Abstract

Ionic thermoelectric (i-TE) have become promising candidate for harvesting low-grade thermal energy. However, the development of n-type i-TE materials still lag far behind their p-type counterparts, which impedes the application. Herein, engineering a liquid crystal elastomer (LCE) from side-chain to main-chain structure, just swollen with single LiBF4 or EMIM TFSI, enables the largest adjustable p-n (28.8 ~ −27.4 mV K−1) span among current homologous materials below 30% RH. These high n- and p-type performance further ensure the successful integration of a homogeneous π-type fiber-shaped i-TE capacitor, where three p/n pairs yield an output voltage of 402.5 mV under a tiny temperature difference of 2.5 K. The areal energy density of per n-type fiber reaches 8.1 mJ m−2. More importantly, the i-TE materials also exhibit excellent stability under loadings of cyclic stretching, long-term testing, or temperature-controlled cycling, highlighting its potential for efficient thermal-charge energy storage in flexible electronics and smart wearables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, the emerging ionic thermoelectric (i-TE) materials have gradually drawn extensive attention due to their ultra-high thermopower1. Among the i-TE materials, quasi-solid ionogels- that is, polymeric networks swollen with salts - have shown considerable promise for applications in heat harvesting and wearable applications due to their excellent mechanical characteristics, good thermal stability, and non-volatile2,3,4. And the quasi-solid TE ionogels operate in two mechanisms and correspondingly work in two modes: (1) Thermogalvanic effect and thermogalvanic cells work mode; (2) Soret effect and i-TE capacitors work mode. Among these, the Soret effect could induce a higher thermopower (>10 mV K−1), recently drawing notable interest in the field of thermal sensing and low-grade heat harvesting. Soret effect operating capacitive i-TE devices requires both p-type and n-type TE ionogels to ensure an enough voltage and thereby an efficient output energy/power. However, the current available category and performance of n-type i-TE materials still lag far behind those of p-type counterparts, and n-type and p-type characteristics in homologous materials are highly challenging, restricting the development of i-TE capacitors5,6,7.

The Kinetics behind the Soret effect is the generation of ionic thermoelectric potential driven by temperature gradient-inducing changes in chemical potential and entropy (Eastman entropy) between the anions and cations inside the polymeric networks. Thereby, the achievement of high-performance n-type feature requires amplifying anion-dominated mobility difference and Eastman entropy in the polymeric networks6. Pioneering studies have found the feasible n-type feature of lithium salts (lithium tetrafluoroborate (LiBF4), lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI)), sodium salts (sodium chloride (NaCl)) and transition metals (Iron(III) chloride (FeCl3), Copper(II) chloride (CuCl2)), swelling in the polymeric networks including poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) (PVDF-HFP), poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO), poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) and poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA)6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Despite the successful realization of n-type characteristics, the overall performance of these i-TE materials is relatively low, attributing to the fact that the large size of anions and their strong interaction with the polymeric network limit the mobility of anions8,13.

To overcome the above constraints, researchers attempted to introduce another ion donor to optimize the anion migration rate via their synergistic interactions. For example, in the PVDF-HFP/1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoro-methylsulfonyl)imide (EMIM TFSI) ionogel13, the Huang group employed the synergistic effect of hydrogen bonding and ion-dipole interactions between EMIM+ and the polymer to suppress cation migration and enhance the heat of transport for the anion, resulting in a thermopower of −4 mV K−1. Furthermore, by introducing lithium tetrafluoroborate (LiBF4) and utilizing the strong coordination between Li+ and TFSI−/BF4−, the heat of transport for the anion is substantially increased, thereby boosting the thermopower to −15 mV K−1. Similarly, our group recently also enabled an improvement in the n-type performance via introducing another ion donors7. Specifically, we firstly constructed an n-type PEO/LiTFSI-based TE ionogel utilizing the strong coordination between PEO and Li+ to enlarge the migration of TFSI−, and then we induced 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate (EMIM BF4), whose BF4− could coordinate with Li+, further releasing more TFSI− and facilitating the migration of TFSI−. As a result, the thermopower was enhanced from −5.9 mV K−1 in binary ionogels to −15.2 mV K−1 in ternary ionogels. In addition to the aforementioned strategies, introducing inorganic materials, including graphene oxide (GO)14, silicon dioxide (SiO2)15, ferric chloride (FeCl3)10, et al, or upregulating the environmental conditions (humidity16,17, pH18, et al) proved to be another efficient way to expand anions migration to improve the n-type performance19. Although all the mentioned strategies efficiently boost the n-type thermoelectrical performance, extra ion donors inevitably cause ion leakage risks, the inorganic fillers always result in a critical trade-off between TE performance and mechanical properties, and the upper humidity conditions substantially exceed typical operational environments, all of these issues severely constrain practical applications. Therefore, developing n-type TE ionogels that deliver high TE performance under low ionic loadings, while possessing favorable mechanical properties and adaptability to common low-humidity environments, represents a critical yet challenging research frontier.

Interestingly, liquid crystal elastomer (LCE) network composed of soft segments and mesogenic units may unlocks a highly feasible platform to address the above challenge, originating to the fact: (i) The designed functional group in soft segments of LCE network could interact differently with cations or anions to enable differential migration rate, ensuring n-type feature on the first level; (ii) the alignment of the mesogenic units could be designed to amplify this ions mobility difference for further enlarging the n-type performance on the second level; (iii) the linkage between the soft chain and mesogenic units could be engineered to substantially further amplify the ions mobility difference, significantly boosting the n-type performance on the third level. Thus, engineering the LCE network is expected to unlock an exceptionally high thermopower at low humidity with single-component ionic donors, low ionic loading, and good mechanical properties at the same time.

Herein, we comprehensively explore the feasibility of the LCE network in enabling high-performance i-TE materials. Strategically engineering liquid crystal (LC) units and soft chain linkages could efficiently regulate the thermal mobility difference between cations and anions, via inducing synergistic ionic diffusion channels and ionic coordination interaction, enabling a significant increase in the thermopower. As a result, engineering the LCE structure from single-end mesogen-linked soft segments (side-chain LCE) to double-end mesogen-linked soft segments (main-chain LCE), combined with just swollen with single LiBF4, impressively enhances the n-type thermopower by 6.5 times (−27.4 mV K−1) just at low humidity blow 30% RH. Interestingly, a high p-type thermopower of 28.8 mV K−1 can also be enabled in the case of just swollen with single EMIM TFSI, achieving the largest adjustable p-n span among current homologous materials. Owing to both the p- and n-type characteristics, a π-type fiber-shaped i-TE capacitor is successfully integrated, which can output a voltage of 48.6 mV K−1 per unit, achieving the highest output in a π-type i-TE device. The areal energy density of a per n-type fiber reaches 8.1 mJ m−2. More importantly, the LCE-based i-TE materials also exhibit excellent stability under loadings of cyclic stretching, long-term testing, or temperature-controlled cycling, highlighting the potential of this system serving as efficient and practical thermal-charge energy storage. Finally, molecular dynamics simulations are employed to calculate the diffusion lengths of cations and anions in the engineering LCE system, a higher diffusion length of both Li+ (81 Å) and BF4− (122 Å) is observed inside the main-chain LCE system, in contrast with that (52 Å for Li+ and 82 Å for BF4−) inside the side-chain LCE system, elucidating the origins of the n-type thermopower and the effective enhancement of thermopower induced by engineered LCE from an ionic migration distance perspective. Overall, this work proposes a universal network for enabling high thermopower i-TE materials to solve the long-standing challenge in the i-TE field, and presents a stable, convenient, and scalable high-performance i-TE material with significant practical and commercial value.

Results

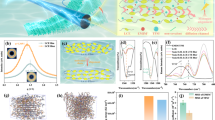

The thermopower in ionic thermoelectric materials originates from the differential migration rates of cations and anions within polymeric networks under temperature gradients. To address the challenge of scanty and low-performance n-type i-TE material, we aim to design a network intrinsically favoring anion migration. Here, LCE is selected as the substrate network, owing to its ionic selectivity interaction and ionic diffusion channel effects, a network intrinsically favoring exceptionally high thermopower, which may be unlocked. To realize this concept, we strategically designed two LCE fibers with distinct structures through careful selection of synthetic precursors and process optimization. A main-chain LCE (m-LCE) fiber is synthesized using 1,4-bis-[4-(6-acryloyloxyhexyloxy)benzoyloxy]-2-methylbenzene (RM82) as the liquid crystalline unit, where both terminals are incorporated into the molecular backbone (Fig. 1a). And 2,2′-(ethylenedioxy) diethanethiol (EDDET) is selected as the soft segment to potentially facilitate cation-selective interactions, owing to its ether bonds (C-O-C). As a control, we designed a side-chain LCE (s-LCE) fiber using 1,4-Bis-[4-(3-acryloyloxypropyloxy) benzoyloxy]-2-methylbenzene (RM257) as the liquid crystalline unit and EDDET as the soft segment, but the mesogens only connect one terminal to the molecular backbone, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. The m-LCE exhibits a more ordered and regular network structure, whereas the s-LCE demonstrates a more compact and disordered arrangement. These distinct network architectures are expected to yield dramatically different ionic diffusion behaviors, where the main-chain architecture is expected to potentially facilitate ionic diffusion originating from wider intermolecular spacing and more ordered ion transport channels. Hence, both the above cation-selective interactions from C-O-C of soft segments and the ordered ion transport channels from the mesogenic connection modes are conducive to boosting anion migration, indicating that rationally engineered LCE represents a promising polymeric network for high-performance n-type thermopower.

a Schematic illustration of main, side chain type molecular architectures (m-LCE network and s-LCE network) inside fibers. b 1H NMR spectra of m- and s-LCE architectures (solvent: CDCl3, magnet frequency: 600 MHz). c One-dimensional intensity profiles of m-/s-LCE architectures. Insets: 2D WAXD patterns of m- (left) and s- (right) LCE structures. d Binding energy between soft segments and ionic donors (Li+, BF4−, EMIM+, TFSI−) and Li+-BF4−, EMIM+-TFSI− pair for different LCE architectures.

Following the above design principle of n-type i-TE materials, we firstly synthesized m/s-LCE fiber and characterized by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) to verify the successful engineer of two LCE architectures. As for s-LCE: 1H NMR (CDCl3, δ, ppm), 6.25–5.68 (d, 4H, CH2 = CH-), 5.99 (m, 2H, CH2 = CH-), 1.36 (m, 4H, -CH2-); and m-LCE: 1H NMR (CDCl3, δ, ppm), 6.04–5.48 (d, 4H, CH2 = CH-), 5.79 (m, 2H, CH2 = CH-), 1.47 (s, 8H, -O-CH2(CH2)2CH2-O-), 1.32 (s, 8H, -O-CH2(CH2)2CH2-O-), as shown in Fig. 1b20,21,22. The emergence of additional methylene peaks in the m-LCE confirms the structural distinction between the two different alkyl chains of the mesogenic units. Furthermore, in the 1H NMR spectrum of the m-LCE, the peak area ratio between olefinic protons and methylene protons is 1:10, indicating that the olefinic groups at both terminals of the mesogenic units have participated in the reaction, with both ends incorporated into the main chain, thus validating its main-chain architecture23. In contrast, the 1H NMR spectrum of the s-LCE exhibits a peak area ratio of 1:1.59 between olefinic protons and methylene protons, demonstrating that only one terminal olefinic group is connected to the molecular main chain, which is characteristic of a side-chain structure. Concurrently, two-dimensional wide-angle x-ray diffraction (2D WAXD) measurements are conducted to investigate the influence of different chain architectures on LCE molecular spacing and order parameter. As illustrated in Fig. 1c, both LCE fiber exhibit anisotropic diffraction rings in their 2D WAXD patterns. Using the interplanar spacing equation

(where d represents molecular spacing and q denotes the scattering vector), we determine that the m-LCE fiber possesses a larger molecular spacing (4.67 Å), in contrast to its side-chain counterpart (4.45 Å)24,25. This enhanced spacing provides wider channels for ionic migration within the network structure. Moreover, these different molecular chains develop distinct chain alignments induced by the shear stress from the same fiber injection molding process (Supplementary Fig. 1)26, the order parameter calculated by Hermans-Stein orientation distribution function (Supplementary Information 1)24,27 for the m-LCE (0.44) is higher than that of s-LCE (0.31). This further confirms that the m-LCE network architecture offers more favorable migration pathways, thereby is expected to accelerate free ionic diffusion.

To select a rational ion donor, density functional theory (DFT) is then employed to study the interaction between ions and the above two LCE architectures. As shown in Fig. 1d, two widespread ion donors (LiBF4 and EMIM TFSI) are analyzed here, and soft segments of two chain types. As for LiBF4, Li+ cation displays stronger binding energies with the C-O-C of soft segment than BF4− in both m/s-LCE architectures, thereby facilitating BF4− anions diffusion behavior and showing promise for n-type thermoelectric characteristics. In addition, the m-LCE exhibits a larger difference in binding energy with Li+ and BF4− compared to the s-LCE due to the variations in molecular chain structure, which is favorable for further enhancing n-type thermopower. In turn EMIM TFSI, TFSI− anions favor forming hydrogen-like non-covalent bonding interaction with soft segment (C-O-C) in all LCE architectures28, and the m-LCE also exhibits a greater difference in binding energy between EMIM+ and TFSI− compared to s-LCE. The m-LCE structure thereby shows promise not only for achieving p-type thermoelectric properties but also for enlarging the p-type thermopower. Therefore, thermopower polarity can be regulated through the interactions between C-O-C of soft segment in LCE network and different ion donors, and m-LCE structure is more conducive to thermopower enhancement owing to its structural advantages of larger molecular spacing and higher order parameter.

Based on the above theoretical insights, the thermopower of two different chain-type LCE fibers after immersion in different ionic liquids/salts (not only the above LiBF4 and EMIM TFSI, but also BMIM PF6, EMIM OAC, EMIM Cl, and AMIM TFSI) is tested. The accuracy of the measurement system is ensured by performing quantitative benchmark calibration against previously reported ionic thermoelectric materials (Supplementary Figs. 2, 3)28,29. From Fig. 2a, it can be observed that the m-/s-LCE i-TE fiber exhibits identical thermoelectric polarity with the same ionic liquid, where LiBF4 and BMIM PF6 donors enable n-type characteristics, while the rest display p-type characteristics. And p/n type thermopower of m-LCE i-TE fiber has consistently proven higher than that of s-LCE structure. Notably, the thermopower polarity and performance advantages of m-LCE are consistent with the design principle in Fig. 1. Furthermore, for these n-/p-type LCE i-TE fiber, the ion donors-determined thermopower magnitude is further studied, with a focus on the influence of charge density and ionic size. In n-type materials, the higher charge density with smaller ionic size of Li+ enables strong coordination with LCE molecular chains and imposes minimal obstruction to anions migration, resulting in a substantially enlarged mobility contrast between cations and anions30,31. Conversely, in p-type materials, anions lack strong interactions with the molecular chains and preferentially form ion pairs with cations. The high charge density of Cl− and OAC− hinder ion pair dissociation, while the large ionic size of TFSI− hinders migration, amplifying the mobility difference and consequently improving the thermopower. (Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 1).

a Thermopower of m-/s- LCE fiber immersed in different types of ionic liquids. b Thermopower and conductivity of m-LCE i-TE fiber at various LiBF4 concentrations. c p-type and n-type thermoelectric performance of m-LCE i-TE fiber compared with literature reported under low humidity conditions below 70% RH5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,18,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. d The end-to-end distance and radius of gyration for m-/s- LCE fiber versus concentration of LiBF4. e Radial distribution functions and coordination numbers of m-LCE i-TE fiber. f Diffusion coefficients (MSD) of ions (Li+, BF4−) for m-/s- LCE fiber with different concentrations of LiBF4. g Schematic diagram of diffusion length (L). h Li+ and BF4− diffusion lengths in m-/s- LCE fiber versus LiBF4 concentration. All error bars denote mean ± standard deviation, number of replicates n = 3.

To further verify the advantages of m-LCE structures in enhancing thermoelectric performance, the influence of soft segment content and crosslinker concentration for m/s-LCE i-TE fibers, as well as LiBF4 concentration and immersion time, on the TE performance is further studied. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 5–7, Fig. 2b, the thermopower of the m-LCE i-TE fiber consistently surpasses that of the s-LCE i-TE fiber under various parameter adjustments. Ultimately, the thermopower of the m-LCE i-TE fiber reaches −27.4 mV K−1 (voltage-temperature curve and fitting plot as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8) under conditions (EDDET: 2.2 M, PETMP: 0.26 M, immersion time: 6 h, LiBF4 concentration: 0.75 M), which is an unexpected 3.5-fold improvement compared to the side chain structure (−7.9 mV K−1). Furthermore, the conductivity of both architectures exhibits monotonic increases with increased LiBF4 concentration and immersion time, and the m-LCE i-TE fiber demonstrates great conductivity (118.7 mS m−1) at 0.75 M LiBF4 for 6 h, which is 2.6 times higher than the side-chain structure (46.5 mS m−1) (Supplementary Fig. 9). Additionally, the thermal conductivity of m-/s-LCE i-TE fiber remains at a level of 0.1–0.13 W m−1 K−1 both before and after LiBF4 solution immersion due to the intrinsic low thermal conductivity of the LCE materials, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 10.

To further emphasize the universality of m-LCE fibers for high thermoelectric performance, the thermopower of different LCE chain structures impregnated with p-type ionic donor (EMIM TFSI) is investigated. Results show that the thermopower attains 28.8 mV K−1 by optimized the impregnation concentration and time (Supplementary Fig. 11), which is 2.5 times higher than that of the side-chain variant. In summary, the structural engineering of m-LCE provides an effective strategy for the development of high-performance p- and n-type properties at homologous thermoelectric materials. In comparison with performance at humidity below 70% RH (Fig. 2c), the thermopower of −27.4 mV K−1 obtained at humidity blow 30% RH in this work sets a record for binary system thermopower. Meanwhile, the m-LCE i-TE fiber reaches the largest p-n span (56.2 mV K−1) among known homologous materials by leveraging the advantages of its intrinsic network structure5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,18,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42.

In addition, the humidity stability, long-term stability, and voltage-temperature cycling reversibility performance are studied. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 12, the m-LCE i-TE fiber can maintain over 88% of its thermopower within a high humidity range (30–90% RH), owing to its hydrophobic and the effective barrier against humidity provided by its highly cross-linked network43. Moreover, the voltage remains stable without significant fluctuations or decay during a 10,000 s long-term test (Supplementary Fig. 13), which is primarily attributed to the structural advantages of the m-LCE network that enable enlarged mobility differences between anions and cations without requiring additional ionic donors, thereby effectively avoiding liquid leakage and encapsulation issues, as demonstrated in Supplementary Movie 1. Additionally, the m-LCE i-TE fiber shows stable voltage responses in the cycling stability test, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 14. Therefore, the m-LCE i-TE fiber not only possesses excellent thermopower but also demonstrates good humidity stability, long-term voltage stability, and voltage-temperature cycling reversibility performance.

To gain deeper insights into the influence of different chain-type architectures on thermoelectric performance, we firstly conduct theoretical analysis using molecular dynamics simulation (MD) to study molecular chain conformations of m-/s-LCE at various LiBF4 concentrations. As revealed in MD snapshots (Supplementary Fig. 15), polymer chains exhibit extended quasi-linear conformations at low LiBF4 concentration, as the limited ionic content results in dominant interchain electrostatic repulsion. With increasing LiBF4 concentration, enhanced Li+ binding to molecular chains progressively reduced interchain repulsion, leading to entropically favorable spherical conformations44. This conformational evolution is quantitatively confirmed by monitoring the end-to-end distance and radius of gyration with increasing LiBF4 concentration (Fig. 2d). Both architectures demonstrate progressive coiling transitions with increasing LiBF4 concentration, while the m-LCE molecular network remains more extended than s-LCE architectures44. This relatively expanded network structure of m-LCE provides favorable migration pathways for ionic thermal diffusion, validating the reasons for the better thermopower performance of m-LCE i-TE fibers. Moreover, we further quantify the solvation structures of both systems through MD simulations to analyze the coordination interactions between liquid crystalline networks and LiBF4. The radial distribution functions (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 16) reveal pronounced peaks at 2.1 Å for both architectures45,46,47, confirming the incorporation of ether group (C-O-C) oxygen atoms into the inner solvation shell of Li+. Peak intensities reach maxima at LiBF4 concentrations of 0.75 M and 0.85 M for m- and s-LCE structures, respectively. Notably, the Li+-Om-LCE peak amplitudes consistently exceeded those of Li+-Os-LCE across all concentrations, indicating stronger coordination capability of the m-LCE architecture with Li+. Coordination number (CNs) analysis further substantiates these findings, revealing an average of 2.35 oxygen ions surrounding each Li+ in the m-LCE system, significantly higher than the side-chain counterpart (0.94)48. These marked differences in radial distribution functions and CNs confirm the profound impact of molecular chain architecture on ionic interactions. And this impact can be attributed to the chain conformations, where the coiling conformation of s-LCE networks introduces steric hindrance to impede Os-LCE-Li+ coordination. From the diffusion coefficients (MSD) of Li+ and BF4− at various LiBF4 concentrations for both systems (Fig. 2f), it can be observed that Li+ and BF4− in m-/s-LCE architectures exhibited reduced diffusion coefficients due to limited mobile ion availability at low concentrations. Notably, the diffusion coefficients of Li+/BF4− and their difference reach their maxima at 0.75 M LiBF4, representing an optimal balance between chain conformation and ionic concentration. Conversely, both systems experience diminished ionic transport capabilities at high LiBF4 concentrations owing to the coil of polymer networks inhibiting Li+ coordination and disrupting efficient ionic transport pathways. In addition, Li+ consistently showed lower diffusion coefficients than BF4− due to the coordination-induced mobility constraints, resulting in n-type thermopower across both systems at various LiBF4 concentrations. And m-LCE i-TE system exhibits higher diffusion coefficients of cations/anions and their difference compared to s-LCE due to the more extended structural configuration, thereby achieving enhanced thermopower performance.

Previous research on ionic thermoelectric mechanisms primarily analyzes ionic diffusion behavior through diffusion coefficients and Eastman entropy, lacking a comprehensive investigation of ionic dynamic diffusion behavior from the perspective of distance and range. In this context, the residence time (τ) of concurrent motion between adjacent species can be used to characterize the differences in diffusion behavior between species49,50, and the calculation methodology is described in Supplementary Information 2. However, as demonstrated in the Supplementary Figs. 17–21, individual ionic residence times in both systems exhibit progressive increases with increasing viscosity, limiting their utility as standalone descriptors of diffusion behavior. To address this limitation, we converted residence times into diffusion lengths (L) using the relationship

where Dions represents the ionic diffusion coefficient, which is related to factors such as temperature, concentration, and ion size44. This transformation enables systematic and intuitive comparison of diffusion mechanisms across various concentrations, as schematically illustrated in Fig. 2g. Figure 2h illustrates the concentration-dependent diffusion lengths of Li+ and BF4− in both LCE architectures. In the m-LCE network, a progressive increase in diffusion length is observed in the low concentration range, attributed to the synergistic effects of LCE structural evolution and system viscosity modulation. The system exhibits maximum diffusion lengths at 0.75 M, reaching 122 Å for BF4− and 81 Å for Li+. Further increases in LiBF4 concentration induce substantial conformational changes in the polymer network, severely impeding ionic diffusion and migration, resulting in a dramatic reduction in diffusion lengths for both ionic species. In contrast, the s-LCE network demonstrates consistently shorter diffusion lengths for both BF4− and Li+, with a general declining trend as impregnation concentration increased. And s-LCE network exhibits maximum diffusion lengths at 0.85 M LiBF4 concentration, reaching 82 Å for BF4− and 52 Å for Li+. These values are notably lower than those observed in the main-chain system under identical conditions. This phenomenon primarily stems from the more complex and convoluted conformational structure of s-LCE, which inherently inhibits ionic migration and diffusion within the system. The diffusion length difference further validating the substantial advantages of m-LCE network architecture in facilitating ionic thermal diffusion.

To further verify the above thermoelectric mechanisms, fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was firstly employed to study interactions between anions/cations and different LEC polymeric networks (Supplementary Fig. 22). As shown in Fig. 3a, the m-LCE i-TE fiber exhibits a notable blue shift in the C-O-C asymmetric stretching vibration peak at 1091 cm−1, accompanied by peak splitting of the C-O-C bending vibration near 1250 cm−1 (Fig. 3b)51,52,53. Notably, the B-F peak at 1045 cm−1 remains unchanged, indicating coordination between the soft segment C-O-C moieties and Li+ in the m-LCE i-TE fiber, while BF4− anions show no chemical interaction with the molecular chains54,55,56. In contrast, the s-LCE i-TE fiber demonstrates minimal spectral changes. The C-O-C asymmetric stretching vibration peak remains stable and only minimal displacement of the bending vibration peak without peak splitting, indicating weaker coordination with Li+. Raman spectroscopic analysis further validates these findings. Figure 3c reveals that both LCE architectures displayed characteristic B-F peaks after impregnation54, the m-LCE i-TE fiber exhibits a more pronounced shift from the original B-F characteristic peak at 771 cm−1. Similarly, NMR characterization demonstrates that the original F signal at −158.574 ppm from m- and s- LCE i-TE fiber shifts to −154.058 ppm and −154.602 ppm, respectively (Fig. 3d)57. These comprehensive spectroscopic analyses confirm that BF4− dominated thermal migration occurs in both LCE structures owing to the migration hindrance of Li+ caused by strong coordination interactions, as illustrated in Fig. 3e. These selective interactions and binding strengths between anions/cations and m-/s-LCE molecular chains are consistent with the differences in ionic diffusion coefficient calculated from MD simulations, confirming the advantage of m-LCE in thermopower improvement compared to the s-LCE structure.

a Local graph o FTIR spectra of m-/s-LCE architectures highlighting the asymmetric stretching of C-O-C bonds. b Local graph o FTIR spectra of m-/s-LCE architectures highlighting the bending vibrations of C-O-C bonds. c Raman spectra for BF4− of m-/s-LCE architectures. d 19F NMR spectra of fluorine atoms in m-/s-LCE architectures (solvent: CDCl3, magnet frequency: 600 MHz). e Schematic of the coordination mechanism in m-LCE i-TE fiber.

Beyond its excellent thermoelectric performance, the m-LCE i-TE fiber also exhibits potential for scalable industrial production, along with excellent mechanical and optical properties. As demonstrated in Fig. 4a, a continuous 4-meter-long m-LCE i-TE fiber was successfully fabricated and photographed under ambient outdoor conditions. The fiber exhibits uniform semi-transparency and structural continuity, maintaining its mechanical integrity throughout the preparation and elongation processes without any observable fractures or defects. These characteristics strongly validate its potential for industrial-scale manufacturing. Benefiting from the favorable intrinsic mechanical properties of LCE materials, m-LCE i-TE fiber demonstrates excellent weaveability. Figure 4b shows a woven rectangular textile constructed from a single fiber. Through stretching, bending, and tensile-twist deformation, the textile exhibits no fracture phenomenon and recovers to its initial state (Supplementary Movies 2, 3), underscoring its tremendous potential for applications in wearable devices. Additionally, this m-LCE i-TE fiber also exhibits exceptional elastic resilience, as evidenced in Supplementary Fig. 23, Supplementary Movie 4. After subjection to 200% tensile strain, the fiber displays immediate and complete dimensional recovery to its initial length, with no observable fracture or stress relaxation phenomena.

a Field demonstration of a 4-meter m-LCE i-TE fiber under outdoor conditions. b Demonstration of fiber weavability and the load-bearing capability of fabric under tension, bending or torsion. c Stress-strain curves of m-LCE i-TE fiber at different impregnation times (inset figure shows a physical drawing with a 1-kg weight lifted). d Dynamic mechanical curves of m- and s-LCE architecture before and after LiBF4 impregnation. e Variation in thermopower of m-LCE i-TE fiber under various mechanical conditions: single-cycle elongation (0–120%) and cyclic deformation (0–1000 cycles). f SEM micrographs of m-LCE fiber after LiBF4 solution impregnation for 0 h, 6 h, and 12 h. g Radar plots of m-LCE i-TE fiber in four areas: n-type thermopower, mechanical properties, fiber processability and span of available thermopower.

Furthermore, the mechanical properties of both m- and s-LCE i-TE fiber are analyzed comparatively. It can be seen from Supplementary Fig. 24 that there is a trade-off relationship between the mechanical contributions of the crosslinker and the soft segment, with the former primarily governing the stress level and the latter dominating the strain behavior of the material. As a result, through an optimal balance of soft segment and crosslinker concentrations, the optimized m-LCE fiber achieves an ultimate tensile strength of 972.1 kPa and elongation at break of 518.3%, representing remarkable improvements of 143% and 46.3%, respectively, compared to its side-chain counterpart. Despite a certain degree of compromise in mechanical properties after LiBF4 impregnation (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 25) due to swelling-induced disruption of network crosslinking structure, the m-LCE i-TE fiber maintains substantially favorable mechanical performance compared to the side-chain variant, and the m-LCE i-TE fiber delightfully exhibits practical load-bearing capability by successfully supporting a 1-kg weight (Supplementary Movie 5). This enhanced mechanical robustness can be attributed to the more ordered molecular chain alignment inherent to the main-chain architecture. The quasi-solid-state gel properties and stable internal network structure of LCE i-TE fiber are further investigated through dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA), as shown in Fig. 4d58,59. Over a frequency range of 10−1 to 102 rad/s, both LCE architectures exhibit storage moduli (G′) consistently higher than loss moduli (G″) before and after LiBF4 solution impregnation, demonstrating stable quasi-solid-state gel characteristics and a robust crosslinked network structure7.

Meanwhile, as shown in Fig. 4e, Supplementary Figs. 26, 27, the m- LCE i-TE fiber maintains over 80% of its thermopower after stretching from a strain of 0% to 120%, as well as 1000-cycles stretching, leveraging its gel and mechanical properties. These results demonstrate the stability of the molecular chain structure and excellent practical viability of the fabricated m-LCE i-TE fiber.

As for the optical properties of the m-/s-LCE i-TE fiber, the surface morphology is analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As shown in Fig. 4f, the m-LCE fiber exhibits ordered stripe and scale-like structures before impregnation. However, the surface stripes disappeared due to swelling after immersion in the LiBF4 solution. With prolonged impregnation time, LiBF4 crystals precipitated and aggregated on the surface. These observations are further confirmed by EDS mapping (Supplementary Fig. 28), and a similar phenomenon is also observed in s-LCE i-TE fibers (Supplementary Figs. 29, 30). In addition, the monodomain structure and birefringence of the m-/s-LCE i-TE fibers are characterized using polarized optical microscopy (POM). As shown in Supplementary Figs. 31, 32, distinct color patterns are observed in the m-/s-LCE i-TE fibers both before and after solution impregnation when fiber axis is aligned at 45° to the polarizer, while appearing dark at 0°. These observations confirm the monodomain alignment and anisotropic characteristics of m-/s-LCE fibers60,61, in which the uniformly aligned liquid crystal mesogens are favorable for ion migration and further for amplifying the thermal migration difference between cations and anions62,63, this highlights the effectiveness of the LCE polymeric network developed herein for gaining high-performance i-TE materials. In addition, densely packed, uniformly oriented striations and grooves in the m-LCE i-TE fiber (Supplementary Fig. 33) are observed by atomic force microscopy (AFM), revealing the high degree of ordering in m-LCE i-TE fiber63.

In summary, compared to previously reported ionic thermoelectric materials, m-LCE i-TE fiber demonstrates competitive comprehensive performance under low humidity conditions (below 70% RH), particularly in terms of n-type thermopower, p-n performance range, mechanical properties and fiberization capability (Fig. 4g)8,12,29,64,65,66,67,68. This m-LCE material represents both promising candidates for thermoelectric applications and provides effective design strategies for next-generation ionic thermoelectric materials.

Given the capacitive characteristics of ionic thermoelectric materials, the capacitive behavior of high-thermopower n-type LCE i-TE fibers is investigated. Figure 5a, b illustrates the four-stage working mechanism of the capacitor operation. Under a temperature gradient of 3.8 K, the initial stage generates an open-circuit voltage of approximately 75 mV, attributed to the diffusion and accumulation of cations and anions at the cold/hot terminals (stage Ⅰ). In stage Ⅱ, the connection of an external load facilitates electron flow through the circuit, neutralizing the thermoelectric potential to zero due to unsaturated electrode charges. The stage Ⅲ, characterized by the removal of both temperature gradient and external load, triggers the gradual redistribution of accumulated ions to their initial random state. Consequently, electrons retained at the cold electrode generate a reverse voltage, which subsequently diminishes to zero upon reconnection of the external load (stage Ⅳ)69,70. The voltage decay characteristics during the second and fourth stages exhibit progressive retardation with increasing load resistance, as demonstrated in Fig. 5c. Then, through the calculation of stage Ⅱ by equation

(where A is the cross section area of fiber, Vout is voltage in stage II, Rload is load resistance), the energy density (E) is calculated to be 8.1 mJ m−2 at a load resistance of 1 MΩ, as shown in Fig. 5d71.

a Schematic illustration of the working mode of i-TE capacitors. b Voltage-temperature gradient i-TE capacitors integrated by n-type m-LCE i-TE fiber. c Thermovoltage under varying loads during the Stage Ⅱ (inset: Thermovoltage under varying loads during the Stage Ⅳ). d Energy density of i-TE capacitors with different load resistors. e Voltage-temperature curves for i-TE device integrated with five n-type m-LCE i-TE fibers. f The output voltage per degree of temperature difference (ΔV/ΔT) of π-type device integrated by different numbers of p-n pairs. g, h Working principles of planar/three-dimensional structures thermal-charge wearable device. i Voltage-temperature difference curve of the planar device attaching to a beaker with hot water. j Physical picture and infrared thermal images of body heat harvesting test by three-dimensional device. k Voltage-temperature difference curve of the three-dimensional device worn on the human arm.

The exceptionally high output voltage of ionic thermoelectric materials presents significant potential for thermal-charge devices and high-sensitivity sensing applications. As output voltage serves as a critical performance metric for power generation and sensing capabilities, we firstly utilize a liquid crystal display (LCD) to verify the power supply capability of m-LCE i-TE fibers. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 34, this fiber can illuminate the LCD screen to display numbers under a temperature difference of 45 K. Indeed, the startup temperature difference can be effectively reduced through connected the high-performance n-type and p-type m-LCE i-TE fiber in parallel thermally and in series electrically. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 35, five n-type m-LCE i-TE fibers are connected in series using silver wire interconnects, demonstrating excellent and rapid voltage responsiveness (Fig. 5e), and the output voltage per degree of temperature difference (ΔV/ΔT) of the device reaches −130.2 mV K−1 through fitting the temperature-voltage data (Supplementary Fig. 36). In addition, a π-type device integrated with p-type and n-type m-LCE i-TE fibers is further integrated, whose output performance increases with the number of p-n pairs, ultimately achieving −146.8 mV K−1 for three p-n pairs (Fig. 5f). Notably, the utilization of m-LCE architecture for both p- and n-type materials results in excellent compatibility between the polymer counterparts, manifesting in stable output voltage characteristics (Supplementary Fig. 37). The demonstrated capacitive behavior and ionic device performance validate the potential of m-LCE i-TE fiber for low-grade heat harvesting and sensing applications.

Planar or three-dimensional wearable i-TE devices are further fabricated by reasonably embedding m-LCE i-TE fiber into a LCE fiber-woven fabric, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 38, 39. It can be observed from the working principles of the two structurally distinct thermal-charge devices that the planar device (Fig. 5g) primarily relies on a temperature difference generated between one end in contact with a heat source and the opposite end to produce voltage output. In contrast, the three-dimensional thermal-charge device (Fig. 5h) creates a temperature gradient when the bottom surface contacts a heat source while the opposite side is exposed to air or another object at a different temperature. For the planar device, temperature differences of 13.5 K and 14.6 K are generated between the hot and cold ends of the fiber after attaching to the surface of a beaker with hot water and ice water, respectively, then gradually decreasing and stabilizing at 10.3 K and 7.5 K over time. At the same time, the voltage exhibits rapid response within 450 s, reaching values of 270 mV and 206.6 mV under the stable temperature difference, respectively (Fig. 5i, Supplementary Fig. 40). Meanwhile, three-dimensional device generates a voltage of ~ 44.5 mV at the temperature difference of 1.7 K (Fig. 5j, k) by attaching it onto the human arm, with one end in contact with the body and the other exposed to the ambient air. Furthermore, LCE material exhibits a maximum contraction of 18.6% at 70 °C (Supplementary Fig. 41), and DSC curves of its indicate that the liquid crystalline range of m-LCE i-TE fiber is from 42.1 °C to 90.6 °C (Supplementary Fig. 42), demonstrating great thermally-actuated potential. These experiments not only validate the feasibility of m-LCE i-TE fiber for practical applications, but also demonstrate their application potential in the domains of wearable devices and low-grade thermal energy harvesting.

Discussion

In summary, we engineering the LCE network from side-chain structure to main-chain structure and controlling the interaction between ions and LCE polymeric network, unlocking high-performance i-TE materials. The m-LCE i-TE fiber achieves a remarkable n-type thermopower of −27.4 mV K−1 under low humidity conditions below 30% RH, owing to the synergistic effects of ion diffusion channels by mesogens alignment and the coordination between ether bonds (C-O-C) of soft segments and Li+, representing the highest performance among binary system n-type ionic thermoelectric materials to date. Simultaneously, m-LCE i-TE fiber achieves the highest p-n performance range among reported homologous materials (56.2 mV K−1) by changing ion donors. Thanks to the high p- and n-type performance, the i-TE device integrated by three p-n pair yields a ΔV/ΔT of 146.8 mV K−1. The areal energy density of per m-LCE fiber reach 8.1 mJ m−2. The strategy of engineering LCE structures exhibits universal applicability for enhancing thermoelectric properties, providing promising insights for the development of i-TE materials.

Methods

Materials

1,4-bis-[4-(6-acryloyloxyhexyloxy) benzoyloxy]-2-methylbenzene (RM82, 95%) and 1,4-Bis-[4-(3-acryloyloxypropyloxy) benzoyloxy]-2-methylbenzene (RM257, 97%) were purchased from Shanghai Bide Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd., 2,2′-(ethylenedioxy) diethanethiol (EDDET, 98%), pentaerythritol tetrakis (3-mercaptopropionate) (PETMP, 95%) and ethyl acetate were supplied by Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd., tri(propylene glycol) diacrylate (TPGDA, 90%), Triethylamine (TEA, 99.5%), butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT, 99%), Dimethylformamide (DMF, 99.5%) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. LiBF4, EMIM OAC/TFSI/Cl, BMIM PF6 and AMIM TFSI were purchased from Lanzhou Greenchem ILS, LIPC, ACS (Lanzhou, China). All reagents were used as received without any further purification.

Preparation of main/side chain LCE ionic thermoelectric fiber

The fabrication of main-/side-chain LCE i-TE fibers initially requires the preparation of main-/side-chain LCE fibers. Specifically, for main-chain LCE fibers, RM82 (2.64 g), EDDET (0.8 g), PETMP (0.25 g), TPGDA (0.4 g) and BHT (0.02 g) were dissolved in DMF (2 mL) and stirred at 70 °C for 20 min until a transparent solution was obtained. Subsequently, TEA (0.1 mL) was added to the mixture and stirred for 5 min. Then, the LCE solution was transferred into a syringe and injected into a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tube. The filled tube was then horizontally placed in a vacuum oven at 70 °C for 12 h. Finally, the LCE fiber was carefully peeled off the PTFE tube. For side-chain LCE fibers, RM257 (2.4 g), EDDET (0.7 g), and PETMP (0.1 g) were dissolved in ethyl acetate (2.4 mL) and stirred at 70 °C for 1 h. Then, DPA (9 μL) was added and stirred for 1 min to form the LCE precursor solution. Then, the LCE solution was injected into a PTFE tube via a syringe and horizontally stored at room temperature for 12 h. Finally, the side-chain LCE fiber was peeled from the PTFE tube. Then, as-synthesized m-/s-chain LCE fibers were immersed in LiBF4 (0.55–0.95 mol/L)/EMIM TFSI (0.25–1.25 mol/L) solutions for controlled periods varying from 1 to 12 h, yielding n-type and p-type main-/side-chain LCE ionic thermoelectric fibers.

Preparation of main chain LCE ionic thermoelectric devices

The assembly of main-chain LCE ionic thermoelectric devices was implemented by precisely positioning p/n-type LCE fibers on a Peltier module in thermal series and parallel configurations, with one end of each fiber placed on the hot side and the other end on the cold side. Adjacent fibers were interconnected and reinforced with silver wires and silver paste to ensure reliable electrical connections.

Preparation of planar/three-dimensional thermal-charge wearable device

The thermal-charge device consists of a substrate module and a thermoelectric module. The substrate module is fabricated by knitting a 2-meter-long m-LCE fiber into a rib-structured textile measuring 3 cm in length and 6 cm in width. The thermoelectric module comprises a separate m-LCE i-TE fiber, which is integrated into the m-LCE textile through embedding and interweaving. The planar thermal-charge device is achieved as the m-LCE i-TE fiber is fully embedded on one side of the textile, whereas a three-dimensional thermal-charge device is formed when half of the fiber is embedded on one side, and the other half is embedded on the opposite side. Silver wires serving as electrodes are similarly embedded and connected to the cold and hot ends of the fiber in a planar/three-dimensional thermal-charge wearable device.

Characterization

The micro morphology and optical properties of LCE i-TE fibers were conducted using FE-SEM (SU8010, Hitachi), AFM (FastScan Bio, Bruker) and POM (DM750P, Leica). The FTIR spectroscopy (Nicolet6700, Thermo Fisher) with the attenuated total reflection accessory and Raman spectra (inVia-Reflex, Renishaw) with a 633 nm laser were recorded to analyze the ion and molecular interchain interaction. Thermopower Si was measured by a homemade equipment based on the equation

here potential differences ΔV arising from temperature differences ΔT was recorded by Keithley 2182 A. The linear correlation (R2) between ΔV and ΔT should be > 0.99. Test items were tested at 3 times of each sample for an average value. All samples were prepared with a standardized dimension of 2 mm in diameter and 2 cm in length. And samples were placed on a Peltier module with silver wires serving as electrodes, the diameter and length of silver wire used for testing were 0.25 mm and 4 cm, respectively, and the spacing between silver wires was 1.5 cm. The temperature at the cold and hot ends of the Peltier module was regulated by varying the input voltage, where an increase of 0.01 V in voltage achieves a precise control of 0.1 K temperature difference. The temperature change was recorded and exported using an infrared thermographic camera. The ambient humidity during testing was monitored in real time using a hygrometer. The ionic conductivity σi was calculated as follows:

where the d, A, and R in the formula represent the thickness, area, and ionic resistance, respectively. The ionic resistance was tested by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy on an electrochemical workstation (DH7006), with the frequency ranging from 0.1 to 100000 Hz. Stress-strain curves were performed on an Instron (5969) testing instrument with a speed of 50 mm min−1 at room temperature. And the gelatin properties of LCE i-TE fibers, which the angular frequency dependencies of the storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) were performed by DMA (Q800, TA).

Computational details

Modeling and Simulation Methods: All ionic species and small molecules were parameterized using the next-generation general AMBER force field (GAFF2), with specific force field parameters generated using the sobtop software. The initial configurations were constructed using the Packing Optimization for Molecular Dynamics Simulations (Packmol) program with a periodic simulation box of 40 × 40 × 40 nm3. All molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were performed using the GROMACS 2019.5 package. The simulation protocol consisted of three main stages:

-

1.

Energy Minimization

The system was initially minimized using a combination of 5000 steps of steepest descent, followed by 5000 steps of conjugate gradient algorithms to eliminate unfavorable contacts.

-

2.

NPT Pre-equilibration

The system was pre-equilibrated in the NPT ensemble using the V-rescale thermostat at 298 K and the Parrinello-Rahman barostat at 1 atm. Non-bonded interactions were treated with a cutoff radius of 1.2 nm, and the integration time step was set to 1 fs.

-

3.

Production MD Simulation

Following equilibration, the temperature coupling was switched to the Berendsen thermostat. Bond lengths and angles were constrained using the LINCS algorithm. A twin-range cutoff of 1.2 nm was employed for van der Waals interactions, while long-range electrostatic interactions were handled using the particle-mesh Ewald (PME) method. Trajectory frames were saved every 10.0 ps for subsequent analysis.

The initial geometries for density functional calculation (DFT) were obtained from ChemDraw and chem3D. Moreover, the MD simulations were performed via xTB software to obtain the possible binding poses of the polymer and ionic liquids. The most stable pose was then further optimized via Gaussian 16 software with a level of b3lyp/6–31 g(g,p) em = gd3bj. The results were then analyzed via Multiwfn 3.7 software, visualized via VMD software version 1.9.3. Furthermore, the charge density is evaluated by the ratio of the difference between the maximum and minimum ionic charges to the ionic size. Written and informed consent was received from all authors.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files, and all data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Cao, L. et al. Approaches and methods for improving the performance of ionic thermoelectric materials. Chem. Eng. J. 506, 160206 (2025).

Wang, M. et al. Tough and stretchable ionogels by in situ phase separation. Nat. Mater. 21, 359–365 (2022).

Bin, C. et al. Giant negative thermopower of ionic hydrogel by synergistic coordination and hydration interactions. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi7233 (2021).

Zhao, W. et al. Tailoring Intermolecular Interactions Towards High-Performance Thermoelectric Ionogels at Low Humidity. Adv. Sci. 9, e2201075 (2022).

Chi, C. et al. Reversible bipolar thermopower of ionic thermoelectric polymer composite for cyclic energy generation. Nat. Commun. 14, 306 (2023).

Chi, C. et al. Selectively tuning ionic thermopower in all-solid-state flexible polymer composites for thermal sensing. Nat. Commun. 13, 221 (2022).

Wei, Z. et al. Exceptional n-type thermoelectric ionogels enabled by metal coordination and ion-selective association. Sci. Adv. 9, eadk2098 (2023).

Liu, S. et al. High p- and n-type thermopowers in stretchable self-healing ionogels. Nano Energy 100, 104572 (2022).

Wu, Z. et al. Advanced bacterial cellulose ionic conductors with gigantic thermopower for low-grade heat harvesting. Nano Lett. 22, 8152–8160 (2022).

Bharti, M. et al. Anionic conduction mediated giant n-type Seebeck coefficient in doped Poly(3-hexylthiophene) free-standing films. Mater. Today Phys. 16, 100307 (2021).

Kim, B., Hwang, J. U. & Kim, E. Chloride transport in conductive polymer films for an n-type thermoelectric platform. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 859–867 (2020).

Cho, C. et al. Bisulfate transport in hydrogels for self-healable and transparent thermoelectric harvesting films. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 2049–2060 (2022).

Liu, S. et al. Giant and bidirectionally tunable thermopower in nonaqueous ionogels enabled by selective ion doping. Sci. Adv. 8, eabj3019 (2022).

Jeong, M. et al. Embedding aligned graphene oxides in polyelectrolytes to facilitate thermo-diffusion of protons for high ionic thermoelectric figure-of-merit. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2011016 (2021).

Malik, Y. T. et al. Self-healable organic-inorganic hybrid thermoelectric materials with excellent ionic thermoelectric properties. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2103070 (2021).

Akbar, Z. A., Jeon, J. W. & Jang, S. Y. Intrinsically self-healable, stretchable thermoelectric materials with a large ionic Seebeck effect. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 2915–2923 (2020).

Fang, Y. et al. Stretchable and transparent ionogels with high thermoelectric properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2004699 (2020).

Lee, L. C. et al. A pH-sensitive stretchable zwitterionic hydrogel with bipolar thermoelectricity. Small 20, 2311811 (2024).

Yu, W. et al. Exceptional n-type ionic thermoelectric hydrogels by synergistic hydrophobic and coordination interactions. Adv. Mater. 37, e10199 (2025).

Meng, F. B. et al. Synthesis and characterization of side-chain liquid crystalline polymers and oriented elastomers containing terminal perfluorocarbon chains. Polymer 52, 5075–5084 (2011).

Liu, Z. P. et al. Synthesis and characterization of two series of pressure-sensitive cholesteric liquid crystal elastomers with optical properties. Liq. Cryst. 47, 143–153 (2019).

Meng, F. B. et al. Cholesteric liquid-crystalline elastomers prepared from ionic bis-olefinic crosslinking units. Polym. J. 37, 277–283 (2005).

Zheng, Y., Shen, M., Lu, M. & Ren, S. Liquid crystalline epoxides with long lateral substituents: Synthesis and curing. Eur. Polym. J. 42, 1735–1742 (2006).

Wang, Y. et al. Liquid crystal elastomer twist fibers toward rotating microengines. Adv. Mater. 34, e2107840 (2022).

Yao, Y. et al. Enabling liquid crystal elastomers with tunable actuation temperature. Nat. Commun. 14, 3518 (2023).

Fan, Y. et al. One-step manufacturing of supramolecular liquid-crystal elastomers by stress-induced alignment and hydrogen bond exchange. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202308793 (2023).

Dong, X. et al. Monodomain liquid crystal elastomer bionic muscle fibers with excellent mechanical and actuation properties. iScience 26, 106357 (2023).

Cao, L. et al. An actuatable ionogel thermoelectric fiber with aligned mesogens-induced thermopower for four-dimensional dynamically adaptive heat harvesting. Nat. Commun. 16, 5445 (2025).

Dai, Y. et al. Electrode-dependent thermoelectric effect in ionic hydrogel fiber for self-powered sensing and low-grade heat harvesting. Chem. Eng. J. 497, 154970 (2024).

Xia, Y. et al. An efficient alkali metal doping strategy via Se&MF co-selenization method to achieve high-efficiency CZTSSe thin-film solar cells. Chem. Eng. J. 519, 165170 (2025).

Qin, H. et al. Flexible nanocellulose-enhanced Li+ conducting membrane for solid polymer electrolyte. Energy Storage Mater. 28, 293–299 (2020).

Shu, Y. et al. Cation effect of inorganic salts on ionic Seebeck coefficient. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 103902 (2021).

Chen, B. et al. Specific behavior of transition metal chloride complexes for achieving giant ionic thermoelectric properties. npj Flex. Electron. 6, 79 (2022).

Zhao, D. et al. Polymer gels with tunable ionic Seebeck coefficient for ultra-sensitive printed thermopiles. Nat. Commun. 10, 1093 (2019).

Laux, E. et al. Thermoelectric generators based on ionic liquids. J. Electron. Mater. 47, 3193–3197 (2018).

Gogoi, R. et al. Application of lamellar nickel hydroxide membrane as a tunable platform for ionic thermoelectric studies. Mater. Horiz. 10, 3072–3081 (2023).

Duan, J. et al. P-N conversion in thermogalvanic cells induced by thermo-sensitive nanogels for body heat harvesting. Nano Energy 57, 473–479 (2019).

Shen, H. et al. All-printed flexible hygro-thermoelectric paper generator. Adv. Sci. 10, e2206483 (2023).

Le, Q. et al. Giant thermoelectric performance of N-type ionogels by synergistic dopings of cations and anions. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2302472 (2023).

Jiang, Q. et al. High thermoelectric performance in n-type perylene bisimide induced by the soret effect. Adv. Mater. 32, e2002752 (2020).

Mardi S. et al. Interfacial effect boosts the performance of all-polymer ionic thermoelectric supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 9, 2201058 (2022).

Wu, X. et al. Self-powered and green ionic-type thermoelectric paper chips for early fire alarming. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 12, 27691–27699 (2020).

Wu, Z. L. et al. Microstructured nematic liquid crystalline elastomer surfaces with switchable wetting properties. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 3070–3076 (2013).

Fong, K. D. et al. Ion Transport and the true transference number in nonaqueous polyelectrolyte solutions for lithium ion batteries. ACS Cent. Sci. 5, 1250–1260 (2019).

Kwon, H. et al. Borate-pyran lean electrolyte-based Li-metal batteries with minimal Li corrosion. Nat. Energy 9, 57–69 (2023).

Yin, Y. et al. Ultralow-temperature Li/CFx batteries enabled by fast-transport and anion-pairing liquefied gas electrolytes. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207932 (2022).

Sheng, L. et al. Impact of lithium-ion coordination on lithium electrodeposition. Energy Environ. Mater. 6, e12266 (2022).

Miao, X. et al. Achieving high-performance lithium-sulfur batteries by modulating Li+ desolvation barrier with liquid crystal polymers. Adv. Mater. 36, 2401473 (2024).

Borodin, O., Smith, G. & Henderson, W. Li+ cation environment, transport, and mechanical properties of the LiTFSI doped N-Methyl-N-alkylpyrrolidinium+TFSI− ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 110, 16879–16886 (2006).

Solano, C. J. F. et al. A joint theoretical/experimental study of the structure, dynamics, and Li+ transport in bis([tri]fluoro[methane]sulfonyl)imide TFSI− based ionic liquids. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 034502 (2013).

Li, J. et al. Competitive Li+ Coordination in Ionogel Electrolytes for Enhanced Li-Ion Transport Kinetics. Adv. Sci. 10, 2300226 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Rapid lithium ion transfer of crosslinked electrolyte through the coordination of C–O–C/C = O segments for LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2 lithium metal batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 483, 149380 (2024).

Ferry, A., Jacobaaon, P. & Stevens, J. Studies of ionic interactions in poly(propylene glycol)4000 complexed with triflate salts. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 12574–12582 (1996).

Mao, M. et al. Anion-enrichment interface enables high-voltage anode-free lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 1082 (2023).

Qin, N. et al. Trace LiBF4 enabling robust LiF-rich interphase for durable low-temperature lithium-ion pouch cells. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 4843–4851 (2024).

Seo, D. M. et al. Solvate structures and computational/spectroscopic characterization of LiBF4 electrolytes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 18377–18386 (2014).

Li, G. X. et al. Enhancing lithium-metal battery longevity through minimized coordinating diluent. Nat. Energy 9, 817–827 (2024).

Esmaeeli, R. & Farhad, S. Parameters estimation of generalized Maxwell model for SBR and carbon-filled SBR using a direct high-frequency DMA measurement system. Mech. Mater. 146, 103369 (2020).

Setua, D. K. et al. Determination of dynamic mechanical properties of engineering thermoplastics at a wide frequency range using the Havriliak-Negami model. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 100, 677–683 (2006).

Guillen, C. J. et al. Controlled Diels-Alder “click” strategy to access mechanically aligned main-chain liquid crystal networks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202214339 (2022).

Wu, D. et al. Novel biomimetic “Spider Web” robust, super-contractile liquid crystal elastomer active yarn soft actuator. Adv. Sci. 11, 2400557 (2024).

Vasanji, S. et al. Stiffening liquid crystal elastomers with liquid crystal inclusions. Adv. Mater. 37, e2504592 (2025).

Yao, M. et al. A highly robust ionotronic fiber with unprecedented mechanomodulation of ionic conduction. Adv. Mater. 33, e2103755 (2021).

Liu, C. et al. Ion regulation in double-network hydrogel module with ultrahigh thermopower for low-grade heat harvesting. Nano Energy 92, 106738 (2022).

Park, S. et al. Mesogenic polymer composites for temperature-programmable thermoelectric ionogels. J. Mater. Chem. A 10, 13958–13968 (2022).

Ding, T. et al. All-soft and stretchable thermogalvanic gel fabric for antideformity body heat harvesting wearable. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2102219 (2021).

Ho, D. H. et al. Zwitterionic polymer gel-based fully self-healable ionic thermoelectric generators with pressure-activated electrodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301133 (2023).

Tian, C. et al. Thermogalvanic hydrogel electrolyte for harvesting biothermal energy enabled by a novel redox couple of SO4/32− ions. Nano Energy 106, 108077 (2023).

Zhao, D. et al. Ionic thermoelectric supercapacitors. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 1450–1457 (2016).

Yang, X. et al. High-performance ionic thermoelectric supercapacitor for integrated energy conversion-storage. Energy Environ. Mater. 5, 954–961 (2021).

Kim, D. H. et al. Self-healable polymer complex with a giant ionic thermoelectric effect. Nat. Commun. 14, 3246 (2023).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U23A20685, U24A2061, 52403349), the Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (202101070003E00110), Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology (23520710300, 24YF2700400), AI-Enhanced Research Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (SMEC-AI-DHUY-04), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2232024D-32). We acknowledge the technicians at Shenzhen HUASUAN Technology Co., Ltd. for assistance with theoretical calculations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W., W.J., and T.S. conceived the ideas and designed the work. L.C. carried out the experiments, including material preparation and characterization, device fabrication, and measurements. L.C. and T.S. contributed to microstructural characterization. T.S. carried out the density functional theory and molecular dynamics calculations. L.C. assisted with the power-generation measurements. T.S. contributed to the drawings. L.C. and T.S. wrote the draft. H.Z. and L.C. contributed to the discussion and editing. All authors approve the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Andraz Resetic, Hesheng Xia, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, L., Sun, T., Zhao, H. et al. Engineering liquid crystal elastomer unlocks high thermopower for fiber-shaped ionic thermoelectric capacitors. Nat Commun 17, 1251 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68011-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-68011-w