Abstract

Sleep decoding is key to revealing sleep architecture and its links to health, yet prevailing deep-learning models rely on supervised, task-specific designs and dual encoders that isolate time-domain and frequency-domain information, limiting generalizability and scalability. We introduce SleepGPT for sleep decoding, a time-frequency foundation model based on generative pretrained transformer, developed using multi-pretext pretraining strategy on 86,335 hours of polysomnography (PSG) from 8,377 subjects. SleepGPT includes a channel-adaptive mechanism for variable channel configurations and a unified time-frequency fusion module that enables deep cross-domain interaction. Evaluations across diverse PSG datasets demonstrate that SleepGPT sets a new benchmark for sleep decoding tasks, achieving superior performance in sleep staging, sleep-related pathology classification, sleep data generation, and sleep spindle detection. Moreover, it reveals channel- and stage-specific physiological patterns underlying sleep decoding. In sum, SleepGPT is an all-in-one method with exceptional generalizability and scalability, offering transformative potential in addressing sleep decoding challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sleep is a critical physiological process essential for human health, influencing a diverse array of cognitive, emotional, and physical functions1,2. Decoding of sleep patterns is fundamental for elucidating its role in health maintenance and the management of sleep-related disorders3,4,5. Traditional methods of sleep decoding, such as the manual scoring of polysomnography (PSG) recordings, are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and prone to inter-rater variability. Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have demonstrated significant potential to automate these processes6,7,8. Sleep data annotation is expensive and has emerged as an important bottleneck to progress in sleep research. While recent advances like U-Sleep7 have largely alleviated the need for additional annotations in sleep staging, other tasks such as spindle detection and disorder classification still face limited annotated data. Recently, self-supervised learning has demonstrated the potential to leverage unannotated data to pretrain foundation models, thereby significantly reducing the demand for task-specific annotations9,10,11,12. Owing to their ability to leverage large-scale unlabeled data while minimizing reliance on annotated datasets, foundation models have been successfully developed and used in biomedical research and genomics13,14,15,16,17,18,19. Several self-supervised or pre-trained models for EEG and sleep staging have already been proposed. However, to the best of our knowledge, a multi-task foundation model specifically designed for sleep decoding has not yet been reported.

The development and application of foundation models in sleep research faces three major challenges. First, the lack of self-supervised methods for pretraining poses a significant challenge in developing foundation models for sleep decoding. While different self-supervised pretraining approaches significantly influence model performance16,17, the strategies for scaling these methods to extract robust and diverse sleep representations remain unclear. Second, variability in channel configurations and acquisition protocols across PSG datasets creates significant barriers to model generalization. Although fixed-channel dependencies have historically limited many models in integrating heterogeneous PSG recordings collected using different equipment and setups, recent advances in sleep staging, such as U-Sleep and GSSC20, have demonstrated strong flexibility and can operate with a wide range of channel configurations without strict fixed-channel requirements21. Nevertheless, beyond sleep staging, many existing approaches still rely on fixed-channel assumptions, which continue to restrict large-scale multi-dataset training and adaptation. Finally, integrating time-domain and frequency-domain features remains a significant challenge in sleep decoding. Both domains are essential for a comprehensive understanding of sleep signals22, yet current fusion methods often rely on dual-encoder architectures that process them in isolation6,23, failing to capture their interdependencies. As a result, the potential to leverage complementary features for a more robust, scalable and integrated time-frequency analysis remains limited.

In this study, we present Sleep Generative Pretrained Transformer (SleepGPT), an open-weight foundation model pretrained and evaluated on 86,335 h of PSG recordings from 8377 subjects, specifically designed to these three challenges.

First, SleepGPT adopts a multi-pretext task approach for pretraining, incorporating a time-frequency contrastive learning24,25 approach to align features across domains, a time-frequency matching approach with hard negative pairs to accelerate this alignment, and a masked autoencoder26,27 approach to enhance contextual understanding. The model is pretrained on 59,267 h of PSG recordings from 5132 subjects, representing the largest self-supervised pretraining effort in sleep decoding to date. By leveraging this approach, SleepGPT effectively generalizes across diverse datasets and captures the complex, multifaceted nature of sleep signals. While it is true that many supervised models have been trained on even larger PSG datasets7, the focus of this work is on self-supervised learning, which enables SleepGPT to effectively learn from unannotated data and generalize across a range of sleep tasks.

Second, to overcome the variability in PSG channel configurations across datasets, SleepGPT integrates a channel-adaptive mechanism through channel-wise convolution and masked multi-head self-attention within its Transformer framework28. These innovations enable flexible adaptation to diverse channel combinations, allowing the model to effectively integrate eight key PSG channels, including six electroencephalogram (EEG) channels (C3, C4, F3, FPz, O1, and Pz), one electromyogram (EMG) channel, and one electrooculogram (EOG) channel. This approach not only facilitates the extraction of intrinsic signal features but also enhances the model’s ability to learn inter-channel relationships and generalize across diverse datasets.

Third, to integrate time-domain and frequency-domain features for a deeper understanding of PSG recordings, we develop a unified time-frequency fusion mechanism inspired by the mixture-of-modality-experts Transformer framework29. This time-frequency fusion mechanism leverages a shared attention matrix to jointly align and encode features from both domains, while replacing traditional feed-forward layers with domain-selecting perceptrons that dynamically adapt to emphasize domain-specific characteristics. Unlike dual-encoder approaches that process each domain independently, our unified architecture minimizes redundancy, improves computational efficiency, and uncovers intricate cross-domain relationships, offering a robust and scalable solution for comprehensive sleep decoding.

To systematically evaluate the effectiveness of SleepGPT as a foundational model for sleep decoding in real-world scenarios, we evaluated its performance across four primary tasks: sleep staging, sleep-related pathology classification, sleep data generation, and sleep spindle detection. The evaluation, including fine-tuning and testing, was conducted on publicly available and widely adopted PSG datasets. Compared to other supervised learning methods, SleepGPT achieves state-of-the-art (SOTA) performance in sleep staging, either surpassing or matching the best-performing models. In comparison with other unsupervised methods, SleepGPT also demonstrates SOTA performance even with minimal labeled data, highlighting its versatility and robustness. Furthermore, SleepGPT shows strong adaptability to wearable single-channel data, highlighting its potential for deployment in resource-limited and home-based sleep monitoring scenarios. By training on multiple channels without direct mixing, the proposed model enables detailed analysis of each channel’s contribution to sleep staging. Notably, it identifies that the F3 and Pz channels consistently exhibit higher importance and deliver superior sleep staging performance across diverse PSG datasets. Additionally, SleepGPT leverages entire-night PSG recordings to classify sleep-related pathologies. The model uses the EEG, EOG, and EMG signals to effectively determine disease types without requiring additional derivations or diagnostic information from patients. Furthermore, we analyzed the contribution of sleep stages to disease classification, providing insights into the underlying mechanisms of sleep-related pathologies. SleepGPT exhibits exceptional performance in generating sleep data, with its effectiveness validated through randomly masked scenarios designed to simulate noise artifacts commonly observed during PSG data collection. Moreover, the findings indicate that leveraging the model’s generative capabilities to expand the dataset substantially enhances the accuracy and reliability of sleep staging. Lastly, the model demonstrates exceptional performance in sleep spindle detection, significantly achieving high recall–an essential metric for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment in clinical applications. In sum, SleepGPT demonstrates its potential to assist clinical diagnostics while advancing deep learning research in the field of sleep decoding.

Results

Overview of SleepGPT

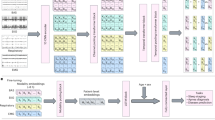

The input to SleepGPT consists of time-frequency PSG signals derived from a single epoch of multi-channel PSG recordings, initially represented in the time domain and spanning 0 to 30 s (Supplementary Note 1). Each channel in this multi-channel epoch undergoes an independent short-time Fourier transform to produce a spectrogram. Rather than interpreting the spectrogram as a combined time-frequency map, each time window is treated separately to allow granular analysis of short-term frequency dynamics (Methods). The resulting frequency-domain signals are then integrated with the original time-domain signals, forming time-frequency, multi-channel signals. These signals are mapped into high-dimensional embeddings, which are subsequently processed within a unified time-frequency (UTF) transformer framework, thereby providing rich, time-frequency and multi-channel embeddings for both pretraining and downstream tasks. SleepGPT training proceeds in two stages: an initial pretraining phase on large-scale PSG datasets to capture general-purpose representations, followed by fine-tuning on smaller PSG datasets optimized for specific downstream tasks (Fig. 1a).

a The workflow of SleepGPT. The training process involves two stages: pretraining and fine-tuning. During pretraining, the model is trained on large-scale, time-frequency PSG signals using multi-pretext tasks to learn robust and generalized representations. In the fine-tuning stage, the pretrained model parameters are adapted to specific downstream applications using labelled datasets. b Overview of the input embedding and UTF transformer process in SleepGPT. Time-frequency signals, including time-domain signals and frequency-domain signals, are processed per channel via channel-wise convolution, producing time-domain patch tokens and frequency-domain patch tokens. Missing data is masked. Embeddings for each domain are generated by concatenating patch tokens across channels, resulting in time-domain embeddings and frequency-domain embeddings. These embeddings are then concatenated to form joint embeddings, which serve as the input to the UTF transformer block. The core component of SleepGPT contains M stacked transformer blocks with specialized masked multi-head self-attention block and domain selecting perceptron. U-PCN denotes the unified perceptron, while T-PCN and F-PCN represent the time-domain and frequency-domain perceptrons, respectively. The transformer outputs epoch embeddings for pretraining and downstream usage. c SleepGPT can perform a range of tasks, including sleep staging, sleep-related pathology classification, sleep data generation, and sleep spindle detection.

Building on this time-frequency representation, channel-wise convolutions are first applied to time-domain and frequency-domain signals, segmenting the input into smaller patches and mapping them to high-dimensional features, referred to as patch tokens (Fig. 1). A masking strategy on patch tokens facilitates flexible adaptation to diverse channel configurations, resulting in robust and unified representations. The core of SleepGPT is the UTF transformer block, which integrates domain-selecting perceptrons. This module dynamically selects or fuses embeddings from both time-domain and frequency-domain, capturing complementary features for robust representations by leveraging the time-domain and frequency-domain characteristics of PSG signals (Fig. 1b).

To pretrain robust features from multi-channel PSG signals, we employed the time-frequency contrastive learning approach with hard sample pairs to predict matching pairs (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2) and applied the masked autoencoder approach to reconstruct original signals in time-domain and frequency-domain (Supplementary Fig. 3).For downstream tasks, SleepGPT’s outputs are adapted based on task requirements, either by aggregating features across adjacent epochs or directly using the embeddings. We evaluated SleepGPT on four downstream tasks to assess its performance (Fig. 1c).

Overview of PSG datasets

In this study, databases refer to collections of PSG recordings derived from independent clinical or basic research studies, often conducted over multiple rounds of data collection or sub-cohort divisions. Within each database, PSG recordings are categorized into datasets based on study-specific criteria, such as collection protocols, participant cohorts, or experimental conditions (Methods).

SleepGPT was pretrained and evaluated on 14 PSG datasets sourced from seven PSG databases, comprising 86,335 h of recordings from 8377 subjects (Supplementary Table 1).

For pretraining, we utilized four PSG datasets sourced from three PSG databases, comprising 7650 PSG recordings collected from 5132 subjects, spanning a total of 59,267 h (Supplementary Table 2). These datasets include the PhysioNet2018-test dataset from the PhysioNet/Computing in Cardiology Challenge 2018 (PhysioNet2018) database30; the SHHS-1 (Visit 1) and SHHS-2 (Visit 2) datasets from the Sleep Heart Health Study (SHHS) database31,32; and the SleepEEGfMRI dataset from the SleepEEGfMRI database33,34.

For evaluation in downstream tasks, we employed 11 PSG datasets sourced from six PSG databases to fine-tune and test our model, consisting of 7325 PSG recordings from 7250 unique subjects, collectively totaling 57,053 hours (Supplementary Table 3). These datasets include the CAP dataset from the CAP database35, five subsets (MASS-SS1 to SS5) from the Montreal Archive of Sleep Studies (MASS) database36; the PhysioNet2018-training dataset from the PhysioNet2018 database; the SHHS-1; two versions from the Sleep-EDF database37, which includes the 2013 version (SleepEDF-20) and the 2018 version (SleepEDF-78); and the UMindSleep (UMS) dataset from UMS database38.

More details on dataset composition and usage can be found in Methods section and Supplementary Tables 1–4.

SleepGPT surpasses SOTA supervised learning methods in sleep staging

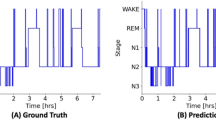

Sleep staging is a fundamental process in sleep research and clinical practice, serving as the cornerstone for diagnosing sleep disorders, evaluating sleep quality, and understanding neurological and physiological functions during sleep. Sleep staging generally involves segmenting PSG recordings into 30-second intervals, and classifying each interval into a specific physiological stage: wakefulness (W), non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep stages 1 (N1), 2 (N2), and 3 (N3), rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, or UNKNOWN, according to the American Association of Sleep Medicine (AASM) guidelines39 (Supplementary Table 5). In the context of sleep staging, an epoch refers to a standard 30-second interval of PSG recordings used for classification. We conducted a comprehensive evaluation of our model, SleepGPT, by benchmarking it against SOTA supervised learning methods, including Cross-modal SleepTransformer40 and SleepXViT41, as well as other strong baselines6,8,42,43,44,45 using nine datasets: MASS-SS1 to SS5, PhysioNet2018-training, SHHS-1, SleepEDF-20 and SleepEDF-78 (Supplementary Table 6). Following the evaluation scheme adopted by these SOTA methods, the MASS-SS1 to SS5 datasets were combined and treated as a single dataset for fine-tuning and testing. Both overall metrics (accuracy (ACC), macro F1 score (MF1)46, and Cohen’s kappa score (Kappa)47) and per-class F1 score were adopted for the evaluation (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 7). Visualization of fine-tuned SleepGPT embeddings are presented by uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP)48 (Fig. 2b).

a Comparisons with other supervised learning methods are presented using three heat maps, which depict ACC, MF1, and Kappa from left to right. Each heat map visualizes the performance ranking of models across multiple datasets using circles, with larger circles indicating higher rankings for the respective model. The datasets evaluate in this task include MASS-SS1 to SS5, PhysioNet2018-training, SHHS-1, SleepEDF-20, and SleepEDF-78. Notably, the MASS-SS1 to SS5 datasets are combined and treated as a single dataset for the analysis. b UMAP of SleepGPT embeddings using supervised evaluation scheme. c Comparison with other advanced unsupervised learning methods (SleepEDF-20). Each method is evaluated on two metrics (ACC and MF1). Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) across five independent runs (n = 5). d UMAP of SleepGPT embeddings using unsupervised evaluation scheme. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

SleepGPT outperformed or matched SOTA supervised learning methods across five benchmark datasets for sleep staging (Fig. 2a). These results underscore SleepGPT’s robust generalizability, demonstrating consistent performance on both small and large datasets, irrespective of channel configurations. Notably, on the largest dataset SHHS-1, SleepGPT achieved an ACC of 89.1%, a MF1 of 82.4%, and a Kappa of 0.845. For key sleep stages such as N2 and REM, the model achieved F1 scores of 90.2% and 91.6%, respectively, reflecting its capacity to precisely classify stages critical to understanding sleep architecture. To evaluate the model’s adaptability to diverse channel configurations and its downstream task performance, we implemented two fine-tuning strategies in the MASS-SS1 to SS5 datasets. The first employed fixed channel configurations across all datasets, while the second adapted to the specific channel settings of each dataset. The adaptive strategy yielded superior results, achieving an MF1 of 85.1%, demonstrating the model’s ability to flexibly accommodate heterogeneous channel setups, leading to improved classification balance across sleep stages. Since sleep staging involves temporal dependencies, where the classification of an epoch is influenced by surrounding epochs, we performed ablation studies to assess the contribution of contextual encoders. These studies highlight the critical role of appropriately designed encoders in capturing sequential patterns, thereby reinforcing the model’s ability to deliver accurate predictions across continuous sleep epochs (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Table 8).

SleepGPT surpasses SOTA unsupervised learning methods in sleep staging

To evaluate the effectiveness of our method in sleep staging within an unsupervised learning framework, we conducted a comprehensive comparison against SOTA unsupervised learning methods, including: 1) Neuro-Bert49, leveraging the masked autoencoder approach; 2) ContraWR50, leveraging the contrastive learning approach optimized for minimal labeled data; 3) MulEEG51, employing the dual-encoder architecture to process time-frequency PSG signals in isolation; and 4) TS-TCC52, an established framework for time-series representation learning. Each method corresponds to a specific evaluation scheme. Each experiment was conducted with five random seeds, assessed by mean and standard deviation of the three overall metrics (Supplementary Tables 9, 10). We also compared SleepGPT’s performance against other advanced methods9,53,54,55,56,57 under the evaluation scheme adopted by TS-TCC (Fig. 2c) and visualized embeddings learned by SleepGPT using UMAP (Fig. 2d).

Against Neuro-Bert, which utilized the masked autoencoder approach and the transformer backbone, SleepGPT showed a notable performance increase, with 0.9 p.p. in ACC and 2.7 p.p. in MF1. Meanwhile, SleepGPT also got an improvement of 2.3 p.p. for ACC and 4.2 p.p. for MF1 against MAE26, a prominent transformer model in computer vision using the masked autoencoder approach. SleepGPT can also consistently perform well in case the amount of labeled data available is not sufficient. Our model surpassed ContraWR by 0.4 p.p. in ACC with only 5.0% labeled data. When testing on MulEEG with 20 subjects under cross-validation evaluation scheme, SleepGPT improved ACC and MF1 by 6.3 p.p. and 8.8 p.p., respectively. This highlights the superiority of our proposed transformer backbone with a unified fusion block over dual-encoder models using unsupervised methods. In addition, our model outperformed TS-TCC, enhancing ACC by 1.6 p.p. and boosting MF1 by 7.1 p.p. These results confirm that our hybrid pretraining method significantly enhanced representations.

SleepGPT performing on wearable data

To evaluate the adaptability of SleepGPT to wearable data, we conducted experiments on the UMS dataset, which provides single-channel EEG from a wearable forehead recorder alongside PSG. Following previous research38, we grouped N1 and N2 as light sleep and treated N3 as deep sleep for a 4-class setting. SleepGPT achieved an ACC of 82.1% (MF1: 78.0%, Kappa: 0.694), and incorporating SpO2 further improved performance to 82.6% ACC (MF1: 78.6%, Kappa: 0.701) (Supplementary Table 11).

In addition, we evaluated SleepGPT on the same dataset under the original 5-stage classification setting (Wake, N1, N2, N3, REM). SleepGPT with SpO2 achieved an ACC of 76.6% (MF1: 67.5%, Kappa: 0.653) with per-class F1 scores of 72.5% (Wake), 28.2% (N1), 85.2% (N2), 75.2% (N3), and 76.1% (REM) (Supplementary Table 12). These results show that SleepGPT is capable of maintaining strong performance even when handling the full 5-class staging with single-channel input, highlighting its ability to generalize beyond standard PSG configurations and its potential applicability in wearable-device scenarios.

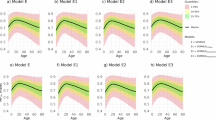

The F3 and Pz channels play critical roles in sleep staging

To explore the contribution of different channels on sleep staging, we assessed the channel weights during sleep staging (Fig. 3a). Four datasets (MASS-SS1 to SS3 and MASS-SS5) were selected based on channel availability and a heatmap was employed to visualize how different sleep stages and channels interacted. The heatmap revealed that the Pz channel consistently had more influence across all sleep stages compared to other channels, while the F3 channel showed a secondary level of influence, except in MASS-SS2 dataset.

Channel importance and performance metrics across four MASS datasets (MASS-SS1 to SS3, and MASS-SS5), with channels displayed in the order of their actual input sequence. a Heatmap showing the weights of different channels for various sleep stages. Blank areas indicate channels not included in specific datasets. b Per-class F1 scores for the F3 and Pz channels across four datasets, displayed as the average of 10 independent experiments conducted on each dataset with maximum values highlighted. c Overall performance metrics aggregated across four datasets. The left panel shows averaged per-class F1 scores, and the right panel presents mean ACC, MF1, and Kappa. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We further compared per-class F1 scores across the four datasets by fine-tuning using either the F3 or Pz channels (Fig. 3b). The F3 channel was specifically chosen due to its significant impact on sleep staging, its inclusion in AASM guidelines, and its common use in wearable devices as a frontopolar EEG electrode. Across all four datasets, SleepGPT utilizing the Pz channel consistently achieved higher per-class F1 scores in the W and N1 stages compared to its performance with the F3 channel. For both the MASS-SS1 and MASS-SS2 datasets, SleepGPT leveraging the Pz channel demonstrated notable improvements across nearly all sleep stages, with particularly strong contributions to the detection of N3 and REM stages, which are critical for deep sleep and dreaming phases.

Overall results were calculated by averaging confusion matrices across four datasets (Fig. 3c). SleepGPT with the Pz channel showed substantial improvements in average F1 scores across W, N1, N2, N3, and REM stages (8.8 p.p., 15.6 p.p., 2.2 p.p., 3.7 p.p., and 3.9 p.p., respectively). It also achieved enhanced overall metrics, increasing ACC by 6.8 p.p. (P < 0.0001), MF1 by 3.7 p.p. (P < 0.0001), and Kappa by 0.059 (P < 0.0001). These findings suggest that the Pz channel may offer superior utility for sleep monitoring, potentially guiding the design of more efficient and accurate single-channel wearable devices for continuous, non-invasive sleep assessment and personalized health monitoring.

Sleep-related pathology classification and the impact of sleep stages

Sleep-related pathology impact individuals globally and are associated with serious health issues. When wake/sleep complaints remain undiagnosed and untreated, they impose a substantial burden, both personally, in terms of suffering, and societally, in terms of economic consequences58. Physicians diagnose sleep-related diseases by analyzing overnight sleep signals, a process that is both time-consuming and increasingly challenging given the rising prevalence of sleep disorders. Comprehensive overnight sleep monitoring is essential for accurate detection, yet existing methods rarely leverage overnight signals for automated sleep-related disease classification. SleepGPT addresses this gap by efficiently utilizing overnight PSG recordings for classification. We evaluated its performance on two datasets: the SHHS-1 dataset, performing binary classification between healthy controls (HC) and patients with severe sleep apnea (SSA) and the CAP dataset, focusing on three-class classification among individuals with nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy (NFLE), REM behavior disorder (RBD), and HC (Methods and Supplementary Note 3).

We found that SleepGPT effectively classifies patients with SSA and HC without relying on electrocardiography or respiratory channels, achieving an average receiver operating characteristic (ROC) area under the curve (AUC) of 0.847 ± 0.002 (Fig. 4a). Evaluation metrics across test results, including ACC, F1 score, precision, and recall, demonstrate robust performance in classifying SSA and HC (Fig. 4b). The confusion matrix results further highlight reliable classification between these two groups (Fig. 4c). In the three-class classification task, SleepGPT demonstrated robust pathology detection capabilities, achieving an average ROC AUC of 0.906 ± 0.010 for NFLE and 0.942 ± 0.012 for RBD (Fig. 4d). Notably, the model exhibited exceptional recall for NFLE, with an average value of 0.915 (Fig. 4e, f). Furthermore, we analyzed the contributions of different sleep stages to the classification of these sleep-related pathologies by comparing the results of using features from all sleep stages versus excluding features from a specific sleep stage. For binary classification between SSA and HC, all sleep stages except the N3 and REM stage showed significant importance: Wake stage (P < 0.0001), N1 stage (P < 0.0001) and N2 stage (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4g). For three-class classification of NFLE, RBD, and HC, features from the N1 stage appeared to interfere with model performance (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4h, i), indicating potential challenges in leveraging this stage for precise pathology classification.

a–c SSA classification: binary classification between SSA and HC;d,f NFLE and RBD classification: three-class classification between NFLE, RBD, and HC. Results are derived from 10 independent experiments. ROC curves with corresponding AUC ± s.d. for SSA classification (a) and NFLE and RBD classification (d). ACC, F1 score, precision, and recall for SSA classification (b) and NFLE and RBD classification (e). Mean normalized confusion matrices for SSA classification (c) and NFLE and RBD classification (f). The color scale represents the normalized classification accuracy (proportion), with darker colors indicating higher values. Influence of sleep stages on sleep-related pathology classification: SSA (g), NFLE (h), and RBD (i). Each panel compares results obtained when a specific sleep stage is excluded versus when all stages are included. Results are shown as mean ± s.d. across ten independent experiments (n = 10). Statistical significance of performance differences for each stage was evaluated using a two-tailed t-test, with P values indicated as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. Exact P values for SSA classification are reported for significant comparisons: without stage Wake (P = 7.79 × 1 × 10−5), without N1 (P = 4.43 × 1 × 10−5), and without N2 (P = 3.35 × 1 × 10−4). Exact P values for NFLE and RBD classification are reported for significant comparisons: without stage N1 (P = 0.0427) and without stage N1 (P = 0.0414), respectively. Each box plot shows the median (center line), 25th-75th percentiles (box limits), whiskers extending to 1.5 × the interquartile range (IQR), and individual points representing outliers. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Generative performance across channels and mask ratios

During full-night sleep monitoring, various artifacts can occur, potentially affecting data quality. Excessive nocturnal sweating is a common issue in apnea patients59 and often introduces low-frequency artifacts that interfere with signal integrity60. These sweating-induced artifacts can degrade the accuracy of sleep staging and related analyses. To address this challenge, we incorporated a sleep data generation module into SleepGPT, enabling the generation of multi-channel PSG signals for denoising purposes. To evaluate the model’s generative capabilities, we tested its performance in reconstructing missing PSG signals, simulating scenarios of artifact-induced data corruption.

The reconstruction results across all eight channels, obtained using a randomly masked strategy, demonstrate that SleepGPT effectively reconstructs missing multi-channel PSG signals at the epoch level (30 seconds) (Supplementary Fig. 4). By leveraging features from other channels, the model showcases its robust capability to generate high-quality PSG signals, enhancing the overall quality and accuracy of sleep analysis.

To quantitatively evaluate SleepGPT’s reconstruction performance, we assessed its ability to reconstruct 30-second epochs of PSG signals across multiple downstream task datasets, including MASS-SS1 to SS5, PhysioNet2018-training, SHHS-1, and SleepEDF-78 (which contains SleepEDF-20), using Normalized Mean Squared Error (NMSE) as the evaluation metric (Fig. 5a). The mask strategy and mask ratio used are identical as those specified in the pretraining configuration (Methods). NMSE is a statistical measure used to quantify the difference between predicted values generated by a model and the actual values observed from the environment that the model aims to predict. It is a normalized version of the Mean Squared Error, which is commonly used in the masked autoencoder approach26,61, providing a dimensionless quantity that can be more easily compared across different channels.

a, b Datasets include MASS-SS1 to SS5, PhysioNet2018-training (denoted as PC2018), SHHS-1, and SleepEDF-78. a Generative performance across different PSG channels, quantified using NMSE across all downstream task datasets. Each violin plot shows the distribution of NMSE values computed per recording (one value per overnight PSG recording) for each channel within a dataset. The white dot represents the median, the black bar indicates the interquartile range (IQR), and the violin shape depicts the kernel density estimate of the data distribution. Each box plot shows the median (center line), 25th-75th percentiles (box limits), whiskers extending to 1.5 × the interquartile range (IQR), and individual points representing outliers. The number of recordings (n) corresponds to the number of independent PSG recordings in each dataset (SHHS: n = 1,716; MASS-SS1: n = 53; MASS-SS2: n = 19; MASS-SS3: n = 62; MASS-SS4: n = 40; MASS-SS5: n = 26; SleepEDF-78: n = 153; PC2018: n = 994). In some datasets, individual participants contributed multiple recordings, which were treated as independent biological replicates because each recording represents a distinct physiological observation. No technical replicates were included. b Generative performance under varying mask ratios. Results focus on the F3 and Pz channels, with channel-specific performance averaged across relevant datasets. Overall performance represents the mean NMSE over all available datasets for each channel under each mask ratio. c,d Enhancement in sleep staging through PSG signal generation. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) across 10 independent experiments (n = 10). c Overall performance metrics (ACC, MF1, and Kappa) for models trained on 1, 2, 5, and 12 subjects from the original SleepEDF-20 dataset compared with the augmented SleepEDF-20 dataset. Statistical significance of performance differences for ACC, MF1, and Kappa was evaluated using a two-tailed t-test. P values are indicated as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. d Per-class F1 scores for the same training conditions, illustrating the impact of dataset augmentation on the performance of different sleep stages. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The C3 and C4 channels, due to their similar electrode placements, exhibited nearly identical performances as reflected by their NMSE metrics. Remarkably, the F3, FPz, Pz channel consistently outperformed other channels in all datasets that recorded these three channels. The overall boxplot details the NMSE across all eight channels, highlighting that the FPz and Pz channels achieved better outcomes with NMSE metrics nearly one tenth of others, emphasizing their superior performance.

We further illustrate the model’s performance across different mask ratio configurations (Fig. 5b). The F3 and Pz channels were individually evaluated across datasets, selected for their consistently superior performance and presence in five of the eight datasets analyzed (Fig. 5a). As the mask ratio increases, the F3 channel’s NMSE rises gradually to 1.546, 1.156, 1.246, 1.074, and 1.270 across the MASS-SS1, MASS-SS2, MASS-SS3, MASS-SS5, and PhysioNet2018-test datasets respectively at a 90.0% mask ratio. Meanwhile, the Pz channel’s NMSE slightly increases to 0.423, 0.223, 0.143, 0.170, and 0.137 for the MASS-SS1, MASS-SS2, MASS-SS3, MASS-SS5 and SleepEDF-78 datasets respectively. This indicates the model’s robust generative capability of these two channels under various conditions. The overall results show that FPz and Pz channels consistently perform well with minimal NMSE fluctuations of around 0.500 and 0.050, respectively. Across all channels except EMG, the maximum NMSE fluctuation is 0.595, demonstrating stable performance.

Enhancement in sleep staging via sleep data generation

Generative models have demonstrated potential in augmenting small sleep datasets62,63,64, yet limited by a focus on single-task applications or the inability to support multi-channel sleep data generation, hinder their effectiveness in achieving comprehensive and scalable sleep decoding. To address this, we evaluated whether a multi-channel sleep data generation strategy (Methods), using SleepGPT, could improve sleep staging performance in scenarios with extreme data scarcity. Both the SleepEDF-20 dataset, comprising 20 subjects with 4 subjects reserved for validation, and the MASS-SS2 dataset, comprising 19 subjects with 3 subjects reserved for validation, were adopted for the study. We conducted four experiments to assess the impact of sleep data generation through PSG signal synthesis at the epoch level (30 seconds). In each experiment, the training set consisted of 1, 2, 5, or 12 subjects, respectively, while the test set, comprising 4 subjects, was held constant across all experiments (Methods). The experiments compared performance metrics for models trained on the original datasets, which contain unaltered PSG recordings, versus those trained on the augmented datasets (Methods), highlighting the impact of PSG signal generation on improving sleep staging accuracy and robustness. The augmented dataset was generated by combining the original dataset with reconstructed data obtained by applying a 75.0% mask ratio to the original dataset, where epochs were randomly masked. This process effectively doubled the dataset size.

For the SleepEDF-20 dataset, significant improvements were observed on the usage of augmented dataset compared to the original dataset (Fig. 5c): ACC increased by 24.1 p.p. (P < 0.0001), MF1 by 34.7 p.p. (P < 0.001), and Kappa by 0.521 (P < 0.0001) with 2 subjects. In terms of per-class F1 scores, SleepGPT fine-tuned with augmented dataset showed the capability to correctly classify different sleep stages (Fig. 5d). Notably, for the W and N2 stages, using augmented datasets with two subjects led to a statistically significant enhancement in F1 score (P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Table 13).

In the MASS-SS2 dataset, classification of sleep stages using 1, 2, and 5 subjects from the original dataset predominantly resulted in misclassifications (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, employing an augmented dataset with 5 subjects led to notable increases in ACC, MF1, and Kappa, reaching 72.6%, 51.4%, and 0.542, respectively. The per-class F1 scores analysis with 5 subjects revealed that the most significant improvement was in the Wake stage, which increased by 0.8 p.p. to 40.5% (P < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 14).

Evaluation of sleep spindle detection leveraging the original dataset

Sleep spindle detection is essential for identifying sleep stages and diagnosing neurological disorders65. It aids in understanding crucial aspects of sleep quality and brain function. Inspired by success of SpindleU-Net66,67, we approached the detection task as an event-wise classification problem, where ones represent sleep spindles and zeros represent non-sleep spindles (Methods). In this context, we utilized the original MASS-SS2 dataset, consisting of unaugmented, raw PSG recordings where each epoch has a duration of 20 s. We reported the F1 score, precision and recall metrics68. Precision is the proportion of true positives among all positive predictions, showing how accurate the model’s positive predictions are. Recall, on the other hand, the proportion of true positives among all actual positives, reflecting the model’s ability to identify positive cases. The F1 score balances precision and recall, providing a single metric that accounts for both false positives and false negatives.

To ensure an unbiased evaluation, annotations from two independent experts with extensive experience in sleep medicine, referred to as Expert 1 and Expert 2, were utilized as the ground truth, respectively. Details about the data and annotations are provided (Supplementary Note 4). Using the original dataset, our model demonstrated substantial capability in detecting sleep spindles, achieving an F1 score of 71.7%, precision of 65.7% and recall of 78.7% with annotations from Expert 1. In addition, with Expert 2’s annotation, the model achieved an F1 score of 79.1%, precision of 77.3% and recall of 81.0%. These results underscored the model’s robust performance, particularly with Expert 2, where it tended to produce more consistent and higher metrics (Fig. 6a). The F1 scores of most subjects are relatively stable with both Expert 1 and Expert 2. However, the model’s performance is limited by the small dataset size. We assessed the correlation between the number of sleep spindles and F1 scores using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) to quantify the strength of the linear relationship, and P-values to evaluate statistical significance. The correlations for both experts were significant (Expert 1, Pearson’s r = 0.677, P = 0.001; Expert 2, Pearson’s r = 0.679, P = 0.005).

a Model performance comparison with Expert 1 and Expert 2 annotations using the original dataset (MASS-SS2) and correlation between F1 scores and the number of sleep spindles. The left panel plots illustrate the per-subject distribution of three metrics (F1 score, precision, recall) for each expert, highlighting variability and outliers. Each box plot shows the median (center line), 25th-75th percentiles (box limits), whiskers extending to 1.5 × the interquartile range (IQR), and points representing outliers. The number of subjects (n) corresponds to the number of independent participants annotated by each expert (Expert 1: n = 19; Expert 2: n = 15), each representing a biological replicate. No technical replicates were used. The right panel shows the correlation between F1 score and the number of sleep spindles, with the regression line representing the best linear fit and the shaded band indicating the 95% confidence interval. b An illustration of generating a new epoch with sleep spindles from original signals, which originates from Subject 1 in the MASS-SS2 dataset. Random masking ensures that patches from both the time-domain and frequency-domain corresponding to the same time are simultaneously masked, preserving the temporal consistency between two domains during augmentation. c Per-subject results of F1 score, precision, and recall are presented for the dataset augmented from the original data using PSG signal generation. Each box plot shows the median (center line), 25th-75th percentiles (box limits), whiskers extending to 1.5 × the interquartile range (IQR), and individual points representing outliers. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Sleep spindle detection enhanced through dataset augmentation

Due to the high costs associated with manual labeling, obtaining annotated sleep spindles is challenging. Enhancing detection performance through dataset generation is an effective strategy to get sufficient training data69. Inspired by the success of Spindle U-Net, which manually doubled the size of the MASS-SS2 dataset, and drawing from our own experiments examining the correlation between sleep spindle counts and classification performance, we leveraged the model’s capability to generate new epochs, thus constructing an augmented dataset (Fig. 6b). Specifically, during the preprocessing stage, we randomly masked patches within the epochs, ensuring that each epoch retains at least one-quarter of a sleep spindle. Subsequently, we generated the masked portions once to synthesize new epochs. This masking process was applied to both the time and frequency domains, using a mask ratio of 75.0% (Methods). The final training dataset, referred to as the augmented dataset, was a combination of the new synthetic dataset and the original dataset.

Leveraging the augmented training dataset generated through data augmentation, we reported the F1 score, precision, and recall for each subject annotated by Expert 1 and Expert 2 (Fig. 6c). Using Expert 1’s annotations, the overall F1 score, precision and recall were 72.2%, 66.7% and 78.7%, respectively. With Expert 2’s annotations, these metrics were 79.2%, 78.2% and 80.3%, respectively. Compared to the original dataset, employing the augmented dataset resulted in improved performance. With Expert 1’s annotations, the F1 score increased by 0.5 p.p., and precision improved by 0.9 p.p. For Expert 2’s annotations, the F1 score increased by 0.1 p.p., and precision by 0.9 p.p. Overall, the use of the augmented dataset led to more balanced and robust performance across all metrics.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal that SleepGPT, a generative pretrained transformer, significantly advances the capabilities of automated sleep staging, sleep-related pathology classification, sleep data generation, and sleep spindle detection across diverse configurations. By effectively leveraging large-scale multi-channel PSG signals, SleepGPT not only improves sleep decoding performance but also offers a scalable solution for enhancing clinical workflows and research methodologies in sleep medicine. SleepGPT can be adaptively fine-tuned on individual patient recordings, such as across multiple visits or during longitudinal monitoring. Leveraging its large-scale pretraining, the model can be efficiently updated with small amounts of patient-specific data, enabling it to capture individual sleep patterns over time and supporting personalized clinical applications. SleepGPT could play a transformative role in both research and clinical settings, particularly in the early detection and personalized treatment of sleep disorders such as SSA and RBD. SleepGPT also supports interpretability analyses that can facilitate clinical adoption. Techniques such as attention visualization70 and Integrated Gradients71 can highlight temporal and spectral regions most relevant to each prediction, while the built-in channel-wise attention provides insight into which EEG channels or sensor modalities contribute most. These features help clinicians better understand and trust the model’s decisions. Moreover, SleepGPT can be adapted to wearable devices with limited channels, further expanding its applicability in home-based and resource-limited settings.

U-Sleep employs an adaptive channel strategy and has been shown to handle a wide range of channel combinations robustly, it processes one EEG and one EOG channel at a time. In contrast, SleepGPT is designed to jointly integrate information from multiple channels within a unified dual-domain backbone, enabling it to directly model cross-channel relationships and support multi-channel tasks without requiring repeated evaluations for different channel configurations. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, the final embeddings for sleep staging depend significantly on the integration of various channels, with different sleep stages necessitating distinct channel weights. In contrast, our SleepGPT model demonstrates an intrinsic capability to understand and integrate the relationships between multiple channels, according to comparison between two versions of the combined MASS datasets (MASS-SS1 to SS5). Our approach not only encompasses EEG but also includes EMG and EOG channels, achieving comprehensive multi-channel relationship extraction. Additionally, Fig. 3c highlights the underutilized significance of Pz channel in sleep staging, offering new insights for both multi-channel and single-channel PSG configurations in sleep staging and suggesting approaches for mobile health wearables. By analyzing the influence of each PSG channel, we can identify which channels contribute most to model performance, providing guidance for model deployment and data acquisition strategies rather than directly informing individual treatment plans.

Furthermore, our analysis of disease classification tasks underscores the importance of PSG signals. For example, SSA is traditionally classified as a respiratory disorder, with conventional methods heavily relying on electrocardiography and respiratory channels. However, SleepGPT effectively utilizes entire-night PSG recordings, leveraging EEG, EMG, and EOG channels, demonstrating that SSA-related brain activity could provide valuable diagnostic insights and the model’s ability to leverage abnormal sleep stage distributions for disorder classification. This observation supports the hypothesis that SSA might lead to or associate with electrophysiological impairments. Similarly, for NFLE classification, SleepGPT achieves exceptionally high recall rates, efficiently distinguishing NFLE patients from other groups. This suggests that NFLE might have a pronounced neurophysiological impact, making PSG signals critical for accurate classification. Regarding the influence of sleep stages on disease classification, we observe that features from the N1 stage act as potential noise for both NFLE and RBD classification, even reducing overall classification performance. This indicates that the N1 stage may have limited relevance to these two conditions, further emphasizing the need for selective feature integration in disease-specific diagnostic frameworks. These findings not only enhance our understanding of the physiological underpinnings of sleep-related pathologies but also highlight SleepGPT’s potential for advancing precision medicine.

Additionally, we propose that the suboptimal performance of EMG signals both in sleep staging and reconstruction, may stem from the transformer’s inherent limitations in effectively handling high-frequency signals72. The purpose of incorporating generative capabilities is to expand small datasets and repair various artifacts. Our results show that even naive augmented datasets outperform the original datasets, especially in scenarios with data scarcity.

In sleep spindle detection, SleepGPT notably enhances detection accuracy by augmenting the dataset with newly generated epochs. We observed that when the test data includes a higher number of sleep spindle events, the model can better identify these features, resulting in improved classification performance. Our model’s ability to generate new epochs allows for extensive application of augmentations, thereby significantly enhancing overall performance. The results of sleep spindle detection demonstrate that our model has significant potential in clinical settings, with most subjects achieving high recall scores. Regarding the importance of recall, automatic detection systems can adjust thresholds to balance precision and recall, but researchers often prioritize high recall73. In sleep spindle detection, false positives are usually easier to handle than false negatives. Post-processing can filter or verify false positives, while missed sleep spindles lose their chance for analysis. Beyond spindle detection, SleepGPT is designed as a generalizable backbone that can be extended to other clinically relevant sleep events. In principle, the same pretraining framework and multi-channel fusion strategy can be adapted for event-level detection tasks. By fine-tuning on appropriately labeled datasets, SleepGPT could be extended to detect apnea episodes, arousals, or periodic limb movements. These events share similar temporal and spectral signatures within PSG signals, and the model’s ability to jointly capture time-domain and frequency-domain patterns make such adaptations feasible.

Additionally, the SHHS-2 dataset was included during pretraining. Due to an overlap in subjects between the SHHS-1 and SHHS-2 datasets, this inadvertently introduced an overlap between the pretraining data and the downstream test data for the SHHS-1 dataset in the sleep staging task. Specifically, 756 subjects in the SHHS-1 test set correspond to subjects also included in the SHHS-2’s pretraining set, while the remaining 960 subjects are from entirely non-overlapping subjects, representing unseen data. To evaluate the potential impact of this overlap, we conducted a separate analysis of the two subsets. On the non-overlapping subset, SleepGPT achieved an ACC of 88.8%, an MF1 score of 81.9%, and a Kappa of 0.841, indicating strong generalizability to unseen subjects (Supplementary Table 15). Meanwhile, the overlapping subset achieved slightly higher metrics, with an ACC of 89.3%, an MF1 score of 82.7%, and a Kappa of 0.848, suggesting that the overlap may confer a minor performance advantage. Despite this overlap, the model’s strong performance on the non-overlapping subset underscores its ability to generalize effectively, demonstrating robustness for real-world scenarios.

Despite the notable advancements achieved with SleepGPT, several limitations should be acknowledged. For spindle detection and sleep-disorder classification, we did not include direct comparisons with specific deep learning benchmark models because publicly available implementations with reproducible code or pretrained weights are scarce, and most prior studies in these tasks have relied on traditional machine-learning approaches rather than end-to-end deep learning baselines. In addition, while data augmentation improved precision for expert 2 by 0.9 p.p. in spindle detection, it also led to a 0.7 p.p. drop in recall, indicating that the improvement is not purely additive and highlighting a trade-off that should be considered when interpreting these results. Another key limitation lies in the model’s computational intensity, which results from the quadratic complexity of transformer blocks. This complexity poses challenges for real-time clinical applications, particularly in CPU-only environments where processing speed and efficiency are critical. Furthermore, our current pretraining does not include large-scale wearable datasets and other publicly available datasets, and hardware constraints limited further scaling of model size and data. Nevertheless, SleepGPT demonstrates strong adaptability across diverse datasets and downstream tasks, requiring minimal fine-tuning to achieve robust performance and thereby reducing deployment time. With ongoing advancements in hardware, we anticipate that these computational constraints will gradually diminish, making models like SleepGPT increasingly practical for real-time clinical use.

In conclusion, the SleepGPT model represents a significant advancement in sleep stage classification by leveraging multi-channel PSG signals, thus offering new avenues for both theoretical research and practical applications in sleep medicine. Leveraging diverse datasets, SleepGPT demonstrates its capability to effectively classify sleep-related pathologies, providing a robust framework for advancing diagnostic tools and improving understanding of sleep-related disorders. The model’s PSG signal generation capabilities address two critical areas: mitigating noise from overnight PSG sampling and expanding datasets to enhance downstream task performance. By reducing noise, the model ensures cleaner, more reliable data, leading to improved classification accuracy. Expanding datasets allows for better generalization across diverse conditions and populations, enhancing robustness and applicability. Additionally, SleepGPT excels in sleep spindle detection with high recall metrics, crucial for comprehensive sleep decoding and accurate diagnosis. These features highlight the model’s versatility and efficacy in addressing complex challenges in sleep research, ultimately contributing to improved diagnostic tools and treatment plans in clinical settings.

Methods

Details of dataset

SleepGPT is developed using 14 PSG datasets from six independent databases (Supplementary Table 1). All databases are linked to independent clinical or basic studies. All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the study, in accordance with the protocols approved by the relevant institutional ethics committees.

We pretrain SleepGPT on four datasets: PhysioNet2018-test, SHHS-1, SHHS-2, and SleepEEGfMRI. It is important to note that we randomly split the SHHS-1 dataset into 70.0% pretraining data and 30.0% testing data, which aligns with the practices of some previous supervised learning studies6,42(Supplementary Table 2). The channels used in each dataset during pretraining, along with the validation set, are shown in Supplementary Table 4.

To assess our model’s sleep staging capabilities, we apply both supervised and unsupervised learning methods evaluation scheme. In comparison to other supervised learning methods, a K-Fold cross-validation evaluation scheme was employed for comprehensive dataset assessments, ensuring no overlap with datasets used during pretraining. This approach highlights the fine-tuning challenges inherent in supervised learning (Supplementary Table 6). Only the SHHS-1 dataset uses a hold-out evaluation scheme exposed during pretraining6. In contrast, unsupervised learning evaluation scheme divides datasets into pretraining, fine-tuning, and testing segments, requiring minimal labeled data to achieve satisfactory performance. We adhere to specified partitioning protocols from respective publications for a fair performance comparison and follow publicly available code where applicable (Supplementary Tables 10, 11). Notably, we utilize only fine-tuning and testing datasets, without any additional pretraining on new datasets. When evaluating on wearable data, we applied a 20-fold cross-validation scheme. In assessing the individual effects of the F3 and Pz channels across four MASS datasets, we randomly select 70.0% of the dataset as training sets and reserve the remaining 30.0% for testing. For the sleep-related pathology classification task, we utilize the CAP and SHHS-1 datasets (Supplementary Note 3). To validate the generative ability of our model on the sleep staging task, we randomly select sub-datasets of 1, 2, 5, and 12 subjects from the SleepEDF-20 and MASS-SS2 datasets as training sets, respectively. This selection represents conditions of extreme data scarcity. For validation, a separate set of 4 subjects (from SleepEDF-20) or 3 subjects (from MASS-SS2) is used, while the remaining 4 subjects are designated as the test set in both the SleepEDF-20 and MASS-SS2 datasets. For sleep spindles wave detection, we maintain consistency with prior works66,74,75, employing a 5-fold cross-validation evaluation scheme and using our model’s generative capabilities to enrich the MASS-SS2 dataset (Supplementary Note 4).

CAP

The CAP sleep database is a comprehensive dataset focusing on the cyclic alternating pattern, a periodic EEG activity observed during NREM sleep, which is associated with various sleep-related disorders. Collected from the Sleep Disorders Center at Ospedale Maggiore in Parma, Italy, the database consists of 108 PSG recordings. It includes signals from at least three EEG channels (F3/F4, C3/C4, O1/O2, referenced to A1/A2), a CHIN1-CHIN2 EMG channel, a bilateral anterior tibial EMG channel, two EOG channels, electrocardiography channels, and respiratory signals (airflow, abdominal and thoracic effort, SaO2), as well as annotations for sleep stages and cyclic alternating pattern events. The dataset includes recordings from 16 healthy subjects and 92 patients diagnosed with various pathologies such as NFLE, RBD, periodic leg movements, insomnia, narcolepsy, sleep-disordered breathing and bruxism, offering valuable resources for both clinical research and the development of automated cyclic alternating pattern analysis systems.

MASS

MASS is an extensive collection specifically designed to support the scientific community in sleep analysis and automatic sleep stage classification. It is collected by the Center for Advanced Research in Sleep Medicine (CÉAMS), located in Montreal, Canada. This database comprises five subsets (MASS-SS1 to SS5) and includes 200 whole-night sleep recordings from a diverse population, including healthy subjects, individuals with insomnia, and those with sleep apnea. Sleep stages in MASS are manually annotated by experts according to the AASM guidelines for the MASS-SS1 and MASS-SS3 datasets, and the Rechtschaffen and Kales (R&K) standard76 for the MASS-SS2, MASS-SS4, and MASS-SS5 datasets. Under the R&K standard, epochs are classified into eight categories: W, N1, N2, N3, NREM stages 4 (N4), REM, MOVEMENT, and UNKNOWN. Following previous practices6,42,44, to convert R&K annotations into AASM sleep stages (W, N1, N2, N3, and REM), the N3 and N4 stages are merged into a single N3 stage and epochs labeled MOVEMENT or UNKNOWN are excluded to ensure data quality and consistency. For sleep staging, 20 s epochs are expanded to 30 s by incorporating additional 5 s segments before and after each epoch. Due to the variability in channels across different subsets, we offer two supervised learning strategies: one using consistent channels across all five subsets, and another using variable channels suited to each subset specific data when aligning with our model (Supplementary Table 6). For sleep spindle detection, we used the MASS-SS2 dataset. We utilized 20 s epochs and focused on the C4 channel to ensure comparability and accuracy in sleep spindle detection (Supplementary Note 4).

PhysioNet2018

The PhysioNet2018 database, also known as the “You Snooze, You Win" challenge, focuses on classifying sleep stages from a large set of recordings sourced from Massachusetts General Hospital’s sleep laboratory. This database comprises 1983 subjects and is utilized in the 2018 PhysioNet challenge to detect arousal during sleep. It contains two datasets, training and testing, but only the training subset includes annotations for sleep stages according to the AASM guidelines. We employ the C3-M2, C4-M1, F3-M2 and O1-M2 EEG channels along with the CHIN1-CHIN2 EMG channel, and the E1-M2 EOG channel (M2 and M1 are reference points for zero potential in EEG and EOG and CHIN1-CHIN2 represents EMG signals recorded between two electrodes placed on the chin).

SHHS

The SHHS database is a multicenter cohort study aimed at investigating the cardiovascular and other health consequences of sleep-disordered breathing. Data are collected from multiple clinical research centers across the United States31,32. It features two rounds of PSG recordings, the SHHS-1 dataset with 5791 subjects and the SHHS-2 dataset with 2651 subjects, encompassing a wide age range from 39 to 90 years. The manual scoring is completed using the R&K guidelines. Similar to other databases annotated with the R&K rule, we merge N3 and N4 stages into a single N3 stage and exclude MOVEMENT and UNKNOWN epochs. We utilize the C4-A1 EEG channel, the C3-A2 EEG channel, the bipolar submental EMG channel, and the LOC EOG channel in our experiments (A1 and A2 are reference points for zero potential in EEG, and LOC EOG represents the left outer canthus electrode used to monitor eye movements). We exclude certain subjects with erroneous markings, consistent with previous studies6. After exclusion, the SHHS-1 and the SHHS-2 datasets comprised 5,721 and 2,518 subjects, respectively

Sleep-EDF

The SleepEDF Expanded collection consists of two datasets: SleepEDF-20 (2013 version) and SleepEDF-78 (2018 version), both providing recordings for sleep analysis. Data for the Sleep-EDF collection are sourced from the Sleep Disorder Center of the Hôpital Hôtel-Dieu in Paris, France. The SleepEDF-20 dataset comprises recordings from 20 younger subjects (25–34 years old), while the SleepEDF-78 dataset includes data from 78 healthy Caucasian subjects aged 25–101. Each subject underwent two consecutive day-night recordings, except for a few data losses due to equipment failures (one night for subject 13 in the SleepEDF-20 dataset, and subjects 13, 36, and 52 in the SleepEDF-78 dataset). Recordings are segmented into 30-second epochs and manually annotated by sleep experts following the R&K standards. Epochs are classified into eight categories: W, N1, N2, N3, N4, REM, MOVEMENT, and UNKNOWN. For sleep staging, N3 and N4 stages are combined into a single N3 stage, and epochs labeled as MOVEMENT or UNKNOWN are excluded to ensure data quality and consistency. Both datasets employ the FPz-Cz and Pz-Oz EEG channels (with Cz and Oz as reference points), the horizontal EOG channel, but omit the EMG channel due to its unavailability. To address the disproportionate size of the W class, only 30 minutes of W epochs before and after the sleep period are included in the analysis6,42,44.

SleepEEGfMRI

The database contains 138 individuals, each participant underwent data acquisition on a 3T Siemens MAGNETOM Prisma MRI scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) together with a 64-channel MRI-compatible EEG system (Brain Products, Munich, Germany) in the Center for MRI Research at Peking University in Beijing, China. Simultaneous EEG and fMRI data collection continued until the participant was fully awake and unable to sleep77. Only the EEG data is analyzed in the current study. The EEG data are processed using BrainVision Analyzer 2.1 (Brain Products, Munich, Germany), with sleep stages classified into W, N1, N2, N3, and REM, or UNKNOWN, according to the AASM guidelines. UNKNOWN epochs are excluded. We utilize eight channels including six EEG channels: C3, C4, F3, FPz, O1, and Pz, along with one EMG channel and one EOG channel. The signals from the M1 and M2 electrodes are averaged to serve as the reference for these recordings. This specific montage is chosen to optimize spatial resolution and signal quality, essential for detailed analysis of sleep stages. The SleepEEGfMRI protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Peking University. Each subject signed consent form.

UMS

This study utilized data from an observational study with a within-subject design, conducted at the Sleep Medicine Center of Shenzhen People’s Hospital in China between October 14, 2020 and May 12, 2021. All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of Drug Clinical Trial of Shenzhen People’s Hospital (approval number: SYL-202010-03). In total, 203 Chinese adults recruited from a sleep medicine center underwent an overnight study wearing a forehead sleep recorder (UMindSleep, EEGSmart Co., Ltd.) and PSG simultaneously. During data collection, each participant underwent full-night in-laboratory monitoring using the Philips Alice 6 PSG system (Philips, Respironics, Murrysville, Pennsylvania). The recorded signals included comprehensive electrophysiological channels for sleep evaluation, airflow measurements via thermistor and nasal pressure, and pulse oximetry. Ultimately, data from 197 participants without PSG artifacts or UMindSleep disconnection, aged 20–63 years (mean ± SD: 37 ± 8.7 years; 148 males) were included in the final analysis. Among these, 171 participants (86.8%) were diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) by standard PSG. Because our goal was to perform sleep staging based on wearable signals, it was necessary to align the wearable recordings with the simultaneously collected PSG signals and use the PSG scoring as the gold standard. To ensure data quality, we excluded PSG recordings in which more than half of the sleep stage labels were unscored, as well as wearable recordings that, after alignment with PSG, contained less than two hours of valid data. After applying these criteria, data from 179 participants were retained for further analysis.

Preprocessing

No preprocessing is conducted on the raw data, except for the SHHS-1 and SHHS-2 datasets. The SHHS-1 and SHHS-2 data are filtered between 0.3–35 Hz, and electrocardiogram noise is attenuated using a linear model. We refer to the dataset that undergoes preprocessing as the “original dataset", while the “augmented dataset" refers to an expanded version of the original dataset, which incorporates additional synthetic data generated through our model.

Patches and patch tokens

In the context of SleepGPT, a patch refers to a smaller, localized segment of the input signal or spectrogram. Patches are extracted to enable fine-grained feature learning and ensure compatibility with Transformer-based architectures. For time-domain signals, patches are obtained by segmenting each channel’s signal into fixed-length windows capturing temporal patterns within localized time intervals. For frequency-domain signals, patches are created by slicing the spectrogram along the temporal axis. Each patch represents the frequency-domain characteristics of the signal within a small-time window, preserving short-term frequency dynamics. This segmentation allows the model to capture local spectral features while maintaining alignment with corresponding time-domain patches. These patches are subsequently mapped into high-dimensional feature representations, known as patch tokens, which serve as the input to the transformer model.

Input embeddings

We demonstrate the key symbols used in the embedding, pretraining, UTF transformer and downstream tasks section together with their definitions and roles in the model (Supplementary Table 16). We harness a training dataset \({\{{X}_{n}\}}_{n=1}^{N}\) comprising N epochs, where each epoch X = {xi∣i = 1, …, L} signifies a sleep PSG recording of length L (equivalent to the sampling rate fs multiplied by the epoch duration T). The dataset is initially normalized, aligning it with global mean and standard deviation values that are precomputed across the entire dataset to ensure consistent standardization.

Acknowledging the complex nature of sleep dynamics, our model is adeptly designed to incorporate time-frequency inputs, effectively representing the data in both time-domain and frequency-domain. To achieve this, each epoch Xi is transformed into a time-frequency spectrogram by short-time Fourier transform, utilizing a 2-second Hamming window with a 50.0% overlap and a 256-point Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). The amplitude spectrum obtained from the FFT is then log-transformed. To retain physiologically relevant features, only the low-frequency (the first fs frequency bins) components are preserved, with higher frequencies discarded, denoted as F. This processing yields a paired representation of each epoch, denoted as \(S={\{{X}_{n},{F}_{n}\}}_{n=1}^{N}\), which integrates both time-domain and frequency-domain signals.

For the 1D time-domain signals \(X\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{C\times L}\), we employ channel-wise 1D convolution to segment and reshape them into \({P}_{r}=\frac{L}{r}\) patch tokens \({X}^{P}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{C\times {P}_{T}\times D}\), where L is the length of signals, r denotes the time-domain patch resolution, C is the number of channels and D represents the input embeddings dimension (Supplementary Fig. 6). These time-domain patch tokens are subsequently flattened along first two dimensions, and a special marker patch, [T_CLS], is appended at the beginning of the sequence \({X}^{Flatten}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{(C\cdot {P}_{T}+1)\times D}\). The final time-domain embeddings \({X}^{Input}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{(C\cdot {P}_{T}+1)\times D}\) are derived by summing the flattened patch tokens, 1D learnable positional embeddings, channel embeddings, and token type embeddings.

A similar methodology is applied to the 2D frequency signals \(F\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{C\times T\times H}\). These signals are processed using channel-wise 2D convolution and are partitioned and reshaped into \({P}_{F}=\frac{T}{l}\times \frac{H}{h}\) patch tokens \({F}^{P}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{C\times {P}_{F}\times D}\), where (l, h) specifies the frequency patch resolution, T represents the maximum duration of one epoch, and H denotes the points obtained from FFT. Frequency patches are also flattened and a specially marked [F_CLS] is added to the sequence \({F}^{Input}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{(C\cdot {P}_{F}+1)\times D}\). The embeddings in the frequency-domain are similarly obtained by summing the corresponding embeddings.

In our model, we synchronize the number of patches across the time-domain and frequency-domain. This synchronization facilitates the precise alignment of time stamps across different domains, thereby enhancing the coherence of time-frequency integration. Specifically, the time-domain resolution r is determined by the product of the frequency-domain window length l and the sampling rate fs, such that r = l × fs. Furthermore, we set the other parameter in the frequency resolution h equals H. The final stage involves the concatenation of the two embeddings into a single composite \({H}_{0}=[{X}^{Input};{F}^{Input}]\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{(C\cdot 2P+2)\times D}\), where P equals to PF or PT. This composite embedding, H0, integrates both domains and serves as the input to the zeroth layer of the UTF transformer, enabling joint processing of time-domain and frequency-domain features.

UTF transformer

The UTF transformer framework, central to our model, is designed to capture the complex relationships between time-domain and frequency-domain signals in PSG. We demonstrate through ablation experiments the necessity of time-frequency fusion and the use of the unified transformer architecture (Supplementary Fig. 7). Specifically, replacing the unified transformer with a dual-encoder architecture (SleepGPT-Dual) or using only the EEG signal (SleepGPT-EO) results in performance degradation. These results highlight the effectiveness of both modality fusion and unified modeling in achieving robust sleep staging. Furthermore, leveraging only the frequency-domain input (SleepGPT-FO) or the time-domain input (SleepGPT-TO) leads to performance drops across all metrics, demonstrating the importance of both representations.

Through a masked multi-head self-attention (MSA) mechanism within its M-depth blocks, it effectively aligns and synthesizes time-domain and frequency-domain data, capturing both local and global patterns in the time-frequency spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 8). For the i-th UTF transformer block, the masked MSA operation takes the output Hi−1 from the (i-1)-th UTF transformer block as input and is formulated as:

where LN is layer normalization. The UTF transformer diverges from traditional architectures by incorporating switching perceptron functions–time-domain, frequency-domain, and unified–in lieu of the usual feed-forward layers, allowing distinct domain representations to be mapped to their respective latent spaces. Initially, in the bottom of (M − K) blocks, the time-domain perceptron (T-PCN) and frequency-domain perceptron (F-PCN) separately process their respective domain representations derived from the masked MSA, preserving inherent domain-specific features and facilitating the learning of intra- and inter-domain connections within a reduced semantic space.

In the model’s upper layers, particularly the top K blocks, a trio of domain-specific perceptron functions is introduced to process input representations derived from the masked MSA, which contain both time-domain and frequency-domain information. Depending on the task requirements, the inputs are either processed separately through the T-PCN and F-PCN or integrated directly through the unified perceptron (U-PCN). This architecture ensures that the model does not conflate the domains, maintaining the integrity of the features in each domain and enabling a comprehensive learning of the interconnections between them. The outputs of i-th UTF transformer block are formulated as follows:

Input representations \({H}_{i}^{{\prime} T}\) and \({H}_{i}^{{\prime} F}\) are time-domain and frequency-domain embeddings from the output of the masked MSA. The final outputs of the UTF transformer, referred to as epoch embeddings, are defined as O.

Pretraining stage

Our model introduces an innovative multi-pretext task learning framework, harnessing the strengths of well-established strategies, including contrastive learning, hard negative mining, and masked autoencoder techniques. This integrated approach leverages contrastive learning to refine the coherence and reinforce the complementarity of cross-domain features, while hard negative mining accelerates the process by enhancing the model’s ability to distinguish and align features across different domains. Additionally, the masked autoencoder approach focuses on reconstructing original signals from latent representations, uncovering the intricate structure and nuanced information inherent in the data.

In the process of contrastive learning, for a given batch size of N, the model embarks on a time-frequency contrast task, striving to identify matched pairs among N × N potential time-frequency pairs. The time-domain embeddings are processed through M stacked UTF transformer blocks with the T-PCN. Similarly, frequency-domain embeddings are processed through M stacked UTF transformer blocks with the F-PCN (Supplementary Fig. 1). For outputs Oi and Oj from batch i and batch j, the model leverages the time ([T_CLS]) and frequency ([F_CLS]) markers from the final output, representing OT and OF respectively, which encapsulate global time and frequency inter- and intra-relations. The contrastive matrices for time-to-frequency (T2F) and frequency-to-time (F2T) are calculated by measuring the similarity scores between time-domain and frequency-domain embeddings, and are defined as follows:

where TP denotes the transpose operation and σ represents a learnable temperature parameter. The contrastive loss, designed to enhance the similarity of time-frequency pairs within the same batch, is defined as:

Post this contrastive learning phase, the model, equipped with U-PCN at the top K blocks, identifies hard negative samples to perform time-frequency matching, thereby distinguishing time-domain and frequency-domain embedding pairs across different epochs (Supplementary Fig. 2). Hard negative samples are selected using a contrastive matrix. Specifically, the softmax function is applied to each T2F and F2T similarity score, transforming raw scores into a probability distribution:

Subsequently, the diagonal of the similarity matrices is masked to exclude correct pairs, and a stochastic sampling process generates a new batch of mismatched pairs. These pairs are then fed back into the model for binary classification with cross entropy loss, determining the matching status using the [T_CLS] marker.

To ensure robust feature representation learning in both time-domain and frequency-domain, batches from different GPUs are consolidated during the time-frequency matching and contrastive learning stages. The large batch size introduces a wider array of negative samples, compelling the model to develop more robust and distinct feature representations.