Abstract

The rapid expansion of AI models has intensified concerns over energy consumption. Analog in-memory computing with resistive memory offers a promising, energy-efficient alternative, yet its practical deployment is hindered by programming challenges and device non-idealities. Here, we propose a software-hardware co-design that trains randomly weighted resistive-memory neural networks via edge-pruning topology optimization. Software-wise, we tailor the network topology to extract high-performing sub-networks without precise weight tuning, enhancing robustness to device variations and reducing programming overhead. Hardware-wise, we harness the intrinsic stochasticity of resistive-memory electroforming to generate large-scale, low-cost random weights. Implemented on a 40 nm resistive memory chip, our co-design yields accuracy improvements of 17.3% and 19.9% on Fashion-MNIST and Spoken Digit, respectively, and a 9.8% precision-recall AUC improvement on DRIVE, while reducing energy consumption by 78.3%, 67.9%, and 99.7%. We further demonstrate broad applicability across analog memory technologies and scalability to ResNet-50 on ImageNet-100.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning, have revolutionized natural language and image processing, enabling capabilities that increasingly rival human intelligence1,2. However, the trajectory toward larger, more sophisticated models necessitates immense computational resources, raising significant concerns regarding energy consumption and environmental sustainability3,4.

Revisiting analog computing—a technique predating digital architectures-presents a compelling solution5. By harnessing emerging analog devices such as resistive memory6,7,8,9,10, analog computing processes informative analog signals directly, enhancing energy efficiency in three fundamental ways11,12,13,14,15,16,17. First, traditional digital systems physically separate memory and processing units, incurring substantial latency and energy overheads due to frequent data shuttling-the so-called von Neumann bottleneck18,19,20,21,22,23. In contrast, analog resistive memory collocates storage and processing within the same physical device24,25,26,27. Second, as complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) transistors approach physical scaling limits, the pace of Moore’s law is slowing28,29,30,31. Unlike CMOS, analog resistive memory offers high scalability and stackability12,32,33,34,35,36. Third, while standard digital memory (e.g., dynamic random access memory, DRAM) is volatile, non-volatile analog resistive memory retains data without a continuous power supply37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45.

Despite these advantages, emerging analog computing systems face persistent hurdles: programming non-idealities and high programming costs. Analog resistive memory exhibits inherent stochasticity and nonlinearity during programming46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53. Furthermore, the energy and time overheads associated with programming these devices are substantially higher than those of their digital counterparts54,55,56. Consequently, harnessing the efficiency of analog computing while mitigating these programming drawbacks remains a major open challenge for the AI hardware and electronics communities.

To address these challenges, we introduce a software-hardware co-design framework based on edge-pruning topology optimization for randomly weighted resistive memory neural networks. Inspired by clipped Hebbian-rule-based structural plasticity57, this approach emulates the brain’s postnatal development: synaptic overproduction, consolidation of functional synapses, and the elimination of redundant ones following extended learning58,59. In contrast to conventional weight optimization methods that rely on precise tuning of resistive memory conductance12,14,15,42,60,61,62, our strategy directly engineers the topology of a randomly initialized network by selectively “turning off" insignificant weights while preserving the rest. Moreover, we leverage the intrinsic electroforming stochasticity of resistive memory to generate large-scale, low-cost hardware random weights, thereby transforming programming variability into a functional asset. Building on the theory by Ramanujan et al.63-which posits that a sub-network pruned from a sufficiently large, randomly weighted network can match the accuracy of a fully optimized one-we physically reset (or set) resistive memory to prune (or reinstate) network edges. By avoiding precise programming, our approach is inherently robust to device non-idealities and eliminates the laborious conductance tuning and verification required in traditional optimization.

We validate our co-design on three representative tasks-image classification, audio classification, and image segmentation-using a hybrid analog-digital system featuring a 40 nm, 256 K resistive memory-based in-memory computing core. With identical network architectures and parameter counts, our approach achieves accuracy improvements of 17.3% and 19.9% on the Fashion-MNIST and Spoken Digit datasets, respectively, while reducing programming operations by 99.94% and 99.93% compared to hardware-in-the-loop weight optimization. The corresponding scaled inference energy per sample is reduced by 78.3% and 67.9% relative to state-of-the-art GPUs. Additionally, simulations of U-Net segmentation on the DRIVE dataset yield an area under the precision-recall curve (PR-AUC) of 0.91 and a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) AUC of 0.97 (improvements of 9.8% and 2.0% over GPUs), accompanied by a 99.7% reduction in inference energy enabled by in-memory computing and sparsity. To further demonstrate scalability, we simulate our co-design with ResNet-50 on ImageNet-100, achieving an average Top-1 accuracy of 87.6% alongside 99.3% energy savings. This work offers a universal solution for AI leveraging analog computing with emerging resistive memory (see Supplementary Figs. 13,14 and Supplementary Tables 11,12 for Llama 364,65 LoRA66 fine-tuning using edge-pruning topology optimization).

Results

Software-hardware co-design: edge-pruning topology optimization for randomly weighted resistive memory neural networks

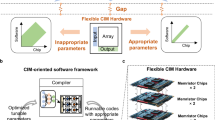

Figure 1 schematically illustrates the proposed software-hardware co-design, featuring edge-pruning topology optimization applied to a randomly weighted resistive memory neural network.

Comparison between the proposed resistive-memory-based software-hardware co-design and conventional GPU-based weight optimization across biological, algorithmic, architectural, and circuit domains. Biologically, the approach is motivated by developmental pruning in the human brain, where repeated experiences eliminate redundant synapses and preserve critical connections, in contrast to conventional schemes grounded in long-term synaptic plasticity. At the algorithm level, edge-pruning topology optimization adjusts the connectivity of a randomly weighted, overparameterized dense network to form a sparse functional sub-network, distinct from methods relying on precise weight tuning. Architecturally, a hybrid analog-digital system with an analog compute core reduces data movement between memory and processor, addressing the von Neumann bottleneck associated with conventional digital architectures. At the circuit level, resistive memory supports parallel analog matrix multiplication and physically realizes edge pruning. Intrinsic programming stochasticity generates dense random weights (illustrated by the differential-conductance heatmap and histogram), while pruning and reinstatement are implemented by resetting or setting selected differential cell pairs to low- or high-conductance states.

From a software perspective, our bio-inspired edge-pruning topology optimization emulates the human brain’s postnatal development, characterized by synaptic overproduction, the consolidation of functional synapses, and the elimination of redundant ones following extended learning (Fig. 1, upper left). In contrast to conventional weight optimization methods that fine-tune weights to minimize loss, this approach engineers the network architecture to uncover an effective sub-network without altering weight values. This methodology is grounded in a corollary to the Lottery Ticket Hypothesis63, which posits that pruned sub-networks derived from overparameterized neural networks can achieve accuracy competitive with that of the original, fully optimized networks. As depicted in the second panel of Fig. 1, the process initiates with the random initialization of the resistive memory network via electroforming stochasticity. Each edge is assigned a fixed random weight and a corresponding importance score. During the forward pass, edges with low scores in each layer-identified as redundant-are pruned to define the sub-network structure; if a neuron’s connections are heavily pruned, the neuron itself may be subsequently eliminated (see Supplementary Table 8). In the backward pass, scores are updated, and select edges are reinstated (replaced) to refine the sub-network topology and minimize training error (see “Methods” and Supplementary Table 1 for algorithmic details).

In terms of hardware implementation, the proposed optimization is realized on a hybrid analog-digital computing system comprising two main components: an analog core based on a 40 nm, 256 K resistive memory in-memory computing macro, which generates random weights, accelerates computation-intensive matrix multiplications, and executes edge pruning; and a digital core utilizing a Xilinx System-on-Chip (SoC) (see “Methods”). By collocating weight storage and computation, the analog core significantly mitigates data movement between memory and processing units, thereby offering superior energy efficiency and parallelism compared to conventional digital architectures (see Supplementary Fig. 15 for details on the fully integrated resistive memory chip). Prior to training, the resistive memory array is partitioned into positive and negative conductance sub-arrays (G+ and G−), which encode the weight matrix via differential conductance (Fig. 1, right). Initially insulating, the as-deposited cells display a narrow weight distribution centered near zero. Subsequent electroforming induces random analog weights within the G+ and G− arrays, resulting in differential-pair conductances that follow a mixture of two quasi-normal distributions. This process leverages electroforming stochasticity as an intrinsic entropy source, providing large-scale, low-cost true random weights for the overparameterized network (see Supplementary Table 3 for randomness analysis). During training, unnecessary edges are physically pruned by resetting the corresponding resistive memory differential pair, a process that ruptures the conductive filaments and zeros the conductance. Conversely, to reinstate a previously pruned but critical connection, the pair is set back to a conducting state, restoring the filament (see Methods for reset/set operations). Upon completion of training, the high-performing sub-network is frozen, yielding a conductance distribution characterized by a mixture of three quasi-normal distributions. Unlike conventional pruning strategies that primarily seek to sparsify networks to reduce computational complexity, our topology optimization introduces a training scheme specifically tailored for online learning in CIM edge systems, effectively circumventing weight optimization. This approach successfully mitigates key challenges associated with resistive memory, notably programming non-idealities and high programming costs (see Supplementary Fig. 10 for the impact of programming non-idealities).

Physical origin of resistive memory array programming stochasticity

Resistive memory cells were fabricated at the nanoscale and electroformed under identical conditions. The programmed cells were then sliced using a focused ion beam (FIB) before being examined by a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (TEM) to elucidate the microstructural origin of the programming stochasticity.

Figure 2a shows an optical photo of the resistive memory in-memory computing macro. This monolithically integrated 256 K macro adopts a crossbar structure, with resistive memory cells in each row sharing bottom electrodes and those in each column sharing top electrodes. The cells are integrated with CMOS on a 40 nm standard logic platform between the metal 4 and metal 5 layers via a back-end-of-line process, as revealed by high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) (Fig. 2b). Figure 2c highlights clear differences in cross-sectional HAADF-STEM images between pristine and electroformed cells. In the pristine cell (left), the tantalum and tantalum oxide (Ta/TaOx) resistive layer shows uniform structure (e.g., green-boxed area), whereas electroformed cells (middle and right) display brighter contrast regions (e.g., red-boxed areas) between electrodes, indicating structural variations likely due to conducting channels. To analyze composition, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) line scans were performed, revealing that brighter regions (red arrow) have a lower oxygen-to-tantalum ratio than darker regions (green arrow), confirming the presence of conducting channels46,47,67. The red line profiles of the two cells also differ markedly, aligning with the electroforming stochasticity observed in Fig. 2h, i. Complementary low-energy electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) plane scans and center-point spectra (Fig. 2d, e) of electroformed cells further demonstrate variations in oxygen-vacancy concentrations and valence between dark (Area1) and bright (Area2) regions. Losses in Area1 (25.2 and 25.1 eV) resemble the plasmon peak of insulating TaO2 (25.7 eV), while those in Area2 (24.6 and 24.4 eV) match metallic TaO (24.5 eV), indicating oxygen-vacancy migration during electroforming67,68-consistent with EDS findings. Additionally, EELS low-loss peak maps visualize the conductive channels, showing oxygen-vacancy-rich TaOx clusters spanning nearly all of Area2, with no complete channels in Area1 (Fig. 2f). The varied patterns of these channels and corresponding EELS-peak distributions (Fig. 2g) underscore the inherent stochasticity of electroforming, driven by thin-film inhomogeneity and random oxygen-ion motion, enabling low-cost, scalable random conductance for physically implementing randomly weighted neural networks.

a Optical micrograph of the 40 nm, 256 K resistive memory in-memory computing macro alongside a schematic of the crossbar array architecture. b Cross-sectional HAADF-STEM image of the resistive memory array, fabricated between Metal 4 and Metal 5 layers via back-end-of-line processing. c Cross-sectional HAADF-STEM images and EDS line profiles of electroformed resistive memory cells. Red and green arrows indicate the regions corresponding to the red-boxed (distinct structural changes) and green-boxed (no distinct changes) areas, respectively. d, e EELS plane scans (energy range: 15–35 eV, step: 0.05 eV) and corresponding center-point low-loss spectra for two electroformed resistive memory cells. Green (Area 1, insulating) and red (Area 2, conducting) regions correspond to the boxes in (c). f EELS low-loss peak maps of Area 1 and Area 2, where the color gradient from yellow to black indicates increasing oxygen-vacancy concentration. The conductive paths in the two cells exhibit marked geometric differences. g Corresponding EELS-peak distributions derived from (f), with green and red curves representing Area 1 and Area 2, respectively. h Histogram and cumulative probability of electroforming voltages for a 20 × 20 resistive memory array, obtained using a linear voltage sweep starting from 3 V with 0.05 V increments applied to each cell. i Joint distribution of conductance and standard deviation for 128 randomly selected resistive memory differential pairs following 100 pruning and reinstatement cycles. Gray and orange points denote pruned and remaining pairs, respectively. Probability densities for conductance and standard deviation are displayed in the top and right histograms. j Data retention characteristics of 128 randomly selected topology-optimized (TO)-trained resistive memory cells over 10,000 read cycles.

The intrinsic stochasticity of electroforming is harnessed to physically implement randomly weighted neural networks for the proposed edge pruning topology optimization. Figure 2h illustrates the random weight generation process using the resistive memory array. Initially, electroforming voltages are sampled from a small-scale sub-array, defined as the minimum voltage switching cell resistance from ~30 MΩ to below 300 KΩ. Based on the cumulative probability, a uniform 3.4 V pulse (10 ms width) is applied to the G+ (G−) array at 120 °C, yielding a random conductance matrix with approximately half the cells electroformed and the rest insulating (sparsity of 0.5). High-temperature forming enhances cell retention and Ron/Roff uniformity (see Supplementary Fig. 3). Finally, each cell in the G− array is electroformed to a complementary state relative to G+ (see Supplementary Table 5 for impacts of random weight distributions). During training, weights are pruned by resetting corresponding resistive memory differential pairs. As shown in Fig. 2i, analog hardware weights follow a mixture of three quasi-normal distributions, with pruned pairs exhibiting a mean conductance of ~0.07 μS and low variance (see Supplementary Figs. 5–7 and Notes for robustness studies). Figure 2j demonstrates data retention in resistive memory cells, with minimal conductance fluctuation over 10,000 read cycles (0.1 V amplitude, 2 s width), which mitigates overfitting during training as discussed later (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for 150 °C baking retention tests).

Image classification of FashionMNIST using the co-design

The co-design was evaluated on a 4-layer convolutional neural network (CNN)69—a standard vision model-for classifying the FashionMNIST dataset (simulations were also performed with ConvMixer70 on CIFAR-10 and ResNet-5071 on ImageNet100 to further demonstrate applicability; see Supplementary Figs. 11–12 and Supplementary Table 7).

Figure 3a illustrates example feature maps in garment classification using edge pruning topology optimization on the hybrid analog-digital system. The FashionMNIST dataset comprises 70,000 frontal images across 10 garment categories. Test images are down-sampled to 14 × 14, quantized to 4 bits, and input to a randomly weighted 4-layer CNN with two convolutional and two fully connected layers (see “Methods” for CNN details). Initialized with 62 K random weights (124 K resistive memory cells), the model shows differential conductance heatmaps after electroforming and topology optimization in the upper schematic. Figure 3b depicts the corresponding distributions: post-electroforming weights follow a mixture of two quasi-normal distributions with means of −27.1 μS and 27.2 μS; after optimization, half the pairs are pruned (sparsity of 0.5), adding a third distribution with a mean of −0.05 μS (see Supplementary Fig. 6 for CNN hyperparameter studies). Figure 3c visualizes 3D principal component analysis (PCA) of embedded features for the classification head before and after edge pruning topology optimization, with points color-coded by garment category. Topology optimization transforms overlapping embeddings into distinct clusters, yielding discriminative features.

a Schematic of the forward pass for garment classification. Test images are digitally pre-processed and then passed to a randomly weighted four-layer CNN physically implemented on analog resistive memory (RM). The upper panel shows measured hardware weights after electroforming and topology optimization, where pruned cells are near zero conductance (white) and retained cells are fixed at conducting states (blue and red). b Corresponding hardware weight distributions after electroforming and edge-pruning topology optimization, forming a mixture of three quasi-normal distributions with enlarged sense margins after pruning. c 3D PCA of feature embeddings after electroforming and after topology optimization, where the latter exhibits well-separated clusters. d Measured classification accuracy over 65 training epochs. Hardware topology optimization (TO) reaches 87.4% accuracy −7.7% higher than hardware weight optimization (WO) with unrestricted updates, and within 0.4% of the software WO baseline. When the WO programming count is capped at 2.6 million via a gradient threshold-comparable to TO's 2.3 million per-cell updates-its accuracy drops by 17.3%. e Experimental confusion matrix, dominated by diagonal entries. f Breakdown of programming counts for hardware-in-the-loop WO and TO. TO reduces weight updates by 99.94% relative to WO. g Inference energy for a single image. Left: the scaled hybrid system achieves a 78.3% energy reduction compared with a GPU, enabled by the software-hardware co-design. Right: TO further cut RM energy by 30.6% relative to WO due to sparsity.

As shown in Fig. 3d, the experimental edge pruning topology optimization (hardware TO) achieves a classification accuracy of 87.4% compared with 79.7% of hardware weight optimization (hardware WO) with free updates, as the latter is affected by programming noise. This corresponds to a 0.4% accuracy difference compared to the software weight optimization (software WO) baseline on GPU. The edge pruning topology optimization also exhibits higher learning efficiency, showing a 17.3% accuracy margin over weight optimization with gradient threshold under the same budget of weight updates (see Methods for weight optimization details). Additionally, hardware-in-the-loop TO improves accuracy by 0.9% over software TO on GPU, mainly by mitigating overfitting via RM read noise (see Supplementary Fig. 9 for read noise impacts). This accuracy is confirmed by the predominantly diagonal confusion matrix in Fig. 3e. Figure 3f compares training complexity: TO reduces hardware weight updates in convolutional and fully connected layers by 99.74% and 99.98% on average (for fair comparison, protocols are initialized with similar parameter sizes and terminated at comparable accuracy; see Methods and Supplementary Data 1). Figure 3g contrasts single-image inference energy between the hybrid system (~3.67 μJ) and GPU (~5.76 μJ). Scaling the 40 nm design to 5 nm (matching GPU node) reduces hybrid energy to ~1.25 μJ, yielding 78.3% savings. The right panel highlights TO’s sparsity benefit, cutting RM forward-pass energy to ~12.94 nJ versus ~18.65 nJ for WO, demonstrating 30.6% energy saving (see Supplementary Tables 4, 9–10, Supplementary Note 1, and Supplementary Data 4 for energy estimation details).

Audio classification for Spoken Digit with the co-design

In the second experiment, the co-design was applied to audio classification using a convolutional recurrent neural network (CRNN)72—a standard model for extracting spatial and temporal audio features via convolutional and recurrent layers. The Spoken Digit dataset73 was used, which includes 3000 recordings from 6 speakers sampled at 8 kHz.

Figure 4a illustrates experimental forward-pass feature maps on the hybrid analog-digital system. Spoken digits are transformed to the frequency domain and converted into 23 × 15 acoustic feature maps, then fed into a randomly weighted 5-layer CRNN with 2 convolutional layers, 1 recurrent layer, and 2 fully connected layers (see “Methods” for CRNN details). The model incorporates 68.5 K stochastic weights, realized via 137 K randomly initialized resistive memory cells. Hardware weight heatmaps after electroforming and edge pruning are shown in the upper schematic. After electroforming, weights in convolutional, recurrent, and fully connected layers follow a mixture of two quasi-normal distributions with means of −27.3 μS and 27.1 μS (Fig. 4b, left). During topology optimization, half the differential pairs (sparsity of 0.5) are reset to near-zero conductance, with remaining cells fixed, resulting in three quasi-normal distributions (Fig. 4b, right). Figure 4c visualizes 3D PCA of classification-head embeddings after electroforming and topology optimization, with points color-coded by digit category. Similar to image classification, initially overlapping embeddings form distinct clusters post-optimization, indicating discriminative features.

a Schematic of feature maps and selected weights in audio classification. Raw audio is converted to frequency-domain signals, generating 23 × 15 feature maps input to a randomly weighted five-layer CRNN physically implemented on resistive memory (RM). During optimization, pruned cells are reset to off-state (white), while remaining cells retain fixed conductance (blue and red). b Corresponding hardware weight distributions after electroforming and topology optimization. After pruning, nearly half the cells are removed, yielding a mixture of three quasi-normal distributions. c 3D PCA of feature distributions after electroforming and topology optimization, with the latter showing distinct clusters. d Measured accuracy over 60 training epochs. Hardware edge pruning topology optimization (TO) achieves 98.1% accuracy versus 90.8% for hardware weight optimization (WO) with unrestricted updates and 0.2% loss relative to the software WO baseline. Limiting WO programming to 391 thousand (matching TO's 349 thousand via gradient threshold) causes a 19.9% accuracy drop. e Experimental confusion matrix with prominent diagonal elements. f Breakdown of programming counts for hardware-in-the-loop WO and TO. The latter reduces counts by 99.93% compared to unrestricted WO. g Inference energy comparison for a single audio sample. The left panel shows that the scaled hybrid system saves 67.9% energy versus the GPU, enabled by the co-design. The right panel indicates that TO reduces RM energy by 25.9% relative to WO due to sparsity.

As shown in Fig. 4d, hardware edge pruning topology optimization achieves 98.1% accuracy versus 90.8% for hardware-in-the-loop weight optimization, affected by programming stochasticity-revealing a 0.2% difference relative to the software baseline. Like the image task, hardware topology optimization mitigates overfitting using inherent RM read noise (see Supplementary Fig. 7 for CRNN hyperparameter studies). Performance is confirmed by the confusion matrix in Fig. 4e, featuring prominent diagonals. Figure 4f shows that topology optimization reduces hardware weight updates versus unrestricted weight optimization, with average reductions of 99.64%, 99.97%, and 99.96% in convolutional, recurrent, and fully connected layers, respectively. In Fig. 4g, the energy per spoken-digit inference is ~2.02 μJ on the hybrid system (scaling to ~0.68 μJ at 5 nm) versus ~2.15 μJ on a GPU, corresponding to a 67.9% reduction. The right panel further highlights sparsity benefits, with topology optimization consuming ~4.79 nJ compared to ~6.46 nJ for weight optimization (a 25.9% reduction).

Image segmentation of DRIVE with the co-design

In addition to classification, edge pruning was evaluated on biomedical image segmentation using a U-Net74,75 for the DRIVE76 dataset. DRIVE contains 40 retinal fundus images (565 × 584) for blood vessel segmentation, including 7 images with pathological cases. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, each 584 × 565 image is first partitioned into 96 × 96 patches, which are then processed by a U-Net comprising 2 convolutional layers (input and output), 4 contracting layers (D1-D4), and 4 expansive layers (U1-U4). The network outputs segmented patches of the same size, which are concatenated to form the final segmentation. Figure 5b shows the 768 × 768 simulated weights of the D4 layer after electroforming and pruning. Initial weights are sampled from the measured conductance distribution of electroformed resistive-memory differential pairs. Following topology optimization, 50% of the weights are pruned according to a predefined sparsity of 0.5 (white pixels), while the remaining weights are drawn from the conducting-state distribution. Representative segmentation results are shown in Fig. 5c, where the simulated probability maps, binary predictions, and ground truth (from left to right) exhibit close agreement, delineating major vessels and fine capillaries (see Supplementary Fig. 8 for U-Net hyperparameter studies). Figure 5d, e compares the precision-recall (PR) and ROC curves for software and simulated WO versus simulated edge-pruning TO. The simulated TO achieves PR-AUC and ROC-AUC of 0.91 and 0.97, respectively-only 0.01 below the software WO baseline, yet yielding 9.8% and 2.0% improvements over simulated WO, owing to its robustness to programming stochasticity. The corresponding F1-score (F1) and AUC evolution during training are plotted in Fig. 5f, where simulated TO gradually converges toward the software WO baselines. The confusion matrix in Fig. 5g further validates performance: the simulated U-Net with the co-design attains 97% background and 83% vessel pixel accuracy, closely matching the software WO baseline of 98% and 80% (see Methods for PR, AUC, F1, and accuracy definitions). Figure 5h shows the estimated energy consumption of the GPU computing unit and the RM core for inferring a single image. The energy consumption for the RM core is approximately 3.5 μJ while that of the GPU computing unit is approximately 1339.5 μJ, resulting in a 99.7% energy saving enabled by the co-design.

a Illustration of the forward pass for DRIVE dataset segmentation. The 584 × 565 blood vessel image is divided into 96 × 96 patches, segmented by a U-Net with random weights sampled from conducting-state resistive memory differential pair distributions, and concatenated to form the full output. b 768 × 768 random weights of the D4 layer after electroforming and edge pruning. Pruned weights sample from off-state distributions (white), while remaining weights use conducting-state distributions (blue and red). c Segmentation inputs (left), simulated probability and binary blood vessel predictions (middle), and ground truth (right). Predictions closely match ground truth. d PR curve comparison among software weight optimization (WO), simulated WO, and simulated edge pruning topology optimization (TO). TO matches the software WO and outperforms the simulated WO. e ROC curve comparison among software WO, simulated WO, and simulated TO. f Corresponding F1 and AUC curves. g Confusion matrix for simulated pixel-wise blood vessel classification, with dominant diagonal elements. h Estimated inference energy comparison. The RM core achieves 99.7% energy reduction versus software WO on GPU, enabled by the co-design.

Discussion

In this work, a software-hardware co-designed edge pruning topology optimization for randomly weighted resistive memory neural networks was developed to tackle challenges in implementing AI via analog computing with emerging resistive memory. Hardware-wise, the intrinsic stochasticity of resistive memory electroforming is leveraged to generate large-scale, low-cost random weights and optimize network topology directly through reset operations. This approach avoids precise conductance tuning and provides a time- and energy-efficient, robust method to harness analog in-memory computing benefits for AI. Software-wise, edge pruning topology optimization utilizes true random weights from resistive memory arrays to initialize overparameterized networks and reduces programming overhead by eliminating redundant connections. Integrated with sparse weight mapping77, this method further minimizes memory footprint (see Supplementary Table 2). This co-design addresses the primary obstacles of programming stochasticity and cost in analog computing, laying the foundation for the next generation of AI hardware with high energy efficiency (see Supplementary Table 6 for edge pruning topology optimization works for other commonly used analog computing devices).

Methods

Fabrication of resistive memory chip

Under the 40 nm technology node, the fabricated resistive memory chip integrates a 512 × 512 crossbar array, with cells formed between the metal-4 and metal-5 layers using a backend-of-line process. Each cell consists of bottom and top electrodes (BE and TE) and a transition-metal-oxide dielectric layer. The BE via (60 nm diameter) is defined by photolithography and etching, filled with TaN by physical vapor deposition, and capped with a 10 nm TaN buffer layer. A 5 nm Ta layer is then deposited and oxidized to form an 8 nm TaOx dielectric layer. The TE is realized by sequential PVD deposition of 3 nm Ta and 40 nm TiN. After cell formation, the remaining interconnect metals are completed using a standard logic process. Cells in the same row share a common BE line, whereas cells in the same column share a common TE line. Following a 30-min post-anneal at 400 °C in vacuum, the 40 nm resistive memory chip exhibits excellent properties, including high yield and robust endurance (see Supplementary Figs. 1,2 for detailed device characteristics).

Hybrid analog-digital hardware system

The hybrid analog-digital hardware system (see Supplementary Fig. 4) comprises a 40 nm resistive memory chip and a Xilinx ZYNQ SoC, which integrates a field-programmable gate array (FPGA) and an ARM processor on a printed circuit board (PCB). The resistive memory chip operates in three modes under the edge-pruning topology optimization scheme: an electroform mode for generating random conductance weights, a reset mode for pruning selected weights, and a multiplication mode for vector-matrix operations. In electroform mode, dielectric breakdown is induced in the resistive memory array to form random conductance matrices: all source lines (SLs) are biased to a fixed programming voltage supplied by an eight-channel 16-bit analog-to-digital converter (DAC, DAC80508, Texas Instruments), while bit lines (BLs) are grounded and word lines (WLs) are biased by the DAC to enforce a compliance current and prevent hard breakdown. The SL voltage amplitude and pulse width tune the post-breakdown conductance distribution and sparsity. In reset mode, selected cells are returned to the off state: the target BL is biased by the DAC, the corresponding SL is grounded, and the remaining SLs are left floating. In multiplication mode, a 4-channel analog multiplexer (CD4051B, Texas Instruments) controlled by an 8-bit shift register (SN74HC595, Texas Instruments) applies DC voltages to the BLs. During each training step, the resistive memory chip is read, and the vector-matrix products, encoded in the SL currents, are converted to voltages by transimpedance amplifiers (OPA4322-Q1, Texas Instruments) and digitized by 14-bit ADCs (ADS8324, Texas Instruments). The resulting data are transferred to the Xilinx SoC for further processing. The FPGA implements the control logic for driving the resistive memory and exchanges data with the ARM processor via direct memory access to DRAM. It also accelerates selected neural network operations in hardware, such as activation and pooling.

Multi-Bit vector-matrix multiplications

To perform vector-matrix multiplication, the analog input vector is first converted into an m-bit binary vector. In this process, each input element is encoded as a binary number with m bits, where m equals 4 for CNN, 3 for CRNN, and 6 for U-Net. The analog multiplication is thus approximated by m successive multiplications using binary input vectors at different significance levels. In each step, a row is biased to a small fixed voltage (e.g., 0.1 V) if the corresponding bit is “1”, and is grounded if the bit is “0”. The resulting column currents are sequentially read out through a column multiplexer. Finally, these currents are scaled by their respective bit significance and summed in the digital domain.

Reset and set operations

Edge pruning topology optimization

The weight pruning process is physically implemented by driving the corresponding resistive-memory differential pairs into the off state via reset operations, while reinstatement is achieved by returning these cells to their conducting states via set operations. The set operation is realized by applying identical pulses with a 3.3 V amplitude and 300 ns width to the BLs of the resistive-memory array, thereby switching pruned cells back to the conducting state and reinserting them into the sub-network. The reset operation is implemented by applying identical pulses with a 2.6 V amplitude and 400 ns width to the SLs, annihilating the conductive filaments and driving the cells into the off state. Importantly, there is a large margin between the off state and the conducting state, so precise conductance programming is unnecessary.

Weight optimization

For weight optimization, identical pulses with a 1.5 V amplitude and 500 ns width are used to program the resistive-memory cells. The programming current is limited by the transistor gate voltage on the WL to control the conductance distribution. Each cell in a differential pair is tuned to its target conductance using a closed-loop write scheme78, followed by write-verify steps that ensure an approximate 10% conductance error margin.

Edge pruning topology optimization algorithm

The edge-pruning topology optimization algorithm consists of forward and backward steps. First, a randomly weighted neural network is initialized on the analog resistive-memory chip, where each weight value also serves as the score of the corresponding edge. In the forward pass, a sub-network is selected by pruning hardware weights whose scores fall below a threshold determined by a predefined sparsity (e.g., a sparsity of 0.5 corresponds to pruning 50% of the weights). The inputs are then fed through this sub-network for forward propagation and loss evaluation. In the backward pass, a general-purpose digital processor computes the gradients of the loss function to update the edge scores while keeping the weight values fixed. The scores are updated using a straight-through gradient estimator63,79:

where sij and \({\widetilde{s}}_{ij}\) denote the edge scores between the hidden nodes i and j before and after the update, respectively, η is the learning rate, \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial {I}_{j}}\) is the partial derivative of the loss L with respect to the input of node j (Ij), and wijZi is the weighted output of node i. These processes are repeated until a well-performing sub-network is selected from the randomly initialized neural network.

Threshold learning rule

To improve the energy and time efficiency during the training process, we follow Yao’s work80 and use the same threshold learning rule to reduce unnecessary programming of resistive memory.

Edge pruning topology optimization

where \(\Delta s\) is the edge-score update, and \({T}_{s}\left(t\right)\) is the dynamic threshold updated by the following rule:

where \({T}_{s}^{{{\rm{init}}}}\), \({T}_{s}^{{{\rm{end}}}}\), and α represent the pre-designed initial threshold, end threshold, and update step, respectively. When a new best accuracy is achieved, the value of t is increased by 1. This decaying threshold speeds up model convergence and is inspired by the learning-rate decay technique81.

Weight optimization

where \(\Delta w\) represents the weight update, and Tw denotes the pre-designed threshold constant used to ascertain whether a particular cell requires programming. When Tw equals zero, each cell is programmed during every training step, corresponding to weight optimization with free updates. By increasing the value of Tw, the frequency of cell programming decreases, and weight optimization with limited updates is obtained when its programming count is similar to that in the edge pruning topology optimization.

Details of the experimental neural networks

When running randomly weighted neural networks, the analog resistive-memory in-memory computing chip accelerates the most computationally intensive vector-matrix multiplications, while the remaining max-pooling, normalization, and activation operations are executed on the Xilinx SoC. Training hyperparameters are summarized in Supplementary Data 1–3.

CNN backbone

As shown in Fig. 3a, the 4-layer CNN consists of 2 convolutional (C) layers and 2 fully connected (F) layers. The C1 layer uses kernels of size 64 × 1 × 3 × 3 (out channels × in channels × width × height) and produces 64 × 12 × 12 feature maps. The C2 layer uses kernels of size 16 × 64 × 3 × 3 and generates 16 × 10 × 10 feature maps. These maps are then down-sampled by a max-pooling layer with a 2 × 2 kernel and stride 2. The resulting 16 × 5 × 5 feature maps are flattened into a 400-element vector and fed into the F1 layer. F1 has a weight matrix of size 128 × 400 and reduces the input to a 128-element vector. Finally, this vector is passed to the F2 layer with 10 × 128 weights to produce 10 output probabilities corresponding to the image labels.

CRNN backbone

Spoken digits are first transformed into the frequency domain using mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs)72, yielding cepstral feature maps suitable for recognition and classification. As shown in Fig. 4a, these 23 × 15 feature maps are then fed into a 5-layer CRNN comprising 2 convolutional layers, 1 recurrent (R) layer, and 2 fully connected layers. The C1 layer uses kernels of size 64 × 1 × 3 × 2, followed by a max-pooling layer that produces 64 × 11 × 14 feature maps. The C2 layer uses kernels of size 32 × 64 × 3 × 2, followed by a maxpooling layer that outputs 32 × 2 × 8 feature maps. These maps are then passed to the R1 layer:

where t, h(t), wih, and whh denote the time step, hidden state, input-hidden weights (128 × 32), and hidden-hidden recurrent weights (128 × 128), respectively. The time step increases as the model iterates, and when it reaches 4, the final output of the R1 layer is obtained by

Subsequently, the recurrent output with 128 elements is fed into the F1 (256 × 128) and F2 (10 × 256) layers to obtain the 10 probability outputs that determine the label of the input spoken digit.

U-Net backbone

As shown in Fig. 5a, the U-Net architecture consists of two main parts: a contracting path (down-sampling layers, D) and an expansive path (up-sampling layers, U). Each down-sampling layer applies two 3 × 3 convolutions, each followed by a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation, and a 2 × 2 max-pooling operation. This progressively extracts higher-level features from the input, enabling the network to capture critical structures and patterns. Each up-sampling layer consists of a bilinear interpolation step, concatenation with the corresponding cropped feature maps from the contracting path, and two subsequent 3 × 3 convolutions, each followed by ReLU. This design facilitates precise localization and accurate segmentation of objects within the image.

During simulations, retinal blood vessel images of size 584 × 565 pixels are first split into 26,400 overlapping 96 × 96 patches. From these, 6400 patches are randomly selected for training, and the remaining 20,000 patches are used for testing. Each patch is fed into an input convolutional layer with kernel size 32 × 1 × 3 × 3 for initial feature extraction, and the resulting feature maps are processed by four down-sampling layers (D1–D4) and four up-sampling layers (U1–U4) for vessel segmentation. The input channel numbers for D1–D4 are 32, 64, 128, and 256, respectively, and for U1–U4 are 256, 128, 64, and 32. An output convolutional layer with kernel size 2 × 32 × 1 × 1 finally maps the U4 feature maps to segmentation probability maps for each patch. The full segmented image is then reconstructed by concatenating all processed patches.

Image segmentation indicators

To demonstrate the performance of U-Net in the DRIVE image segmentation task, several indicators are evaluated, including true positive rate (TPR), false positive rate (FPR), recall, precision, F1 score (F1), and accuracy, as follows:

Here, Recall, Precision, F1, and Accuracy are widely used performance metrics for evaluating image segmentation tasks. Recall evaluates the U-Net’s ability to identify all relevant instances, Precision measures the correctness of positive predictions, F1 provides a balanced score ranging from 0 to 1, with higher values representing better classification performance, and Accuracy indicates the proportion of correct predictions made out of the total number of predictions. These metrics help assess classification performance accurately.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are provided in the main text and the Supplementary Information. Processed datasets are available in the GitHub82.

Code availability

The code supporting the findings of this study is available at the GitHub82.

References

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762 (2017).

Wolf, T. et al. Huggingface’s transformers: state-of-the-art natural language processing. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1910.03771 (2019).

Strubell, E., Ganesh, A. & McCallum, A. Energy and policy considerations for deep learning in NLP. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1906.02243 (2019).

Henderson, P. et al. Towards the systematic reporting of the energy and carbon footprints of machine learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 21, 1–43 (2020).

Copeland, J., Bowen, J., Sprevak, M. & Wilson, R. The Turing Guide (Oxford University Press, 2017).

Chua, L. Memristor-the missing circuit element. IEEE Trans. Circuit Theory 18, 507–519 (1971).

Strukov, D. B., Snider, G. S., Stewart, D. R. & Williams, R. S. The missing memristor found. Nature 453, 80–83 (2008).

Huh, W., Lee, D. & Lee, C.-H. Memristors based on 2d materials as an artificial synapse for neuromorphic electronics. Adv. Mater. 32, 2002092 (2020).

Lu, Y. & Yang, Y. Memory augmented factorization for holographic representation. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 442–443 (2023).

Zhang, W. et al. Edge learning using a fully integrated neuro-inspired memristor chip. Science 381, 1205–1211 (2023).

Chen, W.-H. et al. Cmos-integrated memristive non-volatile computing-in-memory for ai edge processors. Nat. Electron. 2, 420–428 (2019).

Joshi, V. et al. Accurate deep neural network inference using computational phase-change memory. Nat. Commun. 11, 2473 (2020).

Karunaratne, G. et al. Robust high-dimensional memory-augmented neural networks. Nat. Commun. 12, 2468 (2021).

Li, C. et al. Long short-term memory networks in memristor crossbar arrays. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 49–57 (2019).

Li, H. et al. Sapiens: A 64-kb rram-based non-volatile associative memory for one-shot learning and inference at the edge. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 68, 6637–6643 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Neural signal analysis with memristor arrays towards high-efficiency brain-machine interfaces. Nat. Commun. 11, 4234 (2020).

Milano, G. et al. In materia reservoir computing with a fully memristive architecture based on self-organizing nanowire networks. Nat. Mater. 21, 195–202 (2021).

Wang, Z. et al. Memristors with diffusive dynamics as synaptic emulators for neuromorphic computing. Nat. Mater. 16, 101–108 (2016).

Waser, R., Dittmann, R., Staikov, G. & Szot, K. Redox-based resistive switching memories-nanoionic mechanisms, prospects, and challenges. Adv. Mater. 21, 2632–2663 (2009).

Yang, J. J., Strukov, D. B. & Stewart, D. R. Memristive devices for computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 13–24 (2013).

Zidan, M. A., Strachan, J. P. & Lu, W. D. The future of electronics based on memristive systems. Nat. Electron. 1, 22–29 (2018).

Kuzum, D., Yu, S. & Wong, H. P. Synaptic electronics: materials, devices and applications. Nanotechnology 24, 382001 (2013).

Hu, M. et al. Memristor-based analog computation and neural network classification with a dot product engine. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705914 (2018).

Xi, Y. et al. In-memory learning with analog resistive switching memory: a review and perspective. Proc. IEEE 109, 14–42 (2020).

McKee, S. A. Reflections on the memory wall. In Proc. 1st Conference on Computing Frontiers 162 (ACM, 2004).

Kuroda, T. CMOS design challenges to power wall. In Proc. Digest of Papers. Microprocesses and Nanotechnology 2001. 2001 International Microprocesses and Nanotechnology Conference (IEEE Cat. No. 01EX468) 6–7 (IEEE, 2001).

Horowitz, M. 1.1 Computing’s energy problem (and what we can do about it). In Proc. International Solid-state Circuits Conference Digest Of Technical Papers (ISSCC) 10−14 (IEEE, 2014).

Theis, T. N. & Wong, H.-S. P. The end of Moore’s law: a new beginning for information technology. Comput. Sci. Eng. 19, 41–50 (2017).

Schaller, R. R. Moore’s law: past, present and future. IEEE Spectrum 34, 52–59 (1997).

Shalf, J. M. & Leland, R. Computing beyond Moore’s law. Computer 48, 14–23 (2015).

Shalf, J. The future of computing beyond Moore’s law. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 378, 20190061 (2020).

Wong, H.-S. P. et al. Phase change memory. Proc. IEEE 98, 2201–2227 (2010).

Koelmans, W. W. et al. Projected phase-change memory devices. Nat. Commun. 6, 8181 (2015).

Soni, R. et al. Giant electrode effect on tunnelling electroresistance in ferroelectric tunnel junctions. Nat. Commun. 5, 5414 (2014).

Xi, Z. et al. Giant tunnelling electroresistance in metal/ferroelectric/semiconductor tunnel junctions by engineering the Schottky barrier. Nat. Commun. 8, 15217 (2017).

Wen, Z., Li, C., Wu, D., Li, A. & Ming, N. Ferroelectric-field-effect-enhanced electroresistance in metal/ferroelectric/semiconductor tunnel junctions. Nat. Mater. 12, 617–621 (2013).

Sheridan, P. M. et al. Sparse coding with memristor networks. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 784–789 (2017).

Shi, Y. et al. Neuroinspired unsupervised learning and pruning with subquantum cbram arrays. Nat. Commun. 9, 5312 (2018).

Song, L., Zhuo, Y., Qian, X., Li, H. & Chen, Y. Graphr: accelerating graph processing using ReRAM. In Proc. IEEE Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (IEEE, 2018).

Tsai, H. et al. Inference of long-short term memory networks at software-equivalent accuracy using 2.5m analog phase change memory devices. In Proc. Symposium on VLSI Technology (IEEE, 2019).

Wan, W. et al. 33.1 a 74 TMACS/W CMOS-RRAM neurosynaptic core with dynamically reconfigurable dataflow and in-situ transposable weights for probabilistic graphical models. In Proc. International Conference on Solid-State Circuits (ISSCC) (IEEE, 2020).

Wan, W. et al. A compute-in-memory chip based on resistive random-access memory. Nature 608, 504–512 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Mixed-precision continual learning based on computational resistance random access memory. Adv. Intell. Syst. 4, 2200026 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Few-shot graph learning with robust and energy-efficient memory-augmented graph neural network (magnn) based on homogeneous computing-in-memory. In Proc. Symposium on VLSI Technology and Circuits (VLSI Technology and Circuits) 224–225 (IEEE, 2022).

Yuan, R. et al. A neuromorphic physiological signal processing system based on VO2 memristor for next-generation human-machine interface. Nat. Commun. 14, 3695 (2023).

Sun, W. et al. Understanding memristive switching via in situ characterization and device modeling. Nat. Commun. 10, 3453 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. Observation of conducting filament growth in nanoscale resistive memories. Nat. Commun. 3, 732 (2012).

Ambrogio, S. et al. Statistical fluctuations in HfOx resistive-switching memory: part i-set/reset variability. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 61, 2912–2919 (2014).

Dalgaty, T. et al. In situ learning using intrinsic memristor variability via Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling. Nat. Electron. 4, 151–161 (2021).

Burr, G. W. et al. Experimental demonstration and tolerancing of a large-scale neural network (165 000 synapses) using phase-change memory as the synaptic weight element. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 62, 3498–3507 (2015).

Wang, S. et al. Echo state graph neural networks with analogue random resistive memory arrays. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 104–113 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. An ADC-less RRAM-based computing-in-memory macro with binary CNN for efficient edge AI. In Proc. Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs (IEEE, 2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Fully memristive neural networks for pattern classification with unsupervised learning. Nat. Electron. 1, 137–145 (2018).

Chih, Y.-D. et al. 16.4 an 89TOPS/W and 16.3TOPS/mm2 all-digital SRAM-based full-precision compute-in memory macro in 22 nm for machine-learning edge applications. In Proc. International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC) Vol. 64, 252–254 (IEEE, 2021).

Wong, H.-S. P. et al. Metal–oxide RRAM. Proc. IEEE 100, 1951–1970 (2012).

Lu, Y. et al. Accelerated local training of CNNs by optimized direct feedback alignment based on stochasticity of 4 mb c-doped Ge2Sb2Te5 PCM chip in 40 nm node. In Proc. International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) (IEEE, 2020).

Marcus, C. & Westervelt, R. Stability of analog neural networks with delay. Phys. Rev. A 39, 347 (1989).

Sakai, J. How synaptic pruning shapes neural wiring during development and, possibly, in disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 16096–16099 (2020).

Sretavan, D. & Shatz, C. J. Prenatal development of individual retinogeniculate axons during the period of segregation. Nature 308, 845–848 (1984).

Hung, J.-M. et al. An 8-mb dc-current-free binary-to-8b precision reram nonvolatile computing-in-memory macro using time-space-readout with 1286.4-21.6 TOPS/W for edge-ai devices. In Proc. International Conference on Solid-State Circuits (ISSCC) (IEEE, 2022).

Prezioso, M. et al. Training and operation of an integrated neuromorphic network based on metal-oxide memristors. Nature 521, 61–64 (2015).

Tang, J. et al. Bridging biological and artificial neural networks with emerging neuromorphic devices: fundamentals, progress, and challenges. Adv. Mater. 31, 1902761 (2019).

Ramanujan, V., Wortsman, M., Kembhavi, A., Farhadi, A. & Rastegari, M. What’s hidden in a randomly weighted neural network? In Proc. Conference on Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition 11893–11902 (IEEE, 2020).

Dubey, A. et al. The llama 3 herd of models. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.16609 (2024).

Bai, J. et al. Qwen technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.16609 (2023).

Hu, E. J. et al. Lora: low-rank adaptation of large language models. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.09685 (2021).

Park, G.-S. et al. In situ observation of filamentary conducting channels in an asymmetric Ta2O5−x/TaO2−x bilayer structure. Nat. Commun. 4, 2382 (2013).

Li, C. et al. Direct observations of nanofilament evolution in switching processes in HfO2-based resistive random access memory by in situ TEM studies. Adv. Mater. 29, 1602976 (2017).

Kadam, S. S., Adamuthe, A. C. & Patil, A. B. CNN model for image classification on MNIST and fashion-MNIST dataset. J. Sci. Res. 64, 374–384 (2020).

Trockman, A. & Kolter, J. Z. Patches are all you need? Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2201.09792 (2022).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proc. Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 770-778 (IEEE, 2016).

Choi, K., Fazekas, G., Sandler, M. & Cho, K. Convolutional recurrent neural networks for music classification. In Proc. International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 2392–2396 (IEEE, 2017).

Sun, W. et al. High area efficiency (6 tops/mm 2) multimodal neuromorphic computing system implemented by 3d multifunctional RAM array. In Proc. International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 1–4 (IEEE, 2023).

Huang, H. et al. Unet 3+: A full-scale connected UNet for medical image segmentation. In Proc.International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP) 1055–1059 (IEEE, 2020).

Zhuang, J. Laddernet: multi-path networks based on U-Net for medical image segmentation. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1810.07810 (2018).

Staal, J., Abràmoff, M. D., Niemeijer, M., Viergever, M. A. & Van Ginneken, B. Ridge-based vessel segmentation in color images of the retina. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 23, 501–509 (2004).

Lin, J., Zhu, Z., Wang, Y. & Xie, Y. Learning the sparsity for RRAM: mapping and pruning sparse neural network for RRAM-based accelerator. In Proc. 24th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference 639–644 (ACM, 2019).

Yao, P. et al. Face classification using electronic synapses. Nat. Commun. 8, 15199 (2017).

Bengio, Y., Léonard, N. & Courville, A. Estimating or propagating gradients through stochastic neurons for conditional computation. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1308.3432 (2013).

Yao, P. et al. Fully hardware-implemented memristor convolutional neural network. Nature 577, 641–646 (2020).

You, K., Long, M., Jordan, M. I. & Wang, J. Learning stages: phenomenon, root cause, mechanism hypothesis, and implications. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1908.01878 (2019).

Yi, L. Code for “pruning random resistive memory for optimizing analog AI". https://github.com/lyd126/Pruning_random_resistive_memory_for_optimizing_analogue_AI (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Innovation 2030 for Science and Technology (Grant No. 2021ZD0201203), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 62374181, U2341218, 92464201, 62488101, and 62322412), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDA0330100), the Hong Kong Research Grants Council (Grant Nos. 17212923, C1009-22G, C7003-24Y, and AOE/E-101/23-N), and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (Grant No. SGDX20220530111405040).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W. and Y.L. conceived the work. Y.L., So.W., Y.Z., Sh.W., B.W., W.Z., and Y.H. contributed to the design and development of the models, software, and hardware experiments. Y.L., So.W., Y.Z., N.L., B.C., X.C., and Z.W. interpreted, analyzed, and presented the experimental results. Y.L., So.W., and Z.W. wrote the manuscript. Z.W., X.X., and D.S. supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Wang, S., Zhao, Y. et al. Pruning random resistive memory for optimizing analog AI. Nat Commun 17, 1190 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67960-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67960-6