTe1−Se monolayer films: towards the realization of high-temperature connate topological superconductivity. Sci. Bull. 62, 503–507 (2017).

Li, F. et al. Interface-enhanced high-temperature superconductivity in single-unit-cell FeTe1-xSex films on SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 91, 220503 (2015).

Jia, J. et al. Absence of BCS-BEC crossover in FeSe0.45Te0.55 superconductor. Chin. Phys. B 33, 077404 (2024).

Norman, M. R., Randeria, M., Ding, H. & Campuzano, J. C. Phenomenology of the low-energy spectral function in high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 57, R11093–R11096 (1998).

Wang, Z. et al. Topological nature of the FeSe0.5Te0.5 superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 92, 115119 (2015).

Li, Y.-F. et al. Orbital Ingredients and Persistent Dirac Surface State for the Topological Band Structure in FeTe1-xSex. Phys. Rev. X 14, 021043 (2024).

Cvetkovic, V. & Vafek, O. Space group symmetry, spin-orbit coupling, and the low-energy effective Hamiltonian for iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 88, 134510 (2013).

Wu, X., Qin, S., Liang, Y., Fan, H. & Hu, J. Topological characters in FeTe1-xSex thin films. Phys. Rev. B 93, 115129 (2016).

Lohani, H. et al. Band inversion and topology of the bulk electronic structure in FeSe0.45Te0.55. Phys. Rev. B 101, 245146 (2020).

Jiang, J. et al. Distinct in-plane resistivity anisotropy in a detwinned FeTe single crystal: Evidence for a Hund’s metal. Phys. Rev. B 88, 115130 (2013).

Li, S. et al. First-order magnetic and structural phase transitions in Fe1+ySexTe1-x. Phys. Rev. B 79, 054503 (2009).

Kim, Y. et al. Fragility of Topology under Electronic Correlations in Iron Chalcogenides. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2507.17656 (2025).

Hu, J., Liu, T. J., Qian, B. & Mao, Z. Q. Coupling of electronic and magnetic properties in Fe1+y(Te1-xSex). Phys. Rev. B 88, 094505 (2013).

Liu, T. J. et al. From (π,0) magnetic order to superconductivity with (π,π) magnetic resonance in Fe1.02Te1−xSex. Nat. Mater. 9, 718–720 (2010).

Yin, Z. P., Haule, K. & Kotliar, G. Kinetic frustration and the nature of the magnetic and paramagnetic states in iron pnictides and iron chalcogenides. Nat. Mater. 10, 932–935 (2011).

Viennois, R., Giannini, E., van der Marel, D. & Černý, R. Effect of Fe excess on structural, magnetic and superconducting properties of single-crystalline Fe1+xTe1-ySey. J. Solid State Chem. 183, 769–775 (2010).

Joseph, B. et al. Evidence of local structural inhomogeneity in FeSe1-xTex from extended x-ray absorption fine structure. Phys. Rev. B 82, 020502 (2010).

Mandal, S., Cohen, R. E. & Haule, K. Strong pressure-dependent electron-phonon coupling in FeSe. Phys. Rev. B 89, 220502 (2014).

Gerber, S. et al. Femtosecond electron-phonon lock-in by photoemission and x-ray free-electron laser. Science 357, 71–75 (2017).

Zou, Q. et al. Correlation Enhanced Electron-Phonon Coupling in FeSe/SrTiO3 at a Magic Angle. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2506.22435 (2025).

Sato, Y. et al. Molecular beam epitaxy of superconducting FeSexTe1-x thin films interfaced with magnetic topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Mater. 8, L041801 (2024).

Grimvall, G. The Electron-Phonon Interaction in Metals (North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1981).

Scalapino, D. J., Schrieffer, J. R. & Wilkins, J. W. Strong-coupling superconductivity. I. Phys. Rev. 148, 263–279 (1966).

Chen, Q., Wang, Z., Boyack, R., Yang, S. & Levin, K. When superconductivity crosses over: from BCS to BEC. Rev. Mod. Phys. 96, 025002 (2024).

Coh, S., Lee, D.-H., Louie, S. G. & Cohen, M. L. Proposal for a bulk material based on a monolayer FeSe on SrTiO3 high-temperature superconductor. Phys. Rev. B 93, 245138 (2016).

Yan, C. et al. An integrated quantum material testbed with multi-resolution photoemission spectroscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 92, 113907 (2021).

Haule, K., Yee, C.-H. & Kim, K. Dynamical mean-field theory within the full-potential methods: electronic structure of CeIrIn5, CeCoIn5, and CeRhIn5. Phys. Rev. B 81, 195107 (2010).

Haule, K. Structural predictions for correlated electron materials using the functional dynamical mean field theory approach. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 87, 041005 (2018).

Klein, A. Perturbation theory for an infinite medium of fermions. II. Phys. Rev. 121, 950–956 (1961).

Kotliar, G. et al. Electronic structure calculations with dynamical mean-field theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 865–951 (2006).

Haule, K. Exact double counting in combining the dynamical mean field theory and the density functional theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 196403 (2015).

Blaha, P. et al. WIEN2k: An Augmented Plane Wave Plus Local Orbitals Program for Calculating Crystal Properties (Techn. Universitat, 2019).

Mandal, S., Zhang, P., Ismail-Beigi, S. & Haule, K. How correlated is the FeSe/SrTiO3 system? Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 067004 (2017).

Haule, K. & Pascut, G. L. Forces for structural optimizations in correlated materials within a DFT+embedded DMFT functional approach. Phys. Rev. B 94, 195146 (2016).

Haule, K. & Birol, T. Free energy from stationary implementation of the DFT+DMFT functional. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 256402 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank Zhi-Xun Shen, Rafael Fernandes, Peter Littlewood, and David Awschalom for helpful discussions. MBE and ARPES measurements were supported by NSF via Grant No. DMR-2145373 (S.Y.). Transport measurements were done at facilities supported by NSF via Grant No. DMR-2011854 (S.Y.). Fabrication of electrical contacts for transport measurements was supported by NSF via Grant CMMI-2240489 (S.Y.). S.M. and C.L.J. acknowledge the support from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research by the Department of Defense under Award No. FA9550-23-1-0498 (S.M.) of the DEPSCoR program. S.M. and C.L.J. benefited from the Frontera supercomputer at the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) at The University of Texas at Austin, which is supported by National Science Foundation Grant No. OAC-1818253 (S.M.). S.M. also acknowledges the support from NSF OAC-2311558 (S.M.). STEM measurements were supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research under award number FA9550-20-1-0302 (P.Y.H.). STEM measurements were carried out in part in the Materials Research Laboratory Central Facilities at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. ICP-MS measurements were supported by the U.S. DOE Basic Energy Sciences under Grant No. DE-SC0023317 (C.L. and S.Y.). X.W. acknowledges support from the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFA1407300) (X.W.) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12447103) (X.W.). STM measurements performed at the Center for Nanoscale Materials, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility, was supported by the U.S. DOE, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357 (N.P.G.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L., C.Y., and S.Y. conceived and designed the experiment. H.L. and C.Y. grew the thin films and performed the ARPES experiments with assistance from Q.G., G.B., K.D.N., and Y.B. H.L., P.S., and Y.B. performed the electrical transport measurements. G.M.N. and P.Y.H. performed the STEM measurement. N.P.G., C.Y. and H.L. performed the STM measurement. C.J. and S.M. performed the DFT+eDMFT calculation. X.W. and C.-X.L. performed the tight-binding calculation. G.Y., S.C., and C.L. performed the ICP-MS measurements. H.L. and S.Y. analyzed and interpreted the experimental data. All authors participated in discussions and in writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, H., Jacobs, C.L., Yan, C. et al. A topological superconductor tuned by electronic correlations. Nat Commun 17, 1188 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67957-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67957-1